Abstract

The lack of specific T-cell help in immune responses to thymus-independent antigens results in weak, predominantly immunoglobulin M-mediated immunity with little or no memory. In the work presented here we show how the exogenous stimulation of CD40 by monoclonal antibodies can mimic T-cell help, resulting in enhanced immune responses which are protective against bacterial infection.

Antigens are classified into three groups: thymus (T)-dependent, T-independent type 1 (TI-1), and TI-2 antigens. T-dependent antigens, including most proteins, induce secondary immune responses characterized by immunoglobulin G (IgG) production due to specific T-cell help. TI antigens, however, lack this specific T-cell help and thus induce weak, predominantly IgM-mediated responses, with an inefficient induction of isotype switching, affinity maturation, and little or no booster effect after the second exposure to the antigen. TI-1 antigens have inherent mitogenic activity and include bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS), whereas TI-2 antigens such as bacterial capsular polysaccharides activate via multiple epitopes which cross-link the B-cell receptor.

The CD40 antigen is constitutively expressed on mature B cells (2), and its ligand, CD154, is transiently expressed on activated T helper cells (1). It is the interaction between this receptor-ligand pair which mediates specific T-cell help in response to T-dependent antigens, providing signals crucial for B-cell activation, proliferation, differentiation, and isotype switching (reviewed in references 5 and 9).

Previous work in our laboratory showed that the coinjection of an agonistic anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody (MAb) with a TI-2 antigen (pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide) successfully mimicked T-cell help, leading to enhanced antibody production, isotype switching, and protection against infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae (3). However, TI-1 antigens behave differently from TI-2 antigens due to intrinsic mitogenicity and tend not to be multivalent (8).

The aim of the work presented here was to determine whether the exogenous stimulation of CD40 by MAbs could also mimic T-cell help in a TI-1 (LPS) antigen murine model and, if so, whether this could protect against bacterial infection.

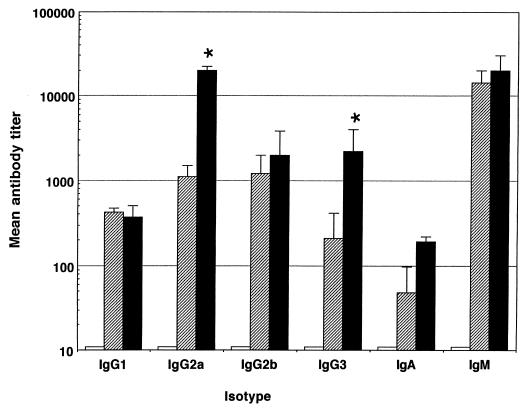

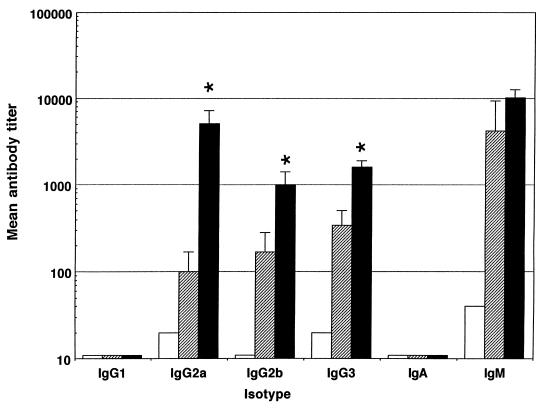

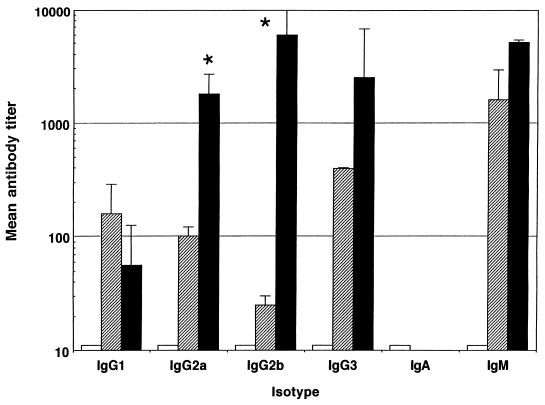

Female BALB/c mice aged 6 to 12 weeks (University of Sheffield, Field Laboratories) were used for all experiments described. Five mice per group were immunized intraperitoneally with 500 μg of anti-CD40 MAb, either 1C10 (6) or an antibody with similar properties, 10C8 (1a), and 10 μg of LPS. Control groups were immunized with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or with 10 μg of LPS and 500 μg of the control antibody GL117 (rat IgG2a). Ten days after immunization, mice were bled via the dorsal tail vein, and the sera were stored at −20°C. As responses to different LPS vary, we immunized mice with LPS from Escherichia coli (serotype 026:B6), Salmonella typhi (purchased from Sigma as S. typhosa (LPS), and Salmonella typhimurium (Sigma). Antibody titers against LPS were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as follows. ELISA plates were coated overnight with the appropriate LPS at a concentration of 10 μg/ml in PBS at 4°C, plates were blocked with 1% fish gelatin for 1 h at room temperature (RT), and then serial dilutions (in PBS) of serum samples were made across the plate. After a 1-h incubation at RT, plates were washed and isotype-specific horseradish peroxidase conjugates (Southern Biotech Associates, Birmingham, Ala.) were added at a 1/2,000 dilution. After a further 1-h incubation (RT), plates were washed again and substrate was added. Plates were read after 20 min at 450 nm. Mean endpoint titers were calculated as the reciprocal of the dilution at which the optical density for the test serum was at or below that measured for normal mouse serum. Any negative results were given a log titer of 10, the lowest dilution used. Figure 1 shows that CD40 stimulation with MAb leads to significantly enhanced IgG2a and IgG3 antibody production against E. coli LPS (Student’s t test; P < 0.05). Enhanced IgG2a and IgG2b or IgG3 antibody production was also observed in mice immunized with either S. typhi or S. typhimurium LPS and anti-CD40 (Fig. 2 and 3).

FIG. 1.

CD40 stimulation with the 1C10 MAb enhances IgG2a and IgG3 responses to E. coli LPS. Mean logarithmic antibody titers in sera obtained 10 days after intraperitoneal immunization by capture ELISA are shown for each isotype. Error bars indicate standard deviations, and statistical significance compared with control groups (∗) as determined by Student’s t test (P < 0.05) is shown. Data are shown for PBS (white bars), LPS plus GL117 (crosshatched bars), and LPS plus anti-CD40 (black bars).

FIG. 2.

CD40 stimulation with the 10C8 MAb enhances IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3 responses to S. typhi LPS. Mean logarithmic antibody titers in sera obtained 10 days after intraperitoneal immunization by capture ELISA are shown for each isotype. Error bars indicate standard deviations, and statistical significance compared with control groups (∗) as determined by Student’s t test (P < 0.05) is shown. Data are shown for PBS (white bars), LPS plus GL117 (crosshatched bars), and LPS plus anti-CD40 (black bars).

FIG. 3.

CD40 stimulation with the 10C8 MAb enhances IgG2a and IgG2b responses to S. typimurium LPS. Mean logarithmic antibody titers in sera obtained 10 days after intraperitoneal immunization by capture ELISA are shown for each isotype. Error bars indicate standard deviations, and statistical significance compared with control groups (∗) as determined by Student’s t test (P < 0.05) is shown. Data are shown for PBS (white bars), LPS plus GL117 (crosshatched bars), and LPS plus anti-CD40 (black bars).

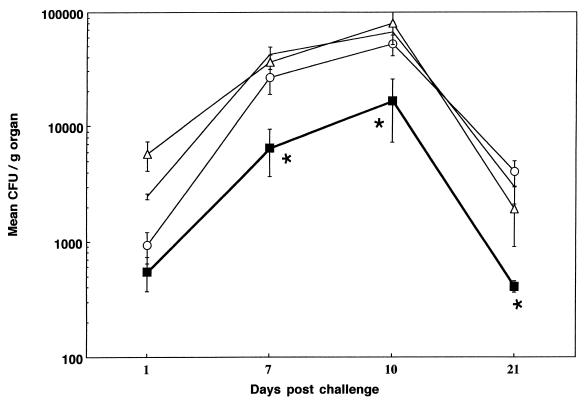

In order to determine whether the enhanced, isotype-switched responses had any functional significance, mice which had been immunized 10 days previously with S. typhimurium LPS were challenged intravenously with 3 × 106 CFU of the aroA mutant SL3261. This was kindly provided by C. Hormaeche (University of Newcastle, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom) with the permission of the strain’s originator, B. Stocker of Stanford University, Stanford, Calif. (7). Four mice from each group were then sacrificed on days 1, 7, 10, and 21 after bacterial challenge. Spleens and livers were aseptically removed from these animals and homogenized. Homogenates were serially diluted and plated onto Luria-Bertani agar plates, and mean numbers of CFU for each group were determined. Figure 3 shows that the production of antibodies against S. typhimurium LPS is enhanced by the addition of anti-CD40, and it appears clear from the data shown in Fig. 4 that this enhancement is indeed protective against infection with the SL3261 strain, significantly reducing the bacterial load in the spleen (Fig. 4) and the liver (data not shown). As anti-CD40 alone has been shown to have some protective effect against Leishmania parasites (4), we included a group of mice given anti-CD40 alone in the protection experiment. There was no effect of anti-CD40 administered without LPS on the course of the infection.

FIG. 4.

CD40 stimulation with the 10C8 MAb induces a protective response to the SL3261 strain of S. typhimurium. Mean CFU per gram of spleen are shown for groups of four mice at each time point (1, 7, 10, and 21 days postchallenge). Error bars indicate standard deviations, and statistical significance against all control groups (∗) as determined by Student’s t test (P < 0.05) is shown. Data are shown for PBS (no symbols), anti-CD40 alone (circles), LPS plus GL117 (triangles), and LPS plus anti-CD40 (squares).

The data presented show that the exogenous stimulation of CD40 with MAbs can mimic T-cell help in TI-1 immune responses. This mimicry leads to the enhancement of the production of IgG against bacterial LPS, and the increased levels of anti-LPS IgG in sera are sufficient to significantly reduce the number of bacteria in the spleens and livers of infected animals. These findings point the way to the development of cheap, effective immunological adjuvants. Given that the anti-CD40 MAbs in this study were given in large doses and merely as a mixture with an antigen, no specific targeting of antigen-specific B cells would be expected, apart from that inherent in the synergy between antigen receptor stimulation and CD40 ligation (6). It is very likely that the dose of antibody and its effectiveness as an immunological adjuvant will be greatly improved by conjugating anti-CD40 to an antigen or by coentrapping the two in microcapsules. These approaches are currently being investigated in our laboratory.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Wellcome Trust (042251).

REFERENCES

- 1.Armitage R J, Fanslow W C, Strockbine L, Sato T A, Clifford K N, Macduff B M, Anderson D M, Gimpel S D, Davis-Smith T, Maliszewski C R, Clark E A, Smith C A, Grabstein K H, Cosman D, Spriggs M K. Molecular and biological characterisation of a murine ligand for CD40. Nature. 1992;357:80–82. doi: 10.1038/357080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1a.Barr, T. A., and A. W. Heath. Unpublished data.

- 2.Clark E A, Ledbetter J A. Activation of human B-cells mediated through two distinct cell surface differentiation antigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4494–4498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.12.4494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dullforce P, Sutton D C, Heath A W. Enhancement of T-cell independent immune responses in vivo by CD40 antibodies. Nat Med. 1998;4:88–91. doi: 10.1038/nm0198-088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferlin W G, von der Weid T, Cottrez F, Ferrick D A, Coffman R L, Howard M C. The induction of a protective response in Leishmania major-infected BALB/c mice with anti-CD40 mAb. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:525–531. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199802)28:02<525::AID-IMMU525>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foy T M, Arrufo A, Bajorath J, Buhlmann J E, Noelle R J. Immune regulation by CD40 and its ligand gp39. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:591–617. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heath A W, Wu W W, Howard M C. Monoclonal antibodies to murine CD40 define two distinct functional epitopes. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1828–1834. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoiseth S K, Stocker B A. Aromatic-dependent S. typhimurium are nonvirulent and are effective as live vaccines. Nature. 1981;219:238–239. doi: 10.1038/291238a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mosier D B, Subbarao B. Thymus-independent antigens: complexity of B-lymphocyte activation revealed. Immunol Today. 1982;3:217–222. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(82)90095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Kooten C, Banchereau J. CD40-CD40 ligand: a multifunctional receptor-ligand pair. Adv Immunol. 1996;61:1–77. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60865-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]