Abstract

Objective

To generate a scoping review that summarizes perceptions and attitudes of urology providers towards the transitional urologic care process. Likewise, summarize their identified barriers, facilitators, and ideal transition care for patients with genitourinary conditions.

Method

A systematic literature search was performed in Oct 2021. Records were identified for studies relevant to assessing urology specialists' practice variation, perception of barriers, and attitudes toward transitional care of patients needing life-long urologic care. The methodological quality of the cross-sectional studies was assessed using AXIS. The information extracted was clustered according to identified themes from the included studies. This scoping review was part of a systematic review registered on PROSPERO-(CRD42022306229).

Results

A total of 641 records were retrieved from electronic medical databases and cross-referencing. Ultimately, ten studies were included in this scoping review, conducted in the USA (n = 7), Canada, United Kingdom, and Italy. There is a wide variation in transitional care practices and preferences. However, the common themes extracted were: appropriate age to start the transition, additional training of the providers involved in transitional care, common transition plans, and practices, characteristics of multidisciplinary teams, potential barriers, areas of improvement, or facilitators for a better transitional process.

Conclusion

Common to all reports, multiple barriers are perceived. Areas that require improvement and multidisciplinary systems are needed to enhance urologic transition care. In addition, factors such as the age cut-off between pediatric and adult care or which specialist should handle specific procedures and conditions before, during, and after transition are still unclear and typically depend on the stakeholders.

Keywords: Transitional urologic care, Providers survey, Scoping review

Introduction

Transitional urologic care is a process in which both pediatric urologists and accepting adult specialists are involved in discussing the patient's medical condition, treatment goals, expectations, and future treatment plan before transferring the patient to an adult healthcare environment.1, 2, 3 It is recognized that the ideal model for this type of care should be customized to the specific healthcare system and involve all relevant stakeholders.4, 5 A well-coordinated transfer of care between pediatric urologists and adult specialists is crucial for the patient's lifelong urologic care.2, 6, 7, 8 However, to date, there is no established or widely recognized best model for urologic transitional care.

Currently, there is a need for a process that helps patients prepare and receive the information they need to succeed in adult healthcare. By identifying the issues and barriers perceived by both referring and accepting urology specialists, uncertainty can be reduced and the foundation for a clear and standardized transition program can be established. The purpose of this scoping review is to summarize the perceptions and attitudes of urology providers towards the transitional urologic care process, as well as their identified barriers, facilitators, and ideal transition care for patients with genitourinary conditions.

Methodology

A systematic literature search strategy was formulated with the assistance of a medical reference librarian specialist at the University of Alabama in Birmingham. In October 2021, a comprehensive search was performed on PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library (CENTRAL). This scoping review adheres to the PRISMA-ScR checklist9 and serves as preparation for the comprehensive systematic review protocol registered on PROSPERO (CRD42022306229). The search for grey literature was conducted on the ProQuest Dissertations and Global Thesis databases, and relevant review articles were tagged for cross-referencing to identify eligible articles. The search utilized keywords such as "Transitional care" and "Urology." The specific search strategy is detailed in Appendix A.

Pilot study – transitional clinic Toronto survey

The aim of this section is to present an overview of the pilot study conducted to assess the feasibility and potential impact of implementing a transitional urologic care program. The pilot study sought to explore the attitudes and experiences of both pediatric and adult urology providers in managing patients undergoing transition, as well as the challenges they encountered during this process. By conducting this pilot study, valuable insights were gained into the existing practices, perceptions, and gaps in transitional care, which can inform the development of more comprehensive and effective transition programs in the future. The following section outlines the key findings and implications of the pilot study, shedding light on the essential aspects of successful transitional urologic care.

In April 2022, the Urology team at The Hospital for Sick Children conducted a survey to assess the current practices, preferences, and perceptions regarding transitional urologic clinics. The survey was distributed during the University of Toronto's Robson Day, where a panel of accredited urologists was present. The survey was distributed to all attendees, regardless of their age, years of experience, specialty, and affiliation. The survey received 20 responses with 15 completed responses from urologists with an interest or experience in pediatrics, adult urological care, and the healthcare system in Toronto. The 20 responses were included in the analysis for validity assessment. In the future, the analysis will only include staff urologists. Appendix B shows the results of the survey analyzed, and a self-constructed validity assessment was performed. The majority of the urologists surveyed and residing in the Toronto area agreed that the transition process should start well before the patient turns 18 years old. This was identified as one of the most critical means of improving the transitional process10 (Appendix B). The current transition practices among adult urologists in Toronto revealed that approximately 40% of the respondents stated that their clinic accepts more than 75 new general referrals per month. However, 70% of respondents indicated they accepted only 10 or fewer new referrals from transitional care in the past year.

When asked about clinical scenarios involving 17–18-year-old patients with prior complex reconstruction procedures, the majority (60%) of the respondents recommended transferring these patients to an adult facility, rather than retaining them in a pediatric setting.11 Among the 15 respondents, when asked about the available specialists and allied professionals in their multidisciplinary teams, the following were reported: nurses (70%), nurse practitioners (10%), social workers (25%), psychologists (20%), physician assistants (45%), adult nephrologists (20%), and pelvic floor physiotherapists (1%)11 (Appendix B).

From the survey data, the team derived that the majority of the respondents suggested several facilitators for successful transitional care, including better access to a multidisciplinary team, the creation of a transitional clinic involving both adult and pediatric providers, regular and staged education for patients as they approach their 18th birthday, guidelines and clinical pathway configurations between adult and pediatric providers, and a centralized triage and transition referral system11 (Appendix B).

The survey findings provided valuable insights that served as the rationale for conducting the scoping review. By linking the survey findings to the scoping review, the aim was to explore and analyze existing literature that employed surveys or questionnaires to evaluate the practice settings, preferences, and perceptions of urology providers regarding the transitional care process for patients with congenital genitourinary or neurogenic bladder conditions requiring lifelong urologic care. The scoping review sought to assess the quality of care, identify barriers and facilitators, and gain a comprehensive understanding of the transitional care process.

The scoping review included ten studies that met the eligibility criteria. The studies were primarily conducted in the United States, with one study each from Canada, the United Kingdom, and Italy. The studies were assessed for quality using the AXIS appraisal tool, and their findings were grouped according to common themes such as the appropriate age to start the transition, additional training for providers, transition plans and practices, characteristics of multidisciplinary teams, and potential barriers and facilitators for a successful transition process.

The scoping review findings further supported and expanded upon the survey findings, providing a broader perspective by including studies from different regions and healthcare systems. The scoping review also addressed other aspects of transitional care, such as transition plans and practices. The included studies revealed variations in care models, with some programs lacking established care models for patients with congenital genitourinary anomalies. These findings underscored the importance of developing comprehensive and standardized transition plans and practices.

By conducting the scoping review, the aim was to gather evidence from a broader range of studies and synthesize the findings to provide a comprehensive overview of the available evidence on transitional care in urology. This allowed for a more robust understanding of the current practices, challenges, and potential solutions related to transitional care. The pilot survey findings served as an initial exploration of the topic, and the scoping review built upon them to provide a more extensive and evidence-based analysis.

Literature inclusion, screening, identification, and quality assessment

Studies that employed a survey or questionnaire to evaluate the practice setting, preference, and perception of urology providers regarding the transitional care process for patients with congenital genitourinary or neurogenic bladder conditions requiring lifelong urologic care were eligible for inclusion in the scoping review. This transitional care process, including the quality of care, barriers, and facilitators, was the outcome being assessed in the survey or questionnaire. Eligible study types included prospective, retrospective, and cross-sectional studies. Excluded records included qualitative studies, case reports, case series with less than 20 patients, review articles, and commentaries. Studies that reported transition care characteristics or long-term care needs described by a specialist provider without using a survey or questionnaire for quantification were also excluded.

Two reviewers were involved in the screening process of the records retrieved. Each reviewer independently screened, identified, and assessed the relevance of each record, followed by a full-text assessment. The included cross-sectional studies were then evaluated for quality of conduct and reporting using the AXIS appraisal tool from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).12 Additionally, a pilot study was included that assessed the validity of a self-constructed survey by evaluating the perceptions, practice variations, and preferences of 23 university-affiliated or community-based adult urology providers in the Greater Toronto Area regarding transitional care.

Data charting process and synthesis of results

The findings from the studies included were grouped according to common themes. One reviewer extracted the information, and the accuracy of the extracted data was verified by a second reviewer. Given the heterogeneity of the available studies, a statistical summary combining quantitative data was not feasible. As an alternative, a summary table of the findings from each study is provided to present an overview of the available evidence.

Result

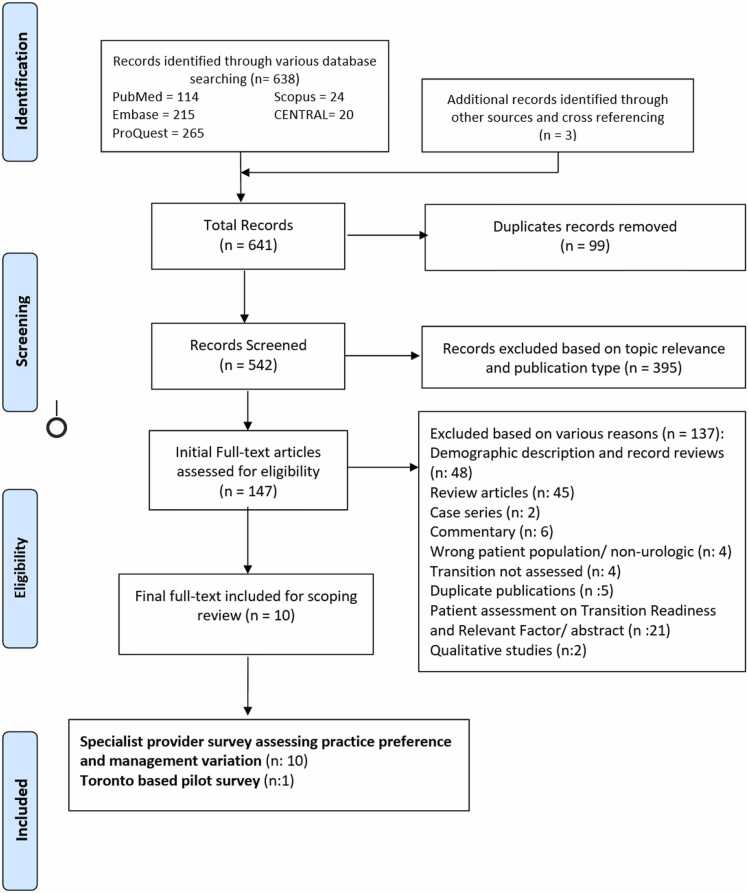

A total of 641 records were retrieved from electronic medical databases and cross-referenced from relevant articles. After duplicates were removed and eligible full-text articles were assessed, ten studies were included in the scoping review.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 11, 10 The PRISMA flow diagram details the literature identification process (Fig. 1). Additionally, a pilot study conducted by The Hospital for Sick Children was included to assess the validity of a self-constructed survey by evaluating the perceptions, practice variations, and preferences of Toronto adult urology providers in regard to transitional care.10

Fig. 1.

Modified PRISMA flow diagram for Scoping Review Literature Identification.

Study characteristics and quality assessment

The included studies in the analysis were conducted primarily in the United States (n = 7), with one study each from Canada, the United Kingdom, and Italy. A summary of the characteristics and key findings from each study is presented in Table 1. The quality of the studies was assessed using the AXIS quality assessment tool. The majority of the studies met most of the domains required for a good quality cross-sectional study. However, only a few studies were able to pilot their self-constructed survey or use a validated questionnaire. There was also a high rate of non-response, with most studies failing to address and categorize the non-responders due to the anonymous nature of the survey. Only four of the studies stated whether they were approved or exempt by the research review board. The quality domains of the studies are summarized in Table 2.

The findings from the studies were grouped according to common themes, including the appropriate age to start the transition, additional training for providers involved in the transition process, transition plans and practices, characteristics of multidisciplinary teams, potential barriers and facilitators for a successful transition process.

Age of transition

In 2019, Agrawal et al.21 assessed the experiences of urologic providers in transitioning spina bifida patients from pediatric to adult care. Out of 174 urologists, 79 responded to the survey, with the majority stating that the transition should occur at either 18 years old (24%) or 21 years old (22%).21

In a separate study, Wajchendler et al.17 investigated the Canadian Pediatric Urology landscape for spina bifida patient transitions to adult-centered care. A total of 28 surveys were completed, with 25 from full-time pediatric urologists and three from those practicing adult care. The suggested age to begin the transition process was 18 years or older, according to 43% of the respondents.17

However, Walker et al.14 conducted a survey among attendees of the annual British Association of Pediatric Urology meeting to determine the practices in the United Kingdom regarding the transition of pediatric urology patients. Of the 33 completed responses, 23 were from pediatric urologists and ten were from pediatric surgeons specializing in pediatric urology. When asked about the age of transition, the answers varied, but most transitioned their patients at 16 years of age.14

The analysis of the trends from the studies by Agrawal et al.,21 Wajchendler et al.,17 and Walker et al.14 provides insights into the varying practices and opinions regarding the transition of spina bifida patients from pediatric to adult care, particularly in relation to the age at which the transition should occur. It is noteworthy that these studies highlight the absence of multidisciplinary teams in some of the examined programs.

Agrawal et al.21 and Wajchendler et al.17 surveyed urologic providers and found different perspectives on the age at which the transition process should begin. Agrawal et al.21 reported that the majority of urologists believed the transition should occur at either 18 or 21 years old, while Wajchendler et al.17 indicated that 43% of respondents suggested starting the transition process at 18 years or older.

In contrast, Walker et al.14 conducted a survey in the United Kingdom and found that most respondents, including pediatric urologists and pediatric surgeons specializing in pediatric urology, transitioned their patients at 16 years of age. This discrepancy in the recommended age for transition reflects regional variations and different healthcare systems, illustrating the lack of consensus regarding the optimal timing for transitioning spina bifida patients.

Moreover, these studies shed light on the absence of comprehensive multidisciplinary teams in certain programs. While the focus of these studies was primarily on the age of transition, the lack of mention of multidisciplinary teams suggests that these programs may not have fully implemented a holistic approach to care for transitioning spina bifida patients. This raises concerns about the coordination of services, comprehensive evaluation, and addressing the multidimensional needs of patients during the transition process.

In summary, the analysis of these studies reveals divergent opinions regarding the age at which the transition of spina bifida patients should occur, ranging from 16 to 21 years old. Despite variations in geographic location and healthcare systems, studies assessing the transition of spina bifida patients from pediatric to adult care consistently highlight the significance of determining an appropriate age for transition. Additionally, the absence of explicit mention of multidisciplinary teams in some programs suggests a potential gap in providing comprehensive care during the transition process. Further research and collaboration among healthcare providers are needed to establish consensus guidelines for the age of transition and ensure the integration of multidisciplinary teams to optimize the care and support for patients during this critical period of transition.

Additional training of the provider(s) involved in transitional care

Szymanski et al.13 surveyed 62 members of the American Urological Association (AUA) and found that the majority (51.6%) believed that a general urologist would be most appropriate for long-term follow-up of patients with developmental delay. Some (25.8%) believed that urologists (either pediatric or adult) with an interest and training in managing these diseases would be optimal, while only a small percentage (1.6%) recommended primary care physicians to follow these patients. For patients with complex reconstructive surgeries such as bladder augmentation, catheterizable channels, and bladder neck procedures, 80.6% of the members recommended a urologist with an interest and training in adolescent or transitional care who routinely performs such procedures. In contrast, only 6.5% felt that general urologists were appropriate for providing long-term care.13

Roth et al.2, 22 surveyed the directors of pediatric urology (PU) and adult reconstructive (AR) fellowships to assess their opinions on the training required for caring for adults with congenital urologic conditions. 65% of PU directors and 90% of AR directors believed that specific training was warranted, but only 8% of PU directors and 20% of AR directors believed that general urologists had sufficient training. When asked if PU specialists had sufficient training, 85% of PU directors believed they did, while only 40% of AR directors agreed. When asked if AR specialists had sufficient training, 40% of AR directors thought they did, while only 39% of PU directors agreed.2, 22

Creti et al.20 conducted a survey that found that the ideal leader of the transition clinic should be a urologist specializing in functional or reconstructive surgery in the adolescent–adult population. Satisfaction with the institution's existing transitional care program was 55% among PU specialists and 40% among adult groups.20

The surveyed studies by Szymanski et al.,13 Roth et al.,2, 22, 23 and Creti et al.20 reveal a consistent commonality in the preference for specialized urologists with specific training and expertize in managing congenital urologic conditions and providing long-term care for patients with developmental delay. The findings highlight the importance of urologists with an interest and training in managing these diseases, particularly for patients requiring complex reconstructive surgeries. There is a consensus among healthcare professionals that specialized urologic care, rather than general urology or primary care, is optimal for long-term follow-up and successful transition of patients. The need for specific training in caring for adults with congenital urologic conditions is recognized, with an emphasis on the expertize of pediatric urologists and reconstructive specialists. These consistent findings emphasize the value of specialized knowledge and skills in ensuring optimal outcomes and patient satisfaction in the management of congenital urologic disorders.

Transition plans and practices

Varda et al.15 conducted a semi-structured interview with 20 leaders of adult urology divisions and found a wide range of roles for urologists in caring for adult patients with congenital genitourinary anomalies. The results showed a spectrum of care, from individual providers providing episodic care to comprehensive multidisciplinary care led by a urology team. Only three of the respondents had established a care model for these patients, while the others expressed an intention to develop one, but it was uncertain when this would occur.15

Kelly et al.18 evaluated Spina Bifida transitional care practices in the US using a validated survey from the National Cystic Fibrosis Center, which was adapted for Spina Bifida. Of the 27 respondents, 68% lacked a written protocol in the transitional care clinics and over 50% did not regularly evaluate their patients' processes. Additionally, fewer than 50% of pediatric urologists discussed changes in insurance coverage with their patients and 70% had no communication with adult providers in transitional clinics. There was also no evidence of discussions on reproductive issues, pregnancy, sexuality, or sexual function, with the focus instead being on mobility, bowel and bladder management, weight, alcohol, and drug use.18

Zilloux et al.16 studied the practice patterns and opinions on care for urologic transition patients among the Society of Pediatric Urologists, collecting 124 completed responses (53%) from 234 members. 32% of the respondents reported having a formal transition clinic. Patients could be seen by pediatric urologists (55%), adult urologists (16%), or by both (16%) during the same visit, or separately by both specialists (13%). When asked about the best providers for long-term urology patients, the majority (64%) felt that adult providers with a reconstructive (32%) or neurourology (27%) specialization were the best, while only 21% recommended pediatric urologists.16

Szymanski et al.13 surveyed 62 pediatric urologist members of the American Urological Association (AUA) out of 200, to collect their opinions on caring for mature former pediatric urology patients. Of the 67% of respondents who cared for adults with complex genitourinary conditions, 80.7% felt comfortable performing surgical procedures on older children, adolescents, and adults. However, for adult patients with genitourinary reconstruction with bladder stones, only 58.1% would treat them, while the rest would refer them to other specialists. 69.4% of pediatric urologists would refer their patients to a urologist with interest or training in such complex cases, but only 45.2% had such specialists available in their practice.13

Wajchendler et al.17 found that 68% of urologists had a transition process for adolescents and 54% personally provided ongoing care for spina bifida patients after transition from pediatric care. Most (82%) had identified or chosen a recipient adult or transitional urologist in the community to handle adult care, and these recipients included a discussion of sexual function in the transition plan. However, only 14% used standardized questionnaires in their transition clinic practices and 57% did not encourage patients to attend appointments independently as they grew older.17

Alford et al.19 surveyed 90 of the 200 members of the American Society of Pediatric Neurosurgeons (ASPN) to determine variability in transition care practices. 28.1% reported that their clinic saw both pediatric and adult patients, while 68.8% continued seeing patients into their twenties and 31.2% stopped seeing patients at 18. Of the ASPN members who only see pediatric patients, approximately a third of the respondents (53.7%) have a transition program in place for adult care, whereas one-third have no transition program at all.19

In a study by Walker et al.,14 the different urological conditions managed by members of the British Association of Pediatric Urology in their transition clinics were identified. The clinics would manage several common sub-groups of urological conditions, with hypospadias being the most frequently reported (94%), followed by posterior urethral valves (90%). Of the respondents, 33% transitioned their patients directly to dedicated adolescent urologists, and 73% had dedicated multidisciplinary teams and formal transition programs in place. However, only 55% of the respondents were able to refer locally.14

Agrawal et al.21 reported that adult providers typically include annual upper tract imaging (renal ultrasound) and serum creatinine in their routine evaluation of patients without acute conditions. If any urinary conditions or bladder emptying issues are detected during the transition, they preferred using urodynamics and cystoscopy for evaluation21.

The analysis of the trends in the studies by Varda et al.,15 Kelly et al.,18 Zilloux et al.,16 Szymanski et al.,13 Wajchendler et al.,17 Alford et al.,19 and Walker et al.14 provides insights into the current state of transition care for patients with complex urogenital conditions and highlights both the presence and absence of multidisciplinary teams in these programs.

The findings indicate that while some healthcare settings have recognized the need for comprehensive multidisciplinary care, many programs lack such teams. Varda et al.15 found that only a small percentage of adult urology divisions had established care models for patients with congenital genitourinary anomalies, and Kelly et al.18 revealed the lack of written protocols and limited discussions on crucial topics in transitional care clinics.

In contrast, studies such as Zilloux et al.16 and Walker et al.14 identified the presence of formal transition clinics and dedicated multidisciplinary teams, demonstrating the positive trend of implementing comprehensive care models. These programs involve various specialists, including pediatric and adult urologists, neurosurgeons, orthopedics, physical therapists, social workers, and more. The involvement of these professionals allows for a holistic approach to care, addressing not only urological aspects but also psychosocial and functional needs.

However, the analysis also reveals challenges in achieving optimal multidisciplinary care. Szymanski et al.13 found that a significant proportion of pediatric urologists lacked specialists with expertize in complex cases, leading to a higher referral rate. Additionally, Wajchendler et al.17 highlighted the underutilization of standardized questionnaires and a lack of encouragement for patients to attend appointments independently during the transition process.

Furthermore, Alford et al.19 showed a lack of transition programs in a third of the surveyed centers, indicating a gap in care continuity for patients moving from pediatric to adult settings. This absence of structured programs suggests a need for further development and implementation of transitional care models to ensure a smooth and comprehensive transition for patients with complex urogenital conditions.

In summary, while there are promising trends towards the integration of multidisciplinary teams and formal transition programs, the current landscape of care for patients with complex urogenital conditions still faces challenges. Efforts should focus on establishing and expanding comprehensive care models, enhancing communication and collaboration among healthcare professionals, and addressing the specific needs of patients during the transition process. By doing so, healthcare providers can improve the quality of care and support for this vulnerable patient population.

The multidisciplinary system

Agrawal et al.21 conducted a survey to assess the perception and integration of a multidisciplinary approach to managing the transition process, protocols, and tools used for urologic surveillance in patients with spina bifida. The study found that the involvement of neurosurgery or neurology (87%), social workers (84%), and orthopedics (73%) was necessary for effective multidisciplinary care in adult life.21

Creti et al.20 reported on the Italian experience with transitional care for patients with complex urogenital diseases as they transition from childhood to adulthood. They evaluated the transitional programs of 30 multidisciplinary groups, consisting of 20 pediatric groups and 10 adult groups. The survey results showed that a multi-specialized team was involved in 20% of pediatric and adult groups, with a urotherapist involved in 50% of adult groups and only 5% of pediatric groups.20

A survey conducted by Alford et al.19 among ASPN respondents revealed that only 81% of the 90 centers had a multidisciplinary spina bifida clinic. The most commonly reported specialists included neurosurgeons, orthopedics, urology, physical therapists, social workers, rehabilitation, orthotics, and wheelchair management. Less commonly reported specialists, represented by fewer than 50% of the centers, included gastroenterologists, nephrologists, obstetrics and gynecologists, developmental pediatrics, neurology, endocrinologists, nutrition, genetics, rheumatologists, and cardiologists.20

The analysis of the trends highlighted in the studies by Agrawal et al.,21 Creti et al.,20 and Alford et al.19 reveals important insights into the utilization of multidisciplinary teams in transitional care programs for patients with urogenital diseases, specifically spina bifida.

The study by Agrawal et al.21 emphasizes the significance of a multidisciplinary approach, indicating that the involvement of neurosurgery or neurology, social workers, and orthopedics is essential for effective multidisciplinary care during the transition to adult life. This suggests that the collaboration and expertize of various specialists are required to address the complex needs of these patients.

However, the findings from Creti et al.20 shed light on the variation in the existence of multidisciplinary teams. The study shows that only 20% of the evaluated pediatric and adult groups had a multi-specialized team involved in transitional care. Furthermore, the involvement of a urotherapist was more prevalent in adult groups (50%) compared to pediatric groups (5%). This indicates a potential discrepancy in the availability and implementation of multidisciplinary care, highlighting the need for increased emphasis on interdisciplinary collaboration across all stages of care.

The survey conducted by Alford et al.19 reveals that although 81% of the centers had a multidisciplinary spina bifida clinic, there were variations in the composition of these teams. Commonly reported specialists included neurosurgeons, orthopedics, urology, physical therapists, social workers, rehabilitation, orthotics, and wheelchair management. However, less commonly reported specialists, such as gastroenterologists, nephrologists, obstetrics and gynecologists, and neurology, were present in fewer than 50% of the centers. This indicates that while multidisciplinary clinics are established in a significant number of centers, there is room for improvement in incorporating a broader range of specialties to ensure comprehensive care.

In summary, the analysis highlights the importance of multidisciplinary approach and teams in managing transitional care programs for patients with urogenital diseases. The studies emphasize the need for collaboration or involvement among various specialists to address the complex needs of patients during the transition from childhood to adulthood. However, there are variations in the existence and composition of multidisciplinary teams with some specialties being more commonly reported than others, suggesting the need for further efforts to establish and optimize interdisciplinary collaboration in these programs. These findings underscore the significance of comprehensive and collaborative care, where different specialists work together to address the complex medical, functional, and psychosocial needs of patients during the transitional period. By incorporating a wider range of specialties and promoting consistent implementation of multidisciplinary care, healthcare providers can enhance the quality of transitional care and improve outcomes for patients with urogenital conditions.

Potential barriers

Agrawal et al.21 identified several potential barriers to transitional care including the lack of resources to organize and execute multidisciplinary spina bifida clinics and the inability to identify adult providers for the staff clinic (42%). Additionally, some staff members felt they did not possess the necessary skills for this type of care, while others reported a lack of support from leadership or felt it was not necessary to grow in those areas (∼19%).21

Varda et al.15 also noted that the financial burden and risk of providing high-resource utilization care with low compensation can be a barrier to transitional care. They also found that a lack of provider capacity and support from academic and hospital institutes could impact the quality of care. The authors suggest that this lack of support may lead to difficulties in obtaining adequate care.15

In the Toronto pilot survey, poor or insufficient access to pediatric health records, insufficient remuneration for congenital conditions in adult systems, a lack of communication channels between pediatric and adult urologists, and a lack of incentives and government support for adult transitional care were all identified as barriers.11

Areas of improvement, facilitators for better transitional processes

Agrawal et al.21 conducted a national survey and found that 22% of respondents believed that guidelines for the development of transition clinics were necessary. Additionally, 18% said that improved collaboration among providers was necessary, 15% believed that access and advocacy for transition clinics needed to be increased, 4–14% felt that provider and patient education was necessary, and 6–8% said that funding and resources for transition clinics should be consolidated.21

According to Zilloux et al.,16 some respondents recommended the development of new fellowships to care for complex patients, which should combine adult reconstructive and pediatric urology training. The study also found that respondents who worked in formal transition clinics rated the quality of care higher compared to those who did not work in such clinics. Moreover, those who were enthusiastic about caring for these patients were higher among those who worked in formal transition clinics compared to those who were not enthusiastic about working in such clinics.16

Discussion

The goal of healthcare management should be centered around the quadruple aim of improving population health, reducing the cost of care, enhancing patient experience, and improving provider satisfaction. This aim emphasizes reducing health inequities, but also requires addressing collaboration barriers and enablers.10 The American Academy of Pediatrics24 proposed that transitional programs should have a patient-centered and strength-based approach, emphasizing self-determination and independence while engaging caregivers, and acknowledging the differences and complexities of each patient. A focus on shared accountability and care coordination between pediatric and adult clinicians, as well as the healthcare system, was also emphasized.24

Transitional urologic care involves patients, social support groups, and providers. A separate scoping review was conducted to assess the patient's reported readiness, experience, and satisfaction with the transitional process.25 This scoping review, on the other hand, was designed to understand the provider's perspective in the current transitional process, including the barriers and facilitators to ensure successful transitional urologic care. A pilot survey was performed to validate it as a tool for broader dissemination, in preparation for a future pan-North American assessment of similarities and differences between Canadian and American practices, perceptions, and opinions on transitional urologic care. The data gathered in this scoping review was clustered according to the common themes yielded from the included studies.11

Extracted themes from the included studies

According to the Canadian Association of Pediatric Health Centers (2016), the target population for transitional care is youth aged 12–25 years old.26 As a result, some specialists in transitional urologic care recommend starting transition planning around age 12.3 However, the prior consensus among the American Association of Pediatrics (AAP), American Association of Family Physicians, and American College of Physicians suggests that patients who require long-term care or special needs should have an established transition plan by age 14 along with their families.27 Furthermore, the Canadian Pediatric Society's recent position statement emphasizes that preparing youth for transition must be a gradual process that increases their autonomy and recognizes changing caregiver roles.28 As such, they strongly advise against a fixed age cut-off between pediatric and adult care services, and suggest that the timing of transition should be determined based on each individual's developmental stage and capacity.28 In this scoping review, the perceived age of transition varied, with some individual respondents or studies implying a single age cut-off. However, it seems reasonable to tailor the transition age to the patient's intellectual and emotional maturity. We therefore advocate for individualized transition plans, and call for discussions at the health system level to address this lack of flexibility or to better prepare patients who may need to meet a narrow window.28

Based on thematic information regarding additional training requirements and appropriate providers for lifelong urologic care, most respondents stated that specialists with specialized training or a particular interest in treating patients' needs are the preferred members of the transitional urologic care team. Nonetheless, a multidisciplinary team was also described as crucial for helping patients navigate the difficult journey into adulthood and independence. This scenario is similar in other regions, where subspecialty and essential professions remain lacking.

All included studies and the Toronto pilot survey emphasized that barriers and facilitators are crucial and must be addressed to improve the transitional urologic care process. Most providers identified a lack of resources as the main barrier. In particular, the government's involvement in the health system is essential to provide better resources and better long-term health outcomes for this subpopulation.29 In the Toronto pilot survey,11 we found that incentives for transitional care are insufficient, leading to a low number of providers willing to participate in transitional care for patients with adult congenital genitourinary complex conditions. Directed resources for proactive transition preparation would likely result in reduced reactive healthcare costs, such as avoidable ER visits and complications, for poorly prepared patients who enter the adult system.

Facilitators or areas for improvement in the transitional urologic care process include guideline development and education opportunities for providers and related professionals. Increasing the expertize and availability of interested specialists would improve access and quality of care for the subpopulation in need of lifelong urologic care.

Despite a comprehensive literature search using a sensitive strategy, only six full-text articles were available.2, 21, 13, 16, 17, 19 To conduct a comprehensive scoping review, we included relevant abstracts that could provide additional information on the topic14, 15, 18, 20; However, the quality assessment was considered suboptimal. Additionally, we included results from our pilot study survey to compare and provide additional information on themes extracted from the available literature.11 Based on the AXIS assessment, most of the studies were considered of adequate quality, with many positive AXIS domains.30 However, a high proportion of non-respondents could introduce interpretation bias. It is worth noting that survey studies have the risk of low response rates and recall bias, and most studies could not identify the characteristics of the respondents due to the anonymity of the responses.

Implications for clinical practice and future research

This review does not aim to explain the differences or superiority of practices, but instead aims to characterize various practices and use them as a potential framework that could be adapted to the local context. The information gathered from this review provides valuable insights into the perspectives and opinions of urology providers and focuses on identifying common ground that aligns with the values and expectations of patients. Given the limitations of the health system structure and the variation in practices among providers, we encourage anyone planning to implement a transitional care model to consider evaluating the characteristics of their own practice, available expertize, and resources in order to build a multidisciplinary team that provides optimal long-term care for these subpopulations. Future studies should report the clinical outcomes of their patients, taking into account the specific characteristics of their transitional care model. This will help identify factors that can optimize the transition process across all specialties.

Conclusion

The number of patients with genitourinary conditions that require long-term care is on the rise, and the significance of transitional clinics is becoming more apparent. At present, there is a wide diversity of practices implemented in transitional clinics, ranging from pediatric to adult services. However, there is no globally standardized transitional clinic. This scoping review summarizes the perspectives of pediatric and adult urologists regarding their current practices in transitional clinics. The barriers, areas for improvement, and challenges in standardizing efficient practices and clinics have been identified.

The pilot study provided a brief overview of the transitional clinic process in Toronto, as well as the necessary changes to establish a more accessible, efficient, and consistent health system for pediatric and adult clinicians in Ontario. This is the first step in creating a more condense provider survey that will branch outwards to all of Canada and then internationally. By comparing thoughts and problematic areas between pediatric urologists and trainees to adult urologists, we will determine how willing the specialists will engage in the transitional process to help improve the future plans of pediatric patients with congenital urological conditions transitioning towards adult institutions.

Funding

There was no funding received or involved in conducting the study.

Ethical statement

Not applicable: Review protocol was registered with PROSPERO: CRD42022306229. All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of SickKids (REB#: 1000079334). REB approval was exempt for the scoping review.

Author contributions

All listed authors have made substantial contributions to the concept or design of the article and approved the version to be published. M Chua and LN Tse drafted the article or critically revised it for important intellectual content; JM Silangcruz, P Wang, J Dos Santos, A Varhese, N Brownrigg, M Rickard, A Lorenzo, and D Bagli were involved in the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the article as well as supervised the progress of the work.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

(Special Acknowledgment to Megan Bell, MLIS, AHIP | Assistant Professor, Reference Librarian & School of Health Professions Liaison, UAB Libraries | Lister Hill Library of the Health Sciences, Reference Department).

Appendix A. Search strategy

PubMed Retrieves 114

(((Discharge [tiab] OR transfer* [tiab] OR Transition* [tiab] OR hand-off [tiab] OR hand-over [tiab] OR handover [tiab] OR handoff [tiab]) AND care [tiab] AND adult [tiab]) OR "Transition to Adult Care"[Mesh]) AND (Urology* [tiab] OR urogenital [tiab] OR "Urology"[Mesh]).

Embase Retrieves 215

((discharge:ti,ab,kw OR transfer*:ti,ab,kw OR transition*:ti,ab,kw OR handoff:ti,ab,kw OR handover:ti,ab,kw OR 'hand off':ti,ab,kw OR 'hand over':ti,ab,kw) AND care:ti,ab,kw AND adult:ti,ab,kw OR 'transition to adult care'/exp) AND (urolog*:ti,ab,kw OR urogenital:ti,ab,kw OR 'urology'/exp).

Scopus Retrieves 24

TITLE-ABS-KEY ( ( discharge OR transfer OR transition OR transitional OR handoff OR handover OR 'hand AND off' OR 'hand AND over') AND care AND ( adult OR 'transition AND to AND adult AND care') AND ( urology OR urogenital)).

ProQuest Dissertations and Global Thesis databases Retrieves 265.

Transition and Lifelong Care in congenital urology.

CENTRAL: Retrieves 20 (1 included 19 excluded).

(((Discharge [tiab] OR transfer* [tiab] OR Transition* [tiab] OR hand-off [tiab] OR hand-over [tiab] OR handover [tiab] OR handoff [tiab]) AND care [tiab] AND adult [tiab]) OR "Transition to Adult Care"[Mesh]) AND (Urolog* [tiab] OR urogenital [tiab] OR "Urology"[Mesh]).

"Transitional Care"[Mesh] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh?term=Transitional+Care.

"Continuity of Patient Care"[Mesh] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh?Db=mesh&Term= %22Continuity%20of%20Patient%20Care%20%22[MESH].

Table 1.

Study characteristics and findings from the included studies.

| Author (Year) | Abstract (A), Partial Text (P) or Full-Text (F) | Source of Study | Study Objective | Targeted patient population described | Respondents/Surveys specialist- Characteristics | Number of Responders | Survey/Questionnaire | Remarks/Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syzmanski et al. (2015) | F | USA | To understand current practices and opinions regarding the management of adult complex genitourinary patients by pediatric urologists. | Complex genitourinary patients with conditions such as spina bifida, bladder exstrophy, cloacal exstrophy, cloacal anomalies, posterior urethral valves, or disorder of sex development. | Pediatric urologists that are members of the American Urological Association (AUA) | 62 (of 200 eligible) | Anonymous 15-question online survey to address practice patterns and opinions on the transition of care for patients with complex genitourinary conditions. Data collected includes practice type, years of experience, AUA section membership, and clinical scenarios to assess opinion on the most appropriate long-term follow-up provider. |

|

| Wajchendler et al. (2017) | F | Canada | To identify and analyze the medical practices and attitudes of Canadian pediatric urologists towards the care and transition of spina bifida patients. | Spina bifida patients | Canadian pediatric urologists who attended the Pediatric Urologist of Canada Association. | 28 of 37 eligible | 14-item survey addressing demographics, current practices, and attitudes towards the urological transition process of spina bifida patients. |

|

| Walker et al. (2017) | A | UK | To determine the current UK practices for the transition of pediatric urology patients. | Posterior urethra valves, hypospadias, bladder exstrophy, cloacal anomalies and disorder of sexual differentiation. | All consultant pediatric urologists, pediatric surgeons with urology sub-specialization and adolescent urologists who attended the British Association of Pediatric Urology meeting. | 33 responded | The questionnaire assessed the respondent’s specialization, regularly managed conditions that needed lifelong urology care, transition practices, age of transition and the presence of a transition program in their practice. |

|

| Kelly et al. (2017) | A | USA | To describe the current practices of transitional care services offered at Spina Bifida clinics in the US. | Adult Spina bifida patients. | Registered clinics via the Spina Bifida Association. | 27 clinics | The survey was adapted from the transitional care survey by the National Cystic Fibrosis center, which includes an assessment of 90 characteristics per clinic, including the transitional protocol, content of discussions during visits, and concept of long-term management. |

|

| Varda et al. (2018) | A | USA | To assess the perspectives of adult urology program leaders on their perceived role in caring for patients with congenital genitorurinary anomalies (CGA) and identify and barriers and facilitators to developing comprehensive care for these patients. | Adult patients with congenital genitourinary anomalies. | Adult urology program leaders (chairpersons or division chiefs). | 20 responded/45 contacted | Semi-structured interviews that evaluated the variability of practice and perceived role of care in adult programs for CGA patients. The interviews were approached using a framework that involved immersion with data, independent closed coding reports to identify convergence, divergence, and variation in themes as well as contextual meaning and connotations. |

|

| Zillioux et al. (2018) | F | USA | To characterize practice patterns and opinions regarding care for urologic transition patients. | Patients 18 years or older with complex congenital urologic conditions that impact their health long-term and into adulthood. | Members of the Society of Pediatric Urology listerv. | 124 responded/ 234 listed | Anonymous 20-question survey related to the respondent’s background, practice demographics, clinic structure, and quality. The survey used 5-point Likert scales to assess quality markers. |

|

| Alford et al. (2019) | F | USA | To identify the extent of variability and consensus in neurosurgical management of neurogenic bladder in patients with spina bifida. | Myelomeningocele with hydrocephalus, Chiari III malformation, and tethered spinal cord. | Members of the American Society of Pediatric Neurosurgeons (ASPN). | 90 responded out of 200 active ASPN members | A 43-question survey was distributed to the ASPN members to evaluate clinical case volume, newborn management, hydrocephalus management, transition to adulthood, clinical indications for shunt revision, Chiari II malformation decompression, and tethered cord release. |

|

| Agrawal et al. (2019) | F | USA | To summarize the perceptions of best practices for the care of adult spina bifida patients in North America. | Adult spina bifida patients. | Urology provider members in the Spina Bifida Association Network and members of the American Urological Association working group of Urological Congenital conditions. | 79 responded/ 174 invited | A self-developed electronic survey that assesses the urologic trend in current care. Additionally, it identifies the responders’ specialties and other specialties involved in their multidisciplinary team. Other major themes inquired were the responder’s perception and integration of multidisciplinary approach, protocols and tools used for urological surveillance, and transition strategies. |

|

| Roth et al. (2020) | F | USA | To survey pediatric urology fellowship directors and adult reconstructive fellowship directors to assess their views on who they believe has sufficient training to care for adults with congenital urologic conditions (ACUC). | Adults living with congenital urologic conditions (ACUC), including adults with posterior urethral valve, exstrophy-epispadias, prune belly syndrome, myelomeningocele, cloacal malformation, disorder of sexual development, hypospadias, vesicoureteral reflux and undescended testicles. | Pediatric Urology Fellowship Directors (PFD) and Adult Reconstructive Fellowship Directors (AFD). | 26/27 PFD, and 10/26 AFD responded | A 6-question non-validated online survey was used to assess attitudes towards optimal urology training for the care of ACUC. Information collected included prior fellowship training, and a multiple-choice questionnaire with free text responses was used to further express opinions on the training scenario that would satisfy the care for ACUC. |

|

| Creti et al. (2020) | A | Italy | To evaluate the state of the art of transitional care in Italy within pediatric group and adult group institutions. | Bladder exstrophy, posterior urethral valves, bilateral severe obstructive uropathies, neurogenic spina bifida, anorectal malformations and acquired medullary lesions were studied. | Pediatric multidisciplinary specialist groups and adult group institutions. | 20 pediatric groups and 10 adult groups responded |

A self-constructed 18-item multiple-choice questionnaire was used to inquire about the practice setting, transitional care model, clinical experience, and characteristics of the multidisciplinary team. Satisfaction was reported. |

|

| Chua et al. (2022) | P | Canada | To determine the perceived external barriers of adult providers/specialists and current practices of Toronto adult urologists in transitional care for patients with congenital genitourinary conditions perceived by the adult provider/ specialists that could affect their transitional care practices and to determine the current practice of the Toronto adult Urologists in handling patients with congenital genitourinary conditions. | Patients with complex genitourinary conditions (spina bifida, bladder exstrophy, cloacal exstrophy, cloacal anomalies, posterior urethral valves, metabolic stones or disorder of sex development) and require long term care. | Adult provider specialist/ Urologist in Toronto. | 15 of 20 eligible | 15-item pilot survey to assess survey validity and to inquire about the responders’ demographics, practice patterns, experiences, preferences, perception of barriers and facilitators, and clinical scenarios to identify the recommended model of the transitional process. |

|

Note: Study detail directly lifted from the study article for the accurate description of the included studies.

Table 2.

Appraisal of Cross-sectional Studies using AXIS assessment tool.

| Syzmanski et al. (2015) | Wajchendler et al. (2017) | Walker et al. (2017) | Kelly et al. (2017) | Varda et al. (2018) | Zillioux et al. (2018) | Alford et al. (2019) | Agrawal et al. (2019) | Roth et al. (2020) | Creti et al. (2020) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Introduction | ||||||||||

| Were the aims/objectives of the study clear? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Methods | ||||||||||

| Was the study design appropriate for the stated aim(s)? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was the sample size justified? | Yes | Yes | No | Don’t know | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Don’t know |

| Was the target/reference population clearly defined? (Is it clear who the research was about?) | Yes | Don’t know | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was the sample frame taken from an appropriate population base so that it closely represented the target/reference population under investigation? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was the selection process likely to select subjects/participants that were representative of the target/reference population under investigation? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Don’t know |

| Were measures undertaken to address and categorize non-responders? | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Were the risk factor and outcome variables measured appropriate to the aims of the study? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were the risk factor and outcome variables measured correctly using instruments/measurements that had been trialed, piloted or published previously? | Don’t know | Don’t know | Don’t know | Yes | Yes | No | Don’t know | Don’t know | No | Don’t know |

| Is it clear what was used to determine statistical significance and/or precision estimates? (e.g. p-values, confidence intervals) | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| Were the methods (including statistical methods) sufficiently described to enable them to be repeated? | Yes | Yes | Don’t know | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Results | ||||||||||

| Were the basic data adequately described? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Don’t know | Don’t know | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Does the response rate raise concerns about non-response bias? | Yes | No | Don’t know | Don’t know | Don’t know | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Don’t know |

| If appropriate, was information about non-responders described? | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Were the results internally consistent? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were the results presented for all the analyses described in the methods? | Yes | Yes | Don’t know | Don’t know | Don’t know | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Discussion | ||||||||||

| Were the authors' discussions and conclusions justified by the results? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were the limitations of the study discussed? | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Other | ||||||||||

| Were there any funding sources or conflicts of interest that may affect the authors’ interpretation of the results? | No | No | Don’t know | Don’t know | No | No | No | No | No | Don’t know |

| Was ethical approval or consent of participants attained? | Exempt | Don’t know | Don’t know | Don’t know | Don’t know | Yes | Exempt | Yes | Don’t know | Don’t know |

Appendix B. Pilot survey study results

| Which geographic area do you currently practice in? | Number | ||||

| Canada - Toronto | 18 | ||||

| Canada - London | 2 | ||||

| Current Role | Number | ||||

| Trainee- Urology Resident (PGY 3–5) | 2 | ||||

| Trainee- Urology Resident (PGY 1 / 2) | 3 | ||||

| Staff Urologist (3–5 years in practice) | 3 | ||||

| Staff Urologist (>5–10 years in practice) | 3 | ||||

| Staff Urologist (>10 years in practice) | 9 | ||||

| Area or intended area of focus/specialty (check all that apply) | Number | ||||

| General Urology/Community - Primary care Urology | 5 | ||||

| Uro-Oncology | 9 | ||||

| Pediatrics | 1 | ||||

| Infertility/ Andrology/ Sexual Medicine | 2 | ||||

| Urolithiasis | 4 | ||||

| MIS / Robotics | 4 | ||||

| Reconstructive Urology | 4 | ||||

| Functional Urology - Urodynamics | 2 | ||||

| Female Urology | 0 | ||||

| Transplantation | 2 | ||||

| Medical Urologist | 0 | ||||

| Other | 1 | ||||

| "Resident" | |||||

| Practice Setting | Count of Record ID | ||||

| Combined Part-time academic and community settings | 1 | ||||

| Full-time academic setting with a University affiliation | 18 | ||||

| Full-time community setting | 1 | ||||

| Percentage of patients within your practice aged 18 + with congenital genitourinary conditions | Number | ||||

| < 10% | 15 | ||||

| 11–20% | 4 | ||||

| 21–30% | 0 | ||||

| Other: | 1 | ||||

| "Resident" | |||||

| Number of new referrals for patients transitioned/transferred from pediatric care per year | Number | ||||

| < 10 | 14 | ||||

| 11–20 | 2 | ||||

| 21–30 | 2 | ||||

| Other: | 2 | ||||

| "NA" | 1 | ||||

| "Resident" | 1 | ||||

| Percentage of these new referrals accepted to your practice/clinic | Number | ||||

| < 10% | 8 | ||||

| 10–25% | 1 | ||||

| 26–50% | 1 | ||||

| 51–75% | 0 | ||||

| > 75% | 8 | ||||

| Other: | 2 | ||||

| "NA" | 1 | ||||

| "Resident" | 1 | ||||

| Does your practice have easy access to multi-disciplinary team? (Check all that apply) | Number | ||||

| Nurse | 14 | ||||

| Nurse Practitioner | 2 | ||||

| Social Worker | 5 | ||||

| Psychologist | 4 | ||||

| Physician Assistant | 9 | ||||

| Adult Nephrologist | 4 | ||||

| Other: | 4 | ||||

| "NA" | 1 | ||||

| "No" | 1 | ||||

| "Pelvic Floor Physiotherapist" | 1 | ||||

| "Resident" | 1 | ||||

| Please tell us about your perception about the current state of transitional care in Toronto and Greater Toronto Area (GTA) (in the past 3 years preceding the pandemic). | |||||

| Statements | Options | Number | |||

| Pediatric patients transitioning to adult urologic care have excellent access to adult providers. | Strongly Disagree | 3 | |||

| Disagree | 11 | ||||

| Neutral | 6 | ||||

| Agree | 0 | ||||

| Strongly Agree | 0 | ||||

| Most adult urologists accept referrals for young adults with congenital genitourinary conditions. | Strongly Disagree | 2 | |||

| Disagree | 11 | ||||

| Neutral | 6 | ||||

| Agree | 1 | ||||

| Strongly Agree | 0 | ||||

| The quality of urologic transitional care in GTA is excellent and consistent with guidelines. | Strongly Disagree | 2 | |||

| Disagree | 8 | ||||

| Neutral | 10 | ||||

| Agree | 0 | ||||

| Strongly Agree | 0 | ||||

| What are the barriers? Check all that apply | Number | ||||

| Communication between pediatric and adult urology | 11 | ||||

| Poor/insufficient access to pediatric health records | 13 | ||||

| Poor patient social supports | 10 | ||||

| Lack of pediatric transitional care initiatives | 10 | ||||

| Lack of adult transitional care initiatives | 11 | ||||

| Lack of government support | 11 | ||||

| Lack of dedicated billing codes for congenital diagnoses in adulthood | 8 | ||||

| Insufficient renumeration for congenital conditions in adult care | 12 | ||||

| Insufficient training in congenital urology adult care | 6 | ||||

| Patient financial support | 4 | ||||

| Prolonged clinic appointment length required | 8 | ||||

| Patient geographic location too far from adult provider | 4 | ||||

| Patient socioeconomic factors | 5 | ||||

| Other | 1 | ||||

| "Other" not listed | |||||

| Which of the following do you think would most improve urologic transitional care? Check all that apply. | Number | ||||

| Regular and staged education sessions for patients as they approach their 18th birthday (transitional care orientations) | 13 | ||||

| Education sessions for adult urology providers at annual meetings or institutional rounds | 5 | ||||

| Guidelines and clinical pathway configuration between pediatric urology and adult urology specialists | 12 | ||||

| Creation of transitional clinics involving both pediatric and adult providers | 14 | ||||

| Easier access to all relevant patient electronic medical records (Connecting Ontario, eCHN, EPIC, etc) | 10 | ||||

| Centralized triage and transition care referral system to liase with adult urology specialists | 12 | ||||

| Dedicated transitional care urologist(s) | 9 | ||||

| Increase government/healthcare funding and resources for setup and maintenance of transitional care | 9 | ||||

| Better access to multi-disciplinary care (i.e. social work, psychologist) | 13 | ||||

| Other | 0 | ||||

| Scenario Questions | For adolescent (14–17.5 y/o) pediatric urolithiasis cases with difficult upper tract anatomy that can be managed with either RIRS/PCNL, would you: | Number | |||

| Recommend transfer of the patient to adult facility for the planning and definitive procedure. | 12 | ||||

| Recommend the pediatric endourologist to proceed and perform the preferred procedure. | 7 | ||||

| Recommend to temporize the procedure (i.e. regular stent replacement, etc) and wait until eligible for transfer later. | 1 | ||||

| A 16 yr old male with neurogenic bladder s/p Casale stoma creation. He weighs 112 kg and on Solifenacin 10 mg daily. Due to excessive leak from channel - deflux INJ to channel trialed with repeat x 2 with short lived effect. Would you: | Number | ||||

| Optimize, do nothing and transition to adult urology for further decision on future reconstruction needs | 10 | ||||

| Apply for over-age exemption for revision of Casale before transition to adult urology | 6 | ||||

| Apply for over-age exemption for revision of Casale with bladder augmentation and transition to adult urology | 4 | ||||

| 16 yr female neurogenic bladder, 200cc bladder, leaks around catheter, wants cath channel. Mirtoff aborted for short appendix. | Number | ||||

| Optimize and transition to Adult urology for reconstruction planning of all procedures | 9 | ||||

| Proceed and perform Monti creation to be done at SickKids prior to transition | 8 | ||||

| Perform Monti creation and bladder augmentation all at SickKids | 3 | ||||

| For adolescents (16–17.5 y/o) unrepaired distal hypospadias with mild 30 degree curvature, who wanted to have surgical intervention, you would recommend the transitional urologists to: | Number | ||||

| Defer any repair and transition of the patient to adult healthcare facility | 10 | ||||

| Have the patient undergo hypospadias repair at pediatric facility | 7 | ||||

| Advise to inform patient that no repair is indicated (providing proper context) | 3 | ||||

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.Wood D. Adolescent urology: developing lifelong care for congenital anomalies. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;11(5):289–296. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth J., Elliott S., Szymanski K., Cain M., Misseri R. The need for specialized training for adults with congenital urologic conditions: differences in opinion among specialties. Cent Eur J Urol. 2020;73(1):62–67. doi: 10.5173/ceju.2020.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woodhouse C.R. Adolescent and transitional urology-an introduction. Adolescent urology and long-term outcomes. 1st ed. John Wiley & Sons; 2015. p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miles J.A. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2012. Management and organization theory: a Jossey-Bass reader. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holmbeck G.N., Kritikos T.K., Stern A., Ridosh M., Friedman C.V. The transition to adult health care in youth with spina bifida: theory, measurement, and interventions. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2021;53(2):198–207. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis J., Frimberger D., Haddad E., Slobodov G. A framework for transitioning patients from pediatric to adult health settings for patients with neurogenic bladder. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36(4):973–978. doi: 10.1002/nau.23053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood D., Baird A., Carmignani L., et al. Lifelong congenital urology: the challenges for patients and surgeons. Eur Urol. 2019;75(6):1001–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan R., Scovell J., Jeng Z., Rajanahally S., Boone T., Khavari R. The fate of transitional urology patients referred to a tertiary transitional care center. Urology. 2014;84(6):1544–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W., et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valaitis R.K., Wong S.T., MacDonald M., et al. Addressing quadruple aims through primary care and public health collaboration: ten Canadian case studies. BMC Public Health. 2020;20 doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08610-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chua METL, Dos Santos J, Varghese A, et al. Pilot study on the survey in assessing the practice variation, preference and perception of adult urology providers/specialist in transitional urologic care in Toronto. In: (SickKids) THfSC (Ed.); 2022.

- 12.Downes M.J., Brennan M.L., Williams H.C., Dean R.S. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS) BMJ Open. 2016;6(12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szymanski K.M., Roth J., Whittam B., Large T., Cain M.P. Current opinions regarding care of the mature pediatric urology patient. J Pediatr Urol. 2015;11(5) doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.05.020. 251.e1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker F.N., Srinivasan A., Wood D., Couchman A. Transitional care practice amongst pediatric urologists and surgeons in the UK. BAUS J Clin Urol. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varda B., Elmore C.J., Nelson C., McNamara E. Caring for adults with congenital genitourinary anomalies: adult urology department leaders' perspectives on programmatic change. J Urol. 2018;200(4S) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zilloux J.M., Johnson K.M., Johnson T.A., Miller C., McGeady J., Routh J.C. Caring for urologic transition patients: current practice patterns and opinions. J Pediatr Urol. 2018;14(3) doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2018.02.007. 242.e1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wajchendler A., Patel H., Koyle M.A. The transition process of spina bifida patients to adult-centered care: an assessment of the Canadian urology landscape. Can Urol Assoc J. 2017;11(1–2 Suppl):S88–S91. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.4338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly M., Tanaka T., Struwe S., Ramen L., Ouyang L., Routh J. Evaluation of spina bifida transitional care practices in the US. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2017;10(Suppl. 1):S47–S50. doi: 10.3233/PRM-170455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alford E.N., Hsiangbo B., Safyanov F., et al. Care management and contemporary challenges in spina bifida: a practice preference survey of the American Society of Pediatric Neurosurgeons. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2019;24(5):539–548. doi: 10.3171/2019.5.PEDS18738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Creti G., Mosiello G., Manzoni G., et al. First Italian report on transitional care for highly complex urological diseases from pediatric to adult. Eur Urol Open Sci. 2020:21. eS31. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agrawal S., Slocombe K., Wilson T., Kielb S., Wood H.M. Urologic provider experiences in transitioning spina bifida patients from pediatric to adult care. World J Urol. 2019;37(4):607–611. doi: 10.1007/s00345-019-02635-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roth J.D., Szymanski K.M., Cain M.P., Misseri R. Factors impacting transition readiness in young adults with neuropathic bladder. J Pediatr Urol. 2020;16(1) doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.10.017. 45.e1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roth J., Szymanski K., Ferguson E., Cain M., Misseri R. Transitioning young adults with neurogenic bladder—are providers asking too much? J Pediatr Urol. 2019;15(4) doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.04.013. 384.e1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White P.H., Cooley W.C., Transitions Clinical Report Authoring Group, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians Supporting the health care transition from adolescence to adulthood in the medical home. Pediatrics. 2018;142(5) doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chua M.E., Silangcruz J.M., Kim J.K., et al. Scoping review of neurogenic bladder patient-reported readiness and experience following care in a transitional urology clinic. Neurourol Urodyn. 2022;41(1):1–6. doi: 10.1002/nau.25021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.CAPHC . A guideline for transition from pediatric to adult health care for youth with special health care needs: a national approach. Canadian Association of Pediatric Health Centres & National Transitions Community of Practice; 2016. http://ken.caphc.org/xwiki/bin/view/Transitioning+from+Pediatric+to+Adult+Care/A+Guideline+for+Transition+from+Pediatric+to+Adult+Care Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 27.AAP, ACP-ASIM A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2002;110(27):1304–1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toulany A., Gahagan J., Harrison M.E., Canadian Paediatric Society, Adolescent Health Committee A call for action: recommendations to improve transition to adult care for youth with complex health care needs. Paediatr Child Health. 2022;27(2):88–91. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxac047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miles J.A. Management and organization theory: a Jossey-Bass reader. Absorptive capacity theory. Vol. 9. John Wiley & Sons; 2012. pp. 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 30.NIH. Study quality assessment tools. National Institute of Health (NIH); 2021 [updated July 2021]. Available from: 〈https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools〉.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.