Abstract

Background

The treatment of craniopharyngiomas (CPs) poses challenges due to their proximity to critical neural structures, the risk of serious complications, and the impairment of quality of life after treatment. However, long-term prognostic data are still scarce. Therefore, the purpose of this retrospective study is to evaluate the long-term outcomes of patients with CPs after treatment.

Material and method

Our center retrospectively collected data on 83 children and adolescents who underwent craniopharyngioma surgery between 2001 and 2020. The medical records and radiological examination results of the patient were reviewed.

Results

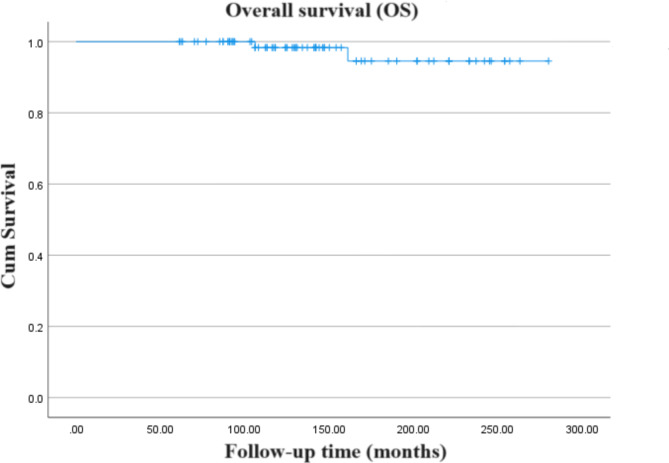

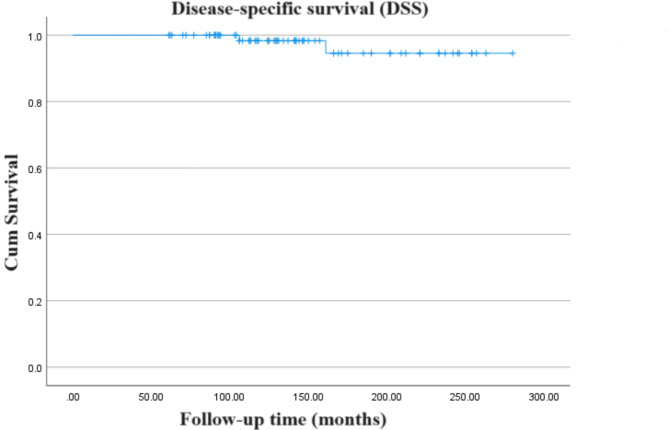

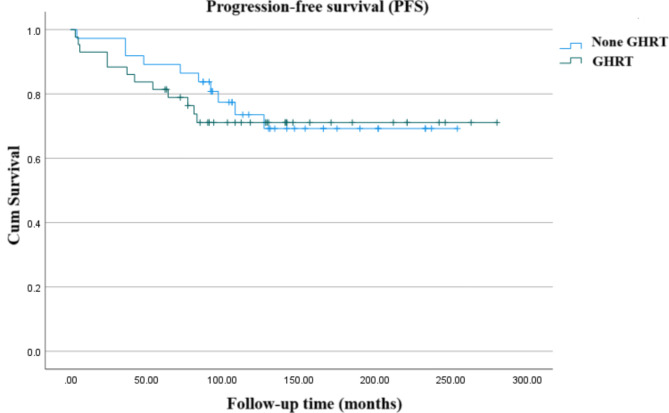

Outcomes were analysed for 80/83 patients who completed follow-up: 50 males (62.5%) and 30 females (37.5%), the median age at the time of diagnosis 8.4 (5.3–12.2) years. The median follow-up time was 136 (61–280) months. The 5-, 10- and 15-year overall survival (OS) rates were 100%, 98.3%, and 94.6%, respectively. Accordingly, the disease-specific survival (DSS) rates were 100%, 98.3% and 94.6%, respectively. Overall progression-free survival (PFS) rates after 5, 10 and 15 years of follow-up in the entire group were 85.4%, 72.2% and 70.1%, respectively. Multivariate analysis found that surgical resection grade was only associated with PFS outcomes [ HR = 0.031 (95% CI: 0.006, 0.163), P < 0.001], without improving OS or DSS. After undergoing recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) replacement therapy, the total cholesterol (TC) level decreased by 0.90 mmol/L compared to baseline (P = 0.002), and the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level decreased by 0.73 mmol/L compared to baseline (P = 0.010). For liver function, compared with baseline data, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) showed a downward trend, but did not reach a statistically significant level (P > 0.05).

Conclusion

Surgical treatment of CPs provides good long-time OS and DSS, even though combined with radiotherapy in only selected cases. Gross total resection (GTR) is individual positive prognostic factor. rhGH replacement could improve CPs lipid profile.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-024-13352-w.

Keywords: Craniopharyngiomas, Surgical resection, Clinical outcomes, Morbidity, Lipid profile

Introduction

Craniopharyngiomas (CPs) constitute approximately 1–3% of all brain tumors and 5–10% of pediatric brain tumors [1–3]. These tumors display a bimodal distribution in incidence, with peaks from ages 5 to 15 and 45 to 60 [4].

Histologically, CPs are benign neoplasms originating from embryonic remnants of Rathke’s pouch or the pituitary epithelium. They predominantly manifest in the suprasellar region, encompassing more than 80% of occurrences [5], and exhibit both solid and cystic structures. Two histological subtypes of CPs - adamantinomatous and papillary - are recognized, each characterized by distinct molecular-genetic traits [6]. While these subtypes typically do not impact clinical outcomes, adamantinomatous CPs, which are more frequent in children, are associated with an increased risk of recurrence [7]. In contrast, papillary CPs tend to occur more commonly in adults [8].

The optimal management of CPs remains a topic of debate. A conservative surgical approach focusing on preserving critical neural structures is a key strategy, as is aggressive surgical resection to achieve complete gross total resection (GTR) in the beginning. Postoperative radiation therapy (RT) may be necessary for residual tumors following subtotal resection (STR) [9]. The morbidity and mortality associated with neurosurgery procedures have been reduced due to recent advancements in microsurgical and endoscopic technologies, allowing GTR to be performed in more instances [10, 11]. Simultaneously, advancements in RT have significantly increased the accuracy of radiation administration to the tumor, reducing the potential harm to nearby neural structures [12].

The long-term prognosis of CPs after treatment is determined by both tumor growth control and treatment-related incidence rates. From large series reports, the 10-year overall survival rate (OS) is as high as 80–93% [13–17]. Although CPs patients usually have a high OS rate, even in patients without tumor recurrence, late mortality rate may occur, which may be related to complications and late effects of treatment [18]. Poor prognosis of CPs may be related to the tumor’s location near the suprasellar or hypothalamic regions [4]. Tumor compression, surgery and radiotherapy may impact hypothalamic-pituitary function and long-term quality of life [19, 20]. Children treated for CPs may experience developmental challenges, especially evident in long-term survivors treated during childhood [21]. Nevertheless, there is a lack of long-term follow-up data, and the difficulty in obtaining extensive data from large patient cohorts is compounded by the infrequency of CPs. Moreover, there are limited reports concerning the long-term endocrine outcomes following CP surgery.

This study aims to evaluate the findings and long-term effects of CP treatments at Peking Union Medical College Hospital, in comparison to similar studies published in the literature.

Materials and methods

The study involving human participants has been reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (K2917), and is in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. After explaining the purpose of the study, written informed consent was obtained from each study participant (Minor participants had their guardians sign the informed consent form). At the same time, the consent of the teenage participants and their legal guardians was also obtained.

A multidisciplinary team comprising neurosurgeons, neuroradiologist, radiation oncologists, endocrinologists, pediatric oncologists, and psychologists collaborates to make multidisciplinary decisions tailored for each patient with CPs, developing appropriate risk-adapted and hypothalamus-preserving treatment strategies.

Patient cohort

Follow-up data from January 1, 2001 to January 1, 2020 were retrospectively gathered for children and adolescents under 20 years diagnosed with CPs at our institution. We reviewed patient records to gather demographic, clinical, radiographic, and treatment information. We also analyzed patient outcomes according to disease status. The results were evaluated at the last follow-up on June 1, 2024.

Diagnosis

The diagnostic protocols for all patients involved the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), along with computed tomography (CT) to identify the characteristic calcifications associated with CPs. The examined region for MRI and CT included the entire brain (including the skull). In noncontrasted MRI images of adamantinomatous CP patients, solid tumor components and cyst walls show a variety of T1-weighted signals. The signals in T2-weighted images are usually hyper- and hypointensive. Due to this strong variability of MRI signals, an inhomogeneous distribution of calcifications can usually be assumed. To identify the presence of these diagnostically relevant calcifications in adamantinomatous CP patients, the use of a susceptibility weighted or T2*-weighted imaging would be advisable. Thus, imaging features for adamantinomatous CP patients in MRI and CT yield the following “90% rule”: ~90% are predominantly cystic, ~ 90% have prominent calcifications, and ~ 90% take up contrast media in cyst walls [22, 23]. Unfortunately, the presence of air in the paranasal sinus makes a meaningful diagnosis difficult. This is also the reason why CT should be performed in CP for detection of calcifications despite known disadvantages of X-rays [22, 23]. All patients underwent contrast-enhanced CT scans prior to surgery. Initially, CT scans were performed in the axial plane both before and after contrast enhancement, followed by post-contrast coronal CT scans, which can most accurately reveal intrasellar calcifications. The contrast agent enhances the solid components and the cyst wall. Rapid intravenous injection of iodinated contrast agent aids in better visualization of the tumor itself and its surrounding blood vessels. The CT images were compared with brain MRI in axial, coronal, and sagittal planes, respectively. On MRI, adamantinomatous CP may present as uni- or multilocular cyst, with small solid nodulation. We conducted comparisons based on different MRI sequences, tumor measurements were obtained from T2-weighted images and enhanced scan sequences. The maximum diameter of the tumor was defined as tumor size. A consultant neuropathologist verified the histopathological diagnosis of CPs and their classifications.

Thyroid-stimulating hormone deficiency was identified by a decrease in serum free thyroxine (FT4), coupled with normal or reduced thyrotropin levels [24]. The following conditions were needed to be considered for adrenocorticotropic hormone deficiency: morning cortisol (COR) levels below 3 µg/dL, or insulin tolerance test blood glucose levels below 40 mg/dL (2.2mmol/L), with a COR level below 18 µg/dL [25]. Central diabetes insipidus was diagnosed with severe hypotonic polyuria (urine production over 3 L/24 h and urine specific gravity < 1.005) in the presence of high or normal serum sodium (> 145 mmol/L) [26]. Growth hormone deficiency was identified by growth hormone stimulation testing unless low IGF-1 concentrations and hypopituitarism affecting three or more axes are confirmed [25].

Treatment approach

Initial treatment for all patients involved surgical resection, with consideration for drainage in cases of large cystic tumors. The degree of resection was assessed via operative documentation and immediate postoperative imaging when feasible. A multidisciplinary team decided on adjuvant treatments, typically recommending RT for significant residual disease.

Postoperatively, oral levothyroxine as thyroid hormone replacement is preferred in children with hypothyroidism. CP patients with central adrenal insufficiency generally received hydrocortisone. Moreover, some patients underwent growth hormone replacement therapy (GHRT) after a careful evaluation of risks and benefits, with consent from the patients’ guardians. Based on whether the pediatric patient experiences central diabetes insipidus post-surgery, oral desmopressin acetate tablets are administered for treatment.

Follow-up

Patients typically undergo routine check-ups at 3 months, 6 months and 1 - year post-operation. One year later, follow-up visits should be conducted at least once a year. Follow-up data is collected through telephone interviews and outpatient reviews.

All patients underwent CT and MRI examinations prior to surgery, with postoperative imaging assessments primarily relying on MRI. All patients underwent MRI examinations during the follow-up period and performed CT scan when necessary. Tumor recurrence is assessed via MRI. The follow-up of CP has become more accurate due to advances in MRI techniques, and radiological recurrence may now frequently be seen before clinical symptoms become evident and early secondary treatment planned. The radiological features of recurrent CP are similar to that of primary disease and may demonstrate a mass causing optic chiasm compression or hydrocephalus. On T1-weighted MRI the solid portion of adamantinomatous CP is isointense to hyperintense and heterogeneously enhancing, while the cystic areas are hyperintense with an enhancing ring on gadolinium administration. Papillary CP have a more uniform MRI appearance, being hypointense on T1-weighted MRI with contrast enhancement of the cyst wall, and hyperintense on T2 weighted imaging [27].

Endocrine indicators, including prolactin, luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, 24-hour adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and cortisol, growth hormone, and thyroid related hormones, were routinely tested in the pre- and postoperative periods. ACTH examination performed from plasma via blood test, while, other endocrine examinations performed from serum via blood test. During the follow-up period, the physical examination primarily involves documenting changes in the patient’s height, weight, and body mass index (BMI), along with assessments of visual acuity (VA) and visual field. Legal blindness was defined as best corrected VA < 20/200, impaired VA > 20/200 but ≤ 20/40 and good VA > 20/40. In addition, an assessment of the child’s growth and development was also conducted.

Statistical analysis

This research focused on several key outcomes: OS, disease-specific survival (DSS), defined as the proportion of patients not succumbing to CPs, and progression-free survival (PFS). The observation period commenced on the surgery date and concluded at the point of death from any cause or the last recorded clinical evaluation. To estimate survival distributions, we used the Kaplan-Meier method; to compare survival curves, we used the log-rank test. We used the Cox proportional hazards model to identify OS, PFS, and DSS prognostic markers. When there were differences between the predicted and actual proportions of categorical variables, we used chi-square or Fisher’s exact test to find out why. The paired t-test or the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to examine the effects of hormonal therapy before and after the intervention. At P < 0.05, significance was determined, and descriptive statistics were shown as averages with either a 95% confidence interval (CI) or standard deviation, depending on what was suitable. Statistical computations were executed via IBM SPSS® Statistics version 27 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

An examination of 83 patient records from the Peking Union Medical College Hospital database indicated that three patients were lost to follow-up, resulting in 80 subjects suitable for further examination: 50 males (62.5%) and 30 females, with a median diagnosis age of 8.4 (range 5.3–12.2) years. Initial demographic, oncological, clinical, and therapeutic details are outlined in Table 1. The median follow-up duration was 136 (range 61–280) months. The majority of tumors were suprasellar (98.8%, n = 79), with a solitary tumor located intrasellar (1.2%). Nearly all tumors were classified as adamantinomatous (97.5%). The average tumor size at its largest diameter was 32 ± 13 mm.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 50 (62.5) |

| Female | 30 (37.5) |

| Age at diagnosis, median (IQR), years | 8.4 (5.3, 12.2) |

| Pathology types | |

| Adamantinomatous | 78 (97.5) |

| Papillary | 2 (2.5) |

| Tumor size (largest diameter in mm, mean ± SD) | 32 ± 13 |

| Tumor location | |

| Suprasellar | 79 (98.8) |

| Intrasellar | 1 (1.2) |

| Surgical method | |

| Craniotomy | 76 (95.0) |

| Transsphenoidal surgery | 4 (5.0) |

| Surgical resection grade | |

| Gross total resection | 77 (96.3) |

| Subtotal resection | 3 (3.7) |

| Radiotherapy | |

| Yes | 11 (13.8) |

| No | 69 (86.2) |

| Hormone treatment | |

| Yes | 78 (97.5) |

| No | 2 (2.5) |

The principal therapeutic strategy was surgical removal, predominantly via a transcranial method in 76 (95%) cases, and through a microsurgical/endoscopic transsphenoidal technique in 4 (5%). Complete resection was accomplished in 77 (96.3%) instances, while partial resection occurred in 3 (3.7%). Eleven patients received postoperative RT. Three patients (5%) underwent adjuvant RT as a part of their primary treatment, using intensity-modulated RT (54 Gy/1.8 Gy), stereotactic radiosurgery (a prescription dose of 6.5 Gy of three fractions was applied at the 50% isodose line for 3 consecutive days) and intracavitary radiation (yttrium) in one case each. Hormone therapy post-surgery was administered to 97.5% of patients (76 patients received oral levothyroxine sodium tablets, 73 patients received oral glucocorticoids, 69 patients received oral desmopressin acetate tablets, and 27 patients received sex hormone therapy), with 37 receiving rhGH, 20 of whom had been on treatment for over a year.

Survival and outcomes

The 5-, 10-, and 15-year OS rates for the cohort were recorded at 100%, 98.3%, and 94.6% respectively (Fig. 1). Comparative studies [13–17, 21, 28–31] on a broad cohort of adult and pediatric patients indicate an OS rate of 80-93% at 10 years (Table 2). Corresponding DSS rates matched the OS rates at 100%, 98.3%, and 94.6% (Fig. 2). At the time of the latest follow-up, most (97.5%) of patients (n = 78) were still alive, only two patients died (one died of hypothalamic syndrome, and the other died of complications caused by tumor progression). Assessment of long-term survivors, using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, indicated that approximately three-quarters (74%) were symptom-free at the last follow-up.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve showing the overall survival (OS) of the entire cohort of patients included in the study

Table 2.

Survival figures from selected relevant literature

| Study | n | population | follow-up | person-year | OS | DSS | PFS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fahlbusch et al. 13, * | 148 | adult/pediatric | mean 5.4 years | 799.2 | 93 | NR | 81 |

| Karavitaki et al. 14, * | 121 | adult/pediatric | mean 8.6 years | 1040.6 | 90 | NR | 77–100 |

| Lo et al.15, * | 123 | adult/pediatric | median 8.9 years | 1094.7 | 80 | 88 | 46 |

| Mortini et al. 16, * | 112 | adult/pediatric | median 6.9 years | 772.8 | 90 | NR | 69 |

| van Effentere 17, * | 122 | adult/pediatric | mean 7.5 years | 915.0 | 85 | NR | 60 |

| Visser et al. 21 | 41 | pediatric | median 8.7 years | 356.7 | 84 | NR | NR |

| Lin et al. 28 | 31 | pediatric | median 6.5 years | 201.5 | 96 | NR | 58 |

| Sarkar et al. 29 | 37 | pediatric | median 6.6 years | 244.2 | NR | NR | 70.3 |

| Stripp et al. 30, * | 75 | adult/pediatric | median 7.6 years | 570.0 | 85 | NR | 48 |

| Liu et al. 31 | 28 | pediatric | median 6.1 years | 170.8 | 92 | NR | 37.3 |

| Our study | 80 | pediatric | median 11.3 years | 904.0 | 98 | 98 | 72 |

* The study included both adults and pediatrics, and it was not possible to calculate the person-year results for pediatrics separately

NR: Not report; OS: Overall survival; PFS: Progression-free survival; DSS: Disease-specific survival

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve showing the disease-specific survival (DSS) of the entire cohort of patients included in the study

Recurrences

A subgroup of twenty-two patients (27.5%) exhibited tumor recurrence. The PFS rates at intervals of 5, 10, and 15 years stood at 85.4%, 72.2%, and 70.1%, respectively (Fig. 3). Of those experiencing recurrence, eight patients underwent radiotherapy after recurrence (5 patients received external beam radiotherapy with total dose 52.2–54 Gy, 2 patients underwent stereotactic radiosurgery with marginal dose of 10.7 Gy, and one patient received intracavitary radiation with meticulously calculated radiation dosage 300 Gy at the cyst walls), while nineteen patients all underwent surgical treatment (five patients underwent three surgeries, nine patients underwent two surgeries, four patients underwent a single surgery, and one patient underwent four stereotactic aspiration and drainage procedures). The characteristics and treatments of these patients were summarized in Supplementary Table S1.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier curve showing the progression-free survival (PFS) of the entire cohort of patients included in the study

Prognostic factors

Univariate analysis demonstrated that the grade of surgical resection was significantly correlated with clinical outcomes, with OS, DSS, and PFS significantly better in patients who underwent GTR (P < 0.001). No significant associations were found between survival and variables such as age, sex, tumor location, size, hormone treatment, surgical method, or pathology types (P > 0.05). RT showed a tendency to improve PFS, although this was not statistically significant (P = 0.073). Multivariate analysis confirmed that the grade of surgical resection was significantly associated only with PFS outcomes [HR = 0.031 (95% CI: 0.006, 0.163), P < 0.001], but not with OS or DSS. Furthermore, in multivariate terms, RT did not significantly improve survival outcomes (P > 0.05). Additional analysis revealed that the use of rhGH replacement did not impact PFS (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Kaplan-Meier curve showing the progression-free survival (PFS) stratified by the usage of growth hormone replacement therapy (GHRT)

Long-term visual morbidities

Prior to treatment, 13 patients experienced decreased visual acuity, 2 patients had impaired visual fields, and there were no cases of blindness. During the follow-up period, within the survivor group (n = 78), 21 individuals (26.9%) manifested chronic visual impairments: 18 presented with diminished visual acuity, and three exhibited loss of visual fields but retained acuity. Moreover, two patients suffered from unilateral blindness. Among the patients who had decreased visual acuity before treatment, 3 patients experienced an improvement in their vision during the follow-up period.

Long-term endocrine morbidities and pituitary dysfunction

Of all 80 patients, 95% had one or more pituitary deficiencies at follow-up. The most common pituitary hormone deficiency was that of hypothyroidism. Percentage of patients with long term replacement therapy for hypothyroidism increased from 15% (n = 12) at diagnosis to 95% (n = 76) at follow-up. Secondly, there is adrenocorticotropic hormone insufficiency, with its incidence increasing from 17.5% (n = 14) at the time of diagnosis to 91.3% (n = 73) at the end of follow-up. Prevalence of central diabetes insipidus increased from 6.3% (n = 5) at diagnosis to 86.3% (n = 69) at last follow-up.

Schooling information

Through telephone follow-ups and inquiries during outpatient revisits, a total of 39 patients responded to questions related to their education. Among them, 36 patients returned to school after a period following the end of their treatment, with 33 completing their high school education. However, the vast majority did not pass the Nationwide Unified Examination for Admissions to General Universities and Colleges in China.

Before vs. after rhGH replacement

Among 20 craniopharyngioma patients undergoing rhGH replacement, the treatment duration spanned 33 months (range 21–48 months). Lipid profiles assessed either at the initial post-treatment visit or the final session during treatment were compared to those at the last evaluation prior to initiating rhGH replacement, which was deemed the baseline. As detailed in Table 3, there was a reduction in total cholesterol (TC) by 0.90 ± 1.13 mmol/L (P = 0.002) and in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) by 0.73 ± 1.14 mmol/L (P = 0.010) compared to baseline. Changes in triglycerides (TG) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) did not reach statistical significance. Post-treatment, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) significantly increased (P = 0.004); however, the relationship between IGF-1 alterations and changes in TC or LDL-C was not statistically significant (Pearson r = 0.098, P = 0.697; Pearson r = 0.217, P = 0.387). Variations in BMI and BMI SDS before and after the rhGH replacement remained statistically non-significant. Liver enzymes, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT), exhibited a downward trend from the baseline, yet did not achieve statistical significance (P > 0.05). No notable statistical differences were detected between total bilirubin (Tbil) and direct bilirubin (Dbil) levels (P > 0.05).

Table 3.

The comparison of lipid profile before and after rhGH replacement among craniopharyngioma patients with rhGH replacement of at least 1 year (n = 20)

| At the beginning of rhGH replacement | At the end of rhGH replacement | Difference | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 10.50 ± 4.00 | 14.60 ± 3.70 | 4.20 ± 2.40 | - |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.16 ± 4.77 | 21.40 ± 4.53 | 1.25 ± 3.55 | 0.166 |

| BMI SDS | 0.80 ± 1.70 | 0.50 ± 1.60 | -0.30 ± 1.10 | 0.215 |

| IGF1 | 51 [25, 77] | 248 [58, 320] | 158 ± 202 | 0.004 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 5.10 [4.37, 5.76] | 4.10 [3.79, 4.58] | -0.90 ± 1.13 | 0.002 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.33 [0.84, 3.16] | 1.33 [0.65, 1.87] | -0.05 [-1.01, 0.20] | 0.368 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.34 ± 0.50 | 1.26 ± 0.43 | -0.08 ± 0.45 | 0.407 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.12 ± 1.00 | 2.39 ± 0.91 | -0.73 ± 1.14 | 0.010 |

| ALT (U/L) | 17.50 [12.25, 26.75] | 15.00 [13.00, 18.75] | -0.50 [-16.00, 0.75] | 0.083 |

| AST (U/L) | 28.5 [24.25, 38.00] | 26.00 [23.25, 28.75] | -5.00 [-14.00, 1.00] | 0.079 |

| Tbil (µmol/L) | 7.05 [5.85, 10.43] | 9.00 [5.40, 11.30] | 0.00 [-1.55, 3.13] | 0.469 |

| Dbil (µmol/L) | 2.30 [1.53, 3.00] | 3.05 [1.68, 3.75] | 0.30 [-1.50, 0.80] | 0.236 |

BMI: Body mass index; SDS: Standard deviation score; TC: Total cholesterol; TG: Triglyceride; HDL-C: High-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; rhGH: Recombinant human growth hormone; IGF1: Insulin-like growth factors; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; Tbil: Total bilirubin; Dbil: Direct bilirubin

Discussion

Our study presents a retrospective analysis of a large-scale, long-term follow-up of children and adolescents post-CPs surgery. The aim was to evaluate the management strategies and long-term outcomes at a single institution. According to the literature, this study represents the longest person-years follow-up of survival for children with craniopharyngioma globally. Following GTR in 96.3% of cases, and a median follow-up of 136 months, we observed a 10-year OS rate of 98.3%, a DSS of 98.3%, and a PFS of 72.2%. STR was found to be significantly associated with poorer PFS in our cohort. Additionally, our findings indicate that GHRT does not impact long-term survival, but it does improve lipid metabolism in CPs and tends to reduce liver enzyme levels.

CPs typically develop in the suprasellar region near the optic chiasm, primarily along the pituitary stalk. In some cases, they may also originate within the sella [5] or extend towards the optic system or third ventricle [32]. Adamantinomatous CPs, more prevalent in the pediatric population [6], were notably predominant (97.5%) in our patient cohort, while papillary CPs are typically seen in adults. The impact of tumor subtype on prognosis is not fully established, and earlier research suggests similar outcomes concerning resectability, radiation response, and OS [33].

Modern research often provides limited or incomplete follow-up periods, usually only showing survival rates [16, 17, 34]. However, studies with longer historical follow-ups produce results that cannot be easily compared to outcomes of patients treated with current surgical and radiotherapeutic methods. In our research, the 10-year OS rate reached 98.3%, surpassing the 75–96% rates reported in other comprehensive studies involving both adult and pediatric or solely pediatric populations [13–17, 21, 28–31] (Table 2). This elevated OS rate primarily results from the extensive application of GTR and the management strategies for patients with local recurrences, involving secondary or multiple surgeries and RT. Consequently, our data for the 10-year DSS and PFS, at 98.3% and 72.2% respectively, align favorably with earlier published Fig. [7]. An extensive median follow-up duration of 136 months enabled detailed mortality documentation related to tumor recurrence. The long-term outcomes post-CPs treatment are dependent on effective tumor growth control and management of treatment-associated complications. It is noteworthy that late mortality might increase even among patients without tumor progression, potentially linked to treatment complications, particularly in those treated during childhood [18, 21].

The main goals of surgery involve determining the histopathological diagnosis, relieving pressure on vital neural and vascular structures near the tumor, and safely extracting as much of the tumor as possible. Many experts believe that undergoing surgery early on provides the best opportunity to achieve complete tumor removal while minimizing the risk of neurological damage [13, 35]. Traditionally favored, GTR has been associated with considerable morbidity in past studies [17, 36]. Currently, surgical strategies have shifted towards a more conservative approach, such as STR, to mitigate risks of hypothalamic damage and subsequent severe neuroendocrine dysfunction [37]. Studies indicate that outcomes for tumor control and survival for patients undergoing STR followed by postoperative RT or radiosurgery are comparable or superior to those after GTR [15]. In addition, there have been numerous reports of increased occurrences of complications related to the nervous system, eyes, and hormonal system after GTR [35, 36]. Thus, GTR is advised only in cases where the tumor does not infiltrate the hypothalamus [38].

Within our cohort, GTR correlated with significantly extended PFS, primarily because a smaller segment of patients received RT following STR. With advancements in RT technology, this protocol was revised to integrate newer, more advanced RT methods. Although RT demonstrated a tendency to improve PFS outcomes, these improvements were not statistically significant. Conversely, a strategy combining STR with RT or radiosurgery on residual tumors has effectively reduced the risk of local recurrence [28, 36]. It is still unclear whether adjuvant RT effectively improves overall survival, as there have been no randomized trials directly comparing adjuvant RT with delayed RT after disease recurrence [28, 36].

Despite their histological benignity, CPs are a chronic condition, necessitating long-term management even following successful primary GTR, due to ongoing risks of recurrence and associated morbidity which may compromise quality of life [16, 18]. The risk of endocrine dysfunction, either as a direct consequence of the tumor or as a result of treatment interventions, is a major contributor to increased mortality and morbidity among CPs patients [18], particularly for those who have undergone GTR. During surgical procedures, it is often difficult to preserve the pituitary stalk, which is commonly adherent to or encased by the tumor capsule. As a result, panhypopituitarism is common among patients [39], affecting 95% of our cohort. Additionally, the occurrence of obesity and metabolic syndrome, resulting from the impact of tumors or damage to the hypothalamus due to treatment, requires thorough monitoring and strict dietary management to avoid excessive weight gain [40].

Post-surgery GHRT is critical for patients with craniopharyngioma. Previous research has demonstrated that hormone replacement significantly promotes growth and enhances metabolic processes; however, the outcomes of rhGH replacement in CPs patients present complexities. While the majority of studies highlight improvements in stature among pediatric patients, the effects on weight and BMI demonstrate considerable variability across the literature [41, 42], suggesting diverse metabolic reactions to rhGH replacement among CPs patients. Moreover, while reductions in TC and LDL-C post-rhGH replacement were significant in two studies [43, 44], another study reported these changes as nonsignificant [45]. Notably, the impact of rhGH varies between pediatric and adult patients or between those diagnosed in childhood versus adulthood [41]. Our research found that rhGH replacement had a positive effect on the lipid profiles of children and adolescents with CPs, which is consistent with the results seen in adults [43, 44].

There was a trend toward lower AST and ALT levels in CPs patients treated with rhGH, but the changes were not statistically significant. Adults with growth hormone deficiency have a far higher prevalence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) at 21% and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) at 70%, compared to 12% and 5%, respectively, in the general population [46, 47]. Patients with GH deficit with NASH or NAFLD have shown improvement in hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis after undergoing GHRT [47, 48]. This study lends credence to the idea that rhGH treatment can effectively lower the prevalence of fatty liver disease in children. Inhibiting hepatic fat synthesis [49], suppression Kupffer cell function [50], reducing hepatocyte oxidative stress [51], inducing Kupffer cell senescence [52], promoting hepatocyte proliferation, and inducing autophagy [53] are all protective functions of growth hormone in the liver. Insufficient GH in the body can lead to obesity and hepatopulmonary syndrome; however, using GHRT supplements can improve liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, which can reduce this risk [54]. Li et al. demonstrated that a lack of growth hormone in a control group exacerbated transaminase levels, emphasizing the essential role of rhGH in safeguarding the liver against fibrosis and cirrhosis [55].

Moreover, our research confirms that rhGH therapy does not elevate the risk of CPs recurrence. Losa et al. reviewed 283 adults with growth hormone deficiency (AGHD) due to nonfunctioning pituitary adenoma (NFPA) or CPs from 1995 to 2018 and found no association between rhGH replacement and an increased risk of tumor recurrence in these patients. These findings reinforce the prevailing view that rhGH treatment does not affect the recurrence rates of pituitary tumors [56]. Additionally, longitudinal studies extending over 10 years have shown that sustained GHRT does not alter PFS [57]. In a similar vein, Nguyen Quoc et al. investigated 71 patients with childhood-onset CPs undergoing rhGH treatment and observed no connection between the onset of GHRT after treatment and any rise in recurrence or tumor progression risks, indicating that GHRT could be initiated six months following the last treatment for CPs [58].

Limitations of the study

This investigation was a single-center retrospective analysis covering up to a 10-year follow-up period. Within this timeframe, significant advancements in radiological imaging, surgical procedures, perioperative care, and RT/radiosurgery were made. Consequently, our results predominantly reflect the outcomes from a period before the widespread adoption of advanced surgical methods, specifically endonasal/transsphenoidal endoscopy. However, our study also showed a gradual increase in the use of endoscopic transnasal butterfly surgeries in recent years. It is projected that the utilization of endoscopic techniques will further enhance surgical outcomes, particularly in achieving GTR more frequently and in reducing complication rates. Furthermore, with advancements in radiotherapy technology and updated treatment concepts, radiotherapy has played an increasingly significant role in the treatment of craniopharyngiomas. STR combined with RT demonstrates clear advantages in preserving pituitary function and mitigating neural damage in pediatric patients. However, the number of patients undergoing STR combined with RT in this study was relatively small, preventing the conduct of subgroup analysis with those undergoing GTR. Future analyses should incorporate data from multiple centers to assess long-term survival outcomes and the associated endocrine and metabolic changes following craniopharyngioma surgery.

Conclusion

The surgical management of CPs, occasionally enhanced with adjuvant RT, secures favorable long-term OS and DSS, despite the challenges of postoperative complications, especially endocrine dysfunction. Additionally, our research confirms that GHRT does not influence long-term survival outcomes. Long-term GHRT positively affects lipid metabolism in CPs and tends to reduce liver enzyme levels.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

All authors express their gratitude to Wei Guo from the Hebei Province Cangzhou Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine for his guidance and assistance in this article. My deepest gratitude is extended to all the physicians in the Neurosurgery Department of Peking Union Medical College.

Abbreviations

- CPs

Craniopharyngiomas

- GTR

Gross total resection

- STR

Subtotal resection

- RT

Radiotherapy

- OS

Overall survival

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- DSS

Disease-specific survival

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- CT

Computed tomography

- GHRT

Growth hormone replacement therapy

- CI

Confidence interval

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- BMI

Body mass index

- VA

Visual acuity

- SDS

Standard deviation score

- IGF1

Insulin-like growth factors

- TC

Total cholesterol

- TG

Triglyceride

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- rhGH

Recombinant human growth hormone

- Tbil

Total bilirubin

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- Dbil

Direct bilirubin

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Li-Yuan Zhang. Data curation: Han-Ze Du, Li-Yuan Zhang. Formal analysis: Li-Yuan Zhang. Project administration: Hui Pan. Methodology: Han-Ze Du, Li-Yuan Zhang. Resources: Hui Pan, Ting-Ting Lu, Rong Xu, Shuai-Hua Song, Yue Jiang. Supervision: Hui Pan. Writing – original draft: Li-Yuan Zhang, Han-Ze Du. Writing – review & editing: Hui Pan, Li-Yuan Zhang. Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Funding

This study was supported by the National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-PUMCH-A-154).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study involving human participants has been reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (K2917), and is in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. After explaining the purpose of the study, written informed consent was obtained from each study participant. At the same time, the consent of the teenage participants and their legal guardians was also obtained.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Li-Yuan Zhang and Han-Ze Du contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

References

- 1.Bunin GR, Surawicz TS, Witman PA, Preston-Martin S, Davis F, Bruner JM. The descriptive epidemiology of craniopharyngioma. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:547–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garre ML, Cama A. Craniopharyngioma: modern concepts in pathogenesis and treatment. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007;19:471–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan RB, Merchant TE, Boop FA, et al. Headaches in children with craniopharyngioma. J Child Neurol. 2013;28:1622–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Otte A, Müller HL. Childhood-onset Craniopharyngioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106:e3820–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laws ER Jr. Transsphenoidal microsurgery in the management of craniopharyngioma. J Neurosurg. 1980;52:661–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23:1231–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu J, Wu X, Yang YQ, et al. Association of histological subtype with risk of recurrence in craniopharyngioma patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg Rev. 2022;45:139–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lehrich BM, Goshtasbi K, Hsu FPK, Kuan EC. Characteristics and overall survival in pediatric versus adult craniopharyngioma: a population-based study. Childs Nerv Syst. 2021;37:1535–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piloni M, Gagliardi F, Bailo M, et al. Craniopharyngioma in pediatrics and adults. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2023;1405:299–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abiri A, Roman KM, Latif K, et al. Endoscopic versus nonendoscopic surgery for resection of craniopharyngiomas. World Neurosurg. 2022;167:e629–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madsen PJ, Buch VP, Douglas JE, et al. Endoscopic endonasal resection versus open surgery for pediatric craniopharyngioma: comparison of outcomes and complications. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2019;24:236–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mesny E, Lesueur P. Radiotherapy for rare primary brain tumors. Cancer Radiother. 2023;27:599–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fahlbusch R, Honegger J, Paulus W, Huk W, Buchfelder M. Surgical treatment of craniopharyngiomas: experience with 168 patients. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:237–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karavitaki N, Brufani C, Warner JT, et al. Craniopharyngiomas in children and adults: systematic analysis of 121 cases with long-term follow-up. Clin Endocrinol. 2005;62:397–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lo AC, Howard AF, Nichol A, et al. Long-term outcomes and complications in patients with craniopharyngioma: the British Columbia Cancer Agency experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88:1011–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mortini P, Losa M, Pozzobon G, et al. Neurosurgical treatment of craniopharyngioma in adults and children: early and long-term results in a large case series. J Neurosurg. 2011;114:1350–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Effenterre R, Boch AL. Craniopharyngioma in adults and children: a study of 122 surgical cases. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olsson DS, Andersson E, Bryngelsson IL, Nilsson AG, Johannsson G. Excess mortality and morbidity in patients with craniopharyngioma, especially in patients with childhood onset: a population-based study in Sweden. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:467–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Schaik J, Schouten-van Meeteren AYN, Vos-Kerkhof E, et al. Treatment and outcome of the Dutch Childhood Craniopharyngioma Cohort study: first results after centralization of care. Neuro Oncol. 2023;25:2250–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang LY, Guo W, Du HZ, et al. Brachytherapy in craniopharyngiomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis of long-term follow-up. BMC Cancer. 2024;24:637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Visser J, Hukin J, Sargent M, Steinbok P, Goddard K, Fryer C. Late mortality in pediatric patients with craniopharyngioma. J Neurooncol. 2010;100:105–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Müller HL, Merchant TE, Warmuth-Metz M, Martinez-Barbera JP, Puget S, Craniopharyngioma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warmuth-Metz M. Imaging and diagnosis in Pediatric Brain Tumor studies. Springer Int Publishing. 2017; 44–50.

- 24.Alexopoulou O, Beguin C, De Nayer P, Maiter D. Clinical and hormonal characteristics of central hypothyroidism at diagnosis and during follow-up in adult patients. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;150:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleseriu M, Hashim IA, Karavitaki N, et al. Hormonal replacement in hypopituitarism in adults: an endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:3888–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burke WT, Cote DJ, Penn DL, Iuliano S, McMillen K, Laws ER. Diabetes insipidus after endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery. Neurosurgery. 2020;87:949–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liubinas SV, Munshey AS, Kaye AH. Management of recurrent craniopharyngioma. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:451–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin LL, El Naqa I, Leonard JR, et al. Long-term outcome in children treated for craniopharyngioma with and without radiotherapy. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1:126–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarkar S, Chacko SR, Korula S, et al. Long-term outcomes following maximal safe resection in a contemporary series of childhood craniopharyngiomas. Acta Neurochir. 2021;163:499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stripp DC, Maity A, Janss AJ, et al. Surgery with or without radiation therapy in the management of craniopharyngiomas in children and young adults. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:714–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu AP, Tung JY, Ku DT, et al. Outcome of Chinese children with craniopharyngioma: a 20-year population-based study by the Hong Kong Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Study Group. Childs Nerv Syst. 2020;36:497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iwasaki K, Kondo A, Takahashi JB, Yamanobe K. Intraventricular craniopharyngioma: report of two cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 1992;38:294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crotty TB, Scheithauer BW, Young WF Jr, et al. Papillary craniopharyngioma: a clinicopathological study of 48 cases. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:206–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi XE, Wu B, Fan T, Zhou ZQ, Zhang YL. Craniopharyngioma: surgical experience of 309 cases in China. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008;110:151–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamada S, Fukuhara N, Yamaguchi-Okada M, et al. Therapeutic out comes of transsphenoidal surgery in pediatric patients with craniopharyngiomas: a single-center study. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2018;21:549–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mark RJ, Lutge WR, Shimizu KT, Tran LM, Selch MT, Parker RG. Craniopharyngioma: treatment in the CT and MR imaging era. Radiology. 1995;197:195–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen M, Bartels U, Branson H, Kulkarni AV, Hamilton J. Trends in treatment and outcomes of pediatric craniopharyngioma, 1975–2011. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15:767–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cossu G, Jouanneau E, Cavallo LM, et al. Surgical management of craniopharyngiomas in adult patients: a systematic review and consensus statement on behalf of the EANS skull base section. Acta Neurochir. 2020;162:1159–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yano S, Kudo M, Hide T, et al. Quality of life and clinical features of long-term survivors surgically treated for pediatric craniopharyngioma. World Neurosurg. 2016;85:153–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clark AJ, Cage TA, Aranda D, Parsa AT, Auguste KI, Gupta N. Treatment-related morbidity and the management of pediatric craniopharyngioma: a systematic review. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2012;10:293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boekhoff S, Bogusz A, Sterkenburg AS, Eveslage M, Müller HL. Long-term effects of growth hormone replacement therapy in childhood-onset craniopharyngioma: results of the German Craniopharyngioma Registry (HIT-Endo). Eur J Endocrinol. 2018;179:331–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heinks K, Boekhoff S, Hoffmann A, et al. Quality of life and growth after childhood craniopharyngioma: results of the multinational trial KRANIOPHARYNGEOM 2007. Endocrine. 2018;59:364–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yuen KC, Koltowska-Häggström M, Cook DM, et al. Clinical characteristics and effects of GH replacement therapy in adults with childhood-onset craniopharyngioma compared with those in adults with other causes of childhood-onset hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;169:511–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verhelst J, Kendall-Taylor P, Erfurth EM, et al. Baseline characteristics and response to 2 years of growth hormone (GH) replacement of hypopituitary patients with GH deficiency due to adult-onset craniopharyngioma in comparison with patients with nonfunctioning pituitary adenoma: data from KIMS (Pfizer International Metabolic database). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:4636–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Profka E, Giavoli C, Bergamaschi S, et al. Analysis of short- and long-term metabolic effects of growth hormone replacement therapy in adult patients with craniopharyngioma and non-functioning pituitary adenoma. J Endocrinol Invest. 2015;38:413–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ichikawa T, Hamasaki K, Ishikawa H, Ejima E, Eguchi K, Nakao K. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatic steatosis in patients with adult onset growth hormone deficiency. Gut. 2003;52:914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nishizawa H, Iguchi G, Murawaki A, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adult hypopituitary patients with GH deficiency and the impact of GH replacement therapy. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;167:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takahashi Y, Iida K, Takahashi K, et al. Growth hormone reverses nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in a patient with adult growth hormone deficiency. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:938–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cordoba-Chacon J, Majumdar N, List EO, et al. Growth hormone inhibits hepatic De Novo Lipogenesis in Adult mice. Diabetes. 2015;64:3093–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nishizawa H, Takahashi M, Fukuoka H, Iguchi G, Kitazawa R, Takahashi Y. GH-independent IGF-I action is essential to prevent the development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in a GH-deficient rat model. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;423:295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nishizawa H, Iguchi G, Fukuoka H, et al. IGF-I induces senescence of hepatic stellate cells and limits fibrosis in a p53-dependent manner. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lavu N, Richardson L, Radnaa E, et al. Oxidative stress-induced downregulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta in fetal membranes promotes cellular senescence†. Biol Reprod. 2019;101:1018–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fang F, Shi X, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, Liang G. Growth hormone acts on liver to stimulate autophagy, support glucose production, and preserve blood glucose in chronically starved mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:7449–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Torii N, Ichihara A, Mizuguchi Y, Seki Y, Hashimoto E, Tokushige K. Hormone-replacement therapy for Hepatopulmonary Syndrome and NASH Associated with Hypopituitarism. Intern Med. 2018;57:1741–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Li S, Wang X, Zhao Y et al. Metabolic Effects of Recombinant Human Growth Hormone Replacement Therapy on Juvenile Patients after Craniopharyngioma Resection. Int J Endocrinol. 2022; 2022:7154907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Losa M, Castellino L, Pagnano A, Rossini A, Mortini P, Lanzi R. Growth hormone therapy does not increase the risk of Craniopharyngioma and Nonfunctioning Pituitary Adenoma recurrence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:dgaa089. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Olsson DS, Buchfelder M, Wiendieck K, et al. Tumour recurrence and enlargement in patients with craniopharyngioma with and without GH replacement therapy during more than 10 years of follow-up. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;166:1061–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Nguyen Quoc A, Beccaria K, González Briceño L, et al. GH and Childhood-onset Craniopharyngioma: when to initiate GH replacement therapy? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108:1929–36. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.