Abstract

Background

Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disorders beyond Eosinophilic Esophagitis (non-EoE EGIDs) are chronic rare inflammatory disorders characterized by eosinophilic infiltration of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

Case presentation

We report the first pediatric case of eosinophilic duodenitis (one type of the non-EoE EGIDs) with concomitant pancreatic reaction that was misdiagnosed as acute pancreatitis (AP). A 13-year-old girl was admitted to our hospital for a week of abdominal distension, vomiting, and epigastric pain that worsened recently. She was suspected of AP based on increased amylase and lipase values and relevant imaging findings. During hospitalization, her clinical manifestation improved, while the eosinophilia was more aggravated without a known cause. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was performed, and histopathological evidence demonstrated the diagnosis of Eosinophilic duodenitis, which was treated with oral prednisone tapering. During the 1-year follow-up, the patient was symptom-free and presented no signs of recurrence.

Conclusions

Although rare, pediatricians should consider non-EoE EGIDs in the differential diagnosis in children presenting with peripheral blood eosinophilia and duodenal wall thickening on imaging findings.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12887-024-05297-7.

Keywords: Eosinophilic duodenitis, Pancreatitis, Eosinophilia, Ascites, Children

Introduction

Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disorders beyond Eosinophilic Esophagitis (non-EoE EGIDs) are chronic inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract characterized by eosinophilic predominant inflammation of the mucosa leading to organ dysfunction [1, 2]. They include eosinophilic gastritis (EoG), eosinophilic enteritis [EoN, a term that can be further subdivided into eosinophilic duodenitis (EoD), eosinophilic jejunitis (EoJ) and eosinophilic ileitis (EoI)]), and eosinophilic colitis (EoC) [1]. The pathogenesis of non-EoE EGIDs remains elusive. Allergic reactions to dietary antigens may cause some non-EoE EGIDs [2]. The clinical symptoms of non-EoE EGIDs depend on the affected GI segment, the extent of eosinophilic inflammation within the GI tract, and the depth of inflammation through the bowel wall [3]. The diagnosis is usually based on clinical symptoms and histologic evidence of eosinophilic inflammation without biological markers. Therefore, making a diagnosis of non-EoE EGIDs may be challenging. Non-EoE EGIDs are considered rare conditions in children and are usually not life-threatening [4]. Here, we report the first case of EoD with concomitant pancreatic reaction that was misdiagnosed as acute pancreatitis (AP), for which we could not diagnose and intervene in time. Therefore, in recent years, how to make a differential diagnosis and better understand such diseases has attracted more and more attention from pediatricians.

Case presentation

A 13-year-old girl presented to our pediatric department with a week of abdominal distension, vomiting, and epigastric pain that had worsened recently. She complained of continuous pain without diarrhea or fever with an Abdominal Pain Severity - Numeric Rating Scale (APS-NRS) of 3–4. She has experienced recurrent epigastric pain for the past ten years, with no acid-reducing agents relieving her symptoms. Throughout her illness, her Z-score of Stature-for-age, Weight-for-age, and BMI-for-age were within the normal range on the CDC Pediatric Growth Standards, with no signs of growth retardation or late pubertal development. In her medical history, she seemed to have had no allergic diseases such as bronchial asthma, atopic dermatitis, and allergic rhinitis. She was not in contact with any pets. Physical examination was unremarkable except for epigastric tenderness. No abdominal masses were palpated on the exam. An abdominal ultrasound done outside the hospital revealed mild pancreatic duct dilatation and mild ascites (74 × 40 mm).

Upon admission, her vital signs were stable (blood pressure 122/75 mmHg, pulse rate 78 beats/minute, body temperature 36.9 °C, respiratory rate 20 times/minute). Her laboratory test results showed an increased white blood cell count of 1.385 × 104/mm3 (normal, 0.4-1.0 × 104/mm3) and a high percentage of eosinophils of 16.5% (normal, 0.5-5%). The serum biochemistry showed a mild increased serum amylase of 256.6U/L (normal, 40-132U/L) and serum lipase of 134.4U/L (normal, 0-67U/L). Other tests, including serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase, serum bilirubin, serum triglyceride, and serum cholesterol were in the normal range. The urine test revealed high amylase levels of 1921.7U/L (normal, 0-490U/L). The results of fecal ova and parasite inspection were negative two times.

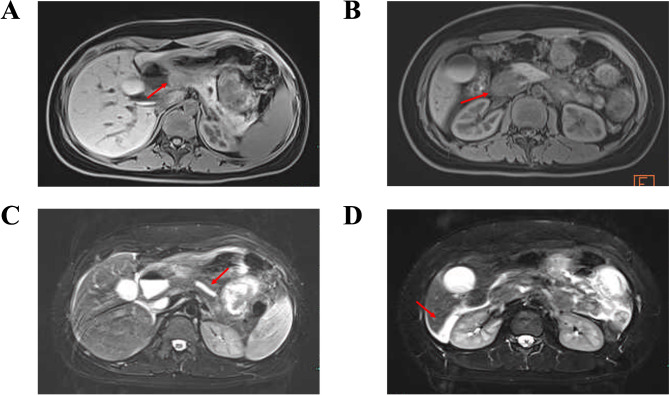

A child presented with abdominal distension, vomiting, and epigastric abdominal pain, slightly elevated serum amylase and lipase levels raised the suspicion of AP, which consistently exhibits similar characteristics, and AP was thought to be the first possibility. Subsequently, abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) were carried out. The CT scans and MRCP revealed diffuse wall thickening of the antrum and duodenum, suggesting a possible inflammatory reaction, mild common bile duct, pancreatic duct dilatation, and some ascites. However, intestinal obstruction, gallstones, and pancreatic swelling were not seen (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A, MRCP image showing the thickening of the wall of the antrum. B, MRCP image showing the thickening of the wall of the duodenum. C, MRCP image showing mild dilated pancreatic duct. D, MRCP image showing some abdominopelvic effusion

During her hospitalization, supportive care, including goal-directed intravenous fluids and correction of electrolyte and metabolic abnormalities, was initiated to treat AP. We thought it was unnecessary to begin supplemental nutrition because of her mild pancreatitis, and start with a low-residue, low-fat, and soft diet (within 24 h) as tolerated, considering that the pain is decreasing and there is no evidence of ileus or significant nausea and vomiting [5, 6]. Her abdominal symptoms gradually reduced within two weeks, and her serum amylase level decreased to normal. However, mild epigastric tenderness persisted, and subsequent laboratory data showed that blood eosinophils had elevated to 31.5% (normal, 0.5-5%), and the eosinophil count was 2.55 × 103/µL (normal, 0.05–0.5 × 103/µL). After two weeks of hospitalization, the eosinophilia increased without a known cause.

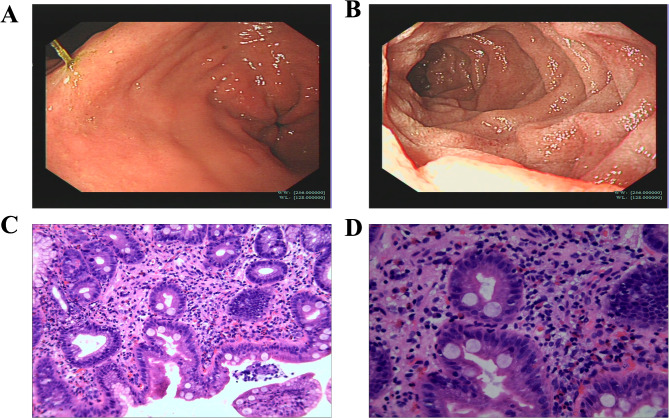

Considering that persistent peripheral eosinophilia may be Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disorders, Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was performed to take biopsies from the GI tract. EGD findings revealed mucosal edema on the antrum and ampulla, diffuse mucosal erythema on the 2nd portion of the duodenum, and pylorus was normal in appearance without pyloric stenosis. Then, multiple biopsies, including gastric antrum and duodenum, were sent for histopathological examination. The examination revealed peak eosinophil counts of 10 per high-power field (HPF) in the mucosa of the gastric antrum. There was prominent eosinophilia in the duodenal mucosa with peak eosinophil counts of 120 per HPF(Fig. 2), with the cutoff number (duodenum: ≥50 eosinophils per HPF) for diagnosis. Endoscopic biopsies revealed chronic mucosal inflammation with prominent eosinophilia extension into muscularis mucosa and submucosa from the duodenal erythematous lesion. Eosinophil crypt abscesses were not observed. The histology for Helicobacter pylori was negative in a gastric mucosa biopsy. Furthermore, allergy examinations were performed, and serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) was in the normal range (19.7kIU/L), and titers of IgE specific to food allergens and aeroallergens were also not elevated. The final diagnosis was EoD based on these findings.

Fig. 2.

A, EDG image revealing hyperemia and edema of the antral mucosa. B, EDG image revealing diffuse punctate erythematous and white specked lesions of the duodenal mucosa. C, Duodenal biopsy histology revealing eosinophilic infiltration in the lamina propria (H&E stain, low-power field). D, Duodenal biopsy histology revealing prominent eosinophilia in the lamina propria (H&E stain, high-power field). The histological examination shows more than 120 eosinophils/high-power field (HPF)

Subsequently, she was treated with a steroid taper plan to induce remission, initially on 40 mg (1 mg/kg) of oral prednisone for two weeks [2], then decreased by 5 mg weekly. Our patient showed rapid resolution of clinical symptoms following treatment, and therapy with oral prednisone significantly reduced eosinophil counts in the peripheral blood (from 2.55 × 103 eosinophils/µL before therapy to 0.3 × 103 eosinophils/µL after therapy). At the follow-up a week later, her laboratory workup was normal, and abdominal ultrasound showed resolution of ascites with no relapse of symptoms. During the 1-year follow-up, the patient was symptom-free and presented no signs of recurrence. She rejected a repeat endoscopic examination to assess the mucosal inflammation and is still being followed up by performing serum eosinophils testing at regular intervals.

Discussion and conclusions

Non-EoE EGIDs are rare immune-mediated disorders of the GI tract observed in children. Patients present with various upper and lower GI symptoms, and these disorders are diagnosed based on clinical manifestations and histologic evidence of eosinophilic inflammation after ruling out a secondary cause or systemic illnesses. It is believed that GI segment-specific threshold eosinophil values are considered prior to making a non-EoE EGIDs diagnosis [2, 3].

Our patient presented with abdominal distension, vomiting, epigastric pain, and slightly increased amylase and lipase values. Imaging findings revealed mild common bile duct and pancreatic duct dilatation without relevant changes in the pancreas (pancreatic swelling, peripancreatic fluid). Considering that she presented with abdominal discomfort for 7 days and mild elevation of lipase and amylase at that time and that her serum amylase and lipase values were less than the discriminatory level (≥ 3 times greater than the upper limit of normal) [5], we could not exclude the possibility of a resolving pancreatic inflammation despite the imaging findings not compatible with AP.

Serum amylase and lipase are rarely attributable to non-EoE EGIDs in children. Therefore, diagnostic errors were more likely to occur. Only a few cases of non-EoE EGIDs in adults accompanied by AP, like this case, have been reported [7–10]. Every case, including this pediatric one, exhibited a concomitant pancreatic reaction with elevated amylase and lipase values by non-EoE EGIDs. All patients had no history of gallstones. In our case, no apparent pancreatic and biliary duct obstructions were found on abdominal CT or MRCP. However, serum levels of pancreatic enzymes were increased when the symptoms were presenting, and alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin were within the normal range, suggesting the eosinophilic infiltration within the GI tract slightly injured the pancreatic duct. We suggested that inflammation in pancreas is due to obstruction of pancreatic duct that is opening a thickened and inflamed duodenal wall, rather than extension of inflammation to pancreas. Imaging findings showing a dilation in the pancreatic duct confirms this suggestion. In addition, peripheral blood eosinophila were ignored initially, leading to delayed diagnosis and therapy. Therefore, non-EoE EGIDs should be kept in mind for differential diagnosis when patients with peripheral blood eosinophilia and abdominal discomfort. On this occasion, peripheral blood eosinophils and duodenal wall thickening on imaging study could be used as indicators of non-EoE EGIDs. Parasitic infection was also considered in the differential diagnosis. Her two separate stool examinations revealed no evidence of ova or parasites. Besides, our patient did not have the nature of any relevant epidemiologic exposure and the ingestion of raw or undercooked fish or shellfish, meat, and vegetables as potential sources of parasitic infection. Since administration of prednisone, our patient showed rapid resolution of clinical symptoms and reduced eosinophil counts in the peripheral blood. Therefore, the parasitic infection was not taken into consideration at that time. To our knowledge, it will be more reliable if the appropriate serology were be obtained [3, 11]. Rarely, inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn disease and Ulcerative colitis may be associated with peripheral eosinophilia and an eosinophil-rich tissue infiltrate. These diseases can usually be differentiated from EGID by the presence of typical architectural distortion, crypt abscesses and granulomas [12].

Peak eosinophil counts are used as GI segment-specific threshold levels prior to diagnosing patients with non-EoE EGIDs [13]. The GI mucosa may look non-specific in many patients with non-EoE EGIDs, even normal in the endoscopy. Thus, it is strongly recommended to obtain multiple biopsies, including gastric antrum, gastric body, and duodenum, taken from the affected segments of the GI tract, from both normal and abnormal appearing sections of the mucosa. The suggested threshold peak eosinophil counts for the diagnosis were ≥ 30 eosinophils per HPF for EoG and ≥ 50 eosinophils per HPF for EoD [2]. Our pediatric patient was finally diagnosed with EoD according to compatible symptoms and signs, histological evidence, and the absence of other diseases related to GI eosinophilic inflammation. Besides, imaging studies do not directly contribute to the diagnosis but give additional information to localize involved areas for targeted tissue diagnosis [2]. One of the overlooked clues for the diagnosis of EoD in our patient was the thickening of the duodenal wall on CT findings, which was caused by eosinophilic infiltration within the GI tract. In general, mild AP rarely affects the GI wall. Only severe AP may lead to adjacent gastric and duodenal wall swelling [6]. On this occasion, the EoG/EoN, although very rare, should be kept in mind.

According to the predominantly involved intestinal layers, Klein et al. divided EoN into three disease subtypes: mucosal, muscular, and subserosal [14]. When the inflammatory process only involves the mucosal level, diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting are the most common symptoms. Iron deficiency anemia and protein loss may also occur [2]. Patients with muscular involvement might present with obstructive symptoms (abdominal distension, severe constipation), and other symptoms described include intussusception and perforation. In previous cases, those involved in the subserosal layer might typically present with ascites [2]. Our case might be the mucosal type because of the clinical manifestations of mucosal involvement (recurrent epigastric pain, vomiting), although she presented with obstructive symptoms like abdominal distension. In most cases of muscular disease, intussusception and perforation of the bowel were typically found, which was supposed to be the primary cause of obstructive symptoms [14]. However, our patient had no intussusception and perforation and was not classified with muscular layer disease. In addition, we have no evidence of subserosal infiltration of eosinophils and hypereosinophilia in ascites for subserosal layer disease [2, 14].

Systemic oral steroids are essential and effective for inducing clinical and histological remission in some studies in children with non-EoE EGIDs [15]. In general, it is recommended to use oral prednisone therapy at a dose of 0.5-1 mg/kg with a maximum of 40 mg for two weeks to induce remission. The prednisone dose is decreased over 2–8 weeks once clinical improvement is attained [16]. However, some patients may relapse when therapy is discontinued, and maintenance treatment is recommended at a minimum dose for long-term therapy [17]. Besides, topical steroids, such as budesonide, are also effective in treating non-EoE EGIDs, especially in EoE and EoG, for their local anti-inflammatory agents to the mucosal surface, and now recommended for steroid maintenance therapy to avoid relapses for its low risk of long-term side effects [2, 18]. In some children with EoN or EoC, food allergen Elimination diets may be an option to induce clinical improvement or remission. Still, there is limited data on histologic response and long-term outcomes [19]. Moreover, ensuring adherence to the diet and avoidance of nutritional deficiencies are also problematic for prolonged treatment [20].

In conclusion, when children presenting with peripheral blood eosinophilia and duodenal wall thickening on imaging study, non-EoE EGIDs should be kept in mind for differential diagnosis. Careful examinations of pathologic specimens and monitoring of eosinophil counts are emphasized to avoid misdiagnosis of non-EoE EGIDs, although it is a rare condition. Apart from the initiated therapy with oral prednisone to induce remission, principles for managing non-EoE EGIDs include long-term maintenance therapy, symptoms, and histology monitoring to avoid recurrences and prevent complications.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to our patient and her parents for their willingness to share this case.

Abbreviations

- EGIDs

Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disorders

- EoE

Eosinophilic Esophagitis

- EoG

Eosinophilic gastritis

- EoN

Eosinophilic enteritis

- EoD

Eosinophilic duodenitis

- EoC

Eosinophilic colitis

- GI

Gastrointestinal

- AP

Acute pancreatitis

- EGD

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

- CT

Computed tomography

- MRCP

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

Author contributions

JKY conceived this case report and drafted the initial manuscript. YC and HC interpreted the results and revised the manuscript. FL interpreted ultrasonographic and histopathologic studies and reviewed the manuscript. HYY and WRL revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript as submitted. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

No funding.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the parent of the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Abonia JP, Alexander JA, Arva NC, Atkins D, Attwood SE, Auth MKH, Bailey DD, Biederman L, et al. International Consensus recommendations for Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease nomenclature. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(11):2474–e24842473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papadopoulou A, Amil-Dias J, Auth MK, Chehade M, Collins MH, Gupta SK, Gutierrez-Junquera C, Orel R, Vieira MC, Zevit N et al. Joint ESPGHAN/NASPGHAN guidelines on Childhood Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal disorders beyond Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Koutri E, Papadopoulou A. Eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases in Childhood. Ann Nutr Metab. 2018;73(Suppl 4):18–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jensen ET, Martin CF, Kappelman MD, Dellon ES. Prevalence of Eosinophilic Gastritis, Gastroenteritis, and colitis: estimates from a National Administrative Database. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62(1):36–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saeed SA. Acute pancreatitis in children: updates in epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2020;50(8):100839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uc A, Husain SZ. Pancreatitis in children. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(7):1969–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suzuki S, Homma T, Kurokawa M, Matsukura S, Adachi M, Wakabayashi K, Nozu F, Tazaki T, Kimura T, Matsuura T, et al. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis due to cow’s milk allergy presenting with acute pancreatitis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2012;158(Suppl 1):75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baek MS, Mok YM, Han WC, Kim YS. A patient with eosinophilic gastroenteritis presenting with acute pancreatitis and ascites. Gut Liver. 2014;8(2):224–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Connie D, Nguyen H. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis, ascites, and pancreatitis: a case report and review of the literature. South Med J. 2004;97(9):905–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyngbaek S, Adamsen S, Aru A, Bergenfeldt M. Recurrent acute pancreatitis due to eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Case report and literature review. JOP. 2006;7(2):211–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinte L, Baicus C. Eosinophilic pancreatitis versus pancreatitis associated with eosinophilic gastroenteritis - a systematic review regarding clinical features and diagnosis. Rom J Intern Med. 2019;57(4):284–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JM, Lee KM. Endoscopic diagnosis and differentiation of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Endosc. 2016;49(4):370–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins MH. Histopathologic features of eosinophilic esophagitis and eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43(2):257–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi JS, Choi SJ, Lee KJ, Kim A, Yoo JK, Yang HR, Moon JS, Chang JY, Ko JS, Kang GH. Clinical manifestations and treatment outcomes of eosinophilic gastroenteritis in children. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2015;18(4):253–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee CM, Changchien CS, Chen PC, Lin DY, Sheen IS, Wang CS, Tai DI, Sheen-Chen SM, Chen WJ, Wu CS. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: 10 years experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88(1):70–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang M, Li Y. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: a state-of-the-art review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32(1):64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pineton de Chambrun G, Dufour G, Tassy B, Riviere B, Bouta N, Bismuth M, Panaro F, Funakoshi N, Ramos J, Valats JC, et al. Diagnosis, natural history and treatment of eosinophilic enteritis: a review. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2018;20(8):37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pesek RD, Reed CC, Muir AB, Fulkerson PC, Menard-Katcher C, Falk GW, Kuhl J, Martin EK, Magier AZ, Ahmed F, et al. Increasing rates of diagnosis, substantial Co-occurrence, and variable treatment patterns of Eosinophilic Gastritis, Gastroenteritis, and Colitis based on 10-Year data across a Multicenter Consortium. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(6):984–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lucendo AJ, Serrano-Montalban B, Arias A, Redondo O, Tenias JM. Efficacy of Dietary Treatment for Inducing Disease Remission in Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;61(1):56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basilious A, Liem J. Nutritional management of Eosinophilic gastroenteropathies: Case series from the community. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2011;7(1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.