Abstract

Aims

Health care transition (HCT) to adult care and young adult disease self-management is a multi-step process involving three major stakeholders – the adolescent, the caregiver, and the provider. Preparation gaps exist within each of these stakeholder groups. This paper presents the development of the Intervention to Promote Autonomy and Competence in Transition-aged Youth (IPACT), a multi-level (adolescent, caregiver, provider), multi-modal (interactive skill building sessions, educational materials, videos) intervention to address gaps in all three stakeholder groups simultaneously and help support achieving the three core elements of HCT planning.

Methods

Eight processes were utilized to develop the IPACT intervention, including reliance on existing literature and materials, stakeholder feedback at multiple points during development, and regular support and guidance from service liaisons within each of four tertiary-care clinics targeted for this intervention within a large, urban children’s hospital.

Conclusions

IPACT includes the conceptual schema, logic model, intervention curriculum components, and implementation timeline. IPACT could be used by programs to simultaneously address gaps in stakeholder HCT planning knowledge and skills.

Keywords: Intervention development, Adolescent and Young Adults with Special Health Care Needs, Caregivers, Pediatric providers, Healthcare Self-management

Highlights

-

•

HCT planning should include three stakeholders: caregiver, adolescent, provider.

-

•

HCT is a planned process that requires specific intervention.

-

•

A multi-level, multi-modal HCT intervention was developed.

-

•

This HCT intervention addresses three core elements of transition planning.

1. Introduction: the case for a multi-level, multi-modal intervention

Over the past three decades, therapies for pediatric onset illnesses have improved to the extent that 90 % of children with child-onset illness will survive into adulthood.1 There were an estimated 7.3 million 12–17 year-olds in the U.S. as of 2020 with a special health care need. 2 Assuming that individuals in this group are evenly distributed by age, approximately one million 18 year-olds with special health care needs could transition into the adult care system annually. 2 The transition process appears to be successful for most adolescents and young adults with special health care needs (AYASHCN) if their conditions are mild.3 As the complexity of the condition increases, so does the resultant morbidity and mortality if transition planning is not successful.4, 5

The Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) has defined successful transition planning (the MCHB core transition outcome) 2, 6 as consisting of three core elements: 1) the adolescent patient meeting with the provider alone; 2) the provider actively working with this youth to make positive choices about their health, gain skills to manage their health and health care, or understand the changes in health care that happen at age 18; and 3) the provider discussing the eventual shift to an adult care provider. 7 Although the core elements primarily set expectations for patients and providers, caregivers play a fundamental role through their acceptance of or resistance to their adolescent meeting with the provider alone. Thus, AYASHCN, their caregivers, and their pediatric health care providers must all have the requisite knowledge and skills to help prepare for successful transition to adult-based care. It should be noted that MCHB does not address all issues of the broader transition planning outcomes, which also include aspects such as provider availability, insurance limitations, and other psychosocial barriers.

Only 22.5 % of AYASHCN in the 2022 MCHB-sponsored National Survey of Children’s Health were achieving the core transition outcome. While data from this survey should be interpreted given variations in measurement strategy over time,6 this low percentage is worrisome and may be even lower for youth and families from diverse cultures. AYASHCN from households with a primary language other than English face added barriers to transition services. 2, 8 The objective of this paper is to describe the development of a multi-level, multi-modal, dual-language intervention involving three key stakeholders – AYASHCN, caregivers, and providers – in order to facilitate meeting the three core elements of transition planning.

1.1. Alignment with theory and science

Self Determination Theory (SDT) posits that internal motivation and thus behavior is driven by three psychological needs: competence (i.e., skills, confidence), autonomy (i.e., control, choice), and relatedness (i.e., connection with supportive others).9 SDT has substantial support from studies of long-term behavior change.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 For example, perceived competence and physician support for autonomy (e.g., relatedness) were positively associated with health care transition (HCT) readiness among AYASHCN. Specifically, AYASHCN responded well to physicians who provided positive reinforcement for problem-solving and adopted a collaborative approach.15 Those findings support the training of health care providers, in addition to AYASHCN and caregivers, to promote the adoption and facilitation of strategies for HCT preparation for AYASHCN and their families (with a focus on the primary caregiver). Cognitive science research supports the use of variation and spaced practice to improve information retention and knowledge development, suggesting the value of engaging AYASHCN through multiple formats spaced out over time.16 Intervention strategies aligned with health behavior counseling are also the basis for techniques such as Motivational Interviewing,17 which offers a proven set of interpersonal communication strategies for promoting behavior change.

1.2. AYASHCN preparation gaps

The MCHB has established HCT preparation as a national performance measure,18 and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), American Academy of Family Practice (AAFP), and American College of Physicians (ACP) recommend HCT preparation as part of routine care for all adolescents and young adults.19 Meeting alone with the provider is endorsed by the AAP, AAFP, and ACP,19 and increasing the proportion of adolescents speaking privately with a provider is an objective of Healthy People 2030.20 Only 54 % of AYASHCN reported having time alone with their health care provider at their last preventive care visit.8 Only 30 % of 17 year-olds with special health care needs reported meeting with providers alone, 41 % for those 18 or older.21

The MCHB core transition outcome also includes understanding changes in health care that occur at age of majority, typically 18 years of age, a focus of the AAP guidance as well.22 There is evidence that AYASHCN prefer knowing about differences between child- and adult-centered care prior to transition.23 Yet absent targeted education, AYASHCN and caregivers are unprepared to navigate shifts, such as transfer of responsibility for informed consent and medical decision-making and changes in access to medical records.

The Society of Adolescent Health and Medicine has endorsed using technology such as electronic health records (EHR) to strengthen the transition continuum of care and to ensure “the organization and transmission of high-quality information between the health care team and patients and families as well as between providers.”24 Among the major barriers to transition to the adult care system reported by internists are: 1) difficulty in obtaining pediatric records and 2) AYASHCN lack of preparation (ability) in accurately reporting their health history.25 AYASHCN unable to report their health history to their adult provider risk inaccuracies with implications for reduced quality of care.26 Hence, it is essential to equip AYASHCN to navigate EHRs and take advantage of available functionalities for sharing their health information.

There are health disparities in HCT planning for AYASHCN. Those who do not speak English have 2.5 times the odds of not achieving HCT preparation relative to English speakers. Individuals from minority populations are less likely than non-minorities to trust their providers.27 During pediatric interviews, providers are less likely to direct questions about routine childhood illnesses to Black and Hispanic youth compared to White youth.28 Reading comprehension and an understanding of mathematical properties (e.g. treatment A is 60 % effective and treatment B is 48 % effective) are vitally important to the health care informed consent process. Only 37 % of United States high school seniors are ranked as proficient in reading and 25 % in math.1 These deficiencies constitute health illiteracy and have significant implications for interventions designed to improve autonomous health care self-management.

1.3. Caregiver preparation gaps

AYASHCN preparation for and success in HCT is influenced by the openness for transition of supportive others in their life, such as parents or caregivers. Caregivers who are able to monitor, be a resource, collaborate, and maintain ongoing dialogue are crucial to AYASHCN successfully transitioning to autonomous self-management. Yet many caregivers struggle with ceding control and nurturing autonomy in AYASHCN.29 Forty-eight percent of caregivers reported difficulty with letting go of management responsibilities of their youth’s medical condition.30

Locally, the genesis for a transition intervention to address these AYASHCN/caregiver knowledge gaps came from conversations with members of a hospital-based Caregiver Advisory Board who voiced concerns over not being prepared for abrupt changes when their AYASHCN turned 18 years of age. Specifically, caregivers reported feeling unprepared to lose access to their AYASHCN’s electronic patient portal and to help their AYASHCN understand the concept of signing a consent for medical care. AYASHCN Advisory Board members voiced similar concerns about these perceived abrupt changes. While it is recommended that transition planning begin in early adolescence, it is critical that 17–18 year olds be prepared for changes at age 18 when they assume control of health care decisions.

1.4. Pediatric provider preparation gaps

Pediatric providers need better preparation to facilitate HCT.31 AYASHCN have identified informational and skill-based needs that require provider support, including assistance with logistics and individualized management of their HCT process.26 Consistent with SDT Theory, previous work has shown that provider support for autonomy is one of the two best predictors of transition readiness, the other being patient competence.15 Yet many pediatric providers are ill-prepared to partner with AYASHCN or their families to plan or implement HCT.1, 32 Along with knowledge, pediatric providers need confidence in conveying HCT developmental tasks, such as inviting the caregiver out of the room and managing AYASHCN and caregiver responses to this invitation including surprise, uncertainty, and disagreement.

1.5. Evidence-based intervention gaps

Despite strong evidence that AYASHCN need preparation for HCT to the adult care system and agreement on the elements in planning that transition, evidence-based interventions to facilitate preparation of AYASHCN for successful HCT are lacking.7, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 Few HCT intervention studies have employed an experimental design38 or used a comparison group.39 There is a lack of rigorous research as to which methods improve the specific steps in HCT planning. No study has used a multi-level intervention targeting the three stakeholder groups that play critical roles in HCT preparation: AYASHCN, caregivers, and pediatric providers.

This paper describes the process of developing a HCT intervention for 17–18 year old AYASHCN, their caregivers and pediatric providers to address their knowledge and skill gaps simultaneously. Two prongs of the intervention, one targeted toward knowledge and process for AYASHCN/caregivers and a second prong targeted to pediatric providers will allow the intervention to meet the needs of all stakeholders. The stages of intervention development will be described, the components of the intervention will be presented with data provided from stakeholder feedback in the iterative process.

2. Methods

The research team used an iterative approach to generating content, structure, and the delivery format. Content generation and refinement were facilitated by weekly meetings of the multidisciplinary research team during which editing of intervention materials occurred. Intervention development included the following processes: 1) input from pediatric provider liaisons (“service liaisons”); 2) literature review; 3) existing patient educational material review; 4) development of a logic model; 5) development of specific intervention components; 6) input from AYASHCN and caregivers; 7) training for facilitators; and 8) practice and pilot testing with AYASHCN and caregivers. Human subjects were not recruited to participate in the intervention development phase of this funded project.

3. Results

The results section will report on the eight processes used in curriculum development, present the developed curriculum, and integrate data from feedback of key stakeholders.

3.1. Service liaison identification and input

The intervention was targeted to and developed in collaboration with four clinical services; Gastroenterology, Renal, Rheumatology, and Neurology. A liaison from each service was chosen based on previous effective collaboration work with the research team. The research team met every other week with the liaisons to discuss all phases of the intervention planning to ensure the intervention fit their patient needs and clinic work flow. The liaisons (three physicians and a psychologist) were project collaborators with 5 % salary support.

3.2. Literature review

Literature searches in PubMed and PsycInfo used the search terms: health care transition education or readiness, chronic illness, adolescence, and provider intervention. This review also included searching updated citations for SDT related to health care outcomes. The research team reviewed current U.S. governmental and professional society HCT guidance (e.g., Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine, AAP, AAFP, ACP). The research team synthesized findings that identified gaps in meeting the MCHB core transition outcome, including results from prior empirical studies by the research team.21, 40

The team decided to use a conceptual schema combining SDT constructs with a social-ecological approach (Fig. 1). Selected components of the social-ecological approach supplemented the SDT framework.24 This perspective directs attention to the impact of patient characteristics (e.g., knowledge and attitudes), patient social environment (e.g., support from family), and the health care environment (e.g., clinic culture, patient-provider relationships, institutional processes such as those related to informed consent and the EHR, access to adult care providers) on the HCT process.25

Fig. 1.

Project IPACT Model.

3.3. Patient educational material review

HCT educational material was collected for potential inclusion in the intervention. Specifically, educational materials available from the EHR (Epic) used by the research team were reviewed for topics that addressed patient portal EHR access and function. Service liaisons provided condition-specific education materials.

3.4. Development of logic model

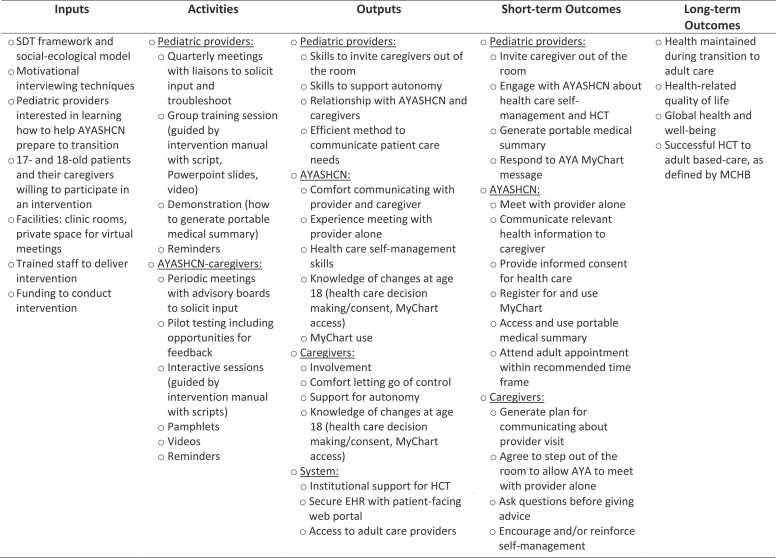

The processes outlined in 3.1, 3.2, 3.3 were utilized as data to create a structured logic model41 (Fig. 2). In the health sphere, logic models typically include inputs (prerequisites for program launch), activities (intervention components), outputs (factors that are targeted by the intervention in order to change or reinforce desired behaviors), short-term outcomes (the specific behaviors the program is designed to change or reinforce, which are often the focus of evaluations to determine program success), and long-term outcomes (the ultimate health outcomes sought).

Fig. 2.

Logic model for multi-level, multi-modal intervention to promote autonomy and competence in transition-age AYASHCN (IPACT).

Inputs of this study’s logic model (Fig. 2) include circumstances and resources outside of the intervention implementation that are necessary for success, such as theoretical framework, logistical considerations with funding source, and availability of willing providers, caregivers, and AYASHCN. Activities include feedback-informed, separate interventions for pediatric providers and AYASHCN-caregiver dyads. Outputs and short-term outcomes are separated with respect to pediatric providers, AYAHCSN, caregivers, and system-level considerations. Short-term outcomes are related to intervention-promoted behaviors (e.g., provider and AYASHCN meeting alone, increased communication between caregiver-AYASHCN dyad and provider/AYASHCN dyad) and longer-term behaviors (e.g., attendance at adult-care appointment). Long-term outcomes are broader hypothesized outcomes projected to improve as a result of the intervention, including maintenance of health and related quality of life.

3.5. Development of specific intervention components and intervention map

Building on the research team’s experience with the development of HCT interventions42, 43 and the findings from the literature and educational materials review, the research team and liaisons concluded that the optimal intervention would be multi-modal. Accordingly, the research team developed curriculum components in three complimentary formats: 1) interactive skill building sessions (facilitated discussion or presentation with discussion); 2) videos; and 3) informational pamphlets. The resulting intervention was named the Intervention to Promote Autonomy and Competence in Transition-age Youth (IPACT).

3.5.1. IPACT intervention development for AYASHCN/caregiver

The team decided the intervention would target the AYASHCN and caregiver together to allow for mutual learning and support in a discussion-based format. A facilitator manual for interactive skill building sessions was created first, followed by scripts for the accompanying videos and then the pamphlets provided for each session. The video scripts and pamphlets were developed by the research team and the facilitator manual was developed by one research team member. Four team members of different disciplines (e.g., medicine, psychology, law, and a research coordinator who was a young adult with lived experience), plus the service liaisons, independently reviewed these materials and suggested edits. The final edits were made in team meetings after reaching consensus. Video scripts were reviewed with a video production company, which was contracted to refine the messaging, shoot the videos, and edit/format the final video products. To provide access to AYASHCN whose family identify as preferring communication in Spanish, video scripts and pamphlets were translated using a professional translation service, subtitles were added to videos, and a facilitator who speaks Spanish approved the interactive skill building session content.

3.5.2. IPACT intervention map for AYASHCN/caregiver

The AYASHCN-caregiver portion of IPACT includes three interactive skill building sessions, spaced approximately every six months starting around an AYASHCN’s age of 17 years. The first two sessions are implemented prior to the AYASHCN’s 18th birthday; the third session is implemented after the AYASHCN’s 18th birthday. Sessions are 45 min in length. Following the first and second interactive skill building sessions, AYASHCN and caregivers are provided with a video to watch and a pamphlet to review prior to the next session. Fig. 3 represents the timing and components of the full IPACT intervention.

Fig. 3.

IPACT Intervention Map.

Each of the three AYASHCN-caregiver sessions focuses on one major HCT skill. Session 1 focuses on communication strategies in two situations: meeting alone with a provider and relaying information from time alone with the provider to the caregiver. Session 2 focuses on the significance of consenting for services and understanding the legal implications of turning 18 years old on health care delivery. Session 3 focuses on the rationale and specific skills for navigating the EHR patient portal (Epic’s MyChart). Content for each finalized component of AYASHCN-caregiver intervention is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

AYASHCN and caregiver intervention curriculum outline.

| AYA age | Major Objectives/Activities |

|---|---|

| 17 y/o |

Interactive Session 1: Communication strategies and meeting alone with a provider

|

| 17.5 y/o |

Interactive Session 2: Consent for treatment process and legal implications when turning 18

|

| 18 y/o |

Interactive Session 3: Utilizing patient portal of EHR: Rationale and Skills

Pamphlet emphasizes process of sharing one’s medical record with important others, skills for using MyChart to communicate with providers, summaries of Test Results, Health Summary, and Medications tabs in MyChart, utilizing the pre-check in feature, an affirming statement highlighting completion of IPACT program. |

3.5.3. IPACT intervention development for pediatric providers

Concurrently, the interactive skill building sessions for pediatric providers were created by an identified medicine lead. The same process for review and edits, as described in 3.5.1, was completed by the research team/liaisons and an accompanying video script was created, reviewed, and filmed to support the provider presentation. No pamphlet was created for pediatric providers.

3.5.4. IPACT intervention map for pediatric providers

This portion of IPACT includes two, 1-hour interactive didactic sessions on HCT planning followed by provider-initiated problem solving led by a medicine faculty research team member as well as one accompanying video. This training intervention is intended to be conducted in a group format. The first provider interactive skill building session discusses the AYASHCN meeting with the provider alone, promoting and supporting the patient’s self-management, and discussing eventually seeing an adult provider. The providers watch the instructional video, modeling two scenarios: 1) the caregiver willingly leaving the room; and 2) the caregiver being reluctant to leave the room, and how the provider handled each scenario. The video then models a provider interviewing an AYASHCN about self-management and how to navigate the likelihood of drinking alcohol and if that might impact their chronic condition. This video presentation is followed by active problem solving for barriers or clinical situations which may make inviting a caregiver out of the room challenging. Session 2, implemented 3–4 months after the first session, demonstrates how to access and generate the portable medical summary within the EHR, followed by the provider teaching back how to access and generate the portable medical summary. Content for the interactive skill building sessions and video are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Provider Intervention Curriculum Outline.

| Timeframe | Major Objectives/Activities |

|---|---|

| Interactive Session 1 |

|

| Interactive Session 2 |

|

3.6. AYASHCN and caregiver input

As the intervention was developed, the research team repeatedly solicited and incorporated feedback on all intervention components (e.g., clarity and acceptability in wording, interactive skill building session examples, use of visuals during interactive skill building session) from separate AYASHCN and caregiver Hospital Advisory Boards along with other AYASHCN and caregivers receiving care at the research team’s institution. Caregiver and AYASHCN reviewed each modality (e.g., watched the video, experienced the script, read the pamphlet). The research team created open ended questions to inquire about content detail and relevance, presentation of content, and readability. As a specific example, the advisory boards were asked to review specific situations presented in the materials and offer additional details to increase relevance to youth and families. Each advisor was compensated $25 per hour. Combined results of stakeholder feedback are presented in Section 3.8.

3.7. Facilitator training

Research team members were facilitators of the patient and caregiver interactive skill building sessions. They were trained to lead each session using patient-centered and health behavior change strategies (e.g., Motivational Interviewing) by one of the authors.17 Facilitators used agreed-upon facilitator notes and clinical examples in the manual to ensure standardization of material presented.

With respect to the process/delivery of the interactive skill building session, specific language was discussed, practiced, and formally written into the facilitator manual to provide facilitators with a conversation process for supporting motivation on behavior changes presented in the interactive skill building sessions. Examples of behavioral changes included both immediate tasks (e.g., watching the accompanying video or reading the pamphlet before the next interactive skill building session) and integration of health behaviors to carry forward related to the intervention content (e.g., the AYASHCN asking the provider a question at the next clinic appointment, sending a message to the provider in the EHR patient portal). Aligned with SDT and with health behavior counseling strategies (e.g., Motivational Interviewing),17 the intervention included asking AYASHCN and their caregiver about their motivations for joining the study and for attending the sessions, personal goals for transition, and accomplishments in the process of HCT. These questions were coupled with reflective listening skills, especially with a focus on change talk to: 1) increase engagement from families; 2) model and affirm listening and communicating skills for families and AYASHCN; while also 3) personalizing intervention.

3.8. Practice and pilot testing

Practice administrations of the IPACT interactive skill building sessions were first conducted with research team members. Then, the IPACT components targeting AYASHCN/caregivers were pilot tested with 1–2 sets of AYASHCN-caregiver dyads per component (e.g., interactive skill building sessions, videos, pamphlets), with a total of nine AYASHCN and seven caregivers providing feedback. The provider training session was again practiced within the research team and edited by the research team.

3.8.1. Stakeholder feedback for the provider intervention

Service liaisons reviewed the interactive skill building session content and video scripts. They were supportive of the intervention and affirmed that the plan for the pediatric provider interactive skill building sessions was focused on inviting the caregiver out of the room. Example feedback for the perceived utility of the content on inviting the caregiver out of the room included describing this process as in the patient’s best interest. Positive feedback was focused on the instruction and modeling of how to invite the caregiver out of the room. Service liaisons reviewed the AYASHCN-caregiver video script to ensure it was congruent with the types of interactions they had with their patients. Scenes from the AYASHCN-caregiver video script were then used in the provider intervention video script.

Identified improvements reported by the service liaisons are described in Table 3. As an example of the video script review, service liaisons made wording suggestions aligned with SDT framework for maximizing AYASHCN engagement. The example below highlights changes from before and after review in a provider’s response to a patient’s question about interactions between medications and alcohol:

Table 3.

Service liaison feedback for provider intervention components.

| Component | Content valued | Delivery details (preferences/advice) |

|---|---|---|

| Interactive sessions and videos |

|

|

Before.

Health care provider: That’s a great question. While there’s not any direct interaction with your medications, I would encourage you to think about the other negative effects of drinking, like getting in trouble if you get caught drinking underage, or not being in control and making poor decisions.

After.

Health care provider: That’s a great question. There’s no known interaction with your medications. Drinking alcohol is part of college life and you may choose that it is not part of your lifestyle. However, have you thought about who you could talk to about this and how you’ll handle it?

3.8.2. Stakeholder feedback for the AYASHCN/caregiver intervention

Feedback provided by AYASHCN and caregivers during advisory board meetings and during pilot testing was evaluated across each mode (video, pamphlet, session manual). Comments were organized with respect for the stakeholders’ perceived value of the content/positives of the intervention and the perceived improvements/suggestions for both content and delivery. See Table 4. The research team incorporated this feedback into the final versions of the interactive skill building session facilitator manual and pamphlets.

Table 4.

AYASHCN-caregiver feedback on IPACT intervention.

| Component | Content valued | Delivery details (preferences/advice) |

|---|---|---|

| Interactive sessions |

|

|

| Pamphlets |

|

|

| Videos |

|

|

4. Discussion

This paper describes the development of a multi-level (AYASHCN/caregiver, provider), multi-modal (interactive skill building sessions, videos, pamphlets), bilingual (Spanish, English) intervention designed to increase a set of specific self-management strategies universal to a majority of AYASHCN transitioning to adult-based care. Specific self-management strategies include AYASHCN meeting alone and engaging in health care dialogue with a provider; caregivers and providers fostering this time alone with acceptance and reinforcement; AYASHCN communicating with caregivers about health-related changes; and AYASHCN and caregivers knowing and increasing comfort with changes in consent, release of information, and communication via EHR that occur after an AYASHCN turns 18. Unique to this intervention model are the multi-modal intervention strategies (e.g., interactive skill building sessions, written materials, video presentation) that are provided to all key individuals responsible for helping to support an AYASHCN (e.g., AYASHCN, caregiver, provider). The creation of complementary interventions designed for all three key stakeholders allows for targeted and focused practice of specific skills and recognizes each stakeholder’s role in teaching and reinforcing these behavioral and knowledge changes.

This intervention and the process of its development recognizes that self-management is a cornerstone of successful HCT preparation and requires knowledge and skill acquisition by all three stakeholder groups (AYASHCN, caregiver, provider) in that preparation. The intervention model is founded on well-established SDT and social-ecological constructs and provides a logic model wherein AYASHCN, caregiver and provider knowledge and skill gaps are addressed simultaneously using patient-centered processes of communication. Stakeholders informed the development of the intervention and affirmed the resulting curriculum's content and process. The AYASHCN/caregiver components of IPACT have been translated into Spanish. This represents the first multi-modal, multi-level, dual language intervention to improve HCT and meet the three key elements of the MCHB core transition outcome.

Specifically, this intervention brought together four specialties in pediatric care to create an intervention functional for each specialty. While this team recognizes that there are specific disease components that are unique to a patient’s self-management success, the components of this stakeholder-approved intervention represent a generalizable practice model of specific self-management skills necessary for a large majority, if not all, AYASHCN during their transition to adult-based care. In addition, this intervention would attend to self-management skills appropriate for an adolescent without a current chronic illness. While not inclusive of all necessary self-management skills, the skills provided in this intervention go beyond that of knowledge to include both skills-based practice as well as each family creating and practicing their own communication strategies for health care. The communication strategies discussed with AYASHCN in this intervention could generalize to many types of young adult conversations. The creation of this model that focuses on a subset of universal skills related to adult health care transition allows for a potentially cost-effective and hospital-wide application.

The implications for clinical care in pediatric settings are significant in that if found to be effective, the curriculum has the potential to impact AYASHCN, caregiver and provider roles at the level of the clinic visit. In doing so, it could provide all three sets of stakeholders a path forward in the inevitable transition to adult-based care, representing a culture shift in pediatric practice. Few HCT intervention studies have employed an experimental design38 or used a comparison group.39 There is a lack of rigorous research as to which methods improve the specific steps in health care transition planning. A next step is to conduct a rigorous evaluation of the IPACT intervention to evaluate its feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy and collect additional stakeholder feedback toward further improvements. Using a quasi-experimental design, 17-year-old adolescents and their caregivers from four clinical services, and their providers, will be recruited to participate in the IPACT intervention. A group of 18-year-old patients seen by these same providers a year earlier will serve as historical controls. Potential AYASHCN measures include knowledge of changes in medical decision-making at age 18, perceived competence in managing health care, and the SDT constructs of health care autonomy, parent/caregiver and provider support for health care autonomy,15 self-efficacy to meet with the provider alone, and perceived importance of meeting with the provider alone. Likely provider measures include: percent of visits wherein AYASHCN meet with the provider alone, changes in perceived importance of engaging in autonomy supportive behaviors, and perceived engagement in autonomy supportive behaviors.40, 44

4.1. Limitations

Content of the intervention demonstrated applicability and garnered positive feedback from AYASHCN, caregivers, and service liaisons. While this demonstrated an important generalizability across services treating different chronic conditions, the intervention was tailored for the specific institution. Edits based on institution-specific standards (e.g., adolescent patient portal access, specific consent forms and processes, and specific EHR utilized) would need to be made to tailor the intervention to successful HCT transition from a different institution. Further, the intervention content did not address the changing nature of insurance coverage during this period of transition as well as the impact of changing employment status on insurance. This could be a significant barrier to accessing health care, self-management of chronic illness, and of learning and implementing the strategies of self-management for transition to adulthood. Just as the content may need to be adjusted for institutional processes as noted above, further adaptation of this intervention in other settings may need to add examples for navigating specific insurance-specific barriers known to that population. Last, during intervention development, the process did not use a librarian for the literature review.

The framework and intervention described above have the potential to improve health care transitions across a variety of conditions and settings. However, rigorous evaluation will be necessary to demonstrate that potential. In addition, interventions for subpopulations of AYASHCN with distinctive features impacting cognition and communication, such as AYASHCN with intellectual disabilities or some autism spectrum disorders, will need to be tailored to the particular capacities and needs of those subpopulations.45, 46 Last, the socio-ecological model includes additional, important constructs, such as the influence of peers or extended family members or the larger cultural context in which families are embedded which were not the focus of this project.

5. Conclusions

The work described in this manuscript represents a testable multi-level intervention for AYASHCN/caregivers and pediatric providers to assist with three HCT behaviors associated with healthy transition outcomes. These three behaviors include communication strategies between all three stakeholders (e.g., provider inviting a caregiver out of the room, AYASHCN sharing health information with family, caregiver allowing space for AYASHCN communication with provider while also modeling important behaviors, such as informed consent, AYASHCN practicing communication in person and electronically regarding health). This intervention offers a multi-modal approach that combines in person/virtual sessions, videos, written information, with material available in both English and Spanish. This intervention addresses the recognized gaps in all three stakeholder groups that must be filled simultaneously in order for HCT to have a chance to succeed and the resultant quality of life and health status achieved.

Funding sources

This project is supported in part by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant # R40MC35363 (ACH), An Intervention to Promote Autonomy and Competence in Transition-Aged Youth (IPACT); and grant #T71 MC45698 the Leadership Education in Adolescent Health (ACH). The information or content and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government.

Ethical statement

Human subjects were not recruited to participate in the intervention development phase of this funded project.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hergenroeder C. Albert: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Babla Jordyn: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Investigation, Data curation. Blanca Sanchez-Fournier: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Investigation, Data curation. Constance M. Wiemann: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Mary Majumber: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Beth H. Garland: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors did not use any Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Funding from Global Health Therapeutics to pilot an adaptation of this intervention in adolescents with sickle cell diagnosis.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of the adolescents, young adults, caregivers, and service liaisons who provided feedback on the development of the IPACT intervention.

Data sharing statement

De-identified individual participant data will not be made available.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine. A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2002;110(6 Pt 2):1304–1306. Published 2002/11/29. Accessed Dec.

- 2.Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (2023). “2022 National Survey of Children’s Health: Guide to Topics and Questions”. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB). Retrieved [03/28/24] from [〈www.childhealthdata.org〉].

- 3.Bloom S.R., Kuhlthau K., Van Cleave J., Knapp A.A., Newacheck P., Perrin J.M. Health care transition for youth with special health care needs. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(3):213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Annunziato R.A., Parkar S., Dugan C.A., et al. Brief report: deficits in health care management skills among adolescent and young adult liver transplant recipients transitioning to adult care settings. J Pedia Psychol. 2011;36(2):155–159. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly A.M., Kratz B., Bielski M., Rinehart P.M. Implementing transitions for youth with complex chronic conditions using the medical home model. Pediatrics. 2002;110(6 Pt 2):1322–1327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheak-Zamora N., Betz C., Mandy T. Measuring health care transition: across time and into the future. J Pedia Nurs. 2022;64:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2022.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lebrun-Harris L.A., McManus M.A., Ilango S.M., et al. Transition planning among US youth with and without special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2018;142(4) doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. 2020–2021 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) data query. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB). Retrieved 9/12/2023 from [〈www.childhealthdata.org〉].

- 9.Ryan R.M., Deci E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deci E.L., Ryan R.M. Self-determination theory in health care and its relations to motivational interviewing: a few comments. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deci E.L.R.R. Plenum; New York: 1985. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edmunds, Ntoumanis N., Duda J., Edmunds J., Ntoumanis N., Duda J.L. In: Self-determination in exercise and sport. Hagger M., Chatzisarantis N.L.D., editors. Human Kinetics; Champaign, IL: 2007. Perceived autonomy support and psychological need satisfaction as key psychological constructs in the exercise domain; pp. 35–51. In:2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryan R.M., Deci E.L. Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic dialectical perspective. Handb self-Determ Res. 2002;2:3–33. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson D.K., Griffin S., Saunders R.P., et al. Formative evaluation of a motivational intervention for increasing physical activity in underserved youth. Eval Program Plann. 2006;29(3):260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stephens S.B., Raphael J.L., Zimmerman C.T., et al. The utility of self-determination theory in predicting transition readiness in adolescents with special healthcare needs. J Adolesc Health. 2021;69(4):653–659. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.04.004. (Accessed Oct.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown P.C. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; Cambridge, Massachusetts: 2014. Make it stick: the science of successful learning. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller W.R., Rollnick S. Guilford Publications; 2023. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change and grow. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (2021). “Title V Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grant Measures Content Map, 2019–2020 National Survey of Children’s Health (two years combined)”. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health, supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB). 〈www.childhealthdata.org〉. Accessed 11/04/2021.

- 19.White P.H., Cooley W.C.; Transitions Clinical Report Authoring Group; American Academy of Pediatrics; American Academy of Family Physicians; American College of Physicians. Supporting the Health Care Transition From Adolescence to Adulthood in the Medical Home. Pediatrics. 2018;142(5):e20182587. Pediatrics. 2019 Feb;143(2):e20183610. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018–3610. Erratum for: Pediatrics. 2018 Nov;142(5): PMID: 30705144. 0031–4005. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2030, Objectives and Data, Adolescents, AH-02. 〈https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/adolescents/increase-proportion-adolescents-who-speak-privately-provider-preventive-medical-visit-ah-02〉. Accessed 11/30/2023.

- 21.Hergenroeder A.C., Wiemann C.M., Bowman V.F., Flanagan S. Impact of an Electronic Medical Record-based Transition Planning Tool on Health Care Transition Planning and Patient/Family Perception of this Planning for Children & Youth with Special Health Care Needs. Paper presented at: Pediatric Academic Societies/Society for Pediatric Research; April - May 2012; Boston, MA.

- 22.Katz A.L., Webb S.A. Informed consent in decision-making in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2) doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lugasi T., Achille M., Stevenson M. Patients' perspective on factors that facilitate transition from child-centered to adult-centered health care: a theory integrated metasummary of quantitative and qualitative studies. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48(5):429–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine Transition to adulthood for youth with chronic conditions and special health care needs. J Adolesc Health. 2020;66:631–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.02.006. PMID: 32331627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peter N.G., Forke C.M., Ginsburg K.R., Schwarz D.F. Transition from pediatric to adult care: internists' perspectives. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):417–423. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiener L.S., Kohrt B.A., Battles H.B., Pao M. The HIV experience: youth identified barriers for transitioning from pediatric to adult care. J Pedia Psychol. 2011;36(2):141–154. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armstrong K., McMurphy S., Dean L.T., et al. Differences in the patterns of health care system distrust between blacks and whites. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(6):827–833. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0561-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stivers T., Majid A. Questioning children: interactional evidence of implicit bias in medical interviews. Soc Psychol Q. 2007;70(4):424–441. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lerch M.F., Thrane S.E. Adolescents with chronic illness and the transition to self-management: a systematic review. J Adolesc. 2019;72:152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee C.C., Enzler C.J., Garland B.H., et al. The development of health self-management among adolescents with chronic conditions: an application of self-determination theory. J Adolesc Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reiss J.G., Gibson R.W., Walker L.R. Health care transition: youth, family, and provider perspectives. Pediatrics. 2005;115(1):112–120. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scal P., Horvath K., Garwick A. Preparing for adulthood: health care transition counseling for youth with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(1):52–57. doi: 10.1002/art.24088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis A.M., Brown R.F., Taylor J.L., Epstein R.A., McPheeters M.L. Transition care for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):900–908. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lotstein D.S., Ghandour R., Cash A., McGuire E., Strickland B., Newacheck P. Planning for health care transitions: results from the 2005-2006 National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):e145–e152. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McManus M., White P. Transition to adult health care services for young adults with chronic medical illness and psychiatric comorbidity. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2017;26(2):367–380. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2016.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McManus M., White P., Barbour A., et al. Pediatric to adult transition: a quality improvement model for primary care. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(1):73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quinn C.T., Rogers Z.R., McCavit T.L., Buchanan G.R. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2010;115(17):3447–3452. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-233700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Acuña Mora M., Saarijärvi M., Moons P., Sparud-Lundin C., Bratt E.L., Goossens E. The scope of research on transfer and transition in young persons with chronic conditions. J Adolesc Health. 2019;65(5):581–589. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.07.014. (Accessed Nov.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campbell F., Biggs K., Aldiss S.K., et al. Transition of care for adolescents from paediatric services to adult health services. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(4):CD009794. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009794.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wiemann C.M., Hergenroeder A.C., Bartley K.A., et al. Integrating an EMR-baSed Transition Planning tool for CYSHCN at a children's hospital: a quality improvement project to increase provider use and satisfaction. J Pedia Nurs. 2015;30(5):776–787. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2015.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buzi R.S., Smith P.B., Wiemann C.M., Peskin M.F., Chacko M.R., Kozinetz C.A. Project passport: an integrated group-centered approach targeting pregnant teens and their partners. J Appl Res Child. 2014;5(1):6. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wiemann C.M., Graham S.C., Garland B.H., et al. In-depth interviews to assess the relevancy and fit of a peer-mentored intervention for transition-age youth with chronic medical conditions. J Pedia Nurs. 2019;50:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2019.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wiemann C.M., Graham S.C., Garland B.H., et al. Development of a group-based, peer-mentor intervention to promote disease self-management skills among youth with chronic medical conditions. J Pedia Nurs. 2019;48:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2019.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hergenroeder A.C., Needham H., Jones D., Wiemann C.M. An intervention to promote healthcare transition planning among pediatric residents. J Adolesc Health. 2022;71(1):105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.01.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Culnane E., Loftus H., Efron D., et al. Development of the Fearless, Tearless Transition model of care for adolescents with an intellectual disability and/or autism spectrum disorder with mental health comorbidities. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2021;63(5):560–565. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harris J.F., Gorman L.P., Doshi A., Swope S., Page S.D. Development and implementation of health care transition resources for youth with autism spectrum disorders within a primary care medical home. Autism: Int J Res Pract. 2021;25(3):753–766. doi: 10.1177/1362361320974491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.