Abstract

Background: Alpha-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) has been widely investigated in malignancies, primarily concerning its expression in cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) inside the tumor stroma. Microscopic examination indicates that αSMA expression is not confined to the tumor stromal compartment but is also present in a subset of tumor cells, and this expression correlates with an enhanced invasive phenotype of malignant cells from lung, liver, or ovarian malignancies. Information on actin expression in breast cancer (BC) cells is scarce, and its influence on clinicopathological characteristics remains ambiguous due to conflicting findings in the literature.

Objective: To examine the αSMA tumor score in breast cancer cells utilizing digital image analysis (DIA) methodologies and to critically analyze the varying effects of αSMA tumor score values on clinicopathologic parameters, particularly focusing on tumor cell invasiveness, recurrence, and survival.

Materials and methods: Double immunostaining for CD34 and αSMA was conducted on 53 breast cancer cases that were thoroughly characterized in relation to clinicopathologic data. Double immunostaining for CD34 and αSMA demonstrated different distribution patterns of both markers in normal and breast cancer tissues. DIA data about αSMA tumor cell density, intensity, tumor score, and histological score were correlated with clinicopathological factors.

Results: We delineated three unique breast cancer subgroups based on αSMA tumor scores: a 9.43% low-expressing subgroup (αSMA_TSlow, score 4), a 35.07% medium-expressing subgroup (αSMA_TSmed, scores 5 and 6), and a 55.5% high-expressing subgroup (αSMA_TShigh, scores 7 and 8). Stromal immature vessels and tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) exhibited a strong correlation with αSMA_TSlow, whereas recurrence, perineural, and lymphovascular invasion strongly influenced the αSMA_TSmed and αSMA_TShigh subgroups. The αSMA_TSmed subgroup demonstrated the most heterogeneity with the influence of αSMA-expressing breast cancer cells on tumor size, nodal status, perineural and lymphovascular invasion, menopausal status, recurrence, and survival. Most of the cases from the αSMA_TSlow subgroup had Luminal B and Luminal B-HER2 phenotypes, while triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) represented one-third of all cases in the αSMA_TShigh subgroup.

Conclusion: αSMA-expressing breast cancer cells variably affect malignant growth, invasion, and recurrence, highly contingent upon their density and expression intensity. The current investigation identified an αSMA_TSmed BC subgroup that appears to promote invasiveness, recurrence, and survival in breast cancer. Our data indicate that αSMA BC-expressing cells play a dual role in BC progression, contingent upon their percentage and expression intensity; however, further research is required to elucidate the factors and mechanisms responsible for their accumulation and/or transdifferentiation in malignant breast tissue.

Keywords: alpha smooth muscle actin, breast cancer, invasion, molecular subtypes, recurrence, survival

Introduction

Breast cancer represents the most prevalent form of malignancy among women globally and exhibits a curable rate of approximately 70-80% in patients diagnosed with early-stage, non-metastatic disease. The presence of advanced breast cancer accompanied by distant organ metastases is regarded as incurable with the therapies that are presently accessible. At the molecular level, breast cancer presents as a heterogeneous disease characterized by various molecular features, including the activation of the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2, encoded by ERBB2), the activation of hormone receptors (such as the estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor), and/or mutations in the BRCA genes [1].

Breast cancer cells have a high ability to migrate, invade the local surrounding tissues and lymph nodes, and initiate distant metastases. Cell movement is based on the actin cytoskeleton rearrangement induced by several local and general factors [2, 3].

Actin is a fundamental structural protein constituting the cytoskeleton of cells, and it is involved in processes such as division, migration, and vesicle trafficking. It consists of six distinct isoforms specific to various cell types: ACTA1, ACTA2, ACTB, ACTC1, ACTG1, and ACTG2. Altered expression of actin isoforms has been shown in numerous malignancies, prompting us to propose that it could function as an early diagnostic marker for cancer [4]. Alpha-smooth muscle actin (αSMA, ACTA2) plays a role in the generation of mechanical tension by cells and the preservation of cellular morphology. αSMA is crucial in the migration and invasion of malignant cells [5]. Elevated αSMA expression facilitates the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) associated with tumor progression and metastasis in lung and pancreatic malignancies [6, 7].

In normal human breast tissue, αSMA expression is restricted to the myoepithelial cells surrounding secretory components and ductal structures [8]. Myoepithelial cells serve as a dynamic barrier to the dissemination of epithelial cells [8, 9].

αSMA expression has been intensely studied in breast cancer stromal-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) [10, 11], and it was proven that αSMA-positive CAFs increase breast cancer tumor stroma and influence tumor progression, metastatic potential, prognosis, and patients' overall survival [12-14]. Recent data also stated that αSMA-positive circulating CAFs have the ability to travel through the bloodstream, significantly impacting breast cancer metastatic potential and influencing tumor prognosis and overall survival [15].

By contrast to the extensive research on αSMA in the breast cancer stromal compartment, its presence and role in breast cancer cells are far less studied. Most related data, derived from experimental research, describe the interrelation between αSMA-expressing breast cancer cells and other factors involved in BC initiation, progression, invasion, and metastasis. Kim et al. demonstrated that TP53 enhances the expression of αSMA in breast cancer cells that exhibit resistance to tamoxifen [16]. Jeon et al. demonstrated that the induction of ACTA2 through the dimerization of EGFR and HER2 is regulated by a JAK2/STAT1 signaling pathway and that abnormal expression of ACTA2 increases the invasiveness and metastasis of breast cancer cells [17]. In a study published by Yadav et al., the authors reported an atypical Luminal A BC case overexpressing αSMA in tumor cells, showing a poor prognosis compared to other similar cases tested for the same parameters [18]. The capacity for self-renewal and the ability to form spheres from breast cancer stem-like cells originating from human primary invasive ductal carcinoma were associated with high αSMA expression in BC cells [19]. lncRNA ACTA2-AS1 serves as a prognostic indicator of malignancy and adverse outcomes in triple-negative breast cancer, influencing tumor progression through the modulation of miR-532-5p [20].

Despite the indirect evidence of αSMA’s role in BC cell behavior, no well-defined data related to its impact on clinicopathologic parameters have been found in the literature. During one of our previous studies related to the immunohistochemical expression of αSMA in the BC stromal compartment, we observed that malignant areas also contain αSMA-positive malignant cells showing high variability in their density and intensity of expression. We wanted to determine whether this heterogeneous expression may have any impact on clinicopathologic parameters. Based on previously described evidence, we initiated the present research to assess αSMA BC cell heterogeneity using immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Digital Image Analysis (DIA) techniques. αSMA tumor score values were then critically analyzed and correlated with clinicopathologic parameters (age, IMC, TNM staging, perineural and lymphovascular invasion, stromal components, molecular subtypes, survival, recurrence, and menopausal status), particularly focusing on tumor cell invasiveness, recurrence, and survival.

Materials and methods

Criteria for patient selection and corresponding ethical implications

This study is part of a larger retrospective analysis involving 150 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) breast cancer specimens obtained from women diagnosed with ductal invasive carcinoma via histopathological assessment, identified between 2015 and 2022, and aged 32 to 85 years. Two separate pathologists performed a follow-up study of the FFPE samples to confirm the diagnosis and identify cases appropriate for IHC. A molecular profile was created for each case using immunohistochemical markers. The markers included the estrogen receptor (ER), the progesterone receptor (PR), the Proliferation Index (Ki67), and an evaluation of the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). This was crucial for clarifying the different molecular subtypes of breast cancer. To achieve the goals of this inquiry, we selected 53 individuals who displayed a thorough clinical, histological, and therapeutic profile considered beneficial for our analysis. This study examines age, menopausal status, breast cancer molecular subtype, tumor grade (G), Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI), lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, recurrence, and TNM staging, all of which are relevant clinicopathologic and therapeutic factors. We identified αSMA-positive (αSMA+) breast cancer cells inside malignant tumor regions and classified stromal tumor blood vessels as either immature (CD34+/αSMA-) or mature (CD34+/αSMA+) to ascertain connections with the density and distribution of αSMA+ tumor cells. At the time of diagnosis, imaging modalities verified the absence of any verifiable history of metastases in the patients. Informed consent was obtained from each patient using a standardized form that had been evaluated and approved by the Research Ethics Council of the Victor Babeș University of Medicine and Pharmacy in Timișoara (No. 49/28.09.2018).

Initial processing, histological assessment, and criteria for the selection of FFPE specimens for IHC evaluation

Initially, tumor samples were obtained for diagnostic purposes before the initiation of treatment, which included a mastectomy and needle core biopsy. A sample of the tumor, including the surrounding tissue that represented the whole, was chosen for examination. After acquiring breast cancer tissue samples, the specimens were stored in buffered formalin for 24 to 48 hours, thereafter embedded in paraffin using the standard process. The FFPE block was precisely sectioned to a thickness of three micrometers, and the resulting sections were carefully mounted onto glass slides. A slide was procured from each case for histopathologic investigation and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Two separate pathologists evaluated the hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides pertinent to the case to validate the initial histopathological diagnosis and appraise the tissue quality. This was essential for ensuring the appropriate selection of patients for IHC. Vimentin (clone V9) immunostaining was utilized to evaluate the overall quality of the tissue. Cases demonstrating positive vimentin staining in the tumor stroma were considered suitable for selection and subsequent immunohistochemical analysis.

Immunohistochemistry

IHC was conducted on three-micrometer-thick sections with an autostainer manufactured by Leica Biosystems, based in Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom. The Novocastra Bond Epitope Retrieval Solutions 1 and 2 were utilized in the unmasking method (Leica Biosystems, Newcastle Ltd, Newcastle upon Tyne NE12 8EW, UK). A 3% hydrogen peroxide solution was used to inhibit endogenous peroxidase activity for five minutes. A twofold immunostaining approach was applied to multiple tissue specimens to examine the presence and location of the αSMA+ response in breast cancer cells. A comprehensive analysis of the unique features of mature and immature tumor blood vessels originating from the breast cancer stromal component was performed and previously evaluated. CD34 mouse anti-human monoclonal antibodies (clone QBEnd 10, Leica Biosystems, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) were applied for 30 minutes at ambient temperature to target the endothelium of tumor vasculature. Additionally, we used αSMA mouse anti-human monoclonal antibodies (clone 1A4, Leica Biosystems, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK), with a 30-minute incubation at room temperature. The implementation of the IHC approach required the use of visualization systems, namely the Bond Polymer Refine Detection System DAB and the Bond Polymer Refine Red Detection System. For CD34, the vessel endothelium was considered an internal positive control. For SMA, perivascular cells surrounding stromal capillaries were considered positive controls. Negative control was obtained by omitting the incubation with the primary antibody. For additional DIA, we focused on the cytoplasmic expression of αSMA in tumor cells and the concurrent expression of CD34/αSMA in immature versus mature stromal blood vessels proximal to tumor regions.

Image acquisition and DIA

The IHC samples were scanned using a Grundium OCUS 20 Microscope (Grundium, Tampere, Finland) and subsequently stored in the Case Center Slide Library as SVS files (3DHistech, Budapest, Hungary). A project was initiated by importing all slides stained with CD34/SMA and CD34 alone into QuPath version 0.4.3, an open-source platform intended for the bioimage analysis of microscopic slides. The slides were evaluated using integrated software and its supplemental capabilities, including Fiji and Vascular Analysis, to enable an accurate evaluation of tumor stromal blood vessels. In summary, we defined 3-5 regions of interest (ROIs) (Figure 1A) inside the malignant areas using the brush tool, which facilitated the most accurate delineation of tumor regions where αSMA tumor cells were discovered. The DIA analysis began with a pre-processing phase that included the determination of stain vectors (Figure 1B). The next stage of the analysis entailed identifying cells by selecting the positive cell detection option and configuring cell and intensity parameters. The detection image was set up to measure the sum of optical density with a designated pixel size of 0.5 μm and a cell expansion of 1.988 μm, excluding the nucleus. The intensity threshold parameters comprised a score compartment and three evaluative levels: weak (+1, shown in yellow), moderate (+2, marked in orange), and high (+3, denoted in red). All cells highlighted in blue were classified as negative (Figure 1C, D). During automated scoring, the QuPath program provided a cell count, as well as the percentage of both αSMA-positive and αSMA-negative breast cancer cells. It offered distinct density and intensity scores, along with a consolidated Stromal Score (SS), similar to the Allred score, which amalgamates the intensity and density of positively detected cells. Additionally, the conclusive assessment performed using QuPath analysis included a histological score (H-score). In this study, we utilized the intensity of positive αSMA breast cancer cells, their density, and the Allred Score to attain a more accurate evaluation and association with clinicopathologic criteria.

Analytical assessment of statistical data

The statistical analysis was performed using JAMOVI software (The jamovi Project, Sydney, Australia) on macOS systems. The findings obtained from DIA were associated with genetic subtypes of breast cancer, menopausal state, immature and mature stromal blood vessels, tertiary lymphoid structures previously evaluated by us, recurrence, lymphovascular and perineural invasion, and age. A statistical correlation was assessed and considered significant for a p-value of 0.05 or lower.

Results

Comprehensive analysis of αSMA expression in normal and malignant breast tissues

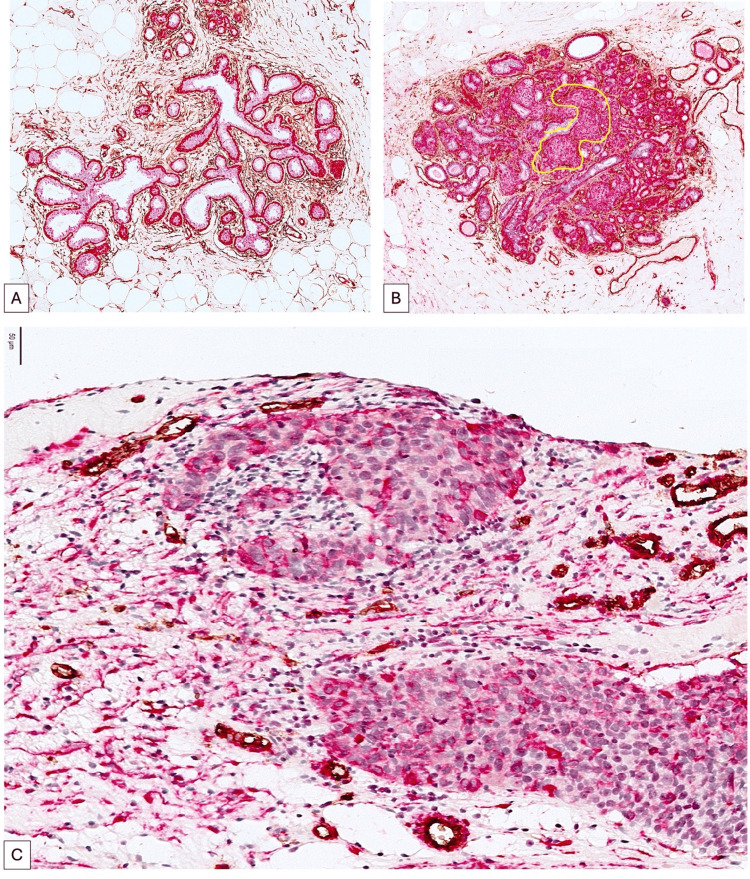

The dual immunostaining for CD34 and αSMA demonstrated a distinct expression of both markers in normal and malignant breast cancer tissues. The normal terminal ductal lobular unit (TDLU) expresses αSMA in the continuous layer of myoepithelial cells that delineate both secretory and ductal components (Figure 1A). The intralobular and interlobular stroma exhibit elevated CD34 expression, primarily linked to normal stromal fibroblasts. The accumulation of αSMA+ cells within the TDLU, as illustrated in Figure 1B, often indicates the onset of benign breast tissue transformation; however, the discontinuity of the αSMA+ myoepithelial layer serves as a microscopic indicator of breast cancer invasion. Upon the onset of invasive breast cancer, αSMA typically diminishes in tumor cells while concurrently elevating in the stromal compartment, specifically in a subtype of cancer-associated fibroblasts (Figure 1C).

Within the malignant regions of BC, we noted a varied fraction of αSMA+ cells characterized by heterogeneous distribution and expression intensity. We anticipated that the heterogeneity of expression and localization of these αSMA+ tumor cells may influence other tumor characteristics with potential prognostic significance (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. αSMA expression in the normal TDLU (A), early stages of malignant transformation (B, ×100 magnification), and in the tumor cells from invasive carcinoma (C). Note that in normal TDLU, actin expression is restricted to the continuous myoepithelial cell layer surrounding the secretory and ductal components (A, SMA, red, ×100 magnification). Variability in the intensity and density of αSMA-positive tumor cells can be observed in Figure C (×400 magnification).

αSMA: alpha-smooth muscle actin, TDLU: terminal duct lobular unit, SMA: smooth muscle actin.

We evaluated intratumoral αSMA expression utilizing the QuPath platform, a digital image analysis software application that enables precise data acquisition on the percentage of αSMA positive cells, as well as the integration of expression intensity and density into a final αSMA tumor score (αSMA_TS).

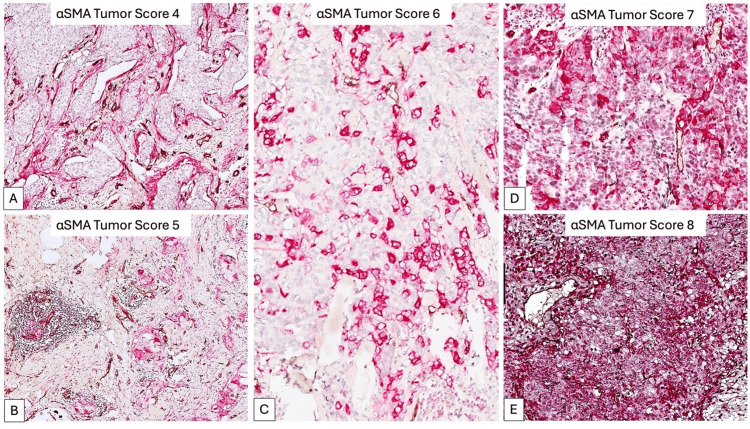

Utilizing the α SMA_TS value, we delineated three unique breast cancer subgroups: low expressing subgroup (αSMA_TSlow, 9.43% of all cases with a score of 4, Figure 2A), medium expressing subgroup (αSMA_TSmed, 35.07% of cases with scores of 5 and 6, Figure 2B,C), and high expressing subgroup (αSMA_TShigh, 55.5% of cases with scores of 7 and 8, Figure 2D,E) (Table 1).

Table 1. The percentage of cases distribution according to the three subgroups. Note that more than half of the cases had a high expression of SMA.

αSMA_TSlow: low αSMA expression subgroup, scored as 4; αSMA_TSmed: medium αSMA expression subgroup scored as 5 and 6; αSMA_TShigh: high αSMA expression subgroup.

| Subgroup | αSMA_TSlow | αSMA_TSmed | αSMA_TShigh |

| Tumor score | 4 | 5-6 | 7-8 |

| % Cases | 9.43% | 35.07% | 55.5% |

Figure 2. αSMA tumor score (SMA_TS) according to the density and intensity of αSMA expression in tumor cells. Digital Image Analysis defined five scores of αSMA expression, ranging from the lowest score (A), to medium scores (B, C), and high scores (D, E). Based on these scores, we stratified our cases for further analysis.

αSMA: alpha-smooth muscle actin.

The impact of αSMA_TS on clinicopathologic parameters

For each subgroup, we analyzed the variability of αSMA_TS interrelation with stromal components (mature/immature blood vessels and tertiary lymphoid structures-TLS) but also with the following clinicopathologic parameters: age, IMC, weight, menopausal status, survival, TNM staging parameters, presence of lymphovascular and perineural invasion, BC molecular subtypes, tumor grade, Nottingham score, HER2 status, and recurrence. None of the cases had distant metastases at the time of initial diagnosis.

For the αSMA_TSlow subgroup, all cases were of Luminal B, HER2, and Luminal B-HER2 subtypes. We did not detect any Luminal A or TNBC cases. No perineural (PNI) or lymphovascular (LVI) invasion was detected in any case, nor were nearby nodal (N) metastases. TLS presence and a high number of immature stromal blood vessels (IBV, CD34+/SMA-) were significantly correlated with a low percentage of αSMA-positive tumor cells (Table 2).

Table 2. Correlation matrix in between percentage of SMA expressing cells and H-score with lymphoid (TLS) and vascular (IBV) components of the BC stromal compartments.

*Significant correlation.

**Strongly significant correlation.

%SMA+T.Cells: percentage of positive SMA tumor cells in the selected area; H-Score: histological score; TLS: tertiary lymphoid structures; IBV: immature blood vessels with no SMA coverage.

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, one-tailed.

| Components | Variables | %SMA+T.Cells | H-Score |

| TLS | Pearson's r | 0.963** | 0.466 |

| p-value | 0.004 | 0.214 | |

| 95% CI upper | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| 95% CI lower | 0.679 | -0.577 | |

| Spearman's rho | 0.866* | 0.866* | |

| p-value | 0.029 | 0.029 | |

| Kendall's Tau B | 0.775* | 0.775* | |

| p-value | 0.042 | 0.042 | |

| IBV | Pearson's r | 0.865 | -0.056 |

| p-value | 0.029 | 0.536 | |

| 95% CI upper | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| 95% CI lower | 0.147 | -0.839 | |

| Spearman's rho | 0.975 | 0.410 | |

| p-value | 0.002 | 0.246 | |

| Kendall's Tau B | 0.949 | 0.316 | |

| p-value | 0.011 | 0.224 |

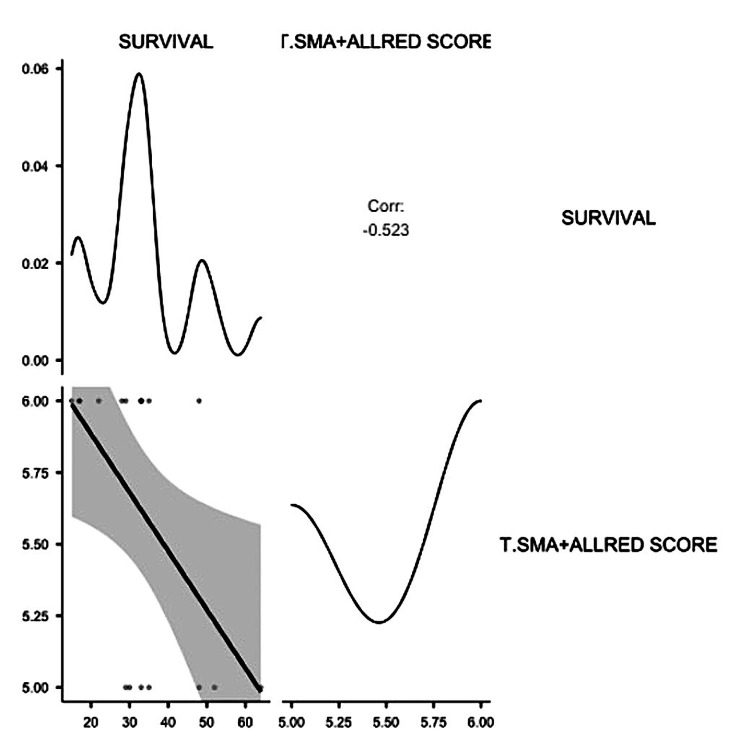

No other significant correlations were detected for the αSMA_TSlow subgroup. The αSMA_TSmed subgroup included 22.22% Luminal A cases, 38.88% Luminal B cases, 11.11% Luminal B-HER2 cases, and 27.77% TNBC cases. No HER2-type cases were reported for this subgroup. Tumor size (T) was significantly correlated with the intensity of αSMA expression in tumor cells (p = 0.005) but not with αSMA_TS. Nodal metastases highly increased in the αSMA_TSmed subgroup with a score of 6. For this group, a significant correlation between N, the percentage of αSMA-positive cells (p = 0.048), and αSMA_TS (p = 0.05) was observed. However, the most relevant findings for this subgroup were the significant impact of αSMA-positive tumor cell presence on LVI, PNI, recurrence (R), and survival. Most of the cases with LVI, PNI, and recurrence had a score of 6. A total of 85.74% of cases with a score of 5 had a survival rate ranging between 30 to 64 months, compared with 36.36% of cases scored as 6, where the survival rate ranged between 30 to a maximum of 48 months. Thus, an inverse correlation between survival and αSMA-positive tumor cells was reported in the present study (Table 3 and Figure 3).

Table 3. Correlation matrix between tumor score and survival. An inverse significant correlation has been observed.

α SMA_TS: tumor score for SMA-positive tumor cells.

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, one-tailed.

| Variables | Survival | |

| αSMA_TS | Pearson's r | -0.523* |

| p-value | 0.013 | |

| 95% CI upper | -0.155 | |

| 95% CI lower | -1.000 | |

| Spearman's rho | -0.498* | |

| p-value | 0.018 | |

| Kendall's Tau B | -0.429* | |

| p-value | 0.020 |

Figure 3. Correlation plot of SMA tumor score and survival.

SMA: smooth muscle actin.

Strong positive significant correlations have been registered for the αSMA_TSmed subgroup related to LVI, PNI, and R (Table 4).

Table 4. Correlation matrix for αSMA_TS medium-expressing subgroup. Strong and powerful correlations have been found between LVI, PNI, and R with parameters of SMA expression assessed by the Digital Image Analysis software QuPath.

LVI: lymphovascular invasion; PNI: perineurial invasion; R: recurrence; %SMA+T.Cells: percentage of SMA positive tumor cells reported to the total number of cells; H-Score: histological score; SMA.D: density of SMA positive tumor cells; SMA.I: intensity of SMA positive tumor cells; αSMA_TS: tumor score for SMA positive tumor cells.

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, one-tailed.

| LVI | PNI | R | ||

| %SMA+T.Cells | Pearson's r | 0.623** | 0.685*** | 0.355 |

| p-value | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.074 | |

| 95% CI upper | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| 95% CI lower | 0.295 | 0.391 | -0.053 | |

| Spearman's rho | 0.696*** | 0.772*** | 0.417* | |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.043 | |

| Kendall's Tau B | 0.584** | 0.648*** | 0.349* | |

| p-value | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.043 | |

| H-Score | Pearson's r | 0.610** | 0.542* | 0.408* |

| p-value | 0.004 | 0.010 | 0.046 | |

| 95% CI upper | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| 95% CI lower | 0.277 | 0.180 | 0.009 | |

| Spearman's rho | 0.482* | 0.500* | 0.388 | |

| p-value | 0.021 | 0.017 | 0.056 | |

| Kendall's Tau B | 0.404* | 0.419* | 0.325 | |

| p-value | 0.023 | 0.020 | 0.055 | |

| SMA.D. | Pearson's r | 0.659** | 0.732*** | 0.463* |

| p-value | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.027 | |

| 95% CI upper | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| 95% CI lower | 0.350 | 0.468 | 0.076 | |

| Spearman's rho | 0.675** | 0.767*** | 0.485* | |

| p-value | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.021 | |

| Kendall's Tau B | 0.660** | 0.750*** | 0.474* | |

| p-value | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.023 | |

| SMA.I | Pearson's r | 0.000 | -0.378 | -0.239 |

| p-value | 0.500 | 0.939 | 0.830 | |

| 95% CI upper | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| 95% CI lower | -0.401 | -0.676 | -0.584 | |

| Spearman's rho | 0.000 | -0.378 | -0.239 | |

| p-value | 0.500 | 0.939 | 0.830 | |

| Kendall's Tau B | 0.000 | -0.378 | -0.239 | |

| p-value | 0.500 | 0.940 | 0.838 | |

| αSMA_TS | Pearson's r | 0.798*** | 0.564** | 0.357 |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.007 | 0.073 | |

| 95% CI upper | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| 95% CI lower | 0.583 | 0.211 | -0.051 | |

| Spearman's rho | 0.798*** | 0.564** | 0.357 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.007 | 0.073 | |

| Kendall's Tau B | 0.798*** | 0.564* | 0.357 | |

| p-value | 0.010 | 0.071 |

The αSMA_TShigh subgroup includes more than half of our total number of αSMA-positive BC cases. For all cases in this subgroup, we observed the highest density of αSMA-positive tumor cells, noted with a score of 5. Tumor cell αSMA expression intensity was variable among cases with αSMA_TS scores of 7 and 8. A total of 16.66% of cases had a Luminal A molecular phenotype, 33.33% Luminal B, 10% Luminal B-HER2, 6.66% HER2, and 33.34% TNBC subtype.

Our data showed that cases in the αSMA_TShigh subgroup with strong actin expression in tumor cells significantly overlapped with menopausal status (Table 5).

Table 5. Correlation matrix between menopausal status and tumor score for high SMA expressing subgroup.

αSMA_TS: tumor score for SMA-expressing cells.

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, one-tailed.

| Menopausal status | ||

| αSMA_TS | Pearson's r | 0.342* |

| p-value | 0.032 | |

| 95% CI upper | 1.000 | |

| 95% CI lower | 0.040 | |

| Spearman's rho | 0.342* | |

| p-value | 0.032 | |

| Kendall's Tau B | 0.342* | |

| p-value | 0.033 |

For the αSMA_TShigh subgroup scored 7, several inverse correlations were reported related to tumor size (T2-T4), proliferative status (Ki67), LVI, PNI, and R (Table 6).

Table 6. Correlation matrix of tumor parameters for high expressing subgroup.

%SMA+T.Cells: the percentage of SMA-positive tumor cells; H-Score: histological score; T: tumor size; Ki67: proliferation index; LVI: lymphovascular invasion; PNI: perineural invasion; R: recurrence.

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, one-tailed.

| T | Ki67 | LVI | PNI | R | ||

| %SMA+T.Cells | Pearson's r | -0.717** | -0.485* | -0.509* | -0.826*** | -0.758*** |

| p-value | 0.002 | 0.039 | 0.032 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| 95% CI upper | -0.384 | -0.034 | -0.065 | -0.591 | -0.459 | |

| 95% CI lower | -1.000 | -1.000 | -1.000 | -1.000 | -1.000 | |

| Spearman's rho | -0.433 | -0.396 | -0.431 | -0.608* | -0.669** | |

| p-value | 0.061 | 0.080 | 0.062 | 0.011 | 0.004 | |

| Kendall's Tau B | -0.325 | -0.287 | -0.365 | -0.514* | -0.566** | |

| p-value | 0.069 | 0.077 | 0.060 | 0.014 | 0.008 | |

| H-Score | Pearson's r | -0.578* | -0.471* | -0.327 | -0.795*** | -0.623** |

| p-value | 0.015 | 0.045 | 0.127 | <0.001 | 0.009 | |

| 95% CI upper | -0.162 | -0.016 | 0.156 | -0.528 | -0.230 | |

| 95% CI lower | -1.000 | -1.000 | -1.000 | -1.000 | -1.000 | |

| Spearman's rho | -0.362 | -0.517* | -0.196 | -0.608* | -0.453 | |

| p-value | 0.102 | 0.029 | 0.251 | 0.011 | 0.052 | |

| Kendall's Tau B | -0.273 | -0.354* | -0.166 | -0.514* | -0.383 | |

| p-value | 0.106 | 0.040 | 0.240 | 0.014 | 0.051 |

A direct, positive, significant correlation was observed between the molecular subtype (TNBC) and the αSMA_TShigh subgroup, scored as 7 for partial %SMA+ T.Cells and showing a strong H-score (Table 7).

Table 7. Correlation matrix between the TNBC molecular subtype with SMA-expressing cells.

TNBC: triple-negative breast cancer; H-Score: histological score; %SMA+T.Cells: percentage of positive cells.

Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, one-tailed.

| TNBC molecular type | ||

| %SMA+T.Cells | Pearson's r | 0.386 |

| p-value | 0.086 | |

| 95% CI upper | 1.000 | |

| 95% CI lower | -0.088 | |

| Spearman's rho | 0.506* | |

| p-value | 0.032 | |

| Kendall's Tau B | 0.399* | |

| p-value | 0.031 | |

| H-Score | Pearson's r | 0.458* |

| p-value | 0.050 | |

| 95% CI upper | 1.000 | |

| 95% CI lower | -0.001 | |

| Spearman's rho | 0.506* | |

| p-value | 0.032 | |

| Kendall's Tau B | 0.375* | |

| p-value | 0.040 |

We summarized in Table 8 all significant correlations found for SMA expression in tumor cells, dependent on tumor score and clinicopathologic parameters.

Table 8. Conclusive table related to significance for each subgroup and clinicopathologic parameters.

NS: not significant; TNBC: triple-negative breast cancer.

| Parameters | Subgroup | ||

| αSMA_TSlow | αSMA_TSmed | αSMA_TShigh | |

| Tumor score | 4 | 5-6 | 7-8 |

| Menopausal status | NS | NS | p = 0.032 |

| Molecular subtype | NS | NS | p = 0.050 |

| Tumor size (T) | NS | p = 0.005 (TNBC-related) | p = -0.002 |

| Nodal status (N) | NS | p = 0.048 | NS |

| Proliferation rate (Ki67) | NS | NS | p= -0.039 |

| Tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) | NS | NS | NS |

| Immature blood vessels (IBV) | p = 0.029 | NS | NS |

| Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) | NS | p < 0.001 | p = -0.032 |

| Perineural invasion (PNI) | NS | p = 0.007 | p = -0.011 |

| Recurrence | NS | p = 0.043 (partial) | p = -0.009 |

| Survival | NS | p = -0.013 | NS |

Discussion

αSMA (ACTA2) overexpression in breast cancer is extensively studied in relation to CAFs from tumor stroma [10, 11]. Data about αSMA expression in BC malignant cells are very limited, controversial, and mostly related to epithelial-mesenchymal transition [21]. Additionally, ACTA2 expression is especially associated with the BC basal phenotype [22]. This is also confirmed in the present study, where we reported a significant correlation between the TNBC phenotype, the percentage of αSMA-positive cells, and the H-score in the αSMA_TShigh subgroup but not in the αSMA_TSlow or αSMA_TSmed subgroups. Peng et al. [20] experimentally demonstrated that ACTA2-AS1 serves as a tumor suppressor and dramatically inhibits tumor cell proliferation, invasion ability, and progression of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. We validated these experimental results here on human BC tissue specimens for the αSMA_TShigh subgroup. A high αSMA expression in tumor cells from our cases inhibited proliferation, LVI, PNI, and recurrence, with this finding being supported by inverse correlations obtained for all these parameters in the αSMA_TShigh subgroup. This is the first report on αSMA impact on clinicopathological parameters in human BC. Most papers published previously used BC cell lines, where the interrelation with clinicopathologic parameters was limited. Scattered data mentioned mutual interactions between αSMA tumor expression and other factors such as TP53 mutation or estrogen receptor (ER)/progesterone receptor (PR) status. Kim et al. demonstrated that TP53 activation induced αSMA tumor expression in tamoxifen-resistant cancer cells [16]. The same authors observed that cases with αSMA expression in ER-positive cancer cells had a poor prognosis [16]. This aligns with our findings for the αSMA_TSmed subgroup. In this group, more than 60% of cases showed ER positivity. This subgroup was the only one in this study where αSMA overexpression had a significant negative impact on survival, most likely due to ER presence in cancer cells.

Recently, Yadav et al. [18] identified several subgroups of TNBC cancer and a poor-prognosis Luminal A subgroup based on αSMA overexpression using single-cell multiplex imaging. We also found that in the αSMA_TSlow subgroup, scored as 4, there were no TNBC or Luminal A cases, while in the αSMA_TSmed and αSMA_TShigh subgroups, Luminal and TNBC subgroups predominated.

Apparently controversial but interesting data were found here regarding the correlation between αSMA tumor expression and invasion (lymphovascular-LVI, perineural-PNI) and recurrence. While in the αSMA_TSmed subgroup, actin-expressing tumor cells seem to favor invasion (both LVI and PNI) and recurrence, in the αSMA_TShigh subgroup, a high content of αSMA in tumor areas induced an inverse correlation with invasion and recurrence. This divergent data seems to be based on different pathogenic mechanisms involving αSMA-positive cancer cells. For the αSMA_TSmed subgroup, actin expression in tumor cells was strongly positively correlated with LVI, PNI, and R. This may be explained by the high hormone receptor positivity in this subgroup, which in turn may favor invasion through the activation of BC circulating tumor cells (CTCs), as previously described in several papers [23-25]. The actin cytoskeleton is highly dynamic, and an increase in αSMA expression may induce high BC cell rigidity, as reported in previous studies [26], which in turn could be negatively correlated with cell motility and subsequently with LVI and PNI. Last but not least, αSMA expression in the tumor microenvironment modulates malignant cell invasion. In one of our previous studies, we reported that αSMA expression in CAFs from tumor stroma strongly influences PNI and LVI differently, depending on BC molecular subtypes. Tumor stromal microenvironment stiffness strongly influences BC cell invasion ability [27-30].

Most of the cases (statistically significant) from the αSMA_TShigh subgroup are women in menopausal status, where the hormonal microenvironment is completely altered. An increase in tumor cell αSMA expression in the αSMA_TShigh subgroup may be induced by the lack of hormonal stimulation during menopause, which in turn reduces tumor cell invasion and subsequently recurrence. No data are currently available in the literature regarding this subject, so our hypothesis may be strengthened by further studies focused on this issue. We will continue to investigate this aspect in a larger number of cases and for each molecular subtype.

No data on the impact of menopausal status on αSMA expression in tumor cells have been previously reported. We found that most cases scored as 7 and 8 for αSMA expression in tumor cells were diagnosed in menopausal patients. This may be explained by the altered hormonal microenvironment during menopause.

Conclusions

αSMA expression in tumor cells is highly heterogeneous and dependent on several factors. Its expression in tumor cells specifically impacts invasion, recurrence, and survival through direct interaction with the tumor microenvironment. Based on digital image analysis of αSMA expression in tumor cells, we defined three main subgroups of BC with different behavior, recurrence, and survival. Further studies must be developed to elucidate the impact of tumor cell αSMA expression on other clinicobiological parameters, such as therapy response, disease-free survival, or recurrence.

Acknowledgments

The present work and its publication fees are financially supported by the Doctoral School and Research Department of Victor Babeș University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timisoara, Romania. We extend our gratitude to the Academic Head for this invaluable support. We are thankful to Oncohel Clinic for providing us with formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens for the current analysis.

Disclosures

Human subjects: Consent for treatment and open access publication was obtained or waived by all participants in this study. Research Ethics Council of the Victor Babeș University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timișoara issued approval 49/28.09.2018. This research was started after all consents were obtained and after receiving approval from the Ethics Committee of Victor Babeș University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timisoara, Romania (No. 49/28.09.2018).

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

Conflicts of interest: In compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the following:

Payment/services info: All authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work.

Financial relationships: All authors have declared that they have no financial relationships at present or within the previous three years with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work.

Other relationships: All authors have declared that there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: Anca Maria Cimpean, Mihaela-Maria Pasca Fenesan, Eugen Melnic, Alina Gabriela Negru, Andrei Alexandru Cosma, Gabriel Veniamin Cozma

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Anca Maria Cimpean, Mihaela-Maria Pasca Fenesan, Eugen Melnic, Andrei Alexandru Cosma, Gabriel Veniamin Cozma

Drafting of the manuscript: Anca Maria Cimpean, Mihaela-Maria Pasca Fenesan, Eugen Melnic, Alina Gabriela Negru, Andrei Alexandru Cosma, Gabriel Veniamin Cozma

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Anca Maria Cimpean, Mihaela-Maria Pasca Fenesan, Eugen Melnic, Alina Gabriela Negru

Supervision: Anca Maria Cimpean, Mihaela-Maria Pasca Fenesan, Eugen Melnic, Alina Gabriela Negru, Andrei Alexandru Cosma, Gabriel Veniamin Cozma

References

- 1.Trends in incidence, prevalence, and survival of breast cancer in the United Kingdom from 2000 to 2021. Barclay NL, Burn E, Delmestri A, et al. Sci Rep. 2024;14:19069. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-69006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI1) promotes actin cytoskeleton reorganization and glycolytic metabolism in triple-negative breast cancer. Humphries BA, Buschhaus JM, Chen YC, et al. Mol Cancer Res. 2019;17:1142–1154. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-18-0836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The cytoskeletal protein cyclase-associated protein 1 (CAP1) in breast cancer: context-dependent roles in both the invasiveness and proliferation of cancer cells and underlying cell signals. Hasan R, Zhou GL. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20 doi: 10.3390/ijms20112653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Actin structure and function. Dominguez R, Holmes KC. Annu Rev Biophys. 2011;40:169–186. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-042910-155359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The actin cytoskeleton: morphological changes in pre- and fully developed lung cancer. Basu A, Paul MK, Weiss S. Biophys Rev (Melville) 2022;3:41304. doi: 10.1063/5.0096188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Involvement of actin and actin-binding proteins in carcinogenesis. Izdebska M, Zielińska W, Hałas-Wiśniewska M, Grzanka A. Cells. 2020;9 doi: 10.3390/cells9102245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The remodelling of actin composition as a hallmark of cancer. Suresh R, Diaz RJ. Transl Oncol. 2021;14:101051. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diagnostic significance of the immunoexpression of CD34 and smooth muscle cell actin in benign and malignant tumors of the breast. Cîmpean AM, Raica M, Nariţa D. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16286998/ Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2005;46:123–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myoepithelial cells are a dynamic barrier to epithelial dissemination. Sirka OK, Shamir ER, Ewald AJ. J Cell Biol. 2018;217:3368–3381. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201802144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reassessing breast cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) interactions with other stromal components and clinico-pathologic parameters by using immunohistochemistry and digital image analysis (DIA) Barb AC, Fenesan MP, Pirtea M, et al. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15 doi: 10.3390/cancers15153823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.CD34+ stromal cells/telocytes as a source of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast. Díaz-Flores L, Gutiérrez R, González-Gómez M, García MP, Díaz-Flores L Jr, Carrasco JL, Martín-Vasallo P. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22 doi: 10.3390/ijms22073686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Exploration of cancer associated fibroblasts phenotypes in the tumor microenvironment of classical and pleomorphic invasive lobular carcinoma. Batra H, Ding Q, Pandurengan R, et al. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1281650. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1281650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biomarker profile of invasive lobular carcinoma: pleomorphic versus classic subtypes, clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis analyses. Zhang Y, Luo X, Chen M, et al. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022;194:279–295. doi: 10.1007/s10549-022-06627-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The relationship between cancer associated fibroblasts biomarkers and prognosis of breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cui M, Dong H, Duan W, Wang X, Liu Y, Shi L, Zhang B. PeerJ. 2024;12:0. doi: 10.7717/peerj.16958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Identification of cancer-associated fibroblasts in circulating blood from patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ao Z, Shah SH, Machlin LM, et al. Cancer Res. 2015;75:4681–4687. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.TP53 upregulates α‑smooth muscle actin expression in tamoxifen‑resistant breast cancer cells. Kim S, You D, Jeong Y, Yu J, Kim SW, Nam SJ, Lee JE. Oncol Rep. 2019;41:1075–1082. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dimerization of EGFR and HER2 induces breast cancer cell motility through STAT1-dependent ACTA2 induction. Jeon M, You D, Bae SY, et al. Oncotarget. 2017;8:50570–50581. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deep learning and transfer learning identify breast cancer survival subtypes from single-cell imaging data. Yadav S, Zhou S, He B, Du Y, Garmire LX. Commun Med (Lond) 2023;3:187. doi: 10.1038/s43856-023-00414-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Comparison of mammosphere formation from stem-like cells of normal breast, malignant primary breast tumors, and MCF-7 cell line. Ambrose JM, Veeraraghavan VP, Vennila R, et al. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2022;34:51. doi: 10.1186/s43046-022-00152-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.lncRNA ACTA2-AS1 predicts malignancy and poor prognosis of triple-negative breast cancer and regulates tumor progression via modulating miR-532-5p. Peng Y, Huang X, Wang H. BMC Mol Cell Biol. 2022;23:34. doi: 10.1186/s12860-022-00432-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epithelial to mesenchymal transition and breast cancer. Tomaskovic-Crook E, Thompson EW, Thiery JP. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:213. doi: 10.1186/bcr2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer relates to the basal-like phenotype. Sarrió D, Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, Hardisson D, Cano A, Moreno-Bueno G, Palacios J. Cancer Res. 2008;68:989–997. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Comparison of the HER2, estrogen and progesterone receptor expression profile of primary tumor, metastases and circulating tumor cells in metastatic breast cancer patients. Aktas B, Kasimir-Bauer S, Müller V, et al. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:522. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2587-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Circulating tumor cells: from new biological insights to clinical practice. Gu X, Wei S, Lv X. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:226. doi: 10.1038/s41392-024-01938-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.c-Src differentially regulates the functions of microtentacles and invadopodia. Balzer EM, Whipple RA, Thompson K, et al. Oncogene. 2010;29:6402–6408. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nuclear actin regulates cell proliferation and migration via inhibition of SRF and TEAD. McNeill MC, Wray J, Sala-Newby GB, et al. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2020;1867:118691. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2020.118691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matrix density-induced mechanoregulation of breast cell phenotype, signaling and gene expression through a FAK-ERK linkage. Provenzano PP, Inman DR, Eliceiri KW, Keely PJ. Oncogene. 2009;28:4326–4343. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Genetic variation drives cancer cell adaptation to ECM stiffness. Wang TC, Sawhney S, Morgan D, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024;121:0. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2403062121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cancer cell mechanobiology: a new frontier for cancer research. Yu W, Sharma S, Rao E, Rowat AC, Gimzewski JK, Han D, Rao J. J Natl Cancer Cent. 2022;2:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jncc.2021.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The matrix environmental and cell mechanical properties regulate cell migration and contribute to the invasive phenotype of cancer cells. Mierke CT. Rep Prog Phys. 2019;82:64602. doi: 10.1088/1361-6633/ab1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]