Abstract

Background

Workplace bullying and harassment (WBH) in healthcare settings has been widely described in the literature, although a lack of consensus on the definition of behaviours constituting WBH makes findings difficult to interpret. The consequences for those experiencing WBH can be severe, including burnout, stress, and suicidal ideation, yet formal reporting rates are low, in part due to a lack of understanding of WBH and the support services designed to address it. Those who experience WBH are more likely to reproduce the behaviour, creating a self-perpetuating cycle. There is an urgent need to develop educational tools to help trainees identify behaviours that can constitute WBH, and the support services available to address this issue.

Methods

The study setting was four acute hospital sites in Ireland; participants were interns (junior doctors in their first postgraduate year). A card-based discussion game, PlayDecide: Teamwork was developed with a multidisciplinary team (MDT), piloted, and implemented. Feedback was obtained from participants on the acceptability and educational value of the game via an anonymous online survey. The intervention is presented using the TIDieR framework. Data were analysed and presented using descriptive statistics.

Results

Intern trainers and facilitators expressed satisfaction with the game. Intern attendance at the PlayDecide sessions was estimated at 63.64% (n = 70), with a 57.14% response rate to the survey (n = 40). The majority of interns found the game acceptable, the cards realistic and relevant, and agreed that it was a safe space to discuss workplace issues. Most interns agreed that the learning objectives had been met, although fewer agreed that they had learned about support services.

Conclusion

PlayDecide: Teamwork is to the best of our knowledge the first intervention of its kind aimed at addressing WBH, and the first aimed at interns. We have shown it to be effective and acceptable to interns and intern trainers in the acute hospital setting. We hypothesised that strong group identification facilitated the discussion, and further, that the cards created cognitive distance, allowing for free discussion of the issues depicted without needing to divulge personal experiences. Further evaluation at behavioural and organisational levels is needed.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-024-06308-y.

Keywords: Workplace bullying, Harassment, Trainee experience, Incivility, Junior doctors

Background

Bullying is recognised as one of the most significant stressors in contemporary working life [1]. Perceived workplace bullying and harassment (WBH) and mistreatment of trainee doctors occurs across disciplines and geographic locations [2–5], with one systematic review reporting the global pooled prevalence among medical residents at 51% [6], although rates can vary widely. The consequences can be severe: trainees exposed to mistreatment report higher stress levels and lower quality of life [5], and are at greater risk of burnout [6, 7] and suicidal thoughts [2]. Despite this, trainees often decide not to take formal action in response to this behaviour, with fear of victimization or reprisal, and lack of knowledge or confidence on the reporting process cited as major barriers [3, 8, 9]. A lack of confidence in reporting systems is not without foundation: in one study, among those who took action, less than a third reported that the behaviour stopped as a result [3]; in another study of over 1,000 ophthalmology trainees, only 9.5% of those who reported bullying commented that the behaviour stopped [9]. Differing interpretations of the types of behaviour that constitute WBH may also be associated with under-reporting [10].

Although widely reported in the literature, there is a lack of consensus on the definition of WBH. There exists significant demographic, geographic and cultural variability around which behaviours are considered acceptable or not. Furthermore, prevalence surveys do not always provide a definition of the terms to their participants, leaving it up to personal interpretations which can also be variable [11]. While this may occasionally be a deliberate omission in order to explore employees’ perceptions of the environment as a metric of workplace safety [2], the result is considerable heterogeneity among studies examining this issue. In Ireland, the Irish Medical Council surveys trainees on their experiences of bullying and harassment: in the 2015 survey (n = 1035), 35% of trainees reported they had experienced WBH, and of those, 68% did not tell a person in authority. The most junior doctors, known as interns, reported the greatest exposure to bullying/harassment, with 48% prevalence. However, the questionnaire lacked a definition of WBH, making the findings difficult to interpret [12]. It is possible that there is a lack of understanding of the workplace behaviours which constitute WBH, with misidentification of behaviours leading to both an overestimation and an underestimation of the true prevalence of WBH with an associated under-reporting to support services. There is a need to provide education so that trainees can accurately identify behaviours that constitute WBH, mistreatment, and incivility, and appropriately avail of the support services designed to address these issues.

There are many antecedents to bullying, and both individual and organisational factors are thought to play a role [1]. Targets of bullying behaviour are more likely to be younger (under 30), and to have spent a short amount of time in a post [13–15]. Interns, i.e., junior doctors in their first year of postgraduate training, rotate through four 3-month posts as part of a 12 month training scheme and as such may be considered particularly vulnerable to WBH due to their age (the majority are < 30), and their somewhat peripatetic role. A significant individual predictor of bullying behaviour in the workplace is having been the target of a bully, i.e., those who have been bullied may go on to bully others [16, 17]. This behaviour may be explained by Bandura’s social learning theory: a senior clinician modelling bullying behaviour influences the behaviour of those who are the targets, creating a self-perpetuating cycle [13, 18]. Moreover, mistreatment and intimidation are often accepted in healthcare settings and considered an unavoidable part of clinical training [6]. If interns are particularly vulnerable to exposure to bullying behaviour, and work in an environment where it is seen as acceptable, they may be at higher risk of reproducing bullying behaviour, and there is evidence for frequent incidents of junior doctors bullying other healthcare professionals, e.g., radiographers [19]. There is an urgent need to break the bully-victim cycle and challenge the acceptance of intimidation and mistreatment as a normal part of the clinical environment.

Formal reporting and workplace policy around WBH are the traditional means of addressing the problem. This approach has been shown to be ineffective, with the majority of bullying targets choosing not to report the behaviour [11]. There have been calls to develop educational interventions that promote a safe learning environment [13], however evidence to support such interventions in medicine is currently limited [11, 20]. In nursing, educational interventions to address WBH and incivility commonly take the form of Cognitive Rehearsal (CR) [20]. This technique involves participants discussing and practicing a response to a social situation with the aid of a facilitator [21] and there is evidence to support this approach [11]. However, CR frames the participants as the targets of bullying behaviour and may not stimulate reflection on participants’ own behaviour. Other approaches such as didactic teaching may be counter-productive, as adult learners are unlikely to respond well to “being lectured to” about their behaviour. A more acceptable approach may be experiential or active learning incorporating small group discussions which enable staff to reflect on their own behaviour and that of others in a safe environment [10]. The American Medical Association’s (AMA) guide to prevention and management of WBH in healthcare advocates for education and open discussion [22], and the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) toolkit for promoting civility recommends guided discussions to explore both unacceptable and preferred behaviours among staff [23].

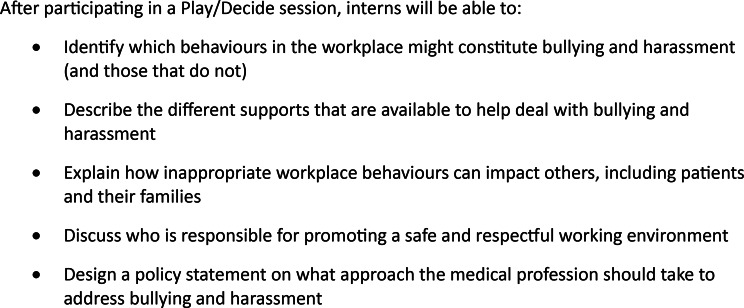

Educational games are a type of experiential learning. Learners are provided with an active experience which facilitates the conceptualization of knowledge and active experimentation with the knowledge [24]. Game-based learning has become increasingly popular in medical education, and studies have shown that educational games are rated highly by trainees, improve knowledge and confidence, and enhance collaboration skills [25]. PlayDecide is an open-access card-based discussion game which has been used across a wide range of topics including but not limited to plastic pollution, genome editing, childbirth, and the impact of astronomical observatories on terrain and society [26]. Recently, it has been successfully used as a tool to raise awareness about patient safety and adverse incident reporting among interns in Ireland [27]. The aim of this study was to raise awareness among interns about the types of behaviours that constitute bullying and harassment, and the supports that are available to help deal with these behaviours. The objectives were to explore whether PlayDecide sessions were acceptable to interns, and whether they achieved the learning objectives of the session (Fig. 1). This paper describes the co-design and implementation of PlayDecide: Teamwork at four different intern training sites, and reports on participant feedback.

Fig. 1.

Learning objectives of Play/Decide session

Methodology

Participants and setting

Participants in the study were interns employed in four major hospital sites in Ireland between 2022 and 2024. The game was run during intern teaching, which is protected time for teaching that occurs weekly or bi-weekly during the working day, usually lunchtime, on the hospital site. Further information on the setting is provided in Fig. 2.

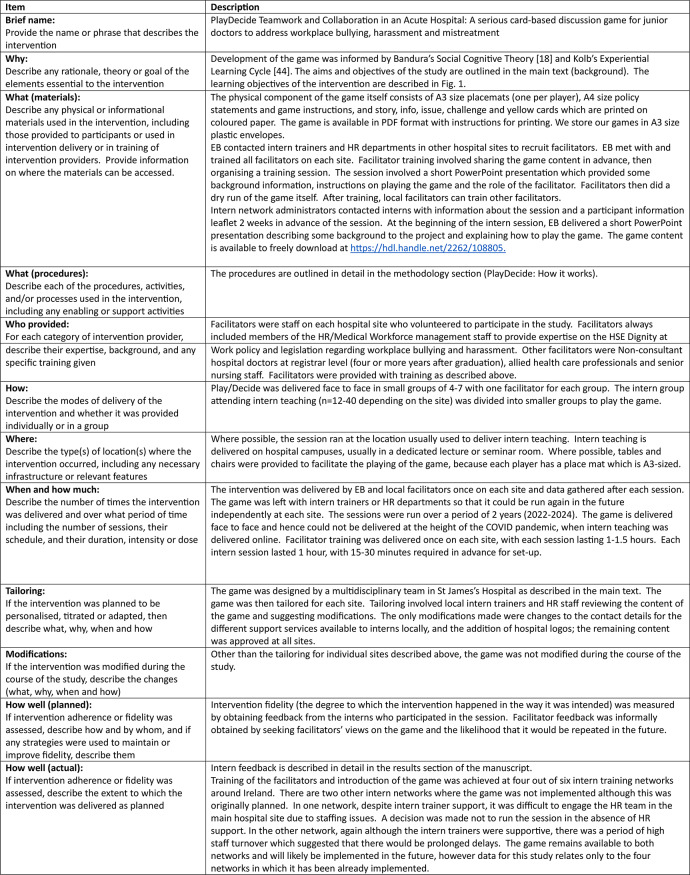

Fig. 2.

TIDieR checklist. (adapted from Hoffman et al. [32])

PlayDecide: how it works

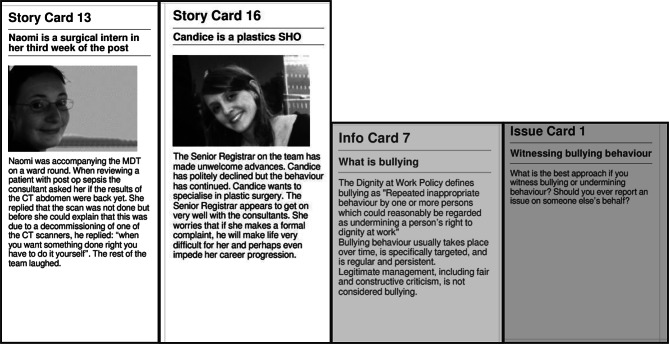

PlayDecide is a discussion game which allows participants to talk in a simple and effective way about challenging topics. The game is played by 4–7 players sitting around a table with a facilitator to help guide the discussion. The standard duration is 90 min but can be as little as 30 min. We used three sets of cards: story cards, information cards and issue cards. Story cards show how an individual is affected by an issue, Information cards give basic factual information, and Issue cards raise issues and opinions for people to think about and agree or disagree as they choose (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Examples of story, info and issue cards

The full set of cards is dealt out to participants who choose one or two of each type of card that will best help them discuss the topic. Once the pool of cards is chosen, players explore it to make sense of the information so they can develop or refine their opinion. Cards may be grouped together in clusters, with each cluster representing a theme or argument. The final stage of the game involves having participants vote on four pre-prepared policy statements and try to construct a shared position, in this case, a response to “What should the medical profession do about the issue of bullying and harassment?” [26]. The learning objectives of PlayDecide: Teamwork are set out in Fig. 1.

Co-design of PlayDecide

A multi-disciplinary team of staff members who volunteered to join the project were brought together by the first author (EB). Team members were, at the time, members of the Non-Consultant Hospital Doctors’ (NCHD) Committee and an interdisciplinary health professions’ education group, both based in St James’s Hospital, or were identified by other team members. The team consisted of a Lecturer in Intern Training and Education (EB), a senior Physician and Director of the Postgraduate Training Centre (DB), a business partner with the Human Resources (HR) department (MD), a Specialist Medical Trainee with a leadership role (Lead Non Consultant Hospital Doctor, NCHD) (OH), a senior member of Nursing staff (JO’G), and a senior Physiotherapist (AW) (positions indicated were the positions held at the time of game development). The team met to discuss the approach to developing cards for the game and learning objectives, consider the policy statements and devise a long list of topics for story, issue and info cards. The title of the game (PlayDecide: Teamwork) was agreed on as it frames the intervention as an approach to enhancing positive behaviour, rather than a sole focus on stopping bad behaviour. Team members developed story, info and issue cards which were reviewed by the other team members and consensus on the cards for inclusion was reached through discussion. Content for the cards was drawn from anecdotal experience, the Irish Health Service Executive’s (HSE) Dignity at Work Policy [28], and the scientific literature (e.g [12, 29, 30]). The story cards depict a range of behaviours including definite WBH, incivility, harassment, sexual harassment, valid criticism, and positive teamwork and collaboration. Stories are told from the perspective of interns, other healthcare professionals, students, and patients/family. The game was piloted with a group of interns in St James’s Hospital and reviewed following their feedback.

Multi-site involvement

Following a successful pilot, funding was awarded from the HSE National Doctors Training and Planning (NDTP) Development Fund to share the game with other intern training networks. There are six intern networks nationally, each with 1–3 major tertiary hospitals. Funding was provided for one hospital site per network so where possible, the largest hospital was chosen to maximise participation. Ethical approval/exemption was granted at all four sites (see full statement below), and each network co-ordinator (programme director) agreed to running the session and circulating the feedback survey among their group of interns. With the help of local intern trainers and HR staff/managers, a bespoke version of the game was created for each site. EB visited each site twice to train local facilitators and run the intern session. Local facilitators typically included senior NCHDs, nursing staff, allied health care staff and members of the HR department. All interns on participating sites received an email circulated by network administrators about the session two weeks in advance and were informed that attendance would be voluntary. A hot lunch was offered as an incentive.

Complete reporting of the intervention

Literature around interventions to address WBH has been previously described as patchy, and often lacking in substantive detail [10]. Further, the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 statement recommends that interventions be reported with sufficient detail to allow for replication [31]. The Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist was developed to improve the completeness of reporting of interventions with the aim of enhancing replicability. The 12-item checklist is applicable across all evaluative study designs [32]. Figure 2 provides additional detail on the educational intervention described in this paper according to the TIDieR framework including a link to download the full game content to allow others to replicate the intervention.

Data tools, collection, and analysis

Feedback from interns who participated in the game was obtained via an anonymous online survey distributed using Qualtrics software, version 4/23 [33]. The survey was designed by the team and piloted with the group of interns who also piloted the game. Experiences of bullying/harassment have been associated with a wide range of negative emotions including fear, anger and shame [34], so we first wanted to establish that the interns felt that the game was acceptable, i.e., the session was a safe space and did not feel intimidated by the environment. We also wished to establish whether the learning objectives of the game (Fig. 1) were met, and lastly, if the interns had any suggestions for improvement. We did not gather any data on interns’ personal experiences of bullying or harassment as that was beyond the scope of this study, and has already been investigated [12]. The full questionnaire is available in Supplementary File 1.

Questionnaires were distributed via QR Code and email by the intern network administrators immediately after the session, with two further email reminders a week apart. Emails were drafted by EB but distributed by network administrators so that interns’ contact details did not need to be shared. As the sessions occurred consecutively on the different sites, the questionnaires were distributed at four different time points between 2022 and 2024. There was no comparator group, so basic descriptive statistics are reported.

Results

Intern participation in the game and survey

Attendance at the intern sessions was not recorded to ensure participation in the study would be completely voluntary, however an estimated 70 interns took part across the four sites. Currently (for 2024-25), the total number of interns across the four sites is 178 [35]. With annual leave, sick leave, clinical commitments etc., the number of interns who could have availed of the sessions is estimated at around 110.

Of those who took part in the session, 48 responded to the survey, of which 40 were complete responses. Accepting a total of 70 participants and a maximum possible total of 110 participants, this suggests a 63.64% participation rate, 57.14% response rate among participants in the game, and 36.36% of the total possible cohort. Twenty-five survey respondents (62.5%) were female with the remaining 37.5% identifying as male. Thirty (75%) entered medical school as undergraduates.

Acceptability of PlayDecide

Thirty-eight respondents (95%) agreed with the statement “The stories and issues were relevant to my day to day working life”. Thirty-seven (92.5%) agree that it was a safe environment to discuss workplace issues affecting them. Thirty-three (82.5%) disagreed that they found the environment or discussion intimidating. All forty respondents agreed that they felt involved in the group discussion. Thirty-five respondents (87.5%) agreed that they would recommend the game to other interns (Table 1).

Table 1.

Intern feedback (n = 40)

| Question | Strongly agree, n (%) | Somewhat agree, n (%) | Neither agree nor disagree, n (%) | Somewhat disagree, n (%) | Strongly disagree, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptability | |||||

| The stories and issues were relevant to my everyday life | 27 (67.5) | 11 (27.5) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.5) | 0 |

| I felt it was a safe environment to discuss workplace issues affecting me | 28 (70) | 9 (22.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 1 (2.5) |

| I felt involved in the group discussion | 36 (90) | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| I felt intimidated by the environment or discussion | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 3 (7.5) | 6 (15) | 27 (67.5) |

| Educational value | |||||

| I learned something new from the Play/Decide board game | 15 (37.5) | 21 (52.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (7.5) | 1 (2.5) |

| The policy statements made me think about how to tackle the issue of bullying and harassment | 13 (32.5) | 19 (47.5) | 4 (10) | 4 (10) | 0 (0) |

|

In relation to the learning objectives, please rate the following statements: I can… identify workplace behaviours which constitute bullying and harassment |

16 (40) | 22 (55) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| … describe the different supports that are available to help deal with bullying and harassment | 11 (27.5) | 14 (35) | 8 (20) | 6 (15) | 1 (2.5) |

| … explain how inappropriate workplace behaviours can impact others | 18 (45) | 20 (50) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| …discuss who is responsible for a safe and respectful work environment | 15 (37.5) | 22 (55) | 2 (5) | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) |

| Definitely, yes, n (%) | Probably, yes, n (%) | Might or might not, n (%) | Probably not, n (%) | Definitely not, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Would you recommend participating in this teaching session to other interns? | 18 (45) | 17 (42.5) | 2 (5) | 3 (7.5) | 0 (0) |

Educational value of PlayDecide

When asked if they had learned something new from the PlayDecide session, 36 respondents (90%) agreed. Thirty-two (80%) agreed that the policy statements had made them think about how to tackle the issue of bullying and harassment.

With respect to the learning objectives, 38 (95%) agreed that they can now identify workplace behaviours that constitute bullying and harassment, 25 (62.5%) agreed that they can describe the different supports that are available to them to address bullying and harassment, 38 (95%) agreed that they can explain how inappropriate workplace behaviours can affect others, and 37 (92.5%) agreed that they can discuss who is responsible for a safe and respectful working environment (Table 1).

Free text comments

Participants were asked if they had any suggestions on improving the game and if they had any final comments. Eight responded to the request for suggestions to improve the game. There was insufficient data to thematically analyse the responses. Two suggested not involving HR staff as they made it “too formal”, however one suggested involving senior management. One suggested including advice for dealing with issues that do not qualify as bullying or harassment, one suggested shorter cards, and one suggested separate rooms for each group. The remaining two responded “No”.

Six responded to the request for final comments, again there was insufficient data to thematically analyse responses. One repeated the suggestion that HR be removed as “the presence of HR makes everything too formal, and people are unable to express their actual thoughts on the matter”. Another suggested that intern turnout would be better if the game were run at the start of the intern training year, during induction. Others expressed their thanks, e.g., “Thank you for a refreshing session”.

Discussion

We set out to explore whether a serious card-based discussion game, PlayDecide: Teamwork, would be an acceptable and effective educational intervention, and provide a sufficient framework for discussion among interns about the types of behaviours that constitute bullying and harassment, as well as the supports that are available to help deal with these behaviour. We have also described in detail the co-design and implementation of the educational intervention across multiple sites.

The game was welcomed by intern trainers and HR managers across four out of six intern networks nationally. Staffing issues precluded it from being implemented in 2 sites, but interest has been expressed in doing so in future. Intern trainers and HR managers on all four sites retained copies of the game to run future sessions with interns and other groups, indicating a high degree of acceptance among trainers. A bespoke version of the game was created for each network, with the only modifications required being local contact details and hospital logos, suggesting that the game content is appropriate and applicable to other sites.

Intern participants also indicated that the game was acceptable to them, with the majority agreeing that they felt it was a safe environment to discuss workplace issues affecting them, and that they felt involved in the group discussion. A majority also indicated that they did not feel intimidated by the environment or discussion, however four participants agreed or strongly agreed that they did. On further exploration, three of these four participants also strongly agreed that it was a safe environment to discuss workplace issues, and that they felt involved in the group discussion. It is possible therefore that because this question was flipped (i.e., strongly agree became a negative response), that it may have caused some confusion and that the responses of these three participants are not reflective of their actual views. The survey was anonymous, so it was not possible to confirm this.

In addition to being acceptable, interns rated the educational value of the sessions highly, with the majority agreeing that they had learned something new, and that all four learning objectives had been met. Small group discussions have been shown to help students apply new knowledge to solving complex problem and consider issues from alternative perspectives. The effectiveness of the group discussion can be enhanced by group identification, i.e., the degree of connectedness between participants [36, 37]. Interns form a distinct group in the hospital – they are the most junior medical professionals and are on a year-long training scheme. Many of them trained as undergraduates in the same medical school. They are likely therefore to identify strongly with other interns, and indeed previous research has shown that trainees in the transition period from student to doctor experience strong social identification with other practitioners [38]. This strong degree of group identification could help facilitate the discussions and maximise learning opportunities. Conversely, it may also explain the resistance to the presence of others, e.g., HR staff. Self-categorization or self-grouping creates an in-group (e.g., interns) who are compared and contrasted with other groups, or out-groups, with a resultant potential for inter-group conflict [39]. In this situation, HR staff, as non-clinicians, may have been viewed by some as an out-group, leading to a resistance to their presence. It must be noted that resistance was indicated by only two participants, both from the same site, and is contradicted by another participant who suggested senior management be involved. The authors agree that the presence of HR for these sessions is of critical importance to support not only interns but also the clinical facilitators who have less detailed knowledge of employment law or the Dignity at Work policy. Furthermore, it is essential to include alternative perspectives to enhance the richness of the discussion. The importance of HR in supporting the trainee experience has been highlighted in the Irish Department of Health’s recent Interim Report of the National Taskforce on the NCHD Workforce [40]. Nonetheless, this phenomenon may be an important consideration for future group discussions involving a more diverse set of participants, including cross-specialty, interdisciplinary or interprofessional.

Another strength of the game which may have enhanced its acceptability is the use of story cards depicting scenarios involving healthcare staff, patients and students, where bullying, harassment, or incivility may have or definitely occurred. Story cards were developed by the multidisciplinary team comprising experienced clinicians, educators, and a HR manager. Interns were almost unanimous that the cards were relevant to their everyday lives. These cards could have been used as a proxy by interns to discuss actual incidents that they experienced or witnessed, without having to disclose their personal experience. Participants in a discussion group may be reluctant to disclose personal experiences of bullying, harassment or incivility due to feelings of shame or fear [34], or a perceived identity threat [41], e.g., the fear that others might view them as weak or unable to stand up for themselves, or that others might view their behaviour as bullying. The cards may have created a cognitive and emotional “distance” from the issues portrayed, allowing free discussion and elicitation of the views of others without a need to publicly expose personal experiences. For example, an intern could discuss a scenario similar to one they personally experienced and explore how the characters in the story could or should have behaved in an abstract sense with other participants, without needing to divulge their own experiences and behaviours. Creation of cognitive distance has been shown to be an effective approach to facilitating classroom discussions of controversial topics [42]. This hypothesis would require further investigation, but it may partially explain the high level of acceptability among interns, and also signal that the game may be further adapted and used to discuss other topics considered sensitive or controversial.

The learning objective of the teaching session which was least met was describing the different supports that are available to help deal with bullying and harassment. While a majority agreed that it was met (62.5%), there was a substantial minority who were ambivalent or negative about whether it was met (37.5%). This is disappointing, because one of the main objectives of the project was to raise awareness about these supports. It has been well-documented that healthcare workers who experience bullying tend not to report it, with a lack of knowledge of support services a known barrier [8]. This may be a potential drawback of this type of discussion group: while facilitators were present to prompt discussion and help guide it, the participants drive the discussion. Further, the game was condensed to fit with the one-hour protected time allocated to intern teaching, limiting the time available for detailed discussion and the extent to which all material could be covered. Another consideration may be that support services were highlighted in the context of dealing with bullying and harassment, not incivility, which arguably is a more common experience, and a participant commented on this limitation in the free text. This part of the game could be refined to present support services available for all types of negative workplace behaviours. Future sessions could be split over two intern teaching sessions, or interns could also be provided with written material on the various support services available to them. This finding also suggests that a single PlayDecide: Teamwork session alone may not be sufficient to cover the material, and we would caution against its use as the sole source of education on this topic.

Limitations

Findings of this study should be considered in the context of the low response rate. While one strength is the multi-site implementation, participation in the session and survey could be considered moderate. The study would have been strengthened had a greater number of interns participated in the session and provided feedback, and we recommend that findings be interpreted with caution. The session was voluntary, which could have impacted attendance, and it is possible that those who are more likely to engage in bullying behaviour may have avoided the session, creating a potential sources of bias.

Another limitation is that the evaluation of the intervention has been carried out only at the first two levels of the Kirkpatrick model of evaluation, i.e., participants’ reaction and learning [43]. Evaluation of the impact of the intervention on the participants’ behaviour and the impact on wider organisational goals were beyond the scope of this study. Further, learning was self-reported as opposed to externally assessed, and pre-existing knowledge was not assessed, creating a potential source of bias.

Future research

While the problems of bullying, harassment and incivility in the healthcare environment have been very well-described, there is a lack of evidence for interventions that help address this problem. There is a need to create a strong evidence base to not only understand the issue, but also its potential solutions. Further evaluation of PlayDecide: Teamwork, exploring behavioural and organisational change would be beneficial. Evaluation of the impact of the game at behavioural and organisational levels could be done by a pre-post survey of workplace culture and the prevalence of negative behaviours, staff focus groups, and exploration of data relating to employee complaints. Further work is also needed to understand how to best to engage trainees with the support services that are available to them to deal with workplace mistreatment. Exploration of group dynamics in situations where a strong sense of social identification and self-categorization prevails may improve educators’ understanding of how best to facilitate such sessions and avoid potential issues relating to the creation of in-groups and out-groups. This work would likely have relevance for training beyond game-based discussion groups. Lastly, the hypothesis that using story cards successfully created cognitive and emotional distance and mitigated the threat to self-identity, thus facilitating participation in the session is a potentially useful concept which merits further exploration.

Conclusion

PlayDecide: Teamwork is an educational intervention designed to raise awareness around workplace bullying and harassment behaviours which we have shown to be acceptable to junior doctors and their trainers in the acute hospital setting. We have also shown that most participants found it to be an effective intervention to raise awareness about this issue, and to a lesser extent the support services that are available. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first intervention of its kind aimed at addressing WBH in an acute hospital setting, and the first designed specifically for junior medical trainees. Strengths of the intervention include engagement with key stakeholders including interns, and involvement of a multi-disciplinary team to develop realistic story cards, which may have helped create cognitive and emotional distance, allowing for free discussion without a need to disclose individual experiences. The intervention also may have benefitted from strong group identification among participants. Strong group identification may also negatively impact trainees’ perceptions, e.g., due to the creation of in and out groups; although this was beyond the scope of this study, it is a question which merits further exploration. The open, peer-led nature of the discussion groups and time pressures may have prevented all material from being covered in detail, in particular, information relating to support services. Further research is needed to explore whether such interventions impact behaviour and drive organisational change, and to build an evidence base for solutions to the highly prevalent problem of workplace bullying and harassment.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of Intern Network Executive (INE) Colleagues including Intern Network Co-Ordinators, Intern Administrators, Intern Tutors and Intern Lecturers in permitting the sessions to run in their networks, reviewing content for the game, assisting with local ethics applications, organising venues for facilitator training and the intern session, advertising sessions to interns, identifying facilitators, facilitating sessions, and and sharing the feedback survey with their interns. We wish to acknowledge the assistance of Human Resources Managers and Staff in reviewing the content of the game, updating local contact details, helping with the organisation of the facilitator training and intern sessions, identifying facilitators and facilitating sessions. We wish to acknowledge the assistance of professional colleagues at all four hospital sites in facilitating sessions with the interns. Lastly, we wish to acknowledge the participation of the interns in the PlayDecide sessions and in providing feedback via the online survey.

Abbreviations

- AMA

American Medical Association

- CONSORT

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- CR

Cognitive Rehearsal

- HR

Human Resources

- HSE

Health Service Executive

- NCHD

Non-Consultant Hospital Doctor

- NDTP

National Doctors Training and Planning

- NHS

National Health Service

- QR

Quick Response

- TIDieR

Template for Intervention Description and Replication

- WBH

Workplace Bullying and Harassment

Author contributions

EB and MH made substantial contributions to the conception of the work. EB, MH, DB, MD, OH, JOG and AW made substantial contributions to the design of the work and acquisition of data. EB analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. DB, MD, OH, JOG, AW and MH reviewed the manuscript and provided feedback.All authors have approved the submitted version. All authors agree to be personally accountable for their own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

Funding

This project was part-funded by the HSE NDTP Development Fund (Ref 08INT202). The funder had no role in the conceptualization, design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated and analysed during this study are included in the published article. The content of PlayDecide Teamwork is available to download freely from TARA, Trinity’s Institutional Repository at https://hdl.handle.net/2262/108805 (access restricted until article publication).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval or exemption was sought and obtained locally at all four sites: Trinity College Dublin Original Research Ethics Approval number 20180902, Amendment number 20210701. University College Dublin Research Ethics Exemption number EXE-E-21-01-Burke-TCD. Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland Research Ethics Approval number 212566551. University College Cork Clinical Research Ethics Committee Approval number ECM 4 (t) 20/06/23 and ECM 3 (h) 01/08/2023.

Informed consent

to participate was obtained from participants in line with ethics approvals outlined above.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Maidaniuc-Chirilă T. Workplace bullying phenomenon: a review of explaining theories and models. Annals AII Cuza Univ Psychol Ser. 2020;29:63–85. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu Y-Y, Ellis RJ, Hewitt DB, Yang AD, Cheung EO, Moskowitz JT, et al. Discrimination, abuse, harassment, and Burnout in Surgical Residency Training. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(18):1741–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crebbin W, Campbell G, Hillis DA, Watters DA. Prevalence of bullying, discrimination and sexual harassment in surgery in Australasia. ANZ J Surg. 2015;85(12):905–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Domínguez LC, Torregrosa L, Cuevas L, Peña L, Sánchez S, Pedraza M, et al. Workplace bullying and sexual harassment among general surgery residents in Colombia. Biomedica: revista del Instituto Nac De Salud. 2023;43(2):252–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kemper KJ, Schwartz A, Bullying. Discrimination, sexual harassment, and physical violence: Common and Associated with Burnout in Pediatric residents. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(7):991–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Álvarez Villalobos NA, De León Gutiérrez H, Ruiz Hernandez FG, Elizondo Omaña GG, Vaquera Alfaro HA. Carranza Guzmán FJ. Prevalence and associated factors of bullying in medical residents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Occup Health. 2023;65(1):e12418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garza-Herrera R, Arriaga-Caballero JE, Hinojosa CA, Bobadilla-Rosado LO, Tabárez-Arriaga V, Peñuelas-González EA et al. Relationship of work bullying and burnout among vascular surgeons. JVS-Vascular Insights. 2024:100106.

- 8.Llewellyn A, Karageorge A, Nash L, Li W, Neuen D. Bullying and sexual harassment of junior doctors in New South Wales, Australia: rate and reporting outcomes. Aust Health Rev. 2019;43(3):328–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer JA, Troutbeck R, Oliver GF, Gordon LK, Danesh-Meyer HV. Bullying, harassment and sexual discrimination among ophthalmologists in Australia and New Zealand. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2021;49(1):15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gamble Blakey A, Smith-Han K, Anderson L, Collins E, Berryman E, Wilkinson TJ. Interventions addressing student bullying in the clinical workplace: a narrative review. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halim UA, Riding DM. Systematic review of the prevalence, impact and mitigating strategies for bullying, undermining behaviour and harassment in the surgical workplace. Br J Surg. 2018;105(11):1390–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irish Medical Council. Your Training Counts. Dublin: Irish Medical Council; 2015 2015.

- 13.Abate LE, Greenberg L. Incivility in medical education: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al Muharraq EH, Baker OG, Alallah SM. The prevalence and the relationship of Workplace bullying and nurses turnover intentions: A Cross Sectional Study. SAGE open Nurs. 2022;8:23779608221074655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ervasti J, Pentti J, Seppälä P, Ropponen A, Virtanen M, Elovainio M, et al. Prediction of bullying at work: a data-driven analysis of the Finnish public sector cohort study. Soc Sci Med. 2023;317:115590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hauge LJ, Skogstad A, Einarsen S. Individual and situational predictors of workplace bullying: why do perpetrators engage in the bullying of others? Work Stress. 2009;23(4):349–58. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Özer G, Escartín J. The making and breaking of workplace bullying perpetration: a systematic review on the antecedents, moderators, mediators, outcomes of perpetration and suggestions for organizations. Aggress Violent Beh. 2023;69:101823. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nyhsen CM, Patel P, O’Connell JE. Bullying and harassment – are junior doctors always the victims? Radiography. 2016;22(4):e264–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jang SJ, Son YJ, Lee H. Intervention types and their effects on workplace bullying among nurses: a systematic review. J Nurs Adm Manag. 2022;30(6):1788–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clark CM. Combining cognitive rehearsal, simulation, and evidence-based scripting to address incivility. Nurse Educ. 2019;44(2):64–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American, Medical A. Bullying in the Healthcare Workplace: A guide to prevention and mitigation: AMA; 2021 [ https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2021-02/workplace-aggression-report.pdf

- 23.National H, Service E. Supporting our staff: A toolkit to promote cultures of civility and respect: NHS; 2020 [ https://www.socialpartnershipforum.org/system/files/2021-10/NHSi-Civility-and-Respect-Toolkit-v9.pdf

- 24.Akl EA, Pretorius RW, Sackett K, Erdley WS, Bhoopathi PS, Alfarah Z, et al. The effect of educational games on medical students’ learning outcomes: a systematic review: BEME Guide 14. Med Teach. 2010;32(1):16–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu MLY, Zhang Y, Xia R, Qian H. Zou X Game-based learning in medical education. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1113682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Play/Decide. [ https://playdecide.eu/about

- 27.Ward M, Ní Shé É, De Brún A, Korpos C, Hamza M, Burke E, et al. The co-design, implementation and evaluation of a serious board game ‘PlayDecide patient safety’ to educate junior doctors about patient safety and the importance of reporting safety concerns. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.(HSE) HSE. Dignity at Work Policy for the Public Health Services [ https://healthservice.hse.ie/staff/procedures-guidelines/dignity-at-work-policy-for-the-public-health-service/

- 29.Verkuil B, Atasayi S, Molendijk ML. Workplace Bullying and Mental Health: a Meta-analysis on cross-sectional and longitudinal data. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0135225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dzau VJ, Johnson PA. Ending sexual harassment in Academic Medicine. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(17):1589–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gøtzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ: Br Med J. 2014;348:g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qualtrics. Qualtrics. 4/23 ed. Provo, UT. USA: Qualtrics; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vie TL, GlasØ L, Einarsen S. How does it feel? Workplace bullying, emotions and musculoskeletal complaints. Scand J Psychol. 2012;53(2):165–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.(HSE) HSE. NRS14063 Medical Interns Stage 1 & Stage 2- Closing Notification 2024 [ https://www.hse.ie/eng/staff/jobs/job-search/medical-dental/nchd/interns/

- 36.Jones JM. Discussion Group Effectiveness is related to critical thinking through Interest and Engagement. Psychol Learn Teach. 2014;13(1):12–24. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sætra E. Discussing controversial issues in the Classroom: elements of good practice. Scandinavian J Educational Res. 2021;65(2):345–57. [Google Scholar]

- 38.van den Broek S, Querido S, Wijnen-Meijer M, van Dijk M, ten Cate O. Social Identification with the Medical Profession in the transition from student to practitioner. Teach Learn Med. 2020;32(3):271–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burford B. Group processes in medical education: learning from social identity theory. Med Educ. 2012;46(2):143–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Department. Of, Health. National Taskforce on the NCHD workforce: interim recommendations Report. Interim report. Ireland: Department of Health, Health Do; 2023. 13/04/2023. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gert-Jan Wansink B, Mol H, Kortekaas J, Mainhard T. Discussing controversial issues in the classroom: exploring students’ safety perceptions and their willingness to participate. Teach Teacher Educ. 2023;125:104044. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hand M, Levinson R. Discussing controversial issues in the Classroom. Educational Philos Theory. 2012;44(6):614–29. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kirkpatrick DL. Evaluating training programs: the four levels: First edition. San Francisco : Berrett-Koehler; Emeryville, CA: Publishers Group West [distributor], [1994] ©1994; 1994.

- 44.Kolb DA. Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Inc.; 1984.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and analysed during this study are included in the published article. The content of PlayDecide Teamwork is available to download freely from TARA, Trinity’s Institutional Repository at https://hdl.handle.net/2262/108805 (access restricted until article publication).