Abstract

The complex link between cognitive distortions (CDs) and criminal behavior is explored in this systematic literature review, with particular attention paid to typologies, contributions to criminal behavior, and correlations with different forms of crime. The review includes 25 studies that met rigorous inclusion criteria and were sourced from Scopus, Web of Science (WoS), ScienceDirect, PubMed, and PubMed Central (PMC). The selected research, which was published between 2019 and 2024, focuses on the link between CD and criminal conduct. This review reveals the relationship between CDs and criminal activity, emphasizing how these distortions have significant consequences on the actions of offenders. The findings suggest that CDs not only induce unlawful conduct but also have distinct impacts on various kinds of offenses. This review emphasizes the importance of understanding CDs in criminal conduct, providing insights into prevention strategies, rehabilitation programs, and therapy interventions. It offers an extensive overview of the significant role that CDs play in influencing criminal behavior at a time when efficient crime prevention and rehabilitation programs are essential. Through illuminating the complex relationships between CDs and criminal conduct, this research provides useful information for mental health practitioners and rehabilitation facilities. Beyond the realm of academia, the implications enable the creation of focused therapies that target certain CDs common to individuals convicted of crimes. Ultimately, this synthesis of research findings is a valuable resource for informing evidence-based methods to reduce recidivism and improve societal well-being.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40359-024-02228-0.

Keywords: Cognitive distortions (CDs), Criminal behavior, Recidivism, Typologies, Review

Background

Complex cognitive processes, including patterns of cognitive distortion (CD), have a considerable impact on criminal conduct and influence people’s engagement in illegal actions. The level of criminal activity is concerning, especially when it comes to common offenses like violence and theft because of their high frequency and detrimental effects on both individuals and communities [1]. Violent crimes, which are offenses involving the use or threat of physical force against another person, frequently cause physical harm and long-term trauma for victims, whereas theft compromises people’s sense of security and trust in society, resulting in broader social and economic consequences. As such, criminal activity, which includes a broad range of behaviors from stealing to violent crimes, is still a problem in society today [2]. The previous two to three decades have seen a broad decline or stabilization in crime rates worldwide, especially in North America and Europe, although crime rates in Africa have been steadily increasing [1]. As geographical variations in crime trends may represent disparities in social, economic, and cultural pressures that might impact the formation and prevalence of CDs among offenders, this divergence is significant when examining the function of CDs in criminal conduct. Numerous intricate aspects, such as psychological characteristics, environmental impacts, and socioeconomic circumstances, influence criminal conduct [3, 4]. Although well-established motivators like peer pressure, poverty, and drug misuse are important influences on criminal behavior, CD can have a substantial impact. Many criminal activities are motivated by CD, a term that refers to behaviors based on irrational thought patterns and illogical beliefs that may have a major impact on an individual’s decision-making processes and behavioral responses. It refers to systemic flaws or biases in an individual’s thought processes that result in distorted views of reality and illogical ideas [5]. These distortions, which include but are not limited to beliefs that downplay or excuse one’s acts, attributing hostile intent to others, and rigid thought patterns that impede problem-solving abilities, are frequently linked to criminal activity. An individual’s decision-making processes, perceptions of social norms, and ultimately their inclination to make choices in ways that are contrary to moral and legal standards are all influenced by distorted thought patterns. This stark reality emphasizes how important it is to identify the fundamental causes of criminal behavior in order to develop intervention, preventative, and rehabilitation plans. Since these cognitive biases frequently serve to legitimize repeated criminal behavior, addressing them is essential to decreasing crime. Interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) can target the core causes of criminal decision-making by addressing the cognitive biases that allow people to justify or rationalize their disruptive actions.

Researchers are closely examining the ways in which specific CDs can influence and be a factor in criminal behavior. This has become a significant focus in academic studies aiming to understand and minimize criminal activities [6]. These distortions have a significant impact on an individual’s perceptions and interactions with the outside world, potentially leading them to engage in fraudulent behavior [7]. The importance of this impact is further demonstrated by real-life incidents. For instance, people convicted of fraud frequently justify their actions by thinking they are entitled to the resources they steal, minimizing the harm done to others (mollification). Similarly, violent offenders may justify their actions by thinking they were disrespected or provoked (power orientation). These examples show how CDs influence criminal behavior [8–10]. The form and presentation of these distortions varied between types of crimes, reflecting the distinctive causes and views that underpin each offense.

Several systematic reviews have looked at different elements of CDs in criminal behavior. Steel et al. [11], for instance, primarily focused on CDs in offenders who interact with child sexual exploitation material (CSEM). Their analysis revealed a considerable gap in the area, underlining the inadequacies of current instruments developed to measure CDs in CSEM offenders, which are frequently adapted from tools used for contact offenders. Although it emphasizes the necessity of CSEM-specific tools, it falls short in addressing the wider range of CDs across many criminal behavior categories, which is the main objective of this study.

In a similar vein, Mohammad Rahim et al. [12] investigated the role of CDs, aggressive behavior, self-control, and personality traits in criminal conduct. Although the research was effective in connecting these psychological features to criminal behavior, it is more extensive in scope than the current review due to its emphasis on personality qualities and a lack of self-control.

Blake and Gannon [13] investigated CDs, notably among sex offenders, and developed a model that linked CDs to empathy impairments and social perception problems. Their study, however, mostly focused on model construction rather than offering in-depth insights into certain types or typologies of CDs, even if it helped to clarify how implicit theories underlie offense-supportive beliefs. Although their model primarily utilized secondary data analysis, recent studies have focused on direct encounters with offenders, including cross-sectional studies and qualitative interviews to capture their CDs [14–17]. This method allows for a more sophisticated understanding of the cognitive processes that underlie criminal conduct by enhancing data authenticity and offering a more detailed, first-hand account of offenders’ life experiences and self-perceptions.

Although these older studies offer insightful information, they either concentrate on assessment consistency or cover a wider variety of psychological qualities than CDs. In contrast, the current review provides a more current and targeted synthesis of the literature by giving priority to new empirical evidence and concentrating explicitly on CDs in a broader spectrum of criminal activities. By examining studies that have been published in the previous six years, this review ensures that our conclusions reflect the most recent empirical results in the area, which makes it an essential addition to the body of current research. This review builds on previous research to provide a more sophisticated understanding of how CDs interact with broader psychological and social processes to shape criminal conduct.

Integrating fundamental research that has impacted our knowledge of these phenomena is very beneficial to the study of CDs in criminal behavior. The categorization and identification of different kinds of distortions, which are essential to comprehend how people misread social cues and defend abnormal conduct, were discussed in Aaron Beck’s research on CDs. Beck [18] as well as Freeman and Oster [19] developed a paradigm of CDs that includes overgeneralization, catastrophizing, and personalizing. This approach has been useful in examining the ways in which these distortions impact criminal minds. Similarly, Sykes and Matza’s [20] research on neutralization tactics, which entail explaining and justifying illegal conduct, gives important insights into how people cope with guilt and rationalize their behavior. This concept is furthered by Bandura’s [21] theory of moral disengagement, which explains how people disengage from moral self-sanctions to conduct destructive behaviors. These ideas are essential to comprehending the processes by which CDs influence criminal conduct in its entirety.

Additionally, two essential frameworks provide insights into the mechanisms behind offense-supportive cognitions in those involved in crime. Szumski et al. [22] present a multi-mechanism theory, identifying three important mechanisms that contribute to the development of CDs among incarcerated individuals. This theory emphasizes how CDs can form long before an offense happens, during the lead-up to or shortly before an offense, and after the crime as a result of the antagonistic context of the individual’s social environment. Furthermore, Ward and Keenan [23] present a thorough framework for investigating those who engage in sexual offenses’ implicit theories about their victims. It explains how incarcerated individuals create sophisticated mental representations of their victims by integrating beliefs, desires, and expectations. The framework distinguishes two types of mental constructs: propositions about victims’ wishes and beliefs about their traits. For example, those who engage in crime may see victims as untrustworthy and sexually promiscuous persons motivated by a desire to manipulate and attract others. These implicit theories direct incarcerated individuals’ interpretations of victims’ acts, allowing them to deduce their mental states and forecast future actions. The framework is based on the idea that those who engage in crime selectively interpret information that supports their implicit assumptions while ignoring data that contradicts them. Together, these frameworks give a thorough explanation of how CDs and implicit theories enable and perpetuate criminal conduct, providing vital insights into the mechanisms behind offense-supportive cognitions.

As society struggles to address the myriad problems related to criminal behavior, exploring the subject of CDs has become essential to research and intervention. By comprehending how these distortions impact people’s perceptions and decision-making processes, more efficient methods for deterring crime, intervening, and assisting people in reintegrating into society may be developed [24]. Acknowledging the prevalence of CD in criminal behaviors is a crucial first step toward establishing options that target the root causes of criminal behavior and eventually improve society as a whole.

It is essential to investigate the function of CD further because of the intricate relationship that exists between criminal behavior and the mind. Researchers have explored the ways in which these distortions appear in various domains of thought, such as misinterpreting social cues and forming skewed impressions of reality [25]. These distortions exert a substantial influence on a person’s ability to make decisions, contributing to the complex web of criminal behavior [26, 27]. However, existing reviews have either focused on particular offender demographics or were written before discoveries about the variety of CDs and their unique connections to different kinds of criminal activity have been made. This systematic research review seeks to fill these gaps by systematically analyzing and classifying various types of CDs and their relationships to criminal behavior.

The following research questions are the main focus of this systematic literature review:

What are the different types of CDs associated with criminal behavior?

How do CDs contribute to criminal behavior?

Are there specific types of CDs more strongly associated with certain types of crime?

The basis for understanding the intricate connection between CD and the narrative of criminal action is presented by these research questions. This study is structured accordingly in the following sections. The materials and methods used to address these questions are described in depth in the following section. Subsequently, the results section focuses on trends in bibliometric terms such as keywords, theories, and important factors associated with CD and criminal behavior, utilizing the identified studies to address the research questions. The ensuing discussion compares the findings to those of other pertinent research. Finally, a thorough discussion is presented following the establishment of the parameters for further studies, summarizing the key findings from the systematic literature review on CD and criminal behavior, as well as the milestones achieved in relation to the specified objective.

Methods

This review was carried out in compliance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [28]. A comprehensive overview of the review protocol is presented in the S1 Appendix.

Eligibility criteria

This systematic literature review utilized rigorous inclusion criteria for the selection of studies to ensure a thorough and comprehensive overview of the relationship between criminal behavior and cognition. The inclusion criterion was English-language papers published between 2019 and 2024. A number of important factors are carefully considered when the time frame is chosen. Although it is still vital to broaden the scope to include research conducted before 2019, the majority of the literature from earlier times focuses on therapeutic implications rather than explicitly addressing the connection between CDs and criminal behavior. This thematic distinction limits the relevance of pre-2019 research to the review’s chosen subject. Nonetheless, we reviewed relevant papers published prior to 2019, but their focus on therapy or peripheral subjects did not materially alter the results of our analysis. Therefore, while acknowledging the fundamental work that has molded this subject, this review gives priority to research that directly examines the association between CDs and criminal conduct, mainly within the more recent literature. The selection of studies was based on their predominant emphasis on individuals categorized as offenders. The review focused on empirical research that provided significant insight into the complicated relationships between cognitive processes and criminal conduct. To comply with the main focus of the review, the selected research had to specifically address and expound on the relationship between criminal behavior and cognition.

In terms of the exclusion criteria, articles published before 2019 were omitted to maintain the review’s emphasis on recent and pertinent research. Furthermore, papers written in languages other than English were excluded to establish a consistent linguistic basis for the synthesis. The inclusion of solely English-language studies helps to standardize the data and reduce the likelihood of diversity in the interpretation of findings. Accurately translating and interpreting research from several languages calls for a lot of resources, such as extra time and access to qualified translators. This is particularly significant for systematic reviews, as credible findings depend on consistent data acquisition and processing. To further expedite the review process toward high-quality, gray literature, doctoral theses, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, book chapters, and conference materials were eliminated. The selection process was further refined to include only studies that made a significant contribution to understanding the intricate connection between cognitive processes and criminal behavior. Excluded from consideration were articles that were not accessible, reports that lacked empirical research methodologies, letters to the editor, minutes of meetings, or informative notes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Type of Study | Studies published between 2019 and 2024 | Studies published before 2019 |

| Empirical research articles presenting primary data | Non-primary research articles (e.g., reviews, letters to the editor, minutes of meetings, or informative notes) | |

| Articles written in English | Articles not available in English | |

| Studies with full-text availability | Studies without full-text access | |

| Population | Individuals who have committed crimes | Individuals who have not committed crimes or those not involved in criminal behavior |

| Outcome | Studies that directly address cognitive distortions linked to criminal behavior | Studies that do not address cognitive distortions related to criminal behavior |

Critical appraisal

The included research had different designs, which made standardizing methodological rigor challenging. We used Covidence, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), and the Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews (ROBIS) to address this. The risk of bias in quantitative studies was assessed using Covidence and ROBIS, whilst qualitative and mixed-methods research was assessed using MMAT in a systematic approach. This set of tools provides an extensive assessment of bias across various study designs, improving the review’s transparency and credibility. The use of these methods enables a more nuanced and rigorous evaluation of the evidence, which contributes to the review’s overall credibility.

Information sources

A comprehensive and organized search strategy was developed to meet the predetermined eligibility criteria after determining that Scopus, WoS, ScienceDirect, PubMed, and PMC were the key sources. Following the PRISMA statement guidelines, this systematic literature review gathered data from a variety of sources to discover relevant findings about the role of CD in criminal behavior. These databases were selected due to their profound bibliometric indicators and broad coverage of scientific literature. In an effort to incorporate the most recent studies, searches were carried out until May 2024.

Search strategy

The search technique utilized in this systematic literature review was a combination of phrases to discover research about CDs and criminal behavior. The primary search terms were “cognitive distortion,” “thinking error,” and “thinking bias,” which were merged using the Boolean operator “OR” to account for terminology variances. The search was then further refined by pairing these phrases with terms associated with criminality, such as “criminal behavior”, “criminal behaviour,” “offender,” and “delinquency,” all using the Boolean operator “AND.” This method was used across relevant databases to ensure a thorough retrieval of research on the relationship between CDs and criminal conduct.

Study selection process

Ensuring the transparency and integrity of the study selection process, the researchers used Microsoft Excel® to independently execute the search and exclusion methods following PRISMA 2020 criteria. This strategy aimed to reduce informational bias and preserve uniformity in the way inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. In instances where disagreements surfaced, the researchers had discussions and provided rationales until a consensus was achieved. The systematic literature review’s research selection process was made rigorous and transparent by using this collaborative and iterative method.

Data collection process

To find relevant research, the screening procedure for data collection started with an assessment of study titles. The full texts and abstracts were then carefully reviewed to ensure they met the inclusion criteria. Each study’s relevant data, including study design, sample size, study population, measures of CD, types of CD identified, and main findings, were methodically retrieved. This focused strategy made sure that all pertinent information, which is essential to comprehending the role CD plays in criminal behavior, was thoroughly synthesized. The data extraction procedure was made more precise and reliable by the collaborative efforts of three independent reviewers. Independent data extraction was conducted by each reviewer from a subset of the included papers. Following the first independent extraction step, the reviewers gathered to compare their extracted data, address any differences or inconsistencies, and achieve an agreement on the final data set. The collaborative method fostered completeness and thoroughness in the data extraction process in addition to making it easier to find and address any inconsistencies.

Effect measure

This systematic literature review highlights CD assessments as primary effect measures to shed light on the relationship between CD and criminal behavior. The review concentrates on the wide range of measures used to evaluate CD, aiming to identify patterns, correlations, or differences within the extensive body of research. These CD measures provide rich insights that inform the synthesis and interpretation of data, leading to a thorough understanding of their impact on criminal behavior.

Methodological design

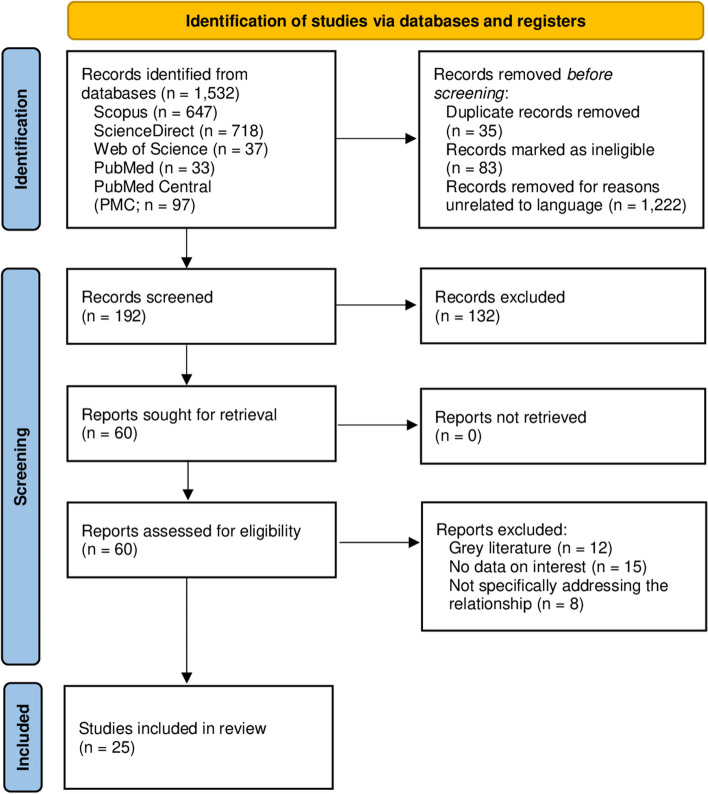

The PRISMA flowchart (see Fig. 1) illustrates the precise selection procedure used in this systematic literature review, following the PRISMA protocol. Of the 1,532 records that were found using different databases, 1,340 were excluded because they were duplicates or ineligible for reasons unrelated to language. 60 reports were obtained for comprehensive analysis after 192 records were deemed eligible for retrieval based on the application of a year limit. 25 papers were ultimately included in the final synthesis after a rigorous screening procedure to ensure they fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The systematic literature review’s evidence synthesis was firmly established by deliberately choosing research that explicitly addressed the relationship between CD and criminal conduct.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart

An overview of these 25 papers is provided in Table 2, which includes relevant data such as authors, study design, sample size, study population, and CD measures. Furthermore, Table 3 provides an extensive overview of the insights gathered from the included papers by exploring the particular types of CD found as well as the main findings of each study.

Table 2.

General description of study

| Authors | Study Design | Sample Size & Study Population | Measures of Cognitive Distortions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baúto et al. (2022) [14] | Mixed method approach | 66 Portuguese male offenders convicted for crimes of child sexual abuse (CSA) | Cognitive distortion (CD) measure based on FBI Child Molesters Profile Model |

| Civilotti et al. (2023) [17] | Cross-sectional study | 14 Italian male detained stalkers | Dissociative Experiences Scale-II (DES-II), Adult Attachment Interview (AAI), and Index Offence Interview (IOI) |

| D’Urso et al. (2021) [29] | Exploratory research | 128 male sex offenders against adult victims from Italy | Vindictive Rape Attitude Questionnaire (VRAQ), Hanson Sex Attitude Questionnaire (SAQ), and Moral Disengagement Scale |

| D’Urso et al. (2023) [30] | Case study | 1 male sexual offender against minors | Clinical interviews, psychodiagnostic, psychological evaluations, as well as specific psychodiagnostic tests, such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2) and the Erotic Psycho Induction Test |

| Demeter & Rusu (2019) [31] | Correlational design | 55 Romanian incarcerated individuals for robbery, stealing, murder, rape, driving without a license, profanation of graves, attempted robbery, prison-breaking, false testimony, attempt of murder, and trafficking of minors | How I Think Questionnaire (HIT) |

| Grady et al. (2022) [32] | Mixed method approach | 195 individuals convicted of sexual offenses | Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) scale |

| Guerrero-Molina et al. (2023) [33] | Quasi-experiment | 129 men convicted of gender-based violence in penitentiary centers in Spain | Inventory of distorted thoughts about women and the use of violence (IDTWV) and inventory of distorted thoughts concerning violence (IDTV) |

| Haslee & Salina (2019) [34] | Quantitative research | 123 female Malaysian Muslim inmates with drug-related cases | Cognitive Distortion Scale (CDS) |

| Jha & Dhillon (2020) [16] | Cross-sectional study | 75 Indian offenders, under-trial for theft, fraud, snatching and drug related criminal activities | Psychological Inventory of Criminal Thinking Styles-(PICTS-Lay Person Edition) |

| Martínez-Catena et al. (2021) [35] | Pre-post treatment design | 145 men serving a prison sentence for abusing children in Spain | Psychological Assessment Scale for Sex Offenders (PASSO) |

| Mohammad Rahim et al. (2021) [36] | Mixed method approach | 71 male murderers from Malaysia | Malay-validated psychometric instruments, including Zuckerman-Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire-M-40-Cross-Cultural (ZKPQ-M40-CC), Self-Control Scale (SCS-M), Aggression Questionnaire (AQ-12-M), and How I Think Questionnaire (HIT-M) |

| Ngubane et al. (2022) [15] | Qualitative research | 18 incarcerated male perpetrators of rape in South Africa | Interview guide consisting of open-ended questions and probing questions on their background and lifepath, childhood history and familial histories of violence, their views on sexual behavior, misconceptions or ideas related to sexual violence and rape, their mentors or role models, viewpoints on criminal behavior and cultural contextualization, and their spiritual and religious backgrounds. |

| Oettingen et al. (2023) [37] | Cross-sectional study | 102 men incarcerated for sexual offenses in Poland | Polish version of Young Schema Questionnaire – Short Form – 3rd Version (YSQ-S3-PL) |

| Paquette et al. (2019) [38] | Qualitative research | 60 Canadian men with online child sexual exploitation material and solicitation offenses | Investigators from the Sûreté du Québec performed the interviews following organizational protocol. A total of 1,136 statements suggestive of offense-supportive cognitions were retrieved from the verbal conduct of inmates. |

| Pérez-Ramírez et al. (2021) [39] | Cross-sectional study | 194 male prisoners managing mental disorders from Mexico | ACEs questionnaire, and Self-Stigma of Mental Illness Scale-Short Form (SSMIS-SF) |

| Petruccelli et al. (2022) [40] | Cross-sectional study | 96 sex offenders (64 Italians and 32 Portuguese) | Basic Empathy Scale (BES), Moral Disengagement Scale (MDS), Vindictive Rape Attitude Questionnaire (VRAQ), and Hanson Sex Attitude Questionnaire (SAQ) |

| Rezapour-Mirsaleh et al. (2021) [41] | Quasi-experiment | 24 male prisoners with drug-related cases in Iran | Psychological Inventory of Criminal Thinking Styles (PICTS) |

| Saladino et al. (2023) [42] | Cross-sectional study | 29 Italian male sexual offenders | Compulsive Sexual Behavior Inventory (CSBI), Sexual Sensation-seeking Scale (SSSS), High-Risk Situation Checklist, and Attachment Style Questionnaire (ASQ), adapted in Italian |

| Siserman et al. (2022) [43] | Cross-sectional study | 126 prisoners from Romania found guilty of offenses against bodily integrity and other offenses | Young Schema Questionnaire – Short Form – 3rd Version (YSQ-S3) |

| Steel et al. (2021) [49] | Cross-sectional study | 78 adults in the United States with prior convictions for child pornography offenses | Survey questionnaire broken up into three areas: General perceptions; Endorsement of child pornography beliefs; and Legality |

| Szumski & Bartoszak (2022) [44] | Quantitative research | 252 Polish (64 sexual offenders against children, 46 sexual offenders against adults, 74 nonsexual violent offenders, and 68 non-offending males) | Sexual Offenders’ Cognitive Distortions Questionnaire (SOCCDQ) and Child Sexual Abuse Causes and Effects Evaluation Task (CSACEET) |

| Umusig et al. (2024) [45] | Cross-sectional study | 300 offenders from the Philippines with drug-related cases | The Psychological Inventory of Criminal Thinking Styles (PICTS) |

| Velasquez Marafiga et al. (2022) [46] | Descriptive, correlational, and explanatory | 49 men convicted for statutory rape | Young Schema Questionnaire (YSQ-S3) and Cognitive Scale |

| Verkade et al. (2021) [47] | Cross-sectional study | 38 Dutch female offenders (10 property offences, 2 drug-related crimes, 1 arson, 2 theft involving violence or extortion, 2 maltreatment, 7 threats of or attempted homicide, 6 offences in multiple categories, 8 were still awaiting trial) |

Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI), Test of Self Conscious Affects (TOSCA), and HIT questionnaire |

| Wuyts et al. (2023) [48] | Semi-structured interviews | 9 incarcerated Flemish who were identified as persons with sexual offenses (PSOs) | A semi-structured topic list was created in advance based on the prior literature review to validate that all themes were covered |

Table 3.

Types of cognitive distortions associated with criminal behavior

| Authors | Types of Cognitive Distortions Identified | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Baúto et al. (2022) [14] | CDs pertaining to the minimizing, rationalization, and validation of violent actions. | It is believed that CDs are important to comprehend how juvenile sexual delinquents think. Deviant sexual responses may be encouraged by a lack of awareness of societal norms and expectations around conventional sexual practices. Dysfunctional relationship schemas, shortcomings in intimacy and emotional congruence, and abnormal sexual desire can all be linked to CDs. |

| Civilotti et al. (2023) [17] | Stalker behavior was connected to paranoid ideation, grandiosity, entitlement, and being victimized, all of which were assumed to be connected to early attachment experiences. | CDs affect how people view the world and their role in it, which influences criminal conduct. Similar to this, an illusion of control might make someone think they may behave riskily or illegally without repercussions, which could make them more likely to commit crimes. Criminals with a violent past were more likely to display an illusion of control, whereas those with a history related to property violations were more likely to display a hostile attribution bias. These CDs were linked to stalking behavior and were hypothesized to be connected to early attachment events. |

| D’Urso et al. (2021) [29] | Asserting that women are always willing to engage in sexual activity, even when it is coerced or aggressive, and that women and children are the targets of sexual desire. The right to sexuality is also linked to CD when people believe they have the freedom to engage in sexual relations without taking another individual’s consent or welfare into account. | Among male sexual offenders, institutionalization, maltreatment, cognitive biases toward women, and the victim-blaming mechanism are significant risk factors that contribute to recidivism. |

| D’Urso et al. (2023) [30] | Moral disengagement as a means of defending actions, and emotional immaturities that are present in relationships. It also highlights the distortions linked to loneliness, stigma, and low self-esteem. | The inmates’ emotional and cognitive condition, as well as the influence of his life experiences on his behaviors, may be understood through his CDs and emotional relational immaturity. It also highlighted the difficulties the inmate encountered, like losing their friends, employment, and self-worth, as well as the consequent psychological turmoil. CDs that contribute to deviant behavior and impede the treatment route of sexual offenders include moral disengagement, judgments of risk, and insufficient socio-emotional experiences. These distortions aid in the development of criminal conduct because they allow criminals to rationalize their acts, alter risk perceptions, and display immature socioemotional reactions. |

| Demeter & Rusu (2019) [31] | Self-centered, blaming others, minimizing/mislabeling, and assuming the worst. | The data showed that the sample’s degree of antisocial inclinations and self-serving distortions rises with the severity of misconduct. Criminals who commit more violent crimes tend to justify their acts by placing blame on other people and tricking others in order to benefit themselves. |

| Grady et al. (2022) [32] | Minimizing the impact of their actions on other people or rationalizing abusive behavior with references to personal experiences. | Some individuals who have undergone trauma and have committed sexual offenses may have CDs about their concept of healthy relationships, boundaries in bonds, and within the sexual realm. Emotional dysregulation and insecure attachments may be the cause of these distortions. Furthermore, because of their personal experiences with abuse, people may form maladaptive schemas and CDs that legitimate or excuse abusive conduct. |

| Guerrero-Molina et al. (2023) [33] | Beliefs such as “The husband is in charge of the household, so the wife should obey him” and “Women intentionally trigger their partners in the expectation that they will lose control and hit them” are examples of distorted attitudes about women. Beliefs such as “Slapping is sometimes required” and “If women were unwilling to displease their partners so much, they would certainly surely not be mistreated” are examples of distorted thinking concerning violence. | One predictor of a higher frequency of ambivalent sexist notions among aggressors is distorted beliefs about women and violence. Violence is sometimes mistakenly seen by aggressors as a legitimate means of resolving disputes in their relationships. The study concludes that other factors have a role in the beginning and continuation of violence and that CDs do not provide a complete explanation for intimate partner violence. |

| Haslee & Salina (2019) [34] | Self-criticism, self-blame, helplessness, hopelessness, and preoccupation with danger. | The results revealed that only 1.6% of the respondents had severe levels of CD, with the majority of respondents (98.4%) experiencing low to moderate levels of CD. One possible explanation for this might be that the participants in this research are housed in a rehabilitation treatment center, which provides a controlled environment. |

| Jha & Dhillon (2020) [16] | Mollification, power orientation, sentimentality, cognitive indolence, discontinuity, cutoff, entitlement, and superoptimism are the CDs identified in the study. | The study found that CDs such as mollification, power orientation, sentimentality, cognitive indolence, and discontinuity were linked to criminal conduct. It was discovered that these CDs negatively correlated with sociomoral reasoning, suggesting a connection between criminal conduct in both offenders and non-offenders and incorrect thought patterns. |

| Martínez-Catena et al. (2021) [35] | Cognitive schemas that associate children with sexual partners and provide rationales for using force during a sexual encounter. | The CDs associated with child abuse and the use of force during sexual encounters were shown to be minimal in those incarcerated for child abuse. There were no appreciable deficits in these CDs among the research subjects. |

| Mohammad Rahim et al. (2021) [36] | Aggression includes antagonism, rage, placing blame, being self-centered, minimizing or mislabeling, and anticipating the worst. | The concealing act among Malaysian male murderers is motivated by certain psychological characteristics, including fear, rage, and CD (blaming others). The primary methods of murder concealment among Malaysian murderers are postmortem and dumping. When compared to those who hid their victims, those who did not have considerably higher hostility levels. |

| Ngubane et al. (2022) [15] | CDs associated with neglecting responsibilities and conventional gender norms. These include blaming the victim, thinking that men should have the right to participate in rapes, supporting transactional sex, thinking that one is being set up or framed, and disobeying an ancestor’s summons. These distortions expose distorted mental processes that impact inmates’ attitudes and actions. | Adverse consequences are closely related to an individual’s emotional states, emotional regulation skills, reality perception, and the creation of memories tied to behavior that is socially acceptable. This highlights the critical role that maladaptive cognitive schemas play in influencing the development of criminal conduct within the complex interactions between environmental factors and individual personality characteristics. |

| Oettingen et al. (2023) [37] | Disconnection and rejection distortion encompasses emotions of instability and abandonment as well as decreased autonomy and performance. It also includes distrust, abuse, emotional deprivation, humiliation, social isolation, reliance, and incompetence. | Among the group of convicted sexual offenders, emotional deprivation, abandonment or instability, and mistrust or abuse were the most common early maladaptive schemas. The study also discovered a strong correlation between sexual offending and diminished autonomy and performance. Early maladaptive schemas may be crucial in the development of sexually abusive behavior and should be targeted for prevention and therapy. |

| Paquette et al. (2019) [38] | Minimization of harm, denial of victim harm, denial of offense severity, denial of responsibility, victim blaming, offense justification, offense normalization, and offense trivialization | Contact sexual offenses are linked to a higher amount of offense-supportive cognitions being endorsed. The study also emphasizes how crucial it is to comprehend how much inmates’ genuine views are reflected in their cognitive themes, as some cognitive assertions might act as post hoc noncriminogenic reasons. |

| Pérez-Ramírez et al. (2021) [39] | Self-stigma and negative self-perception. | A positive relationship was discovered between the global severity index, anxiety, mania, depression, and stereotype consensus as well as stereotype self-concurrence and self-esteem decline. This suggests that individuals with specific mental health conditions may be more likely to accept societal stereotypes and hold self-defeating beliefs, which might lead to a decline in self-worth and an increase in self-stigma. |

| Petruccelli et al. (2022) [40] | The “Sexual Entitlement” distortion relates to ideas that support legitimate sexual conduct, while the “Sexy Kids” distortion refers to abnormal views toward children. | Significant levels of CDs were observed in sexual offenders, especially when it came to skewed views about sexual rights and deviant views about minors. In sexual offenders, negative childhood and adolescent experiences have been linked to an increase in psychopathological features, empathy deficiencies, CDs, and moral disengagement practices. The cognitive structure linked to sexual fantasies and the perception of sexual correlates was considered accountable for the distortions observed among sexual offenders. Sexual offenders may have compromised cognitive functioning as a result of these distortions. |

| Rezapour-Mirsaleh et al. (2021) [41] | The act of rationalizing and justifying behavior, ignoring thoughts that deter crime, failing to distinguish between needs and wants, having an inclination to use one’s power to control others and the environment, acting altruistically to make up for past transgressions and negative self-perceptions, having an excessive capability to avoid the consequences of criminal behavior, overestimating and confining in one’s abilities to avoid being arrested, lacking permanent problem-solving skills, and experiencing disruptions in one’s thought process. | CDs encourage criminal behavior by persuading people to defend and legitimize their illegal activity. These misconceptions are used by offenders to justify their actions and place blame on others, which results in obnoxious illegal, and antisocial conduct. These distortions also give offenders the impression that crime is a need to survive and that the world is a hostile place, which increases crime and recidivism. Criminal conduct is further influenced by CDs that lead to inflated trust in escaping punishment and justification of actions, such as pride, a lack of empathy, and incorrect beliefs. |

| Saladino et al. (2023) [42] | Negative self-perceptions, an overwhelming desire for approval, or a fear of intimacy are reflected in the maladaptive cognitive schemas associated with a lack of confidence, discomfort with proximity, and relationship paranoia. | There were associations found between insecure attachment patterns and the propensity for sexual sensation-seeking as well as the usage of violence in relationships. These results point to a possible susceptibility among those with insecure attachment styles, pointing to a higher propensity for hazardous and aggressive sexual conduct. These behavioral tendencies are a reflection of the CD caused by overgeneralization, which may raise the probability of recidivism in this population. |

| Siserman et al. (2022) [43] | Lack of self-control, emotional restraint, and mistrust or abuse. | People who have maladaptive cognitive schemas may see the world distortedly and be more prone to see risks where none exist. Hence, this may lead to heightened anxiousness and also an urge to react violently when it is not called for. Maladaptive cognitive schemas can make it difficult for a person to regulate their emotions, which can lead to dangerously reckless behavior.This might make people feel even more dismal and powerless, which can lead them to consider using illegal behavior as a coping method. A sense of entitlement and a general lack of empathy for other people can result from maladaptive cognitive schemas, resulting in people justifying their unlawful activities and engage in antisocial conduct without feeling guilty or ashamed. |

| Steel et al. (2021) [49] | The research discovered CDs associated with behavior that minimizes or rationalizes child pornographic offenses. | CDs influence people to minimize or justify their behaviors, which leads to illegal behavior. People who have distorted views and CDs may engage in criminal actions, such as committing contact violations or other crimes. These CDs can impact the opinions of individuals about the seriousness of their acts and their propensity to commit new crimes, which can encourage criminal activity. Incarcerated individuals of online child sexual exploitation material are not exempt from CDs. In general, CDs can cause people to minimize the harm or justify their illegal behavior, which encourages them to engage in criminal activity. |

| Szumski & Bartoszak (2022) [44] | The “nonsexual entitlement” distortion refers to the idea that people should feel free to participate in harmful or improper nonsexual behaviors. | In comparison to other offender groups and non-offending males, sexual offenders against minors exhibited a greater degree of CD. The depth of CDs and the likelihood of recidivism were also found to positively correlate. Sexually expressive CDs could potentially seen as criminogenic demands. |

| Umusig et al. (2024) [45] | An incarcerated individual who exhibits super optimism is one who makes incorrect assessments of their own personal qualities and of their capacity to avoid the consequences of their unlawful behavior. | Based on the study’s findings, super optimism is the most common criminal thinking style among Persons Deprived of Liberty (PDL). This suggests that the majority of Davao City Jail incarcerated individuals view failure as an event for which they are not responsible and instead assign blame to outside forces. The outcome also demonstrates that the majority of prisoners housed in the Davao City Jail have a criminal mindset characterized by super optimism and have been found guilty of drug-related offenses. |

| Velasquez Marafiga et al. (2022) [46] | Seeking to place the responsibility on the victim, trying to downplay and overlook abusive conduct, and trying to justify abusive behavior. | The prevalence of CDs was shown to be higher in those who have sexually assaulted children or adolescents. Early maladaptive schemas are comprehensive, overarching patterns formed during infancy or adolescence that impact cognitive impairments. Events within the family of origin were linked to CDs, indicating that early experiences contribute to the formation of these distorted views. CDs and the father’s substance misuse, along with certain schemas like defectiveness, grandiosity, and sensitivity to harm, may be interrelated. It was shown that one predicted factor for CDs was the sensitivity to harm. |

| Verkade et al. (2021) [47] | Callous self-centering, minimizing, mislabeling, blaming others, and making assumptions about others (self-centered CDs). | Compared to community controls, female inmates exhibit much greater levels of CDs, especially in the areas of self-centeredness, placing blame on others, mislabeling or minimizing, and presuming the worst. CDs may also impede moral judgment and conscience function, which might lead to illegal action. |

| Wuyts et al. (2023) [48] | Rationalization (offering explanations for their conduct), victim blaming (holding the victim accountable for their victimization), and minimization (downplaying the gravity of their actions). | Bringing together PSOs may cause CDs to become more pronounced. Worldwide specialists contend that a distinct housing system with therapy integrated within may effectively handle these problems. Thus, it may be concluded that Flemish professionals and foreign specialists have different viewpoints about how independent housing affects CDs. |

Results

Description of studies

To offer a thorough overview, we organized the included studies by publication year, country of origin, type of offense, and settings. The studies were published throughout a variety of years, with the greatest number from 2022 (n = 8), followed by 2023 (n = 7), and the lowest number from 2019 (n = 3), 2020 (n = 1), 2021 (n = 5), and 2024 (n = 1). The studies’ geographical scope was broad, including contributions from a number of nations, including Malaysia (n = 2), Portugal (n = 1), and Italy (n = 4). Other nations represented by one or two studies were the United States, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, India, Iran, Mexico, Netherlands, Philippines, Poland, Romania, South Africa, Spain, and Romania. A wide range of offenses were addressed, including drug-related cases (n = 3), child sexual abuse (n = 3), and sexual offenses (n = 7). Most research (n = 19) concentrated on prison environments; fewer studies were carried out at correctional institutions (n = 3), penitentiary centers (n = 2), and rehabilitation centers (n = 1). The 25 included research examined a range of CDs, some focusing on more than one kind of distortion. Seven of the studies reviewed focused on rationalization, while six investigated blaming others. Four studies looked into mental filtering, three at overgeneralization, and two at both all-or-nothing thinking and control fallacies. Furthermore, two studies examined labeling, and one each examined jumping to conclusions and minimization. These results demonstrate the broad scope of CDs assessed in the included studies (see Table 3).

Many of the studies in the examined literature concentrated on certain types of criminal acts, offering insightful information about a range of criminal behavior-related topics. Notably, a substantial number of research investigated sexual offenses, focusing on various dimensions such as child sexual abuse, rape, and sexual offenses against adults. For example, Baúto et al. [14] looked into Portuguese men convicted of child sexual abuse crimes, while D’Urso et al. [29] and D’Urso et al. [30] looked into men who commit sex offenses in Italy, including those against adults and minors. Furthermore, Grady et al. [32] examined those found guilty of sexual crimes, whereas Ngubane et al. [15] focused on male rapists who were imprisoned in South Africa. A number of other research addressed drug-related offenses. Among them, Haslee and Salina [34], Jha and Dhillon [16], Umusig et al. [45], and Rezapour-Mirsaleh et al. [41] delved into instances involving female prisoners in Malaysia, India, the Philippines, and male prisoners in Iran. Additionally, studies on violent offenses were conducted by Guerrero-Molina et al. [33], Pérez-Ramírez et al. [39], and Siserman et al. [43]. These studies concentrated on people who had been convicted of crimes against bodily integrity, managing mental conditions, and gender-based violence, respectively. The literature also explored other offenses, such as property offenses, murder, robbery, and stalking, as reviewed by Demeter and Rusu [31], Civilotti et al. [17], Mohammad Rahim et al. [36], and Verkade et al. [47], respectively. Furthermore, research conducted by Paquette et al. [38], Martínez-Catena and Redondo [35], Oettingen et al. [37], Petruccelli et al. [40], Saladino et al. [42], Steel et al. [49], Szumski and Bartoszak [44], Velasquez et al. [46], and Wuyts et al. [48] offered additional understanding of a range of criminal behaviors, such as child sexual exploitation on the internet, inmates of child sexual abuse material, prior convictions for child pornography offenses, statutory rape, and more. This thorough review of the research offers a multidimensional understanding of the CDs present in a range of criminal behaviors.

The papers included (see Table 2) represent a wide range of study approaches, including quantitative and qualitative methodologies. CDs were frequently regarded as dependent variables in quantitative studies, where researchers evaluated their relationships to a range of independent factors, including individual traits, criminal conduct, and environmental stresses. For example, CDs were the main focus of Guerrero-Molina et al.’s [33] quasi-experiment research, which was descriptive in nature rather than intervention-based and aimed to determine the types and prevalence of CDs in a particular criminal community. Similar to this, Rezapour-Mirsaleh et al.’s [41] experimental investigation measured changes in CDs as the result of interest and used treatment groups focused on criminal thought patterns as the independent variable. In contrast, CDs were commonly investigated through in-depth interviews in qualitative research in order to find trends in the cognitive processes of offenders. Rich insights into how CDs appear and influence criminal conduct were offered by these studies.

The included studies’ critical appraisal showed a range of strengths and weaknesses in different areas. The studies’ sample sizes ranged widely, spanning from individual samples to samples of up to 300 people. Larger sample size studies yielded more reliable and broadly applicable results, while smaller sample sizes restricted the degree to which the results could be applied to larger populations. This variance in sample size underscores the need for future research to aim for bigger sample numbers to improve the reliability of results.

CDs were assessed using self-report questionnaires, structured interviews, and standardized tests. Although self-report questionnaires were beneficial in collecting data swiftly, participants’ subjective reporting raised the possibility of bias. Structured interviews and standardized exams provided more thorough and objective evaluations, although they needed a substantial amount of time and resources. Given the variety of assessment tools, future research should look into integrating several measures to balance the strengths and weaknesses of each approach.

The study designs comprised qualitative studies, cross-sectional, quasi-experiment, and pre-post treatment design methods. In general, experimental designs yielded more complete and robust results, facilitating the analysis of changes over time and the effects of particular treatments. These designs did, however, also have drawbacks, such as detection bias and performance bias brought on by the absence of blinding. While cross-sectional studies were much simpler to conduct, they merely presented a glimpse in time and offered limited insights into causal linkages.

The in-depth assessment of CDs and the robust study designs that offered insightful information on the connection between criminal behavior and CDs were two common qualities found in the studies. Nevertheless, a number of weaknesses were also highlighted, including the possibility of self-report bias, small sample sizes, restricted generalizability, and the risks of biases in performance and detection. Some studies, for example, did not disclose the allocation sequence generating process clearly, which raised questions about the quality of the randomization.

The quality of the reviewed studies varied, with many demonstrating robust methodologies and clear reporting, while others exhibited certain limitations. For example, several studies lacked clarity in the allocation sequence generating mechanism, raising questions about whether participant selection was appropriately randomized. This could affect how the studies are interpreted in general. Furthermore, performance bias may have resulted from certain studies’ failure to blind participants to the study, which may have affected their relationships or behaviors. Assessors’ knowledge of participants’ histories also constituted a risk, since it might lead to detection bias caused by prior information or expectations. The majority of the studies in our review received a “low” rating across the evaluated standards. This score suggests that the studies typically followed high methodological standards, resulting in minimal risks of bias from variables such as allocation concealment, blinding, and other relevant criteria.

A few studies also noted the issue of selective reporting bias. It is possible that these studies only included positive results or conclusions on particular assessments. This selective reporting may have restricted the findings’ comprehensiveness and skewed the overall interpretation. These quality assessments underline the importance of using more strict methodological standards in future research. Researchers should make sure that participant selection is random and maintain blinding wherever feasible to reduce detection and performance biases in order to increase the robustness of subsequent investigations. To lower the possibility of selective reporting bias, comprehensive and open reporting of all measurable outcomes should be emphasized.

Types of cognitive distortions

All-or-nothing thinking

This distortion is the tendency to see things in black and white without acknowledging any middle ground [50]. This CD appears to be a key element influencing moral judgments and acts in criminal circumstances [51]. It is distinguished by its inclination toward extreme and dichotomous thought patterns. According to Demeter and Rusu [31], there is a strong link between the seriousness of the offenses and the frequency of this CD and antisocial behaviors among those who commit crimes. Their findings show how all-or-nothing thinking becomes more intense as offense severity increases, providing insight into how people justify their behavior by using deception for their own benefit. Saladino et al. [42] provide further insights by highlighting the vulnerability that comes with all-or-nothing thinking, especially for those who struggle with insecure attachment patterns. Their thorough analysis highlights a troubling pattern in which those who are susceptible to this CD have a higher inclination towards participating in violent and risky sexual activities, underscoring the complex relationship between CDs and recidivism. This offers further evidence of the connection between violent conduct and all-or-nothing thinking. This synthesis contributes to a more thorough knowledge of the influence of CDs within criminal behavior paradigms by clarifying the intricate relationship between them and unlawful activities.

Overgeneralization

Overgeneralization is a distortion in which individuals form broad, sweeping judgments based on a single occurrence or inadequate evidence [18]. Individuals are misled into thinking that a single bad event is applicable to every situation in the future. It usually shows up as the generalization of single incidents to support ongoing criminal behavior in the minds of offenders. D’Urso et al. [29], for example, looked at male recidivist sex offenders and found that they had a propensity to generalize particular complaints—originating from interpersonal relationships or social interactions—into a distorted worldview that justified their continued criminal activity. Many offenders believed that their illegal behavior was a necessary reaction to a society that they believed to be inherently unfair because they regarded an individual’s unpleasant experiences as representative of a larger, unjust reality. This overgeneralization gave them a distorted view of their situation, supporting the assumption that personal failures or rejections supported their motivation for continuing to participate in criminal behavior.

Additionally, studies demonstrate how offenders’ perceptions of moral and social limits are distorted by overgeneralization. For instance, Haslee and Salina [34] addressed how offenders’ overgeneralization can lead to skewed perceptions of what society expects of them, particularly when they generalize isolated unpleasant experiences into the idea that social norms do not apply to them. Enabling offenders to defend their acts using sweeping, faulty interpretations of their surroundings, can further solidify criminal conduct.

In a more specific study, Guerrero-Molina et al. [33] looked at how overgeneralization might be used to explain violent conduct, specifically in intimate partner violence. In their study, offenders generalized limited experiences or misperceptions of gender norms into a larger, distorted belief system that justified violence against women. Offenders used flawed generalizations to continue their unlawful behavior by making excessively general inferences about social signals or encounters.

Jumping to conclusions

This CD entails drawing negative inferences without adequate evidence, in which individuals susceptible to this distortion could have suspicious and paranoid views, which could make them more likely to act defensively or aggressively, particularly in criminal circumstances [18]. Offenders who are prone to making snap judgments may quickly view neutral behaviors or interactions as threats, which can cause them to respond defensively or even aggressively in circumstances they regard as hostile [17]. Stalkers are particularly prone to this, mistaking neutral or accidental encounters for indications of personal interest, which encourages repeated contact [17]. Offenders feel justified in their acts because they perceive them as essential reactions to perceived rejections or provocations, which is a feedback loop established through this CD. Furthermore, the mistaken sensation of control or entitlement that results from these rash judgments could motivate offenders to intensify their behaviors, believing their acts have no repercussions and are morally justified [17]. This CD not only encourages impulsive decision-making, but it also confines offenders in dangerous behavior cycles and reinforces it as they attempt to justify their flawed beliefs.

Blaming others

This is a CD in which individuals shift responsibility for their actions onto external factors, justifying their participation in destructive behaviors [52]. Offenders frequently utilize this error of thinking to excuse their unlawful behavior, blaming people or external circumstances rather than accepting personal responsibility. Research shows that offenders frequently externalize guilt in order to justify their behavior. For example, Mohammad Rahim et al. [36] investigated male murderers in Malaysia and discovered that many of them transferred blame by pointing fingers at other influences—such as friends or spouses—for choices they made, including hiding the corpse. Similarly, Demeter and Rusu [31] and Siserman et al. [43] noted that those convicted of violent crimes often reframed their behavior as necessary responses to outside forces, claiming that their acts were a response to external demands.

Externalizing responsibility takes on a more sophisticated impact for individuals who have committed sexual offenses. These offenders frequently used perceived social standards as justifications for their misdeeds, shifting blame onto larger social narratives surrounding sexuality [40]. This distortion was further examined by Ngubane et al. [15], who found cases in which offenders used victim blaming as an explanation for their actions. Some participants stated that victims made the first move to engage in sexual activity, and one participant said he was innocent since the victim was allegedly not a virgin. These explanations show how offenders could alleviate their own guilt and defend destructive behavior by placing the blame on others.

Furthermore, Szumski and Bartoszak [44] discovered that people who commit sexual offenses against children had a higher prevalence of this CD than other criminal categories and non-offending men, with a positive relationship between distortion prevalence and recidivism risk. Offenders frequently exhibit a feeling of nonsexual entitlement within this framework, thinking they have the right to participate in actions that are socially or legally inappropriate. This criminogenic need exacerbates their propensity to place blame on others. Because of this distortion of reality, offenders are more prone to justify fraudulent actions by presenting them as legitimate reactions to imagined entitlements or external provocations.

Labeling

This distortion occurs when individuals describe themselves negatively in response to an unpleasant incident [18]. Making negative labels for oneself or other people can make one feel worthless and hopeless, which can make one more likely to commit crimes [39]. Adverse childhood experiences, including trauma, abuse, or neglect, frequently lead to psychopathological traits that mold a person’s sense of self and encourage CDs like labeling [35]. Labeling allows people to internalize negative self-perceptions, such as unworthy or inherently deviant, which become ingrained in their mental processes. With that, offenders may start to see their illegal activity as a natural manifestation of who they are rather than a conscious decision, this distorted self-identity serves to further entrench moral disengagement. Such labeling intensifies criminal inclinations since offenders use their self-perception to justify repeated misdeeds, which is consistent with persistent deviance. Pérez-Ramírez et al. [39] show a strong correlation between labeling and mental health symptomatology, implying that those who experience mania, depression, anxiety, or general psychological distress may be more prone to internalizing stereotypes from society. This internalization contributes to a complicated web of CDs that influence criminal conduct by lowering self-esteem and increasing self-stigma [41]. In particular, those who internalize negative labels may have heightened emotions of alienation and a skewed sense of self-worth, which can lead to a higher likelihood of committing crimes as a coping strategy or to validate unfavorable self-perceptions. All in all, labeling perpetuates damaging preconceptions and creates a vicious cycle of bad self-perception for both the people who label and the people who label others.

Control fallacies

This distortion refers to a skewed perception of one’s ability to alter circumstances in their lives, which causes people to feel excessively weak or unduly accountable for occurrences beyond their control [23]. In the context of criminal activity, this distortion might emerge as offenders see their activities as a necessary method of regaining control, especially when they believe external forces are conspiring against them [45]. By presenting criminal activity as a reaction to perceived injustices or unavoidable circumstances, this thinking system can minimize human responsibility and legitimize criminal behavior. Umusig et al. [45] suggest individuals with control fallacies frequently feel helpless over their surroundings, believing that their behaviors are affected by forces beyond their control rather than by autonomous decisions. This view may feed a vicious cycle of maladaptive ideas that perpetuate a sense of powerlessness; it is especially prevalent among offenders with a history of sexual crimes. Offenders with ingrained control fallacies are more likely to reoffend because their erroneous beliefs impede proactive coping mechanisms [37]. Furthermore, Umusig et al. [45] argue that cognitive indolence, which is defined by unexamined beliefs, aversion to self-reflection, and simplistic thinking, could exacerbate these control-based distortions. This way of thinking enables offenders to avoid more in-depth self-analysis, which strengthens their distorted feeling of control and justifies destructive behavior. These characteristics are commonly displayed by offenders who avoid accountability and pursue goals inconsistently, which further undermines attempts at real behavioral change.

Rationalization

This distortion aids people in rationalizing or defending their actions, ideas, or behaviors in a way that makes them appear more acceptable and logical [53]. Offenders with greater levels of rationalization are more likely to commit serious and ongoing crimes [49]. Martínez-Catena and Redondo’s [35] study of imprisoned persons convicted of child abuse discovered that low levels of CDs connected to sexual assault did not always reflect serious moral judgment impairments. Rather, their research revealed that offenders may have a complex schema of thought that allows them to justify their behavior while still being conscious of social norms.

Understanding rationalization is essential because of its association with recidivism. Rationalization increases the likelihood of committing future crimes by enabling offenders to maintain a skewed self-image [54]. The rationalization associated with criminal activity was identified by Jha and Dhillon [16] and Verkade et al. [47], who also discovered a negative correlation between these CDs and sociomoral reasoning. According to their research, offenders who exhibit significant rationalization tendencies are less able to effectively appraise how their actions affect victims and society, which leads to the continuation of illegal behaviors. In support of this argument, Wuyts et al. [48] draw attention to the negative effects of rationalization and other CDs on criminal behavior patterns. Their findings indicate that offenders with high levels of rationalization distortion are more likely to participate in criminal activity. This supports the notion that CDs can have a major impact on the beginning and continuance of criminal activity by showing that rationalization not only encourages immediate offending behavior but also contributes to the larger trajectory of crime.

Furthermore, Grady et al. [32] investigated the link between trauma, CDs, and criminal behavior in sexual offenders, demonstrating how offenders’ views of intimacy may be significantly distorted by rationalization, making detrimental behavior seem permissible. Their research demonstrated how reasoning may skew ideas about what constitutes healthy connections and relationships, which can result in actions that are detrimental. They discovered that those with a history of trauma were more likely to reoffend due to their greater levels of rationalization. According to the study, these offenders frequently had skewed perceptions of their behavior, viewing it as justified by their own arguments, which masked the truth of their crimes. These individuals typically reframed their behaviors as legitimate, creating a cognitive distance that concealed the harm inflicted, thereby perpetuating the cycle of offending. This link was further strengthened by Paquette et al. [38], who pointed out that sexual offenses—especially contact offenses—are closely linked to beliefs that support criminal activity. Their results demonstrated the widespread importance of rationalization in sustaining illegal activity by showing that offenders typically support ideas that promote rather than impede their acts.

Mental filtering

This CD entails dismissing the positive elements of a situation and concentrating only on its negative aspects [50]. A distorted view of reality and the reinforcement of negative thought patterns can result from this selective attention. According to D’Urso et al. [30], mental filtering plays a crucial role in sexual offenders’ conduct, and this CD is frequently caused by relational and psychological immaturity stemming from unpleasant childhood experiences. The development of healthy cognitive and social maturity may be impeded by these early negative experiences, which can lead to a distorted perception of reality where offenders focus excessively on perceived rejections, criticisms, and failures [14, 46]. For example, offenders may focus on times of rejection or prior traumas, using these negative factors to define their self-worth while ignoring any good input or connections that may provide a more balanced perspective. Further investigation, as demonstrated by research [55], demonstrates how the abuse cycle is sustained and how the shift from victimization to criminal activity is facilitated by skewed attention towards negativity. This emphasizes how socially taught habits, CDs, and emotional dynamics interact intricately to generate deviant behaviors. As a result, this CD makes it more difficult for the offenders to evaluate social interactions and relationships, which frequently exacerbates socioemotional deficiencies and distorted risk perceptions [46]. It can be challenging for offenders to acquire healthy emotional and social reactions when mental filtering is used to focus only on negative events. This increases the chance of reoffending by reinforcing a self-concept that excuses or rationalizes deviant activities.

Minimization

This CD arises when people minimize the significance of their acts or the repercussions of their choices [52]. Minimization is a type of defense used by offenders to mitigate their sense of responsibility or remorse for their acts. Steel et al. [49] demonstrate how CDs such as minimization contribute to criminal conduct by cultivating a mentality that minimizes the consequences of one’s actions. In this view, minimizing allows offenders to dismiss the gravity of their acts, which might support recurrent wrongdoing by avoiding critical self-reflection. As these distortions enable a self-justifying narrative, Steel et al. [49] further emphasize that those who have persistent CDs, including minimizing, may be more likely to engage in criminal conduct. This is especially noticeable when it comes to misbehavior and contact crimes when the offenders minimize harm in order to reduce internal conflict and defend their acts. Minimization is especially common among those convicted of online child sex exploitation when they minimize the harm caused by dismissing the significance of the criminal behavior or explaining it as less harmful.

Discussion

A thorough analysis of the body of research repeatedly demonstrates an extensive connection between criminal behavior and CDs. These distortions contribute to criminal behavior by obscuring reality, impacting decision-making processes, and impeding proper information processing about others. This study includes research from a number of nations, including the United States, Portugal, Italy, Spain, South Africa, Poland, Malaysia, Romania, Canada, India, the Philippines, Mexico, and Iran. Variations in research design, methodology, and assessment instruments used to quantify CDs may explain why CDs are identified and addressed differently across areas. These discrepancies emphasize the necessity of using standardized approaches to evaluate CDs, especially when formulating treatments intended to combat criminal conduct. Additionally, it is essential to comprehend these distinctions in order to use efficacious treatment approaches that are generalizable or adaptable to different contexts, especially in correctional facilities with diverse groups of people.

Impact of cognitive distortions on criminal behavior

The analysis shows that different CDs each have a distinct role in the continuation of criminal activity, with certain distortions affecting the types, frequency, and even severity of violations. All-or-Nothing Thinking frequently manifests in violent crime instances, as offenders interpret events in absolute, extreme terms and are trapped in situations they believe to be unchangeable or unbeatable [31]. This biased viewpoint allows limited opportunities for compromise or alternate responses, producing a tunnel vision that leads to fast escalation in conduct. Such binary thinking is consistent with impulsive, reactive decision-making, in which people defend drastic measures as the only practical way to deal with what they perceive to be a dire or dangerous circumstance [56]. Existing research supports the relationship between dichotomous thinking and high-stakes judgments, emphasizing the urgency with which offenders respond when they see no middle ground [42]. This cognitive rigidity not only encourages violent responses but also supports the narrative that makes their acts seem justified, therefore sustaining vicious cycles of serious criminal activity.

Overgeneralization is a common CD among repeat offenders, who frequently regard society as universally hostile and repressive, producing a sense of permanent estrangement and justifying continuing criminal activity [33, 34]. Offenders who have such a distorted worldview are able to rationalize their continued illegal activity by framing it as a legitimate response to a society that is fundamentally unjust. As offenders lose trust in social norms and boundaries, this distortion frequently leads to moral disengagement, which is consistent with other research that linked disillusionment with social standards to recidivism [57]. This review emphasizes how overgeneralization not only exacerbates disillusionment but also seems to desensitize offenders to violence, creating a mentality that makes repeated transgressions seem acceptable and weakening their remaining ethical constraints [29].

Jumping to Conclusions is commonly shown as a cognitive shortcut in which offenders hastily assess events as threatening or validate their illegal behaviors in the absence of tangible evidence [17]. This distortion is especially evident in circumstances of impulsive violence and harassment, as offenders frequently infer hostile purposes or justification for aggressiveness, resulting in preemptive and inappropriate acts [17]. This distortion creates a mental environment where offenders feel justified in acting on unsubstantiated beliefs, this distortion frequently leads to unnecessary escalation of conflicts. These findings are supported by earlier research on assumption-driven thinking, which shows that making snap judgments not only makes people more likely to act aggressively but also feeds a vicious cycle of heightened mistrust and vigilance [58]. As a result, the distortion produces a mental environment in which offenders often anticipate unfavorable or combative results, which makes them more willing to act on rash and reactive behaviors.

Putting the blame on others exposes a cognitive propensity to externalize accountability, where offenders frequently use social or interpersonal constraints to defend their behavior. This misperception is a reflection of a process known as neutralization, in which offenders believe they are passive participants in events that are controlled by other forces [15]. Our findings imply that this viewpoint reinforces criminal activity by sustaining a victim narrative, which is consistent with the criminological idea of diminished personal accountability [59]. By perpetuating the idea that their activities are motivated by necessity rather than free will, this distortion enables offenders to avoid feeling guilty [15, 43].

It is evident that long-term internalized negative identities lead to a criminal self-concept when offenders with bad childhood experiences exhibit Labeling and Mental Filtering [30, 39]. These offenders frequently identify with negative labels that support self-fulfilling prophesies of deviance because they have a history of trauma or psychological instability. This CD confirms other research that a criminal identity is shaped by early trauma [60, 61]. It also emphasizes how these identities persist throughout an offender’s life, influencing their self-perception. These distortions have a lasting effect by fostering a narrative that makes offenders believe they are prone to crime, which reinforces the cycle of criminal activity [41].