Abstract

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a leading cause of chronic liver disease and poses a substantial health burden with increasing incidence globally. NAFLD encompasses a spectrum extending from hepatic steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), with the possibility of progressing to cirrhosis or, in severe instances, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). NAFLD extends beyond simple metabolic disruption and involves multiple immune cell-mediated inflammatory processes. Integrins are a family of heterodimeric transmembrane cell adhesion receptors that regulate various aspects of NAFLD onset and progression, including hepatocellular steatosis, hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation and immune cell infiltration. In this review, we comprehensively summarize the involvement of integrins in NAFLD, as well as the downstream signal transduction mediated by these receptors. Furthermore, we present the latest clinical and preclinical findings on drugs that target integrins for steatosis, inflammation, fibrosis and NAFLD-related HCC treatment.

Keywords: integrins, NAFLD, NASH, NAFLD-related HCC, diagnostics and treatments

Introduction

Liver disease is a worldwide health care concern, contributing to more than two million deaths annually and accounting for 4% of all deaths worldwide [1]. At present, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the predominant etiology of chronic hepatitis in Western societies, with its prevalence rapidly increasing on a global scale [2]. Notably, this condition impacts a quarter of the global adult population. Over the past two decades, with rapid lifestyle changes, NAFLD has become the most common liver disease in China. The prevalence of NAFLD has increased from 23.8% to 29.0%; however, NAFLD has not received sufficient attention [3]. Over the past 30 years, the total number of deaths among NAFLD patients worldwide has doubled. The overall percentage of deaths attributed to NAFLD-related causes has increased from 0.10% to 0.17% [1]. Owing to continued high rates of adult obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus, coupled with an aging population, the total NAFLD population is forecasted to increase by 18.3% in the U.S., whereas the prevalence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) cases is expected to increase by 56% by 2030 [ 4, 5]. Currently, NAFL is defined as a catch-all term that encompasses a variety of disorders characterized by steatosis affecting a minimum of 5% of hepatocytes, combined with metabolic risk factors (such as type 2 diabetes and obesity). This definition excludes heavy alcohol usage-induced hepatitis or other chronic liver diseases. Furthermore, NASH is characterized by hepatic damage, including hepatocyte ballooning degeneration, diffuse lobular inflammation, and fibrosis [6]. Up to 15% of individuals with NAFLD progress to NASH, the more severe form of the disease. Whereas simple steatosis is often considered a “benign” condition, individuals with NASH face the potential for progression to fibrosis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and have an elevated risk of liver-related mortality. In addition, HCC may develop in individuals with NAFLD without cirrhosis, termed NAFLD-HCC [7].

Integrins are α/β heterodimeric cell adhesion molecules, mediating cell-cell, cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) and cell-pathogen interactions and transmit signals bidirectionally across the plasma membrane [8]. In vertebrates, 18 α subunits and 8 β subunits exist, which combine into 24 types of integrins that are broadly distributed across numerous organs and tissues ( Figure 1). Integrins, as type I transmembrane proteins, control cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesion, thereby impacting a variety of cellular functions, including migration, proliferation, wound repair, and other cellular activities [9]. In NAFLD, integrins serve as the primary mechanism by which cells in the liver sense their extracellular environment, such as accumulated lipids that trigger the “first hit” in NAFLD, which involves insulin resistance (IR) and hepatic steatosis [10]. Liver tissue eventually undergoes lipid peroxidation, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, oxidative stress, inflammatory damage, and other pathological alterations, contributing to the development of the “multiple-hit” scenario [11]. During NAFLD-induced fibrogenesis, integrins mediate diverse cell-matrix and cell-cell interactions. In NASH-related HCC, which progresses annually [12], integrins are typically dysregulated and are involved in nearly every stage of cancer progression, including epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), angiogenesis, cell proliferation, adhesion, and invasion [13]. Moreover, integrins are considered to influence multiple components within the tumor microenvironment of HCC, such as lymphocyte activation, migration, and extravasation.

Figure 1 .

Integrin family and classification

Twenty four integrins consist of 18 α subunits and 8 β subunits, which can be classified into RGD-binding integrins, leukocyte cell-adhesion integrins, collagen-binding integrins, and laminin-binding integrins.

Given the lack of Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medications for the treatment of NAFLD, the pharmacological interventions available for NAFLD are currently restricted. NAFLD and NASH are growing worldwide health concerns and significant unmet medical requirements [14]. The redundancy of integrin functions and their distinct roles at different stages of NAFLD highlight the considerable therapeutic potential of these molecules. This review focuses on the aberrant expression, activation, and signaling of integrins in both liver parenchymal and nonparenchymal cells, providing a summary of current findings regarding the involvement of integrins in NAFLD. Furthermore, we summarize the present state and treatment approaches of anti-integrin medications in both preclinical and clinical practice, encompassing a broad spectrum from NAFLD to HCC.

The Structure of Integrins

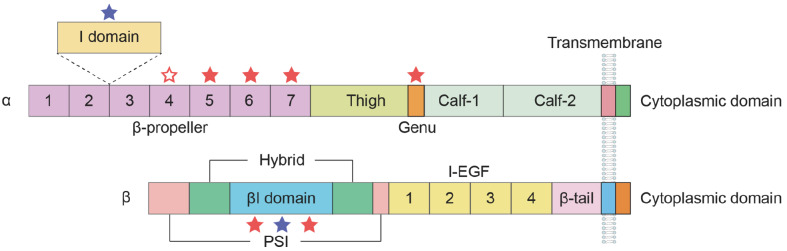

Integrins are α/β heterodimeric glycoprotein receptors [ 15, 16]. The α subunit comprises a seven-bladed β-propeller linked to a thigh, a calf-1 and a calf-2 domain, creating the leg structure that provides support for the integrin head. Seven repetitive motifs constitute the shared structure among various α subunits within their extracellular domains, developing a seven-bladed propeller structure on the upper surface. The ectodomain of the β subunit is composed of seven domains with intricate domain insertions: a plexin-semaphorin-integrin (PSI) domain, a βI domain inserted in the hybrid domain, four cysteine-rich epidermal growth factor (EGF) modules, and a β-tail domain (βTD) domain [17]. Integrins can be classified into two subfamilies on the basis of the presence of the αI domain. The αI domain, also known as the αA domain, is present in nine of the integrin α subunits (α1, α2, α10, α11, αD, αE, αX, αM and αL). This domain is inserted between blades two and three of the β-propeller structure. In integrins containing αI, the α head consists of β-propeller and αI domains, whereas in integrins lacking αI, a single β-propeller forms the α head [18]. αI domain-containing integrins bind to ligands via the αI domain [19]. The metal ion-dependent adhesion site (MIDAS), located on the top surface of the αI domain, is essential for the interaction between ligands and integrins. The βI domain shares a similar Rossmann fold with the αI domain, featuring a central six-stranded β-sheet surrounded by eight helices. In αI-less integrins, the MIDAS site in the βI domain mediates ligand binding ( Figure 2).

Figure 2 .

Representation of the structure of the integrin α and β subunits

Integrins are composed of α and β subunits, forming heterodimeric transmembrane glycoproteins. The α-chain consists of four or five extracellular domains: a seven-bladed β-propeller, a thigh, and two calf domains. Nine of the 18 integrin α chains contain an αI domain. The β subunit comprises seven domains with flexible and complex interconnections. The red and blue asterisks denote Ca2+- and Mg2+-binding sites, respectively. The hollow asterisk denotes the Ca2+-binding site in the fourth repeat of the β-propeller domain in certain α subunits.

Typically, integrins bind to their ligands by recognizing short, acidic peptide motifs (such as RGD and LDV), which are conserved tripeptide sequences. To date, two β1 integrins (α5 and α8), all five αV integrins, and αIIbβ3 are capable of binding to the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) sequence. This tripeptide is present in vitronectin, fibronectin, osteopontin, fibrinogen, collagen, thrombospondin, and von Willebrand factor [20]. Integrins αEβ7, α4β7, α4β1, and α9β1 bind to the specific Leu/Ile-Asp/Glu-Val/Ser/Thr (LDV) motif. The binding sites within the ligands of β2 integrins are structurally similar to the LDV motif [21]. Additionally, certain integrins are also capable of identifying the triple-helical GFOGER sequence. Notably, integrin αVβ3 is highly expressed in activated HSCs and promotes the survival and proliferation of HSCs during liver fibrosis. With the activation of HSCs, integrin αVβ3 expressed on HSCs binds to the RGD motif in various ECM components [22].

Activation and Signal Transmission of Integrins

Integrin activation is tightly regulated and is essential for cellular functions. The activation of integrins occurs through intricate signaling mechanisms both inside and outside the cells, leading to conformational changes in the integrin molecules. These changes expose the ligand-binding site in integrins, allowing them to interact with specific ligands present in the ECM or on the surface of neighboring cells.

Integrin activation involves intricate and reversible conformational changes within these transmembrane receptors. In the low-affinity state, integrins maintain a bent V-shaped conformation, wherein the head is positioned in the membrane-proximal regions of the legs. This conformation is sustained by the α/β salt bridge in the inner membrane region and helix packing of the transmembrane region. Upon activation, the head of the integrin extends, exposing the ligand-binding site, while the intracellular tails of the integrin separate [23]. Integrins are capable of adopting at least three primary distinct conformational states, each with different affinities for ligands: the low-affinity “bent” conformation, the intermediate-affinity “extended conformation with a closed headpiece”, and the high-affinity “extended conformation with an open headpiece” [24]. The delicate balance between these conformations has a substantial effect on controlling both the affinities for cell adhesion and the intensity of communication. Integrins can initiate “inside-out” and “outside-in” bidirectional signaling, rapidly resulting in global conformational rearrangement. Within the “inside-out” signaling pathway, intracellular activators such as talin or kindlin attach to the cytoplasmic tail of integrin β subunits [25]. This interaction triggers integrins to undergo conformational changes from a low-affinity bent shape to a high-affinity extended conformation, which recruits multivalent protein complexes that cluster together and strengthen their affinity for ligands. Consequently, this biological process facilitates essential cellular activities, such as cell adhesion, cell migration, ECM assembly and remodeling. In contrast, in “outside-in” signaling, integrin receptors engage with external ligands, such as ECM components, growth factor receptors (GFRs), urokinase plasminogen activator receptors, and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) receptors [26]. Binding of these ligands to integrin extracellular domains leads to integrin clustering and the transmission of signals into the cellular interior. This signaling cascade subsequently instigates alterations in cell polarity, cytoskeletal structure, and gene transcription ( Figure 3).

Figure 3 .

Activation and signaling of integrins

Integrins can adopt at least three distinct conformational states, each with varying affinities for ligands: the low-affinity “bent” conformation, the intermediate-affinity “extended conformation with closed headpiece”, and the high-affinity “extended conformation with open headpiece”. Integrins mediate cell signaling transduction through two mechanisms, known as “inside-out” signaling and “outside-in” signaling. In the “inside-out” signaling pathway, intracellular signals induce conformational changes in integrins, altering their ligand-binding affinity. Conversely, in the “outside-in” signaling pathway, engagement with extracellular ligands triggers conformational changes in integrins, transmitting signals into the cell and initiating downstream signaling cascades.

Integrins Guide the Trafficking of Immune Cells to the Liver

The endothelium acts as a barrier, separating circulating immune cells from inflamed tissues. Integrins are important in the process of immune cell trafficking, orchestrating a complex adhesion cascade that encompasses tethering and rolling of immune cells along the walls of high endothelial venules, chemokine-induced activation, firm arrest, and transendothelial migration [27]. Initially, immune cells undergo tethering and rolling, which is controlled by the interaction of selectins with their respective ligands. Leukocyte-expressed L-selectin (also known as CD62L) mediates tethering and rolling through recognition of its counterreceptor (peripheral node addressin, PNAd) on high endothelial venules. This step is reversible unless firm adhesion occurs [28]. The activation induced by chemokines is a crucial step in the transition from rolling to firm arrest. Chemokines rapidly activate integrins via an “inside-out” signaling network that controls the connection between the cytoplasmic domains of integrins and intracellular effector proteins ( e.g., talin or kindlin) during this process. Upon the binding of effector proteins, integrins transition from an inactive bent conformation to their active form, which is distinguished by its extended form and strong affinity for ligands [ 29, 30]. Specific endothelial ligands, including intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1/2, vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1, and mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule (MAdCAM)-1, interact with activated leukocyte integrins, primarily α4β1, α4β7, αLβ2, αMβ2, αXβ2, and αDβ2, to mediate the firm adhesion of immune cells. Platelet and endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM)-1 and junctional adhesion molecule (JAM)-A/B/C regulate the final step of transmigration through interactions with leukocyte lymphocyte function-associated antigen (LFA)-1 (αLβ2), very late antigen (VLA)-4 (α4β1) and macrophage-1 antigen (Mac-1) (αMβ2) [31].

Integrin-mediated adhesion plays a crucial role in guiding lymphocyte localization toward the liver. The binding of VCAM-1 to VLA-4 is crucial for localizing TH1-type CD4 + T cells [32] and activated CD8 + T cells [33] in the liver. These adhesion molecules are involved in the antigen-independent homing of T cells to the liver, whereas ICAM-1 assumes a more critical role in antigen recognition by T cells. Effector CD8 + T cells traveling through the mouse liver initially halt in sinusoids, not postcapillary venules, independent of antigen recognition and a variety of molecules that are variably involved in leukocyte trafficking to different organs [34]. Conversely, the favored method for halting effector CD8 + T cells circulating in liver sinusoids involves docking onto platelets that have already bound to sinusoidal hyaluronan via CD44 [35]. Additional adhesion molecules are expressed in the hepatic vasculature during inflammation. MAdCAM-1 increases significantly in response to both IL-1β and TNF-α. Hepatic MAdCAM-1 interacts with integrin α4β7, which is typically expressed on gut-homing lymphocytes [36]. Furthermore, endothelial activation leads to increased expressions of various adhesion molecules, including ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and L-selectin [37]. Both VAP-1 and ICAM-1 play a role in Treg cell adhesion and transmigration [38].

The Role of Integrins in the Development of Simple Steatosis in NAFLD

Integrins and cell adhesion molecules regulate a multitude of physiological and pathological processes by mediating the connections between cells and their external environment. Accumulating evidence highlights the crucial role of integrin-mediated signaling in various chronic and acute noncancerous diseases, with a particular emphasis on liver-related conditions. Integrins play pivotal roles in immune cells for trafficking, activation, and function to induce effective immune responses. During the progression from NAFLD to cirrhosis, integrins selectively manipulate specific subsets of immune cells to mediate pro- or anti-inflammatory pathological scenarios in the liver [ 39, 40]. Notably, integrins serve essential biological functions in hepatic nonimmune cells, mediating cell-matrix and cell-cell interactions [41].

According to the most widespread and prevailing model of the “multiple-hit hypothesis”, the “first hit” involves liver lipid accumulation and insulin resistance [ 42, 43]. Hepatic lipid accumulation is associated with liver damage and an increase in the production of ECM [44]. α1β1, a collagen-binding integrin located on hepatocytes, provides protection against diet-induced hepatic insulin resistance while simultaneously promoting lipid accumulation in the liver [45]. Elevated circulating levels of free fatty acids (FFAs) strongly correlate with hepatic lipid accumulation in individuals with NAFLD. Experimental evidence has confirmed the involvement of integrin α5β1 in FFA-induced intracellular lipid accumulation, activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, and proptosis in hepatocytes [46]. In contrast, hepatocyte-specific deletion of the integrin β1 subunit has been reported to alleviate hepatic insulin resistance in diet-induced obese mice, while liver triglyceride levels remain elevated ( Figure 4) [47].

Figure 4 .

Roles of integrins in hepatocyte functions in NAFLD

Hepatic integrin α1β1 induces the phosphorylation and subsequent activation of IRS1 and AKT, promoting liver insulin action and preventing diet-induced liver insulin resistance. Integrin α5β1 activates of NLRP3 inflammasome and pyroptosis in hepatocytes during NAFLD.

Integrins in the Development of NASH

Elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress and adipokines are associated with the “second hit” of NAFLD, thereby driving the progression of the disease to hepatic steatosis and ultimately cirrhosis [48]. Triggers of hepatic inflammation contribute to the transition from NAFLD (isolated steatosis) to NASH [49]. Integrin and chemokine receptor pairs drive myeloid cell infiltration and residence in damaged tissues, thus creating a more intricate immune microenvironment [50]. Both recruited integrin αM + macrophages [51] and resident integrin αX + macrophages [52] are key factors in the development of simple steatosis to steatohepatitis. Type 1 conventional dendritic cells (cDC1s) have been identified as important drivers of liver pathology in NASH [53]. Integrin expression influences the heterogeneity of cDC1s. Integrin αE + cDC1s represent an anti-inflammatory subtype that protects the liver from metabolic damage during the development of steatohepatitis in mice [54].

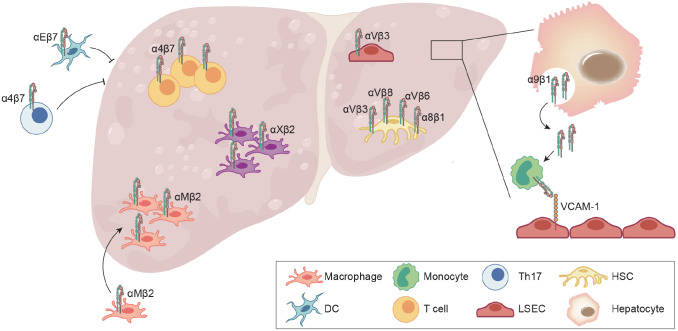

The spectrum of hepatic lesions linked to NAFLD encompasses the infiltration and activation of adaptive immune cells, including T and B lymphocytes [55]. Evidence of ectopic expression of the gut-homing adhesion molecule integrin α4β7 was demonstrated in the hepatic T cells of NASH patients [56]. Although hepatic infiltrating β7-expressing T cells exhibit an aggravated proinflammatory phenotype, the role of integrin β7 in liver lipid accumulation and fibrotic pathology remains controversial. Research has shown that integrin β7 deficiency protects against atherosclerosis [57] and obesity-related insulin resistance [58], attenuating hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in NASH [39]. In contrast, gut-homing β7 + TH17 cells may be utilized to alleviate metabolic disorders and steatosis in obese individuals [59].

αV integrins regulate the activity of TGF-β, the master regulator of fibrosis, making them therapeutic targets. The hepatic sinusoid dominates lipid metabolism and tissue fibrosis. Laminin (LN), an integrin ECM ligand, is excessively deposited in gaps between liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) in patients with NAFLD, reducing endothelial cell permeability and leading to sinusoidal capillarization. Damaged LSECs result in the expression of integrin αVβ3, subsequently inducing the expression of LN [60]. In addition, αVβ3 has been proposed as a central mediator of fibrosis in multiple organs and is highly expressed on activated hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) [61]. Integrin αVβ6 is markedly upregulated in hepatitis fibrosis, cirrhosis, and other liver injuries via the activation of TGF-β1 signaling in HSCs [62]. The integrins αVβ3 [ 63– 65], αVβ6 and αVβ8 [66] may have the potential to serve as markers and therapeutic targets for liver fibrosis. Unfortunately, no αV integrin inhibitors have reached the clinical market. Integrin α8β1 is selectively expressed in HSCs and is elevated in specimens from patients with liver fibrosis [67]. The administration of an anti-integrin α8 neutralizing monoclonal antibody improved pathology and fibrosis in cytotoxic (CCl 4 treatment), cholestatic fibrosis and NASH-associated models [68].

Recently, emerging evidence has suggested that the hepatic microenvironment consists of various types of cells and involves intercellular crosstalk [69]. The pivotal role of integrins in cell-cell communication makes them promising therapeutic targets. Guo et al. [70] reported that integrin α9β1 established communication among hepatocytes, monocytes and LSECs. Extracellular vesicles enriched with integrin α9β1, which are derived from lipotoxic hepatocytes, mediate monocyte adhesion to LSECs ( Figure 5). In a separate study, the loss of integrin β1 in hepatocytes induced liver fibrosis through an increase in TGF-β level [71].

Figure 5 .

The role of integrins in liver fibrosis in NASH

Recruited αM+ macrophages, αX+ macrophages, α4β7+ T cells are accumulated in NASH liver, which induce liver inflammation and fibrosis. αE+ cDC1 and β7+ TH17 are employed to reduce metabolic disorders and steatosis in obese mice. Activated integrin α9β1 is endocytosed by hepatocytes and secreted in the form of extracellular vesicles (EVs), which are further captured by monocytes. Captured integrin α9β1 mediates monocyte adhesion to LSECs by binding to VCAM-1, which accelerates liver fibrosis. αV integrins are the regulators of fibrosis in HSCs and LSECs, making them therapeutic targets in NASH. Additionally, integrin α8β1 promotes liver fibrosis by activating TGF-β in HSCs.

Integrins and NAFLD-related HCC

NAFLD has emerged as a major risk factor for HCC and is correlated with elevated expression of integrin β1 and activation of its downstream phospho-FAK. Blocking the integrin β1/FAK pathway in liver cancer cells alleviates NAFLD-related HCC in animal models [72]. Among the β1 integrins, the expression of integrin α5β1 is highest in HCC tumors. Fibronectin in fibroblasts is remodeled by upregulated integrin α5β1 in cancer cells, promoting tumor growth and angiogenesis [73]. In addition to β1 integrins, which are crucial for the progression of NAFLD, β4 integrins and other integrins have also been reported to play significant roles in the development of liver cancer [ 13, 74]. For example, research has shown that integrin α6β4 is overexpressed in HCC and promotes metastasis, invasion and the EMT process by conferring anchorage independence through EGFR-dependent FAK/AKT activation [ 75, 76]. The function of β3 integrins in liver cancer remains controversial. Integrin αVβ3 has been reported to facilitate the invasion and metastasis of HCC cells and is overexpressed in HCC tissues [ 77, 78]. However, β3 integrins and their ligands were downregulated in 60% of the HCC samples, as reported by Wu et al. [79], suggesting a potential therapeutic approach to restrain the aggressive growth of liver cancer.

Integrin-targeting Diagnostics and Treatments

The acknowledged role of integrins in tumor development has rendered them promising targets for cancer therapy in recent years. Various integrin antagonists, such as antibodies and synthetic peptides, have demonstrated their efficacy in inhibiting tumor progression in preclinical and clinical research.

Application of integrins in NAFLD-related diseases

Molecular imaging is a vital component of precision medicine, contributing to early diagnosis, staging, tailored treatment, prognostic evaluation, prognostic evaluation, and monitoring of therapeutic efficacy for life-threatening diseases such as cancer. Polypeptides containing RGD sequences have been used as probes in SPECT/PETCT imaging agents in clinical trials because they primarily target integrin αV, which is overexpressed in tumor neovascular endothelial cells and numerous tumor cells ( Table 1) [17]. As early as 2004, Sipos et al. [80] reported the overexpression of integrin αV in gastrointestinal pancreatic cancer. Integrin αVβ6 is strongly expressed in hilar cholangiocarcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma but not in HCC [81], potentially serving as a prospective immunohistochemical marker with specificity in the differential diagnosis of primary liver cancers. In contrast, integrin αVβ3 has been reported to be overexpressed in carcinoma tissue and to mediate the invasion and metastasis of HCC cells [77]. Zheng et al. [82] investigated the feasibility of 99mTc-HYNIC-PEG4-E[PEG4-c(RGDfK)]2 for the detection of HCC in tumor-bearing mice. Integrin αVβ3 has garnered much attention in the clinical diagnosis of solid tumors, and improving its accuracy in the diagnosis of liver cancer is extremely important. In addition, Lin et al. [83] designed an optimized integrin α6-targeted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) probe called DOTA(Gd)-ANADYWR for mouse HCC MRI. However, whether this integrin can become a diagnostic target in humans remains to be verified.

Table 1 The use of integrins in diagnostic imaging

|

Disease |

Targeted integrin |

Source |

Drug name |

Diagnosis method |

Time (first posted) |

Phase |

|

Malignant solid tumors |

αVβ3 |

CTR20222903 |

68Ga-HX01 |

PET/CT |

2022-11-10 |

Phase I |

|

Malignant solid tumors |

αVβ6 |

ChiCTR2200066067/NCT05835570 |

68Ga-Trivehexin |

PET/CT |

2022-11-23 |

Unknown |

|

Solid tumors |

αVβ3/αVβ5 |

68Ga-FF58 |

PET/CT |

2021-10-14 |

Phase I |

|

|

Solid tumors |

αVβ6 |

[ 18F]-FBA-A20FMDV2 |

PET/CT |

2016-03 |

Unknown |

|

|

Steatohepatitis |

αVβ6 |

[ 18F]-FBA-A20FMDV2 |

PET/CT |

2018-04-10 |

Unknown |

Animal experiments have shown that [ 18F]-F-FPP-RGD 2 [84] and [ 18F]-Alfatide [85] appear to be promising PET imaging radiotracers for monitoring hepatic integrin αV protein levels and hepatic function in liver fibrotic pathology. A clinical trial involved the utilization of [ 18F]-FBA-A20FMDV2 PET to quantify integrin αVβ6 in healthy and fatty liver tissues (NCT04063826). The aforementioned research laid the groundwork for a succession of ongoing clinical applications that utilize [ 18F]-FBA-A20FMDV2 as a radioligand in PET/CT studies to identify integrin αVβ6. As a result, [ 18F]-FBA-A20FMDV2 can serve as a reversible, specific, and selective PET ligand for αV integrins, as well as an imaging tool applicable to human subjects for monitoring the clinical efficacy of novel therapies in incurable and life-limiting diseases such as liver fibrosis.

Integrins as targets for inflammatory disease therapeutics

Certain specific leukocyte integrins are activated by inflammatory cytokines during inflammation, thereby encouraging cellular adherence to their receptors and enabling phagocytosis and cytotoxic killing. Many integrins have been designated as potential therapeutic targets for small compounds, peptides, and/or monoclonal antibodies. Currently, therapeutic interventions targeting α4 integrins for the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS), as well as β7 integrins (α4β7 and αEβ7 integrins), for the management of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have been implemented. Many large-scale clinical trials have been conducted to assess the efficacy of etrolizumab (anti-β7) in patients with IBD. Etrolizumab inhibits leukocyte gut homing and retention by blocking α4β7 and αEβ7 integrins, respectively [86]. The efficacy of other anti-integrin β7 therapies in the treatment of colitis, such as abrilumab (anti-α4β7), PN-943 (orally administered and gut-restricted α4β7 antagonist peptide) and AJM300 (orally active small molecule inhibitor of α4), is not known. In patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D), α4β7 integrin assists immune cells in trafficking from the periphery to the target tissue, leading to destruction of islet cells [87]. Vedolizumab directly blocks integrin α4β7 on circulating immune cells, preventing their egress from the blood and relieving T1D. Clinical trials have evaluated the immune effects of vedolizumab plus anti-TNF pretreatment in T1D, which blocks TNF-α signaling and its related expression of the α4β7 ligand MAdCAM-1 in pancreatic endothelial cells (NCT05281614).

The integrins αVβ3 and α5β1 are involved in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). α5β1 and αVβ3 are highly expressed in fibroblasts during inflammation, which is concomitant with an increase in the release of proinflammatory mediators, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and osteoclast activators, which are receptor activators of NF-κB ligands. The adhesion of lymphocytes expressing α4β1 or α5β1 to ECM ligands induces the expression of inflammatory factors that promote the proliferation and survival of synoviocytes and chondrocytes, which results in hyperplasia of synovial tissue and destruction of bone and cartilage [88]. A small-molecule αVβ3 antagonist has been reported to be efficacious in a rabbit model of RA [89]. Etaracizumab is recognized as a humanized anti-αVβ3 monoclonal antibody and has entered phase II clinical trials as a medication for RA treatment. Nevertheless, the phase II trial for the treatment of RA in humans has been terminated as a result of severe observed adverse effects, including myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation and thromboembolic events. Clinical trials targeting αVβ3 with other antibodies or small molecules for RA are currently underway ( Table 2) [88].

Table 2 Integrin-targeting therapies in clinical trials of inflammatory diseases

|

Disease |

Targeted integrin |

Source |

Drug name |

Drug type |

Time (first posted) |

Phase |

|

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease |

α4β7 |

BLA761133 |

Vedolizumab |

Monoclonal antibody |

2014-05 |

FDA approved |

|

Type 1 diabetes |

α4β7 |

Vedolizumab |

Monoclonal antibody |

2022-09-21 |

Phase I |

|

|

Ulcerative colitis |

α4β7 |

PN-943 |

Peptide |

2020-08-05 |

Phase II |

|

|

Multiple sclerosis and Crohn’s disease |

α4 |

BLA125104 |

Natalizumab |

Monoclonal antibody |

2004-09 |

FDA approved |

|

Psoriasis |

αVβ3 |

MEDI-522 |

Monoclonal antibody |

2003-12 |

Phase II |

|

|

Rheumatoid arthritis |

αVβ3 |

MEDI-522 |

Monoclonal antibody |

2003-09 |

Phase II |

|

|

NASH and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis |

αvβ1, αvβ3 and αvβ6 |

IDL-2965 |

Small molecule |

2019-04-16 |

Phase I |

|

|

Osteoarthritis |

α10β1 |

XSTEM-OA |

Mesenchymal stem cells |

2022-06-22 |

Phase I/II |

While the majority of integrin therapeutic antagonists demonstrate better bioavailability during clinical trials focused on inflammatory diseases, their efficacy in treating NAFLD remains undetermined. Consequently, integrins, such as integrin α4β7, remain prospective therapeutic targets for the management of NAFLD, and further investigations need to be conducted in this regard.

Integrins as targets for liver cancer therapeutics

Numerous integrins contribute to cell-ECM and cell-cell interactions, which have also been linked to fibrosis, inflammation, thrombosis, and tumor metastasis. Since many solid tumors originate from epithelial cells, the integrins expressed by epithelial cells, such as α2β1, α3β1, α6β1, α6β4, and αVβ5, are typically preserved within the tumor. Although their primary function is to facilitate the adhesion of epithelial cells to the basement membrane, these integrins may also play a role in the migration, proliferation and survival of tumor cells. Notably, the levels of integrins α5β1, αVβ3 and αVβ6 are often negligible or undetectable in the majority of adult epithelia but can be highly upregulated in certain malignancies. Considering the extensive research on tumors, these integrins may emerge as promising targets for cancer therapy. Furthermore, certain integrin antagonists have been effectively utilized in the treatment of cancer in clinical settings.

A phase I clinical trial demonstrated the safety and tolerability of intetumumab, a protein that binds with high affinity to multiple αV integrins. Patients whose tumor cells expressed αVβ3 integrin exhibited a prolonged response to intetumumab, whereas those whose tumors expressed αVβ1 integrin only demonstrated a partial response [90]. Nonetheless, the development of this drug was halted during its phase II clinical study for the treatment of melanoma and prostate cancer. Volociximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody designed to specifically target α5β1 integrin and disrupt its interaction with fibronectin. In phase I and II clinical trials, this anti-α5β1 monoclonal antibody has been evaluated both as a single therapy and in combination with classical drugs such as carboplatin and paclitaxel to treat distinct tumor types, including metastatic melanoma and advanced non-small cell lung cancer. After six cycles of treatment, the preliminary findings indicated a median progression-free survival increase of 6.3 months and reduced concentrations of potential biomarkers associated with angiogenesis or metastasis [91].

Several recent studies have indicated that integrins are involved in cancer development. However, the efficacy of integrin-based therapy for liver cancer is limited to animal experiments. Observing the performance of these anti-integrin agents in HCC clinical trials and investigating how their efficacy might be optimized in conjunction with additional therapy options would be interesting ( Table 3).

Table 3 Clinical trials for the assessment of integrin-targeting therapeutics in liver cancer

|

Disease |

Targeted integrin |

Source |

Drug name |

Drug type |

Time (first posted) |

Phase |

|

Advanced non-hematologic malignancies |

α5β1 |

PF-04605412 |

Monoclonal antibody |

2009-09 |

Phase I |

|

|

Advanced solid tumors and glioblastoma multiforme |

αVβ6 |

EMD121974 |

Cyclic peptide |

2009-12 |

Phase I |

|

|

Pancreatic cancer and solid tumor malignancies |

αVβ3 |

ProAgio |

Protein drug |

2021-10-29 |

Phase I |

|

|

Advanced colorectal cancer |

αVβ3 |

MEDI-522 |

Monoclonal antibody |

2001-06 |

Phase I/II |

|

|

Refractory prostate cancer |

αV |

Intetumumab (CNTO 95) |

Monoclonal antibody |

2007-05 |

Phase II |

|

|

Melanoma |

αV |

Intetumumab (CNTO 95) |

Monoclonal antibody |

2005-05 |

Phase I/II |

|

|

Metastatic colorectal cancer |

αV |

Abituzumab (EMD525797) |

Monoclonal antibody |

2019-04 |

Phase II |

|

|

Metastatic melanoma |

α5β1 |

Volociximab (M200) |

Monoclonal antibody |

2004-12 |

Phase II |

Challenges and Prospects

The new generation of imaging agents that target integrins offers new promise for diagnosing liver fibrosis and solid tumors. Although αVβ3 is considered a promising diagnostic target for tumors and fibrosis, its expression levels remain nonnegligible in certain organs, leading to substantial background uptake and unwanted organ doses [92]. Therefore, αVβ3-targeted radiopharmaceuticals have not yet been developed for routine clinical diagnosis of cancer and fibrosis. Additionally, αVβ3 integrin has been found on other cells, such as macrophages [93]. Further work in this field is expected to expand the scope of integrin-targeted optical imaging, including improving optical probes and discovering new ligands targeting integrins.

Owing to the characteristic features and complex molecular mechanisms of integrins, progress in drug discovery targeting integrins has not been ideal. An important lesson from past integrin drug development efforts is that the success of integrin drug discovery depends on unmet clinical needs and a deep understanding of the fundamental mechanisms of cell adhesion. Currently, the mechanism of most antibody drugs, peptides or small molecule antagonists that target integrins lies in blocking the binding between biological ligands and integrins. Because integrins undergo significant conformational changes during activation, inhibitors that target the activation process have been proposed as drug targets [26]. Although conformer-specific inhibitors have been developed by the pharmaceutical industry, none have entered the market. This may be related to the limited specificity of these conformer-related inhibitors, as well as the unexpected systemic toxicity caused by the inappropriate binding of these antagonists inducing conformational changes in integrins. Additionally, integrin drugs that are administered orally are still under development or are undergoing clinical trials [94]. Factors contributing to the lack of oral small molecules that target integrins include mainly the polar pharmacophores of these molecules and the complex pharmacology of the target pathway. An in-depth understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms of NAFLD provides hope for the treatment of NAFLD-NASH. Integrin αV is considered a crucial target for treating fibrosis. The most advanced integrin-targeted therapy for NASH is the selective αvβ1 inhibitor PLN-1474 [26]. However, owing to strategic adjustments, Novartis AG terminated the collaboration and development of the integrin αVβ1 inhibitor PLN-1474 for NASH treatment in 2023. IDL-2965 is an oral integrin αV antagonist that has been investigated as a potential treatment for NASH. Unfortunately, owing to the challenges associated with the COVID-19 pandemic and newly emerging nonclinical data, the NCT03949530 study evaluating IDL-2965 was terminated prematurely [41].

Among the FDA-approved integrin drugs, natalizumab is used to treat MS and Crohn’s disease. Patients receiving natalizumab therapy experienced the unexpected development of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), leading to the withdrawal of this drug from the market in 2005. However, owing to its significant benefits, natalizumab returned to the market in 2006. Owing to the risk of PML associated with the use of natalizumab, vedolizumab has effectively replaced it in clinical practice for the treatment of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Moreover, on the basis of MAdCAM-1 expression level, potential new indications for vedolizumab include chronic liver diseases [95]. Comprehensive safety data from over 4000 patient-years of vedolizumab exposure in six clinical trials indicate good long-term tolerability and acceptable safety for patients receiving vedolizumab treatment [96].

In summary, the global incidence of NAFLD/NASH is increasing. However, the current lack of effective treatments for NASH persists, with several others ( e. g., elafibranor, seladelpar, emricasan, selonsertib and elobixibat) having already been deemed ineffective [97]. Consequently, there is an urgent imperative for the development of effective treatments to mitigate the increasing prevalence and mortality associated with NAFLD. According to reported findings, aberrant expression, activation, and signaling pathways, in alignment with the multifaceted functions of integrins, are involved in almost every stage of NAFLD development, including NAFLD, NASH, fibrosis, cirrhosis and HCC. The distinctive and intricate role of integrins could provide potential therapeutic targets for liver diseases. Animal models of NAFLD and NASH have demonstrated that inhibitors targeting HSC- and LSEC-expressing integrins, such as αVβ1 and αVβ6, can effectively attenuate lipid accumulation and fibrosis. Unfortunately, satisfactory outcomes have yet to materialize in clinical trials, underscoring the necessity for additional data derived from human disease samples. Cell adhesion plays a vital role in restricting the excessive activity of immune cells toward inflammatory tissues. Currently, integrin αM + macrophages, αE + dendritic cells, and α4β7 + T cells are reported to be involved in the progression of NAFLD. Although monoclonal antibodies have been utilized to prevent leukocyte adhesion, their practical implementation has frequently been unsatisfactory as a result of undesirable side effects [98]. We posit that sustained efforts to enhance our knowledge of the function of integrins in NAFLD will pave the way for the development of more innovative targeted approaches and usher in a renaissance in this area.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (Nos. 2020YFA0509003 and 2020YFA0509102 to J.C.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31830112, 32030024, 31900536, 32170769 to J.C., No. 32300633 to M.H., and No. 32200642 to S.C.), the Program of Shanghai Academic Research Leader (No. 19XD1404200 to J.C.), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2023M733487 to M.H. and No. 2020M671262 to S.W.), and the China Postdoctoral Innovative Talent Support Program (No. BX20190345 to S.W.). The authors gratefully acknowledge support of the SA-SIBS scholarship program.

References

- 1.Devarbhavi H, Asrani SK, Arab JP, Nartey YA, Pose E, Kamath PS. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J Hepatol. . 2023;79:516–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, Hardy T, Henry L, Eslam M, George J, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. . 2018;15:11–20. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou J, Zhou F, Wang W, Zhang XJ, Ji YX, Zhang P, She ZG, et al. Epidemiological features of NAFLD from 1999 to 2018 in China. J Hepatol. . 2020;71:1851–1864. doi: 10.1002/hep.31150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Estes C, Razavi H, Loomba R, Younossi Z, Sanyal AJ. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. J Hepatol. . 2018;67:123–133. doi: 10.1002/hep.29466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Estes C, Anstee QM, Arias-Loste MT, Bantel H, Bellentani S, Caballeria J, Colombo M, et al. Modeling NAFLD disease burden in China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States for the period 2016–2030. J Hepatol. . 2018;69:896–904. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo X, Yin X, Liu Z, Wang J. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) pathogenesis and natural products for prevention and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. . 2022;23:15489. doi: 10.3390/ijms232415489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Younes R, Bugianesi E. A spotlight on pathogenesis, interactions and novel therapeutic options in NAFLD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. . 2019;16:80–82. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luo BH, Springer TA. Integrin structures and conformational signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. . 2006;18:579–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yao Y, Liu H, Yuan L, Du X, Yang Y, Zhou K, Wu X, et al. Integrins are double-edged swords in pulmonary infectious diseases. Biomed Pharmacother. . 2022;153:113300. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basaranoglu M. From fatty liver to fibrosis: a tale of “second hit”. World J Gastroenterol. . 2013;19:1158. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i8.1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buzzetti E, Pinzani M, Tsochatzis EA. The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Metabolism. . 2016;65:1038–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong RJ, Cheung R, Ahmed A. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the most rapidly growing indication for liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the U.S. J Hepatol. . 2014;59:2188–2195. doi: 10.1002/hep.26986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao Q, Sun Z, Fang D. Integrins in human hepatocellular carcinoma tumorigenesis and therapy. Chin Med J. . 2023;136:253–268. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrison SA, Allen AM, Dubourg J, Noureddin M, Alkhouri N. Challenges and opportunities in NASH drug development. Nat Med. . 2023;29:562–573. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02242-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hynes RO. Integrins: a family of cell surface receptors. Cell. . 1987;48:549–554. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hynes RO. The emergence of integrins: a personal and historical perspective. Matrix Biol. . 2004;23:333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pang X, He X, Qiu Z, Zhang H, Xie R, Liu Z, Gu Y, et al. Targeting integrin pathways: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Sig Transduct Target Ther. . 2023;8:1. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01259-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang K, Chen JF. The regulation of integrin function by divalent cations. Cell Adh Migr. . 2012;6:20–29. doi: 10.4161/cam.18702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mezu-Ndubuisi OJ, Maheshwari A. The role of integrins in inflammation and angiogenesis. Pediatr Res. . 2021;89:1619–1626. doi: 10.1038/s41390-020-01177-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruoslahti E, Pierschbacher MD. New perspectives in cell adhesion: RGD and integrins. Science. . 1987;238:491–497. doi: 10.1126/science.2821619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Humphries JD, Byron A, Humphries MJ. Integrin ligands at a glance. J Cell Sci. . 2006;119:3901–3903. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang DB, Zhang C, Liu H, Cui Y, Li X, Zhang Z, Zhang Y. Molecular magnetic resonance imaging of activated hepatic stellate cells with ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide targeting integrin alphavbeta(3) for staging liver fibrosis in rat model. Int J Nanomedicine. . 2016;11:1097–1108. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S101366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo BH, Carman CV, Springer TA. Structural basis of integrin regulation and signaling. Annu Rev Immunol. . 2007;25:619–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nolte MA, Margadant C. Activation and suppression of hematopoietic integrins in hemostasis and immunity. Blood. . 2020;135:7–16. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019003336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye F, Kim C, Ginsberg MH. Molecular mechanism of inside-out integrin regulation. J Thromb Haemost. . 2011;9:20–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slack RJ, Macdonald SJF, Roper JA, Jenkins RG, Hatley RJD. Emerging therapeutic opportunities for integrin inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. . 2022;21:60–78. doi: 10.1038/s41573-021-00284-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Andrian UH, Mempel TR. Homing and cellular traffic in lymph nodes. Nat Rev Immunol. . 2003;3:867–878. doi: 10.1038/nri1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chae YK, Choi WM, Bae WH, Anker J, Davis AA, Agte S, Iams WT, et al. Overexpression of adhesion molecules and barrier molecules is associated with differential infiltration of immune cells in non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep. . 2018;8:1023. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19454-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky MI, Nourshargh S. Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat Rev Immunol. . 2007;7:678–689. doi: 10.1038/nri2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hogg N, Patzak I, Willenbrock F. The insider’s guide to leukocyte integrin signalling and function. Nat Rev Immunol. . 2011;11:416–426. doi: 10.1038/nri2986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin CD, Chen JF. Regulation of immune cell trafficking by febrile temperatures. Int J Hyperthermia. . 2019;36:17–21. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2019.1647357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bonder CS, Norman MU, Swain MG, Zbytnuik LD, Yamanouchi J, Santamaria P, Ajuebor M, et al. Rules of recruitment for Th1 and Th2 lymphocytes in inflamed liver: a role for alpha-4 integrin and vascular adhesion protein-1. Immunity. . 2005;23:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.John B, Crispe IN. Passive and active mechanisms trap activated CD8+ T cells in the liver. J Immunol. . 2004;172:5222–5229. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ficht X, Iannacone M. Immune surveillance of the liver by T cells. Sci Immunol. . 2020;5:eaba2351. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aba2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guidotti LG, Inverso D, Sironi L, Di Lucia P, Fioravanti J, Ganzer L, Fiocchi A, et al. Immunosurveillance of the liver by intravascular effector CD8+ T Cells. Cell. . 2015;161:486–500. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ando T, Langley RR, Wang Y, Jordan PA, Minagar A, Alexander JS, Jennings MH. Inflammatory cytokines induce MAdCAM-1 in murine hepatic endothelial cells and mediate alpha-4 beta-7 integrin dependent lymphocyte endothelial adhesion in vitro . BMC Physiol. . 2007;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crispe IN. Migration of lymphocytes into hepatic sinusoids. J Hepatol. . 2012;57:218–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shetty S, Weston CJ, Oo YH, Westerlund N, Stamataki Z, Youster J, Hubscher SG, et al. Common lymphatic endothelial and vascular endothelial receptor-1 mediates the transmigration of regulatory T cells across human hepatic sinusoidal endothelium. J Immunol. . 2011;186:4147–4155. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rai RP, Liu Y, Iyer SS, Liu S, Gupta B, Desai C, Kumar P, et al. Blocking integrin α4β7-mediated CD4 T cell recruitment to the intestine and liver protects mice from western diet-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. . 2020;73:1013–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang M, Han Y, Han C, Xu S, Bao Y, Chen Z, Gu Y, et al. The β2 integrin CD11b attenuates polyinosinic: polycytidylic acid-induced hepatitis by negatively regulating natural killer cell functions. J Hepatol. . 2009;50:1606–1616. doi: 10.1002/hep.23168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rahman SR, Roper JA, Grove JI, Aithal GP, Pun KT, Bennett AJ. Integrins as a drug target in liver fibrosis. Liver Int. . 2022;42:507–521. doi: 10.1111/liv.15157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fang YL, Chen H, Wang CL, Liang L. Pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children and adolescence: from “two hit theory” to “multiple hit model”. World J Gastroenterol. . 2018;24:2974–2983. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i27.2974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lim JS, Mietus-Snyder M, Valente A, Schwarz JM, Lustig RH. The role of fructose in the pathogenesis of NAFLD and the metabolic syndrome. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. . 2010;7:251–264. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Day CP, James OFW. Steatohepatitis: a tale of two “hits”? Gastroenterology. . 1998;114:842–845. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams AS, Kang L, Zheng J, Grueter C, Bracy DP, James FD, Pozzi A, et al. Integrin α1-null mice exhibit improved fatty liver when fed a high fat diet despite severe hepatic insulin resistance. J Biol Chem. . 2015;290:6546–6557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.615716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yao Q, Liu J, Cui Q, Jiang T, Xie X, Du X, Zhao Z, et al. CCN1/integrin α5β1 instigates free fatty acid-induced hepatocyte lipid accumulation and pyroptosis through NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nutrients. . 2022;14:3871. doi: 10.3390/nu14183871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trefts E, Ghoshal K, DO AV, Guerin A, Guan C, Bracy D, Lantier L, et al. 294-OR: hepatic integrin β1 subunit is required for liver insulin resistance but not fatty liver in diet-induced obese mice. Diabetes. 2023, 72

- 48.Tilg H, Adolph TE, Moschen AR. Multiple parallel hits hypothesis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: revisited after a decade. J Hepatol. . 2021;73:833–842. doi: 10.1002/hep.31518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schuster S, Cabrera D, Arrese M, Feldstein AE. Triggering and resolution of inflammation in NASH. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. . 2018;15:349–364. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weston CJ, Zimmermann HW, Adams DH. The role of myeloid-derived cells in the progression of liver disease. Front Immunol. . 2019;10:893. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakashima H, Nakashima M, Kinoshita M, Ikarashi M, Miyazaki H, Hanaka H, Imaki J, et al. Activation and increase of radio-sensitive CD11b+ recruited Kupffer cells/macrophages in diet-induced steatohepatitis in FGF5 deficient mice. Sci Rep. . 2016;6:34466. doi: 10.1038/srep34466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Itoh M, Suganami T, Kato H, Kanai S, Shirakawa I, Sakai T, Goto T, et al. CD11c+ resident macrophages drive hepatocyte death-triggered liver fibrosis in a murine model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. JCI Insight. . 2017;2:e92902. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.92902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deczkowska A, David E, Ramadori P, Pfister D, Safran M, Li B, Giladi A, et al. XCR1+ type 1 conventional dendritic cells drive liver pathology in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Nat Med. . 2021;27:1043–1054. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01344-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heier EC, Meier A, Julich-Haertel H, Djudjaj S, Rau M, Tschernig T, Geier A, et al. Murine CD103+ dendritic cells protect against steatosis progression towards steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. . 2017;66:1241–1250. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sutti S, Albano E. Adaptive immunity: an emerging player in the progression of NAFLD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. . 2020;17:81–92. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0210-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Graham JJ, Mukherjee S, Yuksel M, Sanabria Mateos R, Si T, Huang Z, Huang X, et al. Aberrant hepatic trafficking of gut-derived T cells is not specific to primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. . 2022;75:518–530. doi: 10.1002/hep.32193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.He S, Kahles F, Rattik S, Nairz M, McAlpine CS, Anzai A, Selgrade D, et al. Gut intraepithelial T cells calibrate metabolism and accelerate cardiovascular disease. Nature. . 2019;566:115–119. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0849-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Luck H, Tsai S, Chung J, Clemente-Casares X, Ghazarian M, Revelo XS, Lei H, et al. Regulation of obesity-related insulin resistance with gut anti-inflammatory agents. Cell Metab. . 2015;21:527–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hong CP, Park A, Yang BG, Yun CH, Kwak MJ, Lee GW, Kim JH, et al. Gut-specific delivery of T-helper 17 cells reduces obesity and insulin resistance in mice. Gastroenterology. . 2017;152:1998–2010. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu J, Quan J, Feng J, Zhang Q, Xu Y, Liu J, Huang W, et al. High glucose regulates LN expression in human liver sinusoidal endothelial cells through ROS/integrin αvβ3 pathway. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. . 2016;42:231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Henderson NC, Arnold TD, Katamura Y, Giacomini MM, Rodriguez JD, McCarty JH, Pellicoro A, et al. Targeting of αv integrin identifies a core molecular pathway that regulates fibrosis in several organs. Nat Med. . 2013;19:1617–1624. doi: 10.1038/nm.3282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Popov Y, Patsenker E, Stickel F, Zaks J, Bhaskar KR, Niedobitek G, Kolb A, et al. Integrin αvβ6 is a marker of the progression of biliary and portal liver fibrosis and a novel target for antifibrotic therapies. J Hepatol. . 2008;48:453–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hiroyama S, Rokugawa T, Ito M, Iimori H, Morita I, Maeda H, Fujisawa K, et al. Quantitative evaluation of hepatic integrin αvβ3 expression by positron emission tomography imaging using 18F-FPP-RGD2 in rats with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. EJNMMI Res. . 2020;10:118. doi: 10.1186/s13550-020-00704-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rokugawa T, Konishi H, Ito M, Iimori H, Nagai R, Shimosegawa E, Hatazawa J, et al. Evaluation of hepatic integrin αvβ3 expression in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) model mouse by 18F-FPP-RGD2 PET. EJNMMI Res. . 2018;8:40. doi: 10.1186/s13550-018-0394-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li Y, Pu S, Liu Q, Li R, Zhang J, Wu T, Chen L, et al. An integrin-based nanoparticle that targets activated hepatic stellate cells and alleviates liver fibrosis. J Control Release. . 2019;303:77–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Patsenker E, Stickel F. Role of integrins in fibrosing liver diseases. Am J Physiol Gastrointestinal Liver Physiol. . 2011;301:G425–G434. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00050.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yokosaki Y, Nishimichi N. New therapeutic targets for hepatic fibrosis in the integrin family, α8β1 and α11β1, induced specifically on activated stellate cells. Int J Mol Sci. . 2021;22:12794. doi: 10.3390/ijms222312794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nishimichi N, Tsujino K, Kanno K, Sentani K, Kobayashi T, Chayama K, Sheppard D, et al. Induced hepatic stellate cell integrin, α8β1, enhances cellular contractility and TGFβ activity in liver fibrosis. J Pathol. . 2021;253:366–373. doi: 10.1002/path.5618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Du W, Wang L. The crosstalk between liver sinusoidal endothelial cells and hepatic microenvironment in NASH related liver fibrosis. Front Immunol. . 2022;13:936196. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.936196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Guo Q, Furuta K, Lucien F, Gutierrez Sanchez LH, Hirsova P, Krishnan A, Kabashima A, et al. Integrin β1-enriched extracellular vesicles mediate monocyte adhesion and promote liver inflammation in murine NASH. J Hepatol. . 2019;71:1193–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Altrock E, Sens C, Kawelke N, Nakchbandi IA. Loss of Integrin-β1 in hepatocytes induces liver fibrosis. Z Gastroenterol. 2015, 53: A1_34

- 72.Zheng X, Liu W, Xiang J, Liu P, Ke M, Wang B, Wu R, et al. Collagen I promotes hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation by regulating integrin β1/FAK signaling pathway in nonalcoholic fatty liver. Oncotarget. . 2017;8:95586–95595. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Peng Z, Hao M, Tong H, Yang H, Huang B, Zhang Z, Luo KQ. The interactions between integrin α 5 β 1 of liver cancer cells and fibronectin of fibroblasts promote tumor growth and angiogenesis . Int J Biol Sci. . 2022;18:5019–5037. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.72367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wu Y, Qiao X, Qiao S, Yu L. Targeting integrins in hepatocellular carcinoma. Expert Opin Ther Targets. . 2011;15:421–437. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.555402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leng C, Zhang Z, Chen W, Luo H, Song J, Dong W, Zhu X, et al. An integrin beta4-EGFR unit promotes hepatocellular carcinoma lung metastases by enhancing anchorage independence through activation of FAK–AKT pathway. Cancer Lett. . 2016;376:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li J, Hao N, Han J, Zhang M, Li X, Yang N. ZKSCAN3 drives tumor metastasis via integrin β4/FAK/AKT mediated epithelial–mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. . 2020;20:216. doi: 10.1186/s12935-020-01307-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 77.Sun F, Wang J, Sun Q, Li F, Gao H, Xu L, Zhang J, et al. Interleukin-8 promotes integrin β3 upregulation and cell invasion through PI3K/Akt pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. . 2019;38:449. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1455-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xu ZZ, Xiu P, Lv JW, Wang FH, Dong XF, Liu F, Li T, et al. Integrin αvβ3 is required for cathepsin B-induced hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Mol Med Rep. . 2015;11:3499–3504. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.3140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wu Y, Zuo J, Ji G, Saiyin H, Liu X, Yin F, Cao N, et al. Proapoptotic function of integrin β3 in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. . 2009;15:60–69. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sipos B, Hahn D, Carceller A, Piulats J, Hedderich J, Kalthoff H, Goodman SL, et al. Immunohistochemical screening for beta6-integrin subunit expression in adenocarcinomas using a novel monoclonal antibody reveals strong up-regulation in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas in vivo and in vitro . Histopathology. . 2004;45:226–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.01919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Patsenker E, Wilkens L, Banz V, Österreicher CH, Weimann R, Eisele S, Keogh A, et al. The αvβ6 integrin is a highly specific immunohistochemical marker for cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. . 2010;52:362–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zheng J, Miao W, Huang C, Lin H. Evaluation of 99mTc-3PRGD2 integrin receptor imaging in hepatocellular carcinoma tumour-bearing mice: comparison with 18F-FDG metabolic imaging. Ann Nucl Med. . 2017;31:486–494. doi: 10.1007/s12149-017-1173-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lin BQ, Zhang WB, Zhao J, Zhou XH, Li YJ, Deng J, Zhao Q, et al. An optimized integrin α6-targeted magnetic resonance probe for molecular imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. . 2021;8:645–656. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S312921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hiroyama S, Matsunaga K, Ito M, Iimori H, Morita I, Nakamura J, Shimosegawa E, et al. Evaluation of an integrin αvβ3 radiotracer, [18F]F-FPP-RGD2, for monitoring pharmacological effects of integrin alpha(v) siRNA in the NASH liver. Nucl Med Mol Imag. . 2023;57:172–179. doi: 10.1007/s13139-023-00791-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shao T, Chen Z, Belov V, Wang X, Rwema SH, Kumar V, Fu H, et al. [18F]-Alfatide PET imaging of integrin αvβ3 for the non-invasive quantification of liver fibrosis. J Hepatol. . 2020;73:161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gubatan J, Keyashian K, Rubin SJ, Wang J, Buckman C, Sinha S. Anti-Integrins for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: current evidence and perspectives. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. . 2021;14:333–342. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S293272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yossipof TE, Bazak ZR, Kenigsbuch-Sredni D, Caspi RR, Kalechman Y, Sredni B. Tellurium compounds prevent and reverse type-1 diabetes in NOD mice by modulating α4β7 integrin activity, IL-1β, and T regulatory cells. Front Immunol. . 2019;10:979. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Morshed A, Abbas AB, Hu J, Xu H. Shedding new light on the role of ανβ3 and α5β1 integrins in rheumatoid arthritis. Molecules. . 2019;24:1537. doi: 10.3390/molecules24081537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lowin T, Straub RH. Integrins and their ligands in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. . 2011;13:244. doi: 10.1186/ar3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mullamitha SA, Ton NC, Parker GJM, Jackson A, Julyan PJ, Roberts C, Buonaccorsi GA, et al. Phase I evaluation of a fully human anti-alphav integrin monoclonal antibody (CNTO 95) in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. . 2007;13:2128–2135. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Besse B, Tsao LC, Chao DT, Fang Y, Soria JC, Almokadem S, Belani CP. Phase Ib safety and pharmacokinetic study of volociximab, an anti-α5β1 integrin antibody, in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. . 2013;24:90–96. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhou Y, Gao S, Huang Y, Zheng J, Dong Y, Zhang B, Zhao S, et al. A pilot study of 18F-alfatide PET/CT imaging for detecting lymph node metastases in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep. . 2017;7:2877. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03296-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Steiger K, Quigley NG, Groll T, Richter F, Zierke MA, Beer AJ, Weichert W, et al. There is a world beyond αvβ3-integrin: multimeric ligands for imaging of the integrin subtypes αvβ6, αvβ8, αvβ3, and α5β1 by positron emission tomography. EJNMMI Res. . 2021;11:106. doi: 10.1186/s13550-021-00842-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cox D. How not to discover a drug—integrins. Expert Opin Drug Discov. . 2021;16:197–211. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2020.1819234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Grant AJ, Lalor PF, Hubscher SG, Briskin M, Adams DH. MAdCAM-1 expressed in chronic inflammatory liver disease supports mucosal lymphocyte adhesion to hepatic endothelium (MAdCAM-1 in chronic inflammatory liver disease) J Hepatol. . 2001;33:1065–1072. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Colombel JF, Sands BE, Rutgeerts P, Sandborn W, Danese S, D′Haens G, Panaccione R, et al. The safety of vedolizumab for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut. . 2017;66:839–851. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Koullias ES, Koskinas J. Pharmacotherapy for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease associated with diabetes mellitus type 2. J Clin Transl Hepatol. . 2022;10:965–971. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2021.00564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gahmberg CG, Grönholm M. How integrin phosphorylations regulate cell adhesion and signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. . 2022;47:265–278. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2021.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]