Abstract

Given the aggressive nature and robust survival capabilities of the alligator gar (Atractosteus spatula), if it was to exist in a new environment as an invasive species, it could cause significant disruption to the invaded ecosystem. Building on the continuity and completeness of the existing draft genome were not optimal, this study has updated a high-quality genome of the alligator gar at the chromosome level, which was assembled using Oxford Nanopore Technology and chromatin interaction mapping (Hi-C) sequencing techniques. In summary, the alligator gar genome in this study was 1.05 Gb in size with a contig N50 of 15.7 Mb and scaffold N50 of 56.8 Mb. We captured 98.26% of assembled bases in 28 pseudochromosomes. The completeness of the final chromosome-level genome reached 96.7%. Meanwhile, a total of 19,103 protein-coding genes were predicted, of which 99.83% could be predicted with functions. Taken together, the present high-quality alligator gar chromosome-level genome provides a valuable resource for exploring the underlying genomic basis to comprehend the functional genomics, chromosome evolution, and population management of this species.

Subject terms: Genome assembly algorithms, Genome evolution

Background & Summary

The alligator gar (Atractosteus spatula, Lacepède 1803) is one of seven extant species of the ancient Lepisosteidae family, which includes two genera: Atractosteus with three species (tropical, Cuban, and alligator gars) and Lepisosteus with four species (spotted, Florida, longnose, and shortnose gars)1. The slowly evolving genome of the gar fish has garnered increasing attention from scientific researchers in recent years. Studies of the spotted gar (Lepisosteus oculatus) genome have revealed the value of holostean genomes in comparative research, offering significant insights into the evolution of vertebrate immunity, development, and the roles of regulatory sequences2. The draft genome of the alligator gar was used to examine the terrestrial transition of vertebrates from aquatic environments3. In recent times, the genome of the longnose gar (Lepisosteus osseus) highlighted the potential of holostean genomes for understanding the evolution of vertebrate repetitive elements and provided a critical reference for comparative genomic studies using ray-finned fish models4.

It is noteworthy that recent reports highlighting the invasion of the alligator gar underscore the urgency of prioritizing its management efforts. Alligator gar is native to northern and central parts of the United States and Mexico5,6. It has been distributed to numerous countries globally through the aquarium industry. Considered invasive in China, Singapore, Indonesia, Turkmenistan, and several other nations, it has been documented invading 47,287 locations across the planet7,8. Initially detected in Baiyun Lake, Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, in February 2019, it subsequently expanded its range to various provinces including Hunan, Guangxi, Shandong, Sichuan, Qinghai, Jiangsu, and Yunnan7. Due to their inherent biological characteristics, alligator gars possess three primary advantages for survival in freshwater ecosystems. Firstly, they exhibit a large body size and possess overlapping ganoid scales. As the largest species within the gar family, typical adult alligator gars reach length of about 2 m (6.5 feet) and weight over 45 kg (100 pounds)9. They also have tough bone-like scales covered by an enamel-like substance, rendering them nearly impenetrable10,11. Secondly, alligator gars display high fecundity and produce toxic eggs. In comparison to the spotted gar and longnose gar, alligator gar laid the greatest number of eggs per gram of body weight12. In addition, their eggs and yolk sacs are extremely toxic to crustaceans and vertebrates, except teleosts13. Lastly, alligator gars are voracious predators that prey on blue crabs, waterfowl, turtles, small mammals, carrion, and other discarded waste around docks and piers14.

Currently, high-quality sequencing technologies offer immense potential in unraveling the genetic basis of biological characteristics for many species at genome-wide levels15,16. Despite the availability of a draft second-generation genome of the alligator gar, it largely limits the study of speciation and chromosome evolution3. In this study, we generated a high contiguity, completeness, and accuracy genome assembly of alligator gar at chromosome level using Oxford Nanopore Technology and Hi-C sequencing techniques. The assembled genome was 1.05 Gb, with a contig N50 of 15.7 Mb, scaffold N50 of 56.8 Mb. The Hi-C sequences were further clustered and ordered into 28 pseudochromosomes(2n = 56, length from 10.2 Mb to 76.3 Mb). A sequence of ~323 Mb was annotated as a repeat element, constituting 30.91% of the genome. We predicted 19,103 protein-coding genes, of which 99.83% were functionally annotated. In summary, the genomic resources presented in this study would deep our understanding of the underlying genomic basis to comprehend the ecology, evolution, and invasiveness of alligator gars.

Methods

Sample collection and ethics statement

A six-month/1-year-old female alligator gar with 2.8 kg in bodyweight and 41.3 cm in body length was collected by Northeast Institute of Geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Jilin Province, China (Supplementary Fig. 1). The Alligator Gar was captured with standard mini-fyke nets (0.6 m × 1.2 m frame, with a 4.6-m-long lead and 3-mm mesh17) and electrofishing in Dehui, Jilin Province, China, and then placed in a live well for further processes. The otolith of alligator gar was picked out to discriminate its age18. All experiments on the alligator gar were approved under the project ID “DLS20220131-001” by Northeast Institute of Geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Nucleic acid extraction, library construction and sequencing

For the Nanopore library, a total of 8–10 µg high-quality genomic DNA was extracted from a muscle sample, and >50 kb DNA molecules were selected with BluePippin (Sage Science, Beverly, MA, USA). A standard library was constructed with the Ligation Sequencing Kit 1D following the Nanopore library construction protocol. ONT long reads were sequenced on the PromethION P48 sequencer (Grandomics, Beijing, China). RNA was extracted from three tissues (blood, muscle, and skin) from the same individual using TRlzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA libraries were reverse transcribed from 200 to 400 bp RNA fragments and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Grandomics, Beijing, China). For short insert size WGS sequencing, we first isolated total genomic DNA from muscle samples (~2 g) using a phenol-chloroform protocol together with ethanol precipitation19 and prepared the DNBSEQ libraries following manufacturer’s instructions. Finally, they were subjected to the DNBSEQ-T1 sequencer (MGI tech, Guangdong, China) for paired end 100 bp sequencing. For Hi-C library construction, freshly collected liver samples (~2 g) were crosslinked with formaldehyde to fix the chromatin conformation, and the crosslinked DNA was digested by the dpnII restriction endonuclease. The Hi-C library with 350 bp insert size was sequenced on a DNBSEQ-T7 sequencer (Grandomics, Beijing, China).

To obtain a high-quality reference genome of the alligator gar, we generated 65.43 Gb raw long reads (60.68 Gb pass long reads, 57.8-fold) using Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) for de novo assembly (Table 1). The average read length of long reads was 18.0 kb and the N50 was 30.5 kb. We also generated 206.46 Gb whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data (196.6-fold) for the genome survey and polishing (Table 1). We generated 8.82 Gb transcriptomic data for genome annotation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of genome assemblies and gene annotations in the alligator gar genome.

| Item | Category | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing data | ONT (Gb) | 65.43 |

| WGS (Gb) | 206.46 | |

| RNA (Gb) | 8.82 | |

| Hi-C (Gb) | 107.81 | |

| Contig | Estimated genome size (Gb) | 1.19 |

| Contigs | 300 | |

| Contig length (Gb) | 1.05 | |

| Maximum length (Mb) | 42.5 | |

| Contig N50 (Mb) | 15.7 | |

| BUSCO (vertebrata) complete (%) | 96.7 | |

| Chromosome | Karyotype | 2n = 56 |

| Number > = 100 bp | 39 | |

| Number > = 5000 bp | 39 | |

| Maximum length (Mb) | 76.3 | |

| Scaffold N50 (Mb) | 56.8 | |

| Anchored pseudochromosomes (%) | 98.26 | |

| GC content (%) | 40.3 | |

| BUSCO (vertebrata) complete (%) | 96.7 | |

| Annotation | Repeat sequences (%) | 30.91 |

| Number of protein-coding genes | 19,103 | |

| Number of functional annotated genes | 19,070 | |

| Average gene length (bp) | 22,120.55 | |

| Average exon length (bp) | 166.70 | |

| Average intron length (bp) | 2231.85 | |

| Average exon per gene | 10.15 |

Genome size estimation and de novo assembly

Before the de novo genome assembly, we performed a genome survey to estimate the genome size using DNBSEQ short reads data by KmerFreq v1.020 with a kmer size of 17. The de novo genome assembly was performed by NextDenovo (v2.5.0; https://github.com/Nextomics/NextDenovo) with default parameters. We used NextCorrect and NextGraph, two core modules in NextDenovo, to process the raw Nanopore long read correction for consensus sequence extraction and initial assembly. We then improved the single-base accuracy of the draft genome assembly by the NextPolish v1.4.0 software21 using both ONT long-reads and DNBSEQ short reads for six times. For further chromosomal-level genome assembly, Hi-C reads were aligned to the polished genome assembly using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA, v0.7.17)22. Juicer v1.523 was used for Hi-C data quality control, and 3d-DNA pipeline v19071624 was applied to concatenate the scaffolds to the chromosome-level genome. Juicer Box v1.11.0825 was used for final manual correction.

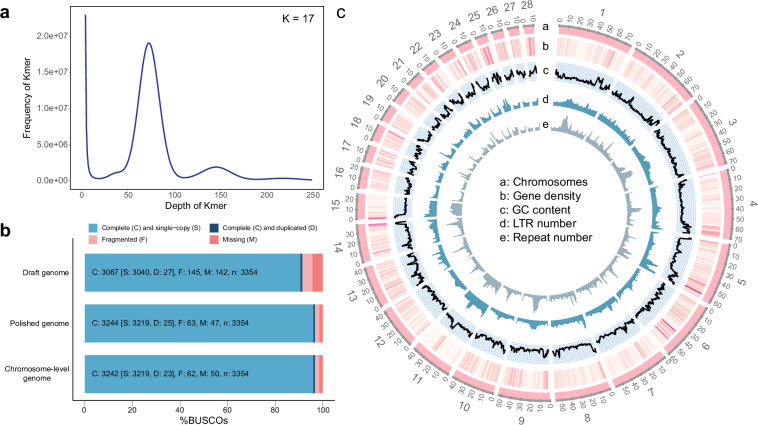

The genome size was 1.19 Gb, as estimated by 17-kmer frequency (Fig. 1a). A total of 107.81 Gb Hi-C reads were generated for concatenating primary contigs into a chromosome-level genome assembly. We then anchored scaffolds to a cluster map, capturing 98.26% of assembled bases in 28 pseudochromosomes (2n = 56, length from 10.2 Mb to 76.3 Mb, Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2), which is consistent with the karyotype study of Echelle et al.26. Other 11 scaffolds had a total length of 18.2 Mb (1.74%, length from 5 kb to 5.7 Mb). In summary, the alligator gar genome in this study was 1.05 Gb in length with a contig N50 of 15.7 Mb and scaffold N50 of 56.8 Mb. The completeness of the final chromosome-level genome reached 96.7% (96% complete and in single copy) by BUSCO analysis (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Genome assembly of the alligator gar. (a) K-mer frequency distribution at k-mer size of 17. K-mer refered to an artificial sequence division of K nucleotides. The peak depth was 73X. The total number of 17-mer present in this subset was 86,674,739,928. (b) BUSCO scores of the draft, polished, and final chromosome-level genome. (c) General view of the alligator gar genome in nonoverlapping 500 kb windows: (a) circular map of 28 chromosomes. (b) heat map of gene density. The darker the colour, the higher the density. (c) GC content. (d) Long Terminal Repeat (LTR) number. (e) Repeat number.

Table 2.

Statistical results of the 28 pseudochromosomes of the alligator gar genome.

| Chromosome | Length (bp) | % of assembly |

|---|---|---|

| chr1 | 76,333,234 | 7.30 |

| chr2 | 75,211,232 | 7.20 |

| chr3 | 71,867,422 | 6.88 |

| chr4 | 71,165,372 | 6.81 |

| chr5 | 63,528,295 | 6.08 |

| chr6 | 60,150,324 | 5.75 |

| chr7 | 58,846,959 | 5.63 |

| chr8 | 56,827,445 | 5.44 |

| chr9 | 53,354,325 | 5.10 |

| chr10 | 44,302,670 | 4.24 |

| chr11 | 43,870,655 | 4.20 |

| chr12 | 42,966,659 | 4.11 |

| chr13 | 42,835,809 | 4.10 |

| chr14 | 39,015,621 | 3.73 |

| chr15 | 26,510,161 | 2.54 |

| chr16 | 22,394,860 | 2.14 |

| chr17 | 17,817,902 | 1.70 |

| chr18 | 17,784,509 | 1.70 |

| chr19 | 17,576,594 | 1.68 |

| chr20 | 16,855,600 | 1.61 |

| chr21 | 16,011,720 | 1.53 |

| chr22 | 15,754,421 | 1.51 |

| chr23 | 15,740,989 | 1.51 |

| chr24 | 15,242,874 | 1.46 |

| chr25 | 12,196,117 | 1.17 |

| chr26 | 11,750,222 | 1.12 |

| chr27 | 10,860,406 | 1.04 |

| chr28 | 10,238,547 | 0.98 |

| Total | 1,027,010,944 | 98.26 |

Combined with third-generation ONT long reads and large-scale Hi-C data, the chromosome-level genomes assembled in this study exhibited significant improvements in the following aspects compared with the previously released assembly (GCA_016984175.1, Supplementary Table 1)3. (1) Our assembly demonstrated a significant reduction in the number of scaffolds from 81,747 to 39. (2) Our assembly showed remarkable enhancements of 785-fold and 41-fold in N50 values of the contig and scaffold over those of the previously released assemblies, respectively. (3) The gap region (Ns) in the previously released assemblies (5.967%) has been significantly reduced by a factor of 459 in our assembly genome (0.013%). (4) Our assembly had a notable increase of 2.1% in the BUSCO score, indicating a higher integrity in our assembly. These findings demonstrated the reliability and advanced nature of our chromosome-level genetic assembly. Furthermore, the combination of homology-based protein alignment, de novo predictions, and transcriptomic mapping in our study showed a higher PCGs number than that of the previously published alligator gar genome (GCA_016984175.1, 18,839 PCGs)3, enhancing contiguity and integrity of our assembled genome allowed for more precise gene prediction.

Genome annotation

Prior to gene prediction and annotation, genome repetitive elements were annotated by integrating homology-based and de novo strategies. For the de novo method, RepeatModeler v2.027 and LTR_retriever28 were used to annotate repeat elements which were then added to the known repeat database REPBASE v21.0129. Then, the genome was aligned to the REPBASE using RepeatMasker v4.0.530, RepeatProteinMask, and Trf v4.07b31 at both DNA and protein levels. Finally, we obtained a nonredundant repeat set. The gene density, GC content, repeat number, and LTR number of 28 chromosomes were further analyzed in nonoverlapping 500 kb windows using CIRCOS v0.69-832.

After masking the repeat elements in the genome, three strategies were used for protein-coding gene prediction. Firstly, for the de novo strategy, we ran the prediction using Augustus v3.0.333. Secondly, for the transcriptome-based strategy, transcripts were assembled using StringTie v1.3.3b34 based on RNA-seq data. Finally, for the homology-based strategy, protein sequences of the spotted gar (LepOcu1, GeneBank ID: GCF_000242695.1)2, coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae, LatCha1, GeneBank ID: GCF_000225785.1)35, bichir (Polypterus senegalus, ASM1683550v1, GeneBank ID: GCF_016835505.1)3, and paddlefish (Polyodon spathula, ASM1765450v1, GeneBank ID: GCF_017654505.1)36 were mapped to the alligator gar genome using TBlastn program v2.9.037. GeneWise v2.4.138 was used to predict the potential gene structure with an E-value cutoff of 1e-5 (Supplementary Table 2). The final protein-coding gene set was predicted by combining the results from these three strategies using the MAKER pipeline v3.01.0339. For functional annotations, this gene set was searched in five publicly available databases including Swiss-Prot, TrEMBL, InterProScan v5.52-86.040, GO terms, and KEGG using BLAST v2.2.2637 (e-value cutoff of 1e-5). For ncRNA prediction, miRNA and snRNA were identified by searching the Rfam database (Release 12.0)41. The tRNA genes were predicted with tRNAscan-SE v1.3.142, and the rRNA genes were identified by aligning human rRNA using BLAST.

Combining the de novo and homology-based predictions, we found 323 Mb repeat elements, accounting for 30.91% of the alligator gar genome (Supplementary Table 2). The predominant repeat types were long terminal repeats (LTR, 11.73%), long interspersed elements (LINEs, 5.69%), and DNA transposons (4.96%) (Table 3, Supplementary Table 3, and Supplementary Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Statistics of identified repeat elements by De novo method.

| Type | Length (bp) | % of genome |

|---|---|---|

| DNA | 42,430,960 | 4.06 |

| LINE | 59,460,124 | 5.69 |

| SINE | 27,152,619 | 2.60 |

| LTR | 122,556,136 | 11.73 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0.00 |

| Total | 55,151,754 | 5.28 |

We predicted 19,103 protein-coding genes (PCGs) through the combination of homology-based protein alignment, de novo predictions, and transcriptomic mapping. The average lengths of PCGs, exons, and introns were 2,120.55 bp, 166.71 bp, and 2231.85 bp, respectively (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Of these predicted PCGs, 19,070 (99.83%) were annotated in at least one related functional assignment (Table 4 and Fig. 3). We further plotted the distribution of gene density, GC content, and repeat density across 28 pseudochromosomes (Fig. 1c). We also predicted 22,559 noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs), including 191 microRNAs, 10,015 transfer RNAs (tRNAs), 9524 ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), and 2829 small nuclear RNAs (snRNA) (Table 5).

Fig. 2.

Comparisons of CDS length, mRNA length, intron length, and exon length among five species (Atractosteus spatula, Lepisosteus oculatus, Polypterus senegalus, Polyodon spathula, and Latimeria chalumnae).

Table 4.

Statistics on functional annotation of the alligator gar gene set.

| Values | Total | Swissprot | KEGG | TrEMBL | Interpro | GO | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 19,103 | 18,598 | 17,541 | 14,125 | 18,971 | 14,009 | 19,070 |

| Percentage | 100% | 97.36% | 91.82% | 73.94% | 99.31% | 73.33% | 99.83% |

Fig. 3.

Venn diagram representing the functional annotation of the alligator ger gene set.

Table 5.

Statistics of non-coding RNA annotation.

| Type | number | Average length (bp) | Total length (bp) | % of genome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | 191 | 82.32 | 15,723 | 0.00150 | |

| tRNA | 10,015 | 77.00 | 771,110 | 0.07379 | |

| rRNA | rRNA | 4762 | 89.57 | 426,516 | 0.04081 |

| 18S | 86 | 492.72 | 42,374 | 0.00406 | |

| 28S | 890 | 174.61 | 155,400 | 0.01487 | |

| 5.8S | 19 | 148.63 | 2,824 | 0.00027 | |

| 5S | 3767 | 59.97 | 225,918 | 0.02162 | |

| snRNA | snRNA | 1437 | 161.30 | 231,782 | 0.02218 |

| CD-box | 155 | 143.37 | 22,223 | 0.00213 | |

| HACA-box | 46 | 161.63 | 7,435 | 0.00071 | |

| splicing | 1191 | 166.38 | 198,157 | 0.01896 |

Data Records

The raw sequencing data for this study are deposited in the NCBI under BioProject ID: PRJNA116104143. Illumina, transcriptome, and PacBio sequencing data are available under the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with the accession number SRP53704644. The assembled genome has been deposited in the GenBank database under the accession number GCA_043380575.145. Additionally, assembled genome and annotations can be downloaded from Figshare46 under 10.6084/m9.figshare.27193392.

All assemblies and raw sequencing data generated of this study also have been deposited CNGB Sequence Archive (CNSA)47 (https://db.cngb.org/cnsa/) of the China National GeneBank DataBase (CNGBdb)48 with accession number CNP0003816.

Technical Validation

Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) v3.1.049 was used to evaluate the completeness of the draft, polished, and final chromosome-level genomes in the genome mode (-m genome) with 3354 core vertebrata gene sets (vertebrata_odb10). The completeness of the final chromosome-level genome reached 96.7% (96% complete and in single copy) by BUSCO analysis. Gene set completeness was also evaluated with the vertebrata_odb10 database using the protein mode (-m protein) of BUSCO. BUSCO analysis showed 94.5% completed BUSCO scores for predicted PCGs, with 2.5% fragmented and 3.0% missing of core vertebrate genes. Furthermore, the total size of the assembled genome is similar to that estimated by jellyfish.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFF1300900), National Natural Science Foundation of China (42101071), and International Wetlands Research League, Alliance of International Science Organizations (ANSO-PA-2020-14).

Author contributions

Y.Y. conceived and designed the project. P.Q. and X.T. collected the samples. Q.Y. and H.W. performed the DNA and RNA extraction, library preparation, and genome sequencing. Q.W. Q.Y., X.D. and H.C. performed the bioinformatics analysis and visualized the results. Q.W. wrote the manuscript. P.Q., X.T. and Y.Y. revised and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of manuscript.

Code availability

No specific script was used in this work. The codes and pipelines used in data processing were all executed according to the manual and protocols of the corresponding bioinformatics software. The specific versions of software have been described in Methods.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Qing Wang, Qianqian Yu.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41597-024-04256-2.

References

- 1.Wright, J. J., David, S. R. & Near, T. J. Gene trees, species trees, and morphology converge on a similar phylogeny of living gars (Actinopterygii: Holostei: Lepisosteidae), an ancient clade of ray-finned fishes. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution63, 848–856 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braasch, I. et al. The spotted gar genome illuminates vertebrate evolution and facilitates human-teleost comparisons. Nature genetics48, 427–437 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bi, X. et al. Tracing the genetic footprints of vertebrate landing in non-teleost ray-finned fishes. Cell184, 1377–1391. e1314 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mallik, R. et al. A chromosome-level genome assembly of longnose gar, Lepisosteus osseus. G3 (Bethesda)13, 10.1093/g3journal/jkad095 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Raz-Guzmán, A., Huidobro, L. & Padilla, V. An updated checklist and characterisation of the ichthyofauna (Elasmobranchii and Actinopterygii) of the Laguna de Tamiahua, Veracruz, Mexico. Acta Ichthyologica et Piscatoria48 (2018).

- 6.Warren, M. L. Jr et al. Diversity, distribution, and conservation status of the native freshwater fishes of the southern United States. Fisheries25, 7–31 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li, M. & Zhang, H. Predicting the Distribution of the Invasive Species Atractosteus spatula, the Alligator Gar, in China. Water15, 10.3390/w15244291 (2023).

- 8.Kumar, A. B., Raj, S., Arjun, C., Katwate, U. & Raghavan, R. Jurassic invaders: flood-associated occurrence of arapaima and alligator gar in the rivers of Kerala. Curr Sci116, 1628–1630 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Region, S., Sager, C. & Routledge, D. Lake Texoma Fisheries Management Plan.

- 10.Sherman, V. R., Yaraghi, N. A., Kisailus, D. & Meyers, M. A. Microstructural and geometric influences in the protective scales of Atractosteus spatula. Journal of the Royal Society Interface13, 20160595 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang, W. et al. Structure and fracture resistance of alligator gar (Atractosteus spatula) armored fish scales. Acta biomaterialia9, 5876–5889 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiBenedetto, K. C. Life history characteristics of alligator gar, Atractosteus spatual, in the Bayou DuLarge area of southcentral Louisiana (2009).

- 13.Goodger, W. P. & Burns, T. A. The cardiotoxic effects of alligator gar (Lepisosteus spatula) roe on the isolated turtle heart. Toxicon18, 489–494 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Connell, M. T., Shepherd, T. D., O’Connell, A. M. & Myers, R. A. Long-term declines in two apex predators, bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas) and alligator gar (Atractosteus spatula), in lake pontchartrain, an oligohaline estuary in southeastern Louisiana. Estuaries and Coasts30, 567–574 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lan, T. et al. The Chromosome-Scale Genome of the Raccoon Dog: Insights into the Genomic Basis of Invasiveness.

- 16.Li, H. et al. Chromosome-level Genome of the Muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus). Genome biology and evolution14, evac138 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eggleton, M. A., Jackson, J. R. & Lubinski, B. J. Comparison of Gears for Sampling Littoral‐Zone Fishes in Floodplain Lakes of the Lower White River, Arkansas. North American Journal of Fisheries Management30, 928–939, 10.1577/m09-127.1 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith, N. G. et al. Hydrologic Correlates of Reproductive Success in the Alligator Gar. North American Journal of Fisheries Management40, 595–606, 10.1002/nafm.10442 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E. F. & Maniatis, T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. (Cold spring harbor laboratory press, 1989).

- 20.Liu, B. et al. Estimation of genomic characteristics by analyzing k-mer frequency in de novo genome projects. arXiv preprint arXiv:1308.2012 (2013).

- 21.Hu, J., Fan, J., Sun, Z. & Liu, S. NextPolish: a fast and efficient genome polishing tool for long-read assembly. Bioinformatics (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics26, 589–595 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell systems3, 95–98 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. 356(6333), 92–95, 10.1126/science.aal3327 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Durand, N. C. et al. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell systems3, 99–101 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Echelle, A. A. & Grande, L. Lepisosteidae: gars. Freshwater fishes of North America1, 243–278 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences117, 9451–9457 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ou, S. & Jiang, N. LTR_retriever: a highly accurate and sensitive program for identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Plant physiology176, 1410–1422 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bao, W., Kojima, K. K. & Kohany, O. Repbase Update, a database of repetitive elements in eukaryotic genomes. Mobile Dna6, 1–6 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen, N. Using Repeat Masker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Current protocols in bioinformatics5, 4.10. 11–14.10. 14 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benson, G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic acids research27, 573–580 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krzywinski, M. et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome research19, 1639–1645 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stanke, M., Steinkamp, R., Waack, S. & Morgenstern, B. AUGUSTUS: a web server for gene finding in eukaryotes. Nucleic acids research32, W309–W312 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nature biotechnology33, 290–295 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chris, T. et al. The African coelacanth genome provides insights into tetrapod evolution. Nature496(7445), 311–316, 10.1038/nature12027 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Cheng, P. et al. The American Paddlefish Genome Provides Novel Insights into Chromosomal Evolution and Bone Mineralization in Early Vertebrates. Abstract Molecular Biology and Evolution38(4), 1595–1607, 10.1093/molbev/msaa326 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Mount, D. W. Using the basic local alignment search tool (BLAST). Cold Spring Harbor Protocols2007, pdb. top17 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Birney, E., Clamp, M. & Durbin, R. GeneWise and genomewise. Genome research14, 988–995 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campbell, M. S., Holt, C., Moore, B. & Yandell, M. Genome annotation and curation using MAKER and MAKER-P. Current protocols in bioinformatics48, 4.11. 11–14.11. 39 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones, P. et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics30, 1236–1240 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Griffiths-Jones, S., Bateman, A., Marshall, M., Khanna, A. & Eddy, S. R. Rfam: an RNA family database. Nucleic acids research31, 439–441 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lowe, T. M. & Eddy, S. R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic acids research25, 955–964 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.NCBI Bioprojecthttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1161041 (2024).

- 44.NCBI Sequence Read Archivehttps://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP537046 (2024).

- 45.NCBI GenBankhttps://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_043380575.1 (2024).

- 46.Wang, Q. Y. Yuxiang. Chromosome-scale genome assembly and gene annotation of the Alligator Gar (Atractosteus spatula). figshare10.6084/m9.figshare.27193392.v1 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Guo, X. et al. CNSA: a data repository for archiving omics data. Database2020 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Chen, F. Z. et al. CNGBdb: china national genebank database. Yi Chuan= Hereditas42, 799–809 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics31, 3210–3212 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- NCBI Bioprojecthttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1161041 (2024).

- NCBI Sequence Read Archivehttps://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP537046 (2024).

- NCBI GenBankhttps://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_043380575.1 (2024).

- Wang, Q. Y. Yuxiang. Chromosome-scale genome assembly and gene annotation of the Alligator Gar (Atractosteus spatula). figshare10.6084/m9.figshare.27193392.v1 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No specific script was used in this work. The codes and pipelines used in data processing were all executed according to the manual and protocols of the corresponding bioinformatics software. The specific versions of software have been described in Methods.