Abstract

ABSTRACT

Background

Liver metastasis is highly aggressive and immune tolerant, and lacks effective treatment strategies. This study aimed to develop a neoantigen hydrogel vaccine (NPT-gels) with high clinical feasibility and further investigate its efficacy and antitumor molecular mechanisms in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) for the treatment of liver metastases.

Methods

The effects of liver metastasis on survival and intratumor T-cell subpopulation infiltration in patients with advanced tumors were investigated using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) database and immunofluorescence staining, respectively. NPT-gels were prepared using hyaluronic acid, screened neoantigen peptides, and dual clinical adjuvants [Poly(I:C) and thymosin α-1]. Then, the efficacy and corresponding antitumor molecular mechanisms of NPT-gels combined with programmed death receptor 1 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 double blockade (PCDB) for the treatment of liver metastases were investigated using various preclinical liver metastasis models.

Results

Liver metastases are associated with poorer 5-year overall survival, characterized by low infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and high infiltration of regulatory T cells (Tregs). NPT-gels overcame the challenges faced by conventional neoantigen peptide vaccines by sustaining a durable, high-intensity immune response with a single injection and significantly improving the infiltration of neoantigen-specific T-cell subpopulations in different mice subcutaneous tumor models. Importantly, NPT-gels further combined with PCDB could enhance neoantigen-specific T-cell infiltration and effectively unlock the immunosuppressive microenvironment of liver metastases, showing superior antitumor efficacy and inducing long-term immune memory in various preclinical liver metastasis models without obvious toxicity. Mechanistically, the combined strategy can inhibit Tregs, induce the production and infiltration of neoantigen-specific CD8+CD69+ T cells to enhance the immune response, and potentially elicit antigen-presenting effects in Naïve B_Ighd+ cells and M1-type macrophages.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that NPT-gels combined with PCDB could exert a durable and powerful antitumor immunity by enhancing the recruitment and activation of CD8+CD69+ T cells, which supports the rationale and clinical translation of this combination strategy and provides important evidence for further improving the immunotherapy efficacy of liver metastases in the future.

Keywords: immune checkpoint inhibitor, immunotherapy, T cell, vaccine, T regulatory cell - Treg

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Tumor metastasis to the liver causes detrimental effects on intratumoral T-cell subpopulation infiltration, which is the pathological basis for the poor efficacy of ICIs.

In vivo studies demonstrated that the neoantigen hydrogel vaccine significantly enhanced tumor-specific T-cell infiltration and antigen presentation efficacy in liver metastases, and effectively unlocked the immunosuppressive microenvironment of liver metastases when combined with ICIs, exerting superior antitumor capacity mediated by CD8+CD69+ T cells.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Our study reports a safe and efficient immune combination strategy for the treatment of liver metastases and reveals the key role and functional properties of CD8+CD69+ T cells in the antitumor immune response, which provides important insights into the development of efficacy monitoring indicators or novel therapeutic targets in the future.

This discovery introduces a promising strategy for improving the management of immunotherapy in liver metastases.

Background

Metastasis is the leading cause of cancer-related death, and the liver is the most common site of metastases.1 Liver metastasis is highly aggressive, refractory, and generally associated with a poor prognosis.2,4 In recent years, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) such as programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1)/ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors have achieved unprecedented success in treating various advanced solid tumors.5,7 However, liver metastasis often respond poorly to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy, with only about 15% of patients deriving benefit.8 9 Several studies have shown that liver metastasis could significantly reduce distal tumor-specific immunity and systemic anti-PD-1 therapeutic response, which depends on the interaction between regulatory T cells (Tregs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, resulting in a liver immune desert state, where tumor-specific T cells have been clonally deleted, and immunotherapy resistance.8 10

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) blockade was shown to exert antitumor functions by upregulating effector T-cell activity and suppressing Tregs.11 In clinical practice, anti-PD-1/PD-L1 plus anti-CTLA-4 have been increasingly used to enhance antitumor efficacy. Of note, the 2022 updated Barcelona Liver Cancer Clinic guidelines recommend the combination of durvalumab (an anti-PD-L1 antibody) and tremelimumab (an anti-CTLA-4 antibody) as one of the first-line systemic therapies for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).12 However, available clinical data suggested that the objective response rate (ORR) of PD-1 and CTLA-4 double blockade (PCDB) for advanced tumors (including concomitant liver metastases) is still limited, largely not exceeding 30%.13 14 Pires et al investigated response rates and survival patterns in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with PCDB and demonstrated that liver metastasis was an independent risk factor for worse ORR and progression-free survival (PFS).15 Therefore, developing effective immunotherapy strategies to improve the long-term survival prospects of patients with liver metastases still poses a significant unmet challenge. How to improve the infiltration of tumor-specific T cells in liver metastases is the key to enhance the efficacy of ICIs.

Neoantigen is a kind of tumor-specific immunogenic antigen, generating from abnormal gene mutation, incomplete splicing, translation of alternatives, or post-translational modification in tumor cells but not in normal cells.16 Our previous studies through preclinical models and prospective clinical data from patients have demonstrated that tumor neoantigen vaccines can induce tumor-specific T cells to infiltrate into liver cancer tissues to exert antitumor effects,17 18 but the efficacy in liver metastases is still unknown. Meanwhile, conventional neoantigen peptide vaccines (NPTs) commonly used in clinical studies often require multiple injections on time due to their easy degradation and low bioavailability, and face the problem of insufficient immunogenicity. Vaccine gelation may be one of the important strategies to solve this problem, which can protect neoantigens from degradation, while allowing the slow release of antigens and fully stimulating the maturation of antigen-presenting cells.19 Hyaluronic acid (HA) is biocompatible, biodegradable, non-immunogenic, and non-cytotoxic. It has been used to treat multiple clinical diseases via subcutaneous injection,20 which makes it a potentially safe and reliable vaccine hydrogel vector.

Here, considering that the liver has a specific immune tolerance background different from other organs (eg, lung, bone, brain, etc), we first investigated the long-term survival and T-cell subpopulation infiltration in liver metastases of different cancers. Meanwhile, a neoantigen hydrogel vaccine (NPT-gels) with clinical application potential, which integrates tumor-specific antigens and dual adjuvants, was established to induce long-term, potent antitumor immune responses and reverse the immune-desert status of liver metastases. Furthermore, the efficacy and corresponding antitumor mechanisms of NPT-gels combined with PCDB for the treatment of liver metastases were further investigated in various preclinical liver metastasis models. Overall, we designed an effective neoantigen HA vaccine combined with PCDB for the treatment of liver metastases, and this combined strategy enhanced the recruitment and effector function of CD8+CD69+ T cells in the tumor microenvironment, which could potentially improve the status quo of immunotherapy for liver metastases.

Methods

Mice, cell lines, model construction, antitumor efficacy assessment, single-cell RNA sequencing analysis, and data extraction and analysis from the SEER database are detailed in the online supplemental methods section.

Human samples

Pathological specimens of breast cancer liver metastases (BCLM), lung cancer liver metastases (LCLM), colon cancer liver metastases (CCLM), and advanced HCC were obtained from Mengchao Hepatobiliary Hospital of Fujian Medical University. Immunofluorescence was performed routinely, as described in the online supplemental methods section.

Neoantigen identification, immunogenicity validation, preparation, and characterization of neoantigen hydrogel vaccine

DNA and RNA were extracted from mouse E0771 cells and C57BL/6 mouse tail tissues for whole exome sequencing and transcriptome sequencing(Berry Genetics), respectively. The raw sequencing data were quality controlled, compared, annotated, and filtered using a series of algorithms, toolkits, and variant effect predictor, respectively. Mutations with median predicted binding affinity percentile ≤2% to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules (E0771 cells and C57BL/6 mice: H-2Kb allele) were ultimately used for the synthesis of NPTs (17 amino acids in length). Next, the immunogenicity of the candidate neoantigen peptides and cross-reactivity with the corresponding wild-type peptides were evaluated by enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT). Then, highly immunogenic neoantigen peptides were mixed with two commonly used clinical adjuvants [poly(I:C) and thymosin α-1], which could synergistically enhance dendritic cells (DCs) maturation and antigen presentation,21 22 to obtain conventional NPT. HA hydrogel loaded with NPT to obtain NPT-gels. To clarify the optimal concentration of HA, the characteristics of NPT-gels with different initial HA concentrations were evaluated using scanning electron microscopy, swelling rate, gelling time, shear-thinning behavior, in vitro degradation, and controlled release. Detailed procedures are described in the online supplemental methods section.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (V.8.0.2) software. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. All sample data are expressed as mean±SD or SEM of at least three biologically independent samples. Statistical tests used for comparison of sample data included the Student’s t-test and one-way repeated measures analysis of variance test. All statistical analyses were two-tailed, and p value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Liver metastases associated with poorer 5-year survival and immunosuppressive microenvironment

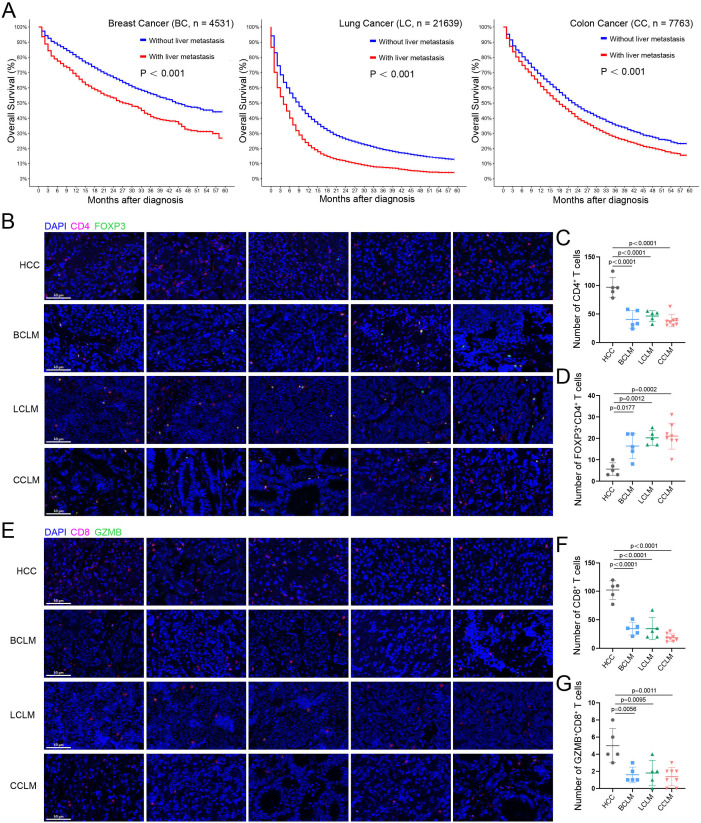

To investigate the impact of liver metastases on long-term survival of different cancer types, data from SEER database on patients diagnosed with advanced breast (n=4531), lung (n=21 639), and colon (n=7763) cancers between 2015 and 2020 were analyzed. As shown in figure 1A, regardless of the cancer types, patients with liver metastases were shown with significant poorer 5-year overall survival (OS) than those without liver metastases (all p<0.001). Long-term survival of patients with advanced tumors depends on receiving effective treatment. Several studies have shown that patients with liver metastases have significantly worse ORR, PFS, and OS after receiving PD-1/L1-based immunotherapy compared with patients without liver metastases.8 9 15 To clarify the potential reason for the poor efficacy of liver metastases against immunotherapy, infiltration of different T-cell subsets among BCLM (n=5), LCLM (n=5), or CCLM (n=8) and primary HCC (n=5) were evaluated by multiple immunofluorescence staining. As shown in figure 1B–D, the overall level of CD4+ T cells in liver metastases of different cancer was significantly lower than that in primary HCC (all p<0.0001), whereas Tregs (FOXP3+CD4+ T cells) were significantly upregulated (over 40% of CD4+ T cells are FOXP3+ cells, all p<0.05). Similarly, the overall levels of CD8+ T cells (all p<0.0001) and cytotoxic CD8+ T cells (GZMB+CD8+ T cells, all p<0.05) in liver metastases were significantly lower than those in primary HCC (figure 1E–G). To further compare the T-cell infiltration between liver metastatic lesions and primary cancer lesions, multicolor immunofluorescence analysis was performed on surgical pathological sections of three patients with CCLM inculding both the primary lesions and their paired liver metastases. As shown in online supplemental figure 1, the infiltration levels of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and cytotoxic CD8+ T cells were comparable between primary tumors and liver metastases, and all significantly less than primary HCC, suggesting the relatively ‘cold’ immune microenvironment of patients with liver metastates, either in the primary lesions or in the metastatic lesions. These results suggested that tumor metastasis to the liver causes detrimental effects on survival and immune background, and unlocking the immunosuppressive microenvironment is the key to improving the efficacy of immunotherapy for liver metastases.

Figure 1. The effect of tumor metastasis to the liver on survival and T-cell subset infiltration. (A) Comparison of OS in advanced breast, lung, and colon cancers with or without liver metastases from the SEER database. (B, C, and D) Immunofluorescence staining of CD4+ T cells and FOXP3+CD4+ T cells infiltration in human HCC, BCLM, LCLM, and CCLM tumor tissues (HCC, BCLM, LCLM, n=5; LCLM, n=8). (E, F and G) Immunofluorescence staining of CD8+ T cells and GZMB+CD8+ T cells infiltration in human HCC, BCLM, LCLM, and CCLM tumor tissues (HCC, BCLM, LCLM, n=5; LCLM, n=8). Scale bar: 50 μm (20×). BCLM, breast cancer liver metastasis; CCLM, colon cancer liver metastasis; GZMB, Granzyme B; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; LCLM, lung cancer liver metastasis; OS, overall survival.

Neoantigen identification and immunogenicity assessment

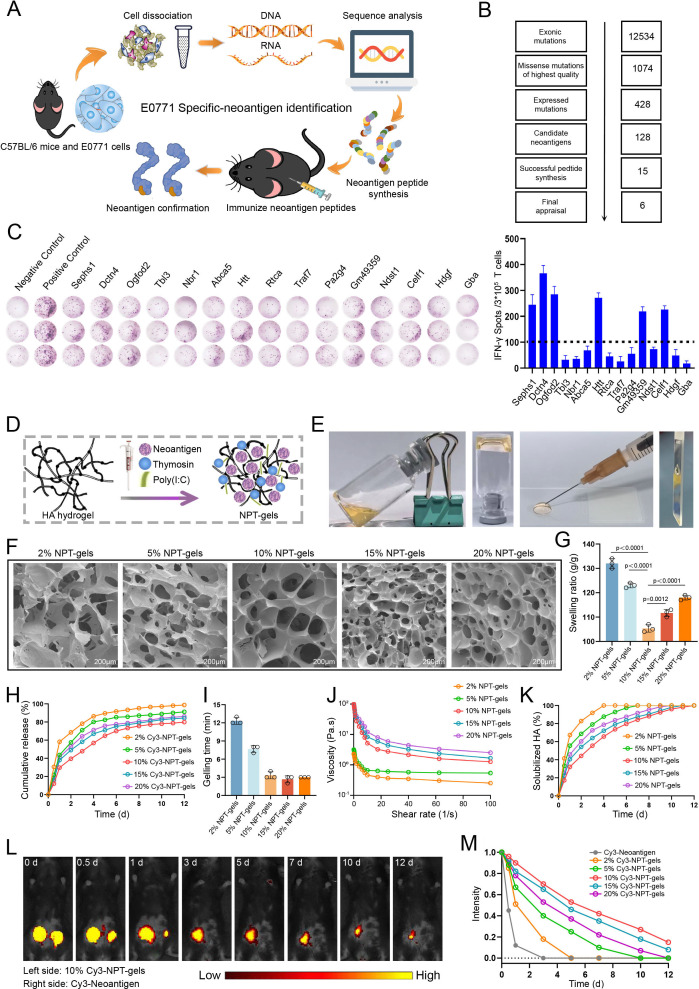

Clinically, the probability of liver metastasis in advanced breast cancer is 10%–20%. Most liver metastases are multifocal and cause significant liver swelling in the later stage, which are poorly responsive to immunotherapy. Therefore, we first selected breast cancer cell line E0771 with liver metastasis potential, which could simulate above features of breast cancer liver metastasis in mouse model, to assess whether the personalized neoantigen vaccine could increase tumor-specific T-cell infiltration in liver metastases. The personalized neoantigen vaccine of the E0771 cell line was prepared as indicated in figure 2A. Analysis of the sequencing results yielded 428 mutation sites that were stably expressed at the RNA level in E0771 cells, of which 128 mutation sites with high affinity to MHC I molecules (H2-Kb) were considered as potential immunogenic neoantigen mutations (figure 2B). Eventually, 15 neoantigen mutant long peptides (17aa) were selected to synthesize for in vivo immunogenicity assessment (online supplemental table 1). ELISPOT assay showed that six of the 15 candidate NPTs (Sephs1_V286M, Dctn4_K146T, Ogfod2_G253A, Htt_A2378P, Gm49359_V32A, Celf1_L223R) could induce significant immune responses in C57BL/6 mice and have no obvious cross-reactivity with the corresponding wild-type peptides (figure 2C and online supplemental figure 2A). Therefore, the conventional personalized neoantigen vaccine for the E0771 cell line (E-NPT) was developed by mixing these six NPTs with dual clinical adjuvants. In addition, seven and five NPTs previously identified by our team for the mouse lewis lung carcinoma LLC (Naa80_G150A, Zkscan1_K522R, Zscan21_H409L, Metap1_T84S, Kat2a_V192I, Dhrs9_L146P, Mapkbp1_W204C) and colon cancer MC38 (Lmo7_P269Q, Hacd2_Q231H, Hace1_N758Y, Irf2_R110L, Pam_R99L) cell lines with high liver metastasis potential were also prepared as neoantigen vaccines (L-NPT and M-NPT) for subsequent studies, respectively.23

Figure 2. Neoantigen identification and preparation for neoantigen hydrogel vaccines. (A) Process for identifying tumor neoantigen mutation sites in mouse E0771 cell line. (B) Workflow of tumor neoantigen mutation site screening. (C) Potential neoantigen immunogenicity validation performed by enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay. Six neoantigens with >100 spots were selected to develop neoantigen vaccines indicated by dotted line. (D and E) Process and appearance of neoantigen hydrogel vaccine preparation. (F and G) Three-dimensional structure and swelling rate of neoantigen hydrogel vaccines with different initial concentrations of hyaluronic acid (HA). (H) In vitro release curves of Cy-3 neoantigen hydrogel vaccines with different initial concentrations of HA. (I) The gelling time of neoantigen hydrogel vaccines with different initial concentrations of HA. (J) Viscosity of neoantigen hydrogel vaccines with different initial HA concentrations as a function of shear rate. (K) Degradation curves of neoantigen hydrogel vaccines with different initial HA concentrations in the presence of bovine testicular hyaluronidase. (L and M) In vivo release of neoantigen peptides from Cy3-labeled conventional neoantigen peptide vaccine (right) and neoantigen hydrogel vaccine (left) in mice and fluorescence change curves of neoantigen peptide vaccines with different initial HA concentrations.

Preparation and characterization of neoantigen hydrogel vaccine

Our previous study demonstrated that vaccine gelation based on silk protein can significantly improve vaccine-induced immunogenicity and antitumor efficacy, but there are still challenges in clinical application.24 Here, we developed a clinically applicable NPT-gels using HA to overcome the drawbacks of conventional clinical peptide vaccine (such as easy degradation and short efficacy) (figure 2D and E). Then, the characterization of NPT-gels was evaluated to clarify the optimal initial concentration of HA. Scanning electron microscopy showed that the initial concentrations of 2%, 5%, 15%, and 20% HA of the NPT-gels had a loose surface structure and poor cross-linking. In contrast, the 10% NPT-gels had a dense surface structure and a uniform pore size distribution, showing a more regular porous network (figure 2F). Meanwhile, the swelling and release rate of the 10% NPT-gels were significantly lower than other HA concentrations, indicating that NPT-gels with 10% HA had the most stable quality compared with other concentrations of HA (figure 2G and H). Furthermore, the gelling time decreased with increasing initial HA concentration but stabilized after 10% (figure 2I). During the entire frequency-dependent oscillatory shear experimental measurements, the storage modulus G′ was consistently higher than the loss modulus G″ (online supplemental figure 2B), indicating that the NPT-gels exhibited solid-like behavior over a wide range of frequencies. Notably, shear-thinning behavior and in vitro degradation experiments showed that 10% NPT-gels had good injectability and the strongest resistance to enzymatic hydrolysis compared with other concentrations (figure 2J and K). The in vivo release kinetics of neoantigen peptides from different NPT-gels were further evaluated. As expected, 2%, 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% Cy3-NPT-gels respectively sustained release of Cy3-neoantigen in mice for >3 days, 7 days, 12 days, 12 days, and 10 days, while the conventional Cy3-NPT was completely absorbed within 3 days (figure 2L and M and online supplemental figure 2C and D). These data suggest that NPT-gels with an initial HA concentration of 10% have the most stable cross-linking properties maintaining a stable and prolonged sustained release effect. Taken together, these data indicated that HA-loaded neoantigen vaccines have favorable release kinetics, reducing the number of injections while prolonging the window of antigen-presenting cells, which is conducive to enhance the immunostimulatory activity of the vaccines.

Antitumor efficacy assessment of neoantigen hydrogel vaccine

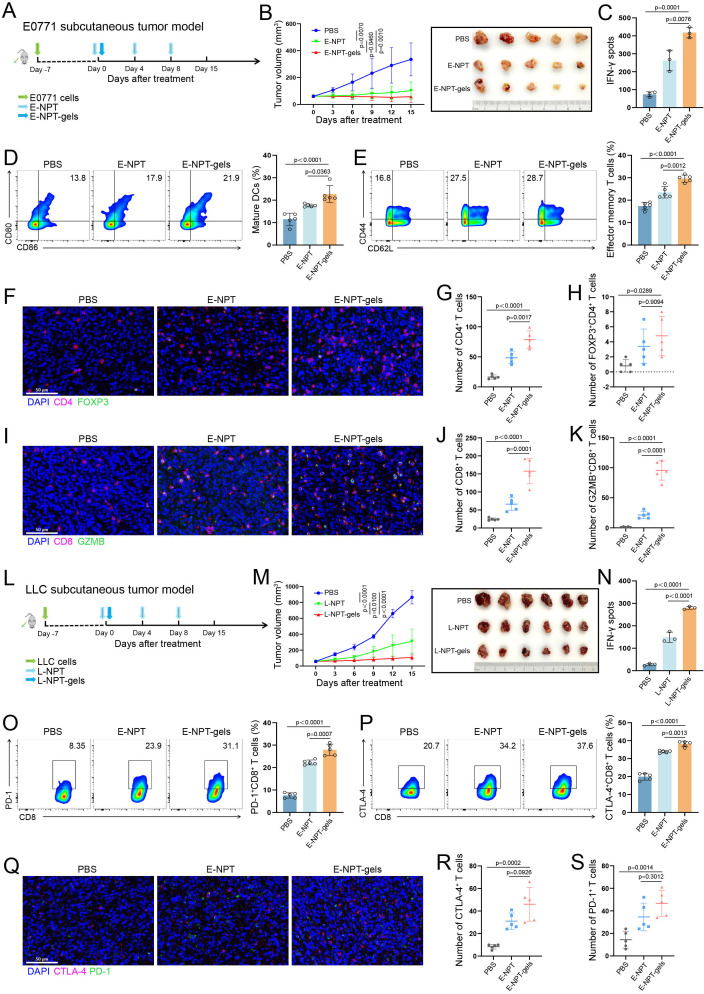

To assess the potential antitumor effects and immune response mechanisms of NPT-gels, the E0771 subcutaneous tumor model was constructed and further received subcutaneous injection of E-NPT and E-NPT-gels as indicated, respectively (figure 3A). As shown in figure 3B, the mice treated with E-NPT-gels demonstrated more pronounced tumor regression than treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (p=0.001) and E-NPT (p=0.046). ELISPOT assay showed that the mice treated with E-NPT-gels had stronger specific immune responses compared with those treated with PBS or E-NPT (p=0.0001 and p=0.0076, figure 3C and online supplemental figure 3A). The flow cytometry results demonstrated that the proportion of DC maturation (CD80+ and CD86+) and effector memory CD8+ T cells (Tem, CD44+, and CD62L−) were significantly higher in the E-NPT-gels-treated group than in the PBS group (p<0.0001 and p<0.0001) and E-NPT group (p=0.0363 and p=0.0012, figure 3D and E). Furthermore, immunofluorescence staining of tumor tissues showed increased intratumoral CD4+ T-cell and cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell infiltration in the E-NPT group compared with the PBS group (p=0.0010 and p=0.0242), but CD8+ T-cell infiltration and activation were more pronounced in the E-NPT-gels group (figure 3F–K). Spranger et al25 found that increased CD8+ T-cell infiltration in the tumors leads to a negative feedback regulation by increasing the numbers of Tregs, resulting in immune tolerance. Consistently, the number of Tregs in the tumor of the E-NPT-gels-treated group was significantly higher than that of the PBS-treated group (p=0.0289), suggesting that the tumor vaccine induced effector T-cell responses but along with the recruitment of Tregs at tumor sites (figure 3H).

Figure 3. Efficacy assessment of the neoantigen hydrogel vaccine in subcutaneous tumor models. (A) Schematic diagram of the E0771 breast cancer subcutaneous tumor model construction and vaccine-related treatment. (B) Tumor volume monitoring and gross conditions of C57BL/6 mice (n=5) treated with PBS, E0771 neoantigen peptides+Poly(I:C)+thymosin α-1 (E-NPT), and E-NPT-gels, respectively (tumors were excised after 15 days of treatment). (C) ELISPOT assay for neoantigen-specific immune response induced by different treatment strategies in the E0771 model. (D) The percentage of mature DCs co-expressing CD80 and CD86 in lymph nodes detected in E0771 model (n=5) by flow cytometry and statistical analysis. (E) The percentage of effector memory T cells among splenic CD8+ T cells detected in E0771 model (n=5) by flow cytometry and statistical analysis (n=5). (F–H) The schematic and statistical analysis of immunofluorescence for CD4+ T cells and FOXP3+CD4+ T cells in tumor tissues from E0771 model (n=5). (I–K) schematic and statistical analysis of immunofluorescence for CD8+ T cells and GZMB+CD8+ T cells in tumor tissues from E0771 model (n=5). (L) Schematic diagram of the LLC lung cancer subcutaneous tumor model construction and vaccine-related treatment. (M) Tumor volume monitoring and gross conditions of C57BL/6 mice (n=6) treated with PBS, LLC neoantigen peptides+Poly(I:C)+thymosin α-1 (L-NPT), and L-NPT-gels, respectively (tumors were excised after 15 days of treatment). (N) ELISPOT assay for neoantigen-specific immune response induced by different treatment strategies in the LLC model. (O and P) Flow cytometry was performed to detect the percentage of PD-1 and CTLA-4 expression on CD8+ T cells in tumors from E0771 model (n=5) and statistical analysis. (Q–S) The schematic and statistical analysis of immunofluorescence for the expression levels of PD-1 and CTLA-4 in tumor tissues from E0771 model (n=5). Scale bar: 50 μm (20×). CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4; DCs, dendritic cells; ELISPOT, enzyme-linked immunospot; GZMB, Granzyme B; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PD-1, programmed death receptor 1.

To further validate the antitumor ability and immune response mechanism of NPT-gels, LLC subcutaneous tumor model was constructed, and then subcutaneously injected with L-NPT or L-NPT-gels as indicated (figure 3L). As expected, similar results as the E0771 subcutaneous model were also observed in the LLC subcutaneous model. Compared with the PBS or L-NPT treated groups, tumors in the L-NPT-gels treated group were significantly regressed (figure 3M). Correspondingly, the maturation of DCs, the proportion of Tem, the neoantigen-specific immune response and the intratumor T-cell infiltration were significantly higher (figure 3N and online supplemental figure 3B–J).

Although the mice treated with E-NPT-gels/L-NPT-gels showed strong antitumor effects, it did not completely inhibit the growth or cure the subcutaneous tumor due to the immunosuppressive microenvironment. Tumor cells can achieve immune escape by inducing the enrichment of immunosuppressive cells (eg, Tregs) or upregulating the immune checkpoint signaling pathway to inhibit effector T-cell activation.25,27 The above results demonstrated an increased number of Tregs in the tumors of NPT-gels treated mice by immunofluorescence staining in the E0771 and LLC subcutaneous tumor models. Here, the expression of PD-1 and CTLA-4 on tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells in both models were further analyzed using flow cytometry as well as immunofluorescence staining. The results showed that PD-1 and CTLA-4 expression levels on tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells were significantly higher in the E-NPT/L-NPT and E-NPT-gels/L-NPT-gels treated groups compared with the PBS treated group, respectively (figure 3O–S and online supplemental figure 3K–O). These results revealed the potential immune tolerance mechanism for the limited efficacy of NPT-gels. Considering the potential resistance mechanism of NPT-gels and the strongly immunosuppressive microenvironment of liver metastases, combining them with PCDB may be effective in treating liver metastases.

Neoantigen hydrogel vaccine combined with PD-1 and CTLA-4 double blockade inducing stronger immune response in liver metastases

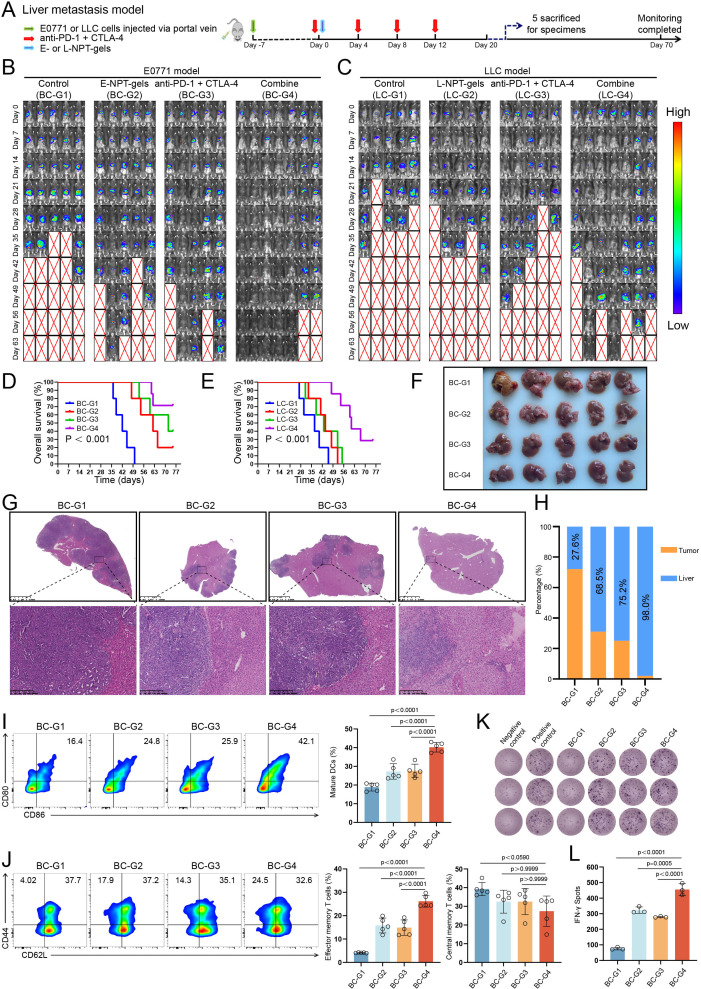

To further evaluate the antitumor effects of NPT-gels combined with PCDB, breast cancer and lung cancer liver metastases models were constructed via portal vein injection of E0771 and LLC cells, respectively (figure 4A and online supplemental figure 4A). As shown in figure 4B–E, by monitoring tumor burden for up to 70 days, the combined therapy strategy showed significant tumor regression and better OS (both p<0.001) compared with E-NPT-gels/L-NPT-gels or PCDB treatment alone in both two liver metastases models. Specifically, 71% (5/7) of mice in the E0771 model were eventually cured at day 63 (figure 4B); the LLC model demonstrated greater aggressiveness, with two previously tumor-absent mice showing tumor progression at 2 weeks after the completion of treatment, and 29% (2/7) mice were eventually cured (figure 4C). The antitumor efficacy of the combination therapy strategy was further confirmed by the gross appearance and H&E staining of sacrificed mice during the experiment. The combined group had fewer liver metastases compared with the other three groups (figure 4F–H and online supplemental figure 4B,C). Moreover, we further tested this combined strategy in a colon cancer liver metastasis model (based on MC38 cells) and achieved similar therapeutic effects to the previous breast cancer and lung cancer models (6/7 of the mice were eventually cured, online supplemental figure 4D).

Figure 4. Efficacy assessment of neoantigen hydrogel vaccine combined with PD-1 and CTLA-4 double blockade (PCDB) in liver metastasis models. (A) Schematic diagram of the construction and vaccine-related treatment for E0771 or LLC liver metastasis model. (B) Monitoring tumor burden changes among different treatment groups of mice in the E0771 liver metastasis model. (C) Monitoring tumor burden changes among different treatment groups of mice in the LLC liver metastasis model. (D and E) OS curves of mice in different treatment groups of E0771 and LLC liver metastasis models. (F) Liver gross appearance of each sacrificed mouse in the E0771 liver metastasis model on day 25 after treatment initiation. (G and H) H&E staining and statistical analysis of tumor nodules in liver tissues from E0771 liver metastasis model. (I) The percentage of mature DCs co-expressing CD80 and CD86 in lymph nodes of E0771 liver metastasis model detected by flow cytometry and statistical analysis (n=5). (J) The percentage of effector memory T cells and central memory T cells in splenic CD8+ T cells of E0771 liver metastasis model detected by flow cytometry and statistical analysis (n=5). (K and L) ELISPOT assay for neoantigen-specific immune response induced by different treatment strategies in the E0771 liver metastasis model. CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4; DC, dendritic cell; ELISPOT, enzyme-linked immunospot; OS, overall survival; PD-1, programmed death receptor 1.

Adverse events are the main reason that hinders the clinical application of immune combination strategy. During the 2-week treatment course, no significant discomfort manifestations or abnormal biological behaviors were observed in mice from the E-NPT-gels/L-NPT-gels, PCDB, and combined groups. Additionally, the safety of the combined treatment strategy was evaluated by blood biochemical assays and H&E staining of vital organs. The results showed that NPT-gels did not amplify the toxicity of PCDB and did not cause significant and irreversible damage to organ function in mice (online supplemental figure 5).

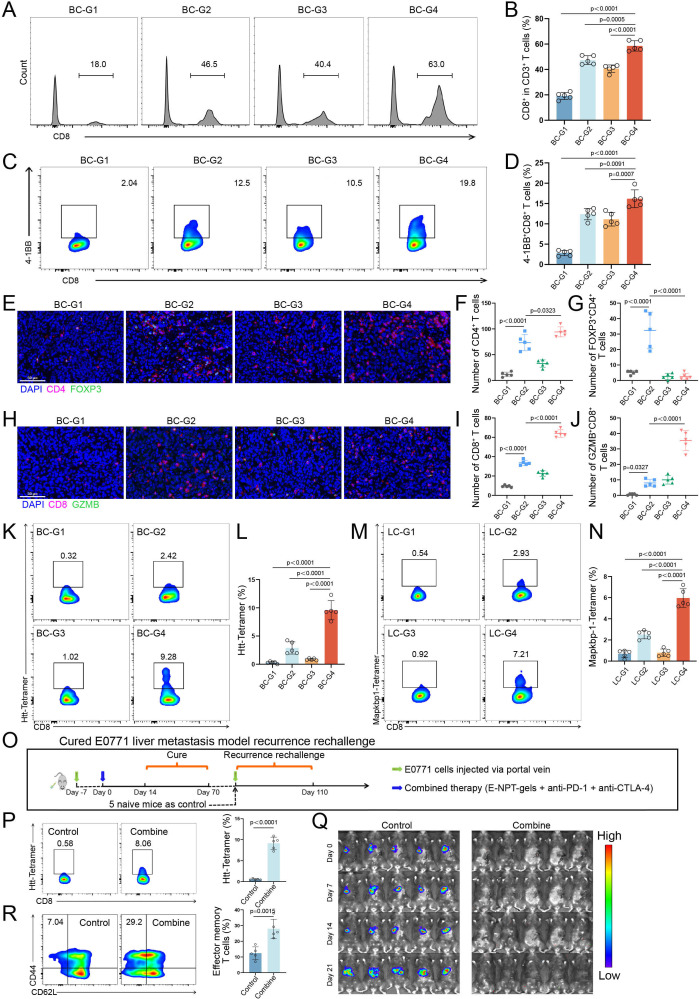

The phenotypes of different immune cells in liver metastasis models were further analyzed to investigate the systemic changes of specific lymphocyte subsets under combined therapy. Flow cytometry analysis showed that the percentage of mature DCs in lymph nodes, and the percentage of effector memory CD8+ T cells (Tem, CD44+, and CD62L−) in lymph nodes, spleen, and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were all significantly higher in the combined treatment group than in the other three groups (figure 4I and J and online supplemental figure 6A and B). However, the percentage of central memory CD8+ T cells (Tcm, CD44+, and CD62L−) in spleen and TILs were not significantly different among these groups (figure 4J and online supplemental figure 6B). Moreover, ELISPOT assay showed that the neoantigen-specific immune response induced by the combined treatment was stronger than the other three treatments in both E0771 and LLC liver metastasis models (figure 4K and L, and online supplemental figure 6C). Furthermore, flow cytometry showed that the percentage of intratumoral CD8+ T-cell infiltration and activation (4-1BB+CD8+ T cells) were significantly higher in the combined treatment group than in the remaining three groups for the E0771 liver metastasis model (all p<0.001, figure 5A–D). Then the corresponding results were further confirmed using immunofluorescence staining in E0771 and LCC liver metastasis models (figure 5E–J and online supplemental figure 6D–I). Notably, similar to the results for human liver metastasis specimens that did not receive immunotherapy, the proportion of Tregs was abnormally high (over 40% of CD4+ T cells are FOXP3+ cells) in the control group for both models. Furthermore, Tregs were significantly enriched in the NPT-gels group, whereas a marked reduction of Tregs along with an increase of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells were observed in the combined treatment group, which was attributed to the antitumor response mediated by PCDB (figure 5G and J, and online supplemental figure 6F and I). Finally, specific T-cell receptors in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells were detected using fluorescently labeled highly immunogenic neoantigen peptide (E0771: Htt_A1378P; LLC: Mapkbp1_W204C) tetramers to clarify the neoantigen-specific T-cell infiltration. Results of both E0771 and LLC models consistently showed a significant increase in the percentage of neoantigen-specific T-cell infiltration in the NPT-gels and combined treated groups (figure 5K–N). Overall, these results suggest that NPT-gels can synergize with PCDB to mutually sensitize and effectively unlock the immunosuppressive microenvironment of liver metastasis, generating significant therapeutic responses without obvious toxicity in several preclinical liver metastasis models.

Figure 5. Immune response assessment of neoantigen hydrogel vaccine combined with PD-1 and CTLA-4 double blockade (PCDB) in liver metastasis models. (A and B) The percentage of CD8+ T-cell infiltration in tumor tissues of E0771 liver metastasis model detected by flow cytometry and statistical analysis (n=5). (C and D) The percentage of CD8+ T-cell activation in tumor tissues of E0771 liver metastasis model detected by flow cytometry and statistical analysis (n=5). (E–G)The schematic and statistical analysis of immunofluorescence for CD4+ T cells and FOXP3+CD4+ T cells in tumor tissues of E0771 liver metastasis model (n=5). (H–J) The schematic and statistical analysis of immunofluorescence for CD8+ T cells and GZMB+CD8+ T cells in tumor tissues from E0771 liver metastasis model (n=5). (K and L) The percentage and statistical analysis of Htt-specific CD8+ T cells in tumor tissues of E0771 liver metastasis mice (n=5). (M and N) The percentage and statistical analysis of Mapkbp1-specific CD8+ T cells in tumor tissues of LLC liver metastasis mice (n=5). (O) The schematic diagram of the recurrence rechallenge experiment of five mice cured in the combined treatment group from the E0771 liver metastasis model. (P) The percentage and statistical analysis of Htt-specific CD8+ T cells in blood mononuclear cells of mice in control and combined groups in the recurrence rechallenge experiment before injection of E0771 cells (n=5). (Q) Changes of tumor burden in mice of both groups were monitored by IVIS Spectrum Animal Imaging System. (R) Percentage and statistical analysis of effector memory CD8+ T cells in splenic cells of control and combined treatment mice at the end of monitoring in recurrence rechallenge experiments (n=5). Scale bar: 50 μm (20×). CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4; GZMB, Granzyme B; PD-1, programmed death receptor 1.

Combination therapy strategy induces long-term immune memory for preventing recurrence of liver metastases

In light of these remarkable therapeutic results, we further investigated whether the combination therapy could induce long-term immune memory to prevent tumor recurrence. To simulate tumor recurrence, five mice cured in the combined treatment group of E0771 liver metastasis model (figure 4B) were re-injected with E0771 cells via portal vein for recurrence re-challenge, and five new untreated mice were served as the control group (figure 5O). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from both groups of mice were collected and analyzed for peptide-MHC tetramer staining before injection of E0771 cells. Surprisingly, remarkably high levels of neoantigen-specific T cells were still detectable in the five cured mice approximately 2 months after tumor cure compared with the control group (p<0.0001, figure 5P). Importantly, no tumor growth was observed in all five cured mice after reimplantation of the tumors, whereas tumors continued to grow in the control group (figure 5Q). Furthermore, a significantly higher proportion of Tem in the spleen were observed in the five cured mice compared with the control group, indicating the strong inducing ability of long-term neoantigen-specific immune memory for combination therapy (p=0.0015, figure 5R). Since there were not enough cured mice (only two mice, figure 4C) in the LLC model, similar antirelapse validation was not performed. But in general, these results suggested that the combined treatment strategy induces long-term neoantigen-specific immune memory and effectively prevents the recurrence of liver metastases.

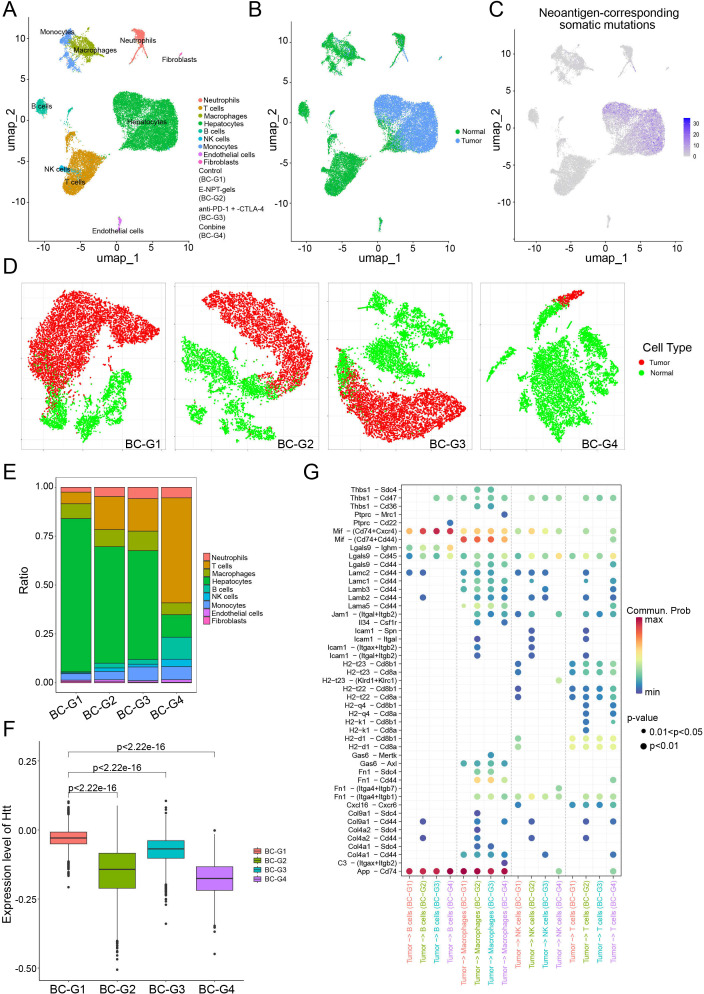

To comprehensively explore the changes of immune microenvironment for liver metastasis under different treatment strategies, scRNA-seq was performed on tumor samples from the E0771 liver metastasis model. As shown in figure 6A, total of nine cell types were identified by scRNA-seq. Copy number variation analysis and genotyping of neoantigen-corresponding somatic mutations confirmed the tumorigenic essence of hepatocyte clusters (figure 6B and C). As shown in figure 6D and E, tumor cells were significantly reduced and the proportion of T cells was rapidly expanded in the combined treatment group compared with the PBS group. It is well known that neoantigen-specific T cells can target and kill highly neoantigen-mutated tumor cells. Therefore, the expression levels of the parent gene of representative neoantigen mutation (Htt-A2378P) of the E0771 cells were further evaluated at the tumor single-cell level in different treatment groups. As shown in figure 6F, compared with the control group, the expression levels of the neoantigen-mutated Htt gene on tumor cells were downregulated in the remaining three treatment groups (all p<0.05), with the downregulation being most significant in the combined treatment group. Additionally, the interaction between tumor cells and immune cells (B cells, macrophages, natural killer cells, and T cells) was more intense in the three treatment groups compared with the control group (figure 6G). The number of ligand-receptor pairs indicated that probability of communication between tumor cells and T cells was high and concentrated in the E-NPT-gels and combined treatment groups, whereas the control group was relatively limited. These interactions were focused between MHC molecules on tumor cells and CD8 molecules on T cells (eg, H2-q4-CD8a, H2-q4-CD8b1, etc), and between laminin subunits on tumor cells and CD44 molecules on T cells (eg, Lama5-CD44, Lamb3-CD44, etc); the former are classical antigen presentation pathways, and the latter enhance immune cell infiltration.28,31 Notably, the enhanced interaction of Mif-(Cd74+Cxcr4) (the ability of T cells migration and infiltration into tumor tissues) and Lgals9-Cd45 (the promotion of the reception and presentation of antigenic stimulation signals by T cells) was also stronger in the combined treatment group than in control group. These data suggest that the combined treatment strategy could enhance antigen presentation and promote neoantigen-specific T-cell infiltration, and that its antitumor efficacy is largely dependent on the tumor-killing effect of neoantigen-specific T cells.

Figure 6. Single-cell RNA sequencing characterizes immune microenvironment changes in E0771 liver metastasis model. (A) Two-dimensional t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) plot showing nine identified cell clusters in E0771 liver metastasis tumor. (B) The t-SNE plot of tumor cells originating from hepatocytes was clarified by copy number analysis. (C) t-SNE plot showing the number of neoantigen-corresponding somatic mutations detected in all cell clusters. (D) Distribution of tumor cells in each group. (E) Histogram showing the proportion of different cell clusters in each treatment group. (F) Expression levels of the parent gene of representative neoantigen mutations (Htt) at the tumor single-cell level in different treatment groups of the E0771 liver metastasis model. (G) Ligand-receptor interactions between tumor cells and B cells, macrophages, natural killer cells, and T cells calculated using CellChat.

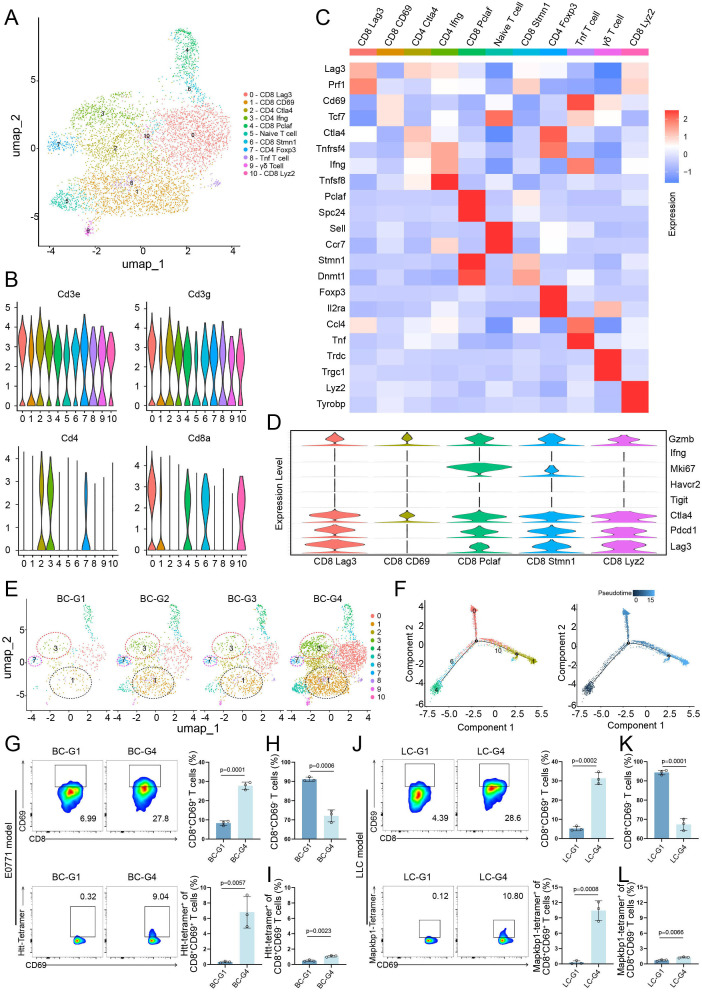

Functional T-cell subpopulation expressing CD8 and CD69 greatly expanded after combined therapy

To better understand different T-cell subpopulations with distinct functional status change during different treatment conditions, T cells were further extracted and reclustered (figure 7A). Based on the expression of common-acknowledged T-cell functional markers, the reclustered T cells were identified as five CD8+ T-cell clusters (0, 1, 4, 6, 10) and three CD4+ T-cell clusters (2, 3, 7) (figure 7B). These clusters were further categorized and labeled based on the expression patterns of marker genes (figure 7C). Since the antitumor response was mainly mediated by CD8+ T cells, the characterization of CD8+ T cells was further analyzed. As shown in figure 7D, except for the CD8_CD69 cell cluster, the other four CD8+ T-cell clusters highly expressed markers (LAG3, PDCD1, and CTLA4) associated with the “exhaustion” state.32 Meanwhile, CD8_CD69 cell cluster expresses GZMB and TCF7 (figure 7C and D). GZMB represents strong tumor killing capacity, while high expression of TCF7 gene is associated with enhanced efficacy of ICIs.33 Furthermore, CD8_CD69 cell cluster was significantly enriched in the combined treatment group and very limited in other three groups (figure 7E). Notably, the T helper 1 cell (Th1, CD4_IFNG) cluster and CD4_FOXP3 cell cluster were highly enriched in the combined treatment group and the E-NPT-gels treatment group, respectively (figure 7E). Cell-to-cell interaction analysis showed that intratumoral Th1 could present antigens more efficiently to CD8+CD69+ T cells in the combined treatment group compared with the remaining three groups (online supplemental figure 7A). Pseudotemporal analysis revealed that CD8+ T cells first underwent clonal proliferation (CD8_PCLAF) and then differentiate into CD8_LAG3 and CD8_CD69 T-cell subsets (figure 7F). These findings suggest that neoantigen vaccine alone indeed induces proliferation of Tregs and causes immunosuppression, and that CD8+CD69+ T cells may be the key T-cell subpopulation for the antitumor immunity exerted by the combined therapeutic strategy.

Figure 7. (A) Two-dimensional t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) plot showing 11 identified T-cell clusters in E0771 liver metastasis tumor. (B) Violin plot showing the expression of recognized T-cell function markers. (C) Heatmap showing the expression levels of subtype-specific marker genes for all T-cell subtypes. (D) Violin plots showing expression of classical immune checkpoint and activation marker genes in CD8+ T-cell subtypes. (E) t-SNE plots of the enrichment of different T-cell clusters under different treatment strategies. (F) Pseudotime trajectory of CD8+ T-cell subtypes: colored by cell subtypes (left), colored by pseudotime (right). (G) The percentage of neoantigen Htt-specific T cells with high expression of CD69 in CD8+ T cells in tumor tissues of different treatment groups in the E0771 liver metastasis model was detected by tetramer flow cytometry and statistically analyzed (n=3). (H and I) The percentage of neoantigen Htt-specific T cells with low expression of CD69 in CD8+ T cells in tumor tissues of different treatment groups in the E0771 liver metastasis model was detected by tetramer flow cytometry and statistically analyzed (n=3). (J) The percentage of neoantigen Mapkbp1-specific T cells with high expression of CD69 in CD8+ T cells in tumor tissues of different treatments in the LLC liver metastasis model was detected by tetramer flow cytometry and statistically analyzed (n=3). (K and L) The percentage of neoantigen Mapkbp1-specific T cells with low expression of CD69 in CD8+ T cells in tumor tissues of different treatment groups in the LLC liver metastasis model was detected by tetramer flow cytometry and statistically analyzed (n=3).

To investigate whether neoantigen-specific T cells were significantly enriched in CD8+CD69+ cells, Htt and Mapkbp1 tetramer flow cytometry analysis was performed in the E0771 and LCC liver metastasis models, respectively. In the E0771 liver metastasis model, CD8+CD69+ cells were significantly higher in the tumors of the combined treatment group than the control group (p=0.0001), and neoantigen-specific CD8+ T cells were significantly enriched in CD69- positive cells. Specifically, the proportion of neoantigen-specific CD8+ T cells in CD69-positive and CD69-negative cells was close and relatively low in the control group (0.32% vs 0.60%, p=0.124), whereas the proportion of neoantigen-specific CD8+ T cells in CD69-positive cells was approximately 8-fold to 10-fold higher than that in CD69-negative cells (9.04% vs 1.16%, p=0.0088) in the combined treatment group (figure 7G–I). Consistent results were observed in the LLC liver metastasis model (figure 7J–L). These results suggest that the combined therapeutic strategy enhances neoantigen-specific CD8+CD69+ T-cell recruitment and infiltration. Furthermore, the tumor-killing efficiency of CD8+CD69+ T cells were evaluated in vitro to investigate whether CD8+CD69+ T cells play a critical role in antitumor immune response induced by combined therapeutic strategy. As expected, the CD8+CD69+ T cells could induce nearly fourfold tumor-killing efficiency when compared with the CD8+CD69− T cells (p<0.0001, online supplemental figure 7B). These data further reinforce the critical role and potential application of CD8+CD69+ T cells in the treatment of liver metastases.

B cells and macrophages enhances the antitumor efficacy of CD8+CD69+ T cells

Figure 6E shows that B cells also exhibited highly enrichment in the tumors of the combined treatment group compared with the control group, which were further confirmed by flow cytometry analysis (p=0.0002, online supplemental figure 7C and D). Further analysis revealed that cluster 0 B cells (Naïve B_Ighd+ cells: highly expressing Ccr7, Sell, and Ighd) accounted for the highest percentage in the combined treatment group and very little in the control group (online supplemental figure 7E and F). Naïve B_Ighd+ cells could enhance the tumor clearance ability of the immune system by interacting with Th1. As shown in online supplemental figure 7G, there was the strongest antigen-presenting effect between Naïve B_Ighd+ cells and Th1 in the tumors of the combined treatment group, whereas no effect was observed in the control group.

Furthermore, macrophage subpopulations were further analyzed and the distribution of M1-type and M2-type macrophage populations was briefly determined by assessing the expression levels of CD80 and CD206 genes (online supplemental figure 8A–C). The critical role of antigen presentation response in the antitumor immune response has been widely recognized,34 35 and intratumor M1-type macrophages can exclusively present antigens. Notably, M1-type macrophages were more enriched and had a stronger antigen-presenting capacity in tumors of the combined treatment group compared with the control group (online supplemental figure 8D and E). As shown in online supplemental figure 9A–E, flow cytometry analysis further confirmed that the percentages of M1-type macrophages (CD11b+CD80+ cells) in the tumor collected from mice in the combined treatment group were markedly increased when compared with the control group (p<0.0001), while the percentages of M2-type macrophages (CD11b+CD206+ cells) were significantly decreased (p=0.0081), leading to a significantly upregulated M1/M2 ratio (p<0.0001). To further identify the potential correlation between B Ighd+ cells/M1 macrophages and T-cell activation, two multiple immunofluorescence staining [(CD20, Ighd, CD3, and CD69) and (CD11b, CD80, CD3, and CD69)] were performed in tumor sections from the combination treatment and the control, respectively. As shown in online supplemental figure 9F, B_Ighd+ cells, M1 macrophages, and T cells were all significantly enriched around the tumors in the combination treatment group, but there was no such phenomenon in the control group. Meanwhile, a large number of B_Ighd+ cells and M1 macrophages closely distributed around activated T cells (CD3+CD69+ T cells), suggesting a positive correlation between B_Ighd+ cells/M1 macrophages and the activation of T cells. In conclusion, these findings provide compelling evidence that the combination of NPT-gels with PCDB significantly enhances pro-inflammatory innate immune cell infiltration and activation in the liver metastasis tumor microenvironment, thereby augmenting the antitumor capacity of CD8+CD69+ T cells.

Discussion

In clinical studies, ICIs as monotherapy have shown only limited efficacy in patients with liver metastases so far,9 15 36 highlighting the urgent need to seek optimized combination immunotherapy regimens. The present study reveals the adverse effects of liver metastases on survival and the liver immune microenvironment. Based on this, we reported that a novel immunotherapeutic strategy of NPT-gels combined with PCDB resulted in tumor regression in various liver metastasis mouse models. This combined therapeutic strategy demonstrated superior CD8+CD69+ T-cell-mediated antitumor efficacy, effectively treating liver metastases and preventing tumor recurrence. Mechanistically, NPT-gels sensitized PCDB by inducing neoantigen-specific CD8+CD69+ T-cell production and infiltration, while upregulating the expression of PD-1 and CTLA-4; in turn, PCDB blocked the mechanism of tumor cells escaping from killing by neoantigen-specific CD8+ T cells, potentially augmenting the efficacy of NPT-gels.

Tumor immunotherapy can be divided into two types based on the mechanism of action32: the first enhances the antitumor response both inside and outside the tumor microenvironment by restoring the toxicity of exhausted antitumor T cells already present in the tumor (eg, immunotherapy with ICIs)27; the second induces a tumor-specific immune response, generating new antitumor T cells and promoting their infiltration into tumor tissues, thereby exerting antitumor effects (eg, personalized neoantigen vaccine immunotherapy). Previous animal studies have shown that tumor metastasis to the liver leads to Treg induction and CD8+ T-cell deficiency.8 10 In this study, we found that reduced CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell infiltration within BCLM, LCLM, and CCLM tumors was accompanied by induction of Tregs and insufficient activation of effector-killing CD8+ T cells compared with primary HCC. Therefore, increasing tumor-specific T cell infiltration in liver metastases may be the key to improving the therapeutic efficacy of ICIs.

Personalized neoantigen vaccines can stimulate high-affinity T-cell responses and promote tumor-specific T-cell infiltration,17 37 but their ability to effectively increase tumor-specific T-cell infiltration in liver metastases has not been reported. Furthermore, the NPTs that are most commonly used in clinical studies could not induce sufficient tumor-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses due to the short efficacy and easy of degradation in vivo, which resulted in limited benefits of patients.38 39 Theoretically, injectable hydrogels could enable controlled loading and release of neoantigen vaccines at the microscopic level, providing antigen-presenting cells with a longer window of action to stimulate more effective antitumor immunity. Studies have shown that hydrogels developed from crosslinked polymer nanoparticles and nanofibrous peptides, or other materials can enhance the immunostimulatory activity of vaccines.40 41 However, there is still a long way to go before these delivery carrier materials can be successfully applied in clinical settings. In this study, we found that NPT-gels prepared using HA, a clinically used material, significantly increased tumor-specific T-cell infiltration in liver metastases while reducing the number of administrations. Importantly, NPT-gels combined with PCDB showed superior CD8+CD69+ T cell mediated antitumor efficacy, which is expected to be an important immunotherapeutic strategy to improve the survival of patients with liver metastases or other metastatic cancers in the future.

CD8+ T cells with a CD69 phenotype are generally referred to as tissue-resident memory T cells (TRMs).42 TRMs enrichment within tumors is thought to be associated with a favorable prognosis in several human solid tumors.43 44 However, intratumoral TRMs generally exhibit an inhibited and depleted state due to high expression of marker genes representing depletion (eg, Pdcd1, Ctla4, Lag3).45 In other words, eliminating these inhibitory signals to release the activity of TRMs may help to enhance the efficacy of immunotherapy. Currently, the role of TRMs within metastatic solid tumors (eg, liver metastases) and their evolutionary mechanisms, as well as the relative contribution to the efficacy of neoantigen vaccines and ICIs, remain poorly understood. In this study, we found that CD8_PCLAF cells within liver metastases were induced to differentiate into CD8+CD69+ T cells and were significantly enriched within the tumor microenvironment under combined treatment with NPT-gels and PCDB. Importantly, these CD8+CD69+ T cells expressed GZMB and Tcf7 without overexpressing marker genes representing depletion, showing strong tumor-killing capacity. These results suggest that CD8+CD69+ T cells play a critical role in the antitumor immune response of liver metastases, and the combination of NPT-gels with PCDB is a potent strategy for inducing their generation, infiltration, and activation.

Enhancing the efficiency of antigen-presenting cells in the tumor microenvironment could enhance antitumor T-cell responses. Impaired antigen presentation within the tumor microenvironment is an important cause of therapeutic failure of ICIs.46 Apart from Th1, B cells and macrophages also play an important role in antigen presentation within the tumor microenvironment. It has been found that tumor-infiltrating B cells can present and activate CD4+ T cells in the absence of exogenous antigen, giving them a Th1 phenotype.47 In this study, we found that Naïve B_Ighd+ cells were significantly enriched in liver metastases after NPT-gels combined with PCDB treatment and had the strongest antigen-presenting efficacy against Th1. Moreover, Gill et al found that M1-type macrophages in the tumor microenvironment could upregulate the antigen presentation mechanism, recruiting antigens and presenting them to T cells, thus enhancing antitumor T-cell activity.48 In the present study, M1 macrophage numbers, antigen presentation efficiency, and inflammatory cytokine release rates within liver metastases were increased after NPT-gels combined with PCDB treatment. These data suggested that the combined therapeutic strategy may more effectively use the potential of B cells and M1 macrophages in cancer immunotherapy, and a deeper understanding of these cells’ biology is necessary in the future.

Conclusion

In summary, this study reports a safe and efficient immune combination strategy for the treatment of liver metastases and reveals the key role and functional properties of CD8+CD69+ T cells in the antitumor immune response of liver metastases, which provides important insights into the development of efficacy monitoring indicators or novel therapeutic targets in the future. Thus, our work provides insights into the important determinants of immunotherapy efficacy in liver metastases.

supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the support of Fujian Provincial Clinical Research Center for Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Tumors (2020Y2013) and the Molecular Medicine Innovation Platform of Fuzhou (grant no. 2021-S-wp1) .

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. U22A20328 and 82202027), Scientific Foundation of Fujian Province (grant no. 2023J06049), the Major Research Projects for Young and Middle-aged Talent of Fujian Provincial Health Commission (grant no. 2022ZQNZD014), Fuzhou Science and Technology Planning Project (grant no. 2023-R-003), the Science and Technology Plan Project of Fuzhou Health and Health System (grant no. 2022-S-wt2).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: All patients provided informed consent before participation in the study.

Ethics approval: Human specimens for this study were obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Mengchao Hepatobiliary Hospital, Fujian Medical University (approval no. 2021_100_02). All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Mengchao Hepatobiliary Hospital, Fujian Medical University (approval no. MCHH-AEC-2022-09).

Data availability free text: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Inquiries about further material documents can be directed to the corresponding author. The single-cell transcriptome sequencing data from this publication have been deposited to the Genome Sequencing Achieve (GSA) database (GSA number: CRA016206).

Contributor Information

Shichuan Tang, Email: doctortang2022@163.com.

Ruijing Tang, Email: trjtrjtrj@163.com.

Geng Chen, Email: thestaroceanster@hotmail.com.

Da Zhang, Email: zdluoman1987@163.com.

Kongying Lin, Email: lkongying@163.com.

Huan Yang, Email: yh1778464050@163.com.

Jun Fu, Email: fujun@fjmu.edu.cn.

Yutong Guo, Email: guoyutong202011@163.com.

Fangzhou Lin, Email: 447154875@qq.com.

Xiuqing Dong, Email: xiuqing0301@163.com.

Tingfeng Huang, Email: tfun1997@163.com.

Jie Kong, Email: weidaoshi1987@163.com.

Xiaowei Yin, Email: yinxiaowei2007@sina.com.

Aimin Ge, Email: gam1028@163.com.

Qizhu Lin, Email: linqizhu1024@163.com.

Ming Wu, Email: wmmj0419@163.com.

Xiaolong Liu, Email: xiaoloong.liu@gmail.com.

Yongyi Zeng, Email: lamp197311@126.com.

Zhixiong Cai, Email: caizhixiong1985@163.com.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1.Chaffer CL, Weinberg RA. A perspective on cancer cell metastasis. Science. 2011;331:1559–64. doi: 10.1126/science.1203543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riihimäki M, Thomsen H, Hemminki A, et al. Comparison of survival of patients with metastases from known versus unknown primaries: survival in metastatic cancer. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner JS, Adson MA, Van Heerden JA, et al. The natural history of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. A comparison with resective treatment. Ann Surg. 1984;199:502–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198405000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu Z, Yang Q, Chen X, et al. Clinical associations and prognostic value of site-specific metastases in non-small cell lung cancer: A population-based study. Oncol Lett. 2019;17:5590–600. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.10225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim JH, Kim SY, Baek JY, et al. A Phase II Study of Avelumab Monotherapy in Patients with Mismatch Repair-Deficient/Microsatellite Instability-High or POLE-Mutated Metastatic or Unresectable Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 2020;52:1135–44. doi: 10.4143/crt.2020.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Five-Year Outcomes With Pembrolizumab Versus Chemotherapy for Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score ≥ 50. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:2339–49. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2492–502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31046-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu J, Green MD, Li S, et al. Liver metastasis restrains immunotherapy efficacy via macrophage-mediated T cell elimination. Nat Med. 2021;27:152–64. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1131-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tumeh PC, Hellmann MD, Hamid O, et al. Liver Metastasis and Treatment Outcome with Anti-PD-1 Monoclonal Antibody in Patients with Melanoma and NSCLC. Cancer Immunol Res. 2017;5:417–24. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JC, Mehdizadeh S, Smith J, et al. Regulatory T cell control of systemic immunity and immunotherapy response in liver metastasis. Sci Immunol. 2020;5:52. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aba0759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:252–64. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reig M, Forner A, Rimola J, et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J Hepatol. 2022;76:681–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yau T, Kang Y-K, Kim T-Y, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Previously Treated With Sorafenib: The CheckMate 040 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:e204564. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.4564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kudo M. Durvalumab Plus Tremelimumab: A Novel Combination Immunotherapy for Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2022;11:87–93. doi: 10.1159/000523702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pires da Silva I, Lo S, Quek C, et al. Site-specific response patterns, pseudoprogression, and acquired resistance in patients with melanoma treated with ipilimumab combined with anti-PD-1 therapy. Cancer. 2020;126:86–97. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lang F, Schrörs B, Löwer M, et al. Identification of neoantigens for individualized therapeutic cancer vaccines. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022;21:261–82. doi: 10.1038/s41573-021-00387-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen H, Li Z, Qiu L, et al. Personalized neoantigen vaccine combined with PD-1 blockade increases CD8+ tissue-resident memory T-cell infiltration in preclinical hepatocellular carcinoma models. J Immunother Cancer. 2022;10:e004389. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-004389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cai Z, Su X, Qiu L, et al. Personalized neoantigen vaccine prevents postoperative recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with vascular invasion. Mol Cancer. 2021;20:164. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01467-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao H, Duan L, Zhang Y, et al. Current hydrogel advances in physicochemical and biological response-driven biomedical application diversity. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:426. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00830-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vasvani S, Kulkarni P, Rawtani D. Hyaluronic acid: A review on its biology, aspects of drug delivery, route of administrations and a special emphasis on its approved marketed products and recent clinical studies. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;151:1012–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niemi JVL, Sokolov AV, Schiöth HB. Neoantigen Vaccines; Clinical Trials, Classes, Indications, Adjuvants and Combinatorial Treatments. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:5163. doi: 10.3390/cancers14205163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giacomini E, Severa M, Cruciani M, et al. Dual effect of Thymosin α 1 on human monocyte-derived dendritic cell in vitro stimulated with viral and bacterial toll-like receptor agonists. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2015;15 Suppl 1:S59–70. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2015.1019460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin X, Tang S, Guo Y, et al. Personalized neoantigen vaccine enhances the therapeutic efficacy of bevacizumab and anti-PD-1 antibody in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2024;73:26. doi: 10.1007/s00262-023-03598-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao Q, Wang Y, Zhao B, et al. Neoantigen Immunotherapeutic-Gel Combined with TIM-3 Blockade Effectively Restrains Orthotopic Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression. Nano Lett. 2022;22:2048–58. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c04977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spranger S, Spaapen RM, Zha Y, et al. Up-regulation of PD-L1, IDO, and T(regs) in the melanoma tumor microenvironment is driven by CD8(+) T cells. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:200ra116. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chanmee T, Ontong P, Konno K, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages as major players in the tumor microenvironment. Cancers (Basel) 2014;6:1670–90. doi: 10.3390/cancers6031670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ribas A, Wolchok JD. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science. 2018;359:1350–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aar4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garcia-Lora A, Algarra I, Garrido F. MHC class I antigens, immune surveillance, and tumor immune escape. J Cell Physiol. 2003;195:346–55. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fang Y, Dou R, Huang S, et al. LAMC1-mediated preadipocytes differentiation promoted peritoneum pre-metastatic niche formation and gastric cancer metastasis. Int J Biol Sci. 2022;18:3082–101. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.70524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma M, Hua S, Min X, et al. p53 positively regulates the proliferation of hepatic progenitor cells promoted by laminin-521. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7:290. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01107-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoo S-A, Leng L, Kim B-J, et al. MIF allele-dependent regulation of the MIF coreceptor CD44 and role in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E7917–26. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1612717113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waldman AD, Fritz JM, Lenardo MJ. A guide to cancer immunotherapy: from T cell basic science to clinical practice. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:651–68. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0306-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Escobar G, Tooley K, Oliveras JP, et al. Tumor immunogenicity dictates reliance on TCF1 in CD8+ T cells for response to immunotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2023;41:1662–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishiga Y, Drainas AP, Baron M, et al. Radiotherapy in combination with CD47 blockade elicits a macrophage-mediated abscopal effect. Nat Cancer. 2022;3:1351–66. doi: 10.1038/s43018-022-00456-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jansen CS, Prokhnevska N, Master VA, et al. An intra-tumoral niche maintains and differentiates stem-like CD8 T cells. Nature New Biol. 2019;576:465–70. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1836-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xie M, Li N, Xu X, et al. The Efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors in Patients with Liver Metastasis of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Real-World Study. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:17. doi: 10.3390/cancers14174333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shemesh CS, Hsu JC, Hosseini I, et al. Personalized Cancer Vaccines: Clinical Landscape, Challenges, and Opportunities. Mol Ther. 2021;29:555–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ott PA, Hu Z, Keskin DB, et al. An immunogenic personal neoantigen vaccine for patients with melanoma. Nature New Biol. 2017;547:217–21. doi: 10.1038/nature22991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu W, Tang H, Li L, et al. Peptide-based therapeutic cancer vaccine: Current trends in clinical application. Cell Prolif. 2021;54:e13025. doi: 10.1111/cpr.13025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Su Q, Song H, Huang P, et al. Supramolecular co-assembly of self-adjuvanting nanofibrious peptide hydrogel enhances cancer vaccination by activating MyD88-dependent NF-κB signaling pathway without inflammation. Bioact Mater. 2021;6:3924–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roth GA, Gale EC, Alcántara-Hernández M, et al. Injectable Hydrogels for Sustained Codelivery of Subunit Vaccines Enhance Humoral Immunity. ACS Cent Sci. 2020;6:1800–12. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Virassamy B, Caramia F, Savas P, et al. Intratumoral CD8+ T cells with a tissue-resident memory phenotype mediate local immunity and immune checkpoint responses in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2023;41:585–601. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.La Manna MP, Di Liberto D, Lo Pizzo M, et al. The Abundance of Tumor-Infiltrating CD8+ Tissue Resident Memory T Lymphocytes Correlates with Patient Survival in Glioblastoma. Biomedicines. 2022;10:10. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10102454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Webb JR, Milne K, Watson P, et al. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes Expressing the Tissue Resident Memory Marker CD103 Are Associated with Increased Survival in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:434–44. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Byrne A, Savas P, Sant S, et al. Tissue-resident memory T cells in breast cancer control and immunotherapy responses. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17:341–8. doi: 10.1038/s41571-020-0333-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ribas A, Dummer R, Puzanov I, et al. Oncolytic Virotherapy Promotes Intratumoral T Cell Infiltration and Improves Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy. Cell. 2017;170:1109–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bruno TC, Ebner PJ, Moore BL, et al. Antigen-Presenting Intratumoral B Cells Affect CD4+ TIL Phenotypes in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Cancer Immunol Res. 2017;5:898–907. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klichinsky M, Ruella M, Shestova O, et al. Human chimeric antigen receptor macrophages for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38:947–53. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0462-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.