Abstract

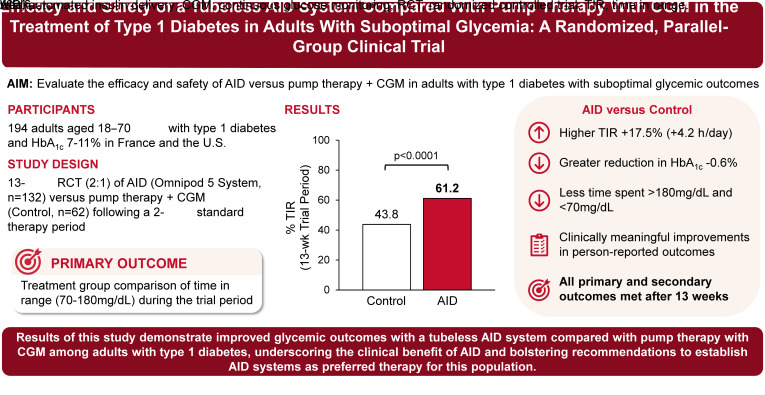

OBJECTIVE

To examine the efficacy and safety of the tubeless Omnipod 5 automated insulin delivery (AID) system compared with pump therapy with a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) in adults with type 1 diabetes with suboptimal glycemic outcomes.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

In this 13-week multicenter, parallel-group, randomized controlled trial performed in the U.S. and France, adults aged 18–70 years with type 1 diabetes and HbA1c 7–11% (53–97 mmol/mol) were randomly assigned (2:1) to intervention (tubeless AID) or control (pump therapy with CGM) following a 2-week standard therapy period. The primary outcome was a treatment group comparison of time in range (TIR) (70–180 mg/dL) during the trial period.

RESULTS

A total of 194 participants were randomized, with 132 assigned to the intervention and 62 to the control. TIR during the trial was 4.2h/day higher in the intervention compared with the control group (mean difference 17.5% [95% CI 14.0%, 21.1%]; P < 0.0001). The intervention group had a greater reduction in HbA1c from baseline compared with the control group (mean ± SD −1.24 ± 0.75% [−13.6 ± 8.2 mmol/mol] vs. −0.68 ± 0.93% [−7.4 ± 10.2 mmol/mol], respectively; P < 0.0001), accompanied by a significantly lower time <70 mg/dL (1.18 ± 0.86% vs. 1.75 ± 1.68%; P = 0.005) and >180 mg/dL (37.6 ± 11.4% vs. 54.5 ± 15.4%; P < 0.0001). All primary and secondary outcomes were met. No instances of diabetes-related ketoacidosis or severe hypoglycemia occurred in the intervention group.

CONCLUSIONS

Use of the tubeless AID system led to improved glycemic outcomes compared with pump therapy with CGM among adults with type 1 diabetes, underscoring the clinical benefit of AID and bolstering recommendations to establish AID systems as preferred therapy for this population.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Despite advances in diabetes technology, people with type 1 diabetes often struggle to maintain optimal glycemic outcomes, with observational studies reporting that most are not meeting the recommended clinical target of HbA1c <7% (53 mmol/mol) (1). Consequently, individuals with type 1 diabetes are at increased risk for long-term complications, a reduced quality of life, financial burden, and a decreased life span (2). With its prevalence increasing globally (3), there is an urgent need to develop and implement in clinical practice innovative insulin delivery modalities that can improve glycemic outcomes and ultimately reduce the complications associated with type 1 diabetes.

Automated insulin delivery (AID) systems represent the latest advancement in technology to optimize glucose management in people with type 1 diabetes (4). By combining insulin delivery pumps, continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), and closed-loop control algorithms, AID systems aim to more closely emulate the physiological functions of a healthy pancreas by automatically adjusting insulin delivery to minimize time spent in hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia (4). AID systems have demonstrated efficacy in improving glycemic outcomes for people with type 1 diabetes across a range of ages and demographic populations, while reducing the burden of decision-making and enhancing quality of life (5).

With such promising results across systems (5), consensus guidelines are being updated to proactively offer AID systems for people with type 1 diabetes, with an emphasis on providing access to these devices early in the disease (4). However, the uptake of this technology has been limited by a myriad of factors (health care professional, patient, cost, payer, and health care system–related and device-specific factors, including tubing, ease of use, discreetness, etc.), hindering the full potential of AID systems to improve health outcomes (6). Broad uptake requires that these systems be simple, minimally invasive, and easy to use and wear for people with type 1 diabetes.

The Omnipod 5 AID system (Insulet Corporation, Acton, MA) is a tubeless, wearable device cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and Conformité Européenne and marked for use in people with type 1 diabetes aged ≥2 years, and it has been recently cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in people with type 2 diabetes aged ≥18 years. The safety and effectiveness of the system has been demonstrated in people with type 1 diabetes in two single-arm pivotal and extension trials (7–10). However, it has yet to be demonstrated whether similar benefits would be present in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of individuals not meeting glycemic targets. The current study supports ongoing efforts to demonstrate the superiority of AID by examining the efficacy and safety of the tubeless AID system compared with pump therapy with CGM in an RCT of adults with type 1 diabetes not meeting the recommended glycemic targets in the U.S. and France.

Research Design and Methods

Trial Conduct and Oversight

This parallel-group RCT was conducted at 10 sites in the U.S. and 4 sites in France. Central and local institutional review boards and ethics committees approved the protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. A medical monitor provided trial oversight. The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05409131).

Trial Design and Participants

Eligible participants were aged 18–70 years and had type 1 diabetes for ≥1 year with HbA1c 7.0–11.0% (53–97 mmol/mol). The study included a requirement for at least 80% of participants to have a screening HbA1c ≥8.0% (64 mmol/mol). Participants were recruited only if they were on pump therapy for at least 3 months, with a requirement that at least 50% were using an Omnipod pump (Omnipod or Omnipod DASH Insulin Management System) at the time of enrollment (complete eligibility criteria provided in Supplementary Table 1). Participants using AID devices, including predictive low-glucose suspend, in the 3 months prior to screening were excluded. There were no inclusion or exclusion criteria based on CGM use.

After screening, participants were provided an unmasked study CGM (Dexcom G6; Dexcom Inc., San Diego, CA) to use with their current baseline pump therapy for 2 weeks to collect glucose sensor data on their usual regimen (standard therapy phase). Standard therapy data could be retrospectively collected for U.S. participants who used a Dexcom G6 CGM as part of their usual therapy and had sufficient data available (i.e., >80% CGM use during any consecutive 14 days in the past 30 days, with ≥2,016 CGM readings during the 14 days).

Following the standard therapy phase, participants were randomly assigned 2:1 to the intervention group or control group for 13 weeks. In the intervention group, participants were trained on and used the Omnipod 5 AID System. The system comprises an insulin-filled tubeless on-body pump (Pod) with an embedded AID algorithm and the Omnipod 5 application, which controls the Pod via Bluetooth wireless technology, on a provided locked-down Android phone (Controller), used by participants in this study, or a compatible personal smartphone. An interoperable CGM is required to use AID: the Dexcom G6 CGM was used in this study (11). Participants in the intervention group used the system in Automated Mode, in which insulin delivery is modulated every 5 min based on CGM glucose values to bring glucose toward the selected target, which is customizable from 110 to 150 mg/dL in increments of 10 mg/dL. There were no prespecified recommendations for target selection, with the initial glucose target left to the discretion of the investigator. In Manual Mode, the system functions as a traditional insulin pump (11). Additional details on the system have been previously published (11). In the control group, each participant continued using their usual insulin pump with a Dexcom G6 CGM provided by the trial investigators.

During the 13-week trial (trial period), there were six follow-up visits either in person or by telephone (Supplementary Table 2). At each visit, participants were asked about medications, adverse events, and device issues; vital signs were assessed; and the study team reviewed system data history and adjusted system settings as needed. HbA1c was assessed by a central laboratory (LabCorp) at screening and at the end of the study or upon early withdrawal. Questionnaires on quality of life and treatment satisfaction were conducted at baseline and at the end of the study or upon early withdrawal, including the Type 1 Diabetes Distress Scale (T1-DDS) (12), Hypoglycemia Confidence Scale (HCS) (13), and Diabetes Quality of Life-Brief (DQOL-Brief) (14). Reportable adverse events included severe hypoglycemia, diabetes-related ketoacidosis (DKA), hyperglycemia involving ketosis, adverse device events, any severe adverse events, and any adverse events that affected the participant’s ability to adhere to study procedures or for which a visit to the hospital emergency department was made.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the percentage of time in the glucose target range (time in range [TIR]) (70–180 mg/dL) during the 13-week trial period as measured with the study CGM. The secondary glycemic outcomes, which were tested in a hierarchical order to maintain the type I error rate at 5.0%, were percentage of time <54 mg/dL (noninferiority with a 1.0% margin), percentage of time >180 mg/dL, mean glucose, change from baseline in HbA1c, and percentage of time <70 mg/dL during the 13-week trial period (Supplementary Table 3).

Other secondary outcomes also included in the hierarchy were person-reported outcome measures, including change from baseline in the T1-DDS, HCS, and DQOL-Brief total scores, as well as the proportion of participants who experienced a clinically meaningful change for each measure (i.e., responders) at the end of the study. The prespecified minimum clinically important difference for the T1-DDS was an improvement in total score ≥0.19 as defined in the literature (15). For the DQOL-Brief, as no minimum clinically important difference was available in the literature, a distribution-based method was selected to prespecify the clinically meaningful difference as ≥0.5 × SD of change from baseline in the total score as observed in the study. For the HCS, the prespecified clinically meaningful result was to have a total score ≥3 at the end of the study, indicating relatively high confidence in managing hypoglycemia as reported in the literature (13).

Exploratory outcomes included the proportion of participants with HbA1c <7.0% (53 mmol/mol) and <8.0% (64 mmol/mol) at the end of the study, the proportion with ≥1% (10.9 mmol/mol) improvement or ≥10% relative improvement in HbA1c from baseline, and the change in BMI and total daily insulin use from baseline. Additional exploratory outcomes included the percentage of time >250 mg/dL, percentage of time in tight range (70–140 mg/dL), glycemia risk index (16), coefficient of variation, and the percentage of TIR, time <54 mg/dL, and time <70 mg/dL during the day and night during the 13-week trial period.

Statistical Analysis

A sample of 131 participants (87 intervention, 44 control) was required to provide 90% power to detect a difference of 10% in TIR, assuming an SD of 16.5% in each group with a 2:1 intervention:control randomization (7). Up to 200 participants were recruited to allow for pre- and postrandomization attrition (assumed to be 15% and 22.9%, respectively).

A modified intention-to-treat analysis was conducted that included all participants randomized, unless otherwise noted. Strict control of type I error was maintained at a 5.0% level with a hierarchical testing procedure. For exploratory outcomes, there was no formal hypothesis testing, with no adjustments for multiplicity.

The continuous outcomes were analyzed using repeated-measures linear mixed-effects models, unless otherwise noted. Residual values were examined to confirm an approximate normal distribution. If values were highly skewed, then robust regression using M-estimation was used instead. Logistic mixed-effects models were used to examine proportion-based outcomes. Two-sided Fisher's exact test was used to examine the percentage of participants meeting CGM-based clinical targets (17). All models and reported treatment group differences included adjustment for the baseline level of the dependent variable, age, sex, and duration of diagnosis as fixed effects, with country and site as random effects. Sensitivity analyses were conducted based on various subsets (per protocol, complete case) or using imputation techniques (multiple imputation, worst case). Subgroup analyses by country, sex, race and ethnicity, age, BMI, baseline glycemic measures, and prior CGM use were conducted. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 statistical software.

Results

Participants and Follow-up

A total of 234 individuals consented to participate: 196 were enrolled, 194 were randomized, and 192 completed the study (Supplementary Fig. 1). The 194 participants (60% female, mean ± SD age 36 ± 14 years) were randomly assigned to either the intervention group (n = 132) or the control group (n = 62) (Table 1). U.S. participants accounted for 61% of those randomized. Of the 194 participants randomized, 87% were Omnipod pump users, and 94% had previous or current CGM use. Baseline point-of-care HbA1c was mean ± SD (range) 8.5 ± 0.8% (7.0–10.5%) [69 ± 8.7 (53–91) mmol/mol] in the intervention group and 8.6 ± 0.9% (7.0–10.9%) [70 ± 9.8 (53–96) mmol/mol] in the control group. At screening, the point-of-care HbA1c measurement was ≥8.0% (64 mmol/mol) for 80% and 82% of participants in the intervention and control groups, respectively. Additional baseline characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants at baseline (modified intention-to-treat data set)

| Characteristic | All randomized(n = 194) | Intervention group(n = 132) | Control group(n = 62) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 36 ± 14 | 36 ± 14 | 36 ± 13 |

| Range | 18–69 | 18–69 | 18–66 |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 19.5 ± 11.1 | 19.2 ± 11.0 | 20.2 ± 11.4 |

| Range | 1.8–54.0 | 1.8–54.0 | 2.2–50.5 |

| Country, n (%) | |||

| U.S. | 118 (60.8) | 80 (60.6) | 38 (61.3) |

| France | 76 (39.2) | 52 (39.4) | 24 (38.7) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 26.2 ± 4.6 | 26.6 ± 4.8 | 25.4 ± 4.1 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 116 (59.8) | 78 (59.1) | 38 (61.3) |

| Race and ethnicity, n (%)† | |||

| White | 99 (83.9) | 70 (87.5) | 29 (76.3) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 9 (7.6) | 7 (8.8) | 2 (5.3) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 90 (76.3) | 63 (78.8) | 27 (71.1) |

| Black or African American | 7 (5.9) | 4 (5.0) | 3 (7.9) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 6 (5.1) | 3 (3.8) | 3 (7.9) |

| Asian | 3 (2.5) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (5.3) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) |

| Other race | 2 (1.7) | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Multiple races | 4 (3.4) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (5.3) |

| Not disclosed | 2 (1.7) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (2.6) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 (1.7) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (2.6) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| HbA1c at screening (% [mmol/mol]) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 8.5 ± 0.8 [69.0 ± 8.7] | 8.5 ± 0.8 [69.0 ± 8.7] | 8.6 ± 0.9 [70.0 ± 9.8] |

| Range | 7.0–10.9 [53.0–96.0] | 7.0–10.5 [53.0–91.0] | 7.0–10.9 [53.0–96.0] |

| HbA1c ≥8% (64 mmol/mol) at screening, n (%) | 157 (80.9) | 106 (80.3) | 51 (82.3) |

| Daily insulin dose (units/kg)‡ | |||

| Mean ± SD | 0.62 ± 0.19 | 0.63 ± 0.20 | 0.59 ± 0.17 |

| Range | 0.23–1.28 | 0.23–1.28 | 0.30–1.16 |

| Previous or current CGM use, n (%) | 183 (94.3) | 124 (93.9) | 59 (95.2) |

| Duration of insulin pump use (years) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 9.6 ± 7.2 | 9.5 ± 7.4 | 9.8 ± 6.8 |

| Range | 0.3–49.3 | 0.3–49.3 | 0.3–29.2 |

†Due to privacy laws, race and ethnicity were reported by participants in the U.S. only.

‡Baseline total daily insulin dose was determined from data collected during the standard therapy phase.

Efficacy Outcomes

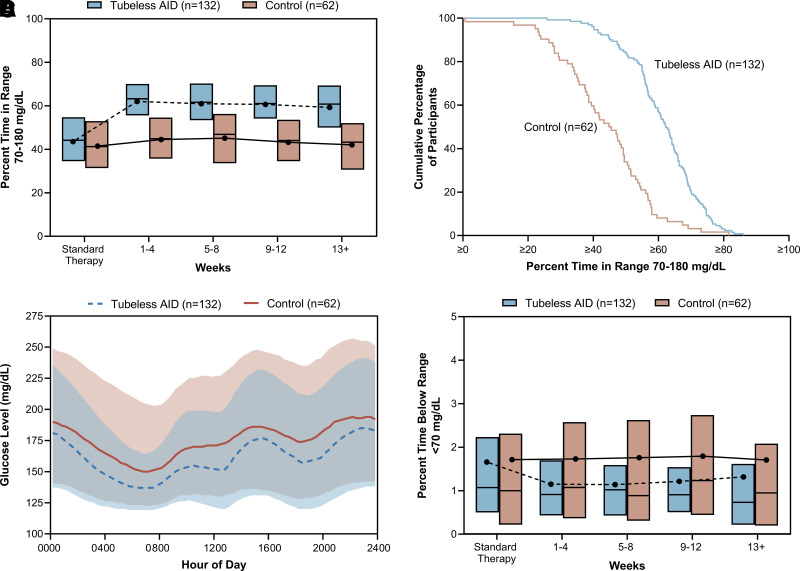

The primary outcome of percentage of TIR increased from 43.9 ± 14.0% with standard therapy to 61.2 ± 11.2% during the 13-week trial period in the intervention group and from 41.3 ± 14.6% to 43.8 ± 14.5% in the control group, with an adjusted mean difference (intervention – control) of 17.5% (95% CI 14.0%, 21.1%; P < 0.0001), corresponding to an additional 4.2 h/day (Table 2 and Fig. 1A and B). The difference remained significant in sensitivity analyses (per protocol, complete case, multiple imputation, and worst case; all P < 0.0001) (Supplementary Table 4). For the primary outcome of TIR, interactions by country, sex, race and ethnicity, age, BMI, and baseline TIR were all nonsignificant (P > 0.05) (Supplementary Table 5). Supplementary Table 6 presents the change in TIR stratified by subgroup.

Table 2.

Primary, secondary, and exploratory outcomes

| Baseline/standard therapy† | 13-Week trial period | Treatment effect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Intervention group(n = 132‡) | Control group(n = 62‡) | Intervention group(n = 132‡) | Control group(n = 62‡) | Adjusted difference, intervention − control (95% CI) | P |

| Primary outcome: TIR 70–180 mg/dL, %§ | 43.9 ± 14.0, 44.2 [34.7–54.8] (n = 129) | 41.3 ± 14.6, 41.2 [31.4–52.2] (n = 61) | 61.2 ± 11.2, 62.3 [55.2–68.8] (n = 131) | 43.8 ± 14.5, 45.1 [34.3–53.6] (n = 62) | 17.5 (14.0, 21.1) | <0.0001 |

| Secondary outcomes in prespecified hierarchical orderǁ | ||||||

| Time below glucose range <54 mg/dL (noninferiority), %¶ | 0.32 ± 0.53, 0.13 [0.00–0.39] (n = 129) | 0.42 ± 0.91, 0.10 [0.00–0.43] (n = 61) | 0.23 ± 0.23, 0.17 [0.07–0.28] (n = 131) | 0.37 ± 0.53, 0.16 [0.06–0.45] (n = 62) | −0.05 (−0.11, 0.00) | 0.0501 |

| Time above glucose range >180 mg/dL, %§ | 54.4 ± 14.7, 54.7 [42.7–64.4] (n = 129) | 57.1 ± 15.5, 56.3 [46.1–67.3] (n = 61) | 37.6 ± 11.4, 36.3 [29.8–43.9] (n = 131) | 54.5 ± 15.4, 54.0 [42.3–64.4] (n = 62) | −16.8 (−20.8, −12.8) | <0.0001 |

| Mean sensor glucose, mg/dL§ | 200 ± 30, 198 [177–220] (n = 129) | 204 ± 31, 198 [181–225] (n = 61) | 174 ± 20, 170 [161–183] (n = 131) | 200 ± 30, 195 [175–217] (n = 62) | −26 (−34, −18) | <0.0001 |

| Change in HbA1c, %# | 8.48 ± 0.79, 8.40 [7.95–8.95] (n = 132) | 8.57 ± 0.95, 8.50 [8.00–9.10] (n = 62) | 7.25 ± 0.76, 7.10 [6.80–7.70] (n = 119) | 7.84 ± 0.83, 7.90 [7.30–8.30] (n = 55) | −0.58 (−0.79, −0.37) | <0.0001 |

| Change in HbA1c, mmol/mol# | 69 ± 8.6, 68 [63–74] (n = 132) | 70 ± 10.4, 69 [64–76] (n = 62) | 56 ± 8.3, 54 [51–61] (n = 119) | 62 ± 9.1, 63 [56–67] (n = 55) | −6.3 (−8.6, −4.0) | <0.0001 |

| Time below glucose range <70 mg/dL, %¶ | 1.66 ± 1.79, 1.07 [0.52–2.22] (n = 129) | 1.66 ± 2.25, 0.96 [0.23–2.07] (n = 61) | 1.18 ± 0.86, 1.04 [0.57–1.59] (n = 131) | 1.75 ± 1.68, 1.14 [0.58–2.60] (n = 62) | −0.36 (−0.61, −0.11) | 0.0050 |

| Change in T1-DDS total score# | 2.01 ± 0.69, 1.93 [1.46–2.36] (n = 132) | 2.27 ± 0.71, 2.21 [1.71–2.71] (n = 62) | 1.72 ± 0.63, 1.54 [1.29–2.00] (n = 130) | 2.08 ± 0.68, 1.91 [1.63–2.45] (n = 60) | −0.18 (−0.32, −0.05) | 0.0094 |

| Change in HCS total score# | 3.24 ± 0.54, 3.24 [2.89–3.72] (n = 132) | 3.13 ± 0.52, 3.11 [2.88–3.56] (n = 62) | 3.40 ± 0.50, 3.56 [3.00–3.78] (n = 131) | 3.14 ± 0.58, 3.12 [2.78–3.67] (n = 60) | 0.20 (0.06, 0.34) | 0.0048 |

| Change in DQOL-Brief total score# | 3.75 ± 0.47, 3.73 [3.43–4.07] (n = 132) | 3.62 ± 0.49, 3.60 [3.33–3.93] (n = 62) | 4.11 ± 0.47, 4.17 [3.87–4.47] (n = 130) | 3.60 ± 0.47, 3.57 [3.24–4.00] (n = 60) | 0.43 (0.31, 0.55) | <0.0001 |

| T1-DDS–proportion of participants with a clinically meaningful change (≥0.19), % ** | — | — | 53.8 (45.3–62.4) | 45.0 (32.4–57.6) | 24.3 (6.0, 44.1) | 0.0145 |

| DQOL-Brief–proportion of participants with a clinically meaningful change (≥0.238), % ** | — | — | 59.2 (50.8–67.7) | 21.7 (11.2–32.1) | 52.7 (36.2, 67.9) | <0.0001 |

| HCS–proportion of participants with a clinically meaningful result (final score ≥3), %** | — | — | 81.7 (75.1–88.3) | 61.7 (49.4–74.0) | 18.9 (4.5, 34.7) | 0.0076 |

| Exploratory outcomes†† | ||||||

| Time above glucose range >250 mg/dL, %¶ | 25.4 ± 13.8, 24.1 [14.0–35.3] (n = 129) | 27.6 ± 14.6, 24.4 [15.7–37.0] (n = 61) | 13.5 ± 8.2, 11.6 [7.9–17.9] (n = 131) | 25.7 ± 14.3, 23.4 [14.4–33.4] (n = 62) | −10.8 (−12.8, −8.9) | <0.0001 |

| Time in tight glucose range 70–140 mg/dL, %§,‡‡ | 24.6 ± 9.8, 24.2 [17.7–31.3] (n = 129) | 23.2 ± 10.4, 22.2 [16.6, 30.6] (n = 61) | 36.3 ± 10.3, 36.3 [29.5–43.9] (n = 131) | 24.8 ± 10.5, 23.5 [16.4–33.1] (n = 62) | 11.5 (8.4, 14.5) | <0.0001 |

| Glycemia risk index§,‡‡ | 67 ± 20, 67 [52–83] (n = 129) | 71 ± 20, 75 [54–85] (n = 61) | 44 ± 15, 41 [33–52] (n = 131) | 68 ± 20, 67 [54–83] (n = 62) | −24 (−29, −19) | <0.0001 |

| Coefficient of variation of sensor glucose, %§ | 37.2 ± 5.3, 37.7 [33.5–40.6] (n = 129) | 36.8 ± 5.9, 36.8 [32.6–39.7] (n = 61) | 36.3 ± 4.1, 36.1 [33.5–39.1] (n = 131) | 37.3 ± 5.2, 37.7 [33.9–40.6] (n = 62) | −1.1 (−2.6, 0.4) | 0.1516 |

| TIR 70–180 mg/dL, daytime (0600–0000 h), %§ | 45.5 ± 14.8, 45.6 [35.5–57.4] (n = 129) | 42.1 ± 15.3, 41.6 [30.9–53.0] (n = 61) | 60.5 ± 11.9, 62.0 [53.8–67.8] (n = 131) | 44.4 ± 15.2, 44.8 [34.4–56.2] (n = 62) | 16.1 (12.3, 19.9) | <0.0001 |

| TIR 70–180 mg/dL, nighttime (0000–0600 h), %§ | 39.2 ± 16.0, 41.4 [27.0, 50.9] (n = 129) | 38.8 ± 17.4, 39.0 [26.2–49.1] (n = 61) | 63.3 ± 13.4, 65.1 [54.4–72.9] (n = 131) | 41.8 ± 14.7, 40.3 [31.2–53.7] (n = 62) | 21.7 (17.8, 25.5) | <0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2)¶ | 26.6 ± 4.8, 25.6 [23.2–29.3] (n = 132) | 25.4 ± 4.1, 24.5 [22.2–28.1] (n = 62) | 27.2 ± 5.2, 26.4 [23.5–30.2] (n = 126) | 25.7 ± 3.9, 24.7 [22.8–27.7] (n = 56) | 0.25 (−0.03, 0.52) | 0.0782 |

| Total daily insulin use (units/kg)# | 0.63 ± 0.20, 0.61 [0.50–0.74] (n = 130) | 0.59 ± 0.17, 0.54 [0.46–0.65] (n = 58) | 0.58 ± 0.19, 0.56 [0.46–0.68] (n = 132) | 0.57 ± 0.16, 0.56 [0.46–0.65] (n = 57) | −0.03 (−0.06, 0.00) | 0.0789 |

Data are mean ± SD and median [interquartile range] unless otherwise indicated. To convert the values for glucose to mmol/L, multiply by 0.05551. Analyses conducted on a modified intention-to-treat data set.

†Baseline and follow-up (end-of-trial) data were used for change in HbA1c, T1-DDS score, HCS score, DQOL-Brief score, BMI, and total daily insulin. The remaining outcomes compared the standard therapy phase with the trial period.

‡Three participants were randomized to the intervention and one participant randomized to control prior to complete collection of standard therapy CGM data.

§P value determined using repeated-measures linear mixed-effects model with treatment group, visit, treatment group-by-visit interaction, age, sex, and duration of diagnosis as fixed effects and country and site as random effects.

ǁA hierarchical approach was used to control the type I error. Hypothesis testing for secondary outcomes was performed sequentially in the order listed in the table. When a P ≥0.05 was observed, the outcomes below that finding on the list were not formally tested.

¶P value determined using robust regression model using M-estimation with Huber weight function with treatment group, age, sex, baseline value of the outcome, and duration of diagnosis as fixed effects. Missing data were handled using multiple imputation.

#P value determined using a linear mixed-effects model with treatment group, age, sex, duration of diagnosis, and baseline value of the outcome as fixed effects and country and site as random effects.

**P value determined using a logistic mixed-effects model with treatment group, age, sex, duration of diagnosis, and continuous baseline value of the outcome as fixed effects and country and site as random effects.

††There was no formal hypothesis testing for exploratory outcomes.

‡‡Post hoc analysis.

Figure 1.

Glycemic outcomes during standard therapy and over the 13-week trial period for each treatment group. A: Box plot of the percentage of TIR (70–180 mg/dL) during standard therapy and over the 13-week trial period for each treatment group. B: Cumulative distribution plot of the cumulative percentage of participants compared with the percentage of TIR over the 13-week trial period for each treatment group. C: Envelope plot of the sensor glucose level over the 13-week trial period according to time of day. Lines denote the median values of the participants’ glucose levels, and shaded regions indicate the interquartile range. D: Box plot of the percentage of time below range (<70 mg/dL) during standard therapy and over the 13-week trial period for each treatment group. To convert values for glucose to mmol/L, multiply by 0.05551.

All secondary outcomes evaluated in the hierarchical testing procedure revealed statistically significant between-group differences (or noninferiority) according to the analysis plan, favoring the intervention (Table 2). The mean difference between treatment groups during the 13-week trial period in percentage of time <54 mg/dL was −0.05% (95% CI −0.11%, 0.00%; P > 0.05). Although there was no significant difference between the two groups, the noninferiority limit of 1.0% was met, as the upper limit of the 95% CI of the adjusted difference was <1.0%. The mean difference between treatment groups in the percentage of time >180 mg/dL was −16.8% (95% CI −20.8%, −12.8%; P < 0.0001), corresponding to 4.0 fewer hours per day. The mean difference between treatment groups in mean glucose was −26 mg/dL (95% CI −34, −18 mg/dL; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1C). At the end of the study, HbA1c was 7.25 ± 0.76% (56 ± 8.3 mmol/mol) in the intervention group and 7.84 ± 0.83% (62 ± 9.1 mmol/mol) in the control group. The mean difference between treatment groups in change in HbA1c at 13 weeks was −0.58% (6.3 mmol/mol) (95% CI −0.79%, −0.37% [4.0, 8.6 mmol/mol]; P < 0.0001) (Supplementary Fig. 2). The mean difference between treatment groups in percentage of time <70 mg/dL was −0.36% (95% CI −0.61%, −0.11%; P = 0.005), corresponding to 5.2 fewer minutes per day (Fig. 1D). Supplementary Table 7 presents the change in percentage of time <70 mg/dL stratified by subgroup.

The mean differences between treatment groups in change in T1-DDS, HCS, and DQOL-Brief total scores were −0.18 (95% CI −0.32, −0.05; P = 0.009), 0.20 (95% CI 0.06, 0.34; P = 0.005), and 0.43 (95% CI 0.31, 0.55; P < 0.0001), respectively. The proportion of responders (participants who experienced the prespecified clinically meaningful result) was significantly greater in the intervention group than the control group at 13 weeks for each of the three person-reported measures (T1-DDS: mean difference of 24.3% [95% CI 6.0%, 44.1%; P = 0.02]; DQOL-Brief: mean difference of 52.7% [95% CI 36.2%, 67.9%; P < 0.0001]; HCS: mean difference of 18.9% [95% CI 4.5%, 34.7%; P = 0.008]). Supplementary Figs. 3–5 show the cumulative distribution function of the percentage of participants experiencing a given change in T1-DDS or DQOL-Brief score or final HCS score at 13 weeks, demonstrating a separation between the intervention and control groups across a wide range of potential responder definitions.

Exploratory Outcomes

Exploratory outcomes based on the HbA1c level were significant in favor of the intervention (Supplementary Table 8). The proportion of participants in the intervention and control groups with HbA1c <7.0% (53 mmol/mol) were 39.5% and 9.1% and with HbA1c <8.0% (64 mmol/mol) and were 85.7% and 52.7%, respectively (all P ≤ 0.0002). An improvement of at least 1.0% (10.9 mmol/mol) in HbA1c from baseline was seen in 70.6% of the intervention group and 30.9% of the control group (P < 0.0001). At least a 10% relative improvement in HbA1c from baseline was seen in 77.3% and 34.5% of the intervention and control groups, respectively (P < 0.0001). Supplementary Table 9 shows the change in HbA1c stratified by subgroup.

Exploratory outcomes assessing further CGM-based measures (Table 2) showed that the intervention group had significantly less percentage of time >250 mg/dL than the control group, with a mean difference between treatment groups of −10.8% (95% CI −12.8%, −8.9%; P < 0.0001), corresponding to 2.6 fewer hours per day. The intervention group had a significantly greater percentage of time in tight range than the control group, with a mean difference between treatment groups of 11.5% (95% CI 8.4%, 14.5%; P < 0.0001), corresponding to an additional 2.8 h/day. The mean difference between treatment groups in glycemia risk index was −24 (95% CI −29, −19; P < 0.0001) (16). The coefficient of variation did not show a difference between groups (P > 0.05). The proportion of participants meeting consensus targets for sensor-based outcomes are listed in Supplementary Table 10. The proportion of participants in the intervention and control groups meeting the consensus target of TIR >70% were 20.6% and 3.2% (P = 0.001) and were 99.2% and 88.7% for the consensus target of <4% time <70 mg/dL (P = 0.002), respectively, during the 13-week trial period. Treatment comparisons stratified by daytime and nighttime for TIR and hypoglycemic metrics are shown in Table 2 and Supplementary Table 11, respectively.

There was no difference between the intervention and control groups in terms of change in BMI and total daily dose of insulin (Table 2). A summary of insulin requirements for both groups is presented in Supplementary Table 12.

Adverse Events

During the trial period, 13 adverse events among 12 participants were reported in the intervention group, and 10 adverse events among 9 participants were reported in the control group (number of events per 100 person-years, 40.4 and 68.3, respectively) (Table 3). One event in each group was considered a serious adverse event, including one case of severe hypoglycemia in the control group, and an unrelated tibia fracture in the intervention group. Hyperglycemia and/or prolonged hyperglycemia occurred in both groups, but no cases of DKA were reported.

Table 3.

Adverse events

| Event | Intervention group (n = 132) | Control group(n = 62) |

|---|---|---|

| Any adverse event | ||

| Events, n | 13 | 10 |

| Participants with an event, n (%) | 12 (9.1) | 9 (14.5) |

| Events per 100 person-years, n | 40.4 | 68.3 |

| Specific events, no. of events/no. of participants (% of participants) [no. events per 100 person-years] | ||

| Severe hypoglycemia* | 0/0 (0.0) [0.0] | 1/1 (1.6) [6.8] |

| DKA† | 0/0 (0.0) [0.0] | 0/0 (0.0) [0.0] |

| Hypoglycemia‡ | 0/0 (0.0) [0.0] | 0/0 (0.0) [0.0] |

| Hyperglycemia§ | 2/2 (1.5) [6.2] | 0/0 (0.0) [0.0] |

| Prolonged hyperglycemiaǁ | 4/4 (3.0) [12.4] | 5/4 (6.5) [34.1] |

| Other adverse events¶ | 7/6 (4.5) [21.7] | 4/4 (6.5) [27.3] |

*Severe hypoglycemia requiring the assistance of another person due to altered consciousness and requiring another person to actively administer carbohydrate, glucagon, or other resuscitative actions. One case of severe hypoglycemia in the control group was considered a serious adverse event.

†Hyperglycemia with the presence of polyuria; polydipsia; nausea or vomiting; serum ketones >1.5 mmol/L or large/moderate urine ketones; either arterial blood pH <7.30, venous pH <7.24, or serum bicarbonate <15; and treatment provided in a health care facility.

‡Hypoglycemia resulting in an adverse event but otherwise not meeting the definition of severe hypoglycemia.

§Hyperglycemia requiring evaluation, treatment, or guidance from intervention site or resulting in an adverse event but otherwise not meeting the definition of DKA or prolonged hyperglycemia.

ǁMeter blood glucose measuring ≥300 mg/dL for >1 h and ketones >1.0 mmol/L.

¶Other related, but nonglycemic adverse events included one case of a skin reaction. Other nonrelated events included concussion, lumbosciatica, pneumonia, shoulder pain, angina, laryngitis, fibula fracture, foot fracture, and sciatica. One case of a tibia fracture in the intervention group was considered a serious adverse event.

System Use

Participants in the intervention group spent a median (interquartile range) 97.3% (92.7%–99.2%) of time in Automated Mode (mean ± SD 94.1 ± 8.7%) while wearing the system. In the intervention group, participants spent 59.3% of total cumulative study time at the 110 mg/dL target, 28.7% at the 120 mg/dL target, 5.8% at the 130 mg/dL target, 2.5% at the 140 mg/dL target, and 1.9% at the 150 mg/dL target and 1.8% of time with the Activity feature enabled.

There were 54 device issues among 30 participants reported in the intervention group and 9 device issues among 6 participants reported in the control group. In the intervention group, device issues during the trial were related to the Pod (n = 32), CGM (n = 7), Controller (n = 12), and CGM transmitter (n = 3). In the control group, device issues were related to the Pod (n = 1), CGM (n = 6), and CGM receiver (n = 2). A summary of device issues is provided in Supplementary Table 13.

Conclusions

In this parallel-group RCT of adults with type 1 diabetes with suboptimal glycemic outcomes, use of the tubeless AID system was associated with an increase of 4.2 h/day (difference of 17.5%) in the target glucose range compared with pump therapy with a CGM alone. This outcome was accomplished with a significantly lower percentage of time with sensor glucose in a hypoglycemic range (<70 mg/dL) and hyperglycemic range (>180 mg/dL), greater reduction in HbA1c from baseline, no episodes of severe hypoglycemia or DKA, and a greater proportion of participants achieving clinically meaningful improvements in person-reported outcomes with AID use. Notably, these results were achieved in a study population comprising predominantly participants with an HbA1c ≥8% (64 mmol/mol), mirroring the real-world burden of type 1 diabetes where only a fraction of adults meet the target of <7% (53 mmol/mol) (1). Collectively, these results highlight the meaningful clinical and psychosocial impact of AID and its potential to ultimately reduce diabetes-related complications and mortality risk while reducing self-care burden in people with type 1 diabetes.

This trial highlights the undeniable advantage that an AID system can have in improving clinical outcomes beyond that of a nonautomated insulin pump with a CGM. Indeed, despite the addition or continuation of a study CGM with their usual pump therapy in the control group, all primary and secondary outcomes were met in the intervention group, emphasizing that AID use, rather than addition of a CGM, substantially improves glycemic and psychosocial outcomes. Notably, the majority (87%) of participants were already users of the non-AID Omnipod insulin pumps, with 97% of these participants currently or previously using a CGM for their diabetes management. Despite this, switching to an AID system of the same form factor (e.g., tubeless, on-body) was still associated with improved outcomes. Similarly, improvements in TIR were recently reported in prior Omnipod DASH (non-AID) users switching to the Omnipod 5 AID System in a real-world setting (18).

The treatment effects in the current trial reaffirm findings seen among adolescents and adults (aged 14–70 years) in single-arm pivotal and extension trials of tubeless AID use (7,9), as well as several other reports demonstrating similar improvements in glycemic outcomes with the tubeless AID system, despite differences in study design and baseline characteristics of study samples (18–20). While the increase in TIR (9.3%) observed in the pivotal trial was less pronounced than the current study, participants had a more favorable baseline TIR with standard therapy (64.7% vs. 43.9% [intervention group] for the pivotal vs. current trial, respectively) (7). This pattern aligns with research indicating that a lower initial TIR is associated with greater improvements in TIR when using AID systems (21). As such, when examining a subgroup of the pivotal trial adult participants with a baseline HbA1c ≥8% (64 mmol/mol) (mean 8.6% [70 mmol/mol]), TIR was comparable to the current work, starting at 42.6% and increasing to 58.2% with tubeless AID use (7,22). Furthermore, the mean baseline HbA1c level in the current study of 8.5% (69 mmol/mol) is more representative of a real-world population compared with previous studies, given that the U.S. Type 1 Diabetes Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative recently reported a mean HbA1c of 8.4% (68 mmol/mol) in people with type 1 diabetes across all ages (1). Notably, while the greatest improvements in both TIR and HbA1c in the current work occurred in participants with HbA1c ≥8% (64 mmol/mol) at baseline, those with baseline HbA1c <8% (64 mmol/mol) still experienced a marked improvement with use of the tubeless AID system, emphasizing the glycemic benefits of AID for adults with type 1 diabetes across a broad range of baseline HbA1c levels above the recommended clinical target (1).

Other research has also demonstrated the glycemic benefits of AID systems compared with other insulin therapies (e.g., multiple daily injections, sensor-augmented pump therapy) for both open-source and commercially available systems (23–29). The current study results compare favorably with other commercially available systems demonstrating TIR values of ∼60% for people starting with higher HbA1c levels (29–32). For example, participants using other AID systems with an HbA1c ≥8% (64 mmol/mol) or ≥8.5% (69 mmol/mol) achieved a TIR between 60.9% and 64.0% across studies (29–32). Collectively, while most of these and the current study results fall below the recommended target of >70% TIR (17), they all represent marked improvements from baseline, with 20.6% of participants in the current study meeting the recommended target for this metric with AID use (an increase from 1.6% with standard therapy). However, direct comparisons across studies should be considered with caution due to differences in study design and study samples.

Notably, while ∼10% of participants in the present study were using a pump with AID capabilities prior to the study, the systems were not used with automation enabled. While the reasons for this are unknown, our study findings highlight that enabling automation would provide a significant benefit in glycemia. Furthermore, results of the current study demonstrated benefits of AID not only for glycemic outcomes but also for person-reported outcomes of diabetes distress, quality of life, and hypoglycemia confidence, increasing the likelihood that a user would continue using the system and thus receive the persistent glycemic benefits to improve their short- and long-term health outcomes (33). Although beyond the scope of this study, the long-term impact of AID cannot be realized unless systems reduce burden and can be worn consistently, positively impacting quality of life as well as glycemia.

This study has several strengths, including its RCT design that addresses limitations of the previous single-arm pivotal and extension trials of this system by allowing consideration of study-related interactions (7–10). Additionally, the study sample with higher baseline HbA1c levels is more reflective of the real-world burden of type 1 diabetes. Furthermore, our examination of outcomes stratified by subgroup, though not statistically compared, indicated favorable results across various factors, including country, sex, race and ethnicity, age, BMI, baseline glycemic measures, and prior CGM use for those using the tubeless AID system, supporting the generalizability of the findings. Still, the homogeneity of the study population with respect to race and ethnicity and prior device use (97% were current or previous CGM users and 87% were using an earlier Omnipod System as their insulin pump therapy) is a limitation of the current work. Additionally, for participants whose CGM-based measures were collected prospectively during the standard therapy phase, the study effect could have affected the ability to assess their true prestudy glycemia levels. However, the intervention group still experienced a greater TIR during the 13-week trial period compared with the control group.

In conclusion, this tubeless AID system has demonstrated significant improvements in glycemic measures in adults with type 1 diabetes compared with those using standard pump therapy with CGM, as well as improvements in person-reported outcomes. The findings underscore the advantages of AID to improve clinical outcomes and to potentially reduce the short- and long-term complications and increased mortality risk associated with suboptimal glycemic outcomes. These findings support the efficacy of AID systems and further reinforce propositions to establish these systems as the preferred therapy for people with type 1 diabetes (4).

This article contains supplementary material online at https://doi.org/10.2337/figshare.27103729.

Article Information

Acknowledgments. The authors extend their sincere thanks to the study participants and their families. The authors thank Dr. Jodi Bernstein of Jodi Bernstein Medical Writing, who received payment from Insulet Corporation for creating the data tables and supplement and the writing of the first draft of the manuscript, and the Insulet clinical team, including Bonnie Dumais, Anna Busby, Amna Soomro, Anny Caruso, Michaela Sorrell, Tanya Meletlides, Krista Kleve, Jill Cernohous, Abigail Murphy, Robert Shaw, Becky Estabrook, and Alice Bonin, for contributions to the conduct of the study. The authors also thank the dedicated staff at each clinical site who made this study possible.

Funding. This study was funded by Insulet Corporation.

Duality of Interest. E.R. declares consultant/speaker fees from A. Menarini Diagnostics, Abbott, Air Liquide SI, AstraZeneca, Becton, Dickinson and Company, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cellnovo, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Hillo, Insulet Corporation, Johnson & Johnson (Animas, LifeScan), Medtronic, Medirio, Novo Nordisk, Roche, and Sanofi Aventis and research support from Abbott, Dexcom Inc., Insulet Corporation, Roche, and Tandem Diabetes Care. R.S.W. participated in clinical trials, through her institution, sponsored by Amgen, Diasome, Insulet Corporation, Eli Lilly, MannKind, and Tandem and has used Dexcom devices obtained at a reduced cost for clinical studies. G.A. reports consultant fees from Dexcom, Insulet Corporation, and Medscape and has received research support through her institution from Fractyl Health, Insulet Corporation, MannKind, Tandem Diabetes, and Welldoc. B.W.B. reports research support from Insulet Corporation during the conduct of the study; research support from Abbott, Advance, Diasome, Dexcom, Janssen, Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Novo Nordisk, Provention Bio, Sanofi, Sanvita, Senseonics, REMD Biotherapeutics, Xeris, and vTv Therapeutics; and consultant and speaking fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Insulet Corporation, Eli Lilly, MannKind, Medtronic, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Senseonics, Sanofi, Xeris, and Zealand. S.A.B. receives research support to her institution from Dexcom, Insulet Corporation, and Tandem Diabetes Care and participation on a data monitoring board (without fees) for MannKind. K.C. receives research support provided to her institution from Dexcom, Abbott, Medtronic, Eli Lilly, MannKind, and Insulet Corporation and consulting and/or advisory fees from Dexcom, MannKind, and Laxmi. I.B.H. reports research support from Dexcom, Insulet Corporation, Tandem, and MannKind and consulting fees from Abbott, Roche, Hagar, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, and Embecta. M.S.K. reports research support from 89bio, Diamyd Medical, Abbott, Akero Therapeutics, Kowa Pharmaceuticals, Zydus Pharmaceuticals, Biolinq, Corcept Therapeutics, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Insulet Corporation, Ionis, MannKind, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Reata Pharmaceuticals, Inventiva Pharma, and Tandem; clinical events committee fees from Tandem; and advisory board fees from Quest Diagnostics and Corcept Therapeutics. L.M.L. has received consulting fees from Provention Bio, Sanofi, Medtronic, MannKind, Janssen, Eli Lilly, Dexcom, Novo Nordisk, and Vertex. R.A.L. has received consulting fees from Abbott Diabetes Care, Adaptyx Biosciences, Biolinq, Capillary Biomedical, Deep Valley Labs, Gluroo, PhysioLogic Devices, and Tidepool; has served on advisory boards for Provention Bio and Eli Lilly; and receives research support from his institution from Insulet Corporation, Medtronic, and Tandem. A.P. reports personal fees from Abbott Diabetes Care, Dexcom, Diabeloop, Insulet Corporation, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Medtronic, and Sanofi and is an advisory board member for Insulet Corporation and Medtronic. J.-P.R. is an advisory panel member for Sanofi Aventis MSD, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, AstraZeneca, Abbott, Dexcom, Alphadiab, Air Liquide, and Medtronic and has received research funding from Abbott, Air Liquide, Sanofi, Eli Lilly, Insulet Corporation, and Novo Nordisk. V.N.S. reports receiving fees from Dexcom, Insulet Corporation, Embecta, Ascensia Diabetes Care, Tandem Diabetes, Sanofi, Novo Nordisk, Gemonlink, and LumosFit for consulting, advising, or speaking. C.T. reports personal fees from Abbott Diabetes Care, Glooko, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Medtronic, and Sanofi and is an advisory board member for Insulet Corporation and Medtronic. T.T.L. is a full-time employee of and owns stock in Insulet Corporation. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. E.R., R.S.W., G.A., B.W.B., S.A.B., K.C., I.B.H., M.S.K., L.M.L., R.A.L., A.P., J.-P.R., V.N.S., and T.T.L. critically revised the work for important intellectual content. E.R., R.S.W., B.W.B., S.A.B., K.C., I.B.H., M.S.K., L.M.L., R.A.L., A.P., J.-P.R., V.N.S., and C.T. acquired data. E.R., R.S.W., G.A., S.A.B., K.C., I.B.H., M.S.K., L.M.L., R.A.L., J.-P.R., V.N.S., and T.T.L. interpreted the data. E.R. and J.-P.R. analyzed the data. C.T. contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. T.T.L. created the conception and design of the study. All authors made the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. T.T.L. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Prior Presentation. Parts of this study were presented in abstract form at the 17th International Conference on Advanced Technologies and Treatments for Diabetes, Florence, Italy, 6–9 March 2024.

Handling Editors. The journal editors responsible for overseeing the review of the manuscript were Elizabeth Selvin and Thomas P.A. Danne.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by Insulet Corporation.

Footnotes

Clinical trial reg. no. NCT05409131, clinicaltrials.gov

*A complete list of OP5-003 Research Group members can be found in the supplemental material online.

Contributor Information

OP5-003 Research Group:

Eric Renard, Anne Farret, Orianne Villard, Manal Al Masri, Ruth S. Weinstock, Sheri L. Stone, Suzan Bzdick, Grazia Aleppo, Jelena Kravarusic, Evelyn Guevara, Stefanie Herrmann, Samsam Penn, Bruce W. Bode, Jonathan Ownby, Joseph Johnson, Courtney Tabb, Amanda Maxson, Ethan Dunn, Monica Lewis, Dajah Reed, Cate Wilby, Sue A. Brown, Meaghan Stumpf, Morgan Fuller, Carlene Alix, Kristin Castorino, Mei Mei Church, Ashley Thorsell, Nina Shelton, Hannah Blanscet, Irl B. Hirsch, Faisal Malik, Xenia Averkiou, Xiaofu Dong, Patali Mandava, Mark S. Kipnes, Amna Salhin, Kalicia Christie, Stephanie Beltran, Vanessa Ramon, Danielle Oliver, Krizia Rosas, Suzanne Mulvey, Terri Ryan, Joann Hernandez, Fatemeh Movaghari Pour, Chad Hirchak, Lori M. Laffel, Elvira Isganaitis, Louise Ambler-Osborn, Evelyn Goroza, Jade Doolan, Christine Turcotte, Christopher Herndon, Lisa Volkening, Mary Oliveri, Laura Kollar, Rayhan A. Lal, Bruce A. Buckingham, Michael Hughes, Lisa Norlander, Ryan Kingman, Bailey Suh, Liana Hsu, Alfred Penfornis, Catherine Petit, Marcelle Siadoua, Jean-Pierre Riveline, Jean-François Gautier, Tiphaine Vidal-Trecan, Jean Baptiste Julia, Charline Potier, Djamila Bellili, Viral N. Shah, Halis Kaan Akturk, Hal Joseph, Alexis Moore, Ashleigh Downs, Christie Beatson, Sonya Walker, Tanner Bloks, Lubna Qamar, Darya Wodetzki, Ryan Shoemaker, Charles Thivolet, Sylvie Villar Fimbel, Redhouane Hami, Kaisa Kivilaid, Trang T. Ly, Bonnie Dumais, Todd Vienneau, Lauren M Huyett, and Lindsey R. Conroy

References

- 1. Ebekozien O, Mungmode A, Sanchez J, et al. Longitudinal trends in glycemic outcomes and technology use for over 48,000 people with type 1 diabetes (2016–2022) from the T1D exchange quality improvement collaborative. Diabetes Technol Ther 2023;25:765–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Herman WH, Braffett BH, Kuo S, et al. What are the clinical, quality-of-life, and cost consequences of 30 years of excellent vs. poor glycemic control in type 1 diabetes? J Diabetes Complications 2018;32:911–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gregory GA, Robinson TIG, Linklater SE, et al.; International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas Type 1 Diabetes in Adults Special Interest Group . Global incidence, prevalence, and mortality of type 1 diabetes in 2021 with projection to 2040: a modelling study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2022;10:741–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Phillip M, Nimri R, Bergenstal RM, et al. Consensus recommendations for the use of automated insulin delivery technologies in clinical practice. Endocr Rev 2023;44:254–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Forlenza GP, Lal RA.. Current status and emerging options for automated insulin delivery systems. Diabetes Technol Ther 2022;24:362–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Andreozzi F, Candido R, Corrao S, et al. Clinical inertia is the enemy of therapeutic success in the management of diabetes and its complications: a narrative literature review. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2020;12:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brown SA, Forlenza GP, Bode BW, et al.; Omnipod 5 Research Group . Multicenter trial of a tubeless, on-body automated insulin delivery system with customizable glycemic targets in pediatric and adult participants with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2021;44:1630–1640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sherr JL, Bode BW, Forlenza GP, et al.; Omnipod 5 in Preschoolers Study Group . Safety and glycemic outcomes with a tubeless automated insulin delivery system in very young children with type 1 diabetes: a single-arm multicenter clinical trial. Diabetes Care 2022;45:1907–1910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Criego AB, Carlson AL, Brown SA, et al. Two years with a tubeless automated insulin delivery system: a single-arm multicenter trial in children, adolescents, and adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2024;26:11–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. DeSalvo DJ, Bode BW, Forlenza GP, et al. Glycemic outcomes persist for up to 2 years in very young children with the Omnipod 5 automated insulin delivery system. Diabetes Technol Ther 2024;26:383–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Forlenza GP, Buckingham BA, Brown SA, et al. First outpatient evaluation of a tubeless automated insulin delivery system with customizable glucose targets in children and adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2021;23:410–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Earles J, et al. Assessing psychosocial distress in diabetes: development of the diabetes distress scale. Diabetes Care 2005;28:626–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Hessler D, et al. Investigating hypoglycemic confidence in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2017;19:131–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Burroughs TE, Desikan R, Waterman BM, et al. Development and validation of the diabetes quality of life brief clinical inventory. Diabetes Spectrum 2004;17:41–49 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fisher L, Hessler D, Polonsky W, et al. Diabetes distress in adults with type 1 diabetes: prevalence, incidence and change over time. J Diabetes Complications 2016;30:1123–1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Klonoff DC, Wang J, Rodbard D, et al. A glycemia risk index (GRI) of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia for continuous glucose monitoring validated by clinician ratings. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2023;17:1226–1242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Battelino T, Danne T, Bergenstal RM, et al. Clinical targets for continuous glucose monitoring data interpretation: recommendations from the international consensus on time in range. Diabetes Care 2019;42:1593–1603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Forlenza GP, DeSalvo DJ, Aleppo G, et al. Real-world evidence of Omnipod 5 Automated Insulin Delivery System use in 69,902 people with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2024;26:514–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Folk S, Zappe J, Wyne K, et al. Comparative effectiveness of hybrid closed-loop automated insulin delivery systems among patients with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2024:19322968241234948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marks BE, Meighan S, Zehra A, et al. Real-world glycemic outcomes with early Omnipod 5 use in youth with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2023;25:782–789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schoelwer MJ, Kanapka LG, Wadwa RP, et al.; iDCL Trial Research Group . Predictors of time-in-range (70-180 mg/dL) achieved using a closed-loop control system. Diabetes Technol Ther 2021;23:475–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Davis GM, Peters AL, Bode BW, et al. Safety and efficacy of the Omnipod 5 Automated Insulin Delivery System in adults with type 2 diabetes: from injections to hybrid closed-loop therapy. Diabetes Care 2023;46:742–750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Choudhary P, Kolassa R, Keuthage W, et al.; ADAPT Study Group . Advanced hybrid closed loop therapy versus conventional treatment in adults with type 1 diabetes (ADAPT): a randomised controlled study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2022;10:720–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Burnside MJ, Lewis DM, Crocket HR, et al. Open-source automated insulin delivery in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2022;387:869–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boughton CK, Hartnell S, Lakshman R, et al. Fully closed-loop glucose control compared with insulin pump therapy with continuous glucose monitoring in adults with type 1 diabetes and suboptimal glycemic control: a single-center, randomized, crossover study. Diabetes Care 2023;46:1916–1922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Garg SK, Grunberger G, Weinstock R, et al.; Adult and Pediatric MiniMed HCL Outcomes 6-Month RCT: HCL versus CSII Control Study Group . Improved glycemia with hybrid closed-loop versus continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion therapy: results from a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Technol Ther 2023;25:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Christensen MB, Ranjan AG, Rytter K, et al. Automated insulin delivery in adults with type 1 diabetes and suboptimal HbA1c during prior use of insulin pump and continuous glucose monitoring: a randomized controlled trial. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2024:19322968241242399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Beck RW, Russell SJ, Damiano ER, et al. A multicenter randomized trial evaluating fast-acting insulin aspart in the bionic pancreas in adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2022;24:681–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kruger D, Kass A, Lonier J, et al. A multicenter randomized trial evaluating the insulin-only configuration of the bionic pancreas in adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2022;24:697–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ekhlaspour L, Town M, Raghinaru D, et al. Glycemic outcomes in baseline hemoglobin A1C subgroups in the international diabetes closed-loop trial. Diabetes Technol Ther 2022;24:588–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Michaels VR, Boucsein A, Watson AS, et al. Glucose and psychosocial outcomes 12 months following transition from multiple daily injections to advanced hybrid closed loop in youth with type 1 diabetes and suboptimal glycemia. Diabetes Technol Ther 2024;26:40–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Crabtree TSJ, Griffin TP, Yap YW, et al.; ABCD Closed-Loop Audit Contributors . Hybrid closed-loop therapy in adults with type 1 diabetes and above-target HbA1c: a real-world observational study. Diabetes Care 2023;46:1831–1838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nefs G. The psychological implications of automated insulin delivery systems in type 1 diabetes care. Front Clin Diabetes Healthc 2022;3:846162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]