Abstract

Introduction

The transition from pediatric to adult care poses challenges for adolescents and young adults (AYA) with chronic conditions and their caregivers. A patient navigator (PN) intervention may mitigate transition-related barriers.

Methods

A qualitative study was conducted within a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. A purposive sample was recruited of AYA with diverse diagnostic and demographic characteristics who worked with the PN and/or their caregivers. Seventeen participants completed semi-structured interviews at baseline and post-intervention and optional journal entries. Thematic analysis was used inductively.

Results

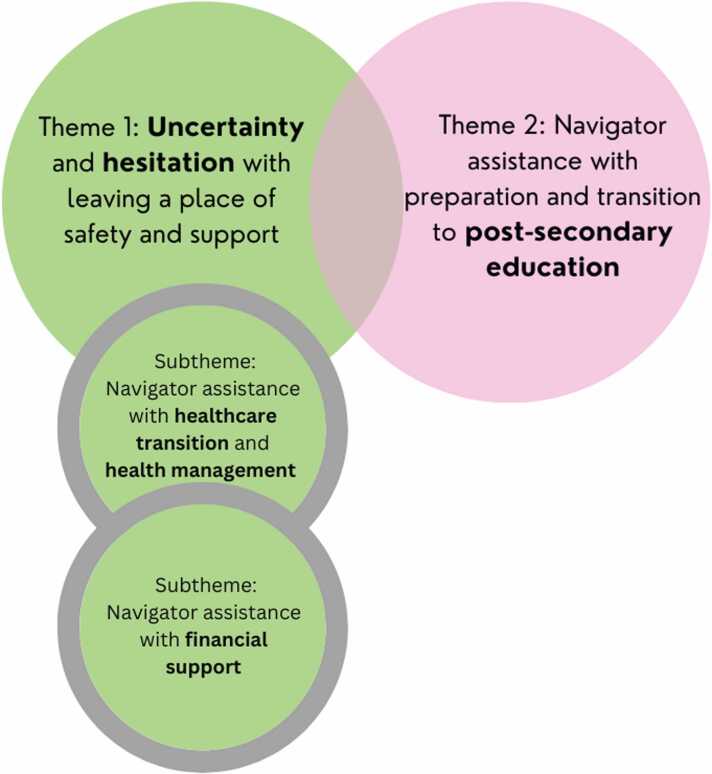

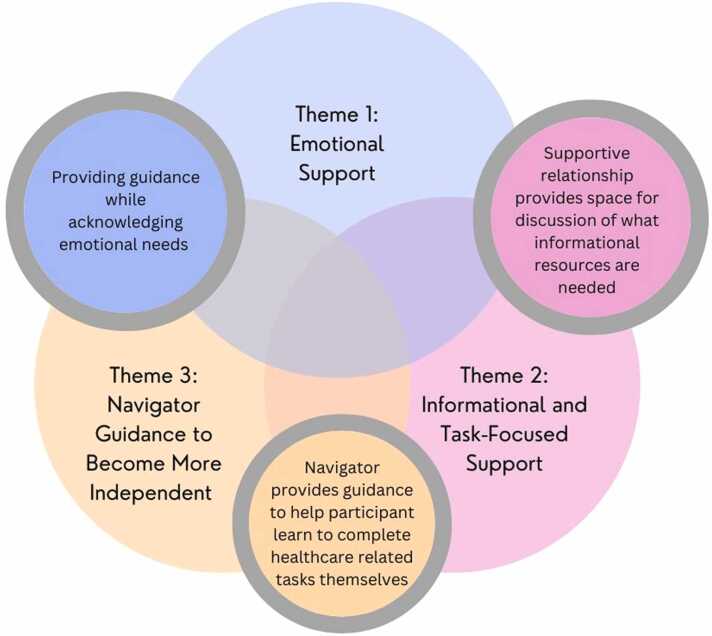

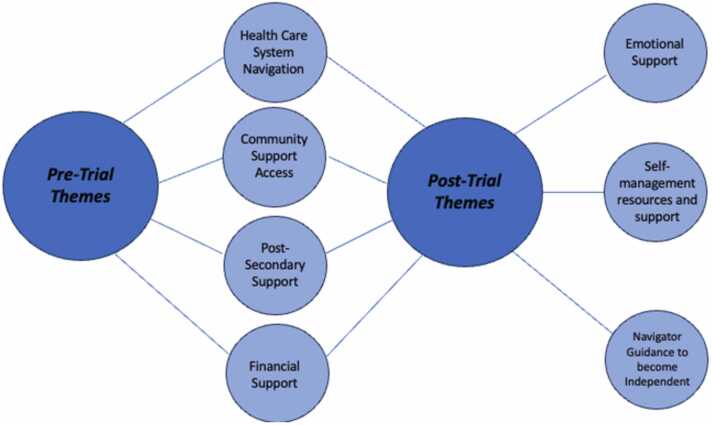

Analysis yielded two themes from baseline interviews: 1) uncertainty and hesitation with leaving a place of support, 2) navigator assistance with post-secondary education, and three themes from post-intervention interviews: 1) emotional support, 2) informational and task-focused support, 3) navigator guidance to become more independent.

Discussion

Our findings describe the needs of AYA and the experience of PN support; our findings may guide future implementation of PNs in transition care.

Keywords: Adolescent health, Transition, Transition to adult care

1. Introduction

The transition from pediatric to adult healthcare is associated with many challenges for adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with chronic health and mental health conditions 1. Although there are challenges specific to certain disease groups and individuals based on sociodemographic determinants, many are common 2. A systematic review identified common barriers AYA experience related to relationships, beliefs and expectations of the adult healthcare system, skills and/or efficacy, and access to care or health insurance-related barriers 2. AYAs experience simultaneous changes in other areas of life such as leaving high school and changes in interpersonal relationships. Developmental considerations further distinguish the AYA experience. While there are extensive individual differences, AYA may be more likely to engage in risky behavior or behavior with immediate rewards3. Thus, they may benefit more from external structure and support than adults, but the adult healthcare system does not typically treat AYAs differently. AYAs are often still developing self-management and interpersonal skills, which also affect their healthcare transition 4. A recent scoping review examined recommendations for improving transition from the perspectives of AYAs with chronic health conditions/complex health needs who have transitioned to adult care; recommendations included improving continuity of care, promoting patient-centered care, building strong support networks, and enhancing transition preparedness training 5. Caregivers of AYA with chronic health conditions face unique challenges by undergoing the transition with their child, as well as a transition in their own roles and responsibilities.

One proposed solution to improve AYAs transition to adult care is a patient navigator (PN). Patient navigators gained popularity in programs serving cancer populations 6 and have become widespread in other contexts, however, are often limited to disease-specific patient populations such as patients with type 1 diabetes 7, and hemoglobinopathies 8. A 2018 environmental scan identified 19 pediatric programs in Canada using navigators; the majority provided support to a group of patients with a specific condition such as mental health and addictions, diabetes, oncology or medically complex conditions 9. A more recent environmental scan identified 58 programs that included patient navigation in Alberta, with most available to patients of any age, though some were specific to children 10. Patient navigators have also been used in programs addressing disparities in health outcomes within marginalized groups 6, 11. Patient navigator support during transition has been shown to benefit clinical outcomes 8, 12, however the evaluation of PN from the perspectives of AYA who receive such services or their caregivers has not been well studied.

To address this gap, we conducted a qualitative study embedded within a larger randomized controlled trial, the Transition Navigator Trial (TNT), designed to evaluate the use of a transition PN with AYAs transitioning from pediatric to adult specialty care in Alberta, Canada 13.

2. Methods

Our objective was to ascertain the experiences of AYA with chronic health or mental health conditions and/or caregivers working with a PN throughout their transition to adult health services. Participants eligible for the study had a chronic health condition lasting over 3 months, requiring referral to an adult specialist 13. The trial was prospectively registered at clinicaltrials.gov NC-T03342495; full trial results will be reported elsewhere.

A province-wide pragmatic randomized controlled trial was conducted examining the impact of a patient navigator intervention compared to usual care for young people aged 16–21 with chronic conditions transitioning from pediatric to adult healthcare 13. Participants were enrolled between 25 January 2018 and 10 September 2021, and randomly assigned to either the PN or the usual care group. The PNs were social workers with clinical experience, employed by the provincial publicly funded healthcare system. The PN role was developed based on input from provincial healthcare stakeholders (direct care providers, administrators and policy makers) and recommendations from the transition literature 14. The intervention lasted 12–24 months. Patient navigators conducted an initial assessment with each participant, and contacted them every 3 months thereafter. Participants were able to initiate contact with PNs at any time by email, text, phone, and in-person. Participants assigned to the PN group were invited to participate in a qualitative interview at baseline (prior to beginning work with the PN). Those who participated at baseline were invited to complete a second interview at the end of the intervention, focused on obtaining reflections on how the PN assisted them during the trial.

Institutional ethics approval was granted for this study. Participants provided written or oral informed consent or assent (with parent/guardian consent), documented in writing by study staff. Consent was sought from a parent/guardian unless the mature minor participant declined to have their parent/guardian involved.

2.1. Participants and Sampling

Trial participants were recruited from specialty clinics at three tertiary care pediatric hospitals in Alberta, Canada. Eligible interview participants were trial participants assigned to the PN. In some cases, caregivers of a child who required additional support during the transition worked with the PN and participated in the interviews. This reflects the approach of the PN intervention to work with patients and their families. Interview participants were recruited using purposeful sampling strategy to ensure the sample was representative of the overall TNT cohort on the basis of primary disease category, sex, gender, presence or absence of comorbidities, and immigrant status15.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

Individual interviews were conducted by phone using a semi-structured interview guide by team members EM, BA, and DS. The interview guide was established in collaboration with content experts in transitions, chronic health conditions, and adolescent development. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim with identifying information removed. Data collection and analysis were iterative, and modifications to the interview guides were implemented when necessary. Data analysis occurred using NVivo software Version 11. Thematic analysis 16, 17, 18 was used to identify and analyze patterns in the data. Initial coding was done by three team members (MP, SS, DS). Through several rounds of discussion with the research team and qualitative methods expert (GD), codes were refined and combined to create themes and subthemes based on shared meaning 18. This process was completed while analyzing both baseline and post-intervention interviews; themes were then compared between time points.

Themes and subthemes were reviewed by the TNT steering committee; data was shared with all co-investigators and feedback was invited. Authors agreed that the information power of the sample was sufficient to address the research question 19. While the experiences of participants are diverse, the focus on the time period of transition, the purposive sampling strategy and depth of interviews led to rich and thorough data. Efforts to ensure trustworthiness in the analysis process included making changes to the interview guide, involving multiple coders, and providing reflexive memos and thorough descriptions of codes 17.

Participants had the option to share thoughts about their transition experience through an online journal at the time of enrollment and at 6, 12, 18 and 24 months post-enrollment. The journal prompt was an open-ended invitation to share thoughts in a free-text response box. Journal entries were analyzed using a general thematic analysis, and compared with the themes from the interview analysis. Within this cohort, 9 participants completed journal entries at various time points, for a total of 20 journal entries. Results from the analysis of journal entries agreed with the themes from the analysis of the interviews, thus they are presented together.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

Forty-six participants or caregivers were interviewed at baseline. Four subsequently withdrew from the study, and two did not have any interaction with the navigator. All remaining participants (n=40) who were interviewed at baseline were invited for a post-intervention interview. Some participants did not respond (n=16) or declined (n=7). The final sample represents 17 AYA participants. Interviews were conducted as follows: with AYA participants only (n=10), AYA participants supported by their caregivers during the interview (n=2) or caregivers only (n=5) when AYA were not able to participate in interviews themselves. The same person (participant and/or caregiver) was interviewed at both baseline and post-intervention. Participant demographics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographics.

| Interviewee (n=17) | |

| Participant Caregiver Participant and caregiver joint interview |

10 (59 %) 5 (29 %) 2 (12 %) |

| Age of AYA participant at baseline interview (n=17) | |

| 17 18 19 |

13 (76 %) 3 (18 %) 1 (6 %) |

| Sex of AYA participant (n=17) | |

| Female Male |

8 (47 %) 9 (53 %) |

| Ethnicity* (n=17) | |

| East Asian South East Asian Middle Eastern White/Caucasian (North American and European) |

2 (12 %) 1 (6 %) 2 (12 %) 15 (88 %) |

| Sex of caregiver interviewee (n=7) | |

| Female Male Did not respond |

5 1 1 |

| Referral site (n=17) | |

| ACH Stollery Glenrose |

6 (35 %) 9 (53 %) 2 (12 %) |

| Primary Diagnosis Category (n=17) | |

| Neurology Genetic/Metabolic Cardiovascular |

4 (24 %) 3 (18 %) 2 (12 %) |

| Developmental Hematology/Immune deficient Rheumatology GI/Liver Nephrology Endocrine Renal/Urology |

2 (12 %) 1 (6 %) 1 (6 %) 1 (6 %) 1 (6 %) 1 (6 %) 1 (6 %) |

| Number of clinics involved in care (n=17) | |

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

5 (28 %) 4 (22 %) 3 (17 %) 1 (6 %) 1 (6 %) 0 (0 %) 0 (0 %) 3 (17 %) 1 (6 %) |

| Presence of self-reported mental health conditions at baseline (n=17) | |

| Yes No |

6 (35 %) 11 (65 %) |

| Post-secondary aspirations at baseline* (n=17) | |

| Trade-school College/certificate University Work Prefer not to answer Other |

3 (18 %) 5 (29 %) 6 (35 %) 8 (47 %) 1 (6 %) 3 (18 %) |

| Vocational status at end of intervention (n=17)* | |

| College/certificate University High School Work Other community activities |

2 (12 %) 3 (18 %) 2 (12 %) 4 (24 %) 9 (53 %) |

Participants could select more than one answer, thus resulting in a total greater than 100 %

3.2. Themes and Subthemes

An overview of themes at baseline and post-intervention is shown in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, respectively. Supporting quotes are presented in Table 2.

Fig. 1.

: Baseline Themes.

Fig. 2.

: Post-Intervention Themes.

Table 2.

Baseline and Post Intervention Themes.

| Theme | Illustrative Quotes | |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||

| Theme 1 | Uncertainty and hesitation with leaving a place of safety and support | |

| Subtheme 1 | “I’m nervous about going in and I need support”: Navigator Assistance With Healthcare Transition and Health Management | "I guess like getting me ready to go there and…even if you can’t meet up for the first time, just go in there and just introduce yourself, get familiar with the doctors and then … she can help me with figuring out what kind of things I need to do when get to the doctor's office"(EDM−137) "Well I’m concerned with all my like, parking and stuff… Especially moving into a separate hospital. I wouldn’t know where I’m going and stuff, and some clinics will be in a different building … I know some of the doctors told me that some of their clinics will be like in downtown. And then in [Adult Hospital] and a different hospital again and different clinics" (CGY−064) “We try to go over to my mom’s original doctor that she goes [to]… but she doesn’t like my condition so she doesn’t want me to, she doesn't want to become my family doctor" (EDM−085) “You know the hardest thing for parents like me is finding actual care givers” (Caregiver CGY−080). "I think they would [be able to help] because I don’t really have a lot of access to, well, like adult providers like that other than like school. So it would help kind of get into it … because once I leave school, I would have that kind of outside as well." (EDM−078) |

| Subtheme 2 | “We are paying a lot out of pocket”: Navigator Assistance With Financial Support. | "Personally I may end up having an issue just with cost at some point … I don’t necessarily know what the future holds for me monetarily" (EDM−043) "Right and if I get a pump like depending on the pump that I get that may not be covered, I’m not currently on a pump but I do if I do get one there may be issues around that" (EDM−043) "I will probably need financial support because all the medications I am on, like we are paying, like right now my mom and dad are paying for them, but we are paying them, like some of the insurance pays for it, but we are paying a lot of it out of pocket" (EDM−137) "Will I have insurance?" (CGY−064) |

| Theme 2 | "I’m actually really nervous about going to university": Navigator Assistance with Preparation and Transition to Post-Secondary Education | “I think [my health condition] will affect me more in post-secondary” (CGY−064) “I will have to do a half course load and maybe help me transition to that … also keeping aware that I am in school and I have to keep up with it and keep up with my health” (EDM−137) "Cause like since I’m applying for college, I want to learn about ways that will make my life easier (laughing)… cause it’ll be hard to move around and stuff." (CGY−064) "Just the disability" (EDM−006) “might need help with the student loans” (EDM−006) “I’m actually really nervous about going to university, like taking, being in larger classes it might be little harder and maybe they’ll [patient navigator] help me transition in that as well.” (EDM−078) “figure[ing] out how to apply properly” (EDM−043) “I would like to be able to pay for my books and go to school” (EDM−085) |

| Post-Intervention | ||

| Theme 1 | “They’re always there”: Emotional Support | "It actually blew me away…she’s the first person to actually pick up a phone and go ‘hey, are you okay?’” (EDM−075, Caregiver) "And then I, she asked me how life was going and I kind of just poured my heart out on her cause, you know, I had this big connection with her and I asked her if she knew, if she could provide me with any help and she said yes, and she like started giving me, um, different resources to help" (EDM−137) "I also just like the fact that, um, they call me like, like it's more like a reassuring gesture. Like, oh, we are here if you are, if you need any help." (CGY−064) "Maybe it felt more like talking more to a human (laugh) not the doctors are inhuman but like it was kind of nice because she did sympathize with both sides …well informed about COVID but at the same time you know she was able to sympathize of how quarantine seems to have been, especially with still in school and things like that, so I really enjoyed that I thought it was kind of nice" (CGY−084) "If I needed something, she was there. I mean she’s been there more for me then any social worker or any doctor. " (EDM−075, Caregiver) "I think in my opinion, I think um, and probably same as [participant name], it was her biggest role was just the supportiveness. Mm-hmm. Like being able to, um, help us okay. Direct us which way to go or if there was a service that could help us with something, she was always there" (EDM−219, Caregiver) “[someone] who does understand, at least at some level the kind of stress and everything that does come along…with a chronic condition that kind of makes you an outlier in a lot of your friend groups and situations" (EDM−043) “made [the transition] easier and has reduced my stress significantly” (EDM−043, journal entry at 12 month time point). |

| Theme 2 | “She would look into it and get back to me”: Informational and Task-Focused Support | |

| Subtheme 1 | Healthcare and Community Resources and Support | “If it wouldn’t have been for my transition navigator kind of telling me what exactly had to be done, I wouldn’t have had a clue and I would have been fumbling through the system with supports not in place.” (EDM−047, Caregiver) "If the navigator contacted them, they got back to her immediately. So she was able to, if she was looking into something for me, she was able to get back to me within a day or two if I wasn't able to reach them. Um, and then she was able to get appointments or let me know if he's on a wait list for an appointment or already currently has an appointment. Whereas some of the other clinics, it was just, we, it took months to hear back from." (CGY−080, Caregiver) "Honestly it was amazing. I was trying to apply for my [government funding] and with the [PNs] help, I was finally accepted after how many years of trying, so it was really good" (EDM−006) "She gave me a lot of contact numbers and that for me to get a hold of different people, so that really helped because I think otherwise you'd just be… floundering if you didn't exactly know where to start" (EDM−149, Caregiver). “[Navigator] was very supportive that way when we were getting our paperwork in for guardianship and trusteeship, she was very good that way and helped us out, and talked me through it for some of the parts, so got me going." (EDM−149, Caregiver) “When I started my college program, she informed me [about] some things for people with like disabilities and stuff and like uh medical issues. So like for Cohn’s, there’s something for Crohn’s at the, at the college I went to…it was something that she brought to my attention cuz I didn’t know before we had our call” (CGY−095) “You name it. I mean, if I had a question, she’d figure it out.” (EDM−075, Caregiver) “If I had anything, questions in between, I could text them any questions I had and they would get back to me.” (CGY−092) "And I also got information on sexual health stuff at one point… cause that's super important as a diabetic." (EDM−043) "Sometimes it’s hard to find a lot of resources when it comes to specialist care so I think that was kind of like the best thing they provided was that they were able to find and access you know… certain resources and again like if was medications and stuff I didn't really know where to find they were really good about being able to do that." (CGY−084) "I had specific medication that I have to take and it isn’t covered by health care but they had a bunch of resources to, you know, to tell me like who to call and who to write a letter to get it covered by health care and things like that so that was really good too." (CGY−084) "She gave me numbers for if I felt suicidal or anything like that. She, um, she, she gave me numbers to contact if I ever felt like that. And she provided phone numbers to call for therapists and counselors to call and she said, call your family doctor, they've gotta have someone that, you know, they send their patients to and um, you know, look in the community to see if there's any therapists that you can see. And, uh, that helped a lot. That she was also there for my mental health and not just my physical health.” (EDM−137) "I would say [their role] was largely to provide support on topics or ways that other people in my life couldn't or at least she could do it more easily than having to reach out to someone like my [specialist] who was always super busy." (EDM−043) “She set me up with a guideline with exactly how to apply for uh trustee ship, guardianship…um how to apply for [provincial funding program] how to get [provincial funding program] going for [child’s name]… She even set me up like with a timeline of this has to applied for by this date and after you can, you can’t apply for this until this is done, so this is step one when step one is done you got step two, and to have that in place, because I wouldn’t have - nobody sits down and tells you these things, so without a navigator telling me these things there was no doctor that told me, no teacher, no educator that told me everything that had to be involved with my special needs child turning eighteen.” (EDM−047, Caregiver) |

| Subtheme 2 | Self-Management Resources and Tools | “It was a very useful tool” (CGY−078). “They shared like different apps I could use or different resources.” (CGY−092) “They helped me with tools on your phone. Like writing down notes of what medications you have, so you always have those things … [and] an app that you can write lists in of like what prescriptions you’re on, when you take them, and like what doctors’ appointments you had recently.”(CGY−078) |

| Theme 3 | “I used every method she taught me. It worked”: Navigator Guidance to Become More Independent: | "They really helped me improve, like how to book appointments, how to get the medication, how I can talk about my condition… past history, medications and just everything like medically involved…So they really helped me like have the confidence to call the doctors and then follow up if I need appointments, if I need anything, like getting a taxi or like getting prescriptions, anything like that." (CGY−064) "It helped me a lot and it helped me become more independent as a person, just not in my medical, um, aspect of life, but my regular day to day life … I'm just like this more confident, self-confidence, independent person now because of her"(EDM−137) "The transition navigator …said like ‘talk to your doctors and let them know like you get out of class around like 3:30 so have them call you with your appointments around 4:00 before somebody leaves like set up a system that works for you’"(CGY−078) "Yeah having like the goal setting and stuff like these things are going to do in the next week or the next couple weeks to months and so on, so you sort of have these periodic goals that you can accomplish and talk about with them with the next meeting."(CGY−084) "I told her I was very nervous for my very first appointment with an adult provider. And she basically, we sat down and we just talked it through. She taught me, okay, this is what you need to do. You need to advocate for yourself. Tell them what's going on, tell them what you've been doing for the last two years. Tell them what needs to happen with the rest of your, um, with the rest of your health. Right? Because not everything gets translated from pediatrics to adults and you have to relay all the information. And she told me, cause I didn't know all of my history with my family, she said, you need to get with your mother and you need to get all the information. So that's what I did." (EDM−137) "She helped me write everything out what I should be saying on there. She's like ‘tell nothing but the truth. But also make sure you are seeing what your worst days are’…And so I did that and it's still an application but you know, it helped me be realize, okay, this is what I need to do for any other applications in the future for other providers" (EDM−137) |

3.2.1. Baseline Data: Perceptions of how the Patient Navigator Will Help them Transition

3.2.1.1. Theme 1: Uncertainty and Hesitation with Leaving a Place of Safety and Support

Before the intervention, a majority of participants anticipated requiring a range of support from the PN during the trial to assist them through their transition to adult services. Nevertheless, some participants were uncertain about what specifically the PN could do to assist them through this transition period, leading to participants describing their goals or articulating when they would cease requiring support: "When I feel like I’m strong enough to be by myself. And … have learned as much as I can from them…like I’ve become the teacher of my own life. Then I feel like I'll be ready" (CGY-078).

3.2.1.1.1. Subtheme 1.1 “I’m nervous about going in and I need support”: Navigator Assistance with Healthcare Transition and Health Management

Several participants recounted their worries about the transfer and relocation to adult healthcare facilities. Consequently, many participants thought it would be helpful for the PN to physically accompany them to initial adult appointments while assisting them with mapping out the locations and routes to take to access such services. Participants also identified requiring assistance with acquiring a family doctor, adult specialists, and supports for the ongoing management of their chronic health condition. Some identified that they had already experienced difficulties finding these types of necessary and lifesaving supports.

3.2.1.1.2. Subtheme 1.2 “We are paying a lot out of pocket”: Navigator Assistance with Financial Support

A persistent theme across baseline interviews was uncertainty regarding potential financial hardships related to accessing medical equipment to manage medical conditions post-transfer. The need for assistance with applying for financial support related to their condition was a paramount concern for caregivers and youth.

3.2.1.2. Theme 2: "I’m actually really nervous about going to university": Navigator Assistance with Preparation and Transitioning to Post-Secondary Education

Participants expressed that they would like assistance with decisions about post-secondary including applications and preparation to attend. Within the context of health needs, participants anticipated requiring PN support with ensuring academic and medical accommodations on campus are put in place to meet their needs. Some participants expressed heightened stress related to the management of their health while attending post-secondary education. Concerns with financial challenges related to post-secondary came up for multiple participants. Some anticipated needing help with student loans and other financial assistance related to attending post-secondary (textbooks, living expenses). Both baseline themes describe sentiments related to an unknown future.

3.2.2. Post-intervention: participants report on how the patient navigator helped them transition

The analysis of the post-intervention interviews showed significant variation in the level of engagement between participants and PN. Participants had between 1 and 24 follow-up encounters with the PN, with an average of 9.6 follow-up encounters. Participants with fewer PN interactions expressed that they did not need more support due to prior preparation for transition or having few clinic visits, or that their contact with the PN was reduced due to pandemic restrictions or because they forgot the PN was available. One participant clearly identified needs that the PN could have helped with but did not due to low levels of interaction with the PN during the trial. Relationships between themes are illustrated in Fig. 1.

3.2.2.1. Theme 1: “they’re always there”: emotional support

Participants shared that the emotional support provided by the PN facilitated an overall positive transition experience. Emotional support was described as both the supportive presence of the PN and the application of specific engagement interventions. Participants explained that they felt supported when the PN checked in with them regarding their transition experience and progress on personal and transition-related goals. This was described as “being there” by multiple participants and as a “reassuring gesture” by others.

Emotional support from the PN was described as distinct from support received from other healthcare providers, family and friends, and invaluable even when participants had these other support systems in place. Participants described the PN as understanding of their experiences as an AYA with a chronic health condition.

Participants described that an emotionally supportive PN created space for them to share their feelings and experiences, including during times of crisis. These discussions sometimes led to receiving both emotional support and timely, relevant informational resources.

3.2.2.2. Theme 2: “she would look into it and get back to me”: informational and task-focused support

Participants reported the PNs supporting the transition to adult care by providing timely and relevant information. PNs sometimes provided task-focused support by completing necessary tasks on behalf of the participant to promote a positive transition experience for the young person.

3.2.2.2.1. Subtheme 2.1: healthcare and community resources and support

Participants shared that PNs followed up on topics discussed in their baseline assessment, thus providing them with individualized support. In addition, most participants received resources tailored to issues as they arose and when participants were unsure where to start. Conversely, one participant identified that the PN did not have extensive knowledge of resources in their town compared to the larger urban center.

Participants described the benefit of the PN role being located within the healthcare system, as this allowed PNs to access medical records and provide informational support related to their healthcare transition such as confirming referrals, appointments, and contact information of healthcare providers. Participants described receiving resources to help address specific healthcare issues, such as challenges accessing or paying for medications, and also related to community supports, including government funding programs and post-secondary supports for students with chronic health conditions.

Participants described PNs providing task-focused support within the healthcare system, such as contacting clinics on their behalf and writing letters of support, and in the community. These tasks done by the PN sometimes expedited processes or were crucial in helping participants access funding or programs. In particular, caregivers of young adults with chronic conditions described the PN’s support in helping them access financial and community supports as important during a time of immense overwhelm that found them “fumbling” and “floundering”.

3.2.2.2.2. Subtheme 2.2: self-management resources and tools

Multiple participants described being made aware of resources and tools that could help with tracking appointments, health information, and medications. Finally, many shared that it was helpful to know that they could contact the PN if they needed any information or had any questions about managing their healthcare needs. This informational and task-focused support could be built on, with the PN providing guidance to help participants learn to complete these healthcare related tasks themselves.

3.2.2.3. Theme 3: “i used every method she taught me. it worked”: navigator guidance to become more independent

The theme of PN guidance overlaps with and builds on previous themes. Participants described this as a process of teaching, goal setting, creating “action plans”, and/or talking through challenges participants experienced. It was particularly helpful when the PN did this in a way that was tailored to their individual needs, for example, PNs taking notes during meetings, sending follow-up emails, and identifying “homework” tasks to help participants follow through on needed actions. Several participants shared that the PN was aware that these tasks were new to them and understood the developmental considerations unique to AYAs.

3.3. Comparing baseline and post-intervention interviews

Similarities and differences between baseline and post-intervention themes are illustrated in Fig. 3. At baseline many participants identified a desire for assistance with tasks related to their transition to adult healthcare such as obtaining adult doctors and physically navigating new healthcare facilities, as well as information about financial assistance programs. In the post-intervention interviews, many participants noted that the PN actively assisted with information and task-focused support in the domains of healthcare and community support, thus directly addressing these baseline concerns. Post-secondary assistance was commonly identified in the baseline interviews and some participants in the post-intervention interviews shared that they received assistance with accessing scholarships/grants and accommodation services. Concepts unique at post-intervention included the need for adopting concrete self-management tools/resources, the need for guidance on a range of topics and with setting goals, and the need for emotional support. Participants provided briefer, less nuanced responses about their expectations from the PN at baseline in contrast to the wide breadth and depth of responses after their participation in the trial.

Fig. 3.

: Comparison of Baseline and Post-Intervention Themes.

4. Discussion

This research describes the needs AYA have when approaching their transition and how a PN service helped AYA meet these needs. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the perspectives of AYA and caregivers about the role of a PN before and after the transition to adult care.

This study’s findings align with existing literature in describing many challenges related to healthcare transition: mixed emotions 20 and/or negative emotions 21, relinquishing attachment to their pediatric team 22, apprehension about accessing new providers 2, concerns about new provider knowledge of their condition or individual needs 23, 24, concerns regarding transportation and parking at adult healthcare facilities 25 and concerns about finances and insurance as they enter adult services 25, 26. AYA in this study articulated uncertainty about transition which may be alleviated by better understanding the systematic differences between pediatric and adult care. Other transition studies similarly highlight the importance of disseminating information about the differences between pediatric and adult care to prepare youth for their transition 2.

4.1. Support with post-secondary education

While prevalent in our findings, the topic of post-secondary education in transition-related studies is sparse. However, the Canadian Pediatric Society recommends seeking to understand educational and vocational goals of AYA in order to support a successful transition 1. Studies focusing on the AYA perspective have found that information about this topic is sought by AYA 27. AYAs may face barriers entering post-secondary education if the professionals they are engaged with lack knowledge about grants and programs they may need to succeed academically 28. Youth with special healthcare needs and their parents can struggle to find educational services that fit their needs 29, 30. Despite the lack of consistent focus on educational/vocational planning in the healthcare transition literature, the healthcare setting has been identified as an appropriate context to share information about post-secondary education, as AYAs who seek accommodations often require medical documentation 31.

4.2. The significance of emotional support and continuity of care

The literature highlights the need for emotional support for transitioning patients 5 which can be validating and valuable for AYA; our findings are in agreement. For instance, receiving emotional support such as reassurance and encouragement from a PN was helpful for stroke survivors 32, and validation was desired by patients with asthma who worked with a PN 33. Indeed, PNs report that emotional support is an important component of their work in a variety of patient populations 34, 35.

A PN may be especially well positioned to create this environment during transition because they can tailor interactions to meet the emotional needs of AYA. They may be one of the few healthcare providers who consistently provides care to patients during the transition period, thus creating or enhancing continuity of care. Improving continuity of care is a frequent recommendation from studies exploring the AYA perspective 5.

4.3. Individualized informational and task-focused support

The importance of informational and task-focused support resonates with findings from other studies in various patient populations 32, 33. The PN as a social worker embedded in the healthcare system facilitated informational and task-focused support related to the healthcare system. Our study found that the ability of the PN to adapt and tailor their approach to the individual needs of a participant was impactful. This has been recommended in the literature 14, 36, 37, 38. Participants in our study and others reported that information geared toward a young audience was helpful 27.

4.4. Guidance and coaching strategies

Meaningful guidance that comes from a PN was a notable finding in the post-intervention interviews. This builds on existing literature indicating that AYA and/or caregivers who receive coaching support are more likely to enhance their skills such as stress management, self-efficacy and problem-solving 39. Participants in our study reported use of action plans with PNs as beneficial, which aligns with recommendations of a healthcare professional creating specific plans with AYA and completing regular check-ins 39. Setting goals was also identified as valuable for AYA who used an educational kit and online mentor to assist with their transition 27.

4.5. Practice implications

Implementation of a PN may help address challenges experienced by AYA during transition and mitigate gaps in care. Further practice implications address operationalization of the PN role. Participants may not have a complete grasp of the PN’s role before working with them, thus, this should be clearly articulated. Participants demonstrated their ability to articulate when they no longer needed the PN, suggesting a consensus on the end of the intervention in practice. There is potential benefit for patients when PNs possess knowledge about financial supports and post-secondary education, and developmental considerations of AYA, and are able to work collaboratively with parents/caregivers. This scope of work aligns well with the training and expertise of clinical social workers, however implications extend to other pediatric providers such as nurse practitioners. We suggest that further research address how other professional disciplines can execute the role of a PN; this may increase the availability of PN roles.

4.6. Limitations

Participants who completed both baseline and post-intervention interviews may have had more involvement and positive involvement with the PN. While the PNs ability to tailor the intervention to an individual and/or their involved family members was a strength, the study lacked a more thorough investigation of the potential impact of developmental disability on the experience of the intervention. Participant characteristics, such as mental health comorbidity or the number of clinics involved in their care, may have changed over the course of the study period, however were only collected at baseline. Reporting these characteristics at baseline could have more accurately described the sample. The small sample size is a further limitation. The COVID-19 pandemic may have influenced participants’ transition experiences and the research team’s ability to connect with participants for a post-intervention interview. The PN service itself has limitations related to accessibility such as language spoken, past experiences with healthcare and social services, and the scope of the PN role. Finally, the study took place within a healthcare system that is publicly funded; it is unknown whether the PN would be effective in different contexts.

5. Conclusion

Our findings support the implementation of a PN intervention to address a range of barriers associated with the transition to adult care. The AYA perspectives on working with the PN during transition may inform the future implementation of PNs in transition care.

Research ethics board approval

Institutional ethics approval was granted for this study. Participants provided written or oral informed consent or assent (with parent/guardian consent), documented in writing by study staff. Consent was sought from a parent/guardian unless the mature minor participant declined to have their parent/guardian involved.

Funding statement

Alberta Health Services (Research Number 1040209), Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation (Research Number 1042146), Stollery Children’s Hospital Foundation, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (388256- CHI- CBBA-161557, PJT-153337). These funders had no role in the design or conduct of the study, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and families who participated in the trial and in the interviews. We thank the members of the Children and Youth Advisory Council (CAYAC) and of the Youth Advisory Council (YAC) whose work contributed to the development of this intervention and trial, and to improvements during the trial. We thank the healthcare providers at Alberta Children’s Hospital, The Stollery Children’s Hospital and The Glenrose Rehabilitation Hospital who assisted with the study, the patient navigators and study staff who worked with the study, and all members of trial committees.

Operational Oversight Committee and Trial Management Committee: Catherine Morrison (Alberta Health Services), Jorge Pinzon (Department of Pediatrics, University of Calgary), Catherine Hill (Alberta Health Services), Karen Johnston (Alberta Health Services), Susan Hughes (Alberta Health Services), Katie Byford Richardson (Alberta Health Services), Jane Bankes (Alberta Health Services), Jake Jennings (Alberta Health Services), Chelsey Grimbly (Department of Pediatrics, University of Alberta), April Elliott (Department of Pediatrics, University of Calgary), Catherine Morrison (Alberta Health Services), Catherine Hill (Alberta Health Services), Karen Johnston (Alberta Health Services), Renee Farrell (Department of Pediatrics, University of Calgary), Iwona Wrobel (Department of Pediatrics, University of Calgary), Kyleigh Schraeder (CIHR), Elizabeth Morgan- Maver (University of Calgary), Gurkeet Lalli (University of Calgary). Data Safety Monitoring Board: Dr. Mario Cappelli (Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute, University of Ottawa), Dr. Anne Stephenson (Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto), Dr. Mina Matsuda- Abedini (Department of Pediatrics, University of British Columbia). Scientific Advisory Board: Dr. Graham Reid (Children’s Health Research Institute, University of Western Ontario), Dr. Bethany Foster (Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre, McGill University), Dr. Astrid Guttmann (Senior Scientific Officer, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, University of Toronto)

Clinical trials registry

The trial was prospectively registered at clinicaltrials.gov NCT03342495

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. We are submitting this manuscript using the appropriate reporting standards for the work.

Author contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, or the acquisition or analysis of data. All authors made significant contributions to either initial draft or critical revisions of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version.

References

- 1.Toulany A., Gorter J.W., Harrison M. A call for action: Recommendations to improve transition to adult care for youth with complex health care needs. Paediatr Child Health. Sep 2022;27(5):297–309. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxac047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gray W.N., Schaefer M.R., Resmini-Rawlinson A., Wagoner S.T. Barriers to Transition From Pediatric to Adult Care: A Systematic Review. J Pedia Psychol. Jun 1 2018;43(5):488–502. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsx142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duell N., Steinberg L., Icenogle G., et al. Age Patterns in Risk Taking Across the World. J Youth Adolesc. May 2018;47(5):1052–1072. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0752-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnett J.J. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Comparative Study. Am Psychol. May 2000;55(5):469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cassidy M., Doucet S., Luke A., Goudreau A., MacNeill L. Improving the transition from paediatric to adult healthcare: a scoping review on the recommendations of young adults with lived experience. BMJ Open. Dec 26 2022;12(12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman H.P., Muth B.J., Kerner J.F. Expanding access to cancer screening and clinical follow-up among the medically underserved. Cancer Pract. Jan-Feb 1995;3(1):19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Walleghem N., Macdonald C.A., Dean H.J. Evaluation of a systems navigator model for transition from pediatric to adult care for young adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes care. 2008;31(8):1529–1530. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allemang B., Allan K., Johnson C., et al. Impact of a transition program with navigator on loss to follow-up, medication adherence, and appointment attendance in hemoglobinopathies. Pedia Blood Cancer. Aug 2019;66(8) doi: 10.1002/pbc.27781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luke A., Doucet S., Azar R. Paediatric patient navigation models of care in Canada: an environmental scan. Paediatr Child Health. May 2018;23(3):e46–e55. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxx176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang K.L., Kelly J., Sharma N., Ghali W.A. Patient navigation programs in Alberta, Canada: an environmental scan. CMAJ Open. Jul-Sep 2021;9(3):E841–E847. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20210004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roland K.B., Milliken E.L., Rohan E.A., et al. Use of Community Health Workers and Patient Navigators to Improve Cancer Outcomes Among Patients Served by Federally Qualified Health Centers: A Systematic Literature Review. Health Equity. 2017;1(1):61–76. doi: 10.1089/heq.2017.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Annunziato R.A., Baisley M.C., Arrato N., et al. Strangers headed to a strange land a pilot study of using a transition coordinator to improve transfer from pediatric to adult services. J Pediatr. 2013;163(6):1628–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samuel S., Dimitropoulos G., Schraeder K., et al. Pragmatic trial evaluating the effectiveness of a patient navigator to decrease emergency room utilisation in transition age youth with chronic conditions: the Transition Navigator Trial protocol. BMJ Open. Dec 10 2019;9(12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dimitropoulos G., Morgan-Maver E., Allemang B., et al. Health care stakeholder perspectives regarding the role of a patient navigator during transition to adult care. BMC Health Serv Res. Jun 17 2019;19(1):390. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4227-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Creswell J. Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. third Edition ed. SAGE; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clarke V., Braun V. a practical guide. SAGE Publications; 2022. Thematic analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braun V., Clarke V. Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. Int J transgender Health. 2023;24(1):1–6. doi: 10.1080/26895269.2022.2129597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malterud K., Siersma V.D., Guassora A.D. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. Nov 2016;26(13):1753–1760. doi: 10.1177/1049732315617444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Hosson M., Goossens P.J.J., De Backer J., De Wolf D., Van Hecke A. Needs and experiences of adolescents with congenital heart disease and parents in the transitional process: a qualitative study. J Pedia Nurs. Nov-Dec 2021;61:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2021.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varty M., Speller-Brown B., Phillips L., Kelly K.P. Youths' experiences of transition from pediatric to adult care: an updated qualitative metasynthesis. J Pedia Nurs. Nov-Dec 2020;55:201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2020.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McManus M., White P. Transition to adult health care services for young adults with chronic medical illness and psychiatric comorbidity. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. Apr 2017;26(2):367–380. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2016.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heery E., Sheehan A.M., While A.E., Coyne I. Experiences and outcomes of transition from pediatric to adult health care services for young people with congenital heart disease: a systematic review. Congenit Heart Dis. Sep-Oct 2015;10(5):413–427. doi: 10.1111/chd.12251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bindels-de Heus K.G., van Staa A., van Vliet I., Ewals F.V., Hilberink S.R. Transferring young people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities from pediatric to adult medical care: parents' experiences and recommendations. Intellect Dev Disabil. Jun 2013;51(3):176–189. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-51.3.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McPherson M., Thaniel L., Minniti C.P. Transition of patients with sickle cell disease from pediatric to adult care: assessing patient readiness. Pedia Blood Cancer. 2009;52(7):838–841. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gray W.N., Resmini A.R., Baker K.D., et al. Concerns, barriers, and recommendations to improve transition from pediatric to adult ibd care: perspectives of patients, parents, and health professionals. Inflamm Bowel Dis. Jul 2015;21(7):1641–1651. doi: 10.1097/mib.0000000000000419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorter J.W., Stewart D., Cohen E., et al. Are two youth-focused interventions sufficient to empower youth with chronic health conditions in their transition to adult healthcare: a mixed-methods longitudinal prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cook K., Siden H., Jack S., Thabane L., Browne G. Up against the system: a case study of young adult perspectives transitioning from pediatric palliative care. Nurs Res Pr. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/286751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bagatell N., Chan D., Rauch K.K., Thorpe D. "Thrust into adulthood": Transition experiences of young adults with cerebral palsy. Disabil Health J. Jan 2017;10(1):80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rehm R.S., Fuentes-Afflick E., Fisher L.T., Chesla C.A. Parent and youth priorities during the transition to adulthood for youth with special health care needs and developmental disability. ANS. Adv Nurs Sci. Jul-Sep 2012;35(3):E57–E72. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e3182626180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allemang B.A., Bradley J., Leone R., Henze M. Transitions to postsecondary education in young adults with hemoglobinopathies: perceptions of patients and staff. Pedia Qual Saf. 2020;5(5) doi: 10.1097/pq9.0000000000000349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Egan M., Anderson S., McTaggart J. Community navigation for stroke survivors and their care partners: description and evaluation. Top Stroke Rehabil. May-Jun 2010;17(3):183–190. doi: 10.1310/tsr1703-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Black H.L., Priolo C., Akinyemi D., et al. Clearing clinical barriers: Enhancing social support using a patient navigator for asthma care. J Asthma. 2010;47(8):913–919. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2010.506681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wells K.J., Valverde P., Ustjanauskas A.E., Calhoun E.A., Risendal B.C. What are patient navigators doing, for whom, and where? A national survey evaluating the types of services provided by patient navigators. Patient Educ Couns. Feb 2018;101(2):285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yaseen W., Steckle V., Sgro M., Barozzino T., Suleman S. Exploring stakeholder service navigation needs for children with developmental and mental health diagnoses. J Dev Behav Pedia. Sep 1 2021;42(7):553–560. doi: 10.1097/dbp.0000000000000924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Staa A.L., Jedeloo S., van Meeteren J., Latour J.M. Crossing the transition chasm: Experiences and recommendations for improving transitional care of young adults, parents and providers. Child: Care, Health Dev. 2011;37(6):821–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01261.x. (doi) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sevick M.A., Trauth J.M., Ling B.S., et al. Patients with Complex Chronic Diseases: perspectives on supporting self-management. J Gen Intern Med. Dec 2007;22(Suppl 3):438–444. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0316-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaw K.L., Southwood T.R., McDonagh J.E. User perspectives of transitional care for adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatol (Oxf) 2004;43(6):770–778. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaks Y., Bensen R., Steidtmann D., et al. Better health, less spending: Redesigning the transition from pediatric to adult healthcare for youth with chronic illness. Healthc (Amst, Neth) Mar 2016;4(1):57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]