Abstract

Development of an effective tuberculosis (TB) vaccine has been challenged by incomplete understanding of specific factors that provide protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) and the lack of a known correlate of protection (CoP). Using a combination of samples from a vaccine showing efficacy (DarDar [NCT00052195]) and Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG)-immunized humans and nonhuman primates (NHP), we identify a humoral CoP that translates across species and vaccine regimens. Antibodies specific to the DarDar vaccine strain (M. obuense) sonicate (MOS) correlate with protection from the efficacy endpoint of definite TB. In humans, antibodies to MOS also scale with vaccine dose, are elicited by BCG vaccination, are observed during TB disease, and demonstrate cross-reactivity with Mtb; in NHP, MOS-specific antibodies scale with dose and serve as a CoP mediated by BCG vaccination. Collectively, this study reports a novel humoral CoP and specific antigenic targets that may be relevant to achieving vaccine-mediated protection from TB.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, Vaccine, Correlates of Protection, Humoral immunity, Antibody, Efficacy trial

Tuberculosis (TB) is the leading infectious disease cause of death globally. Based on the current annual TB death rate of 2%, predicted TB mortality from 2020 to 2050 is estimated at 31.8 million deaths, corresponding to an economic loss of 17.5 trillion USD1. The Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine, introduced in 1921, is the only effective vaccine currently available. BCG, which also reduces all-cause mortality2, is an attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis, the etiological agent of TB in cattle. However, a birth dose of this vaccine has modest efficacy that wanes after 10–15 years3,4, motivating the development of booster strategies for adolescents and adults immunized at birth5.

Unfortunately, TB vaccine development has been stymied by the absence of known human correlates of protection (CoP) after vaccination with BCG or other candidate vaccines3,6. Identification and validation of CoP could meaningfully decrease the time and cost of early development assessments of candidate vaccine regimens7 and contribute to successful development and deployment of improved TB vaccines, which are crucial to global TB control8. With this goal in mind, inactivated Mycobacterium obuense (M. obuense) SRL172 vaccine, in development as a post-BCG booster, conferred protection from culture-confirmed TB in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III clinical trial (DarDar) in Tanzania [NCT00052195]9,10—a major step toward the improved prevention of tuberculosis vaccine worldwide. Evaluating this vaccine demonstrated to be safe and immunogenic in people living with HIV (PLWH) with prior BCG vaccination in phase I and phase II studies in Finland and Zambia11,12, the DarDar trial was stopped early for statistically significant vaccine efficacy of 39% for the secondary endpoint of preventing culture-confirmed TB9. SRL172 vaccine elicited cellular and humoral immune responses, but these were of low magnitude and no CoP was identified13, leaving markers and mechanisms of protection undefined. Archived samples from this trial provide an unprecedented opportunity to interrogate immune correlates of vaccine-mediated protection from TB that complement immunogenicity studies of other contemporary TB vaccine candidates.

While there is much evidence to support the mechanistic relevance of cellular immune responses to protection from TB in humans and preclinical models, these responses are considerably more complex to measure than the humoral responses prevalent among CoP known for other protective vaccines. Furthermore, there is ample evidence to support seeking humoral correlates of vaccine-mediated protection from TB. Humans diagnosed with active or latent TB exhibit differential serum antibody composition and function14–17, and serum IgG from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb)-exposed healthcare workers contains Mtb surface-specific antibodies that inhibit Mtb growth in vitro and reduce bacterial burden in mouse challenge studies18. Antibody depletion and passive immunization studies of monoclonal antibodies in mice further confirm the potential for mechanistic humoral contributions to protection from TB19–32, and BCG-vaccinated macaques raise humoral responses that are associated with prevention of TB infection33–35.

Humoral responses may be especially relevant in the context of diminished T cell counts and function, such as from co-infection with Mtb and HIV, a major global syndemic. The two pathogens potentiate one another36, with HIV infection rates rising as protection from TB afforded by BCG immunization at birth wanes. Indeed, TB disease is the most common opportunistic infection causing mortality in PLWH37, accounting for roughly 30% of world-wide AIDS-related deaths38,39. Thus, the development of a vaccine, like SRL172, that is safe and effective for PLWH is a leading global health priority40,41. To this end, while not directly translatable, pre-clinical models of i.v administration of BCG35,42–44, which has demonstrated near complete protection in nonhuman primate (NHP) models, highlight a new route by which a century-old vaccine may yet influence global health. Here, we leverage archived samples from these and other studies and apply a systems serology approach to survey for humoral CoP to aid and guide future TB vaccine development.

Results

Vaccination with SRL172 induces M. obuense sonicate (MOS)-specific antibodies

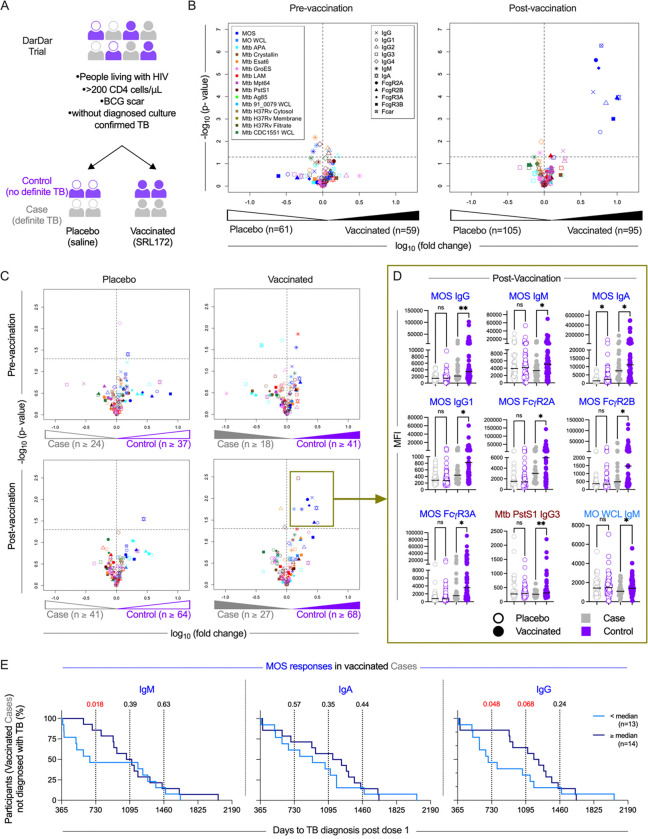

Participants in the DarDar trial included PLWH with a CD4 count of at least 200 cells/μL and a BCG scar who received either a five-dose series of 1 mg inactivated M. obuense SRL172 or borate-buffered isotonic saline intradermally (Figure 1A)9. Serum samples from trial participants, who were screened for TB routinely every three months, were selected using a case-control design and evaluated using systems serology approaches. Participants who developed definite TB (cases) following completion of the five-dose series in both vaccine and placebo arms were matched based on age, tuberculin skin test results, and prior TB status with control subjects who did not develop definite TB after vaccination (Supplemental Table 1).

Fig. 1: MOS-specific antibodies correlate with protection from disease in the DarDar trial.

A. Schematic of the DarDar vaccine trial conducted in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Participants were randomized to the vaccine (SRL172 vaccine) or placebo group (borate buffered isotonic saline) groups. B-C. Volcano plots depicting the magnitude (fold change) and statistical significance (Welch’s t-test) of differences in each measured humoral immune response feature detected in serum samples from placebo and vaccinated subjects at baseline (pre-vaccination, left) and following immunization (post-vaccination, right) (B), and between Cases and Controls in measured immune features at pre-vaccination (top) and post-vaccination (bottom) timepoints and in placebo (left) and vaccinated (right) participants (C). Dotted horizontal lines indicate unadjusted p = 0.05 as determined by Welch’s t-test. Color indicates antigen specificity, while shape indicates the antibody Fc domain characteristic for each response feature measured. D. Box plots comparing the levels of select immune features at post-vaccination timepoint amongst cases (gray) and controls (purple) in placebo (hollow circles) and vaccine (solid circles) recipients. Statistical significance was determined by Unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction (**p<0.01, *p<0.05, ns p ≥ 0.05). Bar indicates median. E. Kaplan-Meier curves depicting diagnosis of TB over time in vaccinated cases for high (≥ median, dark blue) and low (< median, light blue) MOS-specific IgM (left), IgA (center) and IgG (right) responders. Statistical significance was evaluated at years 1, 2, and 3 (vertical lines) post final vaccine dose using log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test; values <0.1 are indicated in red.

We evaluated antibody responses in blinded serum samples drawn from participants at the pre- (n=120) and post- (n=200) immunization timepoints. Antigen-specific IgA, IgM, IgG and IgG subtypes (IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, IgG4) responses were evaluated45,46. Characterization extended beyond isotypes and subclasses to include propensity to bind Fc receptors (FcγR2A, FcγR2B, FcγR3A, FcγR3B and FcαR). The panel of antigens consisted of sonicate derived from the SRL172 vaccine strain M. obuense grown on agar (MOS); whole cell lysate of vaccine strain M. obuense grown in broth (MO WCL); Mtb virulence factor early secreted antigen target 6kDa (ESAT6), alanine- and proline-rich antigenic protein (APA), lipoarabinomannan (LAM), α-crystallin, PstsS1, the major culture filtrate protein Mpt64, the heat shock protein GroES, evasion factor antigen 85 complex; WCL from Mtb strain 91_0079; Mtb strain CDC1551 WCL, cytosolic, and cell membrane fractions, as well as culture filtrates of Mtb strain H37Rv (Supplemental Table 2).

Whereas few differences in measured antibody responses between placebo- and SRL172 recipients were observed at baseline, higher MOS-specific IgG, IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, IgA and binding to FcαR, FcγR2A, FcγR2B and FcγR3B were observed in vaccinated as compared to placebo participants post-vaccination (Figure 1B, Supplemental Figure 1). Overall, this analysis demonstrated robust induction of diverse isotypes and subclasses of antibodies specific for the vaccine strain.

MOS-specific antibodies correlate with protection in the DarDar trial

To identify a CoP, we compared humoral responses over time in placebo- and vaccine-recipients in participants who did or did not develop TB disease using a case-control design. While TB disease status groups did not differ in CD4 T cell counts or HIV-1 viral load at baseline (Supplemental Figure 2), we observed elevated MOS-specific IgM, IgA, IgG, IgG1, and FcγR2A-, FcγR2B-, FcγR3A-binding antibody responses in vaccinated controls as compared to vaccinated TB disease cases in cross-sectional analysis between groups (Figure 1C, 1D). Longitudinal analyses demonstrated robust induction of these humoral responses among vaccine recipients that did not experience TB disease (Supplemental Figure 3). While Mtb PstS1-specific IgG3 responses were also elevated in controls (Figure 1C), differences in magnitude were small (Figure 1D). IgM responses to MO WCL were also elevated in vaccinated controls as compared to cases. In contrast, relatively few differences between cases and controls were noted in pre-immunization response profiles or among placebo-recipients at either timepoint. Intriguingly, however, MOS-specific IgA was elevated at both pre- and post-immunization timepoints in placebo controls as compared to cases, suggesting that it may be a marker of pre-existing immunity to TB (Figure 1C, 1D, Supplemental Figure 3).

Differential risk is associated with MOS-specific antibody response magnitude among breakthrough TB disease cases in vaccine recipients

To further evaluate the relevance of MOS-specific antibodies as CoPs, we next tested relationships between time to TB diagnosis and MOS-specific antibody response magnitude within the subset of participants who ultimately developed definite TB. Participants were classified as ‘low’ or ‘high’ responders based on the magnitude of MOS-specific IgM, IgA, or IgG responses post-vaccination. Among vaccine but not placebo recipients who were diagnosed with definite TB, those with greater IgM and IgG responses to MOS showed significantly decreased risk of disease early in the follow up period (Figure 1E, Supplemental Figure 4). These results demonstrate that MOS IgG and IgM responses are correlates of reduced risk of early disease diagnosis in breakthrough cases, and a quantitative relationship exists between response magnitude and degree of risk.

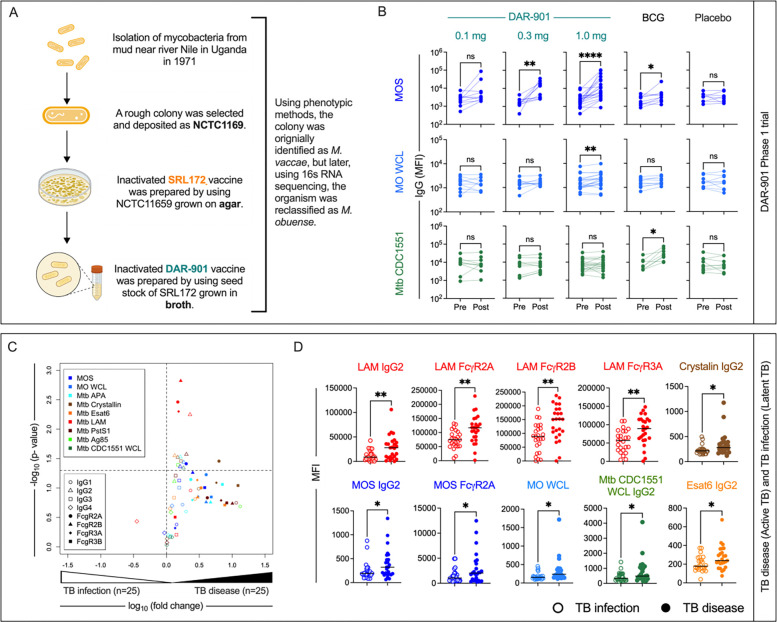

Immunogenicity of M. obuense across TB vaccines

Preparations derived from both agar- (SRL172) and broth-grown (DAR-90147) culture of M. obuense, have been in development as a post-BCG booster vaccine. DAR-901 vaccine, which has completed phase I and II safety and immunogenicity trials in participants with and without HIV infection47,48, was produced using a broth-based manufacturing process from the M. obuense SRL172 master cell bank to improve scalability (Figure 2A). To assess immunogenicity of the DAR-901 vaccine candidate, shown in a murine model to provide protection against TB challenge superior to BCG49, serum drawn from 58 healthy adult participants with prior BCG vaccination and negative TB IFN-γ release assay who received either three doses of DAR-901 at 0.1 mg (n=10), 0.3 mg (n=10) or 1.0 mg (n=20) dose, or three doses of saline placebo (n=9), or two doses of saline and one dose of BCG (n=9) (Supplemental Table 3) were evaluated. Sera from US-based participants in the two higher dose groups of the phase I dose escalation trial (NCT02712424) of DAR-90147 demonstrated recognition of MOS (Figure 2B) at similar or higher levels than in those who received SRL172 in the DarDar trial (Supplemental Figure 5). Longitudinal profiling of samples prior to immunization (Pre) or after dose 3 (Post) demonstrated dose-dependent increases in MOS-specific IgG (Figure 2B). Although smaller in magnitude, MOS-specific IgG was also seen following immunization with BCG, demonstrating that antibodies induced or boosted by BCG cross-react with antigens in MOS. In contrast, there was no increase in MOS-specific IgG responses in the placebo group. Neither DAR-901 nor placebo induced antibodies that cross-reacted with Mtb CDC1551 WCL, whereas immunization with BCG did (Figure 2B). These results demonstrate that additional TB vaccines, including the efficacious BCG vaccine, induce MOS-specific antibodies in humans.

Fig. 2: Cross-reactivity antibodies induced by DAR-901 vaccine, BCG vaccination, and Mtb infection to MOS.

A. History of preparation of DAR-901 vaccine. B. Longitudinal profiling of IgG specific for MOS (top), MO WCL (middle), and Mtb CDC1551 WCL (bottom) profiling for participants of DAR-901 trial Phase 1 trial who were administered either 3 doses of DAR-901 vaccine at 0.1 (n=10), 0.3 (n=10), or 1.0 mg (n=20) doses, 3 doses of saline (Placebo, n=9), or 2 doses of saline and 1 dose of BCG vaccine (BCG, n=9). Statistical analysis was performed by Wilcoxon matched paired sign rank test (****p<0.0001, ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05). C. Volcano plots depicting the magnitude (fold change) and statistical significance (Welch’s t-test) of differences in measured immune features in individuals diagnosed with tuberculosis infection or disease. Dotted horizontal line indicated unadjusted p value of 0.05. Color indicates antigen specificity, while shape indicates the antibody Fc domain characteristic for each response feature measured. D. Box plots comparing the levels of select immune features in subjects with Latent (hollow circle) or Active (solid circle) tuberculosis. Statistical significance was determined by Welch’s t-test (**p<0.01, *p<0.05). Bar indicates median.

MOS-cross-reactive IgG2 is associated with active TB disease

While evaluation following BCG immunization suggested that cross-strain responses could be induced, there was little evidence that M. obuense SRL172 induced antibodies that recognized antigens derived from Mtb strains in multiplex assay testing (Figure 1B). To address whether antibodies associated with Mtb infection could cross-react with MOS, we evaluated responses in a cohort of individuals diagnosed with either active TB disease (n=25) or latent Mtb infection (n=25) (Supplemental Table 4).

Consistent with prior reports17,50, we observed elevated humoral responses in individuals with active TB disease (Figure 2C). In particular, we observed higher LAM-specific responses, specifically IgG2 and binding to FcγR2A, FcγR2B and FcγR3A in individuals with active TB disease (Figure 2D). Multiple Mtb antigens were targeted by elevated levels of IgG2 in individuals with active TB disease, including ESAT6, α-crystallin, APA, Pst1, and Mtb CDC1551 WCL. Lastly, MOS- and MO WCL-specific IgG2 responses were also elevated, the former also showing elevated binding to FcγR2A, which was evaluated with the H131 allotype capable of binding human IgG2 (Figure 2D). Skewing toward IgG2 across a range of antigen-specificities suggests differential regulation of plasmablasts secreting this subclass in the context of active disease, and elevated MOS-specific suggest the generation of cross-reactive antibodies during active TB infection and disease.

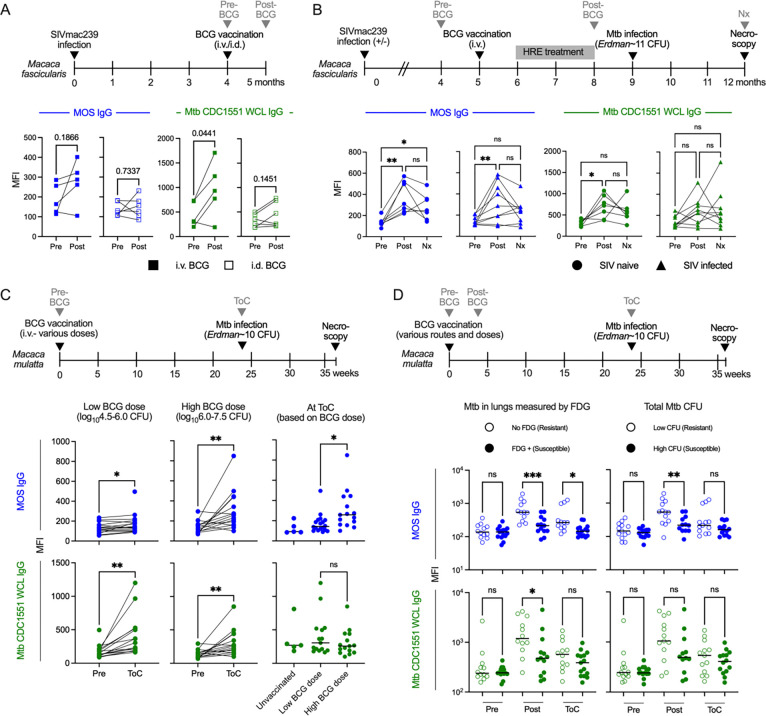

BCG vaccination elicits MOS-specific antibodies in SIV-infected and SIV-naïve cynomolgus macaques

To explore whether cross-reactivity between MOS- and protective TB-specific humoral responses exists in other contexts, we measured relative titers of MOS- and Mtb CDC1551 WCL-specific IgG antibodies in plasma samples acquired from two NHP species, with and without SIV infection, and immunized with BCG at various doses and routes (Supplemental Table 5).

Paralleling the DarDar trial assessment of MOS- and TB-specific humoral responses in PLWH, Macaca fascicularis (cynomolgus macaques) infected with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) strain SIVmac239 were immunized with BCG either intradermally (i.d.) with 5×105 colony forming units (CFU) (n=6) or i.v. with 5×107 CFU followed three weeks later by treatment with isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol (HRE) to prevent disease caused by BCG (n=5)43 (Figure 3A). Plasma samples were collected pre- and one month post-vaccination. Whereas four of five animals receiving i.v. BCG, which confers greater protection than i.d. BCG in SIV-naïve animals35, showed increased MOS- and Mtb CDC1551 WCL-specific IgG, such responses were not elicited following i.d. BCG vaccination (Figure 3A).

Fig. 3: MOS-specific IgG responses are induced by BCG immunization in NHP and are associated with vaccine-mediated protection.

A. Longitudinal profiling at pre- and post-vaccination timepoints of MOS- (blue) and Mtb (CDC1551) WCL- (green) specific IgG responses in SIV-infected M. fascicularis administered i.d. or i.v. BCG and HRE (Isoniazid, Rifampin, Ethambutol) therapy. Statistical significance was determined by paired t-test. B. Longitudinal profiling at pre-vaccination, post-vaccination and necropsy (Nx) timepoints of MOS- and Mtb WCL-specific IgG responses in SIV-infected and naïve M. fascicularis who were administered i.v. BCG and protected from Mtb challenge. Statistical significance was determined by paired one-way ANOVA. C. Longitudinal profiling at pre-vaccination and time of Mtb challenge (ToC) in M. mulatta vaccinated with low (left) and high dose i.v. BCG (center). Statistical significance was determined by paired t-test. MOS- and Mtb WCL-specific IgG responses at ToC by BCG vaccine history (right). Statistical significance was determined by Welch’s t test. D. Longitudinal profiling of MOS- and Mtb WCL-specific IgG responses in M. mulatta by Mtb infection burden determined by 2-deoxy-2-(18F) fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) imaging (left) and by colony forming units of Mtb in lungs (right). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. Significance is indicated as: ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05, ns p≥0.05.

The capacity of i.v. BCG to mediate protection against TB in SIV-infected animals was directly addressed in another study in which cynomolgus macaques with or without prior SIVmac239 infection were immunized with i.v. BCG (Figure 3B). To preclude symptomatic disseminated BCG, animals received a two month regimen of HRE three weeks after vaccination that was discontinued one month prior to challenge with low dose Mtb Erdman (~11 CFU) via bronchoscopic instillation42 (Figure 3B). MOS- and Mtb CDC1551 WCL-specific IgG responses were evaluated in the seven of seven SIV-naïve and nine of twelve SIV-infected animals that were protected from Mtb challenge by i.v. BCG42. Whereas BCG vaccination induced MOS-specific IgG irrespective of SIV infection status, Mtb CDC1551 WCL-specific IgG was induced only in SIV naïve animals (Figure 3B), suggesting that at least in the comparison of these isolate preparations, SIV infection impaired induction of cross-reactive Mtb- but not MOS-specific humoral responses.

MOS-specific IgG is a CoP in BCG-vaccinated rhesus macaques

To assess the generalizability of the association between anti-MOS antibody responses and protection from TB disease, we evaluated the effect of i.v. BCG on protection from TB in Macaca mulatta (rhesus macaques)44. Rhesus macaques were immunized with i.v. BCG (4.5–7.5 log10 CFU) and challenged with low-dose Mtb Erdman at ~six months post-vaccination (Figure 3C). Both MOS- and Mtb CDC1551 WCL-specific IgG (Figure 3C) but not IgM or IgA (Supplemental Figure 6A–C) responses were observed following vaccination with either low or high dose BCG. At the time of Mtb challenge, higher MOS- but not Mtb CDC 1551 WCL-specific IgG was detected in animals that received high (6.0–7.5 log10CFU) as compared to low (4.5–6.0 log10CFU) dose BCG, demonstrating a dose-response relationship between antibody generation and BCG vaccine dose, which is known to influence protection from TB44.

Next, we analyzed plasma from a study of the effect of route and dose of BCG vaccination on protection35. Rhesus macaques (n=25) were vaccinated i.d. with high or low dose BCG, or i.v. with high dose BCG prior to bronchoscopic challenge with Mtb Erdman (~10 CFU). Challenge outcomes were measured by evaluating inflammation in the lungs with PET-CT imaging using 2-deoxy-2-(18F) fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), as well as by determining total Mtb CFU in lung at necropsy. Animals were split by median into two groups: Mtb resistant (low FDG activity or low Mtb CFU at necropsy) or susceptible (>300 FDG activity or high Mtb CFU at necropsy). Resistant animals, comprised mostly of i.v. BCG recipients, demonstrated higher MOS- and Mtb CDC 1551 WCL-specific IgG at both post-vaccination and Mtb challenge timepoints as compared to the susceptible group, which was comprised mostly of i.d. low dose BCG recipients (Figure 3D). No differences in antibody levels were observed at the pre-vaccination timepoint. TB resistant macaques also demonstrated higher MOS-specific IgA responses post-vaccination as compared to the susceptible animals (Supplemental Figure 6D). While MOS-specific IgG responses post-vaccination did not always differ in magnitude in association with route or dose (Supplementary Figure 7), the magnitude of antibody responses to MOS antigens did differ in association with disease resistance across all animals for both FDG (p=0.0029) and CFU (p=0.0047), as well as within the i.d. high dose group for CFU (p=0.015) (Supplementary Figure 8).

Overall, results from these diverse NHP studies demonstrate that BCG vaccination induces antibodies that cross-react with MOS. Elicitation of MOS-specific IgG responses was dose-dependent, observed in two different NHP species, including animals infected with SIV, and, though confounded by differences in vaccine route and dose, correlated with infection outcomes in multiple studies—bolstering the relevance of MOS-specific antibodies as a CoP against Mtb challenge.

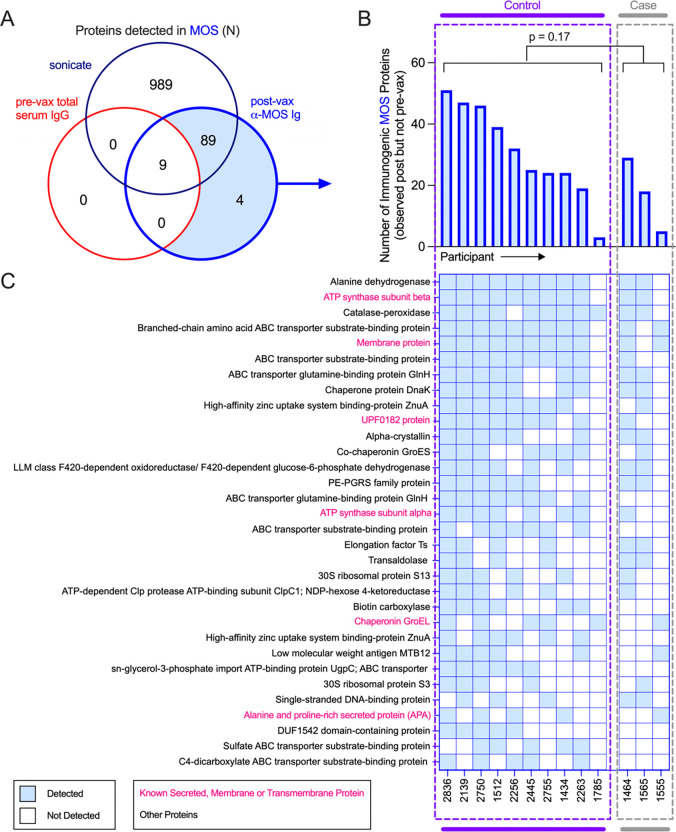

Identification of immunogenic MOS antigens

To identify specific components of MOS recognized by antibodies raised in vaccinated participants in the DarDar trial, we used affinity purification to isolate MOS-specific antibodies post-immunization from a selected subset high IgG responders including ten vaccinated participants who did not develop TB disease (controls) and three vaccinated participants who did develop TB disease (cases) (Supplemental Figure 9A). Pooled total serum IgG from the pre-vaccination timepoint for seven of the ten vaccinated controls from whom MOS-specific Ig was isolated was used as a control. These antibody preparations were then used to affinity purify immunogenic components of MOS, which were then identified using mass spectrometry (Supplemental Figure 9B).

A total of 1,087 proteins were identified in MOS (Figure 4A). Nine of these proteins were pulled down by pooled total serum IgG from the pre-vaccination timepoint and were also targets of antibodies at post-vaccination timepoint, indicating these antigens were targeted by antibodies present prior to vaccination. Of the remaining 1,078 proteins, a total of 93 antigens detected in MOS were targets of MOS-specific antibodies purified from post-vaccination timepoint sera (Figure 4A), ranging from 12–60 proteins per subject. Affinity-purified IgG from individuals who did not develop TB disease enriched a greater number of proteins than sera from definite TB cases (Figure 4B), suggesting a narrower response in vaccinated study participants who went on to be diagnosed with TB. Thirty-two of these antigens were targets of post-vaccination serum antibodies in five or more of the 13 participants tested (Figure 4C), six of which were annotated as membrane-bound, secreted, or transmembrane proteins in UniProt. Amongst these, ATP synthase, chaperonin GroEL, and UPFO182 are relatively well conserved in Mtb and M. obuense (amino acid similarity >79%) (Supplemental Table 6). Overall, these data suggest that antibodies to a diversity of MOS proteins were induced by vaccination with M. obuense SRL172.

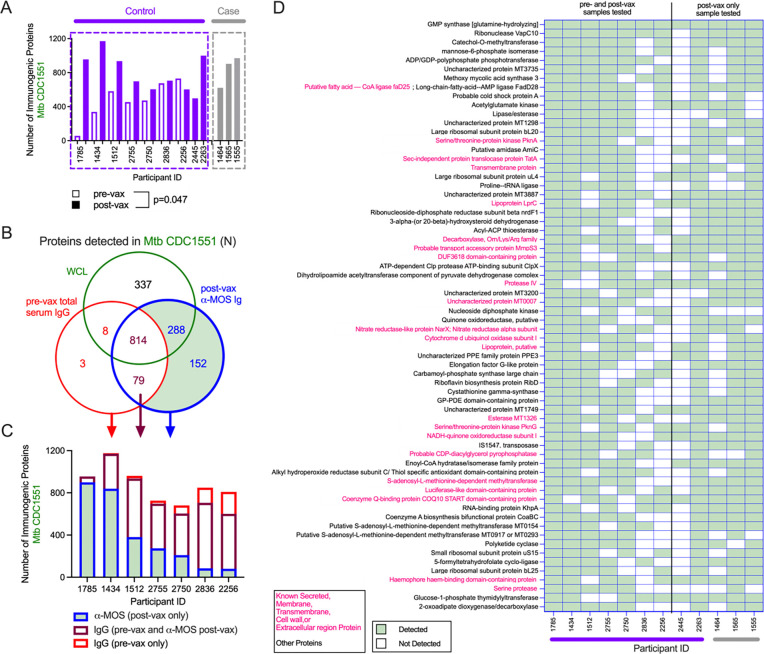

Fig. 4. Identification of immunogenic components in MOS.

A. Venn diagram depicting total proteins detected by mass spectrometry in MOS (navy), or those detected following enrichment with MOS-specific Abs isolated post-vax (blue) or by pre-vax total serum IgG (red). B-C. Total number (B) and identity (C) of proteins in MOS detected in ≥ 5 participants following affinity enrichment using MOS-specific antibody but not pooled IgG by study participant. Statistical significance was determined by Mann-Whitney t test.

Identification of Mtb proteins recognized by MOS-specific antibodies

We next sought to identify components in Mtb CDC1551 WCL to which anti-MOS antibodies bound. MOS-specific antibodies isolated from the serum of nine control and three case study participants with high IgG responses were used to enrich components of Mtb CDC1551 WCL (Supplemental Figure 9). Total serum IgG from the pre-vaccination timepoint from seven of these control subjects was employed to identify Mtb proteins recognized by antibodies present before immunization. While more proteins were generally pulled down by post- as compared to pre-immunization sera, similar numbers of proteins were targeted by post-immunization case and control sera, consistent with selection of high responders in this analysis (Figure 5A). A total of 1,447 proteins were identified from Mtb CDC1551 WCL, of which 814 were targeted by total serum IgG at pre-vaccination as well as MOS-specific serum antibodies at post-vaccination time points (Figure 5B). Relative to the number of immunogenic proteins identified in MOS, this higher number of detected Mtb proteins was surprising, and may be attributable to prior BCG vaccination and Mtb exposure as well as cross-reactive antibodies elicited against common post-translational modifications or heterologous mycobacterial species51–59. Overall, a set of 440 proteins from Mtb CDC1551 WCL were uniquely observed as targets of anti-MOS antibodies post-vaccination (Figure 5B).

Fig. 5: Identification of cross-reactive proteins in Mtb CDC1551 recognized by MOS-specific Abs.

A. Number of proteins in Mtb CDC1551 that bound to MOS-specific antibodies isolated from controls (purple) and cases (gray) at post- (filled) vaccination (vax) timepoint and to total serum IgG isolated at pre-vaccination timepoint (hollow). Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank test was performed to compare number of proteins detected following enrichment by serum antibodies at pre- and post- vaccination timepoint. B. Venn diagram depicting the proteins detected in Mtb CDC1551 WCL (green), those detected following enrichment by MOS-specific antibodies isolated post-vax (blue) or by pre-vax serum total IgG (red). C. Bar plot depicting the number of Mtb CDC1551 proteins recognized by pre-vax total serum IgG (red), post-vax MOS-specific antibodies (blue), or both (mauve). D. Identity of proteins from Mtb CDC1551 detected following enrichment by MOS-specific antibodies post-vax, but not by pre-vax serum IgG in ≥5 participants by participant (controls in purple, cases in gray).

Per participant, considerable heterogeneity was observed in the number of antigenic protein targets that bound only to MOS-specific antibodies at the post-vaccination timepoint, bound only to total serum IgG isolated at pre-vaccination timepoint, or bound to both (Figure 5C). Among the antigenic targets observed only post-vaccination, 66 were observed in five or more of the seven vaccinated control participants (Figure 5D), of which 60 met detection criteria in unfractionated Mtb CDC1551 WCL. Of the remaining six, three were observed to be present at low levels but had been filtered out as they were not identified in all three sample injections. Most of these specificities were also enriched by MOS-specific antibodies from the post-immunization timepoint in the two additional controls and three cases for whom pre-immunization samples were not available. Overall, these data suggest that MOS-specific antibodies cross-react with a surprising number of Mtb proteins, consistent with a broad humoral response.

Discussion

Investigational TB vaccines have shown promise to boost or replace childhood BCG immunization79–81. Beyond the demonstrated efficacy of vaccination with M. obuense SRL172 in the DarDar trial9, recent studies of re-routing (i.v.)35,42 or re-vaccinating with BCG5,60, and novel candidates61–63 provide hope for new insights and options to protect vulnerable populations from one of the oldest of human diseases. However, development of effective TB vaccines at all stages is hampered by the lack of established CoP3,6,61,64.

We report identification of a humoral CoP by applying systems serology tools to case-control samples from the successful phase III DarDar prevention of disease trial of SRL172 vaccine. Affinity purification and mass spectrometric analysis revealed antibodies to a diversity of immunogenic antigens in MOS and cross-reactivity with those in Mtb. Since epidemiologic studies in humans have demonstrated that infection with non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) can protect against subsequent TB disease, and a number of inactivated whole cell vaccines have been used to prevent TB52,54,65, these data suggest a similar mechanism of inducing cross-reactive immunity for inactivated M. obuense.

Not only did IgG, IgM, and IgA antibody responses to the vaccine strain sonicate (MOS) correlate with vaccine-mediated protection from TB disease, among subjects who did develop breakthrough TB disease, greater magnitude MOS-specific IgG and IgM responses associated with greater time to disease diagnosis among cases. Generalizability of this human humoral CoP was confirmed by NHP studies of BCG vaccine-mediated protection from TB, and biological relevance suggested by cross-reactivity of MOS-specific antibodies with M obuense and Mtb. These discoveries present a milestone in TB vaccine development.

In sum, data presented here demonstrates correlations between humoral responses to MOS and protection from TB disease in humans immunized with MOS, humans not immunized with SRL172 (DarDar placebo recipients), as well as BCG-vaccinated NHP. Yet, it does not provide evidence as to mechanism(s) of protection. Indeed, strong mechanistic evidence exists that i.v. BCG-elicited protection is mediated by T cells in NHP66. Increased rates of active disease in both CD4 knock-out mice67–69 as well as in humans with low CD4 T cell counts70,71 further support the mechanistic importance of cellular responses.

Nonetheless, insight into the targets of MOS-specific antibodies have the potential to refine our understanding of cross-reactivity between NTM and disease-causing mycobacteria in ways that are relevant for TB prevention and treatment. Numerous antigenic proteins were identified in both Mtb and M. obuense strains. Further study to elucidate both targets and mechanism(s) of protection are needed to understand the potential biological relevance of the antigens identified.

Study and sample sizes were small, and sufficient volumes of DarDar study samples were not available for all timepoints and tests for the participants selected for case-control analysis. We did not analyze the potentially confounding influence of clinical or demographic variables or stratify humoral responses by the presence or absence of T cell immune responses, so cannot characterize the interplay between the identified humoral CoP and cellular immune responses known to be critical to protection from tuberculosis. While we found a clear and consistent pattern of elicitation of MOS-specific antibodies in human and NHP recipients of three TB vaccines, this study cannot assess whether these humoral CoP are relevant to protection from TB seen in other vaccines. Such studies are now a high priority next step for TB vaccine development.

Given the exploratory nature of these studies, statistical analyses did not adjust for multiple comparisons, but instead relied on comparison of distributions of differences observed at pre-vaccination timepoints and in placebo recipients as study- and dataset-specific means to gauge risk of false discovery. Nonetheless, the association of antibody levels with both protection from TB along with the identification of cross-reactive antigens between M. obuense and Mtb across multiple vaccine platforms and species argues strongly that the association results from relevance rather than chance. While we confirmed the elicitation of analogous humoral responses in recipients of the broth-grown M. obuense DAR-901 vaccine, we could not repeat the CoP identification since subjects in early phase trials for which samples were available were not followed for the development of TB.

Identification of a humoral CoP for vaccine-induced protection against TB can help accelerate the development of DAR-901 and other promising TB vaccine candidates by providing a new target for immunogenicity assessments and dose finding studies. Further, these findings add to a growing body of evidence motivating reexamination of the role of humoral immunity in marking or contributing to protection from TB disease24,27,33,72–83. It will be interesting to extend these studies in other contexts, such as BCG immunization in infants or in BCG re-vac and M72 trials62,84–86.

Online Methods

Serum/Plasma samples

This study evaluated pre- and post-immunization serum samples from participants in the randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind DarDar phase III9 (105 placebo, 95 vaccine recipients, Supplemental Table 1) and the randomized, placebo- and BCG-controlled, double-blind, dose ranging DAR-90147 phase I (9 placebo, 40 Dar 901, and 9 BCG vaccine recipients, Supplemental Table 3) trials. These studies evaluated immunization with either agar- (DarDar) or broth- (DAR-901) grown M. obuense in Tanzania and the United States, respectively. Briefly, whereas the DarDar trial included adult residents of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania living with HIV, and who had CD4 cell counts of at least 200 cells/μl and a BCG scar, the DAR-901 study included adult residents of the United States living with or without HIV and with a history of childhood BCG vaccination evidenced by BCG scar. In the DarDar study, endpoints evaluated included disseminated, definite, and probable TB; statistically significant protection against definite TB, defined by a positive blood culture for Mtb, a positive sputum culture with ≥10 CFU, two positive sputum cultures with 1–9 CFU, two positive sputum smears with ≥2 acid-fast bacilli/100 oil immersion fields or a positive culture or positive acid-fast bacillus smear and caseous necrosis from a sterile site other than blood was observed9. In our case-control sub-study, participants who developed definite TB after immunization were considered as cases and subjects who developed definite TB after immunization were considered as controls. The DarDar study was approved by the Dartmouth Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, by the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS) Research Ethics Committee, and by the Division of AIDS Clinical Science Review Committee, National Institutes of Health (NIH). The DAR-901 phase I study was approved by Dartmouth Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects. All participants in both studies gave written informed consent.

Lastly, serum samples from study participants diagnosed with active TB disease (n = 25) or latent TB infection (n = 25) were obtained from Duke University Medical Center (Supplemental Table 4). The TB disease group included participants with either culture-confirmed TB (n = 22) or diagnosis per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria (n = 3). Sample collection was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board and participants provided written informed consent.

Plasma samples from cynomolgus (Macaca fascicularis) or rhesus (Macaca mulatta) macaques were collected from studies of BCG immunization35,42–44 (Supplemental Table 5) performed at University of Pittsburgh, Bioqual Inc., and the National Institutes of Health Vaccine Research Center (VRC). Experimentation and sample collection from each original study was approved by the appropriate local Animal Care and Use Committee, with adherence to guidelines established in the Animal Welfare Act and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the Weatherall Report (8th Edition).

Fc Array Antibody Profiling

A panel (Supplemental Table 2) of recombinant or purified native antigens (Ag 85, APA, α-crystallin, ESAT6, GroES, LAM, Mpt64, and PstS1) as well as complex mixtures (agar-grown M. obuense sonicate, broth-grown M. obuense, Mtb CDC1551, Mtb 91_0079 whole cell lysates, and cytosolic, membrane, and culture filtrate fractions of Mtb H37Rv) were used for profiling humoral immune responses using a multiplexed binding assay.

Briefly, magnetic carboxylated microspheres (Luminex Magplex) were coupled to each antigen preparation using a two-step carbodiimide reaction as described previously87. As needed, preparations were buffer-exchanged into phosphate buffered saline (PBS) using G-25 (Cytivia, 28918004) columns following manufacturer’s protocol to ensure that there were no primary amine groups in the buffer. LAM was modified using DMTMM (4-(4,6-Dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium chloride) (Millipore Sigma, 72104) and coupled using protocols described previously33,88.

The levels and Fc characteristics of antigen-specific antibodies were evaluated by multiplex assay as described previously87. Serum samples were thawed, diluted in assay buffer (PBS + 1% BSA + 0.1% Tween20), and added to 384 well plates (Greiner bio-one, 781906). A master mixture of antigen-coupled beads was prepared in assay buffer and 45 μL of the mixture was added to each well, such that each well would contain 500 beads per bead region. The final concentration of serum/plasma was 1:100 diluted. The plate was sealed and incubated for 2 hours 15 min at 1,000 rpm at room temperature. Following six washes using an automated magnetic plate washer, bound antigen-specific antibodies were detected with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-human or anti-rhesus secondary reagents (Supplemental Table 7), or site-specifically biotinylated and tetramerized (Streptavidin-PE (Agilent, Technologies, PJ31S-1)) human Fc receptors (FcγR2A H131, FcγR2B, FcγR3A V158, FcγR3B, FcαR)89 at a concentration of 0.65 μg/mL, as described previously45. Plates were sealed and incubated for 1 hour 5 min at 1,000 rpm at room temperature, washed 6 times using an automated magnetic plate washer, and beads were resuspended in 50 μL sheath fluid (Luminex™ xMAP Sheath Fluid Plus, 4050021) prior to sealing and agitation at 1,000 rpm for 5 min at room temperature. Data was acquired on a FlexMAP 3D™ (Luminex), which detected the beads and measured PE fluorescence in order to calculate the median fluorescent intensity (MFI) level for each analyte.

Immunogenic Peptide Identification

A tandem affinity purification – affinity purification – mass spectrometry (AP-AP-MS) strategy (Supplemental Figure 9) was used to first enrich MOS-specific antibodies from post-immunization timepoint serum samples from selected (n=13; 10 control, 3 case) DarDar trial participants that exhibited particularly high MOS-specific antibody responses and for whom sufficient sample was available, and then to capture and identify the MOS components specifically bound by these antibodies.

Affinity purification of MOS-specific and control antibodies

Briefly, a 1 mg (i.e., 100 μL) mass of Dynabeads® MyOne™ Carboxylic Acid (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 65012) were conjugated with 50 μg of antigen using two-step carbodiimide reaction. A 100 μL volume of beads was washed with 20 mM MES (2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid) (pH 6.0) (Sigma Aldrich, M3671). Post washing, 25 μL of 50 μg/μL of EDC (1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride)) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 22980) and 25 μL of 50 μg/μL sulfo-NHS (N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 24510), each prepared in ice-cold MES buffer (pH 6.0), were added to the beads, which were then mixed using a vortex and allowed to incubate on a rotational shaker for 30 min at room temperature. The resulting activated beads were washed twice with 150 μL of MES buffer, to which 50 μg of MOS in 50 μL of MES buffer was added. After mixing the sample and the beads, the tube was allowed to incubate on a rotational shaker for 30 min at room temperature. MOS-conjugated beads were then resuspended in 150 μL 50 mM Tris pH 7.4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15567027) for 15 min at room temperature on a rotational shaker. The beads were then washed 4 times with 1X PBS-TBN (Teknova Inc., P0210), resuspended in PBS-TBN, and stored at 4°C. This bead-preparation protocol was scaled according to the quantity of beads needed for processing the desired number of serum samples.

A 100 μL volume of serum sample was mixed with 20 μL of unconjugated beads that had been washed twice with PBS-TBN, and incubated on a rotational shaker for 1 hr 30 min at room temperature. Following depletion of bead-reactive proteins, serum supernatant was withdrawn and then allowed to mix with 20 μL of MOS-conjugated beads at 4°C overnight on a rotational shaker. Unbound serum proteins were removed by washing 3x with PBS-TBN. For elution, the beads were incubated with 50 μL of 1% formic acid (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 28905) on rotational shaker for 10 min at room temperature. The elution step was repeated and eluate fractions combined and protein content estimated by measuring absorbance at 280 nm. Enrichment was confirmed by testing the binding of the eluted anti-MOS antibodies and flow-through serum (various concentrations) to MOS-conjugated Dynabeads® MyOne™ Carboxylic Acid, using flow cytometry, and detection using PE labeled anti-human IgG antibody (Southern Biotech, 9040–09).

As a control, total serum IgG from pre-vaccination time points of vaccinated control participants were isolated by using Melon™ Gel IgG spin purification kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 45206) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Due to limited sample availability, total serum IgG could be prepared from only seven of the ten samples from which MOS-specific antibodies were isolated at the post-immunization timepoint.

Affinity purification of MOS and Mtb antigens bound by MOS-specific or total serum IgG antibodies

A 25 μg mass of either anti-MOS antibodies (post-vaccination) from individual participants or pooled total serum IgG (pre-vaccination) was conjugated on Dynabeads® MyOne™ Carboxylic Acid as described above. To identify the immunogenic components of MOS, antibody-conjugated beads were incubated with 50 μg MOS in 50 μL PBS-TBN overnight on a rotational shaker at 4°C. The beads were then washed and the components in MOS that bound to the anti-MOS antibodies were subsequently eluted using 1% formic acid and 0.5M sodium phosphate dibasic for analysis by mass spectrometry.

To identify the components of Mtb that were recognized by MOS-specific antibodies, Dynabeads® MyOne™ Carboxylic Acid beads conjugated with MOS-specific antibodies (post-vaccination), or, as a control, total IgG from serum (pre-vaccination) from individual participants, were incubated with Mtb CDC1551 WCL (BEI NR-14823) (50 μg in 50 μL PBS-TBN). Similar steps as described above were followed to affinity purify and elute antigens in Mtb WCL that bound to MOS-specific antibodies.

Mass spectrometric (MS) sample preparation

Eluted components, or as controls, 20 μg total MOS or Mtb CDC1551 (BEI NR-14823), to be analyzed on mass spectrometer were mixed with MS grade water (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 51140) to make a final volume of 65 μL. To this solution, 65 μL of 100% TFE (2,2,2-trifluoroethanol) (Honeywell, 0584150ML) and 6.5 μL of 100 mM DTT (dithiothreitol) (Roche, 10708984001) was added, followed by heating at 55 °C for 45 min. After this denaturation step, the sample was allowed to cool down at room temperature for 15 min prior to addition of 3.9 μL of 550 mM IAM (iodoacetamide) (VWR, M216–30G) and incubation in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. Samples were then diluted with 1159.6 μL of 40 mM Tris hydrochloride (pH 7.5) and trypsin (1:30 (w/w) trypsin/protein) (ThermoFisher Scientific, 90059) was added prior to incubation at 37 °C for approximately 14 hours. The trypsin digestion was stopped by adding 13 μL of 100% formic acid to the solution. Sample volume was reduced under vacuum in a centrifuge concentrator (Eppendorf, 022820168) so that the final volume was approximately 150 μL. Sample cleanup was carried out using Pierce™ C18 Spin tips (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 84850). The peptides were allowed to bind to tips, washed three times with 0.1% formic acid, eluted in a buffer containing 60% acetonitrile and 40% of 0.1% formic acid solution in low protein binding tubes (ThermoFisher Scientific, 90410), and allowed to dry under vacuum. N-linked glycans were cleaved by addition of 500 units of glycerol-free PNGase F (New England Biolabs, P0709S) per 20 μg of protein and the total sample volume was adjusted to 17 μL using 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate (Millipore Sigma, A6141) for incubation at 37 °C for 1 hour. A 2 μL volume of 1% formic acid and 1 μL acetonitrile (ThermoFisher Scientific, 85188) was added, and samples were transferred into mass spectrometry injection vials (ThermoFisher Scientific, 6ERV1103PPC and 6ARC11ST10R). This protocol was scaled according to the concentration of protein in the sample as measured by absorbance at 280 nm.

Samples were analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry using an Easy-nLC 1200 (ThermoFisher Scientific) connected to an Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid (ThermoFisher Scientific). Peptides were passed through a PepMax RSLC C18 (ThermoFisher Scientific, 164946) prior to separation on an EasySpray HPLC column (ThermoFisher Scientific, ES903) using a 1.6%–76% (v/v) acetonitrile gradient over 90 mins at 300 nL/min. Eluted peptides were injected into the mass spectrometer using an EASY-Spray source. Peptides were analyzed in data-dependent mode with parent ion scans collected at a resolution of 120,000in the orbitrap. Monoisotopic precursor selection and charge state screening were used. Ions with charges ≥+2 were selected for collision-induced dissociation (CID) fragmentation, and MS2 spectra were acquired in the ion trap, with a maximum of 20 MS2 scans per MS1. A dynamic exclusion duration of 15-s was used to exclude ions selected more than twice in a 30-s window. Each sample was injected three times to generate technical replicate datasets.

MS – MS data analysis

Protein sequence databases were constructed by downloading the M. obuense and Mtb CDC1551 proteomes from UniProt90. The sequence database of each organism was merged with a list of common protein contaminants (MaxQuant) to make the final database, against which the spectra was searched using SEQUEST (Proteome Discoverer 2.4, ThermoFisher Scientific). Searches considered fully tryptic peptides only and allowed up to two missed cleavages. A precursor mass tolerance of 5 ppm and fragment mass tolerance of 0.5 Da were used. Modifications of carbamidomethyl cysteine (static) and oxidized methionine, and formylated lysine, serine, and threonine (dynamic) were selected. High-confidence peptide-spectrum matches (PSMs) were filtered at a false discovery rate of <1% as calculated by Percolator (q-value <0.01, Proteome Discoverer 2.4; ThermoFisher Scientific). For each scan, PSMs were ranked first by posterior error probability (PEP), then q-value, and finally XCorr. The average mass deviation (AMD) for each peptide was calculated as described previously91, and peptides with |AMD| >1.5 ppm were removed. Ambiguous peptide mass matches (i.e. peptides that matched with <90% amino acid identity to more than one unique protein without homologous regions) were removed. For each peptide, a total extracted-ion chromatogram (XIC) area was calculated as the sum of all unique peptide XIC (extracted ion chromatogram) areas of associated precursor ions.

The detected peptides were filtered such that the PSM count was ≥3. A protein was considered to be detected if at least one of its fragments was detected during mass spectrometry. A list of proteins detected in samples was made. The lists of proteins detected in pre- and post-immunization timepoints were compared in order to identify those that were detected at the post-vaccination timepoint but were not observed at the pre-vaccination timepoint.

Additionally, 10 μg of buffer exchanged DAR-901and SRL172 vaccine samples (Cytivia, 28918004) were also detected by mass spectrometry. The samples were diluted in MS grade water to make the total sample volume of 50 μL. Volumes of other reagents were scaled proportionally following the description provided for sample preparation and mass spectrometric detection as described above. Lists of identified peptides were compared between each vaccine preparation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the DarDar and DAR-901 study teams and participants for their contributions, as well as BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH for providing Mtb antigens. The anti-rhesus IgA (9B9) was provided by the NIH Nonhuman Primate Reagent Resource (NIAID U24 AI126683).

Funding

This study was supported by NIH NIGMS P20 GM113132 and N0140082. E.C.L. was supported by NIH K01 OD033539. NHP studies in i.v. BCG vaccination, SIV-infected Mauritian cynomolgus macaques were supported by R01 AI155345 and AI111815 (to C.A.S.). The research on latent and active TB was supported in part by NIH N01AI40082 (PI Kent Weinhold) and 5P30 AI064518 (PI Georgia Tomaras).

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data Availability

The raw proteomic data has been deposited in MassIVE (https://massive.ucsd.edu/ProteoSAFe/static/massive.jsp). The raw data for measurement of immune responses from human subjects is available in the data files.

References

- 1.Silva S., Arinaminpathy N., Atun R., Goosby E. & Reid M. Economic impact of tuberculosis mortality in 120 countries and the cost of not achieving the Sustainable Development Goals tuberculosis targets: a full-income analysis. Lancet Glob Health 9, e1372–e1379, doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00299-0 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glynn J. R. et al. The effect of BCG revaccination on all-cause mortality beyond infancy: 30-year follow-up of a population-based, double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial in Malawi. Lancet Infect Dis 21, 1590–1597, doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30994-4 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nemes E. et al. The quest for vaccine-induced immune correlates of protection against tuberculosis. Vaccine Insights 1, 165–181, doi: 10.18609/vac/2022.027 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Reyn C. F. Correcting the record on BCG before we license new vaccines against tuberculosis. J R Soc Med 110, 428–433, doi: 10.1177/0141076817732965 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nemes E. et al. Prevention of M. tuberculosis Infection with H4:IC31 Vaccine or BCG Revaccination. N Engl J Med 379, 138–149, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714021 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatt K., Verma S., Ellner J. J. & Salgame P. Quest for correlates of protection against tuberculosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol 22, 258–266, doi: 10.1128/CVI.00721-14 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ginsberg A. M. Designing tuberculosis vaccine efficacy trials - lessons from recent studies. Expert Rev Vaccines 18, 423–432, doi: 10.1080/14760584.2019.1593143 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghebreyesus T. A. & Lima N. T. The TB Vaccine Accelerator Council: harnessing the power of vaccines to end the tuberculosis epidemic. Lancet Infect Dis 23, 1222–1223, doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00589-3 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Reyn C. F. et al. Prevention of tuberculosis in Bacille Calmette-Guerin-primed, HIV-infected adults boosted with an inactivated whole-cell mycobacterial vaccine. Aids 24, 675–685, doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283350f1b (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Reyn C. F., Arbeit R. D. & Horsburgh C. R. HIV-Associated Tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 391, 1662–1663, doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2411285 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waddell R. D. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a five-dose series of inactivated Mycobacterium vaccae vaccination for the prevention of HIV-associated tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis 30 Suppl 3, S309–315, doi: 10.1086/313880 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vuola J. M. et al. Immunogenicity of an inactivated mycobacterial vaccine for the prevention of HIV-associated tuberculosis: a randomized, controlled trial. Aids 17, 2351–2355, doi: 10.1097/00002030-200311070-00010 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lahey T. et al. Immunogenicity of a protective whole cell mycobacterial vaccine in HIV-infected adults: a phase III study in Tanzania. Vaccine 28, 7652–7658, doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.09.041 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bothamley G. H., Rudd R., Festenstein F. & Ivanyi J. Clinical value of the measurement of Mycobacterium tuberculosis specific antibody in pulmonary tuberculosis. Thorax 47, 270–275, doi: 10.1136/thx.47.4.270 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang S. et al. Evaluation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific antibody responses for the discrimination of active and latent tuberculosis infection. Int J Infect Dis 70, 1–9, doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.01.007 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maekura R. et al. Serum antibody profiles in individuals with latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Microbiol Immunol 63, 130–138, doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12674 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nziza N. et al. Defining Discriminatory Antibody Fingerprints in Active and Latent Tuberculosis. Front Immunol 13, doi: ARTN 856906 10.3389/fimmu.2022.856906 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li H. et al. Latently and uninfected healthcare workers exposed to TB make protective antibodies against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, 5023–5028, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1611776114 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glatman-Freedman A. et al. Antigenic evidence of prevalence and diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis arabinomannan. J Clin Microbiol 42, 3225–3231, doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.7.3225-3231.2004 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamasur B. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis arabinomannan-protein conjugates protect against tuberculosis. Vaccine 21, 4081–4093, doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00274-3 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Achkar J. M. & Casadevall A. Antibody-mediated immunity against tuberculosis: implications for vaccine development. Cell Host Microbe 13, 250–262, doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.02.009 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodriguez A. et al. Role of IgA in the defense against respiratory infections IgA deficient mice exhibited increased susceptibility to intranasal infection with Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Vaccine 23, 2565–2572, doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.11.032 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tran A. C. et al. Mucosal Therapy of Multi-Drug Resistant Tuberculosis With IgA and Interferon-gamma. Front Immunol 11, 582833, doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.582833 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balu S. et al. A novel human IgA monoclonal antibody protects against tuberculosis. J Immunol 186, 3113–3119, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003189 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buccheri S. et al. Prevention of the post-chemotherapy relapse of tuberculous infection by combined immunotherapy. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 89, 91–94, doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2008.09.001 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chambers M. A., Gavier-Widen D. & Hewinson R. G. Antibody bound to the surface antigen MPB83 of Mycobacterium bovis enhances survival against high dose and low dose challenge. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 41, 93–100, doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.01.004 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamasur B. et al. A mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan specific monoclonal antibody and its F(ab’) fragment prolong survival of mice infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Exp Immunol 138, 30–38, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02593.x (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopez Y. et al. Induction of a protective response with an IgA monoclonal antibody against Mycobacterium tuberculosis 16kDa protein in a model of progressive pulmonary infection. Int J Med Microbiol 299, 447–452, doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2008.10.007 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teitelbaum R. et al. A mAb recognizing a surface antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis enhances host survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95, 15688–15693, doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15688 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams A. et al. Passive protection with immunoglobulin A antibodies against tuberculous early infection of the lungs. Immunology 111, 328–333, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01809.x (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishnananthasivam S. et al. An anti-LpqH human monoclonal antibody from an asymptomatic individual mediates protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. NPJ Vaccines 8, 127, doi: 10.1038/s41541-023-00710-1 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watson A. et al. Human antibodies targeting a Mycobacterium transporter protein mediate protection against tuberculosis. Nat Commun 12, 602, doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-20930-0 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Irvine E. B. et al. Robust IgM responses following intravenous vaccination with Bacille Calmette-Guerin associate with prevention of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in macaques. Nat Immunol 22, 1515–1523, doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-01066-1 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Irvine E. B. et al. Humoral correlates of protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis following intravenous Bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination in rhesus macaques. bioRxiv, doi: 10.1101/2023.07.31.551245 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Darrah P. A. et al. Prevention of tuberculosis in macaques after intravenous BCG immunization. Nature 577, 95–102, doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1817-8 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kwan C. K. & Ernst J. D. HIV and Tuberculosis: a Deadly Human Syndemic. Clin Microbiol Rev 24, 351-+, doi: 10.1128/Cmr.00042-10 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manosuthi W., Wiboonchutikul S. & Sungkanuparph S. Integrated therapy for HIV and tuberculosis. Aids Res Ther 13, doi:ARTN 22 10.1186/s12981-016-0106-y (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coker R. J., Hellyer T. J., Brown I. N. & Weber J. N. Clinical Aspects of Mycobacterial Infections in Hiv-Infection. Res Microbiol 143, 377–381, doi:Doi 10.1016/0923-2508(92)90049-T (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Narain J. P., Raviglione M. C. & Kochi A. Hiv-Associated Tuberculosis in Developing-Countries - Epidemiology and Strategies for Prevention. Tubercle Lung Dis 73, 311–321, doi:Doi 10.1016/0962-8479(92)90033-G (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoft D. F. Tuberculosis vaccine development: goals, immunological design, and evaluation. Lancet 372, 164–175, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61036-3 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.von Reyn C. F. & Vuola J. M. New vaccines for the prevention of tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis 35, 465–474, doi: 10.1086/341901 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larson E. C. et al. Intravenous Bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination protects simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques from tuberculosis. Nat Microbiol 8, 2080–2092, doi: 10.1038/s41564-023-01503-x (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jauro S. et al. Intravenous Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) Induces a More Potent Airway and Lung Immune Response than Intradermal BCG in Simian Immunodeficiency Virus-infected Macaques. J Immunol 213, 1358–1370, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2400417 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Darrah P. A. et al. Airway T cells are a correlate of i.v. Bacille Calmette-Guerin-mediated protection against tuberculosis in rhesus macaques. Cell Host Microbe 31, 962–977 e968, doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2023.05.006 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown E. P. et al. Multiplexed Fc array for evaluation of antigen-specific antibody effector profiles. J Immunol Methods 443, 33–44, doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2017.01.010 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown E. P. et al. Optimization and qualification of an Fc Array assay for assessments of antibodies against HIV-1/SIV. J Immunol Methods 455, 24–33, doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2018.01.013 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.von Reyn C. F. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated whole cell tuberculosis vaccine booster in adults primed with BCG: A randomized, controlled trial of DAR-901. PLoS One 12, e0175215, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175215 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Munseri P. et al. DAR-901 vaccine for the prevention of infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis among BCG-immunized adolescents in Tanzania: A randomized controlled, double-blind phase 2b trial. Vaccine 38, 7239–7245, doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.055 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lahey T. et al. Immunogenicity and Protective Efficacy of the DAR-901 Booster Vaccine in a Murine Model of Tuberculosis. PLoS One 11, e0168521, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168521 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li Y. et al. Improving the diagnosis of active tuberculosis: a novel approach using magnetic particle-based chemiluminescence LAM assay. BMC Pulm Med 24, 100, doi: 10.1186/s12890-024-02893-2 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jones A. et al. Elevated serum antibody responses to synthetic mycobacterial lipid antigens among UK farmers: an indication of exposure to environmental mycobacteria? RSC Med Chem 12, 213–221, doi: 10.1039/d0md00325e (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fine P. E. Variation in protection by BCG: implications of and for heterologous immunity. Lancet 346, 1339–1345, doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92348-9 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Edwards M. L. et al. Infection with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare and the protective effects of Bacille Calmette-Guerin. J Infect Dis 145, 733–741, doi: 10.1093/infdis/145.2.733 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Edwards L. B., Acquaviva F. A. & Livesay V. T. Identification of tuberculous infected. Dual tests and density of reaction. Am Rev Respir Dis 108, 1334–1339, doi: 10.1164/arrd.1973.108.6.1334 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fordham von Reyn C. et al. The international epidemiology of disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex infection in AIDS. International MAC Study Group. Aids 10, 1025–1032, doi: 10.1097/00002030-199610090-00014 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.von Reyn C. F. et al. Sources of disseminated Mycobacterium avium infection in AIDS. J Infect 44, 166–170, doi: 10.1053/jinf.2001.0950 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.von Reyn C. F. et al. Isolation of Mycobacterium avium complex from water in the United States, Finland, Zaire, and Kenya. J Clin Microbiol 31, 3227–3230, doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.12.3227-3230.1993 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.von Reyn C. F. et al. Evidence of previous infection with Mycobacterium avium-Mycobacterium intracellulare complex among healthy subjects: an international study of dominant mycobacterial skin test reactions. J Infect Dis 168, 1553–1558, doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.6.1553 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gilks C. F. et al. Disseminated Mycobacterium avium infection among HIV-infected patients in Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 8, 195–198 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dos Santos P. C. P. et al. Effect of BCG vaccination against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in adult Brazilian health-care workers: a nested clinical trial. Lancet Infect Dis 24, 594–601, doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00818-6 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scriba T. J., Netea M. G. & Ginsberg A. M. Key recent advances in TB vaccine development and understanding of protective immune responses against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Semin Immunol 50, 101431, doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2020.101431 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Van Der Meeren O. et al. Phase 2b Controlled Trial of M72/AS01(E) Vaccine to Prevent Tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 379, 1621–1634, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803484 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tait D. R. et al. Final Analysis of a Trial of M72/AS01(E) Vaccine to Prevent Tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 381, 2429–2439, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1909953 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Andersen P. & Scriba T. J. Moving tuberculosis vaccines from theory to practice. Nat Rev Immunol 19, 550–562, doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0174-z (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Collins F. M. The relative immunogenicity of virulent and attenuated strains of tubercle bacilli. Am Rev Respir Dis 107, 1030–1040, doi: 10.1164/arrd.1973.107.6.1030 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simonson A. W. et al. CD4 T cells and CD8alpha+ lymphocytes are necessary for intravenous BCG-induced protection against tuberculosis in macaques. bioRxiv, doi: 10.1101/2024.05.14.594183 (2024). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yao S. et al. CD4+ T cells contain early extrapulmonary tuberculosis (TB) dissemination and rapid TB progression and sustain multieffector functions of CD8+ T and CD3-lymphocytes: mechanisms of CD4+ T cell immunity. J Immunol 192, 2120–2132, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301373 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Caruso A. M. et al. Mice deficient in CD4 T cells have only transiently diminished levels of IFN-gamma, yet succumb to tuberculosis. J Immunol 162, 5407–5416 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lin P. L. et al. CD4 T cell depletion exacerbates acute Mycobacterium tuberculosis while reactivation of latent infection is dependent on severity of tissue depletion in cynomolgus macaques. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 28, 1693–1702, doi: 10.1089/AID.2012.0028 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lawn S. D., Butera S. T. & Shinnick T. M. Tuberculosis unleashed: the impact of human immunodeficiency virus infection on the host granulomatous response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbes Infect 4, 635–646, doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01582-4 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Geldmacher C. et al. Preferential infection and depletion of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific CD4 T cells after HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med 207, 2869–2881, doi: 10.1084/jem.20100090 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Glatman-Freedman A. & Casadevall A. Serum therapy for tuberculosis revisited: reappraisal of the role of antibody-mediated immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 11, 514–532, doi: 10.1128/CMR.11.3.514 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Forget A., Benoit J. C., Turcotte R. & Gusew-Chartrand N. Enhancement activity of anti-mycobacterial sera in experimental Mycobacterium bovis (BCG) infection in mice. Infect Immun 13, 1301–1306, doi: 10.1128/iai.13.5.1301-1306.1976 (1976). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Feldman W. H., Karlson A. G. & Hinshaw H. C. Streptomycin in experimental tuberculosis: the effects in guinea pigs following infection in intravenous inoculation. Am Rev Tuberc 56, 346–359 (1947). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Murray J. F., Schraufnagel D. E. & Hopewell P. C. Treatment of Tuberculosis. A Historical Perspective. Ann Am Thorac Soc 12, 1749–1759, doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201509-632PS (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Flick L. F. Serum treatment in tuberculosis. Rep Henry Phipps Inst, 87–102 (1905). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Maragliano E. Le sérum antituberculeux et son antitoxine. Georges Carré (1896). [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gamgee A. DR. VIQUERAT’S TREATMENT OF TUBERCULOSIS. Lancet 144(3710), 811–813 (1894). [Google Scholar]

- 79.PAQUIN P. The treatment of tuberculosis by injections of immunized blood serum. Journal of the American Medical Association 24 (22), 842–845 (1895). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kawahara J. Y., Irvine E. B. & Alter G. A Case for Antibodies as Mechanistic Correlates of Immunity in Tuberculosis. Front Immunol 10, 996, doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00996 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Olivares N. et al. Prophylactic effect of administration of human gamma globulins in a mouse model of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 89, 218–220, doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2009.02.003 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Olivares N. et al. The protective effect of immunoglobulin in murine tuberculosis is dependent on IgG glycosylation. Pathog Dis 69, 176–183, doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12069 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hangartner L., Zinkernagel R. M. & Hengartner H. Antiviral antibody responses: the two extremes of a wide spectrum. Nat Rev Immunol 6, 231–243, doi: 10.1038/nri1783 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tameris M. D. et al. Safety and efficacy of MVA85A, a new tuberculosis vaccine, in infants previously vaccinated with BCG: a randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet 381, 1021–1028, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60177-4 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fletcher H. A. et al. T-cell activation is an immune correlate of risk in BCG vaccinated infants. Nat Commun 7, 11290, doi: 10.1038/ncomms11290 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Penn-Nicholson A. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of candidate vaccine M72/AS01E in adolescents in a TB endemic setting. Vaccine 33, 4025–4034, doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.05.088 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Brown E. P. et al. High-throughput, multiplexed IgG subclassing of antigen-specific antibodies from clinical samples. J Immunol Methods 386, 117–123, doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2012.09.007 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schlottmann S. A., Jain N., Chirmule N. & Esser M. T. A novel chemistry for conjugating pneumococcal polysaccharides to Luminex microspheres. J Immunol Methods 309, 75–85, doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.11.019 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Boesch A. W. et al. Highly parallel characterization of IgG Fc binding interactions. MAbs 6, 915–927, doi: 10.4161/mabs.28808 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.UniProt C. UniProt: the Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res 51, D523–D531, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac1052 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lee J. et al. Molecular-level analysis of the serum antibody repertoire in young adults before and after seasonal influenza vaccination. Nat Med 22, 1456–1464, doi: 10.1038/nm.4224 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wickham H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag New York (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wickham H. A., M; Bryan J; Chang W; McGowan LD; François R; Grolemund G; Hayes A; Henry L; Hester J; Kuhn M; Pedersen TL; Miller E; Bache SM; Müller K; Ooms J; Robinson D; Seidel DP; Spinu V; Takahashi K; Vaughan D; Wilke C; Woo K; Yutan i H “Welcome to the tidyverse.”. Journal of Open Source Software, doi: 10.21105/joss.01686 (2019). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wickham H. F., R; Henry L; Müller K; Vaughan D. _dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation_. R package version 1.1.2, <https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr>. (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kassambara A. _ggpubr: ‘ggplot2’ Based Publication Ready Plots_. R package version 0.6.0,. (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gao C. H., Yu G. & Cai P. ggVennDiagram: An Intuitive, Easy-to-Use, and Highly Customizable R Package to Generate Venn Diagram. Front Genet 12, 706907, doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.706907 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw proteomic data has been deposited in MassIVE (https://massive.ucsd.edu/ProteoSAFe/static/massive.jsp). The raw data for measurement of immune responses from human subjects is available in the data files.