Abstract

Background

Up to 65% of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) who are treated with imatinib do not achieve sustained deep molecular response, which is required to attempt treatment-free remission. Asciminib is the only approved BCR::ABL1 inhibitor that Specifically Targets the ABL Myristoyl Pocket. This unique mechanism of action allows asciminib to be combined with adenosine triphosphate–competitive tyrosine kinase inhibitors to prevent resistance and enhance efficacy. The phase II ASC4MORE trial investigated the strategy of adding asciminib to imatinib in patients who have not achieved deep molecular response with imatinib.

Methods

In ASC4MORE, 84 patients with CML in chronic phase not achieving deep molecular response after ≥ 1 year of imatinib therapy were randomized to asciminib 40 or 60 mg once daily (QD) add-on to imatinib 400 mg QD, continued imatinib 400 mg QD, or switch to nilotinib 300 mg twice daily.

Results

More patients in the asciminib 40- and 60-mg QD add-on arms (19.0% and 28.6%, respectively) achieved MR4.5 (BCR::ABL1 ≤ 0.0032% on the International Scale) at week 48 (primary endpoint) than patients in the continued imatinib (0.0%) and switch to nilotinib (4.8%) arms. Fewer patients discontinued asciminib 40- and 60-mg QD add-on treatment (14.3% and 23.8%, respectively) than imatinib (76.2%, including crossover patients) and nilotinib (47.6%). Asciminib add-on was tolerable, with rates of AEs and AEs leading to discontinuation less than those with nilotinib, although higher than those with continued imatinib (as expected in these patients who had already been tolerating imatinib for ≥ 1 year). No new or worsening safety signals were observed with asciminib add-on vs the known asciminib monotherapy safety profile.

Conclusions

Overall, these results support asciminib add-on as a treatment strategy to help patients with CML in chronic phase stay on therapy to safely achieve rapid and deep response, although further investigation is needed before this strategy is incorporated into clinical practice.

Trial registration

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13045-024-01642-6.

Keywords: ASC4MORE, CML, Asciminib, Tyrosine kinase inhibitors, Deep molecular response, Imatinib, Add-on, Combination

Background

Treatment of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase (CML-CP) with adenosine triphosphate (ATP)–competitive tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) has extended the life expectancy of patients to be comparable to that of the general population [1]. As a result, the focus of treatment goals has shifted toward improving quality of life and achieving stable deep molecular response (DMR) and treatment-free remission (TFR). Current guidelines state that to attempt TFR, patients must have achieved sustained DMR defined as MR4.5 (BCR::ABL1 ≤ 0.0032% on the International Scale [IS]) for ≥ 2 years or MR4 (BCR::ABL1IS ≤ 0.01%) for ≥ 3 years, prior to being eligible for discontinuation [2, 3].

To improve outcomes and increase the proportion of patients eligible for TFR, treatments that provide rapid and sustained DMR are needed. Sustained DMR is associated with an extremely low risk of loss of response when a TKI is continued [4, 5], and it is a requirement for attempts at TFR [2, 3]. However, many patients do not currently qualify to attempt TFR [2, 3, 6]. By 5 years, 52% to 67% of newly diagnosed patients treated with imatinib do not achieve DMR (MR4 or MR4.5), and 35% to 58% on second-generation TKIs do not achieve DMR, based on data from the DASISION, ENESTnd, and BFORE trials [7–9]. By 10 years, cumulative TFR eligibility in ENESTnd was 47.3% to 48.6% in the nilotinib arms and 29.7% in the imatinib arm [10].

Asciminib is a BCR::ABL1 inhibitor that is approved for the treatment of adults with Philadelphia chromosome–positive CML-CP previously treated with at least 2 TKIs, and in certain countries, for the treatment of Philadelphia chromosome–positive CML-CP with the T315I mutation [11–13]. In contrast to other TKIs that bind to the ATP-binding site, asciminib is the only approved TKI that inhibits ABL tyrosine kinase activity by Specifically Targeting the ABL Myristoyl Pocket (STAMP) [11, 12, 14]. This specificity is thought to minimize off-target effects [15–17].

The unique mechanism of action of asciminib allows for its combination with ATP-competitive TKIs such as imatinib to overcome and potentially prevent the emergence of resistance, expanding the treatment options available for patients with CML to help more patients achieve their treatment goals, including maintaining or improving quality of life, avoiding having to switch therapy, or achieving TFR eligibility. Preclinical findings show that combining asciminib with ATP-competitive TKIs leads to suppression of resistant outgrowth in BCR::ABL1 mutant cells [15, 16], suggesting that add-on therapy may promote enhanced BCR::ABL1 inhibition. Asciminib has shown statistically superior efficacy across lines of therapy in 2 phase III trials. Findings from the phase III ASCEMBL trial (NCT03106779) showed that asciminib had greater efficacy in patients with CML-CP who were treated with at least 2 prior TKIs when compared with the ATP-competitive TKI bosutinib [16, 18]. At weeks 24 and 96, the major molecular response (MMR; BCR::ABL1IS ≤ 0.1%) rate was superior with asciminib (25.5% and 37.6%, respectively) compared with bosutinib (13.2% and 15.8%, respectively) [16, 18]. Long-term results of the ASCEMBL trial at week 96 showed that overall, more patients, including heavily pretreated patients, were able to achieve DMR (MR4) and MR4.5 with asciminib than bosutinib [18].

Recently, the phase III ASC4FIRST trial (NCT04971226) in newly diagnosed CML-CP showed a statistically significantly higher MMR at week 48 with asciminib compared with standard-of-care TKIs (imatinib, nilotinib, dasatinib, and bosutinib; 67.5% vs 49.0%) and compared with imatinib alone (69.3% vs. 40.2%). Asciminib also had numerically higher MMR at week 48 vs second-generation TKIs (nilotinib, dasatinib, and bosutinib), as well as greater rates of DMR and early molecular response across all comparisons [19].

In the phase I X2101 trial (NCT02081378), asciminib demonstrated long-term efficacy at 4 years and a favorable, consistent tolerability profile in patients with CML with and without the T315I mutation [14, 20]. The X2101 trial also included a cohort evaluating asciminib in combination with imatinib. The recommended asciminib add-on doses for further investigation were 40 and 60 mg once daily (QD) when combined with imatinib 400 mg daily [21].

Here, we report results from the ASC4MORE study (NCT03578367) investigating the effect of asciminib 40 and 60 mg QD add-on to imatinib vs continued imatinib vs switch to nilotinib in patients with CML-CP who received treatment with imatinib for ≥ 1 year without achieving DMR.

Methods

The primary objective of this study was to assess whether asciminib 40 or 60 mg QD added-on to imatinib is more effective in achieving MR4.5 at week 48 (the primary endpoint) than continued imatinib in patients with CML-CP who received imatinib for ≥ 1 year without achieving DMR. One secondary objective was to compare the efficacy (MR4.5 at week 48) of asciminib 40 and 60 mg QD add-on with switch to nilotinib; additional objectives for these four treatment arms included further efficacy endpoints (MR4.5 at and by week 96, time to MR4.5, duration of MR4.5), safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics (with asciminib 40 and 60 mg QD add-on to imatinib).

Study oversight

The study was designed collaboratively by the sponsor (Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation) and study investigators. The protocol was approved by the sites' institutional review boards and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent. The sponsor collected and analyzed the data in conjunction with the authors. All authors contributed to the development and writing of the manuscript. All authors and representatives of the sponsor reviewed and amended the manuscript and vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and fidelity of the study to the protocol.

Study design

This is a phase II, multicenter, open-label, randomized study of asciminib add-on to imatinib vs continued imatinib vs switch to nilotinib in patients with CML-CP who have previously received imatinib 400 mg QD as first TKI therapy for ≥ 1 year and have not achieved DMR. A protocol amendment on August 24, 2023, allowed patients who had dose reduction of imatinib to ≥ 300 mg QD while receiving imatinib as first TKI therapy for ≥ 1 year without achieving DMR. However, all patients in this report were enrolled prior to the amendment.

A total of 84 patients who met the eligibility criteria (Additional file 1, Supplementary methods) were randomized 1:1:1:1 to asciminib 40 mg QD add-on to imatinib 400 mg QD, asciminib 60 mg QD add-on to imatinib 400 mg QD, continued imatinib 400 mg QD, and switch to nilotinib 300 mg twice daily (BID) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The ASC4MORE study design. 1L, first line; ABL1, ABL proto-oncogene 1; BCR, breakpoint cluster region; BID, twice daily; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; CP, chronic phase; DMR, deep molecular response; IS, International Scale; MR4.5, BCR::ABL1IS ≤ 0.0032%; QD, once daily. a Based on investigators’ feedback, the inclusion criteria have been updated in a protocol amendment on August 24, 2023, to allow enrollment of patients who were treated with imatinib at a dose of ≥ 300 mg QD for ≥ 1 year and have not achieved DMR. b The monotherapy arm was added in a protocol amendment on July 12, 2022, to estimate the safety and efficacy of single-agent asciminib and is now enrolling. c Patients in the imatinib arm were allowed to switch to the asciminib 60 mg + imatinib arm if they had not achieved MR4.5 at week 48

Patients received treatment until treatment failure, intolerability, or 96 weeks after the last patient received their first dose. After the last patient received their final dose, ongoing patients in all arms were followed up for 30 days. Patients randomized to continue receiving imatinib monotherapy but who had not achieved MR4.5 at their week 48 visit were allowed to cross over to receive asciminib 60 mg QD add-on within 4 weeks of the visit. These patients were analyzed separately from those who received asciminib 60 mg QD add-on at the start of the study.

An amendment in 2022 created an open-label asciminib 80-mg QD monotherapy arm of 20 patients. These patients will receive asciminib until treatment failure, intolerability, or 48 weeks after the last patient has received their first dose. After the last dose is administered, all ongoing patients will be followed up for 30 days. These patients are currently being enrolled, and results from this arm are not yet available.

An interim analysis was planned for when ≥ 40 patients (50%) had been randomized and followed-up for their week 24 assessment or had discontinued treatment.

Patients

Eligible patients were aged ≥ 18 years, with a confirmed diagnosis of CML-CP (Additional file 1, Supplementary methods and Table S1). Patients had BCR::ABL1IS > 0.01% and ≤ 1% at the time of randomization (confirmed with a central assessment at screening); they had received ≥ 1 year of treatment with first-line imatinib 400 mg QD without achieving a DMR (confirmed by 2 consecutive tests at any point while receiving imatinib) and had no dose change in the last 3 months. Patients who had treatment failure with imatinib according to the European LeukemiaNet criteria [2], had a known second CP after progression to accelerated/blast crisis, or had previously received treatment with any TKI other than imatinib were not eligible for inclusion in this study.

Study assessments

Molecular response was assessed using real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction testing of peripheral blood and analyzed at a central testing laboratory. Unconfirmed loss of MMR was defined as an increase in BCR::ABL1IS to > 0.1% in association with a 5-fold increase in BCR::ABL1IS from the lowest value observed during study treatment. Loss of MMR was confirmed by a subsequent analysis of at least 1 sample collected within 4 to 6 weeks reflecting an increase to BCR::ABL1IS > 0.1%, unless the loss of MMR was associated with confirmed loss of complete hematologic response, loss of complete cytogenetic response, progression to accelerated phase/blast crisis, or CML-related death. Additional details regarding study assessments are in Additional file 1, Supplementary methods.

Statistical analysis

The primary analysis was conducted when all randomized patients reached at least week 48 of study treatment or discontinued earlier. The week 96 analysis was performed when all randomized patients had completed their week 96 visit or discontinued earlier. Details of analysis sets are summarized in Additional file 1, Supplementary methods.

Rate of MR4.5 at weeks 48 and 96 was calculated based on the full analysis set (all randomized patients). The rate of MR4.5 at week 48 and its two-sided 90% CI based on the Clopper-Pearson method were presented by treatment arm. The difference in rate of MR4.5 with its two-sided 90% CI between different treatment arms was calculated using the Wald method. Time to MR4.5 in patients who achieved MR4.5 was analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results

Patients

The baseline characteristics and demographics were well-balanced between arms, although more patients in the continued imatinib and switch to nilotinib arms were in MMR at baseline compared with patients in the asciminib add-on arms, in which more patients were in MR2 (BCR::ABL1IS ≤ 1%) (Table 1). Overall, patients had received imatinib for a median of 2.4 (range, 1.1–18.2) years and had not achieved DMR prior to starting the study.

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics

| Asciminib 40 mg QD + imatinib n = 21 | Asciminib 60 mg QD + imatinib n = 21 | Imatinib n = 21 | Nilotinib n = 21 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range), years | 48 (20–72) | 37 (19–72) | 51 (28–76) | 40 (20–68) |

| Age category, n (%) | ||||

| 18 to < 65 years | 18 (85.7) | 19 (90.5) | 16 (76.2) | 19 (90.5) |

| 65 to < 85 years | 3 (14.3) | 2 (9.5) | 5 (23.8) | 2 (9.5) |

| Male, n (%) | 13 (61.9) | 16 (76.2) | 16 (76.2) | 15 (71.4) |

| Prior duration of imatinib, median (range), years | 2.4 (1.1–12.1) | 2.3 (1.1–14.4) | 2.8 (1.1–15.6) | 2.2 (1.2–18.2) |

| BCR::ABL1IS levels at baseline, n (%) | ||||

| > 0.1% to ≤ 1% (MR2) | 11 (52.4) | 13 (61.9) | 6 (28.6) | 7 (33.3) |

| > 0.01% to ≤ 0.1% (MMR) | 10 (47.6) | 8 (38.1) | 15 (71.4) | 14 (66.7) |

ABL1, ABL proto-oncogene 1; BCR, breakpoint cluster region; IS, International Scale; MMR, major molecular response (BCR::ABL1IS ≤ 0.1%); MR2, BCR::ABL1IS ≤ 1%; QD, once daily

Data cutoff was March 6, 2023, when all randomized patients had completed their week 96 visit or discontinued earlier. The median duration of follow-up was 32 months. The median duration of exposure (range) in the asciminib 40-mg QD add-on, asciminib 60-mg QD add-on, continued imatinib, and switch to nilotinib arms was 141.7 weeks (27–203), 124.3 weeks (1–192), 53.4 weeks (50–186), and 110.1 weeks (1–189), respectively.

At data cutoff, 85.7%, 76.2%, 19.0%, and 52.4% of patients in the asciminib 40 mg QD add-on, asciminib 60 mg QD add-on, continued imatinib, and switch to nilotinib arms, respectively, completed the randomized treatment per protocol (Table 2). The most frequent reason for discontinuation in each arm was as follows: asciminib 40 mg QD add-on, patient decision (9.5%); asciminib 60 mg QD add-on, adverse event (AE; 14.3%); continued imatinib, physician decision (66.7%); and switch to nilotinib, AE (33.3%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient disposition

| Variable | Asciminib 40 mg QD + imatinib n = 21 | Asciminib 60 mg QD + imatinib n = 21 | Imatinib n = 21 | Nilotinib n = 21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients randomized, n (%) | ||||

| Treated | 21 (100) | 21 (100) | 20 (95.2)a | 21 (100) |

| Completed randomized treatment | 18 (85.7) | 16 (76.2) | 4 (19.0) | 11 (52.4) |

| Discontinued from randomized treatment, n (%) | 3 (14.3) | 5 (23.8) | 16 (76.2) | 10 (47.6) |

| Reason for discontinuation | ||||

| Adverse event | 0 | 3 (14.3) | 0 | 7 (33.3) |

| Patient decision | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | 1 (4.8) | 3 (14.3) |

| Physician decision | 0 | 0 | 14 (66.7)b | 0 |

| Progressive disease | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.8) | 0 |

| Death | 1 (4.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Duration of exposure, median (range), weeks | 141.7 (27–203) | 124.3 (1–192) | 53.4 (50–186)a | 110.1 (1–189) |

| Crossed over from continued imatinib to asciminib 60-mg QD add-on arm, n (%)b | 14 (66.7) | |||

| Completed crossover phase | 13 (61.9) | |||

| Discontinued crossover phase | 1 (4.8)c |

ABL1, ABL proto-oncogene 1; BCR, breakpoint cluster region; IS, International Scale; MR4.5, BCR::ABL1IS ≤ 0.0032%; QD, once daily

aOne patient was not treated due to patient decision. b Patients in the imatinib arm were allowed to switch to the asciminib 60 mg + imatinib arm if they had not achieved MR4.5 at week 48. c One patient discontinued crossover due to patient decision

Patients discontinuing due to physician decision in the continued imatinib arm did not achieve MR4.5 at week 48 and were thus eligible to cross over to receive asciminib 60 mg QD add-on (Table 2). Patients who crossed over were analyzed separately from patients allocated to the asciminib 60-mg QD add-on arm at the start of the study. At the time of crossover, 12 patients (85.7%) were in MMR, and 2 (14.3%) were in MR2. Thirteen patients (61.9%) completed the crossover treatment per protocol; 1 patient (4.8%) discontinued prematurely.

Efficacy

Overall, more patients achieved the primary endpoint of MR4.5 at week 48 with asciminib add-on than continued imatinib and switch to nilotinib (Fig. 2). At week 48, 19.0% (90% CI, 6.8–38.4) and 28.6% (90% CI, 13.2–48.7) of patients in the asciminib 40- and 60-mg QD add-on arms, respectively, were in MR4.5, compared with 0.0% (90% CI, 0–13.3%) in the continued imatinib arm and 4.8% (90% CI, 0.2–20.7) in the switch to nilotinib arm (Fig. 2, Additional file 1, Table S2).

Fig. 2.

MR4.5 at weeks 24, 48, and 96. ABL1, ABL proto-oncogene 1; ASC, asciminib; BCR, breakpoint cluster region; IMA, imatinib; IS, International Scale; MR4.5, BCR::ABL1IS ≤ 0.0032%; NIL, nilotinib; QD, once daily

At week 96, 19.0% (90% CI, 6.8–38.4) of patients in both asciminib add-on arms were in MR4.5, compared with 4.8% (90% CI, 0.2–20.7) in the continued imatinib arm and 9.5% (90% CI, 1.7–27.1) in the switch to nilotinib arm (Fig. 2). A total of 42.9% (90% CI, 24.5–62.8) and 28.6% (90% CI, 13.2–48.7) of patients in the asciminib 40- and 60-mg QD add-on arms, respectively, were in MR4 at week 48, compared with 0.0% (90% CI, 0.0–13.3) and 23.8% (90% CI, 9.9–43.7) in the continued imatinib and switch to nilotinib arms, respectively.

DMR was achieved more rapidly in patients receiving asciminib add-on compared with continued imatinib and switch to nilotinib (Additional file 1, Figure S1a-S1d). Patients achieved DMR as early as weeks 4 and 8 in the 40- and 60-mg QD add-on arms, respectively (Additional file 1, Figure S1a-S1d). At week 24, 14.3% (90% CI, 4.0–32.9) and 19.0% (90% CI, 6.8–38.4) of patients in the asciminib 40- and 60-mg QD add-on arms were in MR4.5, respectively, compared with 0.0% (90% CI, 0.0–13.3) in the continued imatinib arm and 9.5% (90% CI, 1.7–27.1) in the switch to nilotinib arm. In patients receiving asciminib 40 mg QD add-on, asciminib 60 mg QD add-on, continued imatinib, and switch to nilotinib who achieved MR4.5, median time to MR4.5 was 24.6, 12.4, 66.4, and 36.3 weeks, respectively.

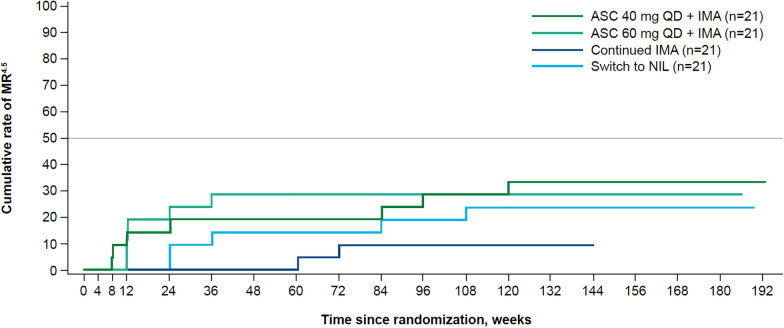

Overall, more patients achieved MR4.5 with asciminib 40 and 60 mg QD add-on than with continued imatinib or switch to nilotinib. Cumulative MR4.5 rates were 28.6% (90% CI, 13.2–48.7) by week 96 in both asciminib add-on arms (n = 6 for both) and 9.5% (n = 2; 90% CI, 1.7–27.1) and 19.0% (n = 4; 90% CI, 6.8–38.4) in the continued imatinib and switch to nilotinib arms, respectively (Fig. 3; Additional file 1, Table S3).

Fig. 3.

Cumulative rate of MR4.5. ABL1, ABL proto-oncogene 1; ASC, asciminib; BCR, breakpoint cluster region; IMA, imatinib; IS, International Scale; MR4.5, BCR::ABL1IS ≤ 0.0032%; NIL, nilotinib; QD, once daily

Of the patients who achieved MR4.5 at any time up to the cutoff, 3 of 7 in the asciminib 40-mg QD add-on arm, 0 of 6 in the asciminib 60-mg QD add-on arm, 0 of 2 in the continued imatinib arm, and 1 of 5 in the nilotinib arm experienced a confirmed loss of MR4.5. At week 96, 38.1% (90% CI, 20.6–58.3) and 23.8% (90% CI, 9.9–43.7) of patients in the 40- and 60-mg QD add-on arms were in MR4, respectively, compared with 9.5% (90% CI, 1.7–27.1) and 28.6% (90% CI, 13.2–48.7) in the continued imatinib and switch to nilotinib arms, respectively (Fig. 4; Additional file 1, Table S4).

Fig. 4.

DMRa (MR4 or deeper response) at week 96. ABL1, ABL proto-oncogene 1; ASC, asciminib; BCR, breakpoint cluster region; DMR, deep molecular response; IMA, imatinib; IS, International Scale; NIL, nilotinib; QD, once daily. a DMR is defined as a response level of at least MR4 (BCR::ABL1IS ≤ 0.01%)

Cumulative MR4 rates were 52.4% (90% CI, 32.8–71.4) and 33.3% (90% CI, 16.8–53.6) by week 96 in the asciminib 40- and 60-mg QD add-on arms, respectively, and 14.3% (90% CI, 4.0–32.9) and 47.6% (90% CI, 28.6–67.2) in the continued imatinib and switch to nilotinib arms, respectively (Additional file 1, Table S5).

Of the 14 patients who crossed over from the continued imatinib arm to the asciminib 60-mg QD add-on arm, 4 achieved MR4.5 as early as 4 weeks and as late as 73 weeks post crossover. Three patients maintained MR4.5 until their last molecular assessment—for at least 12, 52, and 134 weeks, respectively; the fourth patient achieved MR4.5 at week 72 and remained in MR4 until the end of the study (Fig. 5). At week 96, the MR4.5 rate was 14.3% (90% CI, 2.6–38.5) (Additional file 1, Table S6). The cumulative MR4.5 rate by week 96 was 28.6% (90% CI, 10.4–54.0) (Additional file 1, Table S7).

Fig. 5.

BCR:ABL1IS over time post crossover in patients who crossed over to asciminib 60-mg add-on arm.a ABL1, ABL proto-oncogene 1; BCR, breakpoint cluster region; IS, International Scale; MMR, major molecular response; MR4, BCR::ABL1IS ≤ 0.01%; MR4.5, BCR::ABL1IS ≤ 0.0032%; MR5, BCR::ABL1IS ≤ 0.001%. a Patients in the imatinib arm were allowed to switch to the asciminib 60 mg + imatinib arm if they had not achieved MR4.5 at week 48. At crossover, 2 patients had BCR::ABL1IS ≥ 0.1% and 12 were in MMR. Each line on the graph represents BCR::ABL1IS levels over time for an individual patient

Safety

No major changes in safety were observed over time. Asciminib 40 and 60 mg QD add-on led to lower rates of grade ≥ 3 AEs and AEs leading to discontinuation than switch to nilotinib. More patients experienced at least one AE with asciminib 40 and 60 mg QD add-on (100% and 90.5%, respectively) and with switch to nilotinib (100%) vs continued imatinib (75.0%) (Fig. 6). There were no new or worsening safety findings compared with previous studies of asciminib monotherapy (Fig. 6) [14, 18].

Fig. 6.

AEs reported by patients in each treatment arm. AE, adverse event; ASC, asciminib; IMA, imatinib; NIL, nilotinib; QD, once daily. a One patient in the IMA arm was not treated due to patient decision

Eight patients (38.1%) each in the asciminib 40- and 60-mg QD add-on arms experienced an AE of grade ≥ 3, compared with 2 (10.0%) in the continued imatinib arm and 9 (42.9%) in the switch to nilotinib arm (Fig. 6).

AEs reported by patients in the asciminib add-on arms did not occur in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7). The most frequently reported AEs of any grade were nausea (33.3%), diarrhea (23.8%), and myalgia (23.8%) in the asciminib 40-mg QD add-on arm; COVID-19 (42.9%), increased lipase level (19.0%), and alopecia (19.0%) in the asciminib 60-mg add-on arm; diarrhea (15.0%), increased lipase level (15.0%), and hypophosphatemia (15.0%) in the continued imatinib arm; and rash (38.1%), COVID-19 (28.6%), and increased alanine aminotransferase level (23.8%) in the switch to nilotinib arm.

Fig. 7.

Any-grade AEs (≥ 15% of patients in any arm) in each treatment arm. AE, adverse event; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ASC, asciminib; IMA, imatinib; NIL, nilotinib; QD, once daily. a One patient in the IMA arm was not treated due to patient decision

Rates of AEs leading to discontinuation were 4.8% (n = 1), 14.3% (n = 3), 0%, and 33.3% (n = 7) of patients in the asciminib 40-mg QD add-on, asciminib 60-mg add-on, continued imatinib, and switch to nilotinib arms, respectively (Fig. 6, Additional file 1, Table S8). Overall, 7, 8, 2, and 5 patients in the asciminib 40-mg QD add-on, asciminib 60-mg QD add-on, continued imatinib, and switch to nilotinib arms, respectively, reported at least one AE that led to dose adjustment or interruption of treatment. In the asciminib 60-mg QD add-on arm, 3 patients discontinued study treatment due to an AE: grade 3 skin hyperesthesia, grade 3 pancreatitis, and grade 4 elevated lipase level and grade 3 elevated amylase level (reported by the same patient). A total of 7 patients in the switch to nilotinib arm discontinued treatment due to experiencing at least one AE; lipase elevation was the most commonly reported AE and was observed in 2 patients.

The most frequently reported AEs of special interest of any grade included gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity (42.9%), hypersensitivity (23.8%), pancreatic enzyme elevations (19.0%), and hepatotoxicity (19.0%) in the asciminib 40-mg QD add-on arm and GI toxicity (42.9%), pancreatic enzyme elevations (23.8%), and ischemic heart and central nervous system (CNS) conditions (14.3%) in the asciminib 60-mg QD add-on arm (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

AEs of special interest in each treatment arm. AE, adverse event; ASC, asciminib; CNS, central nervous system; GI, gastrointestinal; IMA, imatinib; NIL, nilotinib; QD, once daily. a One patient in the IMA arm was not treated due to patient decision. b In the ASC arms, these events were increased blood creatine phosphokinase level. c In the ASC 40-mg QD add-on, ASC 60-mg QD add-on, continued imatinib, and switch to nilotinib arms, 19.0%, 19.0%, 15.0%, and 9.5% of patients, respectively, had increased lipase level, while 4.8%, 4.8%, 10.0%, and 4.8%, respectively, had increased amylase level. d All events in the reproductive toxicity category were cases of Gilbert syndrome

Three patients (14.3%) each in the asciminib 40- and 60-mg QD add-on arms experienced increased creatine phosphokinase levels, reported here under ischemic heart and CNS conditions; these AEs were grades 1 and 2 in 5 of 6 patients, and grades 3 and 4 in the remaining 1 patient. None of these patients had musculoskeletal symptoms. Patients in the continued imatinib arm most frequently reported GI toxicity (30.0%), pancreatic enzyme elevations (15.0%), and ischemic heart and CNS conditions (10.0%), while hypersensitivity (52.4%), GI toxicity (42.9%), and hepatotoxicity (38.1%) were the most common AEs of special interest reported by patients in the switch to nilotinib arm. No arterial-occlusive events (AOEs) were reported in either asciminib add-on arm, while in the switch to nilotinib arm, 1 patient (4.8%) experienced an AOE of carotid artery stenosis (Additional file 1, Table S9).

One on-treatment death was reported in the asciminib 40-mg QD add-on arm due to cardiac arrest. The patient was a 70-year-old man diagnosed with CML in 2008 and treated with imatinib from 2008 to 2020. His relevant past medical history included hypertension, type II diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, cardiac stent placement, and, in February 2021, surgery for gastric cancer and cholecystolithiasis. Approximately 6 months after the first dose of study medications and 3 months after gastric surgery, the patient was hospitalized due to abdominal pain and shortness of breath and died of cardiac arrest 5 days later.

Discussion

Overall, the findings of this study provide evidence for the use of asciminib add-on as a treatment option to achieve DMR in patients with CML-CP who have received imatinib for ≥ 1 year without achieving DMR. Asciminib add-on may be a promising strategy to help these patients achieve their treatment goals, including becoming eligible for TFR.

Asciminib add-on showed efficacy in the primary endpoint of MR4.5 at week 48; 19.0% and 28.6% of patients in the 40- and 60-mg asciminib QD add-on arms, respectively, achieved MR4.5 at week 48, compared with 0.0% in the continued imatinib arm and 4.8% in the switch to nilotinib arm. Of note, despite more patients in the continued imatinib arm being in MMR at baseline, none achieved MR4.5 at week 48. In comparison, patients in the asciminib add-on arms had higher baseline BCR::ABL1 levels. MR4.5 rates at week 96, a secondary endpoint, continued to provide evidence that both asciminib add-on doses were effective in achieving deep responses, with more patients in MR4.5 at week 96 with asciminib add-on than with continued imatinib or switch to nilotinib. Importantly, 28.6% of patients in the continued imatinib arm who crossed over to receive asciminib 60 mg QD add-on after not achieving MR4.5 at week 48 were still able to achieve MR4.5. No patients in the continued imatinib arm achieved MR4.5. This may be attributed to the prior treatment of randomized patients with imatinib for a median of 2.4 (range, 1.1–18.2) years without achieving DMR, as well as the limited sample size. Within the CML-study IV, 6.0% of patients receiving imatinib with MMR at 18 months achieved MR4.5 by 5 years, indicating that a small proportion of patients may achieve DMRs at later timepoints with continued imatinib.[22] These results suggest that early asciminib add-on therapy may enable patients who do not achieve DMR after ≥ 1 year of imatinib to more rapidly reach key treatment goals of deep remission. Given that a large percentage of patients worldwide are still initially treated with imatinib, and only approximately 30% of patients achieve TFR eligibility with imatinib by 10 years [10], asciminib add-on therapy may be a viable strategy to help patients who do not meet TFR criteria with imatinib to reach these treatment goals. Furthermore, the asciminib add-on strategy may be preferable to a switch to nilotinib, given that no AOEs were observed in the add-on arms.

Responses with asciminib add-on observed in this trial were rapidly achieved, with 14.3% and 19.0% of patients in the 40- and 60-mg asciminib QD add-on arms, respectively, achieving MR4.5 at week 24, compared with 0.0% and 9.5% in the continued imatinib and switch to nilotinib arms, respectively. However, there appears to be other subgroups of patients with different BCR::ABL1IS kinetics (Additional file 1, Figures S1a and S1b). One group appears to have a more gradual decrease in expression over time; these patients have not yet achieved DMR, but may be able to achieve DMR with longer asciminib add-on treatment, although further investigation is needed. The other group appears to have no change in BCR::ABL1IS levels. This nonresponse may be due to the presence of resistance mutations; though, per protocol, analysis to identify the presence of resistance mutations is only planned in patients who lose response.

Asciminib add-on was found to be tolerable, although it was associated with higher rates of any-grade AEs, grade ≥ 3 AEs, and AEs leading to discontinuation than imatinib monotherapy. This was expected, as these patients previously received imatinib 400 mg for ≥ 1 year without discontinuation due to intolerance.

Overall, the safety profile with the asciminib 40- and 60-mg QD add-on arms was favorable compared with nilotinib. Rates of AE of grade ≥ 3 were around 38% with either combination arm, compared with 10.0% in the continued imatinib arm and 42.9% in the switch to nilotinib arm. Rates of any-grade AEs leading to discontinuation were 4.8% and 14.3% with asciminib 40- and 60-mg QD add-on, respectively, 0% with continued imatinib, and 33.3% with switch to nilotinib. Notably, rates of pancreatic enzyme elevations were similar in asciminib add-on arms compared with the switch to nilotinib arm. Overall, these findings are consistent with those from previous studies of asciminib monotherapy and support the favorable safety and tolerability profiles of asciminib add-on therapy [13, 14, 16, 18]. No new safety signals were observed over time with asciminib 40 or 60 mg QD add-on to imatinib, compared with previous studies of asciminib monotherapy [13, 14, 16, 18]. These findings provide further support for the manageable safety profile of asciminib add-on to imatinib in patients with CML-CP.

The approved dose of asciminib as monotherapy for CML-CP without the T315I mutation is 80 mg QD or 40 mg BID [11, 12]. However, prior phase I studies demonstrated an increase in asciminib exposure (area under the curve [AUC] and maximum drug concentration [Cmax]) when administered with imatinib, but no effect of asciminib on imatinib exposure [21]. The asciminib 40-mg QD dose in combination with imatinib provided comparable Cmax but up to 40% decrease in AUC relative to asciminib 40 mg BID. Likewise, the asciminib 60-mg QD dose in combination with imatinib provided comparable AUC, with 1.5- to 1.85-fold increase in Cmax. Despite these differences in pharmacokinetic profiles, this trial was not designed to compare between asciminib add-on arms, and did not elucidate a difference in efficacy and safety between doses.

Another treatment option for patients who are unable to achieve DMR after ≥ 1 year of imatinib therapy might be to switch to asciminib. The addition of the asciminib monotherapy arm to the ASC4MORE study will help to establish whether asciminib alone is sufficient for patients to reach their treatment goals, while further assessing the relative safety and tolerability of asciminib monotherapy in patients who have received a prior TKI.

Although polymerase chain reaction results depicting BCR::ABL1IS kinetics appear to objectively support the clinical benefit observed, this study was not formally designed to compare efficacy results between the arms and was not blinded. The study was not powered for hypothesis testing and the small sample size limits further interpretation of these promising results. These limitations may affect interpretation of efficacy; however, this trial was designed to gain an early understanding of the potential for the asciminib add-on strategy to be a safe and effective alternative to switching to a second-generation TKI. The asciminib monotherapy arm was added after recruitment for the other arms was completed and therefore, there are no direct comparisons for this arm with the asciminib add-on arms, limiting interpretation of the study results. Further validation is required before incorporating the asciminib add-on strategy into clinical practice.

There is a need for shared treatment decision-making between patients and physicians that considers several factors. While second-generation TKIs show an advantage over imatinib in terms of efficacy, it does not translate into significantly improved survival outcomes [23]. An increased rate of AEs and AEs leading to discontinuation were reported in the asciminib add-on arms compared with the continued imatinib arm, although this was expected as these patients had tolerated imatinib for over a year without intolerance leading to discontinuation. Asciminib add-on also had a favorable safety profile compared with nilotinib, with faster and deeper response rates than both imatinib and nilotinib. However, the increased pill burden of asciminib add-on therapy should be considered when selecting a therapeutic strategy. Therefore, patients and physicians should consider the benefit–risk profile of asciminib add-on on an individual basis.

ASC2ESCALATE (NCT05384587) is another phase II trial investigating alternative asciminib dosing strategies in patients with CML-CP who discontinued initial TKI therapy [24]. Moreover, in addition to ASC4FIRST, several other studies are assessing asciminib monotherapy as first TKI, including ASCEND, ASC4START (NCT05456191), and ASC2ESCALATE, which also includes a cohort of newly diagnosed patients [19, 24–26].

Conclusions

Overall, these findings suggest that asciminib add-on may be a promising strategy to help more patients safely achieve rapid and deep responses.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. We thank the patients who participated in the trial and their families/caregivers, and the staff at each site who assisted with the study. Writing support was provided by Michelle Chadwick, PhD, CMPP, and Melanie Vishnu, PhD, of Nucleus Global and was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Abbreviations

- AE

Adverse event

- AOE

Arterial-occlusive event

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- AUC

Area under the curve

- BID

Twice daily

- Cmax

Maximum drug concentration

- CML-CP

Chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase

- CNS

Central nervous system

- DMR

Deep molecular response

- GI

Gastrointestinal

- IS

International Scale

- MMR

Major molecular response

- MR2

BCR::ABL1IS ≤ 1%

- MR4

BCR::ABL1IS ≤ 0.01%

- MR4.5

BCR::ABL1IS ≤ 0.0032%

- QD

Once daily

- STAMP

Specifically Targets the ABL Myristoyl Pocket

- TFR

Treatment-free remission

- TKI

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the interpretation of data and drafting, reviewing, revising and deciding to publish the manuscript.

Funding

This study was sponsored and funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Availability of data and materials

Novartis is committed to sharing access to patient-level data and supporting clinical documents from eligible clinical trials with qualified external researchers upon request. These requests are reviewed and approved by an independent review panel based on scientific merit. All data provided are anonymized to respect the privacy of patients who have participated in the trial consistent with applicable laws and regulations. The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current trial are available according to the criteria and process described on www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol was approved by the sites' institutional review boards and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable; no individual patient data are included.

Competing interests

TPH received research funding from Novartis, and Bristol Myers Squibb, and consultancy fees from Novartis, Takeda, Terns Pharmaceuticals, Enliven Therapeutics, and Ascentage Pharma. JG has received payment for consultancy from Novartis and Incyte. He is a committee member of the European Hematologic Association. He reports grants to his patient advocacy organization from Novartis, Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Incyte, Takeda, and Terns Pharmaceuticals. D-WK received research funding from Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Enliven, Korea Otsuka, Il-Yang, and PharmaEssentia; honoraria from Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Enliven, Krea Otsuka, and Il-Yang; and speaker bureau fees from Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Korea Otsuka, and Il-Yang. EL received personal fees from Novartis, and Pfizer and is a member of speakers bureaus for Novartis, Pfizer, and Fusion Pharma. JM received research funding from BeiGene. AT received personal fees from Novartis, Pfizer, and R-Pharma and is a member of the speakers bureaus for Novartis, Pfizer, and R-Pharma. JEC received research funding from AbbVie, Ascentage Pharma, Novartis, and Sun Pharma and consultancy fees from Lilly, Nerviano, Novartis, Pfizer, Rigel, Sun Pharma, Syndax, and Biopath Holdings. He holds stock options in and is a board member of Biopath Holdings. BN, and SQ are employees of Novartis. APC and SK are employees and shareholders of Novartis stock. GS declares no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sasaki K, Strom SS, O’Brien S, Jabbour E, Ravandi F, Konopleva M, et al. Relative survival in patients with chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukaemia in the tyrosine-kinase inhibitor era: analysis of patient data from six prospective clinical trials. Lancet Haematol. 2015;2(5):e186–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hochhaus A, Baccarani M, Silver RT, Schiffer C, Apperley JF, Cervantes F, et al. European LeukemiaNet 2020 recommendations for treating chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2020;34(4):966–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah NP, Bhatia R, Altman JK, Amaya M, Begna KH, Berman E, et al. Chronic myeloid leukemia, version 2.2024, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2024;22(1):43–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Branford S, Seymour JF, Grigg A, Arthur C, Rudzki Z, Lynch K, Hughes T. BCR-ABL messenger RNA levels continue to decline in patients with chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia treated with imatinib for more than 5 years and approximately half of all first-line treated patients have stable undetectable BCR-ABL using strict sensitivity criteria. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(23):7080–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colombat M, Fort MP, Chollet C, Marit G, Roche C, Preudhomme C, et al. Molecular remission in chronic myeloid leukemia patients with sustained complete cytogenetic remission after imatinib mesylate treatment. Haematologica. 2006;91(2):162–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cortes J, Rea D, Lipton JH. Treatment-free remission with first- and second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Am J Hematol. 2019;94(3):346–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brümmendorf TH, Cortes JE, Milojkovic D, Gambacorti-Passerini C, Clark RE, le Coutre P, et al. Bosutinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia: final results from the BFORE trial. Leukemia. 2022;36(7):1825–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cortes JE, Saglio G, Kantarjian HM, Baccarani M, Mayer J, Boque C, et al. Final 5-year study results of DASISION: the dasatinib versus imatinib study in treatment-naive chronic myeloid leukemia patients trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(20):2333–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hochhaus A, Saglio G, Hughes TP, Larson RA, Kim DW, Issaragrisil S, et al. Long-term benefits and risks of frontline nilotinib vs imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: 5-year update of the randomized ENESTnd trial. Leukemia. 2016;30(5):1044–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kantarjian HM, Hughes TP, Larson RA, Kim DW, Issaragrisil S, le Coutre P, et al. Long-term outcomes with frontline nilotinib versus imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: ENESTnd 10-year analysis. Leukemia. 2021;35(2):440–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Scemblix (asciminib) [package insert]. East Hanover NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2023.

- 12.Novartis Europharm Limited. Scemblix (asciminib) [summary of product characteristics]. Dublin, Ireland: Novartis Europharm Limited. 2024.

- 13.Hughes TP, Mauro MJ, Cortes JE, Minami H, Rea D, DeAngelo DJ, et al. Asciminib in chronic myeloid leukemia after ABL kinase inhibitor failure. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(24):2315–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mauro MJ, Hughes TP, Kim D-W, Rea D, Cortes JE, Hochhaus A, et al. Asciminib monotherapy in patients with CML-CP without BCR::ABL1 T315I mutations treated with at least two prior TKIs: 4-year phase 1 safety and efficacy results. Leukemia. 2023;37(5):1048–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manley PW, Barys L, Cowan-Jacob SW. The specificity of asciminib, a potential treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia, as a myristate-pocket binding ABL inhibitor and analysis of its interactions with mutant forms of BCR-ABL1 kinase. Leuk Res. 2020;98: 106458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rea D, Mauro MJ, Boquimpani C, Minami Y, Lomaia E, Voloshin S, et al. A phase 3, open-label, randomized study of asciminib, a STAMP inhibitor, vs bosutinib in CML after 2 or more prior TKIs. Blood. 2021;138(21):2031–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wylie AA, Schoepfer J, Jahnke W, Cowan-Jacob SW, Loo A, Furet P, et al. The allosteric inhibitor ABL001 enables dual targeting of BCR–ABL1. Nature. 2017;543(7647):733–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hochhaus A, Réa D, Boquimpani C, Minami Y, Cortes JE, Hughes TP, et al. Asciminib vs bosutinib in chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia previously treated with at least two tyrosine kinase inhibitors: longer-term follow-up of ASCEMBL. Leukemia. 2023;37(3):617–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hochhaus A, Wang J, Kim DW, Kim DDH, Mayer J, Goh YT, et al. Asciminib in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(10):885–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes T, Cortes JE, Réa D, Mauro MJ, Hochhaus A, Kim D-W, et al. P704: Asciminib provides durable molecular responses in patients (pts) with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase (CML-CP) with the T315I mutation: updated efficacy and safety data from a phase I trial. HemaSphere. 2022;6:599–600. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cortes J, Lang F, Kim D-W, Réa D, Mauro MJ, Minami H, et al. Combination therapy using asciminib plus imatinib (IMA) in patients (pts) with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML): results from a phase 1 study. HemaSphere. 2019;3(S1):397. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hehlmann R, Muller MC, Lauseker M, Hanfstein B, Fabarius A, Schreiber A, et al. Deep molecular response is reached by the majority of patients treated with imatinib, predicts survival, and is achieved more quickly by optimized high-dose imatinib: results from the randomized CML-study IV. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(5):415–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen KK, Du TF, Wu KS, Yang W. First-line treatment strategies for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia: a network meta-analysis. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:3891–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.ClinicalTrials.gov. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05384587.

- 25.ClinicalTrials.gov. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05456191.

- 26.ClinicalTrials.gov. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04971226.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Novartis is committed to sharing access to patient-level data and supporting clinical documents from eligible clinical trials with qualified external researchers upon request. These requests are reviewed and approved by an independent review panel based on scientific merit. All data provided are anonymized to respect the privacy of patients who have participated in the trial consistent with applicable laws and regulations. The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current trial are available according to the criteria and process described on www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com.