Abstract

Introduction

Adolescence is a challenging time in a child’s life and can be even more stressful for those with a chronic medical condition such as diabetes mellitus. Adolescents and young adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes experience worsening glycemic levels as they enter adulthood. Data suggest that a formalized health care transition process and beginning transition preparation in early adolescence leads to better transition outcomes.

Methods

The aim of this study was to create a transition of care program for youth with diabetes in a standalone children’s hospital by following the Got Transition Six Core Elements of Health Care Transition. First, we implemented a transition of care policy and formalized how we discussed transition of care with patients and families in early adolescence. Further improvements have included assessing readiness to transition, designing a curriculum centered around adolescent-specific issues and how they relate to diabetes management, and forming connections with adult endocrinologists in the area to establish a seamless transition process.

Results

After implementing our program, 90 % (28/31) of our patients indicated they were very or somewhat ready to transition to adult care.

Discussion

We outline our process for developing a transition of care program and provide a practical tool for other pediatric diabetes providers who are interested in implementing a similar program.

Keywords: Pediatric, Diabetes, Type 1 diabetes, Adolescents, Transition

1. Introduction

Health and psychosocial challenges during the transition from pediatric to adult health care are well established in the literature. Adolescents and young adults (AYA) with diabetes must transition from pediatric to adult diabetes specialty care and manage their unique developmental, psychosocial, and biological needs. Delays in establishing care with a new adult diabetes practitioner occur in about one-third of AYA and are associated with worsening glycemic levels, increased complications and hospitalizations, and increased stress on young adults and their families.1., 2., 3., 4., 5., 6.

To date, there are only two published randomized controlled trials (RCT) of transitional care interventions for AYA with diabetes; both tested the impact of a transition coordinator versus usual care on adult diabetes care clinic attendance rates and HbA1c.7., 8. In both studies, AYA transitioned from pediatric diabetes care directly to adult diabetes care with the assistance of a transition coordinator who helped with making and keeping appointments, transferring medical records, and facilitating referrals to other services (e.g., psychologist). Findings were mixed with regard to adult care clinical attendance, but neither study found improvements in post-transition HbA1c. A systematic review identified 18 retrospective cohort and quasi-experimental studies that examined the efficacy of transition coordinators, transition clinics, group education, or a combination thereof on diabetes outcomes.9 All but one study reported an improvement in or maintenance of HbA1c post-transfer, but when the authors pooled data from four studies with a control group, there were no differences in HbA1c post-transfer.

Although transition clinics and coordinators do appear to confer some degree of added benefit in both controlled and non-controlled studies, the added cost and availability of practitioners to provide these services raises concerns about their generalizability and feasibility. Thus, a more scalable approach where transition services are integrated into a pediatric diabetes clinic may be more feasible. The purpose of this paper is to describe how our team developed and implemented a transition of care program for youth with diabetes in a standalone children’s hospital. To do this, we followed Got Transition’s Six Core Elements of Health Care Transition, an approach advocated by the American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians, and American Academy of Pediatrics.10 The Six Core Elements include: 1) developing a policy or guide surrounding transition of care, 2) tracking progress using a flow-sheet registry, 3) assessing self-care needs and offering education on identified needs, 4) developing a health care transition plan with medical summary, 5) transferring to an adult practice, and 6) confirming transfer completion and eliciting consumer feedback.

2. Methods

Implementation of our health care transition program began as a practice improvement project. All procedures were reviewed by our site’s Institutional Review Board, and the project was deemed “Not Research.” We followed the Got Transition Six Core Elements of Health Care Transition guidelines for transitioning AYA to an adult health care clinician. We began by establishing a multidisciplinary transition team consisting of three pediatric endocrinologists, a pediatric medicine resident, a nurse practitioner, three certified diabetes care and education specialists (CDCES), and a pediatric health psychologist. The transition team met monthly to develop and refine steps for implementing the Six Core Elements in our pediatric diabetes clinics. Our practice consists of about 1100 children with type 1 diabetes (T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) who are cared for by five pediatric endocrinologists, three advanced practicing nurse practitioners, six CDCES, one registered dietician, and one licensed clinical social worker. We serve a largely Medicaid-insured population with about 67 % of our patients on Medicaid.

2.1. Core Element 1: transition and care policy/guide

The first step was for the transition team to formalize our clinic’s transition policy and to systematically relay this information to AYA and their families. We developed a transition of care policy letter to inform youth with diabetes and their caregivers about our clinic’s transition process (found in Appendix 1). We distributed the letter to AYA ages 12–16 years with both T1D and T2D. We began by targeting AYA followed by the providers on the transition team and then expanded to the rest of our practice. Our current process begins with the CDCES assigned to the clinic determining which patients are eligible to receive the letter based on their age and whether they previously received the letter. Then, their physician or nurse practitioner distributes the letter to and discusses the transition policy with the AYA and their family and documents the date of delivery in the Diabetes Summary Form in Epic (Epic Systems, Madison, WI), our health system’s electronic health record (see Core Element 2). Our goal for the current study was to distribute the transition policy letter to at least 80 % of eligible patients within two years.

2.2. Core Element 2: tracking and monitoring

To track and monitor AYA and their receipt of the Six Core Elements, we utilized a Diabetes Summary Form, which is a report built into Epic. The form includes information about demographics and diagnosis (i.e., diabetes type, antibodies, and age at and date of diagnosis), technology (i.e., glucose monitor and insulin pump use and type), medications, comorbidities, other health maintenance/screening (e.g., date of last dilated eye exam, date of last visit with dietitian), immunizations, adverse events (i.e., diabetic ketoacidosis [DKA], serious hypoglycemia), and transition information. Providers completed the Diabetes Summary Form for all patients with diabetes regardless of age and updated it at each quarterly visit. Providers began to complete the transition information section after they provided AYA and families with the transition policy letter. The transition information section included the date that the transition policy letter was shared, the date of the last transition readiness assessment, a medical summary, an emergency care plan, the date timing of transfer was discussed with AYA and their family, the contact information for selected adult care provider, and the transfer of care (date of transfer to adult provider, final transition readiness assessment, plan of care including goals and actions, and legal documents).

2.3. Core Element 3: transition readiness

To assess AYA health care transition readiness skills, we utilized the Readiness Assessment of Emerging Adults with Diabetes Diagnosed in Youth (READDY) survey.11 The READDY survey is a validated, diabetes-specific tool that assesses perceived confidence in diabetes knowledge and management abilities among AYA. It consists of 44 items divided into four domains: Diabetes Knowledge, Health System Navigation, Insulin Self-Management, and Health Behaviors.

Implementing transition readiness screening in diabetes clinics was an iterative process that began by working with Epic team members to build the READDY into the electronic health records (EHR). At first, we screened only AYA ages 14–16 years who were followed by providers on the transition team and later expanded to all AYA in the practice who were age ≥ 14 years. The AYA received the READDY screening annually. Initially, a member of the transition team or CDCES identified eligible AYA and assigned them the READDY survey through the patient portal. About one year following initiation of transition readiness screening, our Epic team members automated the screening such that all eligible patients received the READDY automatically via the patient portal. Providers were responsible for documenting completion of the READDY survey in the Diabetes Summary Form.

2.4. Core Element 4: transition planning

Results of the READDY screening guided transition planning. Transition planning encompassed several ongoing activities intended to build health literacy and independent self-care skills, assist in preparing for changes that happen at age 18 years with regard to medical information privacy and decision making, and guide the timing of transfer and the selection of a new adult clinician. The CDCES, dietitians, and social workers reviewed the READDY screening results with AYA and their families at follow-up appointments throughout the year. Education was tailored based on scores in the four READDY domains mentioned above so that each care provider could address areas of deficit. For example, our licensed clinical social worker helped increase knowledge regarding Health System Navigation.

2.5. Core Element 5: transfer of care

At the last visit for pediatric diabetes care, the AYA received a printed copy of their completed Diabetes Summary Form, which served as a comprehensive record of their diagnosis and current treatment modality including use of technology along with any co-morbidities and history of diabetes-related hospitalizations. We also aimed for every AYA to confirm a scheduled appointment with an adult diabetes provider at their final visit.

2.6. Core Element 6: transfer completion

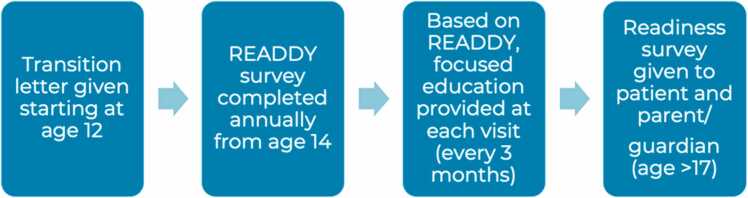

As part of the final core element, we established ongoing and collaborative partnerships with local adult endocrinology clinics. Our goal was to develop a process for ensuring a seamless transition to adult care for the majority of our AYA with diabetes. This included identifying insurances accepted and a process for referring and scheduling patients (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Our clinic’s transition of care process based on the Six Core Elements.

We also began to elicit anonymous feedback from AYA and their parent/caregiver on the experience with the transition process. We utilized the Health Care Transition Feedback Surveys from Got Transition, which included 11 items that assessed whether AYA and their parents thought their pediatric health care team followed through with transition preparation recommendations (e.g., “Explained the transition process in a way that you could understand?” and “Talked to you about the need to have health insurance as you become an adult?”).10 The survey also included a question about perceived readiness to move to a new adult care provider (“Very ready,” “Somewhat ready,” or “Not ready at all”).10 The AYA completed the survey via paper/pencil or online at their second-to-last or last appointment in pediatric diabetes care. The CDCES or physician identified eligible AYA, and the physician would distribute and collect the survey from the AYA and parent following completion.

We also obtained feedback from providers and CDCES who completed a survey (obtained from Got Transition) about our previous transition methods and new process.10 The survey was distributed to the five physicians, three nurse practitioners, and six CDCES in the practice via email and around the office on paper.

3. Results

Below, we report results from implementing each of the six core elements between January 4, 2021, when there were no formal transition services, and December 30, 2022, when we ended the data collection period and the elements became our standard of care. Where possible, we report rates of completion of core element components among diabetes team providers (five pediatric endocrinologists and three nurse practitioners). We noted that two providers were not documenting distribution of the transition letter (average distribution 6 % [14/230] and 3 % [6/184]) or READDY survey (average distribution 17 % [25/147] and 14 % [13/93]), despite coaching by our transition team. The transition team therefore agreed to exclude these two providers from the aggregate data.

3.1. Core Element 1: transition and care policy/guide

As described above in Methods, a transition of care letter was created for distribution to eligible patients.

3.2. Core Element 2: tracking and monitoring

At the start of data collection (1/2021), transition letter distribution had a median of 33 % and mean of 35 %, and by the end (12/2022), it improved to a median of 59 % and a mean of 56 %. During this time, a total of 314 out of 850 eligible patients received a transition letter.

3.3. Core Element 3: transition readiness

Distribution and administration of the READDY began 4/2021, at which time median completion was 37 % and mean 41 %. By the end of the data collection period, the median was 35 % and mean 40 %. The median and means were taken from the weekly averages, ranging from 0 % to 100 %, depending on week.

3.4. Core Element 4: transition planning

Certified diabetes care and education specialists, dietitians, and social workers provided ongoing diabetes education on transition topics to all AYA with diabetes. When the READDY survey was administered, they were able to tailor education according to READDY screening results.

3.5. Core Element 5: transfer of care

We have not begun tracking if all providers provided the complete diabetes summary form and documenting that the AYA had a scheduled follow-up appointment with adult endocrinology; however, this will be a future project.

3.6. Core Element 6: transfer completion

The clinician survey was distributed at the beginning of the project and had a response rate of eight surveys completed of 14 available respondents (57 %). Many clinicians noted that the current health care transition process was ineffective. The largest areas of improvement identified by our staff included setting aside time to work on health care transition with our AYA and being able to collect reimbursement for this effort. Some respondents also noted that they were unsure if the transition program had “buy-in” from our hospital’s senior leadership and had sufficient time and resources granted by leadership to conduct the program. Over the almost three-year data collection period, there were 314 documented adolescents with diabetes mellitus participating in our transition of care program. Additionally, by the end of the project, we were collaborating with four adult endocrinology practices to create a streamlined process to ensure continuity of care. Due to concerns related to AYA privacy and personnel limitations (i.e., lack of a transition coordinator), we were unable to track continuity of care rates between our institution and the adult endocrinology practices. We also were unable to track how many patients transitioned to adult care during our study period. Another limitation of our project was the inclusion of eight different providers located at four clinics, which led to differences in the transition process even during the implementation of our transition of care program. As outlined above, some providers were more likely to follow the program (distributing transition of care letter and documenting completion of the READDY survey) than others.

Of the 31 AYA who completed the transition feedback survey, 90 % (28) indicated they were very or somewhat ready to transition to adult care. Of the 27 caregivers who completed the survey, 77 % (21) indicated that their AYA were very or somewhat ready to transition. The survey also revealed that many AYA noted that they still needed assistance with insurance (10/31, or 32 %) and finding an adult provider (14/31, or 45 %); these categories were also chosen as areas of concern in the caregiver survey (26 % [7/27] and 22 % [6/27], respectively).

4. Discussion

4.1. Previously published literature

In the past, there have been several barriers to determining the best approach to the transition of AYA with diabetes to adult practitioners. Nearly all published studies are quantitative or qualitative/mixed-methods studies that were not well-controlled.9., 12. Few studies used the ‘gold standard’ of study design, randomized controlled trials. Furthermore, several studies examined multiple interventions at once (transition clinic, transition coordinator, extra diabetes education, preparation of medical summary info, etc.), so it was difficult to determine which interventions were effective in best preparing AYA for transition of care. Additionally, success was measured in various metrics: patient satisfaction or perceived readiness (like in our study), changes in HbA1C, number of hospitalizations or DKA events, time to transition, gap between leaving pediatric practice and entering adult practice, and/or clinic attendance.13 Due to our inability to track patients following transition, we were unable to measure most of the variables above (such as HbA1C or complications) while patients were under the care of an adult endocrinologist.

4.2. Our study

The current study demonstrates a process of designing and implementing a health care transition program for AYA with diabetes following the Six Core Elements. Furthermore, we discuss compliance among our pediatric endocrinology providers and the results of the Got Transition perceived readiness surveys from our AYA and their parents. While literature discussing health care transition is plentiful, few papers discuss processes directly related to the Six Core Elements and include a data collection period of nearly two years (the time period for the current study). Although the efficacy and effectiveness of the Six Core Elements have not been tested in randomized controlled trials, nor have the Got Transition surveys undergone thorough psychometric evaluation, Got Transition’s approach is widely adopted by clinics and providers around the world and is widely accepted in the transition literature.

At the beginning of this project, our transition process was not standardized and differed between providers. Similarly, documenting the progress completed for an AYA’s health care transition varied. Our clinicians also indicated that the current process was not working well according to their survey responses at the start of this program. Once we implemented the Six Core Elements, our AYA were informed with a letter beginning at the age of 12 years about the need to transition so that health care transition at age 18 years would not be a surprise. The AYA also completed the READDY survey, which helped guide education by the CDCES and other team members. Providers could document every aspect of the AYA’s health care transition progress in an easy-to-use tab in the EHR known as the Diabetes Summary Form. This process allowed standardization among providers so that each AYA would be prepared to transition to adult care regardless of which endocrinologist or CDCES they saw. Furthermore, implementation of the transition program required little to no cost as meetings occurred during provider administrative time, and the surveys we used were available for free. To date, no papers have described the elements of our program all together— implementing a Diabetes Summary Form to track progress in an EHR, distributing a transition of care policy, distributing a READDY survey inside the EHR, and measuring perceived transition readiness upon leaving the practice for adult care.

4.3. Challenges in transition of care and elements of successful programs

A combination of physiological, developmental, and psychosocial changes that occur during adolescence can make diabetes self-care challenging, which may be reflected in suboptimal glycemic levels. The increased growth hormone secretion during puberty leads to increased insulin resistance, thus causing increases in blood glucose levels to be the norm for AYA with diabetes.14 Epidemiological studies have established that glycemic levels worsen over adolescence with levels peaking around age 18–19 years and improving during young adulthood, by age 22–24 years.12., 15. We have found the same is true regarding an increase in hyperglycemia in our practice’s AYA with diabetes during late adolescence. Additionally, increasing independence from caregivers during adolescence is normative, and for AYA with diabetes, this developmental task typically goes along with the transfer of responsibility for diabetes self-management tasks from parent to AYA. During this time, many AYA begin new jobs, move away for jobs or college, and obtain new health insurance.16 Moreover, psychological disorders are more common in AYA with diabetes. High-risk behaviors (e.g., alcohol use, unsafe sex) occur at similar rates as the general population, and fear of diabetes complications in adulthood are common.14 All of these factors come into play as AYA transition their diabetes care from pediatric to adult health care teams.

Not surprisingly, gaps in establishing care with an adult diabetes provider are common. In a study of Ontario youth by Shulman et al., almost half of the AYA had a gap of more than 12 months in diabetes care between adult and pediatric providers.17 This is concerning given that the American Diabetes Association recommends that glycemic control should be assessed by a physician every three months.6 Garvey et al. also found a gap of more than six months in establishing care in 34 % of Boston-area AYA.18 A review by Lyons et al. saw that among the five studies that tracked visit frequency, all five had found a decrease in visit frequency after transition.19

Given the prevalence of extended gaps in care during the health care transition, the importance of structured transition programs has been emphasized by several professional organizations. The American Diabetes Association (ADA), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE), along with many other organizations, created a joint statement to discuss issues related to transition and graded interventions for various transition program components based on evidence published.20 In addition, the ADA Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes 2024 statement noted, “Pediatric diabetes care teams should implement transition preparation programs for youth beginning in early adolescence and, at the latest, at least one year before the anticipated transfer from pediatric to adult health care,” and “Interprofessional adult and pediatric health care teams should provide support and resources for adolescents, young adults, and their families prior to and during the transition process from pediatric to adult health care”6. We used this statement for guidance when deciding when to begin preparation for transition in our AYA with diabetes (age 12 years).

Because of the many risk factors that place AYA with diabetes at risk for suboptimal health outcomes, there is a clear need to prepare AYA for developing independence and competency in taking care of their health needs once they transition. Published studies have examined dedicated transition clinics,9., 21., 22. coordinators,9., 23. transition readiness questionnaires,21., 22., 24. group education,9 a post-discharge follow-up program,25 and utilization of the Six Core Elements.26 Schultz et al.’s meta-analysis concluded that participants attending a transition program that contained more than one component (e.g., transition clinic and transition coordinator) had a greater decline in HbA1c one year post transition compared with those who attended a program that contained a single component.9 We attempted to incorporate as many aspects of transition planning as we could into our program, including the Six Core Elements and a transition readiness coordinator, in the hopes of producing a lower HbA1c after transition (though we could not track post-transition data). In a retrospective examination of AYA satisfaction with the transition process, Garvey et al. found that AYA who felt mostly/completely prepared for transition had a lower likelihood of a gap greater than six months between pediatric and adult care.18 In the same study, transition satisfaction (mostly/completely satisfied) and preparation (mostly/completely prepared) were very highly associated (chi square, p < 0.0001).18 In Cadogan et al.’s study, despite having high satisfaction with the transition clinic, only 34.6 % of AYA answered, “I feel ready to move to adult care” on their survey, which showed a lack of confidence.21 While we did not survey clinic satisfaction, our project showed a self-reported readiness to transition of 90 % from our AYA with diabetes.

Barriers to the transition process have been well-documented in the literature. Several studies emphasize the need for pediatric and adult provider communication, both between each other and with the AYA. White et al. found that the lack of communication and coordination between the different practice styles was the most common obstacle reported by both pediatric and adult providers.26 Lyons et al. also found that poor communication between pediatric and adult providers and differences in operations led to practical challenges for the AYA and lack of knowledge about resources available to them.14 By establishing relationships with adult endocrinologists, our team hopes to improve the communication between the pediatric and adult providers for our transitioning patients. Schultz et al.9 found three studies in which AYA participated in joint visits with both the pediatric and adult provider (a possible subject of future study in our clinic). Another area of concern is uninsurance or underinsurance,20 which may explain the delay in accessing adult providers due to fear of cost.27 Monaghan et al. found that this care gap was significantly higher in Hispanic AYA when compared with non-Hispanic white and African American AYA.27 Other barriers to transition for AYA with various chronic conditions are unstable living conditions, lack of high school degree, low parental education, lack of insurance, distance from adult clinicians, low income, poor psychosocial functioning, and age.26 This information highlights the need for social workers and an interdisciplinary team to assist in transitioning the AYA so that they continue to be insured during transition. Our clinic has one social worker who works to address the barriers above to ensure a smooth transition to adult care.

4.4. Future plans

In the future, we will continue distributing the transition letter and the READDY survey and continue documenting completion of the Diabetes Summary Form in Epic to track transition progress. We hope to expand our network of adult endocrinologists so that AYA can find providers closer to their homes and colleges. We also hope to extend our health care transition process to other primary care and subspecialty departments in our children’s hospital. Furthermore, the current study provides opportunity for other endocrinology practices to follow our process for creation and distribution of transition materials.

5. Conclusion

Adolescents and young adults must balance a multitude of complicated and competing demands. For those with diabetes, the need to coordinate daily self-management, find and engage with appropriate health care providers, and obtain access to appropriate supplies and medical care must be incorporated into all of the normative decisions that AYA make related to relationships, occupations, living arrangements, and financial management. Thus, it is not surprising that many AYA with diabetes struggle to establish care with a new, adult-focused diabetes care team and achieve in-range glycemic levels. To mitigate these adverse outcomes, both researchers and practitioners have recommended structured transition programs to assist AYA with diabetes through the transition to adult care. However, few studies have demonstrated that these types of programs are feasible to implement in standard diabetes care. Our practice improvement project showed that it is feasible to implement a structured transition process that is satisfactory to AYA, caregivers, and health care providers.

Funding Statement

The authors declare that they have no funding to report.

Funding

The authors declare they have no funding to report.

Ethical Statement

All procedures were reviewed by our site’s Institutional Review Board and the project was deemed “Not Research.”

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Neha Vyas: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization. Jessica Pierce: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization. Felicia Cooper: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.hctj.2024.100060.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Garvey K.C., Foster N.C., Agarwal S., et al. Health care transition preparation and experiences in a U.S. national sample of young adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(3):317–324. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pacaud D., Yale J.F., Stephure D., Trussell R., Davies H.D. Problems in transition from pediatric care to adult care for individuals with diabetes. Can J Diabetes. 2005;29(1):13–18. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakhla M., Daneman D., To T., Paradis G., Guttmann A. Transition to adult care for youths with diabetes mellitus: findings from a universal health care system. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):e1134–e1141. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duke D.C., Raymond J.K., Shimomaeda L., Harris M.A. Recommendations for transition from pediatric to adult diabetes care: patients’ perspectives. Diabetes Manag. 2013;3(4):297–304. doi: 10.2217/dmt.13.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agarwal S., Raymond J.K., Isom S., et al. Transfer from paediatric to adult care for young adults with type 2 diabetes: the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. Diabet Med. 2018;35:504e12. doi: 10.1111/dme.13589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee 14. Children and adolescents: standards of care in diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(Suppl. 1):S258–S281. doi: 10.2337/dc24-S014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White M., O’Connell M.A., Cameron F.J. Clinic attendance and disengagement of young adults with type 1 diabetes after transition of care from paediatric to adult services (TrACeD): a randomised, open-label, controlled trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2017;1(4):274–283. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(17)30089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spaic T., Robinson T., Goldbloom E., et al. Closing the gap: results of the multicenter Canadian randomized controlled trial of structured transition in young adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(6):1018–1026. doi: 10.2337/dc18-2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schultz A.T., Smaldone A. Components of interventions that improve transitions to adult care for adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60(2):133–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White P, Schmidt A, Ilango S, Shorr J, Beck D, McManus M . Six Core Elements of Health Care Transition™ 3.0: An Implementation Guide. Washington, DC: Got Transition, The National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health; 2020.

- 11.Corathers S.D., Yi-Frazier J.P., Kichler J.C., et al. Development and implementation of the readiness assessment of emerging adults with type 1 diabetes diagnosed in youth (READDY) tool. Diabetes Spectr. 2020;33(1):99–103. doi: 10.2337/ds18-0075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanna K.M., Woodward J. The transition from pediatric to adult diabetes care services. Clin Nurse Spec. 2013;27(3):132–145. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0b013e31828c8372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pierce J.S., Wysocki T. Topical review: advancing research on the transition to adult care for type 1 diabetes. J Pedia Psychol. 2015;40(10):1041–1047. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv064. doi:101093/jpepsy/jsv064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lyons S.K., Libman I.M., Sperling M.A. Clinical review: diabetes in the adolescent: transitional issues. J Clin Metab. 2013;98(12):4639–4645. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller K.M., Foster N.C., Beck R.W., et al. Current state of type 1 diabetes treatment in the U.S.: updated data from the T1D Exchange clinic registry. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(6):971–978. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0078. PMID: 25998289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Commissariat P.V., Wentzell K., Tanenbaum M.L. Competing demands of young adulthood and diabetes: a discussion of major life changes and strategies for health care providers to promote successful balance. Diabetes Spectr. 2021;34(4):328–335. doi: 10.2337/dsi21-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shulman R., Fu L., Knight J.C., Guttmann A., Chafe R. Acute diabetes complications across transition from pediatric to adult care in Ontario and Newfoundland and Labrador: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2020;8(1):E69–E74. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20190019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garvey K.C., Wolpert H.A., Rhodes E.T., et al. Health care transition in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(8):1716–1722. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyons S.K., Becker D.J., Helgeson V.S. Transfer from pediatric to adult health care: effects on diabetes outcomes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2014;15(1):10–17. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters A., Laffel L., American Diabetes Association Transitions Working Group Diabetes care for emerging adults: Recommendations for transition from pediatric to adult diabetes care systems: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association, with representation by the American College of Osteopathic Family Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the American Osteopathic Association, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Children with Diabetes, The Endocrine Society, the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes, Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International, the National Diabetes Education Program, and the Pediatric Endocrine Society (formerly Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society) Diabetes Care. 2011;34(11):2477–2485. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cadogan K., Waldrop J., Maslow G., Chung R.J. S.M.A.R.T. transitions: a program evaluation. J Pediatr Health Care. 2018;32(4):e81–e90. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2018.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams S., Newhook L.A.A., Power H., Shulman R., Smith S., Chafe R. Improving the transition of pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes into adult care by initiating a dedicated single session transfer clinic. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;6:11. doi: 10.1186/s40842-020-00099-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levy-Shraga Y., Elisha N., Ben-Ami M., et al. Glycemic control and clinic attendance of emerging adults with type 1 diabetes at a transition care clinic. Acta Diabetol. 2016;53(1):27–33. doi: 10.1007/s00592-015-0734-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Little J.M., Odiaga J.A., Minutti C.Z. Implementation of a diabetes transition of care program. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31(2):215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinbeck K.S., Shrewsbury V.A., Harvey V., et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial of a post-discharge program to support emerging adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus transition from pediatric to adult care. Pediatr Diabetes. 2015;16(8):634–639. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White P.H., Cooley W.C., Transitions clinical report authoring group, American academy of pediatrics, American academy of family physicians, American college of physicians Supporting the health care transition from adolescence to adulthood in the medical home. Pediatrics. 2018;142(5) doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monaghan M., Hilliard M., Sweenie R., Riekert K. Transition readiness in adolescents and emerging adults with diabetes: The role of patient-provider communication. Curr Diabetes Rep. 2013;13(6):900–908. doi: 10.1007/s11892-013-0420-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.