Abstract

Background

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) afflict nearly 2 billion people worldwide and are caused by various pathogens, such as bacteria, protozoa, and trypanosoma, prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions. Among the 17 NTDs recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO), protozoal infections caused by Plasmodium, Entamoeba, Leishmania, and Trypanosoma are particularly prominent and pose significant public health. Indonesia, endowed with a rich biodiversity owing to its tropical climate, harbors numerous plant species with potent biological activities that hold promise for therapeutic interventions. Hence, efforts have been directed towards exploring Indonesian plant extracts and isolated compounds for their potential in combating protozoal diseases.

Methods

This study evaluated the antiprotozoal properties of 48 plant extracts sourced from the Cratoxylum, Diospyros, and Artocarpus genera. These extracts were screened using cell-based assays against Plasmodium falciparum (Pf), Entamoeba histolytica (Eh), Leishmania donovani (Ld), Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense (Tbr), and Trypanosoma cruzi (Tc).

Results

Extracts derived from the roots of Cratoxylum arborescens, obtained through dichloromethane extraction, exhibited significant activity against protozoa, with an IC50 value ranging from 0.1 to 8.2 µg/mL. Furthermore, cochinchinone C was identified as an active compound capable of inhibiting the growth of Pf, Eh, Ld, and Tbr, Tc trypomastigote, and Tc epimastigote with IC50 values of 5.8 µM, 6.1 µM, 0.2 µM, 0.1 µM, 0.7 µM, and 0.07 µM, respectively. Cochinchinone C is the first compound reported to exhibit activity against protozoal neglected tropical diseases, showing low cytotoxicity with a selectivity index greater than 10 when tested against carcinoma and normal cell lines. This suggests indicating its potential as a candidate for further drug development. This is the first report of cochinchinone C’s activity against these protozoans.

Conclusion

These findings establish cochinchinone C as a strong candidate for antiprotozoal drug development, highlighting the untapped therapeutic potential of Indonesia’s rich plant biodiversity.

Keywords: Antiprotozoal, Natural products, Neglected tropical disease, Cochinchinone C

Introduction

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are infectious illnesses affecting nearly 2 billion individuals caused by various pathogens, significantly impacting public health, especially in poverty-stricken tropical and subtropical regions. This study specifically targets protozoal NTDs, including Chagas disease, leishmaniasis, and African trypanosomiasis, highlighting their unique challenges and the urgent need for improved management and treatment strategies [1, 2]. Protozoal and helminthic NTDs necessitate substantial efforts for management and preventive chemotherapy. However, the development of new, non-drug-resistant treatments could be improved by financial constraints. Consequently, WHO introduced a new roadmap for NTDs spanning 2021–2030, aiming to expedite drug research, discovery, and innovation to control and eliminate NTDs by 2030. To foster innovation in NTDs treatment, plant-derived therapeutics will be support the WHO’s goal by providing potential solutions from biodiversity [2, 3].

Protozoan parasites pose significant health risks, particularly to individuals with compromised cellular immunity. These parasites include E. histolytica, Giardia lamblia, L. donovani, and Trypanosoma brucei, causing diseases such as Chagas disease, African trypanosomiasis, amebiasis, leishmaniasis [4, 5]. Meanwhile, P. falciparum caused malaria disease, in particular, accounts for the highest number of cases, with millions suffering from severe cases and hundreds of thousands of fatalities annually [6]. However, discovering novel compounds for parasitic diseases is infrequent, and existing treatments may face resistance or toxicity issues [7].

An ethnopharmacological approach was carried out in several research to evaluate the medicinal plant extracts for antiprotozoal activity. Plant-based compounds become attractive for drug discovery as learned from discovering antimalarial drugs derived from plants, including quinine isolated from Chinchona bark and artemisinin from Artemisia annua herb [8].

Indonesia, recognized as the second most biodiverse country globally after Brazil according to the Global Biodiversity Index 2022, holds immense potential for drug discovery [9]. The country’s tropical climate fosters a rich array of plant species with promising biological activities suitable for therapeutic applications. Cratoxylum, a tropical plant belonging to the Hypericaceae family, contains xanthone compounds known for their antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, anti-parasitic, and antioxidant properties [10–12]. Diospyros belonging to Ebenaceae family, have been described to have pharmacological activity such as antioxidant, neuroprotective, antibacterial, antiviral, antiprotozoal, antifungal, antiinflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic [13]. Meanwhile, Artocarpus belonging to Moraceae family, traditionally used for treatment against inflammation, malarial fever, diarrhoea, diabetes and tapeworm infection [14]. In this study, we systematically evaluate the antiprotozoal activity of 48 plant extracts from the Cratoxylum, Diospyros, and Artocarpus genera, targeting key protozoan pathogens of global health concern including Plasmodium falciparum (Pf), Entamoeba histolytica (Eh), Leishmania donovani (Ld), Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense (Tbr), and Trypanosoma cruzi (Tc). Additionally, cochinchinone C is the first compound isolated from the root of Cratoxylum arborescens with potential antiprotozoal activity and low toxicity against human and normal cell lines.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Specimens of Cratoxylum genus from various plant parts (leaves, stems, twigs, and roots) were collected in Muara Teweh, Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Leaves of Diospyros and Artocarpus genera were collected in Purwodadi, Pasuruan, East Java, Indonesia. Plant identification was taken by a Botanist, Mr. Rony Irawanto, S.Si., M.T in Purwodadi Botanical Garden, Indonesian Institute of Science, East Java, Indonesia, with determination letter number No: B-108/IPH.06/AP.01/II/2020. These specimens, detailed in Table 1, were stored at the Natural Product Medicine and Development (NPMRD) Laboratory, Institute of Tropical Disease, Universitas Airlangga. Cratoxylum, Diospyros, and Artocarpus were specifically chosen for this study based on the previous reported study and their ethnopharmacologically used [8, 10, 13, 14].

Table 1.

List of plant species extracted for antiprotozoal test and antiprotozoal activity

| No. | Family | Species | Plant’s part | Extract codes | Pf IC50 (µg/mL) | Eh IC50 (µg/mL) | Ld IC50 (µg/mL) | Tbr IC50 (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hipericaceae | Cratoxylum rigidum (Cr) | Stem | Cr.SH | > 10 | 69.7 | 20.1 | 9.2 |

| 2 | Cr.SD | > 10 | > 100 | > 100 | 38.1 | |||

| 3 | Cr.SM | > 10 | > 100 | > 100 | > 100 | |||

| 4 | Cratoxylum cochinchinense (Cc) | Stem | Cc.SH | > 10 | 66.2 | 66.6 | 21.9 | |

| 5 | Cc.SD | > 10 | > 100 | 5.3 | 3.1 | |||

| 6 | Cc.SM | > 10 | > 100 | > 100 | 28.7 | |||

| 7 | Twig | Cc.TH | > 10 | > 100 | 20.9 | 7.0 | ||

| 8 | Cc.TD | > 10 | > 100 | 45.9 | 18.7 | |||

| 9 | Cc.TM | > 10 | > 100 | > 100 | 30.4 | |||

| 10 | Cratoxylum formosum (Cf) | Stem | Cf.SH | > 10 | > 100 | 38.8 | 29.3 | |

| 11 | Cf.SD | > 10 | > 100 | 38.2 | 14.1 | |||

| 12 | Cf.SM | > 10 | > 100 | > 100 | 30.5 | |||

| 13 | Cratoxylum arborescens (Ca) | Root | Ca.RH | > 10 | 49.4 | 6.5 | 3.7 | |

| 14 | Ca.RD | 0.1 | 22.0 | 2.8 | 2.9 | |||

| 15 | Ca.RM | > 10 | > 100 | 69.8 | 37.3 | |||

| 16 | Twig | Ca.TH | > 10 | > 100 | 9.9 | 10.7 | ||

| 17 | Ca.TD | 6.0 | > 100 | 1.3 | 6.4 | |||

| 18 | Ca.TM | > 10 | > 100 | 58.7 | 44.6 | |||

| 19 | Cratoxylum glaucum (Cg) | Stem | Cg.SH | > 10 | > 100 | > 100 | 26.1 | |

| 20 | Cg.SD | > 10 | > 100 | 43.2 | 32.1 | |||

| 21 | Cg.SM | > 10 | > 100 | 25.6 | 25.9 | |||

| 22 | Leaves | Cg.LH | 6.1 | > 100 | > 100 | 18.2 | ||

| 23 | Cg.LD | 2.1 | > 100 | 8.1 | 0.7 | |||

| 24 | Cg.LM | 4.5 | > 100 | 24.4 | 1.3 | |||

| 25 | Root | Cg.RH | > 10 | > 100 | > 100 | 16.1 | ||

| 26 | Cg.RD | > 10 | > 100 | > 100 | 23.5 | |||

| 27 | Cg.RM | 4.4 | > 100 | > 100 | 34.7 | |||

| 28 | Twig | Cg.TH | > 10 | > 100 | 18.5 | 6.6 | ||

| 29 | Cg.TD | > 10 | > 100 | > 100 | 6.5 | |||

| 30 | Cg.TM | > 10 | > 100 | 48.5 | 6.8 | |||

| 31 | Cratoxylum sumatranum (Cs) | Twig | Cs.TH | > 10 | > 100 | 24.6 | 11.0 | |

| 32 | Cs.TD | 0.3 | 75.3 | 1.2 | 3.2 | |||

| 33 | Cs.TM | > 10 | > 100 | 23.1 | 5.9 | |||

| 34 | Ebenaceae | Diospyros malabarica (Dm) | Leaves | Dm.LH | > 10 | > 100 | > 100 | 16.2 |

| 35 | Dm.LD | > 10 | > 100 | > 100 | > 100 | |||

| 36 | Dm.LM | > 10 | > 100 | > 100 | > 100 | |||

| 37 | Diospyros celebica (Dc) | Leaves | Dc.LH | > 10 | > 100 | > 100 | > 100 | |

| 38 | Dc.LD | > 10 | > 100 | > 100 | > 100 | |||

| 39 | Dc.LM | > 10 | > 100 | > 100 | > 100 | |||

| 40 | Moraceae | Artocarpus heteropylus (Ah) | Leaves | Ah.LH | > 10 | > 100 | > 100 | > 100 |

| 41 | Ah.LD | > 10 | > 100 | 47.2 | 19.1 | |||

| 42 | Ah.LM | > 10 | > 100 | > 100 | > 100 | |||

| 43 | Artocapus altilis (Aa) | Leaves | Aa.LH | > 10 | > 100 | > 100 | 14.6 | |

| 44 | Aa.LD | 8.6 | > 100 | 18.2 | 6.1 | |||

| 45 | Aa.LM | > 10 | > 100 | 36.1 | 6.3 | |||

| 46 | Artocarpus camansii (Ac) | Leaves | Ac.LH | > 10 | > 100 | > 100 | 42.9 | |

| 47 | Ac.LD | 8.6 | > 100 | > 100 | 11.1 | |||

| 48 | Ac.LM | > 10 | > 100 | 27.6 | 6.2 |

S: stem; T: twig; R: root; L: leaves; H: n-hexane extract; D: dichloromethane extract; M: methanol extract. Pf: P. falciparum, Eh: E. histolytica, Ld: L. donovani, Tbr: T. b. rhodesiense, Tc-t: T. cruzi trypomastigote, Tc-e: T. cruzi epimastigote

Extractions and fractionations

A multilevel extraction approach was employed, utilizing non-polar to polar solvents. Approximately 250 g of mashed plant parts were successively extracted with n-hexane, dichloromethane, and methanol to yield respective extracts (as listed in Table 1) for bioactivity evaluations against various parasites. Promising extracts identified through initial screening were further extracted on a larger scale which was dichloromethane extracts derived from the Root of Cratoxylum arborescens (Ca.RD). For this, 1 kg of mashed plant parts underwent the same extraction process to obtain sufficient extract for subsequent purification. Active extract separation was achieved via Vacuum Liquid Chromatography (VLC) using Silica gel 60 and a gradient solvent of n-hexane and dichloromethane (100%-0%). Ten fractions (Ca.RD-D1-Ca.RD-D10) obtained were then subjected to parasite testing. The yields of ten fractions were shown as Table 2. Purification of Ca.RD-D7 by cristallization was resulted on Compound (1). Fraction and compound profiles were monitored using thin-layer chromatography (TLC) with visualization under UV at 254 nm and 366 nm, employing a spray reagent of 10% H2SO4.

Table 2.

Antiprotozoal activities of selected extract, fractions, compound (1), and standard drugs

| Extract/fractions code | Yield (%) | Activity against protozoa (IC50 µg/mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. falciparum | E. histolytica | L. donovani | T. brucei rhodesiense | ||

| Ca.RD | 0.357 | 0.1 | 8.2 | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| Ca.RD-D1 | 0.007 | inactive | inactive | inactive | Inactive |

| Ca.RD-D2 | 0.003 | inactive | inactive | inactive | 10.3 |

| Ca.RD-D3 | 0.004 | 6.2 | inactive | 9.5 | 1.7 |

| Ca.RD-D4 | 0.008 | 6.6 | inactive | inactive | 3.5 |

| Ca.RD-D5 | 0.009 | 6.0 | inactive | 9.6 | 1.3 |

| Ca.RD-D6 | 0.008 | 0.8 | 4.4 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| Ca.RD-D7 | 0.009 | 5.8 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Ca.RD-D8 | 0.003 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 0.6 |

| Ca.RD-D9 | 0.010 | 3.3 | inactive | inactive | inactive |

| Ca.RD-D10 | 0.242 | 1.9 | 6.8 | 0.7 | inactive |

| Compound (1) | 0.005 | 2.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Metronidazole | - | 2.6 | - | - | |

| Amphotericin B | - | - | 0.3 | - | |

| Pentamidine | - | - | - | 0.06 | |

| Chloroquine | 1.8 | - | - | - | |

Data was presented as a mean of triplicate; inactive data means the IC50 is more than 10 µg/mL

Identification of compound

Isolated compound structure identification relied on NMR spectra data (1H and 13C) compared to references. Chemical shifts of the compound in deuterated chloroform (CdCl3) were recorded at 400 MHz NMR (1H) and 100 MHz (13C) using NMR JEOL ECS-400.

Organism and culture

P. falciparum strain 3D7 was cultured in RPMI-1640 medium at 37 °C under mixed gas (5% O2, 5% CO2, and 90% N2). E. histolytica clonal strain HM-1:IMSS cl6 [15] trophozoites were axenically cultured in Diamond’s BI-S-33 medium at 35.5 °C. L. donovani axenic amastigote clumps were cultured in complete SM media [16], T. b. rhodesiense strain IL-1501 was cultured in HMI-9 [17], T. cruzi strain TcLuc2 grown in monolayers of mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (3T3) was cultured in DMEM without phenol red at 37 °C under a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere, while T. cruzi epimastigote stage was cultured in liver infusion/tryptone (LIT) medium at 28 °C [18]. Several cell lines, such as human hepatoma cells (Huh7 [19] and HepG2 [20]), baby hamster kidney-21 (BHK-21) [21], and African green monkey kidney (Vero) cell lines [22], were cultured in DMEM with phenol red at 37 °C under a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

In vitro evaluation of antiprotozoal activity

Activity against Plasmodium falciparum

Antiplasmodial activity of plant extracts, fractions, and compounds was assessed against synchronous P. falciparum strain 3D7 using the Plasmodium lactate dehydrogenase (pLDH) assay with modifications by Makler [23]. Asynchronous asexual parasites were synchronized using 5% (w/v) D-sorbitol. The level of parasitemia was determined by light microscopy. The stock culture was diluted with a complete RPMI medium and 50% red blood cell (RBC) to start at 2% hematocrit and 0.3% parasitemia. Samples were dissolved in DMSO, while chloroquine diphosphate (positive control) was dissolved in distilled water. Stock solutions were prepared at 10 µg/mL for screening, with serial dilution ranging from 0.01 to 50 µg/mL for determining IC50 values. One hundred microliter cultures containing different concentrations of the compounds were dispensed into 96 well plates. The maximum concentration of DMSO in each well was 0.5%. The assay plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 72 h in a 5% CO2, 90% N2, and 5% O2 atmosphere. Following the incubation, they were frozen at -30 °C overnight to lyse the red blood cells. Plates were thawed at room temperature for at least 1 h before starting the assay. Briefly, a solution to assess parasites LDH activity containing 50 mM sodium L-lactate, 0.25% Triton X-100, 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 µM APAD, 240 µM NBT, and 1 U/mL diaphorase was prepared. Immediately, 90 µL of solution was dispensed into the plates and were shaken to ensure mixing. After 30 min of incubation at room temperature in the dark, absorbance was measured at 650nM using a Promega microplate reader. This assay was performed in triplicate (n = 3).

Activity against Entamoeba histolytica

Confluent trophozoites of E. histolytica clonal strains HM-1:IMSS cl6 were utilized for testing, employing an extract dissolved in 50% DMSO. A density of 5 × 103 cells/well was seeded into 96-well plates. Metronidazole served as the positive control drug known to inhibit E. histolytica growth. Serially diluted extract (2 µL) was added to each well containing 200 µL of E. histolytica and then incubated anaerobically at 35.5 °C for 48 h. Subsequently, 10% WST-1 in OPTI-MEM was introduced to each well, with 100 µL of media removed [24]. After a 30-minute incubation, absorbance readings were taken at 450 nm using a Victor Nivo plate reader. The percentage inhibition was calculated using the formula:

|

The IC50 value, indicative of the concentration required to inhibit parasite growth by 50%, was determined using the GraphPad Prism Version 8.3.1 (332) application. A < 10 µg/mL value suggests the extract’s potential to inhibit parasite growth effectively.

Activity against Leishmania donovani

L. donovani axenic amastigote clumps were collected from each flask at 37 °C under a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere [16]. Then centrifuged at 1,200 rpm for 10 min at room temperature. The supernatant was discarded, and the clot cells pellet was resuspended with a 6 mL complete SM medium. Resuspending was repeated using the needle twice to make the cells not agglomerate when inserted into the 96 well plates. Amphotericin B was performed as the positive control. A total of 1 × 106 cells/mL were added to each well except for the control medium, and then the plate was lightly shaken using a Multidrop combi. The cells were incubated with serial extract dilutions for 68 h at 37 °C under a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. After incubation, 10 µL of 0.5 mM resazurin was added and incubated for 4 h. The fluorescence intensity was measured at ex 528 nm and em 590 nm using a SpectraMax Gemini XS microplate fluorescence scanner (Molecular Devices). While the IC50 value is calculated using the GraphPad Prism Version 8.3.1 (332) application.

Activity against Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense

T. b. rhodesiense strain IL-1501 [17] was cultured in HMI-9 supplemented with inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) media under a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Plant samples were tested using the in vitro assay method; extracts, fractions, and compounds were dissolved in DMSO and diluted in a culture medium. The final concentration of DMSO in this test is 1%. Serial concentrations were tested to determine 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) using the AlamarBlue [25] assay method. Serial concentrations of samples and pentamidine used as a positive control were prepared in 96 well microtiter plates containing the culture medium and then added with 2.0 × 104 cells/mL T. b. rhodesiense IL-1501 parasites. Next, it was incubated for 69 h at 37 ºC, 5% CO2 atmosphere. Following the incubation time, 10 µL of 0.5 mM resazurin (Sigma) dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline was added to each well, and the incubation was continued for 3 h. The test results were read using the SpectraMax Gemini XS microplate fluorescence scanner (Molecular Devices) using an excitation wavelength of 536 nm and an emission wavelength of 588 nm. Assays were carried out by repeating duplicates.

Activity against Trypanosoma Cruzi-Trypomastigote

The Tulahuen strain T. cruzi (TcLuc2) was cultured in DMEM without phenol red, and trypomastigote form was grown in monolayer 3T3 human cells [18] were cultured in DMEM with phenol red supplemented with inactivated FBS. Serial concentrations were tested using modification Luciferase Assay to determine the IC50 value [26]. First, the final concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL TcLuc2 was added to each well and incubated for 24 h. Then, the 2 × 105 cells/mL 3T3 were added to each well. The incubation for testing was four days after treatment with the compound. After incubation, 30 µL of mixed luciferase buffer contained final concentrations of 0.5 µM Tris HCl pH 7.8, 25 mM MgCl2, 1 mg/mL D-Luciferin, 125 µM ATP, 125 µM CoA, 1% (w/v) Triton X-100 and H2O was added to each well. Luminescent activity was measured at 560 nm.

Activity against Trypanosoma Cruzi-Epimastigote

T. cruzi epimastigote stage was cultured in an LIT medium supplemented with FBS [16]. The final concentration of cells was 5 × 103 cells/mL incubated with serial dilutions of the compound in a 96-well plate. The plate was then incubated in an anaerobic environment at 28 ℃ for four days. The luciferase buffer was added to each well, and the luminescent activity was measured at 560 nm. The IC50 value, indicative of the concentration required to inhibit parasite growth by 50%, was determined using the GraphPad Prism Version 8.3.1 (332) application. A < 10 µg/mL value suggests the extract’s potential to inhibit parasite growth effectively.

Cytotoxicity to human cells

The human hepatocyte-derived cellular carcinoma (Huh7), human liver cancer cell (HepG2), baby hamster kidney-21 (BHK-21), and African green monkey kidney (Vero) cell lines were maintained in DMEM media, and 3.7 g NaHCO3 in miliQ supplemented with 10% heat-activated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% of penicillin-streptomycin under 37 ºC humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. The Huh7, HepG2, BHK-21, and Vero cell lines were seeded at 3 × 104, 1 × 104, 5 × 103, and 1 × 104, respectively, in 96 well-plates (Corning) with serial concentrations of extracts, fractions, and compounds as previously explained by Coatti GC et al., [27] with several modifications. The plates were incubated for 44 h at 37 ºC under a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Following the incubation, 10µL of 0.5mM resazurin continued incubation for four h. The results were measured using the Nivo microplate reader (PerkinElmer) using an excitation wavelength of 530 nm and an emission wavelength of 595 nm.

The CC50 value, indicative of the concentration of substance which cytotoxic to 50% of a population of cells, was determined using the GraphPad Prism Version 8.3.1 (332) application. A > 20 µg/mL value suggests the substance was non toxic. Selectivity index (SI) is a ratio obtained by dividing the IC50 value into the CC50 value. The higher SI, the theoretically more effective and safe drugs.

Results

In vitro assessment was conducted to evaluate the antiprotozoal activity of various extracts

The dry powder from the plant part of the genus Cratoxylum was extracted using a stratified method starting from n-hexane, dichloromethane, and methanol. Six species of plants from the genus Cratoxylum, two from the genus Diospyros, and three from the genus Artocarpus were extracted, and 48 extracts were obtained. The extracts obtained are described in Table 1. Cratoxylum showed varies activity which several extracts showed IC50 values less than 10 µg/mL. Meanwhile, Diospyros and Artocarpus showed most extracts exhibited IC50 values more than 10 µg/mL which indicative less potent activity.

Among the tested extracts, two dichloromethane extracts derived from the Root of Cratoxylum arborescens (Ca.RD) and the Twig of Cratoxylum sumatranum (Cs.TD) exhibited the highest efficacy against all protozoa. Due to its superior activity compared to Cs.TD, the Ca.RD extract was chosen for further fractionation.

The separation and compound isolation from ca. RD

The isolation of compounds from 2.5 g of Ca.RD involved vacuum liquid chromatography (VLC), acquiring ten fractions (Ca.RD-D1 to D10). Antiprotozoal activity testing revealed that all fractions, except for D1, exhibited activity against all protozoa. In the assay against Plasmodium falciparum, fraction D6 displayed the highest inhibitory activity, with an IC50 value of 0.8 µg/mL. Conversely, in the assays against E. histolytica, L. donovani, and T. b. rhodesiense, fraction D7 demonstrated the highest resistance, with IC50 values of 1.6 µg/mL, 0.2 µg/mL, and 0.1 µg/mL, respectively. Crystallization of fraction D7 yielded yellow crystals, referred to as compound (1) (32.6 mg: 0.005%). Subsequent assays of compound (1) against P. falciparum, E. histolytica, L. donovani, and T. b. rhodesiense revealed IC50 values of 2.3 µg/mL, 0.3 µg/mL, 0.1 µg/mL, and 0.1 µg/mL, respectively (Table 2).

Structure identification of compound (1)

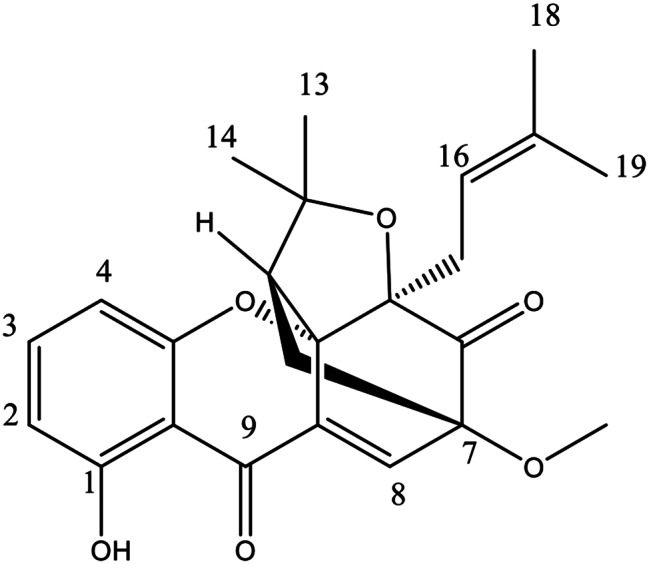

The structure of compound (1) was determined as Cochinchinone C (C24H26O6) based on NMR data (1H and 13C) compared to the reference. The 13C NMR data (Table 3) revealed the presence of 24 carbons and carbon resonances at δ180.80 (C-9) and δ201.28 (C-6), confirming the presence of conjugated- and unconjugated carbonyl groups. The 1H spectrum revealed resonances of a hydrogen-bonded hydroxy proton at δ12.00 (s, 1-OH) and three aromatic protons which coupled as an ABM system at δ6.54 (dd, J = 9 Hz, H-2), 7.40 (t, J = 8.3 Hz, H-3), and 6.50 (dd, J = 8.3 Hz, H-4). The spectrum displayed the presence of an olefinic proton (δ7.50, H-8), a methoxy group (δ3.63, s, 7-OCH3), a pair of non-equivalent methylene protons (δ1.57, dd, Hb-10 and 2.39, d, Ha-10), a methine proton (δ2.52, d, H-11) and a prenyl unit [δ4.38 (t, H-16), 2.63 (d, H-15), 1.35 (s, H-18) and 0.99 (s, H-19)] [28, 29]. The structure of cochinchinone C is shown in Fig. 1.

Table 3.

1H (400 MHz) and 13C (100 MHz) NMR data for compound (1) in CdCl3

| Position | Reference | Compound (1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| δH (J) | δC | δH (J) | δC | |

| 1-OH | 12.10 s | 162.9 C | 12.00 s, 1 H | 162.93 |

| 2 | 6.55 dd (8.4 Hz) | 109.5 CH | 6.54 dd, 1 H (9 Hz) | 109.63 |

| 3 | 7.41 t (8.4 Hz) | 138.9 CH | 7.40 t, 1 H (8.3 Hz) | 139.09 |

| 4 | 6.52 dd (8.4 Hz) | 107.4 CH | 6.50 dd, 1 H (8.3 Hz) | 107.52 |

| 4a | - | 159.4 C | - | 159.51 |

| 5a | - | 88.8 C | - | 88.79 |

| 5 | - | 84.1 C | - | 84.24 |

| 6 | - | 201.1 C | - | 201.28 |

| 7 | - | 84.8 C | - | 84.93 |

| 8 | 7.51 d (1.2 Hz) | 135.3 CH | 7.50 d, 1 H (1.4 Hz) | 135.29 |

| 9 | - | 180.7 C | - | 180.80 |

| 8a | - | 132.1 C | - | 132.20 |

| 9a | - | 106.1 C | - | 106.20 |

| 10a | 2.39 d (13.2 Hz) | 29.7 CH2 | 2.39 d, 1 H (12.8 Hz) | 29.78 |

| 10b | 1.58 dd (13.2 Hz) | - | 1.57 dd, 1 H (11.4 Hz) | - |

| 11 | 2.53 d (9.6 Hz) | 49.4 CH | 2.52 d, 1 H (9.8 Hz) | 49.47 |

| 12 | - | 83.9 C | - | 84.07 |

| 13 | 1.68 s | 30.4 CH3 | 1.67 s, 3 H | 30.45 |

| 14 | 1.32 s | 29.0 CH3 | 1.31 s, 3 H | 29.12 |

| 15 | 2.64 d (7.8 Hz) | 29.2 CH2 | 2.63 d, 2 H (8.3 Hz) | 29.28 |

| 16 | 4.41 t (7.8 Hz) | 118.4 CH | 4.38 t, 1 H (8.8 Hz) | 118.55 |

| 17 | - | 135.7 C | - | 135.84 |

| 18 | 1.37 s | 25.5 CH3 | 1.35 s, 3 H | 25.61 |

| 19 | 1.01 s | 16.7 CH3 | 0.99 s, 3 H | 16.76 |

| 7-OCH3 | 3.64 s | 54.1 CH3 | 3.63 s, 3 H | 54.18 |

Fig. 1.

Molecular structure of cochinchinone C

Antiprotozoal, cytotoxicity, and selectivity index of cochinchinone C

We conducted tests on the compound’s efficacy against T. cruzi to ascertain its potential for combating this disease. Our results indicate that cochinchinone C exhibits activity against T. cruzi in both amastigote and trypomastigote assays. Furthermore, the IC50 value suggests that the compound’s activity against T. cruzi surpasses that against other protozoa. The cytotoxicity of cochinchinone C was determined on several cell lines, and the selectivity index (SI) value was calculated (Table 4).

Table 4.

In vitro antiprotozoal, cytotoxicity and selectivity index of cochinchinone C

| Compound | Inhibition (IC50 µM) | Cytotoxicity (CC50 µM) | Selectivity Index (SI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pf | Eh | Ld | Tbr | Tc-t | Tc-e | HepG2 | Huh7 | BHK-21 | Vero | ||

| Cochinchinone C | 5.8 | 6.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.07 | 13.1 | 22.7 | 13.9 | 13.4 | 2.3–227 |

SI = CC50/IC50. Pf: P. falciparum, Eh: E. histolytica, Ld: L. donovani, Tbr: T. brucei rhodesiense, Tc-t: T. cruzi trypomastigote, Tc-e: T. cruzi epimastigote

The IC50 values of cochinchinone C against various protozoa ranged from 0.07 to 5.8 µM. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), these values fall within the high-activity category for inhibitory concentration, indicating a promising potential for antiparasitic drug discovery. Additionally, based on cytotoxicity assay results against Huh7, HepG2, BHK-21, and Vero cell lines, the selectivity index (SI) exceeds ten for E. histolytica, L. donovani, and T. b. rhodesiense, T. cruzi and surpasses two for P. falciparum. These findings suggest that cochinchinone C exhibits minimal toxicity toward carcinoma and normal cells [30].

Discussion

Drug development for neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) including E. histolytica, L. donovani, T. brucei rhodesiense, and T. cruzi presents a myriad of challenges alongside promising opportunities. These complexities inherent include funding constraints, regulatory hurdles, and limited market incentives as major barriers to drug development [31]. The lack of financial incentives for pharmaceutical companies to invest in NTD research often results in a neglect of diseases primarily affecting impoverished populations. Stringent regulatory requirements and limited resources hinder translating promising drug candidates from the laboratory to clinical practice. However, amidst these challenges lie significant opportunities for innovation and collaboration. The emergence of public-private partnerships and the advocacy efforts of global health organizations have catalyzed research efforts and facilitated access to funding for NTD drug development initiatives. Advances in technology, such as high-throughput screening assays and computational modeling, offer new avenues for identifying potential drug candidates and optimizing their efficacy. Collaborative approaches involving academia, industry, governments, and non-profit organizations promise to overcome the hurdles in NTD drug development and improve healthcare outcomes for vulnerable populations [32].

The research identifies Cratoxylum arborescens as a promising reservoir of antiprotozoal compounds, contributing to the expanding knowledge of the pharmacological importance of Indonesian plant extracts in addressing protozoal diseases. C. arborescens, a member of the Hypericaceae family prevalent in Southeastern Asia, including Indonesia and Thailand, has previously been documented to contain xanthone and anthraquinone compounds with a wide array of biological activities [33], such as anti-HIV [34], anti-tumor [35], and antibacterial properties [36].

The study focuses on the dichloromethane extract of C. arborescens root, revealing substantial activity against protozoa in vitro, which led to the isolation of cochinchinone C as a bioactive compound. This compound was known compound which previously isolated from the roots of C. cochinchinense and the roots of C. formosum spp. pruniflorum is reported to have low antioxidative properties and cytotoxicity activity against MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line with an IC50 value of 0,36 µg/mL, respectively [28, 29]. Further research reported that cochinchinone C from the roots of C. cochinchinense exhibited cytotoxicity activity against NCI-H187 human lung cancer cell line with IC50 value of 2.3 µg/mL and antimalarial activity against P. falciparum with IC50 value of 6.3 µM [37]. This study showed that cochinchinone C isolated from C. arborescens has similar anti-malarial activity with the IC50 value of 5.8 µM with cochinchinone C isolated from C. cochinchinense (IC50 value of 6.3 µM). The antimalarial activity data of cochinchinone C in this study is not the novel finding due to previously reported research.

However, antimalarial activity of cochinchinone C against P. falciparum which is not included as NTD was previously reported, but the other antiprotozoal activity as NTD against E. histolytica, L. donovani, T. brucei rhodesiense, and T. cruzi has yet to be found. This recent study isolated cochinchinone C from the roots of C. arborescens, and the compound was reported to exhibit antiprotozoal activity against those four protozoa, becoming the first reported data. Other cage-prenylated xanthones, namely conchinchinoxanthone and cochinchinone D, isolated from the stem bark of Cratoxylum sumatranum, were suggested as promising antiprotozoal against E. histolytica by inhibiting the NAD kinase pathway [19]. This study aligns with previous findings, highlighting the potential of cage-prenylated xanthone compounds like cochinchinone C as effective antiprotozoal agents. Xanthone compounds, characterized by a hydroxy group at the C1 of the A-ring of the xanthone scaffold, may enhance their activity through intramolecular hydrogen bonding, thus increasing the electrophilicity of the C8 enone [38]. The antiprotozoal activity of xanthone is likely attributed to their unique molecular structure.

Cochinchinone C demonstrates significant activity against L. donovani, T. b. rhodesiense, and Trypanosoma cruzi, indicating its potential as a lead compound for drug development. The compound’s structural features, including prenyl, hydroxy, and methoxy groups, contribute to its activity against protozoa, as evidenced by its low IC50 values with low cytotoxicity, positioning it as a safe and effective antiprotozoal agent.

Furthermore, identifying cochinchinone C as a potent antiprotozoal compound from Cratoxylum arborescens highlights the potential of natural products as a source of novel drug candidates. Natural products’ structural diversity and complex chemical profiles offer a vast reservoir of bioactive molecules with diverse pharmacological activities. Therefore, continued exploration of Indonesian plants and other biodiversity-rich regions holds promise for discovering new therapeutics to combat protozoal diseases and other global health challenges. Natural products often exhibit unique mechanisms of action and target specificity, offering advantages over synthetic drugs, including reduced toxicity and lower risk of resistance development. Leveraging the power of natural products in drug discovery requires interdisciplinary collaboration between chemists, pharmacologists, biologists, and clinicians to fully explore their therapeutic potential and translate promising compounds into clinically effective treatments [39].

Conclusion

The findings of this study demonstrate the potential of Cratoxylum arborescens as a valuable source of antiprotozoal compounds, with cochinchinone C emerging as a promising lead for further drug development. The potency of cochinchinone C might be further studied for its mechanism of action as antiprotozoal or exploring its synergistic effects with other drugs. The study also highlights the importance of biodiversity-rich regions like Indonesia in providing novel therapeutic agents derived from natural products. Moreover, the successful isolation and characterization of cochinchinone C underscore the significance of interdisciplinary research approaches, combining traditional medicinal knowledge with modern scientific methods. Moving forward, continued exploration of natural product diversity and collaboration with indigenous communities hold immense promise for addressing global health challenges. By harnessing the power of nature and honoring traditional healing practices, we can pave the way for developing safe, effective, and culturally sensitive treatments for protozoal diseases and beyond.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Prof. Mulyadi Tanjung and the team from the Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science and Technology, Universitas Airlangga, for providing plant samples.

Abbreviations

- NTDs

Neglected tropical diseases

- VLC

Vacuum liquid chromatography

- TLC

Thin layer chromatography

- NMR

Nuclear magnetic resonance

- DMSO

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- APAD

3-acetyl pyridine NAD

- NBT

Nitroblue tetrazolium

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium

- MgCl

Magnesium chloride

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- CoA

Co-enzyme A

Author contributions

DKS: Performed part of experiments; Data analysis; Writing-original draft. GJ: Performed part of experiments; Data analysis; Manuscript revision. HI: Performed part of experiments; Data analysis. LT: Performed part of experiments; Data analysis; Manuscript revision. RW: Manuscript revision. AW: Conceptualization; Data analysis; Writing-reviewing. TN: Conceptualization; Data analysis; Writing-reviewing. AFH: Conceptualization; Data analysis; Writing-reviewing. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by a grant from Universitas Airlangga through Riset Kolaborasi Internasional Top #100, contract no. 251/UN3.15/PT/2022.

Data availability

The manuscript comprehensively presents all the data underpinning this study’s findings. No additional data are available beyond what is included in the published article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Engels D, Zhou XN. Neglected tropical diseases: an effective global response to local poverty-related disease priorities. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Ending the neglect to attain the Sustainable Development Goals: a road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021–2030. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. License: C BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferreira LLG, de Moraes J, Andricopulo AD. Approaches to advance drug discovery for neglected tropical diseases. Drug Discov Today. 2022;27(8):2278–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varikuti S, Jha BK, Volpedo G, Ryan NM, Halsey G, Hamza OM, McGwire BS, Satoskar AR. Host-Directed Drug Therapies for Neglected Tropical diseases caused by Protozoan parasites. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2655. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02655. PMID: 30555425; PMCID: PMC6284052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Theel ES, Pritt BS, Parasites. Microbiol Spectr. 2016;4(4). 10.1128/microbiolspec.DMIH2-0013-2015. PMID: 27726821. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Varo R, Chaccour C, Bassat Q. Update on malaria. Med Clin (Barc). 2020;155(9):395–402. English, Spanish. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vincent IM, Barrett MP. Metabolomic-based strategies for anti-parasite drug discovery. J Biomol Screen. 2015;20(1):44–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tse EG, Korsik M, Todd MH. The past, present and future of anti-malarial medicines. Malar J. 2019;18:93. 10.1186/s12936-019-2724-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nash H. Mattew. The 201 Most (& Least) Biodiverse Countries in 2022. https://theswiftest.com/biodiversity-index/. Accessed 09 December 2022.

- 10.Rodanant P, Boonnak N, Surarit R, Kuvatanasuchati J, Lertsooksawat W. Antibacterial, anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant activities of various isolated compounds from Cratoxylum species. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2017;30(3):667–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laphookhieo S, Maneerat W, Koysomboon S. Antimalarial and cytotoxic phenolic compounds from Cratoxylum maingayi and cratoxylum cochinchinense. Molecules. 2009;14(4):1389–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phuwapraisirisan P, Udomchotphruet S, Surapinit S, Tip-Pyang S. Antioxidant xanthones from Cratoxylum cochinchinense. Nat Prod Res. 2006;20(14):1332–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fareed N, El-Kersh DM, Youssef FS, Labib RM. Unveiling major ethnopharmacological aspects of genus Diospyros in context to its chemical diversity: a comprehensive overview. J Food Biochem. 2022;46(12):e14413. 10.1111/jfbc.14413. Epub 2022 Sep 22. PMID: 36136087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jagtap UB, Bapat VA. Artocarpus: a review of its traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;129(2):142–66. 10.1016/j.jep.2010.03.031. Epub 2010 Apr 7. PMID: 20380874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diamond LS, Harlow DR, Cunnick CC. A new medium for the axenic cultivation of Entamoeba histolytica and other Entamoeba. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1978;72(4):431–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joshi M, Dwyer DM, Nakhasi HL. Cloning and characterization of differentially expressed genes from in vitro-grown ‘amastigotes’ of Leishmania donovani. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;58(2):345–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuboki N, Inoue N, Sakurai T, Di Cello F, Grab DJ, Suzuki H, Sugimoto C, Igarashi I. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification for detection of African trypanosomes. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(12):5517–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Voorhis WC, Eisen H. Fl-160. A surface antigen of Trypanosoma Cruzi that mimics mammalian nervous tissue. J Exp Med. 1989;169(3):641–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wardana FY, Sari DK, Adianti M, Permanasari AA, Tumewu L, Nozaki T, et al. vitro Anti-Amebic Activity of Cage Xanthones from Cratoxylum sumatranum Stem Bark Against Entamoeba histolytica. Pharmacogn J. 2020;12(3):452–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmed DE, Rashidi FB, Abdelhakim HK, Mohamed AS, Arafa HMM. An in vitro cytotoxicity of glufosfamide in HepG2 cells relative to its nonconjugated counterpart. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2021;33(1):22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pilarek M, Grabowska I, Ciemerych MA, Dąbkowska K, Szewczyk KW. Morphology and growth of mammalian cells in a liquid/liquid culture system supported with oxygenated perfluorodecalin. Biotechnol Lett. 2013;35(9):1387–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cahyono AW, Fitri LE, Winarsih S, Prabandari EE, Waluyo D, Pramisandi A, Chrisnayanti E, Dewi D, Siska E, Nurlaila N, Nugroho NB, Nozaki T, Suciati S, Nornidulin. A New Inhibitor of Plasmodium falciparum Malate: Quinone Oxidoreductase (PfMQO) from Indonesian Aspergillus sp. BioMCC f.T.8501. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023;16(2):268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Makler MT, Piper RC, Milhous WK. Lactate dehydrogenase and the diagnosis of malaria. Parasitol Today. 1998;14(9):376–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mori M, Tsuge S, Fukasawa W, Jeelani G, Nakada-Tsukui K, Nonaka K, Matsumoto A, Ōmura S, Nozaki T, Shiomi K. Discovery of Antiamebic Compounds That Inhibit Cysteine Synthase From the Enteric Parasitic Protist Entamoeba histolytica by Screening of Microbial Secondary Metabolites. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Räz B, Iten M, Grether-Bühler Y, Kaminsky R, Brun R. The Alamar Blue assay to determine drug sensitivity of African trypanosomes (T.b. et al.) in vitro. Acta Trop. 1997;68(2):139–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niikura M, Komatsuya K, Inoue SI, Matsuda R, Asahi H, Inaoka DK, Kita K, Kobayashi F. Suppression of experimental cerebral malaria by disruption of malate:quinone oxidoreductase. Malar J. 2017;16(1):247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coatti GC, Marcarini JC, Sartori D, Fidelis QC, Ferreira DT, Mantovani MS. Cytotoxicity, genotoxicity and mechanism of action (via gene expression analysis) of the indole alkaloid aspidospermine (antiparasitic) extracted from Aspidosperma polyneuron in HepG2 cells. Cytotechnology. 2016;68(4):1161–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nawong Boonnak S, Chantrapromma H-K, Fun S, Yuenyongsawad, Brian O, Patrick W, Maneerat DE, Williams, Andersen RJ. Three Types of Cytotoxic Natural Caged-Scaffolds: Pure Enantiomers or Partial Racemates. J Nat Prod. 2014;77:1562–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahabusarakam W, Nuangnaowarat W, Taylor WC. Xanthone derivatives from Cratoxylum cochinchinense roots. Phytochemistry. 2006;67(5):470–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Indrayanto G, Putra GS, Suhud F. Validation of in-vitro bioassay methods: Application in herbal drug research. Profiles Drug Subst Excip Relat Methodol. 2021;46:273–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trouiller P, Olliaro P, Torreele E, Orbinski J, Laing R, Ford N. Drug development for neglected diseases: a deficient market and a public-health policy failure. Lancet. 2002;359(9324):2188–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weng HB, Chen HX, Wang MW. Innovation in neglected tropical disease drug discovery and development. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018;7(1):67. 10.1186/s40249-018-0444-1. PMID: 29950174; PMCID: PMC6022351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pattanaprateeb P, Ruangrungsi N, Cordell GA. Cytotoxic constituents from Cratoxylum arborescens. Planta Med. 2005;71(2):181–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reutrakul V, Chanakul W, Pohmakotr M, Jaipetch T, Yoosook C, Kasisit J, Napaswat C, Santisuk T, Prabpai S, Kongsaeree P, Tuchinda P. Anti-HIV-1 constituents from leaves and twigs of Cratoxylum arborescens. Planta Med. 2006;72(15):1433–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El Habbash AI, Mohd Hashim N, Ibrahim MY, Yahayu M, Omer FAE, Abd Rahman M, Nordin N, Lian GEC. In vitro assessment of anti-proliferative effect induced by α-mangostin from Cratoxylum arborescens on HeLa cells. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Sidahmed HM, Hashim NM, Mohan S, Abdelwahab SI, Taha MM, Dehghan F, Yahayu M, Ee GC, Loke MF, Vadivelu J. Evidence of the gastroprotective and anti-Helicobacter pylori activities of β-mangostin isolated from Cratoxylum arborescens (vahl) Blume. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016;10:297–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laphookhieo S, Syers JK, Kiattansakul R, Chantrapromma K. Cytotoxic and antimalarial prenylated xanthones from Cratoxylum cochinchinense. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 2006;54(5):745–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chantarasriwong O, Milcarek AT, Morales TH, Settle AL, Rezende CO Jr, Althufairi BD, Theodoraki MA, Alpaugh ML, Theodorakis EA. Synthesis, structure-activity relationship and in vitro pharmacodynamics of A-ring modified caged xanthones in a preclinical model of inflammatory breast cancer. Europen J Med Chem. 2019;168:405–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs from 1981 to 2014. J Nat Prod. 2016;79(3):629–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The manuscript comprehensively presents all the data underpinning this study’s findings. No additional data are available beyond what is included in the published article.