Abstract

Background

Integrating family members into the care of hospitalized end-of-life patients enhances patient–family-centered care and significantly influences the experiences of patients and their families. This study used the integrative review methodology to assess the scope and effectiveness of interventions designed to facilitate family involvement in end-of-life care. It identified gaps and consolidated existing knowledge to improve nursing practices.

Methods

This integrative review encompasses both experimental and non-experimental studies. The process included problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, analysis, and integration. The literature search targeted studies describing interventions for family involvement in EOLC using databases such as PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, and Web of Science. Data evaluation was conducted by assessing the quality of the studies using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. Data analysis and integration were conducted by synthesizing the results of the selected studies and identifying the elements of family involvement using the 'Components of Family Involvement' framework.

Results

Of the 8,378 identified studies, 26 were eligible for inclusion. Interventions involving the families of patients with terminal illness varied, including programs to enhance communication among patients, families, and healthcare providers; family meetings; decision-making support; and digital visits and rounds. The findings show that these interventions improve patients’ psychological and physical comfort, family satisfaction, and communication. However, some families reported increased distress. The most frequently addressed elements of family involvement were communication and receiving information, followed by decision-making and meeting care needs. Family presence and contribution to care were the least addressed elements in the interventions.

Conclusions

This integrative review highlights the effectiveness of interventions to increase family involvement in end-of-life care, demonstrating positive impacts on patient comfort, family satisfaction, and communication. Despite progress in incorporating families into communication and decision-making, further efforts are needed to ensure their presence and direct care involvement. Future research should focus on improving these interventions to enhance scalability and support comprehensive family involvement, including digital tools for participation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12912-024-02538-z.

Keywords: Caregivers, Family, Family nursing, Humans, Terminal care

Background

Patient- and family-centered care emphasizes a collaborative approach where patients and their families are actively involved in the treatment process. Within this model, family involvement is considered a core concept, which highlights the significance of including families in both care and decision-making to enhance the health and well-being of individuals and their families [1]. Integrating family members into the care of hospitalized end-of-life (EOL) patients is particularly crucial, as it strengthens patient–family-centered care and shapes the experiences of both patients and their families during patients’ final moments [2]. This involvement ensures that care decisions are tailored to the patient, aligned with family values, and highlight dignified and personalized nursing care [2].

Family involvement has been shown in multiple studies to improve the quality of care, enhance patient health outcomes, and contribute to more efficient treatment. For example, involving families in education and meetings in the intensive care unit (ICU) was found to improve their confidence, enhance psychological well-being, increase satisfaction with communication, and reduce family conflicts [3]. When caregivers were involved in hospital discharge education, the readmission rate decreased, and treatment costs were reduced [4]. Additionally, when family members participated in medical rounds, they had a better understanding of the treatment plan and experienced greater comfort [5].

The benefits of family involvement in end-of-life care (EOLC) are well-documented. The family plays a crucial role in supporting the emotional, psychological, and social well-being of terminally ill patients, and contributes to their sense of dignity and comfort during their final moments [6]. When families of patients who died in the ICU were involved in communication, it reduced their levels of post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression [7]. Additionally, family meetings in EOLC have increased satisfaction among both families and staff while reducing resource utilization [8].

However, in hospital settings, care tends to be more centered around the medical staff and institutional practices, often prioritizing life-sustaining treatments over patient and family values. This contrasts with home care, where family presence is more frequent, and care is often more aligned with the patient’s and family’s values and preferences [9–11]. Moreover, the challenges of family involvement in EOLC were exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic, as infection-prevention policies further restricted family access in hospital settings [12]. Thus, research to explore strategies that enhance family involvement and ensure holistic EOLC for hospitalized patients is necessary.

Despite the benefits of family involvement in EOLC [2, 13], the literature on hospital-based interventions facilitating this involvement remains notably sparse [14, 15]. The integration of existing research in this area is crucial to consolidate nursing knowledge, as well as to identify effective practices and address gaps in research and implementation. Furthermore, nurses are in a pivotal position to deliver person-centered EOLC [16]. As professional caregivers in hospital settings, nurses facilitate the comfort and familiarity brought by family presence [17]. Consequently, effective nursing strategies are essential to overcome the challenges of integrating family members into hospital care, thereby addressing institutional barriers and closing gaps in practice. Therefore, strategies must be integrated to enhance family involvement in EOLC and bridge these gaps. Such efforts are central to advancing nursing practice and improving patient outcomes [18, 19]. Moreover, these insights are invaluable in developing evidence-based nursing practices that enhance family involvement, which ensures compassionate and dignified EOLC [20].

This integrative review aimed to assess the scope and effectiveness of interventions designed to enhance family involvement in the care of hospitalized EOL patients. By bridging existing knowledge gaps, this review seeks to provide a comprehensive analysis of the strategies that enable meaningful family involvement. This is essential for supporting nursing practices that address the complex dynamics of patient and family care at the patient’s EOL. Ultimately, fully integrating families into the care process contributes to attaining better patient outcomes, increased family satisfaction, and an overall improvement in the quality of EOLC.

Methods

Study design

This study was conducted according to Whittemore and Knafl’s methodology [21]. An integrative review encompasses both experimental and non-experimental studies to provide a comprehensive understanding of the research topic. Both qualitative and quantitative methodologies used in the studies included in the review were considered; this approach ensured appropriate to ensure a comprehensive understanding of interventions that facilitate family involvement in EOLC. Following Whittemore and Knafl’s guidelines [21], the process consisted of problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis, and derivation of attributes through data integration.

Problem identification

The first step in an integrative review is to clearly define the research problem. To facilitate the literature search, we formulated the following research question: “What are the characteristics of the interventions used to facilitate family involvement in EOLC for hospitalized patients?”

Literature search

For the literature search and selection, we included the following variables of interest: target population (families of hospitalized EOL patients), concept (interventions for involvement in EOLC), and context (hospitals and medical facilities where EOLC is provided). “Family” included those who provided physical, emotional, financial, or spiritual support to patients, extending beyond legal definitions [22]. Family involvement is the active engagement of families in medical decisions to support and enhance patient health [23].

To check for existing studies similar to our review, we initially searched Google Scholar, the Cochrane Library, and the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews. Based on our variables of interest, two authors developed the search strategy, with “involvement,” “end-of-life,” “inpatient,” and “family” as the key search terms. The details are provided in Additional File 1.

We conducted multiple searches across four databases (PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, and Web of Science). An initial search, performed in December 2023, helped refine the search terms, leading to searches conducted between May 1 and May 10, 2024. We mainly included studies describing interventions that facilitate family involvement in EOLC. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | a) Study Type: Peer-reviewed articles encompassing quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods research |

| b) Setting: Hospital inpatient environments | |

| c) Participants: Families of patients receiving palliative care or EOLC in a hospital setting | |

| d) Outcomes: Results concerning families, patients, and healthcare providers, or the applicability of interventions | |

| e) Interventions: Interventions involving family members in EOLC | |

| f) Language: Published in English | |

| g) Geographic Scope: Studies conducted in any country | |

| h) Publication Period: No restrictions | |

| Exclusion criteria | a) Conference abstracts, letters, posters, comments, editorials, protocols, theses, and reviews |

| b) Studies focused on support related to family bereavement following the patient’s death | |

| c) Studies analyzing the status or experiences of family involvement without any intervention |

EOLC End-of-life care

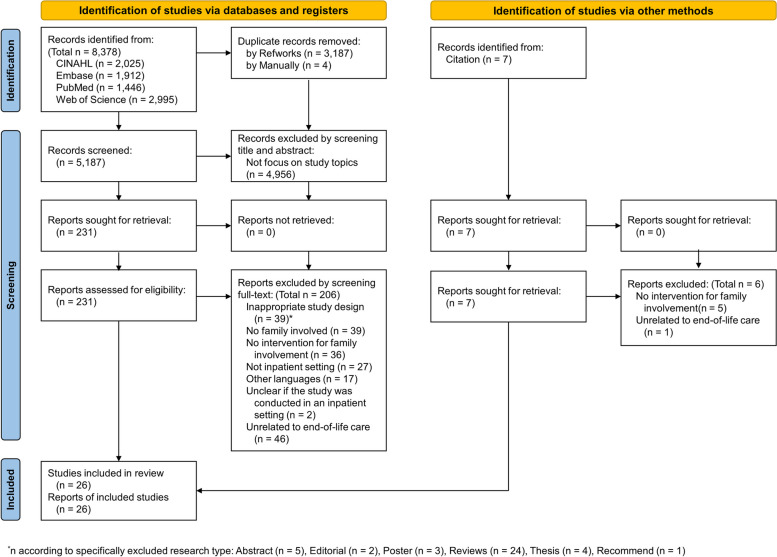

The retrieved literature was managed using RefWorks and Excel. A total of 8,378 studies were identified from the initial search of the four databases and 3,191 duplicates were removed. Each author independently reviewed the titles and abstracts, excluding 4,956 studies that were not relevant to the research topic. A total of 231 studies were deemed eligible, and their full texts were reviewed according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, 206 studies were excluded for the following reasons: inappropriate study design (n = 39), no family involved (n = 39), no intervention (n = 36), not inpatient setting (n = 27), published in languages other than English (n = 17), unclear if the study was conducted in an inpatient setting (n = 2), and unrelated to EOLC (n = 46). For studies with unclear applicability of the exclusion criteria, we contacted the authors via email for clarification. However, two studies were excluded from the review due to a lack of response regarding the study setting. For studies with unclear applicability of the exclusion criteria, we contacted the authors via email for clarification. However, two studies were excluded from the review due to a lack of response regarding the study setting. .Additional studies were identified through citation searching, adding one more study for review and resulting in a total of 26 studies being included. Discrepancies in the study selection were resolved by consensus. To visualize the study selection process, we employed a flowchart for systematic reviews (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study selection

Data evaluation

For the quality assessment of the studies included in our review, we used the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. MMAT is a unique tool that can assess the quality of various research designs [24], making it suitable for our review that incorporates multiple study designs. Two authors independently conducted quality assessments. MMAT evaluates quality by answering five questions specific to each study design, with the responses being “yes,” “no,” or “can’t tell.” A star (*) is awarded for each “yes” response, providing an overall quality score for each study [24]. For studies identified as quality improvement and pilot studies, an appropriate MMAT framework for mixed or quantitative research was used depending on the study design. However, quality assessment was not possible in such case reports [25*, 26*]. The evaluation results indicated that 7 studies met 100% of the criteria, 14 met 80%, 2 met 60%, and 1 met 40%.

Data analysis and integration

Following the guidelines set by Whittemore and Knafl, we organized and condensed the primary source data to facilitate comparisons. The extracted items included the general aspects of each study (e.g., first author, publication year, country where the study was conducted, study type, research objectives, sample size, and sample setting) and thematic content (e.g., intervention content, intervention targets, methods of intervention application, outcome measurement methods, and key outcomes). The first author conducted data extraction, which was cross-verified with the corresponding author. Any ambiguities were discussed and resolved.

To determine which aspects of family involvement each intervention encompassed, we utilized Olding et al.’s proposed framework [27]. This framework identifies five main components of family involvement, ranging from passive to active participation: (i) presence; (ii) receiving care and having needs met; (iii) communicating and receiving information; (iv) decision-making; and (v) contributing to care.

We integrated the extracted data to identify key characteristics of interventions facilitating family involvement in EOLC for hospitalized patients. The critical elements and conclusions regarding the interventions were synthesized to create an integrated summary of findings relevant to our topic.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

Characteristics of the studies included in this review are summarized in Additional File 2. Of the 26 selected studies, three were published before 2010 [26*, 28*, 29*], seven between 2012 and 2019 [25*, 30*, 31*, 32*, 33*, 34*, 35*], and 16 from 2020 to beyond [36*, 37*, 38*, 39*, 40*, 41*, 42*, 43*, 44*, 45*, 46*, 47*, 48*, 49*, 50*, 51*].

The research type included three qualitative studies [33*, 36*, 38*], five mixed-methods studies [30*, 42*, 44*, 46*, 51*], two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [41*, 50*], three non-RCT experimental studies [31*, 37*, 43*], one cohort study [48*], four pilot studies [29*, 32*, 39*, 40*], two case reports [25*, 26*], and five quality improvement [28*, 34*, 35*, 47*, 49*]. One study did not specify its design; however, given the presence of both quantitative and qualitative approaches, it was presumed to be a mixed-methods study [45*].

The studies were conducted across multiple countries: eight in the USA [26*, 28*, 35*, 39*, 46*, 49*, 50*, 51*], six in Australia [29*, 32*, 34*, 36*, 38*, 41*], five in Canada [30*, 31*, 46*, 48*, 51*], three in the UK [40*, 42*, 47*], and one each in Sweden [33*], Spain [37*], Ireland [25*], Thailand [43*], Taiwan [44*], and Italy [45*]. The studies by Neville et al. [46*] and Vanstone et al. [51*] were conducted in more than one country because of their multicenter nature.

The setting also varied, with five studies conducted in ICUs [28*, 33*, 46*, 50*, 51*] and 17 in non-ICU wards [29*, 30*, 31*, 32*, 34*, 35*, 36*, 38*, 39*, 41*, 42*, 43*, 44*, 45*, 47*, 48*, 49*]. One case report covered both the general ward and ICU and discussed cases involving patients’ family members [26*]. Three studies did not specify their units [25*, 37*, 40*].

Characteristics of the interventions

The types of interventions aimed at promoting family involvement were diverse. Four studies implemented family meetings [29*, 31*, 34*, 41*], and one augmented family meetings with preparatory interactions and orientations [50*]. Three studies implemented the “3 Wishes Project” to tailor EOLC to patients’ and families’ preferences [46*, 48*, 51*].

Four studies developed programs to involve families in communication with healthcare providers [28*, 38*, 40*, 42*], and one applied a card-based tool to facilitate EOL communication between patients and families [26*]. One study involved families in EOL communication using a set of questions designed to involve both patients and families in palliative conversations [30*].

In three studies, families were involved in interventions aimed at reducing patient discomfort and promoting relaxation, including music therapy [35*], multi-sensory experiences in a “human room” [36*], and virtual reality (VR) system use [47*].

Four studies implemented complex interventions serving multiple purposes, including information provision, support, decision-making, and education to improve patient care skills [32*, 37*, 43*, 49*].

One study involved parents in EOLC strategies for infants shortly after birth, allowing active participation in caring for terminally ill babies [39*]. Another study examined family involvement in clinical rounds conducted online [45*]. Additionally, research explored family visits to the patient’s room via Skype and communication with the medical team [25*]. One other study applied an intervention that shared ICU diaries with families [33*]. Lin et al. [44*] devised a communication coaching intervention and meeting tailored to the country’s cultural context, involving families and patients in discussions of advance care planning.

When examining the mode of intervention application, 11 studies applied face-to-face methods [26*, 32*, 33*, 35*, 38*, 39*, 43*, 46*, 48*, 49*, 51*], three applied digital methods [25*, 45*, 47*], and four applied both face-to-face and digital [34*, 36*, 37*, 50*]. Additionally, eight studies did not clearly specify the mode of application [28*, 29*, 30*, 31*, 40*, 41*, 42*, 44*].

Applying the family involvement framework

The interventions performed in the studies included in this review were compared using a framework to identify the elements of family involvement (Table 2). The most frequently addressed element was “communicating and receiving information,” which was applied in 20 studies [25*, 26*, 28*, 29*, 30*, 31*, 32*, 33*, 34*, 37*, 38*, 39*, 40*, 41*, 42*, 43*, 44*, 45*, 49*, 50*]. The element of “Decision making” was covered in 13 studies [26*, 28*, 29*, 31*, 34*, 38*, 40*, 41*, 42*, 43*, 44*, 45*, 50*], and “Receiving care and having needs met” was also addressed in 13 studies [25*, 32*, 33*, 34*, 37*, 39*, 43*, 44*, 46*, 48*, 49*, 50*, 51*]. The element of “Contributing to care” was covered in five studies [35*, 36*, 39*, 43*, 47*], while that of “Presence” was included in three studies [25*, 36, 39]. Except for six [30*, 35*, 46*, 47*, 48*, 51*], all other studies addressed at least two elements, but none covered all five.

Table 2.

Components of family involvement framework

| 1st Author (Year) | Components of Family Involvement Framework | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence | Receiving care and having needs met | Communicating and receiving information | Decision making | Contributing to care | |

| Ahrens, T. (2003) [28*] | V | V | |||

| Batchelor, C. (2023) [36*] | V | V | |||

| Battley, J. E. (2012) [25*] | V | V | V | ||

| Beneria, A. (2021) [37*] | V | V | |||

| Cahill, P. J. (2021) [38*] | V | V | |||

| Czynski, A. J. (2022) [39*] | V | V | V | V | |

| Duke, S. (2020) [40*] | V | V | |||

| Guo, Q. (2018) [30*] | V | ||||

| Hannon, B. (2012) [31*] | V | V | |||

| Hudson, P. (2009) [29*] | V | V | |||

| Hudson, P. (2012) [32*] | V | V | |||

| Hudson, P. (2021) [41*] | V | V | |||

| Johansson, M. (2018) [33*] | V | V | |||

| Johnson, H. (2020) [42*] | V | V | |||

| Klankaew, S. (2023) [43*] | V | V | V | V | |

| Lin, C. (2020) [44*] | V | V | V | ||

| Menkin, E. S. (2007) [26*] | V | V | |||

| Mercadante, S. (2020) [45*] | V | V | |||

| Neville, T. H. (2020) [46*] | V | ||||

| Nwosu, A. C. (2024) [47*] | V | ||||

| Reid, J. C. (2023) [48*] | V | ||||

| Sanderson, C. R. (2017) [34*] | V | V | V | ||

| Smith, S. (2020) [49*] | V | V | |||

| Suen, A. O. (2021) [50*] | V | V | V | ||

| Vanstone, M. (2020) [51*] | V | ||||

| Wood, C. (2019) [35*] | V | ||||

V: Relevant to the element

Outcome of the intervention

The outcomes of each intervention were examined according to the study design. Studies categorized as quality improvement and pilot studies were reported together with mixed-method and non-RCT experimental studies, according to design type.

In three qualitative studies and two case reports, participant perceptions of the interventions were assessed, and they were perceived positively overall. Patients and caregivers experienced relaxation and psychological comfort through an intervention called “Human Room” [36*]. The intervention “VOICE,” which facilitates communication, offered both patients and caregivers the opportunity to address their needs and be involved in EOL discussions [38*]. Sharing ICU diary was found to enhance emotional and rational understanding, especially among family members [33*].

In the two case reports, the interventions facilitated communication between patients and their families [25*], and the benefits of promoting conversations related to EOLC were emphasized [26*].

RCTs demonstrated varied outcomes, with one study noting reduced distress and increased preparedness among family caregivers following structured family meetings [41*]. Another study found improvements in communication quality and shared decision-making after intervention, but the differences were not statistically significant [50*].

There were 10 non-RCT studies. In studies with enhanced family communication, patients in the experimental group had shorter hospital stays and lower costs, although mortality rates showed no statistical significance compared with the control group [28*]. Family meetings reduced family concerns and nursing demands [31*], while educational programs improved family preparedness but not psychological well-being [32*]. Another education program reported benefits such as reduced hospital stays [49*] and decreased patient anxiety through nurse-led interventions [43*]. Music therapy led to reduced anxiety and pain in patients, while families experienced stress relief [35*]. Patients and families in VR promoted relaxation [47*], and one study emphasized that the EOL intervention program provided an opportunity for family members to say goodbye to their loved ones as a meaningful aspect [37*]. Two studies, where outcomes for the intervention were obtained solely from medical staff, indicated that family-involved interventions benefited patient–family dynamics and were well received by nurses [39*, 40*]. However, some interventions paradoxically induced distress among family members [40*].

Additionally, a cohort study detailed the cost aspects of the 3 Wishes Project, which grants personal, spiritual, and relational wishes to dying patients and their families. The study found that 91% of wishes incurred no cost, with the cost of fulfilling wishes ranging from $0 to $86 [48*].

Eight mixed-method studies integrated qualitative results to examine the perceptions of the interventions, categorizing them into benefits and barriers. The benefits included involving family participation helping families better understand the patient [34*], and giving families a sense of family involvement [51*]. Additionally, these interventions provided opportunities to discuss important issues [34*, 44*]. Other benefits included reducing the family’s pain from loss [46*], respecting the values of patients and families [30*], and enhancing the family’s sense of happiness [45*]. Barriers included inconsistent family involvement [42*] and the challenges of replacing face-to-face interactions with online rounds [45*]. Some family members of terminal patients may feel increased distress due to the proximity [51*]. Quantitative analyses generally supported the positive effects of the interventions, such as usefulness, helpfulness, provision of information, and reduction in the frequency and impact of worries [29*, 34*, 45*]. However, some families found the interventions to be distressing [34*].

Discussion

This integrative review critically examined interventions aimed at enhancing family involvement in EOLC for hospitalized patients. The results based on the framework proposed by Olding et al. [27] showed that the element of “communicating and receiving information” was the most frequently addressed, appearing in 20 studies. In contrast, “Presence” was the least addressed, noted in only three studies. Although the interventions generally supported patients and families emotionally and psychologically, improved family readiness for EOLC, and aided in decision-making, concerns have been raised about increased distress among some family members due to their involvement.

This integrative review aligns with the principles of person- and family-centered nursing, confirming the pivotal role of family during EOLC in hospitals. Such integration maintains the patient’s dignity and comfort and aids the family in coping with their loved one’s terminal phase. This is similar to the findings of Cuenca et al. [52], which demonstrated that family-centered care, where families are actively involved in patient treatment, leads to greater satisfaction with both the treatment and the decision-making process.

Applying a family involvement framework to the interventions identified in this review accentuates the notable trends and disparities in the current practices of family involvement in EOLC in hospital settings. Particularly, the emphasis on “communicating and receiving information” in 20 studies highlights the critical need for clear and consistent information provision in hospitals, which is essential for families to understand patients’ conditions, expected outcomes, and treatment processes. This trend reflects the importance of transparent communication, as emphasized by Cox et al. [53], suggesting that well-informed families are better equipped to make complex decisions during the final stages of life. This significantly reduces stress and anxiety among patients and their families. Furthermore, effective communication between families and healthcare providers is crucial for facilitating a “good death,” a fact reiterated by the findings of Anderson et al. [54]. These results validate the need for clarity and support in EOLC discussions, emphasizing the pivotal role of informed and compassionate communication in enhancing patient and family satisfaction.

“Decision-making” and “Receiving care and having needs met” were prominently featured in 13 studies each. The emphasis on decision-making reflects the findings of Hinkle, Bosslet, and Torke [55], which suggest that family involvement in the decision-making process enhances the appropriateness of medical decisions and improves treatment adherence and patient satisfaction. Additionally, as demonstrated by Epstein et al. [9], this aspect is crucial because it ensures that care decisions align with the values and preferences of patients and their families. This is particularly important in EOL scenarios, where ethical dilemmas are frequent, and family perspectives can provide critical insights into patient preferences [56]. Bužgová et al. [57] emphasize the importance of family involvement in identifying and meeting the needs of the patient’s family. The present study found a positive correlation between the extent to which the needs of the families of terminally ill cancer patients were met and their quality of life. Additionally, Pringle, Johnston, and Buchanan [58] note that meeting the needs of families can facilitate the provision of comprehensive and empathetic care, offering a person-centered approach to EOLC. This type of involvement is crucial to ensure that the EOLC proceeds in a manner that respects the patient’s dignity.

The element of “presence” was the least frequently addressed in interventions related to family involvement. Patients, families, and healthcare providers consider family presence to be crucial for achieving a “good death” [59]. In a study of nursing managers, all participants agreed that family presence is vital in EOLC [60]. This perception may suggest that family presence is already well-implemented, which could partly explain why fewer interventions specifically target it. However, recognizing its importance does not always ensure that families can attend or feel comfortable being present. Emotional barriers, such as fear or hesitation to witness the process of dying [61], coupled with restrictive hospital policies and spatial limitations, often prevent family presence [62]. These barriers were particularly emphasized during public health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic [63], indicating that even if families wish to be present, the hospital system may not always support it. Therefore, despite the recognition of the importance of family presence, further research is needed to thoroughly explore the context behind the lack of interventions. Additionally, further research is needed to explore how emotional and logistical barriers can be addressed in interventions to ensure that family presence is genuinely integrated into EOLC.

While direct family involvement in caregiving activities within ICU settings is not always specific to EOLC, Goldfarb, Bibas, and Burns [64] highlighted its benefits. They found that when families are involved in patient care, collaboration with the medical team improves, and families feel more respected, thereby yielding significant benefits. However, as reported by Krewulak et al. [65], not all families desire or are comfortable with direct involvement in caregiving tasks, suggesting a need for a cautious and personalized approach. This indicates that, while family involvement can enhance the care process and satisfaction, it should be tailored to the preferences and capabilities of each family to ensure that their involvement has a positive impact on the patient’s care environment. Therefore, addressing these gaps could enhance the therapeutic potential of family presence and significantly improve the quality of EOLC treatment.

While significant strides have been made in involving families in communication and decision-making in hospital-based EOLC, more efforts are needed to incorporate them fully into all aspects of care. It is essential to address existing gaps in family involvement in hospital-based care by developing innovative strategies that encourage the involvement of family members, through both their presence and direct caregiving activities. Future research should aim to bridge these gaps by exploring innovative strategies that facilitate family involvement in direct care activities.

This review identified several ways in which digital technologies can involve families in EOLC. Carlucci et al. [66] and Gorman et al. [67] demonstrated how digital applications can facilitate family communication and decision-making from a distance, enhancing the quality of care without the need for physical presence. Additionally, Goulabchand et al. [68] suggested that the introduction of digital tablets in EOL scenarios can provide isolated hospital patients with a means to connect with their families. This aids the family’s grieving process and ensures connectivity and informed involvement regardless of location. These findings support the need for a broader implementation of digital tools to promote inclusivity and compassion.

A significant limitation noted across the reviewed studies is the reliance on self-reported measures from families, which may introduce response bias and affect the reliability of the data. The diversity in measurement tools and outcome variables across studies further complicates the ability to synthesize data or propose standardized evaluative metrics. Future research should focus on developing validated objective measures, as suggested by Goldfarb et al. [69], to accurately assess the true impact of family involvement on patient and family outcomes.

Conclusion

Integrating families into the care of hospitalized patients during their EOL is a key component of the evolving nursing care paradigm. This review highlights the positive effects and challenges of existing interventions. Significant progress has been made in incorporating families into communication and decision-making processes in hospital-based EOLC; however, there remains a need to further expand family involvement and ensure their active presence across all aspects of care. Therefore, we propose clear directions for future research to bridge these gaps and improve practice guidelines. By pursuing these identified needs, nursing professionals can enhance the quality of EOLC and provide more meaningful support to families during critical times, as emphasized by Morgan and Gazarian [70]. Meeting these needs can significantly improve the quality of EOLC by aligning it with patient- and family-centered practices, as outlined in the best practice guidelines for nursing.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table 1. Search strategies according to each database.

Additional File 2: Table 2. Characteristics of included studies.

Additional file 3: Table 3. PRISMA Checklist.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Peter Hudson for his invaluable assistance in referencing studies related to family involvement in end-of-life care.

Abbreviations

- EOL

End-of-life

- EOLC

End-of-life care

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- MMAT

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- VR

Virtual reality

Authors’ contributions

YK and DK collaboratively designed the methodology; performed the article search, article selection, and data extraction; and contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. Additionally, YK was responsible for writing the original draft of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Data availability

This study is based on previously published literature. All data analyzed during this study are cited in the manuscript and detailed in the Supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

* Articles included in the review

- 1.Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. What is PFCC? [Internet]. McLean, VA: Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care; [cited 2024 May 12]. Available from: https://www.ipfcc.org/about/pfcc.html.

- 2.Wiegand DL, Grant MS, Cheon J, Gergis MA. Family-centered end-of-life care in the ICU. J Gerontol Nurs. 2013. 10.3928/00989134-20130530-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, Puntillo KA, Kross EK, Hart J, et al. Guidelines for family-centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodakowski J, Rocco PB, Ortiz M, Folb B, Schulz R, Morton SC, et al. Caregiver integration during discharge planning for older adults to reduce resource use: a metaanalysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017. 10.1111/jgs.14873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aronson PL, Yau J, Helfaer MA, Morrison W. Impact of Family Presence During Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Rounds on the Family and Medical Team. Pediatrics. 2009. 10.1542/peds.2009-0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulcahy Symmons S, Ryan K, Aoun SM, Selman LE, Davies AN, Cornally N, et al. Decision-making in palliative care: patient and family caregiver concordance and discordance-systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2023. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2022-003525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, Joly LM, Chevret S, Adrie C, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007. 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Billings JA. The end-of-life family meeting in intensive care part I: Indications, outcomes, and family needs. J Palliat Med. 2011. 10.1089/jpm.2011.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein RM, Fiscella K, Lesser CS, Stange KC. Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010. 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelleher K, Hardy RY. Coming full circle (to hard questions): Patient- and family-centered care in the hospital context. Fam Syst Health. 2020. 10.1037/fsh0000497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, Matulonis UA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. Place of death: correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers’ mental health. J Clin Oncol. 2010. 10.1200/jco.2009.26.3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim Y, Kim DH. Nurses’ experience of end-of-life care for patients with COVID-19: A descriptive phenomenology study. Nurs Health Sci. 2024. 10.1111/nhs.13124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forbat L, François K, O’Callaghan L, Kulikowski J. Family meetings in inpatient specialist palliative care: a mechanism to convey empathy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breen LJ, Aoun SM, O’Connor M, Rumbold B. Bridging the gaps in palliative care bereavement support: an international perspective. Death Stud. 2014. 10.1080/07481187.2012.725451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hudson PL, Trauer T, Graham S, Grande G, Ewing G, Payne S, et al. A systematic review of instruments related to family caregivers of palliative care patients. Palliat Med. 2010. 10.1177/0269216310373167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevenson-Baker S. Promoting person-centred care at the end of life. Nurs Stand. 2023. 10.7748/ns.2023.e12171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higginson IJ, Evans CJ. What is the evidence that palliative care teams improve outcomes for cancer patients and their families? Cancer J. 2010. 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181f684e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, Sofaer S, Adams K, Bechtel C, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santana MJ, Ahmed S, Fairie P, Zelinsky S, Wilkinson G, McCarron TL, et al. Co-developing patient and family engagement indicators for health system improvement with healthcare system stakeholders: a consensus study. BMJ Open. 2023. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-067609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, Hannon B, Leighl N, Oza A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62416-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shin JW, Choi J, Tate J. Interventions using digital technology to promote family engagement in the adult intensive care unit: an integrative review. Heart Lung. 2023. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2022.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown SM, Rozenblum R, Aboumatar H, Fagan MB, Milic M, Lee BS, et al. Defining patient and family engagement in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(3):358–60. 10.1164/rccm.201410-1936LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf. 2018. 10.3233/efi-180221.

- 25.*Battley JE, Balding L, Gilligan O, O'Connell C, O'Brien T. From Cork to Budapest by Skype: living and dying. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2012. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000210. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.*Menkin ES. Go Wish: a tool for end-of-life care conversations. J Palliat Med. 2007. 10.1089/jpm.2006.9983. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Olding M, McMillan SE, Reeves S, Schmitt MH, Puntillo K, Kitto S. Patient and family involvement in adult critical and intensive care settings: a scoping review. Health Expect. 2016. 10.1111/hex.12402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.*Ahrens T, Yancey V, Kollef M. Improving family communications at the end of life: implications for length of stay in the intensive care unit and resource use. Am J Crit Care. 2003;12(4):317–24. 10.4037/ajcc2003.12.4.317. [PubMed]

- 29.*Hudson P, Thomas T, Quinn K, Aranda S. Family meetings in palliative care: are they effective? Palliat Med. 2009. 10.1177/0269216308099960. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.*Guo Q, Chochinov HM, McClement S, Thompson G, Hack T. Development and evaluation of the Dignity Talk question framework for palliative patients and their families: a mixed-methods study. Palliat Med. 2018. 10.1177/0269216317734696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.*Hannon B, O'Reilly V, Bennett K, Breen K, Lawlor PG. Meeting the family: measuring effectiveness of family meetings in a specialist inpatient palliative care unit. Palliat Support Care. 2012; 10.1017/s1478951511000575. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.*Hudson PL, Trauer T, Lobb E, Zordan R, Williams A, Quinn K, et al. Supporting family caregivers of hospitalised palliative care patients: a psychoeducational group intervention. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2012. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2011-000131. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.*Johansson M, Wåhlin I, Magnusson L, Runeson I, Hanson E. Family members' experiences with intensive care unit diaries when the patient does not survive. Scand J Caring Sci. 2018. 10.1111/scs.12454. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.*Sanderson CR, Cahill PJ, Phillips JL, Johnson A, Lobb EA. Patient-centered family meetings in palliative care: a quality improvement project to explore a new model of family meetings with patients and families at the end of life. Ann Palliat Med. 2017. 10.21037/apm.2017.08.11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.*Wood C, Cutshall SM, Wiste RM, Gentes RC, Rian JS, Tipton AM, et al. Implementing a palliative medicine music therapy program: a quality improvement project. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019. 10.1177/1049909119834878. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.*Batchelor C, Brand G, Soropos E, Auret K. Qualitative insights into the palliative care experience of a hospice-based sensory room. Arts & Health. 2023. 10.1080/17533015.2021.2014539. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.*Beneria A, Castell-Panisello E, Sorribes-Puertas M, Forner-Puntonet M, Serrat L, García-González S, et al. End of life intervention program during COVID-19 in Vall d'Hebron University Hospital. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2021. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.608973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.*Cahill PJ, Lobb EA, Sanderson CR, Phillips JL. Patients receiving palliative care and their families' experiences of participating in a “patient-centered family meeting”: a qualitative substudy of the valuing opinions, individual communication, and experience feasibility trial. Palliat Med Rep. 2021. 10.1089/pmr.2020.0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.*Czynski AJ, Souza M, Lechner BE. The mother baby comfort care pathway: the development of a rooming-in-based perinatal palliative care program. Adv Neonatal Care. 2022. 10.1097/anc.0000000000000838. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.*Duke S, Campling N, May CR, Lund S, Lunt N, Hospital to Home Co-researcher group, et al. Co-construction of the family-focused support conversation: a participatory learning and action research study to implement support for family members whose relatives are being discharged for end-of-life care at home or in a nursing home. BMC Palliat Care. 2020. 10.1186/s12904-020-00647-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.*Hudson P, Girgis A, Thomas K, Philip J, Currow DC, Mitchell G, et al. Do family meetings for hospitalised palliative care patients improve outcomes and reduce health care costs? a cluster randomised trial. Palliat Med. 2021. 10.1177/0269216320967282. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.*Johnson H, Yorganci E, Evans CJ, Barclay S, Murtagh FE, Yi D, et al. Implementation of a complex intervention to improve care for patients whose situations are clinically uncertain in hospital settings: a multi-method study using normalisation process theory. PloS one. 2020. 10.1371/journal.pone.0239181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.*Klankaew S, Temthup S, Nilmanat K, Fitch MI. The effect of a nurse-led family involvement program on anxiety and depression in patients with advanced-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Healthcare. 2023. 10.3390/healthcare11040460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.*Lin C-P, Evans CJ, Koffman J, Chen P-J, Hou M-F, Harding R. Feasibility and acceptability of a culturally adapted advance care planning intervention for people living with advanced cancer and their families: a mixed methods study. Palliat Med. 2020. 10.1177/0269216320902666. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.*Mercadante S, Adile C, Ferrera P, Giuliana F, Terruso L, Piccione T. Palliative care in the time of COVID-19. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.*Neville TH, Clarke F, Takaoka A, Sadik M, Vanstone M, Phung P, et al. Keepsakes at the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.*Nwosu AC, Mills M, Roughneen S, Stanley S, Chapman L, Mason SR. Virtual reality in specialist palliative care: a feasibility study to enable clinical practice adoption. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2024. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.*Reid JC, Dennis B, Hoad N, Clarke F, Hanmiah R, Vegas DB, et al. Enhancing end of life care on general internal medical wards: the 3 Wishes Project. BMC Palliat Care. 2023. 10.1186/s12904-023-01133-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.*Smith S, Wilson CM, Lipple C, Avromov M, Maltese J, Siwa Jr E, et al. Managing palliative patients in inpatient rehabilitation through a short stay family training program. Am J Hosp Palliat Med®. 2020. 10.1177/1049909119867293. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.*Suen AO, Butler RA, Arnold RM, Myers B, Witteman HO, Cox CE, et al. A pilot randomized trial of an interactive web-based tool to support surrogate decision makers in the intensive care unit. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021. 10.1513/annalsats.202006-585oc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.*Vanstone M, Neville TH, Clarke FJ, Swinton M, Sadik M, Takaoka A, et al. Compassionate end-of-life care: mixed-methods multisite evaluation of the 3 Wishes Project. Ann Intern Med. 2020. 10.7326/m19-2438. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Cuenca JA, Manjappachar N, Nates J, Mundie T, Beil L, Christensen E, et al. Humanizing the intensive care unit experience in a comprehensive cancer center: a patient- and family-centered improvement study. Palliat Support Care. 2022. 10.1017/s1478951521001838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cox CE, Lewis CL, Hanson LC, Hough CL, Kahn JM, White DB, et al. Development and pilot testing of a decision aid for surrogates of patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2012. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182536a63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anderson RJ, Bloch S, Armstrong M, Stone PC, Low JT. Communication between healthcare professionals and relatives of patients approaching the end-of-life: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. Palliat Med. 2019. 10.1177/0269216319852007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hinkle LJ, Bosslet GT, Torke AM. Factors associated with family satisfaction with end-of-life care in the ICU: a systematic review. Chest. 2015. 10.1378/chest.14-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akdeniz M, Yardımcı B, Kavukcu E. Ethical considerations at the end-of-life care. SAGE Open Med. 2021. 10.1177/20503121211000918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bužgová R, Špatenková N, Fukasová-Hajnová E, Feltl D. Assessing needs of family members of inpatients with advanced cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2016. 10.1111/ecc.12441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pringle J, Johnston B, Buchanan D. Dignity and patient-centred care for people with palliative care needs in the acute hospital setting: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2015. 10.1177/0269216315575681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yun YH, Kim KN, Sim JA, Kang E, Lee J, Choo J, et al. Priorities of a “good death” according to cancer patients, their family caregivers, physicians, and the general population: a nationwide survey. Support Care Cancer. 2018. 10.1007/s00520-018-4209-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Foster JR, Lee LA, Seabrook JA, Ryan M, Betts LJ, Burgess SA, et al. Family presence in Canadian PICUs during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-methods environmental scan of policy and practice. CMAJ Open. 2022. 10.9778/cmajo.20210202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.García-Navarro EB, Garcia Navarro S, Cáceres-Titos MJ. How to manage the suffering of the patient and the family in the final stage of life: A qualitative study. Nursing Reports. 2023. 10.3390/nursrep13040141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kisorio LC, Langley GC. End-of-life care in intensive care unit: family experiences. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2016. 10.1016/j.iccn.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tabah A, Elhadi M, Ballard E, Cortegiani A, Cecconi M, Unoki T, et al. Variation in communication and family visiting policies in intensive care within and between countries during the Covid-19 pandemic: the COVISIT international survey. J Crit Care. 2022. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2022.154050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goldfarb M, Bibas L, Burns K. Patient and family engagement in care in the cardiac intensive care unit. Can J Cardiol. 2020. 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krewulak KD, Sept BG, Stelfox HT, Ely EW, Davidson JE, Ismail Z, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of family administration of delirium detection tools in the intensive care unit: a patient-oriented pilot study. CMAJ Open. 2019. 10.9778/cmajo.20180123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Carlucci M, Carpagnano LF, Dalfino L, Grasso S, Migliore G. Stand by me 2.0. Visits by family members at Covid-19 time. Acta Biomed. 2020. 10.23750/abm.v91i2.9569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Gorman K, MacIsaac C, Presneill J, Hadley D, Nolte J, Bellomo R. Successful implementation of a short message service (SMS) as intensive care to family communication tool. Crit Care Resusc. 2020. 10.1016/S1441-2772(23)00389-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Goulabchand R, Boclé H, Vignet R, Sotto A, Loubet P. Digital tablets to improve quality of life of COVID-19 older inpatients during lockdown. Eur Geriatr Med. 2020. 10.1007/s41999-020-00344-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goldfarb M, Debigaré S, Foster N, Soboleva N, Desrochers F, Craigie L, et al. Development of a family engagement measure for the intensive care unit. CJC Open. 2022. 10.1016/j.cjco.2022.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Morgan J, Gazarian P. A good death: A synthesis review of concept analyses studies. Collegian. 2023. 10.1016/j.colegn.2022.08.006. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table 1. Search strategies according to each database.

Additional File 2: Table 2. Characteristics of included studies.

Additional file 3: Table 3. PRISMA Checklist.

Data Availability Statement

This study is based on previously published literature. All data analyzed during this study are cited in the manuscript and detailed in the Supplementary information files.