Summary

Nanobodies are the products of an intriguing invention in the evolution of immunoglobulins. This invention can be traced back approximately 45 million years to the common ancestor of extant dromedaries, camels, llamas, and alpacas. Next to conventional heterotetrameric H2L2 antibodies, these camelids produce homodimeric nanobody‐based heavy chain antibodies, composed of shortened heavy chains that a lack the CH1 domain. Nanobodies against human target antigens are derived from immunized animals and/or synthetic nanobody libraries. As a robust, highly soluble, single immunoglobulin domain, a nanobody can easily be fused to another protein, for example to another nanobody and/or the hinge and constant domains of other immunoglobulins. Nanobody‐derived heavy chain antibodies hold promise as a new form of immunotherapeutics.

Keywords: heavy‐chain antibody, immunoglobulin, immunotherapeutic, nanobody

1. STRUCTURE OF NANOBODY‐BASED HEAVY CHAIN ANTIBODIES

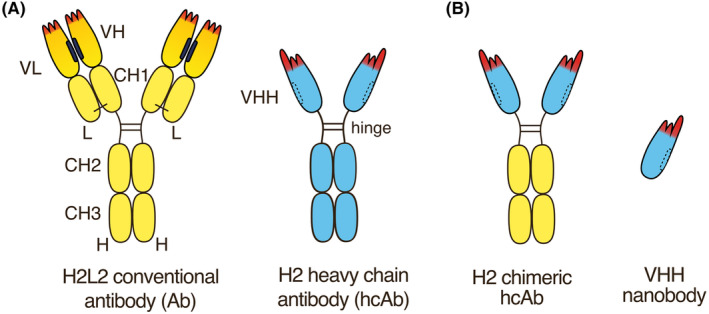

Homodimeric H2 heavy chain antibodies lack the CH1 domain and do not contain light chains (Figure 1). Such antibodies occur naturally in members of the camelid lineage, including llamas, alpacas, dromedaries, and camels. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 The heavy chain of such antibodies typically is composed of a single, highly soluble variable immunoglobulin domain (VHH), connected via a hinge region to two constant immunoglobulin domains (CH2 and CH3) (Figure 1A). The two chains are linked by disulfide bridges within the hinge and typically carry a single N‐linked glycosylation site in the CH2 domain. Nanobodies correspond to the VHH domain of such camelid heavy chain antibodies.

FIGURE 1.

Nanobody‐based heavy chain antibodies. (A) Naturally occurring camelid homodimeric H2 heavy chain antibodies lack the CH1 domain and do not contain light chains. The heavy chain typically contains a single, highly soluble variable immunoglobulin domain (VHH), connected via a hinge region to two constant immunoglobulin domains (CH2 and CH3). The two chains are linked by disulfide bridges within the hinge. Nanobodies correspond to the VHH domain of camelid heavy chain antibodies. The specificity of an antibody is determined by the three complementarity determining regions (CDR1‐CDR3) (in red). The amino acid sequence of the CDR3 is newly encoded during B cell development by V‐D‐J recombination. The CDR3 of VHHs often are longer than those of conventional VH domains. The hydrophobic interface of VH and VL domains in conventional antibodies (in black) is replaced by hydrophilic residues in VHH domains (dashed lines). (B) Chimeric H2 heavy chain antibodies can readily be generated by genetic fusion of a VHH to the hinge and Fc‐domains of human IgG1 or any other Ig‐isotype.

As in case of conventional H2L2 antibodies, heavy chain antibodies are produced during natural immune responses by B cells that undergo somatic hypermutation and affinity maturation. 2 , 3 , 4 The specificity of heavy chain antibodies is determined solely by V‐D‐J recombination of the IgH locus in the bone marrow. The specificity and binding strength are fine‐tuned in subsequent immune‐responses by somatic mutations in proliferating B cell clones. Fusion of a camelid VHH to the hinge and Fc domains of another species yields chimeric heavy chain antibodies (Figure 1B).

2. THE EVOLUTIONARILY HISTORY OF NANOBODY‐BASED HEAVY CHAIN ANTIBODIES

V‐D‐J recombination can be traced back to the last common ancestor of bony and cartilaginous fish. 5 Antibodies are made in response to infections in all extant mammals, reptiles, birds, fish, and sharks, but not by insects, worms, or shellfish or jellyfish. The origin of heavy chain antibodies can be traced back to the common ancestor of llamas, alpacas, dromedaries, and camels (Table 1). Gene duplication has led to the diversification of a variety of immunoglobulin isotypes, including the common IgM, IgG, IgA, and IgE isotypes of mammals. Humans for example carry genes for one IgM, four IgG, two IgA, one IgE, while rabbits carry up to 15 IgA genes. Llamas and dromedaries typically carry genes for three IgG, two IgA, and one IgE isotype.

TABLE 1.

Evolutionary history of nanobody‐based heavy chain antibodies.

| GYBP | Event |

|---|---|

| 20 | Formation of earth and moon |

| 18 | First single celled organisms |

| 6 | First eukaryotes |

| 4 | First multicellular eukaryotes |

| 2 | V‐D‐J recombination in a sea‐urchin like marine animal |

| 1.8 | V‐D‐J‐recombination and antibodies is well established in fish |

| 1.4 | First amphibian land vertebrates |

| 0.3 | Chixculub impact and subsequent diversification of mammals |

| 0.2 | Inactivation of an IgG CH1 exon in camelid ancestor and subsequent diversification of V exons |

| 10−9 | Recombinant nanobody‐based heavy chain antibodies |

Note: A GY is the time required for the sun to orbit Sagittarius A* in the center of the Milky Way galaxy (~230 million years).

Abbreviation: GYBP, galactic years before present.

Approximately 45 million years ago, a mutation occurred in a camelid ancestor that inactivated splicing of the exon encoding the CH1 domain in one of the IgG genes. 2 , 6 This abrogated the capacity of immunoglobulins derived from this locus to pair with light chains. Comparable spontaneous or engineered mutations in mice and humans typically result in the formation of “sticky” heavy chain antibodies that lack the CH1 domain and light chains. The tendency of such heavy chain antibodies to aggregate accounts for the associated pathology “heavy chain disease.” Within the last 45 million years, additional mutations have accumulated in members of the camelid lineage that increase the solubility and function of heavy chain only antibodies (Table 2). Advantageous features of these mutations presumably were subject to natural selection, most likely by improved resistance to infectious agents.

TABLE 2.

Evolutionary changes in the camelid heavy chain locus.

| Locus | Event | Selective advantage |

|---|---|---|

| V‐genes | Hydrophylic amino acids replace hydrophobic amino acids in FR2 | Better solubility |

| V‐genes | Extra cysteine residue flanking CDR1 or CDR2 | Disulfide bond to CDR3 stabilizes paratope |

| CDR3 | Extra cysteine residue | Disulfide bond to CDR1 or CDR2 stabilizes paratope |

| CDR3 | Length extension | Binding to crevices in antigens |

| CDR3 | Flap covering the former interface to VL | Prevents binding of the light chain |

| CH1 | Splice site mutation | Formation of H2 antibodies |

| Hinge | Length extension | Increased flexibility |

Pairing of the variable domains of heterotetrameric antibodies is facilitated by hydrophobic amino acid residues at the interface of the VH and VL domains (Figure 1A). These hydrophobic patches presumably aid in orienting the VH and VL for correct binding to the target antigen. The hydrophobic patch in the VH domain corresponds roughly to the framework region 2 (FR2). 2 , 7 In the absence of a partnering VL domain, many VH domains show a certain stickiness or tendency to aggregate. A subset of VH genes in the camelid lineage acquired substitutions that mediate increased hydrophilicity and solubility in the absence of a light chain. These V domains are typically found in heavy chain antibodies and have therefore been named VHH domains (VH domains of heavy chain antibodies). V‐domain encoding exons in the IgH locus of extant camelids typically encompass a mixture of genes for VH domains with a hydrophobic interface and for VHH domains with a hydrophilic interface. V‐D‐J recombination during B cell development in the bone marrow leads to random association of a VH or VHH domain with a D and a J element. Heavy chain antibodies found in the serum of camelids typically contain VHH domains and only rarely VH domains, whereas conventional H2L2 antibodies contain VH but only rarely VHH domains. This, presumably, is the result of selection of stable immunoglobulin formats over the unstable formats such as heavy chain antibodies containing a VH domain and conventional H2L2 immunoglobulins containing a VHH domain.

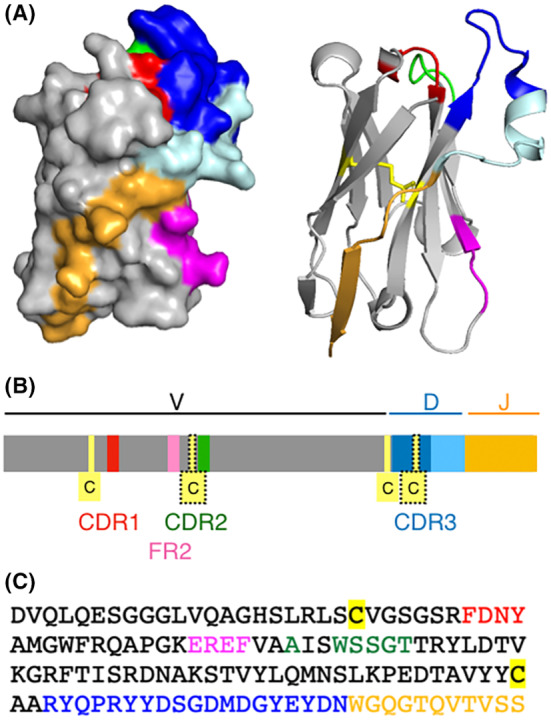

Figure 2 illustrates the structural features of a prototypical VHH domain, the CD38‐specific NbMU551 that was generated in our lab. 8 , 9 The V‐gene encodes the first 90 amino acid residues (gray), the D‐element encodes the CDR3 (blue), and the J‐element encodes the last β‐strand in frame work region 4 (orange) (Figure 2A–C). The region encoded by the V‐gene includes CDR1 (red), CDR2 (green), and the hydrophilic patch (magenta) in FR2 that accounts for excellent solubility of VHH domains.

FIGURE 2.

Structural features of nanobody MU551, a prototype llama VHH. 3D models (A), schematic (B), and amino acid sequence (C) of the CD38‐specific nanobody MU551 (pdb code 5f1o). Regions encoded by V, D, and J genes are colored gray, blue, and orange, respectively. The canonical cysteine residues that form a disulfide bond connecting the two β‐sheets of the immunoglobulin fold are highlighted in yellow. An extra pair of cysteine residues found in approximately one third of llama VHHs is shown with dotted frames. The complementarity determining regions are in red (CDR1), green (CDR2), and blue (CDR3). The CDR3 region is encoded by the D‐element and nucleotides inserted at the V‐D and D‐J junctions. The C‐terminal part of the CDR3 (light blue) often forms a sort of “flap” that folds over onto a side of the VHH that corresponds to the upper half of the interface with the light chain in conventional antibodies. In the lower part of this side of the VHH domain, hydrophilic amino acid residues usually replace hydrophobic residues contained in VH elements of conventional H2L2 antibodies. This region of framework region 2 (FR2) is indicated in magenta.

A subset of VHH encoding exons has the additional peculiarity of encoding a non‐canonical cystein residue, flanking either the CDR1 (in camels and dromedaries), or the CDR2 (in llamas and alpacas) (Figure 2B residues in dotted frames). 2 Approximately two thirds of mature heavy chain antibodies found in the serum of camels and dromedaries carry an extra disulfide bond linking this cysteine to a second cysteine residue in the CDR3. Similarly, roughly one third of heavy chain antibodies found in llamas or alpacas contain this extra pair of cysteine residues. An extra disulfide bond linking these cysteines is thought to stabilize long CD3 regions. Crystal structures of numerous VHH domains containing elongated CDR3 reveal a sort of flap derived from the C‐terminal end of the CDR3 that reaches over and covers the FR2 that would form the interface to the VL domain in a conventional antibody (Figure 2A–C, light blue). This flap sterically prevents association of the VHH domain with a VL‐domain.

3. SELECTION OF NANOBODIES AGAINST POTENTIAL THERAPEUTIC TARGETS

Nanobodies directed against human target antigens typically are selected from immunized animals and/or from synthetic libraries. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 Immunization induces clonal expansion and somatic hypermutation during the antibody response. Repeated immunization therefore leads to an expansion of antigen‐specific B cell clones and to improved affinities of target‐specific antibodies produced by these cells.

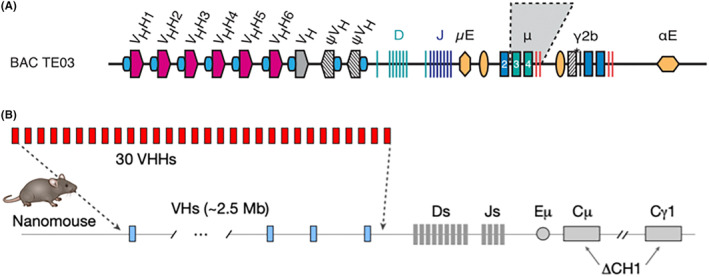

Housing and husbandry of large camelids is more cumbersome than that of small rodents. Moreover, genetic tools established in mice and rats are not available in camelids. To facilitate nanobody discovery from immunized animals, we and others have developed transgenic mice that produce nanobody‐based heavy chain antibodies (Figure 3). 14 , 15

FIGURE 3.

Transgenic Mice that produce nanobody‐based heavy chain antibodies. (A) The LamaMouse was generated by integrating a bacterial artificial chromosome carrying an engineered llama IgH locus into JHT mice that carry an inactivated endogenous IgH locus. LamaMice exclusively produce llama IgM and IgG heavy chain antibodies. The V‐domain of LamaMouse heavy chain antibodies contains a CDR3 and a FR4 encoded by llama D and J elements (regions highlighted in blue and orange in Figure 2). (B) The NanoMouse was generated by replacing the endogenous VH‐encoding exons in the mouse IgH locus with a subset of 30 VHH encoding exons from llamas, dromedaries and alpacas. The CH1 exons of mouse IgM and IgG1 loci were inactivated. The CH1 exons were left intact in IgD, IgG2, IgG3, IgA, and IgE loci. The V‐domain of NanoMouse heavy chain antibodies contains a CDR3 and a FR4 encoded by mouse D and J elements (regions highlighted in blue and orange in Figure 2).

Our own LamaMouse was generated at the UKE by random integration of a bacterial artificial chromosome carrying an engineered llama IgH locus into JHT mice that carry an inactivated endogenous IgH locus. 14 LamaMice exclusively produce llama IgM and IgG heavy chain antibodies (Figure 3A). The D and J elements encoding the CDR3 and FR4, respectively, in these mice are derived from llama (blue and orange regions shown in Figure 2). Hinge and Fc domains of IgG heavy chain antibodies are also derived from llama genes in LamaMice.

The NanoMouse was generated in the Casellas lab at the NIH using Crispr‐Cas9 technology to replace a 2.5 MB gene fragment in the mouse IgH locus by a subset of 30 VHH genes from llamas, dromedaries, and camels 15 (Figure 3B). The CH1 exons of the endogenous IgM and IgG1 loci were deleted, but left intact in the genes encoding IgD, IgG2, IgG3, IgA, and IgE. The NanoMouse recombines camelid V genes with murine D and J elements (corresponding, respectively, to the gray, blue, and orange regions shown in Figure 2). Hinge and Fc regions of IgG heavy chain antibodies are also derived from mouse genes in NanoMice.

Both, protein and cDNA‐immunization have been used to generate nanobodies against a plethora of potential therapeutic human targets, including membrane and secretory proteins of immune cells and tumor cells. 3 , 4 , 16 Our own lab has pioneered cDNA immunization of llamas, alpacas, and LamaMice to raise nanobodies against ecto‐enzymes, purinergic receptors, and other immune cell surface proteins including ARCT2, CD38, CD39, CD73, P2X7, and CLEC9a (Table 3). 8 , 10 , 14 , 17 , 18 , 20 , 21 cDNA immunization ensures that the target antigen is produced in native confirmation by the cells of the immunized animal. 10 The resulting target specific nanobodies thus bind to the respective native membrane protein as expressed on the surface of immune and/or tumor cells. We have also used conventional protein immunization to raise nanobodies against human and mouse immunoglobulin isotypes, bacterial toxins and viral proteins (Table 3). 23 , 24 , 26

TABLE 3.

Nanobodies generated from immunized camelids and LamaMice at the UKE.

| Animal | Immunogen | Target | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Llama | cDNA | ARTC2.2 | [17] |

| Llama | cDNA | CD38 |

[8] [9] |

| Llama | cDNA | P2X7 |

[18] [19] |

| Alpaca | cDNA | CD39 |

[20] [21] |

| Alpaca | cDNA | CD73 | [22] |

| Llama | Protein | CDTa and CDTb | [23] |

| Llama | Protein | SpvB | [24] |

| Dromedary | Protein | ToxA and ToxB | [25] |

| Dromedary | Protein | HIV env gp120 | [26] |

| LamaMouse | Protein | SARS‐CoV2 Spike protein | [14] |

| LamaMouse | Protein | AAV8, AAV9 capsid proteins | [14] |

| LamaMouse | Protein | IgE, IgG2c | [14] |

| LamaMouse | cDNA | CLEC9a | [14] |

4. REFORMATTING OF NANOBODY‐BASED HEAVY CHAIN ANTIBODIES

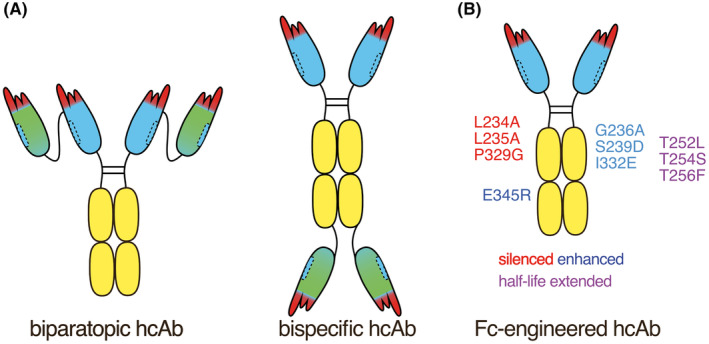

For therapeutic applications, nanobody‐based heavy chain antibodies can be used in similar formats as human antibodies. 23 , 24 , 26 To this end, a VHH is commonly fused genetically to the hinge, CH2, and CH3 domains of human IgG1 (Figure 1B). Similarly, a nanobody can be fused to any other immunoglobulin isotype, including IgM, IgA, and IgE, provided that the CH1 domain is omitted. The VHH can be fused to a second VHH to generate either biparatopic H2 heavy chain antibodies that recognize two epitopes on the same target antigen or bispecific H2 heavy chain antibodies that recognize two distinct proteins. Bispecific H2 heavy chain antibodies can also be generated by fusing the second VHH to the C‐terminus of the heavy chain (VHH‐Fc‐VHH) (Figure 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Structure of nanobody‐based heavy chain and chimeric antibodies. (A) The VHH can be fused to a second VHH to generate either biparatopic H2 heavy chain antibodies that recognize two epitopes on the same target antigen or bispecific H2 heavy chain antibodies that recognize two distinct proteins. Bispecific H2 heavy chain antibodies can also be generated by fusing the second VHH to the C‐terminus of the heavy chain (VHH‐Fc‐VHH). (B) Established Fc‐engineering can be used to silence or enhance the function of nanobody‐based heavy chain antibodies. For example, mutations in the Fc region that silence effector functions of human IgG1are indicated in red, that is, LALAPG. Mutations that enhance Fc‐mediated effector function are indicated in blue, that is, GASDIE which enhances ADCC (antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity) and E345R which enhances CDC (complement dependent cytotoxicity). Mutations that increase half‐life in vivo are indicated in purple, that is, TLTSTF.

Because of their smaller size (75kD vs. 160kD) nanobody‐based human IgG1 heavy chain antibodies may penetrate tumor and inflamed tissues more efficiently than the larger human IgG1 antibodies. 16 , 27 For example, in a mouse model of systemic human myeloma, we found that CD38‐specific nanobody‐based heavy chain antibodies performed as well as or better than daratumumab, the state‐of‐the‐art human IgG1 monoclonal antibody. 28

Established Fc‐engineering technology can readily be adapted to enhance or silence the effector functions of nanobody‐based heavy chain antibodies (Figure 4B; Table 4). For example, the substitution of a glutamic acid residue either in the CH2 domain by arginine (E345R) enhances hexamerization of IgG1 heavy chain antibodies bound to a target cell surface protein. 33 , 34 This enhances binding of C1q and subsequent activation of the complement cascade and CDC. Conversely, introduction of the D265A or the LALAPG mutations abrogates binding to both, C1q and Fc‐recepotrs on NK‐cells, thereby silencing CDC and ADCC. 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 Mutation of the binding epitope for the neonatal Fc‐receptor in turn prolongs the in vivo half‐life of IgG1 heavy chain antibodies. 37 , 38

TABLE 4.

Fc‐engineering of nanobody‐based heavy chain antibodies.

5. THERAPEUTIC USE OF NANOBODY‐BASED HEAVY CHAIN ANTIBODIES

For therapeutic purposes, nanobody‐based heavy chain antibodies routinely are administered systemically by intravenous, intraperitoneal, or subcutaneous injection.

In order to maintain an adequate dose of the therapeutic heavy chain antibody, such injections need to be repeated regularly, for example, at weekly intervals. As an alternative to repeated injections, VIP technology (vectored immuoprophylaxis) 39 can be used to induce and maintain endogenous production of heavy chain antibodies. 38 We have shown that a single intramuscular injection of a recombinant adenoassociated viral (AAV) vector encoding an antagonistic P2X7‐blocking heavy‐chain antibody led to sustained production and systemic blockade of P2X7 for several months after injection. This resulted in therapeutic benefit in mouse models of lymphoma and colitis. 22 , 40

Currently, three nobody based therapeutics have been granted approval for clinical use (Table 5). Neither of these are in a heavy chain antibody format. Caplacizumab consists of two identical von Willebrand‐factor (vWF)‐specific nanobodies fused by a flexible peptide linker to a homodimer. 41 Ozoralizumab consists of two identical TNFα‐specific nanobodies fused by peptide linkers to a third, centrally located albumin‐specific nanobody. 43 And ciltacabtagene consists of two different BCMA‐specific nanobodies fused to one another and to the transmembrane and cytosolic domains of a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR). 42 T cells expressing this biparatopic CAR show remarkable therapeutic efficacy against multiple myeloma.

TABLE 5.

Nanobody therapeutics with clinical approval.

In an order to reduce the risk of inducing antibodies directed against a nanobody‐based heavy chain antibody (anti‐drug antibody [ADA], anti‐ therapeutic antibody [ATA]), it is possible to “humanize” the framework regions of the VHH domain, for example, by replacing divergent amino acids with residues commonly found in human VH domains. 44 , 45 , 46 However, particular care needs to be taken to maintain the natural high solubility of the VHH domain, that is, to avoid introducing the natural stickiness of a human VH domain during humanization of camelid V‐domain.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Heavy chain antibodies are the product of an intriguing invention in the evolution of immunoglobulins, 45 million years ago in the camelid lineage. Nanobodies have been raised against numerous potential therapeutic targets, including cell surface and secretory proteins. Chimeric nanobody‐based human and mouse IgG heavy chain antibodies have shown benefit in several pre‐clinical models of oncology and inflammation. Nanobody‐based heavy chain antibodies thus hold promise as a new generation of human immunotherapeutics.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

FKN is coinventor on patents of LamaMice and target‐specific nanobodies. According to German law, FKN receives a share of licensing revenues from these patents via MediGate GmbH, a 100% subsidiary of the University Medical Center Hamburg Eppendorf.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank the members of my lab at the UKE and all of my collaborators for fruitful ideas and discussions. People like you are what makes science fun. Work in my lab on nanobody‐based heavy chain antibodies has been funded by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, BMBF, DAAD, Deutsche Krebshilfe, Eranet, COST, Werner Otto Stiftung, Sander Stiftung, and Hamburger Krebsgesellschaft. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Koch‐Nolte F. Nanobody‐based heavy chain antibodies and chimeric antibodies. Immunol Rev. 2024;328:466‐472. doi: 10.1111/imr.13385

This article is part of a series of reviews covering Effector Functions of Antibodies in Health and Disease appearing in Volume 328 of Immunological Reviews.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hamers‐Casterman C, Atarhouch T, Muyldermans S, et al. Naturally occurring antibodies devoid of light chains. Nature. 1993;363:446‐448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Muyldermans S. Nanobodies: natural single‐domain antibodies. Annu Rev Biochem. 2013;82:775‐797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ingram JR, Schmidt FI, Ploegh HL. Exploiting Nanobodies' singular traits. Annu Rev Immunol. 2018;36:695‐715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wesolowski J, Alzogaray V, Reyelt J, et al. Single domain antibodies: promising experimental and therapeutic tools in infection and immunity. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2009;198:157‐174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sun Y, Huang T, Hammarstrom L, Zhao Y. The immunoglobulins: new insights, implications, and applications. Annu Rev Anim Biosci. 2020;8:145‐169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Achour I, Cavelier P, Tichit M, Bouchier C, Lafaye P, Rougeon F. Tetrameric and homodimeric camelid IgGs originate from the same IgH locus. J Immunol. 2008;181:2001‐2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bannas P, Hambach J, Koch‐Nolte F. Nanobodies and nanobody‐based human heavy chain antibodies As antitumor therapeutics. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fumey W, Koenigsdorf J, Kunick V, et al. Nanobodies effectively modulate the enzymatic activity of CD38 and allow specific imaging of CD38(+) tumors in mouse models in vivo. Sci Rep. 2017;7:14289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li T, Qi S, Unger M, et al. Immuno‐targeting the multifunctional CD38 using nanobody. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eden T, Menzel S, Wesolowski J, et al. A cDNA immunization strategy to generate nanobodies against membrane proteins in native conformation. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fridy PC, Li Y, Keegan S, et al. A robust pipeline for rapid production of versatile nanobody repertoires. Nat Methods. 2014;11:1253‐1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McMahon C, Baier AS, Pascolutti R, et al. Yeast surface display platform for rapid discovery of conformationally selective nanobodies. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2018;25:289‐296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zimmermann I, Egloff P, Hutter CA, et al. Synthetic single domain antibodies for the conformational trapping of membrane proteins. elife. 2018;7:e34317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eden T, Schaffrath AZ, Wesolowski J, et al. Generation of nanobodies from transgenic 'LamaMice' lacking an endogenous immunoglobulin repertoire. Nat Commun. 2024;15:4728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xu J, Xu K, Jung S, et al. Nanobodies from camelid mice and llamas neutralize SARS‐CoV‐2 variants. Nature. 2021;595:278‐282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sheridan C. Ablynx's nanobody fragments go places antibodies cannot. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35:1115‐1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koch‐Nolte F, Reyelt J, Schossow B, et al. Single domain antibodies from llama effectively and specifically block T cell ecto‐ADP‐ribosyltransferase ART2.2 in vivo. FASEB J. 2007;21:3490‐3498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Danquah W, Meyer‐Schwesinger C, Rissiek B, et al. Nanobodies that block gating of the P2X7 ion channel ameliorate inflammation. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:366ra162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stahler T, Danquah W, Demeules M, et al. Development of antibody and nanobody tools for P2X7. Methods Mol Biol. 2022;2510:99‐127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Menzel S, Duan Y, Hambach J, et al. Generation and characterization of antagonistic anti‐human CD39 nanobodies. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1328306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brauneck F, Seubert E, Wellbrock J, et al. Combined blockade of TIGIT and CD39 or A2AR enhances NK‐92 cell‐mediated cytotoxicity in AML. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:12919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Demeules M, Scarpitta A, Hardet R, et al. Evaluation of nanobody‐based biologics targeting purinergic checkpoints in tumor models in vivo. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1012534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Unger M, Eichhoff AM, Schumacher L, et al. Selection of nanobodies that block the enzymatic and cytotoxic activities of the binary Clostridium difficile toxin CDT. Sci Rep. 2015;5:7850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Alzogaray V, Danquah W, Aguirre A, et al. Single‐domain llama antibodies as specific intracellular inhibitors of SpvB, the actin ADP‐ribosylating toxin of Salmonella typhimurium . FASEB J. 2011;25:526‐534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chahbani I. Targeting Clostridioides Difficile CDTb and TcdB Toxins with Nanobodies Developed from Camelus Dromedarius Doctoral Dissertation. Staats‐und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg Carl von Ossietzky; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koch K, Kalusche S, Torres JL, et al. Selection of nanobodies with broad neutralizing potential against primary HIV‐1 strains using soluble subtype C gp140 envelope trimers. Sci Rep. 2017;7:8390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Saelens X, Schepens B. Single‐domain antibodies make a difference. Science. 2021;371:681‐682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schriewer L, Schutze K, Petry K, et al. Nanobody‐based CD38‐specific heavy chain antibodies induce killing of multiple myeloma and other hematological malignancies. Theranostics. 2020;10:2645‐2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lo M, Kim HS, Tong RK, et al. Effector‐attenuating substitutions that maintain antibody stability and reduce toxicity in mice. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:3900‐3908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Baum N, Eggers M, Koenigsdorf J, et al. Mouse CD38‐specific heavy chain antibodies inhibit CD38 GDPR‐cyclase activity and mediate cytotoxicity against tumor cells. Front Immunol. 2021;12:703574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Baudino L, Shinohara Y, Nimmerjahn F, et al. Crucial role of aspartic acid at position 265 in the CH2 domain for murine IgG2a and IgG2b fc‐associated effector functions. J Immunol. 2008;181:6664‐6669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Clynes RA, Towers TL, Presta LG, Ravetch JV. Inhibitory fc receptors modulate in vivo cytotoxicity against tumor targets. Nat Med. 2000;6:443‐446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. van Kampen MD, Kuipers‐De Wilt L, van Egmond ML, et al. Biophysical characterization and stability of modified IgG1 antibodies with different hexamerization propensities. J Pharm Sci. 2022;111:1587‐1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schutze K, Petry K, Hambach J, et al. CD38‐specific Biparatopic heavy chain antibodies display potent complement‐dependent cytotoxicity against multiple myeloma cells. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moore GL, Chen H, Karki S, Lazar GA. Engineered fc variant antibodies with enhanced ability to recruit complement and mediate effector functions. MAbs. 2010;2:181‐189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tintelnot J, Baum N, Schultheiss C, et al. Nanobody targeting of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) ectodomain variants overcomes resistance to therapeutic EGFR antibodies. Mol Cancer Ther. 2019;18:823‐833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vaccaro C, Zhou J, Ober RJ, Ward ES. Engineering the fc region of immunoglobulin G to modulate in vivo antibody levels. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1283‐1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gonde H, Demeules M, Hardet R, et al. A methodological approach using rAAV vectors encoding nanobody‐based biologics to evaluate ARTC2.2 and P2X7 in vivo. Front Immunol. 2021;12:704408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Balazs AB, Chen J, Hong CM, Rao DS, Yang L, Baltimore D. Antibody‐based protection against HIV infection by vectored immunoprophylaxis. Nature. 2011;481:81‐84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Abad C, Demeules M, Guillou C, et al. Administration of an AAV vector coding for a P2X7‐blocking nanobody‐based biologic ameliorates colitis in mice. J Nanobiotechnology. 2024;22:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Scully M, Cataland SR, Peyvandi F, et al. Caplacizumab treatment for acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:335‐346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Berdeja JG, Madduri D, Usmani SZ, et al. Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B‐cell maturation antigen‐directed chimeric antigen receptor T‐cell therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CARTITUDE‐1): a phase 1b/2 open‐label study. Lancet. 2021;398:314‐324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Takeuchi T, Chino Y, Kawanishi M, et al. Efficacy and pharmacokinetics of ozoralizumab, an anti‐TNFalpha NANOBODY([R]) compound, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: 52‐week results from the OHZORA and NATSUZORA trials. Arthritis Res Ther. 2023;25:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mullin M, McClory J, Haynes W, Grace J, Robertson N, van Heeke G. Applications and challenges in designing VHH‐based bispecific antibodies: leveraging machine learning solutions. MAbs. 2024;16:2341443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rossotti MA, Belanger K, Henry KA, Tanha J. Immunogenicity and humanization of single‐domain antibodies. FEBS J. 2022;289:4304‐4327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gordon GL, Raybould MIJ, Wong A, Deane CM. Prospects for the computational humanization of antibodies and nanobodies. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1399438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.