Abstract

We have developed a web tool, PupasView, for the selection of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with potential phenotypic effect. PupasView constitutes an interactive environment in which functional information and population frequency data can be used as sequential filters over linkage disequilibrium parameters to obtain a final list of SNPs optimal for genotyping purposes. PupasView is the first resource that integrates phenotypic effects caused by SNPs at both the translational and the transcriptional level. PupasView retrieves SNPs that could affect conserved regions that the cellular machinery uses for the correct processing of genes (intron/exon boundaries or exonic splicing enhancers), predicted transcription factor binding sites and changes in amino acids in the proteins for which a putative pathological effect is calculated. The program uses the mapping of SNPs in the genome provided by Ensembl. PupasView will be of much help in studies of multifactorial disorders, where the use of functional SNPs will increase the sensitivity of the identification of the genes responsible for the disease. The PupasView web interface is accessible through http://pupasview.ochoa.fib.es and through http://www.pupasnp.org.

INTRODUCTION

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are the simplest and most frequent type of DNA sequence variation among individuals and, with the recent availability of high-throughput methodologies, are considered one of the most powerful tools in the search for e.g. disease susceptibility genes and drug response-determining genes (1,2). However, complex diseases, for which markers display weak associations, still constitute a challenge. Most probably, advancement in the knowledge of such diseases will come from improved genotyping methods in combination with the proper bioinformatics design strategies (3).

It is generally believed that multigenicity reflects disruptions in proteins that participate in a protein complex or in a pathway (4). Typically, SNPs have been used as markers; that is, the real determinant of the disease was not the SNP itself but some other mutation in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with it. Because of this, the use of functional SNPs could be an important factor in increasing significantly the sensitivity of association tests. In fact, several complex genetic disorders such as Alzheimer's disease (5) and Crohn' disease (6) have been associated with functional SNPs, lending weight to strategies giving priority to candidate markers based upon predictable function. Several estimations suggest that, on average, some 20% of SNPs could directly damage proteins (7).

Much attention has been focused on modelling by different methods the possible phenotypic effect of SNPs that cause amino acid changes (7–13), and only recently has interest focused on functional SNPs affecting regulatory regions or the splicing process (14). However, there is increasing evidence that many human disease genes are the result of exonic or non-coding mutations affecting regulatory regions (15–17). A recent large-scale screening over a set of 16 chromosomes found SNPs in the promoter regions of 35% of the genes, and experimental evidence suggested that around a third of promoter variants may alter gene expression to a functionally relevant extent (18). Alternative splicing produced by mutations in intron/exon junctions, or in distinct binding motifs, such as exonic splicing enhancers (ESEs) (19), has also been related to different diseases (20). In fact, it has been estimated that 15% of point mutations that result in human genetic diseases cause RNA splicing defects (21).

In addition to functional information, population frequency is another important factor to be taken into account when selecting SNPs. Thus, infrequent polymorphisms will be of scarce interest as markers. Also, LD is another interesting factor in selecting SNPs as markers since, if two SNPs are in strong LD, only one of them will provide enough information for any association or linkage test.

With the idea of selecting optimal sets of SNPs using as much information as possible on putative phenotypic effect, population frequencies and LD, we have developed PupasView (Putative Phenotypic Alterations caused by SNPs Viewer), a server that can be used alone or in combination with PupaSNP (14).

PupasView works not only as a viewer of where SNPs are located, but also as a selector in which different filters based on combinations of functionality and population frequencies can be interactively applied over the LD parameters in order to obtain an optimal selection of SNPs for genotyping studies, in such a way that with a minimum number of SNPs maximum information on the genic region is obtained.

Criteria to consider an SNP a good candidate for genotyping studies

There are three important properties for an SNP to be considered an optimal candidate for genotyping purposes: functional effect, minor allele frequency and LD with respect to other SNPs. Finding such optimal SNPs is not always possible, but the idea behind PupasView is to facilitate the selection process in order to achieve a final collection of SNPs bearing the maximum amount of information. PupasView works as an SNP selector. Different filters can be interactively applied to the LD information available based on distinct functional properties, cross-species conservation and population frequency. This permits a final selection of a minimum number of SNPs with optimal properties in terms of population frequencies and potential phenotypic effect.

Finding SNPs with potential phenotypic effect

PupasView uses a precompiled database which contains a collection of dbSNP entries mapped to the Golden Path genome assembly, as implemented in the human section of Ensembl (http://www.ensembl.org). Part of this database is common to the PupaSNP program (14). The SNPs have been labelled according to their potential effects on the phenotype. We have taken into account both transcriptional and gene product levels. Regions 10 000 bp upstream of the genes belonging to the promoter region of each gene in the list have been scanned for the presence of possible different regulatory motifs. These include alterations in:

Transcription factor binding sites. Promoter regions were scanned for the presence of possible transcription factor binding sites. The program Match (22) was used for this purpose, using only high-quality matrices and with a cut-off to minimize false positives from the Transfac database (23). SNPs located within these motifs are considered to have a putative phenotypic effect in the expression of the gene. Almost four million such motifs were found, with 130 373 SNPs mapping onto them.

Intron/exon border consensus sequences. Ensembl APIs (24) were used to extract the intron/exon organization of the genes and the corresponding sequences. The two conserved nucleotides on each side of the splicing point, which constitute the splicing signal (21), were then located and all the SNPs altering these signals were recorded. More than 700 000 intron/exon boundaries could be defined in human genes with 1786 SNPs mapping onto them.

ESEs. Mutations that inactivate or activate an ESE sequence may result in exon skipping, errors in alternative splicing patterns, malformation and so on. Different classes of ESE consensus motifs have been described, but they are not always easily identified. Exon sequences were scanned to identify putative ESEs responsive to the human SR proteins SF2/ASF, SC35, SRp40 and SRp55, using the available weight matrices (20). A score was obtained that is related to the likelihood that the site found is a real ESE. Only ESE sites with scores over the threshold [see (20) for details] were taken into account in the analysis. More than 11 million ESEs were found, with 299 106 SNPs located in them.

Triplex-forming oligonucleotide target sequences (TTSs). It has been found that the population of TTSs is much more numerous than expected from simple random models (25). The population of TTSs is large in the whole genome, without major differences between chromosomes, but with a large concentration in regulatory regions, especially in promoter zones, which suggests a tremendous potential for triplex strategy in the control of gene expression (25). Although the role of TTSs in regulation is still a matter of speculation, the program also reports SNPs disrupting these structures. Some 5.4 million putative triplex-forming sequences were found, and 364 314 SNPs mapped onto them.

SNPs in exons that cause an amino acid change. Any SNP causing a change of amino acid, independent of any speculation on its possible phenotypic effect, is reported. There are 45 906 such SNPs.

SNPs in exons that cause an amino acid change with putative pathological effect. The putative pathological effect of an amino acid change can be predicted using neural networks (NNs) carefully trained to predict disease-associated amino acidic polymorphism (12,13). The server implements a small NN (1 hidden layer and 20 nodes) and three sequence-derived descriptors (PAM40, PSSM and variability), which are either retrieved from databases or determined internally from multiple alignments using two-iterations PSI-Blast (26) run over a non-redundant SwissProt/TrEMBL database. The trained method displays a success rate >80% in cross-validation experiments. According to the algorithm, 19 309 SNPs displayed a high probability of having pathological effect.

Human–mouse conserved regions. Untranslated whole genome comparisons by BLASTZ were performed for species pairs which are thought to be similar enough to be able to detect homology directly at the DNA level (27). Of particular interest is mouse (or rat) because of its phylogenetic position with respect to humans: distant enough to interpret conservation as important but not so distant as to lose most of the similarity. The phenotypic effect of a change in such regions is quite speculative, but cross-species conservation can be useful in cases in which no other information is available. It is also useful for reinforcing the likelihood of other predictions (e.g. an ESE in a conserved region is more likely to be real than one in a non-conserved region).

Frequency information and validation status

There are >10 million SNPs stored in the last build of dbSNP (build 124), and more than half of these have been validated by different means (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/snp_summary.cgi). Validation status is annotated and is an important field in terms of trusting an SNP. But, in addition to being real, an SNP must exist in the population at frequencies which make it a suitable marker. Very infrequent SNPs are not suitable for association or linkage studies. For almost half a million SNPs frequency data in different populations are available.

Blocks and LD parameters

LD measures the correlation between two neighbouring genetic variants in a specific population. The program HaploView (28) is used to infer blocks using different procedures. In one of the most common procedures (29), 95% confidence bounds based on the D′ LD parameter are generated and each comparison is called ‘strong LD’, ‘inconclusive’ or ‘strong recombination’. A block is created if 95% of informative (i.e. non-inconclusive) comparisons are ‘strong LD’. A block can be considered a region with a low recombination rate. Ideally, a block could properly be described by a unique SNP. Two other methods are used: the four gamete rule (30) and the Solid Spine of LD (28). Blocks are displayed in the bottom of the PupasView window. Also D′, R2 and LOD parameters between adjacent SNPs can be visualized by placing the cursor between them. Only HapMap genotyped SNPs (31) are used to calculate blocks and LD parameters.

The web interface of the SNPs selector

The main purpose of PupasView is to provide the user with an optimal set of SNPs for genotyping experiments by filtering the annotated SNPs using a series of filters related to their impact in protein functionality and pathology, their population frequency and LD.

The input is a gene identifier (Ensembl IDs or external IDs, which include GenBank, Swissprot/TrEMBL and other gene IDs supported by Ensembl). The program can also be invoked from PupaSNP. The program presents a list of options that can be selected and applied as many times as desired. The options include

Validation status obtained from dbSNP

Type of SNP (coding, intron, untranslated region, local), according to its position in the gene

Frequency and population, an option that allows the possibility of filtering by a range of frequencies of the minor allele in one or more populations (Europe; Europe, multinational; Europe, North America; North America; Central/South America; North/East Africa and Middle East; Central/South Africa; West Africa; Central Asia; East Asia; Pacific; multinational; unknown; HapMap)

- Functional properties as follows:

- –

-

–SNPs disrupting predicted transcription factor binding sites (all or only those that are in regions conserved in the mouse genome)

-

–SNPs disrupting predicted ESEs (all or only those that are in regions conserved in the mouse genome)

-

–SNPs disrupting potential triplex-forming regions (all or only those that are in regions conserved in the mouse genome)

-

–SNPs disrupting intron/exon boundaries

-

–regions conserved in mouse

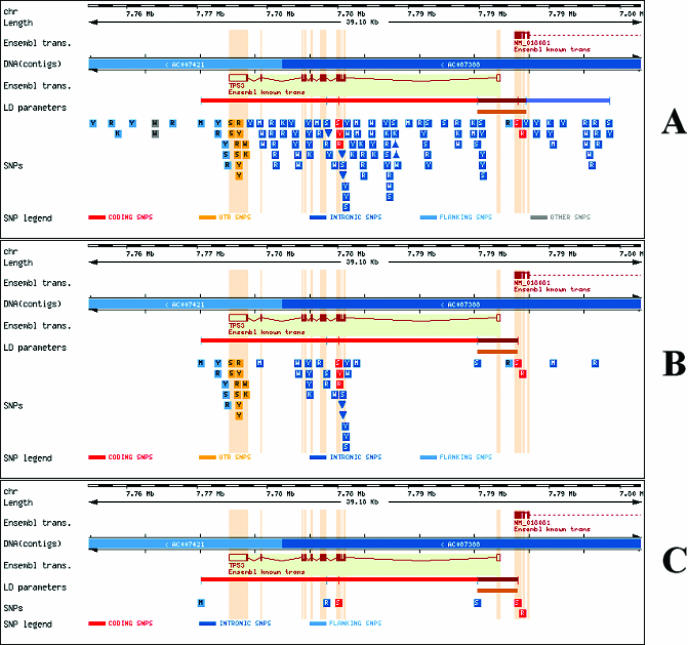

Figure 1 shows the view of the results. The viewer of PupasView has been constructed using Ensembl APIs (24). Figure 1A shows the result of running PupasView on the gene TP53 without applying any filter. All the SNPs in the gene and the neighbourhood are displayed. If the cursor is over an SNP, information on it is displayed by means of pop-up text. Figure 1B shows a subselection of these SNPs obtained after selecting only SNPs for which population frequency was available. Finally, Figure 1C shows the selection obtained if only SNPs with putative functional effect are chosen. This will constitute the final, reduced subset of optimal SNPs. The upper horizontal bar below the figure represents LD parameters (which can be individually obtained by placing the cursor over them). The lower horizontal bar represents the block found with the selected algorithm. The blocks are displayed graphically with brown rectangles going from the first to the last SNP within the block. When the cursor is over the rectangles, a tooltip text pops up in the block showing the SNPs and the haplotypes (with HapMap frequencies in parentheses). Tag SNPs are signalled with an exclamation mark (!).

Figure 1.

Sequential application of filters in PupasView. (A) SNPs in gene TP53. (B) SNPs together with population frequencies. (C) SNPs with any functional characteristic. Depending on the versions of Ensembl and dbSNP, the appearance of the figure can change.

DISCUSSION

It is believed that improved genotyping methods in combination with the proper bioinformatics design strategies will offer better opportunities for the study of complex diseases (3). The use of functional SNPs could be an important factor in increasing the sensitivity of association tests. Different bioinformatics approaches have been focused mainly on the effect of coding SNPs, but also recently on SNPs affecting the regulation or the splicing of genes (14).

PupasView is the first tool that integrates both transcriptional and translational phenotypic effects caused by polymorphisms. It provides an interactive environment in which functional information and population frequency data can be used over LD parameters as sequential filters to obtain a final list of SNPs optimal for genotyping purposes.

PupasView is closely linked to our previous program PupaSNP (14), which is a tool for selecting SNPs with putative phenotypic effects. PupaSNP, designed for high-throughput experiments, has been used to design >9000 sets of SNPs, and has a daily average of 50 uses. PupasView assists in the last refinement step of gene-by-gene selection of SNPs. Figure 1 illustrates the effect of applying successive filter steps, which are, conceptually, first to select only those SNPs which are real (with reported population frequencies) and then to select only functional SNPs. In the last view (Figure 1C), LD parameters can be used to help in the final selection.

More than 5000 SNPs have been selected using PupaSNP and PupasView in the first step of the pipeline for the study of polymorphisms at the Spanish National Genotyping Centre (CeGen).

Acknowledgments

L.C. and this work are supported by grant PI020919 from the FIS. J.M.V. is supported by the FPU fellowship programme from the MEC. This work is also partly supported by a grant from the Fundació La Caixa and the Fundación Ramón Areces. The Functional Genomics and Structure and Modelling nodes of the INB are funded by the Fundación Genoma España. CeGen, also funded by the Fundación Genoma España, is currently using the PupaSNP and PupasView programs for high-throughput SNP selection. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Fundación Genoma España.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Collins F.S., Green E.D., Guttmacher A.E., Guyer M.S. A vision for the future of genomics research. Nature. 2003;422:835–847. doi: 10.1038/nature01626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Risch N.J. Searching for genetic determinants in the new millennium. Nature. 2000;405:847–856. doi: 10.1038/35015718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Botstein D., Risch N. Discovering genotypes underlying human phenotypes: past successes for mendelian disease, future approaches for complex disease. Nat. Genet. 2003;33:228–237. doi: 10.1038/ng1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badano J.L., Katsanis N. Beyond Mendel: an evolving view of human genetic disease transmission. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002;3:779–789. doi: 10.1038/nrg910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strittmatter W.J., Saunders A.M., Schmechel D., Pericak-Vance M., Enghild J., Salvesen G.S., Roses A.D. Apolipoprotein E: high-vidity binding to beta-amyloid and increased frequency of type 4 allele in late-onset familial Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:1977–1981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hugot J.P., Chamaillard M., Zouali H., Lesage S., Cezard J.P., Belaiche J., Almer S., Tysk C., O'Morain C.A., Gassull M., et al. Association of NOD2 leucine-rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature. 2001;411:599–603. doi: 10.1038/35079107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sunyaev S., Ramensky V., Koch I., Lathe W., Kondrashov A.S., Bork P. Prediction of deleterious human alleles. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;10:591–597. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.6.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ng P.C., Henikoff S. Predicting deleterious amino acid substitutions. Genome Res. 2001;11:863–874. doi: 10.1101/gr.176601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller M.P., Kumar S. Understanding human disease mutations through the use of interspecific genetic variation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:2319–2328. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.21.2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chasman D., Adams R.M. Predicting functional consequences of non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms: structure-based assessment of amino acid variation. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;307:683–706. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerois R., Nielsen J.E., Serrano L. Predicting changes in the stability of proteins and protein complexes: a study of more than 1000 mutations. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;320:369–387. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00442-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrer-Costa C., Orozco M., de la Cruz X. Characterization of disease-associated single amino acid polymorphisms in terms of sequence and structure properties. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;315:771–786. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrer-Costa C., Orozco M., de la Cruz X. Sequence-based prediction of pathological mutations. Proteins. 2004;57:811–819. doi: 10.1002/prot.20252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conde L., Vaquerizas J.M., Santoyo J., Al-Shahrour F., Ruiz-Llorente S., Robledo M., Dopazo J. PupaSNP Finder: a web tool for finding SNPs with putative effect at transcriptional level. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W242–W248. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hudson T.J. Wanted: regulatory SNPs. Nat. Genet. 2003;33:439–440. doi: 10.1038/ng0403-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan H., Yuan W., Velculescu V.E., Vogelstein B., Kinzler K.W. Allelic variation in human gene expression. Science. 2002;297:1143. doi: 10.1126/science.1072545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prokunina L., Castillejo-Lopez C., Oberg F., Gunnarsson I., Berg L., Magnusson V., Brookes A.J., Tentler D., Kristjansdottir H., Grondal G., et al. A regulatory polymorphism in PDCD1 is associated with susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus in humans. Nat. Genet. 2002;32:666–669. doi: 10.1038/ng1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoogendoorn B., Coleman S.L., Guy C.A., Smith K., Bowen T., Buckland P.R., O'Donovan M.C. Functional analysis of human promoter polymorphisms. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:2249–2254. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colapietro P., Gervasini C., Natacci F., Rossi L., Riva P., Larizza L. NF1 exon 7 skipping and sequence alterations in exonic splice enhancers (ESEs) in a neurofibromatosis 1 patient. Hum. Genet. 2003;113:551–554. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-1009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cartegni L., Chew S.L., Krainer A.R. Listening to silence and understanding nonsense: exonic mutations that affect splicing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002;3:285–298. doi: 10.1038/nrg775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krawczak M., Reiss J., Cooper D.N. The mutational spectrum of single base-pair substitutions in mRNA splice junctions of human genes: causes and consequences. Hum. Genet. 1992;90:41–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00210743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kel A.E., Gössling E., Reuter I., Cheremushkin E., Kel-Margoulis O.V., Wingender E. MATCH: a tool for searching transcription factor binding sites in DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3576–3579. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wingender E., Chen X., Hehl R., Karas H., Liebich I., Matys V., Meinhardt T., Prüss M., Reuter I., Schacherer F. TRANSFAC: an integrated system for gene expression regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:316–319. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stabenau A., McVicker G., Melsopp C., Proctor G., Clamp M., Birney E. The Ensembl core software libraries. Genome Res. 2004;14:929–933. doi: 10.1101/gr.1857204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goni J.R., de la Cruz X., Orozco M. Triplex-forming oligonucleotide target sequences in the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:354–360. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altschul S.F., Madden T.L., Schaffer A.A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D.J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartz S., Kent W.J., Smit A., Zhang Z., Baertsch R., Hardison R.C., Haussler D., Miller W. Human–mouse alignments with BLASTZ [Erratum (2004) Genome Res., 14, 786.] Genome Res. 2003;13:103–107. doi: 10.1101/gr.809403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barrett J.C., Fry B., Maller J., Daly M.J. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gabriel S.B., Schaffner S.F., Nguyen H., Moore J.M., Roy J., Blumenstiel B., Higgins J., DeFelice M., Lochner A., Faggart M., et al. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science. 2002;296:2225–2259. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang N., Akey J.M., Zhang K., Chakraborty R., Jin L. Distribution of recombination crossovers and the origin of haplotype blocks: the interplay of population history, recombination and mutation. Am. J. Hum. Gen. 2002;71:1227–1234. doi: 10.1086/344398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The International HapMap Consortium. The International HapMap Project. Nature. 2003;426:789–796. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]