Comorbid epilepsy in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is common and is associated with worse disease course and higher mortality.1 Therefore, finding treatments that can target both disease processes may slow the progression of cognitive decline and seizure-related morbidity. Memantine is a noncompetitive NMDA receptor (NMDA-R) antagonist approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe AD.2 However, its role in epilepsy is not well-established. Here, we describe a case of a person with AD who developed first-time unprovoked recurrent focal impaired awareness seizures a few weeks after discontinuing memantine. To our knowledge, there are no previous reports of seizure occurrence in AD in the setting of discontinuing memantine.

An 85-year-old male with advanced AD presented with two focal seizures with impaired awareness a few weeks apart. Seizures were characterized by staring, head bobbing, shaking of outstretched arms, and eye fluttering with alteration of awareness.

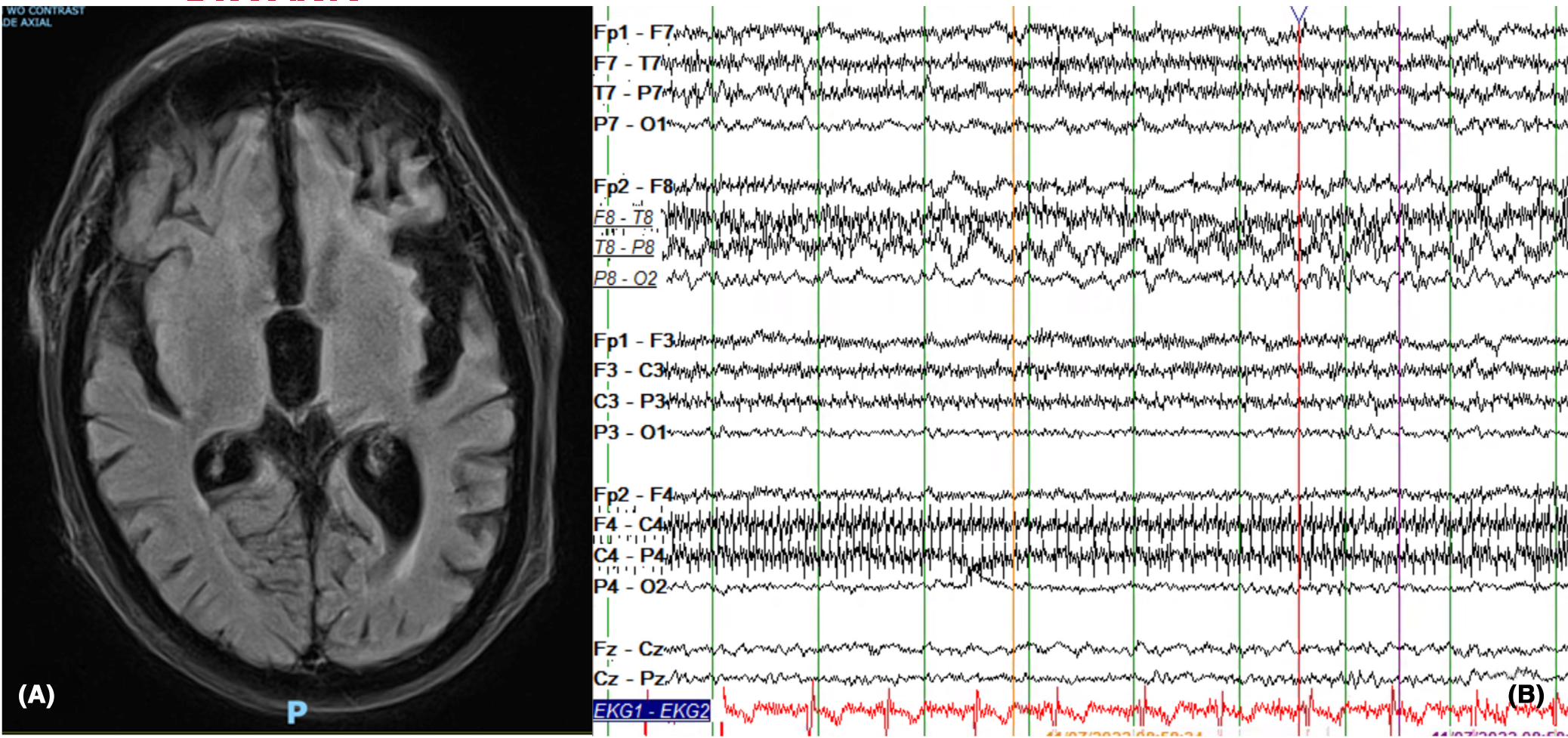

He had no history of seizures, no seizure risk factors except AD, and was not on any antiseizure medications (ASM). On further inquiry, it was discovered that he had been taking memantine 10 mg twice daily for 20 years and had abruptly self-discontinued it a few weeks prior to the first seizure. Discontinuation syndrome may occur with abrupt memantine discontinuation characterized by cognitive and psychiatric disturbances.3 However, he did not have symptoms of discontinuation syndrome. His two unprovoked seizures were thought to be consistent with epilepsy. MRI brain showed global atrophy but was nonlesional (Figure 1A). Electroencephalogram (EEG) showed rare runs (Figure 1B) of right-sided temporal intermittent rhythmic delta activity (TIRDA). Memantine’s discontinuation as a suspected factor leading to seizures and its off-label retrial for seizure control was discussed with the patient’s family. However, family preferred an FDA-approved ASM and opted for lamotrigine. He was started on lamotrigine, which was uptitrated for optimal seizure control.

FIGURE 1.

MRI brain and EEG findings. (A) The MRI brain (axial flair) shows global parenchymal volume loss. It shows no acute intracranial abnormalities nor epileptogenic focus. (B) Right temporal Intermittent rhythmic delta activity (TIRDA) is shown in this figure on EEG. The EEG shown is in longitudinal bipolar Montage (HFF: 70 hertz, LFF: 1 Hz).

Memantine works by preventing neurotoxicity of excess glutamate activity in hippocampus and other brain regions affected by AD.2 Memantine also blocks excessive calcium entry during increased activation of NMDA-R and, thus, is considered neuroprotective in AD.4 The role of NMDA-R involvement in neuronal hyperexcitability and epileptogenesis is uncontroversial. Endogenous activation of NMDA-R of pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus is seen in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (MTLE). In MTLE with hippocampal sclerosis, an increase in NMDA-R NR2 subunit mRNA levels is observed.5 In tuberous sclerosis, increased levels of NMDA NR2B and 2D subunit mRNA are present.6 The anti-inflammatory effects of memantine have been hypothesized to contribute to therapeutic benefit in AD.7 Since inflammation may play a role in certain epilepsies, this effect of memantine may also contribute to its antiseizure benefits.

While some ASMs including felbamate, valproate, and carbamazepine have targeted the NMDA-R for epilepsy management, investigations of memantine’s antiseizure properties have been mostly limited to animal models and a few clinical studies of epileptic encephalopathies.8–10 Felbamate targets NMDA NR2B subunit and is FDA-approved for focal-onset seizures and Lennox–Gastaut syndrome.8 In animal models, Valproate has been shown to affect NR2A and NR2B receptor subunit expression in the neocortex9 and carbamazepine has been shown to target NMDA-induced cytoplasmic vacuolization in hippocampus.10

Despite being a noncompetitive NMDA-R antagonist, there is limited literature indicating role of memantine as an ASM in clinical practice. Randomized controlled trials are lacking and it is not FDA-approved for epilepsy. In animal models, there is evidence that it reduces hyperexcitability and seizures at low doses.11 Memantine has been shown to reduce the duration of convulsions by 37% in pentylenetetrazole-induced seizures in rats.12

A few clinical studies have also reported its utility. In a 20-month-old with refractory spasms secondary to GRIN2B epileptic encephalopathy, memantine was added after failure of multiple ASMs, resulting in reduction in seizure frequency by ~80%.13 In a randomized controlled trial of children with epileptic encephalopathy, statistically significant EEG and clinical improvement was observed in people receiving treatment with memantine compared to placebo.14

In summary, we present a patient with AD who experienced first-time unprovoked, recurrent seizures a few weeks after discontinuing memantine after using it for 20 years. Given no prior seizures, inciting factors, nor risk factors and a nonlesional MRI, we speculate that memantine was likely offering him antiseizure protective effect.

This case highlights the potential role of memantine in controlling seizures, especially in AD, where it may offer dual benefits. However, larger randomized controlled trials are needed to validate our findings and to better elucidate memantine’s efficacy for epilepsy in AD.

Supplementary Material

Funding information

American Epilepsy Society, Grant/Award Number: 1067206; Alzheimer’s Association, Grant/Award Number: AACSFD-22-974008

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

H Rayala reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. HA El-haija reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. J Kapur reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. I Zawar reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zawar I, Quigg M, Manning C, Kapur J. Seizures in dementia are associated with worse clinical outcomes, higher mortality and shorter lifespans (P3–1.001). Neurology. 2023;100(17 Supplement 2):1774. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000202113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McShane R, Westby MJ, Roberts E, Minakaran N, Schneider L, Farrimond LE, et al. Memantine for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3(3):1–446. 10.1002/14651858.CD003154.PUB6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwak YT, Han I-W, Suk S-H, Koo M-S. Two cases of discontinuation syndrome following cessation of memantine. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2009;9:203–5. 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2009.00519.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson DM, Keating GM. Memantine: a review of its use in Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs. 2006;66(11):1515–34. 10.2165/00003495-200666110-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathern GW, Pretorius JK, Kornblum HI, Mendoza D, Lozada A, Leite JP, et al. Human hippocampal AMPA and NMDA mRNA levels in temporal lobe epilepsy patients. Brain. 1997;120:1937–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White R, Hua Y, Scheithauer B, Lynch DR, Petri Henske E, Crino PB. Selective alterations in glutamate and GABA receptor subunit mRNA expression in dysplastic neurons and Giant cells of cortical tubers. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:67–78. 10.1002/1531-8249(200101)49:1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lowinus T, Bose T, Busse S, Busse M, Reinhold D, Schraven B, et al. Immunomodulation by memantine in therapy of Alzheimer’s disease is mediated through inhibition of Kv1.3 channels and T cell responsiveness. Oncotarget. 2016;7(33):53797–807. 10.18632/ONCOTARGET.10777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.French J, Smith M, Faught E, Brown L. Practice advisory: the use of felbamate in the treatment of patients with intractable epilepsy: report of the quality standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 1999;52(8):1540–5. 10.1212/WNL.52.8.1540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roullet FI, Wollaston L, Decatanzaro D, Foster JA. Behavioral and molecular changes in the mouse in response to prenatal exposure to the anti-epileptic drug valproic acid. Neuroscience. 2010;170(2):514–22. 10.1016/J.NEUROSCIENCE.2010.06.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bown CD, Wang JF, Young LT. Attenuation of N-m ethyl-D-aspartate-mediated cytoplasmic vacuolization in primary rat hippocampal neurons by mood stabilizers. Neuroscience. 2003;117(4):949–55. 10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00743-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zawar I, Kapur J. Does Alzheimer’s disease with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy represent a distinct disease subtype? Alzheimers Dement. 2023;17:2697–706. 10.1002/ALZ.12943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaitsev AV, Kim KK, Vasilev DS, Lukomskaya NY, Lavrentyeva VV, Tumanova NL, et al. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor channel blockers prevent pentylenetetrazole-induced convulsions and morphological changes in rat brain neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2015;93(3):454–65. 10.1002/JNR.23500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chidambaram S, Manokaran RK. Favorable response to memantine in a child with GRIN2B epileptic encephalopathy. Neuropediatrics. 2022;53(4):287–90. 10.1055/S-0041-1739130/ID/JR212893SC-10/BIB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiller K, Berrahmoune S, Dassi C, Corriveau I, Ayash TA, Osterman B, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled crossover trial of memantine in children with epileptic encephalopathy. Brain. 2023;146(3):873–9. 10.1093/BRAIN/AWAC380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.