Abstract

Background

Multiple studies have shown that spouses of people with dementia (PwD) are two to six times more likely to develop dementia compared to the general population. Encouraging healthy behaviours and addressing modifiable risk factors could potentially prevent or delay up to 40% of dementia cases. However, little is known about how health behaviours change when a spouse assumes the role of primary caregiver. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore the shared lived experience of spousal caregivers of PwD, focusing on identifying the trajectory and key events of that shape health behaviour changes after their partner’s diagnosis. These findings seek to inform strategies for adopting and sustaining healthy behaviours among spousal caregivers.

Method

A qualitative descriptive study was conducted. Using maximum variation and purposive sampling, 20 spouses of PwD who exhibited two or more risk factors were recruited for semistructured interviews. The interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analysis.

Results

We found that in traditional Chinese culture health behaviour changes for spouses and people with dementia coping with the challenges of dementia occurred in two directions; (a) priming-leaping-coping: becoming a “smart” caregiver and (b) struggling-trudging-silence: the process by which the self is “swallowed.”

Conclusion

This study highlights how caregiving experiences influence spouses’ health behaviors and dementia prevention, particularly in the Chinese context. The findings underscore the challenges of balancing caregiving with self-care. Culturally tailored, family-centered interventions are needed to support both caregivers and their long-term well-being.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12912-024-02588-3.

Keywords: Dementia, Risk factors, Spouses, Health behaviour, Qualitative studies

Introduction

Dementia is a pressing global public health issue, with over 55 million people currently living with the condition, a figure projected to reach 152 million by 2050 due to the aging population [1]. The burden of dementia extends beyond individuals to families, caregivers, and society, creating significant economic and emotional challenges. Slowing the onset of dementia has thus become a critical global health priority [2]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), adopting healthy behaviours and addressing modifiable risk factors across the life course could prevent or delay up to 40% of dementia cases worldwide [3, 4].

China, home to the largest number of people with dementia (PwD), accounts for 25% of the global dementia population [5, 6]. This immense burden has profound implications for Chinese families and society. Rooted in cultural traditions that emphasize filial piety and family responsibility, China’s care model predominantly relies on family-based caregiving [7]. Over 80% of PwD in China receive care at home, with spouses being the primary caregivers in 51.9% of cases [8]. Spousal caregivers are particularly vulnerable, with research showing they are several times more likely to develop dementia themselves compared to the general population [9–11]. This heightened risk is attributed to shared lifestyle factors, such as low physical activity and excessive alcohol consumption, as well as the physical and emotional toll of caregiving [12].

Older spousal caregivers, with an average age of 58 years (58.0 ± 12.0 years), face an even greater risk of cognitive decline [4, 13, 14]. Although a growing body of qualitative research has explored spousal caregivers’ experiences, such as adjusting to life changes and adapting to caregiving roles [15, 16], these studies primarily focus on caregiving experiences [17], quality of life [18], and mental health [19]. Spousal caregivers’ own health behaviours and their role in mitigating dementia risk remain underexplored. It has been reported that spousal caregivers often prioritize the needs of their partners, neglecting their own health [20, 21]. Furthermore, their attitudes toward dementia prevention are shaped by their indirect experiences of dementia and caregiving [22].

Globally, large-scale intervention studies targeting modifiable risk factors for dementia prevention have shown promise [23]. However, these programs are predominantly based on Western guidelines, which may not align with the geographical, economic, and cultural contexts of Chinese populations. While such interventions have achieved small but significant improvements in dementia risk and cognitive outcomes, gaps remain regarding how health behaviour changes translate into a reduced perception of dementia risk [24]. Additionally, little is known about the trajectories of health behaviour changes in high-risk populations and the drivers influencing these changes [25].

To address these gaps, this study aims to explore the lived experiences of Chinese spousal caregivers of PwD, mapping the trajectories of their health behaviour changes after their partner’s diagnosis. By identifying key events driving these changes within the context of traditional Chinese culture, the findings will provide evidence-based insights to inform culturally tailored dementia prevention programs for spousal caregivers, a population at high risk of dementia.

Methods

Study design

A descriptive approach was employed in this study, guiding researchers to seek, discover, and understand a phenomenon, a process, or the views and worldviews of related people. This method encouraged researchers to analyse the research phenomenon to produce more objective and truthful results [26, 27]. The research was reported in accordance with the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) 32-item checklist [28].

Study site and sample

The study was conducted from December 2021 to July 2022 in the memory clinic of a large hospital in Northeast China, a deeply ageing region (15.61% ≥65 years) [29]. Maximum variation sampling and purposive sampling were used to recruit eligible spouse caregivers [30], ensuring diversity in age, gender, education level, and place of origin, and there were differences in the number of years of caregiving and the severity of the partner’s dementia to ensure that the results of the study included a maximum coverage of different situations in the study phenomenon: (a) had two or more risk factors for dementia, midlife and late-life dementia risk factors in the life-course model included hearing loss, traumatic brain injury, hypertension, excessive alcohol consumption, obesity, smoking, depression, social isolation, physical inactivity, diabetes, and air pollution [3], as defined in the Supplementary 1. (b) were ≥ 45 years of age, considering the life-course model of risk factors for dementia and the average age of spousal caregivers (58.0 ± 12.0 years) (c) provided care for ≥ 6 months, and (d) agreed to participate in this study. Spouse caregivers who were unable to communicate or whose ill patients were unconscious were considered ineligible for inclusion in the study.

Prior permission was obtained from nursing managers at the participating hospitals, who provided a contact list of potential spouse caregivers caring for partners with dementia. The researchers then verified the patients’ diagnoses and confirmed the eligibility of the spouse caregivers with the assistance of doctors. Caregivers meeting the inclusion criteria were given an explanatory statement detailing the study’s aim and procedures. The statement emphasized that participation was voluntary and that participants could withdraw at any time without providing a reason. Researchers continuously monitored the sample size to determine the point of saturation [31].

Data collection

Before conducting the interviews, the primary researcher (Shuyan Fang, during clinical placement) spent six months in the memory clinic observing and communicating with PwD, their spouse caregivers, clinicians, and nurses to gain a deeper understanding of the couples’ living conditions. To ensure consistency, all interviews were conducted by this researcher.

Two spouse caregivers participated in pre-interviews, which informed revisions to finalize the interview outline (Table 1). During the face-to-face, semi-structured interviews, participants were encouraged to speak freely about their experiences, providing as much detail as possible. For instance, when a spouse caregiver stated, “I think I live a healthy life now,” the interviewer followed up with, “What do you think is healthy?” [32]. Observations of body language, tone, expressions, and movements were recorded to retain the interview’s original style and content. The interviews, lasting between 42 and 85 min, were audio-recorded, and reflective memos documenting the researcher’s experiences during the interviews were added (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Semi-structured interview guide summary

| Number | Main focus |

|---|---|

| 1 | How much do you know about your wife/husband’s current dementia-related symptoms and living conditions? |

| 2 | During the time after your wife’s/husband’s diagnosis, did you think about your own health and what you did? |

| 3 | Do you think dementia can be prevented? What do you know about the risk factors for dementia? |

| 4 | What did your learn about dementia prevention after your wife/husband was diagnosed? |

| 5 | Can you name some healthy behaviors in your daily life that you think can reduce the risk of dementia? |

| 6 | Can you tell me some about what you usually do about these healthy behaviors? |

| 7 | Do you consider yourself to be living a healthy lifestyle? Which are healthy and which are unhealthy? |

| 8 | Have your perception of your own risk of dementia changed when your wife/husband has dementia? Did you seek support and help? |

| 9 | What habits and lifestyle did you change? Why? What happened along the way or is there anything you’d like to share with me? |

| 10 | Did these changes stick? If not, why not? |

| 11 | What factors do you think hinder or promote your prevention of dementia? |

| 12 | What kind of support do you expect? Do you have any comments or suggestions on existing support and policies? |

Fig. 1.

Reflective memo sample. Reflective memos were added detailing the researcher’s experiences during the interviews and how these may have influenced the findings, conclusions and interpretations of the study

Data analysis

The interviews were concurrently transcribed verbatim in Chinese by the first author (Shuyan Fang) and independently verified by the third author (Shizheng Gao) within 24 h. Data analysis followed Braun and Clarke [33] methods help to distinguish, identify and interpret themes. This subprocess is guided by the research question: What experiences and beliefs drive health behaviour changes in spouse caregivers?

To begin, they immersed themselves in the data by reading and rereading the transcripts to familiarize themselves with the depth and breadth of the content. Key paragraphs containing relevant information about changes in spouse caregivers’ health behaviours were labeled, identifying important statements. In the next phase, initial codes were grouped into potential themes. The authors debated their meanings and emerging patterns, aiming to reach a consensus. Relevant coded data extracts were then collated within the identified themes, and mind maps were created to organize the themes meaningfully. The identified themes were reviewed, refined, and defined to capture their individual and collective essence. Finally, the research team held meetings to discuss the analysis results, ensuring they were accurate and comprehensive while enhancing the credibility and validity of the findings. Data analysis was conducted using NVivo 12 qualitative data analysis software [34](NVivo qualitative data analysis software; QSR International Pty Ltd., Version 12, 2018).

Key themes and quotes in Chinese were translated into English by the first author, with the third author reviewing the translation and back-translation process to ensure accuracy, truthfulness, and completeness [35]. All members of the research team reviewed the translated data, discussing and analyzing the results until a consensus was reached. A detailed explanation of the analysis process is provided in Supplementary 2.

Rigour

Credibility: The researchers listened to the recordings multiple times, compared and analyzed the data against the results, and presented their findings to peers for feedback.

Dependability: All team members had experience in geriatric care and qualitative research, with one author being a professor of geriatric nursing. The researchers also received comprehensive theoretical training.

Confirmability: The researchers maintained objectivity throughout the data collection process, ensuring fairness and interpreting the data based solely on what was observed and heard.

Transferability: This study provides a transparent and detailed description of the data analysis process, along with comprehensive interview results, offering valuable insights for future research in similar contexts.

Ethical considerations

This study followed the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Nursing School of Jilin University (approval number 2021121504). Only the researchers had access to the digital audio recordings and transcripts. All spouse caregivers were provided with both verbal and written information about the study and gave their explicit, written consent to participate. Before the interviews, participants were informed about the study’s purpose, methods, and confidentiality principles, and they signed informed consent forms. Additionally, interview content was randomly numbered based on the order of interviews, and citations were used in the Findings section to ensure anonymity and confidentiality(Clinical trial number: not applicable).

Findings

The characteristics of the spouses and PwD

Data saturation was deemed reached at the 19th interview when no new code emerged from the data analysis. However, to ensure the thoroughness of the data collection, one additional interview was conducted, but it did not provide any new information or insights. The included 20 spouses ranged in age from 46 to 85 years, with an average age of 69.1 years. The duration of care ranged from 1 to 11 years, with an average of 3.8 years. All spouses had common chronic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes. Sixteen spouses took sole care of the patients(Table 2).

Table 2.

The characteristics of spousal caregivers in this study(N = 20)

| Characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 14 | 70 |

| Male | 6 | 30 |

| Age range (years) | ||

| 46–55 | 4 | 20 |

| 56–65 | 4 | 20 |

| 66–75 | 10 | 50 |

| 76–85 | 2 | 10 |

| Education | ||

| Secondary education level | 12 | 60 |

| Elementary school and below | 8 | 40 |

| Care alone a | ||

| Yes | 4 | 20 |

| No | 16 | 80 |

| Duration of caregiving (years) | ||

| 1–5 | 16 | 80 |

| 6–11 | 4 | 20 |

| Health status b | ||

| good | 11 | 55 |

| poor | 9 | 45 |

a, Care alone, Spouses report sole caregiver responsibilities

b, Health status, Subjective assessment based on spouse self-reports

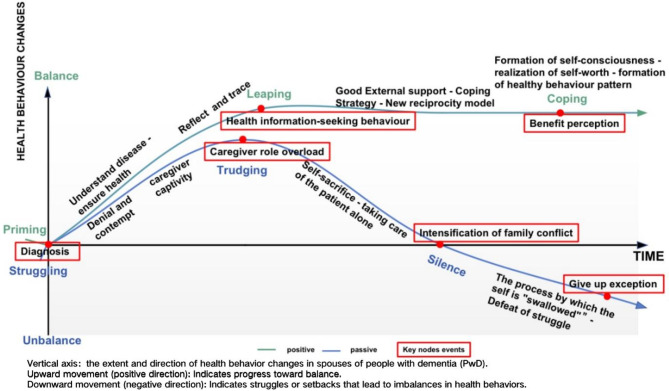

This study identified two major themes and six subthemes through thematic analysis, defining critical node events as pivotal moments that prompt the next phase of a spouse’s health behaviour changes. Influential factors such as caregiver load, shifts in the couple’s relationship, social expectations, cultural values, and the spouse’s health behaviours reveal a dynamic process of continuous development and change following the partner’s dementia diagnosis.

The impact of dementia on spouses’ health behaviours was observed to follow two distinct trajectories: positive changes, characterized by progress toward balance, and negative changes, marked by increased imbalance. The vertical axis in our analysis represents the extent and direction of these health behaviour changes. It illustrates the balance or imbalance experienced by caregivers as they navigate caregiving challenges and adjust their behaviours over time (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Trajectory of health behaviour changes in spouses of PwD. Figure 2 summarizes the trajectory of spouses’ health behavior changes and phased node events after the diagnosis of patients

Priming-leaping-coping: becoming a “smart” caregiver

The positive development of healthy behaviours was a dynamic process in which the spouse continually adjusted to life with the PwD, striving to re-establish balance while maintaining active participation in daily life.

Priming: start taking care of one’s own health

Spouses shared the process through which they first became aware of dementia and recognized that their partner had the condition. Initially, the spouse passively assumed the caregiving role, prompted by the onset of the illness. Often, it is a life event or a noticeable change in the PwD’s mental or behavioural state that forces the spouse to recognize the severity of the situation.

“One day, he drove our grandson to school, forgot about us and went home on his own, I realized that something seemed to be wrong with him.” (Spouse 01).

“She started to talk about one thing over and over again, and then, after a couple of days, she’d bring it up again.” (Spouse 06).

The influence of authority played a significant role in the spouse’s subconscious, with respondent placed great value on and trusted the advice provided by healthcare professionals.

“She forgot things so badly that after washing her face in the morning, she just stood there and didn’t know what to do. The doctor said that it was Alzheimer’s disease.” (Spouse 02).

After learning of an incurable and serious health issue in their partner, spouses began to confront dementia and become deeply concerned about their own health.

“The doctor said the disease was related to many factors, so I thought I’d get checked as well because I had a poor memory since I was young.” (Spouse 10).

One spouse described the importance of understanding dementia, acknowledging that the disease would become a part of their life and that learning about it early could help prepare for long-term life adjustments.

“I think you have to understand the disease first. It’s not just the one who got sick. I’m the primary caregiver… I’m going to be ready for my future; this disease is not like other diseases, and once you accept it, you can move on, that’s what I’ve summed up. If you try to fight it, you will always be in chaos. " (Spouse 09).

“In order to take care of him, I have to take care of my health”. (Spouse 13) Spouses were aware of and accepted their role as caregivers, recognizing that the nursing demands for their loved ones would escalate as the disease advanced, presenting greater challenges. Their sense of responsibility toward their family often motivated spouses to maintain their own health; they viewed themselves as vital to the family and feared that illness would either place a burden on their children or others. As a result, these concerns acted as strong signals for spouses in poor health, urging them to address their physical and mental well-being. The spouse caregivers emphasized that regular checkups and a healthy lifestyle were key strategies they believed could reduce the risk of dementia. Traditional Chinese health practices were particularly popular among middle-aged and older spouses due to their simplicity and ease of integration into daily routines.

“I have hypertension and diabetes, and now I have to take care of him, so I need to be even more cautious about my health; I’m afraid that if I get sick, I won’t be able to care for him in the future. " (Spouse 13).

“I often watch that health programme on TV, especially for this disease, expert guidance on diet, balancing yin and yang, soaking feet every night, massage points, and tips like how to eat in winter to replenish qi and blood…” (Spouse 05).

Leaping: sensitive disease risk perception and control

Spouses observed a gradual decline in their partners’ health and cognitive abilities. The progressive loss of independence in PwD, combined with the emergence of abnormal psychological and behavioural symptoms, triggered fear and anxiety in their spouses about their own future and the possibility of developing the same condition. Recognizing and managing dementia-related risk factors became essential for spouses as they sought to navigate and mitigate the impact of the disease. This process led spouses to reflect on their own health conditions and identify lifestyle habits or behaviours that might increase their risk of dementia.

“I’m worried that I will get dementia too, I will not be able to take care of myself, and no one looks after him.” (Spouse 19).

“Before she got sick, our family ate more salt and meat, I don’t pay attention to, I always think that now that our living conditions are better, I can eat whatever I want…” (Spouse 02).

“I think it has a lot to do with personality; he is introverted and not socializing.” (Spouse 16).

At this stage, spouses demonstrated active health information-seeking behaviours, marking a critical turning point. After evaluating their own health risks and identifying potential causes, they proactively sought external information and support. This effort aimed to build a more comprehensive understanding of their situation and develop strategies to prevent the onset and progression of dementia.

“We have a patient group with doctors, I always ask questions, and we share knowledge about dementia. I learn a lot.” (Spouse 03).

After becoming spouses of PwD, respondents prioritized dementia prevention, diagnosis, and care, as well as seeking authoritative guidance and assessing their own risk of developing the disease. The sources of health information they relied on significantly shaped their health behaviours and outcomes. Over time, respondents subconsciously integrated these health behaviours into their daily routines, transforming them into habitual practices.

“Last time at the community activity focusing on dementia, we received a brochure; we now walk every day to ensure that we get some exercise, meat and vegetables. I sometimes take her to her sister’s home. I take my blood pressure medication regularly; so does she.” (Spouse 04).

“I quit smoking… I’m drinking less alcohol.” (Spouse 06).

Support from the external environment played a crucial role. When spouses had access to a supportive network that acknowledged their contributions, fostered a sense of control over their caregiving role, and promoted positive relationship dynamics with family and friends, they were more likely to develop a positive outlook. This engagement in their caregiving role enhanced their sense of self-actualization and boosted their confidence in managing daily challenges.

In traditional Chinese collectivist culture, strong family and social support networks provide spouses with personal time while clearly defining and balancing complementary roles and responsibilities. This shared management of family affairs fosters a sense of unity and cooperation among family members.

“There are a lot of people in our family who are well-connected; my nephew accompanies him to his training… so I don’t have to worry about it. " (Spouse 19).

“I can talk to my friends, and it’s much easier. My sister helps me look after him. I can go out and have dinner with friends, and enjoy some time for myself.” (Spouse 05).

The optimization of the quality of medical services and the introduction of social welfare policies both slowed the progression of the patient’s condition and, more importantly, “relieved” the spouse.

“Now, she is doing cognitive training, and she is a little better. It also makes things much easier for me when she does the training, as I can do things on my own… Additionally, the medicine this year is covered by health insurance, which saves a lot of money.” (Spouse 02).

Coping: adapting to a new normal and developing healthy behaviour patterns

Spouses identified the perceived benefits of healthy living as their primary motivation. With an increasing understanding of risks associated with the disease and ongoing self-adjustment, they gradually adapted to view both caring for the patient and caring themselves as part of their new normal. This adaptation enabled spouses to maintain positive health behaviours, ultimately achieving a stable and sustainable state in which they could build a fulfilling and meaningful life for themselves.

The caregiving journey was a continuous learning process characterized by observation and repeated “trial and error.” This process fostered personal growth and resilience, helping spouses become stronger and more adaptable individuals. Developing a deeper understanding of the illness and reflecting on caregiving challenges allowed spouses to recognize positive aspects of the relationship. “Being able to joke and laugh together makes caring meaningful”. Additionally, the loss of supportive relationships compelled spouses to become more independent and take on greater caregiving responsibilities.

“I like to reminisce with him about the past, which he remembers so well, or talk about when our kids were little; that’s when he was emotionally stable, and both of us were happy. (laugh)” (Spouse 01).

“I’m so good now that I can take him to the doctor independently, and I know all the effects of his medicine.” (Spouse 14).

After gradually adapting to their new life, spouses began venturing outside their homes and actively reintegrating into society. A new model of reciprocity with PwD emerged, wherein spouses found that the caregiving process provided meaningful benefits for their own well-being. This positive dynamic fostered a virtuous circle, encouraging spouses to adopt healthier lifestyles.

“I now insist on going to the community centre and taking him most of the time, chatting to neighbours”. (Spouse 05)

“Since she has been ill, our family has eaten healthily; we used to know about this, we just couldn’t change it, but now that she is ill, we changed.” (Spouse 12).

“He exercises, so do I, all synchronized, better together.” (Spouse 10).

As spouses continuously adjusted to their new lifestyle, they found a balance between caring for their loved ones and attending to their own needs, resulting in a notable increase in self-awareness. Seeking the positive meaning in life and caregiving through social interactions helped spouses alleviate associated pressures, enhanced their sense of self-identity, and fostered a stronger sense of belonging within their family and social life. Additionally, the patient’s reliance on the spouse provided a sense of empowered. Spouses perceived their role as highly valuable, which further reinforced their sense of self-worth.

“I am so satisfied now; I feel like a better and more complete person, which helps me keep balance. I started to focus on my own feelings; I have to be healthy. I made it through.” (Spouse 03).

Struggling-trudging-silence: the process by which the self is “swallowed”

Spouses described the development of their own unhealth behaviours and the disruption of positive health practices as resulting from their inability to cope with the demands of caregiving. This was characterized by a severe imbalance between attending to their own needs and prioritizing the care of the PwD, ultimately leading to a life where the PwD’s needs took complete precedence. Spouses reported neglecting their own health and experiencing a gradual transition into the role of an “invisible” caregiver.

Struggling: denial and contempt

Some spouses demonstrated limited cognitive reserves, held stereotype views of dementia, believed it was neither preventable nor linked to daily health behaviours, or had an incomplete understanding of its risk factors.

“You live a regular life and have a healthy routine; eating well and getting enough sleep are definitely good for your health, but I’m a bit doubtful that you can prevent dementia. I’m somewhat sceptical; the disease is very complex(shake head).” (Spouse 01).

However, regarding their perceptions of the relationship between poor health behaviours and dementia, spouses generally acknowledged that lifestyle could influence the development of the disease. Despite this recognition, most spouses still had an incomplete understanding of risk factors. This limited awareness led them to believe that maintaining good habits in one aspect of their lives was sufficient, while neglecting other important health behaviours.

“I think exercise is the most important thing to stay healthy. …… I’ve never really paid attention to that. I eat more meat and fewer vegetables.” (Spouse 02).

Healthy check-ups could also have a “qualifying effect,” fostering to the belief that as long as the results were favorable, there was less need for spouses to prioritize and maintain health behaviours.

“We have yearly medical check-ups, and there’s nothing wrong with me except that my blood pressure and blood sugar are a bit high, as they are at this age. I don’t think I can get it for sure.” (Spouse 06).

Trudging: self-efficacy is reduced

When the caregiver load exceeded the spouse’s psychological threshold and feelings of caregiver captivity or role overload emerged, the trajectory of the spouse’s health behaviours shifted in a negative direction. Interviewees reported struggling to find meaning in the roles they were taking on, while negative influences from various sources continuously disrupted their lives, leaving them with little to no time to prioritize their own health.

“I’m like a wind-up machine; his condition is becoming more and more serious. I really can’t control it; you can’t treat him like a prisoner, but I feel like I’m the one becoming a prisoner.” (Spouse 19).

More importantly, the value of self-sacrifice promoted by traditional Chinese culture instilled in the respondents the mindset to “keep going.” Spouses described the conflict between meeting social expectations and prioritizing their own health. They often felt as though they were wading through the “mud” of caregiving, simultaneously balancing the roles of caregiver and parent. To avoid burdening their children, spouses chose to take on all caregiving responsibilities alone.

“There’s no way I’m leaving him behind; what would people think of our family? It’s not fair to the kids and him, so you just have to accept it, really.” (Spouse 05).

Almost all the interviewees mentioned “loneliness,” which was partly attributed to their difficulty in communicating with PwD. Additionally, several factors, including the spouse’s age, poor health, the stigma surrounding dementia care, fear of being misunderstood, led to a narrowing of their social networks.

“I used to love having my friends over. I haven’t done that since he got sick. He’s unstable.” (Spouse 03).

Simultaneously, the intensification of family conflicts posed a significant external challenge for spouses. Interviewees expressed that the progressive worsening of dementia resulted in a decline in positive feedback between spouses: “I miss the old him.” A strong couple relationship was identified as a key factor in maintaining quality of life and preventing negative outcomes. Couples felt sorrow over the loss of intimacy and cohesion, perceiving that, in many ways, the relationship had become unequal, with the caregiver-patient dynamic taking over their lives.

“It’s been almost 50 years-two people who have overcome so many stumbles together, only to be defeated by this disease. The relationship is gone, and I’m definitely a bit depressed. (bang on the desk)” (Spouse 04).

“It’s only with the closest people that he shows his temper; he’s always polite to others, when I tell people about that terrible state he’s in at home, they don’t believe, no one believes me, that’s the hardest part of it. (sigh)” (Spouse 01).

Additionally, the intensification of conflicts within the extended family, unclear divisions of labour among family members, and mutual blame further heightened the psychological pressure on spouses. Negative emotions impacted the couple’s daily life, reduced their quality of life, hindered health behaviours, and increased the risk of disease.

“You can’t predict the pattern of good days and bad days. His relatives would say I didn’t take good care of him (cry).” (Spouse 07).

Silence: defeat in the face of struggle

After repeatedly struggling to maintain balance, spouses gradually became demoralized. They realized that, despite their efforts, they fell short of expectations. This led them to abandon the attempt to maintain balance and adopt a lifestyle that entirely prioritizes the PwD. Spouses invested significant effort into this caregiving role, sacrificing work and social activities to actively engage in the relationship. However, this situation lacked reciprocity and mutual support, and as a result, the giving role gradually lost its momentum. The stress of living caregiving eroded the spouse’s sense of a predictable and controllable future.

“I had to think about everything; I had never done these things before, and I felt like my brain was stuck, so I just gave up and resigned myself to it.” (Spouse 17).

Discussion

The findings of this study support the dementia risk factor life course model [3], emphasizing the continuous and dynamic nature of health behaviour transformations in spouses of PwD. This research highlights that balancing multiple roles effectively is crucial for spouses to adapt to caregiving demands while maintaining their own health. Key events, such as the onset of dementia, active health information-seeking behaviours, and perceived benefits of healthy practices, were identified as drivers of positive health behaviour changes. However, significant challenges, including caregiving stress, role overload, and cultural expectations, create barriers to sustaining healthy behaviours.

The realization that the partner’s living situation is severely impacted by the disease prompted respondents to recognize the seriousness of the condition and begin focusing on their own health. Similar to a study in Turkey, those with family members with dementia were more likely to have greater motivation to modify their lifestyle (perceived susceptibility, severity, benefits, and cues to action) to reduce their risk of developing dementia [36]. Access to external support enriches spouses’ cognitive reserve and heightened their awareness of dementia risk. Unlike in Western contexts, where external caregiving support systems are more accessible, the reliance on family-based care in China amplifies the emotional and physical burdens on spouses [37]. Solidarity and cooperation within the family are key to support positive healthy behaviours in caregivers and should be prioritized. Family dynamics play an essential role in enhancing the psychological resilience of caregivers, while family cohesion provides much-needed respite [38, 39]. Families, as ecosystems for cultivating healthy behaviours, and couple relationships, in particular, help both partners maintain emotional connections that reinforce the belief in an active life [40]. The intimacy and sense of responsibility within couples foster strength, often described as “sharing joys and sorrows” [41]. Previous research has shown that, improvements in “caregiving confidence” and “caregiving insight” are critical in enabling caregivers to adapt to their roles, rebuild self-perception, and establish a sense of self-worth, ultimately achieving a “new balance” in life [42, 43]. Additionally, often derive satisfaction and resilience from their altruistic values, as these align with their life principles and allow them to find strength in overcoming challenges [44]. However, findings from a nationwide survey in Spain presented a contrasting perspective. Spanish caregivers, while holding familistic beliefs and placing family at the center of their lives, reported difficulties in meeting family expectations, which exacerbated stress and depressive symptoms [45].

As the PwD’s illness progresses, spouses face significant challenges in maintaining balance in their lives. The worsening condition of their partner often results in increased external pressures, such as reduced income and heightened social isolation, whereas negative emotions such as anxiety and depression in the care process and attachment insecurity lead to changes in the vulnerability of individuals within the binary. In turn this leads to a positive or negative binary relationship adaptation process that affects the health behaviours of spouses [46]. A review found that, compared to other regions, dementia caregivers in Asia often juggle multiple roles within their work and family lives. When these roles conflict with their caregiving responsibilities, they feel unable to meet the expectations of any role effectively [47]. In contrast to our study, in some Western countries, such as Canada, some middle-class white men do not perceive themselves as caregivers but rather view their caring as a reinforcement of their role as a husband, placing a greater emphasis on their own sense of self [48]. However, Chinese caregivers often perceive caregiving as a moral duty. As shown in many Chinese studies, some caregivers are reluctant to place their relatives with dementia in nursing homes due to cultural norms prioritizing family care [49]. Spouses face immense pressure to fulfill the social expectations of being a supportive partner, dedicated caregiver and responsible. This pressure often forces them to make trade-offs and sacrifices to meet these competing demands. Engaging in healthy behaviours, such as socializing and exercising, becomes challenging as time is often prioritized for caregiving tasks [17]. A significant barrier for caregivers is their reluctance to acknowledge or address their own needs. Nordtug et al. [50] discovered that some informal caregivers noted a concerning issue within their primary support network: some individuals did not believe that the person with dementia was ill. This lack of belief or the reception of criticism can represent a significant burden for caregivers. Additionally, other members within their network chose to withdraw as a deficiency in social support is associated with a decline in mental health. To overcome these challenges, municipal healthcare services might consider establishing regular opportunities for informal caregivers to engage in dialogue with other informal caregivers of individuals with dementia. A series of studies conducted in the Netherlands developed the notion of a “partner in balance,” which effectively improved the self-efficacy, quality of life and experience control of family caregivers [51, 52].

Notably, some caregivers equated their risk of developing dementia with being diagnosed as ill, which led to resistance toward accessing information about dementia risk. This behaviour may stem from the shame and stigma surrounding dementia within Chinese cultural context. A review suggested that much of the research on family stigma has focused on Asian countries, with Chinese culture emphasizing collectivism [53]. Consequently, the impact of affiliate stigma on Chinese family caregivers is obviously greater. Additionally, middle-aged respondents in this study indicated that they felt it was too early to consider the risk of developing dementia. Future research shift the focus for this population toward maintaining optimal cognitive brain health rather than solely emphasizing dementia risk reduction [54]. As international policy on dementia shifts towards a prevention agenda, there is a growing interest in identifying individuals at risk of developing dementia. However, the introduction of proactive dementia identification raises complex practical and ethical issues, particularly in contexts with low public awareness of dementia [55]. This underscores the importance of providing high-quality information about dementia, including its likelihood and risk factors, along with psychological support for those undergoing risk assessments.

Consistent with previous research, the gender of caregivers has been shown to influence their caregiving experiences [46]. Under the influence of traditional culture norms, female caregivers usually view caregiving as an extension of their established family responsibilities, enabling them to cope more easily. In contrast, male caregivers tend to perceive caregiving as a persistent stressor, leading to increased anxiety. Female caregivers are more likely to express their stress openly and seek external support to manage challenges [56]. Therefore, various coping skills to maintain life balance have also emerged in the context of caregiving. In this study, female caregivers commonly employed specific strategies to promote shared health behaviours, such as walking together with PWDs. Male caregivers, on the other hand, are more likely to maintain preexisting health behaviours, such as engaging in social participation and outdoor activities, often reflecting routines from their previous work experiences. These findings concerning gender differences should prompt healthcare professionals’ attention in designing tailor-made caregiver education programmes in family nursing in managing stress and maintaining life balance.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, all participants were recruited from the memory clinic of the same hospital, which may have introduced selection bias and limited the perspectives to spouses who actively sought medical care for their partners. This could exclude the views of spouses who manage caregiving without accessing clinical services, potentially affecting the generalizability of the findings. However, it is worth noting that the memory clinic network spans 28 regions in China, which provides a relatively broad representation of caregiving experiences within this healthcare system. Second, the study was conducted in the Northeast region of China, where the population has a high proportion of older adults due to significant aging demographics. Cultural and regional differences may influence caregiving behaviours and experiences, meaning that these findings may not fully reflect the diversity of spouse caregivers across China. Future studies employing a multicenter design could address this limitation by including a more diverse sample across various regions, socioeconomic backgrounds, and cultural contexts to enhance the generalizability of the results.

Conclusion

This study offers new insights into how the early caregiving experiences of spouses influence their health behaviours and dementia prevention practices. Under the influence of traditional cultural values, many spouses prioritize their caregiving responsibilities as a central part of their identity and sense of duty. This sense of mission shapes their approach to health behaviours, often creating a complex interplay between caregiving and self-care. The findings highlight the significant challenges spouses face in balancing multiple roles and maintaining their own health, particularly in the Chinese cultural context. These results contribute to the literature by emphasizing the unique experiences of Chinese spouses of PwD, including the cultural, social, and familial factors that influence their health behaviour decisions. Future interventions should address these dynamics to support caregivers in sustaining both their caregiving responsibilities and personal well-being.

Relevance for clinical practice

Assessing a spouse’s understanding of dementia is a critical step in designing effective intervention programes. While increasing knowledge about dementia is important, it alone may not be sufficient to drive sustained behaviour change. There remains a gap in understanding how the perceived benefits of healthy behaviours translate into reduced dementia risk. The life-course model of dementia risk factors emphasizes continuity in health behaviours over time. Long-term risk may have limited influence on immediate behaviour, highlighting the need for ongoing tracking, risk stratification, and interventions beginning early in life. Given the complex interplay of multiple risk factors, multifactorial interventions are essential to address the spiral interactions between these factors. Additionally, understanding the mechanisms and behavioural patterns that support dementia prevention at the family level is vital. Culturally tailored, family-centered dementia prevention programs spanning the life course should be developed to address these dynamics effectively. Such programs have the potential to support not only the individual but also the broader family unit, fostering a holistic approach to dementia prevention.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors listed meet the authorship criteria, the latest guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. All authors are in agreement with the manuscript. Jiao Sun and Shuyan Fang contributed to study conception and design of the study. Shuyan Fang and Shizheng Gao contributed to data collection. Shuyan Fang, Shizheng Gao and Dongpo Song contributed to the analysis as well as the writing and conceptualization of the manuscript. Yanyan Gu and Shengze Zhi reviewed the manuscript, Jiao Sun and Wei Li finalized the final version.

Funding

Key Laboratory of Geriatric Long-term Care (Naval Medical University), Ministry of Education (Grant. Number: LNYBPY-2023-20).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the declaration of Helsinki (ethical approval and consent to participate). This study was approved by the ethics committee of Jilin university (No:2021121504)(Ethics Committee of School of Nursing, Jilin University). The aims and methods of the project were explained to all participants, and necessary assurance was given to them about the anonymity and confidentiality of their information and audio files. Informed consent was taken from all participants. The participants had the right to withdraw from the study during or at any other time.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nichols E, Steinmetz JD, Vollset SE, Fukutaki K, Chalek J, Abd-Allah F, et al. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(2):E105–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jia J, Wei C, Chen S, Li F, Tang Y, Qin W, et al. The cost of Alzheimer’s disease in China and re-estimation of costs worldwide. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(4):483–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):413–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.International AsD. World Alzheimer Report 2022-Life after diagnosis: Navigating treatment, care and support. 2022 [ https://www.alzint.org/resource/world-alzheimer-report-2022/

- 5.Jia L, Du Y, Chu L, Zhang Z, Li F, Lyu D, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and management of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in adults aged 60 years or older in China: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(12):E661–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ren RJ, Qi JL, Lin SH, Liu XY, Yin P, Wang ZH et al. The China Alzheimer Report 2022. Gen Psychiatry. 2022;35(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Ma YY, Gong J, Zeng LL, Wang QH, Yao XQ, Li HM, et al. The effectiveness of a community nurse-led support program for dementia caregivers in Chinese communities: the Chongqing ageing and dementia study. J Alzheimers Disease Rep. 2023;7(1):1153–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiao J, Li J, Wang J, Zhang X, Wang C, Peng G et al. 2023 China Alzheimer’s disease: facts and figures. Hum Brain. 2023.

- 9.Yang HW, Bin Bae J, Oh DJ, Moon DG, Lim E, Shin J et al. Exploration of cognitive outcomes and risk factors for cognitive decline Shared by couples. Jama Netw Open. 2021;4(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Dassel KB, Carr DC, Vitaliano P. Does caring for a spouse with dementia accelerate cognitive decline? Findings from the Health and Retirement Study. Gerontologist. 2017;57(2):319–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pertl MM, Lawlor BA, Robertson IH, Walsh C, Brennan S. Risk of cognitive and functional impairment in spouses of people with dementia: evidence from the health and retirement study. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2015;28(4):260–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vitaliano PP. Exploration of risk factors for cognitive decline shared by couples and cognitive outcomes-assortative mating, lifestyle, and chronic stress. Jama Netw Open. 2021;4(12). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Wang L, Zhou Y, Fang XF, Qu GY. Care burden on family caregivers of patients with dementia and affecting factors in China: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Ai J, Feng J, Yu Y. Elderly care provision and the impact on caregiver health in China. China World Econ. 2022;30(5):206–26. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pozzebon M, Douglas J, Ames D. Spouses’ experience of living with a partner diagnosed with a dementia: a synthesis of the qualitative research. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28(4):537–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macdonald M, Martin-Misener R, Weeks L, Helwig M, Moody E, MacLean H. Experiences and perceptions of spousal/partner caregivers providing care for community-dwelling adults with dementia: a qualitative systematic review. Jbi Evid Synthesis. 2020;18(4):647–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tu J, Li H, Ye B, Liao J. The trajectory of family caregiving for older adults with dementia: difficulties and challenges. Age Ageing. 2022;51(12). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Kim J, Cha E. Effect of perceived stress on health-related quality of life among primary caregiving spouses of patients with severe dementia: the mediating role of depression and sleep quality. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(13). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Johansson MF, McKee KJ, Dahlberg L, Summer Meranius M, Williams CL, Marmstal Hammar L. Negative impact and positive value of caregiving in spouse carers of persons with dementia in Sweden. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Hampel S. Perception of health and health-related behavior of family caregivers of people with dementia. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;53(1):29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliveira D, Zarit SH, Orrell M. Health-promoting self-care in family caregivers of people with dementia: the views of multiple stakeholders. Gerontologist. 2019;59(5):e501–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim J, Kim MY, Kim JA, Lee Y. Factors affecting preventive behaviors of Alzheimer’s disease in family members of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Medicine. 2022;101(42). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Rohr S, Kivipelto M, Mangialasche F, Ngandu T, Riedel-Heller SG. Multidomain interventions for risk reduction and prevention of cognitive decline and dementia: current developments. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2022;35(4):285–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meng X, Fang S, Zhang S, Li H, Ma D, Ye Y, et al. Multidomain lifestyle interventions for cognition and the risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022;130:104236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aravena JM. Healthy lifestyle and cognitive aging: what is the gap behind prescribing healthier lifestyle? Alzheimers Dement. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Bradshaw C, Atkinson S, Doody O. Employing a qualitative description approach in health care research. Global Qualitative Nurs Res. 2017;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Census, OotLGotSCftSNP. Major figures on 2020 population census of China. 2021 http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/rkpc/d7c/202111/P020211126523667366751.pdf

- 30.Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res. 1999;34(5):1189–208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker, SEaE. Rosalind. How many qualitative interviews is enough? National Center for Research Methods 2012 [ https://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/id/eprint/2273/

- 32.Kallio H, Pietila AM, Johnson M, Kangasniemi M. Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(12):2954–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Res Psychol. 2021;18(3):328–52. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ltd QIP. NVivo (Version 12) 2018 https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo/

- 35.Chen HY, Boore JRP. Translation and back-translation in qualitative nursing research: methodological review. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(1–2):234–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sener M, Küçükgüçlü Ö, Akyol MA. Does having a family member with dementia affect health beliefs about changing lifestyle and health behaviour for dementia risk reduction? Psychogeriatrics. 2024;24(4):868–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J, Corazzini KN, McConnell ES, Ding D, Xu HZ, Wei SJ, et al. Living with cognitive impairment in China: exploring Dyadic experiences through a person-centered care lens. Res Aging. 2021;43(3–4):177–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Esandi N, Nolan M, Canga-Armayor N, Pardavila-Belio MI, Canga-Armayor A. Family dynamics and the Alzheimer’s disease experience. J Fam Nurs. 2021;27(2):124–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teahan A, Lafferty A, McAuliffe E, Phelan A, O’Sullivan L, O’Shea D, et al. Resilience in family caregiving for people with dementia: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(12):1582–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoel V, Wolf-Ostermann K, Ambugo EA. Social isolation and the use of technology in caregiving Dyads living with dementia during COVID-19 restrictions. Front Public Health. 2022;10:697496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheung DSK, Ho GWK, Chan ACY, Ho KHM, Kwok RKH, Law YPY, et al. A ‘good dyadic relationship’ between older couples with one having mild cognitive impairment: a Q-methodology. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eskola P, Jolanki O, Aaltonen M. Through thick and thin: the meaning of dementia for the intimacy of ageing couples. Healthc (Basel). 2022;10(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Yuan Q, Zhang Y, Samari E, Jeyagurunathan A, Goveas R, Ng LL, et al. Positive aspects of caregiving among informal caregivers of persons with dementia in the Asian context: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23(1):51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shim B, Barroso J, Gilliss CL, Davis LL. Finding meaning in caring for a spouse with dementia. Appl Nurs Res. 2013;26(3):121–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Losada-Baltar A, Falzarano FB, Hancock DW, Márquez-González M, Pillemer K, Huertas-Domingo C, et al. Cross-national analysis of the associations between familism and self-efficacy in family caregivers of people with dementia: effects on burden and depression. J Aging Health. 2024;36(7–8):403–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu X, Chen S, He M, Dong Y, Fang S, Atigu Y, et al. Life experience and identity of spousal caregivers of people with dementia: a qualitative systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2024;154:104757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duangjina T, Hershberger PE, Gruss V, Fritschi C. Resilience in family caregivers of Asian older people with dementia: an integrative review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. n/a(n/a). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Miller M, Neiterman E, Keller H, McAiney C. Being a husband and caregiver: the adjustment of roles when caring for a wife who has dementia. Can J Aging / La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement. 2024:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Zhao W, Wu M-L, Petsky H, Moyle W. Family carers’ expectations regarding dementia care services and support in China: a qualitative study. Dementia-International J Social Res Pract. 2022;21(6):2004–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nordtug B, Malmedal WK, Alnes RE, Blindheim K, Steinsheim G, Moe A. Informal caregivers and persons with dementia’s everyday life coping. Health Psychol Open. 2021;8(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Bruinsma J, Peetoom K, Boots L, Daemen M, Verhey F, Bakker C, et al. Tailoring the web-based ‘partner in balance’ intervention to support spouses of persons with frontotemporal dementia. Internet Interv. 2021;26:100442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bruinsma J, Peetoom K, Bakker C, Boots L, Millenaar J, Verhey F, et al. Tailoring and evaluating the web-based ‘partner in balance’ intervention for family caregivers of persons with young-onset dementia. Internet Interv. 2021;25:100390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shi Y, Dong S, Liang Z, Xie M, Zhang H, Li S, et al. Affiliate stigma among family caregivers of individuals with dementia in China: a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1366143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Organization WH. Optimizing brain health across the life course: WHO position paper 2022 https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240054561

- 55.Robinson L, Dickinson C, Magklara E, Newton L, Prato L, Bamford C. Proactive approaches to identifying dementia and dementia risk; a qualitative study of public attitudes and preferences. Bmj Open. 2018;8(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Cheng Ka M, Zhao Ivy Y, Maneze D, Holroyd E, Leung Angela Yee M. Family caregivers’ perceptions and experiences of supporting older people to cope with loneliness: a qualitative interview study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. n/a(n/a). [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.