Abstract

Background

Rare diseases often entail significant challenges in clinical management and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) assessment. HRQoL assessment tools for rare diseases show substantial variability in outcomes, influenced by disease heterogeneity, intervention types, and scale characteristics. The variability in reported quality of life (QoL) improvements following interventions reflects a need to evaluate the effectiveness of HRQoL assessment tools and understand their suitability across diverse contexts.

Objective

This systematic review aims to analyse the effectiveness of various assessment scales in evaluating QoL and explores the general trends observed in the studies using the same and different assessment scales on rare diseases.

Methods

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across various databases to identify studies that reported QoL outcomes related to interventions for rare diseases. Search terms included various synonyms, and both the generic and specific terms related to rare diseases and QoL. Key variables, including intervention types, patient demographics, study design, and geographical factors, were analysed to determine their role in influencing the reported HRQoL outcomes. The findings were then compared with existing literature to identify consistent patterns and discrepancies.

Results

A total of 39 studies were included, comprising randomised controlled trials, observational studies, and cohort studies, with 4737 participants. Significant variations were observed in QoL improvements across studies, even when using the same assessment scales. These differences were primarily attributed to the heterogeneity in disease severity, intervention types, and patient characteristics. Studies employing disease-specific scales reported more nuanced outcomes than generic ones. Additionally, methodological differences, including study design and intervention type, contributed to variations in results and geographical factors influencing patients’ perceptions of health and well-being.

Conclusion

The reported differences in QoL outcomes across studies can be explained by a combination of factors, including disease heterogeneity, treatment modalities, patient demographics, and assessment scale characteristics. These findings underscore the importance of selecting appropriate HRQoL assessment tools based on the research context and patient population. For more accurate comparisons across studies, it is crucial to consider these factors alongside consistent methodology and cultural adaptability of scales. Future research should focus on developing standardised guidelines for QoL assessments that accommodate the diverse needs of patients with rare diseases.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12955-024-02324-0.

Keywords: Quality of life, Assessment scales, Disease-specific QoL, Rare diseases, Patient-reported outcomes, Treatment

Background

Assessing quality of life (QoL) or health-related quality of life (HLQoL) is vital for evaluating health outcomes in patients with rare diseases, which often pose unique challenges in healthcare delivery. Rare diseases are defined as those affecting fewer than 200,000 individuals in the U.S. or less than 1 in 2,000 in the EU [1, 2]. These conditions can lead to considerable physical, emotional, and financial burdens for patients and their families, underscoring the necessity for reliable and comprehensive tools to measure HRQoL. Practical HRQoL assessments are critical for understanding both the impact of the disease and the efficacy of treatments [3, 4].

Existing literature reveals that the variability in reported QoL improvements following interventions complicates clinical decision-making and treatment evaluation, depending on the type of intervention and the patient population involved [1, 5]. This variability can partially be attributed to the lack of consensus regarding appropriate HRQoL measurement tools. Although various HRQoL assessment scales have been developed, the choice between generic and disease-specific tools to accurately measure QoL in rare diseases remains controversial [2, 6, 7]. Generic scales provide standardised measures that facilitate broad comparisons. In contrast, disease-specific scales can offer more relevant insights into patient experiences, allowing for a better understanding of the quality of life-related to particular conditions [8–10].

Generic tools, such as Europe quality of life-5 dimension (EQ-5D), short-form health survey 36 items (SF-36), and SF-12, offer broad applicability and facilitate comparisons across populations and conditions, making them valuable for policy-making and economic evaluations. However, they often fail to capture the unique challenges faced by patients with rare diseases, such as symptoms specific to the condition or psychological impacts, leading to incomplete or misleading assessments of a patient’s quality of life [11]. On the other hand, disease-specific scales, like individualised neuromuscular quality of life (INQoL) or myasthenia gravis quality of life 15 items revised (MG-QoL15r), offer a more detailed understanding of the specific challenges faced by patients with a particular condition but may lack the generalisability required for broader healthcare policy decisions [12, 13].

Recent studies have demonstrated significant variability in reported QoL improvements depending on the assessment scales used; the study designs employed, and the specific characteristics of the patient populations. For instance, studies using the EQ-5D scale frequently report improvements across multiple domains after intervention, particularly in physical health and general well-being [12, 14]. However, other studies using the same scale have noted only modest or no significant changes, especially in cases where the disease’s impact is primarily psychological or where long-term chronic management is involved [9, 15]. Similarly, disease-specific scales have shown varied results, with some studies indicating substantial QoL improvements post-intervention, while others reveal minimal changes, reflecting the diverse experiences of patients even within the same disease category [16, 17].

These inconsistencies highlight the need for a more nuanced understanding of how QoL outcomes are assessed in rare disease populations. Factors such as patient heterogeneity, differences in disease severity, and variations in the type and duration of interventions all play crucial roles in determining the effectiveness of these assessment tools [18, 19]. Additionally, cultural differences, healthcare access, and the psychological burden of living with a rare condition can further influence QoL outcomes. This underscores the importance of selecting the appropriate scale based on the specific research or clinical context [20, 21].

This systematic review addresses a significant gap in the literature by evaluating the effectiveness and limitations of these tools in the context of rare diseases. Furthermore, it delves into general trends in the reported QoL outcomes across various studies. The review aims to thoroughly understand the factors that influence reported QoL outcomes, such as methodological design, patient characteristics, and the cultural adaptability of measurement scales. These insights are designed to aid researchers and clinicians in selecting appropriate HRQoL tools, thereby enhancing the precision of rare disease management and informing policymaking.

Methods

Materials and methods

In this systematic review, the PRISMA® (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) instructional guidelines [22] was followed to evaluate the effectiveness of measurement scales in assessing patients with rare diseases. The PROSPERO (Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) registered the study protocol with confirmation number CRD42024583835.

Data sources and search strategy

A comprehensive search of electronic databases, including PubMed, EMBASE and SCOPUS, was used as a source from inception to June 2024. Search terms included keywords related to rare diseases and quality of life, rating scales, and outcomes. The search strategy incorporated variations in spelling and grammar (e.g., “Quality of Life,” “HRQoL”) and terms for specific rare disease categories. Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms were also used to capture synonyms and related terms. The search was also manually supplemented with reference lists of included studies and review articles in the field. The complete search terms can be found in Supplementary File 1.

Study selection

Study selection was performed by two independent reviewers (JSD and JL) who screened the title and abstract of the identified articles for eligibility based on the following inclusion criteria: [1] Studies assessing quality of life using any rating scale in patients with rare diseases [2], studies reporting the psychometric properties of the rating scales used [3], studies with participants of all ages, from children to adults, to ensure a comprehensive understanding of quality of life assessment in patients with rare diseases [4], studies with any study design and [5] studies published in English. In contrast, studies were excluded if: [1] they did not assess the quality of life using rating scales or did not report psychometric properties of the rating scales [2], studies published in languages other than English [3], studies that did not consider patients with rare diseases or focused on comorbidities with no relevance to rare diseases [4], studies that evaluated the effectiveness of interventions without detailed evaluation of available HRQoL outcome data, and [5] studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria mentioned. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion until a consensus was reached.

Text screening

The lead author (JSD) carried out an initial evaluation of all titles and abstracts to determine their suitability. Two additional researchers (JL and BA) contributed by independently reviewing the titles and abstracts for relevance. Any uncertainties regarding eligibility were discussed among the reviewers to ensure comprehensive coverage and to minimise the risk of including studies that did not meet the established criteria. Following the initial screening, the same reviewers assessed the full texts of the selected studies to finalise which ones would be included in the systematic review.

Data extraction and analysis

JSD performed data extraction and analysis. The following data points were extracted from the included studies: authors, year of publication, country, study design, sample size, rare diseases included, the rating scale used, psychometric properties of the rating scale, intervention type, and key outcomes. The extracted data were further reviewed and analysed independently by two reviewers (JL and BA). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion to ensure the completeness of extracted information.

Data synthesis

A narrative synthesis was performed based on the extracted data. The synthesis assessed the reliability, validity and applicability of HRQoL rating scales used to assess patients with rare diseases. Because no effect measures were used, quantitative analysis was not applicable. No meta-analysis was performed as most of the articles extracted were single-arm interventions and post hoc analyses of previous RCT data. High heterogeneity was expected due to the broad inclusion criteria and the inclusion of multiple measurement scales in each study. Therefore, the heterogeneity of the studies was not assessed. Likewise, no sensitivity analyses were carried out.

Risk of bias assessment

The study protocol reported a risk of bias assessment using the JBI critical appraisal tools for systematic reviews and research syntheses. These provided a more comprehensive range of checklists [23]. It contains 11 questions that, in rare cases, should be answered with “Yes,” “No,” “Unclear,” and “Not applicable.” No meta-bias was analysed as the results of the studies were not of interest due to the heterogeneity of the outcome variables. Additionally, we employed the COSMIN (Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments) framework to evaluate psychometric properties [24]. For simplicity, we focused our ratings on the reliability, validity and responsiveness of the HRQoL instruments utilised since our focus was on effectiveness and general trends in reported patients’ QoL outcomes.

Results

General characteristics of data

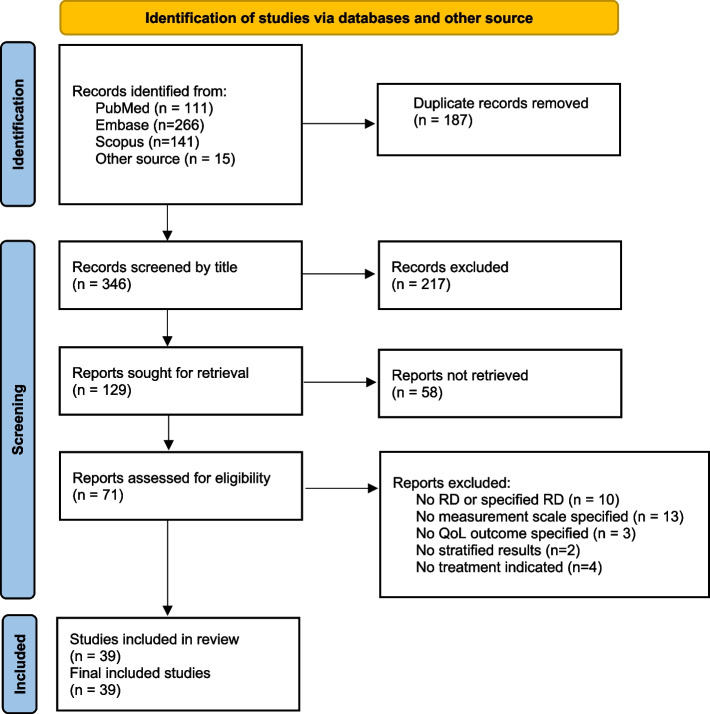

Figure 1 illustrates the study selection process for the systematic review, encompassing 39 studies, including two sets of interconnected reports. Karaa et al. published two papers on the treatment of primary mitochondrial myopathy (PMM) with elamipretide in 2020 and 2023, respectively. Table 1 provides an overview of the study characteristics, encompassing 4737 participants across the 39 included studies. Among these, 21 studies were randomised controlled trials (RCTs), 6 were observational cohort studies, 3 were cross-sectional studies, 4 were posthoc analyses, 2 were prospective studies, 1 was a pilot study, and 2 had other study designs (Supplementary file 2). Within the 21 RCTs, 14 utilised double-blind randomisation [11, 13, 14, 19, 25–34]; four employed open-label randomisation [12, 18, 35, 36]; one had a prospective design [37]; and two did not specify the type of randomisation [3, 4].

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart showing the identification and screening of included studies

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Year | Country/Region | Design | Population | Disease | Scale | Intervention | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saccà (2023) [14] | 2023 | Multiple | RCT | 129 | MG | MG-QOL15, ED-5D-3L, VAS, QMG | Treatment | Significant improvements in MG-specific clinical scale scores; Significant improvements in HRQoL measures that were maintained in the second treatment cycle; Improvement in HRQoL paralleled changes in immunoglobulin G level |

| Kreuter (2020) [15] | 2020 | Germany | Post-hoc analyses in INPULSIS® trials | 1061 | IPF | SGRQ, UCSD-SOBQ, EQ-5D VAS, CASA-Q | Treatment | Greater decline in FVC % predicted over 52 weeks was associated with significant worsening of HRQoL & symptoms; Nintedanib slowed deterioration in several PROs compared to placebo, with the most significant benefit observed on the SGRQ |

| Kamath (2023) [38] | 2023 | Canada | Analysis from the ICONIC trial | 27 | Alagille syndrome | PedsQL, MFSS | Treatment | Responders showed a mean change in Multidimensional Fatigue score compared to nonresponders; Changes in PedsQL Generic core and Family Impact scores were smaller and not significant; Responders' Family Impact scores increased compared with nonresponders |

| Goeldner (2022) [19] | 2022 | Multiple | RCT | 170 | Down syndrome | BRIEF-P, CELF-4, PedsQL | Treatment | Participants showed improvement on the primary composite endpoint across treatment arms; No significant differences between placebo and Basmisanil-treated groupss in individual measures |

| Chang (2020) [18] | 2020 | China | RCT | 15 | PKAN | PedsQL | Treatment | Quality of life of family members improved after pantethine treatment; Quality of life of patients remained unchanged at week 24 |

| Boon (2020) [8] | 2020 | Europe | open label clinical trial | 171 | CF | CF-PedsQLGI, CFQR, CFAbd-Score, VAS | Treatment | Self-reported CF-PedsQL-GI scores improved significantly from month 0 (M0) to month 6 (M6); Parents reported similat improvements; Patients with lower baseline CF-PedsQL-GI scores showed greater improvement at M6 |

| Vissing (2020) [13] | 2020 | Multiple | RCT | 117 | MG | MG-QOL15, MG-ADL | Treatment | Eculizumab-treated patients achieved 'minimal symptom expression' compared to placebo; During the open-label extension, patients in the placebo/eculizumab group achieving 'minimal symptoms expression' increased after eculizumab treatment; Patients in the eculizumab/eculizumab and placebo/eculizumab groups achieved 'minimal expression' at extension study week 130 |

| Arnold (2018) [20] | 2018 | Canada | Analysis from the faSScinate trial | 87 | SSc | HAQ-DI, VAS | Treatment | 33% of patients achieved PASS for all three PASS questions, increasing to 69%, 71%, and 78% at 96 weeks; Changes in PASS scores exhibited moderately negative correlations with HAQ-DI and patients and physician global assessments, indicating expected improvements with improved PASS |

| Statland (2012) [25] | 2012 | Multiple | RCT | 59 | NDMs | INQOL-QOL, SF-36 | Treatment | Mexiletine improved patient-reported severity score stiffness on the IVR diary compared to placebo; Mexiletine improved the INQOL-QOL score and decreased handgrip myotonia on clinical examination |

| Heřmánková (2023) [17] | 2023 | Czech Republic | Pilot study | 16 | SSc, IIM | SQoL-F, HAQ, SF-36, BDI-2 | Physical therapy | Significant improvements were observed in the total scores of FSFI and BISF-W; Functional status and the physical component of QoL in intervention group improved compared to control group |

| Cella (2018) [11] | 2018 | USA, Europe | RCT | 135 | NETs | QLQ-C30, QLQ-GINET21 | Treatment | DRs during the DBTP showed greater symptom improvements and maintained more meaningful QoL improvements compared to DBTP-NDRs |

| Wilson (2024) [39] | 2024 | Europe, USA | Cross-sectional study | 61 | PNH | FACIT-Fatigue, EQ-5D-5L, SF-36 | Treatment | Physician-perceived fatigue was lower, and HRQoL was better in patients; High treatment satisfaction (> 90%) was reported by both physicians and patients; PEG was preferred over previously prescribed C5 complement inhibitors |

| Lumry (2021) [12] | 2021 | Multiple | RCT | 126 | HAE | AE-QoL, HAE-QoL, EQ-5D, HADS, WPAI, TSQM | Treatment | Patients receiving C1-INH(SC) 60 IU/kg demonstrated significant improvement in EQ-5D & VAS; Significant improvements observed in HADS anxiety and depression scales, WPAI-assessed presenteeism work productivity loss, and activity impairment; Clinically important improvements achieved in > 25% of patients for all domains except WPAI-assessed absenteeism; Mean Ae-QoL total score indicated less impairment, and mean HAE-QoL global scores were close to the maximum possible score |

| van Egmond (2017) [14] | 2017 | Netherlands | Observational prospective study | 4 | NSPME | PedsQL, UMRS | Atkins diet | Considerable improvement in HRQoL in one patient, sustained improvement during long-term follow-up; HRQoL remained unchanged in 3 patients, who discontinued the diet; Seizure frequency remained stable, modest improvement in blinded rating of myoclonus in all patients |

| Kim (2012) [40] | 2012 | South Korea | Observational study | 22 | Achondroplasia | RSS, SF-36, PedsQL | Surgical intervention | The surgical group exhibited higher Rosenberg self-esteem scores compared to the nonsurgical group; There were no differences in AAOS and SF-36 scores; Self-esteem scores decreased with an increase in the number of complications |

| Gloeckl (2020) [41] | 2020 | Germany | Prospective observational study | 58 | LAM | 6MWD, SF-36 | Rehabilitation | Following PR, there was a significant increase in exercise performance; Significant improvement in quality of life |

| De Luca (2020) [42] | 2020 | Italy | Prospective observational study | 12 | BD | BDQOL, BSAS, VAS, BDCAF | Treatment | Significant reduction in number of OUs after 12 weeks of apremilast treatment; Improvement in disease activity: BSAS, BDCAF score, VAS pain score, and BDQOL; Clinical improvement led to complete steroid discontinuation in 6 patients & prednisone dose tapering in 2 patients |

| Gelbard (2020) [43] | 2020 | USA | cohort study | 810 | iSGS | VHI-10, EAT-10, SF-12 | Surgical intervention | Cox proportional hazards regression models showed ED was inferior to ERMT; Patients treated with CTR had the best Clinical COPD questionnaire and SF-12 scores, but worst Voice Handicap Index-10 score |

| Rombach (2013) [44] | 2013 | Netherlands | Cost-effectiveness analysis | 142 | Fabry disease | EQ-5D | Treatment | Untreated Fabry patients over a 70-year lifetime generate 55.0 years free of end-organ damage and 48.6 QALYs; Starting ERT in symptomatic patients increases the number of years free of end-organ damage by 1.5 years, with a similar increase in QALYs; Costs of ERT starting in the symptomatic stage range between €9-€10 million during a patient's lifetime |

| Cleary (2021) [16] | 2021 | UK | follow-up analysis | 55 | MPS | MPS-HAQ, EQ-5D-5L, APPT, BPI, BDI, 6MWT | Treatment | Mean 6-min walk test distance increased from 217 m at baseline to 244 m after a mean follow-up of 4.9 years; Improvement or stabilisation was observed regardless of age at treatment initiation or duration of treatment; Mean forced vital capacity and forced expiratory volume in 1 s showed improvement from baseline to follow-up; PRO data demonstrated overall improvements over time |

| de Hosson (2019) [35] | 2019 | Netherlands | RCT | 91 | NET | QLQ-INFO25 | Support system | There was no significant difference in distress, perception of information, or satisfaction between the intervention and control groups; Access to WINS did not provide additional value compared to standard care |

| Hammer (2018) [37] | 2018 | Belgium | RCT | 19 | SFVM | SF-36, PEDSQL, VAS | Treatment | Patients showed significant and rapid improvement in symptoms and quality of life; Sirolimus treatment enabled sclerotherapy and surgery in 2 patients who initially deemed unsuitable for these interventions |

| Riera (2011) [28] | 2011 | Brazil | RCT | 24 | SSc | HAQ | Treatment | No significant difference b/t the lidocaine and placebo groups for any outcome after treatment and 6-month follow-up; Reported improvement in modified Rodman skin score in 66.7% and 50% of placebo and lidocaine groups, respectively; Both groups showed improvement in subjective self-assessment, with no difference between them |

| Depping (2021) [3] | 2021 | Germany | RCT | 89 | RDs | HEIQ, GADS, SSQ, SF-12, IPQ, PHQ-9 | Self-help bood & telephone couselling | The intervention group showed significantly higher rates of acceptance of the disease compared to the CAU group; Coping strategies, social support, and mental quality of life, were significantly higher in the intervention group compared to the control group |

| Dittrich (2019) [27] | 2019 | Germany | RCT | 38 | DMD | Kiddo-KINDL | Treatment | Cox regression adjusted for LV-FS after run-in showed a non-significant benefit for medication over placebo; No significant difference between tretments was observed for quality of life; One DMD patient experienced reversible deterioration of walking abilities during the run-in period |

| Lortholary (2017) [34] | 2017 | Multiple | RCT | 129 | SM | HADS/HAMD, FIS | Treatment | Masitinib associated with a cumulative response of 18.7% in the primary endpoint compared with 7.4% for placebo; Frequent severe adverse events (> 4% difference from placebo) included diarrhoea, rash, and asthenia |

| Lukina (2019) [45] | 2019 | USA, Europe | Post-hoc analyses from phase 2 trial | 19 | GD1 | DS3, SF-36, FSS | Treatment | Mean lumbar spine T-score increased, moving from osteopenic to the normal range; Mean QoL scores improved and moved into ranges seen in healthy adults |

| Griese (2022) [26] | 2022 | Germany | RCT | 35 | chILD | chILD-QoL,6-MWT | Treatment | No significant difference in the primary endpoint or secondary endpoints between placebo and HCQ groups; HCQ was well tolerated, with no significnt difference in adverse evets between placebo and HCQ groups |

| Thompson (2022) [33] | 2022 | Canada | RCT | 13 | HHT | ESS | Treatment | No significant difference in change in weekly epistaxis duration or frequency between treatment and placebo; Ferritin levels not significantly different between treatment and placebo; No significant difference in RBC transfusions between treatment periods |

| Karaa (2023) [30] | 2023 | Multiple | RCT | 218 | PMM | 6MWT, PMMSA, TFS, Neuro-QoL | Treatment | Primary endpoints not met: Difference in least squares mean (SE) from baseline to week 24; Elamipretide treatment well-tolerated, with most adverse events mild to moderate in severity |

| Karaa (2020) [31] | 2020 | USA | RCT | 30 | PMM | PMMSA, Neuro-QoL, 6MWT | Treatment | Elamipretide-treated participants walked 398.3 m on 6MWT compared to 378.5 m in placebo group; PMMSA and Total Fatigue During Activities scores showed less fatigue and muscle complaints with elamipretide; Neuro-QoL Fatigue Short Form and Patient Global Assessment also showed reductions in symptoms; No significant change in Physician Global Assessment, Triple Timed Up and Go test, or wrist/hip accelerometry |

| Mulas (2023) [46] | 2023 | Italy | Cross-sectional study | 43 | Thalassemia | PedsQL | HSCT | Transfused patients showed a significant reduction in HRQoL compared to transplanted patients in PedsQL domains; HSCT was significantly associated with higher total child PedsQL score and higher total parent PedsQL score; A significant positive correlation between the children and parents reported scores across all PedsQL domains |

| Schramm (2022) [32] | 2022 | Germany | RCT | 61 | PBC | PBC-40, VAS | Treatment | By Day 28, tropifexor caused 26–72% reduction in GGT from baseline; Day 28 QoL scores comparable between placebo and tropifexor groups |

| Zhang (2023) [49] | 2022 | China | Cross-sectional study | 56 | IIMs | MMT8, HAQ, SF-36 | Rehabilitation | Both groups showed improved MMT8, FI-2, HAQ, and SF-36 scores after 12 weeks of physical therapy |

| Tutus (2024) [4] | 2024 | Germany | RCT | 74 | RDs | GAD-7, FoP-Q-SF, PHQ-9, ULQIE, CHIP-D | Physical therapy | Significant improvements in the WEP-CARE group for anxiety, fear of disease progression, depression and coping; The benfits regarding anxiety, fear of disease progression, and coping were sustained at the 6-month follow-up; No significant group difference was found for quality of life; High levels of satisfaction were reported by both participating parents and therapists in the WEP-CARE programme |

| Shaikh (2014) [47] | 2014 | USA | Prospective study | 4 | AAD | BFM, TWSTRS, SF-36 | Deep brain stimulation (DBS) | GPi DBS improved BFM scores by 87.63 ± 11.46%; Improvement in the total severity scale of TWSTRS was 71.5 ± 12.7%; Quality of life showed remarkable improvement |

| Yushan (2022) [48] | 2022 | China | Retrospective observational study | 84 | Wrist TB | VAS, EQ-5D-5L | Surgical intervention | Significant improvements were noted at follow-up; QuickDASH and PRWHE scores decreased, indicating improved function; Enhanced health-related quality of life; All patients reported a good recovery of wrist function at the last follow-up |

| Wang (2022) [29] | 2022 | Multiple | RCT | 94 | AHP | SF-12, VAS, EQ-5D | Treatment | Givosiran reduced the number and severity of attacks, days with worst pain scores above baseline, and opioid use |

| Khan (2024) [36] | 2024 | USA, Canada | RCT | 22 | HPT | HypoPT-SD, EQ-5D-5L, VAS, PGI-S | Treatment | Mean 24-h urine calcium excretion decreased from baseline to EOT; Supplemental doses of calcium and active vitamin D were significantly reduced from baseline; Bone turnover markers increased 2–fivefold from baseline, indicating a positive impact on bone health; HRQoL and disease-related symptoms improved numerically, with reduced healthcare resource utilisation; 40.9% of patients reported treatment-related adverse events, with no reported deaths |

6MWD/T 6 min walk distance/test, AAD Adult-onset axial dystonia, AAOS American Academy of orthopaedic surgeons, AE-QoL Angioedema quality of life, APH Acute hepatic porphyria, APPT Adolescent and paediatric pain tool, BD Behcet disease, BDCAF Behcet disease current activity form, BDI-2 Beck depression inventory-second version, BISF Brief index of sexual functioning for women, BPI Brief pain inventory, BDQoL Behcet disease quality of life, BFM Baurke-Fahn-Marsden, BRIEF-P Behaviour rating inventory of executive functioning-preschool, BSAS Behcet syndrome activity score, CASA-Q Cough and sputum assessment questionnaire, CAU Care as usual, CELF-4 Clinical education

of language fundamental-4, CF Cystic fibrosis, CF-PedsQL GI Cystic fibrosis paediatric quality of life inventory gastrointestinal symptom scales, chILD Children with interstitial lung disease, chILD-QoL chidren's interstitial lung disease quality of life, CHIP Coping with health injuries and problem scale, CTR Cricotracheal resection, DBTP-NDRs Double-blind treatment period-non durable responders, DMD Duchenne muscular dystrophy, DS3 Gaucher disaese severity scoring system, EAT-10 Eating assessment test-10, ED Endoscopic dilation, ERMT Endoscopic resection with adjuvant medical therapy, ERT Enzyme replacement therapy, ESS Epistaxis severity scale, EOT End of treatment, EORTC QLQ-C30 European organisation for research and treatment for cancer quality of life questionnaire-30, EORTC QLQ-GINET 21 European organisation for research and treatment for cancer quality of life with gastrointestinal endocrine tumours 21-items, EQ-5D-3L/5L Europe quality of life 3 dimension/5 dimension, FACIT Functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue, FIS Fatigue impact scale, FOP-Q-SF Short form of the Fear of progression questionnaire, FSFI Female sexual function index, FSS Fatigue severity scale, GAD-7 Generalised anxiety disorder-7, GADS Generalised anxiety disorder scale, GD1 Gaucher disease type 1, HAE Hereditary angioedema, HAE-QoL Hereditary angioedema quality of life, HADS Hospital anxiety and depression scale, HAMD Hamilton anxiety/depression rating scale, HAQ Health assessment questionnaire, HAQ-DI Health assessment questionnaire disability index, HCQ Hydroxychloroquine, HEIQ Health education illness questionnaire, HHT Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia, HPT Hypoparathyroidism, HypoPT-SD Hypoparathyroidism symptom diary, iSGS idiopathic subglottic stenosis, IIM Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, INQoL Individualised neuromuscular quality of life, IPF Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, IPQ Illness perception questionnaire, LAM Lymphangioleiomyomatosis, MFSS Multidimensional fatigue scale score, MG Myasthenia gravis, MG-ADL Myasthenia gravis activity of daily living, MG-QoL-15r Myasthenia gravis quality of life 15-items revised version, MMT8 Manual muscle testing 8, MPS Mucoplosaccharidosis, MPS-HAQ Mucopolysaccharidosis health assessment questionnaire, NDMs Nondystrophic myotomias, Neuro-QoL Quality of life in neurological disorders, NET Neuroendocrine tumour, NSPME North sea progressive myoclonus epilepsy, PASS Patient acceptable symptom state, PBC Primary billiary cholangitis, PBC-40 Primary billiary cholangitis-40 items, PedsQL Paediatric quality of life inventory, PHQ-9 Patient health questionnaire-9, PGIS Patient global impression severity scale, PKAN Pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration, PMM Primary mitochondrial myopathy, MMSA Primary mitochondrial myopathy symptom assessment, PNH Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria, QMG Questionnaire myasthenia gravis scoring system, RCTs Randomised control trials, RDs Rare diseases, RSS Rosenberg self-esteem scale, SF-12 Short form health survey 12 items, SF-36 Short form health survey 36 items, SFVM Slow-flow vascular malformation, SGRQ St George respiratory questionnaire, SQoL-F Sexual quality of life-female, SM Systemic mastocytosis, SSC Systemic sclerosis, SSQ Social support questionnaire, TB Tuberculosis, TFS Total fatigue scale, TSQM Treatment satisfaction questionnaire for medication, TWSTRS Toronto Western spasmodic torticollis rating scale, USD-SOB University of California San Diego shortness of breath, ULQIE Ulm quality of life inventory for parents, UMRS Unified myoclonus rating scale, VAS Visual analogue scale, VHI-10, Voice handicap index 10, WPAI Work productivity and activity impairment, WINS Web-based, personalised information ans support system

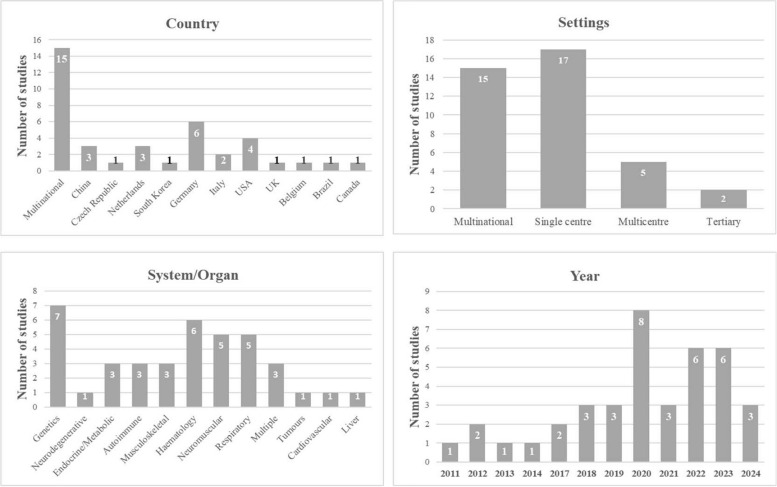

Geographically, most studies were conducted in multiple countries (Fig. 2). Specifically, there were six studies in Germany [3, 4, 15, 26, 27, 41]; four in the USA [31, 36, 43, 47]; three in China [18, 48, 49]; three in the Netherlands [35, 44, 50]; two in Italy [42, 46]; and one each in the UK [16], Belgium [37], Czech Republic [17], Canada [33], Brazil [28], and South Korea [40]. Seventeen studies were performed in a single-centre setting, two in a tertiary setting, five were multicenter, and 15 were multinational (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The number of included studies according to country, settings, system/organ and publication year

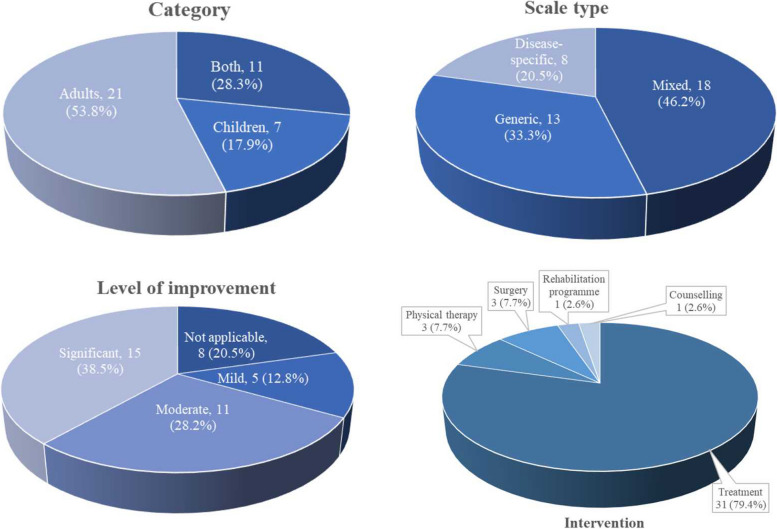

As depicted in Fig. 2, seven studies exclusively addressed genetic-related diseases, six focused on haematological diseases, five on neuromuscular diseases, five on respiratory diseases, and three on endocrine/metabolic, musculoskeletal, and autoimmune diseases. Additionally, one study each focused on cardiovascular, liver, tumour, and neurodegenerative diseases, and three studies involved multiple rare diseases. Regarding interventions, three studies were related to physical therapy, three to surgical interventions, one to a rehabilitation programme, one on self-help books and telephone counselling, and the rest were medication treatment interventions (Fig. 2). Furthermore, 21 studies focused on adult patients, seven on children, and eleven on adult and child patients (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Percentage of included studies for category, scale type, level of improvement and intervention type

Assessment of measurement scales

In total, 13 studies used generic scales to assess the quality of life following an intervention, while eight used disease-specific scales, and 18 employed both generic and disease-specific scales (Fig. 3). Studies that utilised both types of scales demonstrated similar overall health improvement in patients with rare diseases [14, 25]. Whereas other studies identified in this review reported minor differences in overall health improvement after the intervention [18, 28]. The most frequently used generic scales included EQ-5D, SF-36, visual analogue scale (VAS), paediatric quality of life inventory (PedsQL), patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), and SF-12; the characteristics of most of these measurement scales are detailed in Table 2. EQ-5D was the most used generic scale for assessing the quality of life in patients with rare diseases. Regarding interventions (including medications, physical therapy, rehabilitation, surgery, etc.), most of the included studies reported a significant improvement in quality of life after treatment, while others indicated no substantial improvement or no change from baseline parameters. This highlights the likelihood that generic scales for quality-of-life assessment vary across diseases and may not adequately capture or evaluate the main features specific to each disease type.

Table 2.

Characteristics of some measurement scales

| Scale | Domain/subscale | Description | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-36 | Physical Functioning (PF), Role Physical (RP), Bodily Pain (BP), General Health (GH), Vitality (VT), Social Functioning (SF), Role Emotional (RE), Mental Health (MH) | It is a widely used health-related quality of life (HRQoL) questionnaire that assesses physical and mental well-being across multiple dimensions. Each dimension of its subdomains is scored on a scale from 0 to 100, where higher scores represent better health status. Summary scores for physical and mental health can be derived | It is applicable across a wide range of diseases, populations, and settings, allowing for comparisons between different groups; Its 8 dimensions offer a detailed view of both physical and mental health, providing a holistic assessment; It is recognised internationally and has been translated into numerous languages; Extensive normative data exist for many populations, enabling comparison with general or specific subgroups; It is relatively easy to understand and can be completed quickly | It may be burdensome for some respondents, particularly those with severe illness or cognitive impairments; Scoring and interpreting results require familiarity with its structure, especially when deriving summary scores; Cultural differences may affect how questions are interpreted and the relevance of certain items, despite translations; It it may not fully capture disease-specific concerns, which is crucial in conditions like haemophilia; It responses may be influenced by personal bias, social desirability, or response styles |

| HAQ-DI | Dressing & grooming, arising, eating, walking, hygiene, reach, grip, and activities | It is a widely used instrument in the assessment of physical functioning and disability, particularly in patients with chronic conditions like rheumatoid arthritis. It specifically assesses physical functioning and disability rather than general health status. The total score range from 0 to 3, where a higher score indicates greater disability | It is particularly sensitive in detecting changes in disability over time in patients with chronic musculoskeletal diseases, making it highly relevant in clinical studies and trials; It is relatively simple and quick to administer, making it practical for both clinical and research settings; Apart from rheumatoid arthritis, it has been adapted for use in a variety of other chronic conditions; It has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, including reliability and validity; The scale’s consideration of aids and devices provides a more comprehensive picture of a patient’s functioning | It focuses predominantly on physical functioning rather than other important aspects of HRQoL (mental health, pain, social functioning); It can have ceiling effects (where many patients score low, suggesting no disability) and floor effects (where many patients score high, suggesting severe disability); It may be interpreted differently across cultures, and the relevance of some activities may vary depending on cultural practices, even with translation and adaptation; It is subject to patient bias, where responses might be influenced by mood, perception, or social desirability; It primarily targets adults and may not be as suitable for populations such as children or those without rheumatic diseases |

| MG-QOL15r | Physical functioning, fatigue, emotional well-being, and social participation | It is a patient-reported outcome measure specifically designed to assess QoL in individuals with myasthenia gravis (MG). The questionnaire is designed to capture the patient's perspective on how MG affects their daily functioning and well-being. The total score ranges from 0 to 60, with higher scores reflecting a worse quality of life | It is tailored specifically for MG, making it more relevant and sensitive to the unique challenges faced by patients with this condition; It is quick and easy to complete, reducing response burden while still capturing critical information; It is a trusted tool for both clinical practice and research; It is sensitive to changes over time, allowing healthcare providers to monitor patient improvement or decline in QoL after interventions; The scale is a direct measure of the patient’s experience and perception of their QoL, emphasising areas most impacted by MG | It may not capture broader QoL factors unrelated to MG that could affect patients; Responses are based on self-reporting, which can be subjective and influenced by the patient's mood, perception, or understanding of their condition; it cannot be used for cross-condition comparisons or general population studies; Some patients may misunderstand the questions or may not fully relate to the items due to varying severity and presentation of MG symptoms; Cultural differences may affect how questions are interpreted and answered, potentially influencing the reliability of cross-cultural comparisons |

| EQ-5D | Mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression | It is a standardised instrument used to measure HRQoL. It was developed by the EuroQol Group and is particularly useful for economic evaluations, clinical assessments, and health-related research. Each dimension has 3 levels (EQ-5D-3L) or 5 levels (EQ-5D-5L) of severity (e.g., no problems, some problems, extreme problems). The index score ranges from less than 0 (where 0 indicates a state equivalent to death and negative values indicate health states worse than death) to 1 (perfect health) | It is simple, quick, and easy to administer, making it highly practical for both large-scale population surveys and clinical studies; It is a generic measure applicable across different diseases, conditions, and populations. It is used in health economics, clinical trials, and real-world studies; It is available in many languages and has been validated for use in numerous countries, allowing for cross-cultural comparisons; The availability of the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L versions allows for flexibility depending on the precision required; The index score derived from the descriptive system can be used in health economic evaluations, such as cost-utility analysis, where quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) are calculated | The EQ-5D may lack sensitivity in capturing disease-specific issues, particularly in conditions with complex symptomatology or rare diseases; It may show a high percentage of respondents with perfect health scores, reducing its ability to detect small but important changes; The VAS component, while straightforward, is highly subjective and can be influenced by respondents’ mood, recent experiences, or understanding of “best” and “worst” imaginable health; The valuation of health states can differ across cultures and may require country-specific value sets, which are not always available; It captures only five broad dimensions of health, potentially missing other relevant aspects such as social functioning, energy levels, or mental health complexities |

| HADS | Anxiety, depression | It is a widely used questionnaire designed to assess levels of anxiety and depression in patients, particularly in hospital settings. It was originally developed for use in non-psychiatric medical settings and has been extensively validated for various populations. It is widely used in both clinical practice and research. Each subscale can score from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating higher levels of anxiety or depression | It is particularly useful in hospital or outpatient settings where physical symptoms may overlap with psychological symptoms, helping to minimise confounding somatic conditions; The distinct anxiety and depression subscales allow for the separate evaluation of these two common psychological states; It has been validated across various populations and conditions, including chronic diseases; It is concise and straightforward, and easy to interpret; It effectively identifies individuals who may require further psychological assessment; It focuses on emotional symptoms, which are less likely to be influenced by physical illness, enhancing its accuracy in patients with coexisting medical conditions | The HADS only measures anxiety and depression, so it doesn’t capture other important mental health dimensions like stress, anger, or social functioning; It may not be as sensitive or specific as other scales that are tailored specifically for anxiety or depression; It may demonstrate a ceiling effect, resulting in limited sensitivity to detect changes in symptoms among higher-functioning individuals; The reliability and validity of the HADS may vary in certain demographic or clinical populations, necessitating caution in interpretation; It responses can be influenced by individual perceptions, social desirability, and the context of the assessment, which can result in variability |

| SF-12 | Physical Functioning (PF), Role Physical (RP), Bodily Pain (BP), General Health (GH), Vitality (VT), Social Functioning (SF), Role Emotional (RE), Mental Health (MH) | It is a widely used instrument for measuring HRQoL. It is a shorter version of the SF-36, designed to provide a more concise assessment while still capturing key aspects of health status. It produces two summary scores: Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS). The responses are transformed into a scoring algorithm that provides the PCS and MCS scores, typically ranging from 0 to 100, where higher scores indicate better health | It is shorter than the SF-36, making it easier to administer and quicker for respondents to complete, which increases response rates in both clinical and survey settings; It is well-validated and widely used across various populations, allowing for comparisons across studies and populations; The two composite scores (PCS and MCS) allow for easy comparison of physical and mental health across different groups or studies; It is considered sensitive enough to detect changes in health status over time; It requires fewer resources in terms of time and respondent burden, making it cost-effective for use in large studies or routine clinical practice; It has been translated into many languages and culturally adapted | It may not provide the depth of information or specificity that a longer instrument like the SF-36 offers, limiting its ability to detect specific health issues; It may be less sensitive than the SF-36 in detecting subtle changes in health status or differences in specific populations; It may exhibit a ceiling effect in high-functioning individuals, where many respondents report high levels of health, limiting sensitivity to changes or subtle declines; Its scoring algorithm is complex and often requires software, making it less straightforward to interpret than simpler questionnaires; The results can be influenced by personal perceptions, bias, and response styles, which can impact the accuracy of the reported health status |

| WPAI | Absenteeism, presenteeism, work productivity loss, activity impairment | It is a widely used tool designed to assess the impact of health problems on work productivity and daily activities. It is particularly valuable in studies assessing the burden of diseases, evaluating treatment effects, and in health economics research. Its outcomes are expressed as impairment percentages, with higher numbers indicating more significant impairment and less productivity | It evaluates both absenteeism and presenteeism, providing a holistic view of how health issues affect work productivity; It is sensitive enough to detect changes in productivity and activity impairment over time; It can be adapted for different diseases and health conditions; It provides standardised measures of work and activity impairment, facilitating comparisons across different studies, populations, and conditions; It is straightforward, quick to administer, and requires minimal training to interpret; It is highly relevant in health economic evaluations, where it is used to calculate the economic burden of diseases based on productivity losses | It may not adequately capture all relevant factors affecting productivity in every population or condition, particularly those with complex multifactorial impairments; it does not provide detailed information on the specific health-related factors driving the impairment; It is mainly designed for working populations, limiting its applicability in populations like retirees, students, or those unemployed; In populations with severe health conditions, where individuals might already be out of the workforce, the WPAI may show ceiling effects, limiting its sensitivity in such contexts; Respondents are asked to reflect on their experiences over the past week, which may lead to recall bias if they have difficulty accurately remembering the level of impairment |

| FACIT | Physical well-being, Functional well-being, Social/family well-being, Emotional well-being | It is a set of HRQoL questionnaires used to assess physical, emotional, social, and functional well-being in patients with chronic illnesses. The FACIT system includes disease-, condition-, and treatment-specific subscales that can be added depending on the patient population (e.g., FACIT-F for fatigue, FACT-B for breast cancer). Scores are summed for each domain and can be combined to produce a total score reflecting overall HRQoL. Higher scores indicate better quality of life | The FACIT scales cover multiple aspects of HRQoL, providing a broad, multidimensional understanding of how chronic illness impacts patients; The FACIT scales are sensitive to changes in patients' health status over time, making them useful for evaluating treatment effects and disease progression in clinical trials; The FACIT scales have demonstrated strong reliability and validity across different populations and conditions, confirming their effectiveness as a measure for quality of life; the FACIT scales capture the personal experiences and perspectives of individuals living with chronic illnesses | Some of its versions are disease-specific and may not be appropriate for all populations or conditions; Adding condition-specific subscales can result in a lengthy questionnaire, which may lead to response burden or fatigue, especially in very ill patients; The addition of multiple subscales and the need for specialised scoring software can complicate the interpretation of results; For patients with multiple comorbidities or overlapping symptoms, there might be redundancy in some questions, leading to less precise assessments; Cultural differences in how symptoms or experiences are understood may impact the scale's validity in certain populations |

| HAQ | Dressing and grooming, Arising (getting up from a chair), Eating, Walking, Hygiene, Reach (e.g., reaching for objects), Grip (e.g., gripping things), Activities (e.g., participating in typical household activities) | It is a widely used tool designed to assess the functional status and quality of life in patients with various chronic conditions, particularly those with rheumatic diseases. The HAQ is commonly used in clinical settings and research to evaluate the impact of disease on a patient’s ability to perform daily activities. The scores for each domain are summed and averaged to produce a single HAQ score, with higher scores indicating greater functional impairment | It is a well-established tool with extensive use in clinical practice and research, making it a reliable measure for assessing functional disability; It helps healthcare providers assess functional status over time, tailor interventions, and monitor the effectiveness of treatments, contributing to improved patient care; It is straightforward to use, does not require extensive training, and is a cost-effective tool for measuring disability; It is valuable for tracking disease progression, evaluating treatment outcomes, and conducting research on functional status and disability | The HAQ primarily focuses on functional disability and may not capture other aspects of QoL, such as emotional or social well-being; In some cases, it may not be sensitive enough to detect small but clinically significant changes in functional status over time; The interpretation of some items may vary across different cultural and healthcare contexts, potentially affecting the scale's applicability in diverse populations; In high-functioning individuals or patients with mild disability, there may be a ceiling effect, limiting the scale's ability to capture meaningful changes in functional status |

| PedsQL | Physical functioning, Emotional functioning, Social functioning, School functioning | It is a widely used tool designed to measure HRQoL in children and adolescents. It is beneficial for assessing the impact of health conditions on QoL from the perspective of both the child and their caregivers. The scale provides summary scores for overall HRQoL, and physical and psychosocial health. Items are typically rated on a 5-point Likert scale, and scores are transformed to a standard 0–100 scale, with higher scores indicating better QoL | It is tailored for different developmental stages, with questions and language adjusted for various age groups; It covers both physical and psychosocial functioning, offering a holistic view of a child’s well-being; Its generic and disease-specific modules make it adaptable for various conditions; The availability of both self-report and proxy-report forms allows for comparison between a child’s self-perception and the caregiver’s perspective; It has been widely validated across different populations, showing good reliability, validity, and sensitivity to changes over time; It is concise and straightforward, making it practical for routine clinical use and large-scale research studies | It can be perceived as lengthy, especially when using module versions, which might deter completion in some busy clinical settings; While proxy reports are useful, they may not fully capture the child’s own experiences, particularly for internal states like emotional functioning, where discrepancies between self-report and proxy-report can arise; The instrument primarily relies on self-reporting by children (when developmentally appropriate), which may not always fully capture the nuances of their experiences, especially in younger children who may not fully understand the questions; Due to its brevity, the PedsQL may not delve deeply into specific areas of functioning, which could be a drawback in cases where detailed assessment is needed |

| PHQ-9 | Depressed mood, Anhedonia, Sleep disturbances, Fatigue or low energy, Changes in appetite or weight, Feelings of worthlessness or guilt, Difficulty concentrating or making decisions, Psychomotor agitation or retardation, Suicidal thoughts | It is a widely utilised instrument designed to screen for and measure the severity of depression. It is based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) criteria for major depressive disorder. The scores for each item are summed to produce a total score ranging from 0 to 27. Higher scores indicate greater severity of depressive symptoms | It is straightforward, brief, and easy to understand, making it accessible to patients and practitioners alike; It is one of the most commonly used screening instruments for depression in primary care settings, mental health clinics, and research studies worldwide; It covers the full spectrum of depressive symptoms aligned with DSM criteria, offering a robust assessment of major depressive disorder; It is effective for both screening for depression and monitoring changes in symptoms over time, aiding in treatment planning and evaluation; The PHQ-9 has demonstrated high reliability and validity, including sensitivity and specificity in identifying depression | It is not a diagnostic instrument, a clinical interview is required to diagnose depression officially; It does not assess other mental health conditions or the complexities of mood disorders beyond major depression; It is subject to biases arising from personal perceptions, mood at the time of assessment, and social desirability, which can affect the accuracy of the results; The PHQ-9 focuses exclusively on depressive symptoms and does not assess other mental health conditions or comorbid issues, which may be relevant for a comprehensive mental health evaluation |

| CF-PedsQL-GI | Abdominal pain, Nausea, Constipation, Diarrhoea, Eating and feeding difficulties, Fecal incontinence, Nutritional concerns | It is a specific version of PedsQL, designed to assess gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and their impact on HRQoL in children with cystic fibrosis (CF) and other chronic health conditions that involve GI issues. It targets the unique challenges faced by CF patients, focusing on GI issues that are commonly experienced with the condition. Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with scores being transformed into a 0–100 scale. Higher scores represent better QoL | It addresses the unique GI challenges faced by children with cystic fibrosis, making it a relevant tool for assessing quality of life in this population; It captures a wide range of GI symptoms as well as their effects on overall quality of life, providing a multidimensional assessment; It has been validated for reliability and validity in children with CF and other GI disorders; It is simple and accessible for children and families, facilitating higher completion rates; It can be instrumental in clinical settings for monitoring symptoms, guiding treatment decisions, and assessing the impact of interventions on quality of life | It may not be applicable to other conditions or general pediatric GI issues, limiting its use in broader contexts; It responses may be influenced by individual perceptions and reporting biases, particularly in younger children who may struggle to articulate their symptoms; It may not capture all nuances or rare symptoms experienced by patients; Differences in how gastrointestinal symptoms are perceived and reported across cultures might limit its applicability in diverse populations; The reliability of the results could be influenced by the child’s familiarity with the questionnaire or the healthcare context in which it is administered |

| Neuro-QoL | Physical Functioning, Emotional Functioning, Cognitive Functioning, Social Participation, Fatigue, Sleep Disturbance, Pain, Motor Symptoms | It is a set of questionnaires developed to assess the quality of life and health-related functioning in individuals with neurological conditions. The scale is widely used in clinical practice and research to capture patient-reported outcomes related to neurological health. Scores are usually transformed to a standardised scale with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 in the general population, and higher scores indicate better HRQoL | It assesses various dimensions of HRQoL, making it a comprehensive tool for understanding the impact of neurological conditions; It has demonstrated good reliability and validity across diverse neurological populations; The availability of both adult and paediatric forms allows for appropriate assessment across different age groups and stages of neurological disorders; It is quick to administer and easy to interpret, making it practical for both clinical settings and research studies; Its design facilitates regular monitoring of HRQoL, making it valuable for treatment planning and outcome assessment in clinical practice | It may not capture all the nuances of specific diseases or rare neurological disorders without the use of additional specialised measures; Some domains may overlap with other QoL measures or symptom-specific scales, potentially leading to redundancy in assessments; For some patients with severe neurological conditions, the length of the questionnaire may be a burden, potentially impacting completion rates and response quality; The scales may require adaptation or validation in different cultural or healthcare settings to ensure their relevance and accuracy across diverse populations; The reliance on patients to recall experiences over a specific period may result in recall bias, especially in individuals with cognitive impairments |

| INQoL | Physical functioning, Fatigue, emotional well-being, social participation, Pain and Discomfort | It is a specialised tool designed to assess QoL in individuals with neuromuscular disorders (NMDs). It is tailored to capture the unique experiences and needs of patients with conditions such as muscular dystrophies, myopathies, and other NMDs. Scores are calculated for each domain and can be aggregated to provide a total quality of life score, with higher scores indicating better quality of life | The INQOL is specifically designed for neuromuscular disorders, making it highly relevant and sensitive to the unique challenges faced by patients with these conditions; It allows for a more personalised and accurate measurement of QoL in NMD patients; It addresses multiple dimensions of QoL, providing a holistic view of the patient’s well-being; The INQoL has been validated for reliability and validity in assessing QoL among individuals with NMDs; It can adapt to a wide range of symptoms and challenges faced by individuals; It can be beneficial for tracking changes in QoL over time, particularly in response to treatment or disease progression | It is highly specific to NMDs and may not be applicable or as effective for assessing QoL in other types of conditions or populations; Depending on the degree of individualisation, the scale may require more time and effort to administer and interpret compared to standard questionnaires; It may not be applicable or relevant to individuals with disabilities or conditions outside the neuromuscular spectrum; There may be overlap with other QoL measures or condition-specific scales, potentially leading to redundancy in assessments; The interpretation of QoL and the relevance of specific issues may vary across different cultural contexts, potentially affecting the validity of the results in non-Western populations |

| PBC-40 | Itch, symptoms, fatique, cognition, emotional well-being, social/family well-being | It is a specific patient-reported outcome measure designed for assessing QoL in patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), a chronic liver disease. The scale emphasises the subjective experience of patients, capturing how PBC affects their daily lives and overall well-being. Scores are calculated for each domain as well as a total score, generally where higher scores indicate a worse QoL | It is tailored specifically for individuals with PBC, capturing the unique aspects of this chronic liver disease that may not be addressed by generic QoL measures; It includes multiple domains that cover various aspects of QoL, providing a holistic view of how PBC affects patients; It has demonstrated good validity and reliability, making it a trustworthy tool for assessing quality of life in patients with PBC; The scale can be used to monitor treatment outcomes and disease progression; It is valuable in clinical research settings, aiding in the evaluation of new treatments and therapies specifically aimed at improving the QoL for individuals with PBC | It may not address quality of life aspects related to comorbidities or other overlapping conditions faced by patients; It may be time-consuming for some patients to complete, and the complexity of the scale may require careful explanation and administration; The interpretation of QoL and symptom relevance may vary across different cultures, raising questions about the scale’s applicability in diverse populations; Patients must accurately recall symptoms and quality of life over a specified time frame, which could lead to variability in responses, especially in those experiencing cognitive or memory issues |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | Functioning Scales, Symptom Scales, Global Quality of Life Scale | It is a widely used instrument designed to assess the HRQoL of cancer patients. It is part of a modular system that includes disease-specific questionnaires, allowing for comprehensive evaluation across various cancer types. Responses are rated on a Likert scale, with scores transformed to a 0–100 scale for each domain. Higher scores on functioning scales indicate better functioning, while higher scores on symptom scales indicate greater symptom severity | It covers various dimensions of HRQoL, providing a holistic view of the patient’s experience; The questionnaire has been extensively validated and demonstrates good reliability and validity across diverse cancer populations and treatment settings; It provides insights into how cancer and its treatment impact daily life and overall well-being; It can be supplemented with disease-specific modules that address particular cancer types or treatments, enhancing its utility in personalised patient care; The scale is valuable for assessing treatment outcomes, monitoring disease progression, and conducting research on cancer-related QoL | Its generic nature means it might not capture specific symptoms related to particular cancer types or therapies as effectively as disease-specific tools; There may be overlap with other QoL measures or cancer-specific questionnaires, which can lead to redundancy in assessments; The questionnaire may not fully account for the wide-ranging effects of comorbidities or treatments that might alter a cancer patient's HRQoL; Some patients, particularly those with advanced disease or cognitive impairments, may find it challenging to complete the questionnaire accurately; The responses may be influenced by the patient’s perceptions and reporting biases, which can affect the accuracy of the results |

| HAE-QoL | Physical Functioning, Emotional Well-being, Social Functioning, Symptoms and Treatment Impact | It is a specialised tool designed to assess the HRQoL of individuals living with hereditary angioedema (HAE), a rare genetic condition characterised by recurrent episodes of severe swelling (angioedema) that can affect various parts of the body. Scores are usually computed for each domain, with higher scores indicating better QoL and lower scores reflecting greater impairment | It is specifically designed for individuals with HAE, capturing unique symptoms and impacts of the condition that generic QoL instruments might miss; It covers multiple dimensions of QoL, including both physical and emotional aspects, providing a holistic view of the patient’s experience; It has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, including reliability and validity; It can be instrumental in clinical settings for assessing the effectiveness of treatments and monitoring changes in QoL over time; It is useful in clinical trials evaluating new therapies for HAE, allowing for an understanding of how treatments may improve patients' QoL | It may not be applicable for assessing QoL in patients with other conditions or types of angioedema; There may be overlap with other QoL measures or condition-specific scales, leading to redundancy in assessments; Depending on the number of items, some patients may find the questionnaire length to be a burden, particularly during acute episodes of angioedema or when experiencing significant discomfort; The interpretation of certain items and responses may vary across different cultural and healthcare settings, potentially affecting the scale's applicability in diverse populations; Responses may be influenced by individual perceptions and reporting biases, which can affect the accuracy of the results |

| SScQoL | Physical Functioning, Emotional Well-being, Social Functioning, Symptom severity and impact | It is a tool designed to assess HRQoL, specifically in patients with systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). This scale focuses on capturing the impact of SSc on various aspects of a patient's life. Scores are calculated for each domain and can be transformed for overall HRQoL assessment. Higher scores may indicate worse QoL, particularly if addressing negative aspects of the disease | It is tailored specifically for individuals with systemic sclerosis, ensuring a relevant assessment of symptoms, challenges, and their impacts on QoL; The SSc-QoL provides a holistic view of how systemic sclerosis affects patients in their daily lives; The scale has demonstrated strong reliability and validity, confirming its effectiveness in measuring QoL in patients with SSc; The scale provides meaningful insights into how SSc affects overall well-being and daily functioning; The scale is valuable for monitoring disease progression, evaluating treatment outcomes, and conducting research on systemic sclerosis-related quality of life | Tt may not be applicable for assessing QoL in patients with other types of scleroderma or different conditions; There may be overlap with other disease-specific or general quality of life measures, which can lead to redundancy in assessments; Depending on the number of items and domains covered, the scale may be time-consuming for some patients to complete, and its complexity may require careful administration to ensure accurate responses; Differences in cultural attitudes towards health and illness may affect how certain symptoms are interpreted and reported, potentially limiting the scale's applicability in diverse populations |

| kiddo-KINDL | Physical Well-Being, Emotional Well-Being, Self-Esteem, Family, Social integration, School functioning | It is an adaptation of the KINDL scale, which is used for assessing QoL in children with chronic conditions and is suitable for healthy children as well. Scores for each domain are usually transformed into a 0–100 scale, with higher scores indicating better quality of life. Domain scores are often averaged to produce an overall HRQoL score | It focuses on the child's perspective, capturing their experiences and perceptions of quality of life, which is crucial for effective assessments and interventions; It includes multiple domains that cover different aspects of a child's life, providing a holistic view of their well-being; the scale provides valuable insights into how health conditions and treatments affect children's daily lives and overall QoL; It can be used in clinical settings for assessing children with chronic conditions as well as in research contexts for studying HRQoL across different populations; The scale can be used across different settings and adapted for various age groups, making it versatile for clinical and research purposes | Children's responses may be influenced by their mood at the time of completion, social desirability, or their understanding of the questions, leading to potential biases; The interpretation of some items may vary across different cultural and healthcare contexts, potentially impacting the scale's applicability in diverse populations; Younger children or those with certain cognitive impairments may struggle to comprehend some items or respond accurately, which can affect the validity of their results; some children may find the questionnaire burdensome, potentially affecting motivation to complete it, particularly if they are feeling unwell; it may not capture the full spectrum of quality of life issues faced by children with specific chronic conditions compared to disease-specific scales |

| BD-QoL | Physical Functioning, Emotional Well-being, Social Functioning, Pain and Discomfort, Overall Impact | It is a specific instrument developed to assess the QoL of patients suffering from Behçet's disease, a rare and chronic autoimmune condition characterised by recurrent oral and genital ulcers, eye inflammation, and other systemic manifestations. Scores are aggregated to provide domain-specific and overall QoL scores. Higher scores typically indicate a better QoL | It is specifically designed for Behçet's disease, making it highly relevant for capturing the unique impacts of the disease on QoL; The scale provides insights into the patient's perspective, helping to understand the broader impact of the disease beyond clinical symptoms; The scale can be used in clinical practice for monitoring patients and evaluating treatment effectiveness, and in research settings to assess the impact of different therapies or interventions; It has been validated in studies with Behçet's disease patients, demonstrating good reliability and validity in assessing HRQoL for this condition | Its applicability may be limited for patients with other conditions or diseases with different symptom profiles; Its results can be influenced by individual perceptions, moods, or social desirability, which may lead to variability in responses; Some patients, particularly those experiencing cognitive difficulties due to the disease or its treatment, may struggle with understanding some items or responding accurately; Differences in cultural attitudes toward health and illness can affect the interpretation of questions and responses, which may impact the scale's applicability across diverse populations |

BD-QoL Behcet disease quality of life, CF Cystic fibrosis CF-PedsQL GI Cystic fibrosis paediatric quality of life inventory gastrointestinal symptom scales, EORTC QLQ-C30 European organisation for research and treatment for cancer quality of life questionnaire-30, EQ-5D-3L/5L Europe quality of life 3 dimension/5 dimension, FACIT Functional assessment of chronic illness therapy, HAE-QoL Hereditary angioedema quality of life, HADS Hospital anxiety and depression scale, HAQ Health assessment questionnaire, HAQ-DI Health assessment questionnaire disability index, INQoL Individualised neuromuscular quality of life, MG-QoL-15r Myasthenia gravis quality of life 15-items revised version, Neuro-QoL Quality of life in neurological disorders, PBC-40 Primary billiary cholangitis-40 items, PedsQL Paediatric quality of life inventory, PHQ-9 Patient health questionnaire-9, SF-12 Short form health survey 12 items, SF-36 Short form health survey 36 items, SSc-QoL Systemic sclerosis quality of life, WPAI Work productivity and activity impairment

Analysis of overall health improvement in various RD patients

Analyses of overall health improvement in multiple patients with rare diseases (RDs) have yielded varied results. Most of the included studies have reported an improvement in the QoL after intervention [3, 4, 11–14, 25, 29, 31, 32, 36, 37]. However, one study indicated no discernible change in patients' QoL following treatment compared to baseline parameters [27], and seven studies reported no significant improvement [18, 19, 26, 28, 30, 33, 35].

The disparity in QoL improvement is partly attributed to the use of different scales to measure QoL after intervention, as well as the specific disease being studied, the extent of the research, and the use of generic versus disease-specific scales (Supplementary File 3). For example, in patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc), two studies used the health assessment questionnaire-disability index (HAQ-DI) to evaluate QoL after intervention [20, 28], while Heřmánková et al. utilised the health assessment questionnaire (HAQ), SF-36, and Beck’s depression inventory-2 (BDI-2) to assess HRQoL [17]. Similarly, in patients with myasthenia gravis (MG), one study used both generic scales (EQ-5D, VAS, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment [WPAI]) and a disease-specific scale (MG-QoL-15r) to evaluate patients' QoL [14], while one study solely used the disease-specific scale to evaluate patients' QoL [13].

Those reporting improvement after treatment also exhibited variability in the degree of improvement based on the scale used to assess HRQoL (Fig. 3). This variability was influenced by several factors, including the specific HRQoL instruments utilised, the nature of the rare disease, and the demographics of the patient populations studied. For instance, research employing disease-specific scales often yielded more nuanced and contextually relevant outcomes than those relying on generic scales [11, 25].

Disease-specific tools, such as the MG-QoL15r for myasthenia gravis and the Behcet disease quality of life (BDQoL) scale for patients with Behcet disease, effectively address the unique challenges faced by individuals with these specific conditions [13, 42]. These scales can accurately capture changes in patient experiences that generic instruments might overlook, thus providing a more comprehensive clinical picture. In contrast, while useful for broad comparisons, generic scales such as EQ-5D and PedsQoL often reveal only moderate improvements or fail to identify significant changes in QoL [18, 39]. This limitation is particularly evident in patients experiencing complex and multifaceted symptoms. The heterogeneity in disease characteristics significantly influenced the variability in QoL reporting. For example, conditions with a predominant psychological component, such as systemic sclerosis, often exhibited minimal changes in QoL when assessed using generic instruments [17, 20]. In contrast, research focusing on diseases that primarily affect physical health showed more pronounced improvements in QoL following treatment [11, 13].

The EQ-5D scale is widely used to evaluate the quality of life in patients with rare diseases. One study noted a substantial enhancement in QoL following treatment, reflected in increased scores across all EQ-5D domains and improvements in depression, anxiety, and work productivity loss. Notably, patients receiving higher medication doses experienced the most significant improvements in their QoL [12]. Another study reported a discernible improvement in participants' quality of life across all EQ-5D domains, which aligned with the disease-specific scale [14]. High health utility scores post-treatment were indicative of pronounced improvement [44, 49]. Some studies included in this review illustrated moderate improvements in quality of life using the EQ-5D scale in conjunction with other measurement scales [29, 39]. However, different outcomes were reported when evaluating the impact of interventions on patients' quality of life. Cleary et al. reported a decrease in self-care and mobility subdomain scores after treatment follow-up, while utility scores remained stable, suggesting mild improvement[16]. Additionally, several studies indicated significant improvements in the EQ-5D VAS scale after intervention [8, 14, 42, 49], moderate improvement [20, 37], and mild improvement following treatment [29], as well as no change or minimal improvement after treatment [15].

The SF-36 scale is utilised to assess the impact of rare diseases on patients' QoL. Most of the included studies have indicated the effectiveness of this scale in quantifying the impact of rare diseases on patients' QoL, with many demonstrating significant enhancements across all SF-36 domains [37, 41, 45]. Some studies have shown improvements in specific domains, such as physical function, role function, bodily pain, social function, and the Physical Component Summary (PCS) following interventions [25]. Another study reported significant improvement in the PCS subdomain and other measurement scales [17]. Nonetheless, some studies have reported a decline in HRQoL following treatment [39]. Furthermore, there were differing outcomes when comparing surgical and nonsurgical interventions [40]. Similar to the SF-36 scale, the simplified SF-12 scale is also utilised to assess the impact on the quality of life in patients with rare diseases. All SF-12 domains demonstrated improvement after intervention [43]. Following treatment, there was moderate improvement in the PCS subdomain [29] and higher Mental Component Summary (MCS) scores, while no significant difference in PCS scores was observed, indicating mild improvement in patients’ quality of life [3].