Abstract

Background

Duck circovirus (DuCV) infections commonly induce immunosuppression and secondary infections in ducks, resulting in significant economic losses in the duck breeding industry. Currently, effective vaccines and treatments for DuCV have been lacking. Therefore, rapid, specific, and sensitive detection methods are crucial for preventing and controlling DuCV.

Methods

A lateral flow strip (LFS) detection method was developed using recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein 12a (Cas12a). The RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a-LFS targeted the DuCV replication protein (Rep) and was operated at 37 ℃ and allowed for visual interpretation without requiring sophisticated equipment.

Results

The results revealed that the reaction time of RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a-LFS is only 45 min. This method achieved a low detection limit of 2.6 gene copies. Importantly, this method demonstrated high specificity and no cross-reactivity with six other avian viruses. In a study involving 97 waterfowl samples, the Rep RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a-LFS showed 100% consistency and agreement with real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Conclusion

These findings underscored the potential of this user-friendly, rapid, sensitive, and accurate detection method for on-site DuCV detection.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12985-024-02577-7.

Keywords: Duck circovirus (DuCV), Recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA), Lateral flow strip (LFS), CRISPR/Cas12a, On-site detection

Background

Duck circovirus (DuCV), a circular single-stranded DNA virus classified within the genus Circovirus of the family Circoviridae, was first identified in Germany in 2003 [1]. Since then, infections have been reported worldwide, indicating its global distribution. DuCV is known to induce immunosuppression in ducks, making them susceptible to secondary or concurrent infections [2, 3]. The highly contagious nature of DuCV poses a significant threat to ducks across all age groups, particularly those between 3 and 4 weeks old. Ducks typically acquire DuCV through both vertical and horizontal transmission routes [4, 5], resulting in symptoms such as poor feathering, growth retardation, and below-average weight gain [6]. These features severely inhibit the development of the duck breeding industry. DuCV is genetically classified into DuCV-1 and DuCV-2 based on genomic sequencing [7], with a newly identified genotype, DuCV-3, reported recently [8]. Despite its widespread prevalence, there are currently no approved vaccines or medications available for the prevention or treatment of DuCV infection. Therefore, timely detection and implementation of control measures are critical for the spread limit of DuCV within duck populations and effective disease management.

For early disease detection and diagnosis, nucleic acid detection technologies are more effective compared to traditional pathogen antibody or antigen detection methods [9, 10]. Nucleic acid detection technologies based on the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) and their associated protein 12a (Cas12a) have been extensively adopted in clinical practice due to their high specificity in diagnosing infections [11]. In the CRISPR/Cas12a system, CRISPR RNA (crRNA) directs Cas12a to recognize complementary double-stranded DNA sequences that contain a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM). Upon recognition, Cas12a becomes activated, further resulting in the cleavage of a fluorescent reporter from the quencher and subsequent generation of a fluorescent signal [12, 13]. Combining recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) with CRISPR/Cas12a can enhance the specificity of Cas12a detection (RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a), addressing potential false positives associated with RPA, while simultaneously amplifying the cleavage signal of CRISPR [14, 15]. Moreover, RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a can be integrated with lateral flow test strips (LFS) for rapid, sensitive, accurate, and specific on-site visual detection [16].

The genome of DuCV primarily comprises two open reading frames (ORFs). ORF1 encodes the viral replication protein (Rep), while ORF2 encodes the viral capsid protein (Cap). Additionally, ORF3 is located on the complementary strand of ORF1 [17]. In this study, various combinations of RPA primers, probes, and crRNA targeting the DuCV Rep gene were tested for their efficiency. Subsequently, the optimized RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a-LFS method was evaluated for both sensitivity and specificity. Clinical samples were also analyzed using this method, demonstrating a 100% consistency between the detection results and those obtained using conventional quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). Furthermore, this method does not require expensive experimental equipment, making it potentially ideal for clinical field testing. Therefore, it might be valuable for rapid on-site detection of DuCV, aiding in the diagnosis and prevention of its spread.

Materials and methods

Viruses, reagents and instruments

Muscovy duck parvovirus (MDPV), duck adenovirus type 3 (DAdV-3), adenovirus type 4 (AdV-4), duck plague virus (DPV), duck hepatitis virus (DHV), and duck tembusu virus (DTMUV) were retrieved from clinical samples within Fujian Province and are being conserved by the Institute of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine of the Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

RNA and DNA extraction was performed using the Animal Total RNA/DNA Isolation Kit from TianLong (Suzhou, China). The LwCas12a protein, EcoRI, and XbaI endonucleases were purchased from New England Biolabs (MA, United States). The RPA kit and LFS were obtained from EZassay Ltd. (Shenzhen, China). A constant temperature metal bath purchased from Gingko Biotech (Beijing, China) was set at 37 ℃ for the experiments. Gel imaging was conducted using equipment from Gene Company Limited (MA, United States). DNA and RNA concentrations were measured with the Nanodrop ND-2000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, DE), and fluorescence intensity was measured using the Tecan Infinite M200 plate reader (Männedorf, Sweden).

Design and screening for primers and crRNA of RPA

We utilized the RPA Design online tool (https://www.ezassay.com/primer) to design four pairs of primers targeting the DuCV Rep gene (strain FJ1815, GenBank No. MN052853.1). The designed primers were selected based on the size the amplified fragment ranging from 120 bp to 250 bp and primer lengths ranging from 25 to 35 bp. For Cas12a targeting, crRNAs were designed following the 3’ end of a PAM sequence (5’-TTTV-3’). CrRNA sequence (5’-3’) consisted of a T7 promoter (UAAUACGACUCACUAUA), Cas12a scaffold sequence (UAAUUUCUACUAAGUGUAGAU), and a target sequence of 20–23 bp located after the PAM sequence. We employed the CrRNA Design online tool (https://www.ezassay.com/rna) to design crRNAs and choose the optimal one according to prediction scores. Primers and crRNAs were synthesized by EZassay Ltd. (Shenzhen, China). Detailed sequence information used in this study is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this experiment

| name | Sequence (5’-3’) | Position | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DuCV-Rep-RPA-F1 | TACCTGAGAGTTGGTGAACCAGGCGGTAAGG | 292–322 | ||

| DuCV-Rep-RPA-R1 | TTGCGTTTCAACGATCAGGTGACGAAGACGT | 435–465 | ||

| DuCV-Rep-RPA-R2 | GACCAATCAAGACGATGACTTCTGTCTTCCA | 472–502 | ||

| DuCV-Rep-RPA-R3 | GAAATTCAAACGCATAACGGCTCTTTCCGGT | 511–541 | ||

| DuCV-Rep-RPA-F2 | CGTCTTCGTCACCTGATCGTTGAAACGCAAC | 436–466 | ||

| DuCV-Rep-RPA-R4 | GTGATGCGAAGCAGGTCGTCGTAAGGTACCC | 632–662 | ||

| DuCV-Rep-crRNA |

UAAUUUCUACUAAGUGUAGAUGGCGUGGC CUCGAACGUCUUCG |

469–490 |

RPA reactions

The RPA reaction was conducted using the RPA Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the reactions were carried out in a total volume of 20 µL. It included 10.0 µL of reaction buffer, 6.0 µL of RNase/DNase-free water (ddH2O), and 0.5 µL each of upstream and downstream primers (20 µM/L). Subsequently, 1 µL of the extracted DNA and 2 µL of RPA enzymes were sequentially added and mixed gently by pipetting up and down. The RPA reaction mixture was then incubated at 37 °C in a metal bath for 20 min.

Cas12a detection reactions

The reactions were carried out using 5 µL of RPA products, 1 µL of LwCas12a protein, 2 µL of cleavage buffer, 1 µL of crRNA, 0.6 µL of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) reporter (4 µM), and ddH2O to make a total volume of 20 µL. The reactions were incubated in a metal bath for 25 min. The BHQ-labeled ssDNA probe (FAM-TTATT-BHQ) and the biotin-labeled ssDNA probe (FAM-TTATT-Biotin) were synthesized and purified by EZassay Ltd. (Shenzhen, China). Cas12a DNA endonuclease activity was assessed using blue light with a wavelength of 450 nm, as well as fluorescence signals with excitation and emission wavelengths of 492 nm and 521 nm, respectively.

Lateral flow detection

After the amplification and Cas12a detection reactions were completed, 2 µL of the reaction product was mixed with 78 µL of dilution buffer. The test results were observed two minutes after adding a lateral flow test strip to the reaction tube. DuCV DNA was detected using the elimination method. A single band appearing on the control line (C) indicated a positive result; while strips on both the control line (C) and the test line (T) indicated a negative result.

Optimization of CRISPR/Cas12a detection reactions

To optimize the concentrations of Cas12a and crRNA in the CRISPR/Cas12a system, different concentrations of Cas12a (ranging from 25 to 200 nmol/L) and crRNA (ranging from 25 to 100 nmol/L) were added to the CRISPR/Cas12a system, and the reaction products were detected by reading the fuorescence signal to determine the optimal concentration.

Sensitivity and specificity of RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a detection reactions

To investigate the sensitivity of the RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a reaction, 10-fold serial dilutions of the pcDNA3.1-DuCV-Rep-Flag plasmid standard were used as templates for the RPA reaction, whereas ddH2O was used as a negative control. To confirm the specificity, nucleic acids from MDPV, DAdV-3, AdV-4, DPV, DHV and DTMUV were used as templates for specific detection by above-mentioned method.

Clinical samples detection

For this study, a total of 97 samples were collected from Muscovy ducks in Fujian Province that were suspected to be infected with DuCV and showed developmental retardation and loss of feathers. The reaction results were read directly by LFS.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Statistical significance was determined using two-tailed t-tests. Results were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from three independent experiments, with P values less than 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Mechanism of the elimination method for strip detection

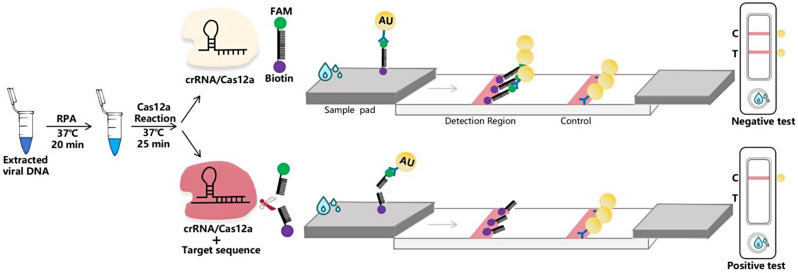

After the entire reaction was completed, the CRISPR/Cas12a solution was added to the sample pad of the test strip. The principle of the elimination method for strip detection of DuCV DNA is illustrated in Fig. 1. Gold particles linked with fluorescein amidite (FAM) antibody bind to the single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) probe on the test strip, creating a detection probe labeled as 5’-gold-Ab-FAM-ssDNA-biotin-3’. Streptavidin on the control (C) line captures the biotin-labeled probes, forming a visible gold line. If the sample contains DuCV genes, the FAM gold particles and biotin would be cleaved from the ssDNA probe due to the Cas12a-mediated cleavage of the reporter RNA. Consequently, the FAM gold particles cannot remain on the test line, and no bands are detected (indicating a positive result). In the absence of DuCV genes, the FAM gold particles and biotin-labeled probes remain intact, forming bands on both the C and T lines (indicating a negative result). If no bands appear on the C line, the test strip would be considered invalid.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the elimination method for strip detection. The ssDNA probe labeled with 5’-gold-Ab-FAM and 3’-biotin was used for LFS detection, with the top half representing the inactivated state and the bottom half representing the activated state

RPA primer screening

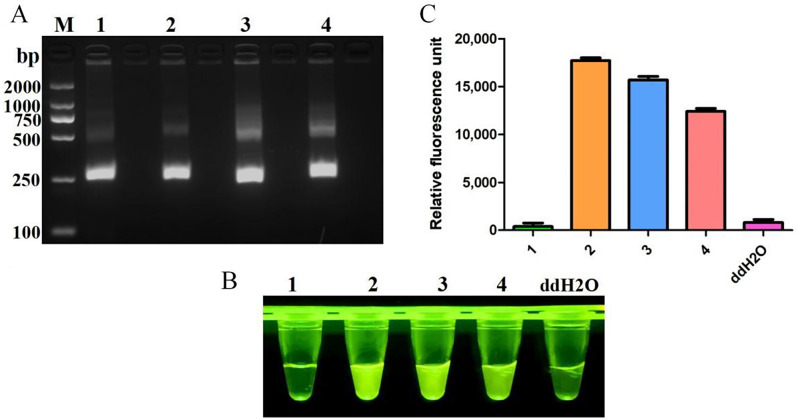

Testing the sequences of oligonucleotides is crucial for RPA, especially in evaluating the efficacy of primers. Four primer pairs targeting the Rep gene were initially tested, and their amplification products were separated using agarose gel electrophoresis. Figure 2A demonstrates successful amplification of a DNA fragment of the expected size (250 bp) from all primer sets. Subsequent Cas12a fluorescence detection results (Fig. 2B and C) indicated that primer set #2 exhibited the highest fluorescence brightness and fluorescence values among the tested sets. Based on these findings, primer set #2 was selected for further experiments.

Fig. 2.

Screening of RPA primers. (A) RPA products verified by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. M: DL2000 DNA marker; 1: F1R1; 2: F1R2; 3: F1R3; 4: F2R4. Negative control using water as template was included in each reaction. CRISPR/Cas12a fluorescence detection were performed using four primers set. Fluorescence intensity (B) and fluorescence values (C) were shown for CRISPR/Cas12a detection using four primer sets

Optimization of Cas12a and crRNA concentrations

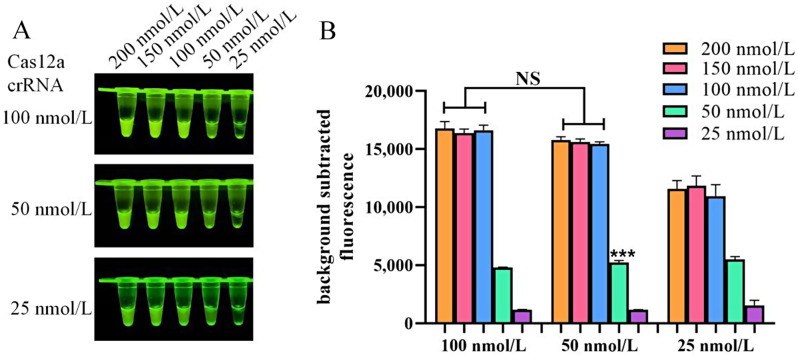

To optimize the concentrations of Cas12a and crRNA in the CRISPR/Cas12a system, various concentrations of Cas12a (ranging from 25 to 200 nmol/L) for and crRNA (ranging from 25 to100 nmol/L) were tested in each reaction. Figure 3A shows that the group with 100 nmol/L Cas12a has higher fluorescence intensity compared to the 50 nmol/L group. Additionally, the 50 nmol/L crRNA group demonstrated stronger fluorescence intensity than the 25 nmol/L crRNA group under these conditions. In terms of fluorescence values (Fig. 3B), no significant difference was observed with increasing concentrations of Cas12a and crRNA. Based on these results, a Cas12a concentration of 100 nmol/L and a crRNA concentration of 50 nmol/L were selected for use in subsequent experiments.

Fig. 3.

Optimization of the RPA and CRISPR/Cas12a system. (A) Fluorescence intensity based on CRISPR/Cas12a reaction mediated by different concentrations of Cas12a and crRNA. (B) Measurement of fluorescence values using a fluorescence microplate reader

Sensitivity of RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a method

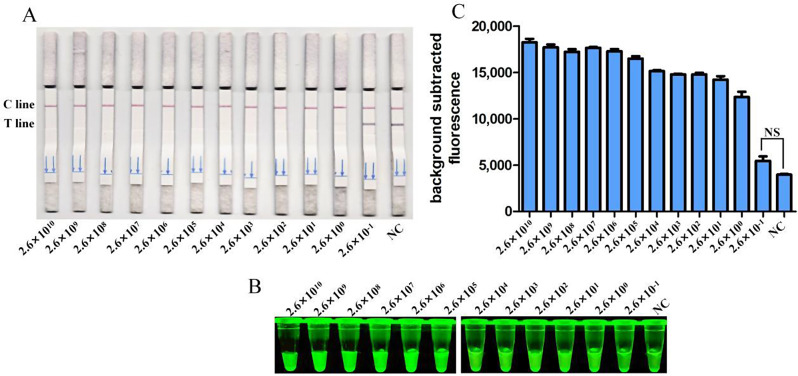

The analytical sensitivity of the CRISPR/Cas12a system was evaluated using the plasmid pcDNA3.1-DuCV-Rep-Flag constructed in our laboratory as templates. The system successfully detected concentrations ranging from 2.6 × 1010 copies/µL to 2.6 × 10− 1 copies/µL at ten-fold serial dilutions. The detection limit of the CRISPR/Cas12a method was confirmed to be 2.6 × 100 copies/µL, as indicated by the absence of the test line on the test strip (Fig. 4A), increased fluorescence brightness (Fig. 4B), and higher fluorescence values (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Sensitivity analysis. Sensitivity of CRISPR/Cas12a reaction for detecting the Rep gene with gradient concentrations from 2 × 1010 copies/µL to 2 × 10− 1 copies/µL. NC indicates negative control. Sensitivity of RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a detection (A) was assessed and verified by blue light detection (B) and fluorescence detection (C)

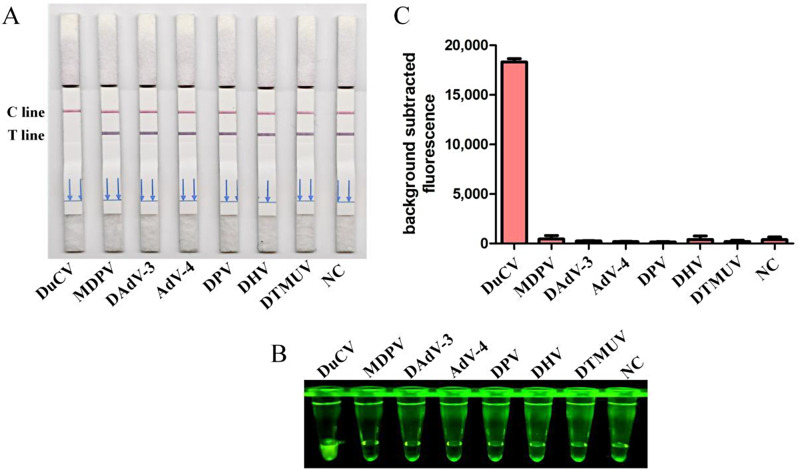

Specificity of RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a detection method

To validate the specificity of the CRISPR/Cas12a detection method, nucleic acid samples from six duck viruses other than DuCV were tested, including MDPV, DAdV-3, AdV-4, DPV, DHV and DTMUV. The results obtained from the CRISPR/Cas12a reaction using LFSs (Fig. 5A), blue light detection (Fig. 5B), and fluorescence detection (Fig. 5C). The results consistently showed that only DuCV produced a positive signal, confirming the reliability of the method.

Fig. 5.

Specificity analysis. DNA of DuCV, MDPV, DAdV-3, AdV-4, DPV, DHV, and DTMUV were used as templates for RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a reaction. The specificity of detection (A) was assessed and verified by blue light detection (B) as well as fluorescence detection (C)

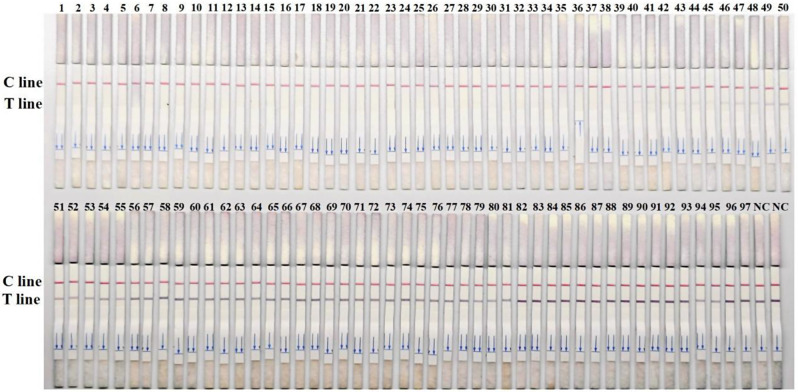

RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a-LFS detection of clinical samples

To evaluate the performance of the RPA-CRISPR assay for the detection of DuCV in clinical samples, 97 duck origin samples were analyzed. The results indicated that among the 97 samples tested, 45 were strongly positive (No. 1–45), 5 were weakly positive (No. 46–50), and 47 were negative (No. 51–97) (Fig. 6). The sequencing results revealed the presence of both DuCV-1 and DuCV-2 in the 50 positive samples, which demonstrates that the method established in this research is capable of detecting these two genotypes of DuCV simultaneously. In order to verify the reliability of the test strip for detecting DuCV, the qPCR method [18] developed by our team was used for verification detection. The results showed that RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a-LFS detection were completely consistent with those obtained from qPCR detection (Table 2). These findings confirmed the reliability of the RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a-LFS method for detecting DuCV in clinical samples.

Fig. 6.

RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a-LFS detection of clinical samples. (A) Results of RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a-LFS detection of 97 clinical samples, with 45 strongly positive, 5 weakly positive, and 47 negative outcomes. NC indicates negative control

Table 2.

The performance of RPA-CRISPR compared with qPCR

| qPCR | CR | ||||

| Positive | Negative | Total | |||

|

RPA-CRISPR/ Cas12a-LFS |

Positive | 50 | 0 | 50 | 100.00% |

| Negative | 0 | 47 | 47 | ||

| Total | 50 | 47 | 97 | ||

Discussion

The control and management of DuCV heavily rely on early detection in infected ducks due to the absence of effective vaccines and treatments. Current detection methods, such as PCR, qPCR, and loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) [19], have been commonly used for the detection of DuCV. However, PCR and qPCR methods are labor-intensive, require expensive equipment, and often need specialized personnel for result interpretation. LAMP assays have gained significant interest for their improved sensitivity for DuCV detection but face challenges such as complex primer design, limited reaction temperature range, and potential false-positive results [20, 21]. Therefore, there is a pressing need for the development of a rapid and straightforward test to identify DuCV infections.

In recent years, RPA has emerged as a novel isothermal nucleic acid amplification technique, and its key components were consisted by recombinase, DNA polymerase, and ssDNA binding protein. RPA offers the advantage of increased tolerance to PCR inhibitors, making it a preferred platform for amplification. Moreover, the rapid and straightforward nature of the RPA assay accelerates the reporting process. The CRISPR-Cas-based assay is a highly specific gene-editing technique widely used for diagnosing infections. It can be detected through fluorescence readers, LFSs, or lateral flow-based systems [14, 15]. In the fields of waterfowl and poultry, the CRISPR-Cas-based system has only been reported to be used for detecting avian infuenza virus (AIV), duck hepatitis A virus 3 (DHAV-3) and novel duck reovirus (NDRV) [22, 23]. As far as we know, there has been no report yet on the application of this system to detect DuCV up to now.

In this study, the highly conserved DuCV structural protein Rep gene was chosen as the detection target for CRISPR/Cas12a. Multiple PAM sequences were identified within the conserved region of the Rep gene. A crRNA designed based on these PAM sequences effectively mediated specific and efficient Cas12a reactions. We also optimized various parameters of the Cas12a reaction, including primer and Cas12a/crRNA ratios, which enabled successful visualization under blue light and on a LFS. The detection sensitivity of our RPA-Cas12a system was capable of detecting as few as two copies. Importantly, the entire process, from nucleic acid extraction, RPA reaction, CRISPR/Cas12a reaction, to obtaining final LFS results, could be completed within 1 h. Furthermore, results can be visually assessed with the naked eye, eliminating the requirement for expensive equipment and professional technicians.

In terms of detection specificity, six types of duck DNA or RNA viruses were included for specificity assessments. The RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a method showed no cross-reactivity with these other duck viruses, underscoring its high specificity and significant clinical detection implications. We performed three independent replicate experiments and got comparable results each time, showing that the method is stability (Figs. 4C and 5C). To validate the reliability of this approach, 97 clinical samples underwent testing using both RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a-LFS and conventional qPCR methods. The results revealed a 100% concordance rate between the two techniques.

In the future, perhaps with the increase in the production of isothermal detection reagents and the subsequent decrease in detection costs, the detection kits developed based on this method will find more extensive practical applications.

Conclusion

In summary, we developed an RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a-LFS method for the rapid and precise detection of DuCV. This approach presents a good potential for the rapid on-site detection of DuCV in clinical specimens and holds promise for early monitoring, prevention, and control of DuCV infection.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences and Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University.

Abbreviations

- DuCV

Duck circovirus

- LFS

Lateral flow strip

- RPA

Recombinase polymerase amplification

- CRISPR/Cas12a

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats and associated protein 12a

- Rep

Replication protein

- crRNA

CRISPR RNA

- PAM

Protospacer adjacent motif

- APX

Ascorbate peroxidase

- qPCR

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- ssDNA

Single-stranded DNA

- MDPV

Muscovy duck parvovirus

- DAdV-3

Duck adenovirus type 3

- AdV-4

Adenovirus type 4

- DPV

Duck plague virus

- DHV

Duck hepatitis virus

- DTMUV

Duck tembusu virus

Author contributions

QZL and WC: Writing-original draft, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Investigation. TZ and YH: Writing-review & editing, Funding acquisition, Project administration. RCL, QLF, GHF, LFC: Investigation, Formal analysis. HMC, NSJ: Visualization, Investigation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Waterfowl Industry Technology System of Modern Agriculture for China (CARS-42), the Freedom Explore Program of Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences (ZYTS202423), the Natural Science Foundation Project of Fujian Province(2023J01363).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The clinical samples collection was approved by Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

Consent for publication

All authors consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Qi-zhang Liang and Wei Chen contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors.

Contributor Information

Ting Zhu, Email: shenlansezhuzi@126.com.

Yu Huang, Email: huangyu_815@163.com.

References

- 1.Hattermann K, Schmitt C, et al. Cloning and sequencing of duck circovirus (DuCV). Arch Virol. 2003;148(12):2471–80. 10.1007/s00705-003-0181-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang X, Li L, Shang H, et al. Effects of duck circovirus on immune function and secondary infection of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Poult Sci. 2022;101(5):101799. 10.1016/j.psj.2022.101799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen M, Gao P, Wang C, et al. Pathogenicity of duck circovirus and fowl adenovirus serotype 4 co-infection in Cherry Valley ducks. Vet Microbiol. 2023;279:109662. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2023.109662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Z, Wang X, et al. Evidence of possible vertical transmission of duck circovirus. Vet Microbiol. 2014;174(1–2):229–32. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Zhang D, Bai CX, et al. Molecular characteristics of a novel duck circovirus subtype 1d emerging in Anhui, China. Virus Res. 2021;295:198216. 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soike D, Albrecht K, Hattermann K, Schmitt C, Mankertz A. Novel circovirus in mulard ducks with developmental and feathering disorders. Vet Rec. 2004;154(25):792–3. 10.1136/vr.154.25.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Z, Jia R, et al. Identification, genotyping, and molecular evolution analysis of duck circovirus. Gene. 2013;529(2):288–95. 10.1016/j.gene.2013.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liao JY, Xiong WJ, Tang H, Xiao CT. Identification and characterization of a novel circovirus species in domestic laying ducks designated as duck circovirus 3 (DuCV3) from Hunan province, China. Vet Microbiol. 2022;275:109598. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2022.109598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mo X, Wang X, Zhu Z et al. Quality Management for Point-Of-Care Testing of Pathogen Nucleic Acids: Chinese Expert Consensus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:755508. Published 2021 Oct 13. 10.3389/fcimb.2021.755508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Sciuto EL, Leonardi AA, Calabrese G, et al. Nucleic acids Analytical methods for viral infection diagnosis: state-of-the-art and future perspectives. Biomolecules. 2021;11(11):1585. 10.3390/biom11111585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y, Li S, et al. CRISPR/Cas systems towards Next-Generation Biosensing. Trends Biotechnol. 2019;37(7):730–43. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen JS, Ma E, Harrington LB, et al. CRISPR-Cas12a target binding unleashes indiscriminate single-stranded DNase activity. Science. 2018;360(6387):436–9. 10.1126/science.aar6245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swarts DC, Jinek M. Mechanistic insights into the cis- and trans-acting DNase activities of Cas12a. Mol Cell. 2019. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broughton JP, Deng X, et al. CRISPR-Cas12-based detection of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38(7):870–4. 10.1038/s41587-020-0513-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu F, Zhang K, Wang Y, et al. CRISPR/Cas12a-based on-site diagnostics of Cryptosporidium parvum IId-subtype-family from human and cattle fecal samples. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14(1):208. 10.1186/s13071-021-04709-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miao F, Zhang J, Li N, et al. Rapid and sensitive recombinase polymerase amplification combined with lateral Flow Strip for detecting African swine fever virus. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1004. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01004. Published 2019 May 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiang QW, Wang X, et al. ORF3 of duck circovirus: a novel protein with apoptotic activity. Vet Microbiol. 2012;159(1–2):251–6. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wan C, Huang Y, Cheng L, et al. The development of a rapid SYBR Green I-based quantitative PCR for detection of duck circovirus. Virol J. 2011;8:465. 10.1186/1743-422X-8-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li ZG, Wang X, Zhang RH, Chen JH, Xia LL, Lin SL, Xie ZJ, Jiang SJ. Establishment and application of double PCR method for detection of two genotypes of duck circovirus. Chin J Vet Med. 2015;35:1060–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao GY, Xie ZX, Xie LJ, Pang YS, Deng XW, Liu JB, Fan Q. Establishment of LAMP visual detection method for duck circovirus. Chin J Anim Quarant. 2012;29:24–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie L, Xie Z, et al. A loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for the visual detection of duck circovirus. Virol J. 2014;11:76. 10.1186/1743-422X-11-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou X, Wang S, Ma Y, et al. Rapid detection of avian influenza virus based on CRISPR-Cas12a. Virol J. 2023;20(1):261. 10.1186/s12985-023-02232-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Q, Yu G, Ding X, et al. A rapid simultaneous detection of duck hepatitis a virus 3 and novel duck reovirus based on RPA CRISPR Cas12a/Cas13a. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;274(1):133246. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.133246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.