Highlights

-

•

Chemically induced mutagenesis has great importance in plant breeding programs whereby random or selectively changes in genetic material may result in a desirable one.

-

•

Ethyl-Methane Sulphonate (EMS), Methy-Methane sulphonate, Cadmium nitrate [Cd(NO3)2] and Lead nitrate [Pb(NO3)2] are the chemicals used to induce mutations at loci that regulate economically important traits.

-

•

The study is carried out to evaluate the effects of EMS, MMS, Cd(NO3)2 and Pb(NO3)2 on changes in morphological and quantitative traits, and to understand genetic diversity through SSR markers analysis in chilli cultivar.

-

•

In this experimental study, we are confident that chilli plant test system is suitable for testing of EMS, MMS, Cd(NO3)2 and Pb(NO3)2 to induce genetic diversity.

-

•

Investigations are evident that the selection of mutants may be more effective by coupling the genetic heritability with genetic advance.

-

•

Gene action is recommended for further study to select the yield contributing traits; hence, chemical mutagens have a very important role in the improvement of quantitative traits in crop breeding programs.

-

•

Stability in genetic heritability should be analyzed and improved mutants should be hybridizing to produce the elite genotypes in the next generations of chilli cultivars.

Keywords: Capsicum annuum L., Capsaicin, Micronutrients, Protein, SSR markers, Mutagens

Abstract

Identification and characterization of crop mutants through molecular marker analysis are imperious to develop desirable traits in mutation breeding programs. In the present study, macromolecular variations with altered morphological, quantitative, and biochemical traits were generated through chemically induced mutagenesis via alkylating agents and heavy metals. Statistical analysis based on quantitative traits indicating enhanced mean value in mutant lines selected from the M4 generation as compared to previous generations. Identification and characterization of morphology in selected mutant lines are based on altered phenotypes (e.g. tall and dwarf mutant with high yield, fruits with thick texture and bold seeds, etc.) in comparison to control populations. The useful mutations were recorded in phytochemicals (e.g. capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin) and macro and micro nutrients profile (e.g. protein, iron, copper, cadmium and zinc) in selected mutant lines of Capsicum annuum L. Single Sequence Repeats (SSRs) markers analysis in selected mutant lines revealed genetic diversity in Capsicum. annuum L. The total of 44 alleles were observed with average number of allele 4.00. The Unweighted Pair Group Arithmetic Mean Method (UPGMA) showed maximum dissimilarity was recorded between mutant A-III and F-III followed by mutant G-III and C-III, while mutant B-III and G-III showed the lowest dissimilarity to each other followed by mutant L-III and mutant J-III. Correlation and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) revealed genetic diversity among mutant lines indicating their prioritization over other traits in indirect selection and also revealed that mutants treated with lower and medium concentrations were divergent. These mutant lines could be suitable in crop improvement programs for the broadening the genetic base of C. annuum L. Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) grouped the mutants into two clusters with variable euclidean distance indicated heterogeneous mutant lines developed from induced mutagenic treatments. Thus beneficial mutations could be induced in chilli genotypes via mutation breeding to enhance genetic variability in limited resources, period, and efforts.

1. Introduction

Chilli (Capsicum annuum L.) has played a significant role in food security of the world as a major vegetable and spice crop.1 Capsicum is a genus belonging to Solanaceae family. Most members of the genus are grown throughout the world as a vegetable and spice in tropical and sub-tropical regions.2 Genus Capsicum contains over 100 species and even more, botanical varieties,3 comprising five domesticated species (such as C. annuum, C. baccatum, C. frutescence, C. pubescence, and C. chinense), all believed to have originated from New world.4 Chilli fruit and vegetables not only have nutritional value, but also are highly effective in fighting against neuro degenerative dieseases. Chilli is an excellent source of natural antioxidants that contain a wide variety of bioactive substances which are important for preventing free radical formation through scavenging or promoting their decomposition.5 Chilli is one of the most widely consumed vegetables because of their combinations, color, flavor, taste, and nutritional value. Apart from being a rich source of vitamin C, chilli has vitamins A and E, a low amount of proteins, fats, carbohydrates, and traces of minerals.6 Capsaicin has great medicinal value and has been evaluated in the treatment of painful conditions such as rheumatic diseases, cluster pains, painful diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, etc 7 Studies conducted recently have revealed that capsaicinoids can effectively treat a number of disorders affecting sensory nerve such as arthritis, cystitis, HIV and others.8

Induce mutagenesis is a quick, cost-effective, robust, and proven mutation breeding approach to accelerate the process of developing and selecting novel economic traits in various crops (FAO/IAEA). The amount of genetic variation is essential for the selection of various crops,9 and the success of the selection of crop improvement exclusively depends on the selection process.10 A chemical mutagen has mild effects on plant material as reported by Oladosu et al 11 An advantage of chemical mutagens is that they can be applied without complicated equipment or facilities. A large number of chemical compounds are available in which a small number of chemicals have been used as mutagens tested on plants,12 and only restricted alkylating agents used in mutation breeding. Over 80 % of crop varieties reported to developed by using chemical mutagens, especially alkylating (IAEA, 2015), obtained via chemical mutagenesis were induced by alkylating agents. Among alkylating agents, three chemical compounds are significant alkylating mutagens: ethyl-methane sulphonate (EMS), 1-methyl-1-nitrosourea (MNU), and 1-ethyl-1-nitrosourea (ENU) and accounted to 60 % plant varieties have developed from these three alkylating agents.12 Heavy metals induce mutagenic effects in plants as well as animals and may result in deleterious meiotic and mitotic effects. These heavy metals altered the pattern of recombination in both model and crop plants and affected cellular processes of meiosis.13 Heavy metals may be used as mutagens to induce phenotypic and genotypic changes in crops, and mutations could be selected as viable and useful mutants and can be recommended for mutation breeding,14.15.

Molecular markers are important tools for the identification and characterization of mutant genotypes and also for studying the organization and assessment of genomes in different crops.16 Various useful molecular (DNA) markers have been developed for the characterization of genetic diversity within different mutants of a single species. These mutants are characterized through the differences of nucleotide sequences because such sequences are unaffected by season, location, agricultural practices, and growth and developmental stages of the plant.17 The molecular markers such as Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP), Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism (AFLP), Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and Single Sequence Repeat (SSR) markers have developed to characterized different mutant lines of C. annuum L. Single sequence repeat (SSR) markers shows multi-allelic and co-dominant type of variation among mutants and represent high reproducibility.18 SSR markers are used for the assessment of genetic diversity, and in study of genetic mapping, gene tagging, marker-assisted selection and identification of varieties at molecular level.19.

Information of genetic variations of crop plant species occurring naturally or via induced mutagenesis is essential in crop improvement for the collection, conservation, and utilization of plant genetic resources. In induced mutation breeding, speed and accuracy of mutant selection depends on precise estimations of genetic divergence in isolated and selected mutant lines using different markers viz. morphological, biochemical, physiological, and molecular markers. Assessment of genetic diversity based on phenotypes in mutation breeding indicated to environmental factors might be associated with growth and developmental process which affects the morphology of a plant.20 Although, morphological markers are gives conventional data to characterize the mutant lines. Therefore, molecular markers are required to validate the induced genetic diversity raised in various polygenic traits viz., quantitative, nutrient and biochemical and molecular markers has no or least effects of environmental factors. Mutant population has been generated in C. annuum L. for functional analysis of genes and genetic resources in breeding program. A mutant populations of chilli and tomato have been generated by using EMS mutagen,[21], [22], [23] and a total of 1,650 and 5,023 mutant lines of variety ‘Maor’ and ‘Yuwol-cho’ of C. annuum L. were generated to characterize the genes affecting the plant architecture and flowering, respectively,24.25 Srivastava and Mangal,26 reported resistant line to Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) through screening of novel resistance alleles encoding TEV resistant gene by using Induced Local Lession IN Genome (TILLING) approach. Main objective of the study is the selection of efficient concentrations/doses of mutagens which can induce useful mutation in chilli crop.

The present study focus on (i) studying the comparative changes in morphological and biochemical parameters because of the impact of the induced mutations in high-yielding mutant lines and (ii) assessment of changes in the molecular characterization of the mutant lines of C. annuum L. using SSR marker technique.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Plant material and field experiments

NS 1101 is an elite variety of C. annuum L. in several states of India. Variety NS 1101 was produced by crossing between var. PLR1 and NS 1701 DG. Eight mutant lines from one genotype were used in this study. The genotype NS 1101 was provided by the Namdhari Seed Corporation, Nawanshahr, Punjab. The characteristics of chilli variety NS 1101 were described in Supplementary Table S1. M1 seeds were generated from M0 seeds through mutagenic treatments of alkylating agents and heavy metals in an experimental field at Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh (27° 54′ 1.3788′' N, 78° 4′ 20.2116′' E), India. The present study was conducted during the period from October 2018 to April 2022 up to the M4 generation. Alkylating agents such as EMS and MMS commonly used in mutation breeding while heavy metals like Cd(NO3)2 and Pb(NO3)2 have been less documented as mutagens in the improvement of the genetic material of crops.

2.2. Details of the 2018–2022 field trials

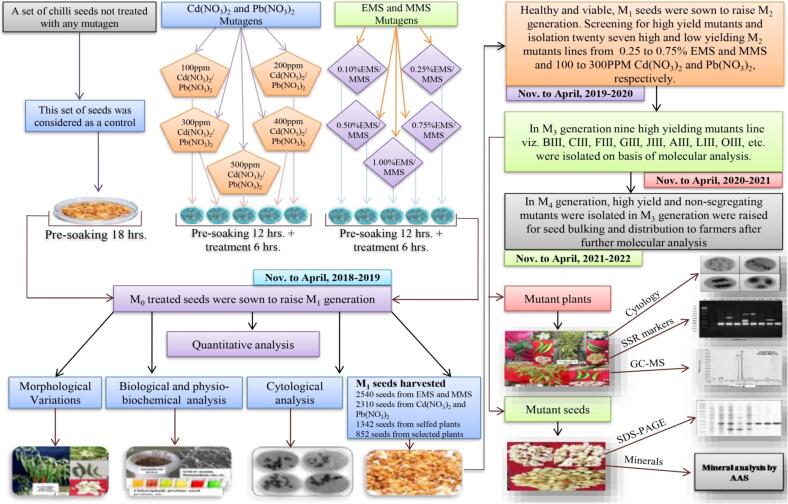

Healthy and viable seeds (10.50 %, moisture) of C. annuum L. were treated with different concentrations of alkylating agents [such as EMS and MMS (0.10 %, 0.25 %, 0.50 %, 0.75 % and 1.00 %)] and heavy metals [Cd(NO3)2 and Pb(NO3)2 (100 ppm, 200 ppm, 300 ppm, 400 ppm and 500 ppm)] for six hours. During mid-October 2018, the total 5,460 seeds (500 per treatment and a set of control) were sown in RCBD (Randomized Complete Block Design) design as 20 replicates of each treatment on 35.50 × 56.00 m size agriculture field at 55.00 cm inter row and 27.00 cm intra row spacing to raise M1 generation (Supplementary figure S1 and S2). All recommended agriculture practices such as fertilizer (nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium), irrigation and weeding were applied time to time. During first week of April 2019, all M1 seeds were harvested and stored to riase subsequent generations. In same year, during mid-October 2019, healthy and viable M1 seeds from each treatment were sown in same agriculture land to raise M2 populations and total 45, 340 M2 seeds generated from M1 populations in first week of April 2020. In same year, all the seeds were also sown according mutagenic treatment and out of them 34,200 seeds were survived and screen in M3 generation. The description of mutant lines grown/selected from M1 to M3 generation in C. annuum L. was represented in Supplementary Table S2. The mean data from 20 replicates on seven quantitative traits were taken. Based on quantitative analysis, 14 high and low yielding mutant lines were isolated from 0.10 %EMS, 0.25 %EMS, 0.50 %EMS, 0.10 %MMS, 0.25 %MMS, 100 ppm Pb(NO3)2, 200 ppm Pb(NO3)2 and 100 ppm Cd(NO3)2. In the first week of April 2021, all the seeds of high and low yielding mutants were harvested separately and stored for raising subsequent generations. From the M3 generation onwards, we advanced only high-yielding and non-segregating mutant lines to raise the M4 generation. In mid-October 2021, 12 healthy seeds from each high-yielding mutant plant, and the total of 2,800 seeds were sown to raise the M4 generation. The effective selection process led to the isolation of eight high-yielding and non-segregating mutant lines viz., CIII, BIII, AIII, GIII, LIII, NIII, JIII, and KIII in lower and medium concentrations of alkylating agents and heavy metals in M3 generation. The data was recorded on quantitative, biochemical, and molecular levels to develop a relative profile of each mutant line. M4 generation was raised for the assessment of purity of the selected mutant line by using single sequence repeat (SSR) markers and GC–MS analysis, and then seeds were distributed among the farmers. The mutagenic treatments of seeds, quantitative traits, and handling of mutant plant population-based selection were up to M4 generation (2018 – 2022) (Fig. 1). Eight putative mutant plants (lines) were identified and characterized based on quantitative traits with high significant yield and yield contributing traits from M3 populations of C. annuum L.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of chemical induces mutagenesis and selection processes followed during 2018–2022.

2.3. Morphological characterization

Morphological mutations were observed with visibly altered characters in selected mutant lines from the time of seedling emergence to plant maturity. Mutant lines were screened and isolated from induced populations and characterized into six morphological characters (plant height, leaf, branch, flower, fruit, and root) based on differential morphology. These five characters were further characterized into discrete phenotypes i.e. plant height as a tall and dwarf mutant; leaf with different shape and color; fruit with different color and texture; flower with the variable number of petals and distinct color, and root with more and fewer fibers with variable length.

2.4. Agro-economical study

In M4, data on yield and yield-contributing traits were collected from each replicate of selected mutant lines. Agro-economical traits viz. plant height, number of branches per plant, number of fruits per plant, 1000-seeds weight (g), and fresh yield per plant (g) were studied in selected mutant lines. The statistical mean value, genotypic coefficient of variation (GCV), heritability (h2), and genetic advance (GA as % of mean) was estimated (R.K. Singh and B.D. Choudhary, 1985) on the selected traits and based on these statistical analysis mutant lines indicates excellent survival and trait performance.

2.5. Seed protein and mineral analysis

Protein content of high yielding mutant lines was estimated by using “Bradford, Coomassie Blue G dye” method (M. M. Bradford, 1976). The content of essential minerals viz., cadmium (Cd), Zinc (Zn), Iron (Fe) and Cooper (Cu) was estimated from the seeds of high yielding mutant lines and parent genotype of C. annuum L. by using Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (ASS) after wet digestion as described by (P. K. Gupta, 2004).

2.6. Gas Chromatography/Mass spectroscopy (GC/MS) analysis

High yielding mutant lines from M4 generation of C. annuum L. were selected to analyze phytochemicals e.g., Capsaicin and Capsaicinoids through GC–MS technique. Healthy and fresh chilli fruits were collected from high yielding mutant lines and dry under shade condition. After drying, chilli fruits were ground through mechanical blender to form a fine powder. Fine chilli powder was transferred into a sealed container having proper labeling and crude extract of samples was prepared through Soxhlet methanol extraction method. After extraction process, extract was taken into a beaker and kept on hot plate to heat at 30–40 °C until solvent become evaporated and dried extract stored in refrigerator at 4 °C. The gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy technique was applied at Biotech Park, Lucknow, to analyze the phytochemical composition in selected high yielding mutant lines. GC–MS analysis was applied followed to Pino et al., (2007) by using Thermo Scientific TSQ 8000. GC–MS was equipped with fused silica capillary column, HP-50 (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) and used to separate capsaicin and capsaicinoids from chilli fruits. Oven temperature was maintained at 50 °C for two minutes and then increased to 280 °C per minute. Helium (He) was used as a gas carrier and flow rate of helium was maintained to 1 mL/min. Flame ionization detector was operated as an electron impact mode of 70 eV at 230 °C for mass spectra determination (MSD). The phytochemicals composition was determine through mass spectra and retention time of know phytochemical by using automated library search on National Institute of Standard And Technology (NIST) MS search program. The identification of chemical constituents of chilli cultivars was carried out by using chemical standards in the system. The results obtained from the GC/MS analysis were represented in the form of peak area normalized (%).

3. Mutant characterization through molecular study

3.1. Lyophilization and isolation of DNA

Leaves of eight selected mutant plants were collected after 35 days of seed sowing and lyophilization was carried out to preserve their DNA in native form, overnight. Lyophilization of biological material of selected mutant plants was done by following conditions at −70°C under vacuum 10–12 miliTorr. Genomic DNA of selected mutant plants was extracted or isolated from lyophilization leaf material using slightly modified CTAB (Acetyl Trimethyl-Ammonium Bromide) (Sabouri et al. 2009). The extracted DNA of each selected mutant was confirmed by electrophoresis on 1.0 % agarose gel. Approximately 25–30 ng of DNA was used as a template in polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

3.2. SSR markers and PCR amplification

All experimental management practices were done as per standard protocol. The genetic diversity in selected genotypes was characterized through Simple Sequence Repeat (SSR) primers analysis at Rajeev Gandhi Center for Biotechnology (RGCB), Kerala, India.

Single Sequence Repeat (SSR) markers study was performed by following the standard protocol suggested by Temnykh et al. (2000). Selected mutant genotypes and parent genotype were subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification. Total eleven SSR markers were used to characterize the genetic diversity induced in high yielding QTL traits liking to their genome of selected and control genotypes. Polymerase chain reaction was performed by using Techne Thermocycler model number − TC-412 in a 10 μl reaction plate of 96 wells. The PCR kit containing of 2X PCR master mix with KAPA2G Fast DNA polymerase (used in 0.2U per 10 μl reaction), dNTPs (0.2 mM each at 1X), MgCl2 buffer and KAPA2 Fast PCR buffer, and forward and reverse primer were added to PCR reaction for the DNA amplification of selected and control genotypes. Polymerase chain reaction was started first denaturing of the DNA at 94 °C for 1 min followed to 35 cycle at same temperature, 55–65 °C primer annealing temperature for 1 min and 72 °C maintained for primer extension (50sec. – 1 min). After DNA amplification, PCR product was subjected to electrophoresis on 5 % polyacrylamide under aqueous solution of 0.5X TBE (Tris-Borate-EDTA) buffer at 100 V for 90 min to resolve the DNA bands. These DNA bands containing γ32P-AT were visualized and resolved under ultraviolet light system for the confirmation of genetic diversity with the selected and control genotypes.

3.3. SSR markers data analysis

DNA bands obtained by gel electrophoresis was scored as either present (1) or absent (0) in SSR markers analysis used for the genetic diversity confirmation among chilli genotypes. Molecular data of DNA bands was subjected to cluster analysis by using NTSYS statistical package (version 4.0.) to generate dendrogram based on genetic similarity/dissimilarity through Unweighted Pair Group Arithmetic Mean Method (UPGMA). The genetic diversity parameters viz., allele number, allele frequency, heterozygosity and Polymorphic Information Content (PIC) were generated by using the Power Marker software (version 3.25.) suggested by Liu and Muse (2005).

The Polymorphic Information Content (PIC) for each marker was calculated by given formula.

Where, fi= (sum of alleles or bands)/no. samples.

4. Results

4.1. Morphological and quantitative characterization of mutants

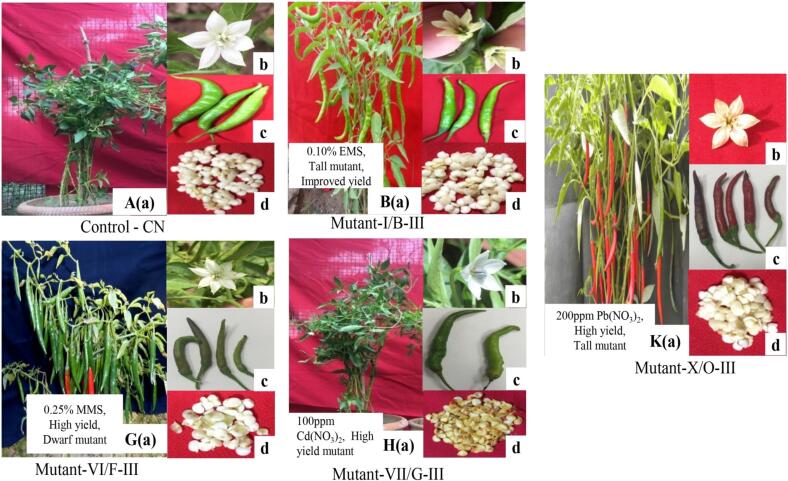

Mutagenic effects of EMS and MMS, and Cadmium nitrate and Lead nitrate [Cd(NO3)2 and Pb(NO3)2] were studied on morphological, quantitative, cytological, physiological and molecular traits in Capsicum mutants. Mutants with high and improved yield were represented in Fig. 2 and listed Table 1, Table 2. To assess the comparative effects of different concentrations of intra and intergenic treatment, yield and yield-attributing traits were analyzed statistically. DNA profiling and phytochemical analysis of selected mutants in M3 generation was also performed.

Fig. 2.

Morphological characterization of selected high yielding mutant lines of C. annuum L.

Table 1.

Selected high/improved yielding mutants of C. annuum L. for molecular analysis by SSR markers (M3 Generation).

| S. No. | Control/Mutant codes | Mutagens used | Mutagenic Conc. | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Control | − | − | Normal yield |

| 2. | C-III | EMS | 0.50 % | Tall mutant with improved high yield |

| 6. | A-III | EMS | 0.10 % | Tall mutant with high yield |

| 7. | B-III | EMS | 0.25 % | Semi-dwarf mutant with high yield |

| 3. | F-III | MMS | 0.25 % | Dwarf mutant with high yield |

| 4. | G-III | MMS | 0.50 % | Tall bushy mutant with high yield |

| 5. | J-III | Cd(NO3)2 | 100 ppm | Tall and bushy mutant with high yield |

| 8. | L-III | Cd(NO3)2 | 200 ppm | Semi-dwarf mutant improved yield |

| 9. | O-III | Pb(NO3)2 | 100 ppm | Tall mutant with high yield |

Table 2.

Yield parameters in selected high yielding mutants of C. annuum L. (M3 Generation).

| S. No. | Mutant/Code | Mutagenic Conc. |

Yield Parameters |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Plant Height (cm) |

No. of Branches/Plant | No. of Fruits/Plant | Fresh Yield/Plant (g) | |||

| 1. | Control/CN | − | 78.34 | 11.00 | 30.00 | 93.80 |

| 2. | C-III | 0.50 %/EMS | 91.74 | 12.66 | 23.34 | 113.45 |

| 3. | A-III | 0.10 %/EMS | 93.00 | 10.00 | 34.65 | 112.34 |

| 4. | B-III | 0.25 %/EMS | 82.25 | 11.33 | 31.14 | 100.00 |

| 5. | F-III | 0.25 %/MMS | 53.00 | 11.33 | 29.67 | 90.00 |

| 6. | G-III | 0.50 %/MMS | 84.44 | 6.26 | 27.40 | 98.56 |

| 7. | J-III | 100 ppm/Cd(NO3)2 | 94.00 | 12.28 | 31.38 | 102.04 |

| 8. | L-III | 300 ppm/Cd(NO3)2 | 55.25 | 10.67 | 25.90 | 99.00 |

| 9. | O-III | 200 ppm/Pb(NO3)2 | 92.63 | 12.60 | 32.44 | 112.33 |

4.2. Control

Plant with normal height, normal branching pattern, large dark green leaves, normal flowers with six white petals, normal white anthers, light green fruits, normal rounded white seeds, and normal yield (Fig. 2). In control, plant height, fruits per plant, and yield per plant were recorded at 83.20 cm, 29.00, and 93.60gm, respectively. The highest genetic coefficient of variance (GCV%) and genetic heritability (h2bs%) were recorded for yield per plant and fruits per plant, respectively [control] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Statistical and genetic components analysis of yield and yield attributing traits in selected Capsicum mutants in M4 generation.

| Trait |

Genetic component |

High yielding mutant selected from M4 generation |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN | AIII | CIII | GIII | BIII | LIII | FIII | JIII | OIII | ||

|

Plant height (cm) |

Mean ± S.E. | 83.2b ± 0.6 | 93.8a ± 1.2 | 76.4c ± 0.8 | 85.8b ± 1.6 | 96.0a ± 1.0 | 66.6d ± 1.7 | 53.4f ± 0.7 | 59.8e ± 1.6 | 94.6c ± 1.2 |

| GCV% | 1.67 | 3.04 | 2.10 | 1.92 | 2.65 | 2.12 | 1.10 | 1.56 | 2.10 | |

| h2bs% | 45.23 | 47.80 | 51.20 | 48.34 | 56.12 | 53.23 | 61.20 | 45.38 | 50.13 | |

| GA% | 2.10 | 3.40 | 2.92 | 4.56 | 2.56 | 3.24 | 2.15 | 3.19 | 4.12 | |

| Branches/plant | Mean | 8.6cde ± 0.7 | 10.4abc ± 1.0 | 6.6e ± 0.9 | 12.8a ± 0.7 | 6.4e ± 0.5 | 10.0bcd ± 0.9 | 12.4ab ± 0.8 | 6.4e ± 0.7 | 7.6de ± 0.9 |

| GCV% | 1.92 | 1.34 | 2.16 | 2.45 | 1.86 | 1.92 | 2.34 | 3.12 | 1.65 | |

| h2bs% | 36.67 | 41.23 | 38.80 | 42.12 | 34.56 | 45.78 | 44.32 | 39.10 | 47.45 | |

| GA% | 1.45 | 2.34 | 2.10 | 3.65 | 2.92 | 1.90 | 3.26 | 1.76 | 2.10 | |

| Fruits/plant | Mean | 29.0b ± 1.3 | 30.6ab ± 1.3 | 29.6b ± 0.7 | 31.40ab ± 0.9 | 29.8b ± 1.2 | 32.8a ± 1.3 | 30.2ab ± 1.0 | 29.8b ± 1.0 | 31.2ab ± 1.6 |

| GCV% | 2.45 | 3.78 | 1.92 | 2.35 | 2.92 | 1.83 | 2.35 | 1.45 | 2.84 | |

| h2bs% | 51.23 | 56.76 | 61.34 | 58.34 | 52.14 | 59.00 | 62.14 | 45.90 | 51.12 | |

| GA% | 1.78 | 2.30 | 1.92 | 4.10 | 2.00 | 2.94 | 3.12 | 1.87 | 4.30 | |

| 1000-Seed weight (gm) | Mean | 6.8ab ± 0.6 | 7.2ab ± 0.6 | 6.6ab ± 0.7 | 6.0b ± 0.7 | 8.0a ± 0.7 | 6.6ab ± 0.9 | 6.6ab ± 0.5 | 6.2b ± 0.8 | 6.4b ± 0.8 |

| GCV% | 1.13 | 1.85 | 2.10 | 1.92 | 2.05 | 1.34 | 2.83 | 1.92 | 1.45 | |

| h2bs% | 26.67 | 32.14 | 28.90 | 36.76 | 31.23 | 38.00 | 41.34 | 28.90 | 34.45 | |

| GA% | 1.30 | 1.56 | 2.10 | 2.78 | 1.34 | 1.92 | 3.00 | 2.10 | 2.16 | |

|

Yield/plant (gm) |

Mean | 93.6d ± 0.7 | 97.6c ± 1.0 | 102.4b ± 0.7 | 95.8cd ± 1.6 | 103.2b ± 0.8 | 107.8a ± 0.7 | 97.2d ± 0.7 | 103.2b ± 0.6 | 96.8c ± 0.7 |

| GCV% | 2.66 | 3.12 | 2.94 | 3.34 | 2.87 | 3.45 | 1.93 | 2.56 | 2.94 | |

| h2bs% | 49.30 | 54.23 | 59.12 | 55.45 | 61.20 | 65.39 | 55.00 | 57.10 | 50.36 | |

| GA% | 2.78 | 4.55 | 3.12 | 2.82 | 3.67 | 5.12 | 2.30 | 4.12 | 2.76 | |

4.3. Mutant-OIII

Tall mutant with high number of fused branches, more number of small light green leaves, flowers with six creamy petals, dark green anthers, dark red fruits, light yellow large seeds, increased root length, and increased yield (Fig. 2). Plant height in mutant-OIII was recorded to be 94.60 cm, while fruits per plant and yield per plant were recorded to be 31.20 and 96.80gm, respectively, and the highest GCV% and h2bs% were estimated to be 2.94 % and 51.12 % for yield per plant and fruits per plant, respectively [200PPM Pb(NO3)2] (Table 3).

4.4. Mutant- BIII

Tall plants with a higher number of branches, large fruits with thick texture, light yellow flowers with six curly petals, normal seeds, and increased yield (Fig. 2). Plant height was measured to be 96.00 cm, whereas fruits per plant and yield per plant were recorded to be 29.80 and 103.20gm, respectively, and the highest values of GCV% and h2bs% were recorded at 2.87 % and 61.20 % for yield per plant [0.10 % EMS] (Table 3).

4.5. Mutant-FIII

Dwarf mutant with increased woody branches, dark green fruits with thin texture, light green small leaves with rounded bold seeds, late fruiting, and improved yield (Fig. 2). Mutant-FIII showed stunted growth with dwarf height and was recorded to be 53.40 cm and fruits per plant and yield per plant were recorded to be 30.20 and 97.20 g, respectively. The highest genetic coefficient of variance and genetic heritability was estimated to be 2.83 % and 61.20 % for 1000-seeds weight and plant height, respectively [0.25 % MMS] (Table 3).

4.6. Mutant-JIII

Dwarf mutant with woody stem and increased no of branches, larger dark green leaves, flower with white petals and free light green anthers, increased no. of dark red fruits, increased yield (Fig. 2). A plant with a height of 59.80 cm was selected as mutant-JIII and fruits per plant and yield per plant in this mutant were recorded to be 29.80 and 103.20gm, respectively. Maximum GCV% and h2bs% were recorded to be 3.12 % and 57.10 % for branches per plant and yield per plant, respectively [100PPM Cd(NO3)2] (Table 3).

4.7. Cytological and stomata behavior

A cytological study carried out in 45 days selected mutant plants to understand the effects of mutagens in the M4 generation. The chromosomal aberrations e.g. univalents, multivalents, laggards, stray chromosomes, etc., were observed at meiotic-I and meiotic-II stages in stained pollen cells under a microscope. The mutation frequency in chromosomes varies among the selected mutants and the highest mutation frequency was recorded to be 7.12 % and 6.00 % in mutant O-III and L-III at meiotic-I and meiotic-II stages, respectively. The lowest mutation frequency was 2.60 % and 1.86 % in mutant B-III at the meiotic-I and meiotic-II stages, respectively. The highest total mutation frequency in the chromosome was recorded to be 14.42 % in mutant J-III, whereas the lowest was recorded to be 4.46 % in mutant B-III (Table 4).

Table 4.

Cytological and stomata behavior statistical analysis in selected mutant plants of C. annuum L.

| Mutant Code | Mutagen used |

Meiotic-I |

Meiotic-II |

Total aberrations |

Stomata length |

Stomata width |

Number of stomata |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mean ± S.D. C.V. |

Mean ± S.D. C.V. |

Mean ± S.D. C.V. |

Mean ± S.D. C.V. |

Mean ± S.D. C.V. |

Mean ± S.D. C.V. |

||

| Control | − | 0.00f ± 0.00 0.00 |

0.00f ± 0.00 0.00 |

0.00f ± 0.00 0.00 |

12.56d ± 0.67 5.33 |

2.92bc ± 0.09 3.08 |

14.00a ± 1.04 7.42 |

| C-III | EMS | 3.12de ± 0.23 7.37 |

2.00e ± 0.15 7.50 |

5.12de ± 0.23 4.49 |

12.92cd ± 0.72 5.57 |

2.40e ± 0.09 3.75 |

13.00 ± 1.00 7.69 |

| A-III | EMS | 3.56d ± 0.25 7.02 |

2.43d ± 0.17 6.99 |

5.99de ± 0.23 3.83 |

13.24bc ± 0.72 5.43 |

2.80c ± 0.10 3.57 |

14.00a ± 1.00 7.14 |

| B-III | EMS | 2.60e ± 0.21 8.07 |

1.86e ± 0.09 4.83 |

4.46e ± 0.21 4.70 |

13.00cd ± 0.83 6.38 |

2.56d ± 0.09 3.51 |

15.00a ± 1.08 7.20 |

| F-III | MMS | 4.45cd ± 0.30 6.74 |

2.90c ± 0.12 4.13 |

7.35cd ± 0.31 4.22 |

14.10bc ± 0.81 5.74 |

3.12ab ± 0.11 3.52 |

15.00a ± 1.08 7.20 |

| G-III | MMS | 4.80c ± 0.28 5.83 |

3.12c ± 0.13 4.16 |

7.92c ± 0.34 4.29 |

14.36ab ± 0.92 6.40 |

3.00bc ± 0.12 4.00 |

13.00ab ± 0.98 7.53 |

| J-III | Cd(NO3)2 | 8.90a ± 0.37 4.15 |

5.34ab ± 0.32 5.99 |

14.24ab ± 0.32 2.24 |

16.00a ± 0.75 4.68 |

3.45a ± 0.12 2.47 |

11.00b ± 0.98 8.90 |

| L-III | Cd(NO3)2 | 9.10a ± 0.32 3.51 |

6.00a ± 0.21 3.50 |

15.10a ± 0.40 2.64 |

16.30a ± 0.78 4.78 |

3.12ab ± 0.10 3.20 |

12.00ab ± 0.83 6.92 |

| O-III | Pb(NO3)2 | 7.12b ± 0.28 3.93 |

5.12b ± 0.18 3.51 |

12.24b ± 0.28 2.28 |

15.20ab ± 0.67 4.40 |

3.10ab ± 0.10 3.22 |

14.00a ± 0.88 6.28 |

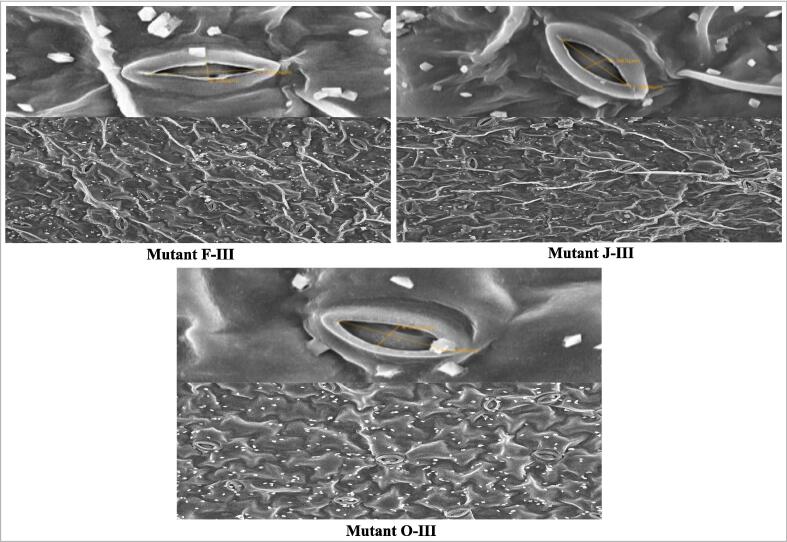

Stomata study was conducted in 30-day-old mutant plants through scanning electron microscope (SEM) to understand the effects of mutagens in selected mutant plants in M4 generation. The parameters e.g. stomata length, stomata width, and number of stomata per leaf surface area were analyzed through a scanning electron microscope. The maximum stomata length and stomata width were measured to be 16.30 µm and 3.45 µm in mutant L-III and mutant J-III, while the lowest stomata length and stomata width were measured to be 12.92 µm and 2.40 µm in mutant C-III, respectively. The highest number of stomata per leaf surface area was measured to be 15.00 in mutant B-III and F-III, while the lowest number of stomata per leaf surface area was 11.00 in mutant J-III (Fig. 3 and Table 4).

Fig. 3.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) in selected mutants from M4 generation of chemical induced populations of C. annuum L.

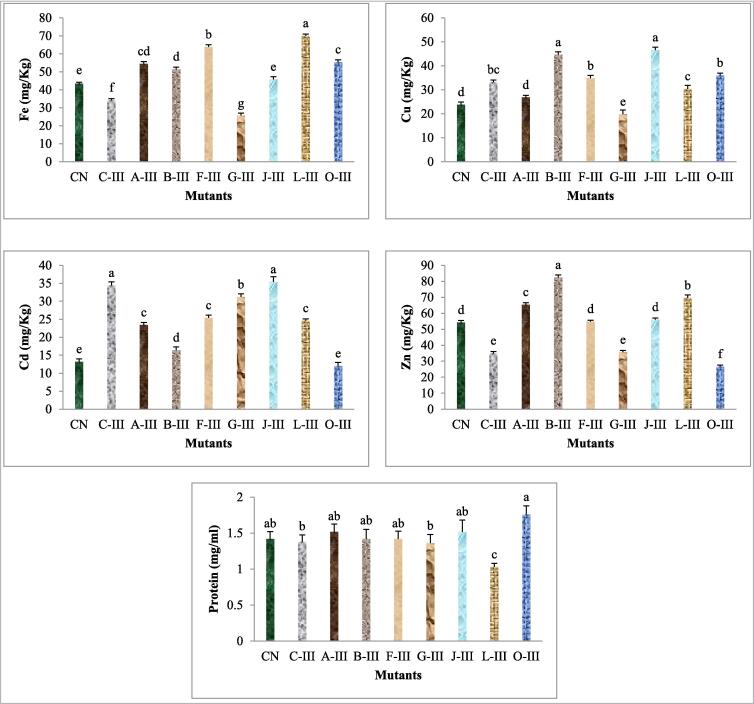

4.8. Protein and mineral analysis

Estimated mean value, standard deviation (S.D.), and least significant differences (LSD) for the seed protein and mineral content (i.e. iron, copper, cadmium, and zinc) of high-yielding mutants are presented in the table. The seed protein in half of the isolated high-yielding mutants showed an insignificant mean value, while half of the mutants exhibited a significant mean value and improvement over the control plant. The highest significant increase in seed protein content (1.76 mg/ml) was recorded for the mutant O-III selected from 200 ppm Pb(NO3)2 treatment, whereas the lowest seed protein content (1.03 mg/ml) was recorded for the mutant L-III selected from 200 ppm Cd(NO3)2 treatment as compared to 1.46 mg/ml in the control. The mean value for the mineral elements in the fruits of most mutant lines showed considerable positive deviation from the control means. The maximum significant increase in the iron content (70.00 and 63.8 mg/kg) was recorded in the mutant lines L-III and F-III from 200 ppm Cd(NO3)2 and 0.25 %MMS treatments, respectively. The copper content was the highest significant (46.60 and 44.60 mg/kg) in the mutant lines J-III and B-III selected from 100 ppm Cd(NO3)2 and 0.25 %EMS treatments, respectively, as compared to 23.80 mg/kg of control mean value. The content of cadmium and zinc in mutant lines also showed variability and most of them represent significantly enhanced mean value as compared to control. The highest mean value in cadmium and zinc elements was recorded to be 35.4 mg/kg and 82.4 mg/kg in mutant J-III and B-III, respectively (Fig. 4). There were not many differences in the least significant differences (LSD) for seed protein contents between mutant lines and control plants, which implied that further improvement in seed protein cannot be expected through selection. However, differences in the mineral content of mutant lines support the possibilities of such mutants for further improvement.

Fig. 4.

Protein and micronutrient profiling of selected mutant plants.

4.9. Phytochemical analysis of Capsicum mutant lines

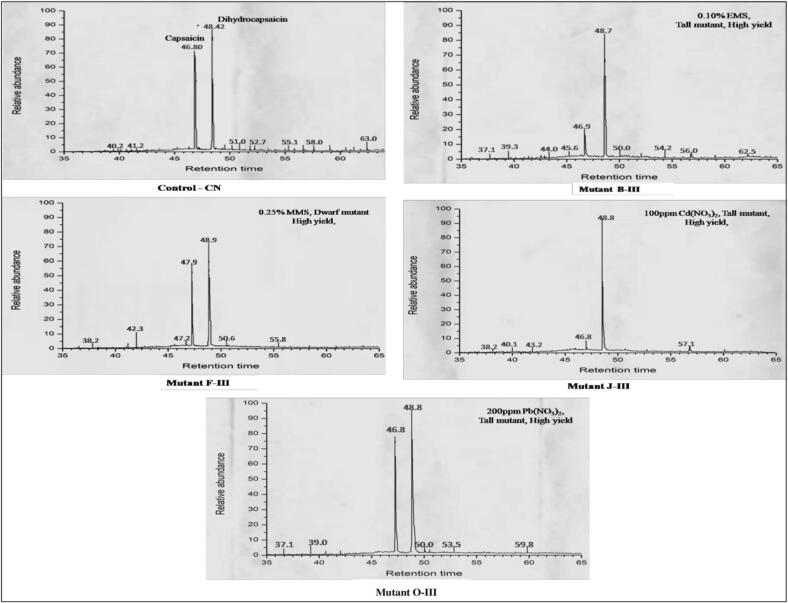

The profile of alkaloid compounds of different chilli mutant plants was obtained by using the optimized protocol. Two CRCs (capsaicinoid-related compounds) such as capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin in nine genotypes were indicated by the relative content and comparison through GC–MS spectra between mutants and control. In the present study, two capsaicinoids (capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin), major contributors to chilli fruit pungency, are analyzed to determine the variations in these phytochemicals among eight high and improved yield mutants and compare them with their respective control. Phytochemical studies for capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin in eight high-yielding lines (B-III, C-III, F-III, G-III, J-III, O-III, L-III, and AIII) and their respective control (CN) were performed through GC–MS technique. All mutants and control plants showed different peak areas of capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin content and it is observed that the quantities of capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin showed a great variation among the mutants as compared to the control. The highest amount of capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin (89.00 and 93.93 %) was shown in mutant F-III and O-III while mutant L-III represents the highest amount of dihydrocapsaicin (99.34). Mutant A-III showed the lowest amount (56.23 and 73.034 %) of capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin in comparison to their respective control (Fig. 5 and Table 5). Phytochemical analysis indicates that the mutagens have the potential to induce phytochemical changes in Capsicum annuum L. at different concentrations.

Fig. 5.

GC–MS analysis in selected high yielding mutant lines of C. annuum L.

Table 5.

GC–MS analysis of selected high/improved yielded mutants of C. annuum L. in M3 generation.

| S. No |

Control/Mutant Code |

Mutagens used | Chemical compound |

RT Min:sec |

Height mV |

Area mV-sec |

Amount % area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | CN (Control) |

− | Capsaicin Dihydrocapsaicin |

46.80 48.42 |

178.34 204.51 |

345.230 945.443 |

78.342 90.543 |

| 2. | C-III | 0.50 %/EMS | Capsaicin Dihydrocapsaicin |

47.90 48.94 |

165.23 175.00 |

295.763 452.503 |

64.103 82.903 |

| 3. | A-III | 0.10 %/EMS | Capsaicin Dihydrocapsaicin |

46.83 48.87 |

192.45 214.34 |

376.921 1012.346 |

56.236 73.034 |

| 4. | B-III | 0.25 %/EMS | Capsaicin Dihydrocapsaicin |

46.91 48.75 |

182.00 193.67 |

765.034 478.341 |

83.234 54.203 |

| 5. | F-III | 0.25 %/MMS | Capsaicin Dihydrocapsaicin |

46.82 48.93 |

190.23 93.76 |

945.065 122.045 |

89.000 34.230 |

| 6. | G-III | 0.50 %/MMS | Capsaicin Dihydrocapsaicin |

46.75 48.80 |

145.03 165.40 |

342.872 467.341 |

71.763 76.003 |

| 7. | J-III | 100 ppm/Cd(NO3)2 | Capsaicin Dihydrocapsaicin |

46.92 48.86 |

175.09 193.56 |

856.725 1004.762 |

85.675 90.364 |

| 8. | L-III | 300 ppm/Cd(NO3)2 | Capsaicin Dihydrocapsaicin |

46.80 48.83 |

ND 218.03 |

ND 1432.823 |

ND 99.346 |

| 9. | O-III | 200 ppm/Pb(NO3)2 | Capsaicin Dihydrocapsaicin |

46.78 48.93 |

154.45 176.34 |

390.347 562.651 |

84.094 93.932 |

4.10. Molecular analysis

High-yielding mutants of Capsicum annuum L. from M3 generation were selected and analyzed at the molecular level by using SSR markers for the detection of differences in variability among them.

Identification of high yield/improved mutant lines of Capsicum annum L. through SSR markers:

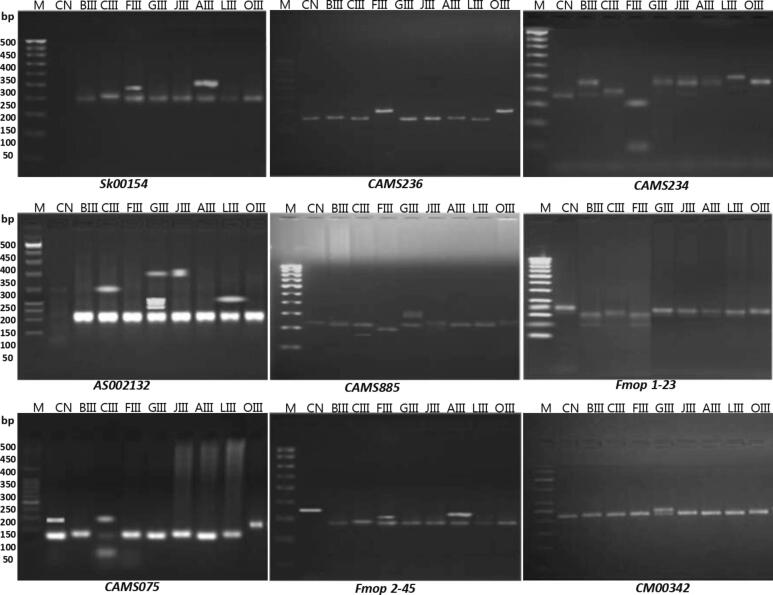

Total eleven SSR primers viz., Fmop 1–23, Fmop 1–64, Fmop 2–45, AS002132, CM00342, CAMS234, and Sk00154, etc. were used to screen nine genotypes for the amplification of chilli genomic DNA (Fig. 6). These primers showed more reproducible and highly polymorphic amplification pattern of DNA. Total 44 alleles were detected for all the seven polymorphic SSR loci with a range between 3 and 5 and average value of 4.00 alleles. The primers viz., Fmop 1–23, Fmop 2–45, CM00342, and Sk00154 has least allele number and allelic frequency ranging from 0.16 to 0.61, 0.14 to 0.52, 0.11 to 0.73, and 0.11 to 0.72, respectively. A maximum number of alleles was found to be five in other primers like Fmop 1–64, AS002132, and CAMS234 with allelic frequencies ranging from 0.09 to 0.40, 0.08 to 0.45, and 0.07 to 0.62, respectively. Genetic diversity in primers Fmop 1–23, Fmop 2–45, CM00342, and Sk00154 was measured from 0.333 to 0.322, while in primers like Fmop 2–45, CM00342, and AS0002132 was measured from 0.186 to 0.192, respectively. The total genetic diversity was measured to be 2.81 and average genetic diversity per locus was found to be 0.255 and the average polymorphic information content was measured to 0.603 (Table 6).

Fig. 6.

SSR amplification profile of nine primers, Lane M: DNA ladder with length (bp) on left. Lane 1–9: genotypes of the 9 C. annuum L. samples (CN III-O III).

Table 6.

Polymorphism information and amplification pattern of eleven primers combinations responded during SSR analysis of high yielding mutants of C. annuum L.

| S. R. No | Primer Code | Primer Sequences (5′-3′) | No of allele | Allele frequency | Genetic diversity | Allele size range (bp) | PIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. |

Fmop 1–23 |

F-CCAAACGAACCGATGAGTGAACA-CTC R-GACAATGTTGAAAAAGGTGGAA-GAC |

3 | 0.23 0.61 0.16 |

0.33 | 205–260 190–234 |

0.563 |

| 2. | Fmop 1–64 | F-AAGCTGAGCTGGCAAGGA-AAG R-TGAAAAGACGATTTTGTCTAAT-GCG |

5 | 0.40 0.15 0.21 0.13 0.09 |

0.19 | 155–183 182–219 |

0.342 |

| 3. | Fmop 2–45 | F-TCACCTCATAAGGGCTTTATCA-ATC R-TCCTTAACCTTACGAAACCT-TGG |

3 | 0.34 0.52 0.14 |

0.33 | 217–255 192–230 |

0.535 |

| 4. | AS002132 | F-GCTAATTACTTGCTCCGTT-TTG R-AATGGGGGAGTTTGTTT-TGG |

5 | 0.17 0.45 0.08 0.11 0.12 |

0.18 | 164–190 200–225 |

0.649 |

| 5. | CM00342 | F-CATGACCACCATGAGG-ATA R-GATAGCCACGAGCATAGT-ATT |

3 | 0.73 0.11 0.13 |

0.32 | 210–245 215–265 |

0.645 |

| 6. | CAMS234 | F-TCATGGAAAATTAACAACGC-ATA R-GGGGGTTGGAGAAAGAAAA-GTT |

5 | 0.62 0.12 0.10 0.04 0.07 |

0.19 | 174–190 180–205 |

0.648 |

| 7. | Sk00154 | F-CTACTACCGCTCCTGCT-CCT R-AGCTTCTGCTTTTGGTT-CGT |

3 | 0.72 0.11 0.16 |

0.33 | 234–276 207–242 |

0.536 |

| 8. | CAMS075 | F-ACTAATTACACATTCTGCATTTTCTC R-AGGCTCGAGTACCAGAAGA |

5 | 0.15 0.20 0.40 0.15 0.10 |

0.18 | 190–210 170–190 |

0.704 |

| 9. | CAMS236 | F-TTGTAGTTTGCTACCARRRGA R-ATGAATCCAGGGTTCCACAA |

3 | 0.35 0.30 0.35 |

0.32 | 205–215 194–204 |

0.597 |

| 10. | CAMS885 | F-AACGAAAAACAAACCCAATCA R-TTGAAATTGCTGAAACTCGAA |

4 | 0.30 0.25 0.25 0.20 |

0.25 | 191–200 178–192 |

0.693 |

| 11. | CAMS855 | F-AAGTGCAAGGAAGGGGACA R-CCTAACCACCCCCAAAAGTT |

5 | 0.10 0.30 0.10 0.20 0.30 |

0.19 | 165–180 190–200 |

0.725 |

| Total | − | − | 44 | − | 2.81 | − | 6.637 |

| Mean | − | − | 4.000 | − | 0.255 | − | 0.603 |

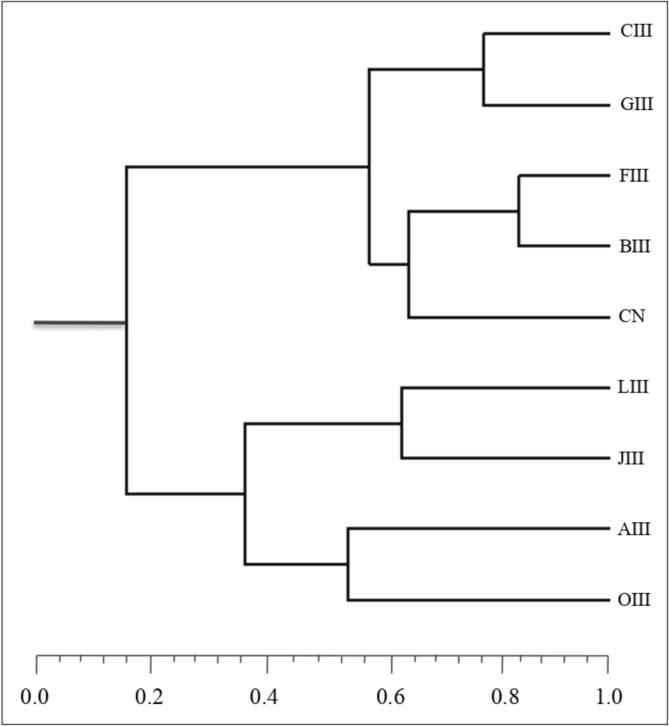

The comparison was made for all mutant plants including control genotypes based on SSR markers data and the distance range (Jaccard coefficient) was taken from 0.33 to 1.00. Lowest genetic dissimilarity was measured to zero which is found between the similar mutant lines (Table 7). The highest Jaccard coefficient was recorded to be 0.769 in mutant C-III and F-III followed by mutant L-III (0.750). The highest value of Jaccard coefficient in mutant J-III was found to be 0.667 and in mutant A-III was measured to be 0.615, while the lowest genetic distance in these mutants was found 0.500 and 0.364, respectively. In mutant O-III, the high Jaccard coefficient was found to be 0.615 and the lowest to 0.333. Genetic relationship among mutant plants with high yield and improved traits along with control plants was constructed in the form of a dendrogram by using binary data of SSR markers based on the unweighted pair group arithmetic mean method (UPGMA). In present study, mutant F-III (0.845) and mutant O-III (0.333) were observed to be genetically most divergent from their respective parent genotypes CN. HCA revealed that mutants and control populations were grouped into two clusters I and II. Cluster-I contains five members including control, while cluster-II comprises four members. The first cluster consisted of mutant CIII, GIII, BIII, FIII, and control, whereas the second cluster represented the mutant LIII, JIII, AIII, and OIII (Fig. 7).

Table 7.

Distance matrix based on Jaccard Coefficient of SSR data of control and selected high/improved yielding mutants of C. annuum L.

| CN | B-III | C-III | F-III | G-III | J-III | A-III | L-III | O-III | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN | 0.000 | 0.545 | 0.769 | 0.769 | 0.692 | 0.667 | 0.600 | 0.750 | 0.556 |

| B-III | 0.000 | 0.571 | 0.462 | 0.600 | 0.571 | 0.500 | 0.733 | 0.583 | |

| C-III | 0.000 | 0.571 | 0.765 | 0.571 | 0.615 | 0.643 | 0.583 | ||

| F-III | 0.000 | 0.765 | 0.667 | 0.500 | 0.733 | 0.583 | |||

| G-III | 0.000 | 0.500 | 0.538 | 0.571 | 0.615 | ||||

| J-III | 0.000 | 0.364 | 0.417 | 0.455 | |||||

| A-III | 0.000 | 0.583 | 0.333 | ||||||

| L-III | 0.000 | 0.545 | |||||||

| O-III | 0.000 |

Fig. 7.

Genetic relationship among control (CN) and selected high yielding mutant lines as revealed by amplification pattern using SSR markers through Jaccard’s coefficient and UPGMA clustering method.

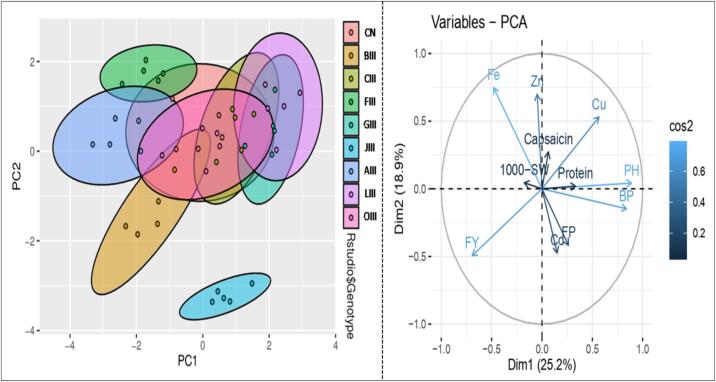

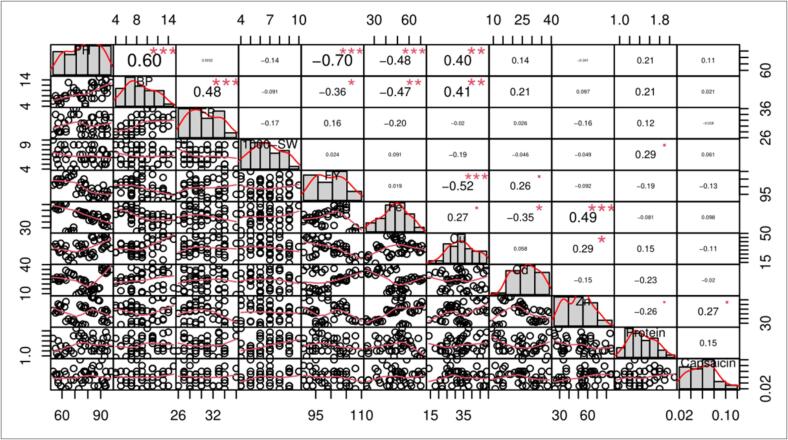

4.11. Correlation and multivariate analysis

In mutation breeding approaches, assessment of the relationship between yield and other traits is imperious. Hierarchical cluster analysis grouped mutants and control plants into different clusters. A dendrogram was constructed based on average linkage for Capsicum mutants and parent genotype. HCA revealed that mutants and control populations were grouped into two clusters I and II. Cluster-I contains five members including control, while cluster-II comprises four members. The first cluster consisted of the mutant CIII, GIII, BIII, FIII, and control, whereas the second cluster represented the mutant LIII, JIII, AIII, and OIII (Fig. 7).

Average value of five quantitative and six biochemical traits for two cluster groups are listed in the supplementary table 5. Results revealed that the first cluster has maximum mean value for plant height (69.5 cm), branches per plant (8.05), fruits per plant (30.15), fresh yield (101.15gm), iron (59.90 mg/kg), zinc (68.05 mg/kg) and protein (1.34 mg/ml), while second cluster represents maximum mean value for plant height (82.32 cm), branches per plant (9.80), fruits per plant (30.76), fresh yield (97.80gm), iron (40.88 mg/kg), zinc (41.48 mg/kg) and protein (1.49 mg/ml) (Supplementary Table S5).

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) revealed mutants viz. BIII, FIII, and JIII lie on the left side of the quadrate of the biplot, while mutants viz. OIII, LIII, GIII, CIII, and AIII lie on opposite sides in the biplot quadrate. The PCA revealed two principal components with 50.30 % variation (PC1 = 28.30 % and PC2 = 22.00 %). The magnitude of each quantitative and biochemical traits of different mutant lines represented in Fig. 8. Qualitative and biochemical traits of mutant line occur on same side represent higher value and vice versa. Cos2 value indicates the quality representation and contribution of quantitative and biochemical traits (in %) to principal components. The results revealed that FY, PH, BP, Cu, Zn, and Fe indicate good representation, while FP, 1000-seeds weight, capsaicin, protein, and Cd indicate weak representation (Fig. 8). Based on the magnitude and representation of quantitative and biochemical traits across various mutant populations, mutant LIII, JIII, AIII, and OIII formed the first cluster, whereas, in contrast, control (CN) and mutant BIII, FIII, GIII, and CIII formed second cluster. Pearson's correlation coefficient analysis helped to visualize the relationship between and among yield and yield-related traits. The results revealed a significant positive correlation coefficient relationship between yield and plant height and number of branches per plant as well as iron content. Whereas, there is no significant correlation between yield and remaining trait e.g. fruit per plant, 1000-seeds weight, Cu, Cd, Zn, protein, and capsaicin (Fig. 9).

Fig. 8.

Principal component analysis and quality of representation (cos2) of yield attributing and biochemical traits in selecetd mutant lines of C. annuum L., high cos2 values are colored in “light blue”, mid cos2 value are colored in “blue” and low cos2 values are colored in “dark blue”. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 9.

Correlation study between yield, yield attributing and biochemical traits in selected mutant lines of C. annuum L. PH, Plant height; BP, Branches per plant; FP, Fruits per plant; FY, Fresh yield per plant; Fe, Iron; Cu, Copper; Cd, Cadmium; Zn, Zinc; Protein; Capsaicin. Significant differences are represented as ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05.

5. Discussion

Mutation induction through chemical mutagens produce useful mutation with a high probability of producing dominant traits in the M1 generation which can be inherited in the next mutant generation,27.28 Mutation induction is the possible means to provide an enhanced level of genetic diversity among crops thus obtaining genetic variability in limited traits of a particular genotype.29.

Khan et al.,30 suggested the utilization and role of morphological markers in characterization and assessment of morphological characters of various germplasms and considered morphological traits are influenced by environmental. Different morphological changes were observed in several mutant lines at different plant growth and development stages. A mutant line with larger leaf with long petiole was observed. Manzila et al.,31 reported the leaf character such as leaf length and width was highly heritable and observed mutant lines with stunted growth, low branches, narrow leaves and enhanced number of corolla. Mutations in plant habit, fruits, and leaves induced by EMS were also reported in Capsicum annuum L.,32.33 The mutations in sepals, petals and ovule were observed34 and variable number of carpal and variations in flower color.35 The potential of the genotype-dependent mechanism of flower mutants is very useful in maintaining the genetic purity of the crop varieties in the next generation, as reported by Devi & Mullainathan,.36 Laskar et al.,37 reported that flower mutations may be correlated with the concentration or dose of the mutagens.

Enhanced quantitative traits were observed in selected mutant plants and compared with their respective control (Table 3). Karim et al.,38 reported quantitative changes in various chilli genotypes and suggested the association with genetic diversity. The genetic components viz., genetic coefficient of variance (GCV), heritability (h2s) and genetic advance (GA) showed variations among selected mutant plants and indicated minimum effects of environmental factors on expression of genes and significant amount of variance is considered to control by genetic composition of chilli genotypes (Table 3). Falconer and Mackay,39 suggested low percent of heritability at value range from 0 – 30 %, moderate at from 30 to 6-% and high heritability at more than 60 %. In the present study, broad sense heritability (h2s) was moderate for most of the traits while some traits have high value of heritability. Omolaran Bello et al.,40 suggested that combined heritability with genetic advance is superior to simple heritability which selected from superior individuals. High combined heritability in traits viz., number of fruits per plant and yield per plant indicates the traits are controlled by additive gene action. This standard selection procedure could be effective in selection and isolation of genotypes with desirable traits. The present study about genetic components was supported by different workers, 41 and Karim et al.,38 in yield per plant, and42 in number of fruits per plant. Yasmin et al.,43 reported significant increase in yield per plant and considered quantitative changes might be associated gene mutation arise in next generation. Decline in quantitative parameters could be attributed to chromosomal changes or physiological disturbances induced by mutagenic effects.44

A cytological study defines the specific response genotypes of mutant plants to the specific concentration or dose of a particular mutagen and also provides significant evidence for the selection of genotypes with desirable traits.45 In the present study, various meiotic aberrations viz., univalents, multivalents, bridges, laggard, stickiness, etc., were observed at meiosis-I and II in flower buds of selected mutant plants at different concentrations of all the mutagens (Table 4). Selected mutant plants showed the least effects of mutagens as compared to the previous generation, where, mutation frequency in chromosomes was high.

The mutations in stomata length, stomata width, and number of stomata per leaf surface area indicate changes in gaseous exchange activity and photosynthetic rate resulting enhanced productivity in selected mutant plants (Fig. 3 and Table 4). The stomata with increased size in several mutants was reported by different workers,46.47 However, stomata length and width were observed to reduce, while the number of stomata per leaf surface area was found to increase in some mutants as reported by different workers,48.49 Buckley et al.,50 reported the number of stomata per leaf surface area is directly related to photosynthetic rate, and stomata size and density are associated with different physiological processes.51.

The present study revealed that micronutrient deficiency of crops can be improved through mutation breeding. Enhanced micronutrient profiles was reported by several workers in faba bean52, in chickpea53, and in lentil.54 The present study revealed possibility of the combining high micronutrient with protein content and the genetic association between yield and protein content, which might be associated insignificantly, or negative correlated.55 The particular dose of gamma rays can induce a micronutrient profile in soybean plant.56 Tomlekova et al.,57 reported that mutation producing high beta-carotene concentrations in pepper fruits had no detrimental effects on the mineral elements and contrary to increase the bioavailability of iron and zinc in the diet. Mutation breeding for fortification of nutritional values in the major food crops has been an attractive area of crop improvement of research. Results revealed high protein content of selected mutant plants might be associated with seed yield support to results reported Kim et al., n.d.,.12 Chen et al.,58 and Laskar et al.,54 were reported the mutants from mutagenized populations indicated an significant increase in the protein content of seeds in comparison to their respective control plants. Non-significant improvement was reported in seed protein content in black gram,43 and reduces content of seed protein in Vigna mungo.59.

Methanol extraction is the most common method used to determine the phytochemicals in various crops.60 In the present study, only capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin were targeted as phytochemical analysis through GC–MS techniques (Fig. 5 and Table 5). The characterization of capsaicinoids through gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy was reported by different workers Iwai et al., 2014;.61 Results revealed mutations in phytochemical constituents and primary sources of variations in metabolic products (Fernie et al., 2008). Younis et al.,62 suggested that colchicine and gamma rays increase the flavonoid concentration and antioxidant activity in the treated population as compared to the control. Arumingtyas and Ahyar,63 reported increased capsaicin content under the treatments of gamma radiation, and enhanced capsaicin content under 30 mM EMS and 15 mM DES treatment.64 These results provide insights of utilization of chemical mutagens to induce phytochemical profile of Capsicum annum L. Alonso-Villegas et al.,65 reported capsaicinoids profile of chilli extract and determined its pungency and inter and intra genetic variations induce changes in fruits pungency,66.67.

Microsatellite polymorphisms through single sequence repeat markers subjected to nine Capsicum genotypes were successfully amplified with the eleven SSR primer pairs. Three typical SSR marker profiles are shown in Fig. 6 (A-C) and Table 6. A total 44 alleles with an average number of 4.00 alleles per locus observed. Dhaliwal et al.,68 was reported 2.78 average allele value per locus, and the maximum four alleles were reported for the primer AVRDC PP32. The number of alleles detected varied from three alleles for Fmop 1–23, Fmop 2–45, CM00342, and Sk00154 to five alleles for Fmop 1–64, AS002132, and CAMS234. The size of the allele ranges from 155 bp (Fmop 1–64) to 265 bp (CM00342) (Table 4). Hossain et al.69 reported genetic diversity of 22 germplasm by using microsatellite markers and a total of 27 alleles with size range of 153 to 315 bp were found after gel electrophoresis. Genetic diversity within 41 genotypes of red chilli pepper recorded through eight microsatellite and total 28 alleles with average size of 3.5 allele per locus, reported by.70 Average number of allele per locus gives complementary information of polymorphism present in genotypes and is sufficient to co-dominant markers (IPGRI, 1999). The difference in allelic length at each locus indicates the presence of broad genetic base within the selected mutants. Haseena et al., (2008) suggested that broad genetic base induce high yield of polymorphic markers within genotypes. Average genetic diversity was recorded to be 0.255 reflecting considerable amount of polymorphism among selected mutant lines and range of genetic distance was recorded to be 0.333 to 0.769. Genetic parameters viz., genetic diversity and genetic distance were reported in several crops such as chilli,[69], [71] Tamarix72 and mung bean.73 The PIC provides an estimate to discriminate molecular markers through the number of alleles present on a locus and relative frequencies of alleles. High polymorphic information content reflected to distantly related genotypes and vice versa. Senior et al.,74 and Semagn et al.,75 were reported marker locus with average number of alleles running at equal frequencies will reflects to high polymorphic information content. Single sequence repeat (SSR) markers are very informative with high polymorphic information content (PIC > 0.50),[76], [77].78 The unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean (UPGMA) dendrogram depicted of nine Capsicum genotypes based on Jaccard (coefficient) genetic distance. The hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) indicates two groups of genotypes and the highest genetic distance was recorded between the mutants A-III and F-III followed by mutant G-III and C-III (Fig. 7). In present study, mutant A-III (0.476) and mutant F-III (0.823) were observed to be genetically most divergent from their respective parent genotypes CN. This revealed that the use mutagen treatments in the present study mutated the genome of cultivar NS 1101 of Capsicum annuum L. Wang et al.,79 suggested the highest contributing clusters to the divergence should be given greater prominence to choose the cluster type for further selection and parents in subsequent hybridization. Dendrogram developed from the similarity and dissimilarity matrix of Jaccard’s coefficient values of mutants and control, showed parental genotype in separate single member cluster different from those of mutant, which confirmed that the significant amount of genetic variability was generated by mutagen treatments in the isolated high yielding mutant lines. All the nine mutant genotypes disseminated in different sub-clusters which might be possible due to higher genetic distance value (>0.6) as observed in 54 % of genotype pairs. Genetic distance value separate the genotypes in different sub-clusters where such value depend on their morphological characters of selected mutants,[80], [69].71

6. Conclusion

Results revealed mutagens are highly effective in inducing genetic variability with varying frequencies. The results decisively demonstrate the usefulness and effective potential of induced mutation breeding in the genetic improvement of Capsicum annuum L. for recovering the superior mutant types having enhanced yield and other variability for improved traits. Enhanced quantitative parameters indicating the mutagens were highly effective in inducing substantial inter-population genetic divergence and possibility of selection of useful traits. Molecular analysis using SSR molecular markers represents that cytomorphological, quantitative, and phytochemical changes are directly related to structural changes in chromosomes as well as DNA molecules. All mutants and control plants showed different peak areas of capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin content indicating the mutagens have the potential to induce phytochemical changes in Capsicum annuum L. at variable concentrations. High-yielding Capsicum mutants showed a considerable level of genetic variations subjected to molecular analysis by SSR markers. Maximum dissimilarity was recorded for F-III and A-III mutants followed by O-III and B-III mutants. Principal component analysis (PCA) and correlation study revealed plant height, 1000-seed weight and number of branches per plants as primary yield components and should be on priority over other traits in direct selection process. Hierarchical clustering grouped into two clusters indicating mutagenic treatments in chilli populations induce heterogeneous mutant lines. Principal component analysis revealed mutant lines induce by lower and medium doses/concentrations were divergent and can be used in improvement program to broadening genetic base of Capsicum annuum L. In M4 generation, high yielding mutant lines were reflecting enhanced nutrient density and improved genetic gain. Considering enhanced nutrient density and improved genetic gain, further mutant characterization and multi-locations trials could be fruitful to release high-yielding and fortified chilli varieties. Mutations generated in economically important traits can be used for inheritance and genetic study of C. annuum L. as well.

Funding

There is no specific funding received by any funding agency in this research.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Nazarul Hasan: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Sana Choudhary: Supervision. Neha Naaz: Methodology, Data curation. Nidhi Sharma: Visualization, Formal analysis. Shahabab Ahmad Farooqui: Resources. Megha Budakoti: Formal analysis. Dinesh Chandra Joshi: Writing – review & editing, Investigation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

Authors are thankful to the head of the cytogenetic and plant breeding lab guidance, and to the chairman of Department of Botany, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India for providing necessary facilities during the study of this research.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgeb.2024.100447.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Jarret R.L., Barboza G.E., da Batista F.R., et al. Capsicum—An Abbreviated Compendium. J Am Soc Hort Sci. 2019;144(1):3–22. doi: 10.21273/JASHS04446-18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubey R.K., Singh V., Upadhyay G., Pandey A.K., Prakash D. Assessment of phytochemical composition and antioxidant potential in some indigenous chilli genotypes from North East India. Food Chem. 2015;188:119–125. doi: 10.1016/J.FOODCHEM.2015.04.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dagnoko S., Yaro-Diarisso N., Sanogo P.N., et al. Overview of pepper (Capsicum spp.) breeding in West Africa. Academicjournals.org. 2013;8(13):1108–1114. doi: 10.5897/AJAR2012.1758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verma R.C., Bhala V.P., Khah M.A. Studies on mutagenic effects of gamma irradiation on chilli (Capsicum annuum L.). Chromosome. Botany. 2017;12(1):13–16. doi: 10.3199/ISCB.12.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimitrios B. Sources of natural phenolic antioxidants. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2006;17(9):505–512. doi: 10.1016/J.TIFS.2006.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruanma, K., Shank, L., & Chairote, G. Phenolic content and antioxidant properties of green chilli paste and its ingredients. Cabdirect.OrgK Ruanma, L Shank, G ChairoteMaejo International Journal of Science and Technology, 2010•cabdirect.Org. 2010. Retrieved October 14, 2023, from https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20113071200.

- 7.Tsuchiya H. Biphasic membrane effects of capsaicin, an active component in Capsicum species. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;75(2–3):295–299. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(01)00200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perucka I., Materska M. Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase and antioxidant activities of lipophilic fraction of fresh pepper fruits Capsicum annum L. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2001;2(3):189–192. doi: 10.1016/S1466-8564(01)00022-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erdoğan C. Genetic characterization and cotyledon color in lentil. Chilean J Agric Res. 2015;75(4):383–389. doi: 10.4067/S0718-58392015000500001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy D.J. Future prospects for oil palm in the 21st century: Biological and related challenges. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol. 2007;109(4):296–306. doi: 10.1002/EJLT.200600229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oladosu Y., Rafii M.Y., Abdullah N., et al. Principle and application of plant mutagenesis in crop improvement: a review. Http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/tbeq. 2015;30(1):1–16. doi: 10.1080/13102818.2015.1087333. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wani, M. R., Kozgar, M. I., Tomlekova, N., et al. Mutation Breeding: A Novel Technique for Genetic Improvement of Pulse Crops Particularly Chickpea (<Emphasis Type=“Italic”>Cicer arietinum</Emphasis> L.). Improvement of Crops in the Era of Climatic Changes, 217–248. 2014. 10.1007/978-1-4614-8824-8_9.

- 13.Fuchs L.K., Jenkins G., Phillips D.W. Anthropogenic impacts on meiosis in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/FPLS.2018.01429/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shahwar D., Khan Z., Ansari M.Y.K. Evaluation of mutagenized lentil populations by caffeine and EMS for exploration of agronomic traits and mutant phenotyping. Ecol Genet Genomics. 2020;14 doi: 10.1016/J.EGG.2019.100049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma N., Shahwar D., Choudhary S. Induction of chromosomal and morphological amelioration in lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.) mutagenized population developed through chemical mutagenesis. Vegetos. 2022;35(2):474–483. doi: 10.1007/S42535-021-00319-6/METRICS. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kundan, M. K., Vinita, T., Yachana, J., & Madhumati, B. Potential and application of molecular markers techniques for plant genome analysis. Researchgate.NetB MadhumatiInt J Pure App Biosci, 2014•researchgate.Net, 2(1), 169–188; 2014. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Afra-Roughani/post/SSR_or_ISSR/attachment/5a842e1a4cde266d588b1e17/AS%3A593915900092422%401518611993889/download/markers.pdf.

- 17.Sharmin A., Hoque M.E., Haque M.M., et al. Molecular Diversity Analysis of Some Chilli (Capsicum spp.) Genotypes Using SSR Markers. Am J Plant Sci. 2018;9(3):368–379. doi: 10.4236/AJPS.2018.93029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmad A., Wang J.D., Pan Y.B., Sharif R., Gao S.J. Development and use of simple sequence repeats (SSRs) markers for sugarcane breeding and genetic studies. Mdpi.Com. 2018 doi: 10.3390/agronomy8110260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasan, N., Choudhary, S., Naaz, N., Sharma, N., & Laskar, R. A. Recent advancements in molecular marker-assisted selection and applications in plant breeding programmes. J Genet Eng Biotechnol 2021, 19(1), 1–26. 10.1186/S43141-021-00231-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Fatma F., Verma S., Kamal A., Srivastava A. Monitoring of morphotoxic, cytotoxic and genotoxic potential of mancozeb using Allium assay. Chemosphere. 2018;195:864–870. doi: 10.1016/J.CHEMOSPHERE.2017.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arisha M.H., Shah S.N.M., Gong Z.-H., Jing H., Li C., Zhang H.-X. Ethyl methane sulfonate induced mutations in M2 generation and physiological variations in M1 generation of peppers (Capsicum annuum L.). Frontiers. Plant Sci. 2015;(June):399. doi: 10.3389/FPLS.2015.00399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hwang, D. Development of an EMS mutant population and isolation of non-pungent mutants in Capsicum annuum; 2014. https://s-space.snu.ac.kr/bitstream/10371/125655/1/000000017960.pdf.

- 23.Paran I., Van Der Knaap E. Genetic and molecular regulation of fruit and plant domestication traits in tomato and pepper. J Exp Bot. 2007;58(14):3841–3852. doi: 10.1093/JXB/ERM257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen O., Borovsky Y., David-Schwartz R., Paran I. Capsicum annuum S (CaS) promotes reproductive transition and is required for flower formation in pepper (Capsicum annuum) New Phytol. 2014;202(3):1014–1023. doi: 10.1111/NPH.12711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jo Y.D., Kim S.H., Hwang J.E., et al. Construction of mutation populations by gamma-ray and carbon beam irradiation in chili pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) Hortic Environ Biotechnol. 2016;57(6):606–614. doi: 10.1007/S13580-016-1132-3/METRICS. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Srivastava, A., & Mangal, M. (2019). Capsicum Breeding: History and Development. 25–55. 10.1007/978-3-319-97217-6_3.

- 27.Arisha M.H., Shah S.N.M., Gong Z.H., Jing H., Li C., Zhang H.X. Ethyl methane sulfonate induced mutations in M2 generation and physiological variations in M1 generation of peppers (Capsicum annuum L.). Frontiers. Plant Sci. 2015;6(June) doi: 10.3389/FPLS.2015.00399/FULL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shu Q.Y., Forster B.P., Nakagawa H. Principles and applications of plant mutation breeding. Plant Mutation Breed Biotechnol. 2012;301–325 doi: 10.1079/9781780640853.0301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nair R., Mehta A.K. Induced mutagenesis in cowpea var. Arka Garima. Indianjournals.com. 2014;48(4):247–257. doi: 10.5958/0976-058X.2014.00658.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan A.S., Ali S., Khan I.A. Morphological and molecular characterization and evaluation of mango germplasm: An overview. Sci Hortic. 2015;194:353–366. doi: 10.1016/J.SCIENTA.2015.08.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manzila I, Priyatno TP., Genetic variations of EMS-induced chili peppers (Capsicum annuum) cv. Gelora generate geminivirus resistant mutant lines. Iopscience.Iop.Org. 2020. Retrieved October 14, 2023, from https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1755-1315/482/1/012031/meta.

- 32.Pharmawati M., Defiani M.R., Wrasiati L.P., Wijaya I.M.A.S. Morphological Changes of Capsicum annuum L. Induced by Ethyl Methanesulfonate (EMS) at M2 Generation. Pdfs.semanticscholar.org. 2018 doi: 10.12944/CARJ.6.1.0101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siddique, M. I., Back, S., Lee, J. H., et al. Development and Characterization of an Ethyl Methane Sulfonate (EMS) Induced Mutant Population in Capsicum annuum L. Plants 2020, Vol. 9, Page 396, 9(3), 396. 10.3390/PLANTS9030396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Tiwari A., Vivian-Smith A., Voorrips R.E., et al. Parthenocarpic potential in Capsicum annuum L. is enhanced by carpelloid structures and controlled by a single recessive gene. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11 doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hasan N., Choudhry S., Laskar R.A. Studies on qualitative and quantitative characters of mutagenised chili populations induced through MMS and EMS. Vegetos. 2020;33(4):793–799. doi: 10.1007/s42535-020-00164-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Devi A.S., Mullainathan L. Effect of gamma rays and ethyl methane sulphonate (EMS) in M3 generation of blackgram (Vigna mungo L. Hepper) Afr J Biotechnol. 2014;11(15):3548–3552. doi: 10.4314/ajb.v11i15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laskar R.A., Khan S., Khursheed S., Raina A. Quantitative Analysis of Induced Phenotypic Diversity in Chickpea Using Physical and Chemical Mutagenesis. Academia. Edu. 2015 doi: 10.3923/ja.2015.102.111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karim K.M.R., Rafii M.Y., Misran A., et al. Genetic Diversity Analysis among Capsicum annuum Mutants Based on Morpho-Physiological and Yield Traits. Mdpi. Com. 2022 doi: 10.3390/agronomy12102436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Falconer D.S., Mackay T.F.C. Longman Group; Essex. UK: 1996. Introduction to quantitative genetics; p. 448. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bello OB, Ige SA, Azeez MA et al. Heritability and genetic advance for grain yield and its component characters in maize (Zea mays L.). Core.Ac.UkOB Bello, SA Ige, MA Azeez, MS Afolabi, SY Abdulmaliq, J MahamoodInternational Journal of Plant Research, 2012•core.Ac.Uk, 2012(5), 138–145. 10.5923/j.plant.20120205.01.

- 41.Sudeepthi K, Srinivas TV, Kumar BR et al. Assessment of genetic variability, character association and path analysis for yield and yield component traits in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Ejplantbreeding.Org, 11(1), 144–148. 2020. 10.37992/2020.1101.026.

- 42.Sreelathakumary I., Rajamony L. Variability, heritability and genetic advance in chilli (Capsicum annuum L.) Jtropag.kau.in. 2004;42(2):35–37. http://jtropag.kau.in/index.php/ojs2/article/view/112 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yasmin K., Arulbalachandran D., Dilipan E. Enhancement of seed protein and amino acid content in M3 and M4 generation of blackgram (Vigna mungo (L.) Hepper) treated by γ-rays. Plant Physiology Reports. 2022;27(3):508–520. doi: 10.1007/S40502-022-00679-4/METRICS. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thilagavathi, C., & Mullainathan, L. Influence of physical and chemical mutagens on quantitative characters of Vigna mungo (L. Hepper). Core.Ac.UkC Thilagavathi, L MullainathanInternational Multidisciplinary Research Journal, 2011•core.Ac.Uk. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/236014628.pdf.

- 45.Avijeet C., Shukla S., Rastogi A., Mishra B.K., Ohri D., Singh S.P. Impact of mutagenesis on cytological behavior in relation to specific alkaloids in Opium Poppy (Papaver somniferum L.) Taylor & Francis. 2011;64(1):14–24. doi: 10.1080/00087114.2011.10589760. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Noman A., Ali Q., Hameed M., Mehmood T., Iftikhar T. Comparison of leaf anatomical characteristics of Hibiscus rosa-sinensis grown in faisalabad region. Pak J Bot. 2014;46(1):199–206. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roychowdhury R., Sultana P., Tah J. Morphological architecture of foliar stomata in M2 Carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus L.) genotypes using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Ejplantbreeding.org. 2011;2(4):583–588. https://ejplantbreeding.org/index.php/EJPB/article/view/596/312 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mallick M., Awasthi O.P., Paul V., Verma M.K., Jha G. Effect of physical and chemical mutagens on leaf sclerophylly and stomatal characteristics of Kinnow mandarin mutants. Indian J Hortic. 2016;73(2):291–293. doi: 10.5958/0974-0112.2016.00063.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pitaloka M.K., Caine R.S., Hepworth C., et al. Induced Genetic Variations in Stomatal Density and Size of Rice Strongly Affects Water Use Efficiency and Responses to Drought Stresses. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/FPLS.2022.801706/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buckley C.R., Caine R.S., Gray J.E. Pores for thought: can genetic manipulation of stomatal density protect future rice yields? Front Plant Sci. 2020;10 doi: 10.3389/FPLS.2019.01783/FULL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sarwar A.G., Karim M.A., Rana S.M., undefined Influence of stomatal characteristics on yield and yield attributes of rice. Ageconsearch.umn.edu. 2013;11(1):47–52. https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/209746/ [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jensen E.S., Peoples M.B., Hauggaard-Nielsen H. Faba Bean in Cropping Systems. Elsevier. 2010;3:203–216. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2009.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bhat M.-U.-D., Khan S., Kozgar M.I. Studies on frequency of chlorophyll and morphological Mutants in Chickpea. J Funct Environ Botany. 2012;2(1):27. doi: 10.5958/J.2231-1742.2.1.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laskar R.A., Laskar A.A., Raina A., Khan S., Younus H. Induced mutation analysis with biochemical and molecular characterization of high yielding lentil mutant lines. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;109:167–179. doi: 10.1016/J.IJBIOMAC.2017.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Farida Traoré F., El-Baouchi A., En-nahli Y., et al. Exploring the Genetic Variability and Potential Correlations Between Nutritional Quality and Agro-Physiological Traits in Kabuli Chickpea Germplasm Collection (Cicer arietinum L.). Frontiers. Plant Sci. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/FPLS.2022.905320/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alikamanoglu S., Yaycili O., Sen A. Effect of gamma radiation on growth factors, biochemical parameters, and accumulation of trace elements in soybean plants (Glycine max L. Merrill) Biol Trace Elem Res. 2011;141(1–3):283–293. doi: 10.1007/S12011-010-8709-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tomlekova N.B., White P.J., Thompson J.A., Penchev E.A., Nielen S. Mutation increasing β-carotene concentrations does not adversely affect concentrations of essential mineral elements in pepper fruit. PLoS One. 2017;12(2) doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0172180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen Y., Wang M., Ouwerkerk P.B.F. Molecular and environmental factors determining grain quality in rice. Food Energy Secur. 2012;1(2):111–132. doi: 10.1002/FES3.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goyal S., Wani M.R., Laskar R.A., Raina A., Amin R., Khan S. Induction of morphological mutations and mutant phenotyping in black gram [Vigna mungo (L.) Hepper] using gamma rays and EMS. Vegetos. 2019;32(4):464–472. doi: 10.1007/S42535-019-00057-W. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kozukue N., Han J.S., Kozukue E., et al. Analysis of eight capsaicinoids in peppers and pepper-containing foods by high-performance liquid chromatography and liquid chromatography - Mass spectrometry. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53(23):9172–9181. doi: 10.1021/JF050469J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saha S., Walia S., Kundu A., Kaur C., Singh J., Sisodia R. Capsaicinoids, Tocopherol, and Sterols Content in Chili (Capsicum sp.) by Gas Chromatographic-Mass Spectrometric Determination. Taylor & Francis. 2015;18(7):1535–1545. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2013.833222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Younis A.S.M., Nassar S.M.A., Al-Naggar A.M.M., Bakry B.A. Phenotypic assessment of genetic diversity among twenty groundnut genotypes under well-watered and water-stressed conditions using multivariate analysis. Asian J Plant Sci. 2020;19(4):474–486. doi: 10.3923/ajps.2020.474.486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arumingtyas E.L., Ahyar A.N. Genetic diversity of chili pepper mutant (Capsicum frutescens L.) resulted from gamma-ray radiation. IOP Conf Ser: Earth Environ Sci. 2022;1097(1) doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/1097/1/012059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mullainathan L., Devi A.S. Genotoxicity Effect of Ethyl Methanesulfonate on Root Tip Cells of Chilli (Capsicum annuum L.) World J Agric Sci. 2011;7(4):368–374. [Google Scholar]