Abstract

Background

Racial discrimination is associated with health disparities among Black Americans, a group that has experienced an increase in rates of fatal drug overdose. Prior research has found that racial discrimination in the medical setting may be a barrier to addiction treatment. Nevertheless, it is unknown how experiences of racial discrimination might impact engagement with emergency medical services for accidental drug overdose. This study will psychometrically assess a new measure of hesitancy in seeking emergency medical services for accidental drug overdose and examine prior experiences of racial discrimination and group-based medical mistrust as potential corollaries of this hesitancy.

Method

Cross-sectional survey of 200 Black adults seeking treatment for substance-use-related medical problems (i.e. substance use disorder, overdose, infectious complications of substance use, etc.). Participants will complete a survey including sociodemographic information, the Discrimination in Medical Settings Scale, Everyday Discrimination Scale, Group-Based Medical Mistrust Scale, and an original questionnaire measuring perceptions of and prior engagement with emergency services for accidental drug overdose. Analyses will include exploratory factor analysis, Cronbach’s alpha, and non-parametric partial correlations controlling for age, gender, income, and education.

Conclusions

This article describes a planned cross-sectional survey of Black patients seeking treatment for substance use related health problems. Currently, there is no validated instrument to measure hesitancy in seeking emergency medical services for accidental drug overdose or how experiences of racial discrimination might relate to such hesitancy. Results of this study may provide actionable insight into medical discrimination and the rising death toll of accidental drug overdose among Black Americans.

Keywords: Racial discrimination; substance-related disorders; healthcare disparities; medical mistrust; substance use treatment; social justice; mortality, premature

Introduction

Accidental drug overdose is an increasing cause of death among Black Americans [1–4]. Population-adjusted death rates have come to reflect a growing disparity between Black Americans and their White counterparts. Reasons for the rise in overdose deaths among Black Americans are incompletely understood. Structural and social determinants of health (including systemic racism), as well as unequal access to addiction treatment and harm reduction services have been proposed as contributing factors [5–7]. One less explored possibility is that prior experiences of racial discrimination might influence Black Americans’ engagement with emergency medical services in the event of accidental overdose [5,8].

Black individuals seeking healthcare may be confronted by interpersonal and structural racial discrimination [9,10]. Interpersonal racism is ‘personally mediated,’ or enacted by persons toward other persons, and may include overt or subtle discriminatory behavior that may be purposeful or unconscious [11]. Structural racism includes systems that have been designed to advantage one race over another. These systems are often entrenched by historical, cultural, and legal institutions that facilitate the oppression of minoritized groups [11]. Structural and interpersonal racism have been implicated in a variety of health disparities among Black Americans [9,12,13]. It has been proposed that these traumatic experiences may be related to hesitancy in accessing needed medical care [12,14].

Previous research by our group found that experiences of racial discrimination in the medical setting were common among Black patients seeking substance use treatment [15,16]. Nearly 80% of participants reported having experienced discriminatory treatment by healthcare workers in the past. These experiences were associated with mistrust in the medical system and delaying treatment for substance use in anticipation of racist mistreatment by addiction treatment professionals. Together, these results suggest that history of prior racial discrimination in the medical setting may be an important factor affecting substance use treatment access for Black individuals.

The precipitous rise in overdose deaths among Black Americans adds urgency to the study of racial discrimination in the medical setting as a barrier to care. It is unknown how experiences of racial discrimination might impact engagement with emergency medical services in the event of accidental drug overdose. Based on our prior research, it is plausible that these experiences might be related to hesitancy in accessing potentially life-saving emergency services for themselves or others [15,16].

The major goals of the proposed study are to psychometrically assess and validate a new measure of hesitancy in seeking emergency medical services for accidental drug overdose among Black Americans, and then to assess how experiences of racial discrimination relate to this hesitancy. Specifically, the proposed study will assess potential relationships between a) prior experiences of racial discrimination in the medical setting, b) discrimination in community settings, c) mistrust in the medical system, d) prior experiences of racial discrimination by Emergency Service Providers (Emergency Medical Technicians, Firefighters, Law Enforcement Officers, as well as Doctors, Nurses and other Healthcare Professionals who work in Emergency Departments), and e) perceptions of and prior engagement with emergency care in the event of accidental drug overdose. Respiratory depressing effects can develop within minutes to seconds of opioid overdose, leaving little time to resuscitate overdose victims before terminal hypoxemia, or cardiac arrest [17]. By extension, emergency service response time may influenceoverdose survival, Therefore, an additional aim will be to assess perceptions of emergency response time in relation to a through e above.

Patients and methods

Participants

This cross-sectional survey will recruit two hundred (n = 200) Black adults seeking care for substance-use-related medical problems (i.e. substance use disorder, accidental drug overdose, infectious complications of substance use, etc.). Sample size determination was informed by a priori calculation. Assuming a minimum correlation of 0.30 (Spearman’s rho) between our new scale and existing measures, with a two-tailed analysis at 80% power and p<.05, the study would require 89 participants. However, given that the prevalence of discrimination-related hesitancy to engage with emergency medical services is unknown and it is likely that some participants may not fully complete the survey, we have chosen to conservatively enroll 200 participants.

Regarding recruitment strategy, a convenience sample will be recruited by trained staff from the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center (OSUWMC), an academic medical system in Columbus, Ohio. OSUWMC recruitment locations will include two acute care hospital campuses and a specialty addiction treatment facility. All potential participants will be asked “how would you describe your racial identity?” Individuals who respond their race is Black, African American, or Multiracial with Black or African American as an important part of their racial identity will be offered participation in the study. Recruitment will continue until the desired sample size is met. Inclusion criteria will include age of 18 or older with the aforementioned self-reported racial identities voluntarily seeking treatment for a substance-use-related medical problem. Exclusion criteria will include inability to provide informed consent, inability to read or comprehend survey items, inability to physically operate a tablet computer to complete the electronic survey as assessed by trained staff.

Measures

Participants will be offered an electronic survey including sociodemographic information, the Discrimination in Medical Settings Scale (DMS), Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS), Group-Based Medical Mistrust Scale (GBMMS), and original questions measuring prior experiences of racial discrimination by Emergency Service Providers, and perceptions of emergency services for accidental drug overdose [18–21]. In total, the survey is anticipated to take between 10 and 15 min to complete.

Socio-demographic and other items

Self-reported socio-demographic variables will include age, gender, race, ethnicity, annual income, employment, education, and 3-digit zip code. Carceral history, housing status, and types of substances used in the past six months will also be collected. Carceral history was deemed pertinent as prior work has shown contact with the criminal justice system may increase avoidance of systems that keep formal records [22]. Housing status is linked to overdose and individuals experiencing homelessness have higher risk of overdose [23]. Table 1 presents sociodemographic and other items.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and other items.

| Item | Response |

|---|---|

| Please indicate your race. You may select as many options as apply. | Black / African American; White / Caucasian; American Indian / Alaska Native; Asian; Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

| Please indicate your ethnicity. | Somali*; Hispanic, or Latino; Non-Hispanic |

| What is your age? | Numeric response |

| To which gender do you most identify? | Man – cisgender; Woman – cisgender; Man – transgender; Woman – transgender; Genderqueer / Genderfluid; Non-binary; Agender; Unsure or Questioning; My gender identity is not listed†; Prefer not to say |

| What is the highest level of education you have completed? | Less than 8th grade; Some high school (no diploma); High school diploma or GED; Some college (no degree); Trade/technical/vocational training; Associate degree; Bachelor’s degree; Master’s degree; Professional degree or doctorate degree |

| What is your employment status? | Employed full time (40 or more hours per week); Employed part time (up to 39 h per week); Unemployed and currently looking for work; Unemployed and not currently looking for work; Student; Retired; Unable to work |

| How much money do you earn in a year (before tax) | Less than $20,000; $20,000 to $34,999; $35,000 to $49,999; $50,000 to $74,999; $75,000 to $99,999; Over $100,000 |

| In the past two months, have you been living in stable housing that you own, rent, or stay in as part of a household? | Yes; No |

| In the past, have you been detained in jail or prison? | Yes; No |

| Which substances have you used in the past 6 months? | Fentanyl; Heroin; Prescription opioids (i.e. insert common trade names); Cocaine, or Crack; Methamphetamine; Cannabis; Sedatives (i.e.insert common trade names); Inhalants (i.e. nitrous oxide, gasoline, paint thinner); Alcohol; Other‡; Prefer not to say |

Notes: *The survey will be conducted in Columbus, Ohio – a location with a large Somali population. †If participants respond “My gender identity is not listed” they will have the opportunity to free text their gender identity. ‡If participants respond “other” on the substance use item, they will have the opportunity to free text the substance.

Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS)

Interpersonal racial discrimination - such as disrespectful treatment, threats, harassment, or receiving poorer service – will be measured by EDS [18,24]. The original and still recommended version of this scale is comprised of 9 questions (score range 0-45). The measurement properties of EDS have been extensively studied in diverse populations [25,26]. In aggregate, psychometric evidence for EDS suggests a single-factor structure, and consistent reliability and validity [27]. Responses to EDS are recorded as (5) almost every day, (4) at least once a week, (3) a few times a month, (2) a few times a year, (1) less than once a year, (0) never.

Discrimination in Medical Settings Scale (DMS)

Past experiences of racial discrimination in the medical setting will be assessed by the DMS [19,28,29]. The DMS is a seven-item questionnaire (range 0–35) adapted from the EDS to assess experienced racial discrimination in the context of healthcare. The DMS has been shown to have good internal consistency and test-retest reliability. Questions are prefaced “When GETTING HEALTH CARE have you ever had any of the following things happen to you because of your race or color?” DMS response categories include never (0), rarely (1), sometimes (2), most of the time (3) and always (4). DMS items assess discourtesy, disrespect, poor service, condescension, fear, superiority, and poor listening.

Group-based medical mistrust scale (GBMMS)

Racism-related mistrust in the medical system will be measured using the GBMMS. The GBMMS includes twelve questions, four of which are reverse-coded, (range 12–60) assessing racism-based medical mistrust [20]. The GBMMS exhibits high internal consistency reliability as a whole and for each of its three-factors: Suspicion, Group-based Disparities in Healthcare and Lack of Support from Healthcare Providers. GBMMS response categories include strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), neutral (3), agree (4), strongly agree (5). GBMMS construct validity has been demonstrated by correlations with healthcare avoidance, reduced healthcare access and satisfaction, as well as negative appraisals of preventative health recommendations [20,21,30,31].

Original items regarding perceptions of emergency medical services

Currently, there is no validated instrument to measure perceptions of racial discrimination in the context of emergency medical service for accidental overdose. Therefore, the authors developed original items based on existing instruments such as DMS, GBMMS, and questionnaire items from our own prior published work on this topic [15,16,20,21]. The basis for adapting a new scale from these sources is that these existing scales measure perceptions of racial discrimination in the context of healthcare and substance use treatment – two constructs that relate to our topic of interest. For example, GBMMS item “I have personally been treated poorly or unfairly by doctors or healthcare workers because of my ethnicity” was adapted to “I have personally been treated poorly or unfairly by Emergency Service Providers because of my race or color [20].” Another example is original item “If I called 911 to report a drug overdose, I wouldn’t be surprised to be discriminated against by Emergency Service Providers because of my race or color” was adapted from a questionnaire we used in two prior publications which reads “I wouldn’t be surprised if I am discriminated against because of race or color during my addiction treatment [15,16].” Additionally, the response scale employed mirrors that used in GBMMS and questionnaire items from our own previously published work [15,16,20]. No pilot testing has been conducted as the proposed study will be the first psychometric evaluation of our original survey items. Table 2 includes all the original survey items.

Table 2.

Original survey.

| Instructions: Below is a list of statements dealing with Emergency Service Providers and accidental drug overdose. Please read each item carefully and indicate whether you Strongly Disagree (1), Disagree (2), Neither Agree nor Disagree (3), Agree (4), or Strongly Agree (5) with each statement. Note: Emergency Service Providers means Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs, ambulance drivers), Firefighters, Law Enforcement Officers, as well as Doctors, Nurses and other Healthcare Professionals who work in Emergency Departments. | |||||

| 1) It is safe for people of my race or color to call 911 when they witness a drug overdose. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2) People of my race or color are likely to be arrested if they call 911 to report a drug overdose. * | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3) If I called 911 to report a drug overdose, I wouldn’t be surprised to be discriminated against by Emergency Service Providers because of my race or color. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4) People of my race or color don’t get the same treatment from Emergency Service Providers as other people do when they have a drug overdose. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5) People of my race or color are likely to be arrested when they have a drug overdose. * | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6) If I had an accidental drug overdose, I wouldn’t be surprised to be discriminated against by Emergency Service Providers because of my race or color. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 7a) I have witnessed someone have an accidental drug overdose. | Y | N | |||

| 7b) If YES to question 7a: How many times have you witnessed someone have an accidental drug overdose? | Numeric Response | ||||

| 7c) If YES to question 7a and question7b = 1: Did you call 911 to report this accidental drug overdose? † | Y | N | |||

| 7d) If YES to question 7a and question7b > 1: Did you call 911 EVERY TIME you witnessed an accidental drug overdose? † | Y | N | |||

| 8) If NO to question 7c or 7d: Worry about racial discrimination by Emergency Service Providers was an important reason I did not call 911 to report accidental drug overdose. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 9a) I have personally been treated poorly or unfairly by Emergency Service Providers because of my race or color. | Y | N | |||

| 9b) If YES to question 9: My experience of being mistreated by Emergency Service Providers because of my race or color would make me hesitant to call 911 to report a drug overdose. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 10a) I have seen or heard of people of my race or color be treated poorly or unfairly by Emergency Service Providers because of their race or color. | Y | N | |||

| 10b) If YES to question 10a: Because I have seen or heard of people of my race or color being discriminated against by Emergency Service Providers, I would be hesitant to call 911 to report a drug overdose. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 11a) Participants will be asked to identify their 3-digit zip code on an interactive map of Ohio. | 3-digit zip code | ||||

| 11b) How would you rate the response time of Emergency Service Providers when they are called to an emergency where you live on a scale from 0 (slowest possible) to 10 (fastest possible)? | 0 <->10 | ||||

Notes: *The survey will be conducted in Ohio, a state with a ‘Good Samaritan’ law that provides limited protection against prosecution when individuals experience or report an accidental drug overdose. †In the United States, 911 is the phone number used to call Emergency Service Providers.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics will be used to characterize the sample. Cronbach’s alpha will assess the internal consistency reliability of each scale including the original survey items. Exploratory factor analysis will determine the underlying structure of the original survey items. Finally, non-parametric partial correlations controlling for age, gender and ethnicity will probe potential relationships between prior experiences of racial discrimination in the medical setting (DMS), discrimination in community settings (EDS), mistrust in the medical system (GBMMS), prior experiences of racial discrimination by Emergency Service Providers (original items), perceptions of emergency service response time (controlling for 3-digit zip code), perceptions of and prior engagement with emergency care in the event of accidental drug overdose (original items). Statistical analyses will be completed in SPSS software (Version 28.0, SPSS. Inc.). SPSS software is licensed to OSUWMC and made freely available through this institutional licensing agreement to all faculty, staff, and students.

We hypothesize that the original survey items will exhibit promising initial psychometric properties including acceptable internal consistency reliability, a factor structure with minimal cross-loading of items (if multidimensional) and communalities reflective of the latent factor(s) explaining greater than 70% of variance in responses to the individual items. Additionally, evidence of construct validity will be manifested by the original survey’s correlation with established measures of similar constructs (EDS, GBMMS, DMS). Finally, responses to the original survey will be indicative of hesitancy in seeking emergency medical treatment in the event of accidental drug overdose out of concern for anti-Black racial discrimination by Emergency Service Providers. If confirmed, these hypotheses might inform novel interventions to improve engagement with emergency medical services for drug overdose among Black Americans by addressing structural and interpersonal racism.

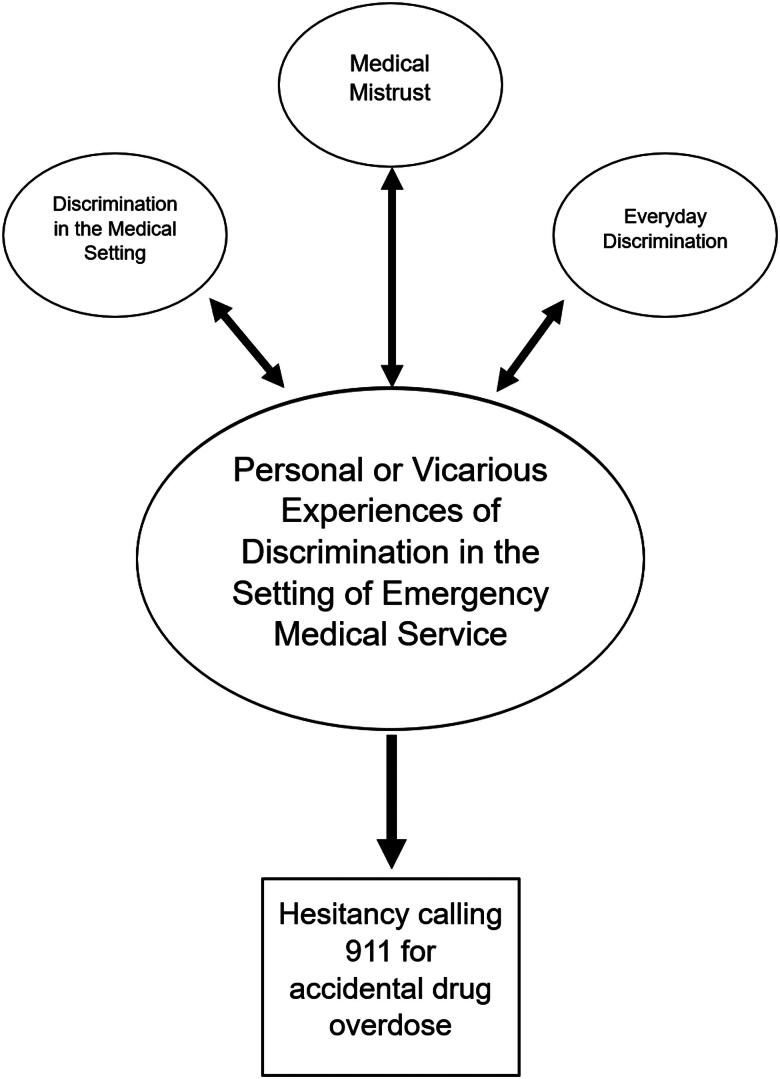

Figure 1 is a conceptual diagram presenting hypothesized relationships between discrimination and hesitancy seeking emergency medical services in the event of accidental drug overdose.

Figure 1.

Conceptual diagram of hypothesized relationships.

Ethics and dissemination

The OSUWMC Institutional Review Board (IRB) gave approval of our protocol 07/23/2023 (IRB# 2023H0238). Participants will provide electronic written informed consent and will be monetarily compensated $15 (US) for their time.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Recognizing and Eliminating Disparities in Addiction through Culturally Informed Healthcare (REACH) program. The REACH Program is made possible by funding to the Academy of Addiction Psychiatry (AAAP) from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) grant no. 1H79TI08135801. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services; nor does mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. government. The funder had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author contributions

All authors have read and approved the manuscript. O. Trent Hall: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing - Original Draft Candice Trimble: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing Stephanie Garcia: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization Sydney Grayson: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing Lucy Joseph: Writing - Review & Editing, Conceptualization and Preparation of Author Response to Reviewer Feedback Parker Entrup: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Original Draft Oluwole Jegedee: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing Jose Perez Martel: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing Jeanette Tetrault: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition Myra Mathis: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing Ayana Jordan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing, Funding acquisition, Supervision

Disclosure statement

Dr. Hall provided expert opinion regarding the opioid overdose crisis to Lumanity, Emergent BioSolutions, and AstraZeneca. All other authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed.

References

- 1.Furr-Holden D, Milam AJ, Wang L, et al. African Americans now outpace whites in opioid-involved overdose deaths: a comparison of temporal trends from 1999 to 2018. Addiction. 2021;116(3):677–683. doi: 10.1111/add.15233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gondré-Lewis MC, Abijo T, Gondré-Lewis TA.. The opioid epidemic: a crisis disproportionately impacting Black Americans and urban communities. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2023;10(4):2039–2053. doi: 10.1007/s40615-022-01384-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman J, Godvin M, Shover CL, et al. Trends in drug overdose deaths among US adolescents, January 2010 to June 2021. JAMA. 2022;327(14):1398–1400. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.2847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall OT, Hall OE, McGrath RP, et al. Years of life lost due to opioid overdose in Ohio: temporal and geographic patterns of excess mortality. J Addict Med. 2020;14(2):156–162. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banks DE, Duello A, Paschke ME, et al. Identifying drivers of increasing opioid overdose deaths among black individuals: a qualitative model drawing on experience of peers and community health workers. Harm Reduct J. 2023;20(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s12954-023-00734-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dayton L, Tobin K, Falade-Nwulia O, et al. Racial disparities in overdose prevention among people who inject drugs. J Urban Health. 2020;97(6):823–830. doi: 10.1007/s11524-020-00439-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goedel WC, Shapiro A, Cerdá M, et al. Association of racial/ethnic segregation with treatment capacity for opioid use disorder in counties in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(4):e203711–e203711. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy NG, Jacka B, Ziobrowski HN, et al. Race, ethnicity, and emergency department post-overdose care. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;131:108588. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, et al. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453–1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter RT, Lau MY, Johnson V, et al. Racial discrimination and health outcomes among racial/ethnic minorities: a meta‐analytic review. J Multicult Couns & Deve. 2017;45(4):232–259. doi: 10.1002/jmcd.12076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Major B, Dovidio JF, Link BG.. The Oxford handbook of stigma, discrimination, and health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Churchwell K, Elkind MSV, Benjamin RM, et al. Call to action: structural racism as a fundamental driver of health disparities: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142(24):e454–e468. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paradies Y, Truong M, Priest N.. A systematic review of the extent and measurement of healthcare provider racism. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2):364–387. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2583-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casagrande SS, Gary TL, LaVeist TA, et al. Perceived discrimination and adherence to medical care in a racially integrated community. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(3):389–395. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0057-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall OT, Jordan A, Teater J, et al. Experiences of racial discrimination in the medical setting and associations with medical mistrust and expectations of care among black patients seeking addiction treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2022;133:108551. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall OT, Bhadra-Heintz NM, Teater J, et al. Group-based medical mistrust and care expectations among black patients seeking addiction treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend Rep. 2022;2:100026. doi: 10.1016/j.dadr.2022.100026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haouzi P, Guck D, McCann M, et al. Severe hypoxemia prevents spontaneous and naloxone-induced breathing recovery after fentanyl overdose in awake and sedated rats. Anesthesiology. 2020;132(5):1138–1150. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB.. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. J Health Psychol 1997;2(3):335–51. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peek ME, Nunez-Smith M, Drum M, et al. Adapting the everyday discrimination scale to medical settings: reliability and validity testing in a sample of African American patients. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(4):502. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shelton RC, Winkel G, Davis SN, et al. Validation of the group-based medical mistrust scale among urban black men. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):549–555. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1288-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB, Winkel G, et al. The Group-Based Medical Mistrust Scale: psychometric properties and association with breast cancer screening. Prev Med. 2004;38(2):209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brayne S. Surveillance and system avoidance: criminal justice contact and institutional attachment. Am Sociol Rev. 2014;79(3):367–391. doi: 10.1177/0003122414530398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamamoto A, Needleman J, Gelberg L, et al. Association between homelessness and opioid overdose and opioid-related hospital admissions/emergency department visits. Soc Sci Med. 2019;242:112585. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Everyday Discrimination Scale [Internet] . [cited 2023 Aug 13]. Available from: https://scholar.harvard.edu/davidrwilliams/node/32397.

- 25.Kim G, Sellbom M, Ford KL.. Race/ethnicity and measurement equivalence of the Everyday Discrimination Scale. Psychol Assess. 2014;26(3):892–900. doi: 10.1037/a0036431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA, et al. Understanding how discrimination can affect health. Health Serv Res. 2019;54 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):1374–1388. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harnois CE, Bastos JL, Campbell ME, et al. Measuring perceived mistreatment across diverse social groups: an evaluation of the Everyday Discrimination Scale. Soc Sci Med. 2019;232:298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benjamins MR, Middleton M.. Perceived discrimination in medical settings and perceived quality of care: a population-based study in Chicago. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0215976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swift SL, Glymour MM, Elfassy T, et al. Racial discrimination in medical care settings and opioid pain reliever misuse in a U.S. cohort: 1992 to 2015. PLoS One. 2019;14(12):e0226490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dale SK, Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, et al. Medical mistrust is related to lower longitudinal medication adherence among African-American males with HIV. J Health Psychol. 2016;21(7):1311–1321. doi: 10.1177/1359105314551950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williamson LD, Bigman CA.. A systematic review of medical mistrust measures. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(10):1786–1794. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed.