Abstract

Background

Patients with regional lymph node involvement from squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the vulva have a 48% 5-year relative survival. Recently, sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy has become a viable alternative to inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy. We sought to identify risk factors for predicting a positive SLN in patients with vulvar SCC.

Methods

A retrospective review of 29 patients with vulvar SCC was performed from 2016 to 2021 at a tertiary care center. Clinicopathologic data were collected in addition to SLN status, including number of lymph nodes removed.

Results

The average depth of invasion was 7.9 mm, average tumor size was 1.8 cm, 3 of 23 patients had perineural invasion, and 4 of 23 patients had lymphovascular invasion. One patient who did not map on lymphoscintigraphy and five patients with recurrent vulvar SCC were excluded from final analysis. The average number of SLNs removed was two. One patient had a positive SLN: the depth of invasion was 17 mm, tumor size was 5.1 cm, and lymphovascular invasion was present.

Conclusions

Most patients with early stage vulvar SCC had a negative SLN biopsy. Further study is needed to determine the patient subset that could avoid SLN biopsy altogether.

Keywords: Lymphoscintigraphy, regional lymph nodes

Vulvar cancer is an increasingly common malignancy in the developing world, now accounting for approximately 6% of female reproductive cancers and 0.7% of female cancers overall.1 As many as 90% of vulvar cancers are squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), whereas melanoma and adenocarcinomas comprise the remaining cases.2 At diagnosis, approximately 60% of patients with SCC of the vulva have disease localized to the vulva, 27% have lymph node metastasis, and 6% have distant metastasis (7% unknown stage). Patients with regional lymph node involvement from SCC of the vulva have a 48.4% 5-year relative survival compared to 86.8% for localized disease.1

The presence of lymph node metastasis is a significant prognostic factor for patients with vulvar SCC.3 In the past, all patients with vulvar SCC underwent vulvectomy and inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy regardless of the size of the primary tumor. Due to the increased risk of lymphedema, more recent studies have introduced sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) as a viable alternative. Per the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, patients are eligible for SLNB if they have unifocal disease measuring <4 cm, no evidence of clinical or radiologic nodal disease, and no prior history of vulvar surgical intervention.4 Patients with T1b (tumor >2 cm or stromal invasion >1 mm) or T2 (any size with invasion into adjacent perineal structures) pathology have an 8% chance of lymphatic metastasis and are therefore recommended for lymph node evaluation in their staging and workup.5 Because patients with T1a pathology (size <2 cm, confined to vulva/perineum, stromal depth of invasion <1 mm) have a 1% incidence of a positive sentinel lymph node (SLN), SLNB is not recommended in this group.4

We sought to identify risk factors and characteristics predicting a positive SLN in patients with early stage vulvar SCC with the goal of potentially identifying low-risk patients that may be precluded from a SLNB.

METHODS

A retrospective review of 29 patients with vulvar SCC was performed from 2016 to 2021 at a tertiary care center. The research protocol was approved by the institutional review board prior to data gathering. All patients who underwent SLNB for vulvar SCC by a single surgeon were included in the study.

The patient cohort was treated by a total of three gynecologic oncologists and one surgical oncologist. In all cases, partial radical vulvectomy was performed by the gynecologic oncologist, and SLNB was performed by the surgical oncologist. Partial radical vulvectomy involved wide excision of the primary lesion with at least 1 cm margins as well as the associated perineal deep soft tissues down to the level of the fascia. In some instances, SLNB was performed after primary resection since the initial biopsy did not necessitate SLNB. All patients underwent preoperative lymphoscintigraphy and had methylene blue injected at the primary tumor site.

Clinicopathologic data were collected including age, race, depth of invasion, tumor size, grade, recurrence, history of lichen sclerosis, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, and SLN status including number of lymph nodes removed. In addition, patients were followed during the immediate postoperative period (30 days) to identify complications related to the SLNB such as infection, seroma, and lymphedema. Bivariate statistical analysis was performed by a biostatistician utilizing Student’s t test, Fisher’s exact test for count data, and Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test.

RESULTS

Twenty-three patients were included in final analysis after excluding five patients with recurrent disease (and/or second primaries) and one patient who did not map on lymphoscintigraphy (excluded patient details in Table 1). The median age at diagnosis was 66 years, and 19 of 23 patients (82.6%) were Caucasian. The average body mass index was 28.5 kg/m2. Six of 23 (26.1%) patients had bilateral SLN, all of whom had primary lesions in the clitoris or central vulva.

Table 1.

Overall descriptive summary statistics and by recurrence status

| Variable | Study cohort (N = 23) |

Recurrent disease (N = 5) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years): mean (range) | 63.0 (23–84) | 77.4 (63–95) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Black | 1 (4.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 3 (13.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| White/Caucasian | 19 (82.6%) | 5 (100.0%) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2): mean (range) | 28.5 (14.1–38.2) | 33.2 (22.9–43.6) |

| Smoker | ||

| Current | 4 (17.4%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Former | 7 (30.4%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Never | 11 (47.8%) | 3 (60.0%) |

| Unknown | 1 (4.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Lichen sclerosus | 3 (13.0%) | 4 (80.0%) |

| History of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (100.0%) |

| Tumor location | ||

| Central vulva | 2 (8.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Clitoris | 9 (39.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Labia majora | 10 (43.5%) | 4 (80.0%) |

| Labia majora and minora | 1 (4.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Labia minora | 1 (4.3%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Midline | 11 (47.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Laterality | ||

| Bilateral | 6 (26.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Left | 3 (13.0%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Right | 14 (60.9%) | 3 (60.0%) |

| Biopsy depth of invasion (mm) | ||

| <1 | 2 (8.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| >1 | 9 (39.1%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Not reported | 12 (52.2%) | 3 (60.0%) |

| Number of nodes: median | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Lymph node location | ||

| Deep | 3 (13.0%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Superficial | 20 (87.0%) | 4 (80.0%) |

| Lymph node positive | 1 (4.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| T stage | ||

| pT1b | 22 (95.7%) | 5 (100.0%) |

| pT2 | 1 (4.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Perineural invasion | 3 (13.0%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 4 (17.4%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Depth of invasion (mm): mean (range) | 7.9 (1.5–30) | 6.5 (1.3–16) |

| Size (cm): mean (range) | 1.8 (0.2–5.3) | 2.0 (0.2–3.2) |

| Grade | ||

| 0 | 1 (4.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 1 | 7 (30.4%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| 2 | 14 (60.9%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| 3 | 1 (4.3%) | 1 (20.0%) |

The average depth of invasion was 7.9 mm (range 1.5–30 mm), average tumor size was 1.8 cm, 3 of 23 (13.0%) had perineural invasion, 4 of 23 (17.4%) had lymphovascular invasion, 3 (13.0%) had a history of lichen sclerosus, and the average number of SLN removed was 2. Only 1 patient (4.2%) had T2 pathology; the rest had T1b pathology (95.7%). One patient (4.3%) had a positive SLN: the depth of invasion was 17 mm, tumor size was 5.1 cm, lymphovascular invasion was present, and the patient did not have a history of lichen sclerosus (Table 1). Tumor size was the only variable found to be statistically significant in bivariate analysis (Table 2). There were no recurrences in this patient cohort, with a mean follow-up interval of 50.6 months (range 4.9–160.0 months).

Table 2.

Bivariate association between patient characteristics and positive lymph node

| Variable | Negative (N = 22) |

Positive (N = 1) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years): mean (range) | 62.0 (23–84) | 84.0 | 0.151 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2): mean (range) | 28.1 (14.1–38.2) | 37.4 | 0.201 |

| Smoker | 1.002 | ||

| Current | 4 (18.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Former | 7 (31.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Never | 10 (45.5%) | 1 (100.0%) | |

| Unknown | 1 (4.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Lichen sclerosus | 3 (13.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1.002 |

| History of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma | 22 (100.0%) | 1 (100.0%) | |

| Tumor location | 0.572 | ||

| Central vulva | 2 (9.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Clitoris | 8 (36.4%) | 1 (100.0%) | |

| Labia majora | 10 (45.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Labia majora and minora | 1 (4.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Labia minora | 1 (4.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Midline | 10 (45.5%) | 1 (100.0%) | 0.482 |

| Number of nodes: median | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.813 |

| Lymph node location | 0.132 | ||

| Deep | 2 (9.1%) | 1 (100.0%) | |

| Superficial | 20 (90.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| T stage | 1.002 | ||

| pT1b | 21 (95.5%) | 1 (100.0%) | |

| pT2 | 1 (4.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Perineural invasion | 3 (13.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1.002 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 3 (13.6%) | 1 (100.0%) | 0.172 |

| Margins | 1.002 | ||

| Negative | 21 (95.5%) | 1 (100.0%) | |

| Positive | 1 (4.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Depth of invasion (mm): mean (range) | 7.5 (1.5–30) | 17.0 | 0.201 |

| Size (cm): mean (range) | 1.7 (0–5.3) | 5.1 | 0.021 |

| Grade | 1.002 | ||

| 0 | 1 (4.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| 1 | 7 (31.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| 2 | 13 (59.1%) | 1 (100.0%) | |

| 3 | 1 (4.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

P value based on 1Student’s t test; 2Fisher’s exact test for count data; 3Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test.

In the recurrent cohort of five patients, the average depth of invasion was 6.5 mm (range 1.3–16 mm), average tumor size was 2.0 cm, 2 (40%) had perineural invasion, 2 (40%) had lymphovascular invasion, 4 (80%) had a history of lichen sclerosus, and the average number of SLN removed was 2. There were no positive SLNs in this cohort (Table 1).

Nearly half (14/29, 48.3%) of patients did not have stromal depth of invasion reported on their original vulvar biopsies. Thirteen patients (44.8%) had biopsy stromal depths of invasion that met criteria for T1b staging (at least 1 mm) and therefore met criteria for nodal evaluation. One patient had a depth of invasion of 0.5 mm on initial biopsy. The vulvectomy specimen revealed a depth of invasion of 2 mm, meeting criteria for T1b disease. This patient underwent SLNB shortly thereafter. There were no postoperative complications related to SLNB in this patient cohort during the 30 days following surgery.

DISCUSSION

Currently SLNB is the standard of care for early stage vulvar cancer.4 As well documented in the melanoma and breast literature, the main advantage of SLNB over complete lymphadenectomy (CLND) is the reduced morbidity associated with SLNB. Patients with vulvar cancer who underwent a CLND were found to have a 43% rate of lymphedema (as defined by leg volume change >10%) and a 26% rate of postoperative infection.6 In comparison, patients who underwent SLNB alone were found to have a 4.5% rate of infection and a 1.9% rate of lymphedema. Subsequent CLND due to a positive SLN led to significantly increased morbidity. Thirty-four percent of patients experienced groin wound breakdown, 21.3% developed infection, and 25.2% were diagnosed with lymphedema.7 Avoidance of CLND is ideal in terms of morbidity.

In 2008, the results of the GROINSS-V-I trial reported that patients who had a negative SLNB could safely forgo CLND since only 2.3% of patients developed a local recurrence at a median follow-up of 35 months.7 Longer-term follow-up of this patient cohort demonstrated that 10-year disease-specific survival was 91% for patients with a negative SLN compared to 65% for patients with a positive SLN. Unfortunately, 36% of patients with a negative SLN developed a local recurrence compared to 46% of patients with a positive SLN. This study also showed that when patients develop a local recurrence, disease-specific survival significantly decreased.8

Recently, the results of the GROINSS-VII trial, a trial evaluating inguinofemoral radiotherapy as an alternative for CLND, were reported. This multicenter prospective trial randomized patients with a positive SLN to CLND followed by radiation versus radiation alone. After a 2-year follow-up, <2% of patients with SLN micrometastasis (≤2 mm) developed a local recurrence regardless of whether CLND was performed. Patients with SLN macrometastasis (>2 mm) who underwent radiation alone had a 22% recurrence rate versus a 6.9% recurrence rate for patients who underwent CLND followed by radiation. This study showed that adjuvant radiation is an acceptable alternative compared to CLND with less morbidity in the presence of micrometastasis. However, patients with macrometastasis in the SLN should undergo CLND followed by radiation.9

SNLB is not a perfect operation for the detection of lymph node metastasis. In fact, the overwhelming majority of patients who develop a groin recurrence will die.8 GOG-173 is a study that examined concordance of SLN status with lymph node positivity by performing inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy after an initial SLN biopsy. The authors concluded that 11/132 (8.3%) had false-negative SLN.10 As a result, patients who have negative SLNB must be followed closely with frequent physical exam and imaging studies.

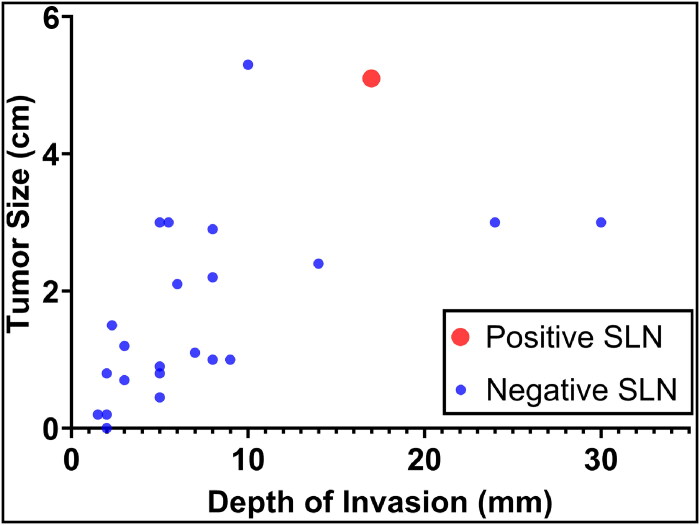

These large, multicenter clinical trials have clearly shifted the paradigm in the treatment of primary vulvar SCC, replacing the morbidity of inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy with SLNB. In light of these advances, the investigators of this study sought to further refine criteria for SLNB in patients with early stage vulvar SCC. Given that only one patient in our cohort had a positive SLN, perhaps a subset of patients could avoid SLNB altogether. One Danish analysis demonstrated that patients who had grade 1 tumors that were <2 cm outside the clitoral area had no lymph node metastasis. Moreover, they found that patients with higher-grade tumors (grade 2–3), larger tumor size (>2 cm), and tumors in the clitoris had a significantly higher rate of inguinal lymph node metastasis.11 The higher rate of nodal metastasis related to clitoral involvement is thought to be due to its rich blood and lymphatic supply when compared to other parts of the vulva. This study did not evaluate depth of invasion. Our study was similar to the Danish study in that among the five patients who had grade 1 tumors <2 cm outside the clitoris, the SLN was negative (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scatterplot of patients with vulvar squamous cell carcinoma after sentinel lymph node biopsy.

As many as 20% to 23% of patients with vulvar cancer will develop recurrent disease.12 Few studies have been published regarding the accuracy and reliability of SLNB for patients with recurrent disease, and per NCCN guidelines, these patients are not candidates for surgical groin evaluation via SLNB.13,14 One retrospective review of 27 patients with recurrent disease found that while there might be higher difficulty with localizing the SLN, 77% of patients successfully underwent repeat SLNB. Importantly, no further recurrences were observed after a median follow-up of 27 months (range 2–96 months).15 The patients with recurrence in our study also successfully underwent SLNB, but none of these patients had a history of prior SLNB. Further analysis is required to determine whether repeat SLNB is a reasonable option for patients with recurrent disease.

There were many limitations to our analysis. Our study was retrospective and included a small sample size. Likewise, only one patient had a positive SLN. The patient with a positive SLN was found to have a tumor size >4 cm after vulvectomy, which technically made them ineligible for SLNB per NCCN guidelines. In addition, longer follow-up is needed to determine the true risk of recurrence and morbidity associated with SLNB. A larger cohort of patients is needed to identify a specific patient population that may omit SLNB altogether.

In conclusion, SLNB for early stage vulvar carcinoma is currently the standard of care. Although the morbidity of SLNB is significantly less than that of CLND, many patients may still undergo SLNB with minimal added benefit. The lowest-risk group appears to be patients with grade 1 tumors <2 cm in size outside of the clitoris. Vulvar carcinomas are rare, and additional data and follow-up are imperative to determine whether this subset would not benefit from SLNB.

Disclosure statement/Funding

The authors report no funding or conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.SEER cancer statistics factsheets: vulvar cancer. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/vulva.html. Accessed January 21, 2023.

- 2.Cancer.net . ASCO: vulvar cancer. https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/vulvar-cancer/introduction. Accessed January 23, 2023.

- 3.Burger MP, Hollema H, Emanuels AG, et al. The importance of the groin node status for the survival of T1 and T2 vulval carcinoma patients. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;57(3):327–334. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1995.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Vulvar cancer (squamous cell carcinoma, version 1.2023). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/vulvar.pdf. Accessed August 26, 2023.

- 5.Stehman FB, Look KY.. Carcinoma of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(3):719–733. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000202404.55215.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlson JW, Kauderer J, Hutson A, et al. GOG 244—the Lymphedema and Gynecologic Cancer (LEG) Study: incidence and risk factors in newly diagnosed patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;156(2):467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van der Zee AG, Oonk MH, De Hullu JA, et al. Sentinel node dissection is safe in the treatment of early-stage vulvar cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(6):884–889. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grootenhuis NC, Van der Zee AG, van Doorn HC, et al. Sentinel nodes in vulvar cancer: long-term follow-up of the GROningen International Study on Sentinel nodes in Vulvar cancer (GROINSS-V) I. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;140(1):8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oonk MH, Slomovitz B, Baldwin PJ, et al. Radiotherapy versus inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy as treatment for vulvar cancer patients with micrometastases in the sentinel node: results of GROINSS-V II. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(32):3623–3632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levenback CF, Ali S, Coleman RL, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy in women with squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(31):3786–3791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schnack TH, Froeding LP, Kristensen E, et al. Preoperative predictors of inguinal lymph node metastases in vulvar cancer – a nationwide study. Gynecol Oncol. 2022;165(3):420–427. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2022.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zach D, Åvall-Lundqvist E, Falconer H, et al.. Patterns of recurrence and survival in vulvar cancer: a nationwide population-based study. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;161(3):748–754. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2021.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Hullu JA, Piers DA, Hollema H, et al.. Sentinel lymph node detection in locally recurrent carcinoma of the vulva. BJOG. 2001;108(7):766–768. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landkroon AP, de Hullu JA, Ansink AC.. Repeat sentinel lymph node procedure in vulval carcinoma. BJOG. 2006;113(11):1333–1336. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Doorn HC, van Beekhuizen HJ, Gaarenstroom KN, et al. Repeat sentinel lymph node procedure in patients with recurrent vulvar squamous cell carcinoma is feasible. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;140(3):415–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]