Abstract

Background

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic autoimmune disease often diagnosed during adolescence. IBD negatively impacts all aspects of health-related quality of life, resulting in physical, emotional, social, school, and work functioning challenges. Adolescents have identified the need for peer support in managing their disease and promoting positive health outcomes. However, studies have yet to explore the peer support needs of this population. The study aimed to capture whether a peer mentoring program (iPeer2Peer©) was successful at improving adolescent disease self-management. The study also aimed to understand the lived experiences of adolescents participating in iPeer2Peer©.

Methods

Adolescents with IBD were recruited from three tertiary hospitals in Canada. The study adopted a waitlist pilot randomized control trial (RCT) with participants randomly allocated to the intervention (iPeer2Peer© program) or control group. Participants completed questionnaire measures at baseline and post-program examining self-reported self-management, self-efficacy, emotional distress, social support, and health-related quality of life. A subset of intervention participants were randomly invited post-program to participate in a semi-structured interview to examine mentee program experiences

Results

The quantitative analyses showed no significant differences between the intervention and control group. Three themes were identified in the qualitative analysis: 1) forming a connection over shared experiences and beyond, 2) improving mentee program experience, and 3) program flexibility.

Conclusion

Despite the lack of significant quantitative outcomes, qualitative data suggests peer support for adolescents with IBD adds value to IBD care by developing a sense of belonging with peers who share lived experiences. This study demonstrates the complexity of mentee psychosocial needs and challenges in measuring outcomes in peer support research. Clinical implications and future research opportunities are discussed.

Keywords: Peer support, Inflammatory bowel disease, Adolescents, Virtual care, Mixed-method, Psychosocial functioning

1. Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic, incurable, autoimmune disease associated with inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. 1 The two primary forms of IBD which include Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are associated with alternating periods of remission and relapse. 2 Concerningly, IBD is often diagnosed during adolescence, with the prevalence of pediatric IBD having risen by over 50 % in the last 15 years and over 7000 children in Canada currently living with IBD. 3 The adolescent years are a particularly challenging time to be diagnosed with IBD. This is a crucial developmental period marking the transition from childhood to adulthood, and it is essential for psychosocial development.4 Adolescents with IBD experience an array of additional challenges on top of typical adolescent struggles due to the unpredictable course of the disease (e.g., related to obtaining, understanding, and accepting an IBD diagnosis) and frustrating treatment and management regimes (e.g., numerous lifestyle adjustments, modifications in diet and activities, changes in appetite and body, having to take medications). 5 However, while medical treatment aims to minimize physical disease activity, IBD and its treatment impact many areas of adolescent functioning beyond physical health.

Depression and anxiety are accentuated amongst adolescents after disease onset and when experiencing active IBD (e.g., inflammation, flare, symptoms) versus inactive IBD (e.g., in remission without symptoms, or in remission with symptoms). 6, 7 Additional research indicates that IBD patients often find the symptoms of their disease embarrassing and socially limiting, which often leads to difficulty disclosing their condition to peers, potentially causing further social isolation. 5, 8, 9, 10, 11 Adolescents with IBD report diminished control over their lives and perceive themselves as ‘different’ from their healthy peers and siblings. 12 Adolescence is an essential developmental stage associated with establishing an individual’s sense of identity and autonomy, which may be especially problematic for individuals with IBD who have difficulties with independence and social functioning.13

Providing care to adolescents with IBD during transition has been identified as a health priority. 14 There is a need to develop new programs, improve existing programs, and advocate for additional resources for IBD adolescents transitioning to adult care.14 Within the pediatric IBD transition literature, several guidelines have been outlined as key factors thought to promote successful transition, including emphasizing the importance of self-management, including increasing independent adolescent self-management skills, ongoing discussion of the transition period between patients and healthcare providers, and knowledge of disease and treatment. 15, 16 In the context of adolescence, an increase in self-management has been shown to positively impact the physical, social, and emotional quality of life.17 Greater involvement in self-management could be a mechanism to prevent the worsening of IBD (e.g., reducing inflammation, decreasing symptoms, improving quality of life) and facilitate the successful transition to adult healthcare.18, 19 Access to evidence-based psychosocial interventions for IBD is a significant care gap among individuals with chronic disease. 20, 21 In a qualitative study by Heisler and colleagues22 exploring IBD care barriers, 63 Canadian participants discussed the need for greater psychosocial support to help normalize the IBD experience and help further develop their coping skills. IBD patients who already had access to psychosocial support (e.g., services provided by healthcare professionals) reported the invaluable nature of this care to their overall physical, psychological, and emotional well-being.22 Patients with IBD have identified the importance of peer/social support, a form of psychosocial support offered by individuals with shared lived experience, in managing their disease and promoting positive IBD outcomes. 22, 23

In peer support programs, adolescents can be advocates and sources of support for effective chronic disease self-management. Although peer support among individuals with a similar chronic illness can be beneficial, most studies have focused on adult populations. 24, 25, 26 One peer support program developed at the Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) in Toronto, Canada, called iPeer2Peer©, piloted virtual modelling and positive reinforcement by adolescents who had learned to function successfully with their chronic disease (peer mentors) to adolescents with the same chronic illness (mentees).27 The investigators found program feasibility, acceptability, and improved health outcomes, including self-management amongst adolescents with chronic diseases (e.g., chronic pain and arthritis). 27, 28 By examining mentor experiences, peer mentors noted the importance of sharing a similar diagnosis or disease course with their mentee as an important contributor to developing a bond.29 Pediatric chronic illness research suggests that peer mentoring programs, such as iPeer2Peer©, might be effective with other populations such as IBD.27, 28, 30 However, there is a need to examine the effectiveness of peer support programs further to understand how to improve delivery. 31

This study examined mentee outcomes and experiences of an online peer mentorship program (iPeer2Peer©) for adolescent IBD patients. The objectives were twofold: to examine mentees’ perceived change in self-management, self-efficacy, resiliency, emotional distress (e.g., anxiety and depression symptomatology), perceived social support, and health-related quality of life (HRQL) and to explore mentee experiences of the virtual peer-mentoring program (iPeer2Peer©) through semi-structured interviews post-program. It was hypothesized that self-efficacy, self-management, resiliency, emotional distress, perceived social support, and HRQL ratings would significantly improve from baseline to post-intervention.27 Utilizing a waitlist randomized control trial (RCT), it was hypothesized that those using the iPeer2Peer© program would have improved outcome variables compared to the control group.

2. Material and methods

A mixed methods waitlist RCT design was used to examine the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of the iPeer2Peer© program in adolescents with IBD. Ethics approval was obtained through the institutions’ Research Ethics Boards at the Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids). This study was registered #58684.

2.1. Participants

Participants were recruited between December 2018 and May 2021 from three large pediatric hospitals across Canada: 1) SickKids; 2) Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO); and 3) Izaak Walton Killam Hospital for Children (IWK Health Centre). Participants were eligible to participate if they met the following criteria: (a) between the ages of 12 and 18 years old, (b) a gastroenterologist diagnosed IBD, (c) able to speak and read English, (d) access to a computer, smartphone, or tablet capable of using Skype software, and (e) willing and able to complete online measures. Exclusion criteria included: (a) significant cognitive impairments, (b) severe co-morbid illnesses (medical or psychiatric conditions) likely to influence HRQL assessment (e.g., psychosis, active suicidal ideation), or (c) participating in other peer support or self-management interventions.

2.2. Procedure

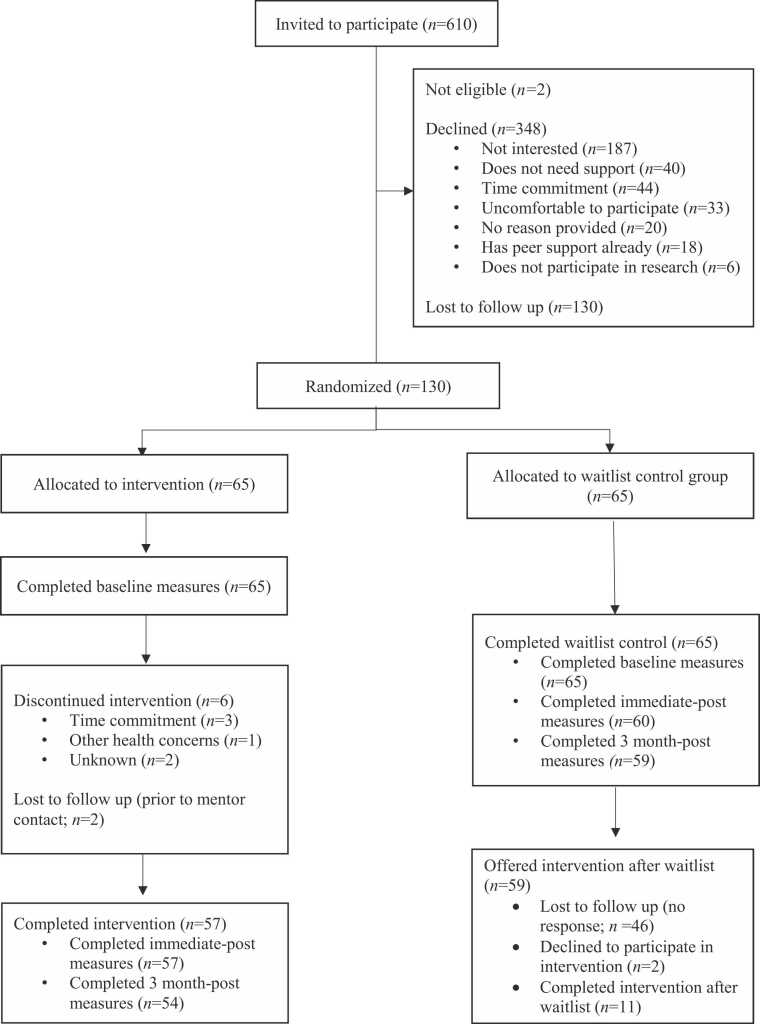

Eligible mentee participants were recruited from the gastroenterology departments at SickKids, CHEO, and IWK Health Centre using standard approaches (e.g., letters, posters, or being approached during a gastroenterology clinic by a healthcare provider). If interested, the Clinical Research Project Coordinator (CRPC) provided further information and obtained informed consent. Participants were sent the study questionnaires using a secure web application (REDCap32) at baseline (T1). Once these measures were complete, the participants were randomly allocated to the intervention or wait-list control group. The CRPC then contacted participants to inform them of their group assignment and instruct them on procedures (See Fig. 1 for CONSORT diagram). The randomization process was blinded to site-specific staff and co-investigators. All participants completed post-program questionnaires immediately post-program (T2) and six months post-program completion (T3). The CRPC followed up with each participant in accordance to the research institution guidelines to complete program questionnaires before being marked as lost to follow up (e.g., two emails or text messages, one phone call with a message, one final email or text message). Simple random sampling was used to try to obtain a representative sample (e.g., each iPeer2Peer mentee had an equal chance of being invited to participate in the interview). The CRPC approached approximately 40 % (n = 24) of mentees following the completion of the program to participate in a semi-structured interview. Participants received up to $45 in gift cards (e.g., a $10 gift card after completion of baseline measures, a $15 gift card at the end of the study mentorship calls, and a $20 after completing post-program questionnaires). Mentees who participated in the interview received an extra $10 gift card. Mentors participating in the program received a $20 gift card for completing the mentor training and $50 for each complete set of calls with mentee participants.

Fig. 1.

iPeer2Peer© CONSORT Diagram.

2.3. Experimental group

Participants in the experimental group received the iPeer2Peer© program. The mentoring program matched young adults (mentors aged 17–25 years old with IBD) who had successfully transitioned to adult care and learned to function successfully with their disease with mentees (adolescents 12–18 years old with IBD).27, 28 Efforts were made to match mentees with mentors with similar diagnoses, symptom profiles, sex, and treatment regime experiences (e.g., exclusive enteral nutrition, medications, surgical procedures). The program's goal was to encourage mentees to develop and engage in social support and self-management skill-building tailored to mentee needs. The iPeer2Peer© program consisted of 5–10, 20–30-minute Skype sessions over 5–12 weeks. The length of the program accounted for potential scheduling difficulties that emerged in previous studies and participant feedback on incorporating more flexibility within the program. 28 All Skype sessions were audio recorded, and a research team member reviewed sessions within 48 hours to ensure safety and fidelity to the iPeer2Peer© program. Mentee and mentor participants were asked to have one session per week. The session content was open-ended and tailored to each mentee’s expressed needs and desires during the calls. 29, 33, 34, 35

2.3.1. Mentor selection and training

In addition to having a diagnosis of IBD, peer mentors were nominated by their healthcare team based on maturity, emotional stability, and verbal communication skills. The study team screened and contacted each mentor to inform them of the study. If interested, the CRPC conducted an information and screening call with potential mentors where consent was obtained. Eligible and interested mentors were invited to attend a two-day in-person training workshop at [removed for blind review]. The workshops were facilitated by a health psychologist and a peer mentor trainer with lived experience of a chronic disease. Sessions also included an existing peer mentor with chronic pain, who shared their experience as a mentor in the iPeer2Peer© program. Mentors were trained in a standardized training protocol to focus the sessions on providing social support and encouraging participants to develop and engage in self-management skills. For more information on peer mentor selection and training, please refer to our study in the adolescent chronic pain sample. 27, 28

2.4. Control group

The control group received care as usual without the iPeer2Peer© program. After completing the post-control outcome measures, participants in the control group were offered the iPeer2Peer© program. Due to the institution’s research ethics restrictions, control participants were contacted via email and phone. If they did not respond with an interest in participating in the intervention, they were marked as lost to follow-up.

2.5. Outcome measures

Participants completed a brief background questionnaire at T1 to collect basic demographic information (i.e., current age, sex, IBD diagnosis, age at IBD diagnosis, school grade) for descriptive purposes. Participants completed an additional six measures at T2 and T3 to capture self-management (TRANSITION-Q),36 self-efficacy (IBD Self-Efficacy Scale),37 resiliency (Brief Resilience Survey),38 emotional distress (Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale),39 perceived social support (PROMIS Pediatric Peer Relationship Scale)40 and health-related quality of life (IMPACT-III),41 self-reported ratings.

Interviews followed a semi-structured cognitive-interviewing format, and interview guides were informed by research literature and clinical experience. 42 Questions asked mentees to comment on their program experience (e.g., “How did the first meeting go?”), mentor acceptability (e.g., “How did you get along with the mentor?”), program acceptability (e.g., “What did you like best/least about the program?”, “Would you recommend the program to another adolescent with IBD?”), including individual probes (e.g., “Were you worried about anything related to the peer-mentoring program?” and “What things do you have in common with your mentor?”). All interviews were conducted online using videoconference technology (Skype) and facilitated by the CRPC. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by a research team member.

2.6. Data analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed via linear mixed effects models, predicting T2 and T3 outcomes from treatment group, controlling for baseline outcome level, gender, age of enrollment, and site, using the lmer function from the lme4 package43 in R. 44 All available data was analyzed. Descriptive statistics were computed to describe the sample characteristics at each timepoint, using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. Interview data were analyzed according to the principles of Reflexive Thematic Analysis (RTA) within a data-derived (inductive level) critical realist framework (i.e., remaining close to the content and mirroring each participant’s language and concepts).45 RTA was chosen over other forms of qualitative analysis for its flexibility, which allowed coders to explore participants’ unique and nuanced perspectives, and its emphasis on reflexivity, enabling the research team to recognize how their beliefs, experiences, and interests informed the analysis. The coding team consisted of three coders engaged in various reflexivity practices (e.g., bi-weekly meetings and reflexive journaling).

3. Results

One hundred and thirty participants completed all baseline measures (Experimental group = 65, Control group = 65). See Fig. 1 for more information on participation at each timepoint. Mentee participants completed between one and ten calls (M = 6 calls, SD = 3 calls) lasting between 7 minutes and 1.5 hours (M = 32 minutes, SD = 14 minutes). On average, it took mentees 70 days (SD = 32 days) to complete the program from enrollment to the last call with their mentor. Eleven participants from the control group participated in the iPeer2Peer© program after completing the post-control outcome measures. Noteworthy, waitlist control participants had to wait approximately nine months (SD = 1.43) from the time of consent to be offered the intervention after they completed all study questionnaires at T3. See Table 1 for more information on participant demographic and disease characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographic and Disease Characteristics of Participants.

| Characteristic | iPeer2Peer Program (n=65) | Control (n=65) |

|---|---|---|

| Participants (total n = 130) | ||

| Age at Enrollment in years, M(SD) | 14.70 (1.78) | 14.54(1.66) |

| Age at Diagnosis in years, M(SD) | 11.26(3.44) | 11.26(3.44) |

| IBD Diagnosis Type, n (%) | ||

| Crohn’s Disease | 42(65 %) | 38(59 %) |

| Ulcerative Colitis | 22(34 %) | 23(35 %) |

| IBDUa | 1(1 %) | 4(6 %) |

| Sex Assigned at Birth, n (%)b | ||

| Female | 31(48 %) | 41(63 %) |

| Male | 33(52 %) | 24(37 %) |

| Grade, M(SD) | 9.6(1.74) | 9.4(1.77) |

| Mentors (n = 20) | ||

| Age at Enrollment, M(SD) | 20.4(2.4) | |

| Age at Diagnosis, M(SD) | 13.2(2.5) | |

| IBD Diagnosis Type, n (%) | ||

| Crohn’s Disease | 17(85 %) | |

| Ulcerative Colitis | 3(15 %) | |

| IBDUa | 0(0 %) | |

| Sex Assigned at Birth, n (%) | ||

| Female | 12(60 %) | |

| Male | 8(40 %) |

Note.

IBDU = Inflammatory Bowel Disease Unclassified.

One participant did not disclose sex.

3.1. Objective 1: quantitative program experience

For each timepoint, at alpha =.05, there were no statistically significant differences between intervention and control group on secondary outcomes, including self-efficacy, self-management, resiliency, emotional distress, perceived social support, and HRQL. The same general pattern of results was found whether including covariates (baseline outcome level, gender, age of enrollment, and site) or not. See Table 2 for summary scores across all measures and time points.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations of Quantitative Outcome Measures.

| Possible Range |

Pre |

P Value |

Post |

P Value |

6 mo |

P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | n | M(SD) | n | M(SD) | n | M(SD) | ||||

| IBD self-management | 0–100 | .955 | .692 | .988 | ||||||

| iPeer2Peer | 65 | 57.97(13.53) | 57 | 60.43(13.57) | 54 | 62.06(14.74) | ||||

| Control | 65 | 57.83(14.60) | 60 | 59.43(14.00) | 59 | 62.10 (17.02) | ||||

| Quality of Life | 0–100 | .866 | .322 | .331 | ||||||

| iPeer2Peer | 65 | 70.67(13.20) | 57 | 74.00(11.59) | 54 | 75.88(12.78) | ||||

| Control | 65 | 71.04(12.78) | 60 | 71.77(12.97) | 59 | 73.45(13.86) | ||||

| IBD Self-Efficacy | 13–65 | .744 | .690 | .543 | ||||||

| iPeer2Peer | 65 | 49.66(7.14) | 57 | 50.40(6.57) | 54 | 51.59(5.75) | ||||

| Control | 65 | 50.05(6.53) | 60 | 50.89(6.85) | 59 | 50.90(6.16) | ||||

| Resilience | 0–5 | .490 | .057 | .055 | ||||||

| iPeer2Peer | 65 | 3.41(0.72) | 57 | 3.48(0.71) | 54 | 3.53(0.69) | ||||

| Control | 65 | 3.33(0.70) | 60 | 3.23(0.69) | 59 | 3.26(0.79) | ||||

| Anxiety+ | 0–100 | .260 | .614 | .752 | ||||||

| iPeer2Peer | 65 | 45.98(10.45) | 56 | 45.19(10.80) | 54 | 44.85(12.42) | ||||

| Control | 65 | 48.16(11.35) | 60 | 46.20(10.76) | 59 | 45.55(10.40) | ||||

| Depression+ | 0–100 | .682 | .466 | .785 | ||||||

| iPeer2Peer | 65 | 47.28(11.48) | 57 | 47.54(11.56) | 54 | 48.44(11.77) | ||||

| Control | 65 | 48.09(10.91) | 60 | 49.22(13.39) | 59 | 49.07(12.32) | ||||

Note.+ = T-scores are reported

3.2. Objective 2: qualitative program outcomes

Twenty-four mentee participants were randomly selected and invited to participate in a semi-structured interview immediately after completing the iPeer2Peer© program. Three themes were identified, and five subthemes represented the mentee’s experience in the iPeer2Peer© program: positive program experience, barriers to program engagement, and solutions to increase engagement and delivery.

3.2.1. Theme 1. Forming a connection over shared experiences and beyond

Mentees often discussed factors contributing to their positive program experience, including receiving support from someone who understood living with IBD, being paired with a mentor who offered guidance and advice, and developing a strong relationship with their mentor. All interviewed participants (N = 24) who completed the program during this time reported having an enjoyable experience and indicated they would recommend the iPeer2Peer© program to peers with IBD. The three subthemes are presented below (support from someone who gets it, mentor as a source of guidance and support, and developing a strong relationship with a mentor).

3.2.1.1. Support From Someone Who Gets It

Participants discussed enjoying the connection with another young person who shared a similar experience living with IBD. Specifically, mentees acknowledged appreciating connecting with another peer who understood the disease aspect of being an adolescent living with IBD. Many mentees noted they had never connected with a peer also diagnosed with IBD. Mentees also reported that connecting with “someone who gets it” helped normalize the experience of living with IBD as a young person, inspiring hope regarding future outcomes and what they could accomplish as they got older. For example, one mentee recalled the difference between talking to a peer with IBD versus their parents or medical team:

It's hard to talk like your parents or siblings and people and your friends who don't really know exactly what you're going through, but I think it was just really nice to have someone that, kind of gone through it (14-year-old female diagnosed with CD).

Moreover, mentees noted feeling less alone and isolated through the conversations with their mentor. One mentee noted, “It kind of gave me more clarity with my disease, like that I'm not in it alone and that there’s always going to be people out there who will be able to support me and know what I'm going through” (17-year-old female diagnosed with CD).

3.2.1.2. Mentor as a Source of Guidance and Support

Mentees discussed the role of their mentor as a beacon of support and guidance throughout the iPeer2Peer© program. Specifically, mentees noted that their mentor provided advice on the logistics of living with IBD, including diet, different types of medication, and adopting a “healthy lifestyle.”

Mentees also discussed the importance of receiving non-IBD-related advice from their mentors, including scheduling their own time, what clubs to join in school, what university was like, and how to navigate social situations. Overall, mentees described that they gained valuable knowledge from their mentors, including disease-specific information and other topics they had yet to consider due to their participation in the iPeer2Peer© program.

3.2.1.3. Developed a Strong Relationship With a Mentor

Mentee participants discussed the importance of forming a strong relationship with their mentor to facilitate a positive experience with the iPeer2Peer© program. Participants discussed specific mentor characteristics, such as the mentor's age and disease experience, as essential in developing a strong mentee-mentor relationship. Specifically, ensuring the mentor was older and had the disease for longer than the mentee. One mentee noted that the age gap with their mentor was initially awkward, but they grew to appreciate having an older, more experienced mentor: “I feel like at first it was like a little awkward talking to someone older than me like…then I really liked her, and I really like the age difference 'cause I feel she knew more and have more information to give me” (13-year-old female diagnosed with CD). Mentees also discussed the importance of having things in common with their mentors regarding their diagnosis (e.g., CD, UC), hobbies, and interests outside their diagnosis. Mentees noted that sharing non-illness-related interests and similar IBD disease-related experiences helped contribute to the flow of conversation and being able to relate to the mentor.

3.2.2. Theme 2. Improving Mentee Program Experience

Participants also discussed specific factors to address in future peer support iterations to improve the program experience. This theme captured improving the mentee-mentor fit and technological/scheduling barriers. Two subthemes are presented below (improving mentee-mentor fit, technical and scheduling difficulties).

3.2.2.1. Improving mentee-mentor fit

While many participants described having a pleasant experience with their mentor, some mentees noted that the mentee-mentor pairing could have been better. Specifically, some mentees expressed little in common with their mentor regarding their diagnosis (e.g., UC, CD) symptoms (e.g., flare-ups), and non-disease related factors, making it difficult to connect. Moreover, mentees noted the mentee-mentor pairing would have benefitted from considering whether they were both shy/introverts: “I get along with her pretty well. It wasn't like I didn't get along with her. I just guess it was like we are both shy and she wasn't like a big talker” (14-year-old female diagnosed with UC). Along the same lines, some participants noted their mentors would have benefitted from more direction from the iPeer2Peer© team to make expectations more transparent from the start: “[the mentor] was trying to mostly keep the conversations IBD focused, so it's like just maybe that communication of if it's gonna be completely IBD focused or if it's not, and that just making a little more clear” (16-year-old female diagnosed with CD). For some, awkward conversations between mentees and mentors made connecting and holding a conversation challenging.

Mentees summarized the potential value of improving the mentee-mentor match process to ensure disease characteristics (e.g., current symptoms, disease type, how long since diagnosed) and interests (e.g., hobbies, TV shows, sports, food) were considered with each pairing. One mentee noted the value of being matched with a mentor who was also experiencing similar symptoms and shared similar interests outside of their disease to help ensure the pairing could relate to one another.

I think, obviously, it's hit or miss whether like two people can connect or relate to things, but I think definitely having a bit more of similar diagnoses would help like them relate to each other, even though everybody’s lives obviously differentiate a lot, but I would still of course recommend it to somebody with IBD (15-year-old female diagnosed with UC).

One mentee recommended providing a formal survey to all mentees and mentors to collect information regarding current interests, hobbies, disease symptoms, and characteristics. She noted that interests and IBD symptoms often change fast for a young person.

3.2.2.2. Technical and scheduling difficulties

Mentee participants also discussed barriers related to technology and scheduling. These barriers were communicated vividly when some mentees remembered unexpected disruptions during Skype calls with their mentor (e.g., a call disconnecting or freezing). Some mentees recalled frequent “dropped” calls with their mentor, resulting in long periods of troubleshooting and initially not understanding how to download or navigate the technology. The difficulty associated with scheduling and finding the time to meet with mentors was also communicated by mentees. Some participants noted occasionally missing scheduled calls due to forgetting, being sick, or having things come up at the last minute. Other participants recalled how difficult it was to find a consistent time to meet with their mentor each week due to their variable schedule and living situation, still noting the benefits of participating in the iPeer2Peer© program.

3.2.3. Theme 3. Program flexibility

Finally, participants discussed appreciating the existing flexibility within the iPeer2Peer© program and the need for even more flexibility to be incorporated within the program to increase participant engagement and program delivery. The existing flexibility in the iPeer2Peer© program was reported as a helpful factor by mentees, who noted they appreciated how the program met their current needs. Mentees said they specifically appreciated the flexibility in conversation topics (e.g., the unstructured nature of the program) and being able to spend more or less time discussing disease-specific content versus lifestyle and interests. One participant expressed enjoying the flexibility in content throughout the program: “I thought it was really cool because, like, we weren’t always just talking about like Crohn’s disease. She was kind of like giving me like life advice in a way” (14-year-old female diagnosed with CD). Participants also noted enjoying the flexibility with the duration and the number of calls with their mentor. Some mentees noted they had shorter calls, while others reported having longer and more frequent calls. The virtual modality of the program was also described as a strength, with mentees noting they would prefer it over in-person. Mentees discussed appreciating being able to schedule their calls directly with their mentor, especially if they had a flare-up and needed to reschedule at the last minute. One mentee noted, “If I wasn't feeling well or she wasn't feeling good, we will just reschedule for like another day” (12-year-old female diagnosed with CD). Mentee participants described satisfaction with the flexibility provided throughout the iPeer2Peer© program.

However, many participants described wanting more flexibility provided throughout the iPeer2Peer© program. Mentees noted the program would benefit by giving more options to the mentees/mentors regarding what platform to use for mentorship calls (e.g., Skype, Zoom, Facetime, Google Hangouts, Phone, Text) and notification system (e.g., text, email, Skype). One mentee recalled not having a phone and relying on text notifications from their iPad connected to their parent’s cellphone to receive meeting updates. Another mentee noted how providing more options regarding the platform and how they received notifications for upcoming meetings would help address individual preferences. Mentees discussed the option to meet their mentor in person or have an opportunity to have all or some mentorship meetings in person if feasible (e.g., if the mentee and mentor lived nearby).

Mentee participants discussed wanting more flexibility regarding the duration of the calls and how many calls, ultimately wanting to leave the program duration and ‘dose’ (i.e., how many calls and the duration of calls) up to the mentee and mentor. Some mentees noted their preference for wanting more calls (e.g., extending the program) to get to know and connect with their mentor better.

4. Discussion

This study sought to explore whether online peer mentorship, via the iPeer2Peer© Program, would improve adolescent IBD self-management skills. Compared to the control group, there were no statistically significant changes over time for the quantitative variables of interest (self-management, self-efficacy, emotional distress, social support, or health-related quality of life). Although peer support programs have been linked with positive patient health outcomes, including improving an individual’s ability to self-manage their disease 27, it is difficult to know what specific factors led to improvements in these variables. Moreover, previous iPeer2Peer© pilot studies among adolescents with chronic diseases 33 have shown mixed results, with some reporting no significant quantitative improvement in emotional distress or self-efficacy from baseline to post-program. 46 Research has noted the difficulty of directly targeting psychological outcomes in peer support programs 47 with the consensus that it may have to do with the relational nature of these programs and individual characteristics, including mentor competence and patient dispositional traits.48

More broadly, the RCT design may not have been the most suitable choice to capture changes in the outcome variables of interest. Although the RCT is considered the gold standard for testing the efficiency of treatment, Carey and Stiles 49 argue that RCT’s may not be suitable in psychological studies. Specifically, Carey and Stiles 49 posit that treatment techniques are a small part of what contributes to psychological change, RCT’s attribute improvement in clients mental state solely to the treatment (i.e., ignoring the client as an active agent in the process), and it is hard to define what the treatment is and thus what should be measured. Moreover, the authors highlight that changes due to psychological interventions are often not linear and multiple variables contribute to psychological change, making it difficult to capture numerically.

Moreover, adolescents in this study were not screened or selected based on elevated clinical scores at baseline. According to the RCADS cut-off score39, the mean scores for emotional distress for the mentee participants were in the normal range at baseline and post-program. Thus, this study’s sample presents with relatively low levels of emotional distress overall. The study also did not systematically measure why adolescents enrolled in the iPeer2Peer© program before randomization (e.g., for social support, to learn self-management, to improve mental health, to support resilience).

Despite the lack of statistically significant outcomes in the quantitative analysis, the qualitative findings provide guidance on the benefits and implementation improvements for the iPeer2Peer© program. The reflexive thematic analysis results for objective two helped elucidate adolescent mentee experiences of the iPeer2Peer© program. Three overarching themes and associated subthemes were identified in the qualitative data analysis. The overarching theme ‘Forming a Connection Over Shared Experiences and Beyond’ highlighted the overall pleasant mentee experiences with the peer support program, including enjoying connecting with a peer over IBD and beyond. The overarching theme ‘Improving Mentee Program Experience’ highlighted factors to improve mentee’s program experience, such as enhancing the mentee-mentor fit and technical and scheduling difficulties. Finally, the overarching theme ‘Program Flexibility’ captured the mentee’s positive experience of being able to schedule their meetings directly with the mentor and having control of the duration of calls, and the desire to incorporate more flexibility within the program (e.g., allowing the mentee and mentors to choose the modality for their meetings).

4.1. Forming a connection over shared experiences and beyond

Mentees touched upon the importance of connecting with a peer who understood the disease aspect of their life. They mentioned that although parents, siblings, friends, and doctors are essential supports, they do not necessarily understand what it is like living with IBD. Consistent with previous research examining content discussed during peer mentoring sessions amongst adolescents with chronic disease, our research team identified that 36.25 % of transcripts reviewed discussed mentee and mentor personal experiences living with a chronic disease.50 Specifically, mentees and mentors discussed similarities and differences regarding their disease experiences and how their illness impacted their daily lives (e.g., ability to manage post-secondary education, relationships, employment, and hobbies).

Moreover, mentees noted that mentors acted as sources of support and guidance, specifically regarding the logistics of living with IBD as an adolescent, by sharing their lived experiences. For example, mentees discussed enjoying being able to hear their mentors describe their own experience with certain medications and navigating post-secondary education. The exchange of support and guidance has also been identified in other qualitative studies, such as Arney et al. 24, who reported that mentees participating in a peer support program for adults with diabetes exchanged informational support (e.g., exchange of recipes and exercise routines). The peer mentorship program created a learning environment for mentees to acquire knowledge for personal growth and suggestions to navigate the transition period of adolescence and healthcare from a peer who had personal experience living with IBD. Ultimately, the iPeer2Peer© program appeared to target the mentee’s desire to connect/relate to another young person who truly understood what it was like to live with IBD, aiding in the transfer of guidance and advice and highlighting the potential utility of the peer support program.

While the disease aspect of peer mentorship is important, the present study highlights many factors that impact the development of a good mentee/mentor pairing. IBD mentees discussed the importance of developing a strong relationship with their mentor to get the most out of the program. Specifically, mentees emphasized the value of ensuring both the mentee and mentor had non-disease-related similarities, including hobbies and interests. Hence, they had topics to discuss outside of their disease. Reflected in other research, non-disease-related content is commonly discussed in peer support programs (48.86 % of the time among adolescents with a chronic disease). Specifically, mentors and mentees spent time getting to know each other and further developing their relationships through discussions regarding their interests, family, and current events.50

Similarly, a qualitative study exploring young adult mentor experiences following participation in the iPeer2Peer© program for adolescents with chronic illness noted mentors described building relationships with mentees that went beyond the disease, providing mentorship around everyday life stressors, interests/hobbies, families, and friends.29 Importantly, mentors discussed that developing a relationship with mentees took time and was influenced by multiple factors, including demographic characteristics, whether the mentee and mentor shared the same diagnosis, age of illness at onset, sex, and the age difference between mentor and mentee. Ultimately, mentors noted that the more similar the mentor and mentee pairings, the more quickly the connection was developed and deepened. 29, 51

4.2. Improving the mentor-mentee match

Understandably, mentees emphasized the importance of matching mentees and mentors based on a multitude of factors, including disease type (e.g., CD, UC), disease severity (e.g., remission, relapse), and non-IBD factors such as interests (e.g., hobbies, sports). Similarly, Wanstall and Ahola Kohut52 found stronger program outcomes when mentors utilized the synchronous use of “I” (e.g., disclosing personal information), discussion of friendships, focus on the future, and discussion of leisure/hobbies. Just as mentees emphasized the importance of forming a strong relationship with their mentor to enhance their overall program experience, some mentees did not have a lot in common with their mentor, such as overall disease experience (e.g., current disease symptoms, age at diagnosis) or non-disease related interests such as hobbies finding it more difficult to form a relationship. While the authors tried to recruit mentors with a wide range of disease presentations and to consider disease experience in the matching process, these efforts were not always successful due to the evolving complexity of IBD presentations, the diverse interests of adolescents, and scheduling conflicts.

A lack of connection between mentees and mentors has also been identified as a theme in other qualitative studies, such as Sweet et al.53, who examined mentors and mentees' experience participating in a peer mentorship program for individuals diagnosed with a spinal cord injury. A qualitative study examining early warning signs or red flags in youth mentoring relationships noted that forming a connection between the mentor and mentee was an important factor in successful mentoring. 54 In this study, some mentees acknowledged inadequate pairings with their mentor, noting that their disease experience (e.g., current symptoms, IBD types, age of diagnosis, comorbidities) and current interests (e.g., hobbies, sports, TV) were not aligned, making it difficult to connect. Some mentee participants recommended incorporating a survey documenting the mentor and mentee's current disease characteristics and non-disease-related information, such as hobbies. There needs to be more guidance regarding the best matching practices when deciding on mentee-mentor pairings, with even more ambiguity regarding specific populations such as IBD adolescents. Although research indicates that adopting matching strategies is vital for successful mentorships, MacCallum and colleagues54 argue they need to be more successful in ensuring suitable interpersonal matches between mentors and mentees, with connections sometimes not forming even when careful efforts are made. Although incorporating a questionnaire documenting current disease characteristics and interests seems promising, an algorithm may not ensure a successful match.

In addition, some mentees described encountering awkward exchanges or times of silence with their mentor. Incorporating more consistent mentor supervision or check-in sessions throughout the program to ensure mentors are adequately equipped with the tools and knowledge they received in training may assist in reducing ‘awkward’ exchanges. In this study, mentor training occurred over two days following a standardized training protocol for educating mentors on components of good mentorship, increasing confidence in providing mentorship, and improving mentors' informational, emotional, and appraisal support skills. However, during the study, mentors may have begun mentoring months after training. Thus, although they were provided with a copy of the training manual, which provided various materials such as example topics to discuss with their mentee, critical training knowledge may have diminished with time. Although this study encouraged mentors to check in with the study team when needed, no formal ongoing supervision was incorporated unless indicated during the audio call review. This study sheds light on the need to implement formal continuous mentor supervision and/or refreshers to aid in the service of good mentorship.

4.3. Program flexibility

Mentee participants explained the importance of the flexibility provided throughout the iPeer2Peer© program regarding the length of the calls, the number of mentoring sessions, topics discussed, and scheduling directly with their mentor. The existing flexibility incorporated throughout the program contributed to the mentee’s positive experience with the iPeer2Peer© program. These findings are unsurprising as previous studies have found that mentees desire more flexibility and individualized treatment to be threaded within the program to account for the variation in adolescent needs and desires. 27 For example, in a systematic review exploring peer support interventions for adolescents with chronic disease, the number of peer contacts, length of the program, and focus of the meetings (e.g., disease education, group activity, 1:1 mentoring) varied significantly.34 Moreover, given that IBD is a condition characterized by disease flare-ups creating uncertainty amongst patients, the role of flexibility seems promising, especially amongst adolescents who tackle additional challenges such as physical and social transitions and busy schedules. This study emphasized that there is no “one size fits all” peer support model, introducing a challenge to conventional research designs. Tension exists between the flexibility desired by adolescents and fidelity to the peer support model to ensure efficacy. To account for this tension, Fisher et al.55 advocate for ensuring fidelity within the key functions that define peer support (e.g., assistance in daily management, social and emotional support, linkage to clinical and community resources) rather than focusing on specific implementation protocols.

In addition, mentees discussed technical and scheduling difficulties as barriers to engaging in the iPeer2Peer© program. Mentees reported disruptions due to virtual calls dropping, freezing, slow WIFI, or not knowing how to navigate technology. Consistent with the literature, the challenge of finding the time to meet with mentors due to various factors, including a busy schedule, illness, obligations that emerge last minute, or forgetfulness, were also discussed.5 Ultimately, due to various factors, mentees reported challenges finding a consistent time to meet with their mentor each week. The unpredictability of adolescent schedules and the difficulty surrounding the use of technology is not unique to this study. In a feasibility study examining iPeer2Peer© amongst adolescents with chronic pain or juvenile idiopathic arthritis, mentors described the logistical issues, including scheduling and technical issues that emerged throughout the program.29 Specifically, mentorship calls were often re-scheduled due to exams, medical appointments and medical issues, resulting in longer gaps between calls and internet connectivity or internet speed affecting the flow of conversation.29 In the current study, although some barriers related to scheduling and the use of technology were also reported, the online nature of the program was described as a strength of the program that provided flexibility and compassion for their busy schedules. Aligned with the literature, virtual care delivery is preferred amongst IBD patients who view it as a strategy to address barriers to care prohibited by geographic location, their unpredictable disease course, and limited time and resources. 56 Thus, the virtual modality of iPeer2Peer© seems promising in adequately meeting the demands of the unpredictable nature of adolescents with IBD.57

Mentees also reported ultimately wanting to be in control of how they interacted with their mentor. Although mentees described enjoying the flexibility currently intertwined with the iPeer2Peer© program, they identified the need for even more flexibility to be incorporated throughout the program. Although this study’s institutional ethics board only permitted Skype,

mentees suggested future iterations provide more options to the mentee-mentor pairing regarding which platform to use for the mentoring meetings (e.g., Skype, Zoom, Google Hangouts, Facetime) and notifications of upcoming meetings. Leaving the decision up to the mentee and mentor regarding the duration of calls (e.g., 10 minutes, 1 hour), how many calls, explicitly being able to have as many or few calls as needed, and the option to meet in-person at least once if feasible (e.g., if the mentee and mentor lived in proximity). Studies of the iPeer2Peer© Program in other disease populations have included the use of WhatsApp, texting and a more flexible calling structure to respond to this need.58 Ultimately, mentees acknowledged appreciating the existing flexibility intertwined in the iPeer2Peer© program, including being in control of scheduling meetings and the length/duration of the calls but encouraged more flexibility to be adopted to help customize the program to meet individual needs and preferences. This was the first study to specifically ask mentee adolescents with IBD about their experience with a peer support program. The qualitative findings identify three factors to consider when implementing a peer-to-peer program for adolescents with IBD to target desired components and areas of improvement to enhance the mentee experience.

4.4. Clinical implications

In a qualitative study by Heisler and colleagues22 exploring IBD care barriers, 63 Canadian participants discussed the need for psychosocial support to help normalize the IBD experience and help further develop their coping skills. Patients with IBD identified the importance of peer/social support offered by individuals with shared lived experience, in managing their disease and promoting positive IBD outcomes.22, 23 In this study, adolescents with IBD reported positive program experiences, with all participants indicating they would recommend iPeer2Peer© to their peers. This research is the first to highlight the utility of peer support programs for adolescents with IBD. As more organizations offer peer-to-peer programs for IBD patients, such as Crohn’s and Colitis Canada,59 it is essential to continue evaluating and improving the psychosocial support for this population, attempting to optimize the positive aspects of program experience and associated outcomes. 60

There is also a need to adapt psychosocial interventions to meet the needs of patient populations. Incorporating individualized treatment/personalized medicine to suit individual needs could allow standardized interventions to be applied flexibly across various populations or resulting difficulties. Supporting our findings, it is clear that patients prefer personalized interventions (e.g., mentees remain in charge of setting goals, preferences for topics discussed) and that personalization enhances adherence and intervention engagement. 61 Moreover, incorporating flexibility within treatment (e.g., listening to the patient regarding platform preference, duration, and frequency of calls) may be more inclusive to accommodate patient needs and competing life demands. Programs should be designed to meet the unique needs of adolescents by incorporating flexibility, choice, and autonomy to allow adolescents to feel involved in the process and take ownership of their continued involvement. 62, 63

4.5. Limitations & future directions

The findings of this study must be interpreted considering several limitations. First, challenges emerged during the recruitment process, as out of the 610 individuals invited to participate in the study, only 130 consented (see Fig. 1). It is possible the participants who would have benefited the most from the iPeer2Peer© program did not participate in the study. Future research may benefit from offering a secondary level of participation to gather demographic data to better characterize this group and adjust the program that may better fit the needs of those who declined to participate. Future research would also benefit from capturing mentees' motivation and self-reported goals for participating in such programs and examining individual program outcomes in addition to group differences pre- and post-program. Second, more females (n = 16) participated in the semi-structured interview than male participants (n = 8), and more mentees diagnosed with CD (n = 19) than UC (n = 4) or IBD unclassified (n = 1) participated. This study utilized simple random sampling to ensure that each mentee had an equal chance of being invited to participate in the semi-structured interview. However, the simple random sampling design did not select participants based on sex or IBD type. Additionally, both mentee and mentor participants were predominately White, lacking representation from minority groups. Furthermore, the current study only collected binary sex information, highlighting the need for future research to include more diverse IBD populations and adopt a gender-sensitive approach to analysis highlighted mentees reported benefitting from the peer support program.

4.6. Conclusions

Providing care to adolescents with IBD, specifically during the transition period from pediatric to adult care, remains a health priority. 14 This study aimed to explore whether a peer support program – iPeer2Peer© was associated with improved health outcomes and to capture the experiences of IBD adolescents as mentees in the program. This study highlights the limitations of relying solely on numerical measurement, raising important questions about the appropriateness of RCTs for capturing meaningful outcomes in complex interventions. Compared to the control group, there were no statistically significant changes over time for the quantitative variables of interest. Future research is encouraged to measure individual trajectories and mentee’s rationale for participating in a peer intervention. Despite the lack of statistically significant outcomes in the quantitative analysis, the qualitative findings highlight the benefit of the peer support program. Mentees described gaining helpful advice and guidance from mentors regarding living with IBD and appreciating the existing flexibility provided by the program that was compatible with their unpredictable disease course and busy schedules as adolescents. Program adaptations are recommended, including improving the mentee-mentor match process, increasing the flexibility within the program, and implementing consistent mentor check-ins. Ultimately, this study provides insight into the benefits of incorporating peer support for adolescents with IBD within traditional care to bolster connectedness and enhance this population’s well-being. Peer-to-peer programs targeting adolescents with IBD are still in their infancy, and future research is encouraged to ensure optimal and appropriate care.

Funding/financial statement

This work was generously supported by Crohn's and Colitis Canada [Grant-in-Aid of Research]. Dr. Ahola Kohut's salary was also supported from the Lassonde Family Precision IBD Initative.

Ethical statement

This study was granted ethical approval by the Hospital for Sick Children (approval no. #58684). All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment in the study.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Meghan Ford: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Armanda Iuliano: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition. Thomas D Walters: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Anthony R Otley: Writing – review & editing. David R Mack: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Kevan Jacobson: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Jason D Rights: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. Dean A Tripp: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Jennifer N Stinson: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization. Sara Ahola Kohut: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability

The authors do not have permission to share data.

References

- 1.Kaplan G.G., Ng S.C. Understanding and preventing the global increase of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(2):313–321.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine A., Koletzko S., Turner D., et al. ESPGHAN revised porto criteria for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58(6):795–806. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carroll M.W., Kuenzig M.E., Mack D.R., et al. The impact of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada 2018: children and adolescents with IBD. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2019;2(1):S49–S67. doi: 10.1093/jcag/gwy056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanders R.A. Adolescent psychosocial, social, and cognitive development. J Pediatr Rev. 2013;34(8):354–358. doi: 10.1542/pir.34-8-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barned C., Fabricius A., Stintzi A., Mack D.R., O'Doherty K.C. The rest of my childhood was lost": canadian children and adolescents' experiences navigating inflammatory bowel disease. Qual Health Res. 2022;32(1):95–107. doi: 10.1177/10497323211046577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mikocka-Walus A., Andrews J.M., Bampton P. Cognitive behavioral therapy for IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(2):E5–E6. doi: 10.1097/mib.0000000000000672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sewitch M.J., Abrahamowicz M., Bitton A., et al. Psychological distress, social support, and disease activity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(5):1470–1479. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9270(01)02363-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter B., Rouncefield-Swales A., Bray L., et al. I don't like to make a big thing out of it": a qualitative interview-based study exploring factors affecting whether young people tell or do not tell their friends about their IBD. Int J Chronic Dis. 2020;2020:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2020/1059025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qualter P., Rouncefield-Swales A., Bray L., et al. Depression, anxiety, and loneliness among adolescents and young adults with IBD in the UK: the role of disease severity, age of onset, and embarrassment of the condition. Qual life Res. 2020;30(2):497–506. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02653-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Youth and parent illness appraisals and adjustment in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. doi:10.1007/s10882-019-09678-0. Springer; 2019.

- 11.Rouncefield-Swales A., Carter B., Bray L., et al. Sustaining, forming, and letting go of friendships for young people with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): a qualitative interview-based study. Int J Chronic Dis. 2020;2020:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2020/7254972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicholas D.B., Otley A., Smith C., Avolio J., Munk M., Griffiths A.M. Challenges and strategies of children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: a qualitative examination. Health Qual life Outcomes. 2007;5(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubin K.H., Bukowski W.M., Laursen B.P. Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups. Guilford Press; 2009. Social, emotional, and personality development in context. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu N., Bollegala N., Jacobson K., et al. Canadian consensus statements on the transition of adolescents and young adults with inflammatory bowel disease from pediatric to adult care: a collaborative initiative between the Canadian IBD transition network and Crohn’s and Colitis Canada. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2022;5(3):105–115. doi: 10.1093/jcag/gwab050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gray W.N., Resmini A.R., Baker K.D., et al. Concerns, barriers, and recommendations to improve transition from pediatric to adult IBD care: perspectives of patients, parents, and health professionals. Inflamm bowel Dis. 2015;21(7):1641–1651. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gumidyala A.P., Greenley R.N., Plevinsky J.M., et al. Moving on: transition readiness in adolescents and young adults With IBD. Inflamm bowel Dis. 2018;24(3):482–489. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izx051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cramm J.M., Strating M.M.H., Roebroeck M.E., Nieboer A.P. The importance of general self-efficacy for the quality of life of adolescents with chronic conditions. Soc Indic Res. 2013;113(1):551–561. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0110-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamat N., Ganesh Pai C., Surulivel Rajan M., Kamath A. Cost of Illness in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(9):2318–2326. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4690-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaufman M. Role of adolescent development in the transition process. Prog Transplant. 2006;16(4):286–290. doi: 10.1177/152692480601600402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halloran J., McDermott B., Ewais T., et al. Psychosocial burden of inflammatory bowel disease in adolescents and young adults. Intern Med J. 2021;51(12):2027–2033. doi: 10.1111/imj.15034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michel H.K., Kim S.C., Siripong N., Noll R.B. Gaps exist in the comprehensive care of children with inflammatory bowel diseases. J Pediatr. 2020;224:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heisler C., Rohatinsky N., Mirza R.M., et al. Patient-centered access to IBD care: a qualitative study. Crohn'S Colitis 360. 2023;5(1) doi: 10.1093/crocol/otac045. otac045-otac045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swarup N., Nayak S., Lee J., et al. Forming a support group for people affected by inflammatory bowel disease. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:277–281. doi: 10.2147/ppa.S123073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arney J.B., Odom E., Brown C., et al. The value of peer support for self-management of diabetes among veterans in the Empowering Patients In Chronic care intervention. Diabet Med. 2020;37(5):805–813. doi: 10.1111/dme.14220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaselitz E., Shah M., Choi H., Heisler M. Peer characteristics associated with improved glycemic control in a randomized controlled trial of a reciprocal peer support program for diabetes. Chronic Illn. 2019;15(2):149–156. doi: 10.1177/1742395317753884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matthias M.S., Bair M.J., Ofner S., et al. Peer support for self-management of chronic pain: the evaluation of a peer coach-led intervention to improve pain symptoms (ECLIPSE) trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(12):3525–3533. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06007-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahola Kohut S., Stinson J.N., Ruskin D., et al. iPeer2Peer program: a pilot feasibility study in adolescents with chronic pain. Pain. 2016;157(5):1146–1155. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stinson J., Ahola Kohut S., Forgeron P., et al. The iPeer2Peer program: a pilot randomized controlled trial in adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr Rheumatol. 2016;14(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12969-016-0108-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahola Kohut S., Stinson J., Forgeron P., Luca S., Harris L. Been there, done that: the experience of acting as a young adult mentor to adolescents living with chronic illness. J Pediatr Psychol. 2017;42(9):962–969. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsx062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zelikovsky N., Petrongolo J. Utilizing peer mentors for adolescents with chronic health conditions: potential benefits and complications. Pediatr Transplant. 2013;17(7):589–591. doi: 10.1111/petr.12145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McColl L.D., Rideout P.E., Parmar T.N., Abba-Aji A. Peer support intervention through mobile application: an integrative literature review and future directions. Can Psychol. 2014;55(4):250–257. doi: 10.1037/a0038095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stinson J., Ahola Kohut S., Forgeron P., et al. The iPeer2Peer program: a pilot randomized controlled trial in adolescents with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2016;14(1) doi: 10.1186/s12969-016-0108-2. 48-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahola Kohut S., Stinson J., van Wyk M., Giosa L., Luca S. Systematic review of peer support interventions for adolescents with chronic illness. Int J Child Adolesc Health. 2014;7(3):183. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahola Kohut S., LeBlanc C., O'Leary K., et al. The internet as a source of support for youth with chronic conditions: a qualitative study. Child: care Health Dev. 2018;44(2):212–220. doi: 10.1111/cch.12535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klassen A., Grant C., Barr R., et al. Development and validation of a generic scale for use in transition programs to measure self-management skills in adolescents with chronic health conditions: the TRANSITION-Q. Child: Care Health Dev. 2014;41(1):547–558. doi: 10.1111/cch.12207. 09/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Izaguirre M.R., Keefer L. Development of a self-efficacy scale for adolescents and young adults with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;59(1):29–32. doi: 10.1097/mpg.0000000000000357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith B.W., Dalen J., Wiggins K., Tooley E., Christopher P., Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med. 2008;15(3):194–200. doi: 10.1080/10705500802222972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ebesutani C., Reise S.P., Chorpita B.F., et al. The revised child anxiety and depression scale-short version: scale reduction via exploratory bifactor modeling of the broad anxiety factor. Psychol Assess. 2012;24(4):833–845. doi: 10.1037/a0027283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeWalt D.A., Thissen D., Stucky B.D., et al. PROMIS pediatric peer relationships scale: development of a peer relationships item bank as part of social health measurement. Health Psychol. 2013;32(10):1093–1103. doi: 10.1037/a0032670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Otley A., Smith C., Nicholas D., et al. The IMPACT questionnaire: a valid measure of health-related quality of life in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35(4):557–563. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200210000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Drennan J. Cognitive interviewing: verbal data in the design and pretesting of questionnaires. J Adv Nurs. 2003;42(1):57–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4 (R package version 1.0–6). 2004. 〈https://cran.rproject.org/web/packages/lme4/index.html〉.

- 44.R. A language and environment for statistical computing. 2018. 〈https://www.R-project.org/〉.

- 45.Braun V., Clarke V. SAGE Publications ltd; 2022. Thematic analysis: A practical guide. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Killackey T., Kohut S.A., Morgan C., et al. Virtual peer-to-peer mentoring for adolescents with congenital heart disease: an implementation study. Can J Cardiol. 2022;38(10):S227–S228. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2022.08.220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lyons N., Cooper C., Lloyd-Evans B. A systematic review and meta-analysis of group peer support interventions for people experiencing mental health conditions. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):1–315. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03321-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baldwin S.A., Berkeljon A., Atkins D.C., Olsen J.A., Nielsen S.L. Rates of change in naturalistic psychotherapy: contrasting dose-effect and good-enough level models of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(2):203–211. doi: 10.1037/a0015235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carey T.A., Stiles W.B. Some problems with randomized controlled trials and some viable alternatives. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2016;23(1):87–95. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ahola Kohut S., Stinson J., Forgeron P., van Wyk M., Harris L., Luca S. A qualitative content analysis of peer mentoring video calls in adolescents with chronic illness. J Health Psychol. 2018;23(6):788–799. doi: 10.1177/1359105316669877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McKay R.C., Giroux E.E., Baxter K.L., et al. Investigating the peer Mentor-Mentee relationship: characterizing peer mentorship conversations between people with spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2023;45(6):962–973. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2022.2046184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wanstall E.A., Ahola Kohut S. Linguistic predictors of the mentor-mentee relationship in a peer support program for adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Child'S Health care. 2023:1–21. doi: 10.1080/02739615.2023.2272954. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sweet S.N., Hennig L., Shi Z., et al. Outcomes of peer mentorship for people living with spinal cord injury: perspectives from members of Canadian community-based SCI organizations. Spinal Cord. 2021;59(12):1301–1308. doi: 10.1038/s41393-021-00725-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.MacCallum J., Beltman S., Coffey A., Cooper T. Taking care of youth mentoring relationships: red flags, repair, and respectful resolution. Mentor Tutor. 2017;25(3):250–271. doi: 10.1080/13611267.2017.1364799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fisher E.B., Ayala G.X., Ibarra L., et al. Contributions of peer support to health, health care, and prevention: papers from peers for progress. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13 1(_1):S2–S8. doi: 10.1370/afm.1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.MacDonald S., Heisler C., Mathias H., et al. Stakeholder perspectives on access to IBD care: proceedings from a national IBD access summit. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2022;5(4):153–160. doi: 10.1093/jcag/gwab048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dave S., Bugwadia A., Kohut S.A., Reed S., Shapiro M., Michel H.K. Peer support interventions for young adults with inflammatory bowel diseases. Health Care Transit. 2023;1 doi: 10.1016/j.hctj.2023.100018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anthony S.J., Lin, J., Selkirk, E.K., Liang, M., Ajmera, F., Seifert-Hansen, M., Urschel, S., Soto, S., Stinson, J., Boucher, S., Gold, A., & Ahola Kohut, S. The iPeer2Peer mentorship program for adolescent thoracic transplant recipients: An implementation-effectiveness evaluation. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. Under Review; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Canada CsaC. Gutsy Support. 〈https://crohnsandcolitis.ca/Support-for-You/Gutsy-support#:~:text=ONLINE%20Peer%20Support,-%EE%88%B6%20SUPPORT%20FOR&text=Applicants%20to%20the%20program%20are〉.

- 60.Graham I.D., Logan J., Harrison M.B., et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(1):13–24. doi: 10.1002/chp.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cheek C., Fleming T., Lucassen M.F., et al. Integrating Health Behavior Theory and Design Elements in Serious Games. JMIR Ment Health. 2015;2(2) doi: 10.2196/mental.4133. e11-e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jong S.T., Stevenson R., Winpenny E.M., Corder K., van Sluijs E.M.F. Recruitment and retention into longitudinal health research from an adolescent perspective: a qualitative study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2023;23(1) doi: 10.1186/s12874-022-01802-7. 16-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.King A.J., Simmons M.B. A systematic review of the attributes and outcomes of peer work and guidelines for reporting studies of peer interventions. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(9):961–977. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201700564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.