Abstract

Evolution occurs when selective pressures from the environment shape inherited variation over time. Within the laboratory, evolution is commonly used to engineer proteins and RNA, but experimental constraints have limited the ability to reproducibly and reliably explore factors such as population diversity, the timing of environmental changes and chance on outcomes. We developed a robotic system termed phage- and robotics-assisted near-continuous evolution (PRANCE) to comprehensively explore biomolecular evolution by performing phage-assisted continuous evolution in high-throughput. PRANCE implements an automated feedback control system that adjusts the stringency of selection in response to real-time measurements of each molecular activity. In evolving three distinct types of biomolecule, we find that evolution is reproducibly altered by both random chance and the historical pattern of environmental changes. This work improves the reliability of protein engineering and enables the systematic analysis of the historical, environmental and random factors governing biomolecular evolution.

Biologists have long sought to understand the effects of history and the environment on evolutionary outcomes. The long-term evolution experiment set the gold standard for characterizing genomic evolution at scale: tracking 12 separate Escherichia coli populations over 65,000 generations1,2. However, it has proven difficult to gather datasets of similar scope for the evolution of individual biomolecules. Laboratory protein evolution traditionally uses discrete rounds of targeted in vitro mutagenesis and selection3, sacrificing throughput, replicates and trajectory length in favor of restricting mutations to a single gene or pathway within an otherwise fixed environment. High-throughput molecular evolution methods are needed to quantify the effects of history and environmental selection pressures on single-gene evolution4 and enable more robust biomolecular engineering.

Continuous directed evolution methods accelerate the process of diversification and selection by coupling gene function to the fitness of a rapidly replicating organism, such as a bacteriophage5, mammalian virus6,7 or a yeast plasmid8,9. The power of these techniques comes from the ability to rapidly cycle through dozens of generations, and they have been used to quantify mutation rate10, track evolution pathways9,11 and rapidly engineer diverse proteins including highly specific nanobodies7 and improved CRISPR effectors12. While valuable additions to the biomolecule evolution toolkit13-15, these experiments are laborious, limited by low throughput and difficult to execute with precise environmental control. Extracting fundamental insights about biomolecular evolution and systematically producing evolved biomolecules with desired activities requires comprehensively sampling the parameters known to influence the results of evolution—including the initial genotype16-18 and the evolution environment19—in high replicate20.

We present a new approach that combines the speed of continuous evolution, precise control of the environment and the throughput required to evolve many independent populations in parallel. Whereas classic evolution ‘replay’ experiments21 and existing continuous evolution methods5 evolve a single population contained within a continuous-flow bioreactor (Fig. 1a), we developed a high-throughput plate-based method and applied it to a widely used evolution technique, phage-assisted continuous evolution (PACE)5. In our method, evolving bacteriophage populations are housed within 96-well plates on a high-throughput liquid-handling system, which is controlled using Python22 to achieve the same host bacteria flow-through rates as continuous-flow bioreactors. This system enables continuous evolution in 96-plex using commonly available robotic equipment and open-source software22. It offers several distinct advantages over existing methods13-15 including scalability to hundreds of parallel populations, historical sampling in 96-well plate format, real-time monitoring of any molecular fitness output rather than just growth effects15,23 and precise temporal and chemical control of the environment. We use this platform to identify improbable mutations in a single molecular evolution by performing the experiment in 96-plex, and next demonstrate that the inclusion of controls, replicates and many diverse initial genotypes increases the likelihood of successful evolution and improves interpretation of results. Further, miniaturization enables us to precisely fine-tune the chemical environment of each experiment using reagent-limiting compounds23. Using real-time activity monitoring, we implement a feedback control system in which the stringency of the bacterial host strain is autonomously adjusted in response to measurements of biomolecule activity, robustly producing evolved variants by eliminating failures associated with improper selection strength. When combined with high-throughput sequencing, we are also able to distinguish both contingent and deterministic evolution outcomes. Finally, we present an optimized method using limited consumables, capable of week-long multi-path experiments with only once-per-day researcher intervention. Thus, the high-throughput continuous evolution platform we describe enables systematic exploration of the factors responsible for evolutionary outcomes.

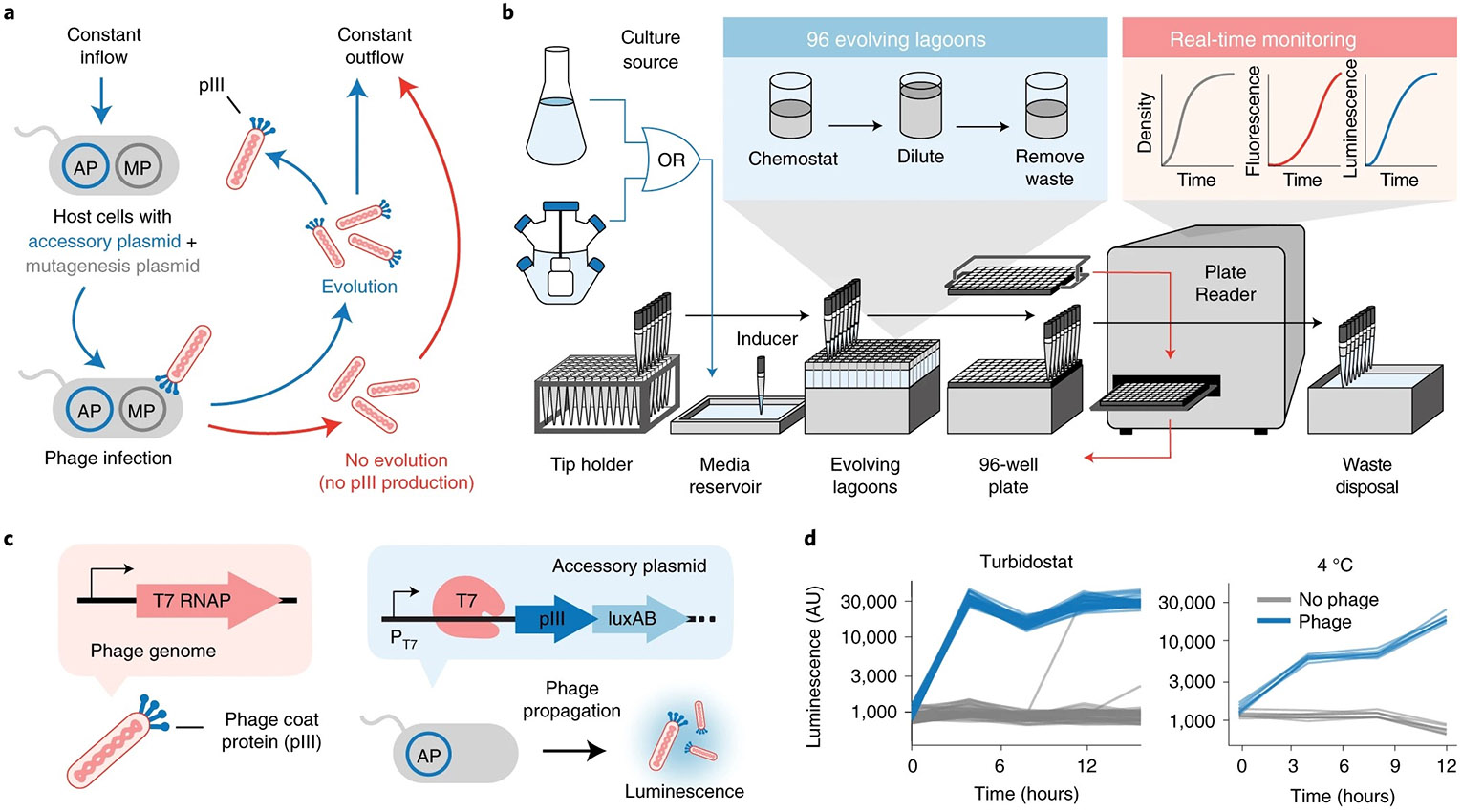

Fig. 1 ∣. Design and validation of high-throughput evolution.

a, Overview of continuous evolution. b, PRANCE method summary for up to 96 simultaneous experiments. Movements by robotic pipette (black arrow) and plate reader interactions (red arrow) are shown. c, Propagation of T7 RNAP-encoding phage on bacteria expressing pIII and luxAB driven by a T7 promoter. d, Real-time monitoring of T7 RNAP-expressing phage propagation by monitoring activity-dependent luminescence monitoring from cultures sourced either from a turbidostat (left) or from a culture stored at 4 °C (right). AU, arbitrary units.

Results

Development of a systematic evolution platform.

We began by developing a 96-well plate-based method, wherein 500-μ1 cultures of evolving M13 bacteriophage (Fig. 1a) are serially diluted with fresh host bacteria twice per hour using an automated liquid handler (Fig. 1b). To enable the pipetting speeds required to approximate continuous flow, we developed a robotic Python interface22 that precisely times the distribution of bacteria, the addition of chemical stimuli, the sampling of populations for real-time monitoring and historical sample preservation (Extended Data Fig. 1). Integrated real-time measurement of luminescence, fluorescence and turbidity enables activity-dependent fitness tracking, which we show is more precise than monitoring turbidity alone15 (Extended Data Fig. 2), Thus, a fluorescent or luminescent reporter can be coupled to either the presence of phage or to the direct activity of the evolving biomolecule itself. We refer to this platform as PRANCE.

Each evolution round is initiated by sterilizing a bacterial culture reservoir (Extended Data Fig. 3) and adding culture to each population (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1b). Bacterial cultures can be sourced from an active turbidostat or chemostat, enabling high-volume experiments, or from preprepared bacterial stock stored at 4 °C, enabling experiments that use many bacterial cultures (Fig. 1b). Accessory molecules (for example, chemical mutagens, stimuli, small molecules) are then pinned to each population, which are monitored in real time by an integrated, automated plate reader that measures not only the population density, but also the fluorescence and luminescence of each population at discrete 30-min intervals. Samples are preserved in 96-well format and retained for downstream analyses such as sequencing of accumulated changes, or in vitro and in vivo activity measurements (Fig. 1b). The system also incorporates error handling, failure-mode prevention and wireless experimenter communication, (Extended Data Fig. 4), and is optimized for minimal human intervention (Extended Data Fig. 1c,d). The fast iteration time of PRANCE enables dozens of rounds of evolution per day, comparable to traditional PACE, with the ease and throughput of a plate-based format.

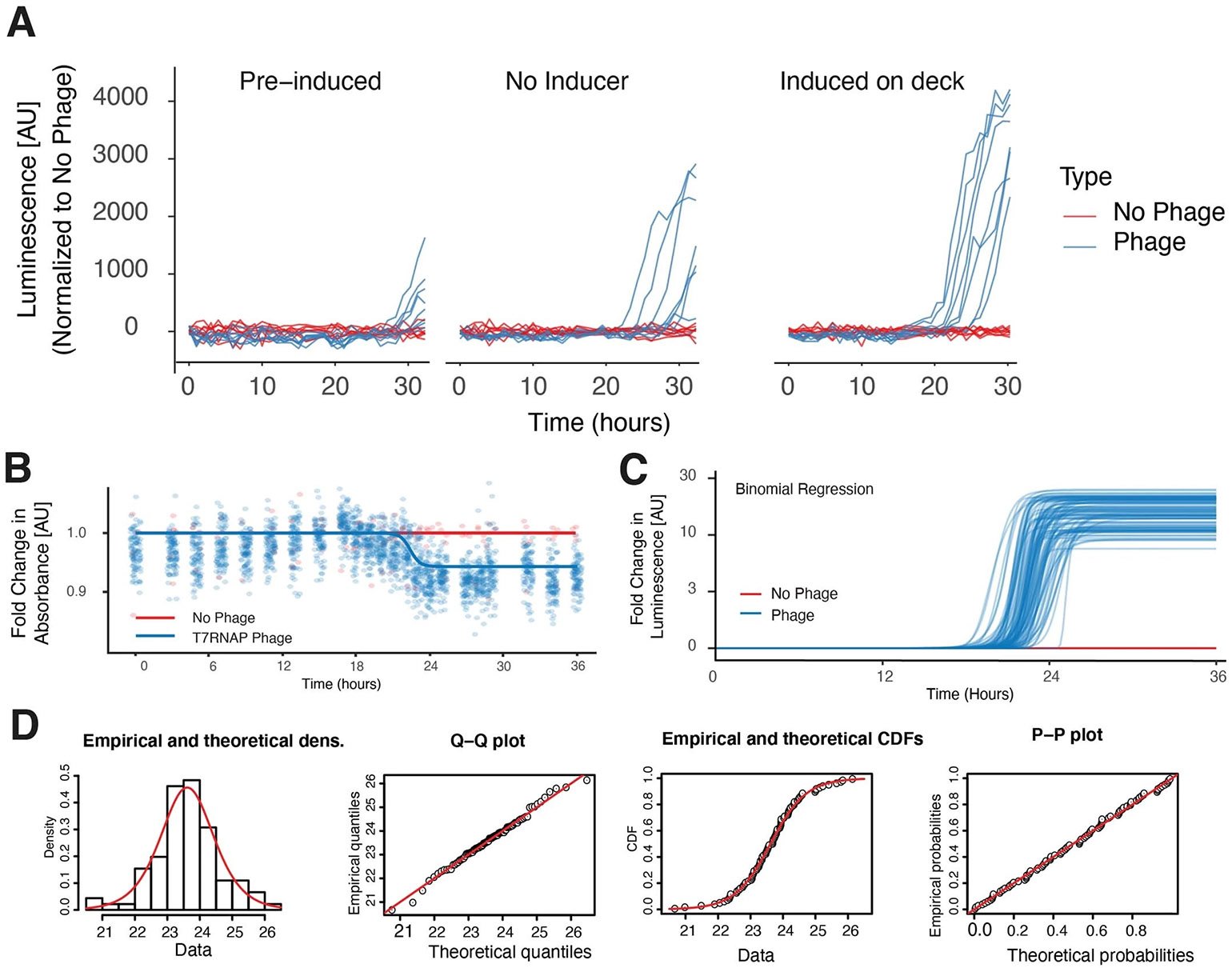

We first demonstrated the real-time activity-monitoring capability by propagating M13 bacteriophage encoding T7 RNA polymerase (RNAP) in place of the pIII phage coat protein using host bacteria expressing pIII and a luminescence reporter (luxAB) under the control of a T7 promoter in 48 independent populations (Fig. 1c). We observed T7 RNAP-dependent luminescence in all samples in less than 4 hours from both 37 and 4 °C culture (Fig. 1d), showing that PRANCE can reproducibly monitor real-time reporters of fitness.

Multiplexing identifies previously inaccessible genotypes.

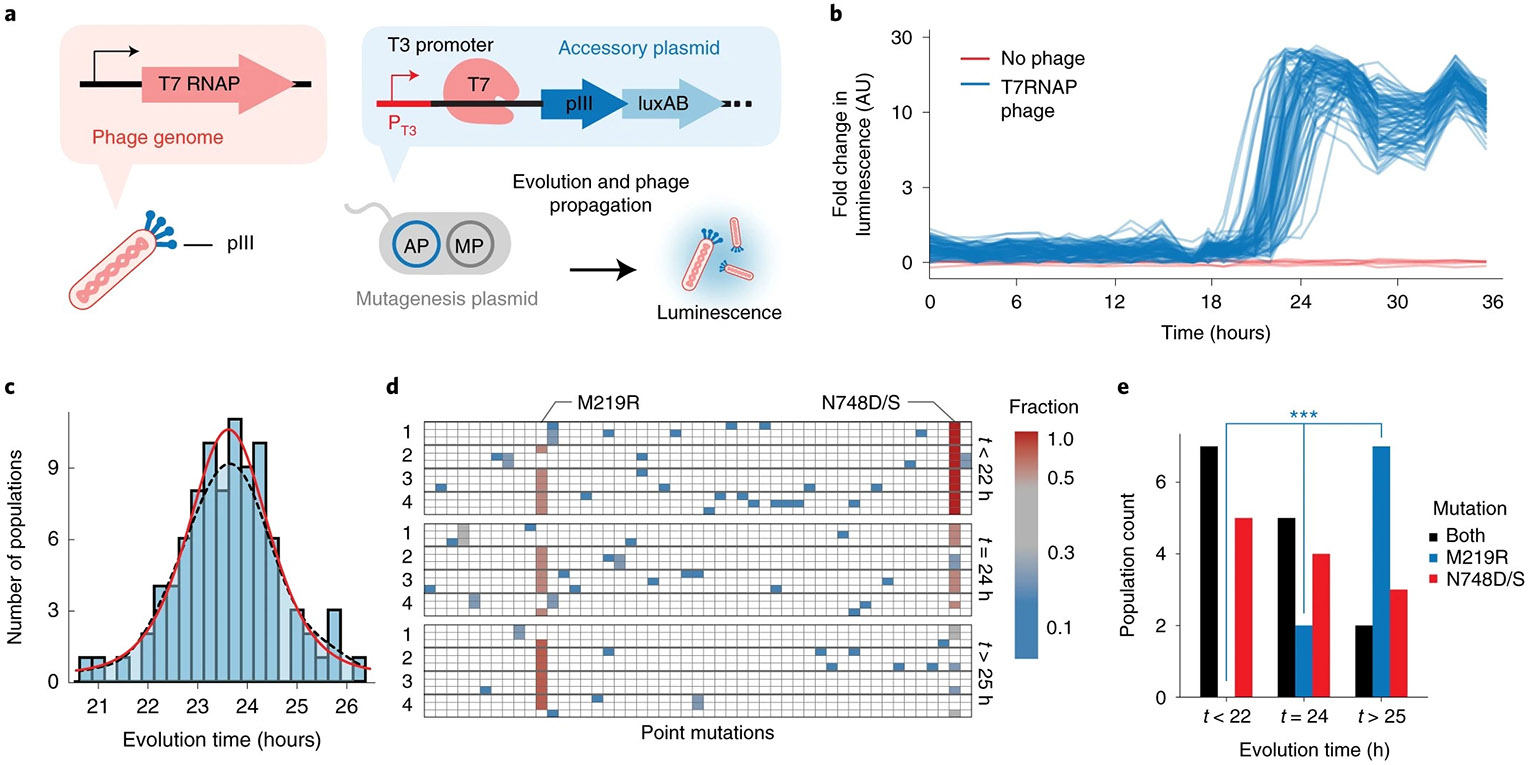

While current directed evolution methods suffice when the primary goal is to engineer a single functional protein, they are limited in their ability to probe the randomness and reproducibility of any given biomolecule evolution and characterize the ensemble of possible outcomes. We wondered if a well-studied evolution5,10,11 could provide new outcomes if sufficiently sampled. First, to measure the stochasticity of evolution, we evolved the T7 RNAP to initiate on the T3 promoter and performed the evolution in 90-plex. In this experiment, host bacteria contain an inducible mutagenesis plasmid24 and an accessory plasmid-containing pIII and luxAB under the control of the T3 promoter (Fig. 2a). With 500-μl populations typically harboring 108 infected cells per ml experiencing high mutagenesis, each population should traverse single-mutation fitness valleys to explore a large fraction of double mutants each day24. We inoculated 96 total populations with or without T7 RNAP-expressing ΔpIII phage (with six no-phage controls) and tracked their progress in real time with luminescence (Fig. 2b). We found that bacteria sourced from 4 °C and mutagenized on-deck perform similarly (Extended Data Fig. 5a) and tracked absorbance depression (Extended Data Fig. 5b). This high-throughput exploration of the evolution of the T7 RNAP, with >5× more parallel populations than the largest previously reported experiment10, allowed us to measure the frequency and reproducibility of the emergence of different genotypes. Both novel and previously reported mutations were observed. In addition, we quantified the elapsed evolution times and found the distribution to be logistically distributed (goodness of fit, CvM stat 0.017, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test 0.046) (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 5c,d), consistent with only a single mutation (N748D/S or M219R) being required for improved activity (Fig. 2d). The single M219R mutation, which exhibits substantially delayed emergence relative to N748D (chi-square P=0.0037) (Fig. 2e), has not been previously reported despite the many previous iterations of the T7 RNAP evolution. This may be partly due to N748D/S resulting from a transition mutation (A → G), whereas M219R results from a transversion mutation (T → G), which occurs less frequently24. Thus, systematic high-replicate evolution allows for the extensive profiling of evolutionary reproducibility20 and enables deeper sampling of less accessible genotypes that cannot be readily identified from a single population.

Fig. 2 ∣. Quantifying the stochasticity of biomolecular evolution.

a, Strategy for evolving T7 RNAP to recognize the T3 promoter, in which expression of pIII is driven by the T3 promoter on an accessory plasmid and the evolving T7 RNAP is encoded on the replicating phage genome. b, Real-time luminescence monitoring of 90 simultaneous populations with six no-phage controls. c, Histogram of times required to acquire mutations permitting the T7 RNAP to recognize the T3 promoter, obtained from the inflection point of logistic regressions of each population (Extended Data Fig. 5, Methods and Data analysis). Smoothed fit is calculated with a kernel density estimate (black dashed line) or logistical distribution fit (red). d, Mutations observed from 12 representative populations that exhibited evolution of early (−1σ, t < 22 h), mid (mean, t = 24 h) and late (+1σ, t > 25 h) time points. Three clonal phage from each population are shown, filled-in boxes indicate a mutation at a given location and are colored by ‘fraction’ referring to the mutational frequency within the given time window (t < 22, t = 24, t > 25), where red is 12/12 clones, blue is 1/12 of the clones. Genotypes of subclones are listed in Supplementary Table 2. e, Frequency of mutations arising that exhibited evolution of early (−1σ, t < 22 h), mid (mean, t = 24 h) and late (+1σ, t > 25 h) time points. *** indicates time-dependent chi-square P = 0.0037.

Miniaturization enables reagent-limited evolution.

As traditional PACE uses continuous flow to constantly refresh host bacteria and consumes large quantities of media, it has previously been infeasible to evolve biomolecules in environments that require small molecules that are difficult to synthesize or are new25. PRANCE reduces each bioreactor volume by 100-fold, thus making small molecule-dependent environments more feasible and controllable. To demonstrate these capabilities, we modified an established evolution of the pyrrolysine aminoacyl-synthetase (PylRS) to incorporate noncanonical amino acids (ncAAs)26, using substantially lower quantities of ncAAs than previously reported. To enable multiplexing of diverse transfer RNA (tRNA)–PylRS pairs, we encoded a PylRS variant and a UAG-containing tRNAPyl within the M13 phage genome and inserted a UAG amber stop codon within the pIII phage coat protein along with a luciferase reporter expressed from host bacteria (Fig. 3a). Thus, phage proliferation and luminescence are both directly coupled to suppression of the UAG amber codon via ncAA incorporation (Fig. 3b).

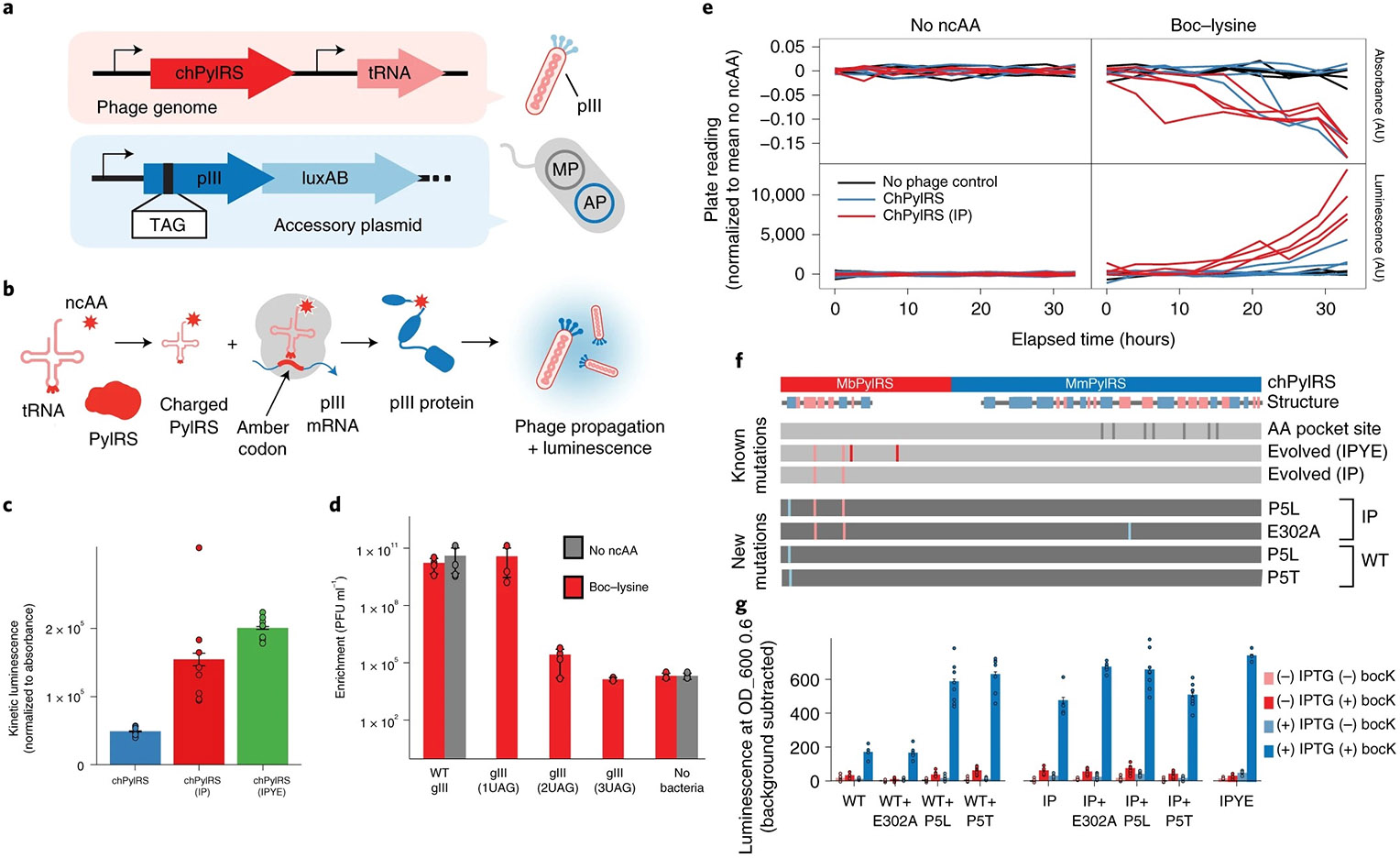

Fig. 3 ∣. Controlling the chemical environment in high-throughput evolution.

a, Strategy for evolving AARSs and tRNAs to incorporate noncanonical amino acids. TAG amber codons are inserted into the pIII protein, and the evolving tRNAPyl and chPylRS are encoded in the evolving phage genome. b, Phage propagation and luminescence are contingent on the successful incorporation of ncAAs into pIII. c, Efficiency of unevolved versus evolved chPylRS variants (IP, IPYE mutations) at incorporating Boc-lysine into an inducible TAG-luxAB reporter, normalized to no-ncAA and no-IPTG controls. Data are presented as mean values ± s.e.m. for n = 8 biologically independent samples. d, Quantifying the selection stringency of incorporating one, two or three ncAAs into pIII, in either the presence or absence of Boc-lysine, using the evolved variant chPylRS-IPYE. Data are presented as mean values ± s.e.m. for n = 4 biologically independent samples. e, Real-time absorbance depression and luminescence monitoring beginning from either the unevolved state (chPylRS, blue) or an intermediate evolved state (chPylRS-IP, red). f, Genotypes of the evolved variants. Phage persisted in all of the chPylRS-IP populations, and clonal phage acquired novel mutations (P5L or E302A). Only half of the chPylRS populations resulted in persistent phage propagation at 36 h; each acquired a distinct mutation at the same N-terminal proline residue (P5L or P5T) within the conserved essential N-terminal domain of PylRS44,45. g, Efficiency of evolved variant mutations in both chPylRS and chPylRS-IP at incorporating Boc-lysine into an inducible TAG-luxAB reporter, compared to no-ncAA and no-IPTG controls. Data are presented as mean values ± s.e.m. for n = 8 biologically independent samples.

We used three pyrrolysine synthetases—chPylRS, an evolution intermediate (chPylRS-IP)26 and an evolved variant (chPylRS-IPYE)26—and quantified their ability to incorporate Boc-lysine as measured by ncAA-dependent kinetic luminescence activity (Fig. 3c) and amber codon-dependent phage enrichment (Fig. 3d). We then used PRANCE to evolve the PylRSs to incorporate Boc-lysine by inoculating eight populations with phage encoding either chPylRS and chPylRS-IP in quadruplicate. Aminoacyl-synthetase (AARS) evolution is prone to the emergence of ‘cheaters, that is promiscuous charging of canonical amino acids27. To monitor the emergence of nonspecific AARSs, we included eight populations with phage encoding each variant but in the absence of ncAAs; phage propagation under these conditions would indicate the evolution of nonspecific charging of canonical amino acids. Together, we monitored luminescence and absorbance across a total of 24 populations over 36 h of evolution. We observed propagation of both chPylRS- and chPylRS-IP-encoding phage in the presence of Boc-lysine (Fig. 3e), and identified novel genotypes with previously unidentified mutations (Fig. 3f,g). The lack of luminescence in the absence of ncAA indicates that cheater AARSs are unlikely to emerge under the evolution conditions used (Fig. 3e). Thus, the inclusion of control populations—typically neglected in directed evolution experiments due to throughput limitations—enabled the extraction of additional information previously unobtainable. This capability can be used to determine whether or not negative selection against promiscuous activity26 is necessary. Additionally, the automated addition of Boc-lysine to 12 evolving populations over 36 h of PRANCE consumed less than 100 mg of total compound, nearly ten times less than what would have been required for a single population within a bioreactor. Given this substantial reduction in reagents, PRANCE enables multiplexed and well-controlled evolution experiments with fine control over the chemical environment using molecules that are too expensive (for example, 4-azido-Phe, $2,500 per gram28) or rare (for example, pyrrolysine29) to be used with traditional continuous-flow bioreactors.

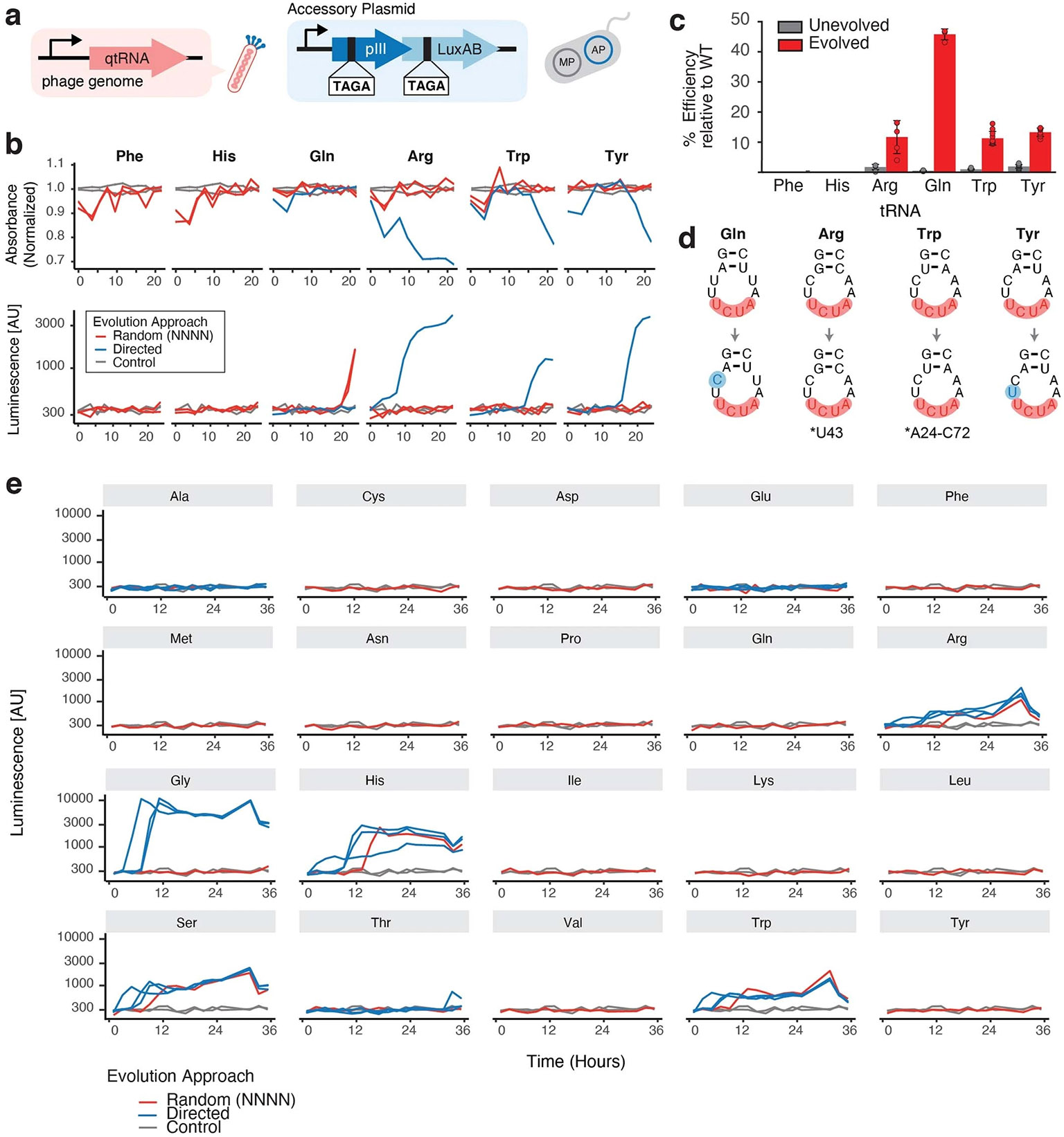

Simultaneous evolution of dozens of biomolecules.

Previously, we used PACE to evolve tRNAs30 capable of decoding quadruplet codons31,32 toward the goal of engineering a four-base codon translation system33,34. To evolve new quadruplet tRNAs (qtRNAs), we inserted a quadruplet codon (AGGG) into pIII and generated a variety of qtRNA-encoding, pIII-deficient phage (Fig. 4a). In the absence of a functional qtRNA, the quadruplet codon generates a frameshift, truncating pIII and precluding phage propagation (Fig. 4b). The success of qtRNA evolution can depend on which tRNA paralog is used to initiate evolution, highlighting the importance of studying a variety of starting genotypes. Here, we used PRANCE to simultaneously identify many functional qtRNAs by subjecting a full set of 20 different paralogs to evolution within a single experiment. We first replicated the evolution of six TAGA-decoding qtRNAs, and observed similar genotypes as previously described30 (Extended Data Fig. 6). Next, we initiated PRANCE by seeding 48 populations in an optimized configuration (Extended Data Fig. 7) with phage encoding 20 different qtRNA paralogs corresponding to every canonical amino acid containing a library of randomized anticodons (NNNN) (20 populations); phage encoding eight different qtRNA paralogs (Ala, Glu, Gly, His, Arg, Ser, Thr and Trp) each with directed AGGG frameshift anticodons (24 populations) or no-phage controls (four populations).

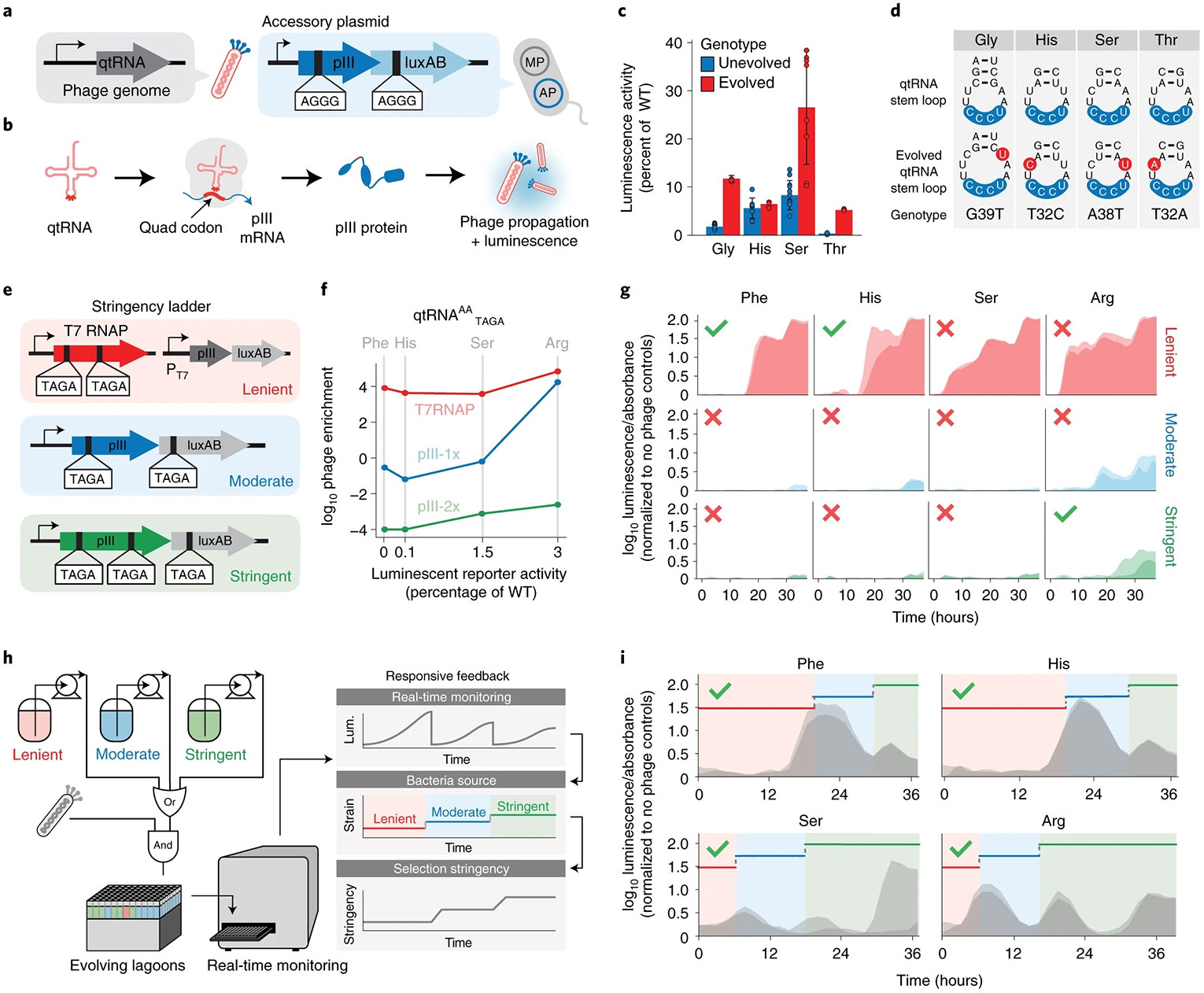

Fig. 4 ∣. Feedback-controlled evolution of diverse starting genotypes.

a, Strategy for evolving qtRNA to recognize quadruplet codons. AGGG quadruplet codons are inserted into the pIII protein and luxAB, and the evolving qtRNA are encoded in the evolving phage genome. AP, accessory plasmid. b, Phage propagation and luminescence are contingent on the successful decoding of the quadruplet codons in the pIII and luxAB proteins. Failure to decode a quadruplet codon results in premature termination and truncated protein. c, Efficiency of evolved versus unevolved qtRNA at incorporating amino acids compared to a triplet codon. d, Initial and evolved qtRNA genotypes. Data are presented as mean values ± s.e.m. for n = 3–8 biologically independent samples. e, Strategy for evolving qtRNAs with increasing stringency of selection (red/lenient, T7 RNAP; moderate/blue, pIII-1x; stringent/green, pIII-2x). f, The transfer function that determines the efficiency of phage propagation as a function of biomolecule activity for each AP, measured using phage-bearing qtRNAs at different starting activities (Phe, His, Ser, Arg). Starting activity is quantified as percentage of WT, or the luminescence generated by coexpressing the qtRNA and luxAB-357-TAGA, relative to an all-triplet luxAB. g, Evolution of four qtRNAs on APs with varying stringencies (successful evolution indicated by green checkmarks). h, In a feedback experiment, three bacterial strains with increasing stringency are added to phage populations and monitored in real time. The bacteria source for each well is adjusted in response to real-time luminescence measurements to automatically increase stringency of the environment. i, Real-time luminescence measurements of evolving qtRNAs with feedback-controlled selection stringency intervals.

We then tracked luminescence of all 48 populations over 36 h and found that phage encoding Gly, His, Ser, Arg, Thr and Trp qtRNA paralogs successfully decoded quadruplet codons (Extended Data Fig. 6e). Indeed, when subcloned, several of the isolated qtRNAs exhibited improved activity (Fig. 4c,d), although further characterization would be required to determine the amino acid identity of the evolved qtRNAs34. These results are consistent with the observation that only some tRNAs are capable of improvements to this biomolecular activity, highlighting the importance of genotype diversification in the success of evolution. Notably, a single PRANCE experiment evolved multiple AGGG-decoding qtRNAs, which would have previously required dozens of individual PACE experiments.

Feedback evolution of activity-diverse biomolecules.

Although we successfully identified AGGG-decoding qtRNAs with improved activity, we also observed a high failure rate. Many of the qtRNAs with low initial activity (Ala, Cys, Asp, Phe and so on) never evolved, but rather experienced an experimental failure mode referred to as ‘washout’ in which the effective population size decreases to zero (Extended Data Fig. 6e). Additionally, we observed that qtRNAs with high initial activity (Arg, Trp) maintained population size and triggered luminescence but did not acquire mutations. These results indicate that selection was too stringent in some cases and too lenient in others—both common directed evolution failure modes. We hypothesized that the ability to dynamically tune selection stringency in accordance with population fitness would improve the likelihood of successfully evolving biomolecules from diverse starting points, by both reducing the possibility of phage washout and maintaining selection pressure on high-activity variants. To improve likelihood of evolution success, we developed a feedback control system35,36 that adjusts the stringency of selection by modifying the host bacterial strain in response to a real-time analysis of molecular activity-dependent luminescence. As a model system, we selected four qtRNA paralogs (Phe, His, Ser and Arg) that decode the TAGA quadruplet codon, are known to have improved variants and differ greatly in initial activity. We sought to use feedback control to evolve all four qtRNAs in a single experiment.

First, we characterized three bacterial APs that confer different levels of selection pressure. The most ‘lenient’ of these APs encodes T7 RNAP containing two quadruplet codons, with the T7 promoter driving production of pIII and luxAB (Fig. 4e). We also characterized more stringent APs containing either one (moderate) or two (stringent) quadruplet codons directly in pIII (Fig. 4e) and found that these APs adequately cover phage enrichment space (Fig. 4f). We next evolved these qtRNAs on each of the three individual bacterial sources separately, under static selection. The variant with the highest initial activity, , only evolves under high selection pressure. Conversely, under lenient pressure all phage propagate, but only the qtRNAs with the lowest initial activity experience selection and acquire mutations (Fig. 4g). None of the three levels of stringencies could evolve all four qtRNAs. To customize selection pressure, we implemented automated feedback control in which the bacterial source of each population is adjusted in response to real-time measurements of fitness as measured by luminescence (Fig. 4h and Methods). This strategy successfully propagated phage populations encoding all four qtRNAs to the end of the 36-hour experiment (Fig. 4i). Additionally, by measuring clonal variant activity from each of the eight feedback-controlled populations using a luciferase reporter, we found that all eight populations had evolved qtRNA variants with improved translation efficiency (Fig. 5a). Thus, feedback control avoided phage washout in all cases while simultaneously exposing high-activity qtRNAs to more challenging evolution environments, in a short time window, without researcher intervention. These results demonstrate that feedback control is more robust and less failure prone, enabling the evolution of biomolecules with diverse activities.

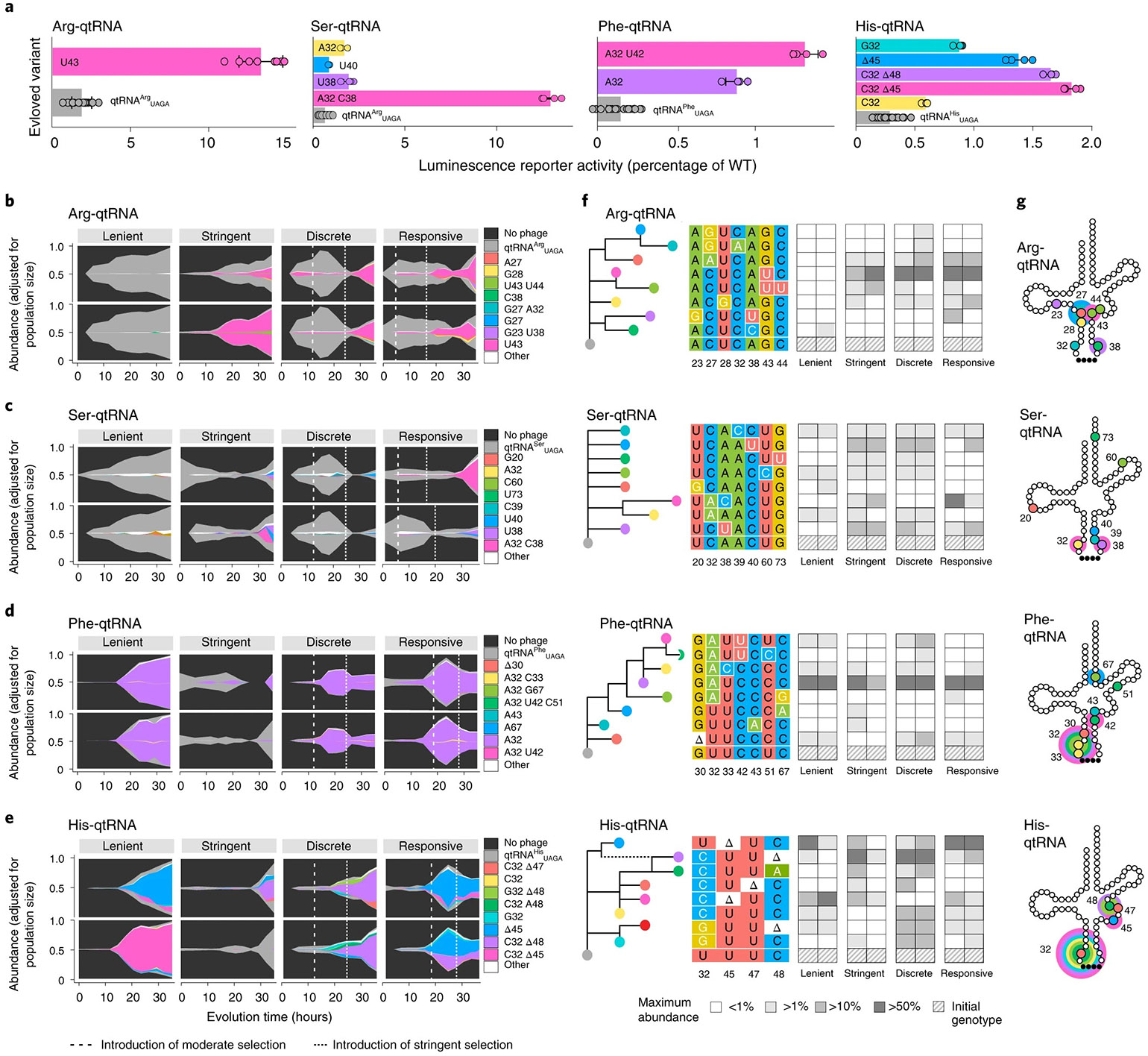

Fig. 5 ∣. Varying the timing of environmental changes yields diverse evolution trajectories.

a, Relative activity of the initial and evolved variants as measured by a kinetic luminescence assay. Data are presented as mean values ± s.e.m. for n = 3–8 biologically independent samples. b–e, Muller plots as abundance adjusted for population size for Arg-qtRNA (b), Phe-qtRNA (c), Ser-qtRNA (d) and His-qtRNA (e). The dashed line shows the introduction of moderate selection and the dotted line shows the introduction of stringent selection. f, Predicted phylogenetic relationship of the variants arising from evolution of each qtRNA, and their respective maximum population abundance between replicates. g, Location of mutations within the standard qtRNA secondary structure. The colors of variants arising in each evolution are consistent with the legends in Fig. 6b-e.

Evolution outcomes are determined by temporal dynamics.

It is well established that selection stringency can affect the trajectory of evolution10,19, but the importance of the timing of those changes has remained largely unexplored. In nature, changes in the physical environment are complex, and can be random or even exhibit mutual dependence with population fitness (for example, in predator-prey dynamics37). Thus, we wondered how static versus dynamic selective environments would affect the trajectory of single-biomolecule evolution within the laboratory. Due to the small size of qtRNAs, we used next-generation sequencing to characterize the evolutionary history of 32 populations as they were subjected to different temporal perturbations to their selective environment. We tracked the genotypic abundance relative to population size of four qtRNA paralogs over 36 hours, under four selection schedules in duplicate as they underwent evolution under static (lenient or stringent), dynamic yet unresponsive (discrete) or feedback-controlled (responsive) stringency modulation.

We found that the selective environment affects whether and how quickly evolved variants reach fixation in a population. For example, the variant U43 can only be evolved using stringent selection because the tRNA genotype initiating that evolution has high initial fitness (Fig. 5a,b). Accordingly, all evolution experiments arrive at a convergent solution, but the speed of evolution depends on how quickly the stringent selective environment is introduced (Fig. 5b). Further, , , and are each vulnerable to washout at high stringency due to lower overall fitness (Fig. 5c-e); thus, evolution only occurs for these qtRNAs in environments that are initially lenient. During evolution, an accessible and convergent single-point mutant (32 A) arises that is highly fit in lenient and moderate selective environments, resulting in purification and population size growth in those environments (Fig. 5d). The evolution is more complex, containing several variants with elevated fitness composed of mutations to base 32 together with modifications in the variable loop (Fig. 5e,g). Finally, the synergistic epistasis between mutations in (Fig. 5a) makes purification of the highly improved A32-C38 mutant31 less robust: only one responsive environment completely purified this variant (Fig. 5c). Together, these data show how the unique fitness landscape of each biomolecule determines the dynamics of its evolution in different selective environments.

We also observed that the dynamics of environmental changes can affect the phylogenetics of evolution. Unlike Arg and Phe-qtRNA evolution, which each appear to deterministically converge on particular high-activity variants irrespective of changes in stringency timing (Fig. 5b,d), we found that the genotypes resulting from evolution are particularly sensitive to historical changes in the environment. The discrete selection schedule resulted in wide genotypic variety, with seven unique genotypes each reaching >10% of phage population share at some point during evolution (Fig. 5f). In this schedule, the arbitrary introduction of moderate stringency (t = 12 h) reproducibly enriches intermediately active variants (C32 or G32) and their phylogenetic descendants with variable loop mutations (G32-Δ48, C32-A48, C32-Δ48, C32-Δ47) (Fig. 5g), before converging on a globally optimal variant. Conversely, we see that during responsive evolution, where moderate stringency is delayed until the population is sufficiently fit (t = 18 h), a single active point mutant (Δ45) emerges as the predominant variant without widely exploring other genotypes at high population abundance (Fig. 5e,f). These data show that seemingly small perturbations to the historical selective environment, whether arbitrary or in response to a changing ecosystem, can drive purification of distinct genetic variants that are either moderately or highly fit38. Collectively, these results demonstrate that although single-biomolecule evolution may appear deterministic on simple fitness landscapes with a sharp peak, more complex landscapes may produce outcomes contingent on seemingly inconsequential events21.

Long-running evolution with PRANCE.

The longevity of most PACE experiments (>100 hours) requires the platform to be capable of performing long-running, multi-trajectory evolution experiments. Due to the large quantities of consumables used by liquid-handling robots, the need for frequent researcher intervention (for tip-replenishing) and the ongoing tip shortage resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic39, we developed an optimized method capable of sterilizing and reusing tips on the robot deck (Supplemental Video 1). This optimized method uses approximately five boxes of tips per day, and can be run for over a week at a time with user intervention only once every 24 hours. During method optimization, we observed that different robotic configurations introduce varying amounts of cross-contamination when propagating highly active phage (Extended Data Fig. 8a,b). To demonstrate the capabilities of this method, we first validated that tip reuse and sterilization introduced no quantifiable cross-contamination within 12 hours (Extended Data Fig. 8c), indicating that tips could be replenished once or twice per day.

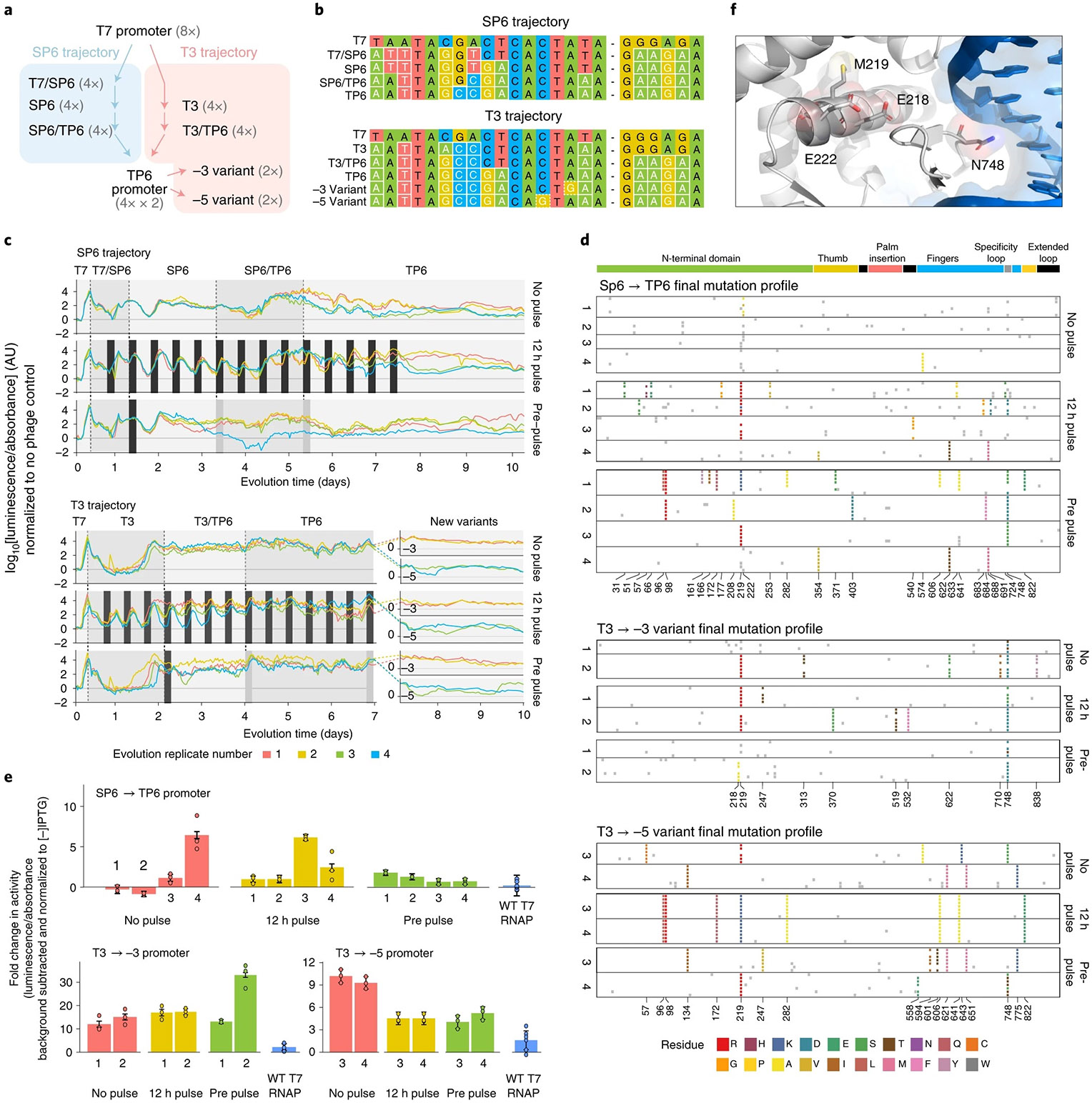

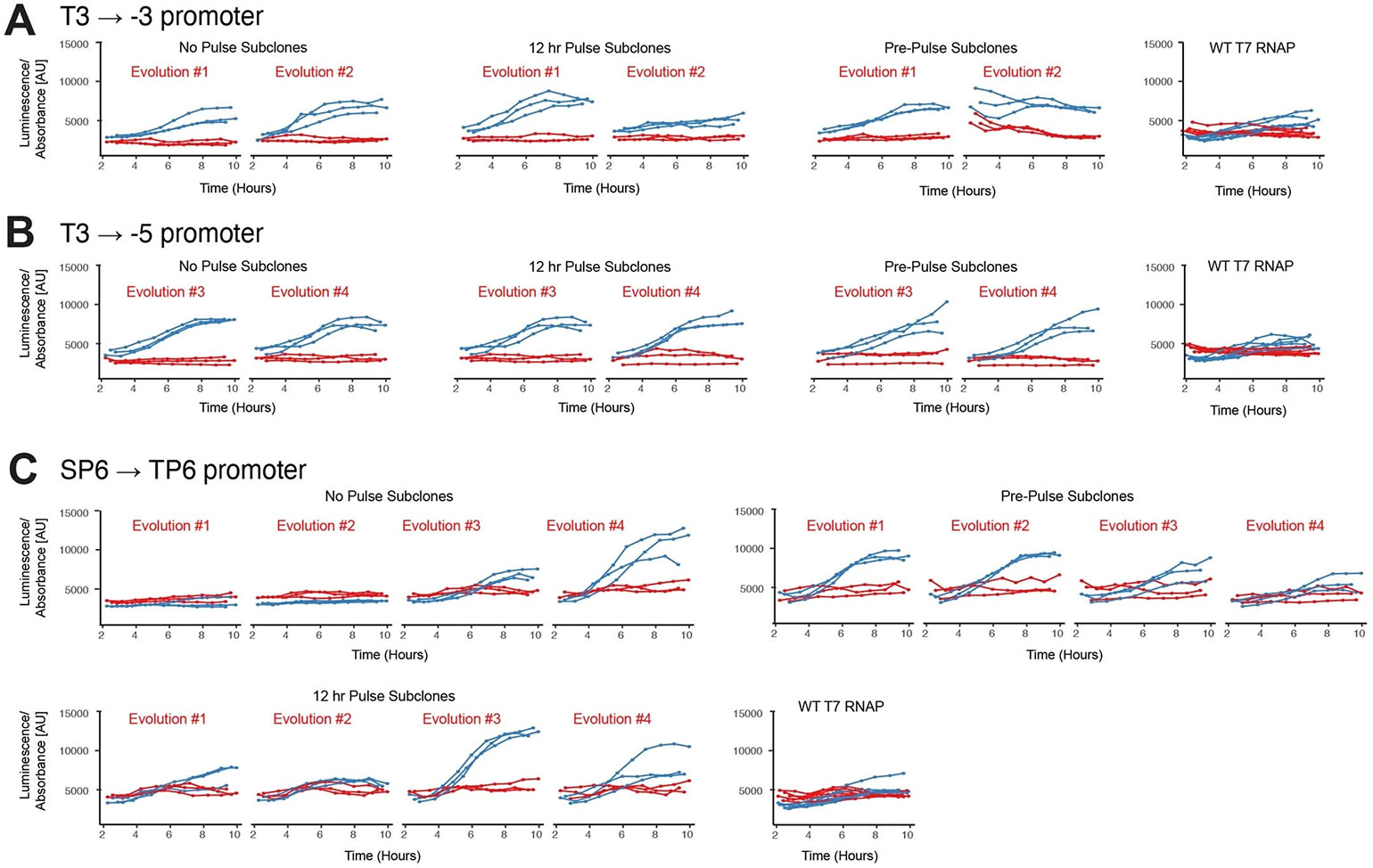

We then used this technique to enable a 10-day evolution in which we evolved T7 RNAP to bind eight new promoters (Fig. 6a,b). During this experiment, we tested three techniques to maintain large population sizes during long-running experiments: allowing the evolution to proceed without intervention (no pulse); spiking the population with bacteria expressing pIII under the phage shock promoter (psp) that enable activity-independent phage propagation periodically every 12 h (12 h pulse) or spiking only before transitions to new evolution stringency (pretransition pulse). We evolved 32 populations for 240 hours (10 days) in a single, uninterrupted experiment (Fig. 6c). During this time, no cross-contamination in the eight no-phage control wells was detected. We found that the phage titer maintenance schemes affected the genotypes that evolved (Fig. 6d). To quantify activity, individual variants containing all of the dominant mutations from each replicate (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Table 3) were subcloned into plasmid reporter constructs in which LuxAB was driven by the TP6, −3 variant or −5 variant promoter. The activities of 24 total subclones were then quantified by luminescence and compared to wild-type (WT) T7 RNAP on each respective promoter (Fig. 6e and Extended Data Fig. 9). Most variants obtained in the T7 → T3 → −3/−5 trajectories were found to exhibit between 10 and 20-fold higher activities than WT T7 RNAP on the same promoter. In addition, we found that the stringency conditions interacted with the evolution goals; for example, the reduced population size of ‘No pulse’ in the SP6 trajectory was the only condition that converged on mutations to E222, a residue associated with nonspecific promoter binding11 (Fig. 6e). The highest activity variant obtained from −3 variant evolution (prepulse, population no. 2, Fig. 6e) was also the only population to reach saturation with a novel E218A mutation even though many populations obtained the M219R/K solutions described above (Fig. 6f). Thus, PRANCE enables the seamless exploration of complex, multi-mutational pathways that evolve over the course of many days and require several intermediate evolution goals.

Fig. 6 ∣. Long-term evolution.

a, Thirty-two populations of phage encoding T7 RNAP were evolved to bind new promoters. Evolution proceeded first along two different paths, being challenged to bind either SP6 or T3-derived promoters. All populations were then evolved to bind the TP6 promoter. The 16 populations that traversed the T3 path were then split in half and challenged to bind novel promoters with mutations at highly conserved −3 or −5 locations. b, Genotypes of the promoters used in this evolution. Changes from the WT T7 promoter are highlighted. c, Real-time monitoring of the 48 populations undergoing three different stringency management schemes in which psp-pIII bacteria are periodically spiked into populations for 3-h intervals (dark gray bars) to increase population size. d, Genotypes of subclones obtained from each population (replicate populations labeled 1–4) from each evolution trajectory with each of the three stringency management schemes. Dominant (>50% of population) variants are highlighted and colored by their AA mutation. Nondominant (that is background mutations) are shown in light gray. The x axis is annotated by dominant mutations that appear within a given trajectory. e, Normalized luciferase activity of individual subclones from populations (1-4) from each trajectory, compared to WT T7 RNAP (blue). Luciferase reporter vectors are driven by the TP6 promoter, −3 variant promoter and −5 variant promoters. Data are presented as mean values ± s.e.m. for n = 3 biologically independent samples. Genotypes of subclones are listed in Supplementary Table 3. f, E218, M219 and E222 in the WT T7 RNAP structure (PDB 1CEZ, ref. 46), near the promoter specificity loop.

Discussion

PRANCE provides a number of advances over existing methods. The platform has higher throughput, supporting hundreds of diverse evolution conditions simultaneously. The 100× volume reduction and robotic compound pinning capabilities support evolution in chemical environments that were not previously practical due to reagent cost28 or synthesis limitations29, e.g., those involving the use of small-molecule fluorescent reporters of metabolism40, pH41 or CO242, or supplementation with complex intermediates43. Further, the system can be used with either continuously grown or chilled host cells to enable evolution at diverse temperatures. The universal 96-well format enables sample preservation for immediate or downstream analysis of historical genotypic and phenotypic changes. Additionally, the system is capable of performing feedback-controlled evolution: we demonstrated feedback control triggered by luminescence, and the system is extensible to many activity-dependent fluorescent reporters (transcription, quorum sensing, solubility, protease activity, splicing and so on) as well as any measurement that can be integrated robotically, such as PCR, binding measurements or orthogonal in vitro assays. Similarly, the system is amenable to experimentation with other feedback control algorithms35 or machine learning-guided adaptive control. With the improved availability and decreasing cost of high-throughput equipment, this approach is an increasingly accessible option for many laboratories. Finally, although we demonstrate the use of this platform with bacteriophage, we believe that it is practicable to accommodate continuous evolution platforms in eukaryotes such as yeast9,15 or possibly mammalian–virus systems6,7.

From a strictly engineering perspective, our results highlight how multiplexed evolution enables engineering that is comprehensive, robust and systematic. With PRANCE, we sampled all parameters known to affect evolution outcomes: the initial genotype, the evolution environment and events that happen by chance. Evolution in high throughput thus improves our ability to sample the ensemble of possible outcomes. For example, even though the evolution of T7 RNAP has been extensively reported5,10,11, we continued to identify novel genotypes with systematic parallel sampling. We observed that initiating experiments with a diverse set of tRNA paralogs was a robust strategy for evolving highly active variants and further identified that feedback control enables side-by-side evolution of biomolecules with diverse initial activity, in the absence of preexisting knowledge. Finally, we found that populations evolving with differentially timed stringency perturbations can yield distinct solutions, highlighting the use of examining many evolution schedules. By improving the reliability of laboratory evolution, PRANCE enables the reinvention of directed evolution as a more robust and reproducible engineering discipline.

Systematic evolution could be of great use to disciplines ranging from natural evolution to epidemiology. Indeed, this platform is capable of collecting datasets about molecular evolution that approach the size and scope of the long-term evolution experiment dataset of whole-genome evolution1,2 by examining numerous individual populations and environments over many generations. By performing a single evolution with many replicates, we can characterize the reproducibility and stochasticity of single events, a longstanding challenge for evolutionary biologists. As selection schedules reconstitute the natural process of evolving related biomolecules in different selective environments, PRANCE also offers the opportunity to better understand the relationship between time, stringency, the environment and the traversal of a fitness landscape. More generally, the ability to systematically explore evolutionary outcomes across many populations may help resolve controversial questions in evolutionary biology, such as the friction between determinism and contingency. For example, we find that the timing as well as the nature of environmental changes can reproducibly affect the genotypic outcomes of individual biomolecules (that is, contingency), but outcomes vary according to the particular selective landscape (that is, determinism). Thus, PRANCE provides the opportunity to answer fundamental questions in evolutionary biology, recapitulate naturally occurring environmental changes and simulate perturbations to these environments—all within the laboratory.

Methods

See Supplementary Table 4 for part numbers and all plasmids used in these experiments.

Plaque assays.

Manual plaque assays.

S2060 cells were transformed with the accessory plasmid of interest. Overnight cultures of single colonies grown in 2XYT media supplemented with maintenance antibiotics were diluted 1,000-fold into fresh 2XYT media with maintenance antibiotics and grown at 37 °C with shaking at 230 r.p.m. to an optical density (OD600) of roughly 0.6–0.8 before use. Bacteriophage were serially diluted 100-fold (four dilutions total) in H2O. Then, 100 μl of cells were added to 100 μl of each phage dilution, and to this 0.85 ml of liquid (70 °C) top agar (2XYT media + 0.6% agar) supplemented with 2% Bluo-Gal was added and mixed by pipetting up and down. once. This mixture was then immediately pipetted onto one quadrant of a quartered Petri dish already containing 2 ml of solidified bottom agar (2XYT media + 1.5% agar, no antibiotics). After solidification of the top agar, plates were incubated at 37 °C for 16–18 h. See Supplementary Table 4 for catalog numbers.

Robotics-accelerated plaque assays.

The same procedure was followed as above, except that plating of the plaque assays was done by a liquid-handling robot (Hamilton Robotics) by plating 20 μl of bacterial culture and 100 μl of phage dilution with 200 μl of soft agar onto a well of a 24-well plate already containing 235 μl of hard agar per well. To prevent premature cooling of soft agar, the soft agar was placed on the deck in a 70 °C heat block. Source code from our implementation can be found at https://github.com/dgretton/roboplaque.

Phage enrichment assays.

S2060 cells were transformed with the accessory plasmid of interest as described above. Overnight cultures of single colonies grown in 2XYT media supplemented with maintenance antibiotics were diluted 1,000-fold into Davis Rich Media (DRM) media with maintenance antibiotics and grown, at 37 °C with shaking at 230 r.p.m. to OD600 roughly 0.4–0.6. Cells were then infected with bacteriophage at a starting titer of 105 pfu ml−1. Cells were incubated for another 16–18 h at 37 °C with shaking at 230 r.p.m. Supernatant was filtered (as described) and stored at 4 °C. The phage titer of these samples was measured in an activity-independent manner using a plaque assay containing E. coli bearing pJC175e (as described). A complete list of catalog numbers can be found in the Supplementary Table 4.

Measurement of biomolecule activity using luciferase reporter.

S2060 cells were transformed with the luciferase-based activity reporter and biomolecule expression plasmids. Overnight cultures of single colonies grown, in DRM media supplemented with maintenance antibiotics were diluted 500-fold into DRM media with maintenance antibiotics in a 96-well 2-ml deep well plate, with or without isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) inducer. The plate was sealed with a porous sealing film and grown, at 37 °C with shaking at 230 r.p.m. for 1 h. Next, 175 μl of cells were transferred to a 96-well black-walled clear-bottom plate, and then 600 nm absorbance and luminescence were read using an ClarioSTAR plate reader (BMG Labtech) over the course of 8 h, during which the cultures were incubated at 37 °C.

Equipment set-up for PRANCE.

Media.

DRM26 is used for PRANCE and all experiments involving plate reader measurements due to its low fluorescence and luminescence background. 2XYT media, a media optimized for phage growth, is used for all other purposes, including phage-based selection assays and general cloning. See Supplementary Table 4 for media catalog numbers. Antibiotics (Gold Biotechnology) were used at the following working concentrations: carbenicillin, 50 μg ml−1; spectinomycin, 100 μg ml−1; chloramphenicol, 40 μg ml−1; kanamycin, 30 μg ml−1; tetracycline, 10 μg ml−1 and streptomycin, 50 μg ml−1.

General robotic equipment and configuration.

A Hamilton Microlab STARlet eight-channel base model was augmented with a Hamilton CO-RE 96 Probe Head, a Hamilton iSWAP Robotic Transport Arm and a Dual Chamber Wash Station. Air filtration was provided by an overhead high-efficiency particulate air filter fan module integrated into the robot enclosure. A BMG CLARIOstar luminescence multi-mode microplate reader was positioned inside the enclosure, within reach of the transport arm.

Mini peristaltic pump array.

Up to seven miniature 12-V, 60 ml min−1 peristaltic pumps (fish tank pumps) were actuated by custom motor drivers. A Raspberry Pi mini single-board computer received instructions over a local internet protocol address and commanded the motor drivers via I2C. A complete list of catalog numbers can be found in the Supplementary Table 4.

Bacterial reservoir.

We implemented a self-cleaning bacterial reservoir consisting of the pump array and a custom 3D-printed corrugated reservoir (Extended Data Fig. 1): see Supplementary Table 4 for the .stl file. Following each filling of the bacterial reservoir with fresh bacteria and liquid exchange (below), remaining culture was drained from the reservoir and the reservoir was automatically rinsed with 5% bleach once and water four times. The reservoir is seated on a Big Bear Automation Microplate Orbital Shaker, which shakes the reservoir throughout all self-cleaning steps to achieve uniform diffusion.

Software.

A general-purpose driver method was created using MicroLab STAR VENUS ONE software and compiled to Hamilton Scripting Language (hsl) format. Instantiation of this method and management of its local network connection was handled in Python. The Pyhamilton Python22 package provided an overlying control layer. Interfaces to the CLARIOstar plate reader, pump array and orbital shaker were encapsulated in supporting Python packages. We used Git to develop and version control the packages and the specific Python methods used for each experiment; our software implementation can be found on github at https://github.com/dgretton/std-96-pace.

PRANCE experimental set-up.

Mutagenesis functionality plating test.

To avoid premature induction of the mutagenesis plasmid (which can mutagenize the mutagenesis plasmid itself and lead to loss of inducible mutagenesis) all bacteria containing mutagenesis plasmids are repressed with 20 mM glucose, and were not grown, to higher density than OD600 = 1.0. To confirm mutagenesis plasmid functionality, a bacterial culture sample or four single-colony transformants were picked and resuspended in DRM, and were serially diluted and plated on 2XYT media + 1.5% agar with appropriate antibiotics (at half of the usual concentrations) with either 25 mM arabinose or 20 mM glucose. Bacteria containing functional mutagenesis plasmid 6 (MP6) will exhibit smaller colonies on the arabinose plate relative to the glucose plate.

PRANCE host bacterial strain preparation.

To prepare host bacterial strains, the accessory plasmid of interest and mutagenesis plasmid (MP6)24 were transformed into S2060 cells as described. During MP6 transformation, cells were recovered with DRM to ensure MP6 repression and were streaked on 2XYT media + 1.5% agar with appropriate antibiotics (at half of the usual concentrations) and 20 mM glucose. Transformants were picked for the mutagenesis functionality plating test (above), and those same transformants were grown, at 37 °C with shaking at 230 r.p.m. to OD600 0.4. This culture was used to seed a PRANCE culture in a manner dependent on the specific PRANCE experiment:

To initiate a turbidostat, prepared host bacteria were used to seed DRM supplemented with 25 μg ml−1 carbenicillin and 20 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol in a turbidostat (implemented by a standard turbidity probe and glassware vessel). The bacteria were grown with stirring at 37 °C to OD600 = 0.8.

To initiate chemostats, prepared host bacteria were used to seed 150 ml of DRM supplemented with appropriate antibiotics (at half of the usual concentrations) in three separate chemostat vessels. The chemostat cultures were kept at roughly 100–150 ml and grown with stirring at 37 °C. The flow-through and volume of the turbidostats were manually adjusted as needed to maintain the target OD600 = 0.8 in all chemostats.

To prepare chilled bacterial culture for use in PRANCE, an overnight culture of prepared host bacteria was diluted 1:1,000 into 2 × 600 ml of DRM in two separate 2 l baffled flasks with appropriate antibiotics (at half of the usual concentrations). The bacteria were grown, at 37 °C with shaking at 230 r.p.m. to OD600 of roughly 0.3–0.4. The two 600-ml cultures were combined and stored at 4 °C for up to 4 days before being situated in a 4 °C refrigerator adjacent to the robot.

MP6 functionality is also confirmed at the end of the experiment with the arabinose/glucose plating test (above).

Anticipated mutagenesis rates.

Use of the MP6 mutagenesis plasmid increases the mutation rate to two mutations per kilobasepair24. For example, when evolving tRNAs (roughly 75 basepairs), during a single round of phage genome replication in a PRANCE experiment, a tRNA will experience 0.15 mutations per replication in the tRNA itself. This generates a double-mutant rate of 0.023 double mutants per replication, providing an opportunity to traverse single-mutant fitness valleys. To approximate, the average phage replicates roughly 24 times per day at steady state5 and consequently generates roughly 0.55 double mutants per phage per day within the tRNA. PRANCE experiments typically harbor around 108 infected cells per ml. Thus, for 0.5-ml populations, we expect each experiment to visit roughly 2.5 × 107 double mutants per day, which should reliably cover the 24,975 unique possible two mutants:

General PRANCE implementation.

Host bacteria were pumped from their source (turbidostat, chemostat or refrigerated chilled culture) into the on-deck bacterial reservoir. Arabinose was added to the reservoir to a final concentration of 10 mM to induce mutagenesis. Then, 250 μl of bacteria were robotically transferred to each replicate (500 μl per replicate) in deep 96-well plates situated on the deck of the liquid-handling robot, which was kept at 37 °C. To avoid edge effects, replicates are placed in every other column (Extended Data Fig. 7). This liquid exchange occurs every 30 min continuously throughout the duration of the experiment, generating a flow-through rate of 1 vol h−1 in each replicate. After allowing mutagenesis induction for 1 h, each replicate was inoculated with selection phage to a starting titer between 105 and 108pfu ml−1, with appropriate replicates set aside as no-phage controls. Sampling and plate reading of replicate waste liquid was automatically carried out every 1–4 h as described. After completion of PRANCE, the phage supernatant from select replicates was filtered and plaqued; clonal plaques were expanded overnight, filtered and Sanger sequenced.

Semicontinuous flow using pipetting.

To perform liquid exchange, every 30 min, automated pipetting was used to exchange liquid in on-deck replicates. The procedure consisted of tip pickup, aspiration of fresh bacterial culture, dispense of new culture into replicate vessels, mixing of liquid, aspiration of waste, dispense of waste into the waste reservoir and tip disposal.

Automated plate reading.

At specified times, 175 μl of the waste samples are deposited into plate reader plates. To read the plates, the plate gripper transports the plate to the integrated plate reader for absorbance at an OD of 600 nm and fluorescence or luminescence measurements as required.

Choosing number of replicates.

Consult Extended Data Fig. 1 to select a configuration (number of populations, bottlenecking fraction and hands-off time) that meets your experimental requirements. There are two primary limiting factors: the amount of time the robot requires to perform each necessary step within a given time frame, and the number of consumable reagents (tips, plates and so on) that can be physically staged on the deck of the robot. For every individual PRANCE run, we select and tune the method configurations depending on the requirements of each individual experiment (Supplementary Table 1). All of our experiments are run at an effective flow-through rate of 1 vol h−1, with a bottlenecking fraction of 0.5. A configuration we frequently preferred consisted of 48 evolving populations, requiring experimenter intervention once every 13 h. Alternatively, when operating at maximum capacity (1 vol h−1, 96 populations) PRANCE requires intervention once every 7 h. The tradeoff between populations and hands-off time will depend on the capacity of your robot deck.

Automated tip sterilization and reuse.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, supplies of consumable labware involved in viral diagnostic tests became constrained39, including supplies of pipette tips for Hamilton robots. Due to the number of liquid-handling steps involved in a typical evolution, it is preferable to reuse the same tips over the course of an evolution rather than replace each tip after every liquid-handling step. This is done to avoid adding to the extensive backlog of constrained supplies, to avoid spending time manually reloading new tips onto the deck and to increase the available deck space for increasingly advanced evolution methods. To implement tip reuse, tips must be cleaned and sterilized with bleach after every liquid-handling step to avoid cross-contamination between replicates. Water rinses are performed after sterilization to prevent bleach carryover into replicates. The equipment required to implement this protocol are the Hamilton washer module for pumping fresh water and 10% bleach into basins, and four 500-ml reservoirs for holding 10% bleach (first basin) or tap water (remaining three). Tip washing and sterilization are performed at two distinct points during each robotic cycle. The first point is after bacteria is moved from holding wells to replicates containing M13 phage using the 96-channel head. The 96-channel head then dispenses residual liquid from the previous step into the bleach basin on the Hamilton washer module, then submerges the tips in a bleach reservoir on the robot deck. The 96-channel head next aspirates and dispenses freshly pumped water from the water basin on the Hamilton washer module as a rinsing step. Finally, the 96-channel head performs consecutive rinses on each water reservoir on-deck to remove any residual bleach. The second point where tip washing and sterilization occurs is after moving culture from viral replicates to reader plates with the eight-channel head. Immediately after each dispense to a reader plate, the eight-channel head performs the same series of actions previously described for the 96-channel head. To allow for adequate drying time after each wash, the robot script rotates through five 96-tip racks, ensuring washed tips will not be reused for at least one whole robotic cycle. Luminescence assays were performed on the above protocol to validate the absence of cross-contamination and bleach carryover between wells. Before inoculation, fresh tips were used and sterilized. To assess the effectiveness of tip sterilization, tips were submerged directly in phage-containing T7 RNAP, sterilized and then used to maintain psp-pIII bacteria cultures using a high-throughput turbidostat method as previously described22. They were compared to no-phage contamination negative controls, and bacteria inoculated with the same phage as positive controls, in 24 replicates. This protocol may be used to implement pipette tip sterilization and reuse for general experimental protocols run on Hamilton robots, including COVID-19 quantitative PCR sample preparation.

Next-generation sequencing.

qtRNA were amplified off of phage populations (four qtRNA evolution experiments, two replicates, ten time points, four evolution conditions) with primers barcoding for qtRNA and time points. Barcoded samples were pooled and sequenced as Illumina paired end reads.

Data analysis.

To calculate evolution times for each data point were calculated from the inflection point of the data fit to a weighted n-parameters logistic regression with the nplr package in R. Distribution of total evolution times calculated by fitting univariate distributions to data by maximum likelihood estimation, and the goodness of fit Kolmogorov–Smirnov, Cramer–von Mises statistics were calculated with the fitdistrplus package in R47.

Feedback controller calculation.

For each individual replicate, luminescence is first normalized to absorbance. Each replicate reading is then smoothed over an interval of n = 3 and stringency adjustment is triggered after three sequential events in which the reading is 3σ over background. Background is quantified as the average of no-phage controls (luminescence/absorbance). The second stringency adjustment (moderate → stringent) is triggered similarly, following a 12 h delay to allow for luminescence equilibration.

Phylogenetic trees.

Phylogenetic lineages were identified with R packages ade448, ape49, adegenet50 and phyloseq51 and visualized with ggtree52.

Muller plots.

Parent lineages were identified from phylogenetic trees and then used to generate muller plots with the R package ggmuller53. For visualization purposes, abundance was adjusted for population size by scaling the fraction by the total amount of luminescence at each given time point. Actual sequencing abundance fraction percentages are presented of each replicate per population are shown in Fig. 5f.

Extended Data

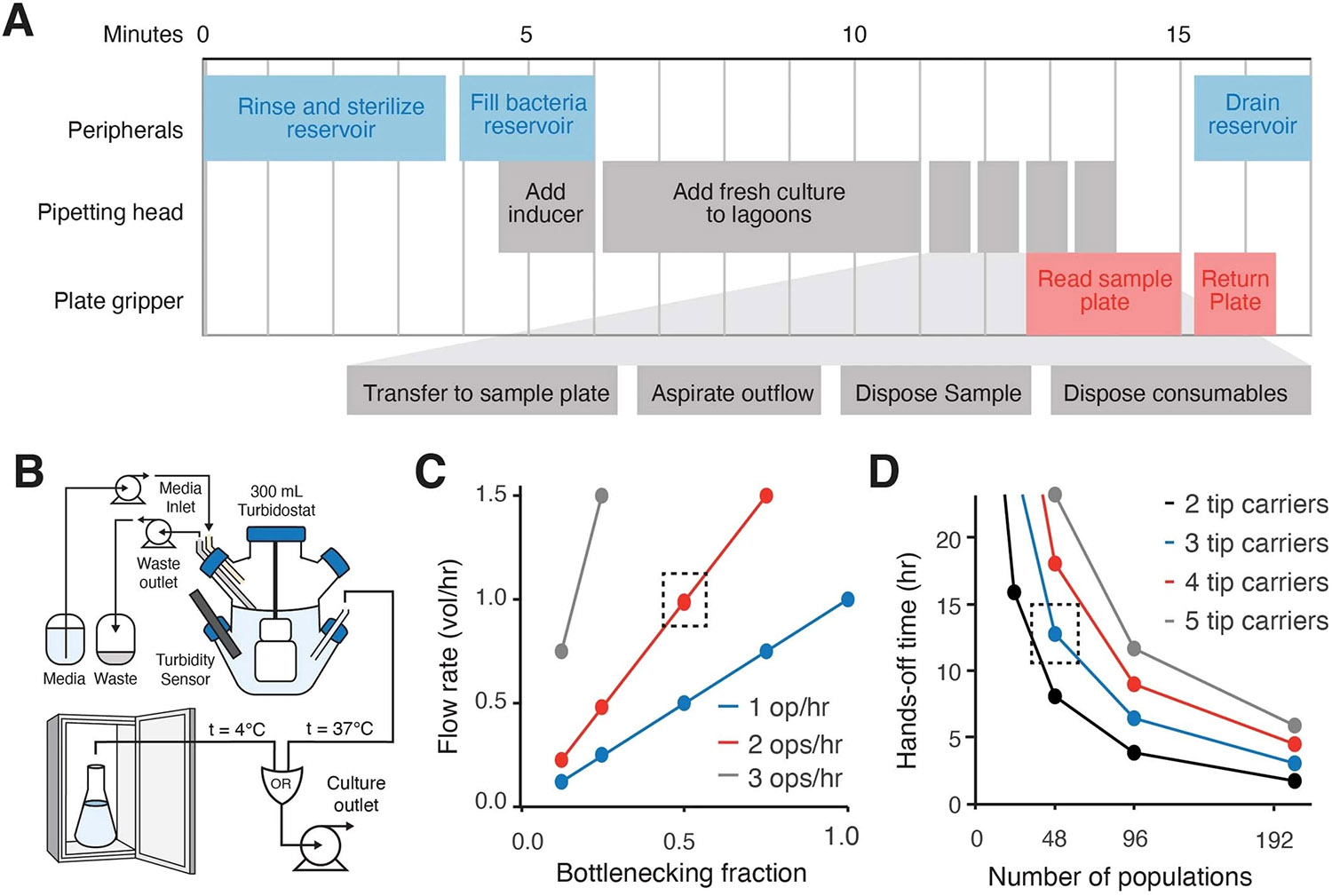

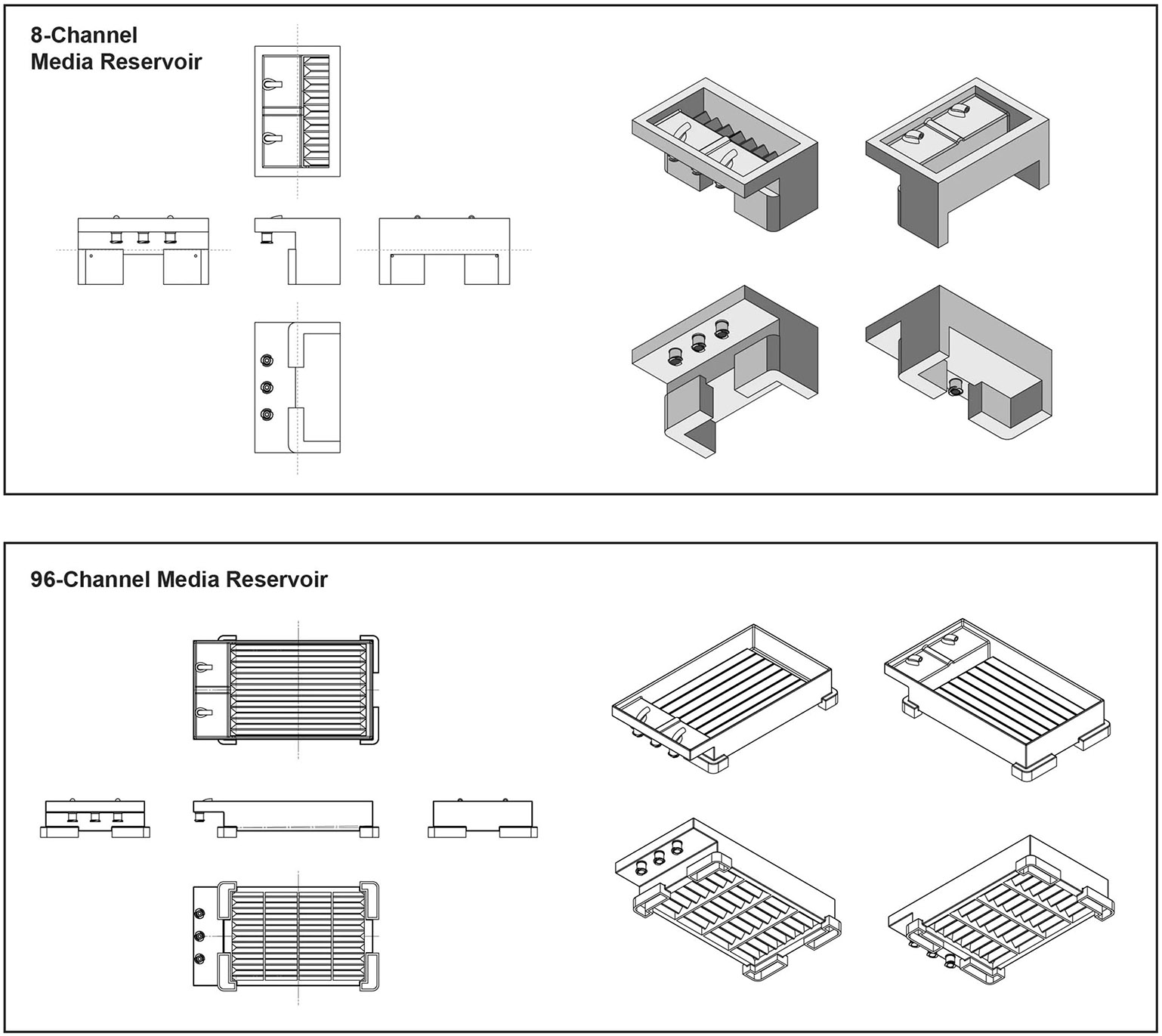

Extended Data Fig. 1 ∣. PRANCE optimization.

(a) Robotic manipulations operate in a loop, which repeats every 30 minutes. (b) Culture source fluidics (media, turbidostat/static culture, waste) are peripherally separated from the robot. The maximum flow-through rate is determined by the frequency with which the robot exchanges liquid (operations per hour), as well as the fraction of the standing volume of the population that is exchanged during each operation (the bottlenecking fraction). There is a trade-off between the maximum flow rate and the extent of bottlenecking. (c) The number of populations that can be serviced assuming 2 robot operations per hour (ops/hr) impacts the experimenter-free/hands-off operation time of the robot. (d) Larger robot decks can fit more tip carriers, more tips, and therefore require less frequent servicing.

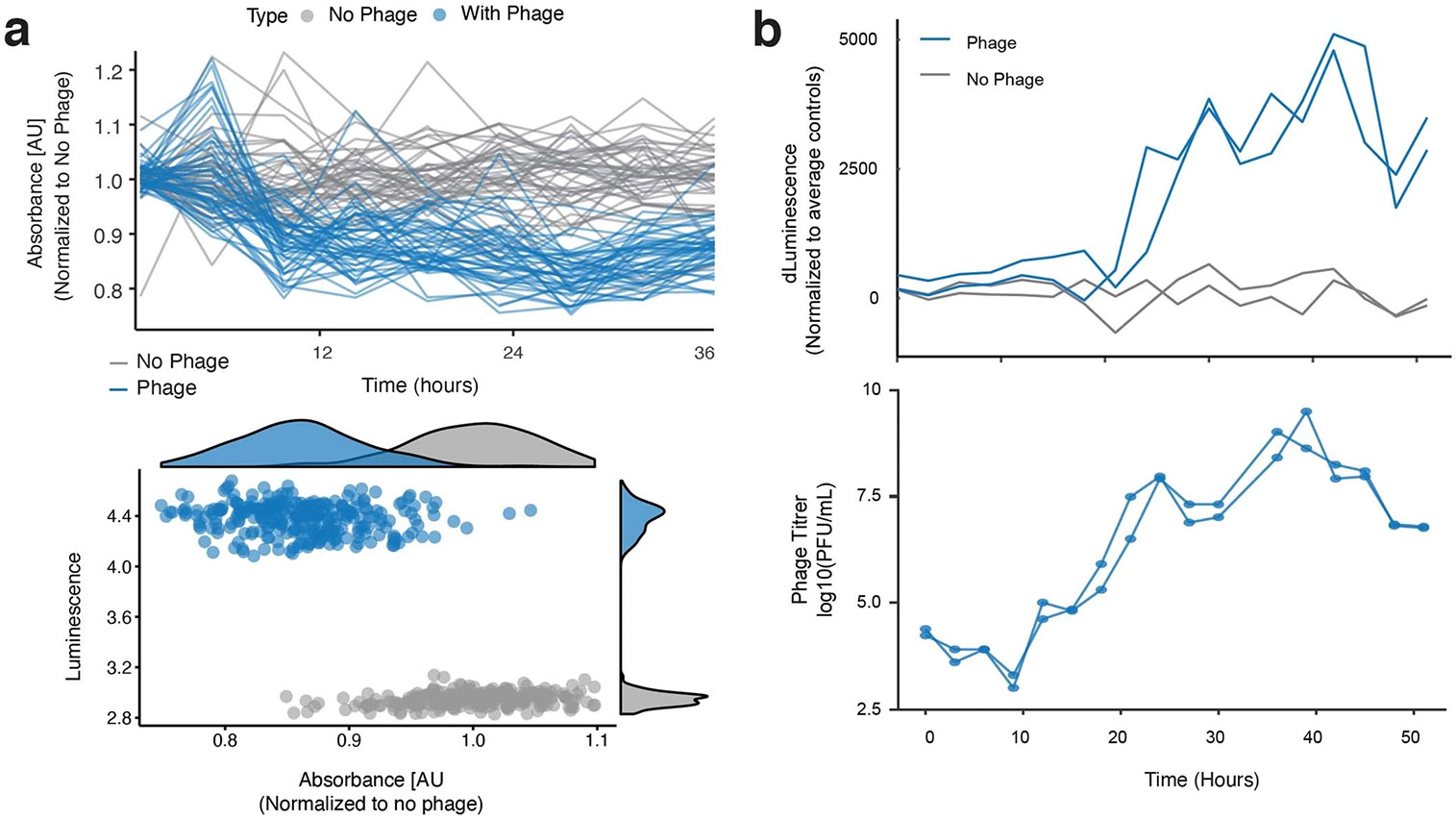

Extended Data Fig. 2 ∣. Relationship between real-time monitoring data and phage titer.

(a) Correlation between absorbance depression and luminescence for each evolving replicate. Kernel density estimates of the absorbance and luminescence data for the population are plotted on x and y axis, respectively. Luminescence data from Fig. 2b. (b) Comparison of real-time luminescence tracking (top) and corresponding phage titer as measured by traditional plaque assays (bottom). See Supplementary Table 1 for evolution construct details.

Extended Data Fig. 3 ∣. Reservoir diagrams.

Schematics of the 8-channel and 96-channel media reservoirs. These were printed on a Form 3 resin 3D printer. See the Supplementary Table 4 for .stl files for each.

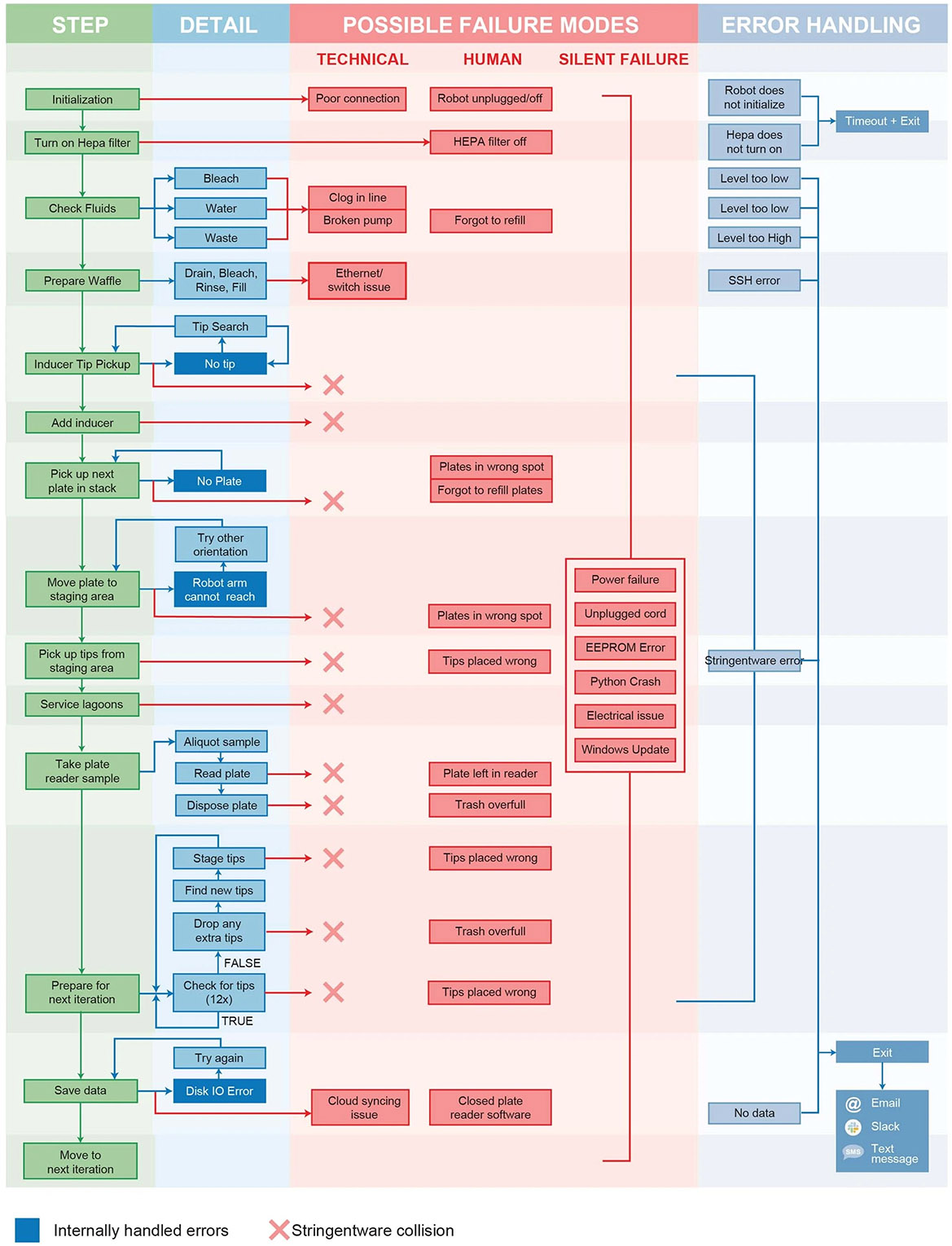

Extended Data Fig. 4 ∣. Failure mode analysis.

Analysis of failure modes used to improve reliability and error handling.

Extended Data Fig. 5 ∣. Stochasticity of T7 RNAP evolution.

Validating T7 mutagenesis with cool PRANCE. MP-containing bacteria were provided with either 1) induction prior to cooling to 4 C, 2) given no inducer, or 3) induced on the robotic deck at 37 C and their luminescence was tracked for 30 hours to validate that mutagenesis behaved similarly to induction of cultures directly from a turbidostat (see Fig. 1d). (b) Real-time absorbance depression monitoring of 90 simultaneous directed evolution experiments with 6 no-phage controls, fit with a binomial regression of the total data. (c) Logistic regression of each luminescence trace during T7 RNAP evolution to bind the T3 promoter, used to calculate the average evolution times (Supplemental Methods). (d) Goodness-of-fit estimates of a logistic distribution of the total T7 evolution time data.

Extended Data Fig. 6 ∣. TAGA-qtRNA and AGGG-qtRNA PRANCE.

(a) Constructs for evolving TAGA-decoding qtRNAs. (b) Representative results for evolving TAGA-decoding qtRNAs. (c) Evolved qtRNAs exhibit increased ability to decode a TAGA quadruplet codon. Units are the percent luminescence when translating luxAB-357-TAGA in the presence of the qtRNA relative to expression of all-triplet-luxAB. (d) evolved genotypes E) Real-time absorbance and luminescence monitoring of qtRNA-encoding phage where either randomized or directed anticodons were used to evolve AGGG containing codons.

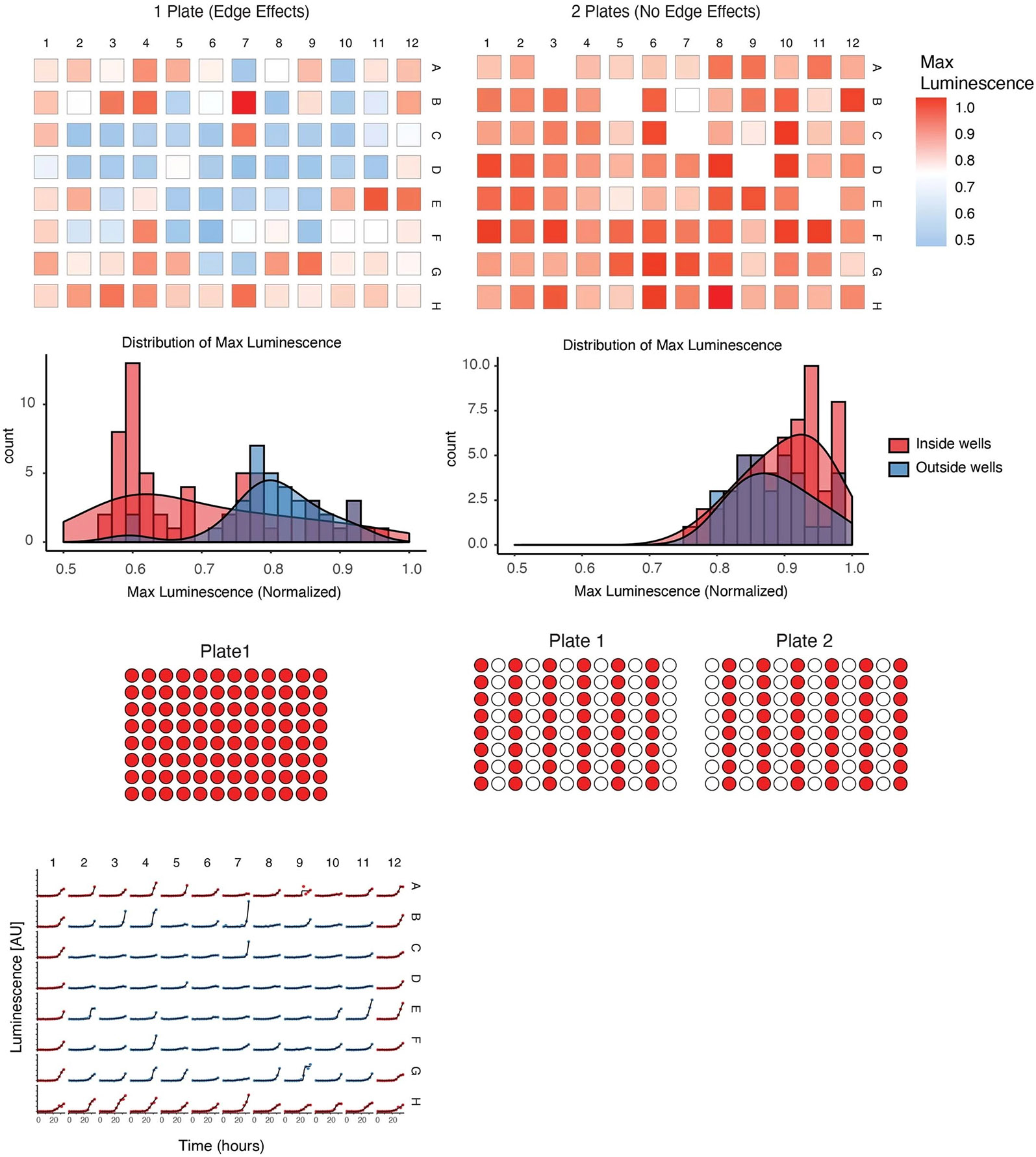

Extended Data Fig. 7 ∣. Edge effects.

Comparison between 96 replicates implemented in a densely packed 96-well plate (left) and 96 replicates split over two plates to reduce edge effects (right). Data plots the minimum time to phage detection via luminescence monitoring (below). Both plates above are normalized to their internal max value.

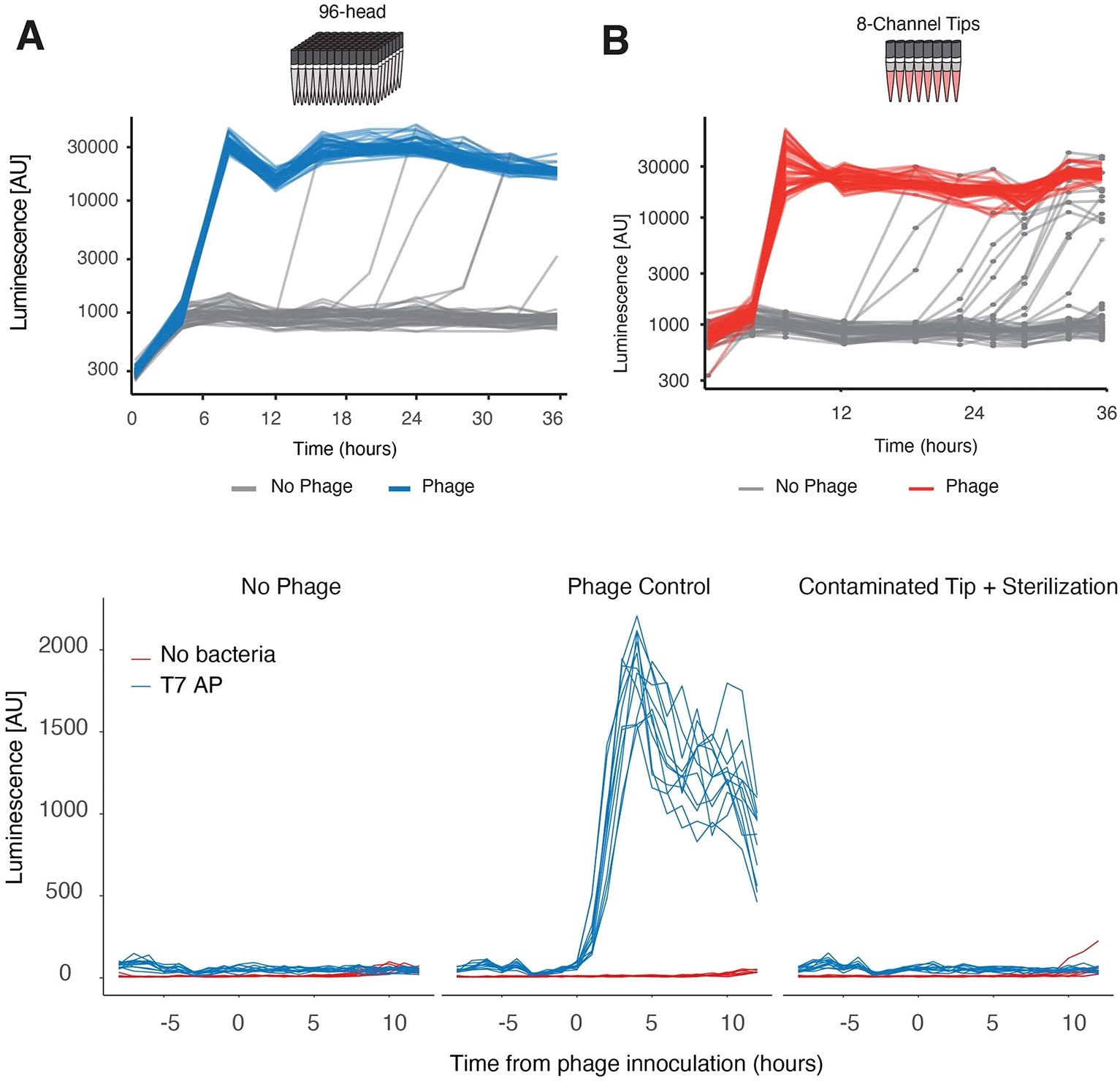

Extended Data Fig. 8 ∣. Tip contamination, sterilization and reuse.

To assess the maximum amount of possible cross-contamination, T7 RNAP-containing phage were inoculated into cultures containing pT7-psp-LuxAB bacteria in a grid-like pattern with 48 phage-containing wells and 48 no-phage-containing wells. PRANCE steps were performed with either (a) the 96-head channel or (b) the 8-channel pipettor. Use of the 96-well head gave less cross-contamination events, which we attributed to lower fly-over events. (c) To assess the impact of tip-sterilization and reuse in the optimized robotic method and configuration (Supplemental Video 1), robotic tips were submerged in either water or T7 RNAP-containing phage and then sterilized prior to being used to maintain high-throughput bacterial cultures containing pT7-psp-LuxAB22. Sterilized tips were also used to propagate bacteria inoculated with T7 RNAP phage as a positive control to ensure that bleach carryover did not affect phage propagation. No cross contamination was observed in the serialized tip condition over 12 hours, indicating that tips could be reused for a minimum of 12 hours without being replaced.

Extended Data Fig. 9 ∣. Kinetic Luminescence Activity Assays of −3, −5, and TP6 Promoter Variants.

To quantify the relative activities of each variant (independent of possible phage backbone mutations), phage from each replicate at time point t = 10 days were isolated and each T7 RNAP variant was cloned into an IPTG-inducible reporter construct. Subcloned variants were transformed into S2060 cells containing LuxAB driven by either the (a) −3 variant, (b) −5 variant, or (c) TP6 promoter and grown overnight to an OD > 1. Bacteria were then diluted 1:100 and grown to an OD of exactly 1.2 in DRM using a high-throughput robotic turbidostat method as described previously22. Once the bacteria reached an OD of 1.2 (approximately 2 hours), cells were induced with either 1 mM IPTG or [−] IPTG controls (n = 3 for each condition). Bacteria were autonomously maintained at an OD of 1.2 for the duration of the experiment and luminescence readings were taken once every 45 minutes for 10 hours. Fold change in luminescence (as shown in Fig. 6E), was calculated by averaging the luminescence in each turbidostat once the luminescence reached equilibrium (t > 8 hours) and then normalized to the average luminescence of the [−] IPTG controls within the same time window. WT T7 RNAP was used as a control for each respective promoter reporter construct (n = 6 for each WT control).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge W. Consigli, W. Fu, A. Cuevas and others at Hamilton Robotics for their guidance and assistance. We thank K. Prather’s laboratory for equipment use and assistance. We thank E. Alley, S. Von Stetina and B. Thuronyi for their thoughtful comments on the paper. This work was supported by the MIT Media Laboratory, an Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellowship (to KME), gifts from the Open Philanthropy Project and the Reid Hoffman Foundation (to K.M.E.), and the National Institute of Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grant no. R00 DK102669-01 to KME). E.A.D. was supported by the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant no. F31 AI145181-01). E.J.C. was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA fellowship from the National Cancer Institute (grant no. F32 CA247274-01).

Footnotes

Competing interests

E.A.D. and K.M.E. have filed US Patent 16405380 on this work.

Extended data are available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-021-01348-4.

Supplementary information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-021-01348-4.

Reporting Summary. Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-021-01348-4.

Data availability

All data are publicly available at https://doi.org/10.17632/h9z94f9y6p.1 (https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/h9z94f9y6p/1). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All code will be made available via github, see https://github.com/dgretton/std-96-pace and https://github.com/dgretton/roboplaque.

References

- 1.Good BH, McDonald MJ, Barrick JE, Lenski RE & Desai MM The dynamics of molecular evolution over 60,000 generations. Nature 551, 45–50 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrick JE et al. Genome evolution and adaptation in a long-term experiment with Escherichia coli. Nature 461, 1243–1247 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao H, Giver L, Shao Z, Affholter JA & Arnold FH Molecular evolution by staggered extension process (StEP) in vitro recombination. Nat. Biotechnol 16, 258–261 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romero PA & Arnold FH Exploring protein fitness landscapes by directed evolution. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 10, 866–876 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esvelt KM, Carlson JC & Liu DR A system for the continuous directed evolution of biomolecules. Nature 472, 499–503 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berman CM et al. An adaptable platform for directed evolution in human cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc 140, 18093–18103 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.English JG et al. VEGAS as a platform for facile directed evolution in mammalian cells. Cell 10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.051 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crook N. et al. In vivo continuous evolution of genes and pathways in yeast. Nat. Commun 7, 13051 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ravikumar A, Arzumanyan GA, Obadi MKA, Javanpour AA & Liu CC Scalable, continuous evolution of genes at mutation rates above genomic error thresholds. Cell 175, 1946–1957.e13 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leconte AM et al. A population-based experimental model for protein evolution: effects of mutation rate and selection stringency on evolutionary outcomes. Biochemistry 52, 1490–1499 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickinson BC, Leconte AM, Allen B, Esvelt KM & Liu DR Experimental interrogation of the path dependence and stochasticity of protein evolution using phage-assisted continuous evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 9007–9012 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu JH et al. Evolved Cas9 variants with broad PAM compatibility and high DNA specificity. Nature 10.1038/nature26155 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong BG, Mancuso CP, Kiriakov S, Bashor CJ & Khalil AS Precise, automated control of conditions for high-throughput growth of yeast and bacteria with eVOLVER. Nat. Biotechnol 36, 614–623 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horinouchi T, Minamoto T, Suzuki S, Shimizu H & Furusawa C Development of an automated culture system for laboratory evolution. J. Lab. Autom 19, 478–482 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhong Z. et al. Automated continuous evolution of proteins in vivo. ACS Synth. Biol 9, 1270–1276 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer MM et al. Library analysis of SCHEMA-guided protein recombination. Protein Sci. 12, 1686–1693 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crameri A, Raillard SA, Bermudez E & Stemmer WP DNA shuffling of a family of genes from diverse species accelerates directed evolution. Nature 391, 288–291 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karanicolas J. et al. A de novo protein binding pair by computational design and directed evolution. Mol. Cell 42, 250–260 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amini ZN & Müller UF Low selection pressure aids the evolution of cooperative ribozyme mutations in cells. J. Biol. Chem 288, 33096–33106 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zinkus-Boltz J, DeValk C & Dickinson BC A phage-assisted continuous selection approach for deep mutational scanning of protein–protein interactions. ACS Chem. Biol 14, 2757–2767 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blount ZD, Lenski RE & Losos JB Contingency and determinism in evolution: replaying life’s tape. Science 362, eaam5979 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chory EJ, Gretton DW, DeBenedictis EA & Esvelt KM Enabling high-throughput biology with flexible open-source automation. Mol. Syst. Biol 17, e9942 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balagaddé FK, You L, Hansen CL, Arnold FH & Quake SR Long-term monitoring of bacteria undergoing programmed population control in a microchemostat. Science 309, 137–140 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Badran AH & Liu DR Development of potent in vivo mutagenesis plasmids with broad mutational spectra. Nat. Commun 6, 8425 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polycarpo C. et al. An aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase that specifically activates pyrrolysine. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 12450–12454 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bryson DI et al. Continuous directed evolution of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Nat. Chem. Biol 10.1038/nchembio.2474 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Umehara T. et al. N-acetyl lysyl-tRNA synthetases evolved by a CcdB-based selection possess N-acetyl lysine specificity in vitro and in vivo. FEBS Lett. 586, 729–733 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chin JW et al. Addition of p-azido-l-phenylalanine to the genetic code of Escherichia coli. J. Am. Chem. Soc 124, 9026–9027 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Srinivasan G, James CM & Krzycki JA Pyrrolysine encoded by UAG in Archaea: charging of a UAG-decoding specialized tRNA. Science 296, 1459–1462 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeBenedictis EA, Carver GD, Chung CZ, Söll D & Badran AH Multiplex suppression of four quadruplet codons via tRNA directed evolution. Nat. Commun 12, 5706 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magliery TJ, Anderson JC & Schultz PG Expanding the genetic code: selection of efficient suppressors of four-base codons and identification of ‘shifty’ four-base codons with a library approach in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol 307, 755–769 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson JC, Magliery TJ & Schultz PG Exploring the limits of codon and anticodon size. Chem. Biol 9, 237–244 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang K, Neumann H, Peak-Chew SY & Chin JW Evolved orthogonal ribosomes enhance the efficiency of synthetic genetic code expansion. Nat. Biotechnol 25, 770–777 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeBenedictis E, Söll D & Esvelt K Measuring the tolerance of the genetic code to altered codon size. Preprint at bioRXiv 10.1101/2021.04.26.441066 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nourmohammad A & Eksin C Optimal evolutionary control for artificial selection on molecular phenotypes. Phys. Rev. X 11, 011044 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simutis R & Lübbert A Bioreactor control improves bioprocess performance. Biotechnol. J 10, 1115–1130 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hartl RF, Mehlmann A & Novak A Cycles of fear: periodic bloodsucking rates for vampires. J. Optim. Theory Appl 75, 559–568 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baym M. et al. Spatiotemporal microbial evolution on antibiotic landscapes. Science 353, 1147–1151 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wadman M. United States rushes to fill void in viral sequencing. Science 371, 657–658 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao Y & Yang Y Profiling metabolic states with genetically encoded fluorescent biosensors for NADH. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 31, 86–92 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang L. et al. Ratiometric fluorescent pH-sensitive polymers for high-throughput monitoring of extracellular pH. RSC Adv. 6, 46134–46142 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhujun Z & Seitz WR A carbon dioxide sensor based on fluorescence. Anal. Chim. Acta 160, 305–309 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cho I, Jia Z-J & Arnold FH Site-selective enzymatic C–H amidation for synthesis of diverse lactams. Science 364, 575–578 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang R & Krzycki JA PylSn and the homologous N-terminal domain of pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase bind the tRNA that is essential for the genetic encoding of pyrrolysine. J. Biol. Chem 287, 32738–32746 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki T. et al. Crystal structures reveal an elusive functional domain of pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase. Nat. Chem. Biol 13, 1261–1266 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheetham GMT, Jeruzalmi D & Steitz TA Structural basis for initiation of transcription from an RNA polymerase–promoter complex. Nature 399, 80–83 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Delignette-Muller ML et al. fitdistrplus: an R package for fitting distributions. J. Stat. Softw 64, 1–34 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dray S. et al. The ade4 package: implementing the duality diagram for ecologists. J. Stat. Softw 22, 1–20 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paradis E & Schliep K ape 5.0: an environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics 35, 526–528 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jombart T. adegenet: a R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 24, 1403–1405 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McMurdie PJ & Holmes S phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 8, e61217 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu G. Using ggtree to visualize data on tree-like structures. Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma 69, e96 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Noble R. ggmuller: create muller plots of evolutionary dynamics (GitHub, 2019). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are publicly available at https://doi.org/10.17632/h9z94f9y6p.1 (https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/h9z94f9y6p/1). Source data are provided with this paper.

All code will be made available via github, see https://github.com/dgretton/std-96-pace and https://github.com/dgretton/roboplaque.