Abstract

Background

Recent studies have revealed that inflammatory factors and nutritional status of patients with advanced gastric cancer (AGC) are related to the efficacy of drug therapy and patient prognosis. This study seeks to evaluate the correlation between inflammatory markers, nutritional status, and clinical outcomes of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI)-based therapies among inoperable AGC patients.

Method

This retrospective study included 88 AGC patients who received ICIs combined with chemotherapy. Inflammatory and nutritional indicators from patients before and after two cycles of treatment were collected. Finally, the correlations between these indicators and the clinical response and survival of AGC patients with ICI treatment were examined.

Results

The results revealed that an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) score of 0, neutrophil count to lymphocyte count ratio (NLR) < 2.84, platelet count to lymphocyte count ratio (PLR) < 82.23, lymphocyte count to monocyte count ratio ≥ 2.35, the hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte and platelet score (HALP) ≥ 31.17, prognostic nutritional index (PNI) ≥ 46.53, albumin ≥ 41.65, the decreased HALP group and the decreased PNI group were significantly correlated with improved objective response rate. Additionally, an ECOG PS score of 0, NLR < 2.84 and the decreased HALP group was associated with a superior disease control rate. Meanwhile, an ECOG PS score of 0 (progression-free survival (PFS): P = 0.003; overall survival (OS): P = 0.001) and decreased PLR following treatment (PFS: P = 0.011; OS: P = 0.008) were significant independent predictors of PFS and OS. Lastly, a systemic immune inflammation index ≥ 814.8 was also a positive independent predictor of OS among AGC patients.

Conclusion

Our study supports the potential of inflammatory and nutritional factors to serve as predictors of the efficacy and prognosis in patients undergoing ICI-based therapies for AGC. However, further investigations are necessary to validate these findings.

Keywords: Inflammatory status, Nutritional status, Advanced gastric cancer, Immune checkpoint inhibitors, Clinical response, Prognosis

Introduction

Among the global cancer morbidity and mortality rates published by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) in 2020, gastric cancer ranks as the sixth most prevalent cancer, representing 5.6% of all cases, and is identified as the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths, representing 7.7% of total cancer fatalities (Sung et al., 2021). Due to its atypical clinical symptoms during initial stages, over 60% of patients are diagnosed with advanced gastric cancer (AGC) at initial presentation. Despite receiving chemotherapy and targeted therapy, the 5-year survival rate for AGC patients who are not candidates for surgical intervention remains dismally low at merely 10% (Guan, He & Xu, 2023). Recently, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have emerged as a preferred treatment option for AGC patients. The CheckMate 649 phase III clinical trial demonstrated that in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2)-negative patients with non-operable advanced or metastatic gastric (G), gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) or esophageal adenocarcinoma cancer, nivolumab combined with chemotherapy significantly outperformed chemotherapy alone regarding overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) when administered as first-line treatment to patients exhibiting a Programmed Cell Death Protein-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) combined positive score (CPS) ≥ 5 (Janjigian et al., 2021b). In China, the ORIENT-16 phase III clinical trial provided compelling evidence that sintilimab in combination with chemotherapy can extend OS in patients with PD-L1 CPS ≥ 5 compared to those receiving chemotherapy combined with placebo. Specifically, the median survivals were reported at 18.4 months vs. 12.9 months, respectively (hazard ratio (HR) 0.660; 95% confidence interval (CI) [0.505–0.864]; P = 0.0023). In addition, sintilimab was shown to prolong PFS among patients with PD-L1 CPS ≥ 5 (HR 0.628; 95% CI [0.489–0.805]; P = 0.0002), as well as across all patients (HR 0.636; 95% CI [0.525–0.771]; P < 0.0001) (Xu et al., 2021). Nevertheless, ICI treatment may not be optimal for every patient cohort. Currently, studied factors such as PD-L1 CPS score, tumor mutation burden (TMB), and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) status have been proposed to predict the efficacy of ICI-based therapies. However, their predictive capabilities are not consistently reliable (Liu et al., 2023). Specifically, the research has revealed that different subtypes of gastric cancer (GC) exhibit varying sensitivities to the CPS score. The TPS score demonstrates superior predictive capability compared to the CPS score in determining whether gastric squamous cell carcinoma can benefit from ICI (Yoon et al., 2022). GC patients with a TMB ≥ 10 mutations/Mb showed improved survival benefits in PFS, OS and objective response rate (ORR). However, some patients also present with microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H). Notably, after excluding MSI-H patients, the association between tumor microenvironment (TME) and survival benefit was significantly diminished (Lee et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2019). A study investigating EBV as a predictor of clinical efficacy indicated that GC patients exhibiting partial response (PR) are also PD-L1 positive, which complicates the accuracy of this investigation (Wang et al., 2019). Consequently, there is an urgent need for the development of reliable biomarkers to predict the efficacy of ICI-based therapies in AGC.

In addition to clinicopathological parameters, recent studies have demonstrated that inflammatory and nutritional status in patients with gastric cancer correlates with prognosis and drug efficacy. For example, earlier investigations have established that a decreased systemic immune-inflammation index and an increased prognostic nutritional index served as independent risk factors influencing outcomes for gastric cancer patients. In addition, combining the systemic immune inflammation index with prognostic nutritional index enhanced predictive efficiency (Xu et al., 2022). Furthermore, a higher lymphocyte count to monocyte count ratio (LMR) at baseline was significantly associated with prolonged immune-related PFS and OS among patients with gastric cancer treated with ICIs (Yuan et al., 2022). Systemic immune inflammation index (SII) is calculated by the product of the platelet count (109/L) multiplied by platelet count to lymphocyte count ratio (PLR), suggesting that its potential utility in predicting treatment efficacy and the prognosis for non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with nivolumab (Bauckneht et al., 2021). However, studies examining SII in AGC patients undergoing ICIs treatment are limited. A previous investigation found that gastric adenocarcinoma patients with elevated hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte and platelet score (HALP) scores exhibited longer OS (Sargin & Dusunceli, 2022). Nevertheless, the relationship between HALP score and ICI-based treatments for unresectable AGC remains inadequately explored.

Simultaneously, nutritional status-encompassing body mass index (BMI) and prognostic nutritional index (PNI)-is also associated with treatment efficacy and prognosis in cancer patients receiving ICI therapies. According to a previous study, a higher BMI correlated with favorable clinical outcomes in patients with liver cancer treated with ICIs (Sargin & Dusunceli, 2022). Furthermore, PNI has been identified as an independent prognostic factor for PFS and OS in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with first-line immunotherapy (Chen et al., 2022). At present, relying on a single index is insufficient for evaluating the efficacy of ICIs or predicting the prognosis of AGC patients. In this retrospective study, we analyzed clinical characteristics, alongside levels of inflammatory biomarkers and nutritional status among patients with inoperable AGC to identify correlations between these indicators, the effectiveness of ICI-based therapies, and patient prognosis. This analysis aims to inform clinical decision-making while providing a theoretical foundation for future investigations.

Materials and Methods

Patients

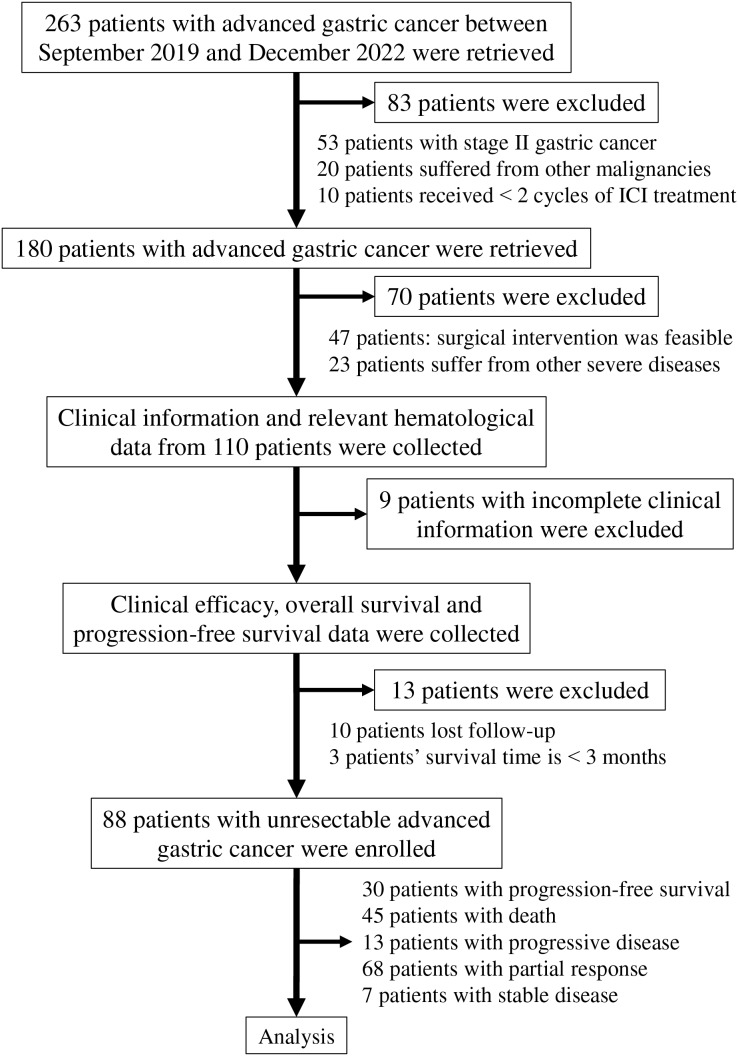

A total of 88 AGC patients diagnosed between September 2019 and December 2022 were included in this retrospective study. Eligible participants received Programmed Cell Death Protein-1 (PD-1) inhibitors in combination with chemotherapy regimens, including SOX, XELOX, and FOLFOX. The PD-1 inhibitors administered to the patients comprised either nivolumab or sintilimab. Additionally, some HER-2-positive patients were treated with trastuzumab. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) Patients aged between 18 and 75 years, with an expected survival time greater than three months; (2) diagnosis of unresectable AGC confirmed by pathological biopsy, with tumor staging determined according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer criteria (8th edition) (Amin et al., 2017); (3) treatment plans established following discussions within a multi-disciplinary team; (4) imaging assessments indicating that surgical intervention was not feasible due to factors such as distant metastases, invasion of peripheral tissues, or invasion of large vessels; inoperable patients classified as clinical stage III were also included; (5) absence of severe underlying hematological, hepatic, or renal diseases prior to the diagnosis of gastric cancer; (6) an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) score ranging from 0 to 1; (7) all patients underwent a minimum of two cycles of treatment involving PD-1 inhibitor combined with chemotherapy; (8) complete and accurate clinical information was provided by all participants who signed a written informed consent form; and (9) evaluation of all lesions adhered to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) (version 1.1) (Eisenhauer et al., 2009). The exclusion criteria consisted of: (1) Patients diagnosed with stage II gastric cancer; (2) patients who refused to provide clinical data or lost follow-up; (3) patients receiving fewer than two cycles of ICI treatment; and (4) patients with identified concurrent malignancies. In accordance with the established inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 263 patients were retrieved, of which 175 patients were excluded from the study (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of the steps and criteria for participant inclusion and exclusion.

Abbreviation used: ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor.

Clinical information, including gender, age, location, clinical pathological stage, histological grade, HER-2 positivity status, MSI status, CPS score, ECOG PS, height, weight, line of therapy received, and relevant hematological indexes, was extracted from the patient’s medical records. This study was approved by the investigational review board of Shenzhen People’s Hospital (LL-KY-2023208-01) and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

Follow-up and assessment

All participants underwent routine follow-up until either death or the end of the follow-up period for this study on December 7, 2022. Baseline indexes, encompassing gender, age, ECOG PS, height, weight, line of therapy, and relevant hematological indexes, were collected within one to three days before treatment. Additional baseline variables, comprising location, clinical pathological stage, histological grade, HER-2 positivity, microsatellite instability (MSI) status, and CPS score, were gathered within one week before treatment commenced. Related inflammatory and nutritional indicators are defined as follows: NLR = neutrophil count to lymphocyte count ratio; NER = neutrophil count to eosinophil count ratio; PLR = platelet count to lymphocyte count ratio; LMR = lymphocyte count to monocyte count ratio; HALP, the hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet score = albumin level (g/L) × hemoglobin level (g/L) × lymphocyte count (109/L)/platelet count (109/L); PNI, prognostic nutritional index = sum of albumin value (g/L) and five times lymphocyte count (109/L); SII, systemic immune-inflammation index = product of the platelet count (109/L) multiplied by PLR. The relevant indicators, including NLR, NER, PLR, LMR, HALP, PNI, SII, albumin level, and total protein level, were re-evaluated within two days following completion of two cycles of treatment.

BMI was computed as body weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2). Using a BMI cut-off value based on the World Health Organization criteria, patients were stratified into an underweight group (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), a normoweight group (18.5 kg/m2 ≤ BMI ≤ 24.9 kg/m2), and an overweight group (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2). Body weight and height were obtained from patients’ medical records at baseline and measured within three days following the initiation of treatment.

RECIST (version 1.1) is regarded as the standard for assessing clinical efficacy, which includes complete response (CR), PR, stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD). The ORR refers to the proportion of patients whose tumors have decreased in size and remained at a specific volume for a designated period, encompassing both CR and PR cases. The disease control rate (DCR) indicates the proportion of patients whose tumors have either shrunk or been maintained at a certain volume over a specified duration, including instances of CR, PR, and SD. PFS denotes the time from the commencement of this study until tumor progression or death occurs. OS represents the interval from study initiation to death.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 22, while GraphPad Prism 8.0 was used for figure generation. The cut-off values for both categorical and continuous variables were determined through Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and subsequently categorized accordingly. ORR and DCR calculations employed chi-square analysis. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method, with univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses performed to identify factors influencing PFS and OS outcomes. A two-sided P value less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics and treatment

The clinical characteristics of the cohort comprising 88 patients are summarized in Table 1. The proportion of male patients (54.4%, n = 48) was marginally higher than that of female patients (45.6%, n = 40). Tumor distribution among cardia, gastric antrum, and gastric body locations was recorded as follows: cardia-nine cases (10.2%), gastric antrum-36 cases (40.9%), gastric body-43 cases (48.9%). Notably, most participants presented with poorly differentiated gastric cancer, constituting approximately 91.1% of the total sample size (n = 82). The majority of patients were HER-2 negative (87.5%, n = 77), MSI-H negative (97.7%, n = 86), had a CPS score lower than one (96.6%, n = 85), and an ECOG PS of 0 (79.5%, n = 70). The number of underweight, normoweight, and overweight gastric cancer patients was 25 (28.4%), 52 (59.1%), and 11 (12.5%), respectively. Notably, while 87.5% of the patients received first-line treatment, only 12.5% underwent conversion therapy due to the inability to achieve R0 resection through surgical intervention.

Table 1. Pretreatment characteristics of 88 patients with advanced gastric cancer.

| Variables | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| ≥60 | 45 (51.1) |

| <60 | 43 (48.9) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 48 (54.4) |

| Female | 40 (45.6) |

| Location | |

| Cardia | 9 (10.2) |

| Antrum | 36 (40.9) |

| Gastric body | 43 (48.9) |

| Histological grade | |

| Poor-differentiated | 82 (91.1) |

| Moderately | 8 (9.1) |

| Clinical stage | |

| III | 11 (12.5) |

| IV | 77 (87.5) |

| HER-2 | |

| Negative | 77 (87.5) |

| Positive | 11 (12.5) |

| MSI-high | |

| Negative | 86 (97.7) |

| Positive | 2 (2.3) |

| CPS | |

| <1 score | 85 (96.6) |

| 1 score | 1 (1.1) |

| 10 score | 2 (2.3) |

| ECOG PS | |

| 0 score | 70 (79.5) |

| 1 score | 18 (20.5) |

| Line of therapy | |

| Conversion therapy | 11 (12.5) |

| First-line therapy | 77 (87.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 25 (28.4) |

| Normoweight (18.5–24.9) | 52 (59.1) |

| Overweight (≥25) | 11 (12.5) |

| Baseline indicatora | |

| NLR | |

| <2.84 | 45 (51.1) |

| ≥2.84 | 43 (48.9) |

| NER | |

| <86.72 | 62 (75.6) |

| ≥86.72 | 20 (24.4) |

| PLR | |

| <82.23 | 10 (11.4) |

| ≥82.23 | 78 (88.6) |

| LMR | |

| <2.35 | 33 (37.5) |

| ≥2.35 | 55 (62.5) |

| HALP | |

| <31.17 | 50 (56.8) |

| ≥31.17 | 38 (43.2) |

| SII | |

| <814.8 | 55 (62.5) |

| ≥814.8 | 33 (37.5) |

| Albumin (g/L) | |

| <41.65 | 46 (52.3) |

| ≥41.65 | 42 (47.7) |

| Total protein (g/L) | |

| <67.70 | 35 (39.8) |

| ≥67.70 | 53 (60.2) |

| PNI | |

| <46.53 | 33 (37.5) |

| ≥46.53 | 55 (62.5) |

Notes:

Baseline indicators are classified into two categories by the cut-off values calculated by Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve.

Abbreviation used: MSI, Microsatellite Instability; CPS, Combined Positive Score; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; BMI, Body Mass Index; NLR, neutrophil count to lymphocyte count ratio; NER, neutrophil count to eosinophil count ratio; PLR, platelet count to lymphocyte count ratio; LMR, lymphocyte count to monocyte count ratio; HALP, the hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte and platelet score; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; SII, systemic immune-inflammation index.

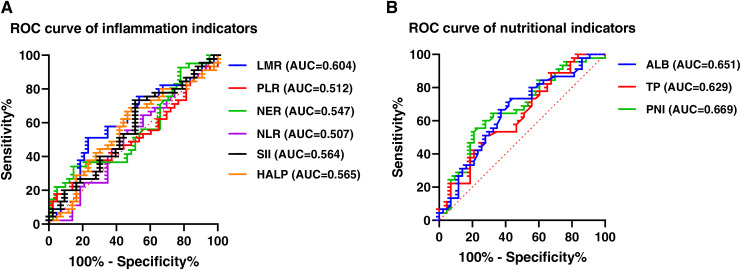

This study employed NLR, NER, PLR, LMR, HALP, and SII as inflammatory indicators for subsequent analyses based on pre-treatment data from the patients. In addition, total protein, albumin levels, BMI, and PNI were examined as nutritional indicators. The cut-off values for each index were established using ROC analysis, and all of them were over 0.5. Specifically, the cut-off values of NLR, NER, PLR, LMR, HALP, SII, total protein, albumin and PNI were 2.84 (area under the curve (AUC) = 0.507), 86.72 (AUC = 0.547), 82.23 (AUC = 0.512), 2.35 (AUC = 0.604), 31.17 (AUC = 0.565), 814.8 (AUC = 0.564), 67.70 (AUC = 0.629), 41.65 (AUC = 0.651) and 46.53 (AUC = 0.669), respectively (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. ROC curve of inflammation and nutritional indexes.

(A) ROC curve of inflammatory indicators. (B) ROC curve of nutritional indicators. Abbreviation used: ROC, Receiver Operating Characteristic; NLR, neutrophil count to lymphocyte count ratio; PLR, platelet count to lymphocyte count ratio; NER, neutrophil count to count eosinophil ratio; LMR, lymphocyte count to monocyte count ratio; ALB, Albumin; TP, Total protein; HALP, the hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte and platelet score; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; SII, systemic immune-inflammation index.

Correlation between pretreatment baseline indexes and clinical response

The relationship between pretreatment baseline indexes and clinical response was analyzed in a cohort of 88 patients. The chi-square test results (Table 2) indicated that an ECOG PS score of 0 correlated with higher ORR (94.3%, P = 0.001) and DCR (98.6%, P = 0.001). Similarly, ORR and DCR were elevated among HER-2-positive and MSI-H individuals with a PD-L1 CPS ≥ 1. However, no significant correlations were observed.

Table 2. Correlation between pretreatment clinical characteristics and clinical response (ORR, DCR) in 88 patients with advanced gastric cancer.

| Responses group | Non-ORR N (%) | ORR N (%) | χ2 (ORR) | P value (ORR) | Non-DCR N (%) | DCR N (%) | χ2 (DCR) | P value (DCR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.259 | 0.611 | 0.812 | 0.367 | ||||

| <60 | 9 (20.5) | 35 (79.5) | 8 (18.2) | 36 (81.8) | ||||

| ≥60 | 11 (25.0) | 33 (75.0) | 5 (11.4) | 39 (88.6) | ||||

| Gender | 0.311 | 0.577 | 0.003 | 0.956 | ||||

| Male | 12 (25.0) | 36 (75.0) | 7 (14.6) | 41 (85.4) | ||||

| Female | 8 (20.0) | 32 (80.0) | 6 (15.0) | 34 (85.0) | ||||

| Histological grade | 0.079 | 0.778 | 1.525 | 0.599 | ||||

| Poor-differentiated | 19 (23.8) | 61 (76.3) | 13 (16.3) | 67 (83.8) | ||||

| Moderately | 1 (12.5) | 7 (87.5) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (100.0) | ||||

| Location | 0.896 | 0.639 | 0.221 | 0.895 | ||||

| Cardia | 1 (11.1) | 8 (88.9) | 1 (11.1) | 8 (88.9) | ||||

| Antrum | 8 (22.2) | 28 (77.8) | 6 (16.7) | 30 (83.3) | ||||

| Gastric body | 11 (25.6) | 32 (74.4) | 6 (14.0) | 37 (86.0) | ||||

| Clinicall stage | 3.697 | 0.063 | 2.179 | 0.357 | ||||

| III | 0 (0.0) | 11 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (100.0) | ||||

| IV | 20 (26.0) | 57 (74.0) | 13 (16.9) | 64 (83.1) | ||||

| HER-2 | 0.592 | 0.442 | 0.013 | 0.910 | ||||

| Negative | 19 (24.7) | 58 (75.3) | 12 (15.6) | 65 (84.4) | ||||

| Positive | 1 (9.1) | 10 (90.9) | 1 (9.1) | 10 (90.9) | ||||

| MSI-high | 0.602 | 0.999 | 0.355 | 0.999 | ||||

| Negative | 20 (23.3) | 66 (76.7) | 13 (15.1) | 73 (84.9) | ||||

| Positive | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | ||||

| CPS | 0.913 | 0.633 | 0.538 | 0.764 | ||||

| <1 score | 20 (23.5) | 65 (76.5) | 13 (15.3) | 72 (84.7) | ||||

| 1 score | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | ||||

| 10 score | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | ||||

| Line of therapy | 3.697 | 0.063 | 2.179 | 0.357 | ||||

| Conversion therapy | 0 (0.0) | 11 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (100.0) | ||||

| First-line therapy | 20 (26.0) | 57 (74.0) | 13 (16.9) | 64 (83.1) | ||||

| ECOG PS | 51.766 | 0.001 | 43.358 | 0.001 | ||||

| 0 score | 4 (5.7) | 66 (94.3) | 1 (1.4) | 69 (98.6) | ||||

| 1 score | 16 (88.9) | 2 (11.1) | 12 (66.7) | 6 (33.3) |

Note:

Abbreviation used: ORR, objective response rate; DCR, disease control rate; N, number of patients; MSI, Microsatellite Instability; CPS, Combined Positive Score; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status.

Regarding the inflammatory indexes presented in Table 3, NLR < 2.84 (93.3%, P = 0.001), PLR < 82.23 (100.0%, P = 0.019), LMR ≥ 2.35 (87.3%, P = 0.004), and HALP ≥ 31.17 (89.50%, P = 0.034) were significantly correlated with a higher ORR, whereas NER did not significantly influence ORR (P = 0.999). In addition, NLR < 2.84 (95.6%, P = 0.013) was associated with a higher DCR. However, no significant associations emerged between other indices regarding DCR outcomes. Compared to a high SII (≥814.8), a low SII (<814.8) was correlated with a higher ORR (83.6% vs. 66.7%) and DCR (87.3% vs. 81.8%), but differences lacked statistical significance (P = 0.066, 0.485).

Table 3. Correlation between baseline inflammatory indicators and clinical response (ORR, DCR) in 88 patients with advanced gastric cancer.

| Responses group | Non-ORR N (%) | ORR N (%) | χ2 (ORR) | P value (ORR) | Non-DCR N (%) | DCR N (%) | χ2 (DCR) | P value (DCR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NLR | 11.719 | 0.001 | 6.214 | 0.013 | ||||

| <2.84 | 3 (6.7) | 42 (93.3) | 2 (4.4) | 43 (95.6) | ||||

| ≥2.84 | 17 (39.5) | 26 (60.5) | 11 (25.6) | 32 (74.4) | ||||

| NER | 0.000 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.999 | ||||

| <86.72 | 13 (21.0) | 49 (79.0) | 9 (14.5) | 53 (85.5) | ||||

| ≥86.72 | 4 (20.0) | 16 (80.0) | 3 (15.0) | 17 (85.0) | ||||

| PLR | 5.523 | 0.019 | 3.412 | 0.065 | ||||

| <82.23 | 0 (0.0) | 10 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (100.0) | ||||

| ≥82.23 | 20 (25.6) | 58 (74.4) | 13 (16.7) | 65 (83.3) | ||||

| LMR | 8.351 | 0.004 | 1.739 | 0.187 | ||||

| <2.35 | 13 (39.4) | 20 (60.6) | 7 (21.2) | 26 (78.8) | ||||

| ≥2.35 | 7 (12.7) | 48 (87.3) | 6 (10.9) | 49 (89.1) | ||||

| HALP | 4.512 | 0.034 | 0.456 | 0.499 | ||||

| <31.17 | 16 (32.0) | 34 (68.0) | 9 (18.0) | 41 (82.0) | ||||

| ≥31.17 | 4 (10.5) | 34 (89.5) | 4 (10.5) | 34 (89.5) | ||||

| SII | 3.382 | 0.066 | 0.487 | 0.485 | ||||

| <814.8 | 9 (16.4) | 46 (83.6) | 7 (12.7) | 48 (87.3) | ||||

| ≥814.8 | 11 (33.3) | 22 (66.7) | 6 (18.2) | 27 (81.8) |

Note:

Abbreviation used: ORR, objective response rate; DCR, disease control rate; N, number of patients; NLR, neutrophil count to lymphocyte count ratio; NER, neutrophil count to eosinophil count ratio; PLR, platelet count to lymphocyte count ratio; LMR, lymphocyte count to monocyte count ratio; HALP, the hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte and platelet score; SII, systemic immune-inflammation index.

Regarding the nutritional indexes (Table 4), the serum albumin level prior to treatment exhibited a correlation with clinical ORR. In other words, ORR was significantly higher in patients with albumin levels exceeding 41.65 g/L (67.4%, P = 0.021). A similarly elevated ORR was observed in patients with a PNI higher than 46.53 (87.3%, P = 0.004). Conversely, pre-treatment total protein level did not demonstrate a significant association with either ORR (P = 0.587) or DCR (P = 0.261). Likewise, no correlation was found between any other nutritional indicators and DCR. Nevertheless, elevated levels of both albumin and PNI were linked to an increased DCR. Additionally, while the ORR and DCR among the overweight group (≥25 kg/m2) appeared numerically superior compared to those in underweight and normoweight groups, these differences did not reach statistical significance. Collectively, our findings suggest that certain inflammatory and nutritional biomarkers assessed prior to treatment may serve as predictors of clinical response following administration of PD-1 inhibitors combined with chemotherapy.

Table 4. Correlation between baseline nutritional indicators and clinical response (ORR, DCR) in 88 patients with advanced gastric cancer.

| Responses group | Non-ORR N (%) | ORR N (%) | χ2 (ORR) | P value (ORR) | Non-DCR N (%) | DCR N (%) | χ2 (DCR) | P value (DCR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | 4.463 | 0.107 | 5.813 | 0.055 | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 8 (32.0) | 17 (68.0) | 7 (28.0) | 18 (72.0) | ||||

| Normoweight (18.5–24.9) | 12 (23.1) | 40 (76.9) | 6 (11.5) | 46 (88.5) | ||||

| Overweight (≥25) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (100.0) | ||||

| Albumin (g/L) | 5.359 | 0.021 | 0.525 | 0.469 | ||||

| <41.65 | 15 (32.6) | 31 (67.4) | 8 (17.4) | 38 (82.6) | ||||

| ≥41.65 | 5 (11.9) | 37 (88.1) | 5 (11.9) | 37 (88.1) | ||||

| Total protein (g/L) | 0.295 | 0.587 | 1.261 | 0.261 | ||||

| <67.70 | 9 (25.7) | 26 (74.3) | 7 (20.0) | 28 (80.0) | ||||

| ≥67.70 | 11 (20.8) | 42 (79.2) | 6 (11.3) | 47 (88.7) | ||||

| PNI | 8.351 | 0.004 | 1.739 | 0.187 | ||||

| <46.53 | 13 (39.4) | 20 (60.6) | 7 (21.2) | 26 (78.8) | ||||

| ≥46.53 | 7 (12.7) | 48 (87.3) | 6 (10.9) | 49 (89.1) |

Note:

Abbreviation used: ORR, objective response rate; DCR, disease control rate; N, number of patients; BMI, Body Mass Index; PNI, prognostic nutritional index.

Correlation between inflammatory and nutritional indexes and clinical response after two cycles of treatment with PD-1 inhibitor and chemotherapy

The relationship between inflammatory as well as nutritional indexes and clinical response was examined in 88 patients with AGC after two cycles of treatment with PD-1 inhibitor in combination with chemotherapy. The findings revealed that patients with decreased HALP scores exhibited a higher ORR (94.9%, P = 0.001) and DCR (94.9%, P = 0.049) (Table 5). Similarly, a higher ORR was observed in the low PNI group (87.5%, P = 0.037). Although the ORR was numerically higher in the high SII group, this difference did not reach statistical significance. Finally, no significant correlations were found between other inflammatory and nutritional indexes with ORR and DCR after two cycles of treatment.

Table 5. Correlation between inflammation and nutritional indicators and clinical response (ORR, DCR) after two cycles of immune checkpoint inhibitors combined with chemotherapy.

| Responses group | Non-ORR N (%) | ORR N (%) | χ2 (ORR) | P value (ORR) | Non-DCR N (%) | DCR N (%) | χ2 (DCR) | P value (DCR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory indexes | ||||||||

| NLR | 0.951 | 0.329 | 2.444 | 0.118 | ||||

| Decrease | 9 (18.8) | 39 (81.3) | 4 (8.3) | 44 (91.7) | ||||

| Increase | 11 (27.5) | 29 (72.5) | 9 (22.5) | 31 (77.5) | ||||

| NER | 0.203 | 0.652 | 0.017 | 0.898 | ||||

| Decrease | 8 (21.1) | 30 (78.9) | 5 (13.2) | 33 (86.8) | ||||

| Increase | 7 (17.1) | 34 (82.9) | 5 (12.2) | 36 (87.8) | ||||

| PLR | 0.020 | 0.887 | 1.488 | 0.222 | ||||

| Decrease | 12 (22.2) | 42 (77.8) | 6 (11.1) | 48 (88.9) | ||||

| Increase | 8 (23.5) | 26 (76.5) | 7 (20.6) | 27 (79.4) | ||||

| LMR | 0.258 | 0.611 | 0.798 | 0.372 | ||||

| Decrease | 12 (21.1) | 45 (78.9) | 7 (12.3) | 50 (87.7) | ||||

| Increase | 8 (25.8) | 23 (74.2) | 6 (19.4) | 25 (80.6) | ||||

| HALP | 10.618 | 0.001 | 3.890 | 0.049 | ||||

| Decrease | 2 (5.1) | 37 (94.9) | 2 (5.1) | 37 (94.9) | ||||

| Increase | 18 (36.7) | 31 (63.3) | 11 (22.4) | 38 (77.6) | ||||

| SII | 2.863 | 0.091 | 0.405 | 0.524 | ||||

| Decrease | 14 (29.8) | 33 (70.2) | 8 (17.0) | 39 (83.0) | ||||

| Increase | 6 (14.6) | 35 (85.4) | 5 (12.2) | 36 (87.8) | ||||

| Nutritional indexes | ||||||||

| Albumin (g/L) | 0.013 | 0.908 | 0.152 | 0.697 | ||||

| Decrease | 10 (22.2) | 35 (77.8) | 6 (13.3) | 39 (86.7) | ||||

| Increase | 10 (23.3) | 33 (76.7) | 7 (16.3) | 36 (83.7) | ||||

| Total protein (g/L) | 0.054 | 0.817 | 0.525 | 0.469 | ||||

| Decrease | 10 (23.8) | 32 (76.2) | 5 (11.9) | 37 (88.1) | ||||

| Increase | 10 (21.7) | 36 (78.3) | 8 (17.4) | 38 (82.6) | ||||

| PNI | 4.368 | 0.037 | 0.723 | 0.395 | ||||

| Decrease | 5 (12.5) | 35 (87.5) | 4 (10.0) | 36 (90.0) | ||||

| Increase | 15 (31.3) | 33 (68.8) | 9 (18.8) | 39 (81.3) |

Note:

Abbreviation used: ORR, objective response rate; DCR, disease control rate; PD-1, Programmed Cell Death Protein-1; N, number of patients; NLR, neutrophil count to lymphocyte count ratio; NER, neutrophil count to eosinophil count ratio; PLR, platelet count to lymphocyte count ratio; LMR, lymphocyte count to monocyte count ratio; HALP, the hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte and platelet score; SII, systemic immune-inflammation index; PNI, prognostic nutritional index.

Prognostic value of inflammatory and nutritional indexes among patients with advanced gastric cancer receiving PD-1 inhibitor and chemotherapy

Subsequently, we analyzed the correlation between the prognosis of patients and baseline indexes prior to treatment, as well as fluctuations in inflammatory and nutritional indexes during therapy. As detailed in Table 6, patients with an ECOG PS score of 0 (HR, 2.460; 95% CI [1.218–4.967]; P = 0.012) had a significantly longer PFS. Moreover, individuals with lower PLR (HR, 2.304; 95% CI [1.227–4.325]; P = 0.009) post-treatment were more inclined to experience prolonged PFS. At the same time, patients with lower NLR (HR, 1.703; 95% CI [0.919–3.154]; P = 0.091) or lower PNI (HR, 1.744; 95% CI [0.926–3.286]; P = 0.085) were tended to have a longer PFS, but the differences were not statistically significant. Next, covariates yielding P values less than 0.1 from univariate Cox regression analysis were incorporated into multivariate Cox regression analysis for further evaluation. According to multivariate Cox regression analysis, both ECOG PS score of 0 (HR, 3.481; 95% CI [1.544–7.850]; P = 0.003) and reduced PLR (HR, 2.660; 95% CI [1.250–5.658]; P = 0.011) emerged as positive independent predictors for prolonged PFS.

Table 6. Univariate and multivariate analyses of PFS and OS.

| PFS | OS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| ECOG = 0 | 2.460 [1.218–4.967] | 0.012 | 3.481 [1.544–7.850] | 0.003 | 3.342 [1.633–6.837] | 0.001 | 4.352 [1.813–10.447] | 0.001 |

| ECOG = 1 | ||||||||

| NLR < 2.84 | 1.245 [0.689–2.249] | 0.467 | 0.743 [0.402–1.373] | 0.343 | ||||

| NLR ≥ 2.84 | ||||||||

| NER < 86.72 | 1.120 [0.584–2.148] | 0.732 | 0.736 [0.379–1.430] | 0.366 | ||||

| NER ≥ 86.72 | ||||||||

| PLR < 82.23 | 0.887 [0.407–1.932] | 0.763 | 0.525 [0.240–1.148] | 0.106 | ||||

| PLR ≥ 82.23 | ||||||||

| LMR < 2.35 | 0.711 [0.395–1.280] | 0.256 | 0.611 [0.334–1.118] | 0.110 | ||||

| LMR ≥ 2.35 | ||||||||

| HALP < 31.17 | 1.158 [0.608–2.204] | 0.655 | 1.235 [0.637–2.395] | 0.532 | ||||

| HALP ≥ 31.17 | ||||||||

| SII < 814.8 | 0.713 [0.365–1.392] | 0.321 | 0.326 [0.157–0.678] | 0.003 | 0.268 [0.109–0.655] | 0.004 | ||

| SII ≥ 814.8 | ||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 0.673 | 0.181 | 0.260 | |||||

| Normoweight (18.5–24.9) | 1.250 [0.661–2.363] | 0.492 | 1.002 [0.540–1.936] | 0.946 | 1.427 [0.715–2.849] | 0.313 | ||

| Overweight (≥25) | 1.551 [0.511–4.708] | 0.438 | 0.373 [0.122–1.139] | 0.083 | 0.545 [0.152–1.946] | 0.350 | ||

| PNI < 46.53 | 0.714 [0.395–1.289] | 0.264 | 0.574 [0.316–1.042] | 0.068 | 0.987 [0.496–1.967] | 0.971 | ||

| PNI ≥ 46.53 | ||||||||

| NLR | 1.703 [0.919–3.154] | 0.091 | 1.459 [0.736–2.892] | 0.279 | 2.222 [1.182–4.179] | 0.013 | 0.995 [0.481–2.058] | 0.989 |

| Decrease | ||||||||

| Increase | ||||||||

| NER | 1.067 [0.554–2.054] | 0.847 | 1.119 [0.584–3.145] | 0.735 | ||||

| Decrease | ||||||||

| Increase | ||||||||

| PLR | 2.304 [1.227–4.325] | 0.009 | 2.660 [1.250–5.658] | 0.011 | 1.979 [1.091–3.590] | 0.025 | 2.479 [1.266–4.854] | 0.008 |

| Decrease | ||||||||

| Increase | ||||||||

| LMR | 1.115 [0.608–2.045] | 0.725 | 1.150 [0.625–2.115] | 0.653 | ||||

| Decrease | ||||||||

| Increase | ||||||||

| HALP | 1.445 [0.788–2.647] | 0.234 | 0.913 [0.500–1.664] | 0.765 | ||||

| Decrease | ||||||||

| Increase | ||||||||

| SII | 1.308 [0.711–2.407] | 0.388 | 1.801 [0.970–3.346] | 0.063 | 1.139 [0.558–2.325] | 0.721 | ||

| Decrease | ||||||||

| Increase | ||||||||

| PNI | 1.744 [0.926–3.286] | 0.085 | 1.568 [0.791–3.106] | 0.198 | 1.400 [0.755–2.595] | 0.285 | ||

| Decrease | ||||||||

| Increase | ||||||||

Note:

Abbreviation used: PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; HR, Hazard Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; NLR, neutrophil count to lymphocyte count ratio; NER, neutrophil count to eosinophil count ratio; PLR, platelet count to lymphocyte count ratio; LMR, lymphocyte count to monocyte count ratio; HALP, the hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte and platelet score; SII, systemic immune-inflammation index; BMI, Body Mass Index; PNI, prognostic nutritional index.

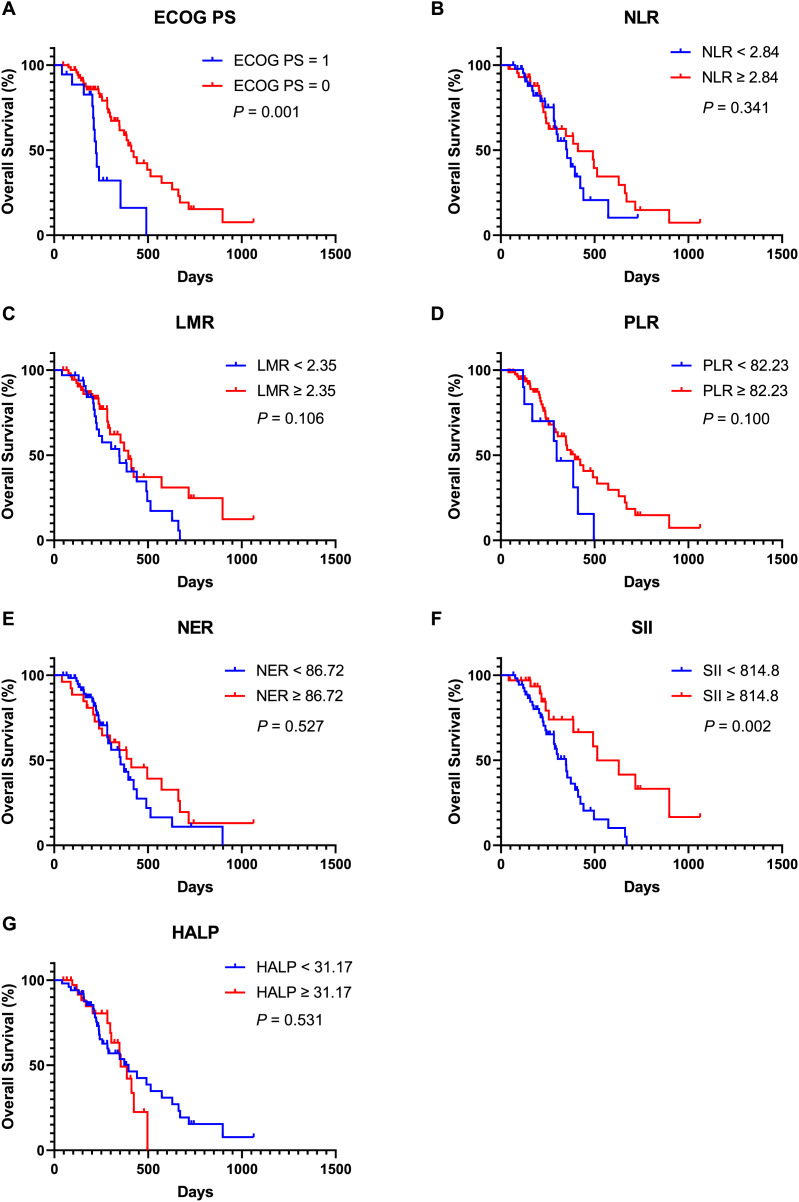

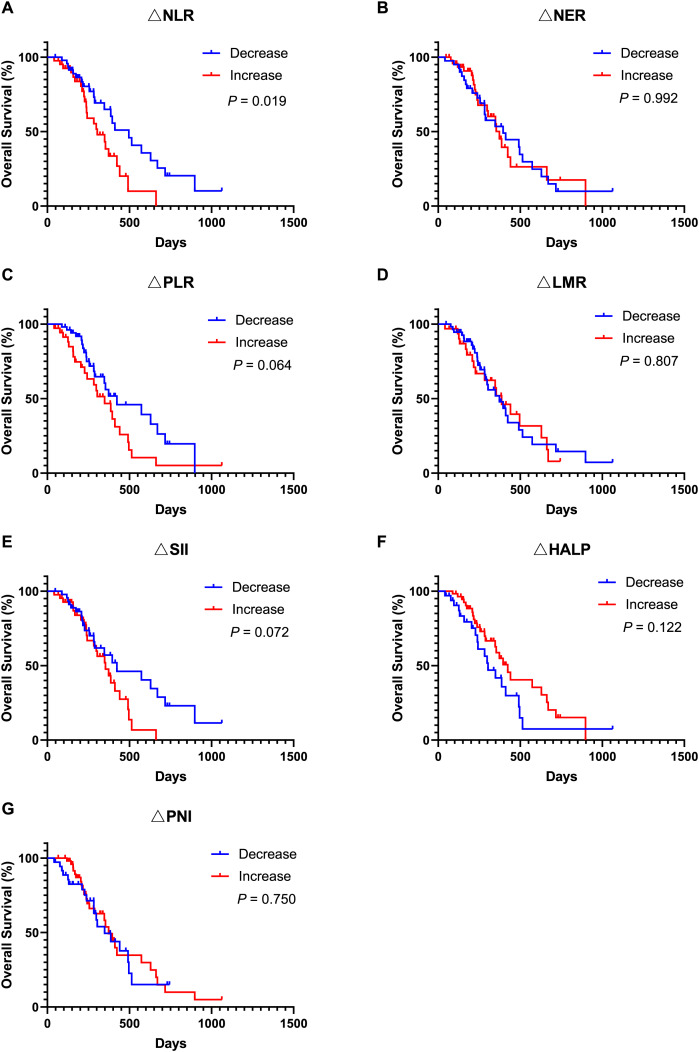

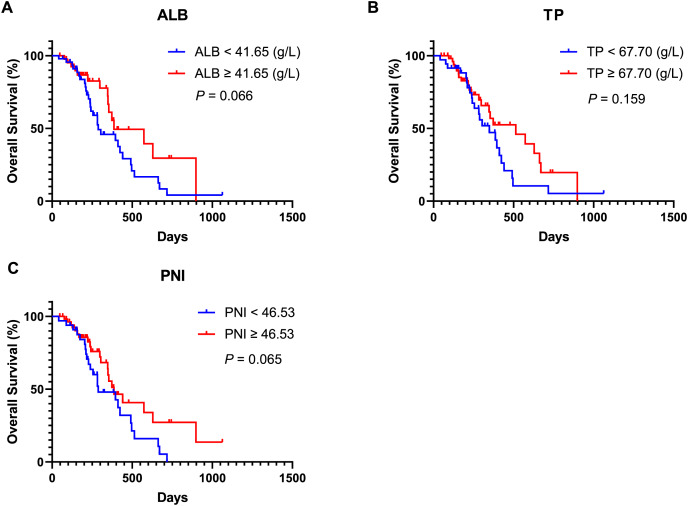

Moreover, univariate Cox regression analysis indicated that an ECOG PS score of 0 (HR, 3.342; 95% CI [1.633–6.837]; P = 0.001), SII ≥ 814.8 (HR, 0.326; 95% CI [0.157–0.678]; P = 0.003), lower NLR (HR, 2.222; 95% CI [1.182–4.179]; P = 0.013), and lower PLR (HR, 1.979; 95% CI [1.091–3.590]; P = 0.025) were associated with improved OS. Covariates exhibiting a P value less than 0.1 were subsequently included in the multivariate Cox regression analysis. The findings revealed that an ECOG PS score of 0 (HR, 4.352; 95% CI [1.813–10.447]; P = 0.001), SII ≥ 814.8 (HR, 0.268; 95% CI [0.109–0.655]; P = 0.004) and lower PLR (HR, 2.479; 95% CI [1.266–4.854]; P = 0.008) served as significant independent predictors of OS. Additionally, Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated that patients with an ECOG PS score of 0 (Fig. 3A, P = 0.001) and SII ≥ 814.8 (Fig. 3F, P = 0.002) experienced longer OS durations. In contrast, other inflammatory and nutritional indices did not correlate with OS outcomes (Figs. 3–5), apart from lower NLR post-treatment group (Fig. 5A, P = 0.019). Collectively, our observations suggest that baseline ECOG PS score, SII, and PLR are prognostic indicators for AGC patients undergoing PD-1 inhibitors in combination with chemotherapy.

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier curve for OS in AGC patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors combined with chemotherapy stratified based on ECOG PS and baseline inflammation indicators.

(A) Kaplan-Meier curve for OS in patients stratified based on ECOG PS. (B) Kaplan-Meier curve for OS in patients stratified based on baseline NLR. (C) Kaplan-Meier curve for OS in patients stratified based on baseline LMR. (D) Kaplan-Meier curve for OS in patients stratified based on baseline PLR. (E) Kaplan-Meier curve for OS in patients stratified based on baseline NER. (F) Kaplan-Meier curve for OS in patients stratified based on baseline SII. (G) Kaplan-Meier curve for OS in patients stratified based on baseline HALP. P < 0.05 is considered statistically significant. Abbreviation used: AGC, advanced gastric cancer; OS, overall survival; PD-1, Programmed Cell Death Protein-1; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; NLR, neutrophil count to lymphocyte count ratio; LMR, lymphocyte count to monocyte count ratio; PLR, platelet count to lymphocyte count ratio; NER, neutrophil count to eosinophil count ratio; SII, systemic immune-inflammation index; HALP, the hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte and platelet score.

Figure 5. Kaplan-Meier curve for OS in AGC patients after receiving 2 cycles of immune checkpoint inhibitors combined with chemotherapy stratified by inflammation and nutritional indicator changes.

(A) Kaplan-Meier curve for OS in patients stratified based on NLR change. (B) Kaplan-Meier curve for OS in patients stratified based on NER change. (C) Kaplan-Meier curve for OS in patients stratified based on PLR change. (D) Kaplan-Meier curve for OS in patients stratified based on LMR change. (E) Kaplan-Meier curve for OS in patients stratified based on SII change. (F) Kaplan-Meier curve for OS in patients stratified based on HALP change. (G) Kaplan-Meier curve for OS in patients stratified based on PNI change. P < 0.05 is considered statistically significant. Abbreviation used: AGC, advanced gastric cancer; OS, overall survival; PD-1, Programmed Cell Death Protein-1; ∆NLR, changes of neutrophil count to lymphocyte count ratio; ∆NER, changes of neutrophil count to eosinophil count ratio; ∆PLR, changes of platelet count to lymphocyte count ratio; ∆LMR, changes of lymphocyte count to monocyte count ratio; ∆HALP, changes of the hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte and platelet score; ∆PNI, changes of prognostic nutritional index; ∆SII, changes of systemic immune-inflammation index.

Figure 4. Kaplan-Meier curve for OS in AGC patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors combined with chemotherapy stratified based on baseline nutritional indicators.

(A) Kaplan-Meier curve for OS in patients stratified based on baseline ALB. (B) Kaplan-Meier curve for OS in patients stratified based on baseline TP. (C) Kaplan-Meier curve for OS in patients stratified based on baseline PNI. P < 0.05 is considered statistically significant. Abbreviation used: AGC, advanced gastric cancer; OS, overall survival; PD-1, Programmed Cell Death Protein-1; ALB, Albumin; TP, Total protein; PNI, prognostic nutritional index.

Discussion

Despite advancements in multidisciplinary diagnostic approaches and treatment modalities that have significantly improved the prognosis for patients with gastric cancer in recent years, the outlook for AGC remains dismal due to substantial heterogeneity driven by complex molecular mechanisms underlying this malignancy. According to The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) classification system, gastric cancer can be categorized into several subtypes: EBV, MSI, genome stability (GS), and chromosomal instability (CIN). Each subtype exhibits distinct prognoses necessitating tailored therapeutic strategies (Zhang et al., 2023b). Recent progresses in understanding cancer molecular etiology and biology have led to the development of novel targeted therapies capable of improving outcomes for patients with gastric cancer expressing specific molecular markers (Guan, He & Xu, 2023). For instance, the TOGA clinical trial established that combining trastuzumab with chemotherapy (fluorouracil/cisplatin) significantly prolonged OS compared to chemotherapy alone among patients with HER2-positive advanced G/GEJ cancer (13.8 vs. 11.1 months: HR, 0.74, 95% CI [0.60–0.91], P = 0.0046) (Rha & Chung, 2023). Another clinical trial involving CLDN18.2 targeted Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T cells reported a six-month OS rate of approximately 81%, along with ORR at around 57% and DCR at about 75% within previously treated CLDN18.2-positive digestive system cancers (NCT03874897) (Qi et al., 2022). Nevertheless, further clinical trials are warranted to validate these findings.

Moreover, ICIs have shown certain efficacy across various malignancies, including lung cancer and liver cancer, and play a pivotal role in treating AGC (Kciuk et al., 2023). Recent studies have identified associations between biomarkers such as PD-L1 CPS, MSI-H, EBV and the efficacy of ICIs in gastric cancer (Goodman et al., 2023). The Keynote-059 trial confirmed that the efficacy of pembrolizumab in treating recurrent AGC was significantly higher in patients with positive PD-L1 CPS (Bang et al., 2019). The Keynote-062 trial, which exclusively enrolled patients with a PD-L1 CPS ≥ 1, demonstrated that the ORR was higher in the pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy group. However, the OS (PD-L1 CPS ≥ 1 or CPS ≥ 10) and PFS (PD-L1 CPS ≥ 1) of patients in the combination therapy group was not superior to that of the chemotherapy alone group (Shitara et al., 2020). Consequently, the significance of PD-L1 CPS ≥ 1 in patients receiving ICIs combined with chemotherapy for the treatment of AGC remains unclear. However, recent studies have suggested that G/GEJ patients with non-diffuse tumors or without peritoneal metastasis exhibiting low PD-L1 expression, may obtain significant benefits from the combination of ICIs and chemotherapy, enhancing their clinical response and prolonging their PFS (Sun et al., 2024). In patients with deficient mismatch repair (dMMR)/MSI-H resectable G/GEJ adenocarcinoma, neoadjuvant therapy utilizing nivolumab and ipilimumab has proven effective, achieving a high pCR rate of 58.6% (André et al., 2023). Nevertheless, not all patients with dMMR/MSI-H benefit from immunotherapy due to the relatively low prevalence of these molecular subtypes within gastric cancer. Our research indicated that both ORR and DCR were elevated among MSI-H patients exhibiting a PD-L1 CPS ≥ 1. Notably, both ORR and DCR reached an impressive 100%, although no significant correlation was observed between them. Additionally, our study revealed that HER-2-positive AGC patients also achieved an ORR and DCR of 100%, but these differences lacked statistical significance, potentially due to the limited sample size in this study. In the phase III Keynote-811 trial assessing the efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab combined with trastuzumab and chemotherapy for unresectable or metastatic HER2-positive G/GEJ adenocarcinoma, there was a notable 22.7% increase in ORR within the pembrolizumab cohort compared to the placebo group (74.4% vs. 51.9%, 95% CI [11.2–33.7]; P = 0.00006) (Janjigian et al., 2021a). These results suggest that HER-2 may serve as a predictive biomarker for ICI-based treatment efficacy in HER2-positive AGC patients.

In addition, our study revealed that an ECOG PS score of 0 was correlated with higher ORR and DCR. Furthermore, a positive correlation was observed between the ECOG PS score and the efficacy of immunotherapy. Consistently, both univariate and multivariate analyses established that an ECOG PS score of 0 was associated with improved PFS and OS (P < 0.05). These results collectively suggest that the ECOG PS score serves as an independent prognostic indicator for AGC patients treated with ICI-based therapies, aligning with observations from previous studies (Goutam et al., 2022; Schlintl et al., 2022). While these clinicopathological features offer valuable insights into the clinical application of ICI-based treatments, further studies are warranted to identify novel biomarkers for predicting responses to ICIs. Such efforts aim to enhance the development of accurate or personalized treatment strategies designed to improve ICIs efficacy in AGC.

The inflammatory state plays a crucial role in the initiation and development of cancer by disrupting cellular signaling pathways, thereby facilitating the initiation, invasion, and progression of cancer. Various inflammatory molecules have been implicated in cancer development through mechanisms such as immunosuppression, tissue remodeling, and DNA damage. The TME is significantly influenced by inflammatory cells and their secretions, which promote tumor growth, survival, and migration (Nigam et al., 2023). In clinical practice, inflammatory markers obtained from peripheral blood can conveniently reflect the body’s inflammatory status. Recent studies have demonstrated that these inflammatory markers not only correlate with prognosis in cancer patients but also influence the efficacy of ICI-based regimens (Tian et al., 2022). In metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) patients treated with immunotherapy, low baseline NLR along with an early decrease in NLR were significantly correlated with favorable outcomes. Additionally, baseline LMR emerged as an independent predictor of OS (Ouyang et al., 2023). Another study indicated that advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients with a low PLR exhibited longer OS and PFS, as well as higher ORR and DCR following immunotherapy (Zhou et al., 2022). Our study revealed that low NLR, PLR, and increased LMR before treatment were associated with a higher ORR in AGC patients who received ICI-based treatments, but only the lower NLR was correlated with DCR. Furthermore, a decline in NLR was linked to numerically higher ORR and DCR, although these differences did not reach statistical significance. Moreover, NLR after one cycle of treatment emerged as an independent factor influencing ORR in metastatic NSCLC patients undergoing immunotherapy (Zhu et al., 2022). The absolute lymphocyte count may serve as a predictor for the efficacy of ICI therapies, given its correlation with response among NSCLC patients who received ICIs (Yuan et al., 2021). In a previous study’s initial radiological evaluation, a 20% reduction in NLR was correlated with prolonged OS in patients with advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma who received camrelizumab (Wang et al., 2022). However, our study did not establish significant relationship between NLR, PLR, NER, and LMR and prognosis among AGC patients receiving immunotherapy. Unexpectedly, we found that a decrease in PLR post-treatment correlated positively with PFS and OS. Consequently, both univariate and multivariate analyses identified PLR as an independent prognostic predictor. Another retrospective study revealed that high PLR constituted an independent risk factor for PFS and OS among advanced metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients receiving ICIs (Liu et al., 2022). Among BRAF wild-type metastatic melanoma patients treated with ICIs, those exhibiting elevated PLR were more likely to experience poorer PFS, OS, and DCR (Guida et al., 2022). Therefore, a reduction in PLR after treatment may serve as an indicator of prognosis for AGC patients treated with ICIs. Lately, the inflammatory markers of HALP and SII have garnered extensive attention in evaluating the efficacy and prognosis of cancer patients undergoing immunotherapy. Among advanced NSCLC patients receiving ICIs combined with chemotherapy as first-line treatment, results indicated that higher HALP scores and lower SII were associated with improved ORR (P = 0.001, 0.009) (Wang et al., 2022). A correlation was also observed between elevated HALP scores and higher ORR in AGC patients who received ICI treatments (P = 0.034). Notably, a decrease in HALP scores after two cycles of treatment correlated with a higher ORR. A low SII was associated with a numerically higher ORR, but this difference was not statistically significant. According to a previous study, AGC patients receiving ICIs who had high SII exhibited poorer prognosis compared to those with low SII (P < 0.001) (Wang et al., 2022). In our analysis, baseline SII showed a significant correlation with OS but not PFS. Furthermore, while patients presenting high baseline SII had longer OS, fluctuations in SII after treatment did not correlate significantly with either PFS or OS. Conversely, our study showed that although baseline SII was not linked to PFS, high SII of 6 weeks after treatment was significantly associated with prolonged PFS and OS (P < 0.05). Notably, an earlier study also highlighted that both baseline and post-treatment SII were unrelated to PFS and OS among patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with anti-PD-1 antibodies (P > 0.05) (He et al., 2023). Despite the association between HALP scores and the efficacy of ICI-based therapies in AGC patients, further research is warranted to elucidate the predictive and prognostic value of both HALP and SII for the treatment of AGC patients receiving ICIs.

At present, the relationship between nutritional status, immune function, and the efficacy of ICIs in cancer has attracted increasing attention. Nutrition plays a crucial role implicated in the prevention, development, and management of various cancers. Indeed, numerous studies have established that T-cell functions and cancer progression are affected by nutrition factors (Zhou, Wang & Yuan, 2023). BMI is a commonly used indicator of nutritional status, and previous research has identified a positive correlation between BMI and the efficacy of ICIs across various cancers, and higher BMI has been associated with a more favorable prognosis (Incorvaia et al., 2023; Yan et al., 2023). Furthermore, ORR and DCR appear to be higher in patients with high BMI. However, our study did not find a significant correlation between BMI and prognosis. A previous investigation revealed a significant correlation between baseline PNI, OS and PFS. In contrast, poor nutritional status before treatment was negatively correlated with clinical outcomes in patients with advanced head and neck cancer receiving immunotherapy (Zhang et al., 2023a). These inconsistent results may be attributed to the inappropriate use of BMI as a surrogate for body composition-a phenomenon referred to as the obesity paradox. PNI serves as another important nutritional indicator affected by serum albumin level and lymphocyte count. Earlier research demonstrated that an albumin level > 3.5 g/dL and lymphocyte count > 1,000/μL were independent risk factors for patients previously treated for unresectable or recurrent gastric cancer who received nivolumab (Guller et al., 2021). In addition, another study revealed that higher PNI correlates positively with clinical outcomes, suggesting its potential utility as a biomarker for screening AGC patients who may respond favorably to ICIs (Sato et al., 2021). Our study further corroborated that high albumin levels and PNI were associated with increased ORR. Compared to patients exhibiting an increased PNI after two cycles of treatment, those demonstrating decreased PNI had higher ORR. A retrospective analysis identified a high PNI as an advantageous factor for OS and PFS among advanced lung cancer patients receiving ICI-based therapies (Yan et al., 2023). Nevertheless, we did not validate this finding within our AGC patient cohort. Therefore, further clinical studies are needed to validate the relationship between PNI and the prognosis of patients with AGC undergoing treatment with ICIs.

Certain indexes, such as HALP, PNI, and SII, may exhibit a degree of relevance in assessing the prognosis of patients with AGC, because they share common calculation indicators. It has been suggested that the combined SII-PNI score can serve as an independent predictor of OS and disease-free survival in individuals with locally advanced gastric cancer following chemotherapy (Ding et al., 2024). Furthermore, some indicators may represent secondary responses to others. For instance, nutritional status frequently influences the quantity of inflammatory cells (Tur-Martínez et al., 2024). However, our preliminary studies were conducted separately. Future research necessitates the collection of more clinical data and further exploration to develop improved predictive models and to elucidate the relationship between these inflammatory indexes and nutritional parameters. In addition, the sample size in this retrospective study was relatively small, necessitating additional confirmation in a larger cohort. In particular, we aim to enhance our ability to predict the efficacy and prognosis of ICI therapy combined with chemotherapy for inoperable AGC by developing a predictive model that integrates inflammatory and nutrition-related indicators. Consequently, this study lays a solid foundation for our future research endeavors.

Conclusions

Inflammatory and nutritional biomarkers, such as NLR, PLR, LMR, albumin, HALP score, and PNI, have the potential to predict the clinical efficacy of ICI-based therapies in AGC patients. These findings offer promising avenues for enhancing the precision of immunotherapy within this patient population. Additionally, PLR and SII have been identified as prognostic biomarkers for AGC patients receiving ICI-based treatments. Therefore, assessing inflammation and nutritional status is crucial for managing AGC patients undergoing immunotherapy. Future interventions aimed at addressing these factors may further improve both the efficacy and prognosis of immunotherapy in this patient cohort.

Supplemental Information

Abbreviations

- AGC

advanced gastric cancer

- BMI

body mass index

- CAR

Chimeric Antigen Receptor

- CI

confidence interval

- CPS

combined positive score

- CR

complete response

- DCR

disease control rate

- dMMR

deficient mismatch repair

- EBV

Epstein-Barr virus

- ECOG PS

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status

- G

gastric

- GEJ

gastroesophageal junction

- HALP

the hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte and platelet score

- HER-2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- HR

hazard ratio

- IARC

International Agency for Research on Cancer

- ICIs

immune checkpoint inhibitors

- LMR

lymphocyte count to monocyte count ratio

- MSI-H

microsatellite instability-high

- NER

neutrophil count to eosinophil count ratio

- NLR

neutsmall cell lung cancer

- ORR

objerophil count to lymphocyte count ratio

- NSCLC

non-ctive response rate

- OS

overall survival

- PD

progressive disease

- PD-1

Programmed Cell Death Protein-1

- PD-L1

Programmed Cell Death Protein-Ligand 1

- PFS

progression-free survival

- PLR

platelet count to lymphocyte count ratio

- PNI

prognostic nutritional index

- PR

partial response

- RECIST

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

- ROC

Receiver Operating Characteristic

- SD

stable disease

- SII

systemic immune inflammation index

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- TME

tumor microenvironment

Funding Statement

This study was supported by Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province of China (grant number A2023274) and Bethune Charitable Foundation. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Meiqin Zhu conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Lin-Ting Zhang conceived and designed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Wenjuan Lai conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Fang Yang performed the experiments, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Danyang Zhou performed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Ruilian Xu conceived and designed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Gangling Tong conceived and designed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Human Ethics

The following information was supplied relating to ethical approvals (i.e., approving body and any reference numbers):

This study was approved by the investigational review board of Shenzhen People’s Hospital (LL-KY-2023208-01) and all patients signed the informed consent form.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw measurements are available in the Supplemental File.

References

- Amin et al. (2017).Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Comption CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR, Winchester DP. The eighth edition ajcc cancer stating manual: continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2017;67(2):93–99. doi: 10.3322/caac.21388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- André et al. (2023).André T, Tougeron D, Piessen G, De la Fouchardière C, Louvet C, Adenis A, Jary M, Tournigand C, Aparicio T, Desrame J, Lièvre A, Garcia-Larnicol ML, Pudlarz T, Cohen R, Memmi S, Vernerey D, Henriques J, Lefevre JH, Svrcek M. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus ipilimumab and adjuvant nivolumab in localized deficient mismatch repair/microsatellite instability-high gastric or esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma: the GERCOR NEONIPIGA phase II Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2023;41(2):255–265. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.00686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang et al. (2019).Bang YJ, Kang YK, Catenacci DV, Muro K, Fuchs CS, Geva R, Hara H, Golan T, Garrido M, Jalal SI, Borg C, Doi T, Yoon HH, Savage MJ, Wang J, Dalal RP, Shah S, Wainberg ZA, Chung H. Pembrolizumab alone or in combination with chemotherapy as first-line therapy for patients with advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: results from the phase II nonrandomized KEYNOTE-059 study. Gastric Cancer. 2019;22:828–837. doi: 10.1007/s10120-018-00909-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauckneht et al. (2021).Bauckneht M, Genova C, Rossi G, Rijavec E, Dal Bello MG, Ferrarazzo G, Tagliamento M, Donegani MI, Biello F, Chiola S, Zullo L, Raffa S, Lanfranchi F, Cittadini G, Marini C, Lopci E, Sambuceti G, Grossi F, Morbelli S. The role of the immune metabolic prognostic index in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in radiological progression during treatment with nivolumab. Cancers. 2021;13(13):3117. doi: 10.3390/cancers13133117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen et al. (2022).Chen J, Lu L, Qu C, A G, Deng F, Cai M, Chen W, Zheng L, Chen J. Body mass index, as a novel predictor of hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with Anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Frontiers in Medicine. 2022;9:981001. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.981001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding et al. (2024).Ding P, Yang J, Wu J, Wu H, Sun C, Chen S, Yang P, Tian Y, Guo H, Liu Y, Meng L, Zhao Q. Combined systemic inflammatory immune index and prognostic nutrition index as chemosensitivity and prognostic markers for locally advanced gastric cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 2024;24:1014. doi: 10.1186/s12885-024-12771-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhauer et al. (2009).Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, Rubinstein L, Shankar L, Dodd L, Kaplan R, Lacombe D, Verweij J. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1.) European Journal of Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman et al. (2023).Goodman RS, Jung S, Balko JM, Johnson DB. Biomarkers of immune checkpoint inhibitor response and toxicity: challenges and opportunities. Immunological Reviews. 2023;318(1):157–166. doi: 10.1111/imr.13249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goutam et al. (2022).Goutam S, Stukalin I, Ewanchuk B, Sander M, Ding PQ, Meyers DE, Heng D, Cheung WY, Cheng T. Clinical factors associated with long-term survival in metastatic melanoma treated with anti-PD1 alone or in combination with ipilimumab. Current Oncology. 2022;29(10):7695–7704. doi: 10.3390/curroncol29100608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan, He & Xu (2023).Guan WL, He Y, Xu RH. Gastric cancer treatment: recent progress and future perspectives. Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 2023;16:57. doi: 10.1186/s13045-023-01451-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guida et al. (2022).Guida M, Bartolomeo N, Quaresmini D, Quaglino P, Madonna G, Pigozzo J, Di Giacomo AM, Minisini AM, Tucci M, Spagnolo F, Occelli M, Ridolfi L, Queirolo P, De Risi I, Valente M, Sciacovelli AM, Chiarion Sileni V, Ascierto PA, Stigliano L, Strippoli S. Basal and one-month differed neutrophil, lymphocyte and platelet values and their ratios strongly predict the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors immunotherapy in patients with advanced BRAF wild-type melanoma. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2022;20:159. doi: 10.1186/s12967-022-03359-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guller et al. (2021).Guller M, Herberg M, Amin N, Alkhatib H, Maroun C, Wu E, Allen H, Zheng Y, Gourin C, Vosler P, Tan M, Koch W, Eisele D, Seiwert T, Fakhry C, Pardoll D, Zhu G, Mandal R. Nutritional status as a predictive biomarker for immunotherapy outcomes in advanced head and neck cancer. Cancers. 2021;13(22):5772. doi: 10.3390/cancers13225772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He et al. (2023).He M, Chen ZF, Zhang L, Gao X, Chong X, Li HS, Shen L, Ji J, Zhang X, Dong B, Li ZY, Lei T. Associations of subcutaneous fat area and Systemic Immune-inflammation Index with survival in patients with advanced gastric cancer receiving dual PD-1 and HER2 blockade. Journal for Immunotherapy of Cancer. 2023;11(6):e007054. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2023-007054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incorvaia et al. (2023).Incorvaia L, Dimino A, Algeri L, Brando C, Magrin L, De Luca I, Pedone E, Perez A, Sciacchitano R, Bonasera A, Bazan Russo TD, Li Pomi F, Peri M, Gristina V, Galvano A, Giuffrida D, Fazio I, Toia F, Cordova A, Florena AM, Giordano A, Bazan V, Russo A, Badalamenti G. Body mass index and baseline platelet count as predictive factors in Merkel cell carcinoma patients treated with avelumab. Frontiers in Oncology. 2023;13:1141500. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1141500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janjigian et al. (2021a).Janjigian YY, Kawazoe A, Yañez P, Li N, Lonardi S, Kolesnik O, Barajas O, Bai Y, Shen L, Tang Y, Wyrwicz LS, Xu J, Shitara K, Qin S, Van Cutsem E, Tabernero J, Li L, Shah S, Bhagia P, Chung HC. The KEYNOTE-811 trial of dual PD-1 and HER2 blockade in HER2-positive gastric cancer. Nature. 2021a;600(7890):727–730. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04161-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janjigian et al. (2021b).Janjigian YY, Shitara K, Moehler M, Garrido M, Salman P, Shen L, Wyrwicz L, Yamaguchi K, Skoczylas T, Campos Bragagnoli A, Liu T, Schenker M, Yanez P, Tehfe M, Kowalyszyn R, Karamouzis MV, Bruges R, Zander T, Pazo-Cid R, Hitre E, Feeney K, Cleary JM, Poulart V, Cullen D, Lei M, Xiao H, Kondo K, Li M, Ajani JA. First-line nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric, gastro-oesophageal junction, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (CheckMate 649): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2021b;398(10294):27–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00797-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kciuk et al. (2023).Kciuk M, Yahya EB, Mohamed Ibrahim Mohamed M, Rashid S, Iqbal MO, Kontek R, Abdulsamad MA, Allaq AA. Recent advances in molecular mechanisms of cancer immunotherapy. Cancers. 2023;15(10):2721. doi: 10.3390/cancers15102721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee et al. (2022).Lee KW, Van Cutsem E, Bang YJ, Fuchs CS, Kudaba I, Garrido M, Chung HC, Lee J, Castro HR, Chao J, Wainberg ZA, Cao ZA, Aurora-Garg D, Kobie J, Cristescu R, Bhagia P, Shah S, Tabernero J, Shitara K, Wyrwicz L. Association of tumor mutational burden with efficacy of pembrolizumab ± chemotherapy as first-line therapy for gastric cancer in the phase III KEYNOTE-062 study. Clinical Cancer Research. 2022;28(16):3489–3498. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu et al. (2022).Liu J, Gao D, Li J, Hu G, Liu J, Liu D. The predictive value of systemic inflammatory factors in advanced, metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients treated with camrelizumab. OncoTargets and Therapy. 2022;15:1161–1170. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S382967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu et al. (2023).Liu Y, Hu P, Xu L, Zhang X, Li Z, Li Y, Qiu H. Current progress on predictive biomarkers for response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in gastric cancer: how to maximize the immunotherapeutic benefit? Cancers. 2023;15(8):2273. doi: 10.3390/cancers15082273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigam et al. (2023).Nigam M, Mishra AP, Deb VK, Dimri DB, Tiwari V, Bungau SG, Bungau AF, Radu AF. Evaluation of the association of chronic inflammation and cancer: insights and implications. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy. 2023;164(12):115015. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang et al. (2023).Ouyang H, Xiao B, Huang Y, Wang Z. Baseline and early changes in the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) predict survival outcomes in advanced colorectal cancer patients treated with immunotherapy. International Immunopharmacology. 2023;123(6):110703. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi et al. (2022).Qi C, Gong J, Li J, Liu D, Qin Y, Ge S, Zhang M, Peng Z, Zhou J, Cao Y, Zhang X, Lu Z, Lu M, Yuan J, Wang Z, Wang Y, Peng X, Gao H, Liu Z, Wang H, Yuan D, Xiao J, Ma H, Wang W, Li Z, Shen L. Claudin18.2-specific CAR T cells in gastrointestinal cancers: phase 1 trial interim results. Nature Medicine. 2022;28(6):1189–1198. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01800-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rha & Chung (2023).Rha SY, Chung HC. Breakthroughs in the systemic treatment of HER2-positive advanced/metastatic gastric cancer: from singlet chemotherapy to triple combination. Journal of Gastric Cancer. 2023;23:224–249. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2023.23.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargin & Dusunceli (2022).Sargin ZG, Dusunceli I. The effect of HALP score on the prognosis of gastric adenocarcinoma. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan. 2022;32(09):1154–1159. doi: 10.29271/jcpsp.2022.09.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato et al. (2021).Sato S, Oshima Y, Matsumoto Y, Seto Y, Yamashita H, Hayano K, Kano M, Ono HA, Mitsumori N, Fujisaki M, Kunisaki C, Akiyama H, Endo I, Ichikawa Y, Urakami H, Kubo H, Nagaoka S, Shimada H. The new prognostic score for unresectable or recurrent gastric cancer treated with nivolumab: a multi-institutional cohort study. Annals of Gastroenterological Surgery. 2021;5(6):794–803. doi: 10.1002/ags3.12489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlintl et al. (2022).Schlintl V, Huemer F, Rinnerthaler G, Melchardt T, Winder T, Reimann P, Riedl J, Amann A, Eisterer W, Romeder F, Piringer G, Ilhan-Mutlu A, Wöll E, Greil R, Weiss L. Checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic gastric and GEJ cancer: a multi-institutional retrospective analysis of real-world data in a Western cohort. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-09115-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shitara et al. (2020).Shitara K, Van Cutsem E, Bang YJ, Fuchs C, Wyrwicz L, Lee KW, Kudaba I, Garrido M, Chung HC, Lee J, Castro HR, Mansoor W, Braghiroli MI, Karaseva N, Caglevic C, Villanueva L, Goekkurt E, Satake H, Enzinger P, Alsina M, Benson A, Chao J, Ko AH, Wainberg ZA, Kher U, Shah S, Kang SP, Tabernero J. Efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab or pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy vs chemotherapy alone for patients with first-line, advanced gastric cancer: the KEYNOTE-062 phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncology. 2020;6(10):1571–1580. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun et al. (2024).Sun YT, Lu SX, Lai MY, Yang X, Guan WL, Yang LQ, Li YH, Wang FH, Yang DJ, Qiu MZ. Clinical outcomes and biomarker exploration of first-line PD-1 inhibitors plus chemotherapy in patients with low PD-L1-expressing of gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2024;73(8):144. doi: 10.1007/s00262-024-03721-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung et al. (2021).Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian et al. (2022).Tian BW, Yang YF, Yang CC, Yan LJ, Ding ZN, Liu H, Xue JS, Dong ZR, Chen ZQ, Hong JG, Wang DX, Han CL, Mao XC, Li T. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis of cancer immunotherapy: systemic review and meta-analysis. Immunotherapy. 2022;14(18):1481–1496. doi: 10.2217/imt-2022-0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tur-Martínez et al. (2024).Tur-Martínez J, Rodríguez-Santiago J, Osorio J, Miró M, Yarnoz C, Jofra M, Ferret G, Salvador-Roses H, Fernández-Ananín S, Clavell A, Luna A, Aldeano A, Olona C, Hermoso J, Güell-Farré M, Dal Cero M, Gimeno M, Pallarès N, Pera M. Prognostic relevance of preoperative immune, inflammatory, and nutritional biomarkers in patients undergoing gastrectomy for resectable gastric adenocarcinoma: an observational multicentre study. Cancers. 2024;16(12):2188. doi: 10.3390/cancers16122188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang et al. (2019).Wang F, Wei XL, Wang FH, Xu N, Shen L, Dai GH, Yuan XL, Chen Y, Yang SJ, Shi JH, Hu XC, Lin XY, Zhang QY, Feng JF, Ba Y, Liu YP, Li W, Shu YQ, Jiang Y, Li Q, Wang JW, Wu H, Feng H, Yao S, Xu RH. Safety, efficacy and tumor mutational burden as a biomarker of overall survival benefit in chemo-refractory gastric cancer treated with toripalimab, a PD-1 antibody in phase Ib/II clinical trial NCT02915432. Annals of Oncology. 2019;30(9):1479–1486. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang et al. (2022).Wang L, Zhu Y, Zhang B, Wang X, Mo H, Jiao Y, Xu J, Huang J. Prognostic and predictive impact of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and HLA-I genotyping in advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy. Thoracic Cancer. 2022;13(11):1631–1641. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.14431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu et al. (2022).Xu Z, Chen X, Yuan J, Wang C, An J, Ma X. Correlations of preoperative systematic immuno-inflammatory index and prognostic nutrition index with a prognosis of patients after radical gastric cancer surgery. Surgery. 2022;172(1):150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2022.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu et al. (2021).Xu J, Jiang H, Pan Y, Gu K, Cang S, Han L, Shu Y, Li J, Zhao J, Pan H, Luo S, Qin Y, Guo Q, Bai Y, Ling Y, Guo Y, Li Z, Liu Y, Wang Y, Zhou H. LBA53 Sintilimab plus chemotherapy (chemo) versus chemo as first-line treatment for advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction (G/GEJ) adenocarcinoma (ORIENT-16): first results of a randomized, double-blind, phase III study. Annals of Oncology. 2021;32:S1331. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.08.2133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan et al. (2023).Yan X, Wang J, Mao J, Wang Y, Wang X, Yang M, Qiao H. Identification of prognostic nutritional index as a reliable prognostic indicator for advanced lung cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2023;10:1213255. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1213255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon et al. (2022).Yoon HH, Jin Z, Kour O, Kankeu Fonkoua LA, Shitara K, Gibson MK, Prokop LJ, Moehler M, Kang YK, Shi Q, Ajani JA. Association of PD-L1 expression and other variables with benefit from immune checkpoint inhibition in advanced gastroesophageal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of 17 phase 3 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Oncology. 2022;8(10):1456–1465. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.3707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan et al. (2021).Yuan S, Xia Y, Shen L, Ye L, Li L, Chen L, Xie X, Lou H, Zhang J. Development of nomograms to predict therapeutic response and prognosis of non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with anti-PD-1 antibody. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2021;70(2):533–546. doi: 10.1007/s00262-020-02710-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan et al. (2022).Yuan J, Zhao X, Li Y, Yao Q, Jiang L, Feng X, Shen L, Li Y, Chen Y. The association between blood indexes and immune cell concentrations in the primary tumor microenvironment predicting survival of immunotherapy in gastric cancer. Cancers. 2022;14(15):3608. doi: 10.3390/cancers14153608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al. (2023b).Zhang Z, Li Q, Sun S, Ye J, Li Z, Cui Z, Liu Q, Zhang Y, Xiong S, Zhang S. Prognostic and immune infiltration significance of ARID1A in TCGA molecular subtypes of gastric adenocarcinoma. Cancer Medicine. 2023b;12(16):16716–16733. doi: 10.1002/cam4.6294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al. (2023a).Zhang X, Rui M, Lin C, Li Z, Wei D, Han R, Ju H, Ren G. The association between body mass index and efficacy of pembrolizumab as second-line therapy in patients with recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Medicine. 2023a;12(3):2702–2712. doi: 10.1002/cam4.5152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou et al. (2022).Zhou K, Cao J, Lin H, Liang L, Shen Z, Wang L, Peng Z, Mei J. Prognostic role of the platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) in the clinical outcomes of patients with advanced lung cancer receiving immunotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Oncology. 2022;12:962173. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.962173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Wang & Yuan (2023).Zhou X, Wang Z, Yuan K. The effect of diet and nutrition on T cell function in cancer. International Journal of Cancer. 2023;153(12):1954–1966. doi: 10.1002/ijc.34668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu et al. (2022).Zhu WJ, Zhu HH, Liu YT, Lin L, Xing PY, Hao XZ, Cong MH, Wang HY, Wang Y, Li JL, Feng Y, Hu XS. Real-world study on the efficacy and prognostic predictive biomarker of patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer treated with programmed death-1/programmed death ligand 1 inhibitors. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi Chinese Journal of Oncology. 2022;44:416–424. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112152-20210709-00504. (In Chinese) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw measurements are available in the Supplemental File.