Abstract

Background

The delineation of clinical target volume (CTV) base on the correlation analysis between neck node levels of OCSCC has not been reported in detail. This study analyzes the correlations between the neck node levels in 208 cases of OCSCC, and aims to provide preliminary reference for the CTV delineation in OCSCC patients.

Materials and methods

The records of 208 OCSCC patients were retrospectively analyzed. The neck node levels were evaluated according to the 2013 updated guidelines. The Chi-square test and logistic regression model were used to analyze the correlation of each level.

Results

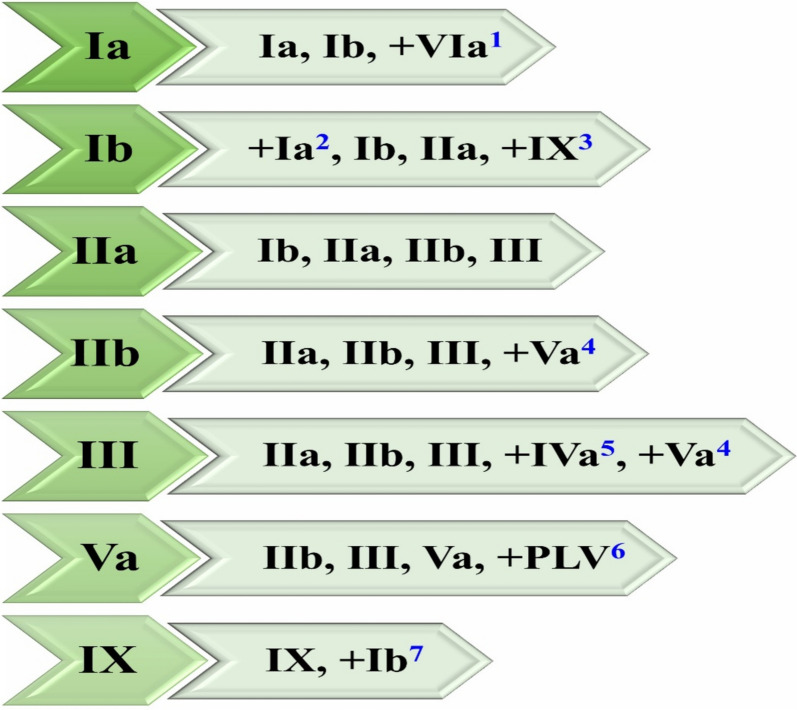

The most common involved level in OCSCC is Ib (45.7%) and IIa (40.4%). Correlation analysis of OCSCC showed that nodal spread in level Ia is related to levels Ib and VIa. Level Ib is related to levels Ia, IIa, IX. Level IIa is related to levels Ib, IIb, III. Level IIb is related to levels IIa, III, Va. Level III is related to levels IIa, IIb, Va. Level Va is related to levels IIb and III. Level VIa is related to level Ia and T stage. Level IX is only related to level Ib. T stage is only related to level VIa. All the above P values are < 0.05.

Conclusions

The related levels can be considered as high-risk region (HRR) and the unrelated levels as low-risk region (LRR) in the radiotherapy of OCSCC patients. This study can make the CTV delineation more individualized and accurate.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-024-13251-0.

Keywords: Oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma, Neck node levels, Lymph node metastasis, Correlation analysis

Introduction

OCSCC is the common malignancy in head and neck region [1, 2]. The lymph node metastasis rate of OCSCC is about 36–85% [3–7]. Some studies have reported the skip metastasis rate is very rare in OCSCC patients [8–14], which means the nodal spread of the next level is based on the involved levels, and we can reduce the risk of potential lymph node metastasis by irradiating the next levels which are related to the involved level. Recent study also reports to cover the next level as HRR [15]. The NCCN guidelines of radiotherapy for the head and neck cancers recommended covering the HRR and levels of suspected subclinical spread. The CTV delineation was mainly according to the N-stage and the lymph node metastasis rate [16], so the CTVs are basically consistent for the same N-stage patients, but even the same N-stage patients can present different metastatic levels. Two N1 OCSCC patients, one with isolated node in level IIa and the other in level III, should their CTV delineations be completely consistent? Two N2b OCSCC patients, one with nodes in ipsilateral level IIa and IIb, the other in level IIa, IIb, III, and Va, will there be any difference in the CTV delineations of the two patients? Dose the CTV delineation based on the lymph node metastasis rate underestimate the risk of certain levels with low metastasis rates? We think the correlation analysis of the neck node levels can clarify these issues. This study aims to analyze the correlations of different neck node levels and hopes to make the CTV delineation of OCSCC more individualized and accurate.

Methods and materials

Patient population

This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committees of the institutions participating in this study. The nodes were reviewed by an image board consisting of four senior radiation oncologists. Patients with positive lymph nodes were identified with the full agreement of all board members. We retrospectively reviewed the records of 208 OCSCC patients from February 2012 to December 2022. We separately evaluated the metastatic nodes of the two sides of each patient’s neck, which means we enrolled 416 neck sides (NSs) of the cervical lymph node metastasis data. According to the 2013 updated guidelines [17], levels Ib, IIa, IIb, III, IVa, IVb, Va, Vb, Vc, VIb, VII, VIII, IX, X and posterior to level V region (the region between trapezius muscle and scapular levator) (refer to as PLV region) were distinguished the left and right side, but levels Ia and VIa are not distinguished because they locate in the median region of the neck, so level Ia and VIa were separately included in the correlation analysis. The inclusion criterion is patients diagnosed as OCSCC with any T and N1-3 stage. The stages of all the patients were classified or reclassified according to the 8th edition of the AJCC/UICC TNM staging system. All the patients underwent MRI scanning of the oral cavity, the bilateral neck MRI scanning was also applied to detect abnormal lymph nodes. Some patients underwent a contrast enhanced CT simulation scan for radiotherapy.

Diagnostic criteria for the involvement of lymph nodes

The involved levels were evaluated according to the 2013 updated guidelines [17]. The diagnostic criteria for the nodal spread are based on the AJCC and previous study [18]. 1) Any node with a minimum axial diameter ≥ 10 mm, 2) Nodes of any size with central necrosis or a contrast-enhanced rim, 3) Nodes of any size with extracapsular extension, 4) Groups of three or more contiguous and confluent nodes with a maximum axial diameter of 8 mm, 5) Pathologically confirmed lymph nodes after surgery.

Statistical analysis

The Chi-square test (or Fisher’s exact test, if indicated) was used for univariate analysis. The logistic regression model with enter method (multivariate analysis) was used to evaluate the correlations between different neck node levels. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test was used to clarify the goodness of fit in logistic regression (p value > 0.05 showed good estimation of logistic model). Levels with less than a 3% metastatic rate in OCSCC were excluded in the univariate and multivariate analysis to avoid the bias. The SPSS 20.0 software was used to analyzed the data. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics and patterns of nodal involvement

A total of 208 OCSCC patients with 416 NSs of the neck involvement data were reviewed. There are 158 males and 50 females. The median age is 62 years old (range, 23–90 years old). The patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The most common metastatic levels in OCSCC are Ib (45.7%, 190/416), IIa (40.4%, 168/416), IIb (20.2%, 84/416). The levels with less than a 3% rate in OCSCC are IVa (2.4%, 10/416), VII (1.2%, 5/416), VIII (1.2%, 5/416), IVb (0.7%, 3/416), PLV region (0.7%, 3/416), Vb (0.5%, 2/416), and Vc (0.5%, 2/416). There is no nodal involvement in level VIb and X. The patterns of nodal involvement were summarized in Table 2. The results of univariate and multivariate analysis were summarized in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. The average p-value of Hosmer–Lemeshow test is 0.482. The supplementary Table 1 and 2 listed the results of Chi-square test and logistic regression for the levels with metastatic rate exceeding 3%, respectively. The metastatic level and related HRR was shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | OCSCC (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 158(76.0%) |

| Female | 50(24.0%) |

| Age (years) | |

| < 60 | 66(31.7%) |

| ≥ 60 | 142(68.3%) |

| Bilateral neck dissection | |

| Yes | 77(37.1%) |

| No | 131(62.9%) |

| Primary tumor site | |

| Lips | 3(1.4%) |

| Body of tongue | 56(26.9%) |

| Floor of mouth | 64(30.8%) |

| Upper gingiva | 4(1.9%) |

| Inferior gingiva | 21(10.1%) |

| Buccal mucosa | 45(21.6%) |

| Hard palate | 9(4.3%) |

| Retromolar trigone | 6(2.9%) |

| T stage | |

| T1 | 16(7.7%) |

| T2 | 67(32.2%) |

| T3 | 33(15.9%) |

| T4a | 81(38.9%) |

| T4b | 11(5.3%) |

| N stage | |

| N1 | 43(20.7%) |

| N2a | 3(1.4%) |

| N2b | 108(51.9%) |

| N2c | 46(22.1%) |

| N3a | 0(0.0%) |

| N3b | 8(3.8%) |

| M stage | |

| M0 | 204(98.1%) |

| M1 | 4(1.9%) |

| TNM stage | |

| III | 30(14.4%) |

| IVa | 157(75.5%) |

| IVb | 17(8.2%) |

| IVc | 4(1.9%) |

Table 2.

Patterns of nodal involvement

| Neck node level | 416 NSs (%) |

|---|---|

| Ia | 44(10.6) |

| Ib | 190(45.7) |

| IIa | 168(40.4) |

| IIb | 84(20.2) |

| III | 61(14.7) |

| IVa | 10(2.4) |

| IVb | 3(0.7) |

| Va | 13(3.1) |

| Vb | 2(0.5) |

| Vc | 2(0.5) |

| VIa | 36(8.7) |

| VIb | 0(0.0) |

| VII | 5(1.2) |

| VIII | 5(1.2) |

| IX | 13(3.1) |

| X | 0(0.0) |

| PLV | 3(0.7) |

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of neck node levels in OCSCC(p value)

| NNL | Variables | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ia | Ib | IIa | IIb | III | Va | VIa | IX | T-stage (T1 + 2 vs. T3 + 4) |

|

| Ia | — | 0.004 | 0.565 | 0.725 | 0.485 | 0.637# | 0.002# | 0.637# | 0.070 |

| Ib | 0.004 | — | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.022 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.048 |

| IIa | 0.565 | 0.0001* | — | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.008 | 0.667 | 0.041 |

| IIb | 0.725 | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | — | 0.0001* | 0.0001*# | 0.013 | 0.307# | 0.530 |

| III | 0.485 | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | — | 0.0001*# | 0.0001* | 0.107# | 0.073 |

| Va | 0.637# | 0.022 | 0.0001* | 0.0001*# | 0.0001*# | — | 0.003# | 0.058# | 0.494 |

| VIa | 0.002# | 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.013 | 0.0001* | 0.003# | — | 0.312# | 0.0001* |

| IX | 0.637# | 0.001 | 0.667 | 0.307# | 0.107# | 0.058# | 0.312# | — | 0.208 |

| T-stage(T1 + 2 vs. T3 + 4) | 0.070 | 0.048 | 0.041 | 0.530 | 0.073 | 0.494 | 0.0001* | 0.208 | — |

NNL Neck node level

* p < 0.0001, # Fisher’s exact test was used

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of neck node levels in OCSCC(p value)

| Dependent variables | Covariates | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ia | Ib | IIa | IIb | III | Va | VIa | IX | T-stage(T1 + 2 vs. T3 + 4) | |

| Ia | — | 0.008 | 0.137 | 0.545 | 0.583 | 0.926 | 0.015 | 0.919 | 0.203 |

| Ib | 0.006 | — | 0.0001* | 0.513 | 0.460 | 0.859 | 0.058 | 0.007 | 0.473 |

| IIa | 0.099 | 0.0001* | — | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.289 | 0.358 | 0.378 | 0.203 |

| IIb | 0.614 | 0.374 | 0.0001* | — | 0.001 | 0.025 | 0.959 | 0.837 | 0.259 |

| III | 0.839 | 0.577 | 0.0001* | 0.001 | — | 0.006 | 0.062 | 0.644 | 0.533 |

| Va | 0.773 | 0.818 | 0.829 | 0.044 | 0.009 | — | 0.365 | 0.305 | 0.676 |

| VIa | 0.015 | 0.057 | 0.965 | 0.882 | 0.064 | 0.140 | — | 0.634 | 0.004 |

| IX | 0.945 | 0.008 | 0.192 | 0.954 | 0.444 | 0.173 | 0.694 | — | 0.243 |

| T-stage(T1 + 2 vs. T3 + 4) | 0.213 | 0.522 | 0.139 | 0.351 | 0.471 | 0.653 | 0.004 | 0.316 | — |

* p < 0.0001

Fig. 1.

The metastatic level and related HRR (The left column represent the metastatic level, the right column represent the HRR). 1 The upper part of level VIa can be considered as HRR when level Ia was confirmed with nodal spread in OCSCC, especially in the advanced SCC of lower lip, anterior floor of the mouth, and anterior of inferior gingiva. 2 Level Ia can be considered as HRR for SCC of the lower lip, anterior floor of the mouth, and anterior of inferior gingiva if nodal spread is confined to level Ib. 3 The ipsilateral level IX can be considered as HRR for SCC of gingiva, especially buccal mucosa if nodal spread is confined to level Ib. 4 Level Va was correlated with ipsilateral level IIb and III, level Va can be considered as HRR in case of involvement of ipsilateral level IIb and III, especially IIb. 5 Level IVa and IVb should be covered as HRR in case of involvement of ipsilateral level III and IVa, respectively. 6 PLV region can be considered as HRR in case of involvement of ipsilateral level V, especially Va. 7 Level IX was only correlated with level Ib, which can be considered as HRR in case of involvement of ipsilateral level IX in the SCC of gingiva, especially buccal mucosa

Correlation analysis of neck node levels

Level I (Ia and Ib)

A total of 44 (10.6%) NSs had nodal involvement in level Ia. The univariate analysis indicated levels Ib ( = 8.120, p = 0.004), VIa (p = 0.002) were correlated with level Ia. Level Ia was correlated with level Ib (p = 0.008, OR: 2.636, 95%CI: 1.292–5.378) and VIa (p = 0.015, OR: 3.035, 95%CI: 1.245–7.397) in the multivariate analysis. The NSs with nodal involvement of level Ia synchronously had nodal spread in level Ib and VIa was 29 and 10, respectively.

A total of 190 (45.7%) NSs had nodal spread in level Ib. The univariate analysis indicated all the levels were related to level Ib (all p < 0.05), Level Ib was correlated with level Ia (p = 0.006, OR: 2.710, 95%CI: 1.325–5.545), IIa (p < 0.0001, OR: 2.898, 95%CI: 1.739–4.832), and IX (p = 0.007, OR: 17.527, 95%CI: 2.152–142.769) in the multivariate analysis. The NSs with nodal involvement of level Ib synchronously had nodal spread in level Ia, IIa and IX was 29, 106, and 12, respectively.

Level II (IIa and IIb)

There are 168 (40.4%) NSs had nodal involvement in level IIa. The univariate analysis indicated all the levels except Ia ( = 0.330, p = 0.565), IX ( = 0.186, p = 0.667) were correlated with level IIa (all p < 0.05), Level IIa was correlated with levels Ib (p < 0.0001, OR: 2.880, 95%CI: 1.714–4.840), IIb (p < 0.0001, OR: 24.447, 95%CI: 9.515–62.808), III (p < 0.0001, OR: 12.224, 95%CI: 4.120–36.267) in the multivariate analysis. The NSs with nodal involvement of level IIa synchronously had nodal spread in level Ib, IIb, and III was 106, 78, and 56, respectively.

There are 84 (20.2%) NSs had lymph node metastasis in level IIb. The univariate analysis indicated all the levels except Ia ( = 0.123, p = 0.725), IX (p = 0.307), and T-stage ( = 0.395, p = 0.530) were related to level IIb (all p < 0.05), Level IIb was correlated with levels IIa (p < 0.0001, OR: 23.099, 95%CI: 9.152–58.298), III (p = 0.001, OR: 3.518, 95%CI: 1.705–7.259), Va (p = 0.025, OR: 14.484, 95%CI: 1.405–149.341) in the multivariate analysis. The NSs with nodal involvement of level IIb synchronously had nodal spread in level IIa, III, and Va was 78, 40, and 12, respectively.

Level III

A total of 61 (14.7%) NSs had nodal spread in level III. The univariate analysis indicated all the levels except Ia ( = 0.487, p = 0.485), IX (p = 0.107), and T-stage ( = 3.221, p = 0.073) were correlated with level III (all p < 0.05), Level III was correlated with level IIa (p < 0.0001, OR: 11.299, 95%CI: 3.942–32.390), IIb (p = 0.001, OR: 3.553, 95%CI: 1.726–7.314), and Va (p = 0.006, OR: 26.785, 95%CI: 2.606- 275.340) in the multivariate analysis. The NSs with nodal involvement of level III synchronously had nodal spread in level IIa, IIb, and Va was 56, 40, 12, respectively.

Level Va

There are 13 (3.1%) NSs had nodal involvement in level Va. The univariate analysis indicated all the levels except Ia (p = 0.637), IX (p = 0.058), and T stage ( = 0.467, p = 0.494) were related to level Va (all p < 0.05). Level Va was correlated with level IIb (p = 0.044, OR: 10.777, 95%CI: 1.069–108.644), and III (p = 0.009, OR: 20.372, 95%CI: 2.136–194.270) in the multivariate analysis. The NSs with nodal involvement of level Va synchronously had nodal spread in level IIb and III was 12, 12, respectively.

Level VIa

There are 36 (8.7%) NSs had nodal involvement in level VIa. The univariate analysis indicated all the levels except IX (p = 0.312) were correlated with level VIa (all p < 0.05). Level VIa was correlated with level Ia (p = 0.015, OR: 3.014, 95%CI: 1.235–7.361), and T-stage (p = 0.004, OR: 4.983, 95%CI: 1.666–14.903) in the multivariate analysis. The NSs with nodal involvement of level VIa synchronously had nodal spread in level Ia was 10.

Level IX

There are 13 (3.1%) NSs had nodal involvement in level IX. The univariate analysis indicated only level Ib ( = 11.762, p = 0.001) was correlated with level IX. Level IX was only correlated with level Ib (p = 0.008, OR: 16.972, 95%CI: 2.079–138.553) in the multivariate analysis. The NSs with nodal involvement of level IX synchronously had nodal spread in level Ib was 12.

T-stage

The NSs with T1 + 2 and T3 + 4 stage is 166, 250, respectively. The univariate analysis indicated levels Ib ( = 3.894, p = 0.048), IIa ( = 4.196, p = 0.041), and VIa ( = 13.624, p < 0.0001) were correlated with T-stage. T-stage was correlated with level VIa (p = 0.004, OR: 4.997, 95%CI: 1.684–14.822) in the multivariate analysis. Among 36 NSs with lymph node metastasis in level VIa, 32 (88.9%) NSs were T3 + 4 stage.

Discussion

OCSCC is the common malignancy in head and neck region [1, 2]. Recent study has reported the correlations of nasopharyngeal carcinoma [19]. Nodes in OCSCC mainly drain into level I, II, III, and to a lesser extent of level IV, V, and other levels [7]. We separately analyzed each side of the neck because not all the OCSCC patients have the same metastatic levels in the two sides of the neck. Therefore, we believe it is more accurate and reasonable to enroll and analyze each side of the neck.

Withers HR et al. had reported the prophylactic irradiation dose of 50 Gy can effectively control the subclinical lesions [20]. The nodal involvement of OCSCC is rather consistent and follows orderly pathways [7]. The prevalence of skip metastases is rare in OCSCC patients [8–14], which is the precondition of this study, and there have correlations between the neck node levels. Theoretically, we can reduce the risk of potential lymph node metastasis by irradiating the related levels, and we can delineate CTV according to these correlations. We think the information of gross nodal spread can clarify these issues.

Level Ia is a median region locates between the anterior belly of the digastric muscles. Nodes in level Ia drain the skin of the chin, the mid-lower lip, the tip of the tongue, and the anterior floor of the mouth [17]. Murakami R et al. had reported the incidence of pathological node spread in level Ia is 6.7% (7/105) in OCSCC, and 57.1% (4/7), 28.6% (2/7), 14.3% (1/7) originated from SCC of lower gingiva, floor of the mouth, and tongue [21], respectively. Our study shows lymph node metastasis in level Ia also mainly originated from the SCC of anterior floor of the mouth, anterior of inferior gingiva, the tongue, and the lower lip, so level Ia can be considered as HRR for OCSCC patients invading these sites.

Many studies have reported level I and II is the most commonly involved region in OCSCC [22–25], which is consistent with our study. The incidence of occult metastasis in OCSCC had been reported to be between 18 and 50% [26–31], and the most common site of occult disease was to level Ib [22]. Nodes in level Ib are at greatest risk of harboring metastases from OCSCC [17]. Therefore, it is inappropriate to cover the ipsilateral level I and II as LRR, the ipsilateral level I and II, especially Ib, should always be considered as HRR in OCSCC.

Level II was subdivided into level IIa and IIb by the posterior edge of the internal jugular vein [17]. We recommend subdividing level III into IIIa and IIIb also by the posterior edge of the internal jugular vein because we found the OCSCC patients were more prone to have nodal spread in level IIa, which leads more prevalence of nodal involvement from level IIa to IIIa (Fig. 2). This is different from the patterns of nodal spread in nasopharyngeal carcinoma which have a propensity of drainage from level IIb to IIIb [32, 33].

Fig. 2.

Lymph node metastasis in level IIIa (white arrows) in a 69-year-old man with floor of mouth SCC. The red line represents the posterior border of the internal jugular vein

Level IV and V are not the routine drainage pathway of OCSCC. The prevalence of nodal spread to level IV and V is low, especially in level IVb, Vb, and Vc [13, 23, 24, 34–37]. We found all the 10 NSs with nodal spread in level IVa simultaneously had nodal involvement in level III, and all the 3 NSs with nodal spread in level IVb simultaneously had nodal involvement in level IVa, which means the lymph node metastasis of level IVa and IVb are based on the nodal spread of level III and IVa, respectively. The ipsilateral level IVa and IVb can be considered as HRR if nodal spread is confined to level III and IVa, respectively, which is consistent with the recent research [16]. Otherwise, the ipsilateral level IVa and IVb, especially IVb, can be considered as LRR or be omitted.

Grégoire V et al. had reported the involvement of ipsilateral level V is a rather rare event occurring in less than 1% of OCSCC, it almost never occurs in the contralateral level V [7]. Lim YC et al. reported the prevalence of metastases in level V was 5.4% (5/93) in oral and oropharyngeal carcinoma, and 80% (4/5) cases simultaneously had nodal spread in level II and III [34]. Our study showed the metastatic rate of level Va, Vb, and Vc was 3.1%, 0.5%, and 0.5%, respectively. Level Va was correlated with level IIb and III, which is consistent with the studies of nasopharyngeal carcinoma [19, 38]. As described in the recent study [39], lymph nodes arrange along the accessory nerve, which descends along the anterolateral side of the internal jugular vein after it exits the jugular foramen, and then passes through the sternocleidomastoid muscle to the deep surface of the trapezius muscle, therefore, the nodes can metastasize from level II to level V and PLV region along the accessory nerve, nodes in level V and PLV region are based on the nodal spread of level II, V, respectively. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma presents a preferential involvement of level V because the nodal spread in level IIb is more common [19, 33, 38]. However, OCSCC patients present a preferential involvement of level Ib rather than level IIb, that leads a much lower frequency of nodal spread to level V. Even the prevalence of nodal spread in level V is quite rare in OCSCC, we think the ipsilateral level Va can be considered as HRR when there is nodal involvement in level IIb in OCSCC patients. This is significantly different from the current research [16], which recommends to directly omit level V if only levels I to II are involved. Moreover, we think not all the level V can be omitted in OCSCC patients. Gutiontov S et al. reported level V can be safely omitted from the CTV in locally advanced oropharyngeal SCC without gross involvement in level V, but how many patients present with nodal spread in level IIb is unclear [40]. Recent studies have reported the PLV region is correlated with levels Va, Vb, and Vc [19, 38]. We found all the 3 NSs with nodal involvement of PLV region synchronously had nodal spread in ipsilateral level Va. Even the prevalence of nodal spread in PLV region is quite rare in OCSCC, we also think the ipsilateral PLV region can be considered as HRR when level Va was confirmed with nodal spread.

The treatment of level VIa can be considered in lower lip tumors and in advanced gingivo-mandibular carcinomas invading the soft tissues of the chin [17]. Zhang et al. reported the incidence of level VI in 1875 patients with surgically treated primary OCSCC was 0.69% (13/1875) [41], all the 13 patients with nodal spread in level VI had a pT3 + 4 tumor stage and simultaneously accompanied with nodal spread in level I. However, this report did not further clarify whether the 1875 patients included N0 stage, and whether level VI was VIa, VIb or both. Our conclusion is based on the N + patients, and there is no lymph node metastatsis in level VIb. Many studies have indicated that the rate of nodal spread does not significantly increase as tumor size (T-stage) increases [42, 43, 44]. Our study indicates T-stage is only related to level VIa. Among 36 NSs with nodal involvement in level VIa, 32 NSs were in T3 + 4 stage. Level VIa was correlated with level Ia and T-stage. In addition, we observed all the nodes in level VIa are located in the upper part of this region. The upper part of level VIa can be considered as HRR when level Ia was confirmed with nodal spread in OCSCC, especially in the advanced SCC of lower lip, anterior floor of the mouth, and anterior of inferior gingiva. Recent study also recommended to covering the upper half of level VIa in the radiotherapy of oral/oropharyngeal SCC [45].

Level IX contains the malar and bucco-facial node group, they are at risk of harboring metastases from cancers of the buccal mucosa, the skin of the face, the nose [17]. The ipsilateral level IX was recommended to be covered as LRR for the buccal mucosa SCC [16]. There are 13 NSs had lymph node metastasis in level IX, which mainly originated from the SCC of buccal mucosa (69.2%, 9/13) and gingiva (23.1%, 3/13), the NSs with nodal involvement of level IX simultaneously accompanied with nodal spread in level Ib is 12. Therefore, the ipsilateral level IX can be considered as HRR rather than LRR for SCC of buccal mucosa or gingiva based on our study, considering level IX was only correlated with level Ib, the ipsilateral level Ib can also be considered as HRR if nodal spread is confined to level IX in the SCC of buccal mucosa or gingiva.

The CTV delineation should not only be based on N-stage, but also take into account each specific involved level. Considering the existing studies indicated that reduction of the dose of radiotherapy to the elective neck in head and neck SCC had no significant differences in disease control or survival [46, 47, 48]. Therefore, our study does not recommend the optimal prophylactic radiation dose, but instead proposes the HRR and LRR based on the correlation analysis, we believe that it is more reasonable to reduce the radiation dose of the elective neck based on our study. In addition, it is inappropriate to directly omit the levels with low metastasis rate such as levels Ia, IVa, Va, VIa, IX, and PLV region, because the metastatic risk of these levels may significantly increase due to the related level was confirmed with nodal spread. The CTV delineation based on the lymph node metastasis rate can underestimate the risk of the levels with low metastasis rate. Unilateral treatment is recommended for N0-N2a lateralized tumors of upper and lower alveolar ridge, lateral floor of mouth and buccal mucosa [16]. Regardless of which side and level (unilateral and/or bilateral neck) of the neck accompanied with nodal involvement, CTV can consider to be delineated based on the correlations, so we didn't further to discuss the CTV delineation of unilateral and/or bilateral neck. Our study intends to give a preliminary reference rather than recommendations on the optimal strategy for the CTV delineation of OCSCC patients. Such a decision still depends on various factors such as the multidisciplinary head and neck tumor board and the relevant medical team responsible for taking care of the OCSCC patients. The supplementary Table 3 elaborates the differences of CTV delineation that was mentioned in the introduction of our study.

Limitations

First, this is a retrospective study and there is no follow-up data to support our conclusions. However, we are planning to carry out a series of prospective clinical studies based on these conclusions. Second, only 37.1% of the patients received bilateral neck dissection, but we think the neck dissection mainly affect the judgment of the occult lymph nodes not the diagnosis of the gross nodal involvement, and the purpose of this study is to clarify the correlations by analyzing the gross nodal involvement rather than the occult lymph nodes. Third, we excluded the levels with less than a 3% rate in the analysis to avoid the bias, so we need more samples to confirm the results of these levels in the future.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report about the correlations of neck node levels in the OCSCC patients, and we clarify which are the real HRR for each specific involved level. The CTV delineation was mainly according to the N-stage and lymph node metastasis rate, but patients with the same N-stage can present different metastatic levels, and the CTV delineation based on the metastatic rate may underestimate the risk of some levels with low metastasis rate. The related levels can be considered as HRR and the unrelated levels as LRR based on this study. It is inappropriate to perform a uniform standard to delineate CTV for all the OCSCC patients. We think the CTV delineation based on the correlation analysis of neck node levels can make it more individualized and accurate.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- OCSCC

Oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma

- CTV

Clinical target volume

- HRR

High-risk region

- LRR

Low-risk region

- NCCN

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- NSs

Neck sides

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- UICC

Union for International Cancer Control

- PLV

Posterior to level V region

- SCC

Squamous cell carcinoma

- OR

Odds ratios

- CI

Confidence interval

Authors’ contributions

Dr CY. Jiang had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: CY. Jiang. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: CY. Jiang, JW. Li, HB. Peng, DJ. Zhou, C. Xu, L. Zhang, Juan. Wang, BS. Liu, D. Li. Drafting of the manuscript: CY. Jiang. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: D. Li, and BS. Liu. Statistical analysis: CY. Jiang. Obtained funding: CY. Jiang and BS. Liu.

Funding

This research was supported by The Medical Science and Technology Project of the Health Planning Committee of Sichuan in China (21PJ068 to CY. Jiang) and the National Natural Science Foundation for Young Scholars of China (82104215 to BS. Liu). The funder had no role in designing of the study and drafting of the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable requests.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committees of the General Hospital of Western Theater Command and other Ethics Committees participating in this study. The written informed forms were exempted by all the Ethics Committees based on the retrospective nature of this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chaoyang Jiang, Daijun Zhou and Chuan Xu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Bisheng Liu, Email: lbs402889873@163.com.

Dong Li, Email: 13438078785@163.com.

References

- 1.Johnson DE, Burtness B, Leemans CR, Lui VWY, Bauman JE, Grandis JR. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):92. 10.1038/s41572-020-00224-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ettinger KS, Ganry L, Fernandes RP. Oral Cavity Cancer. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2019;31(1):13–29. 10.1016/j.coms.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mukherji SK, Armao D, Joshi VM. Cervical nodal metastases in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: what to expect. Head Neck. 2001;23(11):995–1005. 10.1002/hed.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindberg R. Distribution of cervical lymph node metastases from squamous cell carcinoma of the upper respiratory and digestive tracts. Cancer. 1972;29(6):1446–9. 10.1002/1097-0142(197206)29:6%3c1446::aid-cncr2820290604%3e3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah JP. Cervical lymph node metastases–diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic implications. Oncology (Williston Park). 1990;4(10):61–9 (discussion 72, 76). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah JP, Candela FC, Poddar AK. The patterns of cervical lymph node metastases from squamous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Cancer. 1990;66(1):109–13. 10.1002/1097-0142(19900701)66:1%3c109::aid-cncr2820660120%3e3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grégoire V, Coche E, Cosnard G, Hamoir M, Reychler H. Selection and delineation of lymph node target volumes in head and neck conformal radiotherapy. Proposal for standardizing terminology and procedure based on the surgical experience. Radiother Oncol. 2000;56(2):135–50. 10.1016/s0167-8140(00)00202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dias FL, Lima RA, Kligerman J, et al. Relevance of skip metastases for squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue and the floor of the mouth. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134(3):460–5. 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeitels SM, Domanowski GF, Vincent ME, Malhotra C, Vaughan CW. A model for multidisciplinary data collection for cervical metastasis. Laryngoscope. 1991;101(12 Pt 1):1313–7. 10.1002/lary.5541011210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo CB, Li YA, Gao Y. Immunohistochemical staining with cytokeratin combining semi-serial sections for detection of cervical lymph node metastases of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2007;34(3):347–51. 10.1016/j.anl.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng Z, Li JN, Niu LX, Guo CB. Supraomohyoid neck dissection in the management of oral squamous cell carcinoma: special consideration for skip metastases at level IV or V. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72(6):1203–11. 10.1016/j.joms.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park SM, Lee DJ, Chung EJ, et al. Conversion from selective to comprehensive neck dissection: is it necessary for occult nodal metastasis? 5-year observational study. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;6(2):94–8. 10.3342/ceo.2013.6.2.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lodder WL, Sewnaik A, den Bakker MA, Meeuwis CA, Kerrebijn JDF. Selective neck dissection for N0 and N1 oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer: are skip metastases a real danger? Clin Otolaryngol. 2008;33(5):450–7. 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2008.01781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warshavsky A, Rosen R, Nard-Carmel N, et al. Assessment of the rate of skip metastasis to neck level IV in patients with clinically node-negative neck oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(6):542–8. 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.0784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu Y, Wei Y, Wang J, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy for supraglottic cancer on real-world data: can we reduce dose to lymph node levels? Radiat Oncol. 2023;18(1):35. 10.1186/s13014-023-02228-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biau J, Lapeyre M, Troussier I, et al. Selection of lymph node target volumes for definitive head and neck radiation therapy: a 2019 Update. Radiother Oncol. 2019;134:1–9. 10.1016/j.radonc.2019.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grégoire V, Ang K, Budach W, et al. Delineation of the neck node levels for head and neck tumors: a 2013 update. DAHANCA, EORTC, HKNPCSG, NCIC CTG, NCRI, RTOG, TROG consensus guidelines. Radiother Oncol. 2014;110(1):172–81. 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van den Brekel MW, Stel HV, Castelijns JA, et al. Cervical lymph node metastasis: assessment of radiologic criteria. Radiology. 1990;177(2):379–84. 10.1148/radiology.177.2.2217772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang C, Gong B, Gao H, et al. Correlation analysis of neck node levels in 960 cases of Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). Radiother Oncol. 2021;161:23–8. 10.1016/j.radonc.2021.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Withers HR, Peters LJ, Taylor JM. Dose-response relationship for radiation therapy of subclinical disease. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31(2):353–9. 10.1016/0360-3016(94)00354-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murakami R, Nakayama H, Semba A, et al. Prognostic impact of the level of nodal involvement: retrospective analysis of patients with advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;55(1):50–5. 10.1016/j.bjoms.2016.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gurmeet Singh A, Sathe P, Roy S, Thiagrajan S, Chaukar D, Chaturvedi P. Incidence and impact of skip metastasis in the neck in early oral cancer: Reality or a myth? Oral Oncol. 2022;135:106201. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2022.106201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoda N, Bc R, Ghosh S, Ks S, B VD, Nathani J. Cervical lymph node metastasis in squamous cell carcinoma of the buccal mucosa: a retrospective study on pattern of involvement and clinical analysis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2021;26(1):e84-e89. 10.4317/medoral.24016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Pantvaidya GH, Pal P, Vaidya AD, Pai PS, D’Cruz AK. Prospective study of 583 neck dissections in oral cancers: implications for clinical practice. Head Neck. 2014;36(10):1503–7. 10.1002/hed.23494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pantvaidya G, Rao K, D’Cruz A. Management of the neck in oral cancers. Oral Oncol. 2020;100:104476. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.104476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norling R, Grau C, Nielsen MB, et al. Radiological imaging of the neck for initial decision-making in oral squamous cell carcinomas–a questionnaire survey in the Nordic countries. Acta Oncol. 2012;51(3):355–61. 10.3109/0284186X.2011.640346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christensen A, Bilde A, Therkildsen MH, et al. The prevalence of occult metastases in nonsentinel lymph nodes after step-serial sectioning and immunohistochemistry in cN0 oral squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(2):294–8. 10.1002/lary.21375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schroeder U, Dietlein M, Wittekindt C, et al. Is there a need for positron emission tomography imaging to stage the N0 neck in T1–T2 squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity or oropharynx? Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117(11):854–63. 10.1177/000348940811701111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pentenero M, Gandolfo S, Carrozzo M. Importance of tumor thickness and depth of invasion in nodal involvement and prognosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma: a review of the literature. Head Neck. 2005;27(12):1080–91. 10.1002/hed.20275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Matos LL, Manfro G, dos Santos RV, et al. Tumor thickness as a predictive factor of lymph node metastasis and disease recurrence in T1N0 and T2N0 squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;118(2):209–17. 10.1016/j.oooo.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dik EA, Willems SM, Ipenburg NA, Rosenberg AJWP, Van Cann EM, van Es RJJ. Watchful waiting of the neck in early stage oral cancer is unfavourable for patients with occult nodal disease. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;45(8):945–50. 10.1016/j.ijom.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cao C, Jiang F, Jin Q, et al. Locoregional extension and patterns of failure for nasopharyngeal carcinoma with intracranial extension. Oral Oncol. 2018;79:27–32. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X, Hu C, Ying H, et al. Patterns of lymph node metastasis from nasopharyngeal carcinoma based on the 2013 updated consensus guidelines for neck node levels. Radiother Oncol. 2015;115(1):41–5. 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lim YC, Koo BS, Lee JS, Choi EC. Level V lymph node dissection in oral and oropharyngeal carcinoma patients with clinically node-positive neck: is it absolutely necessary? Laryngoscope. 2006;116(7):1232–5. 10.1097/01.mlg.0000224363.04459.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naiboğlu B, Karapinar U, Agrawal A, Schuller DE, Ozer E. When to manage level V in head and neck carcinoma? Laryngoscope. 2011;121(3):545–7. 10.1002/lary.21468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dogan E, Cetinayak HO, Sarioglu S, Erdag TK, Ikiz AO. Patterns of cervical lymph node metastases in oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma: implications for elective and therapeutic neck dissection. J Laryngol Otol. 2014;128(3):268–73. 10.1017/S0022215114000267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDuffie CM, Amirghahari N, Caldito G, Lian TS, Thompson L, Nathan CAO. Predictive factors for posterior triangle metastasis in HNSCC. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(12):2114–7. 10.1097/01.mlg.0000182475.49177.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang C, Gao H, Zhang L, et al. Distribution pattern and prognosis of metastatic lymph nodes in cervical posterior to level V in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):667. 10.1186/s12885-020-07146-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang C, Li X, Zhang L, et al. The boundary of posterior to level V region and the theoretical feasibility of irradiation dose reduction of level Va in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):2308. 10.1038/s41598-024-52857-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gutiontov S, Leeman J, Lok B, et al. Cervical nodal level V can safely be omitted in the treatment of locally advanced oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma with definitive IMRT. Oral Oncol. 2016;58:27–31. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang S, Zhang R, Wang C, et al. Central neck lymph node metastasis in oral squamous cell carcinoma at the floor of mouth. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):225. 10.1186/s12885-021-07958-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haksever M, Inançlı HM, Tunçel U, et al. The effects of tumor size, degree of differentiation, and depth of invasion on the risk of neck node metastasis in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Ear Nose Throat J. 2012;91(3):130–5. 10.1177/014556131209100311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen YW, Yu EH, Wu TH, Lo WL, Li WY, Kao SY. Histopathological factors affecting nodal metastasis in tongue cancer: analysis of 94 patients in Taiwan. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;37(10):912–6. 10.1016/j.ijom.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jangir NK, Singh A, Jain P, Khemka S. The predictive value of depth of invasion and tumor size on risk of neck node metastasis in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity: A prospective study. J Cancer Res Ther. 2022;18(4):977–83. 10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_783_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu YC, Zhang X, Yang HN, et al. Proposals for the delineation of neck clinical target volume for definitive Radiation therapy in patients with oral/ oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer based on lymph node distribution. Radiother Oncol. 2024;195:110225. 10.1016/j.radonc.2024.110225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nuyts S, Lambrecht M, Duprez F, et al. Reduction of the dose to the elective neck in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, a randomized clinical trial using intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT). Dosimetrical analysis and effect on acute toxicity. Radiother Oncol. 2013;109(2):323–9. 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nevens D, Duprez F, Daisne JF, et al. Reduction of the dose of radiotherapy to the elective neck in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; a randomized clinical trial. Effect on late toxicity and tumor control. Radiother Oncol. 2017;122(2):171–7. 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nevens D, Duprez F, Daisne JF, et al. Recurrence patterns after a decreased dose of 40Gy to the elective treated neck in head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2017;123(3):419–23. 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable requests.