Abstract

Background

Traumatic injuries, particularly those involving massive bleeding, remain a leading cause of preventable deaths in prehospital settings. The availability of appropriate emergency equipment is crucial for effectively managing these injuries, but the variability in equipment across different response units can impact the quality of trauma care. This prospective survey study evaluated the availability of prehospital equipment for managing bleeding trauma patients in Austria.

Methods

A nationwide survey was conducted across 139 Austrian Prehospital Physician Response Units (PRUs) to evaluate the presence and adherence to guidelines of bleeding control equipment. The digitally distributed survey included questions on equipment types, such as pelvic binders, tourniquets, haemostatic gauze, and advanced intervention sets. Data were analysed against the most recent recommendations and guidelines to assess conformity and identify gaps.

Results

The survey achieved a 96% response rate, revealing that essential equipment like pelvic binders and tranexamic acid was available in all units, with tourniquets present in 99% of them. However, few services carried advanced equipment for procedures like REBOA or thoracotomy. While satisfaction with the current equipment was high, with 80% of respondents affirming adequacy, the disparities in the availability of specific advanced tools highlight potential areas for improvement, offering a promising opportunity to enhance trauma care capabilities.

Conclusions

While essential emergency equipment for haemorrhage control is uniformly available across Austrian PRUs, the variation in advanced tools underscores the need for standardised equipment protocols. The urgency for regular kit updates following prehospital guidelines and training is essential to enhance trauma care capabilities and ensure that all emergency response units are equipped to manage severe injuries effectively. This standardisation could lead to improved patient outcomes nationwide.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12873-024-01150-3.

Keywords: Emergency medical services, Equipment and supplies, Wounds and injuries, Austria

Background

Traumatic injuries continue to be a common cause of death, with bleeding being the primary cause of preventable fatalities post-trauma [1]. In case of massive bleeding, time is the most critical factor in saving a patient from exsanguination, necessitating early interventions in the prehospital phase [2, 3]. While simple measures like applying pressure, packing wounds and using tourniquets can often control extremity bleeding effectively, dealing with non-compressible torso haemorrhage (NCTH) presents a complex challenge. Due to the difficulty in controlling internal bleeding without invasive methods, procedures like resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) or even a resuscitative thoracotomy have to be considered [4–7]. The primary requirement for the success of these interventions relies on having the right equipment available within the physician response unit (PRU) system and the expertise that prehospital care physicians could offer.

In Austria, the PRUs are run by multiple contractors within each state, leading to a need for more standardisation regarding the emergency equipment deployed for haemorrhage control [8]. Furthermore, the equipment is tailored differently for PRUs and helicopters. Whether the existing equipment is selected based on current clinical guidelines or if internal processes dictate the choices remains to be seen. This lack of uniformity may lead to disparities in the availability of tools for controlling bleeding, potentially affecting the efficiency of trauma care and ultimately impacting patient outcomes.

On the one hand, the prehospital system in Austria is characterised by its helicopter emergency medicine services (HEMS), which are available at a high density. This is a strategic response to the country's geographical challenges, allowing for shortcutting time and potential disadvantages for patients who otherwise might not survive the journey to a hospital. On the other hand, the system relies on a ground-based emergency physician system, where, for specific indications, an emergency physician is dispatched with an ambulance. The equipment available for the management of life-threatening traumatic haemorrhages then depends on the particular unit [8].

The most relevant guidelines for treating prehospital trauma patients in Austria are the European guideline on the management of major bleeding and coagulopathy following trauma and the S3 guideline on the management of major trauma from the German Association of Orthopaedics and Trauma Surgery (DGU) [4, 9]. Both guidelines deal with prehospital and in-hospital procedures that can be used to decide which material should be carried in the kit with varying levels of evidence.

The study aims to assess the presence of bleeding control equipment in Austrian PRUs, including HEMS and ground-based units, via a nationwide survey and compare the results with recommendations from up-to-date guidelines and recommendations. By examining the availability of tools for managing haemorrhages, this research could shape policies and practice standards to guarantee that PRUs have access to essential resources for handling severe bleeding.

Methods

Study design and data collection

A survey was utilised to investigate whether the PRUs across Austria are equipped with materials recommended by current literature for managing critical traumatic haemorrhages. An online questionnaire was developed using Google Forms and distributed to all Austrian PRUs operating year-round [10–12]. The survey was disseminated via email in June 2022 to various organisations responsible for operating PRUs, including the Austrian Red Cross, the OEAMTC Air Rescue, the Arbeiter Samariter Bund Austria, the Emergency Medical Service of Vienna, Martin Air Rescue, and the ARA Air Rescue. Follow-up reminders were sent to organisations that had not responded within one month, and in some cases, a second reminder was necessary. The data collection phase concluded in May 2023 after multiple follow-ups. Special permission was required from the Red Cross branches in Carinthia and Styria.

The Medical University of Graz's ethics committee (IRB00002556), decision number 1111/2024, reviewed and approved this study. The ethics committee waived the need for consent to participate.

Austrian emergency medical services (EMS)

Austria’s EMS operates on the Franco-German model, integrating physicians into prehospital care. Emergency physicians are qualified medical practitioners specialising primarily in anaesthesia and related fields, such as intensive care medicine. These physicians conduct operations utilising PRUs (rapid response vehicles or helicopters) with an advanced paramedic. This configuration enables transporting supplementary equipment and specialised expertise directly to the patient. Conversely, standard ambulances typically possess only essential medical equipment [13].

Data indicate that emergency physicians are deployed in approximately 60–70% of prehospital missions in Austria, with discrepancies based on regional policies and the severity of cases. These physicians are intended to be predominantly summoned for high-acuity situations, such as major trauma or cardiac arrest. In contrast, paramedics manage more routine calls but can escalate care by consulting physicians when necessary [13, 14].

Survey structure

The questionnaire was divided into several sections, complemented by photographs to aid the evaluation process, as displayed in the Supplement (Figure S1). Respondents were asked to select or input their answers, with options for single and multiple selections and open-ended responses. The initial section of the survey inquired about the organisation, state, and type of PRU (rapid response vehicle or helicopter). Subsequent sections requested detailed information on the types of equipment carried for trauma haemorrhage control, including pelvic binders, manual haemorrhage control materials, the presence of tranexamic acid, types of crystalloid and colloid infusion solutions, and blood products available on the units. Finally, the respondent's satisfaction with the material was asked for, and an opportunity was given to leave comments in case of dissatisfaction.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics, including proportions, were used to summarise the data. The most relevant current guidelines were used to guide item importance to ensure a robust and contextually relevant interpretation of findings. Specifically, the analysis was guided by the "S3 Guideline on Polytrauma/Severe Injury Treatment" and the "European Guideline on Management of Major Bleeding and Coagulopathy following Trauma, 6th Edition" [4, 9].

Additionally, we categorised the results into three sections based on the urgency of the interventions since bleeding control depends on prompt action. We labelled them as "Immediately” for interventions that require instant execution, "Advanced" for those that are time-sensitive yet demand more personnel and expertise, and "Medications and Blood Products" for related treatments.

As there are no dedicated equipment recommendations specifically tailored to the prehospital environment, adherence to these guidelines was selected and ensured that the evaluation of emergency equipment for haemorrhage control was aligned with the latest best practices and scientific insights into trauma management. Furthermore, the insights derived from the survey responses were summarised in a recommendation table.

Finally, we performed a logistic regression analysis to identify factors influencing respondents’ satisfaction with the equipment. The dependent variable was binary, indicating whether respondents were satisfied or dissatisfied with the equipment. Variables were included based on theoretical relevance.

Objectives

The primary aim of this nationwide survey was to evaluate the equipment for bleeding control in Austrian PRUs.

As a secondary aim, the study aimed to explore the team’s satisfaction with the current equipment available.

Results

One hundred thirty-nine PRUs across Austria were contacted for the survey, with a response rate of 96%, correlating to 133 units. The survey revealed that all evaluated EMS units have basic materials for traumatic haemorrhage control, including pelvic binders and tranexamic acid (see Table 1). Specifically, a tourniquet was present in 99% of the units (132 out of 133), highlighting a widespread adoption of this emergency tool for haemorrhage control of extremities.

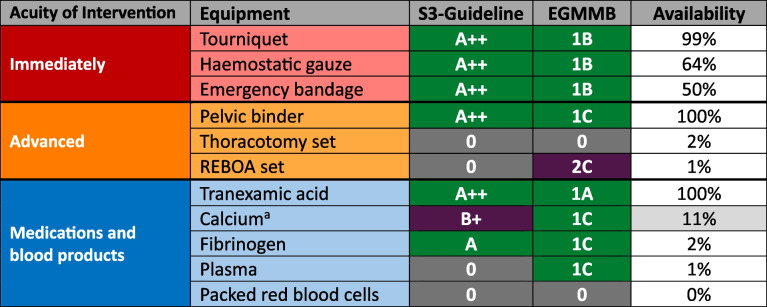

Table 1.

Available equipment on PRUs in Austria for managing traumatic bleeding compared to the most recent recommendations and grades of evidence relevant to the prehospital setting

Strong recommendation – essential equipment

Strong recommendation – essential equipment

Low recommendation – optional equipment

Low recommendation – optional equipment

No evidence for a recommendation

No evidence for a recommendation

a23 of 133 answers received (17%). 15 (11%) PRUs carry Calcium. 8 (6%) do not have it

Furthermore, more than half of the units reported having haemostatic gauze and Emergency bandages, such as Israeli bandages, as part of their equipment. However, specialised equipment for invasive procedures such as Clamshell Thoracotomy or REBOA (Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta) systems was less commonly available.

A minority of units carried calcium. Moreover, at the time of the survey, no blood products were available on Austrian PRUs.

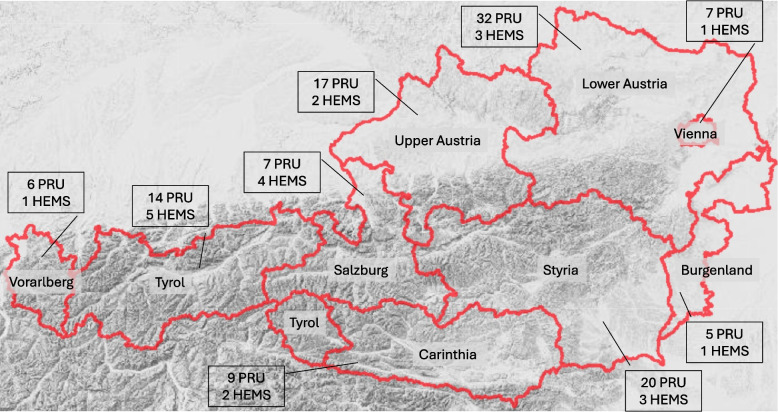

Table 2 summarises the current distribution of ground-based physician response units and HEMS services for each state of Austria, along with their respective sizes and populations. However, these absolute numbers may only partially explain the reasons for the concentration of prehospital physicians in certain areas, particularly those with mountainous terrain (see Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Background and demographic information at the timepoint of the survey conduction [15]

| State | Physician response vehicle | Helicopter emergency medical service | Size (km2) | Inhabitants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Austria | 32 | 3 | 19 179,84 | 1 718 373 |

| Styria | 20 | 3 | 16 399,51 | 1 265 198 |

| Upper Austria | 17 | 2 | 11 982,70 | 1 522 825 |

| Tyrol | 14 | 5 | 12 648,42 | 771 304 |

| Carinthia | 9 | 2 | 9 536,64 | 568 984 |

| Salzburg | 7 | 4 | 7 154,50 | 568 346 |

| Vienna | 7 | 1 | 414,84 | 1 982 097 |

| Vorarlberg | 6 | 1 | 2 601,68 | 406 395 |

| Burgenland | 5 | 1 | 3 965,22 | 301 250 |

Fig. 1.

Terrain map of Austria showing the PRU and HEMS distribution. The map was provided by geoland.at. States were marked in red. PRU… ground-based physician response unit, HEMS… Helicopter emergency medical service

As a secondary aim, the survey elicited opinions from the respondents regarding satisfaction with the current equipment for haemorrhage control. Of the 133 bases surveyed, 107 (80%) responded affirmatively, while the remaining 26 (20%) denied having adequate supplies. Among the 26 bases that responded negatively, 11 provided additional free-text feedback, specifying 18 distinct requests for materials. Analysis of this data revealed that the most frequently requested items were products for manual haemostasis (44%), followed by blood products (33%) (see Table 3). The logistic regression analysis showed that access to tranexamic acid and haemostatic gauze significantly predicted respondent satisfaction with the equipment (see Table 4).

Table 3.

Requested material of PRUs to improve the equipment for managing traumatic haemorrhage

| Requested material | Number of requested PRUs |

|---|---|

| Fibrinogen | 4 |

| Haemostatic Gauze | 4 |

| PRBC | 2 |

| REBOA-Set | 2 |

| Thoracotomy-Set | 2 |

| Albumin | 1 |

| Calcium | 1 |

| Gelatine-base colloids | 1 |

| Active warming sets | 1 |

PRU Physician response unit, PRBC Packed red blood cells, REBOA Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis with equipment satisfaction as the dependent variable and selected co-variables as potentially influencing factors

| Variable | OR | CI lower | CI upper | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemostatic gauze | 4.201 | 1.012 | 17.441 | 0.048* |

| Emergency bandage | 0.716 | 0.165 | 3.113 | 0.656 |

| Thoracotomy set | 2.017 | 0.107 | 38.097 | 0.640 |

| Blood products | 0.173 | 0.006 | 4.714 | 0.298 |

| TXA availability | 2.250 | 1.103 | 4.589 | 0.026* |

TXA Tranexamic Acid, OR Odds ratio, CI Confidence interval, *… statistically significant result

Discussion

The findings indicate that most recommended essential materials endorsed by current guidelines are on Austrian PRUs. The most commonly available items include pelvic binders, tranexamic acid, and tourniquet systems. There are notable deficiencies in the availability of calcium, fibrinogen, and wound dressings. Comparatively easy-to-use materials with high evidence are haemostatic gauze and bandages. These materials seem uncommon on Austrian PRUs, but the reasons for this still need to be clarified. PRUs operate mainly as independent units that respond to patients alongside ambulances. Therefore, they can often be the first to arrive on the scene. To address immediate bleeding control, essential basic equipment must be readily available so they are not dependent on the ambulance.

Nevertheless, the findings indicate that this is infrequently true. Advanced interventions such as REBOA or blood products are rarely available, assumably due to low recommendation levels. Additionally, thoracotomy sets appear absent, although specific components were not surveyed and might be present.

Blood products are primarily absent, potentially because more high-quality evidence about prehospital blood product use needs to be provided. Another reason could be the need for organisational efforts that might impede the introduction of blood products to a large number of existing physician units. Existing data on prehospital blood transfusions indicate benefits in mortality and blood product requirements in-hospital [7]. In the United States of America, a trend towards whole blood is prospering with prehospital systems that deliver such transfusions by paramedics [16, 17]. However, no PRU in Austria carries packed red blood cells; only 2% have plasma; 2 PRUs have LyoPlas, and one carries Fibrinogen concentrate.

Most respondents claimed to be satisfied with the available equipment, indicating no need to change the status quo. Whether this was based on rational arguments or other factors, like organisational fatigue, is unclear. Interestingly, the demand for prehospital blood was low despite increasing evidence of potential benefits, particularly in haemorrhaging trauma, aligning with international trends. Respondents reported higher satisfaction when haemostatic gauze and TXA were available, emphasising their subjective importance in effective haemorrhage management. Given that haemostatic gauze was not widely accessible despite strong evidence, this finding underscores the importance of equipping teams with essential haemostatic tools.

However, the lack of uniformity of the trauma equipment throughout Austria might lead to advantages or disadvantages of the trauma care provided depending on the area.

In the prehospital environment, the careful management of resources is critical, necessitating regular evaluation to ensure that only essential equipment is carried. The constraints of additional equipment include the financial expenditure and issues related to carriage, storage, and the limited space available in vehicles such as rapid-response cars and particularly helicopters. These factors necessitate a minimalist approach to equipment provision to optimise mobility and functionality within these confined settings. Furthermore, the size and training of the prehospital teams are pivotal considerations. Many advanced interventions are infrequently performed, such as high-acuity, low-occurrence (HALO) procedures [18] like REBOA, which makes it challenging to maintain proficiency among team members. This underscores the axiom that the efficacy of prehospital equipment is inherently tied to the skill level of its operators.

Consequently, continuous professional development and training are indispensable to ensure that teams can effectively utilise the equipment. Emergency physicians usually undergo specialised education, often encompassing simulation training for interventions such as REBOA, while Paramedics receive tiered training to ensure proficiency across a range of emergency scenarios [18]. Future research may investigate the effects of improved training and regional disparities in equipment allocation on patient outcomes.

Given the regular updates to guidelines and evidence, it is crucial for policymakers to continuously update equipment, especially for managing critical bleedings where timely medical intervention can significantly affect outcomes. Due to ongoing research, guidelines and literature constantly change, and equipment should follow these developments.

These changes must be accompanied by extensive teaching and relevant standard operating procedures to ensure the equipment comes with the necessary expertise from the clinicians.

Limitations

The varying practices of the responsible organisations complicated the evaluation. Austria has no nationwide uniformity in the equipment carried on PRUs. Each organisation or federal state independently determines what is done at their respective bases. Some organisations and states provided a consolidated evaluation of their standard equipment, significantly facilitating post-processing. It is crucial to note that this evaluation is only a snapshot, and the equipment may have changed. The adherence to guideline recommendations mainly applies to mainland Europe and might change in other regions with other guidelines.

Furthermore, most of the recommendations apply to the in-hospital setting and might need to be revised to the prehospital setting. However, due to a lack of data for this unique environment, this comparison was still the most objective reference available. Another aspect of this survey is that most responses came from non-medical personnel, potentially distorting the results. Unfortunately, due to the emergency services' organisational structure, it was not always possible to establish direct contact with the responsible emergency physicians.

Finally, this survey exclusively addressed equipment transported to the patient by PRUs. However, the equipment carried by ambulances was not included in the inquiry, which may encompass items that the PRU is not required to transport to prevent redundancy. Evaluating this aspect could represent an additional research question that would enhance the overall understanding of the topic. Nonetheless, as previously mentioned, immediate bleeding control is crucial when necessary, and PRUs may be the first responders before the ambulance arrives. Since most of the essential equipment needed for immediate use is relatively compact and affordable, it is considered vital for PRUs to carry this gear.

Conclusion

The study demonstrates the widespread availability of essential tools for managing traumatic haemorrhages across Austrian PRUs, like pelvic binders, tranexamic acid, and tourniquets, but also highlights the variability in equipment. The disparity in the availability of advanced intervention equipment suggests more standardised equipment policies to ensure uniform trauma care. This study underscores the necessity of continually updating prehospital guidelines and equipment to improve trauma care efficacy and outcomes.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Michael Eichinger and Michael Eichlseder contributed equally to this research project and are considered as equally first authors.

Abbreviations

- DGU

German association of orthopaedics and trauma surgery

- HEMS

Helicopter emergency medical service

- NCTH

Non-compressible torso haemorrhage

- PRBC

Packed red blood cells

- PRU

Physician response unit

- REBOA

Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta

Authors’ contributions

ME and ME1 contributed equally to the study idea, design, conduct, manuscript preparation, and review, which is why both authors are the first authors. GS, AP, PZ and NS contributed to the data acquisition, manuscript preparation and correction. PZ1 was responsible for the study design, manuscript correction and supervision.

Funding

There has been no funding for this study.

Data availability

The raw data from the questionnaire can be requested from the corresponding author (philipp.zoidl@medunigraz.at) on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The survey did not involve patient data and was entirely voluntary; No direct personal data was collected. The Medical University of Graz's ethics committee (IRB00002556), decision number 1111/2024, reviewed and approved this study. The ethics committee waived the need for consent to participate.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Carroll SL, Dye DW, Smedley WA, Stephens SW, Reiff DA, Kerby JD, et al. Early and prehospital trauma deaths: Who might benefit from advanced resuscitative care? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;88(6):776–82. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/jtrauma/fulltext/2020/06000/early_and_prehospital_trauma_deaths__who_might.10.aspx. [cited 2024 Apr 16]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harmsen AMK, Giannakopoulos GF, Moerbeek PR, Jansma EP, Bonjer HJ, Bloemers FW. The influence of prehospital time on trauma patients outcome: A systematic review. Injury. 2015;46(4):602–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gauss T, Ageron FX, Devaud ML, Debaty G, Travers S, Garrigue D, et al. Association of Prehospital Time to In-Hospital Trauma Mortality in a Physician-Staffed Emergency Medicine System. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(12):1117–24. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamasurgery/fullarticle/2751937. [cited 2024 Apr 23]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polytrauma/Schwerverletzten-Behandlung S3-Leitlinie der. Available from: https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/187-023.html. [cited 2024 Apr 16].

- 5.Wortmann M, Engelhart M, Elias K, Popp E, Zerwes S, Hyhlik-Dürr A. „Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta“ (REBOA). Chirurg. 2020;91(11):934–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudolph M, Lange T, Göring M, Schneider NRE, Popp E. Clamshell-Thorakotomie im Rettungsdienst und Schockraum: Indikationen. Anforderungen und Technik Der Notarzt. 2019;35(04):199–207. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wise D, Davies G, Coats T, Lockey D, Hyde J, Good A. Emergency thoracotomy: “how to do it.” Emerg Med J. 2005;22(1):22. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1726527/. [cited 2024 Apr 23]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weninger P, Hertz H, Mauritz W. International EMS: Austria. Resuscitation. 2005;65(3):249–54. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0300957205001565. [cited 2024 Apr 16]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossaint R, Afshari A, Bouillon B, Cerny V, Cimpoesu D, Curry N, et al. The European guideline on management of major bleeding and coagulopathy following trauma: sixth edition. Critical Care 2023;27(1):1–45. Available from: https://ccforum.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13054-023-04327-7. [cited 2024 Apr 16]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Burns KEA, Kho ME. How to assess a survey report: a guide for readers and peer reviewers. CMAJ. 2015;187(6):E198. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4387061/. [cited 2024 Jun 17]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Burns KEA, Duffett M, Kho ME, Meade MO, Adhikari NKJ, Sinuff T, et al. A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys of clinicians. CMAJ. 2008;179(3):245–52. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18663204/. [cited 2024 Jun 17]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirshner B, Guyatt G. A methodological framework for assessing health indices. J Chronic Dis. 1985;38(1):27–36. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3972947/. [cited 2024 Jun 17]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prause G, Orlob S, Auinger D, Eichinger M, Zoidl P, Rief M, et al. System and skill utilization in an Austrian emergency physician system: retrospective study. Anaesthesist. 2020;69(10):733–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prause G, Wildner G, Gemes G, Zoidl P, Zajic P, Kainz J, et al. Abgestufte präklinische Notfallversorgung – Modell Graz. Notfall und Rettungsmedizin. 2017;20(6):501–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Regionale Gliederungen - STATISTIK AUSTRIA - Die Informationsmanager. Available from: https://www.statistik.at/services/tools/services/regionales/regionale-gliederungen. [cited 2024 Apr 18].

- 16.Braverman MA, Smith A, Pokorny D, Axtman B, Shahan CP, Barry L, et al. Prehospital whole blood reduces early mortality in patients with hemorrhagic shock. Transfusion (Paris). 2021;61(S1):S15-21. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/trf.16528. [cited 2024 Apr 16]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braverman MA, Schauer SG, Ciaraglia A, Brigmon E, Smith AA, Barry L, et al. The impact of prehospital whole blood on hemorrhaging trauma patients: A multi-center retrospective study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023;95(2):191–6. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/jtrauma/fulltext/2023/08000/the_impact_of_prehospital_whole_blood_on.5.aspx. [cited 2024 Apr 16]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rief M, Eichlseder M, Eichinger M, Zoidl P, Zajic P. Overview and comparison of requirements and training for prehospital care physicians in Europe. Eur J Emerg Med. 2023;30(2):140–2. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/euro-emergencymed/fulltext/2023/04000/overview_and_comparison_of_requirements_and.15.aspx. [cited 2024 Nov 25]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data from the questionnaire can be requested from the corresponding author (philipp.zoidl@medunigraz.at) on reasonable request.