Abstract

Purpose:

The aim of this paper was to compare three conventional hand mixing glass-ionomer cements (GICs) and a new mechanical mixing glass-ionomer cement.

Materials and Methods:

Samples were measured on days 1, 2, 6, 10, 31, 90 and 180. After 32 and 181 days of monitoring, the samples were recharged by using 1 ml of 2% sodium fluoride gel.

Results:

The fluoride release started in high concentration during the first day for all GICs, with a value for GIII of 32.6 ppm. From the 2nd day, a slow, steady decline, with the exception of GII, which showed a marked decline to a value of 3.2 ppm. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) test showed statistically significant differences between the amounts of fluoride of the four materials in the first 24 h. Student t test was used to compare the fluoride release between the first and second recharge in each one of the study groups. Statistically significant differences were found when we compared the fluoride release in groups I (t = –16.95, p = 0.000) and IV (t = –2.644, p = 0.26).

Conclusions:

A mechanical mixing was the material with the more constant fluoride release and after recharge showed the highest fluoride release which make it an important benefit for clinicians.

Keywords: anticariogenic agents, fluoride, glass-ionomer cement

The mechanism of glass-ionomer cements (GICs) is an acid-base reaction between ion-leachable fluoroaluminosilicate glasses and polyalkenoic acids.11,18,23,25

One mechanism is a short-term reaction, which involves rapid dissolution from outer surface into solution, whereas the second is more gradual and results in sustained diffusion of ions through the bulk cement.19,26

The fluoride is well documented as an anticariogenic agent.1,15,26 The anticariogenic effect of fluoride-releasing materials depends on the amount and sustainability of fluoride release. The fluoride release from a restorative material is determined by the matrix of the restorative material, the mechanism by which it sets, and the amount of fluoride-containing fillers.16,17 A variety of mechanisms is involved in the anticariogenic effects of fluoride, including the reduction of demineralisation, the enhancement of remineralisation, the interface of pellicle and plaque formation, and the inhibition of microbial growth and metabolism. Fluoride released from dental restorative materials is assumed to affect caries formation through all these mechanisms and may therefore reduce or prevent demineralisation and promote remineralisation of dental hard tissues.9,10,26 Previous studies have demonstrated that variables intrinsically related to the chemical formulation, as well as to the physical presentation of the GICs, affect the fluoride release qualitatively and quantitatively. These variables, such as the composition of the aluminosilicate glass and the polyalkenoic acid, the particle size of the glass powder, the relative proportion of the constituents (glass/polyacid/tartaric acid/water) in the cement mix and the type of mixing, are mainly determined by the manufacturer.6,7

Some studies indicate that hand mixing and mechanical mixing in capsules can result in a different fluoride release profile, suggesting that the mixing process could play an important role.7 Recently, it has been reported that fluoride-releasing materials can take up fluoride ions from the oral environment as a means of replacing fluoride which has been lost. The recharge of fluoride may contribute to the ability of these materials to provide a long-term inhibitory effect on enamel demineralisation, because the recharged fluoride is released again and presumably contributes to continuous prevention of enamel demineralisation.2,13,21,22 Therefore, the objective of this study was to compare three conventional hand mixing GICs with a new mechanical mixing glass-ionomer cement.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimen Preparation

For conventional hand mixing, GICs were used in this study: a GII-Fuji IX (GC, Kyoto, Japan); GIII-Ionofil Molar (Vocco, Cuxhaven, Germany); GIV-Ketac Molar (3M Oral Care, St Paul, MN, USA). For the mechanical mixing group, the glass-ionomer cement was GI-Fuji IX GP EXTRA (GC).

The materials were handled according to the manufacturers’ instructions, and 40 samples were prepared. The samples consisted of 10 blocks of each GICs with 5 mm width and 1 mm thickness; the samples were placed in cavities with similar measures in a Teflon matrix.8,12

The polymerised samples were removed from the matrix and later stored in plastic bottles with 5 ml of deionised water. The samples were conserved at 37°C for 60 days and measured on days 1, 2, 6, 10, 31, 90 and 180, which is similar to the time intervals used in previous studies.8,12

Instrumentation and Reagent Solutions

To determine the amount of fluoride in GICs, it was necessary to use an ion-selective electrode for sodium fluoride (model 1011; Hanna Instruments, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and a potentiometer (model 3222; Hanna Instruments). The total ionic strength adjustment buffer (TISAB) solution was used to keep the pH stable and to prevent the fluoride ion from producing complexes with different cations.21

Potentiometer Calibration

The fluoride solutions used in this study were prepared in concentrations of 1, 2, 10, 100, and 1000 ppm. TISAB was used to obtain a calibration slope with fluoride solutions; equal volumes of fluoride solution and TISAB (25 ml of each) were placed and mixed in a 100-ml plastic glass; the device was calibrated until the readings were reached.21

Fluoride Determination

At the end of each period, the blocks were removed from their respective recipients, and each sample was washed with 1 ml of deionised water in the bottle which was the original container. Five millilitres (5 ml) of solution was used to store the sample, and 1 ml was used to wash the sample, giving a total of 6 ml that was mixed with 6 ml of TISAB, because this solution works in a proportion of 1:1.

The sample was placed in a new 5 ml plastic bottle with deionised water.

The readings were performed under magnetic stirring for 3 min with the electrode immersed in the solution where the sample had been previously. The values of the readings were expressed in parts per million.2,21

After 32 and 181 days of monitoring, the samples were recharged using 1 ml of 2% sodium fluoride gel (Ionite Borgatta, Mexico). The samples were immersed in this gel for 4 min and subsequently cleaned with a sterile gauze. The fluoride released in the samples after recharge was determined daily for 5 days.12,21

The data were analysed with analysis of variance (ANOVA), and Student’s t test was used for related samples using the 21st version of the statistical program SPSS Statistics (IBM, Nashville, Tennessee).

The aim of this paper was to compare three conventional hand mixing GICs and a new mechanical mixing glass-ionomer cement. And the work hypothesis is ‘The fluoride release of the glass-ionomer cement reinforced with NPs of TiO2 is greater than that released by the conventional glass-ionomer cement’.

RESULTS

The pattern of fluoride released according to the time intervals is represented in Table 1 and started with high concentration for the first day for all GICs, with a value for GIII of 32.6 ppm, which makes this material the one with the highest fluoride concentration, and for GIV, it presented fluoride releases of 17.4 ppm, which makes it the GIC with the lowest fluoride concentration. The groups GI and GII presented fluoride releases of 17.8 ppm and 30.0 ppm, respectively.

Table 1.

Fluoride released in glass-ionomer cements

|

Periods days |

Fluoride released |

Recharged |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

GI mean (SD) ppm |

GII mean (SD) ppm |

GIII mean (SD) ppm |

GIV mean (SD) ppm |

GI mean (SD) ppm |

GII mean (SD) ppm |

GIII mean (SD) ppm |

GIV mean (SD) ppm |

|

| > 1 |

17.8 (0.03) |

30.0 (0.02) |

32.6 (0.07) |

17.4 (0.05) |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| > 2 |

10.0 (1.1) |

3.2 (1.2) |

22.0 (0.03) |

5.9 (0.23) |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| > 6 |

7.7 (0.02) |

2.5 (1.04) |

3.7 (0.78) |

2.3 (0.09) |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

10 |

5.6 (0.5) |

2.2 (0.08) |

3.2 (1.20) |

1.5 (1.23) |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

31 |

2.4 (0.21) |

1.9 (0.73) |

2.2 (1.52) |

1.2 (0.30) |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

32 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

77 (0.45) |

28 (0.78) |

41 (1.20) |

33 (0.02) |

|

90 |

23.3 (0.07) |

11.9 (1.50) |

15.0 (0.23) |

10.2 (0.60) |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

180 |

30.9 (0.08) |

18.8 (0.02) |

24.4 (1.50) |

21.5 (0.09) |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

181 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

81 (0.05) |

51 (0.03) |

41 (1.81) |

36 (0.02) |

SD, standard deviation; GI (Fuji IX extra); GII (Fuji IX); GIII (Ionofil Molar); GIV(Ketac Molar).

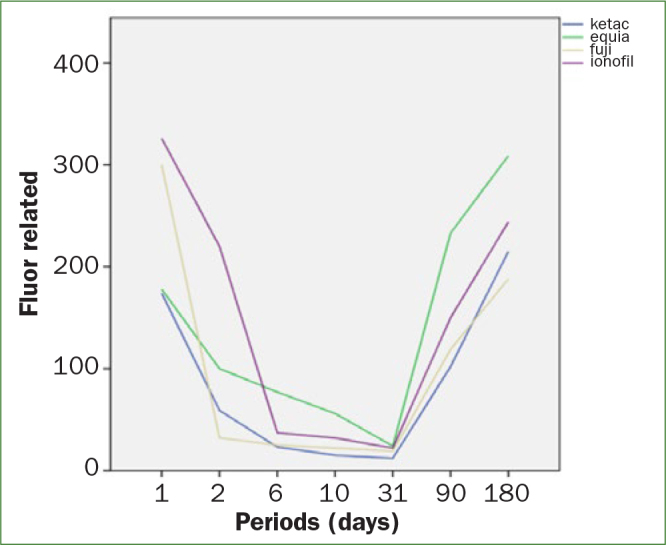

From the 2nd day, a slow, steady decline in fluoride release began and continued, with the exception of GII, which showed a marked decline to a value of 3.2 ppm. In Figure 1, the amount of fluoride released for each GICs evaluated versus time is clearly shown.

Fig 1.

Fluoride released for each GICs evaluated versus time.

However, GI showed a lower but more constant release pattern, starting with 17.8 ppm and reaching up to 2.4 ppm until day 31. ANOVA test showed statistically significant differences between the amounts of fluoride of the four materials in the first 24 h (Table 2). However, the interaction between time and material shows that the fluoride release is not constant with time for all materials under study.

Table 2.

Analysis of variance of fluoride released in the study groups

|

Source |

Sum of squares |

df |

Mean-square |

F |

P |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

GI |

Intergroup |

599,333 |

7 |

85,619 |

256,857 |

0.004 |

|

(Fuji IX Extra) |

Intragroup |

0.667 |

2 |

0.333 |

||

|

Total |

600,000 |

9 |

||||

|

GIII |

Intergroup |

3,805,833 |

7 |

543,690 |

12,264 |

0.077 |

|

(Ionofil Molar) |

Intragroup |

88,667 |

2 |

44,333 |

||

|

Total |

3,894,500 |

9 |

||||

|

GIV |

Intergroup |

290,600 |

7 |

415,271 |

8475 |

0.110 |

|

(Ketac Molar) |

Intragroup |

98,000 |

2 |

49,000 |

||

|

Total |

3,004,900 |

9 |

ANOVA, analysis of variance.

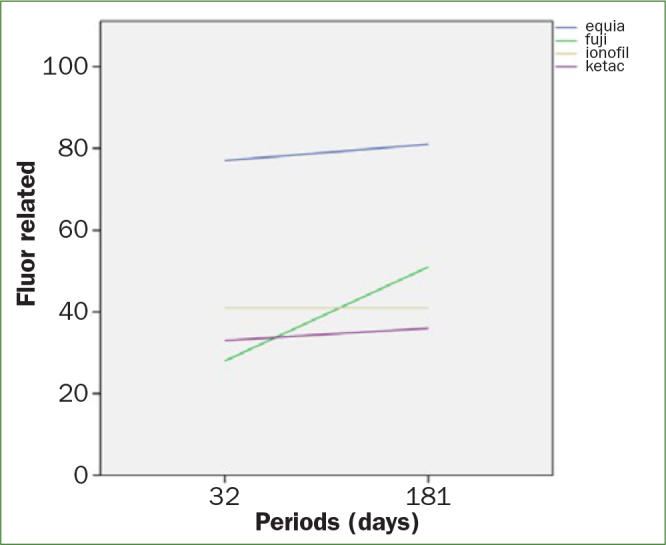

On day 32, when recharges began with a fluorinated gel for 4 min, it can be seen that the recharge induced an increase in all GICs. In the same way, GI showed the highest fluoride release in day 32 when recharge started with a value of 77 ppm after the recharge. On day 90, GI has released again the highest amount of fluoride with a value of 23.3 ppm. In day 180, a second recharge was made, and the value for GI was 81 ppm. Figure 2 illustrates the fluoride release of each sample after being recharged. Therefore, GI presented an improved and sustained fluoride release during the study (Table 1).

Fig 2.

Fluoride release of each sample after being recharged.

Student t test was used to compare the fluoride release between the first and second recharge in each one of the study groups. Statistically significant differences were found when we compare the fluoride release in groups I (t = –16.95, p = 0.000) and IV (t = –2.644, p = 0.26) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Student t test of fluoride released in the study groups

|

Mean-square |

Standard deviation |

Confidence interval |

t |

gl |

P |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lower |

Higer |

||||||

|

GI (Fuji IX Extra) |

–23.000 |

4.295 |

–26.072 |

–19.928 |

–16.935 |

9 |

0.000 |

|

GII (Fuji IX) |

–4.300 |

6.816 |

–9.176 |

0.576 |

–1.995 |

9 |

0.077 |

|

GIII (Ionofil Molar) |

–4.300 |

6.816 |

–9.176 |

0.576 |

–1.995 |

9 |

0.077 |

|

GIV (Ketac Molar) |

–3.300 |

3.917 |

–6.102 |

–498 |

–2.664 |

9 |

0.026 |

DISCUSSION

According to some authors, the amount of fluoride release to prevent demineralisation and caries is not well documented.21 The values reported by different authors are between 0.02 and 0.2 ppm.

Based on our results, the GICs with conventional mixing were released between 32.6 and 17.4 ppm during the first 24 h, whereas the mechanical mixing GIC showed an average of 17.8 ppm in the same period. The higher fluoride release was observed in the first 24 h, these results match with those reported by Prabhakar et al20 where they found that in this period, the greatest fluoride release occurred. In this study, Fuji IX was evaluated and they reported values between 5.42 and 10.96 ppm, unlike in our results, where the value for the GII in conventional mixing was 30.0 ppm, and for mechanical mixing, it was 17.8 ppm.

Several authors mentioned that fluoride release commenced with an initial burst followed by a statistically significant decrease.4,5,26 Tiwari and Nandlal24 reported a marked decrease in conventional GICs in the mean fluoride released from day 1 to day 21.

However, Krämer et al14 report that after 14 days the GIC Ketac Molar showed a fluoride release with an average of 12 ± 8 ppm, contrary to what we found that Ketac Molar released just 1.5 ppm after 10 days of monitoring.

It can be observed that GIII with conventional mixing was the material that released the highest fluoride for the first 24 h, whereas GI with mechanical mixing was the material that presented a more constant fluoride release during the study.

CONCLUSION

Some authors mention that the exposure to fluoride solutions cannot restore the initial fluoride release, and it is thought that the cause is the short time of recharge because the fluoride solution is in contact just with the superficial part of the sample. Ahn et al2 and Arbabzadeh et al3 carried out studies recharging with mouthwash for 20 min, but this method is clinically impractical because a patient cannot keep this topical fluoride agent during this time. In our study, all materials were recharged with sodium fluoride gel for 4 min, this period is established for this topical fluoride agent and is bearable for the patient, besides, we obtained positive results after recharging mainly in GI (mechanical mixing), where on day 32 a fluoride release of 77 ppm was shown and for the second recharge in day 181 (after 6 months), values of 81 ppm were shown. These results suggest that topical fluoride gel is a very important alternative for recharged fluoride-releasing materials, and the material of GI is an excellent option of treatment in patients that are at high risk in developing caries.

REFERENCES

- Almuhaiza M. Glass-ionomer cements in restorative dentistry: a critical appraisal. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2016;17:331–336. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn SJ, Lee SJ, Lee DY, Lim BS. Effects of different fluoride recharging protocols on fluoride ion release from various orthodontic adhesives. J Dent. 2011;39:196–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbabzadeh-Zavareh F, Gibbs T, Meyers IA, Bouzari M, Mortazavi S, Walsh LJ. Recharge pattern of contemporary glass ionomer restoratives. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2012;9:139–145. doi: 10.4103/1735-3327.95226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahadure RN, Pandey RK, Kumar R, Gopal K, Singh RK. An estimation of fluoride release from various dental restorative materials at different pH: in vitro study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2012;30:122–126. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.99983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byeon SM, Lee MH, Bae TS. The effect of different fluoride application methods on the remineralization of initial carious lesions. Restor Dent Endod. 2016;41:121–129. doi: 10.5395/rde.2016.41.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Mestres G, Lan W, Xia W, Enggvist H. Cytotoxicity of modified glass ionomer cement on odontoblast cells. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2016;27:116. doi: 10.1007/s10856-016-5729-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Moor RJ, Verbeeck RM. Effect of encapsulation on the fluoride release from conventional glass ionomers. Dent Mater. 2002;18:370–375. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(01)00052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggert F, Neubert R. In vitro investigation of the liberation of fluoride ions from toothpaste compounds in a permeation model. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 1999;47:169–173. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(98)00060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Contreras R, Scougall-Vilchis RJ, Contreras-Bulnes R, Sakagami H, Morales-Luckie RA, Nakajima H. Mechanical, antibacterial and bond strength properties of nano titanium-enriched glass ionomer cement. J Appl Oral Sci. 2015;23:321–328. doi: 10.1590/1678-775720140496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjorgievska E, Tendeloo G, Nicholson JN, Coleman NJ, Slipper IJ, Booth S. The incorporation of nanoparticles into conventional glass-ionomer dental restorative cements. Microsc Microanal. 2015;21:392–406. doi: 10.1017/S1431927615000057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemura K, Tay F, Kouro Y, Endo T, Yoshiyama M, Miyai K, Pashley DH. Optimizing filler content in an adhesive system containing pre-reacted glass-ionomer fillers. Dent Mater. 2003;19:137–146. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(02)00022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishore G, Sai-Sankar AJ, Pratap-Gowd M, Sridhar M, Pranitha K, Sai-Krishna VS. Comparative evaluation of fluoride releasing ability of various restorative materials after the application of surface coating agents – an in-vitro study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:38–41. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/21980.9047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinke T, Daboul A, Turek A, Frankenberger R, Hickel R, Biffar R. Clinical performance during 48 months of two current glass ionomer restorative systems with coatings: a randomized clinical trial in the field. Trials. 2016;17:239–353. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1339-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krämer N, Schmidt M, Lücker S, Domann E, Frankenberger R. Glass ionomer cement inhibits secondary caries in an in vitro biofilm model. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22:1019–1031. doi: 10.1007/s00784-017-2184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamia E, Daifalla LE, Enas H, Mobarak EH. Effect of ultrasound application during setting on the mechanical properties of high viscous glass-ionomers used for ART restorations. J Adv Res. 2015;6:805–810. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickenautsch S. High-viscosity glass-ionomer cements for direct posterior tooth restorations in permanent teeth: the evidence in brief. J Dent. 2016;55:121–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau JL, Xu HH. Fluoride releasing restorative materials: effects of pH on mechanical properties and ion release. Dent Mater. 2010;26:227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer G, Jones F, Billington RW, Pearson GJ. Chlorhexidine release from an experimental glass ionomer cement. Biomaterials. 2003;19:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panahandeh N, Torabzadeh H, Aghaee M, Hasani E, Safa S. Effect of incorporation of zinc oxide nanoparticles on mechanical properties of conventional glass ionomer cements. J Conserv Dent. 2018;21:130–135. doi: 10.4103/JCD.JCD_170_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar AR, Balehosur DV, Basappa N. Comparative evaluation of shear bond strength and fluoride release of conventional glass ionomer with 1% ethanolic extract of propolis incorporated glass ionomer cement – in vitro study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:88–91. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/17056.7818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmerón-Valdés EN, Scougall-Vilchis RJ, Alanis-Tavira J, Morales-Luckie RA. Comparative study of fluoride released and recharged from conventional pit and fissure sealants versus surface prereacted glass ionomer technology. J Conserv Dent. 2016;19:41–45. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.173197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw A, Carrick T, McCabe J. Fluoride release from glass-ionomer and compomer restorative materials: 6-month data. J Dent. 1998;26:355–359. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(97)00016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shidu SK, Nicholson JW. A review of glass-ionomer cements for clinical dentistry. J Funct Biomater. 2016;7:2–15. doi: 10.3390/jfb7030016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari S, Nandlal B. Comparative evaluation of fluoride release from hydroxyapatite incorporated and conventional glass ionomer cement: an in vitro study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2012;30:284–287. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.108921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson TF, Atmeh AR, Sajini S, Cook RJ, Festy F. Present and future of glass-ionomers and calcium-silicate cements as bioactive materials in dentistry: biophotonics-based interfacial analyses in health and disease. Dent Mater. 2014;30:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2013.08.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand A, Buchalla W, Attin T. Review on fluoride-releasing restorative materials fluoride release and up take characteristics, antibacterial activity and influence on caries formation. Dent Mater. 2007;23:343–362. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]