Abstract

The Genetic Counseling profession in South Africa (SA) was established 35 years ago when the first degree program was initiated at the University of the Witwatersrand in 1989. A second program was developed at the University of Cape Town in 2004. This article aims to describe the development of the profession in SA, with a focus on the last decade. The profession has been growing against the backdrop of a diverse population of 62 million with high rates of HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis and a poorly functioning health care system. SA was one of the first countries to regulate the profession when the Health Professions Council recognized genetic counselors (GCs) as health care professionals in 1992. Since 2017, the student body (now including some internationals) is becoming more representative of the local population and SA graduates are assisting in establishing counseling and training programs in Ghana and Oman. The professional group (GC-SA), formed in 2008, now represents the profession locally and internationally. Challenges remain, although training programs are established, and registration and billing in place. State employment opportunities are few and graduates have to become entrepreneurs, setting up private practice and seeking work in laboratories and research projects. With about a third (16) of qualified GCs (47) leaving the country and only 31 presently working locally, only about 10% of the genetic needs of the population can be met. Addressing these issues, as well as the lack of funding and political will, is a priority for the future.

Keywords: Genetic counseling, Genetic counselors, South Africa, Training

Introduction

Genetic counseling is a young and dynamic profession that is growing worldwide.1,2 It is inextricably intertwined with the rapidly advancing field of human genetics. Genetic counselors (GCs) are expected to keep up with these advances and apply the new knowledge appropriately in their counseling situations within their communities to the benefit of those seeking their expertise.

Although there are medical genetics services in several African countries, South Africa (SA) was the only one providing formal genetic counseling services and training programs for many years,3,4 until recently, when a training program was set up at the University of Ghana with the first intake in 2022.5 Some of the early history of genetic services and genetic counseling in SA has been reported,6,7 and the roles of local GCs have been investigated and described.4 The training of GCs has now been going on for 33 years, and in the last decade (since the last update in 2013),4 many new genetic advances, findings, and opportunities have enriched and supplemented this history and the roles. For these reasons, it is timely and necessary to update the progress that has occurred in the field locally. Therefore, in this article, the recent history and growth of the profession will be reviewed and discussed.

Background on SA

SA is a low-to-middle income developing country situated at the Southern tip of the African continent and populated by people of many different origins, ethnic groups, cultural backgrounds, and languages. The country covers 1,223,000 km2, which is larger than France, Germany, and England combined.8 In the population of 62 million people, 50.4 million are Black African, 5.05 million have mixed ancestry, 4.5 million are White European, 1.7 million are of Indian or Asian origin, and 250,000 of various other origins.9 There are 12 official languages, with sign language added in 2023. The most common home language spoken in the country is isiZulu (25%); although English is spoken by only 8% of the population, it is used for most official, business, and commercial communications.8 The population is young, 26.4% are under 15 years of age, and 22 million are aged 0 to 19 years. The majority live in urban areas (67.8%), and life expectancy is 60 years for males and 65 years for females.9

SA has a dual health care system with the majority of the population making use of government funded public health care and a minority using self-funded private health care.10 The country is still burdened with health care inequalities, high rates of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) and tuberculosis, poorly functioning health care systems, poor health outcomes, and high neonatal and maternal morbidity.11 Furthermore, there are major concerns about poverty, unemployment, housing, water and electricity supply, inadequate sanitation, and access to health care.12

Medical genetic services

Within this context genetic services have been developing and genetic counseling clinics are one of the key clinical elements of these services. The clinics were initiated in the early 1970s in an academic environment, by 2 immigrant British medical doctors with an interest in human genetics: Professor Trefor Jenkins, a hematologist in Johannesburg, and Professor Peter Beighton, a physician with an orthopedic focus, in Cape Town.13 Together with 2 medically trained cytogeneticists, a medical social worker (in Johannesburg), and a nurse (in Cape Town), clinics were set up at local public hospitals in these 2 major cities. The details of the early development of these genetic clinics have been covered in various publications.6,7,13, 14, 15

Today, genetic counseling clinics are available in tertiary state hospitals in major cities, Johannesburg, Cape Town, Durban, and Pretoria. They are well used, always busy, and demand for their services has grown over the last decade. However, people living in rural areas still need to travel into the nearest city if they require these specialized services. Given the vastness of the country, this travel can be very lengthy, taking hours and comes at a cost to the patients.

There are some unique features, within the genetic profile of SA populations, which need to be considered in local counseling situations. For example, oculocutaneous albinism (OCA), which occurs at a prevalence of 1 in 3900 births in the black population16 is more common here than elsewhere, and the associated problems differ from those found in other countries.17 Furthermore, founder variants have been identified in the black population for OCA, cystic fibrosis, Fanconi anemia, Gaucher disease, Bardet Biedl syndrome, and conditions. These variants are almost all different from the common variants observed in other populations, and nonsyndromic deafness is not caused by the common variants seen elsewhere.18, 19, 20, 21 Locus heterogeneity is present for Huntington disease and 2 common triplet repeat expansion loci (HTT and JPH3) have been identified in Africa. “These findings have important clinical consequences for diagnosis, treatment, and genetic counseling in affected families”18 [p.149] in SA. Furthermore, changes are currently occurring in this profile, and the migration of people from countries to the North of SA in the last 2 decades has led to the demand for counseling and treatment for genetic conditions, such as sickle cell anemia.22 Although common in Central Africa, these conditions were not previously found in SA black populations.23 SA GCs therefore have to be aware of expanding local knowledge, keep up with the results of local research, and apply the findings to their counseling practice appropriately.

Genetic counseling training programs

The need for GCs was recognized in 1988, and training was initiated at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) in Johannesburg in 1989 and later, in 2004, at the University of Cape Town (UCT), in Cape Town.3,4 In preparation for setting up the course, the local course developer visited the Directors of 2 training centers (Joan Marks at the Sarah Lawrence College in New York and Ann Walker at the University of California) in the United States in 1988 to observe and discuss their courses and curricula.

The MSc in genetic counseling at Wits began as an 18-month course and included genetic counseling theory, counseling skills training, clinical aspects of genetic conditions, mechanisms and inheritance patterns, cytogenetic and molecular testing principles and laboratory report interpretation, common metabolic conditions and enzymatic testing, and a research project. It was then revised in the early 90s to a 2-year degree with similar but updated content in line with new developments in the field and a 30% research component. From 2024, after a revision and in compliance with the university’s policies, the Wits course will change to a 1-year full-time program, followed by a 2-year post-graduate internship. The second master’s degree course, developed at the UCT in 2004, followed a syllabus similar to that of Wits. Both programs have a strong emphasis on counseling skills training, and the course content is continuously revised to incorporate new developments in the field. In 2013, UCT also offered 4 of the semester courses as occasional courses in an attempt to upskill other health care professionals in the principles of medical genetics and genetic counseling. Although training programs were well established and approved by the SA Qualifications Authority (https://www.saqa.org.za/), training had to be halted from 2011 to 2013 because of the lack of employment opportunities for graduates.

The genetic counseling courses had a strong emphasis on achieving good counseling skills. Furthermore, because the first course convenor/director was originally a social worker trained in Rogerian thinking and principles24 and later influenced by the works of Seymour Kessler25,26 and Jon Weil,27 these philosophies were emphasized and became basic to the course. Later, as more books on genetic counseling became available, these were and are frequently consulted, but at the beginning, the first editions of “The guide to genetic counseling” and “Facilitating the genetic counseling process”27, 28, 29, 30, 31 were used.

Both degrees are accompanied by a 24-month internship in compliance with legislation. At UCT the first 12 months overlap with the second year of the degree and at Wits, from 2024 onward, the full 24 months will be completed post degree. At Wits, students were usually only enrolled every 2 years, whereas at UCT there was yearly enrollment.

A research project must be completed, and a research report submitted and passed, before the degree is awarded. Traditionally, the research was written up as a dissertation. However, the option of presenting the work in the form of an article ready for submission for publication is becoming the preferred format, especially at Wits.

The second Wits course convenor/director, a qualified GC, was also originally a social worker, and she retained the psychosocial focus on good counseling skills and meeting the clients’ needs (as has been the focus in training courses in the United Kingdom and Australia, whereas in the United States and Canada a more didactic model of counseling tends to be used).2 Training in cross-cultural counseling is also emphasized in the course, and the cultural diversity of the many local ethnic groups is considered.3,32, 33, 34

The demand for the course always exceeded the available places with the number of applicants increasing from ∼10 in previous years to more than 60 presently. These individuals compete for between 2 and 6 positions. Most of the students are scientists with a BSc Honors degree in human genetics. Although it is an advantage for trainees to have this basic qualification, those with Honors degrees, in one of the other life sciences or psychology may apply. Applicants without any genetics background are expected to pass an entrance exam with 65% or more to be considered for a place on the course. Those who apply are also encouraged to gain some exposure to basic counseling techniques before applying for the course through community organizations, such as Lifeline (a nonprofit organization offering a telephone counseling service for people with mental and emotional problems). A basic counseling skills course is included in both training programs.

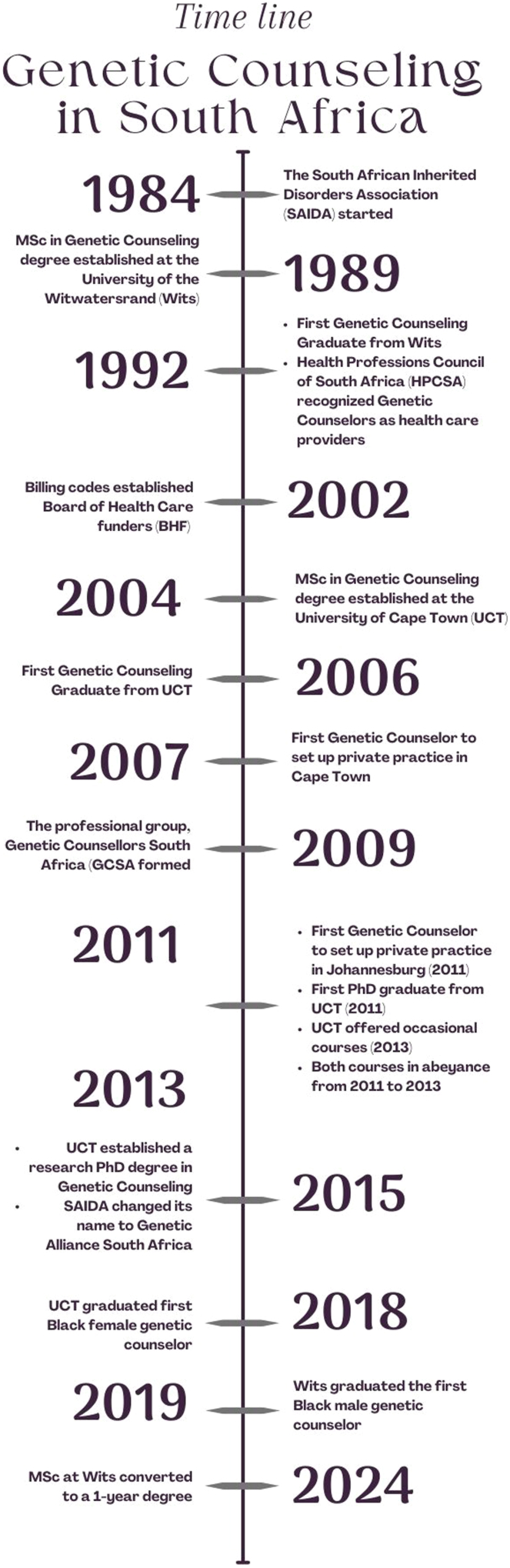

The first student graduated from Wits in 1992 and from UCT in 2006.4 Although the first Wits graduate was the first male GC, all the graduates thereafter were female until a second male completed the course in 2019. Since then, several more males have been enrolled. Similarly, previously most applicants were from the White population, but in 2018, the first (female) student with Black African ancestry completed the course (UCT), and in 2019 the first (male) with Black African ancestry graduated (Wits) and was registered. Including diversity among the students has been a goal of the training and both universities have strived toward this objective. Since 2019, diversity has steadily increased with graduates now representing all population groups and genders. Figure 1 shows the timeline of significant events in the development of the genetic counseling field in SA.

Figure 1.

Timeline.

Regulating the profession

Early in the development of the field, genetic counseling was recognized by the Health Professionals Council of SA (HPCSA) in 1992. The HPCSA is a regulatory body and all health care professions in SA are legislated to register with this governing body so that training and registration are completed in compliance with the Health Professions Act 56 of 1974.35 GCs fall under the medical and dental board in the category medical scientists. SA was one of the first countries to officially recognize and regulate the profession. The first group of 10 counselors registered were all experienced scientists (with MScs or PhDs), who had been working in the human genetics field for many years and doing some counseling for specific conditions, except for 1 (an experienced social scientist with a PhD degree), who had been counseling for many different genetic disorders for nearly 20 years. These individuals were registered in 1992 as GCs under a grandfather clause. There was a short transition period in which individuals who did not hold a MSc in genetic counseling could undergo an 18-month experiential training, which would result in registration after successful completion. Thereafter, counselors were required to have the recognized master’s degree, complete the 24-month internship training in a recognized facility, and submit (after attaining the degree) a Portfolio of Evidence (PoE) to enable them to register with the HPCSA. The PoE is a comprehensive document containing evidence of the student having attained the competencies required to perform independent practice. The PoE includes evidence of discipline specific knowledge, number of patients/clients counseled and range of diagnoses seen, community involvement, research competency, assessments, and evidence of reflective thinking. After the scope of practice was revised and approved in 2009, the HPCSA updated the regulations for training and registration again in 2019. Continuing education of GCs is required and controlled by the collection and regular annual submission of Continuing Professional Development points. Although UCT and Wits remain the only institutions in SA offering degrees and internship training in genetic counseling, the University of Stellenbosch has been accredited as a genetic counseling intern training facility post degree and has been training interns since 2012.

Having official recognition was not enough to allow for reimbursement for services when working in the private sector. It was around 2002 when discussions were held with the Board of Health Care funders of SA (https://bhfglobal.com) to put practice codes in place. Since then, GCs can apply for a practice number and bill for their services. Private clients can claim reimbursement from their medical health insurance providers for the costs of genetic counseling consultations. GCs in private practice typically charge between $55 and $60 per session. These fees are reviewed annually. In addition, GCs take out liability insurance and are recognized as a category of professionals with these insurers.

Community work

The SA Inherited Disorders Association (SAIDA) was set up by staff of the human genetics department in Johannesburg in 1984 to inform the lay and medical community about genetic disorders and develop genetic support groups. Eventually 24 groups (Down syndrome, neural tube defects, etc) were initiated, and they provided students with opportunities for voluntary community-based practical work. Also, SAIDA sponsored an international expert in the field of human genetics to visit SA annually. Many world leaders in the field visited, including Professor Peter Harper, from Cardiff University, United Kingdom, who had published his book entitled Practical Genetic Counseling in 1982 (later, 7 further editions were produced).36 These experts provided lectures and workshops to expand the knowledge and skills of the genetic counseling students. This book was used as a basic text for many years in the department in Johannesburg and in the training of GCs. In 2015, SAIDA was renamed the Genetic Alliance of SA, and in 2020 it was dissolved and became part of Rare Diseases SA (RDSA) (https://www.rarediseases.co.za/) for economic and practical reasons. The trainees from both universities are encouraged to identify and engage with a parent support group as volunteers. Such engagement enables them to gain insight into the psychosocial aspects of genetic disorders that individuals and their families experience. It further serves to raise awareness of the role of a GC in a support group, and a GC was formally employed by RDSA in 2022. Community work continues to be part of every counselor’s training, as reported in the survey on roles of GCs in SA,4 and evidence of involvement is documented in the student’s PoE. At that time, this part of their work involved marketing the service and public engagement, which included writing and circulating pamphlets, writing articles for the popular press, giving talks and radio and television programs. Contact with the media has expanded in the last few years, and presently use is made of websites and social media platforms to raise awareness of the availability and objectives of genetic counseling.

Research in the context of training

The profession’s beginnings were based initially in active research programs in the academic divisions of human genetics in Johannesburg and Cape Town when scientists involved in genetic research began to recognize the genetic counseling requirements of research participants. Little information was available on genetic disorders in the indigenous populations; therefore, this was the focus of the early research. This research often required interaction with the participants and their families, and as a result, the researchers (mostly scientists, initially, later registered as GCs, with the HPCSA under the grandfather clause) started providing the participants and their families more information on their condition and advised on reproductive risks, testing options, and management. Some of the research interests that drove this process were OCA,17 Huntington disease,37,38 spinocerebellar ataxia39 retinal degenerative diseases,40 and Lynch syndrome.41

The large research project on Lynch syndrome resulted in the first PhD being completed by a GC. Her research was focused on psychosocial factors and surveillance services.42, 43, 44 The second PhD graduate investigated the interactional dynamics in genetic counseling sessions.45, 46, 47 A number of other GCs have since obtained PhDs, although not all are in the field of genetic counseling. In 2015, a research PhD in genetic counseling degree was introduced at UCT to formally create a career pathway for GCs who want to pursue academics. Altogether, 8 GCs now have PhDs (3 have since retired), and 3 more are in the process of undertaking their doctoral research. Presently, these projects can be presented either as 4 articles for publication or as a thesis.

The professional group: GC-SA

The GC-SA was formally started in 2009 as a subgroup of the SA Society of Human Genetics (SASHG), to promote the principles of genetic counseling and support counselors.4 The association provides the profession with a voice and contact with other national and international genetic counseling organizations is maintained. It has grown exponentially and now has 74 members and adherents (https://sashg.org/). As the formal body representing the genetic counseling community of SA, the GC-SA works alongside the HPCSA to develop guidelines for the profession. The GC-SA developed and updated the scope of profession and in response to the covid pandemic developed tele counseling guidelines for use in genetic counseling sessions.

The GC-SA committee invites an international expert to visit the country biennially to give lectures and workshops and speak at the SASHG biennial congress. Eminent GCs have visited SA, presented challenging workshops, and given valuable input to the profession. As the number of GCs has grown, the GC-SA has become more engaged, and there is an active presence on social media and education sessions, are organized where GCs and trainees can present their research findings. The GC-SA community collaborates on several projects and advises the HPCSA on matters relevant to genetic counseling practice. The group is currently working together to develop a national curriculum for internship training in accordance with the HPCSA guidelines, as well as investigating employment opportunities in state hospitals.

International relations

To develop international relationships, networking, and communications in the field, the course convenor at Wits made contact in the early years with various training program directors in the United States and attended the national directors’ Asilomar meeting in 1989.48 Later, she visited the new training courses in the United Kingdom and Australia to share training and practice experiences and made and maintained contact with the directors in Manchester and Melbourne. Further contact with the international body of directors of genetic counseling courses was maintained when the Transnational Alliance of GCs was established in 2004.49,50 SA is currently represented on the board of directors, and a SA GC attends Transnational Alliance of GCs meetings. International relationships have contributed to staying abreast of new developments and ensured access to expertise not available in SA, as well as providing opportunities for international rotations

Both universities have accepted international students (from Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom) for clinical rotations. They benefitted greatly from the number and variety of genetic cases they observed in genetics clinics while in SA. Because of funding limitations, SA GCs have not been able to visit other international centers, although 1 student from UCT was able to fund herself. Some UCT trainees have visited other local human genetics departments in which training is not available, and such visits have sometimes led to employment opportunities. SA has further contributed to seeding international training programs. After retiring from Wits, the course director took up a 4-year contract (1999-2003) as director of the genetic counseling course at Griffith University in Brisbane, Australia, a UCT graduate started services in Oman, and UCT has trained Omani students. Oman is now in the process of developing their own master’s in genetic counseling course. Furthermore, staff from both SA universities worked with the University of Ghana to establish their master’s degree in genetic counseling (first student intake 2022), and a UCT graduate is currently the course director. This is the second country on the African continent with a program.

Employment

Initially qualified counselors could only work in part-time or temporary research posts. Then, 8 new permanent full-time jobs were created in 2000 by the Provincial Department of Health, National Health Laboratory Service, and these were based in the Division of Human Genetics in Johannesburg. Since then, no new posts have become available there. The first full-time post in Cape Town was a university post created in 2014. Later another was created at the University of Stellenbosch, and there are 2 more posts based in the Western Cape Department of Health, 1 at Tygerberg and 1 at Groote Schuur Hospitals. The salary scale ranges between $32,000 and $48,000 per annum for those in full-time positions.

Because of the limited number of posts in government health departments, GCs are seeking alternative employment. In 2007, the first GC started providing a service to private patients at UCT private hospital (F Loubser personal communication). Then in 2011, 2 counselors in Johannesburg set up a private practice and established a company, GC network (https://www.gcnet.co.za/), to provide genetic counseling services to individuals and their families, as well as consulting services to industry (N. Kinsley personal communication). In 2013, the first GC was employed by a laboratory performing genetic diagnostic testing, and a genetic counseling clinic was set up (S. Walters personal communication). RDSA then employed a GC in 2022. Since then, the majority of GCs are setting up private practice. In these practices, they often work closely with 1 or 2 specialists or medical practices from whom they receive appropriate referrals (many for cancer genetic counseling) and in whose practice they might have counseling rooms. Others find employment working with laboratories or research programs. Most are working in Johannesburg and Cape Town, whereas a few are working in various capacities in other cities (eg, Durban, Pietermaritzburg, Stellenbosch, and Bloemfontein). Because of the lack of positions, GCs have had to find employment elsewhere. SA GCs have found employment in the United Kingdom, Australia, and United States (1 passed the US National Society of Genetic Counselors Board exam in the early years at the first attempt), and 2 are working in the newly developed genetic services in Oman and Ghana. Table 1 shows the current number of qualified GCs and where they are employed. However, those in full-time employment in SA are dedicated to their jobs, progressing well, and will make up the experienced staff needed for the future of the profession and the training of GCs for the country.

Table 1.

Number of genetic counselors trained in South Africa and places of employment

| Place | State | Private | Research | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory | Private practice | ||||

| South Africa | 31 | ||||

| Western Cape | 4 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 13 |

| Gauteng | 5 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 15 |

| KwaZulu-Natal | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Freestate | 1 | 1 | |||

| Not practicing in SA | 16 | ||||

| Total | 47 | ||||

SA, South Africa.

The future

It has been 31 years since the first GC graduated, and much has happened during this time. The profession has grown within the limited resources of the country and become formally recognized. Research outcomes have resulted in the profession becoming more appropriate and relevant to local communities. The research project on the roles of GCs in SA threw light on the functions and activities of counselors a decade ago.4 As recommended in that article, a follow-up project on the roles of GCs in the present environment is being undertaken. On observation, counselors now counsel far more than the previously reported 57 different disorders, cancer counseling has increased exponentially, as has happened in Australia,51 there is more direct interaction with laboratories, and counselors are becoming more knowledgeable and more involved with variant curation. Counselors still have an active teaching role, providing lectures to medical, science, and paramedical students and the lay public, more are involved in research programs, and more are proceeding to do a PhD. Further they have marketing roles, produce and distribute information on the service, have administrative roles, and contribute in many constructive and significant ways to the departments and hospitals in which they work.

Unfortunately, employment continues to be a challenge for all graduates. The employment situation has not improved much since 2013.3,4 Major obstacles in job creation are political will and funding. Although guidelines for the management of genetic disorders were developed in 2001 and updated in 2022,52 the recommendations have not been implemented. A lack of resources and allocation of funds remains a major challenge in implementing equitable health care services in general. Despite these challenges, the profession has continued to grow. GCs have become entrepreneurs in creating job opportunities. Many have set up private practice, which is expanding to other provinces. Private practice has successfully raised awareness of the need of GCs as shown by the recent unpublished research of one of the genetic trainees, which found that once clinicians became aware of the positive impact of having a GC in their multi-disciplinary team, they found the service invaluable and cannot imagine their practices without one (W. Pretorius, personal communication). Furthermore, local interprovincial rotations have resulted in 2 positions being created for GCs in 2 provinces that did not have the services of a counselor. The challenge is, however, that these are still nonpermanent positions, and efforts to create permanent state positions are continuing. Strategies to address the challenges are constantly being revised and implemented by the counselors in the state service and the medical geneticists that support them. Setting up satellite clinical rotation sites and investigating the feasibility of undertaking 12 months of community service (mandatory for other health care professionals) after the internship are 2 examples of creating awareness for the services of a GC. Another strategy being considered is for a GC to continue to a PhD and design a collaborative research project that could lead to the creation of a post.

Conclusion

There is an international recommendation from the Royal College of Physicians that 1 medical geneticist supported by 4 GCs is required per million of the population.53 Because SA has a population of ∼62 million people,9 the country needs ∼250 GCs to offer a comprehensive genetic counseling service to all those who need it. This is the challenge facing the present staff of the country’s departments of human genetics and the new graduates being trained, in the future.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all who provided information to assist with the accuracy of the information. The authors want to particularly acknowledge the significant role the second course convenor played in developing the profession.

Funding

No funding was required.

Author Information

Conceptualization: T.M.W., J.G.R.K.; Resources T.-M.W., J.G.R.K., K.F., J.L.G.; Writing-original draft: T.M.W., J.G.R.K.; Writing-review and editing: T.M.W., J.G.R.K., K.F., J.L.G.

ORCIDs

Tina-Marié Wessels: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2676-0564

Jacquie L. Greenberg: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9202-0903

Katryn Fourie: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4393-3436

Jennifer G.R. Kromberg: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0539-5681

Ethics Declaration

Not available because research was not conducted on human subjects.

Footnotes

This article was invited and the Article Publishing Charge (APC) was waived.

References

- 1.Abacan M., Alsubaie L., Barlow-Stewart K., et al. The global state of the genetic counseling profession. Eur J Hum Genet. 2019;27(2):183–197. doi: 10.1038/s41431-018-0252-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ormond K.E., Laurino M.Y., Barlow-Stewart K., et al. Genetic counseling globally: where are we now? Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2018;178(1):98–107. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenberg J., Kromberg J., Loggenberg K., Wessels T.M. In: Genomics and Health in the Developing World. Oxford Mongraphs of Medical Genetics. Kumar D., editor. Oxford University Press; 2012. Genetic counseling in South Africa; pp. 531–546. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kromberg J.G., Wessels T.M., Krause A. Roles of genetic counselors in South Africa. J Genet Couns. 2013;22(6):753–761. doi: 10.1007/s10897-013-9606-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MSc in genetic counselling University of Ghana. https://wagmc.org/programmes/masters/msc-in-genetic-counselling/

- 6.Jenkins T. Medical genetics in South Africa. J Med Genet. 1990;27(12):760–779. doi: 10.1136/jmg.27.12.760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beighton P., Fieggen K., Wonkam A., Ramesar R., Greenberg J. UCT’s contribution to medical genetics in Africa – from the past into the future. S Afr Med J. 2012;102(6):446–448. doi: 10.7196/samj.5621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nattrass G.A. Biteback Publishing; 2017. Short History of South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stats SA Census. https://census.statssa.gov.za/ 2022. Accessed January 31, 2024.

- 10.Mhlanga D., Ndhlovu E. Explaining the demand for private in South Africa. Interdiscip J Econ Bus Law. 2021;10(2):98–118. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shisana O., Dhai A., Rensburg R., et al. Achieving high-quality and accountable universal health coverage in South Africa: a synopsis of the Lancet National Commission Report. S Afr Health Rev. 2019;2019(1):69–80. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coovadia H., Jewkes R., Barron P., Sanders D., McIntyre D. The health and health system of South Africa: historical roots of current public health challenges. Lancet. 2009;374(9692):817–834. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60951-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kromberg J.G., Krause A. Human genetics in Johannesburg, South Africa: past, present and future. S Afr Med J. 2013;103(12 suppl 1):957–961. doi: 10.7196/samj.7220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenkins T., Wilton E., Bernstein R., Nurse G.T. The genetic counselling clinic at a children’s hospital. S Afr Med J. 1973;47(40):1834–1838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kromberg J.G., Sizer E.B., Christianson A.L. Genetic services and testing in South Africa. J Community Genet. 2013;4(3):413–423. doi: 10.1007/s12687-012-0101-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kromberg J.G., Jenkins T. Prevalence of albinism in the South African Negro. S Afr Med J. 1982;61(11):383–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kromberg J., Manga P. Academic Press; 2018. Albinism in Africa: Historical, Geographic, Medical, Genetic, and Psychosocial Aspects. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krause A., Seymour H., Ramsay M. Common and founder mutations for monogenic traits in sub-saharan African populations. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2018;19:149–175. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-083117-021256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fieggen K., Milligan C., Henderson B., Esterhuizen A.I. Bardet Biedl syndrome in South Africa: a single founder mutation. S Afr Med J. 2016;106(6):72–74. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i6.11000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Honey E.M. Spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia with joint laxity (Beighton type): a unique South African disorder. S Afr Med J. 2016;106(6):54–56. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i6.10994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith D.C., Greenberg L.J., Bryer A. The hereditary ataxias: where are we now? Four decades of local research. S Afr Med J. 2016;106(6):38–41. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i6.10989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wonkam A., Ponde C., Nicholson N., Fieggen K., Ramessar R., Davidson A. The burden of sickle cell disease in Cape Town. S Afr Med J. 2012;102(9):752–754. doi: 10.7196/samj.5886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams T.N. Sickle cell disease in sub-Saharan Africa. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2016;30(2):343–358. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogers C.R. The development of insight in a counseling relationship. J Consult Psychol. May 1944;8(6):331–341. doi: 10.1037/h0061513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kessler S. Academic Press; 2013. Genetic Counselling: Psychological Dimensions. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Resta R.G. 2000. Psyche and helix: psychological aspects of genetic counseling: essays by Seymour Kessler. Ph.D. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weil J. Oxford Monographs on Medical G; 2000. Psychosocial genetic counseling. [Google Scholar]

- 28.LeRoy B.S., Veach P.M., Callanan N.P. John Wiley & Sons; 2020. Genetic Counseling Practice: Advanced Concepts and Skills. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veach P.M., LeRoy B.S., Bartels D.M. Springer Science+Business Media; 2006. Facilitating the Genetic Counseling Process: A Practice Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Veach P.M., LeRoy B.S., Callanan N.P. Springer; 2018. Facilitating the Genetic Counseling Process: Practice-Based Skills. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uhlmann W.R., Schuette J.L., Yashar B.M. John Wiley & Sons; 2011. A Guide to Genetic Counseling. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kromberg J., Jenkins T. In: Culture, Kinship and Genes: towards Cross-Cultural Genetics. Clarke A., Parsons E., editors. Palgrave Macmillan UK; 1997. Cultural influences on the perception of genetic disorders in the black population of Southern Africa; pp. 147–157. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Penn C., Watermeyer J. In: Genomics and Health in the Developing World. Oxford Mongraphs of Medical Genetics. Kumar D., editor. Oxford University Press; 2012. Sociocultural perspectives of inherited diseases in Southern Africa; pp. 568–584. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kromberg J., Jenkins T. In: Genomics and Health in the Developing World. Oxford Mongraphs of Medical Genetics. Kumar D., editor. Oxford University Press; 2012. Ethical, legal, and sociocultural issues and genetic services in South Africa; pp. 585–598. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Health professions act No. 56 of 1974. greengazette. https://www.greengazette.co.za/acts/health-professions-act_1974-056 Accessed January 31, 2024.

- 36.Harper P. CRC Press; 2010. Practical Genetic Counselling. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silber E., Kromberg J., Temlett J.A., Krause A., Saffer D. Huntington’s disease confirmed by genetic testing in five African families. Mov Disord. 1998;13(4):726–730. doi: 10.1002/mds.870130420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hayden M.R. Huntington’s Chorea in South Africa. Doctoral dissertation,. University of Cape Town, Faculty of Health Science; 1979. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://open.uct.ac.za/items/5fec8e14-7512-4729-83e4-65e6c58ae358

- 39.Greenberg J., Beatty S., Soltau H., Bryer A. A predictive testing service for Huntington disease (HD) and late onset spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA1) in Cape Town. CME Rev. 1996;14:1364–1367. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greenberg J., Bartmann L., Ramesar R., Beighton P. Retinitis pigmentosa in southern Africa. Clin Genet. 1993;44(5):232–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1993.tb03888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldberg P.A., Madden M.V., Harocopos C., Felix R., Westbrook C., Ramesar R.S. In a resource-poor country, mutation identification has the potential to reduce the cost of family management for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41(10):1250–1253. doi: 10.1007/BF02258223. discussion 1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bruwer Z., Futter M., Ramesar R. Communicating cancer risk within an African context: experiences, disclosure patterns and uptake rates following genetic testing for Lynch syndrome. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(1):53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bruwer Z. Doctoral dissertation, University of Cape Town, Faculty Health Sciences; 2011. An Investigation into Factors Which Have an Impact on Access to and Utilisation of the Genetic and Endoscopic Surveillance Clinic Offered to High-Risk Members of Known Lynch Families.https://open.uct.ac.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/9f3068a2-31eb-4cd3-8484-0f5bde851217/content [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bruwer Z., Algar U., Vorster A., et al. Predictive genetic testing in children: constitutional mismatch repair deficiency cancer predisposing syndrome. J Genet Couns. 2014;23(2):147–155. doi: 10.1007/s10897-013-9659-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wessels T.M. Doctoral dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, Faculty of Health Sciences; 2013. The Interactional Dynamics of the Genetic Counselling Session in a Multicultural, Antenatal Setting. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wessels T.M., Koole T. “There is a chance for me”–Risk communication in advanced maternal age genetic counseling sessions in South Africa. Eur J Med Genet. 2019;62(5):390–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2018.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wessels T.M., Koole T., Penn C. ‘And then you can decide’–antenatal foetal diagnosis decision making in South Africa. Health Expect. 2015;18(6):3313–3324. doi: 10.1111/hex.12322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walker A.P., Scott J.A., Biesecker B.B., Conover B., Blake W., Djurdjinovic L. Report of the 1989 Asilomar meeting on education in genetic counseling. Am J Hum Genet. 1990;46(6):1223–1230. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edwards J., Greenberg J., Sahhar M. Global awakening in genetic counseling. Nat Prec. 2008:1. doi: 10.1038/npre.2008.1574.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Edwards J.G. The transnational alliance for genetic counseling: promoting international communication and collaboration. J Genet Couns. 2013;22(6):688–689. doi: 10.1007/s10897-013-9621-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kromberg J., Parkes J., Taylor S. Genetic counselling as a developing healthcare profession: a case study in the Queensland context. Aust J Prim Health. 2006;12(1):33–39. doi: 10.1071/PY06006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clinical guidelines for genetic services. KnowledgeHub. https://knowledgehub.health.gov.za/elibrary/clinical-guidelines-genetics-services-2021 Accessed April 29, 2024.

- 53.Harper P.S., Hughes H.B., Raeburn J.A. Clinical Genetics Services into the 21st century. Summary of a Report of the Clinical Genetics Committee of the Royal College of Physicians. J R Coll Physician Lond. 1996;30(4):296–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]