Abstract

Objectives

To explore the short- and long-term effects of glycemic management—through glycemic treatment and blood glucose monitoring (BGM)—on stroke recurrence and mortality specifically in patients experiencing a first-ever ischemic stroke (FIS) with hyperglycemia (FISHG) who have not previously been diagnosed with diabetes mellitus (DM).

Methods

We gathered data on patients who were registered on Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database from 2000 to 2015. We one-fold propensity-score-matched (by sex, age, and index date) 207,054 patients into 3 cohorts: those with FIS (1) without hyperglycemia, (2) hyperglycemia without glycemic treatment, and (3) hyperglycemia with glycemic treatment. We used Cox proportional hazard regression to evaluate the short- (within 1 year after FIS) and long-term (9.3 ± 8.6 years after FIS) prognostic effects of glycemic management on stroke recurrence and mortality of FISHG.

Results

Stroke recurrence and mortality were significantly more likely in the patients with FISHG than their counterparts without hyperglycemia (p < 0.05). Under glycemic treatment, patients with FISHG demonstrated lower risk of mortality at every follow-up than those without (p < 0.001) but were not less likely to have stroke recurrence (p > 0.05). Integrating BGM with glycemic treatment in the FISHG cohort significantly reduced the risk of stroke recurrence compared to patients receiving only glycemic treatment at 1-month, 3-month, 6-month, and 1-year post-stroke follow-ups (adjusted hazard ratios = 0.84, 0.90, 0.88, and 0.92, respectively); additionally, this approach significantly decreased mortality risk at each post-stroke follow-up period (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

BGM combined with glycemic treatment significantly improves prognosis in patients with FISHG who have not been previously diagnosed with DM, reducing the risks of stroke recurrence and mortality.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13098-024-01542-2.

Keywords: First-ever ischemic stroke, Hyperglycemia, Glycemic treatment, Blood glucose monitoring, Mortality, Stroke recurrence

Introduction

Ischemic stroke, or central nervous system infarction, disrupts brain blood supply, leading to potential cell death and significant neurological deficits [1]. Patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) often face deteriorating cognitive, autonomic, and executive functions [1, 2]. Stroke recurrence is frequent and increases over time, with rates from 5.4% to 10.4% within one year and from 12.9% to 14.2% within ten years post-stroke [3, 4], significantly impacting mortality and functional disability [5].

Hyperglycemia, present in 40–60% of AIS cases, responds to the acute stress of brain damage and varies across patients with no diabetes, established, or newly diagnosed diabetes, leading to what is known as poststroke hyperglycemia [6, 7]. Hyperglycemia initially serves as an essential survival response that typically subsides shortly after an AIS [8]. However, persistent hyperglycemia beyond the acute phase significantly exacerbates morbidity and mortality risks [9–11]. While hyperglycemia is generally defined as a blood glucose level exceeding 108 mg/dL, the specific threshold for clinical intervention may vary depending on the healthcare setting and the patient's condition [12, 13].

Hyperglycemia within 48 h of AIS predicts stroke recurrence [14]. The acute-to-chronic glycemic ratio, defined as the admission glucose level divided by chronic glucose levels, has been shown to correlate positively with poor prognosis and increased mortality at a 3-month follow-up in AIS [15]. Additionally, a two-year cohort study in China identified diabetes mellitus (DM) as a risk factor for recurrence after the first ischemic stroke [16], and a systematic review indicated that patients with poststroke hyperglycemia have a higher relative risk of in-hospital or 30-day mortality compared to those with normoglycemia—1.30 times higher for those previously diagnosed with DM and 3.07 times higher for those without [9]. Both admission hyperglycemia and the combination of hyperglycemia with elevated glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels are risk factors for short-term mortality (3 months to 1-year post-stroke) in AIS patients, particularly those without prior diabetes [17–20]. Although poststroke hyperglycemia is a modifiable risk factor for brain damage [2], and glucose-lowering therapies can reduce such risks [21], tight glycemic control has not significantly improved survival or functional outcomes and may heighten hypoglycemia risk [22, 23]. Current ischemic stroke management guidelines emphasize glucose monitoring but do not specify glucose level thresholds for intervention or recommend specific insulin treatment regimens, nor do they recommend a specific frequency for blood glucose monitoring (BGM) [2, 24].

Glycemic management practices vary widely, often adopting a conservative approach due to the risks of iatrogenic hypoglycemia, ambiguous benefits, and potential overuse of healthcare resources, which vary by the robustness of each country's healthcare system [25]. Frequently, hyperglycemia remains unmanaged, and its control in AIS continues to be debated [24]. Despite these controversies, there is a scarcity of large-scale longitudinal studies investigating the comprehensive effects of glycemic management, including both glycemic treatment and BGM, on AIS outcomes. This study leverages the Taiwanese National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) to examine both the short- and long-term prognostic impacts of managing glycemia during the acute hospitalization phase on stroke recurrence and mortality among patients experiencing their first-ever ischemic stroke (FIS) with hyperglycemia (FISHG), who had not been previously diagnosed with DM.

Methods

Data sources

This retrospective cohort study used a randomized sample of 2 million people registered in Taiwan’s NHIRD between 2000 and 2015. Since the inception of Taiwan's single-payer National Health Insurance in 1995, the NHIRD has encompassed about 99% of Taiwan’s 23.74 million population and contracts with 97% of its medical facilities. The database includes comprehensive records such as medical facility registries, medication prescriptions, and data on inpatient, outpatient, and emergency visits [26], making it highly accurate and valid for ischemic stroke research [27]. All methods were carried out following relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s). The Research Ethics Committee of the Tri-Service General Hospital of the National Defense Medical Center approved this study (TSGHIRB No. B-110-32).

Study participants

The participants' data were extracted from the NHIRD using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. Between 2000 and 2015, patients aged ≥ 20 years who were diagnosed for the first time with ischemic stroke, identified by ICD-9-CM codes 433 or 434, were enrolled on what is defined as the index date. This index date was crucial for ensuring the exclusion of any individuals with prior diagnoses of ischemic stroke under the same codes. The FIS during the study period was defined as the index stroke. To ensure all cases were first-ever incidents, patients with any stroke history from 1997 to 1999 were excluded, utilizing this interval as a wash-out period to avoid carry-over bias from pre-existing strokes [28]. Hyperglycemia in acute stroke was identified using ICD-9-CM code 790.29 for abnormal glucose and prediabetes, and an initial diagnosis of DM, denoted by ICD-9-CM code 250, recorded on the index date. Additionally, patients with FIS who had a history of DM (ICD-9-CM code 250) prior to the index date were excluded.

Patients were propensity-score-matched based on sex, age, and index date using a logistic regression model. The matching was conducted using the nearest neighbor method, characterized by a random matching order, replacement, no caliper, and a 1:1 ratio. The tolerance threshold for the matching score was set at 0.2. Following matching, patients were categorized into three cohorts: (a) FIS without hyperglycemia (FISw/oHG); (b) FIS with hyperglycemia but without glycemic treatment during the acute stroke phase while hospitalized (FISHGw/oGT); and (c) FIS with hyperglycemia and receiving glycemic treatment during the acute stroke phase while hospitalized (FISHGw/GT).

In Taiwan’s NHIRD, both glycemic treatment and glucose monitoring during the acute hospitalization phase for ischemic stroke patients with hyperglycemia are coded specially. For this study, glycemic treatment is defined as the administration of any glucose-lowering medication, which includes Continuous Insulin Treatment, Insulin Treatment on Demand, and Oral Anti-Diabetic Treatment. These treatments are identified in the NHIRD by specific medication codes: A10AB-180, A10AC-136, A10AD-183, A10AE-54, A10BA-977, A10BB-1590, A10BF-354, A10BG-344, and A10BX-306. Additionally, BGM involves regular checking of blood glucose using a specialized meter, a crucial practice for managing glucose levels during hospitalization for a stroke. BGM is tracked in the NHIRD using the code 09005C, recorded at the time of the patient's first ischemic stroke hospitalization.

Covariates

Covariates included in the multivariable model were demographic factors, including sex, age, insurance premium; comorbidities identified by specific ICD-9 codes, including hypertension (401–405), ischemic heart disease (410–414), congestive heart failure (428), renal diseases (580–589), cancer (140–209); as well ad season, geographical area of residence (north, center, south, or east of Taiwan), urbanization level of the residence, and level of care (medical center, regional hospital, or local hospital). These covariates were adjusted for in the multivariable analysis to ensure a comprehensive evaluation of outcomes.

Outcome measures

Stroke recurrence and mortality were evaluated as outcome measures during short- and long-term follow-ups. Stroke recurrence was defined as rehospitalization with a primary diagnosis of ischemic stroke (ICD-9-CM code 433 or 434) after the index date. In the NHIRD, the mortality status of patients was coded as "4" if they died during the hospitalization, or "A" if they were in the acute terminal stage upon discharge. All enrolled patients were followed up for a short-term period of one year from the index date, and over the long term until the study endpoint, defined as death, withdrawal from the NHI program, or the end of 2015, whichever came first.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as means with standard deviation, and categorical data are presented as frequencies with percentages. The chi-square and t-test were used to compare categorical and continuous variables between cohorts. We employed multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression to assess the risks of stroke recurrence and mortality within one year after the index date and up to the study endpoint across cohorts. Results are reported as unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Differences in the risks of stroke recurrence and mortality among cohorts were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method with the log-rank test. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the impact of including patients newly diagnosed with diabetes during their hospitalization on stroke outcomes. This involved comparing patients with abnormal glucose levels (ICD-9-CM code 790.29) to those diagnosed with diabetes (ICD-9-CM code 250) during their FIS hospital stay. These analyses helped identify any confounding effects of undiagnosed diabetes on our results. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all two-tailed tests. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study population

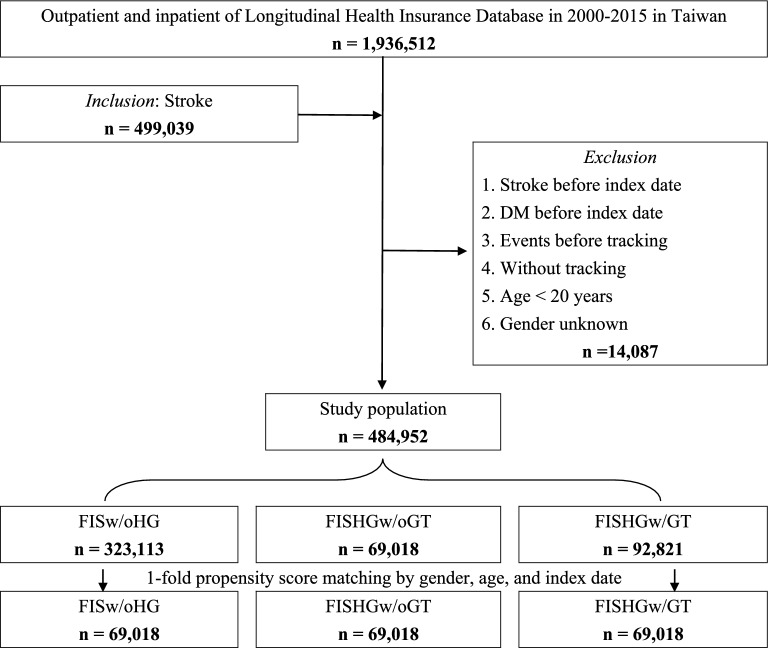

In total, 484,952 patients with FIS met the study’s inclusion criteria, of which 161,839 (33.4%) had hyperglycemia. Within this FISHG group, 69,018 (42.6%) did not receive glycemic treatment, while 92,821 (57.4%) received glycemic treatments during the acute stroke phase. Following one-fold propensity score matching, 207,054 patients were categorized into three cohorts: FISw/oHG, FISHGw/oGT, and FISHGw/GT (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of sample selection from the National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan (matched). FIS first-ever ischemic stroke, FISw/oHG FIS without hyperglycemia, FISHGw/oGT FIS wih hyperglycemia without glycemic treatment, FISHGw/GT FIS with hyperglycemia with glycemic treatment

Following propensity score matching based on sex, age, and index date, the matched sample included 58.45% males with a mean age of 56.5 ± 10.3 years (Table 1), which is considerably younger than the broader, unmatched first-ever stroke population (mean age 67.1 ± 16.1 years). BGM was performed in 63,672 (92.25%) patients within the FISHGw/GT cohort and 6213 (9.00%) patients within the FISHGw/oGT cohort (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants at baseline

| Cohorts Variables |

Total | FISw/oHG | FISHGw/oGT | FISHGw/GT | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Total | 207,054 | 69,018 | 69,018 | 69,018 | |

| Gender | 0.999† | ||||

| Male | 121,029 (58.45) | 40,343 (58.45) | 40,343 (58.45) | 40,343 (58.45) | |

| Female | 86,025 (41.55) | 28,675 (41.55) | 28,675 (41.55) | 28,675 (41.55) | |

| Age (years, M ± SD) | 56.6 ± 10.3 | 56.6 ± 10.3 | 56.5 ± 10.3 | 56.6 ± 10.3 | 0.782# |

| Insured premium (NT$) | < 0.001† | ||||

| < 18,000 | 64,422 (31.11) | 21,875 (31.69) | 21,472 (31.11) | 21,075 (30.54) | |

| 18,000–34,999 | 121,211 (58.54) | 40,210 (58.26) | 40,567 (58.78) | 40,434 (58.58) | |

| ≥ 35,000 | 21,421 (0.35) | 6933 (10.05) | 6979 (10.11) | 7509 (10.88) | |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Hypertension | 87,983 (42.49) | 20,211 (29.28) | 32,376 (46.91) | 35,396 (51.29) | < 0.001† |

| Ischemic heart disease | 29,136 (14.07) | 9076 (13.15) | 10,165 (14.73) | 9895 (14.34) | < 0.001† |

| Congestive heart failure | 11,845 (5.72) | 3392 (4.91) | 4012 (5.81) | 4441 (6.43) | < 0.001† |

| Renal diseases | 35,714 (17.25) | 10,256 (14.86) | 13,160 (19.07) | 12,298 (17.82) | < 0.001† |

| Cancer | 34,839 (16.83) | 10,023 (14.52) | 11,675 (16.92) | 13,141 (19.04) | < 0.001† |

| Season | 0.999† | ||||

| Spring (Mar–May) | 52,737 (25.47) | 17,579 (25.47) | 17,579 (25.47) | 17,579 (25.47) | |

| Summer (Jun–Aug) | 52,557 (25.38) | 17,519 (25.38) | 17,519 (25.38) | 17,519 (25.38) | |

| Autumn (Sep–Nov) | 50,988 (24.63) | 16,996 (24.63) | 16,996 (24.63) | 16,996 (24.63) | |

| Winter (Dec–Feb) | 50,772 (24.52) | 16,924 (24.52) | 16,924 (24.52) | 16,924 (24.52) | |

| Geographical area of residence | < 0.001† | ||||

| Northern Taiwan | 74,706 (36.08) | 25,281 (36.63) | 23,338 (33.81) | 26,087 (37.80) | |

| MiddleTaiwan | 62,933 (30.39) | 21,317 (30.89) | 19,881 (28.81) | 21,735 (31.49) | |

| Southern Taiwan | 58,202 (28.11) | 18,346 (26.58) | 22,537 (32.65) | 17,319 (25.09) | |

| Eastern Taiwan | 10,544 (5.09) | 3897 (5.65) | 2962 (4.29) | 3685 (5.34) | |

| Outlets islands | 669 (0.32) | 177 (0.26) | 300 (0.43) | 192 (0.28) | |

| Urbanization level of the residence | < 0.001† | ||||

| 1 (The highest) | 66,091 (31.92) | 22,132 (32.07) | 21,406 (31.02) | 22,553 (32.68) | |

| 2 | 89,934 (43.44) | 30,270 (43.86) | 28,297 (41.00) | 31,367 (45.45) | |

| 3 | 14,565 (7.03) | 4586 (6.64) | 5593 (8.10) | 4386 (6.35) | |

| 4 (The lowest) | 36,464 (17.61) | 12,030 (17.43) | 13,722 (19.88) | 10,712 (15.52) | |

| Level of care | < 0.001† | ||||

| Medical center | 73,230 (35.37) | 25,259 (36.60) | 21,088 (30.55) | 26,883 (38.95) | |

| Regional hospital | 95,349 (46.05) | 30,641 (44.40) | 33,644 (48.75) | 31,064 (45.01) | |

| Local hospital | 38,475 (18.58) | 13,118 (19.01) | 14,286 (20.70) | 11,071 (16.04) | |

| BGM | < 0.001† | ||||

| Yes | 69,885 (50.63) | 0 (0) | 6213 (9.00) | 63,672 (92.25) | |

| No | 68,151 (49.37) | 0 (0) | 62,805 (91.00) | 5,346 (7.75) |

†Chi-square test; #One-way ANOVA; BGM blood glucose monitoring

Comparison of stroke recurrence and mortality among the FISw/oHG, FISHGw/oGT, and FISHGw/GT Cohorts

Within 1 year of tracking, stroke recurrence was significantly more common in the FISHGw/oGT and FISHGw/GT cohorts than in the FISw/oHG cohort (p < 0.05). However, at the 3-month post-stroke follow-up, the incidence of stroke recurrence in the FISHGw/GT cohort was not significantly different from that in the FISw/oHG cohort (p = 0.12; Table 2). The FISHGw/oGT and FISHGw/GT cohorts had a substantially higher mortality rate than the FISw/oHG cohort within one year of tracking (p < 0.05). Long-term outcomes assessed at the study endpoint follow-up (9.3 ± 8.6 years) through Cox regression analysis revealed that both the FISHGw/oGT and FISHGw/GT cohorts had higher risks of stroke recurrence and mortality compared to the FISw/oHG cohort, with aHR of 1.33 and 1.15 for stroke recurrence, and 1.343and 1.10 for mortality, respectively (p < 0.001; Table 2). Despite these findings, the FISHGw/GT cohort did not significantly reduce stroke recurrence at either short- or long-term follow-ups compared to the FISHGw/oGT cohort. However, it significantly reduced mortality at all follow-up periods, except one month after the acute stroke (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Cox regression analysis for the risks of stroke recurrence and mortality of the FISw/oHG, FISHGw/oGT, and FISHGw/GT cohorts within 1 year and at the endpoint

| Follow-ups | Cohorts | Stroke recurrence | Mortality | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | Crude HR | 95% CI | p-value | aHR | 95% CI | p-value | Events | Crude HR | 95% CI | p-value | aHR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| 1-month | FISw/oHG | 834 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 295 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| FISHGw/oGT | 1341 | 1.84 | 1.55–2.09 | < 0.001 | 1.77 | 1.50–2.01 | < 0.001 | 646 | 1.59 | 1.24–1.97 | < 0.001 | 1.51 | 1.17–1.87 | < 0.001 | |

| FISHGw/GT | 1128 | 1.46 | 1.20–1.71 | < 0.001 | 1.36 | 1.17–1.62 | < 0.001 | 578 | 1.48 | 1.12–1.83 | < 0.001 | 1.38 | 1.05–1.71 | 0.001 | |

| 3-month | FISw/oHG | 1526 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 755 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| FISHGw/oGT | 1853 | 1.42 | 1.09–1.73 | < 0.001 | 1.33 | 1.03–1.62 | 0.02 | 1467 | 2.14 | 1.94–2.45 | < 0.001 | 2.07 | 1.84–2.29 | < 0.001 | |

| FISHGw/GT | 1732 | 1.21 | 0.98–1.52 | 0.08 | 1.13 | 0.87–1.42 | 0.15 | 1077 | 1.50† | 1.29–1.78 | < 0.001 | 1.41† | 1.20–1.61 | < 0.001 | |

| 6-month | FISw/oHG | 1970 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1336 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| FISHGw/oGT | 2280 | 1.43 | 1.10–1.77 | < 0.001 | 1.38 | 1.04–1.71 | 0.01 | 2265 | 1.88 | 1.62–2.20 | < 0.001 | 1.81 | 1.52–2.10 | < 0.001 | |

| FISHGw/GT | 2119 | 1.35 | 1.06–1.68 | < 0.001 | 1.30 | 1.01–1.62 | 0.04 | 1509 | 1.29† | 1.10–1.57 | < 0.001 | 1.21† | 1.01–1.45 | 0.03 | |

| 1-year | FISw/oHG | 2462 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2209 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| FISHGw/oGT | 2797 | 1.45 | 1.21–1.70 | < 0.001 | 1.32 | 1.17–1.60 | < 0.001 | 3442 | 1.74 | 1.35–2.16 | < 0.001 | 1.63 | 1.29–2.04 | < 0.001 | |

| FISHGw/GT | 2561 | 1.33 | 1.10–1.62 | < 0.001 | 1.23 | 1.05–1.53 | < 0.001 | 2313 | 1.39† | 1.11–1.72 | < 0.001 | 1.33† | 1.05–1.62 | < 0.001 | |

| Endpoint | FISw/oHG | 5960 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 11,072 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| FISHGw/oGT | 6426 | 1.41 | 1.36–1.49 | < 0.001 | 1.33 | 1.29–1.38 | < 0.001 | 14,432 | 1.42 | 1.31–1.48 | < 0.001 | 1.33 | 1.29–1.35 | < 0.001 | |

| FISHGw/GT | 6036 | 1.20 | 1.16–1.27 | < 0.001 | 1.15 | 1.11–1.20 | < 0.001 | 11,482 | 1.12† | 1.09–120 | < 0.001 | 1.10† | 1.07–1.13 | < 0.001 | |

The covariates gender, age, insured premium, comorbidities, season, geographical area of residence, urbanization level of the residence, and level of care were included in the multivariable model for adjustment. FIS first-ever ischemic stroke, FISw/oHG FIS without hyperglycemia, FISHGw/oGT FIS with hyperglycemia without glycemic treatment, FISHGw/GT FIS with hyperglycemia with glycemic treatment, aHR adjusted hazard ratio, CI confidence interval;† = p < 0.001 as comparison of hazard ratio between FISHGw/oGT and FISHGw/GT cohorts; Endpoint = from the index date until death, withdrawal from the NHI program, or the end of 2015, whichever occurred first

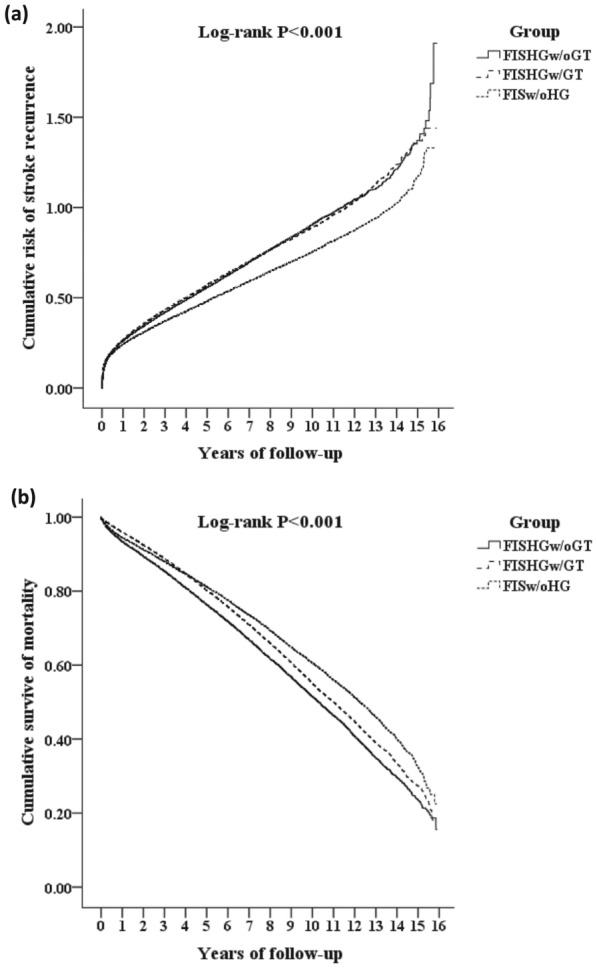

Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that the FISw/oHG cohort had the lowest cumulative risks of stroke recurrence and mortality during the first-year post-stroke, a trend that persisted until the end of the follow-up period (log‐rank test; p < 0.001; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier analysis comparing the cumulative incidence of a stroke recurrence and b mortality among the FISw/oHG, FISHGw/oGT, and FISHGw/GT cohorts. FIS first-ever ischemic stroke, FISw/oHG FIS without hyperglycemia, FISHGw/oGT = FIS with hyperglycemia without glycemic treatment, FISHGw/GT FIS with hyperglycemia with glycemic treatment

Short- and long-term prognostic effects of glycemic treatment and BGM on stroke recurrence in FISHG patients

FISHGw/GT patients without BGM did not show a lower stroke recurrence compared to FISHGw/oGT without BGM at either short- or long-term follow-up periods. However, data indicate that integrating BGM for the FISHGw/GT cohort during the acute stroke phase resulted in a lower risk of stroke reoccurrence than in FISHGw/oGT patients without BGM at the 1-month, 3-month, 6-month, and 1-year-post-stroke follow-ups (aHR = 0.77, 0.88, 0.83, and 0.85, respectively; p < 0.05), though this reduction did not persist until the end of the study (p > 0.05, Table 3). Additionally, we found that integrating BGM with glycemic treatment significantly reduced stroke recurrence in the FISHGw/GT cohort compared to those without BGM at the 1-month, 3-month, 6-month, and 1-year-post-stroke follow-ups (aHR = 0.84, 0.90, 0.88, and 0.92, respectively; p < 0.05). However, this reduction was not evident at the study endpoint (Table 4).

Table 3.

Short- and long-term prognostic effect of the glycemic treatment and blood glucose monitoring on stroke recurrence and mortality in FISHG patients

| Follow-ups | Cohorts | Stroke recurrence | Mortality | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | Crude HR | 95% CI | p-value | aHR | 95% CI | p-value | Events | Crude HR | 95% CI | p-value | aHR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| 1-month | FISHGw/oGT without BGM | 1253 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 603 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| FISHGw/oGT with BGM | 88 | 0.69 | 0.61–0.77 | < 0.001 | 0.73 | 0.64–0.81 | < 0.001 | 43 | 0.70 | 0.63–0.71 | < 0.001 | 0.74 | 0.68–0.79 | < 0.001 | |

| FISHGw/GT without BGM | 105 | 0.89 | 0.79–0.99 | 0.04 | 0.94 | 0.83–1.05 | 0.07 | 55 | 0.98 | 0.89–1.02 | 0.07 | 1.00 | 0.94–1.08 | 0.30 | |

| FISHGw/GT with BGM | 1023 | 0.73† | 0.64–0.81 | < 0.001 | 0.77† | 0.69–0.85 | < 0.001 | 523 | 0.77† | 0.70–0.83 | < 0.001 | 0.81† | 0.76–0.89 | < 0.001 | |

| 3-month | FISHGw/oGT without BGM | 1728 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1382 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| FISHGw/oGT with BGM | 125 | 0.69 | 0.60–0.81 | < 0.001 | 0.74 | 0.65–0.86 | < 0.001 | 85 | 0.63 | 0.49–0.70 | < 0.001 | 0.65 | 0.53–0.74 | < 0.001 | |

| FISHGw/GT without BGM | 148 | 0.92 | 0.81–1.00 | 0.05 | 0.97 | 0.86–1.09 | 0.10 | 95 | 0.75 | 0.66–0.87 | < 0.001 | 0.80 | 0.71–0.92 | < 0.001 | |

| FISHGw/GT with BGM | 1584 | 0.80† | 0.70–0.91 | < 0.001 | 0.88 | 0.75–0.96 | 0.04 | 982 | 0.66† | 0.50–0.76 | < 0.001 | 0.69† | 0.55–0.80 | < 0.001 | |

| 6-month | FISHGw/oGT without BGM | 2088 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2130 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| FISHGw/oGT with BGM | 192 | 0.90 | 0.78–1.02 | 0.06 | 0.95 | 0.83–1.10 | 0.12 | 135 | 0.60 | 0.49–0.76 | < 0.001 | 0.67 | 0.55–0.84 | < 0.001 | |

| FISHGw/GT without BGM | 177 | 0.93 | 0.80–1.06 | 0.09 | 0.98 | 0.86–1.13 | 0.19 | 164 | 0.81 | 0.71–0.90 | < 0.001 | 0.89 | 0.77–0.96 | 0.01 | |

| FISHGw/GT with BGM | 1942 | 0.77† | 0.65–0.89 | < 0.001 | 0.83 | 0.71–0.95 | 0.01 | 1345 | 0.55† | 0.44–0.92 | < 0.001 | 0.62† | 0.51–0.69 | < 0.001 | |

| 1-year | FISHGw/oGT without BGM | 2565 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3244 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| FISHGw/oGT with BGM | 232 | 0.82 | 0.67–0.92 | < 0.001 | 0.90 | 0.74–0.98 | 0.03 | 198 | 0.65 | 0.55–0.77 | < 0.001 | 0.72 | 0.61–0.83 | < 0.001 | |

| FISHGw/GT without BGM | 216 | 0.85 | 0.73–0.97 | 0.03 | 0.93 | 0.82–1.06 | 0.10 | 190 | 0.69 | 0.57–0.79 | < 0.001 | 0.75 | 0.63–0.86 | < 0.001 | |

| FISHGw/GT with BGM | 2345 | 0.73 | 0.61–0.89 | < 0.001 | 0.85 | 0.71–0.93 | < 0.001 | 2123 | 0.62 | 0.53–0.74 | < 0.001 | 0.69 | 0.59–0.81 | < 0.001 | |

| Endpoint | FISHGw/oGT without BGM | 5864 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 13,421 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| FISHGw/oGT with BGM | 562 | 0.91 | 0.83–1.08 | 0.74 | 0.98 | 0.88–1.18 | 0.89 | 1011 | 0.81 | 0.75–0.92 | < 0.001 | 0.88 | 0.81–0.99 | 0.04 | |

| FISHGw/GT without BGM | 514 | 0.92 | 0.84–1.11 | 0.77 | 0.99 | 0.89–1.20 | 0.93 | 1181 | 0.77 | 0.63–0.86 | < 0.001 | 0.82 | 0.74–0.95 | 0.01 | |

| FISHGw/GT with BGM | 5522 | 0.90 | 0.79–1.05 | 0.71 | 0.96 | 0.85–1.11 | 0.84 | 10,301 | 0.68 | 0.54–0.79 | < 0.001 | 0.74 | 0.63–0.88 | < 0.001 | |

The covariates gender, age, insured premium, comorbidities, season, geographical area of residence, urbanization level of the residence, and level of care were included in the multivariable model for adjustment. FIS first-ever ischemic stroke, FISHG FIS patients with hyperglycemia, FISHGw/oGT FIS with hyperglycemia without glycemic treatment, FISHGw/GT FIS with hyperglycemia with glycemic treatment, BGM blood glucose monitoring, aHR adjusted hazard ratio, CI confidence interval; † = p < 0.001 as comparison of hazard ratio between FISHGw/GT without BGM and FISHGw/GT with BGM cohorts; Endpoint = from the index date until death, withdrawal from the NHI program, or the end of 2015, whichever occurred first

Table 4.

Short- and long-term prognostic effect of integrating blood glucose monitoring on stroke recurrence and mortality in FISHGw/GT patients

| Follow-ups | Cohorts | Stroke recurrence | Mortality | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | Crude HR | 95% CI | p-value | aHR | 95% CI | p-value | Events | Crude HR | 95% CI | p-value | aHR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| 1-month | FISHGw/GT without BGM | 105 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 55 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| FISHGw/GT with BGM | 1023 | 0.82 | 0.73–0.89 | < 0.001 | 0.84 | 0.75–0.91 | < 0.001 | 523 | 0.79 | 0.68–0.87 | < 0.001 | 0.82 | 0.70–0.89 | < 0.001 | |

| 3-month | FISHGw/GT without BGM | 148 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 95 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| FISHGw/GT with BGM | 1584 | 0.87 | 0.79–0.93 | < 0.001 | 0.90 | 0.82–0.97 | 0.03 | 982 | 0.84 | 0.73–0.89 | < 0.001 | 0.86 | 0.76–0.92 | < 0.001 | |

| 6-month | FISHGw/GT without BGM | 177 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 164 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| FISHGw/GT with BGM | 1942 | 0.84 | 0.77–0.90 | < 0.001 | 0.88 | 0.80–0.95 | 0.01 | 1345 | 0.74 | 0.65–0.83 | < 0.001 | 0.77 | 0.68–0.80 | < 0.001 | |

| 1-year | FISHGw/GT without BGM | 216 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 190 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| FISHGw/GT with BGM | 2345 | 0.88 | 0.80–0.95 | 0.001 | 0.92 | 0.85–0.99 | 0.04 | 2123 | 0.87 | 0.76–0.94 | 0.01 | 0.89 | 0.78–0.97 | 0.03 | |

| Endpoint | FISHGw/GT without BGM | 514 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1181 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| FISHGw/GT with BGM | 5522 | 0.95 | 0.89–1.04 | 0.06 | 0.98 | 0.90–1.07 | 0.09 | 10,301 | 0.88 | 0.78–0.95 | 0.01 | 0.90 | 0.79–0.98 | 0.02 | |

The covariates gender, age, insured premium, comorbidities, season, geographical area of residence, urbanization level of the residence, and level of care were included in the multivariable model for adjustment. FIS first-ever ischemic stroke, FISHG FIS patients with hyperglycemia; FISHGw/GT FIS with hyperglycemia with glycemic treatment, BGM blood glucose monitoring, aHR adjusted hazard ratio, CI confidence interval; Endpoint = from the index date until death, withdrawal from the NHI program, or the end of 2015, whichever occurred first

Short- and long-term prognostic effects of glycemic treatment and BGM on mortality in FISHG patients

Integrating BGM with glycemic management for the FISHGw/GT cohort during the acute stroke phase significantly lreduced mortality at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year post-stroke, and at the end of the study, compared to the FISHGw/oGT cohort without BGM cohort (aHR = 0.81, 0.69, 0.62, 0.69, and 0.74, respectively; p < 0.001; Table 3). Additionally, this integration significantly lowered mortality at each post-stroke follow-up compared to FISHGw/GT patients without BGM (p < 0.05; Table 4).

Sensitivity analyses, detailed in Supplemental Tables 1, 2 and 3, demonstrated that including patients newly diagnosed with diabetes during their hospitalization did not significantly alter the effects of glycemic treatment and BGM on stroke recurrence and mortality. The outcomes for both patient groups—those with abnormal glucose levels and those newly diagnosed with diabetes during their FIS hospital stay—aligned with our primary findings, further confirming the robustness of our data and minimizing concerns about confounding from undiagnosed diabetes.

Discussion

Data from Taiwan's NHIRD revealed that patients experiencing the FIS with hyperglycemia, who had no prior history of DM, had higher risks of both short-term and long-term stroke recurrence and mortality compared to those without hyperglycemia. While glycemic treatment with glucose-lowering therapies during the acute stroke phase reduced the short- and long-term mortality risks, it did not significantly affect stroke recurrence in patients with FISHG. However, our findings suggest that integrating BGM with glycemic treatment during the acute phase of stroke may reduce the risk of stroke recurrence within the first year and decrease mortality rates over both the short and long term for these patients.

In this study, 33.4% of nondiabetic patients with FIS exhibited hyperglycemia, which aligns with a systematic review reporting a prevalence of 8% to 63% in nondiabetic patients with AIS [9, 20, 29]. Patients with FIS with hyperglycemia might present preexisting and unrecognized DM but mainly develop hyperglycemia as a stress reaction to brain damage [9]. This condition, known as stress hyperglycemia, has been linked to increased risks of stroke recurrence and all-cause mortality at the 12-month follow-up in nondiabetic AIS patients [30]. Patients with stroke and newly diagnosed DM, defined by fasting plasma glucose levels ≥ 7.0 mmol/L or 2-h oral glucose tolerance test ≥ 11.1 mmol/L (with/without HbA1c ≥ 6.5%), exhibited higher risks of stroke recurrence, poor functional outcomes, and mortality compared to nondiabetic patients at 3-month and 1-year follow-ups [20, 29]. Consistent with other studies, the present study shows that patients with FIS with hyperglycemia face higher stroke recurrence and mortality compared to those without hyperglycemia.

The mechanisms linking poststroke hyperglycemia to poor stroke outcomes are not fully understood. Poststroke hyperglycemia may result from neurohormonal dysfunction and inflammatory responses to ischemic brain damage [31]. Additionally, a complex interplay among catecholamines, cortisol, and cytokines may elevate hepatic glucose output [32]. Hyperglycemia can worsen stroke outcomes through various neurotoxic effects, including calcium imbalance, accumulation of reactive oxygen species, increased lactic acidosis, reduced nitric oxide, and enhanced inflammatory responses [33]. Insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction cause relative insulin deficiency in hyperglycemia, potentially worsening outcomes for nondiabetic patients with ischemic stroke [34, 35]. These pathophysiological effects can enhance lipid peroxidation, free radical formation, and accumulation of intracellular calcium, which may contribute to cell lysis in the umbra and penumbra regions, thereby exacerbating ischemic injury [18, 36–38]. A magnetic resonance imaging study has demonstrated that hyperglycemia is influenced by the size of the initial brain infarct and its subsequent expansion [39]. This interaction suggests that hyperglycemia may exacerbate infarct growth, with prolonged post-stroke hyperglycemia linked to worsened neuronal damage, disrupted blood–brain barrier function, and increased infarct volume [18, 40] Additionally, acute and chronic hyperglycemia significantly alters cerebral blood flow, influencing computed tomography perfusion (CTP) underestimation error in AIS patients with large vessel occlusion [41]. These findings underscore the critical need to consider glycemic status for accurate CTP interpretation and effective treatment planning in ischemic stroke patients.

In light of the adverse outcomes of patients with poststroke hyperglycemia, guidelines recommend early glucose management to achieve blood glucose levels of 140–180 mg/dL. Additionally, intensive BGM is essential to mitigate further brain damage and improve patient outcomes [2]. Using insulin to control blood glucose level in glycemic treatment can trigger a neuroprotective effect by augmenting astrocytic glycogen phosphorylase [38]. Brain reperfusion after an ischemic stroke may lead to significant reperfusion-induced glycogen accumulation in the ischemic penumbra; this accumulation is strongly associated with the development of ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury, which exacerbates conditions such as glutamate excitotoxicity, calcium overload, free radical formation, and inflammation [42]. Evidence over the past decade underscores insulin's critical role in neuroprotection, particularly through maintaining calcium homeostasis, inhibiting inflammation, reducing free radicals in the heart, and modulating glucose metabolism to prevent ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury [43, 44]. Consequently, insulin treatment emerges as a promising intervention for ischemic stroke, particularly targeting glycogenolysis. However, the effectiveness of such strategies may vary depending on the timing of ischemia, underscoring the need for precise application.

Although early glycemic management may benefit acute stroke, research indicates that intensive insulin therapy or stringent glucose control might not significantly improve functional outcomes or survival. Furthermore, such approaches can lead to adverse hypoglycemic effects [22]. This line of argument suggests that brain injury during acute stroke increases the need for glucose and is vulnerable to glucose deficit [45, 46]. Intensive glucose control aimed at maintaining levels within the normal range could result in brain glycopenia, a metabolic crisis in the ischemic brain, and potentially higher mortality [47]. Therefore, the approach to glycemic treatment during acute stroke remains controversial. Additionally, the emerging challenge of inadequate hyperglycemia management in the acute stroke phase warrants attention. Guidelines recommend combining BGM with glycemic treatment to prevent iatrogenic hypoglycemia during insulin treatment and to maintain safe glucose levels for patients with AIS [2]. This study revealed that more than 92% of FISHGw/GT patients received BGM, while only 9% of the FISHGw/oGT cohort received similar monitoring. A likely explanation for this disparity is that the FISHGw/oGT patients may have exhibited relatively stable blood glucose levels during initial tests, leading clinicians to consider further BGM.

Another study used continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) to assess glucose variability in patients with AIS and discovered that patients with a high blood glucose level (> 180 mg/dL) upon admission were significantly more likely to develop poststroke hyperglycemia than their counterparts [48]. For CGM during the initial 72 h of AIS, the results indicated that a high mean glucose level (≥ 140 mg/dL), a distribution time of blood glucose ≥ 8 mmol/L (144 mg/dL) of blood glucose, and an area under the curve of blood glucose ≥ 8 mmol/L were associated with increased risk of death or dependency three months after AIS [49]. Frequent BGM is indispensable for euglycemic management in patients with AIS and hyperglycemia. Despite its importance, BGM is often conducted sporadically in clinical practice, hindering precise and safe treatment due to insufficient knowledge about the dynamic state of blood glucose. Stroke recurrence risk is highest immediately after an ischemic event, decreasing gradually and stabilizing between six months and one-year post-stroke [50]. This study found that glycemic treatment alone, without concurrent BGM, fails to reduce the risk of stroke recurrence in patients with FIS who have not previously been diagnosed with DM.

To assess the impact of hyperglycemia classification on study outcomes, we conducted sensitivity analyses on patients categorized by hyperglycemia status at FIS hospitalization. These analyses confirmed that the benefits of integrating BGM with glycemic treatment are consistent, regardless of diabetes status at the time of hospitalization. This consistency underscores the need for comprehensive glycemic management strategies that encompass both diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes at stroke onset. Future research should aim to develop targeted interventions that more effectively tailor and refine treatment approaches for this diverse patient population. As anticipated, our study confirmed that integrating BGM with glycemic treatment significantly reduces the risks of stroke recurrence within one year and reduces mortality at each subsequent time point in patients with AIS.

Limitations

This longitudinal cohort study has several limitations. First, due to the data constraints imposed by Taiwan's NHIRD, this study could not determine whether hyperglycemia diagnoses after FIS were based on glucose levels or HbA1c measurements [51]. Instead, hyperglycemia was defined using ICD-9-CM codes. Although these codes may not fully capture all nuances of hyperglycemia in acute stroke patients—potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings—they are extensively validated within the Taiwanese context. Notably, previous studies affirm these codes' high sensitivity and positive predictive value, exceeding 90% [52, 53]. This robust validation supports the reliability of our methodology, ensuring that our analysis of the prognostic effects of glycemic management is based on accurately identified data. Second, the dataset lacks detailed information on the dosages and levels of glycemic treatments and BGM applied. Additionally, the absence of a nationally standardized glucose monitoring protocol in Taiwan introduces variability that could affect the consistency and applicability of our results. These limitations underscore the need for more comprehensive data to support specific clinical recommendations and enhance the robustness of future studies. Third, the study did not differentiate between stroke subtypes or specify the locations of strokes, factors that could significantly influence clinical outcomes. Fourth, our study focused solely on inpatient glycemic management during the acute phase of ischemic stroke and did not account for post-hospitalization treatments. Consequently, the use of antidiabetic medications after discharge was not considered. This limitation restricts the scope of our study and may impact its long-term clinical relevance. Future research should include post-hospitalization treatment to provide a more comprehensive understanding of long-term stroke outcomes. Fifth, the mortality data retrieved from the NHIRD may not completely align with Taiwan’s official death records, potentially affecting the validity of our study outcomes. However, the accuracy of the NHIRD mortality data has been confirmed by another study that cross-compared these records with those from the catastrophic illness registry data files. The findings from this comparison indicated high accuracy and validity of the mortality data27.

Conclusions

Appropriate glycemic management, especially when combining glycemic treatment with intensive BGM, is crucial for the acute care of patients with FIS and hyperglycemia who have not previously been diagnosed with DM. While this study highlights the potential benefits of BGM and glycemic management in reducing the risk of stroke recurrence within one year and improving short- and long-term mortality rates among patients with AIS, it does not determine the optimal glucose threshold for initiating treatment. The risk associated with hyperglycemia during acute stroke is well-recognized; however, the optimal strategy for glycemic treatment and the specific benefits of insulin are still under active debate. Thus, BGM is essential for optimal glycemic management during the acute phase of FIS in patients with hyperglycemia who have not previously been diagnosed with DM.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the National Health Research Institute in Taiwan for providing the insurance claims data.

Author contributions

H.H.Y., W.C.C.,Y.C.H., P.-C.Y., S.H.H., R.J.C., B.-L.W., and Y.J.C wrote the main manuscript text and H.H.Y., Y.J.C., W.C.C., C.C.Y., and C.H.C. prepared Figs. 1 and 2. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a research grant (CMNDMC10806) from the Chi-Mei Medical Center, as well as another research grant (TSGH-B-113025) from the Tri-Service General Hospital in Taiwan.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted according to the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).The Research Ethics Committee of the Tri-Service General Hospital of the National Defense Medical Center (TSGHIRB No. B-110-32) approved this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yu-Ju Chen and Wu-Chien Chien contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Wu-Chien Chien, Email: chienwu@mail.ndmctsgh.edu.tw.

Yu-Ju Chen, Email: judychen37@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Sacco RL, et al. An updated definition of stroke for the 21st century: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44:2064–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powers WJ, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2019;50:e344–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin B, et al. Cumulative risk of stroke recurrence over the last 10 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol Sci. 2021;42:61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khanevski AN, et al. Recurrent ischemic stroke: incidence, predictors, and impact on mortality. Acta Neurol Scand. 2019;140:3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jørgensen HS, Nakayama H, Reith J, Raaschou HO, Olsen TS. Stroke recurrence: predictors, severity, and prognosis. Copenhagen Stroke Study Neurol. 1997;48:891–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marulaiah SK, Reddy MP, Basavegowda M, Ramaswamy P, Adarsh LS. Admission hyperglycemia an independent predictor of outcome in acute ischemic stroke: a longitudinal study from a tertiary care hospital in South India. Niger J Clin Pract. 2017;20:573–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muir KW, McCormick M, Baird T, Ali M. Prevalence, predictors and prognosis of post-stroke hyperglycaemia in acute stroke trials: individual patient data pooled analysis from the virtual international stroke trials archive (VISTA). Cerebrovasc Diseases Extra. 2011;1:17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marik PE, Bellomo R. Stress hyperglycemia: an essential survival response. Crit Care. 2013;17:305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capes SE, Hunt D, Malmberg K, Pathak P, Gerstein HC. Stress hyperglycemia and prognosis of stroke in nondiabetic and diabetic patients: a systematic overview. Stroke. 2001;32:2426–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tziomalos K, et al. Stress hyperglycemia and acute ischemic stroke in-hospital outcome. Metabolism. 2017;67:99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luitse MJ, Biessels GJ, Rutten GE, Kappelle LJ. Diabetes, hyperglycaemia, and acute ischaemic stroke. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:261–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zewde YZ, Mengesha AT, Gebreyes YF, Naess H. The frequency and impact of admission hyperglycemia on short term outcome of acute stroke patients admitted to Tikur Anbessa Specialized hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Neurol. 2019;19:342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott JF, et al. Prevalence of admission hyperglycaemia across clinical subtypes of acute stroke. Lancet. 1999;353:376–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sacco RL, Shi T, Zamanillo MC, Kargman DE. Predictors of mortality and recurrence after hospitalized cerebral infarction in an urban community: the Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Neurology. 1994;44:626–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Climent E, et al. Acute-to-chronic glycemic ratio as an outcome predictor in ischemic stroke in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhuo Y, et al. Clinical risk factors associated with recurrence of ischemic stroke within two years: a cohort study. Medicine. 2020;99: e20830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nardi K, et al. Predictive value of admission blood glucose level on short-term mortality in acute cerebral ischemia. J Diabetes Complications. 2012;26:70–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kes VB, Solter VV, Supanc V, Demarin V. Impact of hyperglycemia on ischemic stroke mortality in diabetic and non-diabetic patients. Ann Saudi Med. 2007;27:352–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roquer J, et al. Glycated Hemoglobin Value Combined with Initial Glucose Levels for Evaluating Mortality Risk in Patients with Ischemic Stroke. Cerebrovasc Diseases (Basel, Switzerland). 2015;40:244–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jing J, et al. Prognosis of ischemic stroke with newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus according to hemoglobin A1c criteria in Chinese population. Stroke. 2016;47:2038–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wan Sulaiman WA, Hashim HZ, Che Abdullah ST, Hoo FK, Basri H. Managing post stroke hyperglycaemia: moderate glycaemic control is better? An update EXCLI journal. 2014;13:825–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuentes B, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines on glycaemia management in acute stroke. Eur Stroke J. 2018;3:5–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Godoy DA, Behrouz R, Di Napoli M. Glucose control in acute brain injury: does it matter? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2016;22:120–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drury P, et al. Management of fever, hyperglycemia, and swallowing dysfunction following hospital admission for acute stroke in New South Wales, Australia. Int J Stroke. 2014;9:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomassen L, et al. Acute stroke treatment in Europe: a questionnaire-based survey on behalf of the EFNS Task Force on acute neurological stroke care. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10:199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng T-M. Taiwan's National Health Insurance system: high value for the dollar. in six countries, six reform models: the healthcare reform experience of Israel, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Singapore, Switzerland and Taiwan 171–204 (WORLD SCIENTIFIC, 2009).

- 27.Cheng CL, Chien HC, Lee CH, Lin SJ, Yang YH. Validity of in-hospital mortality data among patients with acute myocardial infarction or stroke in National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan. Int J Cardiol. 2015;201:96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee M, Wu YL, Ovbiagele B. Trends in incident and recurrent rates of first-ever ischemic stroke in Taiwan between 2000 and 2011. J Stroke. 2016;18:60–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mapoure YN, et al. Acute stroke patients with newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus have poorer outcomes than those with previously diagnosed diabetes mellitus. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;27:2327–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu B, et al. Stress hyperglycemia and outcome of non-diabetic patients after acute ischemic stroke. Front Neurol. 2019;10:1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dungan KM, Braithwaite SS, Preiser JC. Stress hyperglycaemia. Lancet. 2009;373:1798–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts GW, et al. Relative hyperglycemia, a marker of critical illness: introducing the stress hyperglycemia ratio. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:4490–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li WA, et al. Hyperglycemia in stroke and possible treatments. Neurol Res. 2013;35:479–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pan Y, et al. Pancreatic β-cell function and prognosis of nondiabetic patients with ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2017;48:2999–3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jing J, et al. Insulin resistance and prognosis of nondiabetic patients with ischemic stroke: the ACROSS-China Study (Abnormal Glucose Regulation in Patients With Acute Stroke Across China). Stroke. 2017;48:887–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shin TH, et al. Metabolome changes in cerebral ischemia. Cells. 2020;9:1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen J, et al. High glucose induces apoptosis and suppresses proliferation of adult rat neural stem cells following in vitro ischemia. BMC Neurosci. 2013;14:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cai Y, et al. Glycogenolysis is crucial for astrocytic glycogen accumulation and brain damage after reperfusion in ischemic stroke. IScience. 2020;23:101136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parsons MW, et al. Acute hyperglycemia adversely affects stroke outcome: a magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy study. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:20–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shimoyama T, Kimura K, Uemura J, Saji N, Shibazaki K. Elevated glucose level adversely affects infarct volume growth and neurological deterioration in non-diabetic stroke patients, but not diabetic stroke patients. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21:402–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niktabe, A., et al. Hyperglycemia Is Associated With Computed Tomography Perfusion Core Volume Underestimation in Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke With Large-Vessel Occlusion. Stroke 4(2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Krewson EA, et al. The proton-sensing GPR4 receptor regulates paracellular gap formation and permeability of vascular endothelial cells. IScience. 2020;23:100848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ashrafi G, Wu Z, Farrell RJ, Ryan TA. GLUT4 mobilization supports energetic demands of active synapses. Neuron. 2017;93:606-615.e603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pearson-Leary J, Jahagirdar V, Sage J, McNay EC. Insulin modulates hippocampally-mediated spatial working memory via glucose transporter-4. Behav Brain Res. 2018;338:32–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bergsneider M, et al. Cerebral hyperglycolysis following severe traumatic brain injury in humans: a positron emission tomography study. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:241–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carre E, et al. Metabolic crisis in severely head-injured patients: is ischemia just the tip of the iceberg? Front Neurol. 2013;4:146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kalfon P, et al. Severe and multiple hypoglycemic episodes are associated with increased risk of death in ICU patients. Crit Care. 2015;19:153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nukui S, et al. Risk of Hyperglycemia and Hypoglycemia in Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke Based on Continuous Glucose Monitoring. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28: 104346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wada S, et al. Outcome Prediction in Acute Stroke Patients by Continuous Glucose Monitoring. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018. 10.1161/JAHA.118.008744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Y, et al. Association of hypertension with stroke recurrence depends on ischemic stroke subtype. Stroke. 2013;44:1232–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gillett MJ. International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1c assay in the diagnosis of diabetes: diabetes Care. Clin Biochem. 2009;32(7):1327–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sung SF, et al. Validation of algorithms to identify stroke risk factors in patients with acute ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack, or intracerebral hemorrhage in an administrative claims database. Int J Cardiol. 2016;215:277–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hsieh CY, et al. Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database: past and future. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:349–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the corresponding author.