Abstract

Dehydrogenative coupling (DC) reactions are of importance for the construction of new carbon‐element bonds in synthetic organic chemistry. In this work, we report on the synthesis and characterization of several redox‐active guanidino‐functionalized aromatic molecules (GFAs) for use in DC (C−C and C−O) reactions. In a systematic approach, we first characterize the new DC reagents in all relevant redox and protonation states, and compare their performance in competitive test proton‐coupled electron transfer (PCET) reactions. Then, their use in four different DC reactions with different mechanisms is evaluated.

Keywords: dehydrogenative coupling reactions, proton-coupled electron transfer, oxidative coupling, guanidines, redox-acive molecules

New redox‐active diguanidines are prepared, with the aim to optimize their proton‐coupled electron transfer properties. Then, their oxidized, dicationic redox states are applied in dehydrogenative coupling reactions, with radical cation (electron transfer) or arenium‐ion like (proton transfer) mechanisms. The molecules emerge as valuable (and in some cases superior) alternatives to traditionally applied benzoquinones such as DDQ.

Introduction

Dehydrogenative coupling (DC) reactions are frequently applied for the construction of new carbon‐element bonds.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ] A general equation for dehydrogenative C−E coupling reactions is given in Scheme 1. Often, these reactions are metal‐catalysed, but metal‐free DC reactions are also known.[ 1 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 12 ] Also, a variety of electrochemical oxidative coupling reactions have been developed.[ 6 , 16 , 17 , 18 ] Most of these reactions involve proton‐coupled electron transfer (PCET);[ 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ] two protons and two electrons are transferred to one or more reaction partners. (In electrochemistry, the electrons are transferred to an electrode.) Oxidative aryl‐aryl coupling reactions constitute one of the most important classes of DC reactions. Generally, these reactions follow either an arenium‐ion (proton transfer) or a radical cation (electron transfer) mechanism,[ 8 , 29 , 30 ] depending on the redox potential of the substrate and the reaction conditions (e. g. the excess of acid in the reaction mixture and the solvent).

Scheme 1.

General equation for the dehydrogenative coupling (DC) reaction to give a new carbon‐element bond. E=C or O in this work.

Recently, guanidino‐functionalized compounds were introduced by our group as a veratile class of PCET reagents.[ 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ] Scheme 2a shows the first example, 1,2,4,5‐tetrakis(tetramethylguanidino)‐benzene. Its two‐electron oxidation leads to stable salts of the dication. These salts were then used in several PCET reactions; they were also used as a redox catalyst in combination with dioxygen as terminal oxidant. [35] The strong Brønsted basicity of guanidino groups in the neutral, reduced form,[ 33 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ] and the restoration of the aromatic system are among the driving forces for PCET.

Scheme 2.

Illustration of the redox and protonation states relevant for the PCET reactivity of a) 1,2,4,5‐tetrakis(tetramethylguanidino)‐benzene, and b) 1,4‐bis(tetramethylguanidino)‐benzene (1).

Although these reactions generally require stoichiometric amounts of the redox‐active guanidine reagent, the reagent could easily be recycled, and diprotonated 1,2,4,5‐tetrakis(tetramethylguanidino)‐benzene could be re‐converted to the dicationic redox‐state by catalytic oxidation with air. [35]

Recently, we extended this PCET chemistry to p‐bisguanidino‐benzenes, e. g. 1,4‐bis(tetramethylguanidino)‐benzene (1, Scheme 2b).[ 40 , 41 ] The redox potential of this diguanidine molecule is higher than that of the tetraguanidine molecule, while the Brønsted basicity only slightly decreases. The potential for homolytic cleavage of an E−H bond by a PCET reagent in a given solvent depends on two factors, namely the reduction potential of the oxidized form and the pKa value of the corresponding protonated reduced form of the PCET reagent. Unfortunately, these two factors often operate in different directions. Hence, the increase of the reduction potential, that could be realized for example by substitution with electron‐withdrawing substituents, generally leads to a decrease of the pKa value (a more negative pKa value).[ 42 , 43 , 44 ] Due to this “leveling effect“, an optimal ballance of reduction potential and pKa value is required.

In this work, we report the synthesis of several new diguanidino‐benzene molecules (Figure 1) and their characterization in all redox and protonation states that are of relevance for their use in DC reactions. In competitive PCET test reactions between two different diguanidines and quantum‐chemical calculations, we then identify the most capable reagents for DC reactions. Finally, the performance of these diguanidines in DC reactions with different mechanisms is tested. The results indicate that these oxidative coupling reactions could follow either a radical cation (electron transfer) or an arenium‐ion like (proton transfer) mechanism. [8]

Figure 1.

Structures of the diguanidine molecules applied in this work. The molecules 3 and 4 were reported previously; all other GFA molecules are new. The molecules are grouped relative to 1 in low‐potential GFAs, with a reduction potential smaller (more negative) than 1, and high‐potential GFAs, with a reduction potential larger than 1.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Characterization of the New Redox‐Active Diguanidine Molecules in Their Reduced, Neutral Redox States

The new diguanidine molecules were first synthesized according to the equations shown in Scheme 3, and characterized in their neutral, reduced redox states. Reaction of 2‐chloro‐1,3‐dimethyl‐4,5‐dihydro‐1H‐imidazolium chloride with 4,5‐dichloro‐1,2‐phenylenediamine yielded 5 in a yield of 45 %. 6 was obtained in a yield of 60 % from the reaction of 1,4‐benzodioxine‐6,7‐bis(tetramethylguanidine) (3), synthesized as reported previously, [46] with N‐bromo‐succinimide (NBS). For the synthesis of 2 and 7, 2‐chloro‐N,N,N’,N’‐tetramethyl‐formamidinium chloride was reacted with 1,2‐dimethoxy‐4,5‐diamino‐benzene or 1,4‐diamino‐2,5‐dichloro‐benzene, respectively. After workup, the two molecules were obtained in yields of 80 % for 2 and 87 % for 7. Molecules 3 and 4 were synthesized as reported previously.[ 45 , 46 ]

Scheme 3.

Reaction equations for the synthesis of the high‐potential diguanidines 5, 6 and 7 (NBS=N‐bromo‐succinimide).

Crystals of 5, 6 and 7 suitable for a structural analysis by SCXRD were grown from hot hexane or CH3CN solutions. Figure 2 illustrates the structures of the three new redox‐active GFA molecules, and selected bond lengths of the low‐potential diguanidine 2 (previously synthesized in its reduced, neutral redox state) [45] and the three high‐potential diguanidines 5–7 are included in the Supporting Information. The imino C=N bonds within the guanidino groups measure 1.2948(11)/1.2894(11) Å in 2, 1.286(14) Å in 5, 1.302(15) Å in 6, and 1.301(3) Å in 7, values that fall into the typical range for intact guanidino N=C bonds. Protonation as well as oxidation elongate these bonds in a characteristic way (see below). In all cases, the CN3 planes of the guanidino groups are highly tilted with respect to the aromatic plane. As detailed previously, this conformation is favored for electronic reasons rather than steric constraint. [47]

Figure 2.

Illustration of the solid‐state structures of the three new high‐potential redox‐active diguanidine molecules 5, 6 and 7 in their neutral, reduced redox state. Displacement ellipsoids drawn at the 50 % probability level. Colour code: N blue, O red, C grey, Cl green.

All neutral GFA compounds display electronic absorption bands in the UV region. The lowest‐energy absorptions were measured at 318 nm for 2, 323 nnm for 3, ca. 320 nm for 5, 326 nm for 6, and 293 nm for 7. Oxidation will be shown to shift the lowest‐energy electronic absorptions to the visible region. Therefore, one can easily discriminate between the neutral and oxidized redox states by colour and electronic absorption spectra.

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements were carried out to determine the redox potentials for all molecules in CH2Cl2 solutions. The CV curves for the low potential diguanidine molecules 2 and 3 are reproduced in the Supporting Information, and Figure 3 displays the CV curves for the high potential diguanidine molecules 5 – 7. The potentials relative to the reference redox couple ferrocenium/ferrocene are summarized in Table 1. Please note that the potentials for 3 given in a previous work (ref. [46]) were slightly revised. The CV curve recorded for 5 shows two one‐electron redox events, clearly separated by 0.24 V. On the other hand, for 7 only one two‐electron redox event is visible.

Figure 3.

Cyclic voltammetry curves (CH2Cl2, Ag/AgCl reference electrode, 0.1 M N( n Bu)4(PF6) as supporting electrolyte, scan speed 100 mV s−1) measured in oxidation direction for the high potential diguanidine molecules 5 – 7. Potentials are given vs. the reference redox couple Fc+/Fc.

Table 1.

E 1/2 and E ox values (in V vs. the Fc+/Fc redox couple) from cyclic voltammetry measurements in CH2Cl2 solution (Faraday constant F=9.648456⋅104 C mol−1).

|

Compound |

1st redox (GFA⋅+/GFA0) E 1/2(1st)/E ox |

2nd redox (GFA2+/GFA⋅+) E 1/2(2nd)/E ox |

‐F [(E 1/2(1st)+E 1/2(2nd)] (2 ++2 e−→GFA) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2 |

−0.34 |

−0.34 |

+65.6 kJ mol−1 |

|

3 |

−0.32 (−0.26) |

−0.19 (−0.14) |

+49.2 kJ mol−1 |

|

4 |

−0.27 (0.02) |

−0.03 (0.32) |

+28.9 kJ mol−1 |

|

1 |

−0.23 (−0.14) |

−0.23 (−0.14) |

+44.4 kJ mol−1 |

|

5 |

−0.08 (−0.02) |

0.16 (0.23) |

−7.7 kJ mol−1 |

|

6 |

−0.09 (−0.02) |

−0.01 (0.05) |

+9.6 kJ mol−1 |

|

7 |

−0.01 (0.08) |

−0.01 (0.08) |

+1.9 kJ mol−1 |

Table 1 includes the ‐F⋅[(E 1/2(1st)+E 1/2(2nd)] values, that could be regarded as ΔG 0 values for the redox half‐reactions 2 ++2 e−→GFA. Of all compounds, 5 exhibits the lowest ‐F⋅[(E 1/2(1st)+E 1/2(2nd)] value, meaning that two‐electron reduction (5)2++2 e− →5 is more favored than for the other molecules. The following Gibbs free energy changes (Scheme 4) for redox reactions between one of the high‐potential GFA molecules and 1 were estimated from the potentials.

Scheme 4.

Gibbs free energy changes (at 298 K, 1 bar) for some competitive redox reactions in CH2Cl2 solution as estimated from the potentials measured in the cyclic voltammetry measurements.

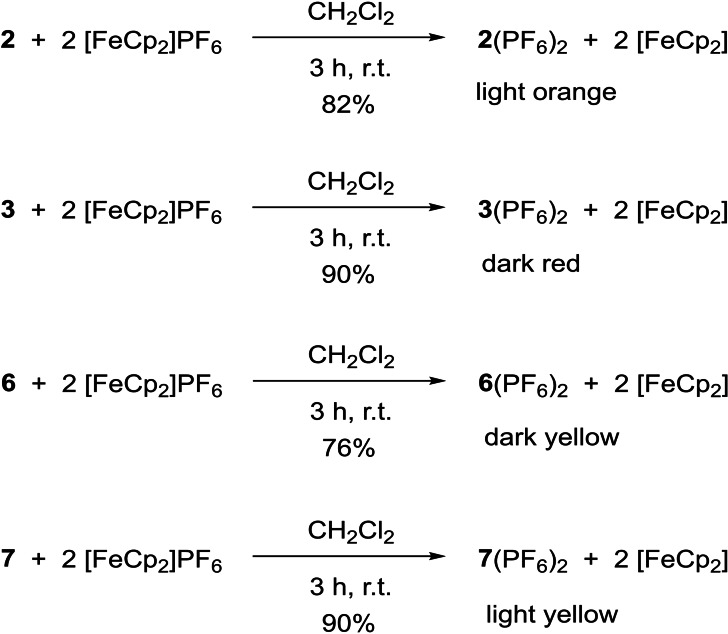

Synthesis and Characterization of the Oxidized, Dicationic Redox States

For the application of the diguanidines in dehydrogenative coupling reactions, they have to be stable and isolable in their oxidized, dicationic redox states. Therefore, the neutral GFA molecules were oxidized with two equivalents of FcPF6 in CH2Cl2 solutions (Scheme 5). In the case of 2, 6 and 7, the oxidized, dicationic redox states were obtained in the form of the hexafluorophosphate salts in yields of 82 % for 2(PF6)2, 76 % for 6(PF6)2, and 90 % for 7(PF6)2. In the case of 5, it was not possible to isolate the oxidized product in pure form. Therefore, although this compound is attractive due to its relatively high redox potential, its use in PCET and DC reactions was not further pursued. The low‐potential diguanidine 3 was also oxidized with FcPF6. The product, 3(PF6)2, was obtained in 90 % yield. Oxidation with the stronger oxidation reagent AgPF6 in CH3CN is not possible, since the silver ion coordinates to the guanidino groups. For example, reaction of 6 with AgPF6 in CH3CN solution gave the salt [Ag(6)(CH3CN)2]PF6. The compound was crystallized and structurally characterized (see illustration in Figure 4a), but not further studied.

Scheme 5.

Two‐electron oxidation of the diguanidines to give the hexafluorophosphate salts of the dications. Oxidation experiments with 5 failed to give a pure compound.

Figure 4.

a) Illustration of the structure of [Ag(6)(CH3CN)2]PF6. b) Illustration of the structures of the three salts 2(PF6)2, 6(PF6)2 and 7(PF6)2 of the oxidized, dicationic diguanidine molecules. Displacement ellipsoids drawn at the 50 % probability level. Colour code: N blue, O red, C grey, Cl light‐green, P orange, F dark‐green.

Crystals of the three compounds 2(PF6)2, 6(PF6)2, and 7(PF6)2 suitable for structural characterization by SCXRD were obtained from CH3CN solutions layered with Et2O; the resulting structures are sketched in Figure 4b. As expected, oxidation leads to an increase of the former imino N=C bonds (see tables in the Supporting Information); from 1.2948(11)/1.2894(11) Å in 2 to 1.387(2)/1.382(2) Å in 2(PF6)2, from 1.302(15) Å in 6 to 1.391(4) Å in 6(PF6)2, and from 1.301(3) Å in 7 to 1.402(2) Å in 7(PF6)2. By contrast, the C−N bond between the ring C atom and the imino N of the guanidino group shortens upon oxidation. Moreover, the variations in the C−C bond lengths of the C6 ring upon oxidation clearly signal loss of the aromatic system.

The UV‐vis spectra of the oxidized, dicationic GFAs show bands in the visible region, centered at 464 nm for 2(PF6)2, 509 nm for 3(PF6)2, 573 nm for 6(PF6)2, and a broad band centered around 370 nm for 7(PF6)2.

Characterization of the Radical Monocationic Redox State

The radical monocationic redox states could not be isolated, since they are in an equilibrium with the neutral and dicationic redox states. The Gibbs free energy for their disproportionation to the neutral and dicationic molecules were estimated from the CV measurements, using the equation ΔGdispF⋅ΔE 1/2 (ΔE 1/2=E 1/2(2nd)‐E 1/2(1st)). Values of ΔGdisp=12.5, 23.2, 23.2 and 7.7 kJ mol−1 follow for (3) ⋅+, (4) ⋅+, (5) ⋅+ and (6) ⋅+, respectively. Their presence could be proven by UV‐vis and EPR spectroscopy. In our experiments, the radical monocations were generated by mixing together the neutral and the twofold oxidized GFAs in equimolar ratios. Dioxygen has to be strictly avoided in these experiments, as it initiates rapid decomposition of the radical monocation. In the UV‐vis spectra, broad, intense bands appear in the visible region at high wavelengths. Figure 5a compares as an example the spectra recorded for neutral 7, the dication (7)2+ and a 1 : 1 mixture of 7 and (7)2+, containing the radical monocation (7) ⋅+. In the case of (7) ⋅+, band maxima at 386 and 580 nm (the latter with a shoulder at 540 nm, presumably the first member (0→1 excitation) of a vibrational progression) were measured. The monocations of the lower‐potential compounds show intense, broad bands at even higher wavelength (730 nm for (2) ⋅+ and 820 nm for (3) ⋅+), and the UV‐vis spectrum of (6) ⋅+ exhibits a relatively weak band at 475 nm. The monocations are not stable over a longer period in solution. The degradation was followed with UV‐vis spectroscopy (see Figure 5b and the Supporting Information). After ca. 10 h, half of the (7) ⋅+ molecules had decomposed. The other radical monocations decompose much faster, with at least half of the radical monocations being converted within 1 h in CH3CN (see Supporting Information).

Figure 5.

a) Comparison between the UV‐vis spectra (CH3CN solutions) of neutral 7, fully‐oxidized, dicationic (7)2+ and a 1 : 1 mixture of 7 and (7)2+, containing the radical monocationic (7) ⋅+. b) Degradation of the bands due to the radical monocation in CH3CN solution with time.

Next, the isotropic EPR spectra of the radical cations (1)+⋅, (2)+⋅, (3)+⋅, (6)+⋅, and (7)+⋅ in diluted CH2Cl2 solutions were recorded (using an X‐band EPR spectrometer from Magnettech MiniScope MS400, see Figure 6). Simulations of EPR spectra were performed with the MATLAB tool EasySpin 6.0.2. The simulated spectral parameters corresponding to the best fit to the experimental EPR spectra are summarized in Table 2. The hyperfine splitting (HFS) in the spectra of (1) ⋅+ and (7) ⋅+ is due to two groups of nitrogens (two equivalent nitrogens with large HFC constant of 5.6–6.0 G, and four equivalent nitrogens with smaller constant of 2.0 G), two protons at the central carbon ring, and 12 protons of four methyl groups from both guanidino moieties. The observance of HFC from 12 out of 24 methyl protons can be rationalized by the fact that only one methyl group of each NMe2 group is oriented toward the π‐system and can thus effectively conjunct with the SOMO. In the case of o‐diguanidino‐substituted aromatic cation‐radicals (3) ⋅+ and (6) ⋅+, the HFS constants on nitrogens are somewhat weaker (4.8–5.2 G and 1.8–1.9 G, respectively) than for the p‐diguanidino‐substituted compounds, and the additional HFC from the aromatic ring protons is not resolved. In the case of dimethoxy‐substituted (2) ⋅+, no visible HFS was observed even for a very dilute solution, which may be caused by the presence of a number of overlapping HFC due to guanidino methyl protons and protons of the methoxy groups and the coherence with natural spectral line width. The HFS of the spectra is in line with the π‐character of the SOMO, with delocalization of spin density mainly into the guanidino groups.

Figure 6.

Experimental (black curves) and simulated (red curves) X‐band EPR spectra of cation radicals a) (1) ⋅+, b) (6) ⋅+, c) (7) ⋅+, d) (2) ⋅+ and e) (3) ⋅+ (CH2Cl2, c=0.1 M, r.t.). The simulation parameters are given in Table 1.

Table 2.

The parameters (isotropic gi values and hyperfine coupling constants ai (in G) used to fit the isotropic EPR spectra of the radical cationic GFA molecules.

|

GFA |

gi |

ai(2 14N), G |

ai(4 14N), G |

ai(2 1H), G |

ai(12 1H), G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(1)+⋅ |

2.0017 |

5.58 |

2.00 |

0.65 |

0.32 |

|

(2)+⋅ |

2.0021 |

‐ |

‐ |

‐ |

‐ |

|

(3)+⋅ |

2.0018 |

4.84 |

1.87 |

‐ |

0.20 |

|

(6)+⋅ |

2.0026 |

5.17 |

1.92 |

‐ |

0.19 |

|

(7)+⋅ |

2.0022 |

6.04 |

1.99 |

0.35 |

0.15 |

The radical monocations were also calculated (B3LYP/def2‐TZVP). In Figure 7, the spin densities are plotted. The calculated gi values and hyperfine splitting parameters ai are in line with the experimental values (see caption to Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Plot of the spin density distributions (from B3LYP/def2‐TZVP calculations) for (1) ⋅+ and (7) ⋅+. Calculated values (hyperfine coupling constants only to nitrogen): gi=2.0031, ai(2 14N)=−5.59 G, ai(4 14N)=2.55 G for (1) ⋅+ and g=2.0037, ai(2 14N)=−5.67 G, ai(4 14N)=2.46 G for (7) ⋅+.

Synthesis and Characterization of the Reduced, Protonated Redox State

In the dehydrogenative coupling reactions detailed below in this work, the oxidized, dicationic redox state of the GFA molecule is converted into the reduced, diprotonated form (see general reactions in Scheme 1). Therefore, the reduced, diprotonated states were also characterized. We synthesized these compounds in CH3CN solution by reaction with slightly less than two equivalents of NH4PF6. The salts (2+2H)(PF6)2, (3+2H)(PF6)2, (4+2H)(PF6)2, (5+2H)(PF6)2, (6+2H)(PF6)2, and (7+2H)(PF6)2 were obtained in yields of 85 %, 52 %, 90 %, 67 %, 75 % and 70 %, respectively. Due to the high basicity of guanidines, the diprotonated form is stable in solution; no protonation equilibria were observed. Crystals suitable for structural chacaterization were obtained for (2+2H)(PF6)2, (5+2H)(PF6)2, (6+2H)(PF6)2 and (7+2H)(PF6)2. Figure 8 visualizes the structures, and selected structural parameters are collected in tables in the Supporting Information. Protonation leads to a characteristic elongation of the imino C=N double bonds, but as expected this elongation is smaller than upon oxidation. The 1H NMR shifts of the three forms differ slightly, e. g. the protons at the central C6 ring show at δ=6.60 ppm in neutral 7, 7.34 ppm in (7+2H)2+, and 7.26 ppm in (7)2+, allowing (in some cases) to follow PCET and dehydrogenative coupling reactions by NMR spectroscopy.

Figure 8.

Illustration of the solid‐state structures of the three salts (2+2H)(PF6)2, (5+2H)(PF6)2, (6+2H)(PF6)2 and (7+2H)(PF6)2 of the reduced, twofold protonated diguanidine molecules. Displacement ellipsoids drawn at the 50 % probability level. Colour code: N blue, O red, C grey, Cl light‐green, P orange, F dark‐green.

PCET Test Reactions and Quantum‐Chemical Calculations

To test the performance in PCET reactions, we first carried out some reactions on the NMR scale between a GFA molecule in its oxidized, dicationic redox state and another molecule in its reduced, twofold protonated state. A molecule, applied in its oxidized, dicationic form, that is reduced and protonated in the course of such a reaction, should be a more capable PCET reagent than its reaction partner. Scheme 6 illustrates such a PCET test reaction involving 1 and high‐potential 6. Reaction between (1+2H)(PF6)2 and 6(PF6)2 in acetonitrile gave only 11 % yield after 20 h at room temperature, but at 75 °C a yield of 96 % was reached within 26 h. This result indicates that 6 could indeed be a more potent PCET reagent than 1. Moreover, reactions between 1(PF6)2 and the protonated forms of the low‐potential GFA molecules (2+2H)(PF6)2 or (4+2H)(PF6)2 gave almost quantitative conversion (94 % after 3 h at 60 °C for (2+2H)(PF6)2, and 95 % after 12 h at 60 °C for (4+2H)(PF6)2). These results indicate that 1 outperforms the low‐potential GFA molecules 2 and 4 in PCET applications. In some cases, the estimation of the yield was hampered by the small differences in the NMR signals, e. g. in the reactions involving 1 and 7. In other cases, reactions proceed very slowly and/or stop at a certain stage, indicating that the PCET properties are comparable (see Supporting Information).

Scheme 6.

Example reaction between (6)2+ (applied as salt 6(PF6)2) and (1+2H)2+ (applied as salt (1+2H)(PF6)2) in acetonitrile, giving the two products (6+2H)2+ and (1)2+ in an NMR yield of 96 %. The result indicates that 6(PF6)2 is a more capable PCET reagent than 1(PF6)2.

We carried out some quantum‐chemical calculations (B3LYP/def2‐TZVP) to obtain more detailed information about the trends in the redox properties, the proton affinity and the PCET reactivity of these compounds. In these calculations, we focussed on 1 and the high‐potential molecules 6 and 7, that showed most promising results in the experimental studies. The counterions were included in our calculations of model PCET and ET reactions, since previous work indicated that this procedure leads to more reliable values. [41] Some results are summarized in Scheme 7 (see Supporting Information for further details). They show that the environment has a significant effect on the PCET reactivity. In the case of (2H+,2e−) transfer from (1+2H)(PF6)2 to 6(PF6)2, the Gibbs free energy is negative at ϵr=1 (isolated compound), indicating that 6(PF6)2 is a stronger PCET reagent than 1(PF6)2. However, at ϵr=37.5, the Gibbs free energy for the same reaction turns positive, indicating that now 1(PF6)2 outperforms 6(PF6)2. The calculations indicate that 7(PF6)2 is a slightly better PCET reagent than 1(PF6)2 at ϵr=1; (2H+,2e−) transfer from (1+2H)(PF6)2 to 7(PF6)2 is slightly exergonic (ΔG=‐6.6 kJ mol−1). However, with increasing value of the relative solvent permittivity ϵr, the difference between the reagents decreases.

Scheme 7.

Summary of some of the results of the quantum‐chemical calculations (B3LYP/def2‐TZVP) with (ϵr=37.5) and without (ϵr=1) COSMO.

In line with the experimental results, the calculations predict the ET reactions to be exergonic, and the numbers (Scheme 7) are in pleasing agreement with the values derived from the CV measurements (Scheme 4). From the numbers calculated for PT (Scheme 7, without consideration of environmental effects and counterions), it can be seen that the increase of the oxidation potential for 7 relative to 1 leads to a reduction of the Brønsted basicity. Therefore, the Gibbs free energy for PCET reaction between the two diguanidines is almost zero. In the case of reactions in which electron transfer is decisive for the reaction rate, 7(PF6)2 should be a more appropriate reagent than 1(PF6)2. (Please note the connection between thermodynamics and kinetics for (outer‐sphere) ET processes.) On the other hand, 1(PF6)2 is more appropriate if proton transfer is decisive for the reaction rate.

Dehydrogenative C−C and C−O Coupling Reactions

Having characterized the new redox‐active diguanidines in the relevant redox and protonated states, we tested the performance of 1 and the high‐potential reagents 6 and 7 in test dehydrogenative (C−C and C−O) coupling reactions. In all reactions, the compounds were applied in their oxidized form as salts 1(PF6)2, 6(PF6)2 and 7(PF6)2. Four different reactions were considered. In the first two reactions, coupling of 3,3‘‘,4,4‘‘‐tetramethoxy‐o‐terphenyl to give 2,3,10,11‐tetramethoxy‐triphenylene and N‐ethylcarbazole to give N,N‘‐diethyl‐3,3‘‐bicarbazole, electron transfer is likely to be the first step and contribute decisively to the overall reaction rate, since these substrates have a relatively low oxidation potential. In the last two reactions, oxidative lactonization of 2‐[(4‐methoxyphenyl)methyl]‐benzoic acid to give 3‐(4‐methoxyphenyl)‐1(3H)‐isobenzofuranone and coupling of naphthalene‐1,2‐dione to give [1,1′ binaphthalene]‐3,3′,4,4′‐tetraone, proton transfer plays a more prominent role for the overall reaction rate, since the two substrates exhibit a high oxidation potential. Therefore, these four reactions are appropriate to take into account different mechanistic pathways of dehydrogenative coupling reactions.

We start the discussion with the reaction of 3,3‘‘,4,4‘‘‐tetramethoxy‐o‐terphenyl with one of the three compounds 1(PF6)2, 6(PF6)2 or 7(PF6)2 to give the aryl‐aryl coupling product 2,3,10,11‐tetramethoxy‐triphenylene. The reactions were carried out first in the presence of one equivalent of HBF4⋅OEt2 (Scheme 8a). After 10 min reaction time at room temperature, the reaction was stopped by addition of aqueous saturated NHCO3 solution, and the product isolated after a work‐up procedure (see Supporting Information). To our delight, all reactions reached next to quantitative conversion within 10 min at room temperature. Next, we tested if reaction also proceeds without the addition of an acid (Scheme 8b). Obviously, the absence of an acid slows down the reaction; therefore the temperature was increased to 75 °C. Reaction with 7(PF6)2 turned out to give the best yield. After 20 h at 75 °C, a yield of 94 % was obtained. For comparison, reaction with 1(PF6)2 under similar conditions (44 h at 75 °C in acetonitrile) gave 92 % yield (see Supporting Information). It should be noted that this reaction could also be carried out with 2,3‐dichloro‐5,6‐dicyano‐1,4‐benzoquinone (DDQ), but then requires a huge amount of a strong acid (e. g. methanesulfonic acid in CH2Cl2 in a 1 : 9 v/v solvent mixture).[ 48 , 49 ] Alternatively, this reaction was carried out in high yield electrochemically, [50] or catalysed by multi‐walled carbon nanotubes with dioxygen as terminal oxidant. [51]

Scheme 8.

Reaction equations for the dehydrogenative C−C coupling of 3,3‘‘,4,4‘‘‐tetramethoxy‐o‐terphenyl to give 2,3,10,11‐tetramethoxy‐triphenylene. a) Reactions with addition of one equivalent of HBF4⋅Et2O at room temperature. b) Reaction without addition of HBF4⋅Et2O at 75 °C. A radical cation mechanism is followed, as sketched underneath.

For 3,3’’‐4,4’’‐tetramethoxy‐o‐terphenyl, an oxidation potential of +0.74 V vs. Fc+/Fc was measured. [32] One‐electron reduction of (7)2+ occurs at ca. −0.09 V. Hence, electron transfer between the two reactants requires ca. +0.83 V, translating into a Gibbs free energy change ΔG el for electron transfer of ca. 80 kJ mol−1. This is well within the assumed limit for conventional electron transfer at standard conditions (r.t., 1 bar) of 1 V (ca. 96.5 kJ mol−1). [52] Therefore, it is likely that an electron‐transfer equilibrium initiates the reaction (see also discussion in ref. [40] ); its equilibrium constant Kel being an important parameter for the overall rate constant. This also explains why 7(PF6)2 reacts faster than 1(PF6)2, since the latter has a lower reduction potential. Electron transfer requires 1.06 V or ΔGel≈102 kJ mol−1 in the case of 1(PF6)2. This value slightly exceeds the limit for electron transfer at r.t., explaining the need for a higher temperature of 75 °C in the acid‐free reactions.

Next, we inspected dehydrogenative coupling of N‐ethylcarbazole to give N,N‘‐diethyl‐3,3‘‐bicarbazole (Scheme 9). First, we tested the reaction of 7(PF6)2 with various quantities of HBF4⋅Et2O. A yield of 80 % after workup was obtained with 0.6 equivalents of HBF4⋅Et2O within 20 h at room temperature. With 1.0 equivalents of HBF4⋅Et2O, quantitative conversion is reached after 130 min at room temperature. Finally, with 1.5 equivalents of HBF4⋅Et2O, quantitative conversion with 7(PF6)2 was reached already after 60 min at room temperature. For comparison, the use of DDQ for this reaction requires a large excess of methanesulfonic acid (1 : 10 v/v methanesulfonic acid:CH2Cl2 solvent mixture). [53]

Scheme 9.

Dehydrogenative C−C coupling reaction of N‐ethylcarbazole to give N,N‘‐diethyl‐3,3‘‐bicarbazole.

Using the same conditions (1.5 equivalents of HBF4⋅Et2O and 60 min at room temperature), a yield of 67 % was obtained with 1(PF6)2, and a yield of 75 % with 6(PF6)2. An E 1/2 value of +1.12 V vs. SCE [54] (+0.66 V vs. Fc+/Fc) was measured for N‐ethylcarbazole, a value slightly lower than that for 3,3‘‘,4,4‘‘‐tetramethoxy‐o‐terphenyl. Therefore, reaction is again likely to be initiated by an electron‐transfer equilibirum, in line with the superior performance of 7(PF6)2, the reagent with the highest reduction potential. A radical cation (electron transfer) mechanism was also suggested for the oxidative coupling of carbazoles with DDQ or chloranil, [53] and initial electron transfer is also postulated as the first step in the electrochemical dimerization/polymerization of carbazole [55] and pyrrole. [56]

As detailed in the Supporting Information, the water‐soluble, protonated diguanidine by‐product could easily be removed from the N,N‘‐diethyl‐3,3‘‐bicarbazole product The extraction of a CH2Cl2 solution with water leads to the pure product, without diminishing the yield significantly.

Next we analysed the oxidative lactonization of 2‐[(4‐methoxyphenyl)methyl]‐benzoic acid (Scheme 10). This reaction was previously carried out with the help of tetrachloro‐o‐benzoquinone (o‐chloranil), but the presence of an additive was necessary.[ 57 , 58 ] Quantitative yield of the C−O coupling product was obtained with all three GFA reagents 1(PF6)2, 6(PF6)2 or 7(PF6)2, without addition of an additive. All reactions were carried out at room temperature with 1.25 equivalents of HBF4⋅Et2O. Fastest reaction was observed with 6(PF6)2; quantitative conversion was reached within 40 min at room temperature. Reaction with 1(PF6)2 was only slightly slower; 60 min reaction time were necessary for quantitative yield. The reaction with 7(PF6)2 proceeded slowest; 240 min reaction time were necessary for quantitative conversion. This trend is illustrated by the conversion vs. time plots in Figure 9. In difference to the previous two reactions, oxidative lactonization is unlikely to be initiated by electron transfer (too high substrate redox potential), and proton transfer becomes more important. According to Scheme 6, 6 and 1 are stronger Brønsted bases than 7, in line with their better performance in this reaction.

Scheme 10.

Oxidative lactonization of 2‐[(4‐methoxyphenyl)methyl]‐benzoic acid to give 3‐(4‐methoxyphenyl)‐1(3H)‐isobenzofuranone.

Figure 9.

Comparison between the conversion vs. reaction time plots for the oxidative lactonization of 2‐[(4‐methoxyphenyl)methyl]‐benzoic acid (Scheme 8) with 1(PF6)2, 6(PF6)2 or 7(PF6)2.

Finally, we tested oxidative coupling of naphthalene‐1,2‐dione to the [1,1′ binaphthalene]‐3,3′,4,4′‐tetraone (Scheme 11). This reaction was previously carried out with 2,3‐dichloro‐5,6‐dicyano‐1,4‐benzoquinone (DDQ) as oxidant under acidic conditions, [59] but redox‐active guanidines were not yet tested in this reaction. We carried out the reaction under similar conditions with 1(PF6)2 or 7(PF6)2 in place for DDQ. With 1(PF6)2 and 7(PF6)2, quantitative yield was reached already after 2 h at 0 °C. A large excess of a strong acid (70 eq. of methansulfonic acid) is needed; control experiments showed that no reaction takes place in the absence of acid. We skaled up this reaction by a factor of more than 10, and again obtained quantiative yield (after 4 h at 0 °C). Also here, reaction is unlikely to be initiated by an electron transfer equilibrium, since the oxidation potential of naphthalene‐1,2‐dione is too high. The need to apply a particularly large excess of a strong acid is in line with an proton transfer (arenium‐ion like) mechanism, as sketched in Scheme 11.

Scheme 11.

Dehydrogenative C−C coupling of naphthalene‐1,2‐dione to give [1,1′ binaphthalene]‐3,3′,4,4′‐tetraone, and suggestion concerning the mechanism.

Conclusions

Following a systematic approach, we develop new redox‐active guanidines for use in dehydrogenative coupling (DC) reactions. In these reactions, the redox‐active guanidines are applied in their oxidized, dicationic redox states. The strong Brønsted basicity of the redox‐active guanidines in their neutral, reduced redox states and the restoration of the aromatic system upon reduction of the dicationic, oxidized forms contribute to the driving force of these reactions. First, several new diguanidine compounds with relatively high redox potential were synthesized and characterized in all relevant redox and protonation states. In the course of our studies, we also characterized the radical monocationic redox states. Their lifetimes are estimated from UV‐vis experiments. Detailed EPR studies in combination with quantum‐chemical calculations show that the spin density is delocalized to a large extent into the guanidino groups. Then, the performance in proton‐coupled electron transfer (PCET) was compared in test reactions. In combination with quantum‐chemical calculations, the results of these experiments lead to a selection of molecules that show the best performance in DC reactions, namely 1(PF6)2, 6(PF6)2 and 7(PF6)2. 7(PF6)2 exhibits a higher reduction potential than 1(PF6)2 and 6(PF6)2, but 7 is a weaker Brønsted base than 1 and 2. With this selection of reagents, four different DC reactions were carried out. In the case of substrates with a relatively low redox potential for oxidation, reactions are initiated by an electron‐transfer equilibrium. The equilibrium constant then enters into the equation for the overall reaction rate, explaining why 1(PF6)2 reacts slower than 7(PF6)2 and 6(PF6)2. On the other hand, for substrates with high redox potential (with E ox higher than ca. +0.85 V), proton (or hydrogen atom) transfer becomes rate‐determinig, and 7(PF6)2 reacts slower than 1(PF6)2 and 6(PF6)2. The results of this work give a practical guide on how to chose the best reagent for a DC reaction.

Obviously, the use of redox‐active guanidines on a larger (industrial) scale requires the development of synthetic protocols for their green oxidation to the dicationic redox state. In this context, it is worth mentioning that diprotonated 1,2,4,5‐tetraguanidino‐benzene molecules could be efficiently oxidized with dioxygen (air) in the presence of a copper catalyst. [35] Besides chemical oxidation with cheap, readily available oxidants, electrochemical oxidation might represent a useful method. Despite of the remaining challenges, redox‐active diguanidines emerge as a class of reagents for DC reactions that are valuable, and often superior alternatives to traditionally used, toxic benzoquinones such as DDQ. The water‐soluble protonated diguanidine by‐product could easily be separated from the product by extraction.

Experimental Section

The synthetic details and analytical data for all compounds as well as the details of the quantum chemical (DFT) calculations are included in the Supporting Information. Deposition Numbers 2372995 (for 5), 2372989 (for 6), 2372994 (for 7), 2372988 (for (2+2H)(PF6)2), 2372986 (for (4+2H)(PF6)2), 2372996 (for (5+2H)(PF6)2), 2372990 (for (6+2H)(PF6)2), 2372993 (for (7+2H)(PF6)2), 2372991 (for [(6)Ag(CH3CN)2]PF6), 2372987 (for 2(PF6)2), 2372992 (for 6(PF6)2), and 2372997 (for 7(PF6)2) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by the joint Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe Access Structures service.

Supporting Information Summary

The authors have cited additional references within the Supporting Information.[ 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 ]

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

1.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support by the German Research Foundation (DFG). The authors acknowledge support by the state of Baden‐Württemberg through bwHPC and the German Research Foundation (DFG) through grant no INST 40/575‐1 FUGG (JUSTUS 2 cluster). Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Walter P., Schulz M., Hübner O., Poddelskii A., Kaifer E., Himmel H.-J., Chem. Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202402917. 10.1002/chem.202402917

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

References

- 1. Ohmatsu K., Ooi T., Nat. Synth. 2023, 2, 209–216. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yang Z., Shi W., Alhumade H., Yi H., Lei A., Nat. Synth. 2023, 2, 217–230. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tian T., Li Z., Li C.-J., Green Chem. 2021, 23, 6789–6862. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Batra A., Singh K. N., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 6676–6703. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Parvatkar P. T., Manetsch R., Banik B. K., Chem. Asian J. 2019, 14, 6–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tang S., Liu Y., Lei A., Chem 2018, 4, 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Girard S. A., Knauber T., Li C.-J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 74–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grzybowski M., Skonieczny K., Butenschön H., Gryko D. T., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 9900–9930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang C., Tang C., Jiao N., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3464–3484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hirano K., Miura M., Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 10704–10714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Song G., Wang F., Li X., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3651–3678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Scheuermann C. J., Chem. Asian J. 2010, 5, 436–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu C., Zhang H., Shi W., Lei A., Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 1780–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li C.-J., Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 335–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Beccalli E. M., Broggini G., Martinelli M., Sottocornola S., Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 5318–5365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yang Z., Shi W., Alhumade H., Yi H., Lei A., Nat. Synth. 2023, 2, 217–230. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Röckl J. L., Pollok D., Franke R., Waldvogel S. R., Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 45–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yuan Y., Lei A., Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 3309–3324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huynh M. H. V., Meyer T. J., Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 5004–5064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weinberg D. R., Gagliardi C. J., Hull J. F., Murphy C. F., Kent C. A., Westlake B. C., Paul A., Ess D. H., McCafferty D. G., Meyer T. J., Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 4016–4093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Reece S. Y., Nocera D. G., Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009. 78, 673–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Migliore A., Polizzi N. F., Therien M. J., Beratan D. N., Chem. Rev. 2014, 114(7), 3381–3465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pannwitz A., Wenger O. S., Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 4004–4014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wenger O. S., Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 11692–11702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wenger O. S., Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 1517–1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wenger O. S., Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 282–283, 150–158. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pannwitz A., Wenger O. S., Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 5861–5868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gentry E. C., Knowles R. R., Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 1546–1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Solórzano P. C., Baumgartner M. T., Puiatti M., Jimenez L. B., RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 21974–21985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Reinhard D., Schuldt M. P., Elbert S. M., Ueberricke L., Hengefeld K., Rominger F., Mastalerz M., Chem. Eur. J. 2024, e202402821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wild U., Federle S., Wagner A., Kaifer E., Himmel H.-J., Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 11971–11976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wild U., Hübner O., Himmel H.-J., Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 15988–15992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Himmel H.-J., Synlett 2018, 29, 1957–1977. [Google Scholar]

- 34.U. Wild, O. Hübner, L. Greb, M. Enders, E. Kaifer, H.-J. Himmel, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 5910–5915.

- 35. Wild U., Schön F., Himmel H.-J., Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 16630–16633; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 16410–16413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Raczyńska E. D., Maria P.-C., Gal J.-F., Decouzon M., J. Phys. Org. Chem. 1994, 7, 725–733. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Eckert-Maksić M., Glasovac Z., Trošelj P., Kütt A., Rodima T., Koppel I., Koppel I. A., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 5176–5184. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Superbases for Organic Synthesis (Ed: T. Ishikawa), John Wiley & Sons 2009.

- 39. Dardonville C., Caine B. A., de la Fuente M. N., Herranz G. M., Mariblanca B. C., Popelier P. L. A., New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 11016–11028. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wild U., Walter P., Hübner O., Kaifer E., Himmel H.-J., Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 16504–16513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Walter P., Hübner O., Kaifer E., Himmel H.-J., Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 11943–11956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Huynh M. T., Anson C. W., Cavell A. C., Stahl S. S., Hammes-Schiffer S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 15903–15910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Agarwal R. G., Coste S. C., Groff B. D., Heuer A. M., Noh H., Parada G. A., Wise C. F., Nichols E. M., Warren J. J., Mayer J. M., Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Warren J. J., Tronic T. A., Mayer J. M., Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6961–7001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.J. Osterbrink, F. Dos Santos, E. Kaifer, H.-J. Himmel, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2024, e202400070 (1–11).

- 46. Lohmeyer L., Kaifer E., Himmel H.-J., Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 8440–8454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hornung J., Hübner O., Kaifer E., Himmel H.-J., RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 39323–39329. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhai L., Shukla R., Rathore R., Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3474–3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhai L., Shukla R., Wadumethrige S. H., Rathore R., J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 4748–4760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wang W.-Z., Wang Q., He X., Shen Y.-H., Zhai Z., Zhang R., Li Y., Ye K.-Y., Org. Lett. 2024, 26, 2243–2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wirtanen T., Aikonen S., Muuronen M., Melchionna M., Kernell M., Davodi F., Kallio T., Hu T., Helaja J., Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 12288–12293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cheng J.-P., Lu Y., Zhu X., Mu L., J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 6108–6114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mallick S., Maddala S., Kollimalayan K., Venkatakrishnan P., J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 73–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ambrose J. F., Nelson R. F., J. Electrochem. Soc. 1968, 115, 1159–1164. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Li M., Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 1142–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sadki S., Schottland P., Brodie N., Sabouraud G., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2000, 29, 283–293. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Turek A. K., Hardee D. J., Ulman A. M., Nocera D. G., Jacobsen E. N., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 539–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Maskey R., Bendel C., Malzacher J., Greb L., Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 17386–17389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hahn S., Butscher J., An Q., Jocic A., Tverskoy O., Richter M., Feng X., Rominger F., Vaynzof Y., Bunz U. H. F., Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 7285–7291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.TURBOMOLE V7.7 2022, a development of University of Karlsruhe and Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe GmbH, 1989–2007, TURBOMOLE GmbH, since 2007; available from http://www.turbomole.org.

- 61. Balasubramani S. G., Chen G. P., Coriani S., Diedenhofen M., Frank M. S., Franzke Y. J., Furche F., Grotjahn R., Harding M. E., Hättig C., Hellweg A., Helmich-Paris B., Holzer C., Huniar U., Kaupp M., Marefat Khah A., Karbalaei Khani S., Müller T., Mack F., Nguyen B. D., Parker S. M., Perlt E., Rappoport D., Reiter K., Roy S., Rückert M., Schmitz G., Sierka M., Tapavicza E., Tew D. P., van Wüllen C., Voora V. K., Weigend F., Wodyński A., Yu J. M., J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 184107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Treutler O., Ahlrichs R., J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 102, 346–354. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Becke A. D., J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Stephens P. J., Devlin F. J., Chabalowski C. F., Frisch M. J., J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 11623–11627. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Weigend F., Ahlrichs R., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Eichkorn K., Treutler O., Öhm H., Häser M., Ahlrichs R., Chem. Phys. Lett. 1995, 242, 652–660. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Weigend F., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 1057–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Grimme S., Antony J., Ehrlich S., Krieg H., J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Grimme S., Ehrlich S., Goerigk L., J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.