Abstract

目的

对系统性红斑狼疮(systemic lupus erythematosus, SLE)患者进行临床分层,分析不同活动度患者的临床特征,并探讨关键临床指标在SLE疾病活动度评估中的应用价值及评估模型的构建。

方法

回顾性分析1995年5月至2014年4月北京大学人民医院确诊的SLE患者临床资料。收集患者的人口学信息、临床表现、实验室检查结果,根据SLE疾病活动度指数2000(systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000, SLEDAI-2000)将患者分为疾病活动组与无疾病活动组。采用t检验、Mann-Whitney U检验以及χ2检验比较两组间差异,并使用Spearman相关性分析评估疾病活动组中与SLE活动度相关的临床指标。基于统计学分析结果,构建了逻辑回归模型,并对模型性能进行评估。

结果

两组在基本人口学特征上差异无统计学意义。疾病活动组中,抗核抗体(antinuclear antibodies,ANA)及抗双链DNA抗体(anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies,anti-dsDNA)阳性率升高;白细胞计数(white blood cell, WBC)、红细胞计数(red blood cell, RBC)、血红蛋白(hemoglobin, HGB)、淋巴细胞(lymphocytes, LY)、总蛋白(total protein, TP)、白蛋白(albumin, ALB)及补体C3水平显著降低,免疫球蛋白A(immunoglobulin A,IgA)、免疫球蛋白G(immunoglobulin G, IgG)水平明显升高。相关性分析结果显示,血红蛋白、白蛋白、补体C3和补体C4与其他临床指标相比具有更高的相关性指数,其中补体C3与疾病活动度具有一定负相关性。基于12项差异具有统计学意义的指标构建的逻辑回归模型准确率为91.4%,敏感性为94.4%,特异性为81.0%,受试者工作特征曲线(receiver operating characteristic, ROC)的线下面积(area under curve, AUC)为0.944。

结论

全面评估与SLE疾病活动度相关的临床指标,以实验室检查指标为主构建的逻辑回归模型能够较准确地评估SLE患者疾病活动度,为SLE患者的个体化治疗提供参考。

Keywords: 系统性红斑狼疮, 临床分层, 疾病活动度, 临床指标

Abstract

Objective

To stratify systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients clinically, to analyze the clinical characteristics of patients with and without disease activity, and to explore the application va-lue of key clinical indicators in assessing disease activity, as well as to construct an evaluation model.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted on clinical data of the SLE patients diagnosed at Peking University People' s Hospital from May 1995 to April 2014. Demographic information, clinical manifestations, laboratory tests, and antibody detection results were collected. The patients were divided into active and inactive groups based on systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000(SLEDAI-2000)scores. t-tests, Mann-Whitney U tests, and χ2 tests were used to compare the differences between the groups. Spearman correlation analysis was used to evaluate the relevant clinical indicators associated with SLE activity in the active disease group. Based on the results of statistical analysis, a Logistic regression model was constructed, and the performance of the model was evaluated.

Results

No significant differences were found in demographic characteristics between the two groups. In the active disease group, positive rates of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies (anti-dsDNA) were increased; white blood cell count (WBC), red blood cell count (RBC), hemoglobin (HGB), lymphocytes (LY), total protein (TP), albumin (ALB), and complement 3(C3) levels were significantly decreased; while immunoglobulin A and G levels were markedly elevated. The correlation analysis results showed that hemoglobin, albumin, C3, and complement 4(C4) had higher correlation indices compared with other clinical indicators. Among these, C3 exhibited a certain negative correlation with disease activity. The Logistic regression model based on 12 significantly different indicators (P < 0.05) achieved an accuracy of 91.4%, sensitivity of 94.4%, specificity of 81.0%, and the area under curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) was 0.944.

Conclusion

This study comprehensively evaluated a range of clinical indicators related to SLE disease activity, providing a thorough understanding of both laboratory and clinical markers. The Logistic regression model, which was primarily constructed using laboratory test indicators, such as inflammatory markers, immune response parameters, and organ involvement metrics, demonstrated a high degree of accuracy in assessing the disease activity in SLE patients. Consequently, this model might provide a new basis for the diagnosis and treatment of SLE patients, offering significant clinical diagnostic value.

Keywords: Systemic lupus erythematosus, Clinical stratification, Disease activity, Clinical indicators

系统性红斑狼疮(systemic lupus erythematosus,SLE)是一种慢性自身免疫性疾病,其特征为机体免疫系统攻击自身组织和器官,导致广泛的炎症和组织损伤[1]。SLE的临床表现多样,症状范围从轻微的皮疹和关节痛到严重的肾脏、心脏及中枢神经系统损伤等,给患者的生活质量带来显著影响[2]。为了有效评估SLE患者的病情,疾病活动度评分成为临床管理中的重要工具,能够反映患者当前疾病的严重程度和指导临床诊疗[3]。常用的评分体系包括SLE疾病活动性指数2000(systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000, SLEDAI-2000)[4]、英国狼疮评估组指数(British Isles lupus assessment group index, BILAG)[5]和系统性红斑狼疮国际合作临床小组疾病活动指数(systemic lupus international collaborating clinics damage index, SLICC)[6]等,这些评分系统结合了临床症状和实验室检查结果。

通过对SLE患者疾病活动度评分,医生可以连续监测疾病进展,并根据不同的活动阶段动态调整治疗策略,从而提高患者的治疗效果。尽管现有评分系统在临床应用中发挥了重要作用,但仍需进一步探索客观的临床指标,以提高SLE的诊断率和对疾病活动状态的判断。因此,本研究旨在回顾性分析SLE患者的各项临床指标与疾病活动度之间的关系,寻找能够客观反映疾病活动状态的临床诊断指标,为临床医生在评估SLE疾病活动情况时提供更为及时有效的参考依据。

1. 资料与方法

1.1. 病例资料

本研究为单中心回顾性研究,选择1995年5月至2014年4月在北京大学人民医院就诊的资料完善的SLE患者309例,均符合诊断标准《美国风湿病学会1997年系统性红斑狼疮分类标准》。收集患者的一般资料(包括年龄、性别、家族史)、临床表现及实验室检查等临床数据。

对于临床表现,若患者存在皮疹、光过敏、关节炎/关节痛、肌炎、脱发、口腔溃疡、浆膜炎、雷诺现象(Raynaud phenomenon)、发热、心脏损害中任意一项或多项,均被记为存在临床表现。

每个患者样本根据SLEDAI-2000评分标准进行了疾病活动度评分,将评分≤4分的患者定义为无疾病活动,>4分的患者定义为有疾病活动。根据以上分组标准,309例患者中71例患者被分为无疾病活动组,剩余238例患者被分为有疾病活动组。

1.2. 统计学分析

使用Python编程语言中的SciPy库进行组间差异的统计分析。对于连续型变量,首先使用Kolmo-gorov-Smirnov检验评估其正态性分布情况,符合正态分布的连续变量以均数±标准差(x ±s)表示,组间比较采用独立样本t检验;不符合正态分布的连续型变量则以中位数(四分位数) [M(P25,P75)]表示,组间比较采用Mann-Whitney U检验。分类变量以频数(百分比)[n (%)]表示,组间比较采用χ2检验。所有统计分析采用双侧检验,P < 0.05认为差异有统计学意义。使用Spearman相关性分析评估疾病活动组中与SLE活动度相关的临床指标。当|r| > 0.4时,认为两个变量之间存在一定相关性,当|r| > 0.7时,认为两个变量之间存在较强相关性。

1.3. 逻辑回归分析

基于统计学分析结果,构建了逻辑回归模型以评估SLE患者是否有疾病活动度。为确保模型输入数据的结构化,对收集到的原始数据中离散型和连续型数据分别进行了以下数据清洗处理:(1)对于少量存在缺失值的抗体检查相关的离散型数据项,以0值作为默认值进行填充;(2)对于包含字符型变量以及滴度信息的抗体检查相关离散型数据项,采用One-Hot编码将其按照分类情况统一转换为多维的数值型编码进行模型分析;(3)对所有连续型数据项进行标准化处理以减少数据项间值域差距过大给模型分析造成的负面影响,具体方法为计算数据的均数和标准差,然后用这些值对数据进行标准化,即减去均数并除以标准差,使数据具有零均数和单位方差。

在模型构建过程中,选择差异具有统计学意义的数据项进行逻辑回归分析。每次模型训练中,随机抽取有疾病活动组与无疾病活动组中70%的样本作为训练集,30%的样本作为测试集。

用于评估模型性能的指标包括准确率,即模型正确预测的比例;敏感性,即模型对有疾病活动度的检测能力;特异性,即模型对无疾病活动度的检测能力。此外,通过绘制ROC评估模型在不同置信度下的表现,以全面评估模型性能。

2. 结果

2.1. SLE患者疾病活动组与非疾病活动组临床特征比较

共纳入309例SLE患者,其中有疾病活动入组238例,无疾病活动入组71例。对两组患者相关指标进行了统计学分析,详见表 1。

表 1.

有疾病活动组与无疾病活动组临床数据项对比

Comparison of clinical data items between active disease group and inactive disease group

| Items | No activity (n=71) | Active (n=238) | χ2/U/t | P |

| KWBC, white blood cell; RBC, red blood cell; PLT, platelet;TP, total protein;ANA, antinuclear antibodies; Anti-dsDNA, anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies; Anti-Ro/SS-A, anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies; Anti-La/SS-B, anti-La/SS-B antibodies; Anti-U1RNP, anti-U1 ribonucleoprotein antibo-dies; Anti-Sm, anti-Smith antibodies; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M; C3, complement 3; C4, complement 4. | ||||

| Gender, n (%) | 8 658.00 | 0.550 | ||

| Female | 65 (91.55) | 212 (89.08) | ||

| Male | 6 (8.45) | 26 (10.92) | ||

| Onset age/years, M (P25, P75) | 26 (21, 35) | 28 (21, 38) | 8 938.50 | 0.459 |

| Family history, n (%) | 3 (4.23) | 21 (8.82) | 8 837.50 | 0.205 |

| Clinical manifestations, n (%) | 60 (84.51) | 227 (95.38) | 10 331.50 | 0.004 |

| Creatinine/(μmoI/L), M (P25, P75) | 58.0 (45.5, 78.5) | 57.0 (46.0, 74.0) | 8 392.50 | 0.932 |

| WBC/(×109/L), M (P25, P75) | 7.10 (5.18, 10.35) | 5.08 (3.36, 7.35) | 5 282.00 | < 0.001 |

| RBC/(×1012/L), M (P25, P75) | 3.68 (3.42, 4.11) | 3.53 (2.98, 4.04) | 6 981.00 | 0.017 |

| Hemoglobin/(g/L), M (P25, P75) | 113.7 (105.2, 127.0) | 105.5 (90.1, 121.0) | 6 321.50 | < 0.001 |

| Hematocrit/%, M ( P25, P75 ) | 32.10 (0.39, 36.75) | 27.80 (5.65, 34.48) | 7 364.50 | 0.097 |

| PLT/(×109/L), x ±s | 160.83 ± 82.57 | 165.77 ± 94.02 | 0.40 | 0.688 |

| Lymphocytes/(×109/L), M (P25, P75) | 1.40 (1.00, 2.04) | 1.00 (0.67, 1.40) | 5 951.50 | < 0.001 |

| TP/(g/L), x ±s | 67.62 ± 9.80 | 64.09 ± 13.12 | -2.09 | 0.038 |

| Albumin/(g/L), x ±s | 39.29 ± 5.74 | 33.74 ± 6.87 | -6.16 | < 0.001 |

| ANA, n (%) | 46 (68.66) | 194 (85.46) | 10.96 | 0.001 |

| Anti-dsDNA, n (%) | 18 (27.27) | 119 (55.35) | 12.25 | < 0.001 |

| Anti-Ro/SS-A, n (%) | 19 (12.86) | 82 (36.60) | 1.99 | 0.158 |

| Anti-La/SS-B, n (%) | 7 (10.00) | 19 (8.56) | 0.05 | 0.832 |

| Anti-U1RNP, n (%) | 17 (24.29) | 66 (31.27) | 0.15 | 0.703 |

| Anti-Sm, n (%) | 9 (12.86) | 34 (15.38) | 0.03 | 0.870 |

| IgA/(g/L), M ( P25, P75) | 2.35 (1.71, 2.91) | 2.81 (2.07, 3.87) | 8 598.50 | 0.004 |

| IgG/(g/L), M (P25, P75) | 12.7 (10.12, 17.7) | 16 (10.93, 22.08) | 10 302.00 | 0.014 |

| IgM/(g/L), M (P25, P75 ) | 0.98 (0.64, 1.57) | 1.14 (0.71, 1.54) | 10 071.00 | 0.258 |

| C3/(g/L), M (P25, P75) | 0.86 (0.61, 1.00) | 0.51 (0.36, 0.75) | 9 139.00 | < 0.001 |

| C4/(g/L), M (P25, P75) | 0.16 (0.11, 0.21) | 0.11 (0.06, 0.16) | 7 017.00 | 0.345 |

一般资料方面,经Man-Whitney U检验分析,两组患者在性别构成、年龄分布及家族史比例方面差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05)。

临床表现方面,有疾病活动组患者的临床表现发生率显著高于无疾病活动组。免疫指标检测方面,有疾病活动组的抗核抗体(antinuclear antibo-dies,ANA)阳性率及抗双链DNA抗体(anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies,anti-dsDNA)阳性率均显著高于无疾病活动组。然而,两组在抗Ro/SS-A抗体(anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies, anti-Ro/SS-A)、抗La/SS-B抗体(anti-La/SS-B antibodies, anti-La/SS-B)、抗U1RNP抗体(anti-U1 ribonucleoprotein antibodies, anti-U1RNP)和抗Sm抗体(anti-Smith antibodies, anti-Sm)的阳性率差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。

血液学指标方面,有疾病活动组的白细胞计数、红细胞计数和血红蛋白水平均显著低于无疾病活动组,淋巴细胞计数在有疾病活动组也显著降低(P < 0.05)。

生化指标方面,有疾病活动组的总蛋白和白蛋白水平均显著低于无疾病活动组(P < 0.05)。

免疫球蛋白方面,有疾病活动组的免疫球蛋白(immunoglobulin, Ig)A和IgG水平均显著高于无疾病活动组(P < 0.05),而IgM水平差异无统计学意义(P=0.258)。

补体方面,有疾病活动组的C3水平显著低于无疾病活动组(P < 0.001),而C4水平差异无统计学意义(P=0.345)。

2.2. SLE疾病活动组临床指标相关性分析

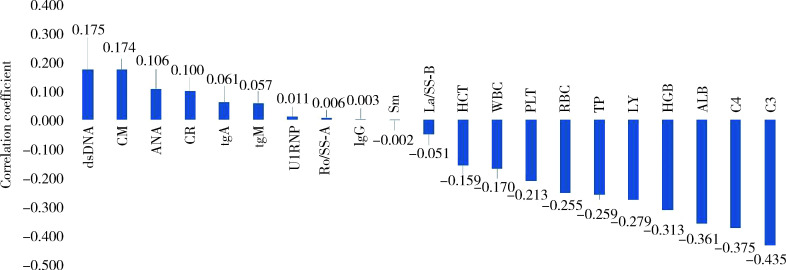

对有疾病活动的238例患者的样本中各个临床项与疾病活动度间的关联进行评估,详情如图 1和表 2所示。

图 1.

疾病活动组实验室检查项与SLEDAI-2000评分的相关性分析

Correlation analysis of laboratory test indicators with SLEDAI-2000 scores in patients from the active disease group

SLEDAI-2000, systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000; dsDNA, anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies; CM, clinical manifestations; ANA, antinuclear antibody; CR, creatinine; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IgM, immunoglobulin M; U1RNP, anti-U1 ribonucleoprotein antibodies; Ro/SS-A, anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies; IgG, immunoglobulin G; Sm, anti-Smith antibodies; La/SS-B, anti-La/SS-B antibodies; HCT, hematocrit; WBC, white blood cell; PLT, platelet; RBC, red blood cell; TP, total protein; LY, lymphocytes; HGB, hemoglobin; ALB, albumin C4, complement 4; C3, complement 3.

表 2.

疾病活动组实验室检查项与疾病活动度相关性分析

Analysis results for the correlation between laboratory test indicators and SLEDAI-2000 scores in patients from the active disease group

| Items | r | P |

| kSLEDAI-2000, systemic lupus erythematosus disese activity index 2000; Anti-dsDNA, anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies; ANA, anti-nuclear antibody; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IgM, immunoglobulin M; Anti-U1RNP, anti-U1RNP antibodies; Anti-Ro/SS-A, anti-Ro antibodies; IgG, immunoglobulin G; Anti-Sm, anti-Smith antibodies; Anti-La/SS-B, anti-La/SS-B antibodies; WBC, white blood cell; PLT, platelet; RBC, red blood cell; TP, total protein; C4, complement 4; C3, complement 3. | ||

| Anti-dsDNA | 0.175 | 0.007 |

| Clinical manifestations | 0.174 | 0.008 |

| ANA | 0.106 | 0.104 |

| Creatinine | 0.010 | 0.127 |

| IgA | 0.061 | 0.356 |

| IgM | 0.057 | 0.381 |

| Anti-U1RNP | 0.011 | 0.869 |

| Anti-Ro/SS-A | 0.006 | 0.926 |

| IgG | 0.003 | 0.969 |

| Anti-Sm | -0.002 | 0.979 |

| Anti-La/SS-B | -0.052 | 0.432 |

| Hematocrit | -0.159 | 0.015 |

| WBC | -0.170 | 0.009 |

| PLT | -0.213 | 0.001 |

| RBC | -0.255 | < 0.001 |

| TP | -0.259 | < 0.001 |

| Lymphocytes | -0.279 | < 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin | -0.313 | < 0.001 |

| Albumin | -0.361 | < 0.001 |

| C4 | -0.375 | < 0.001 |

| C3 | -0.435 | < 0.001 |

在抗体层面,anti-dsDNA抗体相关性评估指标最高(r = 0.175),其他抗体指标相关性评估得到的r值均低于0.1。在血液学指标方面,各个指标与疾病活动度评分明显高于抗体层面,其中血红蛋白与疾病活动度在同类型指标中相关性系数最高(r=-0.313)。生化指标方面,与疾病活动度相关性最高的指标为白蛋白(r=-0.361)。IgA、IgG、IgM在相关性分析中并未显示与疾病活动度有明显相关性,而补体方面,补体C3显示在同类型指标中相关性最高,且与疾病活动度具有的一定的负相关性(r=-0.435)。

2.3. SLE疾病活动度分类模型

基于前述分析结果,构建了机器学习模型,用于评估SLE患者疾病活动阶段,即有疾病活动(SLEDAI-2000>4)和无疾病活动(SLEDAI-2000≤4)。模型采用逻辑回归算法,使用最大似然估计法进行参数优化,以确保模型的最佳性能。

模型的构建基于第2.1小节的统计分析结果,从所有实验室检查指标中选择差异有统计学意义(P < y0.05)的12项实验室检查指标作为模型输入变量,这些指标包括:临床表现、白细胞计数、红细胞计数、血红蛋白、淋巴细胞计数、总蛋白、白蛋白、ANA、anti-dsDNA抗体、IgA、IgG和补体C3。

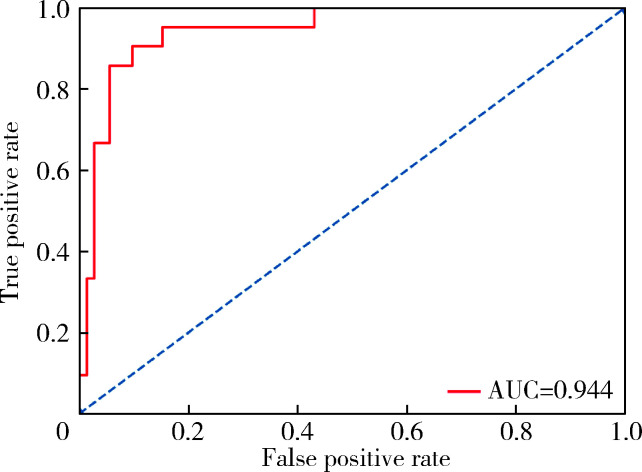

对模型的性能进行全面评估,如图 2所示。

图 2.

逻辑回归模型ROC曲线

ROC curve of the Logistic regression model

ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under curve.

在模型中输入临床诊断数据,计算得到是否存在活动性的置信度,计算公式如下:

|

其中wi为模型对各个指标赋予的权重系数,xi为指标原始值。最优模型对于各项指标的权重系数w如表 3所示,其中ANA抗体包含滴度等级信息,不同等级通过One-Hot编码后由1维转为11维;anti-dsDNA抗体指标包含阴阳性信息,经编码后由1维转为2维。在预测疾病活动性时,将原始数据直接输入模型,模型对原始数据进行格式转换,并乘以各个指标的权重系数,计算样本是否存在疾病活动的置信度。对最优模型进行评估后,预测SLE有/无活动度的准确率为91.4%,有疾病活动预测的敏感性为94.4%,无疾病活动预测的特异性为81.0%。利用ROC曲线评估的AUC为0.944,该结果表明,通过统计学分析筛选出的12项指标能够有效预测SLE的疾病活动度。

表 3.

逻辑回归模型中各项指标权重系数

Weight coefficients of each indicator in the Logistic regression model

| Items | w |

| The antinuclear antibody was transformed from 1 dimension to 11 dimensions after One-Hot encoding; the anti-dsDNA antibodies were transformed from 1 dimension to 2 dimensions after One-Hot encoding. WBC, white blood cell; RBC, red blood cell; TP, total protein; ANA, antinuclear antibody; Anti-dsDNA, anti-double-stranded DNA antibo-dies; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IgG, immunoglobulin G; C3, complement 3. | |

| Clinical manifestations | -0.238 |

| WBC | 0.141 |

| RBC | -0.197 |

| Hemoglobin | 0.118 |

| Lymphocytes | 0.024 |

| TP | -0.275 |

| Albumin | 0.543 |

| ANA-1 | -0.134 |

| ANA-2 | 0.000 |

| ANA-3 | 0.108 |

| ANA-4 | 0.253 |

| ANA-5 | -0.003 |

| ANA-6 | -0.009 |

| ANA-7 | -0.362 |

| ANA-8 | -0.105 |

| ANA-9 | -0.078 |

| ANA-10 | 0.000 |

| ANA-11 | 0.329 |

| Anti-dsDNA-1 | 0.180 |

| Anti-dsDNA-2 | -0.180 |

| IgA | -0.033 |

| IgG | 0.040 |

| C3 | 0.256 |

3. 讨论

SLE是一种复杂的自身免疫性疾病,其病情波动性大,表现为缓解期与发作期交替出现。及时、准确、客观评估疾病活动度对SLE患者治疗质量和预后管理至关重要[7-8]。

本研究根据SLEDAI-2000评分将SLE患者分为有疾病活动组和无疾病活动组,并对两组间的临床指标进行了统计分析,结果显示,多项常规血液检查指标与SLE疾病活动度可能存在密切关联,红细胞计数、血红蛋白、白细胞计数及淋巴细胞计数等指标的变化反映了机体炎症反应和免疫系统的异常状态[9-11],这些临床检查指标的统计分析结果为临床实践中评估SLE患者的疾病活动状态提供了参考。此外,anti-dsDNA抗体、IgA、补体C3等免疫学指标在组间差异有统计学意义。这些发现与既往研究结果一致,进一步证实了这些指标在评估SLE疾病活动度中的重要性[12-14]。

本研究对处于疾病活动状态的患者样本的临床指标进行了疾病活动度相关性分析,结果显示,血红蛋白、白蛋白、补体C4与疾病活动度存在较弱的负相关,而补体C3在相关性分析中与疾病活动度显示了一定的相关性,在疾病活动期监测补体C3水平的变化可能有助于评估疾病进展。

近年来一些研究对不同疾病活动度评分体系进行了评估,并比较了之间的差异。研究显示,SLEDAI-2000与2019“新标准”系统性红斑狼疮疾病活动度评分(systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity score, SLE-DAS)对于患者的实时疾病活动情况可以做到有效评估,但检测SLE疾病活动性变化的能力有限[15-16]。对于BILAG评分,有研究将其与SLEDAI-2000进行了对比,并利用ROC曲线比较两者评分性能。相较SLEDAI-2000,BILAG评分具有更高的AUC,且对于肾脏损害评估更加可靠[17],但该评分体系中缺失了anti-dsDNA抗体、补体C3/C4等经临床证实的特异性免疫指标,在评估全身系统活动时具有一定劣势。此外,以上评分标准需要依赖较多的临床数据项完成评分,当患者存在明显的检查项缺失的情况下,很难对患者疾病活动情况完成评估。

本研究通过构建逻辑回归模型,将两组间差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.05)的12个常见临床指标(表 1)整合为协变量,探究其对SLE疾病活动性的提示作用,最终模型预测SLE患者是否有活动性(SLEDAI-2000> 4)的判读准确率为91. 4%,ROC评价下的AUC为0.944。模型可以忽略一些离散型指标缺失带来的影响,这意味着即使在临床表现不足或部分抗体指标缺失的情况下,依旧可以准确地判定患者当前病情是否处于活动状态。本研究也存在一些不足之处,在数据入组筛选阶段,剔除了部分关键检查项缺失或合并有其他自身免疫性疾病的患者样本,这导致最终用于分析的数据集缺乏近期的样本,因此,研究结果可能无法全面反映当前的临床实践情况。针对这一问题,未来计划在后续研究中收集更多近期病例,以增加样本的代表性和数据的时效性。

综上所述,本研究全面评估了与SLE疾病活动度相关的临床指标,以实验室检测指标为主构建的逻辑回归模型能够较准确地评估SLE患者疾病活动度,为SLE患者的诊疗可能提供了新的依据,具有一定的临床应用价值。

Funding Statement

国家自然科学基金(31970648)

Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31970648)

Footnotes

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

作者贡献声明 王红彦:提出研究思路,收集、整理数据,修改论文;李鑫铭:设计研究方案,分析数据,撰写论文;房柯池:提出研究思路,修改论文;朱华群:提出研究思路;贾汝琳:提出研究思路,总体把关和审定论文;王晶:总体把关和审定论文。

Contributor Information

贾 汝琳 (Rulin JIA), Email: 1036013457@qq.com.

王 晶 (Jing WANG), Email: wangjing@psych.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Barber MRW, Drenkard C, Falasinnu T, et al. Global epidemio-logy of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021;17(9):515–532. doi: 10.1038/s41584-021-00668-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz N, Stock AD, Putterman C. Neuropsychiatric lupus: New mechanistic insights and future treatment directions. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2019;15(3):137–152. doi: 10.1038/s41584-018-0156-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stamm TA, Bauernfeind B, Coenen M, et al. Concepts important to persons with systemic lupus erythematosus and their coverage by standard measures of disease activity and health status. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2007;57(7):1287–1295. doi: 10.1002/art.23013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gladman DD, Ibañez D, Urowitz MB, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(2):288–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isenberg DA, Rahman A, Allen E, et al. BILAG 2004. Development and initial validation of an updated version of the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group's disease activity index for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44(7):902–906. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutton EJ, Davidson JE, Bruce IN. The systemic lupus international collaborating clinics (SLICC) damage index: A systematic literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;43(3):352–361. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emamikia S, Oon S, Gomez A, et al. Impact of remission and low disease activity on health-related quality of life in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2022;61(12):4752–4762. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keac185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Han M, Pedigo CE, et al. Chinese herbal medicine for systemic lupus erythematosus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Chin J Integr Med. 2021;27(10):778–787. doi: 10.1007/s11655-021-3497-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen C, Wang L, Han B, et al. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in hospitalized patients: 450 patients and their red blood cell transfusions. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(2):e18739. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000018739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yin X, Kim K, Suetsugu H, et al. Biological insights into syste-mic lupus erythematosus through an immune cell-specific transcriptome-wide association study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(9):1273–1280. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2022-222345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tobón GJ, Izquierdo JH, Cañas CA. B lymphocytes: Development, tolerance, and their role in autoimmunity-focus on systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmune Dis. 2013;2013(1):827254. doi: 10.1155/2013/827254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Xiao S, Xia Y, et al. The therapeutic strategies for SLE by targeting anti-dsDNA antibodies. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2022;63(2):152–165. doi: 10.1007/s12016-021-08898-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qiu W, Yu T, Deng GM. The role of organ-deposited IgG in the pathogenesis of multi-organ and tissue damage in systemic lupus erythematosus. Front Immunol. 2022;13:924766. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.924766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lundtoft C, Sjöwall C, Rantapää-Dahlqvist S, et al. Strong association of combined genetic deficiencies in the classical complement pathway with risk of systemic lupus erythematosus and primary Sjögren' s syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022;74(11):1842–1850. doi: 10.1002/art.42270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jesus D, Rodrigues M, Matos A, et al. Performance of SLEDAI-2K to detect a clinically meaningful change in SLE disease activity: A 36-month prospective cohort study of 334 patients. Lupus. 2019;28(5):607–612. doi: 10.1177/0961203319836717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koo M, Lu MC. Performance of a new instrument for the measurement of systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity: The SLE-DAS. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023;59(12):2097. doi: 10.3390/medicina59122097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.王 蒙, 韩 迪迪, 王 力宁, et al. 系统性红斑狼疮两种评分系统对狼疮肾炎活动临床评价的比较. 中华风湿病学杂志. 2016;20(6):391–395. [Google Scholar]