Abstract

Many estuaries experience eutrophication, deoxygenation and warming, with potential impacts on greenhouse gas emissions. However, the response of N2O production to these changes is poorly constrained. Here we applied nitrogen isotope tracer incubations to measure N2O production under experimentally manipulated changes in oxygen and temperature in the Chesapeake Bay—the largest estuary in the United States. N2O production more than doubled from nitrification and increased exponentially from denitrification when O2 was decreased from >20 to <5 micromolar. Raising temperature from 15° to 35°C increased N2O production 2- to 10-fold. Developing a biogeochemical model by incorporating these responses, N2O emissions from the Chesapeake Bay were estimated to decrease from 157 to 140 Mg N year−1 from 1986 to 2016 and further to 124 Mg N year−1 in 2050. Although deoxygenation and warming stimulate N2O production, the modeled decrease in N2O emissions, attributed to decreased nutrient inputs, indicates the importance of nutrient management in curbing greenhouse gas emissions, potentially mitigating climate change.

Nutrient reduction is effective to mitigate nitrous oxide emissions in a large estuary under deoxygenation and warming.

INTRODUCTION

Estuaries link the land and ocean environment, providing critical ecosystem functions and services such as the removal of excess nutrients and support for biodiversity and fisheries. However, estuaries are severely perturbed by anthropogenic activities (1–3). For example, excess nutrient inputs from agriculture and wastewater cause eutrophication, harmful algal blooms, and hypoxia (4, 5). During the transformation of nitrogenous (N) nutrients in estuaries, nitrous oxide (N2O), a powerful greenhouse gas and the dominant ozone depleting agent, is produced mainly via nitrification and denitrification (6–8). Estuaries are highly variable sources of N2O to the atmosphere. The estimated emissions range from less than 0.1 Tg N year−1 to over 5 Tg N year−1 (6, 9, 10), a potentially important contributor to global N2O emissions of ~17 Tg N year−1 (11). A better understanding of estuarine N2O cycling would help to constrain global N2O emission estimates.

Climate-driven changes such as deoxygenation and ocean acidification have been shown to affect N2O production in estuarine and coastal waters (12–14). Observations from aquatic sediments and terrestrial soils have suggested that N2O production is sensitive to temperature and precipitation (15–17). For example, increased N2O emissions from soil and river systems since the industrial revolution are attributed largely to warming and the rise in N loading (18–20). However, the effect of temperature and N loading on N2O production in estuaries is poorly understood. Because oxygen, temperature, and N loading have changed substantially in estuaries and are projected to change under predicted future climate (21–24), it is critical to assess the response of N2O production to these environmental drivers. Thereby, we can better evaluate the climate feedback of estuarine N2O emissions and design climate mitigation efforts.

The Chesapeake Bay, the largest estuary in the continental United States, experiences hypoxia or even anoxia in the central deep channel in summer (Fig. 1). Long-term physical and water-quality monitoring documented notable increases in the volume of hypoxic waters in early summer from 1949 to 2009 (25). In addition, temperature increased at a rate of 0.02° ± 0.02°C/year in the bay’s main stem between the late 1980s and late 2010s (26). Since 1985, nutrient management efforts have been implemented to reduce nutrient and sediment loads to the Chesapeake Bay (27), with the goal of reducing annual nitrogen loading to ~84 million kg over the Chesapeake Bay watershed (28). Nutrient reduction has been suggested to decrease both the duration and extent of hypoxia in the bay, although warming has partly offset these hypoxia improvements (29). Thus, the Chesapeake Bay is an ideal system to study N2O production in response to climate forcing (e.g., oxygen and temperature) and human perturbations (e.g., nutrient management). We used 15N-labeled N substrates to directly measure N2O production from nitrification and denitrification under manipulated oxygen and temperature conditions that simulate climate change. Building on the observed patterns from this study and previous measurements, we developed a N2O cycling module and implemented it in ROMS-ECB (Regional Ocean Modeling System for the Chesapeake Bay with Estuarine-Carbon-Biogeochemistry) (30–32) to estimate the historical and future changes in N2O emissions in the Chesapeake Bay. This study sets a benchmark for future field observations of N2O cycling and model development of N2O emissions in global estuaries under climate change.

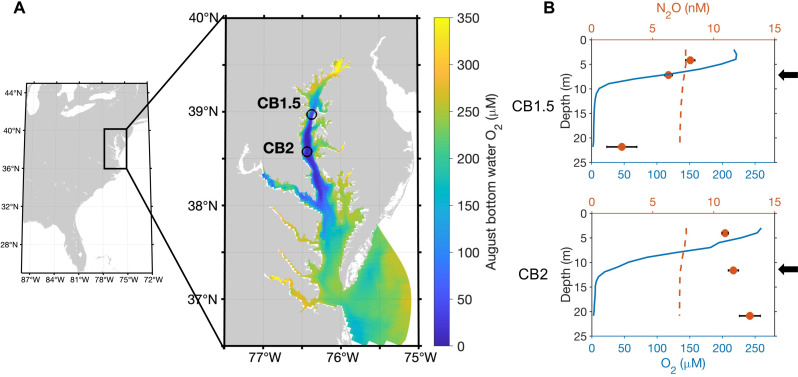

Fig. 1. Biogeochemical properties of the sampling stations.

(A) Two sampling locations overlaid on model-estimated August bottom water oxygen concentrations. (B) Observed vertical distributions of oxygen (blue lines) and N2O concentrations (red circles) and estimated N2O equilibrium concentrations with the atmosphere (dashed red line) in August 2021. Black arrows show the depths where incubation samples were collected.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The effect of deoxygenation on N2O production

Tracer incubations were conducted at oxyclines of two stations in the seasonally hypoxic region of the bay (Fig. 1A). Oxygen concentrations decreased sharply with depth at both stations, while N2O and N nutrient concentrations showed different vertical patterns between stations (Fig. 1B and fig. S1). The upstream station CB1.5 had a shallower oxycline and thicker anoxic layer starting at ~10 m, while the anoxic layer at CB2 started at ~13 m. CB1.5 had a higher dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) concentration than CB2. Ammonium was the most abundant DIN (4 to 11 μM) at CB1.5, while nitrite was the most abundant DIN (up to 4 μM) in the deep layer at CB2. Nitrate and urea were generally below 1 μM at all depths at both stations. N2O concentrations at CB1.5 decreased with depth and reached undersaturation in the bottom water, while N2O concentrations at CB2 increased with depth and were oversaturated compared to the atmospheric equilibrium concentration.

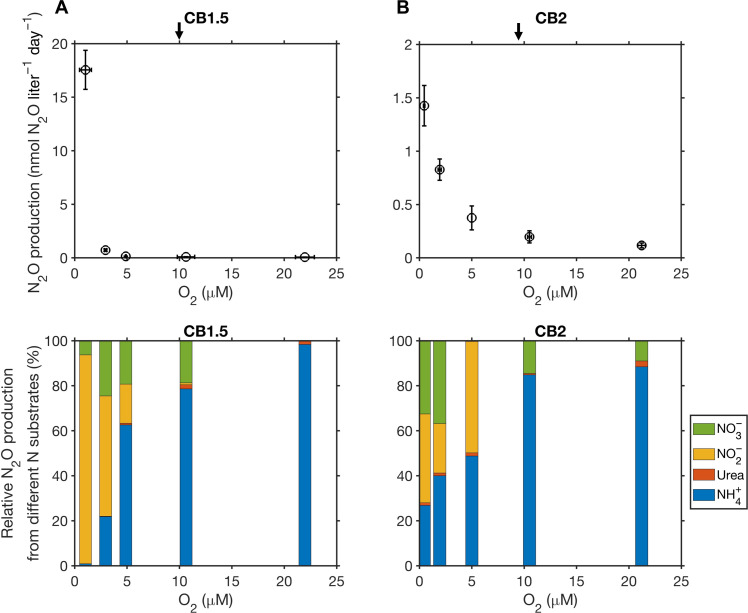

For both stations, total N2O production rates increased as we decreased oxygen concentrations (Fig. 2). N2O production from NH4+ was the major N2O-producing process above ~10 μM oxygen, which is consistent with a previous study measuring in situ N2O production across the ambient oxygen gradient in the same locations (13). N2O production from urea was roughly one to two orders of magnitude lower than from ammonia oxidation (fig. S2), indicating a small contribution of urea oxidation to nitrite production and associated N2O production in the bay. When oxygen was decreased from around 10 to 0.46 μM, N2O production from NH4+ and urea increased, except for urea at CB1.5 where large uncertainties obscured the pattern. For example, N2O production from NH4+ approximately doubled from 0.07 to 0.15 nmol N2O liter−1 day−1 at CB1.5 and increased from 0.16 to 0.33 nmol N2O liter−1 day−1 at CB2. These increases were driven by an increase in the N2O production yield (Fig. 3A) despite the decrease in ammonia oxidation rates (fig. S3) in response to lower oxygen concentrations. The substantial increase in the yield of N2O production with decreasing oxygen (increased from <0.05% to above 1% when oxygen decreased from the ambient concentration to below 1 μM) is comparable to previous studies on cultivated nitrifiers (33) and in environmental samples (34–36).

Fig. 2. Total N2O production from four N substrates and their relative contributions in response to the manipulated O2 changes.

Samples were collected at stations CB1.5 (A) and CB2 (B). Arrows on the top panels denote in situ oxygen concentrations at two stations. Vertical error bars represent the uncertainty of 15N-N2O production (SE of the regression slope) during the incubation time course. Horizontal error bars represent SDs of oxygen concentrations during the incubations. N2O production rates were small but significantly larger than 0 when oxygen concentrations were above 5 μM at station CB1.5 (A). SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error.

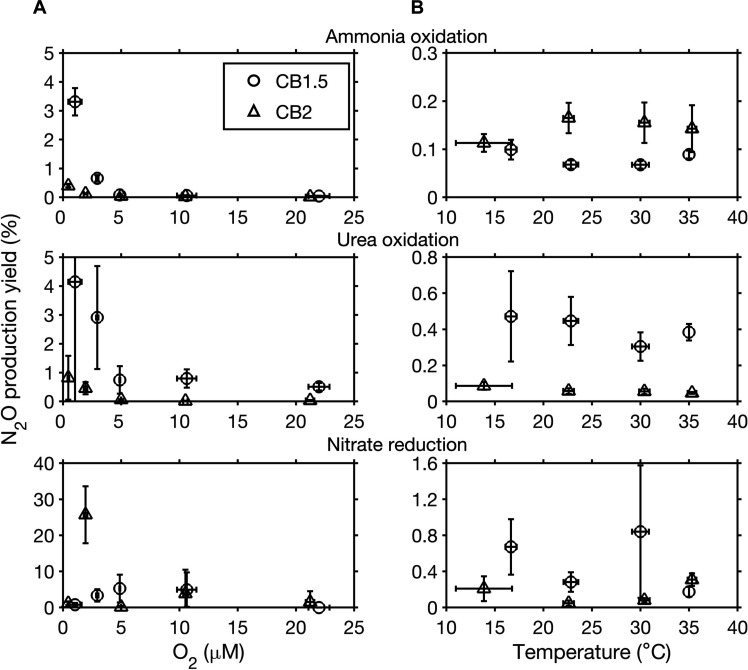

Fig. 3. N2O production yield in experimental manipulations.

N2O production yield from nitrification (ammonia oxidation, urea oxidation) and denitrification (nitrate reduction) in response to manipulated oxygen (A) and temperature (B) changes for samples collected at stations CB1.5 (circles) and CB2 (triangles). Vertical error bars represent the uncertainty of N2O production yield. Horizontal error bars represent SDs of oxygen concentrations or temperature during the incubations.

Combining data from previous oxygen manipulation experiments conducted in the Chesapeake Bay (13), we fitted a curve to the relationship between the yield of N2O production from NH4+ and O2 concentration following previous studies (37): yield (%) = 0.3889/O2 + 0.2197 (Fig. 3 and fig. S4). The fitted minimum yield (0.2197% versus 0.072 to 0.154%) was slightly higher than in studies conducted in the marine oxygen minimum zones (OMZs) (34–36). This difference may be related to differences in the ammonia-oxidizing assemblages between the bay and the OMZs (13, 38). Ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) and ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) were both found in the Chesapeake Bay and the dominance of one or other varied spatially (39). In contrast, AOA dominate in marine OMZs (38, 40). AOB generally have a higher N2O production yield than AOA under low oxygen conditions (33).

N2O production rates from nitrite and nitrate at ambient oxygen or above 10 μM were not statistically different from zero (fig. S2). Meanwhile, the rates of nitrate reduction to nitrite were also low (0.7 and 1.3 nmol N liter−1 day−1 at CB1.5 and CB2, respectively; fig. S3). However, when oxygen was reduced to less than 5 μM, N2O production from nitrite and nitrate increased substantially. For example, N2O production from nitrite increased by roughly 650-fold from 0.025 to 16.3 nmol N2O liter−1 day−1 while N2O production from nitrate increased by roughly 40-fold from 0.027 to 1.1 nmol N2O liter−1 day−1 when oxygen decreased from 10.6 to 1 μM at CB1.5 (Fig. 2A). Meanwhile, nitrate reduction to nitrite increased from 1 to 291 nmol N liter−1 day−1 (fig. S3). A large stimulation of N2O production from denitrification was also observed at CB2 (Fig. 2B). When fitting the response of N2O production from denitrification to oxygen using the equation , the values ranged from 1 to 2.5 μM O2, suggesting that denitrification-derived N2O production was highly sensitive to oxygen changes in the Chesapeake Bay. Overall, denitrification from nitrite and nitrate became the dominant N2O production pathway at <5 μM O2 (Fig. 2).

In contrast to the monotonically increasing N2O production yield from nitrification with decreasing oxygen, the N2O production yield from denitrification (Eq. 2) had an apparent optimal oxygen range between 2.5 and 10 μM where the yield was ~5% (Fig. 3A). One exception is the extremely high yield at 25.7% at 1.94 μM oxygen at CB2. Combining these data with measurements from a previous study (13), we fitted a Gaussian distribution curve to the N2O production yield from nitrate (fig. S4), which could potentially be used to model N2O production from denitrification. The estimated N2O production yield from nitrate in the Chesapeake Bay in our study is similar to what Ji et al. (35) found (<5%) but differs from the yield (20 to 90%) found in Frey et al. (41), both from studies in the eastern tropical Pacific OMZs. In addition, Bourbonnais et al. (42) found N2O production yield in the range of 0.38 to 0.68% based on the relationship between excess N2O and DIN deficit in the eastern Pacific Ocean. It may be that denitrifying communities adapted to the seasonally hypoxic the Chesapeake Bay differ from those in the permanent OMZs, which could partly explain the difference. For example, a microbial community dominated by complete denitrifiers (i.e., containing the full set of denitrification genes) may have a lower N2O production yield compared to a microbial community dominated by denitrifiers lacking nitrous oxide reductase genes (nosZ). However, the controlling factors on the highly variable yield from denitrification remain to be quantified.

The effect of warming on N2O production

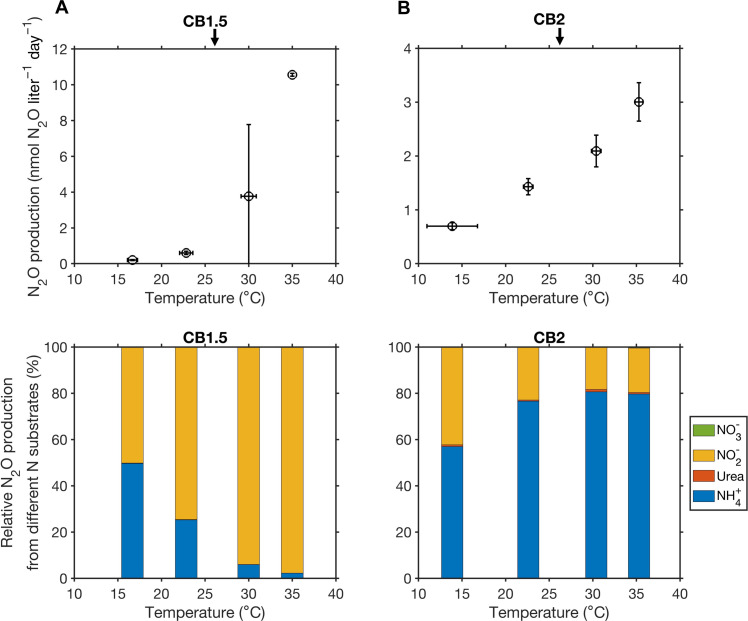

The response of N2O production to temperature has been investigated in soils and marine sediments (16, 43). Here, we provide the first direct observation of the response of water column N2O production to manipulated temperature changes. N2O production from the four N substrates all increased with warming (Fig. 4 and fig. S5). For instance, N2O production from NH4+ increased by ~6-fold from 0.4 to 2.4 nmol N2O liter−1 day−1 when temperature increased from 13.8° to 35.3°C at CB2. N2O production from nitrate increased by ~13-fold from 0.001 to 0.014 nmol N2O liter−1 day−1. N2O production was not inhibited by temperature even up to 35°C. AOB were found to be the dominant ammonia-oxidizing microbes in a part of the main stem of the Chesapeake Bay (13), while AOA outnumbered AOB near the mouth of the bay in earlier studies (39). AOB generally have a higher optimal temperature for growth and nitrification than AOA (44), which may explain the continuous increase in N2O production from nitrification up to 35°C. In addition, the observed increase in N2O production from denitrification with temperature was consistent with the high thermal tolerance of denitrification and N2O production found in coastal sediments (16). For example, the optimal temperature for denitrification was 36°C in subtropical sediments (45).

Fig. 4. Total N2O production from four N substrates and their relative contributions in response to the manipulated temperature changes.

Samples were collected at stations CB1.5 (A) and CB2 (B). Arrows on the top panels denote in situ temperature at two stations. Vertical error bars represent the uncertainty of 15N-N2O production (standard error of the regression slope) during the incubation time course. Horizontal error bars represent SDs of temperature during the incubations.

We derived the Q10 temperature coefficient, a measure of temperature sensitivity of biochemical processes (see the equation to estimate Q10 in Materials and Methods), to quantify the response of N2O-cycling processes to temperature changes. The Q10 temperature coefficient of N2O production from nitrification varied from 1.53 to 2.46 (table S1). However, no other studies of N2O production from nitrification in response to manipulated temperature are available to compare. The median Q10 value of 2.12 for denitrification N2O production (table S1) was within the range of Q10 found in sedimentary N2O production (16). One exception is the extremely high Q10 value, 9.22, of N2O production from nitrite at CB1.5. We suspect that this large increase in the N2O production rate may be related to a substantial oxygen drop in this incubation time course, thus triggering N2O production from denitrification. The concurrently monitored oxygen consumption in separate bottles was ~0.15 μM O2/hour, leading to a ~1.2 μM O2 decrease after an 8-hour incubation. However, there may have been some heterogeneities in the oxygen consumption among incubations, e.g., due to the difference in particulate organic matter concentrations in each bottle or presence of zooplankton. Therefore, warming can disproportionally affect denitrification because of the simultaneous change in oxygen concentrations (i.e., higher oxygen consumption and lower oxygen solubility with rising temperature) (46).

Rates of N2O-producing pathways all showed a similar exponential increase with temperature except a decrease in ammonia oxidation rate at 35°C and a drop of nitrate reduction rate at 30°C at CB1.5 (fig. S6). The Q10 values of denitrification (2.85 to 3.2) are slightly higher than the Q10 values of nitrification (1.51 to 2.43), indicating a stronger response of denitrification than nitrification to temperature (P < 0.05). In contrast to a substantial increase in absolute N2O production rate with warming (Fig. 4), the yields of N2O production from different pathways were variable but did not show a clear pattern (Fig. 3B). For example, N2O production yield from NH4+ fluctuated between 0.06 and 0.1% at CB1.5. Therefore, the increase in N2O production in response to warming was mainly driven by the increase in nitrification and denitrification processes, rather than a change in yield. Although the Chesapeake Bay experiences a large variation in temperature over a seasonal cycle (roughly 2° to 28°C), the temperature shifts that we used in short-term manipulation experiments cannot reflect long-term adaptation of microbial community or succession in microbial community. Future molecular analyses of microbial community composition and gene expression patterns associated with N2O production pathways may help to resolve the mechanism of the response of N2O production to temperature.

Estuarine N2O emissions in response to warming and changes in nutrient loading

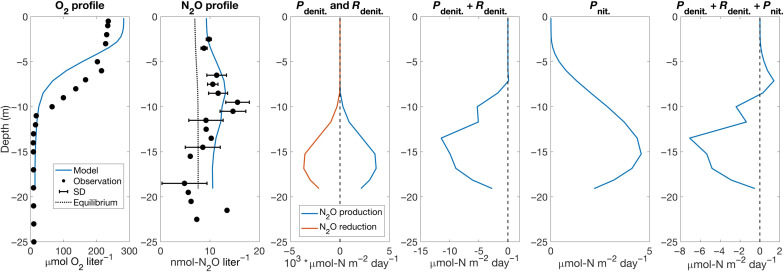

Our experimental design (i.e., short-term manipulation) does not permit long-term predictions about sustained responses to global change, but the observed responses illustrate that microbial processes of N2O production are sensitive to both oxygen and temperature. Building on the results from oxygen and temperature manipulation experiments, we developed and embedded an N2O cycling module into a three-dimensional (3D) estuarine model, ROMS-ECB, to evaluate N2O cycling and emissions under warming and changes in nutrient loading in the bay (Materials and Methods). The modeling results extended our view of the spatial and temporal distribution of N2O in the Chesapeake Bay, which has only been observed in summer and fall with a limited number of stations. Modeled surface N2O concentrations captured the spatial variation in observed N2O concentrations (fig. S7): higher concentrations in the upper and middle bay than the lower bay (13, 47, 48). N2O concentrations accumulated to above 25 nM in regions where oxygen concentrations were below 100 μM (e.g., in May in fig. S7). When oxygen concentrations decreased below approximately 20 μM in summer bottom water in the middle bay, N2O reduction exceeded N2O production by denitrification, leading to undersaturated N2O concentrations (figs. S7 and S8). During summer hypoxia, denitrification produced a large amount of N2O in low oxygen waters and further reduced N2O to N2, suggesting an intensive internal N2O cycling (Fig. 5). The simulated vertical subsurface peak in N2O concentrations at the lower oxycline also matched field observations at station CB2, which could be explained by the vertical distributions of N2O production and reduction (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Depth profiles of observed summer oxygen concentrations, N2O concentrations, modeled summer N2O concentrations and N2O cycling processes at station CB2.

N2O concentrations observed in this study and extracted from previous studies (12, 13, 47) were binned into 1-m vertical intervals to compare with model results. N2O equilibrium concentrations with the atmosphere calculated from the solubility are shown in the dotted black line. SD: SD of observed N2O concentrations within 1-m vertical intervals. Pdenit: N2O production by denitrification. Rdenit: N2O reduction by denitrification. Pnit: N2O production by nitrification.

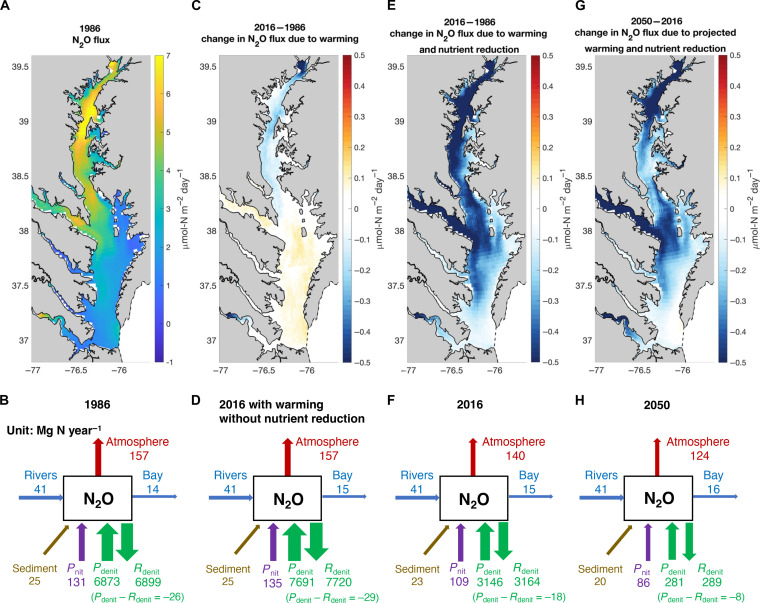

Overall, the Chesapeake Bay was a net source of N2O into the atmosphere with a strong seasonality (fig. S9), emitting ~157 Mg N year−1 in 1986 (Fig. 6, A and B). The modeled N2O fluxes to the atmosphere generally were consistent with the range of observed N2O fluxes to the atmosphere varying from −0.3 to 4.3 μmol N2O m−2 day−1 spatially (13, 47). The highest N2O flux to the atmosphere at around 7 μmol N2O m−2 day−1 appeared in the middle bay where summer hypoxia occurred. Nitrification (131 Mg N year−1) was the dominant process contributing to N2O emissions (Fig. 6B). While the production and consumption of N2O by denitrification were the largest fluxes in the model, denitrification in the water column was a net sink of N2O (−26 Mg N year−1). In comparison, sediments emitted 25 Mg N year−1 of N2O into the bottom waters, which was on the same magnitude of net N2O reduction by denitrification in the water column (Fig. 6B). Rivers supplied 41 Mg N year−1 of N2O into the bay area and 14 Mg N year−1 of N2O was exported to the coastal Atlantic Ocean.

Fig. 6. Model-predicted N2O emissions in the Chesapeake Bay under warming and changes in nutrient loading.

(A) Map of N2O emission into the atmosphere and (B) budget of N2O cycling (unit: Mg N year−1) in 1986. (C) Changes in N2O emission and (D) budget of N2O cycling in 2016 due to historical warming and atmospheric N2O increase and without nutrient reduction. (E) Changes in N2O emission and (F) budget of N2O cycling in 2016 under historical warming, atmospheric N2O increase, and nutrient reduction. (G) Changes in N2O emission and (H) budget of N2O cycling in 2050 under future projected warming, atmospheric N2O increase from RCP8.5 emission scenario, and meeting the mandated the Chesapeake Bay TMDL nutrient reduction goal (28).

Under simulated historical warming from 1986 to 2016, oxygen concentrations decreased (fig. S10). N2O production from nitrification increased by 4 Mg N year−1 due to warming and deoxygenation. Meanwhile, net N2O reduction from water column denitrification increased by 3 Mg N year−1: a larger increase in N2O reduction than N2O production from denitrification (Fig. 6D). The change in riverine N2O input into the Chesapeake Bay was smaller compared to other N2O-cycling fluxes. The transport of N2O into the Atlantic Ocean increased by 1 Mg N year−1 partly due to the increased N2O equilibrium concentration in response to the increased atmospheric N2O concentration. Overall, total N2O emissions into the atmosphere did not change substantially, with N2O emissions decreasing in the upper bay while increasing in the lower bay (Fig. 6, C and D). However, if atmospheric N2O concentrations were held constant from 1986 to 2016, N2O emissions would have increased by 3 Mg N year−1 under warming and deoxygenation (fig. S11).

Nutrient reduction effort implemented in the Chesapeake Bay between 1986 and 2016 has been suggested to partly offset the impact of climate change on the area and volume of hypoxia (29). N2O emissions decreased to 140 Mg N year−1 in 2016 with a reduction in N2O flux across almost the entire bay area largely due to the lower N2O production from nitrification, which decreased from 131 to 109 Mg N year−1 (Fig. 6, E and F). Meanwhile, sedimentary N2O production decreased by 2 Mg N year−1. An increase in oxygen concentrations (fig. S10) instead reduced the N2O consumption by water column denitrification (Fig. 6F). Future N2O emissions are projected to further decrease to 124 Mg N year−1 in 2050 because of continued efforts to reduce N input into the Chesapeake Bay via the mandated the Chesapeake Bay total maximum daily load (TMDL) (28), which would further reduce N2O production from nitrification and sedimentary N2O flux (Fig. 6, G and H). Our model simulation highlights the cobenefit of nutrient reduction in improving water quality and curbing N2O emissions, guiding the management strategy in other aquatic systems and policy decisions to reduce nitrogen loading and mitigate greenhouse gas emissions.

Implications

Our model results indicate that recent policy efforts to reduce nutrient loading have had the added effect of reducing N2O emissions despite warming and deoxygenation. Model projections of future N2O emissions in the Chesapeake Bay could aid in the understanding and prediction of N2O emissions in other estuarine and coastal waters. For example, similar to the Chesapeake Bay, eutrophication and deoxygenation have degraded the Baltic Sea’s ecosystem for decades (49). The ongoing decline in nutrient loading into the Baltic Sea should improve the environmental and ecological conditions (50) and possibly reduce N2O emissions. However, deoxygenation and warming are projected to expand in many other estuaries globally (21, 22), in turn likely stimulating estuarine N2O production. In addition, nutrient inputs are not declining in all estuaries, for example, the upper Gulf of Thailand and the Pearl River Estuary are expected to receive increasing nutrient inputs due to the continued population growth, development of agriculture, industrialization, and urbanization (51). These estuaries are characterized by some of the highest N2O concentrations and fluxes to the atmosphere in aquatic environments across the globe (52, 53). Our model results suggest that their N2O emissions will likely continue to increase if N loading is not reduced. Our study highlights that reducing nitrogen loading is effective to decrease N2O emissions even under warming.

Here, we examined the effects of temperature, oxygen, and nutrient input on estuarine N2O emissions. However, particle loading, pH, and many other factors are simultaneously changing in the estuarine and coastal environments (54, 55). Future work should consider these additional factors to better constrain the overall climate and anthropogenic impact on N2O emissions, as well as their subsequent feedback on climate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection and analysis

Two stations, CB1.5 and CB2 (both around 24 m deep), in the middle-deep channel of the Chesapeake Bay mainstem were selected for sampling during August 2021 when a sharp oxygen gradient in the water column and low oxygen bottom water developed (Fig. 1). The locations of CB1.5 and CB2 are close to the Chesapeake Bay Program long-term monitoring stations CB3.3C and CB4.3C, respectively. Water was collected from a rosette system equipped with 12 12-liter Niskin bottles and with a conductivity-temperature-depth profiler (Sea-Bird Scientific) to record temperature, pressure, salinity, and in situ O2 concentrations. N2O concentration samples were collected from Niskin bottles into 60-ml serum bottles after overflowing three times the bottle’s volume. The serum bottles were immediately sealed with butyl stoppers and aluminum crimps and preserved with 100 μl of saturated HgCl2 solution. After returning to the laboratory on land, N2O in the serum bottles was stripped with helium (He) gas into a gas chromatography–isotope ratio mass spectrometer (GC-IRMS; Delta V Plus, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for N2O concentration and isotope ratio (mass/charge ratio = 44, 45, 46) measurements (13). The total amount of N2O in the serum bottles was determined by comparing the peak area with N2O standards containing a known amount of N2O reference gas (0, 0.207, 0.415, 0.623, 0.831, and 1.247 nmol N2O). The N2O concentration in samples was calculated from the amount of N2O detected by mass spectrometry divided by the volume of water in the serum bottles. The detection limit and precision of N2O concentration measurements were 1.29 and 0.33 nM, respectively.

Nutrient samples were collected into 50-ml Falcon tubes and kept frozen at −20°C until analysis on land. Concentrations of ammonium (NH4+), nitrite (NO2−), and urea were measured using the fluorometric orthophthalaldehyde method (56), the colorimetric method (57), and the diacetyl monoxime method (58), respectively. Nitrite + nitrate (NO2− + NO3−) concentration was measured using the vanadium (III) reduction method by converting NO2− + NO3− to NO, which was quantified by chemiluminescence analyzer (59). NO3− concentration was then determined by the difference between the concentration of NO2− + NO3− and NO2−. The detection limits were 0.1 μM for NH4+, 0.02 μM for NO2−, 0.1 μM for urea, and 0.15 μM for NO3−.

N2O incubation experiments: Oxygen and temperature manipulation

Two sets of tracer incubation experiments modified from previous protocols (13, 60) were conducted to investigate the effect of oxygen and temperature on the rates of N2O production and associated reactions (i.e., nitrification and denitrification) by experimentally manipulating the oxygen concentration and temperature respectively. We collected water samples at the oxycline depth at both stations for incubations because these waters are likely to experience fluctuating oxygen and temperature levels (see biogeochemical features of the incubation waters in table S2). Water was collected into 60-ml serum bottles as described above. The microbial communities at the oxycline may be different from the surface oxic and bottom anoxic waters (61). However, the oxycline waters may contain microbes from both surface and bottom waters due to vertical mixing. In addition, sediments may also be important sources of N2O production but were not directly measured here. Future work should include tracer incubations at different depths and in sediments.

To manipulate the oxygen concentration, a 4-ml headspace was created in the serum bottles with high-purity He gas. Then, the bottles were purged with different He/O2 mixtures for 15 min to obtain O2 concentrations targeted at 0, 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 μM. The actual oxygen concentration in each set of incubations was measured using an oxygen sensor (PyroScience, Aachen, Germany) (table S3). After adjusting the oxygen concentration, 15NH4Cl, 15N-urea, Na15NO2, and Na15NO3 tracers (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, final tracer concentration of 2 μM) were separately injected into six serum bottles at each oxygen level for a time course incubation of each 15N tracer at 0, 4, and 8 hours with duplicate bottles at each time point. Because increases in substrate concentrations due to tracer additions affect nitrogen cycling rates (62, 63), the measured rates were potential rates not in situ rates. The purpose of adding a high tracer concentration was to ensure that N2O production was not limited by the substrate but was regulated by the oxygen concentration. Natural abundance 44N2O (100 μl of 1000 parts per million or ~4.15 nmol of N2O) was added as a background carrier to trap the produced 15N-labeled N2O and to ensure a sufficient mass for isotope analysis later. Similarly, 2 μM Na14NO2 was added if the ambient NO2− concentration was below 1 μM. The incubation bottles were placed in a temperature-controlled dark container to mimic the in situ light and temperature conditions (~26°C).

Temperature manipulation experiments were performed at the initial ambient oxygen concentration. After adding 15N-tracers, 44N2O and Na14NO2 as in the oxygen manipulation experiments described above, incubation bottles were placed in temperature-controlled dark containers with temperatures set to 15°, 23°, 30°, and 35°C. The temperature inside each incubator was continuously monitored by a thermometer, and the actual temperatures are shown in table S4. For both oxygen and temperature manipulation experiments, duplicate samples were preserved with 100 μl of saturated HgCl2 solution at approximately 0, 4, and 8 hours after the tracer addition. All the preserved samples were stored in the cold room in the dark until analysis in the laboratory on land.

Analysis of N2O incubation samples

The N2O concentrations and nitrogen isotopes from the incubation experiments were measured on a GC-IRMS as described above following previously published protocols (13, 34, 41). N2O production rates (including 44N2O, 45N2O, and 46N2O) were calculated by linear regressions of the progressive increase in mass 45 and 46 N2O over the course of the incubation (64). Some of the N2O production pathways are not fully resolved (7), such that certain 15N tracer additions may involve multiple N2O production pathways. For example, 15NO2− tracer may be involved in denitrifier denitrification, nitrifier denitrification and hybrid N2O formation by AOA. In addition, there may be an overlap in N2O production rates measured by 15NO2− and 15NO3− because both substrates can be used in denitrification under low oxygen conditions. Therefore, summing N2O production from 15NO2− and 15NO3− together may overestimate the total N2O production from denitrification. Previous studies have found that the ratio of ambient concentrations of NO2− and NO3− is important in determining the rate of their reduction to N2O (12). However, the exact mechanism driving the difference in N2O production measured by 15NO2− and 15NO3− remains to be resolved but is beyond the scope of this study.

The nitrite production rate was measured from the oxidation of ammonia (15NH4+) or urea (15N-urea) and the reduction of nitrate (15NO3−) as described previously (38). Briefly, after incubation, samples were analyzed for N2O production, an aliquot was transferred from the serum bottle to a 20-ml glass vial (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) to obtain 20 nmol of N based on the measured concentration of nitrite. After purging with He for 10 min to remove any contamination of N2O during the sample transfer, the transferred nitrite sample was converted to N2O using acetic acid–treated sodium azide solution (65). The resulting N2O concentration and N isotope ratio were then measured on the GC-IRMS.

The nitrite production rates from ammonia or urea oxidation and nitrate reduction were determined as below (38)

| (1) |

where represents the concentration change over the course of incubation () and represents the fraction of 15N in the initial substrate pool (NH4+, N-urea, or NO3−). The yield of N2O production can be estimated by comparing the N2O production rate with the rate of processes that produce N2O (e.g., nitrification and nitrate reduction). We defined the yield in Eq. 2 for each nitrite-producing process

| (2) |

Because we did not measure N2 production, our defined N2O production yield from nitrate reduction is different from the traditional definition of N2O yield from denitrification, which is . This N2O production yield (relative to N2 production) in inland waters has a large variation with a median at 1%, lower quartile at 0.2% and upper quartile at 4.1% (66).

The Q10 temperature coefficient is a measure of temperature sensitivity of biochemical processes, defined as , where R is the rate and T is the temperature. We estimated Q10 for the measured rates of nitrification, nitrate reduction to nitrite, and N2O production from nitrification and denitrification (table S1).

Modeling N2O cycling in the Chesapeake Bay

The 3D estuarine model used in this study is an implementation of the Regional Ocean Modeling System [ROMS (32)] for the Chesapeake Bay. The model domain is discretized by an orthogonal curvilinear grid with varying horizontal resolution of 430 m to 2 km inside the bay and 20 terrain-following vertical levels (67). The model is coupled every time step (i.e., 1 min) to a biogeochemical module [Estuarine Carbon Biogeochemistry (ECB)] representing the carbon and nitrogen cycles, air-sea exchange, and biogeochemical fluxes at the seabed. Equations and parameterizations of all 17 ECB state variables are documented in (30). The resulting configuration is referred to as ROMS-ECB, which has been evaluated extensively with physical and biogeochemical observations in previous studies on the Chesapeake Bay sediment, oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon dynamics (29, 31, 68–71).

In this study, we developed and embedded a new N2O cycling module to the existing 3D estuarine model for the Chesapeake Bay. A new state variable, N2O, was parameterized to include water column N2O production from nitrification (), N2O production and reduction from water column denitrification ( and , respectively), N2O flux from sediments due to coupled nitrification-denitrification (), advection (), diffusion (), and N2O exchange at the air-sea interface ()

| (3) |

The equations for each N2O term are documented in tables S5 to S7. is defined as the nitrification rate multiplied by the yield of N2O production, which is a function of oxygen concentrations (table S6). is derived from the water column denitrification term in the model, representing the reduction of nitrate to N2O. This process depends on temperature and nitrate and oxygen concentrations. Specifically, we applied a new limitation function for denitrification () that decreases exponentially with oxygen concentrations (table S6), diverging from the original ROMS-ECB where it was an inverse function of oxygen. We introduced a new term, , to account for N2O reduction to N2. The rate of N2O reduction increases exponentially with water temperature and is limited exponentially by oxygen concentrations (72). The production of N2O in estuarine sediment () is parameterized as 0.1% of the N loss via coupled nitrification–denitrification in the sediment (see discussion about sedimentary N2O production and its yield in Supplementary Text). Last, is parameterized as a function of surface N2O concentration, wind speed, Schmidt number for N2O in seawater (73), N2O solubility in seawater (74), and atmospheric N2O concentrations. This N2O model is evaluated with 291 field observations of N2O concentrations compiled from previous studies (12, 13, 47) and this study (Supplementary Materials).

Realistic atmospheric, terrestrial, and oceanic forcings were prescribed to ROMS-ECB. Atmospheric forcing for the model was derived from the three-hourly European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts Reanalysis v5 (ERA5) product with a horizontal resolution of 0.25° (75), including winds, downward long-wave radiation, net short-wave radiation, precipitation, dewpoint temperature, air temperature, and pressure. Atmospheric nitrogen deposition was prescribed as in Da et al. (69). For the period 2015 to present, terrestrial forcings were prescribed as follows: (i) Riverine freshwater transport was scaled on the basis of US Geological Survey (USGS) data (76); (ii) riverine biogeochemical variables—including nitrate, ammonium, and dissolved and particulate organic nitrogen/carbon—were specified as daily climatological concentrations from the years 2010–2014 using the Dynamic Land Ecosystem Model (76, 77); (iii) riverine temperature was set according to the daily climatology of the years 2010–2014 from the Chesapeake Bay Program Watershed Model (78); (iv) Riverine oxygen concentrations were assumed to be at saturation and computed from the prescribed temperature; (v) Riverine N2O concentrations were established at 1.5 times the N2O solubility based on the measurements of N2O concentration in the Potomac River (79). At the continental shelf boundary, monthly climatologies of temperature and salinity were assumed to be representative of year 2013 and supplemented by long-term linear trends (31). Oxygen and N2O concentrations at the shelf boundary were computed at saturation from the prescribed temperature and salinity following Weiss and Price (74).

One reference, two past sensitivity experiments, and one future sensitivity experiment were conducted in this study (table S8). The reference run (Ref) was conducted for the year 2016, which represents a normal streamflow flow year based on USGS freshwater discharge data. Three sensitivity experiments were compared to the reference run to quantify the relative impacts of climate change and river nutrient inputs on N2O cycling in the Chesapeake Bay (table S8). These sensitivity experiments retained the same model forcings as in Ref, except that one of the following combinations was modified: (i) decreased atmospheric N2O concentrations, decreased atmospheric temperature, and increased riverine nitrate and organic nitrogen concentrations to 1986 (Test1986); (ii) decreased atmospheric N2O concentrations and increased riverine nitrate and organic nitrogen concentrations to 1986 (Test1986warming); and (iii) increased atmospheric N2O concentrations, increased atmospheric temperature, and decreased riverine nitrate and organic nitrogen concentrations to 2050 (Test2050). The details of these model experiments are described below. For all the model simulations, vertical integrals of N2O budgets were calculated for each model grid cell and time step. The results were then averaged over a year to obtain annual mean budgets presented in this study.

The model forcings prescribed for the past (Test1986 and Test1986warming) sensitivity experiments were generated on the basis of long-term trends in historical observations. Specifically, three changes were introduced in the sensitivity experiment Test1986 compared to the reference simulation Ref. First, the annual mean atmospheric N2O record from 1986 was used to estimate a 24 parts per billion (ppb) decrease in N2O concentrations relative to 2016 (329.33 ppb) (80). While the ERA5 atmospheric temperature has been generally increasing between 1986 and 2016 (approximately 0.7°C per 30 years based on linear regression), substantially greater warming has occurred during the warmer months of the year (26). To represent the conditions of 1986 in the sensitivity experiment Test1986, we subtracted seasonally varying 30-year changes from the atmospheric temperature in the reference run, resulting in a cooler atmospheric temperature. Last, we applied seasonally varying 30-year changes in riverine nitrate and organic nitrogen concentrations to the two largest tributaries of the bay, namely, the Susquehanna and Potomac Rivers, based on USGS data products [refer to (31) for details]. The nitrate and organic nitrogen concentrations in the Susquehanna River were, on average, 20 and 12 mmol m−3 higher, respectively, in 1986 (Test1986) compared to 2016 (Ref). The annual total nitrogen loading was around 129.3 million kg in 1986 and 117.8 million kg in 2016. Throughout all three sensitivity experiments, freshwater discharge remained consistent with the reference simulation (Ref). As a result, the sensitivity experiment Test1986 represents the conditions that would have prevailed in 1986 without perturbations from interannual variability. In the case of the sensitivity experiment Test1986warming, only riverine nitrate and organic nitrogen concentrations were modified, mirroring Test1986, while all other model forcings remained identical to Ref. This allowed us to isolate the impact of nutrient management efforts on N2O cycling from the effects of climate change (e.g., temperature changes) using model results from Test1986warming.

For the future sensitivity experiment Test2050, we obtained projections under a high emission scenario [Representative Concentration Pathways 8.5 (RCP 8.5)] from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP5) Earth System Model (ESM) IPSL-CM5B-LR. RCP 8.5 seems to be the most likely scenario based on the historical changes and current trajectory of climate change (e.g., cumulative CO2 emissions) by 2050 (81). We calculated the monthly climatology of the rate of change in atmospheric temperature per year based on the downscaled ESM products (71), assuming constant atmospheric temperature increases through time (no acceleration). Although many ESMs could be used, in this study, IPSL-CM5B-LR was chosen because it represents the median estimate of atmospheric temperature change over the Chesapeake Bay watershed across a group of 20 ESMs [see (71) for more details]. The spatial averages of these changes range from 0.035° to 0.055°C per year over the Chesapeake Bay region. In addition, atmospheric N2O concentrations in 2050 under the RCP 8.5 emission scenario from (82) were used in Test2050 (367 ppb). Compared with the reference run for 2016, the future sensitivity experiment for 2050 assumed a 28.4% decrease in riverine nitrate, ammonium, and organic nitrogen concentrations. Our assumption is grounded in the idea that nutrient management efforts in the Chesapeake Bay—the TMDL—will be fully implemented by 2050, reducing annual nitrogen loading to 84.3 million kg over the Chesapeake Bay watershed (28). The choice of the mid-21st century timeframe is based on the consideration that it provides sufficient time for nutrient reductions into the future while being close enough to enable reasonably constrained estimates of the potential impacts of future climate change.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the crew of the R/V Hugh Sharp for assistance during the Chesapeake Bay cruise in August 2021.

Funding: This research is supported by NSF grant OCE-1657663 and OCE-1946516 to B.B.W. The model simulations are conducted using William & Mary’s High Performance Computing facilities, which are supported by the National Science Foundation, the Commonwealth of Virginia Equipment Trust Fund, and the Office of Naval Research. W.T. is also supported by the startup fund from the University of South Florida.

Author contributions: Conceptualization: W.T. Investigation-field observations: W.T., J.C.T., N.I., M.A.K., J.A.L., X.S.W., A.J., and B.B.W. Investigation-modeling: W.T., F.D., and M.A.M.F. Formal analysis: W.T. and F.D. Visualization: W.T. and F.D. Supervision: B.B.W. Writing—original draft: W.T. Writing—review and editing: W.T., F.D., J.C.T., N.I., M.A.K., J.A.L., X.S.W., A.J., M.A.M.F., and B.B.W.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Data presented in this study have been deposited into Zenodo repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13732662 and https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13958745).

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S14

Tables S1 to S9

References

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Barbier E. B., Hacker S. D., Kennedy C., Koch E. W., Stier A. C., Silliman B. R., The value of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services. Ecol. Monogr. 81, 169–193 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Courrat A., Lobry J., Nicolas D., Laffargue P., Amara R., Lepage M., Girardin M., Le Pape O., Anthropogenic disturbance on nursery function of estuarine areas for marine species. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 81, 179–190 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Statham P. J., Nutrients in estuaries--an overview and the potential impacts of climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 434, 213–227 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kemp W. M., Boynton W. R., Adolf J. E., Boesch D. F., Boicourt W. C., Brush G., Cornwell J. C., Fisher T. R., Glibert P. M., Hagy J. D., Harding L. W., Houde E. D., Kimmel D. G., Miller W. D., Newell R. I. E., Roman M. R., Smith E. M., Stevenson J. C., Eutrophication of Chesapeake Bay: Historical trends and ecological interactions. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 303, 1–29 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paerl H. W., Valdes L. M., Peierls B. L., Adolf J. E., Harding L. J. W., Anthropogenic and climatic influences on the eutrophication of large estuarine ecosystems. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51, 448–462 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray R. H., Erler D. V., Eyre B. D., Nitrous oxide fluxes in estuarine environments: response to global change. Glob. Chang. Biol. 21, 3219–3245 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stein L. Y., Insights into the physiology of ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 49, 9–15 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Bie M. J. M., Middelburg J. J., Starink M., Laanbroek H. J., Factors controlling nitrous oxide at the microbial community and estuarine scale. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 240, 1–9 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosentreter J. A., Laruelle G. G., Bange H. W., Bianchi T. S., Busecke J. J. M., Cai W.-J., Eyre B. D., Forbrich I., Kwon E. Y., Maavara T., Moosdorf N., Najjar R. G., Sarma V. V. S. S., Van Dam B., Regnier P., Coastal vegetation and estuaries are collectively a greenhouse gas sink. Nat. Clim. Chang. 13, 579–587 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bange H. W., Rapsomanikis S., Andreae M. O., Nitrous oxide in coastal waters. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 10, 197–207 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tian H., Xu R., Canadell J. G., Thompson R. L., Winiwarter W., Suntharalingam P., Davidson E. A., Ciais P., Jackson R. B., Janssens-Maenhout G., Prather M. J., Regnier P., Pan N., Pan S., Peters G. P., Shi H., Tubiello F. N., Zaehle S., Zhou F., Arneth A., Battaglia G., Berthet S., Bopp L., Bouwman A. F., Buitenhuis E. T., Chang J., Chipperfield M. P., Dangal S. R. S., Dlugokencky E., Elkins J. W., Eyre B. D., Fu B., Hall B., Ito A., Joos F., Krummel P. B., Landolfi A., Laruelle G. G., Lauerwald R., Li W., Lienert S., Maavara T., MacLeod M., Millet D. B., Olin S., Patra P. K., Prinn R. G., Raymond P. A., Ruiz D. J., van der Werf G. R., Vuichard N., Wang J., Weiss R. F., Wells K. C., Wilson C., Yang J., Yao Y., A comprehensive quantification of global nitrous oxide sources and sinks. Nature 586, 248–256 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ji Q., Frey C., Sun X., Jackson M., Lee Y.-S., Jayakumar A., Cornwell J. C., Ward B. B., Nitrogen and oxygen availabilities control water column nitrous oxide production during seasonal anoxia in the Chesapeake Bay. Biogeosciences 15, 6127–6138 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang W., Tracey J. C., Carroll J., Wallace E., Lee J. A., Nathan L., Sun X., Jayakumar A., Ward B. B., Nitrous oxide production in the Chesapeake Bay. Limnol. Oceanogr. 67, 2101–2116 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou J., Zheng Y., Hou L., An Z., Chen F., Liu B., Wu L., Qi L., Dong H., Han P., Yin G., Liang X., Yang Y., Li X., Gao D., Li Y., Liu Z., Bellerby R., Liu M., Effects of acidification on nitrification and associated nitrous oxide emission in estuarine and coastal waters. Nat. Commun. 14, 1380 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris E., Diaz-Pines E., Stoll E., Schloter M., Schulz S., Duffner C., Li K., Moore K. L., Ingrisch J., Reinthaler D., Zechmeister-Boltenstern S., Glatzel S., Brüggemann N., Bahn M., Denitrifying pathways dominate nitrous oxide emissions from managed grassland during drought and rewetting. Sci. Adv. 7, eabb7118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan E., Zou W., Zheng Z., Yan X., Du M., Hsu T.-C., Tian L., Middelburg J. J., Trull T. W., Kao S.-J., Warming stimulates sediment denitrification at the expense of anaerobic ammonium oxidation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 349–355 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li S., Yue A., Moore S. S., Ye F., Wu J., Hong Y., Wang Y., Temperature-related N2O emission and emission potential of freshwater sediment. Processes 10, 2728 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yao Y., Tian H., Shi H., Pan S., Xu R., Pan N., Canadell J. G., Increased global nitrous oxide emissions from streams and rivers in the Anthropocene. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 138–142 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tian H., Yang J., Xu R., Lu C., Canadell J. G., Davidson E. A., Jackson R. B., Arneth A., Chang J., Ciais P., Gerber S., Ito A., Joos F., Lienert S., Messina P., Olin S., Pan S., Peng C., Saikawa E., Thompson R. L., Vuichard N., Winiwarter W., Zaehle S., Zhang B., Global soil nitrous oxide emissions since the preindustrial era estimated by an ensemble of terrestrial biosphere models: Magnitude, attribution, and uncertainty. Glob. Chang. Biol. 25, 640–659 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griffis T. J., Chen Z., Baker J. M., Wood J. D., Millet D. B., Lee X., Venterea R. T., Turner P. A., Nitrous oxide emissions are enhanced in a warmer and wetter world. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 12081–12085 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breitburg D., Levin L. A., Oschlies A., Grégoire M., Chavez F. P., Conley D. J., Garçon V., Gilbert D., Gutiérrez D., Isensee K., Jacinto G. S., Limburg K. E., Montes I., Naqvi S. W. A., Pitcher G. C., Rabalais N. N., Roman M. R., Rose K. A., Seibel B. A., Telszewski M., Yasuhara M., Zhang J., Declining oxygen in the global ocean and coastal waters. Science 359, eaam7240 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varela R., de Castro M., Dias J. M., Gomez-Gesteira M., Coastal warming under climate change: Global, faster and heterogeneous. Sci. Total Environ. 886, 164029 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lima F. P., Wethey D. S., Three decades of high-resolution coastal sea surface temperatures reveal more than warming. Nat. Commun. 3, 704 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seitzinger S. P., Mayorga E., Bouwman A. F., Kroeze C., Beusen A. H. W., Billen G., Van Drecht G., Dumont E., Fekete B. M., Garnier J., Harrison J. A., Global river nutrient export: A scenario analysis of past and future trends. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 24, 2009GB003587 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy R. R., Kemp W. M., Ball W. P., Long-term trends in chesapeake bay seasonal hypoxia, stratification, and nutrient loading. Estuaries Coasts 34, 1293–1309 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hinson K. E., Friedrichs M. A. M., St-Laurent P., Da F., Najjar R. G., Extent and causes of chesapeake bay warming. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 58, 805–825 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Q., Blomquist J. D., Fanelli R. M., Keisman J. L. D., Moyer D. L., Langland M. J., Progress in reducing nutrient and sediment loads to Chesapeake Bay: Three decades of monitoring data and implications for restoring complex ecosystems. WIREs Water 10, e1671 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 28.USEPA, Chesapeake Bay total maximum daily load for nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment (USEPA, 2010).

- 29.Frankel L. T., Friedrichs M. A. M., St-Laurent P., Bever A. J., Lipcius R. N., Bhatt G., Shenk G. W., Nitrogen reductions have decreased hypoxia in the Chesapeake Bay: Evidence from empirical and numerical modeling. Sci. Total Environ. 814, 152722 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.St-Laurent P., Friedrichs M. A. M., Najjar R. G., Shadwick E. H., Tian H., Yao Y., Relative impacts of global changes and regional watershed changes on the inorganic carbon balance of the Chesapeake Bay. Biogeosciences 17, 3779–3796 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Da F., Friedrichs M. A. M., St-Laurent P., Shadwick E. H., Najjar R. G., Hinson K. E., Mechanisms driving decadal changes in the carbonate system of a coastal plain estuary. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 126, e2021JC017239 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shchepetkin A. F., McWilliams J. C., The regional oceanic modeling system (ROMS): A split-explicit, free-surface, topography-following-coordinate oceanic model. Ocean Model 9, 347–404 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hink L., Lycus P., Gubry-Rangin C., Frostegard A., Nicol G. W., Prosser J. I., Bakken L. R., Kinetics of NH3-oxidation, NO-turnover, N2O-production and electron flow during oxygen depletion in model bacterial and archaeal ammonia oxidisers. Environ. Microbiol. 19, 4882–4896 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ji Q., Babbin A. R., Jayakumar A., Oleynik S., Ward B. B., Nitrous oxide production by nitrification and denitrification in the Eastern Tropical South Pacific oxygen minimum zone. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 10755–10764 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ji Q., Buitenhuis E., Suntharalingam P., Sarmiento J. L., Ward B. B., Global nitrous oxide production determined by oxygen sensitivity of nitrification and denitrification. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 32, 1790–1802 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santoro A. E., Buchwald C., Knapp A. N., Berelson W. M., Capone D. G., Casciotti K. L., Nitrification and nitrous oxide production in the offshore waters of the eastern tropical south pacific. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 35, e2020GB006716 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nevison C., Butler J. H., Elkins J. W., Global distribution of N2O and the ΔN2O-AOU yield in the subsurface ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 17, 2003GB002068 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng X., Fuchsman C. A., Jayakumar A., Oleynik S., Martens-Habbena W., Devol A. H., Ward B. B., Ammonia and nitrite oxidation in the Eastern Tropical North Pacific. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 29, 2034–2049 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bouskill N. J., Eveillard D., Chien D., Jayakumar A., Ward B. B., Environmental factors determining ammonia-oxidizing organism distribution and diversity in marine environments. Environ. Microbiol. 14, 714–729 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Michael Beman J., Popp B. N., Alford S. E., Quantification of ammonia oxidation rates and ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria at high resolution in the Gulf of California and eastern tropical North Pacific Ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 57, 711–726 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frey C., Bange H. W., Achterberg E. P., Jayakumar A., Löscher C. R., Arévalo-Martínez D. L., León-Palmero E., Sun M., Sun X., Xie R. C., Oleynik S., Ward B. B., Regulation of nitrous oxide production in low-oxygen waters off the coast of Peru. Biogeosciences 17, 2263–2287 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bourbonnais A., Chang B. X., Sonnerup R. E., Doney S. C., Altabet M. A., Marine N2O cycling from high spatial resolution concentration, stable isotopic and isotopomer measurements along a meridional transect in the eastern Pacific Ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1137064 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y., Wang J., Dai S., Sun Y., Chen J., Cai Z., Zhang J., Müller C., Temperature effects on N2O production pathways in temperate forest soils. Sci. Total Environ. 691, 1127–1136 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng Z.-Z., Zheng L.-W., Xu M. N., Tan E., Hutchins D. A., Deng W., Zhang Y., Shi D., Dai M., Kao S.-J., Substrate regulation leads to differential responses of microbial ammonia-oxidizing communities to ocean warming. Nat. Commun. 11, 3511 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Canion A., Kostka J. E., Gihring T. M., Huettel M., van Beusekom J. E. E., Gao H., Lavik G., Kuypers M. M. M., Temperature response of denitrification and anammox reveals the adaptation of microbial communities to in situ temperatures in permeable marine sediments that span 50° in latitude. Biogeosciences 11, 309–320 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Veraart A. J., de Klein J. J., Scheffer M., Warming can boost denitrification disproportionately due to altered oxygen dynamics. PLOS ONE 6, e18508 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laperriere S. M., Nidzieko N. J., Fox R. J., Fisher A. W., Santoro A. E., Observations of variable ammonia oxidation and nitrous oxide flux in a eutrophic estuary. Estuaries Coasts 42, 33–44 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCarthy J. J., Kaplan W., Nevins J. L., Chesapeake Bay nutrient and plankton dynamics. 2. Sources and sinks of nitrite1. Limnol. Oceanogr. 29, 84–98 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Conley D. J., Carstensen J., Aigars J., Axe P., Bonsdorff E., Eremina T., Haahti B. M., Humborg C., Jonsson P., Kotta J., Lannegren C., Larsson U., Maximov A., Medina M. R., Lysiak-Pastuszak E., Remeikaite-Nikiene N., Walve J., Wilhelms S., Zillen L., Hypoxia is increasing in the coastal zone of the Baltic Sea. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 6777–6783 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saraiva S., Markus Meier H. E., Andersson H., Höglund A., Dieterich C., Gröger M., Hordoir R., Eilola K., Baltic Sea ecosystem response to various nutrient load scenarios in present and future climates. Clim. Dyn. 52, 3369–3387 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dai M., Zhao Y., Chai F., Chen M., Chen N., Chen Y., Cheng D., Gan J., Guan D., Hong Y., Huang J., Lee Y., Leung K. M. Y., Lim P. E., Lin S., Lin X., Liu X., Liu Z., Luo Y.-W., Meng F., Sangmanee C., Shen Y., Uthaipan K., Wan Talaat W. I. A., Wan X. S., Wang C., Wang D., Wang G., Wang S., Wang Y., Wang Y., Wang Z., Wang Z., Xu Y., Yang J.-Y. T., Yang Y., Yasuhara M., Yu D., Yu J., Yu L., Zhang Z., Zhang Z., Persistent eutrophication and hypoxia in the coastal ocean. Camb. Prism. Coast. Futures 1, e19 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin H., Dai M., Kao S.-J., Wang L., Roberts E., Yang J.-Y. T., Huang T., He B., Spatiotemporal variability of nitrous oxide in a large eutrophic estuarine system: The pearl river estuary China. Mar. Chem. 182, 14–24 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wan X. S., Sheng H. X., Liu L., Shen H., Tang W., Zou W., Xu M. N., Zheng Z., Tan E., Chen M., Zhang Y., Ward B. B., Kao S. J., Particle-associated denitrification is the primary source of N2O in oxic coastal waters. Nat. Commun. 14, 8280 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Syvitski J., Ángel J. R., Saito Y., Overeem I., Vörösmarty C. J., Wang H., Olago D., Earth’s sediment cycle during the Anthropocene. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 179–196 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Doney S. C., Busch D. S., Cooley S. R., Kroeker K. J., The impacts of ocean acidification on marine ecosystems and reliant human communities. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 45, 83–112 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Holmes R. M., Aminot A., Kérouel R., Hooker B. A., Peterson B. J., A simple and precise method for measuring ammonium in marine and freshwater ecosystems. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 56, 1801–1808 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 57.H. P. Hansen, F. Koroleff, "Determination of nutrients" in Methods of Seawater Analysis (WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH, 1999), pp. 159–228.

- 58.Chen L., Ma J., Huang Y., Dai M., Li X., Optimization of a colorimetric method to determine trace urea in seawater. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 13, 303–311 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Braman R. S., Hendrix S. A., Nanogram nitrite and nitrate determination in environmental and biological materials by vanadium(III) reduction with chemiluminescence detection. Anal. Chem. 61, 2715–2718 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bourbonnais A., Frey C., Sun X., Bristow L. A., Jayakumar A., Ostrom N. E., Casciotti K. L., Ward B. B., Protocols for assessing transformation rates of nitrous oxide in the water column. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 611937 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cram J. A., Hollins A., McCarty A. J., Martinez G., Cui M., Gomes M. L., Fuchsman C. A., Microbial diversity and abundance vary along salinity, oxygen, and particle size gradients in the Chesapeake Bay. Environ. Microbiol. 26, e16557 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tang W., Fortin S. G., Intrator N., Lee J. A., Kunes M. A., Jayakumar A., Ward B. B., Determination of site-specific nitrogen cycle reaction kinetics allows accurate simulation of in situ nitrogen transformation rates in a large North American estuary. Limnol. Oceanogr. 69, 1757–1768 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Michiels C. C., Huggins J. A., Giesbrecht K. E., Spence J. S., Simister R. L., Varela D. E., Hallam S. J., Crowe S. A., Rates and pathways of N2 production in a persistently anoxic Fjord: Saanich Inlet British Columbia. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 27 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Trimmer M., Chronopoulou P.-M., Maanoja S. T., Upstill-Goddard R. C., Kitidis V., Purdy K. J., Nitrous oxide as a function of oxygen and archaeal gene abundance in the North Pacific. Nat. Commun. 7, 13451 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McIlvin M. R., Altabet M. A., Chemical conversion of nitrate and nitrite to nitrous oxide for nitrogen and oxygen isotopic analysis in freshwater and seawater. Anal. Chem. 77, 5589–5595 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang J., Vilmin L., Mogollon J. M., Beusen A. H. W., van Hoek W. J., Liu X., Pika P. A., Middelburg J. J., Bouwman A. F., Inland waters increasingly produce and emit nitrous oxide. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 13506–13519 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Feng Y., Friedrichs M. A. M., Wilkin J., Tian H., Yang Q., Hofmann E. E., Wiggert J. D., Hood R. R., Chesapeake Bay nitrogen fluxes derived from a land-estuarine ocean biogeochemical modeling system: Model description, evaluation, and nitrogen budgets. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 120, 1666–1695 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Irby I. D., Friedrichs M. A. M., Da F., Hinson K. E., The competing impacts of climate change and nutrient reductions on dissolved oxygen in Chesapeake Bay. Biogeosciences 15, 2649–2668 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Da F., Friedrichs M. A. M., St-Laurent P., Impacts of atmospheric nitrogen deposition and coastal nitrogen fluxes on oxygen concentrations in Chesapeake Bay. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 123, 5004–5025 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Turner J. S., St-Laurent P., Friedrichs M. A. M., Friedrichs C. T., Effects of reduced shoreline erosion on Chesapeake Bay water clarity. Sci. Total Environ. 769, 145157 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hinson K. E., Friedrichs M. A. M., Najjar R. G., Herrmann M., Bian Z., Bhatt G., St-Laurent P., Tian H., Shenk G., Impacts and uncertainties of climate-induced changes in watershed inputs on estuarine hypoxia. Biogeosciences 20, 1937–1961 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tang W., Jayakumar A., Sun X., Tracey J. C., Carroll J., Wallace E., Lee J. A., Nathan L., Ward B., Nitrous oxide consumption in oxygenated and anoxic estuarine waters. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100657 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wanninkhof R., Relationship between wind speed and gas exchange over the ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 97, 7373–7382 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weiss R. F., Price B. A., Nitrous oxide solubility in water and seawater. Mar. Chem. 8, 347–359 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hersbach H., Bell B., Berrisford P., Hirahara S., Horányi A., Muñoz-Sabater J., Nicolas J., Peubey C., Radu R., Schepers D., Simmons A., Soci C., Abdalla S., Abellan X., Balsamo G., Bechtold P., Biavati G., Bidlot J., Bonavita M., De Chiara G., Dahlgren P., Dee D., Diamantakis M., Dragani R., Flemming J., Forbes R., Fuentes M., Geer A., Haimberger L., Healy S., Hogan R. J., Hólm E., Janisková M., Keeley S., Laloyaux P., Lopez P., Lupu C., Radnoti G., de Rosnay P., Rozum I., Vamborg F., Villaume S., Thépaut J. N., The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bever A. J., Friedrichs M. A. M., St-Laurent P., Real-time environmental forecasts of the Chesapeake Bay: Model setup, improvements, and online visualization. Environ. Model. Softw. 140, 105036 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tian H., Yang Q., Najjar R. G., Ren W., Friedrichs M. A. M., Hopkinson C. S., Pan S., Anthropogenic and climatic influences on carbon fluxes from eastern North America to the Atlantic Ocean: A process-based modeling study. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 120, 757–772 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 78.CBP, Online draft documentation for Phase 6 modeling tools (2017).

- 79.Tang W., Talbott J., Jones T., Ward B. B., Variable contribution of wastewater treatment plant effluents to downstream nitrous oxide concentrations and emissions. Biogeosciences 21, 3239–3250 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Freing A., Wallace D. W. R., Tanhua T., Walter S., Bange H. W., North Atlantic production of nitrous oxide in the context of changing atmospheric levels. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 23, 2009GB003472 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schwalm C. R., Glendon S., Duffy P. B., RCP8.5 tracks cumulative CO2 emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 19656–19657 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Riahi K., Rao S., Krey V., Cho C., Chirkov V., Fischer G., Kindermann G., Nakicenovic N., Rafaj P., RCP 8.5—A scenario of comparatively high greenhouse gas emissions. Clim. Change 109, 33–57 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tan E., Hsu T. C., Zou W., Yan X., Huang Z., Chen B., Chang Y., Zheng Z., Zheng L., Xu M., Tian L., Kao S. J., Quantitatively deciphering the roles of sediment nitrogen removal in environmental and climatic feedbacks in two subtropical estuaries. Water Res. 224, 119121 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Foster S. Q., Fulweiler R. W., Sediment nitrous oxide fluxes are dominated by uptake in a temperate estuary. Front. Mar. Sci. 3, 40 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 85.Beaulieu J. J., Tank J. L., Hamilton S. K., Wollheim W. M., Hall R. O. Jr., Mulholland P. J., Peterson B. J., Ashkenas L. R., Cooper L. W., Dahm C. N., Dodds W. K., Grimm N. B., Johnson S. L., McDowell W. H., Poole G. C., Valett H. M., Arango C. P., Bernot M. J., Burgin A. J., Crenshaw C. L., Helton A. M., Johnson L. T., O’Brien J. M., Potter J. D., Sheibley R. W., Sobota D. J., Thomas S. M., Nitrous oxide emission from denitrification in stream and river networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 214–219 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Seitzinger S. P., Denitrification in freshwater and coastal marine ecosystems: Ecological and geochemical significance. Limnol. Oceanogr. 33, 702–724 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 87.Murphy R. R., Keisman J., Harcum J., Karrh R. R., Lane M., Perry E. S., Zhang Q., Nutrient improvements in Chesapeake Bay: Direct effect of load reductions and implications for coastal management. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 260–270 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Oviatt C., Smith L., Krumholz J., Coupland C., Stoffel H., Keller A., McManus M. C., Reed L., Managed nutrient reduction impacts on nutrient concentrations, water clarity, primary production, and hypoxia in a north temperate estuary. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 199, 25–34 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 89.McElroy M. B., Elkins J. W., Wofsy S. C., Kolb C. E., Durán A. P., Kaplan W. A., Production and release of N2O from the Potomac Estuary 1. Limnol. Oceanogr. 23, 1168–1182 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bianchi D., McCoy D., Yang S., Formulation, optimization, and sensitivity of NitrOMZv1.0, a biogeochemical model of the nitrogen cycle in oceanic oxygen minimum zones. Geosci. Model Dev. 16, 3581–3609 (2023). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S14

Tables S1 to S9

References