Abstract

As the leading cause of hyperthyroidism, Graves disease (GD) does not often present with its classical triad of pretibial myxedema, goiter, and exophthalmos but instead is often recognized by various manifestations such as tachycardia, weight loss, jaundice, or dermatopathy and requires utmost clinical vigilance. Three treatment modalities for GD exist as antithyroid drugs (ATDs), radioactive iodine (RAI), and surgery, but each bears its own serious side effects. Furthermore, there have been several reports in the literature about ATD resistance that can complicate management. We describe a rare complex case of methimazole (MMI)-resistant GD in a 58-year-old woman with multiple comorbidities including heart failure, atrial fibrillation, liver cirrhosis, and hypertension. She presented with an initial complaint of diffuse swelling and was found to have severe thyrotoxicosis. Despite high doses of MMI, her thyroid function remained significantly elevated. Thyroid uptake and scan while on MMI showed high radioactive iodine uptake. After receiving RAI therapy, her thyroid function and bilirubin improved markedly, liver enzymes remained stable, and anasarca responded to diuretics. This case highlights the challenges in managing resistant GD and emphasizes the necessity of personalized treatment plans.

Keywords: Graves’ disease, methimazole-resistant Graves, hyperthyroidism, cirrhosis, antithyroid drugs, radioactive iodine therapy

Introduction

Graves’ disease (GD) is an autoimmune disorder and is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism [1]. A combination of pretibial myxedema, goiter, and exophthalmos make up its recognizable classic form. However, presentations may be nontypical such as tachycardia, heart failure (HF), muscle weakness, weight loss, psychosis, anemia, etc. Furthermore, diagnosis can be difficult in severely ill patients with apathetic hyperthyroidism [2].

Typical management includes antithyroid drugs (ATDs), radioactive iodine (RAI) therapy, and thyroidectomy. Treatment aims to control hyperthyroidism and alleviate symptoms, but a subset of patients may exhibit resistance or intolerance to conventional therapies, necessitating alternative strategies for definitive treatments [1, 3‐5]. Some culprits to this resistance to treatment can include nonadherence, malabsorption, increased metabolism, genetic factors, and environmental factors [6]. We report a challenging case in a patient with multiple comorbidities and severe GD that was resistant to ATD, underscoring the complexities in management and the need for individualized treatment approaches.

Case Presentation

We report the case of a 58-year-old female with a history of GD, HF, atrial fibrillation, idiopathic liver cirrhosis, and hypertension who presented to our emergency room with anasarca, jaundice, and shortness of breath and found to have severe thyrotoxicosis. She takes apixaban, diltiazem, propranolol, and cyclobenzaprine. She does not take biotin. She had GD that was previously treated with methimazole (MMI) 40 mg daily, but MMI was stopped 4 months prior at an outside hospital due to acute liver injury in the setting of a septic shock from COVID pneumonia and gram-positive cocci bacteremia. She was discharged on propranolol alone. A detailed history suggests that her GD has been diagnosed for more than 10 years and managed with intermittent MMI. She is a nonsmoker and has a family history of Hashimoto’s disease.

Diagnostic Assessment

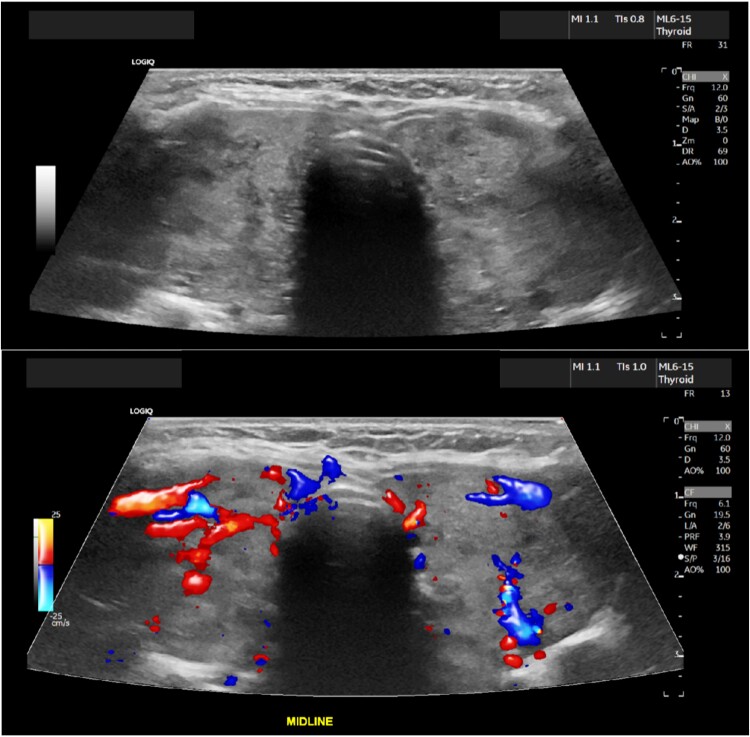

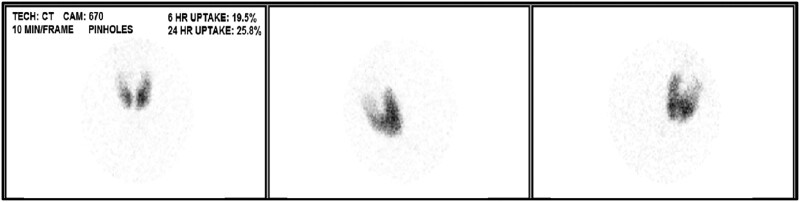

Blood pressure was 120/59, heart rate was 76, respiratory rate was 16, temperature was 98.6oF (37 °C), and oxygen saturation was 94% on room air. The physical exam was notable for a diffusely enlarged thyroid gland without nodularity on palpation, irregularly irregular heart rate, moderate eye proptosis with watery discharge, scleral icterus, distended abdomen with positive fluid thrill, and severe pedal edema bilaterally. Labs showed undetectable TSH, free T4 > 7.77 ng/dL (>100 pmol/L) (reference range 0.92-1.68 ng/dL; 11.8-21.6 pmol/L), free T3 > 20.0 pg/mL (>30.7 pmol/L) (reference range 2.3-4.2 pg/mL; 3.5-6.4 pmol/L), thyrotropin receptor antibody 7.07 IU/L (reference range ≤1.75 IU/L), and a pro-b-type natriuretic peptide 1964 pg/mL (232 pmol/L) (reference range 0-899 pg/mL; 0-106 pmol/L). White blood count 4 × 103/µL (4 × 109/L) (reference range 4.5-11 × 103/µL & 109/L), hemoglobin 10.8 g/dL (108 g/L) (reference range 14-18 g/dL; 140-180 g/L), and platelets 99 × 103/µL (99 × 109/L) (reference range 150-450 × 103/µL and 109/L). Hepatic functions showed total bilirubin of 9 mg/dL (154 μmol/L) (reference range 0-1.1 mg/dL; 0-18.8 μmol/L), albumin of 3.3 g/dL (33 g/L) (reference range 3.9-5.2 g/dL; 39-52 g/L), and liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase 41 U/L (reference range 0-32 U/L), alanine aminotransferase 13 U/L (reference range 0-33 U/L), alkaline phosphatase 157 U/L (reference range 40-135 U/L). Workup for liver injury found negative viral hepatitis panel, antinuclear, smooth muscle, alpha-1 antitrypsin, and mitochondrial antibodies. Ultrasound of the thyroid revealed an enlarged heterogenous, hypervascular thyroid gland. This is shown in Fig. 1. The echocardiogram revealed a low normal systolic function of the left ventricle with an ejection fraction of 50% to 55%, marked dilatation of the left atrium and mildly enlarged right atrium and ventricle, and mild to moderate tricuspid regurgitation. Limited abdominal ultrasound of the right upper quadrant was notable for coarsened hepatic echotexture with a subtle nodular surface contour concerning for cirrhosis and small volume ascites without significant portal hypertension. Radioactive iodine uptake (RAIU) and scan demonstrated uniform increased tracer uptake within an enlarged gland without hypofunctional or hyperfunctional nodule while on MMI 80 mg daily (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Enlarged heterogeneous, hypervascular thyroid gland with the right lobe being 6.9 × 2.6 × 2.8 cm and the left lobe being 6.8 × 3.1 × 2.8 cm.

Figure 2.

Uniformly increased tracer uptake in enlarged thyroid gland on radioactive iodine uptake while hyperthyroid on methimazole 80 mg daily without hypo/hyperfunctional nodules. The 6-hour RAIU was 20% (reference range 5-15%), and the 24-hour RAIU was 26% (reference range 10-30%).

Abbreviation: RAIU, radioactive iodine uptake.

Treatment

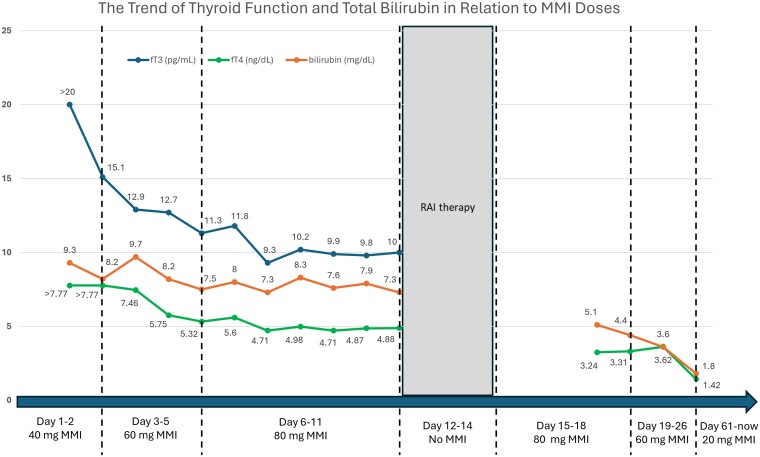

The patient was given MMI 20 mg twice a day, cholestyramine 4 g twice a day, propranolol, and IV diuretics followed by paracentesis. Given the severity of her GD, Graves’ eye disease, and the resistance to ATD, she was referred for thyroidectomy; however, she was declined due to increased risk of bleeding and postoperative complications as a cirrhotic patient. Consequently, medical therapy was intensified with MMI 20 mg four times a day and cholestyramine 8 g twice a day, but her free T4 remained significantly elevated. Subsequently, RAI was pursued after thyroid uptake and scan demonstrated a uniformly increased RAIU at 6 hours despite being on 80 mg MMI daily. To ensure the effectiveness of RAI, a higher than typical dose of I-131 for GD at 30 mCi was administered under standard contact precautions for radiation materials while holding MMI for 3 days. A short course of prednisone of 30, 20, and 10 mg daily with each dose for 1 week was initiated to prevent the worsening of her ophthalmopathy. Posttreatment, she tolerated the RAI well without neck pain and continued MMI 20 mg four times a day, cholestyramine 8 g twice a day, and propranolol 20 mg twice a day. Her free T4 and free T3 improved significantly, along with her bilirubin (Fig. 3). Her albumin, transaminases, and alkaline phosphatase were normalized. Her anasarca eventually responded to diuretics.

Figure 3.

The trend of changes in the thyroid function and bilirubin level in response to methimazole dose during and after hospitalization. (Free T3 1 pg/mL is about equal to 1.536 pmol/L; free T4 1 ng/dL is about equal to 12.87 pmol/L; bilirubin 1 mg/dL is about equal to 17.1 µmol/L.)

Outcome and Follow-up

She was discharged home on MMI 20 mg three times a day, cholestyramine 8 mg twice a day, prednisone 30 mg daily, and propranolol 20 mg twice a day. The patient established care with our community care clinic as an uninsured patient. Up to 2 months follow-up, her thyroid function became normal, and her hepatic tests remained normal on MMI 20 mg daily.

Discussion

GD often presents with various manifestations including HF, muscle weakness, and liver dysfunction [1, 2]. Liver dysfunctions are observed in 15% to 79% of patients with untreated hyperthyroidism, ranging from mild hepatitis to acute liver failure requiring transplantation. It can either worsen a pre-existing liver condition like cirrhosis or trigger an acute liver injury in a previously healthy liver [7-11]. The pattern of liver injury varies depending on the specific etiology and the mechanism of damage. For example, ischemic damage to hepatocytes from HF due to thyrotoxicosis often results in elevated aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels initially [7, 8]. Later, congestive hepatopathy from HF and/or cirrhosis can both cause an elevated bilirubin [2, 8]. Autoimmune conditions that coexist with GD such as primary biliary cirrhosis, autoimmune cholangiopathy, and autoimmune hepatitis typically produce a cholestatic pattern of injury with increased alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin levels [8]. Although liver injury due to ATDs is rare, occurring in only 0.1% to 0.2% of cases compared to thyrotoxicosis, it should always be considered if liver enzymes are normal before starting it [7].

MMI is thought to induce hepatic damage through several mechanisms, such as the formation of reactive metabolites, oxidative stress induction, intracellular target dysfunction, and immune-mediated toxicity [10]. The liver injury associated with MMI is typically cholestatic while propylthiouracil (PTU) is typically hepatocellular and the classic risk factors described in the literature include the older age of the recipient and higher doses of the drugs [11, 12]. The situation is further complicated by the fact that thyrotoxicosis itself can precipitate acute liver injury or worsen preexisting chronic liver conditions. Therefore, increases in liver enzymes and liver dysfunctions while on ATD in GD may not necessarily be attributed to drug side effects but could instead result from alterations in thyroid function, which are likely to improve with the control of the underlying thyrotoxicosis. This was evident in our case.

ATDs, RAI, and surgery can all be used for the treatment of GD. ATDs, such as MMI and PTU, are one of the more common choices for GD therapy because of their low cost and the chance of permanent remission, especially in patients with mild disease. Some patients treated with ATD also can avoid permanent hypothyroidism compared to RAI and surgery. ATD has both minor side effects such as rash, hives, arthralgias, and gastrointestinal symptoms and major side effects such as agranulocytosis, vasculitis, and hepatitis [3-5].

Our patient had severe hyperthyroidism with free T4 about 5 times the upper normal limit in the setting of multiple comorbidities and moderate Graves’ ophthalmopathy. We started her on MMI due to its higher efficacy and superior safety profile compared to PTU [4, 10-13]. A typical starting dose would be 15 mg a day for mild to moderate cases of GD and 30 mg daily for severe cases of GD [13]. Our patient remained highly thyrotoxic even with a much higher dose of MMI 80 mg/day combined with adjunctive cholestyramine, prompting the exploration of alternative therapeutic modalities.

RAI can lead to permanent resolution of hyperthyroidism. It used to be the first choice for definitive therapy for GD but ATDs have become more preferred therapy in the United States as well as the rest of the world [4]. RAI is a great option for patients with contraindication or refractory to ATD and increased surgical risk just like our patient. However, permanent hypothyroidism and radiation precautions have limited its use despite its shorter duration of isolation than thyroid cancer patients treated with RAI. There is also a possibility to develop or worsen Graves’ ophthalmopathy and small concerns for secondary malignancy. Women planning pregnancy should wait for at least 6 months after RAI [5].

Surgery is another option for a rapid, permanent cure of hyperthyroidism. It is best for patients with large goiters having symptomatic compression, suspicious nodules, or concurrent hyperparathyroidism. Surgery is also preferred for patients who are refractory to ATD with moderate to severe active Graves’ ophthalmopathy or uncontrolled GD during second-trimester pregnancy. There are risks for surgical complications such as iatrogenic hypoparathyroidism and recurrent laryngeal nerve damage [3, 5]. Our patient was declined for surgery due to her cirrhosis, and after discussion with the patient and other teams, RAI was pursued as the final option given her MMI resistance.

Resistance to MMI has been infrequently described in case reports and series, and switching to PTU is the first step but is seldom successful and poses its own side effects. Other options include lithium carbonate, iodide, RAI or thyroidectomy, and even short-term plasmapheresis in extreme cases [14, 15]. There are many proposed influencing factors and potential underlying mechanisms in ATD resistance. In general, poor medical adherence, malabsorption, and increased metabolism/excretion of the drug may limit its efficacy. Patients with higher thyrotropin receptor antibody levels, a larger goiter size, and endorsing orbitopathy at the time of GD diagnosis have significantly increased recurrence risk as well [6]. Our patient seemed to have a lot of these features. Malabsorption due to edema in the gastrointestinal tract may underplay the resistance in our patient. Administration of cholestyramine and MMI in the setting of high bilirubin may also jeopardize the maximum effect of MMI if not carefully timed.

While the 3 mainstream modalities for GD treatment have not changed over many years, proper management with individualized therapy remains important.

Learning Points

ATD-resistant GD can be successfully treated with individualized alternatives.

Liver dysfunctions rarely can be caused by ATDs but are more frequently observed in patients with GD due to severe thyrotoxicosis, which can be reversible.

A thyroid uptake scan is usually performed off MMI, but it can still be informational while in a hyperthyroid state on MMI during rare occasions.

Acknowledgments

None.

Contributor Information

Michael Tang, Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75246, USA.

Bashar Fteiha, Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75246, USA.

Shumei Meng, Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75246, USA; Texas A&M School of Medicine, Bryan, TX 77807, USA.

Contributors

All authors made individual contributions to authorship. S.M. and B.F. were involved in the diagnosis and management of this patient. M.T., S.M., and B.F. were involved in the manuscript preparation and submission. All authors reviewed and approved the final draft.

Funding

No public or commercial funding.

Disclosures

None declared.

Informed Patient Consent for Publication

Signed informed consent was obtained directly from the patient.

Data Availability Statement

Original data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

- 1. Smith TJ, Hegedüs L. Graves’ disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(16):1552‐1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hegazi M, Ahmed S. Atypical clinical manifestations of graves’ disease: an analysis in depth. J Thyroid Res. 2012;2012:768019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bartalena L. Diagnosis and management of graves disease: a global overview. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9(12):724‐734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Villagelin D, Cooper DS, Burch HB. A 2023 international survey of clinical practice patterns in the management of graves disease: a decade of change. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024;109(11):2956‐2966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hoang TD, Stocker DJ, Chou EL, et al. 2022 update on clinical management of graves disease and thyroid eye disease. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2022;51(2):287‐304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu J, Fu J, Xu Y, et al. Antithyroid drug therapy for graves’ disease and implications for recurrence. Int J Endocrinol. 2017;2017:3813540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yorke E. Hyperthyroidism and liver dysfunction: a review of a common comorbidity. Clin Med Insights Endocrinol Diabetes. 2022;15:11795514221074672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khemichian S, Fong TL. Hepatic dysfunction in hyperthyroidism. Gastroenterology Hepatology (N Y). 2011;7(5):337‐339. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. de Campos Mazo DF, de Vasconcelos GB, Pereira MA, et al. Clinical spectrum and therapeutic approach to hepatocellular injury in patients with hyperthyroidism. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2013;6:9‐17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heidari R, Niknahad H, Jamshidzadeh A, et al. An overview on the proposed mechanisms of antithyroid drugs-induced liver injury. Adv Pharm Bull. 2015;5(1):1‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Khan AA, Ata F, Aziz A, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with antithyroid drug-related liver injury. J Endocr Soc. 2023;8(1):bvad133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Heidari R, Niknahad H, Jamshidzadeh A, et al. Factors affecting drug-induced liver injury: antithyroid drugs as instances. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2014;20(3):237‐248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nakamura H, Noh JY, Itoh K, et al. Comparison of methimazole and propylthiouracil in patients with hyperthyroidism caused by graves’ disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(6):2157‐2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baser OO, Cetin Z, Catak M, et al. The role of therapeutic plasmapheresis in patients with hyperthyroidism. Transfus Apher Sci. 2020;59(4):102744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mori Y, Hiromura M, Terasaki M, et al. Very rare case of graves’ disease with resistance to methimazole: a case report and literature review. J Int Med Res. 2021;49(3):300060521996192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Original data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article.