Abstract

Background

In Canada, academic hospitals are the principal drivers of research and medical education, while community hospitals provide patient care to a majority of the population. Benefits of increasing community hospital research include improved patient outcomes and access to research, enhanced staff satisfaction and retention and increased research efficiency and generalizability. While the resources required to build Canadian community hospital research capacity have been identified, strategies for strengthening organizational research culture in these settings are not well defined. This study aimed to understand how research culture is experienced and shaped in Canadian community hospitals to provide strategies for strengthening research culture in these settings.

Methods

This qualitative descriptive study, as part of a larger study, explored the underlying dimensions of research culture. Participants were purposefully sampled and included healthcare providers, research staff or hospital administrators from community hospitals across Canada, with non-existent, emerging or established research programs. Data were collected via virtual semi-structured interviews and a demographic questionnaire. Interview transcripts were analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis and Schein’s Model of Organizational Culture as a sensitizing framework. Demographic data were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results

A total of 38 participants from 20 Canadian community hospitals described their experiences of research culture illustrating three key themes. As community hospital research programs matured, participants described a shift in research culture whereby research became more embedded in “the way things are done” within the community hospital. Recommended strategies to achieve an embedded culture of research involve: communications; relationship building; mentorship, training and education opportunities; selecting locally relevant studies; and systems-level support. A top-down approach to embedding research culture was contrasted with a bottom-up approach.

Conclusions

This study described the underlying dimensions of community hospital research culture and targeted strategies for strengthening research culture at different levels of research program maturity. Community hospitals without pre-existing research infrastructure were able to foster a culture of research from the bottom-up by emphasizing the value of embedding research in clinical practice. Although challenging, fostering a culture of research from the bottom-up may be necessary to propel research forward and initiate the process to build research capacity within a community hospital.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12961-024-01243-2.

Keywords: Organizational culture, Community hospitals, Critical care, Research culture, Research capacity

Background

Canadian hospitals are classified as academic (teaching) or community (non-teaching) hospitals [1]. Academic hospitals are those with a significant research and medical education mandate, whereas the primary focus of community hospitals is the provision of patient care, without formal mandates to engage in research [2, 3]. Although community hospitals account for 90% of the 602 hospitals in the country [1], almost all health research is conducted in academic hospitals, which are primarily located in urban areas [3, 4]. The unequal distribution of research activities across academic and community hospitals leads to inequitable patient access to participate in research studies, reduced research efficiency and decreased generalizability of research results [3, 5–8]. The benefits of including more community hospitals in research are numerous: increased patient access to novel therapies; improved study recruitment, retention and generalizability of clinical study results; expedited knowledge translation and development of evidence-based care standards; better patient outcomes; enhanced staff satisfaction and retention; and opportunities for new revenue streams for the hospital [3, 5, 7].

Recognizing the need to engage more community hospitals in research, previous work has identified and describe common factors that influence Canadian community hospital research participation [3, 5, 9–11]. Common barriers include insufficient funding, a lack of research experience amongst staff and limited organizational commitment to research [3, 5, 9–11]. Suggested strategies to improve community hospital research engagement include gaining dedicated external funding, developing supportive policies and infrastructure, forming collaborative partnerships, providing opportunities for training and mentorship and securing organizational commitment [3, 5, 9–14]. These strategies provide a useful foundation for understanding the research infrastructure (physical resources and people) required to strengthen research capacity; however, community hospitals’ leadership, healthcare professionals and patients/families may not recognize the value of investing in research infrastructure, an important foundation for establishing a positive research environment [15].

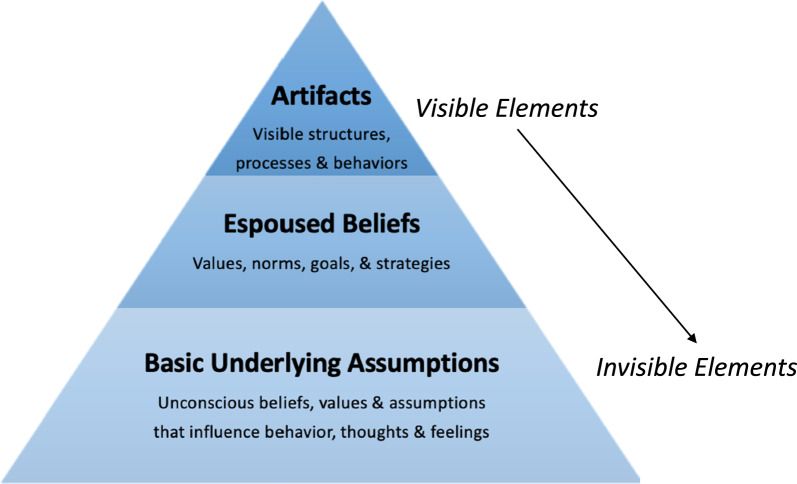

In a healthcare context, organizational culture is broadly defined as the shared ways of thinking, feeling and behaving in healthcare organizations [16]. This definition, informed by the work of Schein, is grounded in a conceptualization of culture on the basis of three levels of “observability”: (1) visible structures, processes and behaviours associated with an organization’s culture; (2) beliefs and values shared by individuals within the organization; and (3) underlying assumptions that influence behaviours, thoughts and feelings involved in the previous two levels (Fig. 1) [17]. With respect to research culture, these factors influence whether research is valued and the creation of enabling environments [15]. A positive research culture, defined as an environment that values and supports the implementation of research, is critical for building research capacity and increasing research performance [12, 15, 18]. Yet, strategies for strengthening organizational research culture in the context of Canadian community hospitals are not well reported. Lamontagne and colleagues note that research in Canada is often viewed as separate from clinical practice [14]. This is particularly true in most community hospitals, where research is not considered a priority and basic research infrastructure does not exist. Therefore, there is a need to bridge the gap between clinical research and healthcare delivery [14].

Fig. 1.

Schein’s model of organizational culture, adapted from Schein and Schein [17]

This qualitative descriptive study was part of a larger qualitative project focussed on examining the factors that influence Canadian community intensive care unit (ICU) research participation and the ability of community ICUs to implement and sustain a research program [19]. During concurrent data collection and analysis, research culture was identified as an emergent theme essential to implementing and sustaining a community hospital research program. The depth of information arising regarding research culture provided a set of data for the current study to conduct a deeper analysis of this phenomenon. This study aimed to understand: (a) how research culture is experienced by healthcare providers, research staff and hospital administrators in Canadian community hospitals and (b) participants’ recommended strategies for developing and strengthening research culture in this context.

Methods

Study design and theoretical framework

This study was guided by the principles of qualitative description. Qualitative description seeks to describe a phenomenon on the basis of participants’ experiences through literal description and by interpreting the meaning participants ascribe to their experiences [20–22]. This approach aligns with a relativist ontology, acknowledging that reality is subjective and can differ amongst participants [20]. Studying organizational culture from this perspective focusses on how participants understand their experiences and how their perceptions relate to their behaviours [23]. Qualitative descriptive studies may begin with a theory of the target phenomenon to guide data analysis and ensure in-depth understanding, without the requirement to stay within this theory [21]. In response, Schein’s Model of Organizational Culture was employed as a theoretical framework to guide data analysis (Fig. 1) [17]. As previously described, Schein conceptualizes culture on the basis of three levels of observability, considering the “visible” or “tangible” elements of an organization’s culture as well as the “invisible” or “non-tangible” elements [17]. These principles make Schein’s model ideal for interpreting the deeper, underlying components of culture, which helped to ensure that participants’ perceptions of research culture were described holistically.

Sampling and recruitment

The purposeful sample in this study consisted of individuals who, through either a clinical, research or administrative role, were knowledgeable about or were interested in Canadian community hospital research programs. Study participants were required to work in a publicly funded Canadian community (non-teaching) hospital (as classified by the Canadian Institute for Health Information [1]) and belonged to one of three professional groupings: (1) healthcare professionals working in critical care (including physicians, registered nurses and allied health professionals); (2) research staff (including research volunteers, research assistants, research coordinators and research managers); and (3) community hospital administrators (including senior executives, directors and managers). Maximum variation sampling [24] was employed to include individuals from community hospitals with different levels of research program maturity (i.e., individuals from community hospitals with self-reported “non-existent”, “emerging” and “established” research programs). Recruitment strategies included: study poster dissemination via social media and in-person conferences, distributing letters through professional networks, contacting participants from a previous survey [10] and snowball sampling [25]. Sample size was determined on the basis of the research team’s ability to meaningfully answer the research question, feasibility of recruitment and response to recruitment efforts, and the relative frequency of the phenomenon of interest [20, 26, 27].

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted between April 2022 until May 2023 by one or a combination of two members of the research team (P.G., K.R., M.L.). Efforts were made to ensure that interviewers who conducted the interviews did not have pre-existing relationships with the participants. The interview guide was piloted with one of the researcher’s (P.G.) colleagues to determine estimated length of interview and order and clarity of questions. Revisions of the interview guide were made to optimize the order of questions, facilitate flow and add additional prompts to solicit further exploration of study concepts. The finalized semi-structured interview guide was considered flexible to allow for emerging concepts to be explored (Additional File 1). Interviews were conducted virtually using a videoconferencing platform (n = 33) or by telephone (n = 5), and were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and de-identified by a professional medical transcriptionist. Interviews were 17–92 (mean 39) min in length and focussed on exploring participants’ experience with and interest and motivation to conduct research within a community hospital setting, as well as potential strategies to improve community hospital research engagement and participation. Participants were also asked to describe the culture of research in their organization, followed by open-ended questions about how to improve it. Prior to each interview, participant demographic data were collected via an online survey.

Data analysis

Demographic data was analysed using descriptive statistics and interview data were analysed following Braun and Clarke’s six steps to reflexive thematic analysis [28]. First, one member of the research team (K.R.) read the transcripts (n = 38) with the current study objectives in mind to become deeply immersed in the data. The same research team member coded the transcripts, beginning with those from community hospital administrators (n = 5), followed by those from research staff (n = 10) then healthcare providers (n = 23). Transcripts were coded inductively to label codes unique to the data, as well as deductively using Schein’s model as a sensitizing framework to ensure the components of research culture (i.e. artefacts, beliefs and values, underlying assumptions) were being interpreted holistically. Transcripts were coded using a qualitative data management software, Dedoose version 9.0.17. [29] to improve coding efficiency and organization of the coded data. Coded transcripts were compared on the basis of participant role (i.e. healthcare provider, research staff, hospital administrator) and self-reported level of research program maturity (i.e. non-existent, emerging, established) to identify potential divergent codes and themes. Two members of the research team (K.R., M.L.) reviewed the list of codes and organized them into themes that captured the research questions [30], and five members of the research team (K.R., M.L., K.H., D.P., J.T.) participated in refining and naming the themes, which involved checking the coded data to ensure the analysis was true to transcripts, that there were clear boundaries between themes, that the themes addressed the research questions and that the presentation of findings were coherent [30]. Theme names were identified inductively to capture the essence of each theme [28]. The final stage of data analysis involved editing and compiling analytic notes and memos that were iteratively developed throughout the data collection and analysis process [30].

Rigour and trustworthiness

This study was reported in accordance with the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) guidelines (Additional File 2) [31]. In qualitative research, credibility can be achieved through researcher reflexivity, peer review and triangulation [32]. The primary analyst (K.R.) maintained reflexivity throughout the research process by keeping detailed field notes of their interpretations, coding decisions and concept formations. These notes acted as an audit trail, which was a useful strategy to manage concepts, verify reflexive decisions and ensure reliability/consistency [32, 33]. Triangulation of data [32] was also employed to compare reflexive field notes and memos to the coded transcripts. Lastly, peer-debriefing was employed to confirm clarity in concept development during the data analysis and manuscript writing stages [33]. Researcher reflexivity is reported in Additional File 3.

Results

Participants

Participants included 38 community hospital professionals from 20 different community hospitals across 6 Canadian provinces; two individuals consented to participate but did not complete the interview and one individual completed the consent but was subsequently noted to be working in an academic hospital. Participant demographic information is summarized in Additional File 4.

Key themes

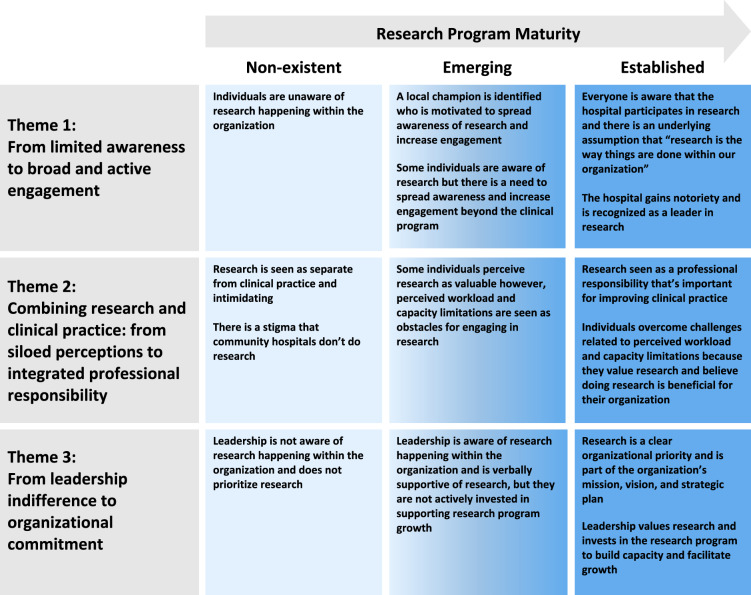

Aligning with the first objective of this analysis, participants described their perceptions of research culture illustrating three key themes: (1) from limited awareness to broad and active engagement, (2) combining research and clinical practice: from siloed perceptions to integrated professional responsibility and (3) from leadership indifference to organizational commitment. While no divergent themes were detected between participants’ professional roles, participants described differing experiences of research culture on the basis of self-reported level of community hospital research program maturity. Compared with participants from organizations with “non-existent” or “emerging” research programs, participants from organizations with more “established” research programs reported a more positive research culture, whereby research became more embedded in the organizational culture. To capture the shift in participants’ perceptions of research culture, each theme was divided into three subthemes aligning with the three levels of research program maturity. A description of the three key themes and associated subthemes are provided below, accompanied by key illustrative quotes. Descriptions of research culture within each theme included the current experiences of participants at that research program maturity level and the past experiences of participants whose research programs had previously passed through that same maturity level. There was alignment between current and past experiences of participants, thereby confirming the descriptions of each theme. Figure 2 provides a summary of how research culture evolved as community hospital research programs matured.

Fig. 2.

Experiences of research culture based on level of research program maturity

Theme 1: from limited awareness to broad and active engagement

Participants from community hospitals with “non-existent”, “emerging” and “established” research programs described varying levels of awareness and engagement in research amongst clinical and research staff and members of the community. As research programs increase in maturity, this theme describes the process of spreading awareness of and increasing engagement in research across the community hospital and the community it serves to embed a culture of research.

Non-existent – No line of sight

In community hospitals with a “non-existent” research program, participants were unaware of research happening within the organization or of opportunities to engage in research. Participants from community hospitals with “non-existent” research programs noted that research was not widely discussed within their organizations, describing research as not “a blip on the radar” (P25, nurse) or “in people’s line of sight” (P3, nurse). As one participant summarized, at this level: “people aren’t aware of the research that’s happening within [their own community hospital] and there’s [not] even an opportunity to participate or to pursue an interest in the research question … ‘cause they don’t know who can mentor them, who can support them, or how to go about it” (P20, hospital administrator).

Emerging – Key champions pushing the charge

In community hospitals with “emerging” research programs, participants reported that only a few individuals within the organization were aware of ongoing research activities and were interested in engaging in research. At this stage, organizations typically had at least one “local champion” who was actively involved in spreading awareness of ongoing research and in increasing staff engagement within the unit and across the organization. Local champions are described as motivated, persistent, engaging, supportive, trusting and passionate individuals dedicated to starting and growing a research program even in the face of limited financial or organizational resources. For example, one participant from a community hospital with an “established” research program reflected:

I mean, [Doctor X] has, obviously, been the linchpin in moving our research program forward…She advocated for the funding. She worked tirelessly to bring on the funding and get the right people at the table, advocating for the program. She really rallied the staff… she had staff coming in on their time off to do data collection and things like that so, she really engaged the staff. I think, without [Doctor X], that program would be nowhere near where it is today (P19, hospital administrator).

Champions were also described as having a sense of ownership and pride in developing the research program by dedicating their own time and resources, often working extra hours in addition to their clinical responsibilities and making personal sacrifices to build and support the research program in their community hospitals because they believed it benefits the entire organization. Their commitment to improving the organization motivated other individuals to also engage in research. Reflecting on the characteristics of a champion within their organization, one participant from a community hospital with an “emerging” research program shared:

She just had this kind of… ambition… to kind of make this hospital bigger and better than, maybe, she thought it was or that it, maybe, was perceived in the community…Her big attribute is she just…she had this engaging nature… she just wanted to kind of make this hospital better (P8, research coordinator).

Participants highlighted the importance of identifying at least one individual who is “driving the bus and really working hard to make sure that this happens” (P41, physician). However, not everyone was interested in being a champion. As one participant expressed, “it takes up a lot of my time and I don’t have the time or the inclination to be the person that is going to try to break through the research barriers … I just prefer to do my thing and try to stumble along” (P32, physician). While not everyone is interested in leading research activities, participants emphasized the importance of gaining staff support. Overtime, champions were able to spread awareness and gain support from a small group of “super users” (P13, hospital administrator) amongst the clinical staff who were interested in getting involved in research.

Established – The way we do things in our community hospital

In community hospitals with an “established” research program, everyone (including staff, patients, families and community members) was aware that the organization participates in research and was willing to support it. Once a culture of research was embedded in one unit, participants described the need to spread awareness and increase engagement across the rest of the organization. A participant from a community hospital with an established research program explained, “part of what we did to make research successful was getting it outside of the [unit] so that people within the hospital and within the community knew what we were doing” (P13, hospital administrator). Moreover, by spreading awareness and “creating [the] narrative” (P20, hospital administrator) that research is a part of the organization, there was the shared underlying assumption that research is “just the way we do things at [community hospital]” (P20, hospital administrator) and eventually, research became “the norm” (P19, hospital administrator) across the organization. Furthermore, by spreading awareness beyond the organization, participants explained that the community hospital gains “notoriety”, whereby “people are noticing and now realize that [community hospital] is an important player in [the research] space” (P20, hospital administrator). Recognizing the organization was becoming a leader in research helped to reinforce research as part of the organization’s narrative, thereby strengthening research culture.

Theme 2: combining research and clinical practice: from siloed perceptions to integrated professional responsibility

To achieve an embedded culture of research, participants explained that community hospital professionals need to value research and perceive it as important. Participants described the benefits of research in improving patient experiences and outcomes, informing evidenced-based standards and enhancing overall healthcare delivery. Yet, the degree to which research was prioritized differed on the basis of the level of research program maturity. As research programs increase in maturity, this theme describes a culture shift from thinking that research is separate from clinical practice and intimidating to addressing beliefs about perceived workload and capacity limitations and seeing research as a professional responsibility (Fig. 2).

Non-existent – Not really part of my job

According to participants from community hospitals with “non-existent” research programs, research was seen as a separate activity from clinical practice. One healthcare provider from a community hospital with a “non-existent” research program explained that “technically [research] is in our job description; we’re supposed to have 80% clinical and 20% allocated to both research and education”, however, “it’s not valued” (P2, nurse practitioner). Research was described as an “ivory tower” (P20, hospital administrator) that is removed from clinical responsibilities. This siloed perception of research was also associated with the “stigma” that “community hospitals can’t do research” (P3, nurse). A participant from a community hospital that did not have a research program explained, “there’s not really much awareness and much interest in thinking that this organization is able to actually conduct [research]” (P3, nurse). In addition, misconceptions about what research involves can make it seem intimidating, leading to thoughts that limit engagement such as “‘I’ve never done any research’, ‘I don’t know how to do research’, ‘it’s a little bit overwhelming’, ‘I don’t want to start’…” (P2, nurse practitioner).

Emerging – Important but hard to find the time and resources

In community hospitals with “emerging” research programs, some participants perceived research as valuable, while others did not. For example, a participant from a community hospital with an “emerging” research program reflected:

There’s a good chunk of the staff that are definitely really interested in best practice and wanting to learn more and do more. And then some people just don’t, maybe, see the value in it. Like, you'll always hear the odd comment for any of us that start a Master’s program or further education that the odd person will say, like, ‘Oh, it’s a waste of time. Like, I don’t know why you're bothering,’ like that kind of mentality. But then, probably the majority… would say that they would be receptive to research and a little more… open to having that implemented (P24, nurse).

Perceptions of capacity limitations also impacted research. Participants explained that staff were feeling “burnout”, “exhausted”, “stretched” and “overwhelmed.” As a result, they were resistant to taking on tasks in addition to their existing workload, especially if they did not perceive these activities as having any added value to their professional role. As one participant explained, “in that burnout frame of reference” staff think, “what's my motivating factor to actually participate?” (P2, nurse practitioner). Furthermore, capacity limitations (i.e. “a lack of resources”, no protected time, no dedicated staff, no funding) prevented interested professionals from engaging in research. For example, another participant explained, “in our organization, there’s a lot of interest on the physician side to bring research into the organization, [but] the problem is that we don’t have enough resources to actually sustain it” (P3, nurse).

Established – Professional duty

In community hospitals with “established” research programs, participants reported that research is valued as an important aspect of clinical practice. Participants were motivated to participate in research because they believed it was important for informing evidence-based practice and improving health service delivery. For some participants, research was described as a “professional duty”, even amidst stressful circumstances, such as the pandemic:

I mean, I think it’s, honestly, our responsibility. It’s something that I’ve always been involved with, and I think it’s really our responsibility, [it’s] best practice and, honestly, if you’re not trying to evolve best practice then you can’t really say it’s best practice. And so, I think there’s an inherent responsibility. I think there’s an opportunity… to continue to evolve… you know, in a pandemic scenario, we were all kind of stressed and looking for options. So, there was an inherent, holistic need to try to help, as well (P15, physician).

In response to resource limitations, participants often volunteered their time to help get their research programs started and looked for creative ways to obtain resources. When asked how they managed their clinical workload while building a research program, a participant from a community hospital with an “established” research program shared:

You know what, it was important to me. And I didn’t perceive it as workload. It was something that I was passionate about because … there was times that we could see the immediate benefits like [research study], [on] a patient experience and their care. But I also knew what we were doing was going to inevitably, improve the care of patients, long after I left nursing. So, it was just important for me and that was okay (P13, hospital administrator).

Participants explained that financial support and investment in infrastructure were necessary for program growth, sustainability and to “create winning conditions locally” (P39, physician). However, participants from community hospitals with “established” research programs did not feel that financial incentives were the primary motivating factors. As one participant explained, “it wasn’t just because of the money piece that drove us, but it was really an organizational culture… that we really wanted to do something worthwhile that we would free up that nurse that would do the [research] process” (P14, hospital administrator). In organizations with “established” research programs, research was valued and individuals were motivated to overcome challenges related to workload and are committed to engaging in research.

Theme 3: from leadership indifference to organizational commitment

Participants from community hospitals with “non-existent”, “emerging” and “established” research programs experienced varying levels of leadership support and organizational commitment to research. This theme describes the process of gaining support from community hospital administrators, the executive leadership team and the hospital board as well as securing organizational commitment for embedding a culture of research (Fig. 2).

Non-existent – Not interested

In community hospitals with “non-existent” research programs, participants perceived that hospital administrators and leadership were unaware of research happening within the organization and did not consider research a priority. One participant stated, “in our hospital, I think the CEO (Chief Executive Officer) probably isn’t even aware that we do this kind of stuff” (P32, physician). Additionally, they felt that hospital leadership was unaware of the benefits of research and did not view it as important. Notably, another participant described approaching their hospital leadership about research, but was met with resistance:

The one time I tried to approach the leadership about doing research – it was actually just for a quality improvement initiative… And I wanted to do some research and get some hard facts on paper, to kind of initiate further education for the nursing staff. And I did up a proposal using evidence, published evidence, about why we should do this, standards of practice, blah, blah, blah, and was just told, “No,” basically, “we’re doing okay. We don’t need you to do that” (P25, nurse).

Emerging – I’m interested but there’s no money for that

In community hospitals with “emerging” research programs, leadership was aware of research activities happening within the organization and sometimes verbally supportive, but typically not invested in formally supporting program growth. As one participant described:

I would say that they’re tolerant of us... they’re …philosophically supportive to us. They’re okay with what we’re doing. But they’re unable to dedicate resources and… money to us because they’re absolutely overcome with staffing issues and other concerns (P10, physician).

Participants felt that the hospital leadership needed to be more invested in the research program by adopting a “‘How can we help facilitate this?’ [role] and not just, you know, ‘Good job!’ when you do something” (P23, physician).

Established – Deliberate support

In community hospitals with “established” research programs, participants described leadership teams that valued research and invested in supporting research. When asked why research is important, one participant from a community hospital with an “established” research program shared:

… you know, the research that we’re doing is all about improving the patient experience from the lens of quality and safety and…that’s just so core to our purpose, our mission, as an organization… we talk about “everybody’s accountable for quality and safety” at [Community Hospital], so this should be the same about research. You know, that’s really my view and that’s why it kind of seems odd to me, sometimes, to talk about it because it just seems logical to me that everybody should be doing it (P20, hospital administrator).

Participants explained that when their leaders viewed research as important, the clinical team was willing to support it. As one participant noted, “the nurses in the unit almost mimic what [the] charge nurse’s feeling and attitude, or educator’s attitude towards the research. So, if they’re advocates for it, they’re okay…they’re good with it…then, usually, the rest of the staff is good, too” (P37, research coordinator).

When hospital leaders valued research, they demonstrated their support for research by actively facilitating growth. As one participant explained, “if there was a manager in the ICU who had no interest, didn’t see the value in research, who listened to some of the concerns from a workload perspective, it never would have gone anywhere” (P13, hospital administrator). Managers and department directors from established research programs explained that their role was to navigate challenges and reduce barriers, including those related to perceived workload and capacity limitations, as well as to facilitate the administrative tasks associated with new studies, and help with “getting the right players at the table” (P19, hospital administrator). The role of community hospital administrators at the executive leadership level was to encourage engagement which involved giving permission for protected time and helping staff to “think through, talk through, how they could… re-juggle their priorities to give them some space to get involved [in research]” (P20, hospital administrator). In addition to promoting engagement, hospital executives were responsible for advocating the importance of research to the community hospital board to make it an organizational priority.

Ultimately, community hospitals with “established” research programs displayed organizational commitment as shown by formalization of research efforts. Formalization starts with including research as part of the organization’s mission, vision and strategic plan. As one participant from a community hospital with an “established” research program explained, formalization is important because “otherwise, it was just kind of happening in the fringes. By chance, right? Now it’s more deliberate” (P20, hospital administrator). They added that when research is included in the vision, mission and strategic plan, it sets “the tone at the top” and “creates the blueprint” by which the program can be built from (P20, hospital administrator). Moreover, it signals that the entire organization values research. In making it a strategic priority, it also makes the organization accountable for directing resources towards the program. Eventually, formalization involves creating a dedicated research department or institute with formal appointments, “that speak to the commitment that the organization is making to research” (P20, hospital administrator). Overall, these activities highlighted that research is an organizational priority, creating a culture that values research and embeds it into practice.

Strategies for embedding a culture of research

With respect to strategies for strengthening research culture, participants described two high-level approaches to embedding research culture in community hospitals: top-down and bottom-up. A top-down approach involved gaining leadership support and formalizing research as an organizational priority at the outset of the culture-building process. One participant from a community hospital with an established research program described this process as follows:

…it’s interesting because… everything we’ve done is not so much directed towards ICU related research. I mean, I’m an intensivist and I work in the ICU but our approach has been one of a system-wide plan and not necessarily a department-wide strategy. So, we’ve decided to, like, not grow research out of one department and then let it spread, shall we say, “naturally” across the organization and have other departments, mimic or reproduce the success of one department or another. We’ve decided to start system-wide, hospital-wide, and then provide our services to everybody hoping that there’ll be one or two people in each department who would be research champions, seek us out, and get their, get their department involved, if you will, with their research ideas or questions (P22, physician).

Having top-down support was described as important. Some participants from hospitals with “non-existent” research programs explained that without top-down support, they were not able to initiate a research program. Despite this, only one participant from a hospital with an “established” research program (P22, physician) identified that their organization employed a top-down approach to starting their research program.

Conversely, most participants from community hospitals with “established” research programs described taking a bottom-up approach, whereby research was initiated by a local champion in one department and through the process of spreading awareness, increasing engagement, and promoting the value of research, they were able to gain leadership support and organizational commitment. One participant explained that the bottom-up approach involved “building infrastructure slowly” and as the program built momentum and demonstrated the importance of research, it led to “buy-in from upper heads [because] they have to see that it’s worth it to even give us this, right?” (P37, research coordinator). Nonetheless, participants from all levels of hospital research programs agreed that leadership support and organizational commitment were crucial for research program growth and to embed a culture of research across the organization.

In addition, participants also described specific strategies for strengthening research culture that addressed each of the key themes. These strategies include: communications; relationship building; mentorship, training and education; selecting locally relevant studies; and systems-level support (Table 1).

Table 1.

Strategies for embedding a culture of research

| Strategy | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Communications | Communication strategies must focus on spreading awareness of research and increasing engagement within the clinical program, across the organization and to patients and families in the community. |

- Talking about research in clinical program huddles - Sharing internal newsletters and emails with research updates - Hosting organization-wide research days - Engaging the community hospital’s communications or public affairs department to widely share research updates with patients, families and community members via social media and local news outlets |

| Communication strategies must also seek to destigmatize research and articulate why research is important. |

- “Languaging” research so that “it’s not about research with a ‘big R’” (P2, nurse practitioner) but rather, about finding ways to do things differently and improve patient care can help to decrease intimidation and promote the perspective that research is an important part of clinical practice - Explaining how research can benefit clinical practice |

|

| To secure buy-in from community hospital leadership, communication strategies need to demonstrate the value of research at an organizational level. |

- Sharing research updates with the executive team (e.g., monthly department meetings and grand rounds) - Securing external funding opportunities and notifying the leadership team - Disseminating the results of locally relevant studies that have visible impacts for improving healthcare delivery and efficiency within the organization - Sharing academic publications and conference presentations which increase the community hospital’s notoriety |

|

| Relationship building | Building relationships with staff across all levels of the organization helps to spread awareness, promote the value of research and secure buy-in from community hospital leadership. |

- Being in-person to talk to staff about ongoing projects and share the impact of research on clinical practice - Be available to answer staff questions |

| Mentorship, training and education | Providing mentorship, training and education opportunities increases awareness and engagement and promotes the value of research. Mentors can be existing champions within the organization, or they can be individuals identified through an academic institution or external professional networks. |

- Hosting journal clubs and lunch-and-learns - Attending conferences and professional networking opportunities - Utilizing the educational lead in the department to promote research |

| Selecting locally relevant studies | Selecting locally relevant studies can help to demonstrate the direct benefit of research for improving clinical practice. | - Choosing studies with topics that align with the interests of clinical staff or hospital leadership, or those that address a problem amongst a specific patient population that the community hospital serves |

| Formalization | Formalizing research helps to embed it into “the way things are done within the community hospital”. In this way, formalization is both a criterion for achieving an established culture of research and a strategy for strengthening research culture. |

- Creating policies and procedures that embed research into clinical practice - Including research in clinical job descriptions - Discussing research in hiring process - Making research a part of the community hospital’s mission, vision and strategic plan - Creating a formal research department or institute |

| Systems-level support | Participants identify the need for greater system-level support in strengthening community hospital research culture. Within this category, participants highlight the need for more support from provincial and federal governments, quality-reporting organizations, research funding agencies and academic institutions. |

- Invest in increasing community hospital research capacity at the provincial and federal levels - Include research as a quality indicator during accreditation processes - Create equitable funding opportunities for community hospitals by ensuring awards address the unique needs of community hospitals and focus on building sustainable research programs - Promote the value of research as an important part of clinical practice to trainees in undergraduate medical and nursing programs - Increase collaborations between academic institutions and community hospitals |

Discussion

This is the first study to explore how research culture is experienced in Canadian community hospitals. As community hospital research programs increased in maturity, a culture shift was identified across three key themes, whereby research became embedded as part of “the way things are done” within the community hospital. Strategies to build a positive research culture included spreading awareness and increasing engagement; promoting the value of research; securing leadership buy-in and organizational commitment; and addressing all organizational levels (i.e. individuals, units, the organization as a whole and the external community). Importantly, the process of strengthening research culture is non-linear and multifaceted in that organizations may experience positive gains in one area, such as awareness and engagement, but may need to improve in other areas, such as leadership support and organizational commitment.

Supporting current literature

The key themes and associated strategies highlighted in this study are supported by literature on building research culture and capacity in other healthcare settings. As the first theme emphasizes, spreading awareness of research and increasing engagement are crucial for building research culture and capacity [2, 34, 35]. To strengthen research culture, research needs to be seen as part of the community hospital’s “core business” [35–37] or “core mission” [38], aligning with the finding that research needs to be viewed as an integral part of “the way things are done” within the organization. Moreover, participants agree that research should be embedded in daily activities and engagement in research should be an expectation [37]. Recommendations from participants included integrating research into policies and procedures, including research in the organization’s mission, vision and strategic plan, and identifying research as a professional expectation during the hiring process. Additionally, research “champions” or leaders are essential for inspiring engagement and fostering a positive research culture [35, 39]. Jones and colleagues reported that engagement in research can take many forms such as conducting case studies, evaluating feasibility of study proposals or identifying how recent findings can be implemented into clinical practice [38]. As our findings highlight, while not all clinicians want to be active researchers, embedding a culture of research requires that everyone be supportive of research and engaged to create an environment that values evidence-based practice [38].

The second theme highlights the importance of recognizing the value of research as a means to inform evidence-based practice and improve care delivery, and consequently, embed a positive culture of research [15, 40, 41]. Our findings confirm that barriers to embedding a culture of research include the belief that research is separate from clinical practice [14], as well as misconceptions about what research is and how it is defined [34]. Additional barriers are perceived clinical workloads and a lack of time for research [36, 42]. As participants shared, when research is seen as extra work, it is not prioritized [43]. To address beliefs about competing workload and resource limitations, participants felt that strategies should focus on promoting the benefits of research in creating a learning health system and destigmatizing research by reframing it as a way to achieve organizational learning and improvement [43]. Importantly, participants emphasized that motivating staff to participate in research should focus on promoting value over financial incentives [38]. As our findings highlight, to demonstrate the value of research it needs to be close to clinical practice [44]. Research that is close to clinical practice, or “locally relevant” as participants described, is more likely to increase engagement and the results are more likely to be incorporated in clinical practice [40, 44].

As described in our third theme, community hospital leadership is influential in leading research culture change across the organization [2, 38]. Yet, in community hospitals without a positive research culture, hospital leaders, facing budgetary constraints, may prioritize budgets and patient care since “keeping the doors open [takes] precedence over attention to evidence” [34, p. 689]. Participants confirmed that securing buy-in from community hospital leadership facilitates organizational commitment, demonstrated by including research in the organization’s mission, vision and strategic objectives [36, 37, 40, 43]. These activities are essential for making research a core expectation [38] and setting an organizational direction for research [15]. Ultimately, formalizing a research commitment directs resources towards increasing research capacity and developing policies that embed research into practice, thereby strengthening research culture [39, 43].

Top-down and bottom-up approaches

The results of this study present two approaches to building community hospital research culture: top-down and bottom-up. The first is to foster a culture of research through a top-down approach, which involves setting research as an organizational priority and investing in research capacity at the onset of the research culture building process. The second is a bottom-up approach which, often initiated by a local champion within the organization, involves starting with small research projects that require minimal resources, raising awareness and gaining support from clinical staff to build momentum, demonstrating the value of research and eventually, securing organizational commitment and subsequently investing in research capacity. Organizations need both top-down and bottom-up support to foster and sustain research culture across the community hospital. However, our findings suggest that while top-down support may be perceived as ideal for facilitating rapid system-wide culture change, it may not be a realistic starting place for many Canadian community hospitals. Instead, efforts to build research capacity within community hospitals should start from the ground-up, led by motivated individuals who are driven to build research programs in their clinical units. For many community hospitals, this may be a necessary approach to initiate the process for fostering research culture, which subsequently leads to top-down support from the organization.

Artefacts, values and underlying assumptions

Building research capacity, defined as the ability for organizations to produce research, is essential for strengthening research culture and vice versa [45]. In the current study, this was illustrated by the finding that community hospitals with self-reported “established” research programs also described a more positive, embedded research culture compared with community hospitals with “non-existent” research programs. While existing frameworks present strategies for building research culture and capacity together, this study offers an in-depth focus on how to strengthen research culture using an organizational culture theory lens. Specifically, analysing research culture by considering the tangible and non-tangible aspects of culture depicted in Schein’s model [17, 46] helped to identify the underlying dimensions of research culture in Canadian community hospitals.

Aligning with the visible artefacts level in Schein’s model [17, 46], participants agreed that investing in physical research infrastructure and securing formal organizational commitment to research is essential for research program growth and sustainability [2, 39, 40, 44]. Some participants from community hospitals with “non-existent” research programs expressed that without dedicated funding, pre-existing infrastructure and organizational commitment, it is impossible to do research, even though it would be beneficial. While these are important artefacts of research culture, a number of community hospitals have built research programs under similar circumstances, led by passionate individuals who were motivated to advance the agenda that research should be seen as an organizational priority. Hence, aligning with the espoused beliefs and values level in Schein’s model [17, 46], to achieve an embedded culture of research, individuals within the organization need to value research as important for improving clinical practice and health service delivery. Some frameworks highlight the importance of promoting research as beneficial and valuable [40, 44]. However, to overcome perceived capacity and resource limitations, participants identified that individuals from community hospitals need to hold the deeper underlying assumption that they have a professional duty to conduct research because it is beneficial for their patients, organizations and communities. The identification of these underlying assumptions associated with research culture, as depicted in the third-level of Schein’s model [17, 46], contributes a new layer of “observability” to current literature focussed on improving community hospital research culture. Overall, strategies to increase research engagement in community hospital settings should consider all three levels, with a particular focus on addressing the underlying values and assumptions that shape research culture.

Future directions

The current study was focussed on describing participants’ perceptions of community hospital research culture and strategies to improve it at the individual, unit and organizational levels. However, beyond the organization, participants emphasized the need for greater systems-level supports from governments, research funding agencies and academic institutions to build research capacity and culture [3, 9, 14]. Bowen and colleagues also identified the need for system-level changes in “how we conceptualize and integrate research into action [and] how the various worlds of academic, government and health services interact with each other” [48, p. 39]. While increasing individual and organizational capacity are important, they argued that systems-level change is critical to address how research is conceptualized, organized and funded, as well as to ensure that trained researchers are embedded in health systems [47]. Thus, building community hospital research culture needs to be a priority for provincial and federal governments, within research funding agencies and in clinical training programs for there to be systems-wide changes. Future work should seek to engage leaders, decision-makers and other key knowledge users at all levels of the Canadian healthcare system to develop strategies for strengthening national health system research culture and capacity.

Limitations and strengths

This study includes several limitations. First, participants self-reported the level of maturity of their community hospital research program. Pre-existing criteria for defining the level of community hospital research program maturity do not exist, however, this self-reported measure was compared with participants’ experiences of research culture at each level to create criteria for what research culture looks like at various levels of community hospital maturity, providing a novel contribution to existing literature. Second, purposeful sampling was used to recruit participants who were knowledgeable about or interested in community hospital research. This helped to enrich the content of the interviews, specifically amongst participants from “established” research programs who could speak to their past and present experiences; however, it resulted in responses that were broadly supportive of research, with only one individual reporting that they were not interested in expanding research at their hospital. Including more individuals with unfavourable views of research, such as through negative case sampling, may have provided a deeper insight into participants perceptions of research culture in community hospitals with negative research cultures.

Third, although we aimed to achieve widespread representation from across Canada, approximately half of the participants were from the province of Ontario, which has the most community hospitals [1]. Further, 5 hospital administrators and 10 research staff members were recruited compared with 23 healthcare professionals. Although a more even distribution of professional roles may have been ideal, this distribution was expected, as many community hospitals do not have dedicated research staff, and as participants described, community hospital administrators may not be aware of, or involved in, research. Fourth, all of the healthcare providers who participated worked within the ICU. Different hospital units may have their own sub-cultures with a different set of shared assumptions, values, beliefs and behaviours [16], which may limit the transferability of the findings to other clinical disciplines. However, the inclusion of participants with different professional roles and diverse levels of involvement with community hospital research enabled the research team to interpret shared themes and patterns despite heterogeneity within the sample and to recognize discrepant cases, thereby strengthening the findings of the study [24]. Finally, the decision to explore the emerging concept of research culture after commencing data collection limited the research team’s ability to probe participants about the phenomenon during earlier interviews.

Conclusions

Strengthening community hospital research culture is important for expanding Canada’s health system research capacity. This study provides an understanding of research culture in Canadian community hospitals, reflecting research programs at different levels of maturity, and offers targeted strategies to help community hospitals advance their research culture. By emphasizing the value of research embedded in clinical practice and by viewing it as a professional responsibility, community hospitals without pre-existing research programs were able to foster a research culture. Starting a research program from the ground-up without significant supports is challenging, however, this is how many Canadian community hospitals have initiated their research programs. Moving forward, building research capacity and culture in community hospitals should be a priority at all levels of the Canadian healthcare system to create a learning health system that values continuous learning, growth and evidence-based practice [48]. Furthermore, health research funding agencies and networks should reconceptualize how research funding is delivered and how community hospital-based research is valued to improve the quality of Canadian health service delivery. In the meantime, community hospital professionals need to foster a culture of inquiry and engage their colleagues in perceiving research as a priority because it benefits their patients, organizations and the communities that they serve.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the participants who took part in this this study.

Career support

D.C. is supported by a Canada Research Chair from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Abbreviations

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- COREQ

Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research

Author contributions

K.R., M.L., K.H. and J.T. conceived the study. K.R., P.G. and M.L. conducted the interviews. K.R. and M.L. analyzed the data. All authors participated in the interpretation of some or all of the results. K.R. prepared the manuscript and all authors revised it critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

J.T. received a grant from the Physicians’ Services Incorporated (PSI) Foundation to support this work.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study received approval from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (Study 14222). Informed written consent for participation was obtained for all participants prior to each interview. Participants were informed that they were free to withdraw from the study at any time and up to 2 weeks after the interview. Participant confidentiality was maintained by de-identifying the data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

J.T. and A.B. are clinician–scientists and clinical research program leads working in Canadian community hospitals with established research programs. J.T. is the Executive Director and Chief Scientist of a community hospital-based research institute. A.B. leads the Critical Care Research Program at a community hospital. Both A.B. and J.T. are co-founders and co-chair of the Canadian Community ICU Research Network. K.R. is a research coordinator, and E.O. and R.M. are research managers working in Canadian community hospitals with established research programs.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hospital Beds Staffed and In Operation, 2022–2023 [Internet]. Ottawa, Ont.: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2024. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/beds-staffed-and-in-operation-2022-2023-data-tables-en.xlsx&ved=2ahUKEwixwtCIipqHAxVeGTQIHaT9Cc4QFnoECBsQAQ&usg=AOvVaw1Y21y3elxaDcma3ApTc0KH

- 2.Dimond EP, St D, Germain LM, Nacpil HA, Zaren SM, Swanson CM, et al. Creating a “culture of research” in a community hospital: strategies and tools from the national cancer institute community cancer centers program. Clin Trials. 2015;12(3):246–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gehrke P, Binnie A, Chan SPT, Cook DJ, Burns KEA, Rewa OG, et al. Fostering community hospital research. CMAJ. 2019;191(35):E962–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiDiodato G, DiDiodato JA, McKee AS. The research activities of Ontario’s large community acute care hospitals: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snihur A, Mullin A, Haller A, Wiley R, Clifford P, Roposa K, et al. Fostering clinical research in the community hospital: opportunities and best practices. Healthc Q. 2020;23(2):30–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsang JLY, Binnie A, Duan EH, Johnstone J, Heels-Ansdell D, Reeve B, et al. Academic and community ICUs participating in a critical care randomized trial: a comparison of patient characteristics and trial metrics. Crit Care Explor. 2022;4(11): e0794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harding K, Lynch L, Porter J, Taylor NF. Organisational benefits of a strong research culture in a health service: a systematic review. Aust Health Rev. 2017;41(1):45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsang JLY, Binnie A, Farjou G, Fleming D, Khalid M, Duan E. Participation of more community hospitals in randomized trials of treatments for COVID-19 is needed. CMAJ. 2020;192(20):E555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsang JLY, Fowler R, Cook DJ, Ma H, Binnie A. How can we increase participation in pandemic research in Canada? Can J Anaesth. 2021;69(3):293–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsang JLY, Fowler R, Cook DJ, Burns KEA, Hunter K, Forcina V, et al. Motivating factors, barriers and facilitators of participation in COVID-19 clinical research: a cross-sectional survey of Canadian community intensive care units. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(4): e0266770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang M, Dolovich L, Holbrook A, Jack SM. Factors that influence community hospital involvement in clinical trials: a qualitative descriptive study. Eval Clin Pract. 2022;28(1):79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alison JA, Zafiropoulos B, Heard R. Key factors influencing allied health research capacity in a large Australian metropolitan health district. JMDH. 2017;10:277–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis PJ, Yan J, De Wit K, Archambault PM, McRae A, Savage DW, et al. Starting, building and sustaining a program of research in emergency medicine in Canada. Can J Emerg Med. 2021;23(3):297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lamontagne F, Rowan KM, Guyatt G. Integrating research into clinical practice: challenges and solutions for Canada. CMAJ. 2021;193(4):E127–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilkes L, Jackson D. Enabling research cultures in nursing: insights from a multidisciplinary group of experienced researchers. Nurse Res. 2013;20(4):28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mannion R, Davies H. Understanding organisational culture for healthcare quality improvement. BMJ. 2018;28:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schein EH, Schein P. Organizational culture and leadership. 5th ed. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Golenko X, Pager S, Holden L. A thematic analysis of the role of the organisation in building allied health research capacity: a senior managers’ perspective. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gehrke P, Rego K, Orlando E, Jack S, Law M, Cook D, et al. Factors influencing community intensive care unit research participation: a qualitative descriptive study. Can J Anesth. 10.1007/s12630-024-02873-4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Bradshaw C, Atkinson S, Doody O. Employing a qualitative description approach in health care research. Global Qual Nurs Res. 2017;1(4):233339361774228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandelowski M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(1):77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kashan J, Wiewiora A. Methodological alignment in qualitative research of organisational culture. In: Newton C, Knight R, editors. Handbook of Research Methods for Organisational Culture [Internet]. Edward Elgar Publishing; 2022 https://www.elgaronline.com/view/edcoll/9781788976251/9781788976251.xml. Accessed 11 Dec 2022

- 24.Patton MQ. Purposeful Sampling. In: Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods [Internet]. 3rd ed. Sage Publications; 2002 https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/qualitative-research-evaluation-methods/book232962. Accessed 12 Aug 2022

- 25.Luciani M, Campbell K, Tschirhart H, Ausili D, Jack SM. How to design a qualitative health research study. Part 1: design and purposeful sampling considerations. Professioni Infermieristiche. 2019;72(2):152–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual Res Sport Exercise Health. 2021;13(2):201–16. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thorne S. The great saturation debate: what the “S Word” means and doesn’t mean in qualitative research reporting. Can J Nurs Res. 2020;52(1):3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dedoose https://www.dedoose.com

- 30.Braun V, Clarke V, Weate P. Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In: Smith B, Sparkes AC, editors. Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise first published in paperback. London: Taylor & Francis Group; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merriam SB, Tisdell EJ. Qualitative research: a guide to design and implementation. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morse J. Reframing rigor in qualitative inquiry. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. Washington DC: SAGE; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bowen S, Botting I, Graham ID, MacLeod M, Moissac DD, Harlos K, et al. Experience of health leadership in partnering with university-based researchers in Canada – A call to “reimagine” research. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2019;8(12):684–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luckson M, Duncan F, Rajai A, Haigh C. Exploring the research culture of nurses and allied health professionals (AHPs) in a research-focused and a non-research-focused healthcare organisation in the UK. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(7–8):e1462–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borkowski D, McKinstry C, Cotchett M, Williams C, Haines T. Research culture in allied health: a systematic review. Aust J Prim Health. 2016;22(4):294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gee M, Cooke J. How do NHS organisations plan research capacity development? Strategies, strengths, and opportunities for improvement. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones ML, Cifu DX, Backus D, Sisto SA. Instilling a research culture in an applied clinical setting. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(1):S49-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slade SC, Philip K, Morris ME. Frameworks for embedding a research culture in allied health practice: a rapid review. Health Res Policy Sys. 2018;16(1):29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matus J, Walker A, Mickan S. Research capacity building frameworks for allied health professionals – A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Homer C, Woodall J, Freeman C, South J, Cooke J, Holliday J, et al. Changing the culture: a qualitative study exploring research capacity in local government. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skinner EH, Williams CM, Haines TP. Embedding research culture and productivity in hospital physiotherapy departments: challenges and opportunities. Aust Health Review. 2015;39(3):312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bowen S, Graham I, Botting I. It’s time to talk about our relationship with research- A guide to making research activities and investments work for- rather than overwhelm- your health organization. The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute: https://iktrn.ohri.ca/download/3250/. Accessed 11 Jan 2024

- 44.Cooke J. A framework to evaluate research capacity building in health care. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6(1):44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frakking T, Craswell A, Clayton A, Waugh J. Evaluation of research capacity and culture of health professionals working with women, children and families at an Australian public hospital: a cross sectional observational study. JMDH. 2021;14:2755–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schein EH. Organizational culture and leadership. 1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bowen S, Botting I, Graham ID. Re-imagining health research partnership in a post-COVID world: a response to recent commentaries. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2020;12:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.The EPIC Learning Health System. Alliance for Healthier Communities. https://www.allianceon.org/EPIC-Learning-Health-System

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.