Abstract

Background

SARS-CoV-2 transmission and COVID-19 disease severity is influenced by immunity from natural infection and/or vaccination. Population-level immunity is complicated by the emergence of viral variants. Antibody Fc-dependent effector functions are as important mediators in immunity. However, their induction in populations with diverse infection and/or vaccination histories and against variants remains poorly defined.

Methods

We evaluated Fc-dependent functional antibodies following vaccination with two widely used vaccines, AstraZeneca (AZ) and Sinovac (SV), including antibody binding of Fcγ-receptors and complement-fixation in vaccinated Brazilian adults (n = 222), some of who were previously infected with SARS-CoV-2, as well as adults with natural infection only (n = 200). IgG, IgM, IgA, and IgG subclasses were also quantified.

Results

AZ induces greater Fcγ-receptor-binding (types I, IIa, and IIIa/b) antibodies than SV or natural infection. Previously infected individuals have significantly greater vaccine-induced responses compared to naïve counterparts. Fcγ-receptor-binding is highest among AZ vaccinated individuals with a prior infection, for all receptor types, and substantial complement-fixing activity is only seen among this group. SV induces higher IgM than AZ, but this does not drive better complement-fixing activity. Some SV responses are associated with subject age, whereas AZ responses are not. Importantly, functional antibody responses are well retained against the Omicron BA.1 S protein, being best retained for Fcγ-receptor-1 binding, and are higher for AZ than SV.

Conclusions

Hybrid immunity, from combined natural exposure and vaccination, generates strong Fc-mediated antibody functions which may contribute to immunity against evolving SARS-CoV-2 variants. Understanding determinants of Fc-mediated functions may enable future vaccines with greater efficacy against different variants.

Subject terms: Viral infection, DNA vaccines, Inactivated vaccines

Plain language summary

Antibodies are proteins produced as part of the immune response that identify and prevent the negative consequences of infections. We studied antibody responses produced following vaccination with two different COVID-19 vaccines in adults, some of whom previously had COVID-19. Differences were seen in the antibodies produced, with more active antibodies produced in people who had previously had COVID-19. There were also differences in how effective the antibodies were against different viral variants. This improved understanding of antibody responses could inform the development of future vaccines to improve their impact against infection with viral variants.

Harris et al. evaluate Fc-dependent functional antibodies with two widely used COVID vaccines in vaccinated Brazilian adults. Vaccine and natural immunity underlie the differences observed in Fcγ-receptor-binding (types I, IIa, and IIIa/b), IgG, IgM, and IgA production, and complement-fixing antibodies.

Introduction

The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in December 2019 has caused more than 770 million cases of COVID-19 and nearly 7 million deaths globally by November 20231. The development and deployment of efficacious vaccines formulated on the original ancestral (Hu-1) strain has helped reduce the global burden of COVID-19, however, this progress is threatened by the emergence of variants of concern (VOCs). Most primary-series vaccinations consisted of early vaccines based on the ancestral isolate, while current booster doses are formulated on contemporary Omicron isolates (currently XBB1.5 [November 2023]). Ongoing SARS-CoV-2 transmission and COVID-19 disease in populations is influenced by hybrid immunity induced by partial vaccine coverage and acquired from natural infections. A large proportion of the global population remains unvaccinated but may have naturally acquired immunity following infection with SARS-CoV-2. Different vaccines used globally may elicit different antibody response profiles, and the magnitude and protective functions of vaccine-induced antibodies are also affected by acquired immunity from prior SARS-CoV-2 infections. Greater knowledge of the specificity and functions of vaccine-induced immunity globally is needed to define vaccination regimens, optimal vaccination coverage, understand the impact of VOCs, and inform next-generation vaccines.

Disease burden and mortality rates were particularly high in Brazil, and the Oxford-AstraZeneca (ChAdOx1-S) (AZ) and Sinovac Biotech CoronaVac (SV) vaccines were approved for emergency use in early 20212. These vaccines were used extensively in Brazil3. Globally, these vaccines are being deployed at mass-scale with over 1.5 billion doses of AZ and 1.8 billion doses of SV delivered world-wide in 20214, and they continue to be used as part of COVID-19 vaccine access programs in Africa, such as COVAX5.

The AZ vaccine is a viral vector-based vaccine that uses an adenovirus derived from chimpanzees to deliver coding sequences of the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein involved in viral attachment and entry into host cells. Conversely, the SV vaccine uses inactivated virus containing the full range of proteins, including the S protein. A retrospective cohort study of over 75 million vaccinated Brazilians concluded that AZ and SV were associated with a 78.1% and 53.2% reduced risk of symptomatic illness, and a 92.3% and 73.7% reduced risk of death against the Gamma P.1 VOC, respectively6. However, a deeper understanding of the protective immune profiles induced by these vaccines is necessary to inform optimal booster policy and understand the retention of protection against VOCs.

The generation of SARS-CoV-2 specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) correlates strongly with vaccine efficacy7 and protection against severe disease8,9. These antibodies can neutralise SARS-CoV-2 virions primarily by binding to the receptor binding domain (RBD) of the S protein to prevent viral entry into host cells via angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2)10. The protective association of neutralising antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 infection and disease has been well documented7,9,11. However, studies have reported reduced neutralising titres in AZ12 and SV13,14 vaccinated individuals against the Omicron (BA.1/B.1.1.529) VOC, which has 15 mutations in the RBD compared to the ancestral vaccine strain15, leading to increased breakthrough infections. Despite the loss of antibody neutralising activity against Omicron and other VOCs, the vaccines still confer significant efficacy suggesting roles for other immune mechanisms in immunity.

An immunologic mechanism that is being increasingly recognised in immunity against SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogens is the role of antibodies engaging immune cells and the complement system via the fragment crystallisable region (Fc). These Fc-dependent effector functions have previously been identified as correlates of protection against other viruses such as influenza16, HIV17,18, and Ebola19. These functions can also be mediated by antibodies against epitopes outside the RBD20. While less studied than virus neutralisation, Fc-dependent effector functions likely contribute to protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection and may be of particular importance in protection against emerging VOCs with RBD mutations where neutralisation potency is diminished.

IgG bound to antigens can engage Fcγ receptor III (FcγRIII), which is highly expressed on natural killer (NK) cells and mediates direct killing of virally infected cells via antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC)21. IgG can also engage FcγRI, FcγRIIa, and FcγRIIIa and FcγRIIIb, expressed on phagocytic cells (e.g., macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils) and promote antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) and clearance of virions22. FcγRs are specific for IgG and do not bind IgM nor IgA isotypes. FcγRI is a high-affinity receptor that readily binds IgG, whereas FcγRIIa and FcγRIII are low-affinity receptors which require multivalent binding by multiple IgG molecules for activation23. These Fc-effector functions have been shown to improve survival in SARS-CoV-2 challenge mouse models using Fc engineered monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and FcγR deletion studies24–26, and observational studies of hospitalised patients27. Antibody dependent complement deposition (ADCD) contributes to host immune defence by promoting enhanced antibody neutralisation, inflammation, direct lysis, and phagocytosis of pathogens through binding to complement receptors28. IgG complexes and pentameric IgM can both fix complement component C1q, activating the classical pathway of the complement system. While complement activation likely contributes to optimal protection against SARS-CoV-2, appropriate regulation is essential as elevated levels of downstream complement factors have been associated with severe disease and death29,30.

Few studies have evaluated Fc-dependent functional antibody responses induced by vaccination with AZ or SV vaccines, especially in large cohorts. Greater knowledge is important given the extensive use of these vaccines globally and the continuing COVID-19 pandemic. An early phase 1/2 trial found that AZ vaccination induced greater ADCC, ADCP, and ADCD functions compared to unvaccinated COVID-19 patients with mild disease31. Detectable levels of anti-S antibodies with ADCP activity have been demonstrated following SV vaccination, however, responses were less than that of convalescent individuals32. Encouragingly, retention of antibodies that bind FcγRIIa- and FcγRIII following SV vaccination has been reported between the ancestral and Omicron S proteins. However, reactivity was not maintained to the Omicron RBD33, suggesting a preservation of Fc-dependent functional activity largely at non-RBD epitopes, albeit in a small sample size (n = 13). Additionally, prior SARS-CoV-2 infection has been shown to boost anti-S IgG following AZ34 or SV35 vaccination, but it remains unknown how this impacts antibody Fc-dependent functional activity.

Here, we investigated Fc-dependent functional activities of antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 S protein in a cohort of Brazilian adults that received the AZ or SV vaccines, and unvaccinated individuals with a mild-moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection. We determined the effect of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection on vaccine-induced antibody responses and evaluated Fc-dependent functional activity to the Delta (B.1.617.2) and Omicron BA.1 VOC S proteins compared to ancestral S.

Our results show that hybrid immunity, combined from natural exposure and vaccination, generates strong Fc-mediated antibody functions against evolving SARS-CoV-2 variants. AZ induces greater Fcγ-receptor-binding (types I, IIa, and IIIa/b) antibodies than SV or natural infection. Previously infected individuals had significantly greater vaccine-induced responses compared to those who were naïve. Fcγ-receptor-binding was highest among AZ-vaccinated individuals with a prior infection, for all receptor types, and substantial complement-fixing activity is only seen among this group. SV induces higher IgM than AZ, but this does not drive better complement-fixing activity. Some SV responses are associated with subject age, whereas AZ responses are not. Importantly, functional antibody responses are well retained against the Omicron BA.1 S protein, being best retained for Fcγ-receptor-1 binding, and are higher for AZ than SV.

Methods

Study population and ethics approval

Brazilian adults attending the health centre of Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ) with a suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection or to receive a COVID-19 vaccine were invited to participate in the present study (Table 1). The UERJ health centre provides secondary and specialised care for the Rio de Janeiro population and was a designated COVID-19 diagnostic site for personnel working in the Brazilian public health system during 202036. It was later engaged in SARS-CoV-2 vaccination for students, employees, and the general population. Serum samples were collected from participants who received two doses of AZ or SV vaccines at a median of 34 days post vaccination (n = 222). Vaccine doses were administered at days 0 and 90 for AZ and at days 0 and 28 for SV. Of the vaccinated individuals, 46.8% (n = 104) had a known prior SARS-CoV-2 infection that occurred between 1/03/2020 and 1/01/2021. Serum samples were also collected from unvaccinated participants with a PCR confirmed mild-moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection between 1/01/2020 and 31/08/2020 at a median of 67 days post infection (n = 200). Note that all infections recorded in this study occurred when the ancestral strain was the dominant variant in circulation in Brazil. Participants provided written informed consent, and ethics approval was obtained by: National Commission on Research Ethics of UERJ, Brazil (CAAE: 30135320.0.0000.5259); Alfred Human Research and Ethics Committee, Australia (approval number: 307/22).

Table 1.

Detailed cohort demographics

| AstraZeneca Naïve (AZ-N) | AstraZeneca Prior Infection (AZ-PI) | Sinovac Naïve (SV-N) | Sinovac Prior infection (SV-PI) | Natural Infection (I) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 55 | 32 | 63 | 72 | 200 | |

| Sex (female) | 38 | 24 | 48 | 58 | 143 | 0.9507* |

| Age (median years and [IQR]) | 63a [61–69] | 62a [54–64] | 50b [40–59] | 45b [33–57] | 44b [36–51] | <0.05# |

| Sample date (range) | 19/5/21–10/9/21 | 25/5/21–10/9/21 | 22/3/21–20/8/21 | 24/3/21–12/8/21 | 11/5/20–9/2/21 | |

| Days post second vaccination dose/primary infection (median and [IQR]) | 31a [29–34] | 32a [29–35] | 34a [30–35] | 35a [30–37] | 67b [55–111] | <0.0001# |

| Days post previous infection (median and [IQR]) | – | 350 [207–443] | – | 354 [244–388] | – | 0.2604† |

Data presented as median with IQR shown in brackets unless specified otherwise. Values in a row without a common superscript letter (a or b) differ significantly (P < 0.05). *=Χ22 test, #=Kruskal–Wallis test followed by a Dunn’s multiple comparisons test, and †= Mann–Whitney U test. Age; AZ-N vs AZ-PI: P > 0.9999, AZ-N vs SV-N: P = 0.000008, AZ-N vs SV-PI: P = 0.0000000007, AZ-N vs I: P = 0.000000000000001, AZ-PI vs SV-N: P = 0.0133, AZ-PI vs SV-PI: P = 0.00007, AZ-PI vs I: P = 0.0000002, SV-N vs SV-PI: P > 0.9999, SV-N vs I: P = 0.0819, SV-PI vs I: P > 0.9999. Days post vaccination dose/primary infection; AZ-N vs AZ-PI: P > 0.9999, AZ-N vs SV-N: P > 0.9999, AZ-N vs SV-PI: P = 0.1232, AZ-N vs I: P = 0.000000000000001, AZ-PI vs SV-N: P > 0.9999, AZ-PI vs SV-PI: P = 0.3892, AZ-PI vs I: P = 0.000000000000002, SV-N vs SV-PI: P > 0.9999, SV-N vs I: P = 0.000000000000001, SV-PI vs I: P = 0.000000000000002.

SARS-CoV-2 antigens

All SARS-CoV-2 antigens were commercially purchased from ACROBiosystems, USA. Antibody responses were measured to ancestral S trimer (SPN-C52H4; SPN-C52H9), biotinylated ancestral S trimer (SPN-C82E9), Delta B.1.617.2 S trimer (SPN-C52He), biotinylated Delta B.1.617.2 S trimer (SPN-C82Ec), Omicron BA.1/B.1.1.529 S trimer (SPN-C52Hz), and biotinylated Omicron BA.1/B.1.1.529 S trimer (SPN-C82Ee). Proteins were recombinantly expressed using HEK293 cells (by ACROBiosystems; Mycoplasma status unknown). Protein content and purity were validated by the manufacturer and in house using SDS-PAGE (Fig. S1).

Antibody detection by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

To detect antigen-specific antibodies (IgG, IgM, and IgA), we coated 384-well Spectra plates (PerkinElmer, USA) with ancestral, Delta, or Omicron S trimer at 0.5 µg/ml in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The plates were blocked with 0.1% casein (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in PBS (w/v) and serum samples were tested at 1/2000 (IgG), 1/800 (IgM), or 1/400 (IgA) dilution using the JANUS automated workstation (PerkinElmer) as previously validated37. Isotype-specific antibodies were detected using goat anti-human IgG (1/1000; #62-8420, Invitrogen, USA), IgM (1/2500; #AP114P, Sigma-Aldrich), or IgA (1/5000; #ab97215, Abcam, UK) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP). IgG subclasses were detected using mouse antibodies to IgG1, 2, 3, or 4 human subclasses (1/1000; #A10630, #05-3500, #05-3600, #A10651, Invitrogen) followed by goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to HRP (1/1000, #AP308P, Sigma Aldrich). The plates were then incubated with 3,3′, 5,5′ tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and shielded from light. The colour-changing reaction was stopped using 1% H2SO4 in dH2O (v/v) and optical density (OD) was immediately read at 450 nm using a Multiskan GO plate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Serum samples and all reagents were prepared using 0.1% casein in PBS (w/v) unless specified otherwise. Note that for all plate-based assays, prior to addition of any reagent or serum, plates were washed thrice with a microplate washer (Millennium Science, AUS) using 0.05% Tween in PBS (v/v) unless specified otherwise.

FcγR-binding assays

FcγR-binding assays were conducted to quantify antibody binding to FcγRI, FcγRIIa, and FcγRIII as previously described38–40. Briefly, 384-well Spectra plates were coated with ancestral, Delta, or Omicron S trimer at 0.5 µg/ml in PBS and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Plates were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS (w/v) and serum samples were tested at 1/8000 (FcγRI) or 1/200 (FcγRIIa and FcγRIII) dilution using the JANUS automated workstation. Plates were then incubated with biotinylated human FcγRI (Sino Biological, CN) at 0.125 µg/ml, FcγRIIa-H131 dimer40 at 0.2 µg/ml, or FcγRIII-V158 dimer40 at 0.1 µg/ml, followed by the addition of streptavidin conjugated HRP (#21130, Invitrogen) at 1/10,000 dilution. Plates were then incubated with TMB, followed by 1% H2SO4 in dH2O (v/v) and absorbance was immediately read at 450 nm. Serum samples and all reagents were prepared in 1% BSA in PBS (w/v) unless specified otherwise.

To confirm that FcγR-binding correlated with cellular effector functions, we evaluated the ability of serum from vaccinated individuals to activate cells expressing FcγRIIa or FcγRIII in vitro as previously described41. Serum samples were randomly selected from the upper (n = 20) and lower (n = 20) tertiles of FcγRIIa- and FcγRIII-binding responders. Briefly, A549 cells expressing the full-length ancestral SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (A549S)41 were allowed to adhere to wells of 96 well opaque plates (Corning, USA) and serum samples were added in duplicate at a dilution of 1/200 in RPMI containing 5% FCS, 2 mM glutamine, 55 µM 2-merceptoethanol, 100 units/ml Penicillin, and 100 µg/ml Streptomycin to allow for antibody opsonisation. Plates were washed thrice with RPMI media before IIA1.6 reporter cells with a NF-κB-nanoluciferase FcγRIIa H131 or NF-κB-nanoluciferase FcγRIII V158 construct were added. Following incubation, cells were lysed by the addition of Nano-Glo luciferase assay substrate at a dilution of 1/1000 in 10 mM Tris pH 7.4, containing 5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, and 0.2% Igepal CA-630 (Sigma Aldrich). The induction of nano-luciferase expression was determined by measuring the relative luminescence units (RLU) of each well for one second/well using a Clariostar Optima plate reader (BMG Labtech, USA).

Complement-fixation assay

Assays to quantify antibody binding to complement component C1q, which is required to initiate the classical component pathway, were conducted as previously described42. Briefly, 384-well Spectra plates were coated with 5 µg/ml of avidin (Jomar Life Research, AUS) in PBS and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Plates were blocked with 0.1% casein in PBS (w/v) and biotinylated S protein was added at 1 µg/ml in PBS. Serum samples were tested at 1/100 dilution using the JANUS automated workstation, followed by the addition of purified human C1q (MilliporeSigma, USA) at 10 µg/ml. Plates were incubated with rabbit anti-C1q IgG42,43 at 1/2000 dilution, followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG HRP (#1706515, Bio-Rad) at 1/2000 dilution. Plates were then incubated with TMB, followed by 1% H2SO4 in dH2O (v/v) and absorbance was immediately read at 450 nm. All serum and reagent dilutions were performed using 0.1% casein in PBS (w/v).

To confirm that C1q-fixation led to the activation of downstream complement proteins, we evaluated the ability of serum from vaccinated individuals to fix the terminal complement component C5b-C9 that forms the membrane attack complex. Serum samples were randomly selected from the upper (n = 20) and lower (n = 20) tertiles of IgG responders. Plates were prepared as above, but human serum from pre-pandemic COVID-19 naive donors was used as a source of complement at 1/10 dilution and C5b-C9-fixation was detected using rabbit anti-C5b-C9 IgG (#204903, Millipore) and goat anti-rabbit IgG HRP antibodies at 1/1000 dilution.

Statistics and reproducibility

Raw data were corrected for background reactivity using no-serum controls. Positive control samples were used to standardise for plate-to-plate variability and negative control samples from pre-pandemic Melbourne donors were used to interpret seropositivity, which was defined as the mean +2 standard deviations of the Melbourne donors (n = 28). The following non-parametric statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 and Stata. Mann–Whitney U test to compare two independent groups. Kruskal Wallis test or a Friedman test, followed by a Dunn’s multiple comparisons test which adjusts for multiple comparisons, to compare unpaired or paired data (respectively) in more than two groups. Spearman’s rank correlations to compare the relationship between antibody magnitude and functional responses. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Exact p-values for all statistical tests are stated in the figure legends and table footnotes. The interpretation of differences between groups considered the p-value, the effect size, and the overall coherency of the findings.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Fc-mediated antibody functions induced by AZ and SV vaccination in SARS-CoV-2 naïve individuals

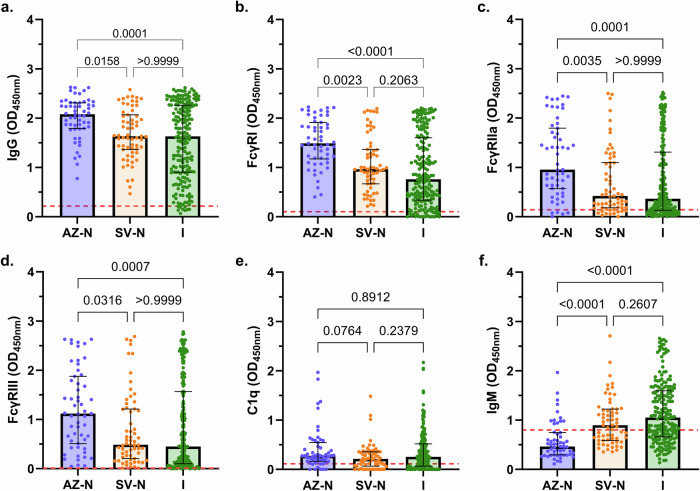

We evaluated antibodies among participants who received two doses of the AZ or SV vaccines and were naïve to SARS-CoV-2 infection (AZ-N, n = 55; SV-N, n = 63), and unvaccinated individuals with a known SARS-CoV-2 infection (I, n = 200). Serum samples collected post-vaccination (median [interquartile range (IQR)] days: AZ-N, 31 [29–34]; SV-N, 34 [30–35]) or post-infection (median [IQR] days: 67 [55–111]) were tested in immunoassays against the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 S protein (Table 1). All infections recorded in this study occurred during 2020 when the ancestral strain was the dominant variant in circulation in Brazil.

IgG magnitude to the ancestral S protein was significantly higher in participants vaccinated with AZ compared to SV (P = 0.0158; Fig. 1a). IgG magnitude was similar between SV-vaccinated individuals and unvaccinated individuals who had a prior SARS-CoV-2 infection. Both AZ and SV vaccines effectively induced antibodies able to engage FcγRI, FcγRIIa, and FcγRIII, which bind IgG and not IgA or IgM, as did antibodies from natural infection; however, the magnitude of activity varied substantially among individuals. Antibodies from AZ-vaccinated individuals had greater activity than SV-vaccinated individuals for all FcγRs (Fig. 1b–d). The difference in response between vaccine groups was somewhat more prominent for FcγR-binding activity than for IgG, which might be relevant to differences in protective efficacy between the vaccines (median OD difference for AZ and SV groups: IgG, 0.45; FcγRI, 0.53; FcγRIIa, 0.53; FcγRIII, 0.63). IgG magnitude generally correlated strongly with FcγRI-, FcγRIIa-, and FcγRIII-binding across all groups (Fig. S2).

Fig. 1. Antibody responses following AZ vaccination, SV vaccination, or SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Sera were collected from SARS-CoV-2 naïve individuals who were vaccinated with AZ (AZ-N; blue; n = 55), or SV (SV-N; orange; n = 63), and unvaccinated individuals with a known SRAS-CoV-2 infection (I; green; n = 200). Samples were tested for (a) IgG magnitude, binding to (b) FcγRI, (c) FcγRIIa, and (d) FcγRIII, (e) C1q-fixation, and (f) IgM magnitude to the SARS-CoV-2 ancestral S protein. Data are presented as optical density (OD) read at 450 nm, whereby each data point represents an individual, with columns and error bars showing median and IQR. The red dotted line indicates the seropositivity cutoff (mean +2 SD of negative controls). Data were subjected to a Kruskal Wallis test followed by a Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. (b) AZ-N vs I: P = 0.00000002, (f) AZ-N vs SV-N: P = 0.00003, AZ-N vs I: P = 0.000000000007.

To confirm that FcγR-dimer binding corresponds with cellular activation in vitro, we evaluated the ability of serum from vaccinated individuals to activate cells expressing FcγRIIa or FcγRIII using a random selection of individuals with high (n = 20) or low (n = 20) FcγR-dimer binding activity. Serum samples were used to opsonise A549 cells expressing full-length ancestral S protein, which were then co-incubated with IIA1.6 reporter cells expressing FcγRIIa or FcγRIII, and NF-κB-nanoluciferase. It is noteworthy that the measure of FcγR-dimer binding agreed strongly with the activation of cells that express FcγRIIa or FcγRIII in vitro (P < 0.00000001 for both tests; Fig. 2a, b). In further experiments evaluating samples across a range of values, correlations between FcγR binding and cellular assays were r = 0.988 (n = 10, P = 0.000006) for FcγRIIa and r = 0.879 (n = 10, P = 0.0016) for FcγRIII.

Fig. 2. Fc-dependent cellular activation and complement activation.

Serum samples from vaccinees with low (n = 20) or high (n = 20) responses were randomly selected and tested for functional activities. a FcγRIIa activation using a cell-based nano-luciferase assay against A549S cells. b FcγRIII activation using a cell-based nano-luciferase assay against A549S cells. c C5b-C9 fixation by antibodies against the S protein. For FcγR assays, serum samples were selected on the basis of FcγRIIa- and FcγRIII-dimer binding activity in plate-based assays using S protein. For complement activation assays, serum samples were selected based on their IgG reactivity to S protein. Dot plots of samples are shown with lines and error bars showing median ± IQR. Data are presented as optical density (OD) read at 450 nm or as relative luminescence units (RLU) as indicated. Data were subjected to a Mann–Whitney U test. a P = 0.0000000009, (b) P = 0.000000003, (c) P = 0.00000000002.

Antibodies can also fix serum C1q and activate the classical complement pathway, leading to enhanced neutralisation, opsonisation, and/or lysis of pathogens. To confirm that C1q-fixation leads to downstream complement activation, we evaluated serum samples from a random selection of individuals with high (n = 20) and low (n = 20) IgG magnitude, for the ability to fix C1q to S protein and activate downstream complement proteins such as the terminal C5b-C9 complex. C1q-fixation activity corresponded strongly with the activation of C5b-C9 among this subset of samples (Fig. 2c). There was a strong correlation between C1q-fixation and C5b-C9 complex formation (r = 0.9276, n = 40, P = 0.000000000000001). C1q-fixation activity among the AZ, SV, and infection groups was relatively low and comparable, despite there being significant differences in IgG magnitude between the groups (Fig. 1e). Given that IgM is a potent mediator of C1q-fixation44, we quantified IgM magnitude. Interestingly, IgM was significantly higher in those vaccinated with SV compared to AZ (P = 0.00003) (Fig. 1f), and the ratio of IgM:IgG was higher for the SV group than the AZ group (0.549 vs 0.223). Only 12 AZ-vaccinated individuals had IgM levels greater than the seropositivity cutoff, whereas the majority of SV-vaccinated individuals had reactivity above the cutoff. IgM was also significantly higher among the infection group compared to AZ vaccinees (P = 0.000000000007).

To investigate the determinants of C1q-fixation among vaccinees and infected individuals, the relative contribution of IgG in mediating C1q-fixation with and without adjusting for IgM was explored using multiple linear regression models. Among vaccinees, IgG but not IgM significantly correlated with C1q-fixation. The best model for vaccinated participants included IgG alone (coefficient, 0.475; R-squared, 0.291). In contrast, among infected individuals, IgG and IgM were significantly correlated with C1q-fixation in univariate analysis. The best model included IgG and IgM (coefficient for IgG with adjusting for IgM, 0.270; R-squared, 0.361; Table S1). This suggests that IgG is the main determinant of complement fixation activity in vaccinated individuals whereas IgM may contribute to complement fixation among infected individuals.

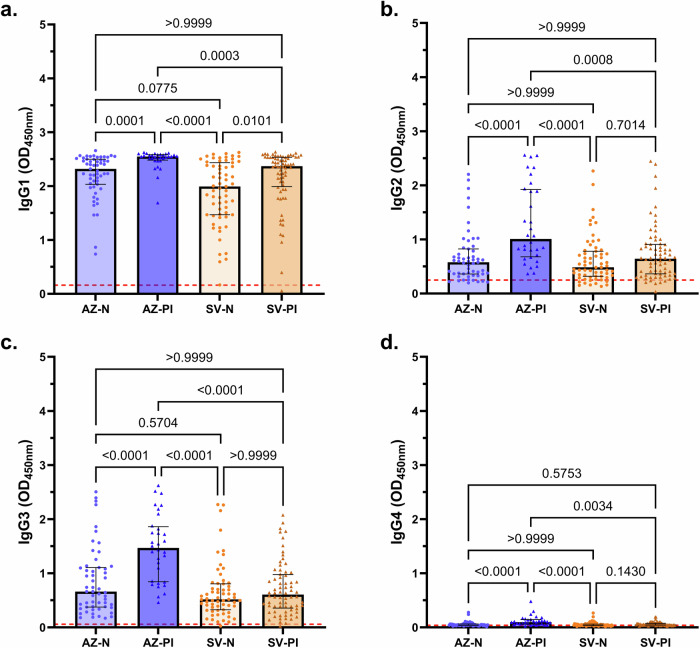

Prior SARS-CoV-2 infection boosts vaccine-induced Fc functions

Our study also included vaccinated individuals known to have a prior infection (PI) with SARS-CoV-2 (AZ-PI, n = 32; SV-PI, n = 72). Prior infection events were recorded at a similar time prior to sample collection in AZ-PI and SV-PI vaccinated individuals (median [IQR] days: AZ-PI, 350 [207–443]; SV-PI, 354 [244–388]; P = 0.2604; Table 1). Individuals vaccinated with AZ with a prior SARS-CoV-2 infection had significantly greater magnitudes of all Fc-dependent functional antibody responses (FcγR-binding and C1q-fixation), as well as IgG and IgM, than AZ-vaccinated individuals who were naïve (P < 0.001 for all tests; Fig. 3). This was similarly observed in individuals vaccinated with SV with the exception of IgM, which was comparable among previously infected and naïve vaccinees (Fig. 3). The effect of prior infection was most pronounced for C1q-fixation and FcγRIIa- and FcγRIII-dimer binding; clustering of IgG is required to get efficient engagement of these FcγRs and C1q. Of the previously infected individuals, those vaccinated with AZ had significantly greater functional antibodies (FcγR-binding and C1q-fixation) and IgG than those vaccinated with SV (P < 0.0001 for all tests; Fig. 3a, c–f). This was particularly pronounced for C1q-fixation whereby the AZ-PI group median response was more than 4 times greater than the SV-PI group (Fig. 3c). These findings demonstrate that a combination of AZ vaccination and prior SARS-CoV-2 infection leads to much greater Fc-mediated functional activities.

Fig. 3. Antibody responses of infection-naïve and previously infected vaccinees.

Serum samples were collected from infection-naïve AZ vaccinees (AZ-N; blue; n = 55), prior infection AZ vaccinees (AZ-PI, dark blue, n = 32), infection-naïve SV vaccinees (SV-N) (orange; n = 63), and prior infection SV vaccinees (SV-PI; brown; n = 72) and tested for (a) IgG and (b) IgM magnitudes, (c) C1q-fixation, and (d) FcγRI-, (e) FcγRIIa-, and (f) FcγRIII-binding to the SARS-CoV-2 ancestral S protein. Data are presented as optical density (OD) read at 450 nm. Each data point represents an individual, with columns and error bars showing median and IQR. The red dotted line indicates the seropositivity cutoff (mean +2 SD of negative controls). Data were subjected to a Kruskal Wallis test followed by a Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. a AZ-N vs AZ-PI: P = 0.000003, AZ-PI vs SV-N: P = 0.00000000000003, (b) AZ-N vs AZ-PI: P = 0.0000005, AZ-N vs SV-N: P = 0.000004, AZ-N vs SV-PI: P = 0.00006, (c) AZ-N vs AZ-PI: P = 0.00000002, AZ-PI vs SV-N: P = 0.00000000000006, AZ-PI vs SV-PI: P = 0.000002, (d) AZ-PI vs SV-N: P = 0.000000000002, AZ-PI vs SV-PI: P = 0.000009, (e) AZ-N vs AZ-PI: P = 0.000005, AZ-PI vs SV-N: P = 0.00000000000004, AZ-PI vs SV-PI: P = 0.000001, (f) AZ-N vs AZ-PI: P = 0.000006, AZ-PI vs SV-N: P = 0.000000000003, AZ-PI vs SV-PI: P = 0.00002.

The IgG subclasses induced following vaccination were evaluated in previously infected and naïve vaccinees. Overall, the dominant IgG subclass was IgG1 (Fig. 4a), which also correlated strongly with total IgG levels (r = 0.8881, P = 0.000000000000001, Spearman’s rank correlation). Previously infected AZ-vaccinated individuals had significantly greater IgG1, IgG2, and IgG3 than naïve AZ vaccinated and naïve SV vaccinated individuals (P < 0.001 for all tests; Fig. 4a–c). Higher IgG3 was the most prominent difference between AZ-PI and SV-PI groups. IgG4 levels were low across all subgroups but were significantly higher among AZ-PI versus AZ-N or SV vaccine groups (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 4. IgG subclasses of infection-naïve and previously infected vaccinees.

Serum samples were collected from infection-naïve AZ vaccinees (AZ-N; blue; n = 55), prior infection AZ vaccinees (AZ-PI, dark blue, n = 32), infection-naïve SV vaccinees (SV-N) (orange; n = 63), and prior infection SV vaccinees (SV-PI; brown; n = 72) and tested for (a) IgG1, (b) IgG2, (c) IgG3 and (d) IgG4 magnitudes to the SARS-CoV-2 ancestral S protein. Data are presented as optical density (OD) read at 450 nm. Each data point represents an individual, with columns and error bars showing median and IQR. The red dotted line indicates the seropositivity cutoff (mean +2 SD of negative controls). Data were subjected to a Kruskal Wallis test followed by a Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. a AZ-PI vs SV-N: P = 0.0000000006, (b) AZ-N vs AZ-PI: P = 0.00008, AZ-PI vs SV-N: P = 0.000004, (c) AZ-N vs AZ-PI: P = 0.00006, AZ-PI vs SV-N: P = 0.00000002, AZ-PI vs SV-PI: P = 0.0000003, (d) AZ-N vs AZ-PI: P = 0.00002, AZ-PI vs SV-N: P = 0.000001.

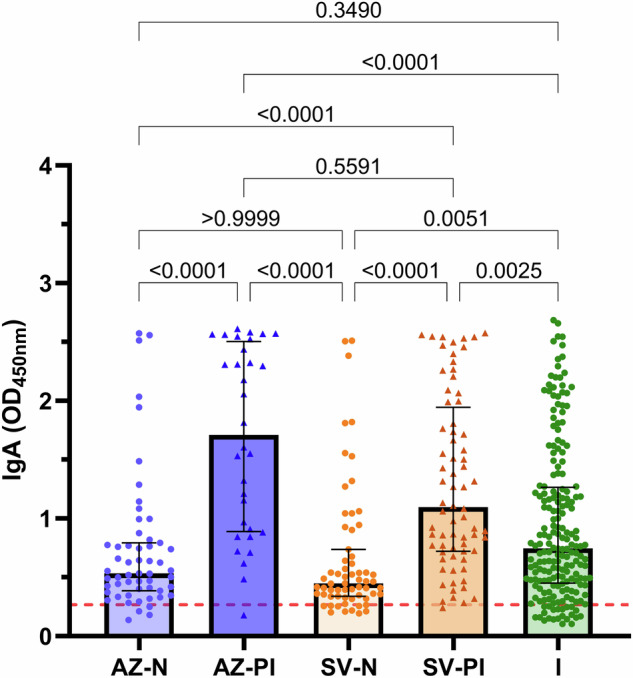

There were also notable differences in IgA magnitude between the groups of participants. Previously infected AZ and SV vaccinees had greater IgA magnitude compared to their naïve vaccinee counterparts (P < 0.000001 for all tests; Fig. 5). Interestingly, the difference between previously infected and naïve vaccinees was more striking for IgA than for IgG (average OD difference: IgG 0.43; IgA 1.13). Naturally infected individuals had lower IgA magnitude than the AZ prior infection (P = 0.00002) and SV prior infection (P = 0.0025) individuals, but greater IgA magnitude compared to the SV naïve individuals (P = 0.0051).

Fig. 5. IgA magnitude of vaccinees and infected individuals.

Sera were collected from infection-naïve AZ vaccinees (AZ-N; blue; n = 55), prior infection AZ vaccinees (AZ-PI; dark blue; n = 32), infection-naïve SV vaccinees (SV-N; orange; n = 63), prior infection SV vaccinees (SV-PI; brown; n = 72) and SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals (I; green; n = 200) and tested for IgA magnitude. Data are presented as optical density (OD) read at 450 nm. Each data point represents an individual, with columns and error bars showing median ± IQR. The red dotted line indicates the seropositivity cutoff (mean +2 SD of negative controls). Data were subjected to a Kruskal Wallis test followed by a Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. AZ-N vs AZ-PI: P = 0.0000003, AZ-N vs SV-PI: P = 0.00004, AZ-PI vs SV-N: P = 0.0000000008, AZ-PI vs I: P = 0.00002, SV-N vs SV-PI: P = 0.00000006.

Weak correlations between antibodies against SARS-Cov-2 S protein and age/sex

Most participants in this study were female (n = 311, 73.7%); with a comparable proportion of males and females in all subgroups (P = 0.9507; Table 1). There were no significant differences in antibody magnitudes and Fc-dependent functional activities between females and males (P > 0.7050 for all tests). The median age of individuals vaccinated with AZ (63 years) was older compared to SV (50 years), and compared to unvaccinated infection group (44 years) (P < 0.05 for both tests). Consistent with previous reports45,46, there was a weak correlation between age and IgG magnitude among subjects with naturally acquired antibodies in the infection group and SV-PI group (r = 0.2362 and r = 0.3453, respectively; P < 0.01 for both tests; Table S2). Further, age correlated weakly with Fc-dependent functional activities in the infection group (FcγRI, r = 0.206; FcγRIIa, r = 0.191; FcγRIII, r = 0.206; C1q, r = 0.171; P < 0.05 for all tests) and with FcγRI and C1q in the SV-PI group (r = 0.237 and r = 0.253, respectively; P < 0.05 for both tests). IgG magnitude did not correlate with age amongst the naïve AZ or SV vaccinated individuals (r = 0.014 and r = −0.050, respectively). However, IgM correlated negatively with age in the SV-N group (r = −0.355, P = 0.0044).

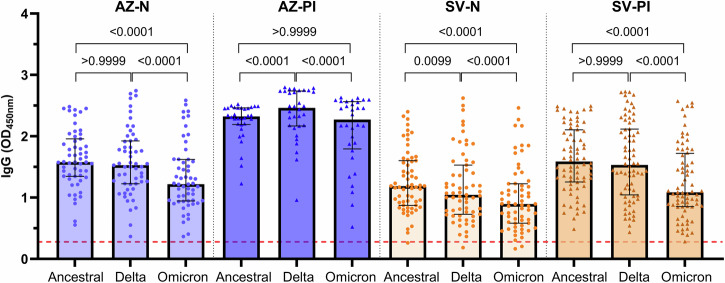

Vaccine-induced IgG to the spike protein is retained against VOCs

The emergence of VOCs, especially the Omicron variant, continue to cause negative health impacts worldwide due to their ability to evade neutralising antibodies and immunological memory raised against the ancestral strain through vaccination. We evaluated the ability of IgG from AZ or SV-vaccinated individuals to recognise and the Delta (B.1.617.2) and Omicron (B.1.1.529/BA.1) S proteins. To ensure an appropriate comparison between the ancestral, Delta, and Omicron S proteins, we confirmed the purity and integrity of all recombinant S antigens by SDS-PAGE (Fig. S1a) and validated that the coating of each variant was comparable using the published monoclonal antibody, S2H97, that targets a conserved region at the base of the RBD47 (Fig. S1b). We found robust IgG reactivity to the Delta and Omicron S proteins, as was seen for the vaccine-type ancestral S protein, across all vaccine groups (AZ-N, AZ-PI, SV-N, and SV-PI; Fig. 6). IgG magnitude was similar towards ancestral and Delta S proteins in the AZ-N and SV-PI groups, however, responses to Delta were higher in the AZ-PI group (P = 0.00006) and lower in the SV-N group (P = 0.0099). Notably, the magnitude of the IgG response was significantly lower to Omicron compared to ancestral S protein across all groups (P < 0.000000000001 for all tests) except the AZ-PI group. High responders to the ancestral S protein were also high responders to variant S proteins, correlating very strongly with Delta (r = 0.9744) and Omicron (r = 0.9306) IgG responses (P = 0.000000000000001 for both tests, Spearman’s rank correlation).

Fig. 6. Vaccine-induced IgG to the S protein of VOCs.

Sera were collected from individuals vaccinated with AZ or SV who were naïve or previously infected with SARS-CoV-2 (AZ-N, n = 55; AZ-PI, n = 32; SV-N, n = 63; SV-PI, n = 72). Samples were tested for IgG to the SARS-CoV-2 ancestral, Delta, and Omicron S proteins. Data are presented as optical density (OD) read at 450 nm. Each data point represents an individual and represents the average of two experiments, with columns and error bars showing median and IQR. The red dotted line indicates the seropositivity cutoff (mean +2 SD of negative controls). Data were subjected to a Friedman test followed by a Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. AZ-N; ancestral vs Omicron: P = 0.0000000000003, Delta vs Omicron: P = 0.0000000001, AZ-PI; ancestral vs Delta: P = 0.00006, Delta vs Omicron: P = 0.0000009, SV-N; ancestral vs Omicron: P = 0.000000000000001, Delta vs Omicron: P = 0.00000001, SV-PI; ancestral vs Omicron: P = 0.000000000000007, Delta vs Omicron: P = 0.00000000000001.

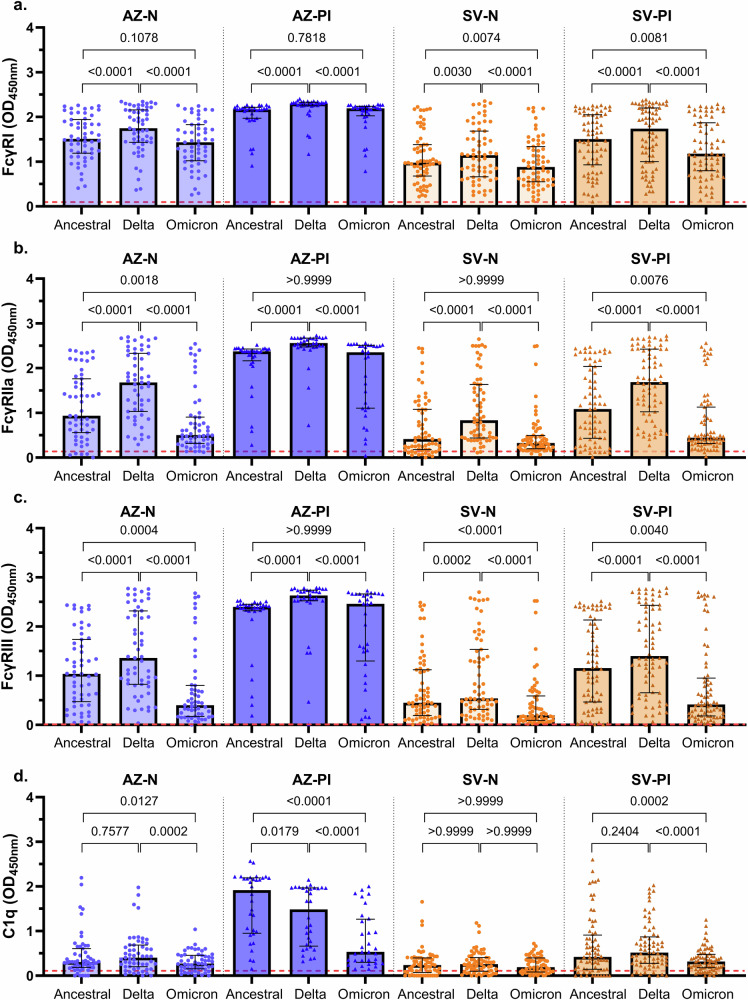

Fc-dependent functional antibody activities are differentially retained against VOCs

All antibody FcγR-binding responses were well retained when tested against Delta, with reactivity being comparable or higher than reactivity to ancestral S protein across all vaccine groups (Fig. 7a–c). Overall, binding of FcγRs (I, IIa, III) by IgG was lower for Omicron compared to ancestral S protein for the AZ-N, SV-N, and SV-PI vaccine groups, whereas there were no differences activity to Omicron versus ancestral in the AZ-PI group. All vaccine groups displayed robust FcγRI-binding activity when tested against Omicron S, with no significant differences between ancestral and Omicron S binding in the AZ-N and AZ-PI groups, but responses were marginally lower compared to ancestral S in the SV-N and SV-PI groups, with a median OD difference of 0.10 and 0.33, respectively (P < 0.01 for both tests; Fig. 7a). Compared to FcγRIIa-dimer binding to ancestral S, reactivity against Omicron S was lower in the AZ-N group (0.43 OD; P = 0.0018) and the SV-PI group (0.63 OD; P = 0.0040) (Fig. 7b). Loss of reactivity against Omicron S was somewhat more pronounced for FcγRIII-dimer binding in the AZ-N group (0.64 OD), in the SV-N group (0.25 OD), and the SV-PI group (0.74 OD) (P < 0.01 for all tests; Fig. 7c). Despite this general trend of decreased FcγRIIa/FcγRIII-dimer reactivity to Omicron S across the vaccine groups, several individuals within each group had strong reactivity across all S proteins.

Fig. 7. Fc functional responses against VOCs.

Sera were collected from infection-naïve AZ vaccinees (AZ-N; blue; n = 55), prior infection AZ vaccinees (AZ-PI; dark blue; n = 32), infection-naïve SV vaccinees (SV-N; orange; n = 63), and prior infection SV vaccinees (SV-PI; brown; n = 72) and tested for (a) FcγRI, (b) FcγRIIa, and (c) FcγRIII-binding, and (d) C1q-fxation to the SARS-CoV-2 ancestral, Delta, and Omicron S proteins. Data are presented as optical density (OD) read at 450 nm. Each data point represents an individual, with columns and error bars showing median ± IQR. The red dotted line indicates the seropositivity cutoff (mean +2 SD of negative controls). Data were subjected to a Friedman test followed by a Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. a AZ-N; ancestral vs Delta: P = 0.00004, Delta vs Omicron: P = 0.0000000003, AZ-PI; ancestral vs Delta: P = 0.0000000006, Delta vs Omicron: P = 0.0000005, SV-N; Delta vs Omicron: P = 0.0000000008, SV-PI; ancestral vs Delta: P = 0.00006, Delta vs Omicron: P = 0.000000000001, (b) AZ-N; ancestral vs Delta: P = 0.000000006, Delta vs Omicron: P = 0.000000000000001, AZ-PI; ancestral vs Delta: P = 0.00000001, Delta vs Omicron: P = 0.000000003, SV-N; ancestral vs Delta: P = 0.000000000002, Delta vs Omicron: P = 0.00000000000003, SV-PI; ancestral vs Delta: P = 0.0000000000009, Delta vs Omicron: P = 0.000000000000001, (c) AZ-N; ancestral vs Delta: P = 0.0000005, Delta vs Omicron: P = 0.000000000000001, AZ-PI; ancestral vs Delta: P = 0.00000001, Delta vs Omicron: P = 0.0000002, SV-N; ancestral vs Omicron: P = 0.000005, Delta vs Omicron: P = 0.000000000000001, SV-PI; ancestral vs Delta: P = 0.000000002, Delta vs Omicron: P = 0.000000000000001, (d) AZ-PI; ancestral vs Omicron: P = 0.000000000008, Delta vs Omicron: P = 0.00006, SV-PI; Delta vs Omicron: P = 0.00000003.

Substantial C1q-fixation activity to ancestral S was only observed among the AZ-PI vaccinees. Among this group, median C1q-fixation was 3.6 times lower to Omicron S compared to ancestral S (P = 0.000000000008; Fig. 7d). C1q-fixation was also lower to Delta compared to ancestral S protein in the AZ-PI group. C1q-fixation across the AZ-N, SV-N, and SV-PI groups was generally low to ancestral, Delta, and Omicron S proteins. Some individuals within each group had high reactivity to ancestral S, which was lost when tested against Omicron S, contributing to C1q-fixation being significantly higher to ancestral S in the AZ-N, AZ-PI, and SV-PI groups (P < 0.05 for all comparisons).

Discussion

This study provides important new knowledge on Fc-mediated functional activities induced by different COVID-19 vaccines, with a focus on AZ and SV vaccines that have been administered to a large proportion of the world’s population. Fc-mediated antibody mechanisms contribute to protective immunity24–27 but have not been extensively studied in the context of these vaccines, or differences in the induction of these responses between responders, and determinants affecting the generation of these responses are not well defined. Several Omicron subvariants are currently in circulation, with substantial RBD mutations compared to ancestral RBD, and a marked reduction in neutralising activity of AZ and SV-induced antibodies has been observed12–14. Despite this, these vaccines retain significant efficacy against hospitalisation or death caused by Omicron variants48–51, suggesting the importance of immune responses beyond neutralising antibodies, including non-neutralising antibodies or T-cells that can target more conserved epitopes.

Here, we found important differences in the induction of Fc-mediated immunity between AZ and SV vaccination. Vaccination with AZ consistently induced a greater magnitude of antibodies with Fc-mediated functional activities than the SV vaccine, including engaging multiple FcγRs (I, IIa, and IIIa/b) and complement fixation. AZ induced higher IgA responses, whereas SV induced greater IgM which is potent in complement fixation. Despite this, SV vaccination yielded lower complement fixation activity than AZ and analysis indicated that complement fixation was driven largely by vaccine-induced IgG with little contribution from IgM. Vaccine responses were substantially greater in individuals previously infected with SARS-CoV-2 than in those who were SARS-CoV-2 naïve. Encouragingly, vaccine-induced antibodies retained Fc-mediated functional activities against VOCs, including the Omicron S protein. This was especially seen among those vaccinees who had prior infection (which was not with the Omicron VOC), indicating the importance of hybrid immunity (combination of natural infection and vaccination) in generating broad and more potent immunity. The retention of functional antibody activity was strong for binding to FcγRI (which is widely expressed on monocytes, macrophages, and activated neutrophils), whereas FcγRIIa and IIIa/b and complement fixation were more substantially reduced, especially among the SV vaccinees.

The AZ vaccine induced greater IgG and FcγR-binding responses than the SV vaccine. This difference in response magnitude was more prominent for FcγR-binding activity than for IgG which was observed in both the naïve and previously infected sub-groups. This likely reflects that an antibody density threshold is required to mediate multivalent binding of the low-affinity receptors, FcγRIIa and FcγRIII, when formatted as dimers40. IgM was only moderately induced but was significantly higher following vaccination with SV compared to AZ. Previous studies have similarly reported a low seroprevalence of anti-S IgM52–54. It was unclear why IgM responses were higher following SV vaccination, but it may relate to the nature of antigen presentation following vaccination (AZ uses a viral vector to deliver S antigen whereas SV is a whole inactivated SARS-CoV-2 virus) or the time interval between primary vaccine doses (1 month for SV and 3 months for AZ). These factors may also explain, in part, the higher IgG response induced by the AZ vaccine compared to SV. Robust IgM magnitudes were observed among unvaccinated individuals who were recently naturally infected with SARS-CoV-2. IgG and IgM strongly fix complement component C1q, and our analyses suggest that IgM played a more substantial role in mediating C1q-fixation amongst naturally infected individuals. Conversely, IgG was the main determinant in vaccinated individuals, as previously shown in vaccines with low IgM55. However, C1q-fixation responses were modest in our study, which influenced the strength and significance of these associations. Therefore, larger cohorts should be evaluated to further understand the relative contributions of IgG and IgM in mediating C1q-fixation to SARS-CoV-2 antigens. Our study focused on antibody-mediated complement fixation and activation as part of the adaptive immune response, considering its potential role in contributing to immunity to SARS-CoV-2. However, complement can also be activated through innate pathways and excess complement activation may conversely contribute to pathogenesis of severe disease29,30.

We observed highly variable magnitudes of Fc-mediated functional response types irrespective of the vaccine given or prior infection status to SARS-CoV-2. Host factors may contribute to the observed variability, such as sex and age. It is noteworthy that while the majority of participants in this study were female, sex did not impact on vaccine responses as previously reported56–58. SV-induced responses showed some age associations, with increased IgG and decreased IgM with increasing age, whereas there were no associations for AZ, consistent with some previous reports amongst adults59,60. Participants in this study were adults aged between 22 and 84 years. It is possible that the induction of Fc-dependent antibody responses may differ in children/adolescences and older individuals. Differences in relative IgG and IgM levels is likely to be a contributing factor explaining the lower FcγR binding activity of antibodies from SV-vaccinated subjects compared to AZ vaccinated. IgG levels were higher in the AZ-N group than SV-N, whereas IgM was higher in SV-N than AZ-N. This is notable because IgM does not engage FcγRs and higher levels of antigen-specific IgM binding may inhibit FcγR binding. IgG1 and IgG3 are the most potent IgG subclasses for engaging FcRs. The IgG subclass profiles of AZ and SV vaccinated individuals were not substantially different among naïve vaccinees, suggesting that subclass profiles were not a major factor explaining differences in FcγR binding antibodies between these groups. Among vaccinees who had been previously infected, there was significantly higher IgG1 and IgG3 among AZ versus SV vaccinees, which may further explain the higher FcγR binding activity of the AZ-PI group. Antibodies mediating Fc-functional activity have been reported to target all subregions of the S protein, including the receptor-binding domain, N-terminal region, and the S1 and S2 subregions58,61–63. The specificity of antibodies to different regions may also contribute to differences in Fc-functional activity between AZ and SV-induced antibodies. Vaccination with AZ can also generate antibodies to the viral vector (ChAdOx)31, but this is unlikely to influence the quantification of antibodies specific to the S protein in this study. Future studies to further investigate the determinants of Fc-mediated functional activities of antibodies induced by the AZ and SV vaccines including an analysis of specific epitopes targeted, would be valuable and may help inform refinement in vaccine strategies, including optimising the generation of antibodies with potent Fc-mediated functional activity in addition to neutralizing activity.

AZ, SV, and other widely used vaccines are based on the ancestral variant of SARS-CoV-2, so it is crucial to evaluate the functional abilities of vaccine-induced antibodies against emerging VOCs. The Delta VOC caused a large global burden of COVID-19 during 2021 but is no longer prominent. The Omicron VOC and subvariants/sublineages were responsible for the most recent epidemics, accounting for over 98% of analysed sequences worldwide since February 202264. Loss of neutralising antibodies to the Omicron RBD have been widely reported, however, the maintenance of real-world vaccine efficacy suggests the importance of other adaptive immune factors (antibody and/or T-cell mediated) other than neutralising antibody functions in mediating protection from severe disease or death. In our study, FcγRI-binding was largely retained against Omicron S protein compared to ancestral S protein, as were Fc functional responses to Delta S protein. This was likely due to vaccine-induced antibodies recognising a broad range of conserved and/or non-neutralising epitopes outside of the RBD33,61,65. The retention of FcγRI binding activity by vaccine antibodies to the Omicron variant suggests that this may be one factor contributing to protective immunity against Omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2.

Among the AZ-naïve and SV-previously-infected/naïve sub-groups, FcγRIIa- and FcγRIII-dimer binding activity by antibodies to Omicron S protein was substantial, albeit lower compared to that of ancestral S protein. FcγRIIa/FcγRIII are low-affinity receptors that require immune complex formation, whereas FcγRI is a high-affinity receptor that binds monomeric IgG. This partial loss of FcγRIIa- and FcγRIIa-dimer binding to Omicron, but not FcyRI-binding, likely relates to the multivalent binding of the dimeric low-affinity receptors. The loss of epitope recognition of Omicron S, particularly in the RBD, may decrease the density of IgG and is likely to diminish the amount of antibody needed for FcγRIIa/RIII-dimer binding. ADCC activity by NK cells is mediated through IgG interactions with FcRIIIa and is thought to play a contributing role in immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Therefore, the reduced FcγRIII binding activity of antibodies with the Omicron variant is likely to result in reduced ADCC activity. Notably, all FcγR-binding activities of antibodies against Delta and Omicron S proteins were retained among previously infected AZ vaccinees. This was also the only sub-group with strong complement fixation activity, although this was significantly lower against Omicron. These observations indicate that a mixture of natural infection and vaccination generated broad Fc-mediated antibody functional activities against VOCs and may partly explain the retention of real-world AZ vaccine efficacy against Omicron. A further consideration is that vaccine strategies are evolving over time, including the recent implementation in some countries of bivalent vaccines that include Omicron variants, and co-administration of SARS-CoV-2 and influenza vaccines in some groups.

In conclusion, this study provides new insights on antibody Fc-mediated functional activities induced by COVID-19 vaccines, revealing differences between vaccine types, the influence of prior infection on Fc-dependent functional responses, and the retention of activity against VOCs. A greater understanding of the induction of Fc-mediated immunity in human populations is of great importance and relevance in the face of emerging VOCs and global pandemics. Overall, AZ was more immunogenic and induced greater Fc-mediated functional activity compared to SV, although both vaccines induced variable responses in this cohort. Notably, individuals who had received the AZ vaccine after prior SARS-CoV-2 infection exhibited the most robust Fc-mediated activity. This finding underscores the boosting effect of vaccination on pre-existing, naturally acquired immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Importantly, Fc-mediated activity against the Omicron variant was relatively well retained, especially for FcγRI activity, and particularly among AZ vaccinees with prior infection, potentially contributing to the efficacy of the AZ vaccine against Omicron VOCs. Additionally, differences between the AZ and SV vaccines were more pronounced for FcγR-binding activity and complement fixation than IgG reactivity. These findings suggest that hybrid immunity, through natural infection and vaccination, would provide better population immunity. Future research should further explore the determinants of optimal antibody responses to inform vaccine development and implementation. Overall, these insights contribute to our understanding of vaccine-induced immunity and its effectiveness against evolving variants, relevant to the prevention and amelioration of SARS-CoV-2 globally.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We thank all study participants and staff of the UERJ health centre, Brazil. This work was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (Investigator Grant to JGB) and Burnet Institute. The Burnet Institute received funding from the Independent Research Institutes Infrastructure Support Scheme of the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, and the Operational Infrastructure Scheme of the Victorian State Government, Australia. Funding agencies had no role in the decision to publish this work. Burnet Institute is located on the traditional land of the Boonwurrung people of the Kulin nations.

Author contributions

A.H. performed all experiments (cell activation assays were co-conducted with B.W.) and data analysis. A.H., L.K., J.B., J.N., I.B., H.D., C.V., and L.C.P. were involved in study design and sample allocation. L.K., H.O., and J.B. provided supervision. W.S.L. supplied the A549S cells and P.P. supplied the mAb used in this study. A.H., L.K., and J.B. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Siriruk Changrob, Parawee Chevaisrakul and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [Peer reviewer reports are available.]

Data availability

Data used to generate all figures is provided as a supplementary data file. Clinical data are available on reasonable request from corresponding author, but release of such data will be dependent on any ethical or regulatory clearance as required.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s43856-024-00686-6.

References

- 1.Ritchie, H. et al. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus (2022).

- 2.Al Jazeera and News Agencies. Brazil approves two COVID vaccines for emergency use. Al Jazeera (2021).

- 3.Brazil Ministry of Health. Covid-19 Vaccine Delivery Forecast - 22-06-2022. Ministry of Health Brazilhttps://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/coronavirus/entregas-de-vacinas-covid-19/projentregasvacinascovid19_30marco2022_16h08.pdf/view (2022).

- 4.Mallapaty, S. China’s COVID vaccines have been crucial — now immunity is waning. Nature598, 398–399 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organisation. Africa - COVID-19 Vaccination dashboard. https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiOTI0ZDlhZWEtMjUxMC00ZDhhLWFjOTYtYjZlMGYzOWI4NGIwIiwidCI6ImY2MTBjMGI3LWJkMjQtNGIzOS04MTBiLTNkYzI4MGFmYjU5MCIsImMiOjh9 (2022).

- 6.Cerqueira-Silva, T. et al. Influence of age on the effectiveness and duration of protection of Vaxzevria and CoronaVac vaccines: a population-based study. Lancet Reg. Health Am.6, 100154 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Earle, K. A. et al. Evidence for antibody as a protective correlate for COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccine39, 4423–4428 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seow, J. et al. Longitudinal observation and decline of neutralizing antibody responses in the three months following SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans. Nat. Microbiol.5, 1598–1607 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Beltran, W. F. et al. COVID-19-neutralizing antibodies predict disease severity and survival. Cell184, 476–488.e11 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ge, J. et al. Antibody neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 through ACE2 receptor mimicry. Nat. Commun.12, 250 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verderese, J. P. et al. Neutralizing monoclonal antibody treatment reduces hospitalization for mild and moderate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a real-world experience. Clin. Infect. Dis.74, 1063–1069 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Planas, D. et al. Considerable escape of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron to antibody neutralization. Nature602, 671–675 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu, L. et al. Boosting of serum neutralizing activity against the Omicron variant among recovered COVID-19 patients by BNT162b2 and CoronaVac vaccines. eBioMedicine79, 103986 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yin, Y. et al. Antibody efficacy of inactivated vaccine boosters (CoronaVac) against Omicron variant from a 15-month follow-up study. J. Infect.85, e119–e121 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilhelm, A. et al. Limited neutralisation of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants BA.1 and BA.2 by convalescent and vaccine serum and monoclonal antibodies. eBioMedicine82, 104158 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiLillo, D. J., Palese, P., Wilson, P. C. & Ravetch, J. V. Broadly neutralizing anti-influenza antibodies require Fc receptor engagement for in vivo protection. J. Clin. Investig.126, 605–610 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bournazos, S. et al. Broadly neutralizing Anti-HIV-1 antibodies require Fc effector functions for in vivo activity. Cell158, 1243–1253 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yaffe, Z. A. et al. Improved HIV-positive infant survival is correlated with high levels of HIV-specific ADCC activity in multiple cohorts. Cell Rep. Med.2, 100254 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gunn, B. M. et al. A role for Fc function in therapeutic monoclonal antibody-mediated protection against Ebola virus. Cell Host Microbe24, 221–233.e5 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richardson, S. I. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Beta and Delta variants trigger Fc effector function with increased cross-reactivity. Cell Rep. Med.3, 100510 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Erp, E. A., Van Kampen, M. R., Van Kasteren, P. B. & De Wit, J. Viral infection of human natural killer cells. Viruses11, 1–13 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tay, M. Z., Wiehe, K. & Pollara, J. Antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis in antiviral immune responses. Front. Immunol.10, 332 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosales, C. Fcγ receptor heterogeneity in leukocyte functional responses. Front. Immunol.8, 280 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan, C. E. Z. et al. The Fc-mediated effector functions of a potent SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody, SC31, isolated from an early convalescent COVID-19 patient, are essential for the optimal therapeutic efficacy of the antibody. PLoS ONE16, 1–23 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winkler, E. S. et al. Human neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 require intact Fc effector functions for optimal therapeutic protection. Cell184, 1804–1820.e16 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mackin, S. R. et al. Fc-γR-dependent antibody effector functions are required for vaccine-mediated protection against antigen-shifted variants of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol.8, 569–580 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zohar, T. et al. Compromised humoral functional evolution tracks with SARS-CoV-2 mortality. Cell183, 1508–1519.e12 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurtovic, L. et al. Complement in malaria immunity and vaccines. Immunol. Rev.293, 38–56 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cyprian, F. S. et al. Complement C5a and clinical markers as predictors of COVID-19 disease severity and mortality in a multi-ethnic population. Front. Immunol.12, 1–16 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sinkovits, G. et al. Complement overactivation and consumption predicts in-hospital mortality in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Front. Immunol.12, 663187 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barrett, J. R. et al. Phase 1/2 trial of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 with a booster dose induces multifunctional antibody responses. Nat. Med.27, 279–288 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang, L. et al. Coronavac inactivated vaccine triggers durable, cross-reactive Fc-mediated phagocytosis activities. Emerg. Microbes Infect.12, 2225640 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bartsch, Y. C. et al. Omicron variant Spike-specific antibody binding and Fc activity are preserved in recipients of mRNA or inactivated COVID-19 vaccines. Sci. Transl. Med.14, eabn9243 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robertson, L. J. et al. IgG antibody production and persistence to 6 months following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: a Northern Ireland observational study. Vaccine40, 2535–2539 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dinc, H. O. et al. Inactive SARS-CoV-2 vaccine generates high antibody responses in healthcare workers with and without prior infection. Vaccine40, 52–58 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Porto, L. C. et al. Clinical and laboratory characteristics in outpatient diagnosis of COVID-19 in healthcare professionals in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J. Clin. Pathol.75, 185–192 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fowkes, F. J. I. et al. New insights into acquisition, boosting, and longevity of immunity to malaria in pregnant women. J. Infect. Dis.206, 1612–1621 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feng, G. et al. Induction, decay, and determinants of functional antibodies following vaccination with the RTS,S malaria vaccine in young children. BMC Med.20, 289 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feng, G. et al. Mechanisms and targets of Fcγ-receptor mediated immunity to malaria sporozoites. Nat. Commun.12, 1742 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wines, B. D. et al. Dimeric FcγR ectodomains as probes of the Fc receptor function of anti-influenza virus IgG. J. Immunol.197, 1507–1516 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee, W. S. et al. Decay of Fc-dependent antibody functions after mild to moderate COVID-19. Cell Rep. Med.2, 100296 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kurtovic, L. et al. Induction and decay of functional complement-fixing antibodies by the RTS,S malaria vaccine in children, and a negative impact of malaria exposure. BMC Med.17, 45 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurtovic, L. et al. Human antibodies activate complement against Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites, and are associated with protection against malaria in children. BMC Med.16, 61 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cooper, N. R., Nemerow, G. R. & Mayes, J. T. Methods to detect and quantitate complement activation. Springe. Semin. Immunopathol.6, 195–212 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhai, B. et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibody response is associated with age and body mass index in convalescent outpatients. J. Immunol.208, 1711–1718 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ozgocer, T. et al. Analysis of long‐term antibody response in COVID‐19 patients by symptoms grade, gender, age, BMI, and medication. J. Med. Virol.94, 1412–1418 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Starr, T. N. et al. SARS-CoV-2 RBD antibodies that maximize breadth and resistance to escape. Nature597, 97–102 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Katikireddi, S. V. et al. Two-dose ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine protection against COVID-19 hospital admissions and deaths over time: a retrospective, population-based cohort study in Scotland and Brazil. Lancet399, 25–35 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ranzani, O. T. et al. Effectiveness of an inactivated Covid-19 vaccine with homologous and heterologous boosters against Omicron in Brazil. Nat. Commun.13, 5536 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wei, Y. et al. Estimation of vaccine effectiveness of CoronaVac and BNT162b2 against severe outcomes over time among patients with SARS-CoV-2 omicron. JAMA Netw. Open6, e2254777 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stowe, J., Andrews, N., Kirsebom, F., Ramsay, M. & Bernal, J. L. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against Omicron and Delta hospitalisation, a test negative case-control study. Nat. Commun.13, 5736 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ruggiero, A. et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination elicits unconventional IgM specific responses in naïve and previously COVID-19-infected individuals. eBioMedicine77, 103888 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu, Q.-Y. et al. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM secondary response was suppressed by preexisting immunity in vaccinees: a prospective, longitudinal cohort study over 456 days. Vaccines11, 188 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang, H. et al. Evaluation of antibody kinetics and durability in healthy individuals vaccinated with inactivated COVID-19 vaccine (CoronaVac): a cross-sectional and cohort study in Zhejiang, China. eLife12, e84056 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lamerton, R. E. et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike- and nucleoprotein-specific antibodies induced after vaccination or infection promote classical complement activation. Front. Immunol.13, 838780 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ewer, K. J. et al. T cell and antibody responses induced by a single dose of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) vaccine in a phase 1/2 clinical trial. Nat. Med.27, 270–278 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cao, Y. et al. Humoral immunogenicity and reactogenicity of CoronaVac or ZF2001 booster after two doses of inactivated vaccine. Cell Res.32, 107–109 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaplonek, P. et al. ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) vaccine-induced Fc receptor binding tracks with differential susceptibility to COVID-19. Nat. Immunol.24, 1161–1172 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adjobimey, T. et al. Comparison of IgA, IgG, and neutralizing antibody responses following immunization With Moderna, BioNTech, AstraZeneca, Sputnik-V, Johnson and Johnson, and Sinopharm’s COVID-19 vaccines. Front. Immunol.13, 917905 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fonseca, M. H. G., de Souza, T., de, F. G., de Carvalho Araújo, F. M. & de Andrade, L. O. M. Dynamics of antibody response to CoronaVac vaccine. J. Med. Virol.94, 2139–2148 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kaplonek, P. et al. mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccines elicit antibodies with differences in Fc-mediated effector functions. Sci. Transl. Med.14, eabm2311 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bowen, J. E. et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike conformation determines plasma neutralizing activity elicited by a wide panel of human vaccines. Sci. Immunol.7, eadf1421 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mok, C. K. P. et al. Comparison of the immunogenicity of BNT162b2 and CoronaVac COVID-19 vaccines in Hong Kong. Respirology27, 301–310 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Our World in Data. Share of SARS-CoV-2 sequences that are the omicron variant. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/covid-cases-omicron?time=2022-02-28 (2023).

- 65.Alter, G. et al. Immunogenicity of Ad26.COV2.S vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 variants in humans. Nature596, 268–272 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

Data used to generate all figures is provided as a supplementary data file. Clinical data are available on reasonable request from corresponding author, but release of such data will be dependent on any ethical or regulatory clearance as required.