Abstract

CD8+ T cell spatial distribution in the context of tumor microenvironment (TME) dictates the immunophenotypes of tumors, comprised of immune-infiltrated, immune-excluded and immune-desert, discriminating “hot” from “cold” tumors. The infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells is associated with favorable therapeutic response. Hitherto, the immunophenotypes of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) have not yet been comprehensively delineated. Herein, we comprehensively characterized the immunophenotypes of ESCC and identified a subset of ESCC, which was defined as cold tumor and characterized with CD8+ T cell-desert TME. However, the mechanism underlying the defect of CD8+ T cells in TME is still pending. Herein, we uncovered that tumor cell-intrinsic EZH2 with high expression was associated with the immunophenotype of immune-desert tumors. Targeted tumor cell-intrinsic EZH2 rewired the transcriptional activation of CXCL9 mediated by NF-κB and concomitantly reinvigorated DC maturation differentiation via inducing the reduction of VEGFC secretion, thereby enhancing the infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells into TME and inhibiting tumor immune evasion. Our findings identify EZH2 as a potential therapeutic target and point to avenues for targeted therapy applied to patients with ESCC characterized by CD8+ T cell-desert tumors.

Subject terms: Cancer microenvironment, Tumour immunology

Tumor-intrinsic EZH2 inhibits the production of CXCL9 and the differentiation of mature dendritic cells, leading to the dearth of CD8+ T cells in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Introduction

Accumulating evidence indicates that CD8+ T cell spatial distribution in tumor microenvironment (TME) dictates which immunophenotype a tumor is classified into, since three immune phenotypes, comprised of immune-infiltrated, immune-excluded and immune-desert, are available1. In immune-infiltrated tumors, which is so-called hot tumors, the filtrated CD8+ T cells undertake anti-tumor immunity, restraining tumor immune evasion, and associate with better clinical outcome and response to therapy 2–12. In contrast, immune-excluded or -desert tumors are defined as cold tumors. CD8+ T cells exhibit ineffectual anti-tumor immunity due to only peritumoral distribution, but not of intratumoral distribution, of CD8+ T cells in immune-excluded tumors, and even there is lack of CD8+ T cells in tumor islets and periphery in immune-desert tumors, thus ensuing tumor immune evasion and therapeutic resistance. Accordingly, patients with cold tumors harbor inferior clinical outcome. Therefore, reversing cold tumors into hot tumors by enhancing cytotoxic CD8+ T cells into tumor islets is the prerequisite for unleashing CD8+ T cell anti-tumor immunity and further ameliorating clinical outcome for patients with cold tumors.

ESCC, accounting for 90% of esophageal carcinoma (EC) in Asians, harbors high incidence and mortality rates. In China, appropriate 320, 000 people are diagnosed as ESCC and appropriate 300, 000 patients die of ESCC per year13. A large fraction of patients with ESCC have achieved unmet benefits from the long-term prognosis, despite the improvement in cancer treatment regimen, including surgery, chemoradiotherapy, targeted therapy14. Additionally, the desirable immunotherapy benefits only a small fraction of patients with ESCC15. Emerging data insinuates that the infiltration of CD8+ T cells correlate favorably with the efficacy of chemoradiotherapy4–9, targeted therapy10,11 and immunotherapy12. Therefore, the promising strategy for improvement of therapeutic efficacy is that turning “cold” into “hot” tumors by recruiting cytotoxic CD8+ T cells trafficking to tumor islets16. Nevertheless, hitherto, for ESCC, the delineation for the immune phenotypes depending on CD8+ T cell spatial distribution in the context of TME to discriminate “cold” from “hot” tumors, has not yet been available. Previously published data showed that CD8+ T cells spatially distributed in invasive margin or peritumoral stroma, indicative of the immune-excluded immunophenotype for ESCC available17,18. Indeed, we found that the immune-desert immunophenotype for ESCC was also available, accounting for 15.60% of total samples, other than infiltrated- and immune-excluded immunophenotypes (Supplementary Fig. S1). Therefore, enhancing the infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells into tumor islets may be an optimal modality for patients with ESCC characterized with immune-desert tumors to improve clinical outcome. However, how to recruit CD8+ T cells and the mechanism underlying immune-desert tumors remains enigmatic and elusive.

Increasing evidence has documented that tumor cell-intrinsic epigenetic modification mediated by chromatin regulators is the determinant for the infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells9,19,20 and epigenetic therapy can recruit T-cell trafficking to tumors through upregulating the expression and release of multiple chemokines including CXCL9, CXCL10 and CCL59,21,22. Therefore, to identify chromatin regulators crucial in development for ESCC with the immune-desert phenotype merits exploration. In the present study, we identified EZH2 derived from tumor cells as the determinant impeding the trafficking of CD8+ T cells to immune-desert tumors through inhibiting transcription of CXCL9, a chemokine for recruiting CD8+ T cells, and activating transcription of VEGFC restraining dendritic cell (DC) maturation. Our data unveils that targeted EZH2 reverses cold tumor with the immune-desert phenotype into hot tumor with the infiltrated phenotype through recruiting cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and thereby eliciting tumor regression, indicating that EZH2 is a potential therapeutic target for patients with the immune-desert phenotype.

Results

CD8+ T cells exhibit distinct spatial distribution in ESCC

To interrogate whether the aforementioned three immune phenotypes in other types of cancers extrapolates to ESCC, CD8+ T cell spatial distribution in total 109 cases of ESCC samples dissected from treatment-naïve patients was assessed by using immunohistology chemistry staining (IHC) for CD8A. As seeable (Supplementary Fig. S1A and B), CD8+ T cell spatial distribution in 109 cases of ESCC samples was primarily characterized with the infiltration of tumor beds, the invasive margins and CD8+ T cell-desert in TME. Accordingly, the immunophenotypes for ESCC can be classified into infiltrated (n = 25, accounting for 22.94%), immune-excluded (n = 67, accounting for 61.46%) and immune-desert tumors (n = 17, accounting for 15.60%). Surprisingly, in these 109 ESCC samples with the defined immunophenotypes, the proportion of cold tumors comprised of immune-excluded (n = 67) and immune-desert tumors (n = 17) predominates, accounting for 77.06%.

Subsequently, the relationship between each of immunophenotypes with clinicopathological features in ESCC was further exploited by using Chi-square test. The results manifested that tumor size with the immune-desert phenotype was more than that of the infiltrated phenotype as well as the immune-excluded phenotype, whereas there was no distinction between the immune-excluded and the infiltrated phenotype (Supplementary Table S1). Additionally, no correlation for the individual immunophenotype with clinicopathological features, such as age, gender, TNM staging and lymph node metastasis, was observed.

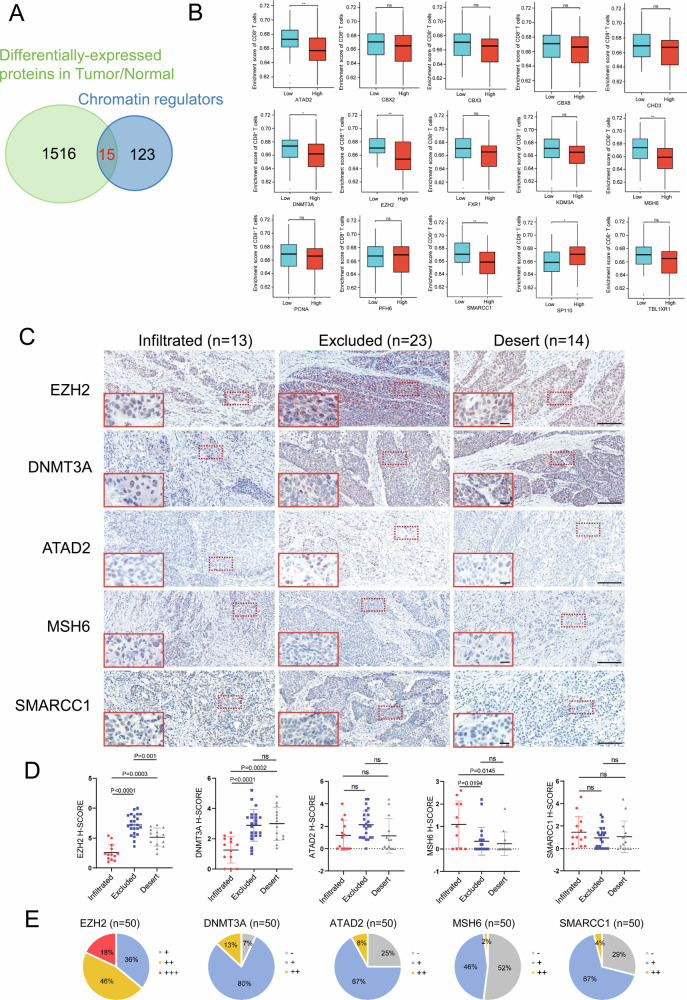

Chromatin regulator EZH2 and DNMT3A are up-regulated in ESCC with the immune-desert phenotype

Given that epigenetic modification mediated by chromatin regulators intertwines with CD8+ T cell recruitment and thereby dictates the formation of cold tumors or not, we seek to identify the essential chromatin regulators in cold tumors, especially in cold tumors with the immune-desert phenotype. Our research group’s public data for differentially-expressed proteins in ESCC tissues and corresponding paracancerous tissues (n = 124)23 was revisited and intersected with 138 chromatin regulators from published data. The results revealed that 15 of 138 chromatin regulators were overlapped, all of which were upregulated in ESCC, compared with paracancerous tissues (Fig. 1A), including CBX2, ATAD2, MSH6, PCNA, FXR1, EZH2, DNMT3A, SMARCC1, TBL1XR1, CBX3, SP110, CBX8, PHF6, KDM3A and CHD3. To narrow the list of 15 chromatin regulators, we analyzed RNA-seq data from ESCC tumor samples, not from normal controls, in TCGA database, and observed the correlation of chromatin regulators with CD8+ T cells while the data from tumor samples was grouped into low- and high-expression of chromatin regulators. As indicated in Fig. 1B, the expression of ATAD2, DNMT3A, EZH2, MSH6 and SMARCC1 correlated inversely with enrichment score of CD8+ T cells, suggesting that these highly-expressed chromatin regulators in tumor samples may inhibit the infiltration of CD8+ T cells. Since CD8+ T cells were absent in immune-desert tumors, we speculated that these five chromatin regulators might participate in absence of CD8+ T cells in immune-desert tumors. Conversely, SP110, distinct from these five genes, exhibited the favorable effect on enrichment score of CD8+ T cells. Up-regulated SP110 was observed in ESCC and thus SP110 was removed from the potential list, since immune-desert tumors were devoid of CD8+ T cells. Subsequently, IHC for ATAD2, DNMT3A, EZH2, MSH6 and SMARCC1 in ESCC with infiltrated (n = 13), immune-excluded (n = 23) and immune-desert (n = 14) phenotypes was individually conducted and evaluated by using H-Score, based on immunochemistry staining intensity (Fig. 1C and D). As demonstrated by Fig. 1D, The H-Score for either EZH2 or DNMT3A in immune-excluded and immune-desert tumors was higher than that in infiltrated tumors. Conversely, the H-Score for MSH6 decreased in immune-excluded and immune-desert tumors in comparison with infiltrated tumors. There was no distinction for ATAD2 H-Score among three immune phenotypes, which resembled to SMARCC1. Therefore, IHC score for these five chromatin regulators further confirmed that EZH2 and DNMT3A, but not ATAD2, MSH6 and SMARCC1, were up-regulated in immune-desert tumors, compared to infiltrated tumors, manifesting that EZH2 and DNMT3A may be involved in the absence of CD8+ T cells in immune-desert tumors. Collectively, both upregulated EZH2 and DNMT3A in immune-desert tumors attract our attention. Specially, whether either EZH2 or DNMT3A elicits dearth of CD8+ T cells in TME and reprograms it towards a milieu with the immune-desert phenotype merits additional study.

Fig. 1. Both EZH2 and DNMT3A are up-regulated in CD8+ T cell-desert TME.

A The Venn diagram shows the overlapped chromatin regulators between 138 previously published chromatin regulators and differentially-expressed proteins in ESCC/normal tissues. B Based on ESCC RNA-seq data from TCGA database, correlation analysis between 15 up-regulated chromatin regulators and CD8+ T cell enrichment was conducted. C IHC staining was used to detect the expression of 5 chromatin regulators in ESCC with three identified immunophenotypes. Scale bar: 20× magnification in whole images and 40x magnification in red box. D The H-SCORE immune score of 5 chromatin regulators in infiltrated, immune-excluded and immune-desert tumors. E Distribution of H-SCORE scores of 5 chromatin regulators.

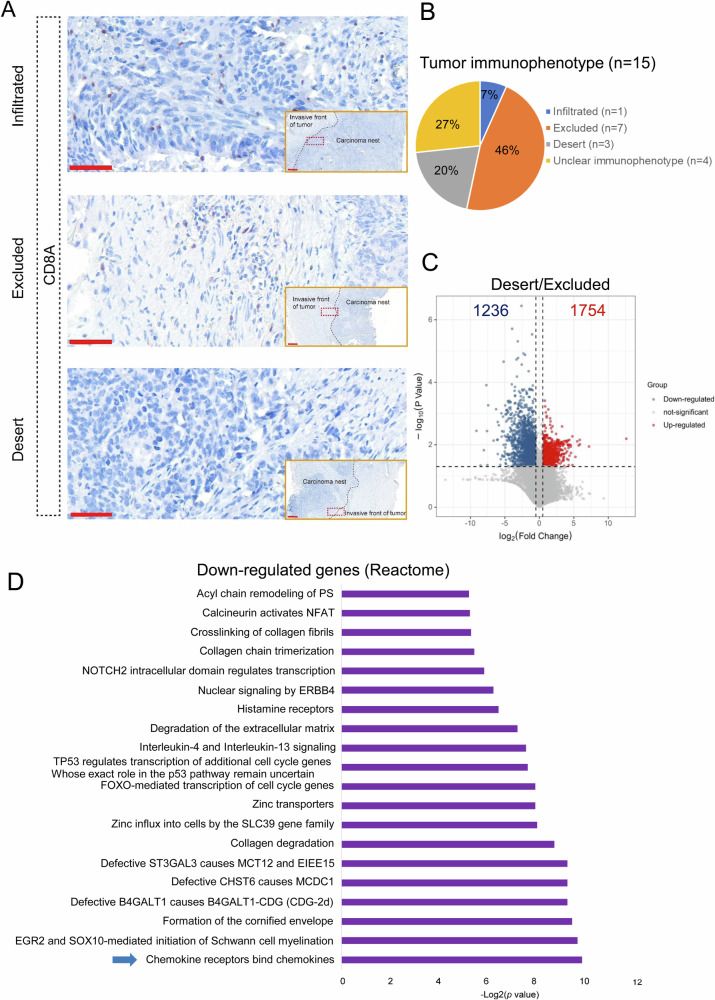

The levels of the potential chemokines are declined in immune-desert tumors in comparison with immune-excluded tumors

To mine the in-depth mechanism dominating the immune-desert phenotype, our previously published RNA-seq data for 15 ESCC samples (SRP064894 at Sequence Read Archive)24 was revisited because we had no RNA-seq data from the above 109 ESCC samples used for immunophenotype identification in Supplementary Fig. S1. We initially identified the immunophenotypes for 15 ESCC samples by spatial distribution of CD8+ T cells based on CD8A IHC staining, as indicated in Fig. 2A. 11 of 15 samples were classified into immune-desert tumors (n = 3), immune-excluded tumors (n = 7) and infiltrated tumor (n = 1) (Fig. 2B). Of note, “Unclear immunophenotype” was used to label the remaining four ESCC samples because the immunophenotypes for the four ESCC samples failed to be characterized by one of immune- infiltrated, immune-excluded and immune-desert phenotypes. E.g the immunophenotype characterized by poor number of CD8+ T cells only distributing in tumor stroma were not clear and labeled as “Unclear immunophenotype”. Due to the limited number (only 1 sample) for the infiltrated, we compared the transcriptomic difference between immune-desert tumors (n = 3) and immune-excluded tumors (n = 7) to attempt to identify the essential mechanism pointing to the immune-desert phenotype. In immune-desert tumors, 1236 down-regulated genes and 1754 up-regulated genes were observed while immune-excluded tumors were utilized as the control group, as shown in Fig. 2C. The signaling pathway enrichment analysis for these down-regulated genes showed that, among these signaling pathways, the most prominent chemokine pathway associated with chemokines was enriched (Fig. 2D). Of all chemokines, only four chemokines CXCL9, CCL4, CXCL13 and CXCL5 were enriched in the chemokine pathway, which were down-regulated in immune-desert tumors, compared to immune-excluded tumors. To further interrogate whether the expression levels of these chemokines originated from tumor cells were down-regulated in TME, we revisited single-cell RNA-seq data (GSE160269)25, which was contained in the database TISCH2, a scRNA-seq database focusing on TME. According to the database, we analyzed the expression of CXCL9, CCL4, CXCL13 and CXCL5 in immune cells and tumor cells. As indicated in Supplementary Fig. S2, CXCL9, CCL4, CXCL13 were predominant highly expressed in immune cells, whereas no expression for those chemokines were observed in tumor cells, indicated by malignant cells. Of note, the vast majority of immune cells and tumor cells show no expression of CXCL5. Intriguingly, previous studies documented that, of total four chemokines, three chemokines were involved in recruitment of CD8+ T cells22,26,27. Hence, given that EZH2 and DNMT3A were up-regulated in immune-desert tumors characterized with CD8+ T cells free, we next sought to interrogate whether EZH2 and DNMT3A restrain the expression of these four chemokines, thereby hindering the recruitment of CD8+ T cells.

Fig. 2. The levels of potential chemokines are declined in CD8+ T cell-desert TME in comparison with CD8+ T cell-excluded TME.

A IHC staining for CD8A was used to detect CD8+ T cells in 15 cases of ESCC samples. Scale bar: 2× magnification for invasive front of tumor and 20x magnification for red box. B The pie chart showed the proportion of infiltrated, immune-excluded and immune-desert tumors in 15 cases of ESCC samples. C Volcano plot was used to show differentially-expressed gene in immune-desert tumors compared with immune-excluded tumors [|Log2(Foldchange)|>0.5, P < 0.05]. D Signaling pathway enrichment analysis of down-regulated genes in immune-desert tumors was performed in Reactome database.

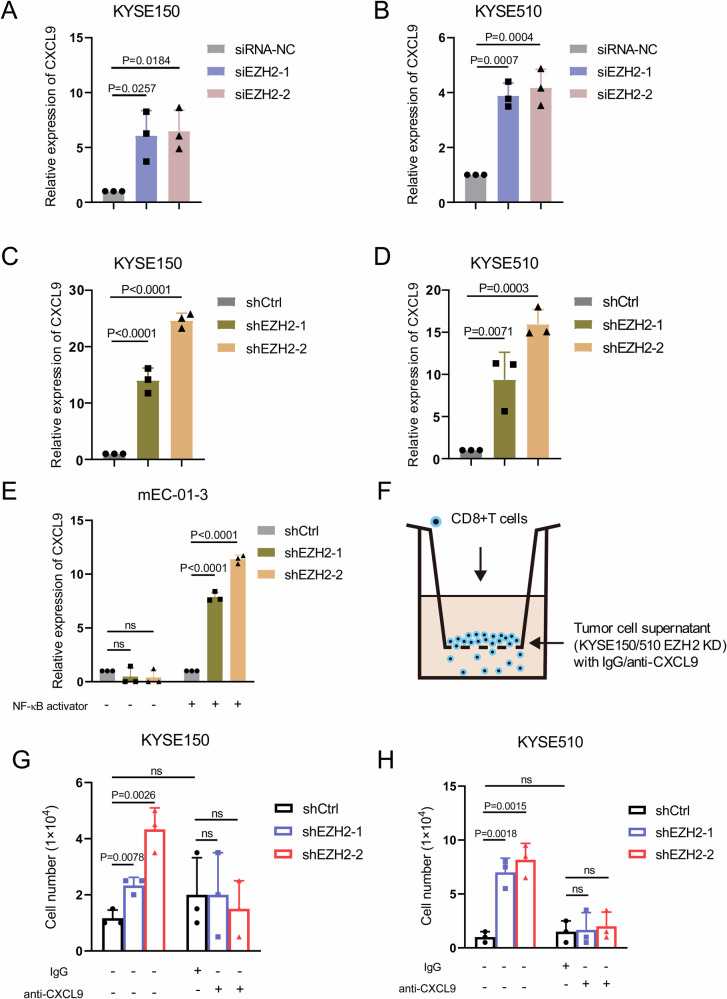

EZH2 depletion induces up-regulation of CXCL9 expression, boosting the recruitment of CD8+ T cells

DNMT3A, as a DNA methyltransferase to silence gene expression, the negligible expression was observed in KYSE150 and KYSE510 cells, resembling the endogenous negligible expression of CXCL9. Therefore, we speculate that DNMT3A does not engage in regulating the expression of CXCL9 (Supplementary Fig. S3A). In the differentially-expressed genes between immune-desert tumors and immune-excluded tumors, there was no DNMT3A, indicative of no change of DNMT3A expression between the both immunophenotypes, as demonstrated by its TPM value from RNA-seq (Supplementary Fig. S3B). Moreover, the results for DNMT3A IHC score further confirmed that the expression of DNMT3A was not altered in immune-desert tumors, compared to immune-excluded tumors (Fig. 1C, D), indicating that DNMT3A may not be correlated with the difference for the immunophenotype between immune-excluded tumors and immune-desert tumors. However, EZH2 was down-regulated in immune-desert tumors, compared to immune-excluded tumors, as demonstrated by EZH2 IHC score (Fig. 1C, D), indicative of the potential correlation of EZH2 with the difference between the both immunophenotypes. Additionally, signal pathway enrichment analysis showed that, of all chemokines, only four chemokines (CXCL9, CCL4, CXCL13, CXCL5) were enriched in the chemokine pathway, as indicated by the blue arrow in Fig. 2D, which were down-regulated in immune-desert tumors, compared to immune-excluded tumors. The previously published data showed that EZH2 in ovarian tumor repressed the tumor production of Th1-type chemokines CXCL928, a key chemokine for recruiting CD8+ T cells into TME, indicating that highly-expressed EZH2 in immune-desert tumors, compared to infiltrated tumors, may be associated with absence of CD8+ T cells. Notably, DNMT1, but not DNMT3A, was also reported to suppress the expression of CXCL928. Nevertheless, the reports on the correlation of DNMT3A with the expression of CXCL9, CCL4, CXCL13 and CXCL5 have been unavailable. Taken together, EZH2 caused our attention.

The predominant hallmark of EZH2 is embodied by trimethylating histone H3 at lysine 27 in the region of target gene promoter, ensuing the silence of gene transcription. Therefore, GSK126 targeting H3K27me3 was initially utilized to inhibit H3K27me3 and reverse the suppression of H3K27me3 to gene transcription. As seeable in Supplementary Fig. S4A and B, the levels of H3K27me3 were remarkably declined while GSK126 at the indicated concentrations was leveraged to treat KYSE150 and KYSE510 cells. In three repeated experiments, we observed that GSK126 at final concentration of 2.4 µM, relative to other indicated concentrations, sustained the ability to more obviously suppress the levels of H3K27me3 in either KYSE150 or KYSE510 cells and hereinafter the final concentration of 2.4 µM was referred to as an optimal concentrate for GSK126. Subsequently, the expression levels of the aforementioned chemokine CXCL9, CCL4, CXCL13 and CXCL5 were assessed upon GSK126 treatment. Of note, GSK126 treatment triggered the tremendous increase of CXCL9, rather than CCL4, CXCL13 and CXCL5, in KYSE150 cells, which was corroborated in KYSE510 cells (Supplementary Fig. S4C). Therefore, we paid attention to CXCL9. Previously published data insinuated that NF-κB directly bound to the promoter and modulated the transcription of CXCL9 29. Hence, we attempted to interrogate whether the increase of CXCL9 by GSK126 treatment is subverted by adding NF-κB inhibitor APDC to the GSK126-treated cells. Indeed, our data corroborated the prediction, the expression of CXCL9 was nearly imperceptible while adding GSK126 in conjunction with APDC, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S4D.

Furthermore, the decrease of EZH2 expression by either siRNA interference or establishment of shRNA-expressing stable cell lines including KYSE150 and KYSE510 cells elicited the increased expression of CXCL9, as seeable in Supplementary Fig. S5A–D and Fig. 3A–D. To interrogate whether these observations extrapolate to mouse esophageal squamous cell line mEC-01-3, which was newly established by our group, the expression of CXCL9 followed by EZH2 depletion (Supplementary Fig. S5E and F) was assessed. Slightly different from the observations in KYSE150 and KYSE510 cells, the expression of CXCL9 was negligible and failed to be reinforced despite EZH2 knockdown. Nevertheless, EZH2 knockdown, paralleled by addition of NF-κB activator (NF-κB activator 1), distinctly reinvigorated the expression of CXCL9, whereas NF-κB activator alone was ineffectual (Fig. 3E). We speculate that the activity of NF-κB per se in mEC-01-3 cells might be inert for the expression of CXCL9 upon EZH2 down-regulation, depending on NF-κB activator.

Fig. 3. Inhibition of EZH2 enhances CXCL9 transcription and promotes the recruitment of CD8+ T cells.

A, B The expression of CXCL9 in KYSE150 and KYSE510 cells was determined by using qRT-PCR after EZH2 gene silencing. C, D The levels of CXCL9 in either KYSE150 or KYSE510 stable cell lines expressing EZH2 shRNA and shCtrl (control) were measured by using qRT-PCR. E The levels of CXCL9 in mEC-01-3 were determined by using qRT-PCR after EZH2 depletion followed by NF-κB activator. F–H Transwell migration was utilized to detect the migration ability of CD8+ T cells after EZH2 knockdown in either KYSE150 or KYSE510 stable cell lines expressing EZH2 shRNA and shCtrl (control), as well as the changes in the migration ability of CD8+ T cells after EZH2 knockdown followed by CXCL9 blockade by anti-CXCL9 antibody. The above results represent mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD). n = 3 independent biological replicates.

The event of CXCL9 to recruit CD8+ T cells in the context of TME is well appreciated as the pivotal hallmark for CD8+ T cells exerting anti-tumor immunity. Given that EZH2 restricted the expression of CXCL9, we hypothesized that EZH2 depletion reinforced recruitment of CD8+ T cells by the increased expression of CXCL9. Hence, the transwell migration assays were established by adding CD8+ T cells to upper chamber and culture supernatants of tumor cells with EZH2 depletion to lower chamber, with or without anti-CXCL9 antibodies or normal IgG, as illustrated by Fig. 3F. As expected, the results revealed that the migration of CD8+ T cells was enhanced while culture supernatants derived from either KYSE510 or KYSE150 with cells EZH2 knockdown were added to the lower chamber. However, CXCL9 antibody blockade abrogated the increased migration of CD8+ T cells, as demonstrated by Fig. 3G and H. Therefore, we conclude that EZH2 depletion in ESCC activates the expression of CXCL9, thereby boosting CD8+ T cell recruitment.

EZH2 antagonizes the effect of NF-κB on the transcriptional activation of CXCL9 at its promoter

Since EZH2, related to trimethylation of H3K27 (H3K27me3), inhibited the expression of CXCL9, we sought to ask if EZH2 silences the transcription of CXCL9 at its promoter by H3K27me3. IGV analysis for both EZH2 and H3K27me3 ChIP-seq from Hela-S3, HepG2 and DND-41 cell lines, based on the data from the online download, insinuated binding peaks of EZH2 and H3K27me3 at the promoter of CXCL9 (Supplementary Fig. S6A), which was substantiated by ChIP-PCR for EZH2 and H3K27me3 in KYSE150 cells (Supplementary Fig. S6B, C). The results corroborate that EZH2 modulates the transcriptional silence of CXCL9 by H3K27me3 at its promoter. In addition, NF-κB, comprised of p50 (NFΚB1) and p65 (RelA), was previously validated to activate the transcription of CXCL9 29, enlightening us to interrogate whether EZH2 knockdown increases the expression of the expression of CXCL9 through up-regulating the expression of NF-κB. Inconsistent with our prediction, EZH2 knockdown did not alter the expression of p65 and p50 (Supplementary Fig. S6D). It is well known that p50, rather than p65, is regarded as a transcription factor, typically recognizing a collection of similar DNA sequence represented as binding site motifs, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S6E and p65 binds to the promoter of target genes, depending on p50. In the light of the JASPAR analysis for promoter sequence of CXCL9, we observed that the promoter of CXCL9 harbored the motif specific to p50 binding site (Supplementary Fig. S6E), which corroborated the previously published data on the regulation of NF-κB to CXCL929. Since EZH2 depletion did not provoke the alteration of the expression of p50, we subsequently set out to determine if EZH2 hinders the binding of p50 to the promoter of CXCL9. ChIP-PCR for p50 in KYSE150 cells with EZH2 depletion, based on the primers designed at the flank sequence of p50 binding site, was implemented and the results showed that there was no distinct change for p50 binding to the promoter of CXCL9 despite EZH2 knockdown. However, EZH2 knockdown followed by NF-κB activator treatment enhanced binding of p50 (Supplementary Fig. S6F–H), indicative of sustainable activation of NF-κB to CXCL9. Collectively, we conclude that, albeit NF-κB constitutively activates the transcription of CXCL9 in human ESCC, EZH2-mediated trimethylation of H3K27 presented at promoter of CXCL9 hinders its transcriptional revival, insinuating that EZH2 antagonizes the effect of NF-κB on the transcriptional activation of CXCL9.

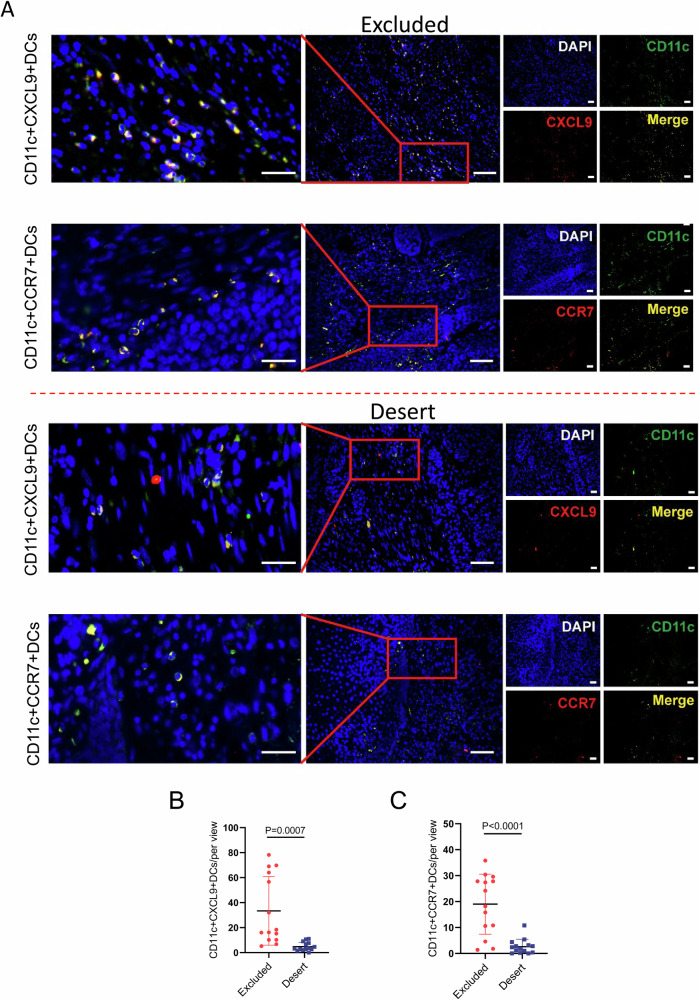

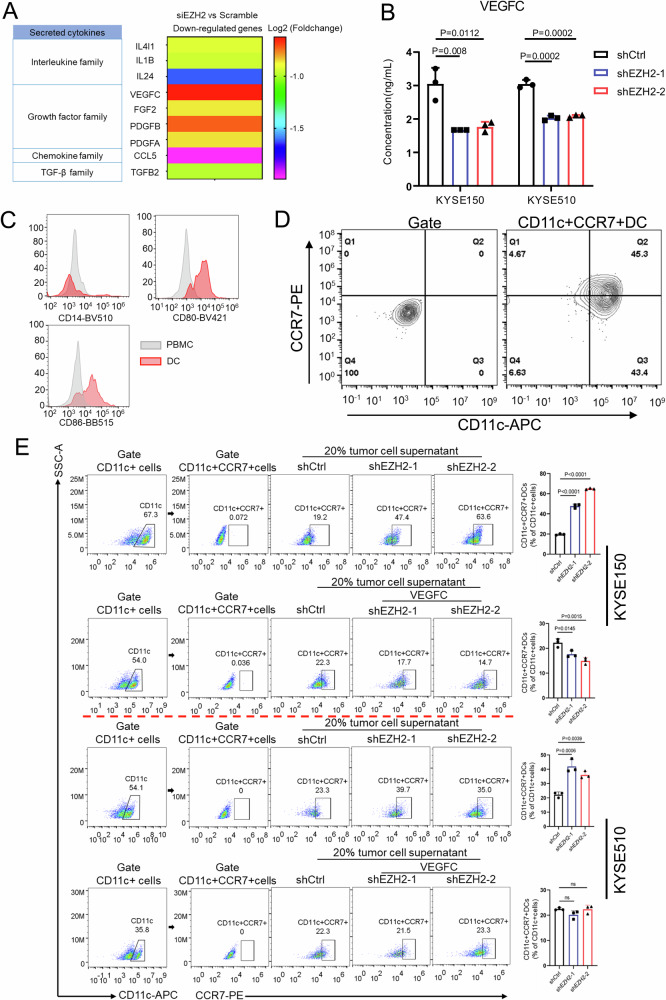

EZH2 dictates VEGFC secretion in ESCC and thereby inhibits dendritic cell (DC) maturation

Albeit tumor cell-intrinsic CXCL9 was deprived of transcriptional activation by EZH2, the previous single cell RNA-seq data for human ESCC unveiled dendritic cells as one of the predominant suppliers of CXCL9 in TME, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S2, which was consistent with the previous report for DCs as one of the main producers of CXCL930. DCs are activated and induced into mature DCs by uptake of foreign antigens, which facilitates to migrate to lymph nodes through the up-regulated expression of CCR7 and further endows the cognate CD8+ T cells with the adaptive immunity31,32. Given the low expression of CXCL9 in immune-desert tumors, relative to immune-excluded tumors (Fig. 2C), we speculate that immune-desert tumors are characterized with the paucity of mature dendritic cells expressing CXCL9 and CCR7. Subsequently, the assessment for CD11c + CXCL9+DCs or CD11c + CCR7+DCs by immunofluorescence staining substantiated the hypothesis, with fewer number of either CD11c + CXCL9+DCs or CD11c + CCR7+DCs in immune-desert tumors than immune-excluded tumors (Fig. 4A–C).

Fig. 4. The number of mature DC cells in CD8+ T cell desert TME is less than that in CD8+ T cell-excluded TME.

A Dual immunofluorescent staining for CD11c + CXCL9+DCs or CD11c + CCR7+DCs was used to identify the mature DCs in immune-excluded and immune-desert tumors. B, C Statistical analysis for CD11c + CXCL9+DCs and CD11c + CCR7+DCs in immune-excluded (n = 14) and immune-desert tumors (n = 14) were conducted. At least five individual fields were chosen for each of samples. Scale bar: 40x magnification for left panels and 20× magnification for the rest of images.

To further interrogate whether and how tumor cell-intrinsic EZH2 affects the dearth of CD11c + CXCL9+DCs or CD11c + CCR7+DCs, it is necessary to identify the potential cytokines that bridge EZH2 and DCs. RNA-seq from EZH2 depletion in KYSE150 cells was conducted. The differentially-expressed genes were shown with heatmap (Supplementary Fig. S7) and there were 462 up-regulated genes and 446 down-regulated genes upon EZH2 knockdown. The differentially-expressed cytokines characterized by secretory proteins, generally comprised of interleukins, growth factors, chemokines and TGF-β family, were retrieved and outlined from the down-regulated genes in the light of the criteria with Log2 (Foldchange) ≤-0.5 and p value < 0.05, as shown in Fig. 5A. Finally, total 9 cytokines were available. Since the previously published data revealed that both VEGF and TGF-β caused the defect of the functional maturation of DCs33–35, the investigation for the effects of both VEGFC and TGFB2 in these acquired 9 cytokines on maturation of DCs was desirable. The secretion of both VEGFC and TGF-β2 (TGFB2) derived from human ESCC cell lines was initially determined by using Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) upon EZH2 knockdown and the results validated that EZH2 depletion distinctly diminished the secretion of VEGFC, as shown in Fig. 5B, but not of TGF-β2 (Supplementary Fig. S8A), which was congruent with the decreased secretion of VEGFC by EZH2 knockdown in mEC-01-3 cells (Supplementary Fig. S8B). Next, we further investigated the effect of VEGFC on DC maturation. Monocytes from PBMC were separated and induced into DCs, as demonstrated by flowcytometric analysis for CD14-CD80 + CD86+DCs (Fig. 5C), and subsequently the maturation of DCs was further substantiated by flowcytometric analysis for CD11c + CCR7+DCs, accounting for 45.95 ± 0.85% (n = 3) (Fig. 5D). We next sought to interrogate whether VEGFC acts as the opponent to DC maturation. Tumor cell culture supernatants from KYSE150 cells with either EZH2 shRNAs or shCtrl were respectively supplemented during the differentiation of DCs into maturation. Compared with shCtrl, the frequency of CD11c + CCR7+DCs supplemented with tumor cell culture supernatants from the cells expressing EZH2 shRNAs was greatly increased, as illustrated by Fig. 5E (Top row), insinuating that the inhibitory effect of VEGFC in tumor cell culture supernatants on DC maturation was abrogated due to its decrease caused by EZH2 depletion. To further substantiate the abrogation of the inhibition for DC maturation was implemented by VEGFC decrease, exogenous VEGFC was added to rescue the levels of VEGFC in the culture supernatants from the cells with EZH2 knockdown, which was supplemented to the culture media for DC maturation. As demonstrated by Fig. 5E (Second row), the frequency of CD11c + CCR7+DCs was not increased, but rather decreased, while VEGFC was added to the supernatants from the cells with EZH2 knockdown. Similarly, the inhibition of VEGFC to DC maturation was abrogated during DC maturation supplemented with the culture supernatants from KYSE510 cells expressing EZH2 shRNAs, compared with shCtrl (Fig. 5E, Third row), while exogenous VEGFC rescued its inhibition to DC maturation (Fig. 5E, Bottom row).

Fig. 5. EZH2 promotes VEGFC secretion in ESCC and thereby inhibits DC maturation.

A RNA-seq was performed after EZH2 knockdown in KYSE150 cells and the down-regulated genes associated with secretory cytokines were shown according to the requirement: |Log2(Foldchange)|>0.5, P < 0.05. B The levels of VEGFC secreted by either KYSE150 or KYSE510 cells after EZH2 knockdown were detected by ELISA. C, D Flow cytometry was used to determine monocytes differentiated into DCs by anti-CD14, anti-CD80 and anti-CD86 staining for PBMC and DCs. E The percentage of induced mature DC cells was measured by using flow cytometry while culture supernatants from either KYSE150 or KYSE510 cells with EZH2 knockdown, or the supernatants supplemented with VEGFC, were incubated with the differentiated DCs. The above results represent the mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD). n = 3 independent biological replicates.

Provocatively, given that EZH2 dictates the secretion of VEGFC, the mechanism that underpins the regulation of EZH2 to VEGFC expression is still elusive. Enrichment analysis from the ChIP-Atlas database for the potential candidates binding to the promoter of VEGFC was conducted and foldchange score for the individual candidates, depending on multiple ChIP-seq data, was more than 1, manifesting the potential binding. In this vein, 227 candidates were acquired and further intersected with the down-regulated 550 genes by EZH2 knockdown to further narrow the candidate list. Intriguingly, EZH2 was enlisted in the final candidate list comprised of overlapped 18 candidates (Supplementary Fig. S9A), suggesting that EZH2 may direct the expression of VEGFC through binding to its promoter or enhancer. The online download EZH2 ChIP-seq data from multiple types of cells insinuates the binding peaks of EZH2 at the promoter of VEGFC, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S9B, which was corroborated by the ChIP-PCR results in KYSE150 cells (Supplementary Fig. S9C). Combined with the observations for EZH2 depletion eliciting the reduction of the secretion of VEGFC, we speculate that EZH2 modulates favorably the secretion of VEGFC through binding to its promoter, further restraining DC maturation.

Also, based on the single-cell data25, the tumor samples were grouped into VEGFC-high group and VEGFC-low group. Then the relationship between VEGFC and the types and quantities of DCs was further observed and the results showed that the percentage of cDCs was higher in VEGFC-low group than VEGFC-high group. However, the percentage of both pDC and tDC was higher in VEGFC-high group than VEGFC-low group (Supplementary Fig. S10A, B). After all kinds of myeloid cells were clustered by tSNE analysis, we observed the distribution of CXCL9 and CCR7 expression in cDCs (Supplementary Fig. S10C–E), demonstrating that VEGFC inhibits the maturation of CXCL9 + CCR7+DCs in TME.

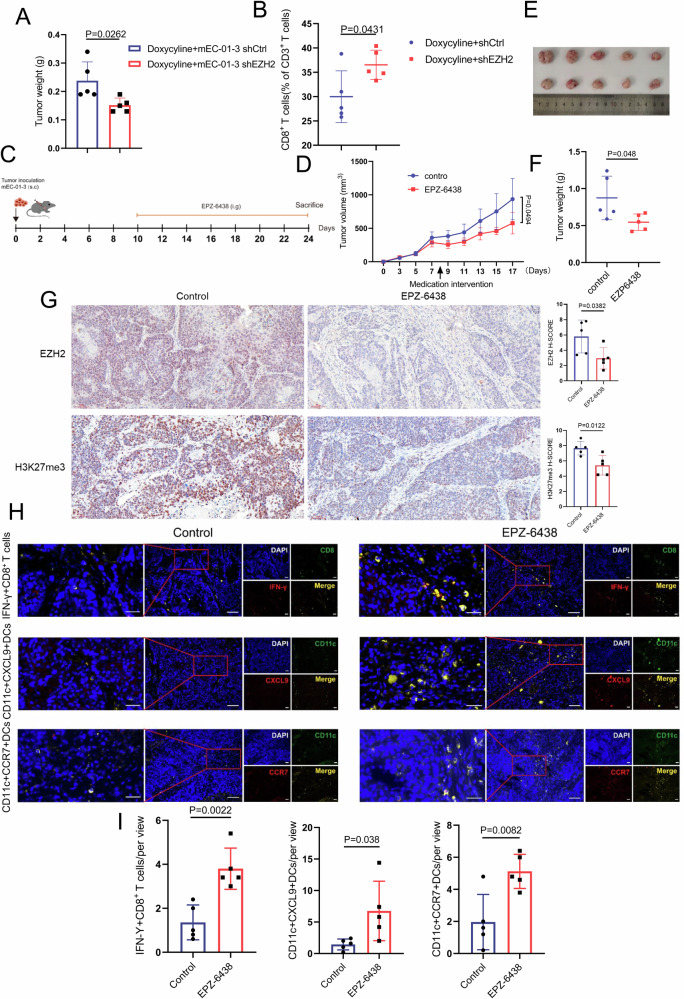

Targeted EZH2 restricts the growth of ESCC through reinforcing the infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and mature DCs into TME

mEC-01-3 cells with doxycycline-inducible Tet-On system expressing EZH2 shRNA was generated and subcutaneously inoculated in immune-competent C57BL/6 mice. The growth of tumor was restricted upon EZH2 in mEC-01-3 cells was down-regulated via doxycycline-inducible Tet-On system expressing EZH2 shRNA, compared with shCtrl group (Fig. 6A). Moreover, the infiltration of CD8+ T cells was increased (Fig. 6B). In vitro clone formation assays unveiled that the expression alteration of EZH2 per se had no effect on the growth of mouse ESCC (Supplementary Fig. S11), insinuating that the recruited CD8+ T cells owing to EZH2 depletion in the TME exert anti-tumor immunity and thereby inhibit the growth of mouse ESCC. Additionally, Tazemetostat, a selective inhibitor of EZH2, was utilized to treat immune-competent mice bearing mEC-01-3 by oral gavage as 50 mg/kg per day. Relative to control group, Tazemetostat treatment remarkably restricted the growth of mouse ESCC (Fig. 6C–F). Notably, IHC score for EZH2 and H3K27me3 showed that both EZH2 and H3K27me3 levels were declined in EPZ-6438 treatment group, compared to control group (Fig. 6G). Accordingly, the assessment for CD8+ T cells in TME was in accordance with the observations for the growth. Dual immunofluorescent staining for INF-γ + CD8+ T cells (cytotoxic CD8+ T cells) showed the increased infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells by EPZ-6438 treatment in comparison with control. Similarly, EPZ-6438 treatment elicited the increased infiltration of CD11c + CXCL9+DCs or CD11c + CCR7+DCs (Fig. 6H, I). Our data insinuates that targeted EZH2 may provide a therapeutic regimen for patients with ESCC.

Fig. 6. The depletion of EZH2 in mouse ESCC enhances the infiltration of CD8+ T cells into TME.

A mEC-01-3 cells with doxycycline inducible Tet-on system expressing shEZH2 or shCtrl were subcutaneously injected into the right side of female C57 BL/6 J mice (n = 5). The image for the mice was created by Chun-Yan Zhu using Adobe illustrator. Drinking water contained 2 mg/mL doxycycline and 10 mg/mL sucrose. Tumor weight was determined while doxycycline induced Tet-on system expressing shEZH2 or shCtrl in mEC-01-3 cells. B Flow cytometry was used to detect the infiltration of CD8+ T cells in mouse ESCC. C Schematic diagram indicated that mEC-01-3 cells were subcutaneously injected into the right side of female C57 BL/6 J mice (n = 5). After 10 days, EPZ-6438 resolved in water containing 0.5% NaCMC and 0.1% Tween-80 was administrated at 50 mg/kg/day by oral gavage. The mice in control group were administrated by water containing 0.5% NaCMC and 0.1% Tween-80. (D) Tumor growth curve of tumor-bearing mice. E Tumors were dissected from tumor-bearing mice after treatment. F Tumor weight analysis for each of groups. G The analysis of IHC score for EZH2 and H3K27me3 in either EPZ-6438 treatment or control group was conducted. Scale bar: 20× magnification. H, I The infiltrated cytotoxic IFN-γ + CD8+ T cells, CD11c + CXCL9+DCs and CD11c + CCR7+DCs in mouse ESCC TME after EPZ-6438 treatment were counted and used for statistical analysis. At least five individual fields were chosen for each of samples. The above results represent the mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD). Scale bar: 40× magnification for left panels and 20x magnification for the rest of images.

Discussion

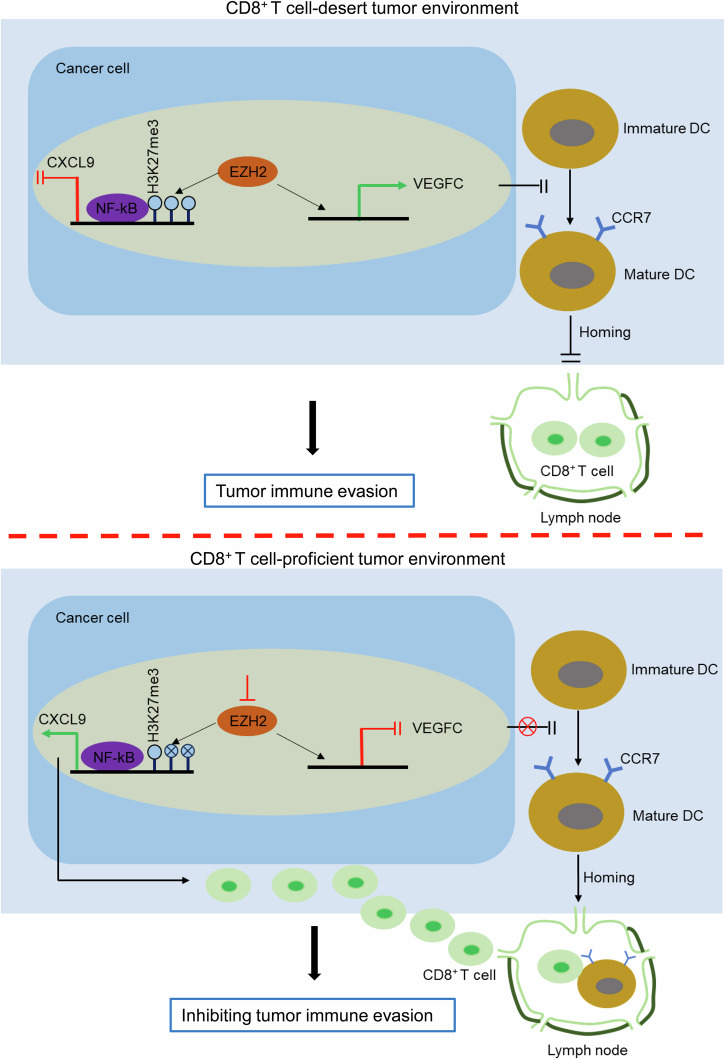

Hitherto, for ESCC, the immune-desert immunophenotype has not yet been mentioned, much less is known about the mechanism underpinning the unique immunophenotype. In the present study, we propose the model for targeted EZH2 enhancing the recruitment of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells into TME with the immune-desert phenotype, leading to inhibition of tumor immune evasion. As demonstrated by Fig. 7, in immune-desert tumors, tumor cell-intrinsic EZH2 with high expression antagonizes the transcriptional activation of CXCL9 mediated by NF-κB at its promoter through catalyzing the trimethylation of histone 3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3), ensuing the inhibition of CXCL9 recruiting CD8+ T cells into TME. Concomitantly, EZH2 directs favorably the transcriptional activation of VEGFC at its promoter and further impedes the differentiation of DCs from immature to mature, as indicated by CCR7, leading to the disruption of lymph homing for mature DCs and the failure of DCs cross-presenting tumor antigens to prime naive CD8+ T cells and finally, no active CD8+ T cells migrate into TME. In contrast, targeted EZH2 revives the recruitment of CD8+ T cells by up-regulated CXCL9 and concomitantly initiates the mature differentiation of DCs and lymph homing and further reinvigorates the infiltration of CD8+ T cells, finally reversing CD8+ T cell-desert TME into CD8+ T cell-proficient TME and inhibiting tumor immune evasion. Indeed, in TME, CXCL9, which is derived from tumor cells as well as mature DCs-expressing CCR7, recruits CD8+ T cells infiltrating into TME36,37. In the present study, we demonstrated that tumor cell-intrinsic EZH2 with high expression suppressed the transcriptional activation of CXCL9, leading to the inhibition of CD8+ T cells infiltrating into TME. However, presumably, few mature DCs in immune-desert tumors leads to the defect of tumor antigens to prime naïve CD8+ T cells as well as lack of DC-derived CXCL9. It is difficult to eliminate the effect of lack of DC-derived CXCL9 on the failed recruitment of CD8+ T cells in immune-desert tumors, since tumor cell-intrinsic EZH2 inhibited maturation of DCs via regulating secretion of VEGFC. Therefore, we consider that EZH2-mediated transcriptional suppression of CXCL9 in tumor cells and lack of DCs-derived CXCL9 due to DC absence are intertwined to orchestrate the deficiency of CD8+ T cells in immune-desert tumors, resulting in tumor immune evasion. Although some mechanism underlying immune-desert tumors was delineated in other types of cancer, such as low TMB (tumor mutation burden), defective tumor antigen processing and presentation and dysfunctional interaction between DCs and T cells1, our findings uncover the novel mechanism underpinning the specific immunophenotype for ESCC in the light of epigenetic regulation.

Fig. 7. The diagram for the mechanism for targeted EZH2 reversing CD8+ T cell-desert tumors into CD8+ T cell-proficient tumors.

The diagram was created by Guo-Wei Huang using Microsoft PowerPoint.

Clinically, a large fraction of patients with ESCC fail to benefit from the indiscriminate treatment modality, including chemoradiotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy. Specially, we fail to bypass the fact that there is no effective target hold true for targeted therapy. Precision and personalized medicine for cancer treatment becomes a pressing need for patients with ESCC38. Our data revealed that targeted EZH2 significantly restricted the growth of ESCC, insinuating the feasibility of targeted therapy for patients with immune-desert tumors by utilizing EPZ-6438 to selectively target EZH2. Notably, EPZ-6438 was approved by FDA in the USA in 2020 to treat adults and adolescents over 16 with epithelioid sarcoma not eligible for complete resection, characterized by local advance or metastasis39, while there has not yet been available approval in China. EPZ-6438 treatment provokes the increased infiltration of CD8+ T cells, indicating the feasibility of the combination of EPZ-6438 with chemotherapeutic agents ultimately depending on CD8+ T cell anti-tumor immunity, such as both oxaliplatin and cyclophosphamide40,41. Additionally, EPZ-6438 treatment potentiates response to PD-1 checkpoint blockade in pre-clinical model for prostate cancer19. Therefore, our data indicates the feasibility of EPZ-6438 in conjunction with PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor to treat patients with ESCC.

Albeit that EZH2, as the key catalytic subunit of polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), canonically catalyzes trimethylation of Histone 3 at lysine 27 and thereby silences the expression of target genes, growing evidence unveils that EZH2 noncanonically activates the gene transcription through the PRC2-independent pathway42,43. Indeed, EZH2 is not a transcription factor. However, EZH2, as a transcriptional coactivator, can also be recruited to active chromatin independent of PRC2, albeit the mechanism for recruiting EZH2 is still unclear44. In another report45, the authors demonstrated that EZH2 directly bound to the promoter of Neat1 through the SANT2 domain by using EZH2 ChIP-seq, ChIP-PCR and EMSA. For the detailed mechanism, EZH2 functions through its SANT2 domain to bind to the Neat1 gene promoter to maintain H3K27ac enrichment, thus facilitating p65-mediated Neat1 transcription. Concomitantly, p53 competes with EZH2 to bind to the promoter and recruits SIRT1 to deacetylate H3K27, leading to suppression of Neat1 transcription. In the present study, our data manifested that EZH2 promoted the transcriptional activation of VEGFC via binding to its promoter, which was in line with the above reports. However, the in-depth mechanism underpinning EZH2 to participate in the transcriptional activation of VEGFC is still unclear and needs to be further investigated.

Herein, our data evidenced that EZH2, as a pivotal factor, programmed the immune-desert phenotype by inhibiting the expression of tumor cell-intrinsic CXCL9, paralleled by promoting the secretion of VEGFC to restrict the mature differentiation of DCs, which would lead to the failure of DC lymph node homing and the process of DCs priming the antigens to naïve CD8+ T cells. Finally, the recruitment for CD8+ T cells into TME was deficient in immune-desert tumors. Indeed, relative to infiltrated tumors, EZH2 was also highly expressed in immune-excluded tumors, which called into question how to direct the program of the immune-desert and the immune-excluded phenotypes while highly-expressed EZH2 was observed in the both phenotypes. Our findings revealed that the number of mature DC population in immune-desert tumors was less than that in immune-excluded tumors and the infiltrated CD8+ T cells were aggregated in invasive margin of immune-excluded tumors, insinuating that EZH2 may be not the key factor essential for the programing of the immune-excluded phenotype. Additionally, it is possible that there is the unique mechanism to antagonize the inhibition by EZH2 to the mature differentiation of DCs and smooth the process of DC mature differentiation in immune-excluded tumors. Thus, mature DCs recruits CD8+ T cells by secreted CXCL9 and primes tumor antigen to naïve CD8+ T cells in lymph nodes, further facilitating CD8+ T cells homing to tumors30. Therefore, for EZH2, whether and how to program the immune-excluded phenotype needs to be investigated in the following study.

In our pre-clinical model, depletion of tumor cell-intrinsic EZH2 induced up-regulation of CXCL9 to recruit CD8+ T cells, thereby exerting anti-tumor immunity. Of note, it is possible that up-regulated CXCL9 exerts anti-tumor immunity by recruiting NK cells in addition to CD8+ T cells46. Additionally, increasing evidence has documented that CXCL9 derived from tumor cells shows a dual role, as a tumor suppressor or a tumor promoter, in regulating tumor growth. One hand, CXCL9 derived from tumor cells recruits CD8+ T cells by the paracrine CXCL9-CXCR3 axis to act as a tumor suppressor. The other hand, tumor cell-intrinsic CXCL9 promotes the proliferation and metastasis of tumor cell via the autocrine CXCL9-CXCR3 axis47,48. Therefore, we speculate that, albeit paracrine axis elicited by CXCL9 due to EZH2 depletion inhibits the growth of tumor in our pre-clinical model, the existence of the autocrine axis may lead to the failure of complete elimination of tumor, suggesting that cancer treatment may benefit from the combination of targeted EZH2 with deactivation of autocrine axis.

In summary, our findings decode the novel mechanism in ESCC characterized by the immune-desert phenotype and point to avenues for treating a subset of patients with immune-desert tumors.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples and cell culture

109 cases of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor tissues dissected from patients with ESCC were collected from the Department of pathology of cancer Hospital of Shantou university medical college. Only treatment-naïve patients were included in the present study. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of cancer Hospital of Shantou university medical college and the Medical College of Shantou University, and written informed consent was obtained from all surgical patients to use resected samples and clinical data for research and all ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed. KYSE150 and KYSE510, human ESCC cell lines, were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium and HEK293T cell line was maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM). The medium was supplemented with 10% FBS (Hyclone, New Zeland).

Immunochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence

Deparaffinized and rehydrated tissue sections were subjected to the blockade of intrinsic peroxidase by 3% hydrogen peroxide and antigen retrieval in 0.01 M citric acid buffer (pH 6.0). Sections were blocked by 5% horse serum (Solario, Beijing, China) at 37°C for 30 min and then individually incubated with rabbit anti-CD8A antibody (1:100, NBP2-29475, Novus biologicals, Colorado, USA), rabbit anti-EZH2 (1:50, 5246, Cell signaling technology, MA, USA), rabbit anti-ATAD2 (1:80, 50563, Cell signaling technology, MA, USA), rabbit anti-DNMT3A (1:100, 19366-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), rabbit anti-MSH6 (1:1000, 18120-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China) and rabbit anti-SMARCC1 (1:1000, 100848-T42, Sino biological, Beijing, China) overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, a PV-9000 two-step polymer detection system and an AEC peroxidase substrate kit (ZSGB-BIO, Beijing, China) were utilized for IHC staining. IHC score for each of tissue sections was independently implemented by two histopathologists according to the procedures that He et al. provided17. The above sections were also used for dual immunofluorescent staining. The antibody combination of rabbit anti-CXCL9 (1:100, bs-2551R, Bioss, Beijing, China) or rabbit anti-CXCR7 (1:100, bs-1305R, Bioss, Beijing, China) with mouse anti-human CD11c (1:100, 60258-1-Ig, Proteintech, Wuhan, China) were used as primary antibodies for determining mature DCs in human immune-excluded tumors and immune-desert tumors. To measure mouse mature DCs, the antibody combination of rabbit anti-CXCL9 (1:100, bs-2551R, Bioss, Beijing, China) or rabbit anti-CXCR7 (1:100, bs-1305R, Bioss, Beijing, China) with Armenian hamster anti-mouse CD11c (1:100, 14-0114-82, Thermo Fisher Scientific, CA, USA) was used to incubate with the sections overnight at 4°C and CoraLite594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) (1:200, SA00013-4, Proteintech, Wuhan, China) and goat anti-Armenian hamster IgG HL(Alexa Fluor488) (1:200, ab173003, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) were used as secondary antibodies. To determine mouse cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, rat anti-mouse IFN-γ (1:100, MAB485-SP, R&D systems, MN, USA) combined with rabbit anti-CD8A antibody (1:100, NBP2-29475, Novus biologicals, Colorado, USA) was used as the primary antibodies and incubated with the sections overnight at 4°C. After three washes with PBS, Rhodamine (TRITC)-goat anti-rat IgG (H + L) (1:100, SA00007-11, Proteintech, Wuhan, China) and Coralite488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG(H + L) (1:500, SA00013-1, Proteintech, Wuhan, China) were incubated with the sections at 37°C for 30 min. Finally, photographs were taken by immunofluorescence microscope (ZEISS, Image A2, Germany) after the sections were stained with DAPI.

Transwell migration assays

Human CD8+ T cells were seeded in upper chamber of 5 μm transwell filters (Corning, NY, USA) and culture supernatants of tumor cells with shEZH2-1, shEZH2-2 and shCtrl were added to the bottom chamber, with or without 100 ng/mL of rabbit anti-human CXCL9 antibody or isotype IgG. After 12 h, the migrated CD8+ T cells to the bottom chamber were counted.

Flow cytometry

DCs were collected and suspended in staining buffer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) as 1×106/ml. After two wishes by staining buffer, DCs were suspended in 100 μL of staining buffer. The antibodies were added to the cell suspension and allowed to incubate on ice for 30 minutes in a dark environment. Subsequently, the samples were subjected to flow cytometry analysis using a BD Accuri C6 FACS cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) after two rounds of washing. For the flowcytometric analysis of mouse CD8+ T cells, the tumors extracted from the established mouse ESCC models were minced into small pieces (1-2 mm3) and then further digested by collagenase type I (17100017, Thermo Fisher Scientific, CA, USA) at the final concentration of 50 μg /mL in DMEM. Finally, the cell suspension was prepared in staining buffer as 1×106/ml for flowcytometric analysis. Flowjo software (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA)) was utilized to analyze the FACS data. The following antibodies from BD biosciences were utilized in the flow cytometry analysis:

Human DCs were stained with the following antibodies: anti-CD14 BV510 (1:100, 563079, anti-CD80 BV421 (1:100, 566285) and anti-CD86 BB515 (1:100, 564545). Mature DCs were stained with anti-CCR7 PE (1:100, 552176) and anti-CD11c APC (1:100, 560895). Murine CD8+ T cells were stained with the following antibodies: anti-CD3e FITC (1:100, 553061), anti-CD8 APC (1:100, 555369).

CD8+ T cell isolation and cell culture

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were extracted from 20 ml blood samples of healthy adult donors (n = 3) and human CD8+ T cells were isolated from human PBMC by using Mojosort human CD8+ T isolation kit (Biolegend, USA). Isolated CD8+ T cells were cultured in x-vivo 15 media (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) supplement with IL-2 and IL-15 (Genescript, Nanjing, China).

Tumor cell culture supernatants inhibit monocyte-derived dendritic cell mature differentiation

Monocytes were collected after human PBMC were cultured in serum-free 1640 medium at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 3 h. Subsequently, 100 μg/L rhIL4 and 100 μg/L rhGM-CSF (Genescript, Nanjing, China) were added to 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and after 5 days, 100 ng/mL LPS and 500 U/mL IFN-γ (Genescript, Nanjing, China), or combined with 20% tumor cell culture supernatants from EZH2-knockdown KYSE150 cells, were added to the medium. After 8 days, mature dendritic cells were measured by using flow cytometry.

Real-time RT-PCR and western blot

The extracted total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis that was implemented by using a PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit and then synthesized cDNA was used for real-time PCR by using a SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ kit (Takara, Dalian, China). PCR primer sequences were shown in Supplementary Table S2. As for western blot, the proteins were separated by using 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to Nitroncellulose membrane (NC) (10600002, Whatman). The primary antibodies were then individually incubated with the NC membrane blocked by using 5% BSA (A8020, Solario, Beijing) at 4°C overnight. Rabbit anti-EZH2 rabbit anti-EZH2 (1:1000, 5246, Cell signaling technology, MA, USA), rabbit anti-β-Actin (1:5000, 4967, Cell signaling technology, MA, USA), rabbit anti-H3K27me3 (1:1000, 39055, Active motif, CA, USA), mouse anti-p50 (1:2000, 66992-1-Ig, Proteintech, Wuhan, China) and rabbit anti-p65 (1:1000, 10745-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China) were used as the primary antibodies. IRDye 800 goat anti-mouse IgG and IRDye 680 anti-rabbit IgG were used as the secondary antibodies. Protein levels were visualized and analyzed using LI-COR Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA).

siRNA transfection and establishment of stable shRNA-expressing cells or Tet-On-mediated shRNA-expressing cells

siRNA transfection assays were conducted according to the procedures43. siRNA sequence was shown in Supplementary Table S3. To establish stable shRNA-expressing cells, viral particles were packaged and collected after the plasmids of pLKO-shEZH2-1, pLKO-shEZH2-2 and pLKO-shCtrl were individually transfected into HEK293T cells with package plasmids. Either KYSE150 or KYSE510 cells were infected by the collected viral particles and subsequently puromycin was added to screen the cells expressing shRNAs. To establish Tet-On-mediated shRNA-expressing cells, the plasmids of pLKO-shEZH2-1, pLKO-shEZH2-2 and pLKO-shCtrl with doxycycline inducible Tet-On system were packaged and viral particles were used to infect mEC-01-3 cells and finally the stable cell line was screened by using puromycin according to the above procedures. All the cells were passaged to 6th generation and the levels of EZH2 were measured with real-time RT–PCR or western blot after doxycycline (dox) (Beyotime, Suzhou, China) with 2 μg/mL was added to induce the initiation of Tet-on system in the screened cell lines. shRNA sequence was shown in Supplementary Table S4.

Cell colony formation assays

Cells were plated in a six-well plate for 12 days and then the colonies were stained by using crystal violet staining solution and counted.

RNA-seq

Total four cell samples were used for the RNA-seq analysis, including two repeated siRNA-treated KYSE150 cells (siEZH2-1, siEZH2-2) and two repeated controls (Scramble-1 and Scramble-2). siRNAs against EZH2 or Scramble were transfected into KYSE150 cells and at 48 h post-transfection, total RNA was isolated by using a RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Subsequently, poly-A containing mRNA purification, mRNA fragmented into small pieces, cDNA library preparation and RNA-seq were performed by BGI (Shenzhen, China). The analysis for RNA-seq data was also implemented by Dr. Tom system (BGI, Shenzhen, China).

ChIP-PCR

The ChIP-PCR assays were performed as our previously published procedures49. Rabbit anti-EZH2, rabbit anti-H3K27me3 (Active motif, CA, USA) and normal rabbit IgG (cell signaling technology, MA, USA) were individually incubated with the sonicated nuclear lysates of KYSE150 cells overnight at 4°C, while either mouse anti-p50 or mouse normal IgG (Proteintech, Wuhan, China) was respectively added to the sonicated nuclear lysates of KYSE150 cells with shEZH2-1, shEZH2-2 and shCtrl. In each of groups, DNA was extracted from DNA-protein complexes pulled down by protein G magnetic beads (Thermo fisher scientific, CA, USA) and used for PCR. The ChIP-PCR primers were shown in Supplementary Table S2.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The ELISA assays were conducted as manufacturer’s instructions. Human VEGFC, TGF-β2 and mouse VEGFC ELISA kits were ordered from Dldevelop Co.,Ltd (Wuxi, China). Briefly, supernatants were collected and dead cells and debris were removed by centrifuge at 1000 rcf for 20 min. The secreted cytokines in the collected supernatants were analyzed by using ELISA kit. Optical densities (OD) were determined by using PowerWave XS microplate spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments) at 450 nm and cytokine concentrations (ng/mL or pg/mL) were calculated as standard curve established by standards that the kit provided. Final cytokine concentrations were multiplied by the diluted foldchange.

Mice

Animal experiments were approved by the Animal Policy and Welfare Committee of Shantou University Medical College. mEC-01-3 cells were subcutaneously injected into the right flank of six-week-old female C57BL/6 mice (Beijing Weitonglihua Co., Ltd., China) (4.0 × 106 cells / flank). After 10 days, mice were subjected to EPZ-6438 administration by oral gavage as 50 mg/kg/day. Similarly, tumor-bearing mouse models for Tet-On-mediated mEC-01-3 cells with shEZH2 (herein, namely shEZH2-2) and shCtrl were established. 2 mg/mL doxycycline and 10 mg/mL sucrose were added to drinking water and maintained through all lifetime. The tumor volume was measured every two days according to our previously published method24. When the tumor reached a maximum size of 1.5 cm, which was allowed by the Animal Policy and Welfare Committee of Shantou University Medical College, tumors were collected and weighed after all mice were euthanized by inhalation of CO2. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analyses were implemented by using SPSS 19.0 for Windows (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) and two-sided Student’s t-test was utilized to compare the means of data between two groups. The statistically significant P values were less than 0.05. All experiments used for statistical analysis were independently repeated at least three times. Additionally, for colony formation, qPCR assays, each sample was determined in triplicate. Human sample experiments included 12 biological replicates.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (2021A1515010663), Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province of China (210713176903477, 210715116901229), Innovative Team Grant of Guangdong Department of Education (2021KCXTD005), The National Natural Science Foundation of China (82372032, 82003221), Science and Technology Innovation Strategy Special Project of Guangdong Province City and County Science and Technology Innovation Support (STKJ2023006), Shantou Central Hospital Research Incubation Program (201905) and Science and Technology Projects of Shantou (200601155261081).

Author contributions

G.W.H., F.P., S.Q.Q and T.T.Z contributed to the concept and design of the study. C.Y.Z, Q.T., M.S., H.C.P., B.H., X.R.C, N.L and L.H.X performed and analyzed all experiments. G.W.H. wrote the manuscript. F.P., S.Q.Q and T.T.Z contributed to the review and revision of the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Xiannian Zhang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Dario Ummarino. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The data in the present study is available within the published paper and its Supplementary file. The source data behind the graphs in the paper can be found in Supplementary Data 1 and the raw Western blot images are available in Supplementary Fig. S12. Transcriptome sequencing data from the Sequence Read Archive (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/) with accession number SRP06489424 and single-cell RNA-seq data from GEO database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) with accession number GSE160269)25 were revisited. The DOI number for RNA-seq data from EZH2 knockdown in KYSE150 cell line is 10.57760/sciencedb.16315 (Science database bank, https://www.scidb.cn/).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval statement and patient consent statement

The collected human tumor tissue samples were approved by the Ethical Committee of cancer Hospital of Shantou university medical college and the Medical College of Shantou University, (2024019) and all patients have signed informed consent forms. Animal care guidelines approved by the Animal Policy and Welfare Committee of Shantou University Medical College (SUMCSY2024-003) were followed while animal experiments were conducted.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Chun-Yan Zhu, Tian-Tian Zhai, Meng Su, Hong-Chao Pan, Qian Tang, Bao-Hua Huang.

Contributor Information

Tian-Tian Zhai, Email: tiantianzhai@qq.com.

Si-Qi Qiu, Email: s_patrick@163.com.

Feng Pan, Email: panfengbio@126.com.

Guo-Wei Huang, Email: huangguowei00@163.com.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-024-07341-9.

References

- 1.Liu, Y. T. & Sun, Z. J. Turning cold tumors into hot tumors by improving T-cell infiltration. Theranostics11, 5365–5386 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang, D. et al. Targeting regulator of G protein signaling 1 in tumor-specific T cells enhances their trafficking to breast cancer. Nat. Immunol.22, 865–879 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fridman, W. H., Pagès, F., Sautès-Fridman, C. & Galon, J. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat. Rev. Cancer12, 298–306 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuwano, A. et al. Tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells as a biomarker for chemotherapy efficacy in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol. Lett.25, 259 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu, S. et al. miR-424(322) reverses chemoresistance via T-cell immune response activation by blocking the PD-L1 immune checkpoint. Nat. Commun.7, 11406 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hannani, D. et al. Contribution of humoral immune responses to the antitumor effects mediated by anthracyclines. Cell Death Differ.21, 50–58 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackaman, C., Majewski, D., Fox, S. A., Nowak, A. K. & Nelson, D. J. Chemotherapy broadens the range of tumor antigens seen by cytotoxic CD8(+) T cells in vivo. Cancer Immunol. Immunother.61, 2343–2356 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta, A. et al. Radiotherapy promotes tumor-specific effector CD8+ T cells via dendritic cell activation. J. Immunol.189, 558–566 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liang, H. et al. Radiation-induced equilibrium is a balance between tumor cell proliferation and T cell-mediated killing. J. Immunol.190, 5874–5881 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park, S. et al. The therapeutic effect of anti-HER2/neu antibody depends on both innate and adaptive immunity. Cancer Cell18, 160–170 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stagg, J. et al. Anti-ErbB-2 mAb therapy requires type I and II interferons and synergizes with anti-PD-1 or anti-CD137 mAb therapy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA108, 7142–7147 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tumeh, P. C. et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature515, 568–571 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.71, 209–249 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li, R., Huang, B., Tian, H. & Sun, Z. Immune evasion in esophageal squamous cell cancer: From the perspective of tumor microenvironment. Front Oncol.12, 1096717 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou, X., Ren, T., Zan, H., Hua, C. & Guo, X. Novel immune checkpoints in esophageal cancer: from biomarkers to therapeutic targets. Front Immunol.13, 864202 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang W., Green M., Liu J. R., Lawrence T., Zou W. CD8+ T Cells in Immunotherapy, Radiotherapy, and Chemotherapy; In Oncoimmunology. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 23–39. 2018.

- 17.He, J. Z. et al. Spatial analysis of stromal signatures identifies invasive front carcinoma-associated fibroblasts as suppressors of anti-tumor immune response in esophageal cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 42, 136 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yin, J. et al. Neoadjuvant adebrelimab in locally advanced resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a phase 1b trial. Nat. Med.29, 2068–2078 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morel, K. L. et al. EZH2 inhibition activates a dsRNA-STING-interferon stress axis that potentiates response to PD-1 checkpoint blockade in prostate cancer. Nat. Cancer2, 444–456 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan, D. et al. A major chromatin regulator determines resistance of tumor cells to T cell-mediated killing. Science359, 770–775 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagarsheth, N. et al. PRC2 epigenetically silences Th1-type chemokines to suppress effector T-cell trafficking in colon cancer. Cancer Res.76, 275–282 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dangaj, D. et al. Cooperation between constitutive and inducible chemokines enables T cell engraftment and immune attack in solid tumors. Cancer Cell35, 885–900.e10 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu, W. et al. Large-scale and high-resolution mass spectrometry-based proteomics profiling defines molecular subtypes of esophageal cancer for therapeutic targeting. Nat. Commun.12, 4961 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li, C. Q. et al. Integrative analyses of transcriptome sequencing identify novel functional lncRNAs in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncogenesis6, e297 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang, X. et al. Dissecting esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma ecosystem by single-cell transcriptomic analysis. Nat. Commun.12, 5291 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu, J. Y. et al. CTL- vs Treg lymphocyte-attracting chemokines, CCL4 and CCL20, are strong reciprocal predictive markers for survival of patients with oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer113, 747–755 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, Y. et al. CXCL13-mediated recruitment of intrahepatic CXCR5+ CD8+ T cells favors viral control in chronic HBV infection. J. Hepatol.72, 420–430 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peng, D. et al. Epigenetic silencing of TH1-type chemokines shapes tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nature527, 249–253 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ding, Q. et al. CXCL9: evidence and contradictions for its role in tumor progression. Cancer Med.5, 3246–3259 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reschke, R. & Gajewski, T. F. CXCL9 and CXCL10 bring the heat to tumors. Sci. Immunol.7, eabq6509 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Winde, C. M., Munday, C. & Acton, S. E. Molecular mechanisms of dendritic cell migration in immunity and cancer. Med. Microbiol. Immunol.209, 515–529 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsumura, F. et al. Investigation of Fascin1, a marker of mature Dendritic cells, reveals a new role for IL-6 signaling in CCR7-Mediated chemotaxis. J. Immunol.207, 938–949 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li, Y. L., Zhao, H. & Ren, X. B. Relationship of VEGF/VEGFR with immune and cancer cells: staggering or forward? Cancer Biol. Med.13, 206–214 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee, W. S., Yang, H., Chon, H. J. & Kim, C. Combination of anti-angiogenic therapy and immune checkpoint blockade normalizes vascular-immune crosstalk to potentiate cancer immunity. Exp. Mol. Med. 52, 1475–1485 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fainaru, O. et al. TGFbeta-dependent gene expression profile during maturation of dendritic cells. Genes Immun.8, 239–244 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Su, Y. et al. HIF-1α mediates immunosuppression and chemoresistance in colorectal cancer by inhibiting CXCL9, -10 and -11. Biomed. Pharmacother.173, 116427 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spranger, S., Dai, D., Horton, B. & Gajewski, T. F. Tumor-residing Batf3 dendritic cells are required for effector T cell trafficking and adoptive T cell therapy. Cancer Cell31, 711–723.e4 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krzyszczyk, P. et al. The growing role of precision and personalized medicine for cancer treatment. Technol. (Singap. World Sci.)6, 79–100 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoy, S. M. Tazemetostat: first approval. Drugs80, 513–521 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pfirschke, C. et al. Immunogenic chemotherapy sensitizes tumors to checkpoint blockade therapy. Immunity44, 343–354 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Most, R. G. et al. Cyclophosphamide chemotherapy sensitizes tumor cells to TRAIL-dependent CD8 T cell-mediated immune attack resulting in suppression of tumor growth. PLoS One4, e6982 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen, J. et al. EZH2 mediated metabolic rewiring promotes tumor growth independently of histone methyltransferase activity in ovarian cancer. Mol. Cancer22, 85 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang, J. et al. EZH2 noncanonically binds cMyc and p300 through a cryptic transactivation domain to mediate gene activation and promote oncogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol.24, 384–399 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiao, L. et al. A partially disordered region connects gene repression and activation functions of EZH2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA117, 16992–17002 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuan, J. et al. Ezh2 competes with p53 to license lncRNA Neat1 transcription for inflammasome activation. Cell Death Differ.29, 2009–2023 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fitzgerald, A. A. et al. DPP inhibition alters the CXCR3 axis and enhances NK and CD8+ T cell infiltration to improve anti-PD1 efficacy in murine models of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer9, e002837 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ding, Q. et al. An alternatively spliced variant of CXCR3 mediates the metastasis of CD133+ liver cancer cells induced by CXCL9. Oncotarget7, 14405–14414 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tokunaga, R. et al. CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11/CXCR3 axis for immune activation - A target for novel cancer therapy. Cancer Treat. Rev.63, 40–47 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang, G. W. et al. LncRNA625 inhibits STAT1-mediated transactivation potential in esophageal cancer cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol.117, 105626 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The data in the present study is available within the published paper and its Supplementary file. The source data behind the graphs in the paper can be found in Supplementary Data 1 and the raw Western blot images are available in Supplementary Fig. S12. Transcriptome sequencing data from the Sequence Read Archive (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/) with accession number SRP06489424 and single-cell RNA-seq data from GEO database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) with accession number GSE160269)25 were revisited. The DOI number for RNA-seq data from EZH2 knockdown in KYSE150 cell line is 10.57760/sciencedb.16315 (Science database bank, https://www.scidb.cn/).