Abstract

Objective

Malnutrition is a common issue in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), leading to compromised immune function and diminished treatment efficacy. This is particularly concerning for therapies targeting the PD-1 pathway, which are pivotal in cancer treatment. The aim of this retrospective study was to explore the potential benefits of immunonutrition in improving immune responses and clinical outcomes for these patients.

Methods

In the study, 49 individuals diagnosed with HNSCC were enrolled and divided into two groups: one group received specialized immunonutrition support designed to enhance immune function, while the other group received standard nutritional care. The researchers assessed immune function by evaluating CD4+ and CD8+ T cell counts, which are critical indicators of immune health. Additionally, clinical outcomes were monitored, focusing on infection rates and the duration of hospital stays.

Results

Patients who received immunonutrition showed a significant improvement in immune function, as indicated by higher levels of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Furthermore, these patients experienced shorter recovery times and lower infection rates compared to those receiving standard nutrition.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that immunonutrition may play a vital role in enhancing the effectiveness of cancer therapies, including PD-1 inhibitors. By supporting immune health, immunonutrition could potentially improve patient outcomes and quality of life during and after treatment. This study underscores the importance of integrating nutritional support into cancer care, particularly for patients with HNSCC. As the field of oncology continues to evolve, incorporating strategies that address nutritional deficiencies could be key to optimizing treatment efficacy and improving overall survival rates.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12672-024-01598-6.

Keywords: Immunonutrition, HNSCC, Immune function, PD-1 therapy

Introduction

Globally, head and neck cancer (HNSCC) presents a significant health challenge, with high prevalence and mortality rates. A crucial aspect often overshadowing patient outcomes is malnutrition, significantly impacting immune function and the efficacy of therapeutic interventions [1]. The detrimental effects of malnutrition, particularly on immune status, necessitate a reevaluation of nutritional interventions as a cornerstone of comprehensive cancer care.

Immunonutrition, designed to modulate immune responses through specific nutrients, emerges as a promising adjunctive therapy. This approach, enriching the diet with compounds like arginine, omega-3 fatty acids, and nucleotides, aims to bolster the patient’s immune capabilities, potentially enhancing the response to cancer treatments [2, 3]. Recent studies highlight the role of omega-3 fatty acids in reducing inflammation and promoting the differentiation and proliferation of T cells. Arginine, a conditionally essential amino acid, is vital for T cell activation and proliferation, and its supplementation has been linked to improved immune responses in various cancer models [4–6]. Notably, the effectiveness of advanced therapies, such as those targeting the programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) pathway, partially hinges on the patient’s immune system functionality. PD-1 inhibitors, by unmasking cancer cells to the immune system, represent a breakthrough in oncology, though their success is markedly influenced by the patient's immune health [7]. Patients receiving immunonutrition alongside standard cancer treatments have shown enhanced CD4+/CD8+ T cell ratios, indicating a more robust immune response. Furthermore, the combination of immunonutrition with immunotherapy, such as PD-1 inhibitors, is being explored for its synergistic effects, potentially leading to improved therapeutic outcomes [8].

Preliminary evidence suggests that immunonutrition might have a potential in impacting immune cell profiles [9], but rarely have such results been repeatedly proven and generalized to other ethnicity group. This study primarily investigates the influence of perioperative immunonutrition on these critical immune markers and, secondarily, its potential to complement PD-1 blockade therapy. Our findings point to a notable improvement in CD4+/CD8+ T cell ratios within the immunonutrition group, irrespective of PD-1 treatment status, highlighting the fundamental role of nutritional support in enhancing immune surveillance and therapy response [10].

This article shifts the spotlight from the direct effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors to the broader, yet equally vital, aspect of immunonutrition in improving immune function, particularly through the modulation of CD4+/CD8+ T cell dynamics. Such insights underscore the indispensable value of integrating nutritional strategies into the oncological treatment paradigm, aiming for a holistic approach to cancer care [11].

Method

Patient selection

This study was designed as a retrospective case–control study that was undertaken in in Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital from December 2021 to December 2023. The trial was conducted by the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (2013 version). Inclusion criteria encompassed patients diagnosed with head and neck cancer, aged 18 to 70 years, and possessing an expected lifespan of over 6 months. Exclusion criteria eliminated patients with severe comorbidities, a history of allergies, prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy treatment, and other factors potentially affecting study outcomes. The study successfully enrolled 49 eligible patients, who were then allocated to either the study group or the control group based on predefined criteria. Baseline characteristics of both groups were analyzed to confirm comparability.

This research was accepted by the Review Institution of the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital (Ethical Review No.SYSKY-2023-315-02). Participants provided informed consent, fully understanding the research's purpose and potential risks and benefits, safeguarding their autonomy and confidentiality.

Study groups and interventions

In this study, patients were divided into two groups according to the selection of enteral nutrition formula: the intervention cohort, which received immunonutrition support (IMN group). The immunonutrition support was a cancer-specific nutritional supplement powder product (Impact Oral®; Nestlé), which included nutrients such as arginine, omega-3 fatty acids, and nucleotides, specifically chosen to enhance immune function, improve overall nutritional status, and aid in postoperative recovery. And the control group, which received standard enteral nutrition support (SEN group). The standard enteral nutrition support was a powder product (Ensure®; Abbott), which contains 35 nutrients, such as linoleic acid, vitamins, dietary fiber, calcium, and iron, along with three high-quality proteins (lipoprotein, whey protein, and soy protein), The IMN group consisted of 30 patients who began receiving the immunonutrition regimen 1 day before surgery, continuing for 7 days post-surgery. Conversely, the control group, comprising 19 patients. This regimen supplied basic energy and nutrients but lacked the specific immune-enhancing components present in the study group’s nutrition. Additionally, the study examined the combined effect of immunonutrition and PD-1 therapy, investigating the potential synergistic benefits of this combination in immunotherapeutic strategies for HNSCC. Within the control group, 13 patients received anti-PD-1 antibody therapy, while 6 did not. In the study group, 22 patients were treated with anti-PD-1 antibody therapy, with the remaining 8 not receiving this treatment.

Data collection

Baseline information of patients was collected, including age, gender, tumor location; immune function indicators such as white blood cell count, proportions of other lymphocyte subgroups, pre- and post-treatment ratios of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, the ratio of CD4+ to CD8+ T cells, and the increase rate of CD4+ T cells after treatment; clinical outcome indicators including in-hospital infection rate, length of hospital stay, and pain intensity score (Numeric Rating Scale, NRS), as well as the patients’ nutritional status indicator Body Mass Index (BMI).

Assessment methods

To assess the immune status of the body, the study focused on the activity of immune cells, particularly the proportions of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, the ratio of CD4+ T to CD8+ T cells, and their dynamic changes before and after treatment. Moreover, the study recorded the postoperative in-hospital infection rate and length of hospital stays to evaluate the impact of perioperative immunonutrition support therapy on the prognosis of patients with HNSCC. Additionally, the study recorded adverse reactions experienced by patients in both groups and issues related to tolerance of nutritional support to ensure the safety of the treatment.

Statistic analysis

In this study, all collected data were first subjected to preliminary screening to exclude any incomplete or aberrant data records. Subsequently, the data were preprocessed, which included cleaning and coding, to facilitate further analysis. Appropriate statistical methods were applied to handle missing data. The normality of the continuous variables was tested by the Shapiro–Wilk test. Normally distributed variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), with significance analyzed by Student’s t-test. Abnormally distributed variables were expressed as the median and interquartile range (IQR), with significance analyzed by the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables are expressed as frequency and percentage, with significance analyzed by the Chi-square test or Fisher exact probability method. We handled missing values through multiple imputation. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4. All tests were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Result

Overall

It was observed that, following treatment, the IMN group exhibited an increase in the CD4+/CD8+ T cell percentages from their baseline measures. While initial comparisons of CD4+/CD8+ T cell ratios between the SEN and IMN groups showed parallel levels, a notable divergence emerged in the post-treatment phase (Table S1 and Table S2).

Further subgroup analysis among those undergoing anti-PD-1 antibody therapy revealed that both groups experienced uplifts in post-treatment CD4+ T cell percentages and their CD4/CD8 ratios. However, this improvement was significantly more pronounced within the IMN cohort (Figure S1 and Figure S2).

Crucially, the investigation also highlighted a reduction in hospital stay durations, with the IMN group exhibiting a considerably shorter Length of stay (LOS) in comparison to the SEN group, a finding quantitatively supported by data in Table 4. This effect was even more pronounced among patients receiving anti-PD-1 antibody treatment, where those in the IMN group enjoyed markedly reduced hospital stays relative to their SEN counterparts.

Table 4.

The impact of treatment on hospitalization related indicators

| Subgroup | Hospital-acquired infection | Length of hospital stay | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | P value | P value | ||

| Total | P = 0.816 | 0.002 | |||

| SEN group (N = 19) | 18 (94.7%) | 1 (5.3%) | 15.8 (5.63) | ||

| IMN group (N = 30) | 30 (100%) | 0 (0.00%) | 11.0 (3.31) | ||

| SEN group (N = 19) | P = 0.684 | 0.166 | |||

| Non-PD1 group (N = 6) | 5 (83.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | 18.0 (3.16) | ||

| PD-1 group (N = 13) | 13 (100%) | 0 (0.00%) | 14.8 (6.32) | ||

| IMN group (N = 30) | – | 0.007 | |||

| Non-PD1 group (N = 8) | 8 (100%) | 0 (0.00%) | 13.2 (2.12) | ||

| PD-1 group(N = 22) | 22 (100%) | 0 (0.00%) | 10.1 (3.30) | ||

| PD-1 group (N = 35) | – | 0.024 | |||

| SEN (N = 13) | 13 (100%) | 0 (0.00%) | 14.8 (6.32) | ||

| IMN (N = 22) | 22 (100%) | 0 (0.00%) | 10.1 (3.30) | ||

| Non-PD1 group (N = 14) | P = 0.881 | 15.3 (3.50) | 0.012 | ||

| SEN (N = 6) | 5 (83.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | 18.0 (3.16) | ||

| IMN (N = 8) | 8 (100%) | 0 (0.00%) | 13.2 (2.12) | ||

Baseline characteristics of including patients

A total of 49 patients were enrolled, including 19 in the SEN group and 30 in the IMN group. The baseline clinical characteristics were balanced between the two groups (Table 1). There were no significant differences in gender, age, tumor site, BMI and NRS score between two groups.

Table 1.

The baseline clinical characteristics of the two groups

| Total number | Total N = 49 |

SEN group | IMN group | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 19 | N = 30 | |||

| Gender | 0.363 | |||

| Male | 44 (89.8%) | 16 (84.2%) | 28 (93.3%) | |

| Female | 5 (10.2%) | 3 (15.8%) | 2 (6.67%) | |

| Site | 0.305 | |||

| Nasopharynx | 11 (22.4%) | 4 (21.1%) | 7 (23.3%) | |

| Oropharynx | 7 (14.3%) | 3 (15.8%) | 4 (13.3%) | |

| Glottic laryngeal | 19 (38.8%) | 10 (52.6%) | 9 (30.0%) | |

| Supraglottic laryngeal | 5 (10.2%) | 0 (0.00%) | 5 (16.7%) | |

| Tonsils | 7 (14.3%) | 2 (10.5%) | 5 (16.7%) | |

| Age | 1 | |||

| < 70 | 40 (81.6%) | 16 (84.2%) | 24 (80.0%) | |

| ≥ 70 | 9 (18.4%) | 3 (15.8%) | 6 (20.0%) | |

| BMI | 0.743 | |||

| < 18.5 | 12 (24.5%) | 4 (21.1%) | 8 (26.7%) | |

| ≥ 18.5 | 37 (75.5%) | 15 (78.9%) | 22 (73.3%) | |

| NRS | 2.33 (1.43) | 2.21 (1.27) | 2.40 (1.54) | 0.643 |

IMN immunonutrition, SEN standard enteral nutrition

Comparison of immune cell activity between two groups

To check the immune cell activity between two groups, we further collected amount of immune cell subtypes as below. Post-treatment CD4+ T/CD8+ T cell percentage were significantly higher of the IMN group. Table 2 shows the differences of immune cells between two groups.

Table 2.

Differences of immune cells between two groups

| Total | SEN group | IMN group | Between-group difference P | Within-group difference from baseline P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Number | N = 49 | N = 19 | N = 30 | SEN group | IMN group | |

| Baseline CD4+ T cell percentage (%) | 38.7 (10.7) | 37.8 (9.06) | 39.3 (11.7) | 0.608 | – | – |

| Baseline CD8+ T cell percentage (%) | 25.2 (6.38) | 26.3 (6.15) | 24.4 (6.52) | 0.308 | – | – |

| Baseline CD4+ T/CD8+ T cell ratio | 1.69 (0.77) | 1.56 (0.71) | 1.77 (0.81) | 0.333 | – | – |

| Post-treatment CD4+ T cell percentage (%) | 45.8 (13.7) | 40.4 (10.8) | 48.3 (14.3) | 0.018 | 0.176 | < 0.001 |

| Post-treatment CD8+ T cell percentage (%) | 22.0 (7.47) | 24.6 (8.53) | 20.3 (6.31) | 0.069 | 0.231 | 0.002 |

| Post-treatment CD4+ T/CD8+ T cell ratio | 2.41 (1.31) | 1.96 (1.16) | 2.70 (1.33) | 0.045 | 0.0496 | < 0.001 |

| Δ CD4+ T cell percentage (%) | 7.09 (7.98) | 2.63 (8.14) | 9.92 (6.56) | 0.003 | – | – |

| Δ CD8+ T cell percentage (%) | − 3.18 (6.43) | − 1.72 (6.04) | − 4.10 (6.59) | 0.203 | – | – |

| Δ CD4+ T/CD8+ T cell percentage (%) | 0.72 (0.91) | 0.40 (0.83) | 0.93 (0.92) | 0.043 | – | – |

IMN immunonutrition, SEN standard enteral nutrition

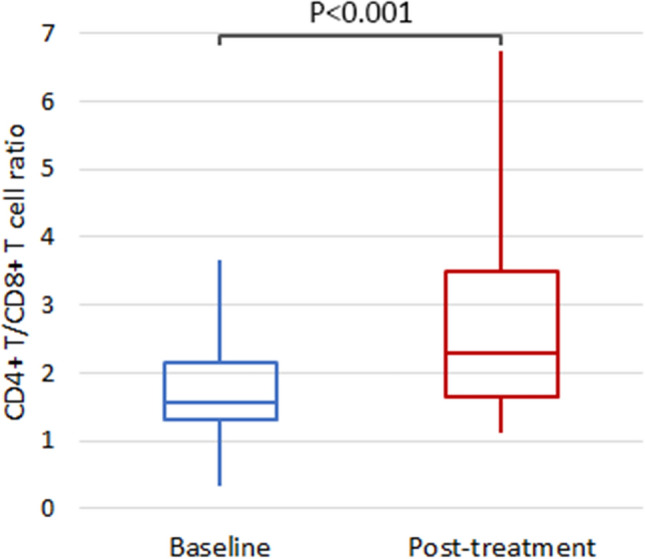

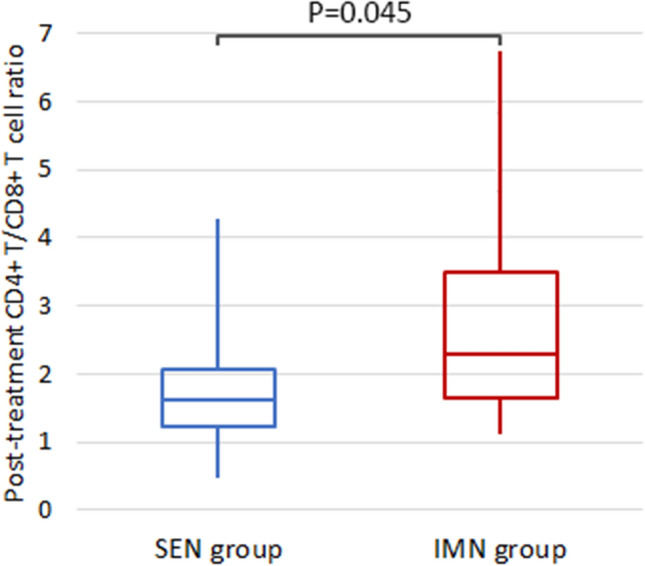

The IMN group not only shows a significant improvement from baseline (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1), but also outperforms the SEN group in the comparative analysis (P = 0.045) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

The comparison of post-treatment versus baseline CD4+ T/CD8+ T cell ratio of the IMN group

Fig. 2.

The comparison of post-treatment CD4+ T/CD8+ T cell ratio between two groups

Subgroup analysis for patients receiving anti-PD-1 antibody

To investigate the synergistic effect of immunonutrition and immunotherapy on immune cell activity, we conducted a subgroup analysis within each treatment group. Among the 35 patients who received anti-PD-1 antibody therapy, 13 were treated with standard enteral nutrition (SEN) and 22 with immunonutrition (IMN). The results indicated that the mean post-treatment CD4+/CD8+ T cell ratio was higher in patients receiving IMN compared to those treated with SEN (2.98 vs. 2.24, P = 0.127) (Table 3), though the difference was not statistically significant. Compared to baseline, those in SEN group who received anti-PD-1 antibody treatment had a slight increase in post-treatment CD4+ T cell percentage (41.6% vs 39.2%, P = 0.322) and CD4/CD8 ratio (2.24 vs 1.71, P = 0.058) (Table 3). However, the difference did not reach statistical significance.

Table 3.

Comparison of immune cell activity between two groups with combination treatment of anti-PD-1 antibodies

| PD-1 group | Total (N = 35) | SEN group (N = 13) | IMN group (N = 22) | P value | Within-group difference from baseline P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEN group | IMN group | |||||

| Baseline CD4+ T cell percentage (%) | 39.8 (11.8) | 39.2 (9.59) | 40.1 (13.2) | 0.813 | – | – |

| Baseline CD8+ T cell percentage (%) | 23.8 (7.28) | 24.8 (6.27) | 24.0 (7.35) | 0.732 | – | – |

| Baseline CD4+ T/CD8+ T cell ratio | 1.89 (0.94) | 1.71 (0.75) | 1.88 (0.90) | 0.507 | – | – |

| Post-treatment CD4+ T cell percentage (%) | 48.6 (14.4) | 41.6 (11.0) | 52.7 (14.8) | 0.017 | 0.322 | < 0.001 |

| Post-treatment CD8+ T cell percentage (%) | 20.7 (7.29) | 22.3 (8.96) | 19.7 (6.11) | 0.362 | 0.187 | 0.005 |

| Post-treatment CD4+ T/CD8+ T cell ratio | 2.70 (1.39) | 2.24 (1.28) | 2.98 (1.41) | 0.127 | 0.058 | < 0.001 |

| Δ CD4+ T cell percentage (%) | 8.84 (8.24) | 2.45 (8.54) | 12.6 (5.28) | 0.001 | – | – |

| Δ CD8+ T cell percentage (%) | − 3.11 (6.47) | − 2.45 (6.32) | − 4.27 (6.42) | 0.422 | – | – |

| Δ CD4+ T/CD8+ T cell percentage (%) | 0.81 (1.00) | 0.53 (0.92) | 1.10 (0.97) | 0.099 | – | – |

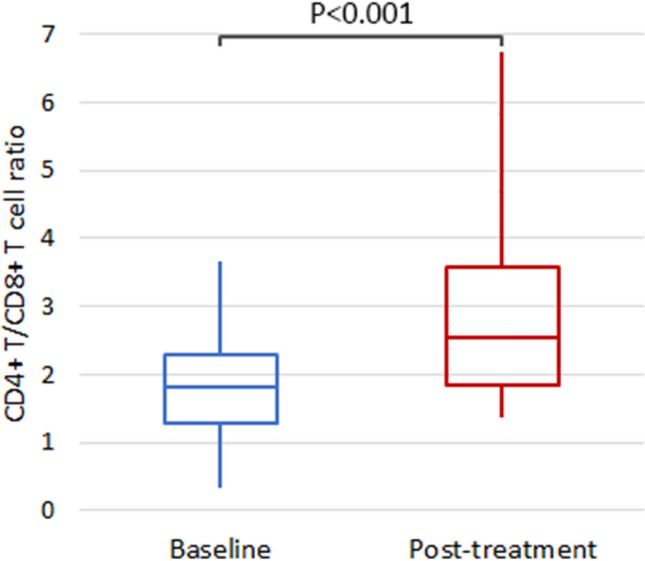

However, those in IMN group who received anti-PD-1 antibody treatment had higher post-treatment CD4+ T cell percentage (52.7% vs 40.1%, P < 0.001) (Table 3) and CD4+ T/CD8+ T ratio (2.98 vs 1.88, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3 and Table 3), while post-treatment CD8+ T cell percentage was lower (19.7% vs 24.0%, P = 0.05) compared to baseline (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

The comparison of post-treatment versus baseline CD4+ T/CD8+ T cell ratio of the IMN group with combination treatment of anti-PD-1 antibodies

Upon introducing immunonutrition, the IMN group shows a statistically significant enhancement in ameliorating the CD4+/CD8+ ratio among those receiving anti-PD-1 treatment (as seen in Table 3,Table S3, and Figure S3, with P-values indicating within-group and between-group differences).

Quantitatively, the difference in the efficacy of these two nutritional methods can be assessed through the delta (Δ) changes in immune cell percentages and ratios. The IMN group demonstrated a significant improvement from baseline. However, no statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups (SEN+ anti-PD-1 vs. IMN+ anti-PD-1) regarding the post-treatment CD4+ T/CD8+ T cell ratio.

The impact of treatment on hospitalization related indicators

We focused on the effect of different treatments in hospital-acquired infection and length of hospital stay. The infection rate was lower in the IMN group compared to the SEN group (0% vs 5.3%, P = 0.816), but no significances. In SEN group, patients who did not receive anti-PD-1 antibody had a higher infection rate than those receiving anti-PD-1 antibody (16.7% vs 0%, P = 0.684). Additionally, the mean length of hospital stay was significantly shorter in the IMN group compared to the SEN group (11.0 days vs 15.8 days, P = 0.002). In SEN group, patients not receiving anti-PD-1 antibody tended to have longer hospital stay than those receiving anti-PD-1 antibody, although not statistically significant (P = 0.166). In the IMN group, patients not receiving anti-PD-1 antibody had significantly longer hospital stay than those receiving anti-PD-1 antibody (P = 0.007). Among patients receiving anti-PD-1, hospital stay was significantly shorter in the IMN group than the SEN group (P = 0.024). Similarly, among patients not receiving anti-PD-1 antibody, hospital stay was markedly shorter in the IMN group (P = 0.012) (as shown in Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, we observed a notable enhancement in immune function among patients receiving immunonutrition support, as evidenced by improved CD4+/CD8+ T cell ratios post-treatment. These findings align with recent studies suggesting that specific nutrients in immunonutrition, such as arginine and omega-3 fatty acids, may activate immune signaling pathways, thereby enhancing the anti-tumor immune response [12, 13]. This enhancement is particularly relevant in the context of immunotherapies targeting the PD-1 pathway, where the efficacy of such treatments is inherently tied to the patient’s immune system’s capability [14].

Further analysis reveals that immunonutrition potentially modulates the immune landscape by improving the CD4+/CD8+ T cell ratios, a critical determinant of a robust anti-tumor response. This modulation is believed to occur through the activation of specific immune signaling pathways, which are crucial for the proliferation and differentiation of T cells [15, 16]. Arginine, for instance, has been shown to play a pivotal role in T cell receptor signaling, while omega-3 fatty acids are known to influence the inflammation response, thereby indirectly supporting the immune system's capacity to combat cancer [17]. Dietary and supplemental amino acids in such conditions have revealed their importance as ‘immunonutrients’ by modulating cellular homeostasis processes and halting malignant progression. l-arginine specifically has attracted interest as an immunonutrient by acting as a nodal regulator of immune responses linked to carcinogenesis processes through its versatile signalling molecule, nitric oxide (NO). The quantum of NO generated directly influences the cytotoxic and cytostatic processes of cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and senescence [18, 19]. Immunonutrition emerges as the more effective method for improving immune function in HNSCC patients, significantly enhancing the CD4+/CD8+ T cell ratio and, by extension, the potential for a more robust immune response to cancer and therapy.

The mechanistic underpinnings of how immunonutrition improves CD4+/CD8+ ratios may be linked to its ability to enhance the overall nutritional status and mitigate the immunosuppressive effects often observed in cancer patients. Enhanced nutritional status has been associated with improved lymphocyte proliferation and the restoration of cytokine profiles, which are essential for effective immune surveillance and response [6, 20]. Although the study’s scope includes an evaluation of the synergistic effects with PD-1 blockade therapies, the foundational benefits of immunonutrition in optimizing immune function provide a compelling argument for its integration into cancer treatment protocols. This suggests that immunonutrition may effectively support the immune system’s ability to leverage PD-1 inhibitors, thereby potentially improving patient outcomes in the treatment of HNSCC. When PD-1 inhibitors are part of the treatment regimen, immunonutrition presents a more advantageous approach, significantly enhancing key immune function indicators, thereby offering a better supportive strategy for optimizing the efficacy of PD-1 blockade therapy in HNSCC patients.

Immunonutrition can reduce hospitalization rates and mortality in cancer patients [6]. This finding suggests that immunonutrition may facilitate a quicker recovery process, enabling earlier discharge. The reduction in the time spent hospitalized is a critical metric, suggesting potential healthcare cost efficiencies, alleviating strain on medical facilities, and diminishing patient risk for hospital-acquired conditions. The examination also revealed disparities in infection occurrences between the two groups. Decreased infection rates signify a bolstered immune defense, paramount for patients recuperating from cancer treatments, as infections can obstruct recovery, prolong hospitalization, or exacerbate health complications.

Particularly, immunonutrition is shown to offer considerable benefits in curtailing hospitalization durations and potentially in minimizing infection rates among patients. These insights underscore the efficacy of specialized nutritional strategies in enhancing patient recuperation and overall treatment efficacy, suggesting that a nuanced approach to nutrition could elevate clinical outcomes for cancer patients. This study need to collect additional cases to make it a larger dataset, or consider conducting a multi-center study.

Conclusion

In this study, we demonstrate that immunonutrition significantly enhances immune function in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), primarily by improving the ratios of CD4+ to CD8+ T cells. These findings underscore the critical importance of targeted nutritional support in strengthening the body’s immune response. Furthermore, they suggest a synergistic potential when immunonutrition is combined with PD-1 blockade therapies. Integrating immunonutrition into cancer treatment protocols may thus provide a dual advantage: directly augmenting immune capabilities while simultaneously enhancing the efficacy of immunotherapies. This study advocates for the incorporation of immunonutritional strategies as a standard component of comprehensive cancer care and highlights the necessity for further research to fully elucidate its benefits across various cancer treatments.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

Xijun Lin, Lanlan Deng, and Xiaoming Huang designed the research. Xijun Lin and Lanlan Deng contributed equally to this work. Faya Liang, Ping Han, Peiliang Lin, and Xiaoming Huang assisted with data acquisition and data analysis. Xijun Lin and Lanlan Deng wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the final version.

Funding

None.

Data availability

The original contributions from this study can be found in the attached document.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xijun Lin and Lanlan Deng contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Döbrossy L. Epidemiology of head and neck cancer: magnitude of the problem. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2005; 24: 9–17. This reference could support the statement about the global challenge of head and neck cancer, highlighting its prevalence and mortality rates. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Arends J, Bachmann P, Baracos V, Barthelemy N, Bertz H, Bozzetti F et al. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin Nutr. 2017; 36(1): 11–48. This could be a source for the discussion on malnutrition's impact on immune function and therapeutic outcomes. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Vidal-Casariego A, Calleja-Fernández A, Villar-Taibo R, Kyriakos G. Efficacy of arginine-enriched enteral formulas in the reduction of surgical complications in head and neck cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr. 2014; 33(6): 951–57. This reference might support the information on the benefits of immunonutrition, emphasizing arginine, omega-3 fatty acids, and nucleotides. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Ma M, Zheng Z, Zeng Z, Li J, Ye X, Kang W. Perioperative enteral immunonutrition support for the immune function and intestinal mucosal barrier in gastric cancer patients undergoing gastrectomy: a prospective randomized controlled study. Nutrients. 2023;15(21):4566. 10.3390/nu15214566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsui R, Sagawa M, Sano A, Sakai M, Hiraoka SI, Tabei I, Imai T, Matsumoto H, Onogawa S, Sonoi N, Nagata S, Ogawa R, Wakiyama S, Miyazaki Y, Kumagai K, Tsutsumi R, Okabayashi T, Uneno Y, Higashibeppu N, Kotani J. Impact of perioperative immunonutrition on postoperative outcomes for patients undergoing head and neck or gastrointestinal cancer surgeries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Surg. 2024;279(3):419–28. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000006116. (Epub 2023 Oct 26). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu K, Zheng X, Wang G, Liu M, Li Y, Yu P, Yang M, Guo N, Ma X, Bu Y, Peng Y, Han C, Yu K, Wang C. Immunonutrition vs standard nutrition for cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis (Part 1). JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2020;44(5):742–67. 10.1002/jpen.1736. (Epub 2019 Nov 11). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yi M, Jiao D, Xu H, Liu Q, Zhao W, Han X, Wu K. Biomarkers for predicting efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Mol Cancer. 2019; 18(1): 129. This could provide background on PD-1 inhibitors and their reliance on the patient’s immune status. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Sorensen D, McCarthy B, Baumgartner S, Demars S. Perioperative immunonutrition in head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2009 119(7): 1358–64. This reference might be used to discuss preliminary evidence on immunonutrition’s impact on immune cells, particularly CD4+ and CD8+ T cell ratios. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Frąk M, Grenda A, Krawczyk J, Milanowski J. Interactions between dietary micronutrients, composition of the microbiome, and efficacy of immunotherapy in cancer patients. Cancers. 2022; 14(3): 560. This could be cited for findings related to the improvement in CD4+/CD8+ T cell ratios within the immunonutrition group. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Martinelli S, Lamminpää E, Dübüş EN, Sarıkaya D, Niccolai E. Synergistic strategies for gastrointestinal cancer care: unveiling the benefits of immunonutrition and microbiota modulation. Nutrients. 2023; 15(2): 345. This hypothetical reference might support the summary statement on the value of integrating nutritional strategies into oncological treatment. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Yang JS, et al. Arginine metabolism: a potential target in pancreatic cancer therapy. Chin Med J. 2021;134(1):28–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Volpato M, Hull MA. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids as adjuvant therapy of colorectal cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2018;37:545–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ran X, Yang K. Inhibitors of the PD-1/PD-L1 axis for the treatment of head and neck cancer: current status and future perspectives. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2017;11:2007–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Efron D, Barbul A. Role of arginine in immunonutrition. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:20–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quak JJ, et al. Effect of perioperative nutrition, with and without arginine supplementation, on nutritional status, immune function, postoperative morbidity, and survival in severely malnourished head and neck cancer patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73(2):323–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calder PC. Marine omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes: Effects, mechanisms and clinical relevance. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta BBA Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2015;1851(4):469–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sindhu R, Supreeth M, Prasad SK, Thanmaya M. Shuttle between arginine and lysine: influence on cancer immunonutrition. Amino Acids. 2023;55(11):1461–73. 10.1007/s00726-023-03327-9. (Epub 2023 Sep 20). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ouyang Z, Chen P, Zhang M, Wu S, Qin Z, Zhou L. Arginine on immune function and post-operative obstructions in colorectal cancer patients: a meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2024;24(1):1089. 10.1186/s12885-024-12858-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alwarawrah Y, Kiernan K, MacIver NJ. Changes in nutritional status impact immune cell metabolism and function. Front Immunol. 2018;9: 337099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prieto I, et al. The role of immunonutritional support in cancer treatment: current evidence. Clin Nutr. 2017;36(6):1457–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions from this study can be found in the attached document.