Abstract

Background

Individualized patient education is one of the new approaches that have attracted much attention in recent years. In line with individualized care, individualized education is designed and implemented based on the learning needs and preferences of each patient. The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of individualized education on the learning needs of patients on hemodialysis (HD).

Methods

In this single-blinded randomized clinical trial, a total of 102 patients were randomly assigned to individualized education or control groups. Patients in the intervention group (n = 51) received individualized education based on their individualized learning needs and preferences. The control group (n = 51) received routine education with brochures. The patient’s learning needs were evaluated by the Patient Learning Needs Scale (PLNS) in three-time points (before the intervention, immediately after the intervention, and three months after the last session of individualized education). Data were analyzed using SPSS software (v.26). A P-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The results showed that the mean scores of total PLNS were not significantly different between the two groups before the intervention (P = 0.77). However, the mean total score of PLNS and the mean scores of seven subscales in the intervention group were lower than the control group immediately and three months after the intervention (P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Implementation of the individualized patient education program can lead to decreased learning needs of patients on HD. Therefore, hemodialysis nurses could use individualized patient education as an effective education to meet the patient’s needs by considering their learning needs.

Trial registration

Iranian Registry of Clinical Trial, IRCT20221031056352N1, Registered on 16/2/2023.

Keywords: Individualized education, Patient education, Learning needs, Hemodialysis, Chronic kidney disease

Background

Kidney failure (KF) is a worldwide health concern marked by a substantial decline in kidney function [1, 2]. Individuals with KF need kidney replacement therapies (KRTs), with hemodialysis (HD) being the most prevalent form of treatment [3, 4].

Patients on HD seem to have inadequate knowledge from both subjective and objective perspectives. This underscores the significance of empowering patients and providing education on their disease and care [5, 6]. Patients undergoing HD experience and suffer many symptoms and complications such as nausea, insomnia, profound fatigue, hypotension, and muscle cramps. Moreover, they should adhere to dietary and fluid restrictions and extensive medication regimens [7, 8]. These patients require education to manage the disease and prevent complications [9]. Patient education has long been an essential part of nursing care [10]. It helps to improve patients’ understanding and knowledge of disease and their self-management [11].

The educational materials given to patients are typically presented in the form of printed brochures or booklets. These materials do not take into account the differences in patients’ characteristics and preferences, as they are presented to all patients using the same format and wording. As a result, illiteracy or lack of motivation among patients may compromise the effectiveness of these educational materials. For example, a patient may have difficulty or misconceptions in understanding medical terms or graphs [12]. According to the evidence, all patients do not have the same capacity and health literacy level and they do not learn the same way. Some people like to learn and understand information through visual materials, diagrams, graphics, and pictures. Others prefer to learn best through participating in hands-on activities, hearing, and writing. Nurses should assess and identify patient needs and try to provide them with the most suitable method of education by considering the preferences of each patient [11].

Providing individualized education is the main solution to overcome these concerns, which emphasizes providing tailored education based on the specific learning needs and health literacy status of each patient [13]. Individualized education is in line with the new approach of individualized care in which nursing care is planned and implemented based on the preferences, beliefs, values, thoughts, perceptions, and needs of each patient. According to this approach, it is proposed that patient education should also be provided in an individualized approach [14]. Providing individualized education requires identifying the educational needs of each patient through effective interaction between nurses and patients [15].

Patients’ knowledge of their disease and treatments does not seem to be sufficient. Hence, attention should be paid to supporting patients with more personalized knowledge [16]. Some studies have shown that patient knowledge of disease and treatment is associated with an increased level of treatment adherence. The success of treatment depends on the adherence to the strictly recommended therapeutic regimen [16–19].

Patients on HD have specific learning needs. Healthcare providers should assess the patients’ needs and try to select effective strategies for meeting their needs. Among health care professionals, nurses are constantly in contact with patients undergoing HD and they can help them to meet their learning needs. Therefore, by providing information and improving patients’ understanding of the disease, nurses have the best position to assess, diagnose, and reduce patients’ learning needs [20]. Today, most educational programs are carried out without considering the preferences, needs, and conditions of each patient [21]. Moreover, the learning needs of patients undergoing HD are often not identified. It seems that the application of new and flexible educational approaches such as individualized education could help to meet the learning needs of patients on HD [22]. According to the best of our knowledge, there are a few studies on the influence of individualized education in patients receiving KRTs. This study aimed to assess the effect of individualized education on the learning needs of patients undergoing HD.

Methods

Study design and setting

This study is a single-blind, two-arm, and parallel-group randomized controlled clinical trial. The study was conducted in the largest dialysis center in Iran (Emam Reza Hemodialysis Center) affiliated with Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

Participant recruitment

The aim of the study was explained to all participants and their willingness to participate in this study was asked. An informed consent form was obtained from all participants. Inclusion criteria for participants were: (a) Patients with end-stage kidney disease (stage 5) based on their medical records, confirmed by a specialized nephrologist, (b) aged over 18 years, (c) Patients who were going HD at least three times a week for at least three months, (d) absence of mental disorders (severe depression and dementia) according to the report of the patient or family or based on the patient’s medical records, (e) Absence of cognitive disorders based on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [22]. The mini-mental state examination (MMSE) is the most commonly applied cognitive test. The MMSE has 19 individual tests of 11 domains covering orientation, registration, attention or calculation (serial sevens or spelling), recall, naming, repetition, comprehension (verbal and written), writing, and construction. The total score range is 0–30 points. The cut-off MMSE score for cognitive impairment varies based on the population studied. Studies have shown that for individuals in the general Iranian population, a score below 23 on the Persian MMSE is indicative of potential cognitive decline (2, 3).

Exclusion Criteria were: (a) Participant’s unwillingness to continue the study, (b) Patients who changed KRT from HD to other treatments (kidney transplantation or peritoneal dialysis) during the study period, (c) Patients who changed their HD center during the study, (d) decreased consciousness of the participant during the study for any reason, and (e) patient participation in another similar study during the study.

The results of a previous study [23] was used for the estimation of sample size. By considering the alpha at 0.05 and power (1-β) at 0.80, a sample size of 47 is required for each two groups using the formula of  . Considering the 10% attrition rate, the sample size considered 51 participants in each group. We also conducted a pilot study to determine the final sample size. In the pilot study by considering µ1=131.01, µ2= 111.99, S1=19.94, S2=21.25, the alpha at 0.05, and power (1-β) at 0.99, the similar sample size (n = 43) was required for each group (total n = 96). We calculated the final sample size of 102 participants by considering 20% attrition rate.

. Considering the 10% attrition rate, the sample size considered 51 participants in each group. We also conducted a pilot study to determine the final sample size. In the pilot study by considering µ1=131.01, µ2= 111.99, S1=19.94, S2=21.25, the alpha at 0.05, and power (1-β) at 0.99, the similar sample size (n = 43) was required for each group (total n = 96). We calculated the final sample size of 102 participants by considering 20% attrition rate.

Randomization and blinding

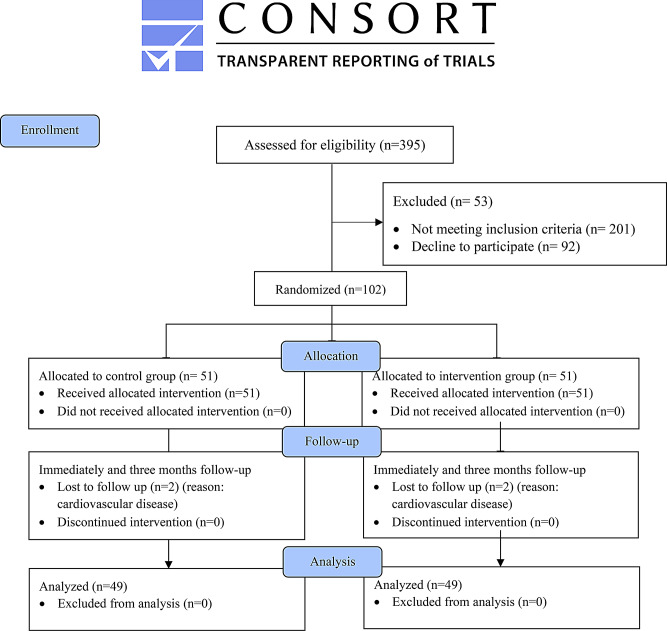

A total of 102 patients were randomly assigned to one of the intervention (individualized education) or control (Educational brochures) groups. The flow chart of the study is shown in Fig. 1. The objectives of the study were explained to all participants and they requested not to participate in similar studies. Randomization was conducted by using block sizes of 4 and 6, with the allocation ratio (1:1) for individualized education and control groups. The Sequentially Numbered, Opaque, Sealed Envelopes (SNOSE) method was used for allocation concealment. An independent staff prepared the envelopes and another independent staff enrolled participants. Participants in the intervention and control groups were not aware of their allocation. However, due to its nature, the trial intervention could not be blind for educator. The allocation sequence was blinded for examiners/assessors. Moreover, the statistician conducting the data analysis was blinded for the group allocation.

Fig. 1.

Trial flow chart

Intervention

Patients in the experimental group participated in an individualized education. Individualized education included the specific educational sessions for each patient. The education provided by a Master of Science student in nursing, with a specialized certificate in HD nursing. At the first session, an individualized assessment session was conducted for each patient. This session lasted approximately 60 min and the baseline data such as demographics, clinical information, and learning needs of each patient were assessed and recorded (T1). Each patient was asked to determine his/her individualized goals on diet, physical activity, proper weight gain, taking medications, and managing complications related to the disease based on their preferences and willingness. Each participant was motivated and supported to set individualized goals.

In the next sessions, each patient received individualized education according to the information obtained in the first session and based on each patient’s needs, education level, age, and cognitive status. The educational content of each session was prepared according to the latest updates of the international guidelines of dialysis (Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI)) [24–27]. The content of individualized education sessions consisted of 4 main components:

The nature of the disease, symptoms, complications, warning signs, follow-up (time to visit a doctor), prognosis, and other KRTs.

Proper diet, fluid, salt, protein, vitamins, physical activity, and proper weight.

The medications that each patient takes (Indication, possible side effects, warning signs).

The complications management (skin and vascular access care, edema and itching, constipation, anemia, etc.)

Each patient had a chance to ask questions, and feedback was obtained from all of the participants. Receiving feedback allowed the educator to ensure the participants’ understanding. So, it was helpful for recognizing misconstruction and helping them for deep understanding of educational content. We had a collaboration with an experienced nephrologist. All patients in both groups daily has been visited by a nephrologist in each dialysis sessions. If specialized questions were raised, a nephrologist was asked to provide appropriate answers to the patient’s questions. Moreover, at the beginning of each session, the materials presented in the previous sessions were reviewed, and some questions were asked from the patient. If the patient could not remember the material presented in the previous sessions, that material was repeated. To ensure the patient’s understanding of the educational materials, feedback was obtained at the end of each session. Patients should answer the questions of the educator correctly. If the participant did not understand the content well, the educator repeated the content until they understood the content.

Each patient was asked about the application of the provided educational materials. If the participant was successful in achieving the goals, strategies such as positive support, effective feedback, and encouragement were implemented to maintain positive behavior. If the participant was not successful in using the educational materials, the obstacles were checked and the appropriate solutions were provided in collaboration with each patient. Moreover, patients could ask their questions at home by calling or by sending an SMS to the educator. Education provided for each participant was documented in each patient’s medical records. The education was provided mainly at the beginning of the HD sessions when the patient connected to the HD machine. Individualized education varied from 3 to 6 sessions for each patient. The duration of each session varied from 10 to 45 min. The educational sessions continued until the patient could express the content correctly and answer the researcher’s questions properly. To maintain the continuity and prevent forgetting of educational materials, at least one educational session was held for each participant every week. To improve patient’s adherence to intervention protocols, each session continued until the patient did not feel tired and did not experience complications such as hypotension. Education was provided in the preferred language of each patient (Persian or Turkish). Simple and understandable sentences were used for each patient. Moreover, we tried not to use specialized medical terminology or incomprehensible terms. To prevent contamination, the participants were requested not to share the individualized education with other patients until the end of the study. Also, the study was conducted in the largest dialysis center in Iran. The space between patients’ beds in this dialysis center is more than four meters and the patient could not hear the education provided to other patients.

The content validity of the individualized education program was evaluated by 10 specialized health care providers including nephrologist, professors in nephrology nursing, hemodialysis supervisors, and experienced nurses. A supervisor of the study who is an expert in the dialysis field and clinical trial checked the study protocol to ensure intervention adherence. The content of the educational programs were provided to 10 healthcare professional working in the field of hemodialysis. The agreement among professionals was carried out using the intra-class correlation (ICC). The results showed ICC > 0.7 among professionals that shows strong agreement. Moreover, the educational materials were assessed using the DISCERN (Quality Criteria for Consumer Health Information) instrument. DISCERN is a valid and reliable tool designed to evaluate the quality and suitability of consumer health information. The results of DISCERN ensured the quality of content provided to the patients [28].

Control group

Participants in the control group received the educational brochures, which are routinely provided by the dialysis center. The contents of the brochures were about the patients’ self-care on diet, vascular access, fluid restrictions, drugs, etc. These brochures were in the Persian language and they may not be understood by illiterate patients or patients with other languages who are not familiar with the Persian language.

Data collection

This study was conducted from 23 October 2023 to 1 February 2024. Data were collected by two measures. Data collection was done by a trained researcher who was not aware of the participants’ allocation into intervention or control groups.

Demographics and clinical information

The baseline data including socio-demographic and clinical information of the patients was collected using demographics and clinical information questionnaires through a face-to-face interview and using medical records. This questionnaire includes participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics, including etiology and the duration of HD. These characteristics were extracted from the patient’s medical records.

Patient learning needs

The patient learning needs scale (PLNS) was used to evaluate the patient’s learning needs [29]. The questionnaire was developed in 1990 by Bubela et al. [29]. It includes 50 items with seven subscales: activities of living (9 items), medications (8 items), treatment and complications (9 items), feelings related to the condition (5 items), community and follow-up (6 items), skin care (5 items), and enhancing the quality of life (QoL) (8 items). Responses to each item were assessed using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (score = 1) to strongly agree (score = 5). The overall score on the scale ranges from 50 to 250. A higher score indicates higher learning needs. Bubela et al. have established the construct validity of this scale. They reported a Cronbach’s α of 0.95 [29]. Moreover, a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82 was calculated in this study.

The PLNS scale was completed for the participants in three time periods including before the intervention (T1), immediately after the intervention (T2), and three months after the intervention (T3).

Data analysis

The collected data was analyzed using SPSS software version 26. To ensure the accuracy of the data, the collected data was checked by two independent researchers after being entered into the software and the range of scores was checked. Interim analyses were performed to test for safety and efficacy of the trial. The intervention had no adverse effects. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to test the normality of data. Dependent-sample t-test, independent-sample t-test, and Repeated measures ANOVA were used to conduct the within-group and between-group analyses. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Sample characteristics

Of the 102 patients entering the study, 98 patients completed the protocol (completion rate, 96.07%). Four participants died of cardiovascular causes during the study (two from the intervention group and two from the control group). No adverse events were reported. The majority of participants in the individualized education group (n = 25 [51.02%]) attended 4 sessions. About 6 patients (12.24%) attended 6 sessions. About 7 patients (14. 28%) participated in 5 sessions and the other 11 patients (22.44%) received 3 sessions.

The mean age of participants in the control and intervention groups were 59.72 ± 13.24 and 58.54 ± 11.13 years, respectively. The demographics of the participants are shown in Table 1. The analysis showed that the two groups were comparable with respect to baseline characteristics, the etiology of disease, and the duration of HD (Table 1).

Table 1.

Homogeneity of baseline characteristics between the groups

| Variables | Categories | Control | Intervention | t or χ2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | Mean ± SD | 59.72 ± 13.24 | 58.54 ± 11.13 | 0.48 | 0.14 |

| Gender | Male | 39 (76.47%) | 33 (64.71%) | 1.70 | 0.19 |

| Female | 12 (23.53%) | 18 (35.29%) | - | - | |

| Education level | Illiterate | 8 (15.69%) | 11 (21.57%) | 1.097 | 0.57 |

| ≤ High school diploma | 36 (70.59%) | 31 (60.78%) | - | - | |

| College | 7 (13.72%) | 9 (17.65%) | - | - | |

| Marital status | Married | 42 (82.35%) | 41 (80.39%) | 0.06 | 0.79 |

| Unmarried/ Divorced/ Widowed | 9 (17.65%) | 10 (19.61%) | - | - | |

| Living in | City | 46 (90.20%) | 45 (88.24%) | 0.10 | 0.75 |

| Village | 5 (9.80%) | 6 (11.76%) | - | - | |

| Occupation | Public employee | 1 (2%) | 3 (5.9%) | 9.48 | 0.09 |

| worker | 0 (0%) | 2 (3.9%) | - | - | |

| Homemaker | 12 (23.5%) | 16 (31.4%) | - | - | |

| Freelancer | 9 (17.6%) | 5 (9.8%) | - | - | |

| Retired | 21 (41.2%) | 11 (21.6%) | - | - | |

| Jobless | 8 (15.7%) | 14 (27.5%) | - | - | |

| Income | Low | 8 (15.69%) | 8 (15.69%) | 0.30 | 0.85 |

| Moderate | 34 (66.66%) | 36 (70.59%) | - | - | |

| High | 9 (7.65%) | 7 (13.72%) | - | - | |

| Etiology | Diabetes | 3 (5.88%) | 7 (13.72%) | 5.35 | 0.25 |

| Hypertension | 20 (39.22%) | 13 (25.49%) | - | - | |

| Diabetes & Hypertension | 18 (35.29%) | 15 (29.41%) | - | - | |

| Others | 10 (19.61%) | 15 (29.41%) | - | - | |

| Duration of HD (yr) | Mean ± SD | 3.84 ± 3.88 | 3.51 ± 2.76 | 0.50 | 0.65 |

SD = Standard deviation, HD = Hemodialysis, yr = Year

Effects of individualized education on PLNS

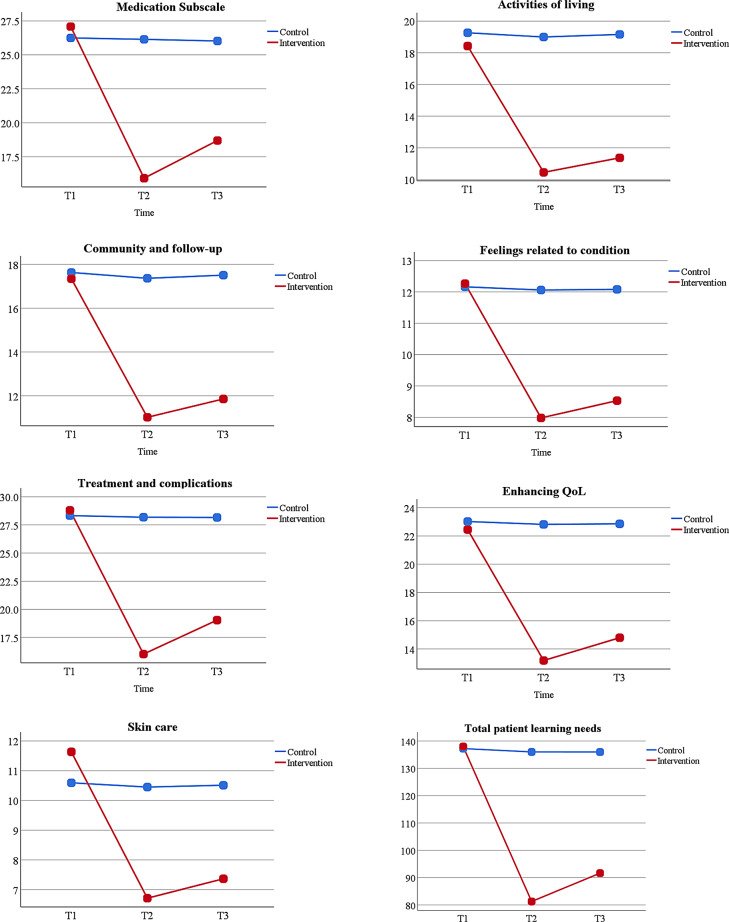

Compared with the control group, participants in the individualized education group showed significant improvements in all dimensions of PLNS at T2 and T3 times (P < 0.05). The details of the comparison in each subscale of the PLNS are shown in the following paragraphs.

Medication

The results of the independent-sample t-test showed that there was no statistically significant difference in the mean score of the medication subscale between the two groups before the intervention (P = 0.34). However, a statistically significant difference was found immediately and three months after the intervention between the two groups (P < 0.001). The results of repeated measures ANOVA also indicated a significant difference in the mean score of the medication subscale during two time points of measurement (T2 and T3) in the intervention group compared to the control group (P < 0.05) (Table 2; Fig. 2). However, according to the within-group analysis, the mean score of medication in the control group showed no significant differences between three-time point (T1, T2, and T3) (P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Comparison of the mean score of the PLNS and its dimensions between the study groups

| Variables | Time of measurement | Control Mean ± SD |

Intervention Mean ± SD |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -Medication | T1 | 26.20 ± 4.85 | 27.11 ± 4.97 | 0.34* |

| T2 | 26.14 ± 4.93 | 15.92 ± 5.70 | < 0.001** | |

| T3 | 26.02 ± 4.87 | 18.69 ± 6.04 | < 0.001** | |

| P-value | > 0.05*** | < 0.05*** | ||

| -Activities of living | T1 | 19.23 ± 4.03 | 18.55 ± 4.85 | 0.44* |

| T2 | 19 ± 4.12 | 10.44 ± 3.61 | < 0.001** | |

| T3 | 19.16 ± 4.18 | 11.36 ± 3.73 | < 0.001** | |

| P-value | > 0.05*** | < 0.05*** | ||

| -Community and follow-up | T1 | 17.60 ± 1.56 | 17.41 ± 1.51 | 0.47* |

| T2 | 17.37 ± 1.60 | 11.02 ± 1.78 | < 0.001** | |

| T3 | 17.51 ± 1.81 | 11.86 ± 1.58 | < 0.001** | |

| P-value | > 0.05*** | < 0.05*** | ||

| -Feelings related to condition | T1 | 12.23 ± 2.11 | 12.25 ± 1.76 | 0.96* |

| T2 | 12.06 ± 2.16 | 7.98 ± 1.61 | < 0.001** | |

| T3 | 12.08 ± 2.15 | 8.53 ± 1.44 | < 0.001** | |

| P-value | > 0.05*** | < 0.05*** | ||

| -Treatment and complications | T1 | 28.21 ± 3.37 | 28.59 ± 3.82 | 0.6* |

| T2 | 28.18 ± 3.29 | 16.02 ± 3.83 | < 0.001** | |

| T3 | 28.16 ± 3.43 | 19.04 ± 4.05 | < 0.001** | |

| P-value | > 0.05*** | < 0.05*** | ||

| -Enhancing QoL | T1 | 23.18 ± 5.33 | 22.51 ± 3.41 | 0.45* |

| T2 | 22.82 ± 5.38 | 13.18 ± 3.20 | < 0.001** | |

| T3 | 22.86 ± 5.33 | 14.79 ± 3.30 | < 0.001** | |

| P-value | > 0.05*** | < 0.05*** | ||

| -Skin care | T1 | 10.57 ± 2.68 | 11.67 ± 3.11 | 0.06* |

| T2 | 10.45 ± 2.75 | 6.71 ± 2.24 | < 0.001** | |

| T3 | 10.51 ± 2.70 | 7.37 ± 2.39 | < 0.001** | |

| P-value | > 0.05*** | < 0.05*** | ||

| Total PLNS | T1 | 137.23 ± 15.82 | 138.10 ± 13.48 | 0.77* |

| T2 | 136.02 ± 15.97 | 81.28 ± 15.20 | < 0.001** | |

| T3 | 136 ± 16.03 | 91.65 ± 15.21 | < 0.001** | |

| P-value | > 0.05*** | < 0.05*** |

SD = Standard deviation, QoL = Quality of life, PLNS = Patient learning needs

T1: pre-test, T2: Immediately after the intervention, T3: three months after the intervention

* Independent sample t-test

** ANOVA test

*** Repeated measures ANOVA

Fig. 2.

Changes in patient learning needs and its dimensions between the two groups across time

Activities of living

Based on the results of the independent-sample t-test, the mean score of activities of living was not significantly different between the two groups before the intervention (T1 time point) (P = 0.44). The results of repeated measures ANOVA showed that the mean score of activities of living in the intervention group was lower than the control group during the two time points of measurement compared to the control group (P < 0.05) (Table 2; Fig. 2).

Community and follow-up

According to the independent-sample t-test, the mean score of the community and follow-up subscale was not significantly different between the two groups before the intervention (T1 time point) (P = 0.47). However, the mean score of community and follow-up in the intervention group showed a significant decrease immediately and three months after the intervention as compared with the control group (P < 0.05) (Table 2; Fig. 2).

Feelings related to the condition

The results showed that the mean scores of feelings related to the condition were not significantly different between the two groups before the intervention (P = 0.96). Within group analysis showed that the mean scores of this subscale in the intervention group showed a significant decrease in two time points (T2 and T3) compared to the T1 time point (P < 0.05). However, there were no significant differences between the three time points within the control group (P > 0.05). The results of repeated measures ANOVA indicated a significant difference in the mean score of feelings related to condition during two-time points of measurement (T2 and T3) in the intervention group compared to the control group (P < 0.05) (Table 2; Fig. 2).

Treatment and complications

According to the independent-sample t-test analysis, there was no significant difference in terms of the mean scores of treatment and complications between the two groups before the intervention (P = 0.6). However, a significant difference was found in the intervention group immediately and three months after the intervention as compared to the control group (P < 0.001). However, the mean score of treatment and complications in the control group showed no significant difference during the three-time points of measurement (P > 0.05) (Table 2; Fig. 2).

Enhancing QoL

The comparison of the mean score of enhancing QoL between the two groups showed no significant difference before the intervention (P = 0.45). However, compared with the control group, a significant decrease was found in the intervention group immediately and three months after the intervention (P < 0.05) (Table 2; Fig. 2).

Skin care

The mean score of the skin care subscale was compared between the two groups. The results of the independent-sample t-test revealed that the mean scores of skin care were not significantly different between the two groups before the intervention (P = 0.06). The results of repeated measures ANOVA indicated a significant difference in the mean score of skin care in the intervention group during two-time points of measurement compared with the control group (P < 0.05) (Table 2; Fig. 2).

Total PLNS

Finally, the results showed that the mean scores of total PLNS were not significantly different between the two groups before the intervention (P = 0.77). However, the mean total score of PLNS in the intervention group was lower than the control group immediately and three months after the intervention (P < 0.001) (Table 2; Fig. 2).

Discussion

This study investigated the effect of individualized education on patient learning needs among patients undergoing HD. It was found that individualized education could improve patient learning needs in the seven dimensions of PLNS, including medication, activities of living, community and follow-up, feelings related to condition, treatment & complications, enhancing QoL, and skin care immediately and three months after the intervention. Therefore, we need to make changes in patient education strategies and utilize effective educational methods in patients undergoing HD by considering each patient’s needs. Several studies emphasize the importance of the patient-centered approach in providing educational programs for patients undergoing HD [19, 30–35]. Havas et al. support the idea of an individualized patient education approach. They argue that a “one-size-fits-all” approach is not a suitable method of self-management in patients with KF. They recommend a person-centered approach and tailored self-management support for these patients [36]. According to our result, patients on HD could benefit from individualized education by limiting misconceptions about the condition and improving their knowledge and information.

Our results showed that individualized education helps patients to meet the learning needs related to the medication immediately and three months after the intervention. Individualized education empowers patients by equipping them with the specific knowledge and skills necessary to understand their medications. A Study conducted by Eshiet et al. showed that patients who received education on medication had a higher score in medication knowledge assessments compared to those who did not receive such education [37]. Also, IU et al. indicated that educating patients on medication in their native language is more effective and could linked to reduced medication errors and improved adherence, which is crucial in managing chronic conditions [38].

Additionally, Alkatheri et al. found that patient education significantly improve patients’ knowledge about their medications, leading to higher levels of satisfaction. Patients’ Knowledge of the medications’ side effects proved to be the most difficult task for the participants [39].

Based on the results, individualized education improved the learning needs on activities of living in patients on HD immediately and three months after the intervention. This finding was supported by Vijay & Kang who showed that patient education is a strategy that helps patients to make choices and lifestyle changes through setting goals, problem-solving, and feedback. It emphasizes patients’ responsibility and role in disease management [40]. Impairment in activities of living is a problem that presents early in the life of chronically ill patients, as in chronic kidney disease, including those with kidney failure undergoing HD [41]. Patients undergoing HD have many problems including nausea, vomiting, hypotension, headache, and muscle spasms. HD leads to lifestyle changes for patients, and the time required for HD reduces the time for social activities [42]. Therefore, it is crucial to implement educational strategies to assist these patients in achieving better clinical outcomes, independently carrying out daily activities, and following educational recommendations [30].

The results of the findings showed that individualized education also resulted in a significant decrease in the mean score of the feelings related to condition dimension in the intervention group immediately and three months after the intervention. Patients often experience anger, fear, and despair upon diagnosis, but these feelings could be diminished with patient education and counselling [43]. Lazarus and Folkman proposed a model of management of stress and coping that underscores the role of perceived knowledge and understanding in emotional responses to health conditions. They suggest that when patients receive comprehensive information tailored to their specific needs, their knowledge to cope with the emotional stress of their condition significantly improves [44].

According to the results, individualized education leads to a significant decrease in QoL learning needs of patients on HD immediately and three months after the intervention. Previous studies showed that individualized education helps to correct bad habits and improve patient’s knowledge and ability to monitor their conditions and treatment compliance, thereby improving QoL and reducing complications [45, 46]. Alikari et al. showed that nurse-led educational intervention leads to a significant increase in the QoL of patients undergoing HD [34]. Similar findings were found by other studies conducted in a population of Iranian patients undergoing HD [47–50].

Based on the results, individualized education leads to decreased skin care learning needs immediately and three months after the intervention. In line with our findings, Baraz et al. conducted a study to investigate the effect of self-care education based on Orem theory on the physical problems of patients undergoing HD. They found that self-care education was effective in controlling skin itching and reducing local vascular access problems [51].

Before the intervention, both groups had similar levels of total learning needs and their dimensions. Individualized education improved learning needs, in the seven dimensions of medications, activities of living, community and follow-up, feelings related to condition, treatment and complications, enhancing QoL, and skin care in the intervention group immediately and three months after the intervention. Several studies have shown the positive effect of educational programs on the level of learning needs [17, 19, 34]. Also, a study conducted by Başer & Mollaoğlu emphasized that the knowledge levels of patients undergoing HD treatment about medication use, activities of daily living, and fistula care should be checked regularly. Therefore, patient-centered educational programs should be planned and prepared to ensure the continuity of education [52]. In line with our results, Inkeroinen et al. highlight the importance of patients’ individual needs in providing educational strategies for patients with KF [5].

Individualized patient education can help healthcare providers to tailor their teaching based on each patient unique learning need. Moreover, the seven dimensions of patient learning needs was related to patients’ behavior and life-style, including medication, activities of living, community and follow-up, feelings related to condition, treatment & complications, enhancing QoL, and skin care. Therefore, providing information on this topic could help to improve patients’ knowledge and help to meet their unique learning needs. In addition, the materials provided for patients using the latest updates of the international guidelines of dialysis (Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI)), covered the all dimensions of patients learning needs, because we provided some information about medication, activities of living, community and follow-up, feelings related to condition, treatment & complications, enhancing QoL, and skin care.

Strengths and limitations

The major strength of this study is preparing a new approach to patient education. However; there are several limitations. Due to the nature of the intervention, the trial allocation could not be blind for educator. Another limitation of this study was the short-term follow-up period due to grant limitations. Moreover, this study was conducted in a single center. Therefore, conducting a multicenter trial is recommended in future studies.

Conclusions

This study aimed to assess the effect of individualized education on patient learning needs among patients undergoing HD. The results indicated that individualized education could help to meet the learning needs of patients undergoing HD. Individualized education improves patient understanding by recognizing the unique educational needs of each patient and preparing information based on the patients’ needs and preferences. In line with our result, it is suggested to incorporate the individualized education at the early stage of kidney failure. To achieve this goal, the development of multidisciplinary educational teams within the HD units could be helpful.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Abbreviations

- KF

Kidney failure

- KRTs

Kidney replacement therapies

- HD

Hemodialysis

- PLNS

Patient learning needs scale

- QoL

Quality of life

Author contributions

SLS, MG, and HTKh participated in the study conception and design. SLS, MG, and HTKh specifically designed the statistical analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding

Tabriz University of Medical Sciences funded this study and provided financial support (code:1401.960).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1401.960). This trial was registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trial on 16/2/2023 (Registration number: IRCT20221031056352N1). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The patients assured that the collected information will be confidential and will only be used for research and the results of the study will be provided to them.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Thurlow JS, Joshi M, Yan G, Norris KC, Agodoa LY, Yuan CM, et al. Global epidemiology of end-stage kidney disease and disparities in kidney replacement therapy. Am J Nephrol. 2021;52(2):98–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamidi M, Roshangar F, Khosroshahi HT, Hassankhani H, Ghafourifard M, Sarbakhsh P. Comparison of the effect of linear and step-wise sodium and ultrafiltration profiling on dialysis adequacy in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transplantation. 2020;31(1):44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vélez-Bermúdez M, Christensen AJ, Kinner EM, Roche AI, Fraer M. Exploring the relationship between patient activation, treatment satisfaction, and decisional conflict in patients approaching end-stage renal disease. Ann Behav Med. 2019;53(9):816–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmadpour B, Ghafourifard M, Ghahramanian A. Trust towards nurses who care for haemodialysis patients: a cross-sectional study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2020;34(4):1010–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inkeroinen S, Koskinen J, Karlsson M, Kilpi T, Leino-Kilpi H, Puukka P et al. Sufficiency of knowledge processed in patient education in dialysis care. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2021:1165–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Mirmazhari R, Ghafourifard M, Sheikhalipour Z. Relationship between patient activation and self-efficacy among patients undergoing hemodialysis: a cross-sectional study. Ren Replace Therapy. 2022;8(1):40. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nilsson EL. Patients’ experiences of initiating unplanned haemodialysis. J Ren care. 2019;45(3):141–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reid C, Seymour J, Jones C. A thematic synthesis of the experiences of adults living with hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrology: CJASN. 2016;11(7):1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yangöz ŞT, Özer Z, Boz İ. Comparison of the effect of educational and self-management interventions on adherence to treatment in hemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(5):e13842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fereidouni Z, Sarvestani RS, Hariri G, Kuhpaye SA, Amirkhani M, Kalyani MN. Moving into action: the master key to patient education. J Nurs Res. 2019;27(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergh A-L, Friberg F, Persson E, Dahlborg-Lyckhage E. Registered nurses’ patient education in everyday primary care practice: managers’ discourses. Global Qualitative Nurs Res. 2015;2:2333393615599168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cawsey A, Grasso F, Paris C. Adaptive information for consumers of healthcare. The adaptive web: methods and strategies of web personalization. 2007:465 – 84.

- 13.Hawkins RP, Kreuter M, Resnicow K, Fishbein M, Dijkstra A. Understanding tailoring in communicating about health. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(3):454–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ertürk EB, Ünlü H. Effects of pre-operative individualized education on anxiety and pain severity in patients following open-heart surgery. Int J Health Sci. 2018;12(4):26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suhonen R, Charalambous A. The concept of individualised care. Individualized care: Springer; 2019. pp. 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alikari V, Tsironi M, Matziou V, Tzavella F, Stathoulis J, Babatsikou F, et al. The impact of education on knowledge, adherence and quality of life among patients on haemodialysis. Qual Life Res. 2019;28:73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alikari V, Matziou V, Tsironi M, Theofilou P, Giannakopoulou N, Tzavella F, et al. editors. Patient Knowledge, Adherence to the Therapeutic Regimen, and Quality of Life in Hemodialysis: Knowledge, Adherence, and Quality of Life in Hemodialysis. GeNeDis 2020: Geriatrics; 2021: Springer. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Miyata KN, Shen JI, Nishio Y, Haneda M, Dadzie KA, Sheth NR, et al. Patient knowledge and adherence to maintenance hemodialysis: an international comparison study. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2018;22:947–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dsouza B, Prabhu R, Unnikrishnan B, Ballal S, Mundkur SC, Sekaran VC, et al. Effect of educational intervention on knowledge and level of adherence among hemodialysis patients: a randomized controlled trial. Global Health Epidemiol Genomics. 2023;2023:e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madar H, Bar-Tal Y. The experience of uncertainty among patients having peritoneal dialysis. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(8):1664–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang L, Guo H, Xiu L, Wang H. Efficacy of individualized education in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized clinical study protocol. Medicine. 2020;99(50). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Delasobera BE, Goodwin TL, Strehlow M, Gilbert G, D’Souza P, Alok A, et al. Evaluating the efficacy of simulators and multimedia for refreshing ACLS skills in India. Resuscitation. 2010;81(2):217–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.John JR, Tannous WK, Jones A. Outcomes of a 12-month patient-centred medical home model in improving patient activation and self-management behaviours among primary care patients presenting with chronic diseases in Sydney, Australia: a before-and-after study. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lok CE, Huber TS, Lee T, Shenoy S, Yevzlin AS, Abreo K, et al. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for vascular access: 2019 update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(4):S1–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikizler TA, Burrowes JD, Byham-Gray LD, Campbell KL, Carrero J-J, Chan W, et al. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for nutrition in CKD: 2020 update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76(3):S1–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daugirdas JT, Depner TA, Inrig J, Mehrotra R, Rocco MV, Suri RS, et al. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for hemodialysis adequacy: 2015 update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(5):884–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inker LA, Astor BC, Fox CH, Isakova T, Lash JP, Peralta CA, et al. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(5):713–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, Gann R. DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53(2):105–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bubela N, Galloway S, McCay E, McKibbon A, Nagle L, Pringle D, et al. The patient learning needs scale: reliability and validity. J Adv Nurs. 1990;15(10):1181–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kameel Zatton H, Mohamed Taha N, Ali Metwaly E. Effect of Educational guidelines on Knowledge, health care practices and dependency level for patients undergoing hemodialysis. Egypt J Health Care. 2023;14(1):594–610. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee H, Park HH, Jo I-Y, Jhee JH, Park JT, Lee SM. Effects of intensive individualized nutrition counseling on nutritional status and kidney function in patients with stage 3 and 4 chronic kidney disease. J Ren Nutr. 2021;31(6):593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mansouri S, Jalali A. Educational supportive group therapy and the quality of life of hemodialysis patients. 2020;14:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Fadlalmola HA, Elkareem EMA. Impact of an educational program on knowledge and quality of life among hemodialysis patients in Khartoum state. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2020;12:100205. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alikari V, Tsironi M, Matziou V, Tzavella F, Stathoulis J, Babatsikou F et al. The impact of education on knowledge, adherence and quality of life among patients on haemodialysis. Qual Life Res. 2019;28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Mahjubian A, Bahraminejad N, Kamali K. The effects of group discussion based education on the promotion of self-management behaviors in hemodialysis patients. J Caring Sci. 2018;7(4):225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Havas K, Douglas C, Bonner A. Meeting patients where they are: improving outcomes in early chronic kidney disease with tailored self-management support (the CKD-SMS study). BMC Nephrol. 2018;19(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eshiet UI, Igwe CN, Ogbeche AO. Comparative assessment of medication knowledge among ambulatory patients: a cross-sectional study in Nigeria. Exploratory Res Clin Social Pharm. 2024;13:100388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.IU H, MY M. Patients’ knowledge about medicines improves when provided with written compared to verbal information in their native language. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(10):e0274901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alkatheri AM, Albekairy AM. Does the patients’ educational level and previous counseling affect their medication knowledge? Annals Thorac Med. 2013;8(2):105–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vijay V, Kang HK. Efficacy of nurse-led interventions on dialysis-related diet and fluid non-adherence and morbidities: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. J Global Health Rep. 2019;3:e2019083. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gutiérrez-Peredo GB, Martins MTS, da Silva FA, Lopes MB, Lopes GB, Lopes AA. Functional dependence and the mental dimension of quality of life in Hemodialysis patients: the PROHEMO study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khan S, Ahmad I. Impact of hemodialysis on the wellbeing of chronic kidney diseases patients: a pre-post analysis. Middle East Curr Psychiatry. 2020;27:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nurhaeda N. Gambaran psychological well being pada pasien gagal ginjal kronik yang menjalani terapi Hemodialisa. Psikoislamika: Jurnal Psikologi dan Psikologi Islam. 2023;20(1):559 – 67.

- 44.Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Gruen RJ, DeLongis A. Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1986;50(3):571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu R, Feng S, Quan H, Zhang Y, Fu R, Li H. Effect of Self-Determination Theory on Knowledge, Treatment Adherence, and Self-Management of Patients with Maintenance Hemodialysis. Contrast media & molecular imaging. 2022;2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Albatineh AN, Ibrahimou B. Factors associated with quality-of-life among Kuwaiti patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Psychol Health Med. 2019;24(8):1005–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abianeh NA, Zargar SA, Amirkhani A, Adelipouramlash A. The effect of self-care education through teach back method on the quality of life in hemodialysis patients. Néphrologie Thérapeutique. 2020;16(4):197–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mansouri S, Jalali A, Rahmati M, Salari N. Educational supportive group therapy and the quality of life of hemodialysis patients. Biopsychosoc Med. 2020;14:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Naseri-Salahshour V, Sajadi M, Nikbakht-Nasrabadi A, Davodabady F, Fournier A. The effect of nutritional education program on quality of life and serum electrolytes levels in hemodialysis patients: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(9):1774–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhianfar L, Nadrian H, Asghari Jafarabadi M, Espahbodi F, Shaghaghi A. Effectiveness of a multifaceted educational intervention to enhance therapeutic regimen adherence and quality of life amongst Iranian hemodialysis patients: a randomized controlled trial (MEITRA study). J Multidisciplinary Healthc. 2020:361–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Baraz S, Mohammadi I, Boroumand B. A comparative study on the effect of two methods of self-care education (direct and indirect) on quality of life and physical problems of hemodialysis patients. J Arak Univ Med Sci. 2006;9(1):71–22. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Başer E, Mollaoğlu M. The effect of a hemodialysis patient education program on fluid control and dietary compliance. Hemodial Int. 2019;23(3):392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.