Abstract

We have recently shown by using a recombinant Salmonella typhimurium PhoPc strain in mice the feasibility of using a Salmonella-based vaccine to prevent infection by the genital human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16). Here, we compare the HPV16-specific antibody responses elicited by nasal immunization with recombinant S. typhimurium strains harboring attenuations that, in contrast to PhoPc, are suitable for human use. For this purpose, χ4989 (Δcya Δcrp) and χ4990 [Δcya Δ(crp-cdt)] were constructed in the ATCC 14028 genetic background, and comparison was made with the isogenic PhoPc and PhoP− strains. Although the levels of expression of HPV16 virus-like particle (VLP) were similar in all strains, only PhoPc HPV16 induced sustained specific antibody responses after nasal immunization, while all strains induced high antibody responses with a single nasal immunization when an unrelated viral hepatitis B core antigen was expressed. The level of the specific antibody responses induced did not correlate with the number of recombinant bacteria surviving in various organs 2 weeks after immunization. Our data suggest that the immunogenicity of attenuated Salmonella vaccine strains does not correlate with either the number of persisting bacteria after immunization or the levels of in vitro expression of the antigen carried. Rather, the PhoPc phenotype appears to provide the unique ability in Salmonella to induce immune responses against HPV16 VLPs.

Recombinant avirulent Salmonella vaccines that are attenuated, yet invasive, are effective vehicles for delivering heterologous antigens to the mucosal and systemic immune systems (7). The potential advantage of such a bacterial vaccine vector is its ability to replicate and express heterologous antigen in vivo. Salmonella species cause typhoid fever in their natural hosts after infection via the oral route. They invade the host by crossing the gut mucosa and colonize the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), as well as the spleen and liver. Deletion of various genes can render Salmonella avirulent while preserving different degrees of invasiveness and thus immunogenicity (7). Several attenuations have been constructed, including nutritional auxotrophs impaired in their pathways for biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids (aro mutants [2, 11, 18a, 34]), strains harboring deletions in the adenylate cyclase (cya) gene and cyclic 3′,5′-AMP receptor protein (crp) genes that are required for the transcription of many genes involved in catabolite transport and breakdown (9), as well as mutants with mutation in the phoP genetic locus (15), a two-component regulatory system (phoP-phoQ) that controls the expression of genes essential for Salmonella virulence (15b, 23) and survival within macrophages (13, 14). Salmonella typhimurium causes a typhoid-like disease in mice and has been used extensively to generate attenuations which can be evaluated for their safety and immunogenicity in the murine model.

We have shown that vaccination with attenuated salmonellae can lead to specific antibody responses in the genital tract of mice (19, 31, 32) and at least one human female volunteer (25). This suggests that Salmonella-based vaccines could be used to control infection by human genital pathogens. The high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) types, most commonly type 16 (HPV16), are etiologically linked to over 90% of cervical cancers (3). Cervical cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in women worldwide, encouraging the development of a prophylactic vaccine to prevent genital infection by these viruses. Recently, we have demonstrated that intranasal immunization of mice with live recombinant S. typhimurium PhoPc bacteria expressing HPV16 virus-like particles (VLPs) resulted in HPV16-specific conformational and neutralizing immunoglobulin A (IgA) and IgG in genital secretions (26). However the PhoPc strain contains a point mutation in the phoQ gene (15a, 16, 23a) and can revert at high frequency (24). Therefore, we decided to evaluate the HPV16-specific antibody responses elicited by S. typhimurium strains harboring attenuations (PhoP− and Δcya Δcrp/cdt), which are more suitable for a human vaccine (Ty800 [18] and χ4632 [25, 35]). To avoid bias due to the different genetic background (SR-11) of the existing Δcya Δcrp strains (9), new isogenic strains were constructed.

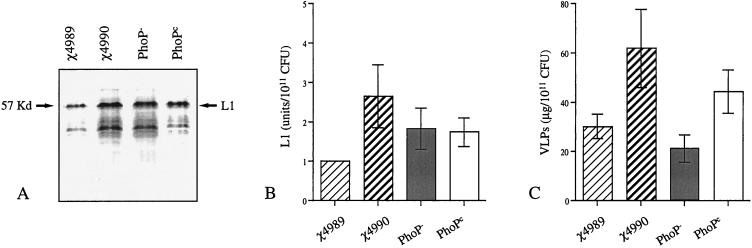

Expression of HPV16 L1 and HPV16 VLPs in the four isogenic strains.

χ4989 (Δcya Δcrp) and χ4990 [Δcya Δ(crp-cdt)] were constructed in the ATCC 14028 wild-type strain as the recipient by methods described by Zhang et al. (41). Plasmid pFS14nsdHPV16-L1 (26) was electroporated (29) into the four S. typhimurium isogenic strains: i.e., the PhoPc (CS022 [24]) and PhoP− (CS015 [22]) strains and χ4989 and χ4990 (this paper). Western blot analysis of bacterial lysates revealed only minor differences in the levels of HPV16 L1 expression (57-kDa band in Fig. 1A) among the different strains examined. Densitometric analysis of the Western blot bands obtained from five different preparations of each recombinant strain are shown in Fig. 1B. The maximal difference observed in HPV16 L1 expression was 2.5-fold between χ4990 and χ4989. We were not able to detect HPV16 L1 in the supernatant of Salmonella cultures, suggesting that none of these strains secreted the HPV16 VLP antigen. We have previously shown that the anti-HPV16 L1 antibodies measured with our enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) are conformational and only recognize assembled HPV16 VLPs (26). It was therefore important to establish whether, despite similar levels of HPV16 L1 expression, the assembly of VLPs could differ between the recombinant strains. For all Salmonella strains, HPV16 VLPs could be extracted by sonication of the bacteria, suggesting that they were not located in inclusion bodies. To determine the amount of VLPs assembled in Salmonella, we developed a sandwich ELISA by using two monoclonal antibodies that recognize conformational epitopes on HPV16 VLPs (H16.E70 and H16.V5; kindly provided by N. D. Christensen, Hershey, Pa. [6]). The amounts of VLPs produced in preparations of the different recombinant strains were determined by using VLPs produced in insect cells as standards (21, 26), but only minor differences were measured (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Expression of HPV16 L1 and VLP production in the four recombinant isogenic Salmonella strains. Salmonellae were grown overnight at 37°C and lysed by boiling in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) loading buffer containing 5% SDS. Bacterial lysate equivalent to 3 × 107 CFU was separated by SDS-PAGE, and an immunoblot with an anti-HPV16 L1 monoclonal antibody (MAb), CAMVIR-1, is shown (A). The 57-kDa protein band identified as L1 is indicated by an arrow. Scanning of the L1 protein bands obtained in five independent experiments was performed by using NIH Image software. The results are shown as the means of the pixel densities of the L1 protein bands expressed in units per 1011 CFU (B). VLP production was assessed in overnight cultures. After sonication, the bacteria were centrifuged to discard the debris, and the supernatants were analyzed for the presence of HPV16 VLPs. The amounts of VLPs were determined by sandwich ELISA. Microtiter plates were coated with an anti-HPV16 VLP conformational MAb, H16.E70, another biotinylated anti-HPV16 VLP conformational MAb, H16.V5, was used as the secondary antibody, and HPV16 VLPs produced in insect cells (26) were used as a standard. The results are shown as the means of VLPs in micrograms per 1011 CFU measured in five independent experiments (C). Error bars in panels B and C indicate standard errors.

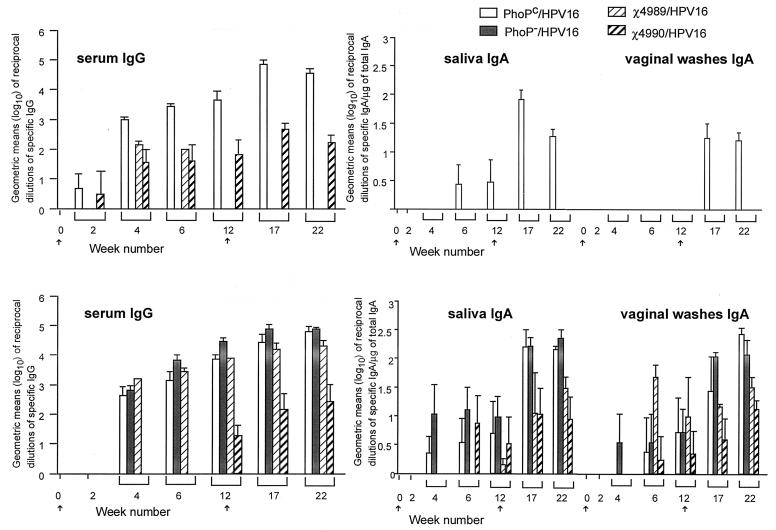

HPV16 VLP-specific antibody responses after nasal immunization with four S. typhimurium attenuated isogenic strains.

Our previous results involving nasal immunization with the PhoPc strain expressing HPV16 VLPs demonstrated the efficacity of this route of immunization in contrast to the oral route (26). Moreover, pilot experiments with administration of the other Salmonella strains expressing HPV16 VLPs by the oral route did not result in the induction of anti-HPV16 VLP antibodies (data not shown). Therefore, nasal immunization was used in the following experiments. Nasal immunization under anesthesia and sampling of female BALB/c mice were performed as described previously (19, 26). Four mice per group were immunized with 20 μl of inoculum (ca. 107 CFU, which corresponds to approximately 5 ng of HPV16 VLPs) of the different recombinant strains at weeks 0 and 12. Sampling of blood, saliva, and genital secretions was performed at weeks 0, 2, 4, 6, 12, 15, and 22. The anti-HPV16 VLP and anti-lipopolysaccharide (LPS) IgG and IgA titers were determined by ELISA (26) and are shown in Fig. 2. Surprisingly, only the PhoPc HPV16 strain elicited sustained levels of HPV-specific antibodies in serum and secretions. PhoP− HPV16 did not elicit any detectable HPV-specific antibodies, while χ4989 HPV16 induced transiently low anti-HPV16 VLP IgG levels in serum and χ4990 HPV16 induced variable low anti-HPV16 IgG levels in serum. Control ELISAs using purified HPV16 VLPs in carbonate buffer as the coating antigen did not reveal the presence of antibodies against unfolded HPV16 VLPs induced by any of the recombinant strains examined (data not shown). All recombinant strains induced anti-LPS antibodies at variable levels, but χ4990 required a booster immunization in order to do so.

FIG. 2.

Anti-HPV16 VLP and anti-LPS systemic IgG and mucosal IgA after nasal immunization with the four Salmonella HPV16 strains. Groups of four 6-week-old BALB/c female mice were immunized with ca. 107 CFU at weeks 0 and 12 (indicated by arrows). Data are expressed as the geometric means (log10) of reciprocal dilutions of specific IgG in serum and specific IgA per microgram of total IgA in secretions. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means.

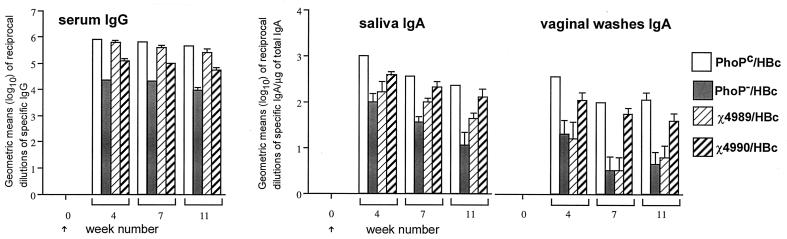

The four S. typhimurium attenuated isogenic strains expressing an unrelated viral antigen can induce specific antibodies after nasal immunization.

The immunogenicity of recombinant χ4989 and χ4990, as well as that of the PhoP− strain, has not been tested previously. Therefore, we tested the antibody responses elicited by these attenuated isogenic strains expressing the hepatitis B nucleocapsid HBc, an unrelated viral antigen that we have extensively used in the past (19, 30). The plasmid expressing HBc, pFS14PS2 (28), was electroporated in the four isogenic strains, and female BALB/c mice were intranasally immunized with 107 CFU at week 0. Sampling was performed at weeks 4, 7, and 11, and the presence of anti-HBc antibodies was determined by ELISA as described previously (19). In contrast to the results obtained with HPV16, all HBc recombinant strains induced HBc-specific antibodies in serum and secretions (Fig. 3), although the PhoP− strain appeared to induce lower anti-HBc IgG levels in serum.

FIG. 3.

Anti-HBc IgG in serum and IgA in secretions after nasal immunization with the four isogenic Salmonella HBc strains. Groups of four 6-week-old BALB/c mice were immunized with 107 CFU at week 0. Data are expressed as the geometric means (log10) of reciprocal dilutions of specific IgG in serum and specific IgA per microgram of total IgA in secretions. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means.

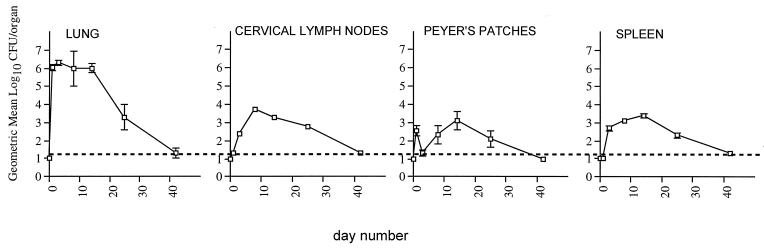

Recovery of the recombinant S. typhimurium 2 weeks after nasal immunization.

In order to obtain insights into the mechanisms that underlie the different antibody responses observed after nasal immunization with the different recombinant strains, we analyzed the survival of the bacteria and the maintenance of the plasmid encoding the foreign antigens in various organs. Survival experiments after oral immunization with various attenuated S. typhimurium strains have been performed, and the results have been used as indicators for the probable immunogenicity of a given strain (7, 9, 12, 30). Survival of bacteria after nasal immunization was only partially examined previously (1, 26, 31). We have shown that in anesthetized mice, one-third of the inoculum reaches the lungs, while the rest is swallowed (1). Here, a pilot experiment using 5 × 107 CFU of the PhoPc HBc strain as a nasal inoculum revealed that bacteria reached the lungs, cervical lymph nodes, Peyer’s patches, and spleen, from which they disappeared after 40 days (Fig. 4). About 2 weeks after nasal immunization, the numbers of bacteria peaked or plateaued in all of the organs examined. Therefore, we intranasally immunized eight groups of three female BALB/c mice with ca. 107 CFU of each of the recombinant S. typhimurium strains and examined survival in lung, cervical lymph nodes, Peyer’s patches, and spleen after 2 weeks. The organs were processed as previously described (26), and recovered bacteria were analyzed on medium containing or not containing ampicillin in order to discriminate between the Salmonella strains still harboring the plasmid encoding the heterologous antigen and the Salmonella strains that had lost the plasmid. As we have already described for PhoPc HPV16 (26), the plasmid encoding the HPV16 antigen was unstable in vivo in all of the strains examined, although at various levels (Table 1). This probably reflects the toxicity of the L1 molecule and a lack of antibiotic selection in vivo. In contrast, the plasmid encoding HBc was stable in all strains except the PhoP− one. The total numbers of salmonellae recovered after immunization with identical strains expressing either the HPV16 or the HBc antigens were very similar. However, the survival of the bacteria in the various organs differed, depending on the strain analyzed and irrespective of the antigen expressed. As expected, few or no bacteria were recovered from the spleen of mice immunized with the PhoP− strain (15) or with χ4990, a strain that bears a deletion in cdt, a gene responsible for colonizing deep tissue (8, 10, 20). However, we were unable to find any correlation between the number of salmonellae localized in a given organ and the antibody responses induced. For instance, the highest numbers of salmonellae still harboring the HPV16 plasmid were found with χ4989 and not with the PhoPc strain. An exception might be the lowest response, by the PhoP− HBc strain, which might correlate with the instability of the HBc plasmid in that particular strain.

FIG. 4.

Recovery of S. typhimurium PhoPc HBc after nasal immunization. Groups of three 6-week-old BALB/c female mice were immunized with 5 × 107 CFU at day 0 and were sacrificed at different days postimmunization. The different organs were processed and plated on agar as previously described (26). Data are expressed as the geometric mean (log10) CFU per organ. The level of detection (20 CFU/organ, or log10 1.3) is indicated by a horizontal dashed line, and values below the level of detection are shown below that line. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means.

TABLE 1.

Recovery of the different recombinant Salmonella strains expressing HPV16 L1 VLP or HBc antigen 2 weeks after nasal immunization

| Attenuated Salmonella strain type | Organ analyzed | Total salmonellae recovered (mean [log10] CFU/organ ± SEM)

|

% of salmonellae bearing plasmida

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV | HBc | HPV | HBc | ||

| PhoPc | Lung | 5.30 ± 0.02 | 6.00 ± 0.03 | 3.2 | 100 |

| Cervical lymph node | 3.39 ± 0.09 | 3.51 ± 0.01 | 10 | 100 | |

| Peyer’s patches | 2.51 ± 0.34 | 3.11 ± 0.02 | NDa | 100 | |

| Spleen | 3.76 ± 0.13 | 3.29 ± 0.08 | ND | 100 | |

| PhoP− | Lung | 3.18 ± 0.05 | 3.15 ± 0.07 | ND | 37.3 |

| Cervical lymph node | 2.00 ± 0.09 | 2.32 ± 0.08 | ND | 10.7 | |

| Peyer’s patches | <1.3 | 2.39 ± 0.25 | ND | 8 | |

| Spleen | 1.60 ± 0.50 | 1.30 ± 0.13 | ND | 100 | |

| χ4989 | Lung | 7.76 ± 0.03 | 7.22 ± 0.40 | 0.6 | 100 |

| Cervical lymph node | 3.63 ± 0.05 | 3.33 ± 0.08 | 18.6 | 100 | |

| Peyer’s patches | 3.36 ± 0.17 | 2.00 ± 0.27 | 7.4 | 100 | |

| Spleen | 4.56 ± 0.23 | 4.55 ± 0.25 | 3.7 | 100 | |

| χ4990 | Lung | 3.85 ± 0.25 | 3.61 ± 0.07 | 45 | 100 |

| Cervical lymph node | 1.85 ± 0.18 | 2.10 ± 0.10 | ND | 100 | |

| Peyer’s patches | 2.55 ± 0.50 | 2.00 ± 0.25 | 10.2 | 100 | |

| Spleen | <1.3 | 1.30 ± 0.07 | ND | 100 | |

ND, not determined. The percentage of salmonellae bearing the plasmid was not calculated when the recovered number of bacteria either harboring the plasmid or not was below our level of detection (<log10 1.3).

The mechanisms that underlie the immune response elicited by Salmonella vaccine strains are unclear. Some authors propose that a longer persistence in the GALT is a key issue (12, 27, 35), while others claim that viability and persistence of Salmonella are not necessary and that the critical point is the initial amount of antigens that prime the GALT and not the viability of the carrier (5). In our case, it is not clear why three recombinant strains were not able to induce significant anti-HPV16 VLP antibodies, while they were able to induce anti-HBc antibodies. The IgG1/IgG2a ratio of specific antibody titers was <0.5 in the serum of the mice immunized with all of the recombinant strains (data not shown). This suggests that a Th1-like immune response was induced, as has already been reported for other S. typhimurium strains (4, 36, 37, 40). We did not find a correlation between the persistence of the recombinant Salmonella strains and the antibody responses elicited, and all recombinant strains produced similar amounts of the HPV16 VLP antigen in vitro. However, we cannot exclude a down regulation of antigen expression in vivo and/or that critical epitopes of the VLPs are not detected in our assay for VLP quantification. Viability of PhoPc HPV16 seems to be essential in order to induce an immune response, because we observed no HPV-specific antibodies after treating the bacteria with formol prior to immunization (data not shown). The phenotype of the PhoPc strain might be crucial for providing a maximal HPV16 VLP dose to antigen-presenting cells (38). Although it has been reported that antigen presentation in macrophages is less efficient for the PhoPc strain than for the PhoP− strain (39), this might not be the case for dendritic cells, which have recently been shown to take up the PhoPc strain (19a), or wild-type salmonellae (33). Moreover, a modification in the lipid A of the PhoPc strain has been reported to alter signaling and cytokine release (17). We are currently testing whether the PhoPc phenotype can be maintained when combined with safer attenuating mutations. However, elucidating the mechanisms by which the PhoPc HPV16 strain induces anti-HPV16 VLP antibodies will be crucial for the design of a new vaccine strain suitable for human use.

Acknowledgments

We thank Florian Schödel, who provided us with HBc and the plasmid pFS14PS2, and Neil Christensen for monoclonal antibodies H16.E70 and H16.V5.

This work was supported by the Fonds de Service of the Department of Gynecology, by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (no. 31-45720.95 to D.N.H. and no. 31-47110-96 to J.P.K.), from the Swiss League against Cancer (no. SKL 635-2-1998 to J.P.K.), from the National Institutes of Health (no. R01-DE06669 to R.C.), and from Bristol-Myers Squibb (to R.C.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Balmelli C, Roden R, Potts A, Schiller J, De Grandi P, Nardelli-Haefliger D. Nasal immunization of mice with human papillomavirus type 16 virus-like particles elicits neutralizing antibodies in mucosal secretions. J Virol. 1998;72:8220–8229. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8220-8229.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black R E, Levine M M, Clements M L, Losonsky G, Herrington D, Berman S, Formal S B. Prevention of shigellosis by a Salmonella typhi-Shigella sonnei bivalent vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:1260–1265. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.6.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosch F X, Manos M M, Munoz N, Sherman M, Jansen A M, Peto J, Schiffman M H, Moreno V, Kurman R, Shah K V. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in cervical cancer: a worldwide perspective. International Biological Study on Cervical Cancer (IBSCC) Study Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:796–802. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.11.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brett S J, Dunlop L, Liew F Y, Tite J P. Influence of the antigen delivery system on immunoglobulin isotype selection and cytokine production in response to influenza A nucleoprotein. Immunology. 1993;80:306–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardenas L, Dasgupta U, Clements J D. Influence of strain viability and antigen dose on the use of attenuated mutants of Salmonella as vaccine carriers. Vaccine. 1994;12:833–840. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90293-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christensen N D, Dillner J, Eklund C, Carter J J, Wipf G C, Reed C A, Cladel N M, Galloway D A. Surface conformational and linear epitopes on HPV-16 and HPV-18 L1 virus-like particles as defined by monoclonal antibodies. Virology. 1996;223:174–184. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curtiss R., III . Attenuated Salmonella strains as live vectors for the expression of foreign antigens. In: Woodrow G C, Levine M M, editors. New generation vaccines. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1990. pp. 161–188. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtiss R, III, Hassan J O, Herr J, Kelly S M, Levine M, Mahairas G G, Milich D, Peterson D, Schödel F, Srinivasan J, Tacket C, Tinge S A, Wright R. Nonrecombinant and recombinant avirulent Salmonella vaccines. In: Talwar G P E A, editor. Recombinant and synthetic vaccines. New Delhi, India: Narosa Publishing House; 1994. pp. 340–351. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtiss R, III, Kelly S M. Salmonella typhimurium deletion mutants lacking adenylate cyclase and cyclic AMP receptor protein are avirulent and immunogenic. Infect Immun. 1987;55:3035–3043. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.12.3035-3043.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curtiss R, III, Kelly S M, Tinge S A, Tacket C O, Levine M M, Srinivasan J, Koopman M. Recombinant Salmonella vectors in vaccine development. In: Brown F, editor. Recombinant vectors in vaccine development. Vol. 82. Basel, Switzerland: Karger; 1994. pp. 23–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dougan G, Chatfield S, Pickard D, Bester J, O’Callaghan D, Maskell D. Construction and characterization of vaccine strains of Salmonella harboring mutations in two different aro genes. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:1329–1335. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.6.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunstan S J, Simmons C P, Strugnell R A. Comparison of the abilities of different attenuated Salmonella typhimurium strains to elicit humoral immune responses against a heterologous antigen. Infect Immun. 1998;66:732–740. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.732-740.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fields P I, Groisman E A, Heffron F. A Salmonella locus that controls resistance to microbiocidal proteins from phagocytic cells. Science. 1989;243:1059–1062. doi: 10.1126/science.2646710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fields P I, Swanson R V, Haidaris C G, Heffron F. Mutants of Salmonella typhimurium that cannot survive within the macrophage are avirulent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5189–5193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galán J E, Curtiss R., III Virulence and vaccine potential of phoP mutants of Salmonella typhimurium. Microb Pathog. 1989;6:433–443. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(89)90085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15a.Garcia Vescovi E, Soncini F C, Groisman E A. Mg2+ as an extracellular signal: environmental regulation of Salmonella virulence. Cell. 1996;84:165–174. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15b.Groisman E A, Chiao E, Lipps C J, Heffron F. Salmonella typhimurium phoP virulence gene is a transcriptional regulator. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7077–7081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.7077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gunn J S, Hohmann E L, Miller S I. Transcriptional regulation of Salmonella virulence: a PhoQ periplasmic domain mutation results in increased net phosphotransfer to PhoP. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6369–6373. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6369-6373.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo L, Lim K B, Gunn J S, Bainbridge B, Darveau R P, Hackett M, Miller S I. Regulation of lipid A modifications by salmonella typhimurium virulence genes phop-phoq. Science. 1997;276:250–253. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5310.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hohmann E L, Oletta C A, Killeen K P, Miller S I. Phop/phoq-deleted salmonella typhi (ty800) is a safe and immunogenic single-dose typhoid fever vaccine in volunteers. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1408–1414. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.6.1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18a.Hoiseth S K, Stocker B A. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature. 1981;291:238–239. doi: 10.1038/291238a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hopkins S, Kraehenbuhl J-P, Schödel F, Potts A, Peterson D, De Grandi P, Nardelli-Haefliger D. A recombinant Salmonella typhimurium vaccine induces local immunity by four different routes of immunization. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3279–3286. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3279-3286.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19a.Hopkins, S., et al. Submitted for publication.

- 20.Kelly S M, Bosecker B A, Curtiss R., III Characterization and protective properties of attenuated mutants of Salmonella choleraesuis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4881–4890. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.11.4881-4890.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirnbauer R, Taub J, Greenstone H, Roden R, Dürst M, Gissmann L, Lowy D R, Schiller J T. Efficient self-assembly of human papillomavirus type 16 L1 and L1-L2 into virus-like particles. J Virol. 1993;67:6929–6936. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.6929-6936.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller I, Maskell D, Hormaeche C, Johnson K, Pickard D, Dougan G. Isolation of orally attenuated Salmonella typhimurium following TnphoA mutagenesis. Infect Immun. 1989;57:2758–2763. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.9.2758-2763.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller S I, Kukral A M, Mekalanos J J. A two-component regulatory system (phoP phoQ) controls Salmonella typhimurium virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5054–5058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.5054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23a.Miller, S. I., W. P. Loomis, C. Alpuche-Aranda, I. Behlau, and E. Hoffman. The PhoP virulence regulon and live oral Salmonella vaccines. Vaccine 11:122–125. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Miller S I, Mekalanos J J. Constitutive expression of the PhoP regulon attenuates Salmonella virulence and survival within macrophages. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2485–2489. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.5.2485-2490.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nardelli-Haefliger D, Kraehenbuhl J-P, Curtiss III R, Schödel F, Potts A, Kelly S, De Grandi P. Oral and rectal immunization of adult female volunteers with a recombinant attenuated Salmonella typhi vaccine strain. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5219–5224. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5219-5224.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nardelli-Haefliger D, Roden R B S, Benyacoub J, Sahli R, Kraehenbuhl J-P, Schiller J T, Lachat P, Potts A, De Grandi P. Human papillomavirus type 16 virus-like particles expressed in attenuated Salmonella typhimurium elicit mucosal and systemic neutralizing antibodies in mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3328–3336. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3328-3336.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts M, Chatfield S N, Dougan G. Salmonella as carriers of heterologous antigens. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press Inc.; 1994. pp. 27–58. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schödel F. Prospects for oral vaccination using recombinant bacteria expressing viral epitopes. Adv Virus Res. 1992;41:409–446. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schödel F, Enders G, Jung M-C, Will H. Recognition of a hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid T-cell epitope expressed as a fusion protein with the subunit B of Escherichia coli heat labile enterotoxin in attenuated salmonellae. Vaccine. 1990;8:569–572. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(90)90010-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schödel F, Kelly S M, Peterson D L, Milich D R, Curtiss R., III Hybrid hepatitis B virus core–pre-S proteins synthesized in avirulent Salmonella typhimurium and Salmonella typhi for oral vaccination. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1669–1676. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1669-1676.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Srinivasan J, Nayad A, Curtiss R., III . Effect of the route of immunization using recombinant Salmonella on mucosal and humoral immune responses. Vaccines 95. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Srinivasan J, Tinge S, Wright R, Herr J C, Curtiss R., III Oral immunization with attenuated salmonella expressing human sperm antigen induces antibodies in serum and the reproductive tract. Biol Reprod. 1995;53:462–471. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod53.2.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Svensson M, Stockinger B, Wick M J. Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells can process bacteria for mhc-i and mhc-ii presentation to t cells. J Immunol. 1997;158:4229–4236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tacket C O, Hone D M, Losonsky G A, Guers L, Edelman R, Levine M M. Clinical acceptability and immunogenicity of CVD 908 Salmonella typhi vaccine strain. Vaccine. 1992;10:443–446. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(92)90392-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tacket C O, Kelly S M, Schödel F, Losonsky G, Nataro J P, Edelman R, Levine M M, Curtiss R., III Safety and immunogenicity in humans of an attenuated Salmonella typhi vaccine vector strain expressing plasmid-encoded hepatitis B antigens stabilized by the Asd-balanced lethal vector system. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3381–3385. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3381-3385.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thatte J, Rath S, Bal V. Immunization with live versus killed Salmonella typhimurium leads to the generation of an IFN-gamma-dominant versus an IL-4-dominant immune response. Int Immunol. 1993;5:1431–1436. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.11.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vancott J L, Staats H F, Pascual D W, Roberts M, Chatfield S N, Yamamoto M, Coste M, Carter P B, Kiyono H, McGhee J R. Regulation of mucosal and systemic antibody responses by t helper cell subsets, macrophages, and derived cytokines following oral immunization with live recombinant salmonella. J Immunol. 1996;156:1504–1514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walker R I. New strategies for using mucosal vaccination to achieve more effective immunization. Vaccine. 1994;12:387–400. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wick M J. The phoP locus influences processing and presentation of Salmonella typhimurium antigens by activated macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:465–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang D M, Fairweather N, Button L L, McMaster W R, Kahl L P, Liew F Y. Oral Salmonella typhimurium (AroA−) vaccine expressing a major leishmanial surface protein (gp63) preferentially induces T helper 1 cells and protective immunity against leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 1990;7:2281–2285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang X, Kelly S M, Bollen W S, Curtiss R., III Characterization and immunogenicity of Salmonella typhimurium SL1344 and UK-1 Δcrp and Δcdt deletion mutants. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5381–5387. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5381-5387.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]