Abstract

Curricular content in undergraduate biology courses has been historically hetero and cisnormative due to various cultural stigmas, biases, and discrimination. Such curricula may be partially responsible for why LGBTQ+ students in STEM are less likely to complete their degrees than their non-LGBTQ+ counterparts. We developed Broadening Perspective Activities (BPAs) to expand the representation of marginalized perspectives in the curriculum of an online, upper-division, undergraduate animal behavior course, focusing on topics relating to sex, gender, and sexuality. We used a quasiexperimental design to assess the impact of the BPAs on student perceptions of course concepts and on their sense of belonging in biology. We found that LGBTQ+ students entered the course with a better understanding of many animal behavior concepts that are influenced by cultural biases associated with sex, gender, and sexuality. However, LGBTQ+ students who took the course with the BPAs demonstrated a greater sense of belonging in biology at the end of the term compared with LGBTQ+ students in the course without BPAs. We also show that religious students demonstrated improved comprehension of many concepts related to sex, gender, and sexuality after taking the course with BPAs, with no negative impacts on their sense of belonging.

INTRODUCTION

Efforts to make undergraduate classrooms more inclusive and affirming for LGBTQ+ students are urgently needed. The percentage of the United States (U.S.) population that identifies as LGBTQ+ doubled over the past decade, from 3.5% in 2012 to 7.2% in 2022 (Jones, 2023). The percentage of openly LGBTQ+ individuals within a sample is inversely correlated with age, with 19.7% of Generation Z adults (those between the ages of 20 and 27 in 2024) and 11.2% of millennials (those between the ages of 28 and 43 in 2024) identifying as LGBTQ+. Many recent cultural changes have empowered LGBTQ+ individuals in younger generations to identify more openly. A traditional incoming undergraduate in 2024 at 18 years old would have been born in 2006, 3 years after antisodomy laws were ruled federally unconstitutional in 2003. This individual would have been 5 years old when, “Don't Ask, Don't Tell” was repealed in 2011, 9 years old when the Supreme Court federally protected the right to marriage for same-sex couples in 2015, and 14 years old when the Supreme Court protected LGBTQ+ employees from discrimination in 2020. Currently, undergraduate students in the U.S. have experienced a wave of progress toward cultural acceptance and legal protections for LGBTQ+ people, unlike any other generation before them. However, in recent years, LGBTQ+ communities across the U.S. have faced both cultural and legal backlash, much of which specifically targets the trans community. In 2020, 77 bills targeting LGBTQ+ rights were introduced across the U.S. In 2021 and 2022, that number rose to 154 and 180, respectively. In 2023, 510 bills were introduced at the state level that aimed to restrict LGBTQ+ rights (ACLU, 2023; Choi, 2023). Much of this anti-LGBTQ+ legislation is targeted directly at the K12 school experience, and all have the potential to negatively impact the mental health of LGBTQ+ individuals (Horne et al., 2022).

The need for more inclusive and affirming undergraduate experiences is particularly important in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM, Cooper et al., 2020). LGBTQ+ undergraduates are less likely to major in STEM disciplines and are more likely to leave STEM majors than their non-LGBTQ+ counterparts (Greathouse et al., 2018; Hughes, 2018; Maloy et al., 2022), and sense of belonging has been shown to be associated with persistence in STEM for LGBTQ+ undergraduates (Hughes and Kothari, 2023). Research on the specific experiences of LGBTQ+ undergraduates in STEM is very limited (Butterfield et al., 2018), particularly within specific subfields of STEM, including biology (Sona et al., 2022). Notably, representation in STEM differs among identities under the LGBTQ+ umbrella and is affected by other intersectional identities (Sansone and Carpenter, 2020). LGBTQ individuals who hold underrepresented and underserved intersectional identities often report additional challenges in STEM. For example, women and racial/ethnic minorities who are STEM professionals are more likely to experience professional devaluation and harassment at work, compared with men and white LGBTQ+ individuals (Cech and Waidzunas, 2021). Such discrimination amplifies the need for interventions to create more inclusive STEM spaces for individuals with underrepresented and underserved identities, given that the multifaceted stigmas are likely partially responsible for these trends (Freeman, 2020; Palmer et al., 2022), and STEM undergraduates with marginalized identities express frustration that they are often asked to work to combat the same stigmas that negatively affect them (Miller and Downey, 2020). LGBTQ+ students report experiencing feelings of alienation due to the climate in STEM, which they describe as heterosexist (Linley et al., 2018), and as a result are selective about their decision to come out in the STEM classroom (Cooper and Brownell, 2016).

In addition to the potentially unfriendly environment for LGBTQ+ students in science courses, biased curricular content may also be partially responsible for LGBTQ+ students’ lack of belonging, particularly in biology (Cooper et al., 2020; Casper et al., 2022). Conflict between biology course content and the lived experiences of trans, nonbinary, and gender nonconforming undergraduates can drive feelings of erasure and alienation based (Casper et al., 2022). Stigmatization against LGBTQ+ identities affects what college instructors choose to teach across many undergraduate fields of study, including biology (Marsh et al., 2022). In an interview study, trans students report feelings of alienation in undergraduate biology classrooms due to the binary simplification and exclusion of the diversity of life as it relates to sex and gender (Casper et al., 2022). Participants in this study highlighted examples related to humans but also of plant and animal diversity and expressed frustration that their peers uncritically accepted the binary teachings of biology professors.

Some biology subfields are more prone to excluding LGBTQ+ individuals owing to the content. For example, the field of animal behavior discusses many aspects of behavior related to the concepts of sex and gender, including but not limited to communication between and within sexes, sexual selection, mating systems, and parental care. The extent to which the paradigms for understanding these concepts in animal behavior have been influenced by anti-LGBTQ+ stigma has not been studied, but prominent LGBTQ+ animal behaviorists have argued that binary and cisheteronormative thought has pervaded this field, hindering the field's ability to develop a full understanding of the true nature of animal behavior (Roughgarden, 2013; Monk et al., 2019). Undergraduate animal behavior curricula often teach about sexual selection, Darwin's proposed sex roles, and sex-specific behaviors that are presented as ubiquitous across the animal world (Alcock, 2009). It neglects, or only briefly discusses as an exception to the rule, the many ways that sex can present as more than a binary and that homosexual behaviors can be evolutionarily important social behaviors in many animals (Bagemihl, 1999; Roughgarden, 2013). In this way, these curricula can reinforce students’ assumptions that align with cisheteronormative understandings of sex, sexuality, and gender, and can fail to encourage critical analysis of the cultural systems of power that influence the production of scientific knowledge. Animal behavior is taught in many classrooms and textbooks with a historical emphasis on ethology and routinely highlights the contributions of European men (e.g., Nico Tinbergen, Konrad Lorenz, and Karl von Frisch), but curricula often exclude many other prominent animal behaviorists including women, people of color, nonbinary, and trans people, and people from outside of Europe or the U.S. (Dona and Chittka, 2020; Tang-Martínez, 2020b). Systemic bias and discrimination affect access to resources, recognition of contributions, and ability to shape the direction of the field for animal behaviorists across identities of race, gender, class, and nationality (Giurfa and de Brito Sanchez, 2020; Jaffe et al., 2020; Lee, 2020; Tang-Martínez, 2020a).

Recent recommendations to enhance the experiences of LGBTQ+ students in STEM have called for the diversification of curricula to reflect the full range of gender and sexuality theories and examples in nature, and to present LGBTQ+ role models. They advocate for the inclusion of LGBTQ+ scientists explicitly in curricula (Recommendation 10 from Cooper et al., 2020 and Principle 5 from Zemenick et al., 2022), for positive discussions of the diversity of life as it relates to gender and sexuality in the curriculum (Recommendation 11 and 12 from Cooper et al., 2020 and Principle 1 from Zemenick et al., 2022), and for direct engagement with the influence of history and culture on the field of science (Principle 5 from Zemenick et al., 2022). Despite these calls, we are not aware of any inclusive curricular innovations that have been formally evaluated to test the impact on all students and more specifically LGBTQ+ students.

Current Study

We set out to expand the course curriculum to correct for the historical exclusion of the perspectives of LGBTQ+ people, people of color, and women for a large-enrollment, online, upper-division (300-level) animal behavior course taught at a large R1 Hispanic Serving Institution in the southwestern U.S. To address this goal, we developed a set of Broadening Perspective Activities (BPAs), which primarily focused on expanding the course's coverage of topics related to sex, gender, and sexuality because undergraduate students had drawn instructors’ attention to potentially cisheteronormatively biased content in previous iterations of the course. To assess the impact of the BPAs, we conducted a quasiexperimental study; we designed and implemented a pre- and postcourse survey, once with the course in its original form and twice with the course that included the BPAs. The survey aimed to assess students’ comprehension of topics related to sex, gender, and sexuality, as well as students’ sense of belonging in the course and in biology.

We first investigated the differences in the prior knowledge that students of different identities bring to the class with respect to gender and sexuality topics in the field of animal behavior. We hypothesized that students’ prior knowledge was likely informed by many factors including their high school education, cultural background, and identities (Lemke, 2001; Aune and Guest, 2019). For example, a student attending a religious high school may have not been introduced to the differences between sex and gender in their high school biology course, or an LGBTQ+ student may have independently learned about same-sex animal behaviors. Understanding the culturally specific funds of knowledge that students bring into the classroom and incorporating that knowledge into the curriculum can improve accessibility and inclusivity of classroom content (Denton and Borrego, 2021). Further, identifying differences in students’ prior knowledge is critical when interpreting differences that we might observe in how our BPAs differentially affect students based on their social identities.

We developed the BPAs with the aims of enhancing the sense of belonging of LGBTQ+ students, and improving all students’ understanding of inclusive sex, gender, and sexuality concepts in the field of animal behavior. We also predicted that BPAs might have similarly positive effects on the sense of belonging for students of historically discriminated against gender identities (women, nonbinary, etc.; Busch et al., 2022). We included religious identity in our models to control for differences in religious-based anti-LGBTQ stigma (Campbell et al., 2019). We also considered that the BPAs might decrease the sense of belonging for students who may experience cultural conflict between their religious and STEM identities (Barnes et al., 2021). Additionally, several of our BPAs discuss histories of racism and colonialism within scientific fields and we therefore also considered whether sense of belonging was differentially affected across racial identities.

Our specific research questions were:

To what extent do undergraduate students of varying identities (LGBTQ+ identities, genders, and religious affiliations) differ in the prior knowledge that they bring into an animal behavior course, specifically with respect to concepts relating to sex, gender, and sexuality?

To what extent does the addition of BPAs improve student abilities to critically evaluate assumptions in the field of animal behavior that are influenced by cultural norms associated with sex, gender, and sexuality?

To what extent does the addition of BPAs affect the sense of belonging for students of different LGBTQ+, gender, religious, and racial identities?

METHODS

This study was approved by the Arizona State Institutional Review Board (Study 00014133).

Positionality Statement:

In summer of 2021, a departmental Inclusive Teaching Fellowship partially funded the efforts for the curricular redesign, which was a collaboration between former teaching assistants from the summer of 2020 (D. Jackson, A. Biera, C. Hawley, J. Lacson, E. Webb) and the professor of the course (K. McGraw), with consultation from an instructional designer (Lenora Ott) and a biology education researcher (K. Cooper). Some members of the research team identify as members of the LGBTQ+ community and some do not. Although not all authors are comfortable defining their identities in this context, those who are represent various identities including (alphabetically) Catholic, cisgender, gay, heterosexual, man, Mexican-American, nonbinary, queer, white, woman, and from a nontraditional family. Our different lived experiences as biology researchers, biology education researchers, and educators helped us to collaboratively design and assess inclusive learning materials. Collaboration and communication within the group helped us to identify and reduce potential biases in our research design. For example, the lived experiences of LGBTQ+ individuals were helpful when identifying cisheteronormative assumptions that are often promoted among biologists, while the perspective of non-LGBTQ+ researchers was helpful in crafting BPAs that would resonate with students outside of the LGBTQ+ community. Additionally, some of our research team are no longer but were previously religious, particularly during their time in college, and drew from their experiences as a religious college biology student when contextualizing the study findings. We also consulted biology education experts on the experiences of religious college biology students when writing the manuscript.

Study Context

The focal animal behavior courses were offered online during the summer and ran for approximately 5 wk. We studied this course over three iterations, Summer 2021 session B (i.e., second half of the summer; 185 students), Summer 2022 session A (first half of the summer; 61 students), and Summer 2022 session B (138 students). In the first iteration (Summer 2021 B), we implemented the course without the addition of the BPAs (BPA-). For both summer 2022 courses, we implemented the course with the BPAs (BPA+). Aside from the presence or absence of the BPAs, the courses were intended to be as identical as possible. All iterations of the animal behavior online course incorporate previously recorded video lectures, textbook-type readings, interactive visual and group activities, self-assessment questions, and predeveloped animal-observation activities. Each iteration was also taught by the same professor. Online courses can increase access to higher education across many social identities (Mead et al., 2020), but social dynamics can differ between online and in person courses (Busch et al., 2022) and therefore our findings should be interpreted as specific to the context of this course.

We added six BPAs (Supplemental Material) to the base content of this animal-behavior course. Each activity followed a module in the course on the same topic. Students were given the choice to complete four of the six activities for full credit. Some BPAs addressed issues relating to oppression, abuse of power, racism, sexual assault, transphobia, homophobia, and eugenics. As such, we felt that allowing students to choose their activities could increase their sense of value and investment in the activity, both of which are associated with an increased sense of belonging (Trujillo and Tanner, 2014) and permit them to avoid personally potentially triggering content. Because the content of these activities could challenge the well-being of certain students based on particular experiences that they may have previously had, we also wanted to allow them to opt out of engaging in particular topics to create an intervention aimed at promoting their belonging. We determined that most BPAs did not require a content warning except for the module on Human Behavior which dealt directly with human-based studies of potentially triggering behaviors including assault and discrimination, and we provided a content warning as well as two options within that module if students preferred to avoid the potentially triggering content (See Supplemental Material). Students completed BPAs alone (i.e., not group work).

We aimed to use the BPAs to: 1.) Foster critical analytical approaches of students to histories and practices in the field of animal behavior along the axes of race, sex, gender, and sexuality, 2.) Present a more comprehensive depiction of the diversity of scientists and scientific approaches that have contributed to this field, and 3.) Cultivate a sense of belonging and science identity in historically marginalized undergraduate students. We summarize each BPA in the following section (see Supplemental Material for the full activities). In these BPAs, we highlighted the voices of marginalized communities in the field of animal behavior, and most of the content was either written by a member of one such community or featured interviews and stories from that marginalized community, similar to “Scientist Spotlights” (Schinske et al., 2016; Ovid et al., 2023). However, our BPAs are distinct from “Scientist Spotlights” because they specifically highlight content that discusses how a scientist's own positionality can affect their own research and the practices of the field. Students were often asked reflection questions at the start of the BPAs to encourage them to bring their own perspectives into the course. After engaging with a reading, they were asked additional reflection questions that intended to illuminate the influence of culture on our interpretation of nuanced concepts in biology. The reflection questions do not have correct answers, and student reflections were only graded for completeness.

Broadening Perspectives Activities:

History of Animal Behavior. Students were asked to reflect on how they would expect the cultural influences on the field of animal behavior to bias the knowledge generated by researchers in this field. Students were then provided with reading material that discussed the connections between one of the prominent male European animal behaviorists who was highlighted in the course's textbook, Konrad Lorenz, and Nazi ideology (Kalikow, 1983; Klopfer, 1994). Finally, they read an excerpt on Charles H. Turner, an African-American animal behaviorist who was not highlighted in the course content, but whose early contributions to the field were comparable to the scientists highlighted in the textbook, despite facing numerous racial-discriminatory barriers (Dona and Chittka, 2020). With each excerpt, students were asked to reflect on their developing understanding of the influence of culture on the history and processes of animal behavior research. This BPA aimed to encourage students to begin to see the effects of politics and social context on the history of animal behavior, and to start to question whose perspectives held outsized power over the paradigms of this field of study.

Sexual Selection. After reading a section of the course textbook on sexual selection, students were asked to critically evaluate the types of relationships portrayed in that reading between animals of different sexes and between animals of the same sex. They then read three additional excerpts from Animal homosexuality and natural diversity (Bagemihl, 1999) and Evolution's Rainbow: Diversity, gender, and sexuality in nature and people (Roughgarden, 2013) that highlighted the ways that homosexual behavior in animals can manifest and play key roles in their social lives. Next, they read an excerpt that directly refuted many stereotypes about animal behaviors that are derived from cultural norms spread through European colonialism around sex, gender, and sexuality (Roughgarden, 2013). Finally, they were asked to reflect on how biologists define sex, how their culture defines sex, and how they as an individual would define sex.

Methodology. Students were asked to reflect on the objectivity of the methods that they had been using to study animal behaviors in this class as part of an experiential project that is threaded through the semester. They were then provided with an excerpt from the paper The history and impact of women in animal behavior, and the ABS: a North American perspective (Tang-Martínez, 2020a) that details the history of discrimination against women in the field of animal behavior, with emphasis on the ways that the field of animal behavior changed when women could access resources needed to direct their own research programs in the mid-to-late 1900s, including the introduction of novel methodologies. They were asked to reflect on the notion of objectivity in science and on the influence of culture on the scientific process.

Hermaphroditism. Students were first asked to reflect on the traits that are shared between males and those that are shared between females, as well as those that differ among males and those that differ among females. They were then provided with an excerpt from the book Evolution's Rainbow (Roughgarden, 2013), which discusses the occurrence, mechanisms, and functions of hermaphroditism and intersexuality among animals. This reading highlights the important social roles of nonreproductive intersex individuals in some nonhuman species and directly confronts societal assumptions with statements like, “The mention of infertility plays to the prejudice that something is ‘wrong’ with intersexes. But the story is more complicated” (Roughgarden, 2013, p. 36). They were asked to reflect on how intersexuality or hermaphroditism might affect the natural history of an animal, and on their opinion about the use of sexed terms (e.g., penis) for animals of various sexes (e.g., female hyenas).

Migration. Students listened to an audiobook recording of the essay, Like the Monarch, Human Migrations During Climate Change by Sarah Stillman (Stillman, 2021). This essay describes the effects of climate change on the migrations of many species, including humans, and how the language that we use to describe those migratory behaviors affects our cultural understanding of them. They were asked to reflect on the influence of the field of animal behavior on sociopolitical events, and how language shapes our understanding of the natural world. They were also asked to consider via written responses the role of local communities in animal behavior research, and the interactions between popular culture and animal behavior research.

Human Behavior. Having learned about the biological and evolutionary bases for human behaviors as a final module in the course, in this BPA the students were asked to consider the cultural influences that shape these understandings. They began by reading an excerpt from Sex Itself: The Search for Male and Female in the Human Genome (Richardson, 2015) that details how the X and Y chromosomes came to be called “sex chromosomes” and the arguments both for and against this classification. They were asked to reflect on the influence of language on their own studies of animal behavior, on the unique importance of their own cultural perspective, and on the cultural biases in the course textbook. Then, students were given the choice to listen to one of two podcast episodes. The first tells the story of Dr. Mary Koss, a professor at the University of Arizona, who copublished the first national study on rape in 1987, and who faced bias from her colleagues based on her gender identity (This American Life, 2022). The second is an investigation into the scientific literature on the benefits and potential risks of gender-affirming healthcare for trans people, and the cultural phenomena that shape how that science is (or is not) incorporated into policy-making decisions (Science Vs, 2022). For either reading, they were asked to reflect on the decisions that researchers make when designing their studies that might be culturally influenced, on the moral responsibility of scientists, and on the ways that personal experiences can reveal flaws in culturally biased research.

Survey.

We developed a survey instrument to evaluate the specific impacts of these BPA course additions on student abilities to learn animal behavior concepts that might be affected by cultural norms around sex, gender, and sexuality, as well as students’ sense of belonging in the course and in biology broadly. The survey consisted of 25 close-ended content questions, 10 sense-of-belonging questions, and 15 demographic questions. All content and belonging survey questions are provided in Table 1 and a copy of the full survey can be found in the Supplemental Material. Students completed the survey at the beginning of the course (presurvey), as well as at the end of the course (postsurvey). Students were offered two extracredit points to take each survey (∼1.6% of the total course points).

TABLE 1.

Survey questions. Survey questions that were given to students during the first and last week of their course. All questions were presented with Six-point Likert scale responses from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree” with “I don't know” as a neutral option, except for Sex Question 5 and Sexuality Question 4, which were presented with a range of possible proportions

| Question | Sex Questions: After having taken the course, students will better recognize that sex is more complex than a simple binary, that the behaviors associated with the sex categories of “male” and “female” vary across animal species, and that many animals exist as more than one sex in their lifetimes. | Intended Response: The intended response is in the direction of a more nuanced perspective that is less influenced by cisheteronormative assumptions. |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The sex of an animal can be categorized as either male or female. | Towards Strongly Disagree |

| 2 | In any given pair of a male and a female, the male will have higher levels of testosterone than the female. | Towards Strongly Disagree |

| 3 | In any given pair of a male and a female, the female will have higher levels of estrogen than the male. | Towards Strongly Disagree |

| 4 | Two males of different species will have more in common with each other than a male and a female of different species. | Towards Strongly Disagree |

| 5 | Excluding insects, what proportion of animal species exist as more than one sex during their life? | Towards a greater proportion |

| Sexuality Questions: After having taken the course, fewer students will apply western cisheteronormative assumptions to animal behaviors than they did before taking the course. | ||

| 1 | Heterosexual behaviors, defined as mating with another animal of a different sex, are inherently more evolutionarily advantageous than homosexual behaviors. By “evolutionarily advantageous” we mean the animal will have higher fitness or produce more offspring. By “homosexual behaviors” we mean mating with another animal of the same sex | Towards Strongly Disagree |

| 2 | Species that stay the same sex throughout their entire lives have more evolutionary advantage (have higher fitness or will produce more offspring) than species that change sexes throughout their entire lives. | Towards Strongly Disagree |

| 3 | Homosexual behaviors are not evolutionarily advantageous. | Towards Strongly Disagree |

| 4 | What proportion of sexual animal species exhibit homosexual behaviors? | Towards Strongly Disagree |

| 5 | Monogamous species have a greater evolutionary advantage over nonmonogamous species. | Towards Strongly Disagree |

| 6 | All animals are cared for by their parents when they are young. | Towards Strongly Disagree |

| 7 | Any animal would be better off if it were raised by their biological parents than by other members of the same species. | Towards Strongly Disagree |

| 8 | Any nonhuman animal that is raised by their biological parents is better off than another animal that isn't raised by their biological parents. | Towards Strongly Disagree |

| 9 | In animals, males are more likely to cheat on their partner than females. By “cheating” we mean mating with an animal outside of a pair-bond. | Towards Strongly Disagree |

| 10 | Polygyny (1 male mating with multiple females) is always more evolutionarily advantageous than polyandry (1 female mating with multiple males). | Towards Strongly Disagree |

| 11 | More aggressive males produce more offspring than less aggressive males. | Towards Strongly Disagree |

| Normativity Questions: After taking the course, students will better recognize the influence of the impact of cultural normativity on scientific studies, and the role that language plays in shaping those norms. | ||

| 1 | The language that we use affects our ability to understand the natural world. | Towards Strongly Agree |

| 2 | Our cultural biases limit our ability to understand the natural world. | Towards Strongly Agree |

| 3 | Sex and gender mean the same thing. | Towards Strongly Disagree |

| 4 | It is important to distinguish between sex and gender when talking about biology. | Towards Strongly Agree |

| 5 | The scientific understanding of sex includes social norms, behaviors, and roles associated with being a particular sex. | Towards Strongly Agree |

| 6 | The scientific understanding of gender includes norms, behaviors, and roles associated with a particular gender. | Towards Strongly Agree |

| 7 | LGBTQ+ identities and associated behaviors are natural in a biological sense. | Towards Strongly Agree |

| 8 | The behaviors associated with LGBTQ+ identities are exclusive to humans, and are not represented in the animal world. | Towards Strongly Disagree |

| 9 | Studying the natural world influences my understanding of myself and other humans. | Towards Strongly Agree |

| Belonging in the Course (Belonging C1): After taking the course, students will have a higher sense of belonging in the course. BIO 331 is the course code for the animal behavior course at ASU. | ||

| 1.1 | I feel comfortable in BIO 331 | Towards Strongly Agree |

| 1.2 | I am a part of BIO 331 | Towards Strongly Agree |

| 1.3 | I am committed to BIO 331 | Towards Strongly Agree |

| 1.4 | I am supported by BIO 331 | Towards Strongly Agree |

| 1.5 | I am accepted in BIO 331 | Towards Strongly Agree |

| Belonging in Biology (Belonging C2): After taking the course, students will have a higher sense of belonging in the field of biology. | ||

| 2.1 | I feel comfortable in the Biology community | Towards Strongly Agree |

| 2.2 | I am a part of the Biology community | Towards Strongly Agree |

| 2.3 | I am committed to the Biology community | Towards Strongly Agree |

| 2.4 | I am supported by the Biology community | Towards Strongly Agree |

| 2.5 | I am accepted by the Biology community | Towards Strongly Agree |

We developed survey questions to address three cognitive learning goals (sex, sexuality, and normativity categories) and two affective learning goals (belonging in course and belonging in biology) that the BPAs were backward-designed to address (Wiggins and McTighe, 1998; Allen and Tanner, 2007). BPAs 2, 3, 4, and 6 specifically addressed sex and sexuality, but all 6 BPAs had the potential to affect students’ understanding of normativity and their sense of belonging. Our BPA specific learning goals were:

Sex Category: Students will implement a more nuanced understanding of sex. They will question statements that assume sex is a simple binary, that the behaviors associated with the sex categories of “male” and “female” do not vary across animal species, and that animals only exist as one sex in their lifetimes.

Sexuality Category: Students will question cisheteronormative assumptions related to animal behaviors.

Normativity Category: Students will display a better understanding of how cultural norms impact scientific studies, and that language plays a role in shaping those norms.

Belonging in Course Category: Students will express a greater sense of belonging in the course.

Belonging in Biology Category: Students will express a greater sense of belonging in the broader field of biology.

Sex Category: Nuanced or Binary Conception of Sex in Animals.

To assess whether the addition of BPAs to the course resulted in a more nuanced understanding of sex in animals, we developed five survey questions to measure concepts related to sex that can be affected by binary thinking (Table 1). We presented students with a statement that implied that the sex binary is universal (Sex Question 1), two statements that implied that sex hormones are always associated with sex categories (Sex Questions 2 and 3), a statement that implies sex categories are associated with an essential truth across all species (Sex Question 4), and a question about the proportion of animals that transition between sexual categories (Sex Question 5). For the first four questions, students were presented with a position statement and then several Likert-scale answer options: strongly agree, agree, slightly agree, I am unsure, slightly disagree, disagree, strongly disagree. For the fifth close-ended survey question, students were asked about their expected proportion of animal species that meet a criterion, and for these they were presented with the options: 0, 5, 20, 33, 66, 80, 95, and 100%, and I am unsure.

Sexuality Category: Nuanced or Cisheteronormative Conception of Sexuality in Animals.

To assess the impact of the BPAs on student understandings of sexuality in animals, we developed 11 survey questions to measure different concepts relating to sexuality (Table 1). Items investigated student understandings of the evolutionary role of homosexuality (Sexuality Question 1, 3, and 4), of hermaphroditism (Sexuality Question 2), and of monogamy (Sexuality Question 5, 9, 10) in animal species. We also presented students with statements related to the nuclear-family construct (Sexuality Questions 6, 7, 8) and about the evolutionary benefit of aggression in males (Sexuality Question 11). Ten of these questions followed the same Likert scale format as the questions described in the sex category, and one (Sexuality Question 4) followed the same proportion format as Sex Question 5.

Normativity Category: Recognition of the Influence of Culture on Scientific Processes.

We developed nine survey questions to test the impact of BPAs on student understandings of the impact of cultural normativity on the scientific process. These investigated the role of language (Normativity Questions 1, 3, and 4), biases (Normativity Question 2), and social constructs (Normativity Questions 5 and 6) in shaping our understanding of animal behaviors. We also investigated student beliefs that LGBTQ+ identities are natural (Normativity Questions 7 and 8) and investigated whether students believed that their understanding of nature influenced their sense of self (Normativity Question 9). All of these questions followed the same Likert scale format as the questions described in the sex category.

Belonging Categories: Student Sense of Belonging in the Course and in Biology.

We used five survey questions to test student sense of belonging in the course and five questions to test their sense of belonging in the field of biology following methods from a previously developed and validated scale (Anderson-Butcher and Conroy, 2002). All of these questions followed the same Likert scale format as the questions in the sex category.

Validity and Reliability of Survey Questions.

The sets of questions assessing nuanced or binary conception of sex or animals, nuanced, or cisheteronormative conception of sexuality in animals, and recognition of the influence of normed culture on scientific processes were developed by members of the author team who were graduate students in biology and had previously worked as teaching assistants for the animal behavior course (A. Biera, C. Hawley, D. Jackson, J. Lacson, E. Webb). These questions were reviewed by the professor of the course who is an expert in the field of animal behavior (K. McGraw), a biology-education researcher (K. Cooper), and an instructional designer (Lenora Ott). Before finalizing the instrument, three researchers performed think-aloud interviews with six undergraduate students to evaluate the cognitive validity of the survey (Trenor et al., 2011). For each interview, the interviewer read each survey question, then interviewees were asked to state what they believe the question is asking, and then interviewees were asked to respond to the question. Survey questions were then revised based on interviewee responses between each interview; after the six interviews, no additional changes were warranted.

Our questions were designed to explore student responses broadly across the category of interest, not to collectively test a latent construct. Within the sexuality category, for example, students are asked to respond to the statement, “Homosexual behaviors are not evolutionarily advantageous,” as well as to the statement, “All animals are cared for by their parents when they are young.” While both survey questions can illuminate students’ degree of reliance on cisheteronormative assumptions in their interpretations of animal behaviors, these questions are intentionally distinct from each other. We, therefore, present the analyses of students’ responses to each individual content question, to demonstrate the boundaries of the effect of the BPAs on students’ cisheteronormative assumptions. Additionally, we conducted a collective analysis of all questions in each content category (sex, sexuality, normativity). We dropped the two questions that were not on a Likert scale (Sex Q5 and Sexuality Q4) from collective analyses. The collective analyses should be interpreted cautiously because the content-based questions were not developed to test a latent construct. Each set of five belonging questions were designed to collectively measure belonging in biology and belonging in the course, respectively (Anderson-Butcher and Conroy, 2002).

We assessed the validity of each construct using confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) as a correlated five-factor model, in which all categories are treated as a single factor (sex, sexuality, normativity, belonging in course, and belonging in biology). Summary statistics indicated that student responses to some questions deviated from normality (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3), so we used a robust maximum likelihood estimator with the Satorra-Bentler correction in the CFAs. Evaluation of these statistics suggested that collective assessment of the survey questions within categories is only supported for the two affective learning goal categories (belonging categories) and for only one of the cognitive learning goal categories (Sex) in both pre- and postcourse survey analyses. We assessed the consistency of the questions within each category using McDonald's omega (Hancock et al., 2010). This measure does not assume equivalence of factor loadings in the model, which is especially important given our study's broad range of questions within each category, some of which directly target the latent construct much more than others. Omega values indicated that only the two affective learning goal categories were consistent, although the omega value for Sexuality approached significance. We present results of collective analyses of each cognitive category for reference, but these results should be very cautiously interpreted given the results of the CFA and the McDonald's omega values. We do not present individual results for each question in the Belonging categories and only present the results of the collective analyses because these were previously designed with the intention of collective analysis (unlike our cognitive categories), and because collective analysis is supported by the results of the CFA and the omega values for these question sets.

Analyses

All analyses were conducted in R (Ihaka and Gentleman, 1996) with the MASS (Ripley et al., 2013) and lm.beta (Behrendt, 2023) packages or Python (Python, 2021) with the Pandas (McKinney and Team, 2015), SciPy (Virtanen et al., 2020), NumPy (McKinney, 2012), statsmodels (Seabold and Perktold, 2010), scikit-learn (Pedregosa et al., 2011), and Matplotlib (Hunter, 2007) packages. The code used for the data processing and analysis can be accessed here: https://github.com/dannyjackson/StudentSurveyAnalyses. We grouped student responses for both BPA+ courses for all analyses. We filtered the data to include only students who took both the presurvey and the postsurvey, and to exclude any student who took the course twice. After filtering, we had a total of 198 responses, with 69 student responses for the BPA- course and 129 student responses for the BPA+ course. Likert scale student responses were coded into numerical values: Strongly Disagree = −3, Disagree = −2, Slightly Disagree = −1, I Am Unsure = 0, Slightly Agree = 1, Agree = 2, Strongly Agree = 3. However, for the proportional questions, student responses of “I Am Unsure” were coded as NA values.

We grouped student responses to demographic questions into binary categories for LGBTQ+ identity, gender, religion, and race. We were interested in the identities that may similarly respond to stigma with respect to gender and sexuality for each of these categories, so we coded students as LGBTQ+ or Not LGBTQ+; Woman/Nonbinary/Other (hereafter, referred to as Woman/NB) or Man; Religious or Nonreligious/Jewish (hereafter, referred to as NR/J); and Persons Excluded because of their Ethnicity/Race (PEERs) or not (Asai, 2020). We considered treating nonbinary, Jewish, Muslim, and Asian identities as separate categories, but we regrettably were not able to due to small sample sizes. Regarding gender, to retain nonbinary individuals in the analyses, we chose to group women and nonbinary students together, because both groups report experiencing stigma in STEM based on their marginalized gender identities (Sansone and Carpenter, 2020; Casper et al., 2022). We acknowledge that women and nonbinary students likely experience different types of discrimination, however this decision allowed us to retain nonbinary students as part of the LGBTQ+ variable, where their experiences would be contrasted with those of non-LGBTQ+ individuals. Based on the definition of PEER identities, Asian students and white students were grouped to form the “not PEER” group (Asai, 2020). We included religion as a category of interest to control for differences in anti-LGBTQ stigmas across religious identities, identify differences in the effects of our BPAs across religious identities, and ensure that the BPAs do not cause religious students to feel a greater sense of exclusion (Barnes et al., 2021). To compare students with a religious identity that may be associated with anti-LGBTQ stigma with their peers, we grouped all students who identified as Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, or Muslim together and compared them to all nonreligious and Jewish students. This categorization is based on evidence from a systemic review that found increased antitrans prejudice among all participants of all religions except Judaism compared with nonreligious participants (Campbell et al., 2019), and additional findings that support similar trends for sexuality-based anti-LGBTQ stigmas (Cragun and Sumerau, 2015; Westwood, 2022). For clarity, we shortened these categories to “religious” and “NR/J” throughout the text and we want to acknowledge that students may identify as Jewish for either religious or ethnic reasons. We hope that future research will study populations with larger sample sizes of students of other religious identities to untangle the differences between identities within these larger groupings.

We explicitly outline the direction of the shift for each question that indicates the more nuanced and less culturally biased understanding of the concept in Table 1. For the collective analyses of questions in the Sex category, we excluded the question asking students to estimate a proportion from the collective models and summed student responses to all Likert scale questions. The same process was done for the questions in the Sexuality category. A negative shift in the collective models is in line with a more nuanced understanding of sex and sexuality. All Five-Likert-scale responses were summed for each the Belonging in Course (Belonging C1), and Belonging in Biology (Belonging C2) categories; a positive shift in the collective models is in line with a stronger sense of belonging. For questions in the Normativity category, most, but not all, of the questions were phrased such that a shift toward “Strongly Agree” was the intended outcome. Therefore, for the collective model, but not for the individual question models, we reverse-coded the scores of the questions in the Normativity category that favored a shift toward “Strongly Disagree” by multiplying scores by -1 to standardize the direction the scores before summing each student's responses to the questions within this category. We therefore considered a positive shift in the collective model of the Normativity category to be aligned with a more nuanced and less culturally biased understanding.

We used linear models to model precourse survey responses to each question with identity variables as the main effects. We modeled the postcourse survey responses to each question using the main effects of course type (either BPA- or BPA+ course) and identity variables and the interactive effects of course type and identities, while controlling for presurvey responses by adding it as a covariate. We used the model of precourse survey responses to test the hypothesis that student identities affect their understanding of the topic of sex, gender, and sexuality in nonhuman animal behaviors before they enter the class. We used backward stepwise model selection by Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) for each survey question to select the simplest explanatory model. We include LGBTQ+ identity, gender identity, and religion as the identity-related predictors in models of content- and attitude-focused questions. However, because some of our interventions dealt with topics related to historical racism and discrimination, we included the racial identity category (PEER vs. not PEER) as a predictor variable for the sense of belonging questions. We have no reason to assume that a student's racial identity might affect their understanding of concepts related to sex, gender, and sexuality, so we did not include race in the analysis of the conceptual questions. We did not include interactions among identity-related variables as predictors in the models due to a lack of sufficient representation in our population. However, we acknowledge the importance of intersectionality in shaping student's experiences and perceptions, and our results should be interpreted cautiously with this in mind. For postcourse survey questions, we also included the precourse survey response as a predictor variable to account for students’ prior knowledge. AIC model selection on only one question (Normativity Q9) excluded precourse survey responses. To control for multiple hypothesis testing, we used the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure and ranked p values for each identity within each of the content categories (sex, sexuality, normativity) using a false-discovery rate of 0.05 (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). Corrected p values were used to determine significance, and raw p values can be found in the supplement (Supplemental Tables 5 and 6).

RESULTS

Participant Demographics

Of students who participated in the study, 26.5% identified as LGBTQ+, holding identities including gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, asexual, pansexual, nonbinary, aromantic, biromantic, and confused. Additional student demographics are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Survey respondent demographics. Demographics of students by identity category as they were coded in the analyses for the linear models

| Identity category | Identity | Percent of students surveyed |

|---|---|---|

| LGBTQ+ status | LGBTQ+ | 26.5% |

| Not LGBTQ+ | 73.5% | |

| Gender identity | Women/NB | 79.0% |

| Man | 21.0% | |

| Religious affiliation | Religious | 38.5% |

| NR/J | 61.5% | |

| Racial identity | PEER | 25.5% |

| Not PEER | 74.5% |

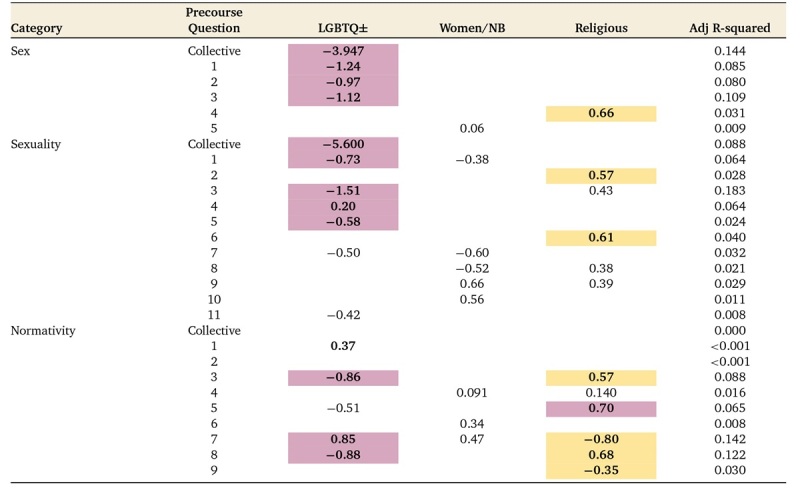

Finding 1: LGBTQ+ and religious student identities predict the foundation of knowledge that undergraduate students bring to an animal behavior course with respect to concepts relating to sex, sexuality, and normativity.

LGBTQ+ students demonstrated prior knowledge that was less influenced by cisheteronormative assumptions about animal behavior than their non-LGBTQ+ peers (Table 3). LGBTQ+ students were more likely than their non-LGBTQ+ peers to demonstrate resistance to strict sex categories (Sex Q1) and a nuanced understanding of sexed physiologies (Sex Q2 & Q3, Table 3). They were also more likely to recognize contextual evolutionary value of homosexual behaviors and nonmonogamy in animals (Sexuality Q1, Q3, and Q5) and to predict a higher rate of homosexuality in animals (Sexuality Q4, Table 3). Further, results indicated that LGBTQ+ students were more likely than their peers to acknowledge the difference between sex and gender (Normativity Q3), and to acknowledge that LGBTQ+ identities and associated behaviors are natural and widespread throughout the animal world (Normativity Q7, Q8, Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Precourse question effects. Results of the linear models for each question on the precourse survey, organized by category: Sex, Sexuality, and Normativity. Blank squares were excluded from the model based on our AIC backward stepwise model selection process. Bolded betas are significant after p value correction with the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure, and colors indicate direction of significance. Purple indicates that the group of interest expressed lesser cisheteronormative assumptions and yellow indicates that the group of interest expressed greater cisheteronormative assumptions than their respective reference group. For each model, the sign of the beta indicating less cisheteronormative assumption is reported in the last column. For the collective models, we summed the Likert scale questions within each category (Sex Q14, Sexuality Q13 and 511, Normativity Q19) after reverse coding the relevant questions. We then analyzed these summative scores with the same procedure as the individual questions after reverse coding the questions. An asterisk indicates that the question was reverse coded in the collective model of that category. Note that McDonald's omega did not support collective analysis of the any category in this table, and CFAs only supported the collective analysis of the Sex category.

|

Gender identity had no effect on students’ prior knowledge across any of the survey questions.

Religious identity had an effect on students’ prior knowledge for eight questions, and in seven of the eight questions religious students were more influenced by cisheteronormative assumptions than their NR/J peers (Table 3). Religious students were more likely than their peers to assume that sex categories implied universal truths about species traits and behaviors (Sex Q4, Table 3), to believe that species that do not transition between sexes have a greater evolutionarily advantage (Sexuality Q2), and that parental care is universal (Sexuality Q6). They were also more likely than their NR/J peers to believe that sex and gender are equivalent (Normativity Q3) and that LGBTQ+ identities and associated behaviors are not natural and are not found in nonhuman animals (Normativity Q7, Q8, Table 3). Religious students were also less likely than their peers to believe that studying the natural world influences their understanding of themselves (Normativity Q9). However, religious students were more likely than their NR/J peers to report that the scientific definition of sex includes social norms, behaviors, and roles (Normativity Q5, Table 3).

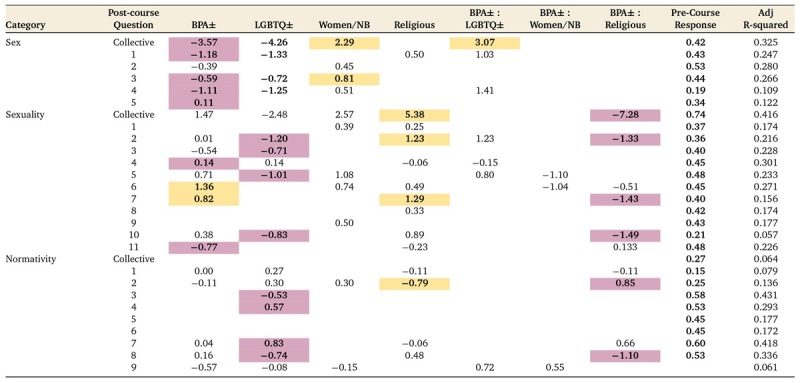

Finding 2a: Students enrolled in the BPA+ course demonstrate higher postcourse knowledge with respect to concepts relating to sex.

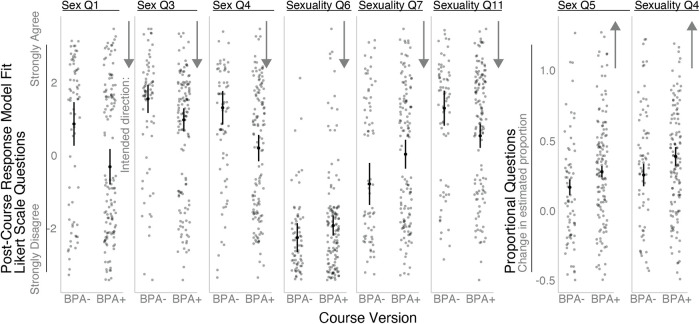

The inclusion of BPA activities in a course (BPA+) had an effect on students’ postcourse responses for eight individual questions (Figure 1): Sex 1, 35, Sexuality 4, 6, 7, and 11. For six of the eight questions, student postcourse responses moved in the intended direction, demonstrating responses that were less influenced by cisheteronormative biases (Table 4; Figure 2). That is, students who took the BPA+ course were more likely than their peers in the BPA- course to demonstrate resistance to strict sex categories (Sex Q1), to demonstrate a nuanced understanding of sexed physiologies (Sex Q3), to assume that sex categories do not imply universal truths about species traits and behaviors (Sex Q4), and to predict a higher proportion of animal species that transition between sexes in their lives (Sex Q5) in their postcourse responses. They were also more likely to predict a higher proportion of animals that exhibit homosexual behaviors (Sexuality Q4) and were less likely to believe that male aggression is universally beneficial (Sexuality Q11). However, for two of the eight questions, student postcourse responses moved in the opposite of the intended direction and demonstrated more cisheteronormative assumptions: students who took the BPA+ course were more likely than their peers in the BPA- course to believe parental care is universal and necessarily beneficial (Sexuality Q6, Q7). Whether students were enrolled in a BPA+ course did not predict their responses to any of the questions assessing assumptions of normativity (Table 4).

FIGURE 1.

Change in survey responses by course type. Box and whisker plots of median, interquartile range, and total range excluding outliers for all questions in which BPA treatment was significant in the model. Plots depict the predicted student's postcourse response based on the linear models to visualize changes in student response scores. Solid black dots indicate predicted means and the lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Gray dots indicate predicted data points based on the raw data. For the top plot of Likert scale questions (Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree), a negative number indicates a shift towards “Disagree,” and a positive number indicates a shift in attitude towards “Agree” after having taken the course. Arrows on the y-axis indicate the intended direction of the intervention, indicating that students shifting in that direction would hold a less cisheteronormative view. For the two plots on the right of proportional questions (0 to 100%), a negative number indicates a shift towards “0%,” and a positive number indicates a shift in attitude towards “100%” after having taken the course. Proportional plots extend into negative numbers even though the actual survey question ranged from 0 to 100% because these numbers are model fits, not true values. Gray points indicate individual survey responses from the raw data, after incorporating effects of other identities in the model.

TABLE 4.

Postcourse question effects. Results of the linear models for each postcourse survey question. Blank squares were excluded from the model based on our AIC backward stepwise model selection process. Bolded betas are significant after p value correction with the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure, and colors indicate direction of significance for identity factors. Purple indicates a modeled effect in the intended direction (indicating that fewer cisheteronormative assumptions were present in student responses) and yellow indicates a modeled effect in the unintended direction (indicating greater cisheteronormative assumptions). For interaction effects, the color code refers to conclusions based on trends inferred from the interaction plots in Figure 2. To determine whether the reference or nonreference group drove patterns of interaction terms, models of significant interactions are presented in Supplemental Figure 1. For each model, the sign of the beta indicating less cisheteronormative assumption is reported in the last column. For the collective models, we summed the Likert scale questions within each category (Sex Q14, Sexuality Q13 and 511, Normativity Q19) after reverse coding the relevant questions. We then analyzed these summative scores with the same procedure as the individual questions after reverse coding the questions. An asterisk indicates that the question was reverse coded in the collective model of that category. Note that McDonald's omega did not support collective analysis of the any category in this table, and CFAs only supported the collective analysis of the Sex category.

|

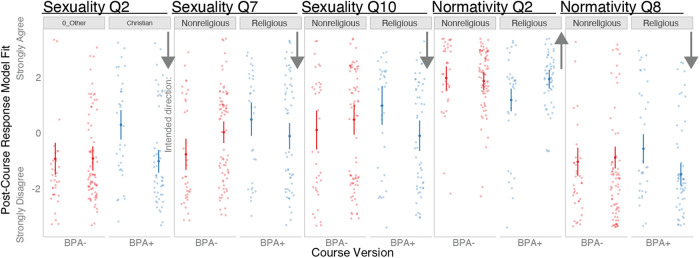

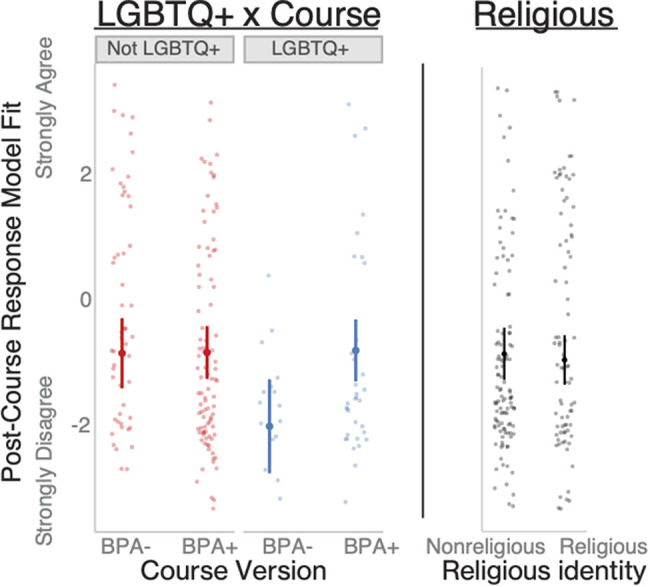

FIGURE 2.

Plots of significant interactions between course and identity variables. Plots depicting model fits for interactive effects of course and identities on postcourse survey responses. We show only the boxplots for terms where the interaction was significant. Blue indicates the identity of interest and red indicates the null identity. Solid dots indicate predicted means and the lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Lighter dots indicate predicted data points based on the raw data. The leftmost plots depict interactions between course type and LGBTQ identity, and the rightmost plots depict interactions between course type and religious identity. All plots depict the values toward “Strongly Disagree” values as negative and the values toward “Strongly Agree” as positive. Faded points indicate individual survey responses from the raw data, after incorporating effects of other identities in the model.

Finding 2b: Regardless of course type, LGBTQ+ students demonstrate knowledge less influenced by cisheteronormative assumptions related to sex, sexuality and normativity, and both Women/NB students and Religious students demonstrate more culturally biased knowledge at the end of the course.

Regardless of the presence or absence of BPAs and accounting for precourse knowledge, LGBTQ+ students consistently demonstrated knowledge that was less influenced by cisheteronormative assumptions than their non-LGBTQ+ peers at the end of the course (Table 4). They were less likely to assume that sex categories were universally applicable (Sex Q1) and were less likely to recognize that sex categories implied universal truths about species traits and behaviors (Sex Q3 and 4; Table 4). They were also more likely to identify the evolutionary value of sexual transitions in animals (Sexuality Q2), of homosexuality (Sexuality Q3), and of nonmonogamy (Sexuality Q5 and Q10; Table 4). LGBTQ+ students also completed the course expressing an understanding of the influence of cultural normativity on scientific studies; they demonstrated a greater understanding that sex and gender do not mean the same thing and that it is important to distinguish between the two (Normativity Q3 and Q4) and that LGBTQ+ identities and associated behaviors are natural and widespread in the animal world (Normativity Q7 and Q8; Table 4).

Gender identity predicted the knowledge that students took away from the course for one question, Sex Q3, and for both of the collective analyses of Sex and Sexuality questions (Table 4). Women/NB students were more likely to apply gender norms to their understanding of sexed physiologies than their peers that identify as men and expressed more cisheteronormative assumptions across the collective Sex and Sexuality questions after accounting for students’ precourse knowledge (Table 4).

Religious identity predicted postcourse knowledge for two Sexuality questions (Q2 and Q7), for one Normativity question (Q2), and for the collective analysis of all Sexuality questions (Table 4). In all instances, religious students left the course with a more cisheteronormative perspective than their NR/J peers, after accounting for students’ precourse knowledge (Table 4). They were less likely than their NR/J peers to recognize contextual evolutionary value of sexual transitions (Sexuality Q2), and more likely to agree that biological parents are better caretakers than nonbiological parents (Sexuality Q7), and to that our cultural biases do not limit our ability to understand the natural world (Normativity Q2; Table 4). They expressed more cisheteronormative knowledge in the collective Sexuality analysis than their NR/J peers (Table 4).

Finding 2c: BPAs were disproportionately effective for religious students.

We found that the BPA intervention disproportionately affected students based on religious identity in their postcourse responses to five questions (Sexuality Q2, Q7, and Q10; Normativity Q2 and Q8) and for the collective score for all Sexuality questions (Table 4). Religious students who took the BPA+ course consistently shifted their perceptions in the intended direction. They were more likely to recognize contextual evolutionary value of sexual transitions, of alternative methods of parental care, and of polyandry in animals than their religious peers who took the BPA- course (Sexuality Q2, Q7, and Q10; Table 4; Figure 2). However, NR/J students who took the BPA+ were more likely to believe that biological parents are better caretakers than nonbiological parents than their NR/J peers in the BPA- course, which is in the opposite direction of our intended outcomes (Sexuality Q7). Religious students who took the BPA+ course were more likely to believe that our cultural biases limit our ability to understand the natural world (Normativity Q2) and to acknowledge that LGBTQ+ identities and associated behaviors are natural and widespread throughout the animal world (Normativity Q8) than their religious peers who took the BPA- course, while course type had no effect on NR/J students (Table 4; Figure 2). Religious students in the BPA+ course shifted in the intended direction for the collective score of all Sexuality questions compared with religious students in the BPA- course, while NR/J students showed no differences between BPA conditions (Table 4; Supplemental Figure 1); however, McDonald's omega and CFA values did not support collective analysis of the Sexuality category.

The interaction of course and either LGBTQ+ identity or gender identity did not significantly predict students’ postcourse responses to any questions (Table 4). However, the collective analysis of all Sex category questions suggested that LGBTQ+ students in the BPA+ course expressed less nuanced views than their LGBTQ+ peers in the BPA- course (Table 4, Sex Collective, Supplemental Figure 1); however, while CFA values did support collective analysis of the Sex category, McDonald's omega did not.

Finding 3: BPAs marginally improve LGBTQ+ students’ sense of belonging in biology.

Religious students entered the course with a lower sense of belonging in the course than their NR/J peers (Belonging C1; Table 5), but no identities demonstrated a significant effect on student sense of belonging in the field of biology (Belonging C2; Table 5). However, after taking this course, the interaction between LGBTQ+ identity and the course type had a near significant effect on students’ sense of inclusion in the field of biology (p = 0.057, Belonging C2; Table 6), with LGBTQ+ students who took the BPA+ course expressing a greater sense of belonging than LGBTQ+ students who took the BPA- course (Figure 3). Religion also had a somewhat near significant effect of students’ sense of inclusion in biology (p = 0.09), but with negligible observable differences in predicted values (Figure 3). Neither gender nor race predicted students’ sense of inclusion in any model (Belonging C1 and C2; Tables 5 and 6).

TABLE 5.

Precourse effects of identity on belonging. Results of the linear models for collective results of precourse survey sense of belonging questions. Blank squares were excluded from the model based on our AIC backward stepwise model selection process. Bolded betas are significant, and colors indicate direction of significance.

| Category | LGBTQ± | Women/NB | Religious | Race (PEER) | Adj R-squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belonging in Course | −0.75 | −0.87 | 0.67 | 0.016 | |

| Belonging in Biology | −0.93 | 0.007 |

TABLE 6.

Postcourse effects of identity on belonging. Results of the linear models for collective results of postcourse survey sense of belonging questions. Blank squares were excluded from the model based on our AIC backward stepwise model selection process. Bolded betas are significant, and colors indicate direction of significance. Purple indicates a modeled effect in the intended direction (indicating that fewer cisheteronormative assumptions were present in student responses) and yellow indicates a modeled effect in the unintended direction (indicating greater cisheteronormative assumptions). For effects of a single identity, the color code refers to the identity or treatment of interest (BPA+, LGBTQ+, Women/NB, or Religious) and for interaction effects, the color code refers to conclusions based on trends inferred from the interaction plots in Figure 2. To determine whether the reference or non-reference group drove patterns of interaction terms, models of significant interactions are presented in Figure 3.

| Category | BPA± | LGBTQ± | Women/NB | Religious | Race (PEER) | BPA± x LGBTQ± | BPA±: Women/NB | BPA±: Religious | BPA± x Race (PEER) | Pre-Course Response | Adj R-squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belonging in Course | 0.638 | 0.096 | |||||||||

| Belonging in Biology | −1.37 | −1.34 | −1.60 | 2.66 | 1.86 | 0.347 | 0.152 |

FIGURE 3.

Effects of LGBTQ+ Identity, Course Type, and Religious Identity on Student Sense of Belonging. Model fit of postcourse sense of belonging in the field of biology by BPA treatment and LGBTQ+ identity, and by religious identity. A more negative number indicates a lower sense of belonging and a more positive number indicates a higher sense of belonging in the field of biology.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to investigate the effects of a curriculum addition on LGBTQ+ students' sense of belonging, and on all students’ understanding of concepts in animal behavior related to sex, gender, and sexuality. Our study found largely positive effects of the curriculum addition. We demonstrated many beneficial effects, particularly for both the educational growth of religious students and the inclusion of LGBTQ+ students. Our efforts also demonstrate that an increase in LGBTQ+ perspectives in biology curricula poses little to no risk of alienating religious students. We hope that these findings encourage other educators to incorporate similar materials in their classrooms. We have provided full access to the materials that we developed for use by other educators who are interested in increasing sense of belonging for LGBTQ+ students in the classroom in the Supplemental Material. These materials were designed to supplement an existing curriculum and can be appended to other curricula with few changes. Our curriculum development process involved many early career scientists of various identities as well as experienced experts in the field, and we sought to highlight voices of marginalized scientists in our field. Similar methods may be effective for developing inclusive curricula across disciplines and other social identities, but further research is required.

Students Differ in the Knowledge that they Bring to and Take from the Animal Behavior Classroom

We found that LGBTQ+ students are more likely to enter undergraduate biology courses with more nuanced and complex understandings of sex, gender, and sexuality than their non-LGBTQ+ peers. This novel finding supports longstanding theoretical work that has advocated for the acknowledgement of students’ past experiences and prior knowledge within the academic context (Lemke, 2001) by quantifying the differences in student perceptions on issues related to their lived experiences. We also showed that, regardless of the presence or absence of BPAs, student identities predicted what knowledge they took from the class for concepts related to sex, gender, and sexuality. Not only are students entering the classroom with different knowledge from their lived experiences, but that knowledge shapes how they engage with classroom materials. Our findings support the perspectives presented by authors reflected in our BPAs, who argue that LGBTQ+ and other marginalized perspectives in the field of animal behavior provide unique and valuable contributions because the lived experiences of scientists of different identities prepare them to ask different questions than their non-LGBTQ+ peers (Bagemihl, 1999; Roughgarden, 2013; Giurfa and de Brito Sanchez, 2020; Jaffe et al., 2020; Lee, 2020; Tang-Martinez, 2020a). For example, before taking the course, LGBTQ+ students were more likely to disagree with statements that devalued the role of homosexual behaviors in evolutionary contexts than their peers. This quantitative finding helps to explain patterns found in qualitative studies of LGBTQ+ students’ sense of belonging in biology, which have documented friction between the lived experiences of LGBTQ+ students and curricular content (Casper et al., 2022).

Before engaging with the animal behavior course, religious students demonstrated a less nuanced understanding of both sex and normativity than their NR/J peers. To our knowledge, this is the first study to conceptualize how religious university students perceive cultural norms that directly impact scientific studies and their perceptions of language as it relates to sex and gender. Our findings support prior research that suggests that religious beliefs can correlate with more traditional gender and sexuality ideologies (Eliason et al., 2017; Rigo and Saroglou, 2018; Huberman, 2023). Notably, examining only postcourse knowledge and controlling for precourse knowledge, more differences emerged between religious and NR/J students specifically with regard to sexuality, suggesting that their prior education and lived experiences influenced the way that they interacted with the course content. The mechanisms underlying this trend are likely complex, culturally specific, and intersectional with many other social identities (Schnabel et al., 2022). However, religious identity also predicts student acceptance of other biological concepts such as evolution (Glaze et al., 2014; Hill, 2014; Rissler et al., 2014), and our approach to teaching LGBTQ+ related concepts followed several guidelines outlined for fostering the acceptance of evolution in religious students (Barnes and Brownell, 2017).

Efforts to Expand Course Content had Largely Positive Impacts on Student Learning, and the Effects Differed Across Identities

The addition of the BPAs had many positive effects on students’ understanding of sex, gender, and sexuality regardless of identity. The addition of the BPAs improved student abilities to critically engage with cultural biases and to adjust their normative assumptions about the world in a limited capacity. This was encouraging in light of research demonstrating that presenting undergraduates with content or facts is not particularly effective in changing their perceptions of controversial biology topics (Caplan, 2011; Hochschild and Einstein, 2015).

We had hoped that these activities would increase students’ likelihood of agreeing with statements like, “The language that we use affects our ability to understand the natural world,” and “Our cultural biases limit our ability to understand the natural world,” or even, “Sex and gender mean the same thing.” For some, like the first two statements, our BPAs had no impact. But for the third statement, the addition of our BPAs improved student scores. Given that some students have noted their peers use scientific rational to justify their anti-LGBTQ+ beliefs (Cech and Waidzunas, 2011), curricular changes like ours may have positive effects on the campus climate for LGBTQ+ students. Unfortunately, we did observe that students left the BPA+ course with more culturally biased understandings on topics related to parental care. None of our Broadening Perspectives Activities directly addressed this concept, and we hope that future iterations of this course will seek to address this misconception.

Both before and after the course, and regardless of the integration of BPAs, non-LGBTQ+ students lagged behind their LGBTQ+ peers on expressing nuanced views of sex, gender, and sexuality in animal behavior. This demonstrates the great need for new approaches to foster diverse understandings of sex, gender, and sexuality among non-LGBTQ+ students in biology courses.

The effect of gender identity on postcourse student knowledge was unexpected. Women/NB demonstrated a less nuanced understanding of the variation in sexed physiologies across animals than their peers who identified as men. Gender did not have an effect on student learning for any of the other concepts, many of which are more directly related to LGBTQ+ identities. It is interesting that this was the only difference that we uncovered, because STEM fields with higher percentages of women are also likely to have a higher degree of openness to LGBTQ+ scientists, suggesting some difference between women and men with respect to LGBTQ+ issues (Yoder and Mattheis, 2016).

The BPAs interacted with religious identities in consistently positive ways. As a result of the BPAs, religious students demonstrated a decrease in the effect of cultural biases on their understanding of the value of sexual transitions in the animal world, alternative methods of parental care, as well as of polyandry, which aligned with our intended outcomes. Interestingly, religious students overall were less likely than their NR/J peers to believe that our cultural biases do not limit our ability to understand the natural world. Further, religious students who took the BPA+ course were more likely than their religious peers in the BPA- course to express this belief, demonstrating that the BPAs ameliorate but do not fully resolve identity-based discrepancies in critical analyses.

Efforts to Improve Curricula had Positive Effects on Student Sense of Belonging, with no Negative Effects on Any Studied Identity

LGBTQ+ students who took the BPA- course had a decreased sense of belonging in the field of biology compared with their LGBTQ+ peers who took the BPA+ course, and we observed no differences between non-LGBTQ+ students who took either course or LGBTQ+ students who took the BPA+ course. These findings align with the feedback from undergraduate students that inspired these course changes: the original course decreased LGBTQ+ student sense of belonging in the field of biology. Many studies have documented the challenges faced by LGBTQ+ undergraduates in STEM (Greathouse et al., 2018; Hughes, 2018; Miller and Downey, 2020; Hughes and Kothari, 2023; Maloy et al., 2022; Casper et al., 2022, among others), and others have demonstrated positive cultural changes to improve LGBTQ+ student experiences. To our knowledge, this is the first quantitative study to demonstrate the negative effects of an undergraduate biology curriculum on LGBTQ+ student sense of belonging, and it is also the first study to demonstrate a clear path to ameliorate these negative curricular effects.

Our survey found that religious identity interacts uniquely with our novel curricular content, which is of particular note because we also showed that religious students enter the course with a decreased sense of belonging in the course compared with their peers. With our BPAs, we aimed to maximize the benefits for LGBTQ+ students while minimizing any potential negative implications for students of other identities. We showed not only no negative implications for religious students, but many positive outcomes as religious students in particular developed their biological frameworks for concepts related to sex, gender, and sexuality in the field of animal behavior. Given the discrepancies that have been observed between religious and nonreligious students in biology (Barnes and Brownell, 2017), this finding shows that curricular interventions that amplify marginalized voices have positive educational effects for students of other, potentially conflicting, marginalized identities.

Our surveys found no effect of gender or racial identities on students’ sense of belonging. This is surprising, because other studies have found that students of marginalized identities along these axes do feel excluded from STEM (Rodriguez and Blaney, 2021). Our course was entirely online, and the majority of the students in our course were completing their entire undergraduate studies online. We know little about the effect of an online curriculum compared with an in-person curriculum on student sense of inclusion, and it could be that students who are entirely online experience less identity-based stigma. For in person courses, transgender and nonbinary students cite both exclusionary curriculum practices alongside exclusionary cultural norms as reasons for their low sense of belonging in biology courses (Casper et al., 2022). It is unknown whether those same stigmatizing experiences occur at a similar rate for students in an online curriculum. This indicates a potentially rich avenue of research into expanding access to and interest in STEM fields.

Context of an Effective Intervention