Abstract

The covalently attached cofactor biotin plays pivotal roles in central metabolism. The top-priority ESKAPE-type pathogens, Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae, constitute a public health challenge of global concern. Despite the fact that the late step of biotin synthesis is a validated anti-ESKAPE drug target, the primary stage remains fragmentarily understood. We report the functional definition of two BioC isoenzymes (AbBioC for A. baumannii and KpBioC for K. pneumoniae) that act as malonyl-ACP methyltransferase and initiate biotin synthesis. The physiological requirement of biotin is diverse within ESKAPE pathogens. CRISPR-Cas9–based inactivation of bioC rendered A. baumannii and K. pneumoniae biotin auxotrophic. The availability of soluble AbBioC enabled the in vitro reconstitution of DTB/biotin synthesis. We solved two crystal structures of AbBioC bound to SAM cofactor (2.54 angstroms) and sinefungin (SIN) inhibitor (1.72 angstroms). Structural and functional study provided molecular basis for SIN inhibition of BioC. We demonstrated that BioC methyltransferase plays dual roles in K. pneumoniae infection and A. baumannii colistin resistance.

Bacterial BioC methyltransferase has multifaceted roles in biotin nutritional immunity, representing an attractive drug target.

INTRODUCTION

The water-soluble vitamin B7, biotin, is an indispensable micronutrient throughout the three domains of life (1). Unlike plants and most of bacterial species that program biotin synthesis pathways (1), humans cannot make this coenzyme. In general, gut commensals behave as a major group of biotin suppliers for mammalian biotin-dependent carboxylases/decarboxylases (2, 3). Granted that its dietary supplement benefits the notorious inflammatory bowel disease (4), the manipulation of biotin constitutes a promising option to ameliorate the kind of metabolic disorders caused by inherited biotin deficiency.

The de novo synthesis of an organic sulfur-containing biotin cofactor consists of a primary step and a late stage. The long-settled late segment proceeds via four conserved enzymes BioF/A/D/B to assemble the fused heterocyclic rings of biotin. A variety of early steps is committed to generate pimeloyl moiety as a fatty acid–like “arm” of biotin (i.e., an α,ω-dicarboxylic acid with seven carbons). Notably, the primary stage varies distinctly in diverse bacterial lineages. So far, no less than three routes have been assigned to pimelate production, namely, (i) a prototypical “BioC-BioH” strategy (5–7), (ii) the “BioI-BioW” machinery (8–10), and (iii) a noncanonical BioZ pathway (11, 12). The prevalent BioC-BioH form exploits a type II fatty acid synthesis (FAS II) to elongate a temporarily disguised primer of methyl malonate, giving the methyl-pimeloyl moiety product (5–7). In contrast to BioH esterase removing methyl moiety from methyl-pimelate, BioC methyltransferase introduces a methyl disguise to produce a surrogate methyl-malonate. In Bacillus subtilis, the P450 enzyme BioI oxidatively cleaves long-chain fatty acyl-ACP esters to give pimeloyl-ACP, a cognate biotin precursor (10), and then BioW ligase converts pimelic acid to pimeloyl–coenzyme A (CoA) ester (8, 9), an alternative substrate for BioF (8-amino-7-oxononanoate synthase) (13). As an atypical β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase III (FabH)-like enzyme, α-proteobacterial BioZ condenses a malonyl–acyl carrier protein (Mal-ACP) with a glutaryl-CoA donated from lysine degradation, producing pimeloyl-ACP, a cognate precursor for biotin synthesis (11, 12). The growing arsenal of BioH isoenzymes largely extends our understanding of complexity in the paradigm BioC-BioH early step (14), whereas the remaining cousin BioC appears as a conundrum in that it is biochemically unamenable and lacks structural insights (7, 15). Structure and catalysis of the recalcitrant BioC enzyme represent the last piece of “golden fleece” in structural biology of bacterial biotin synthesis.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a devastating “one health” threat (16). Of around 5 million AMR-related deaths worldwide, ~1.27 million is attributable to AMR in 2019 (17). The AMR dissemination stimulates the World Health Organization to recognize top priority “ESKAPE” pathogens (18), which namely include (i) Enterococcus faecalis, (ii) S. aureus, (iii) K. pneumoniae, (iv) A. baumannii, (v) Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and (vi) Enterobacter species. Moreover, biotin deficiency–causing intestinal dysbiosis engenders the dynamic role of ESKAPE-type microbes in the transition from microbiota compositions to opportunistic agents (19, 20). To tackle the ESKAPE-causing crisis, it is required to develop certain pathogen-specific, narrow-spectrum antimicrobials with unique drug targets. The maintenance of bacterial biotin homeostasis is postulated to be the case. This is because mycobacterial biotin synthesis and its biotinylation is a validated druggable antituberculosis (anti-TB) pathway (21, 22). Recently, Carfrae and colleagues (23) reported that targeting the late stage of biotin synthesis impairs pathogenicity of two ESKAPE members (K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii) during mice infection mimicking human environment. Similarly, virulence attenuation was seen for an additional ESKAPE agent, P. aeruginosa, upon the removal of BioH, a gatekeeper of biotin synthesis (24). However, the primary step of biotin generation in K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii awaits experimental demonstration. Because it is the coenzyme for AccB, a core component of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) complex that initiates FAS II pathway (25), biotin determines cell envelope lipid remodeling that is implicated in successful lung infections with Mycobacterium abscessus (26). Central to biotin, FAS II route was recently found to be required for bacterial insusceptibility to colistin, a “last-resort” defense against AMR-producing superbugs (27). Collectively, we favored that the “100-year-old” vitamin biotin is a multifaceted player.

Here, we proposed that a BioC-BioH paradigm is shared by the two distantly related ESKAPE microbes, A. baumannii and K. pneumoniae. Using SUMO fusion expression strategy, our continued efforts allowed the success in obtaining the soluble form of the recalcitrant BioC enzyme. Apart from the genetic and biochemical definition, we presented two high-resolution x-ray structures of A. baumannii BioC (AbBioC) bound to S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM) cofactor (2.54 Å) and sinefungin (SIN) inhibitor (1.72 Å). Because it functions as a pivotal player in the primary step of biotin synthesis, we explored clinical roles of BioC in K. pneumoniae infection and A. baumannii colistin resistance. In summary, this work solves a “long-standing” puzzle in structural exploration of bacterial biotin synthesis (1) and underlines BioC as a potential anti-ESKAPE drug target.

RESULTS

Genetic organization of ESKAPE biotin synthesis

Most of current knowledge on the early step of biotin synthesis arises from studies with the Gram-negative Escherichia and Gram-positive Bacillus (1). Unlike the paradigm Escherichia coli that relies on BioC-BioH pair to make biotin precursor, B. subtilis exploits a distinct pimeloyl-CoA BioW to compensate the genetic loss of bioC-bioH, whereas its relative Bacillus cereus retains the canonical BioC-BioH route because it contains a bifunctional type II biotin protein ligase (BirA) (BC1537)–regulated operon of bioADFHCB (fig. S1). The component of gut microbiota community, E. faecalis, seemed to be the only biotin auxotrophic member of ESKAPE microbes, and this is because only a locus of bioY (encoding biotin transporter) rather than a bio cluster that is encoded on its chromosome (fig. S1). Similar to B. subtilis that is characterized by a bioWAFDBI operon, S. aureus also adopts BioW machinery for biotin production, except with a different arrangement of bioDABFWX. It was noted that the small membrane protein BioX is assumed to be involved in biotin metabolism but awaits functional assignment (fig. S1). As for the E. coli bioC-bioH pair, bioC is integrated into the bioBFCD operon adjacent to bioA, whereas bioH is free-standing (fig. S1). An identical genetic context was noticed in K. pneumoniae, an opportunistic ESKAPE pathogen with an origin of intestinal microbiota (fig. S1). Similar scenarios were observed for the other two Enterobacter species, Enterobacter cloacae, and Enterobacter aerogenes (fig. S1). In particular, P. aeruginosa is an unusual ESKAPE pathogen in which a complete pathway of biotin synthesis is domesticated into a single “bioA/BFHCD” cluster (24, 28). Except for bioB that is scattered on chromosome, a similar operon “bioHAFCD” appears in A. baumannii (fig. S1). The arrangement (bioA/BFHCD and bioHAFCD) is postulated to confer physiological advantage in assuring parallel expression of BioH and BioC, two important players for biotin precursor pimeloyl-ACP generation (28). Thus, genetic organization for biotin primary step varies markedly among ESKAPE-type pathogens (Fig. 1A and fig. S1).

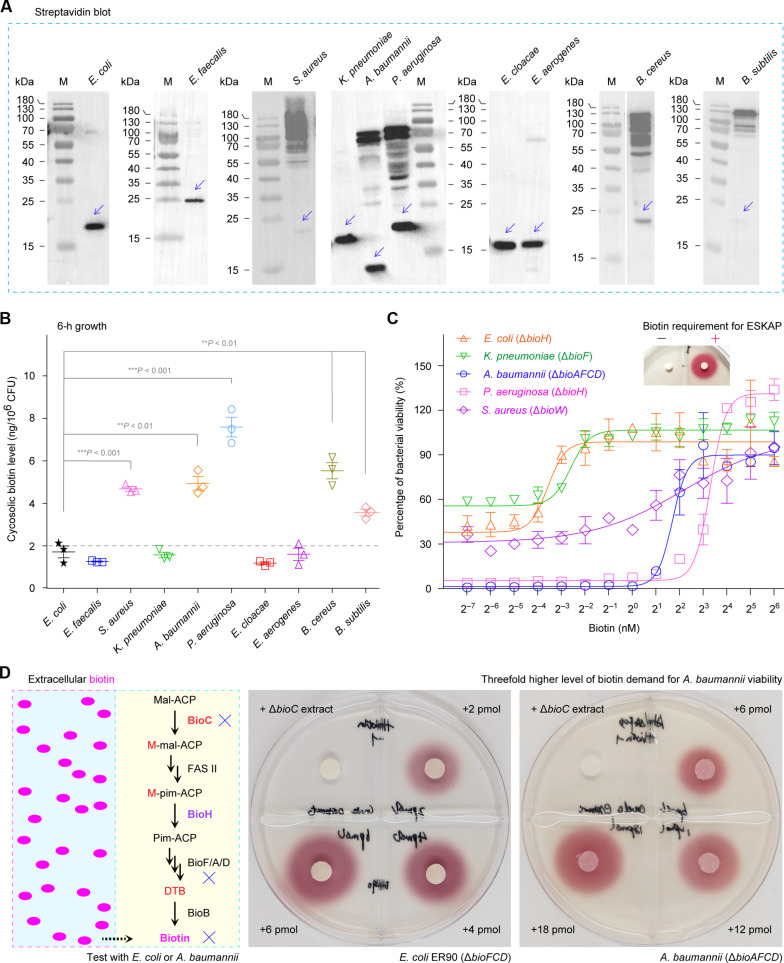

Fig. 1. Physiological requirement of biotin in ESKAPE-including microbes.

(A) Diversity in protein biotinylation of ESKAPE microbes. To detect biotin modification, Western blot was performed with crude extracts of diverse ESKAPE species, in which anti-streptavidin primary antibody was included. A representative photograph from three biological replicates was displayed. The biotinylated forms of BCCP (biotin carboxy carrier protein; AccB) were highlighted with blue arrows. (B) Varied level of cytosolic biotin in ESKAPE microbes. Data were presented as an average ± SD of three independent experiments. This was assayed by two-tailed analysis of variance (B). (C) Determination of biotin demand in certain ESKAPE-type pathogens. On the basis of the nonlinear regression model provided by GraphPad Prism, bacterial viability curves were plotted here, of which each data point is given as means ± SD (n = 3). Four biotin auxotrophic microbes were tested here, namely, E. coli (ΔbioH), K. pneumoniae (ΔbioF), A. baumannii (ΔbioAFCD), and P. aeruginosa (ΔbioH). The inside graph of biotin bioassay represents the viability of the biotin auxotroph ER90 (ΔbioF/C/D) engendered by the addition of exogenous biotin. The symbols of minus (−) and plus (+) denotes the absence or presence of 4-pmol biotin. (D) Biotin bioassays suggested that the supply of exogenous biotin at around a threefold higher level render A. baumannii viable at the comparable level to that of E. coli. The magenta oval dots on the left hand of (D) denote a pool of biotin molecules. Of three independent DTB/biotin bioassays, a representative result was given here. M, protein standards; BioH, methyl-pimeloyl ACP ester demethylase; BioC, Mal-ACP O-methyltransferase; BioD, dethiobiotin synthetase. h, hour.

Diverse demands for biotin by ESKAPE

In total, 10 diverse microbes including ESKAPE were systematically analyzed to seek for the alteration on physiological demand of biotin. Apart from the profile of biotinylated protein (Fig. 1A), cytosolic biotin level was measured (Fig. 1B), as well as the minimum biotin requirement for bacterial viability (Fig. 1C). In terms of streptavidin blotting, all the 10 species were roughly divided into two groups (Fig. 1A). Unlike a single AccB protein that is biotinylated in the five species (E. coli, E. faecalis, K. pneumoniae, E. cloacae, and E. aerogenes), biotin modification of multiple proteins were found in the remaining five species (S. aureus, A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa, B. cereus, and B. subtilis). The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) measurement unveiled that (i) five bacterial species with a single AccB biotinylated (such as E. coli and E. faecalis) consistently contain a pool of intracellular biotin at a comparable level of almost 2 ng/106 colony-forming units (CFU) and (ii) the other five species characterized by multiple protein biotinylation (e.g., S. aureus and A. baumannii) display the relatively high level (4 to 8 ng/106 CFU) of cytosolic biotin (Fig. 1B). Apart from an assignment to biotin transporters having altered activities, a varied level of cytosolic biotin in diverse ESKAPE microbes largely accounts for the distinct profile of protein biotinylation among different species (Fig. 1, A and B). In addition, this observation is correlated with the fact that the minimal requirement of biotin in E. coli and K. pneumoniae is substantially less than those in A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus (Fig. 1C). Biotin bioassays also validated that the minimal demand of biotin is around threefold higher in A. baumannii compared to E. coli (Fig. 1D).

Next, we focused on the recalcitrant ESKAPE member, A. baumannii, and performed in silico search for potential biotin-requiring proteins. As a result, seven candidates were returned (fig. S2A), which invariantly feature a biotinylated lysine (K) residue at the conserved motif EAMK (i.e., four continuous residues: glutamate, alanine, methione, and lysine) (fig. S2B). Consistent with the bioinformatic analysis, multiple proteins are biotinylated (rather than one single AccB band) in our assay of streptavidin blot (fig. S2, C and D). To verify this observation, four of seven candidates [HKO16_10520 (AccB), HKO16_06425, HKO16_06925, and HKO16_15815] were selected for further analyses. All the four recombinant forms (AccB and HKO16_06425 in full length and HKO16_06925 plus HKO16_15815 in an EAMK-covering truncated version) were overexpressed and purified to homogeneity (fig. S2E). Furthermore, streptavidin blot demonstrated that they are indeed biotin-modified forms (fig. S2F), which is quite similar to those of the plant causative agent, Agrobacterium tumefaciens (29), and the human pathogen surrogate, Mycobacterium smegmatis (30, 31). This constitutes an explanation for the relatively high biotin requirement by A. baumannii (Fig. 1, B and C), highlighting the complexity in biotin demand by diverse ESKAPE pathogens.

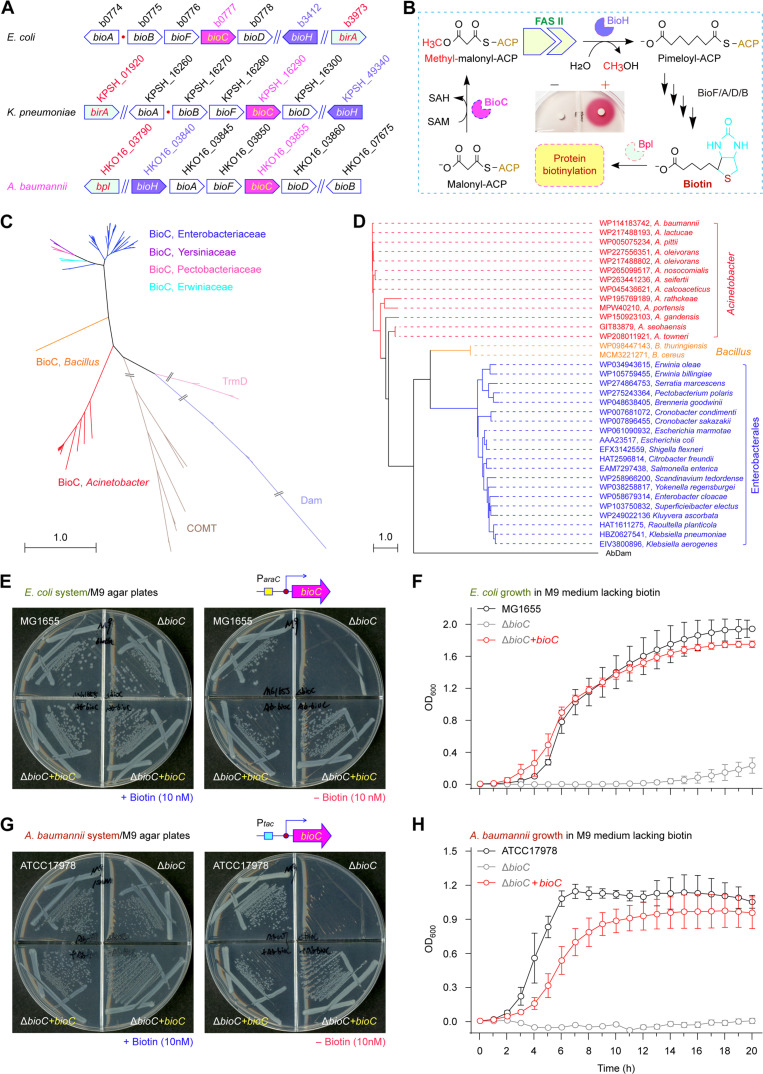

Genetic definition of two bioC homologs

The prior study led by Cronan’s laboratory implicated that E. coli BioC (EcBioC) functions as an initiator for the prototypic BioC-BioH primary pathway of biotin synthesis (Fig. 2, A and B) and is genetically replaced by the distantly related paralog of B. cereus (BcBioC) with only 26.94% identity (fig. S3) (5, 32). Phylogeny of BioC suggested its origin of methyltransferase (Fig. 2, C and D). Different from K. pneumoniae that arranges bioH (KPSH_49340) isolated from bioC (KPSH_16290), A. baumannii recruits bioH (HKO16_03840) into the same “bioHAFCD” operon as bioC (HKO16_03860) does (Fig. 2A). In addition, KpBioC seems alike EcBioC rather than BcBioC (63.75% versus 25.71% identity), whereas AbBioC requires several gaps for the alignment with both EcBioC and BcBioC (25 to 26.61% identity; fig. S3). To evaluate in vivo roles of distinct bioC homologs, we combined two genetic approaches, namely, (i) functional complementation of the E. coli ΔbioC mutant and (ii) knockout of bioC from A. baumannii (or K. pneumoniae). By using the CRISPR-Cas9 system (fig. S4, A and B) (33), we inactivated the bioC locus from A. baumannii. The mutant of A. baumannii devoid of bioC was validated by multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Sanger DNA sequencing (fig. S4C). As expected from bacterial viability, the removal of bioC rendered A. baumannii biotin auxotrophic (fig. S4D). We noticed that the plasmid-borne expression of AbBioC restores robust growth of the E. coli ΔbioC mutant on the nonpermissive condition (Fig. 2, E and F). The complementation of AbBioC corrected the inability of A. baumannii ΔbioC strain to appear on the biotin-lacking condition (Fig. 2, G and H). In addition, KpBioC genetically replaces EcBioC as the positive control BcBioC does (fig. S5A). As expected, the ΔbioC isogenic mutant of K. pneumoniae that we created here is also characterized by a biotin auxotroph and can be restored upon an introduction of either AbBioC or KpBioC (fig. S5B).

Fig. 2. Functional identification of A. baumannii bioC.

(A) The cluster of biotin synthesis operon. (B) The BioC-BioH path for biotin synthesis. As described in Fig. 1C, the inside graph indicates the viability of the biotin auxotroph ER90 empowered by the supplementation of exogenous biotin. (C) Phylogeny for the family of methyltransferases. The maximum likelihood (ML)–based phylogeny was inferred from 1000 bootstrap replicates and exhibited in a radial form. Apart from three distantly related enzymes TrmD (light pink), Dam (light blue), and COMT (brown), certain BioC enzymes of six different origins were included. Namely, they refer to Enterobacteriaceae (blue), Yersiniaceae (purple), Pectobacteriaceae (pink), Erwiniaceae (cyan), Bacillus (orange), and Acinetobacter (red). (D) An unrooted tree of bacterial BioC orthologs. The evolutionary history of BioC was also produced in terms of the ML method with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The percentages of replicate trees in which the associated taxa are clustered in the bootstrap test were labeled next to the branches. Accession numbers of individual BioC members were indicated accordingly. A. baumannii Dam (AbDam) acted as an internal reference for phylogeny. (E) The A. baumannii bioC paralog genetically restores the inability of biotin auxotrophic E. coli ΔbioC mutant on the nonpermissive condition. (F) Growth curves of the biotin auxotrophic E. coli ΔbioC mutants with or without a plasmid-borne A. baumannii bioC paralog. (G and H) The CRISPR-Cas9–based inactivation of A. baumannii bioC renders it biotin auxotrophic, and this is restored by in trans expression of the plasmid-borne bioC. Of three independent viability experiments, a representative photograph was given [(E) and (G)]. Growth curves were plotted [(F) and (H)], and each data point was shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). BioA, 7,8-diaminononanoate synthase; BioB, biotin synthase; Bpl, biotin protein ligase; OD600, optical density at wavelength of 600 nm.

The BioC toxicity characterized by bacterial growth inhibition is partially attributable to the depletion of Mal-ACP, a building block for the canonical FAS II pathway (7). Therefore, overproduction of BioC resembles the inactivation of malonyl-CoA-ACP transacylase (FabD) that catalyzes the conversion of malonyl-CoA (Mal-CoA) to Mal-ACP (7, 34). We adopted an arabinose-inducible promoter (ParaC)–driven construct for the SUMO-BioC fusion enzyme, along with its native form (fig. S6A). Consistent with the prior observation with BcBioC by Lin and Cronan (7), basal expression of AbBioC can support the viability of the biotin auxotroph E. coli ΔbioC on nonpermissive condition, while its arabinose-induced overexpression poisons the recipient E. coli (fig. S6, B and D). In contrast, the SUMO-BioC form of A. baumannii displayed its activity in vivo only when expressed at a high level (fig. S6, C and D). Because glucose is a repressor for ParaC promoter, we sought for altered activities of AbBioC in both native and chimeric versions (fig. S7, A and C). Unlike the native AbBioC form that virtually remains active in E. coli on the condition containing 0.2% glucose, regardless of the inducer arabinose addition (fig. S7B), the activity of SUMO-BioC hybrid form is arabinose dose dependent, independently of either 0.2% glucose (fig. S7B) or 0.2% glycerol (fig. S7C) as sole carbon source. The combined data genetically demonstrate the presence of BioC-like activity in certain ESKAPE members (A. baumannii and K. pneumoniae) and offer a means to produce the toxic protein BioC via the SUMO tag–based fusion expression strategy.

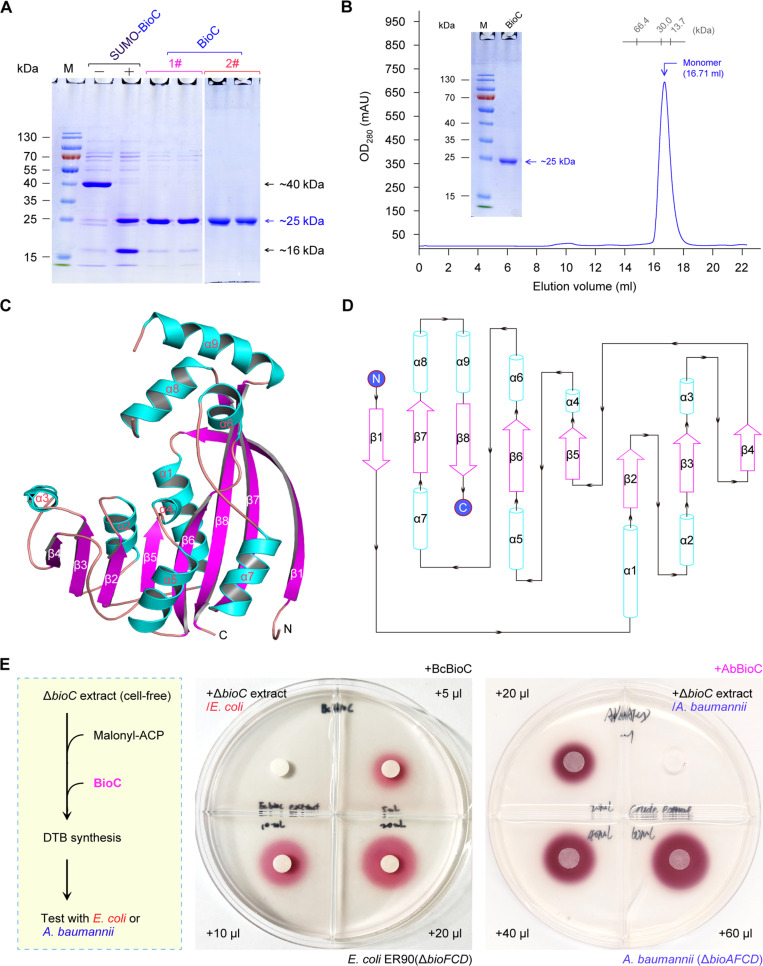

Characterization of AbBioC

The BioC enzyme belongs to a class I SAM-dependent O-methyltransferase. The phylogenetic analyses suggested that the class I methyltransferase is composed of diverse members placed into distinct subclades (Fig. 2C). This is largely attributed to the variation in the enzymatic substrate specificity (nucleic acids, small molecules, and lipids). In brief, (i) both TrmD [tRNA (guanosine(37)-N1)-methyltransferase] and Dam (adenine-specific DNA methyltransferase) recognize the substrate of nucleic acids; (ii) COMT (catecholamine O-methyltransferase) is specific to small molecule, and (iii) BioC prefers the malonyl group linked to ACP, a short-chain fatty acid. The unrooted tree illustrated that AbBioC-including clade restricted to Acinetobacter is appreciably closer to the Bacillus cousins (e.g., BcBioC) than EcBioC and KpBioC (Fig. 2D). It was assumed that the solubility of AbBioC is similar to that of the cousin BcBioC. Next, we engineered KpBioC and AbBioC by using the strategy of SUMO fusion expression. The native BioC enzymes were obtained upon the removal the N-terminal 6x His-tagged SUMO subunit (fig. S8). Similar to EcBioC in inclusion body, KpBioC without its SUMO tag steadily precipitates. It was noted that soluble AbBioC (~25 kDa) was liberated from its fusion version (~40 kDa) upon the removal of a SUMO tag (16 kDa) by the ubiquitin-like protease 1 (ULP1) (Fig. 3A and fig. S8). Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) revealed that AbBioC exists as a monomer (Fig. 3B), whose identity was verified with quadrupole orthogonal acceleration–time-of-flight mass spectrometry (fig. S9). The availability of soluble AbBioC enabled its structure-to-function study.

Fig. 3. Structure and function of AbBioC methyltransferase.

(A) Preparation of soluble AbBioC by expressing the N-terminal 6x His-tagged SUMO-fused BioC protein. The AbBioC is ~25 kDa; SUMO is ~16 kDa, and the resultant SUMO-BioC is estimated to be ~40 kDa. The symbols of plus (and/or minus) separately denote the presence (and/or absence) of ULP1 enzyme, which is designed to specifically remove the N-terminal 6x His-tagged SUMO. The numbers (1# and 2#) represent two rounds of nickel column–based protein purification. It was generated by the combination of two individual gels. (B) Gel filtration profile of Acinetobacter BioC protein. SEC of BioC protein was conducted using Superdex 75 column. The purity of the recombinant BioC (~25 kDa) is illustrated in the inside gel of 15% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). (C) Overall architecture of AbBioC. The α helices (α1 to α9) and β strands (β1 to β8) are shown as cylinders and fancy sheets, respectively. (D) Topological characterization of AbBioC. (E) Biotin bioassay demonstrated that BioC protein begins biotin synthesis in vitro. A representative result of both SDS-PAGE [(A) and (B)] and biotin/DTB bioassays (E) was given here (n = 3). A scheme on the left hand of (E) was formulated, illustrating the path of BioC-initiated biotin synthesis reconstituted in vitro. Here, the biotin-free ΔbioC crude extract (20 μl) is the negative control. Two types of BioC enzymes (BcBioC and AbBioC) were examined. As for the BcBioC control, it was assayed with the well-studied reporter strain of E. coli ER90(ΔbioFCD) (6, 63). Notably, the A. baumannii ΔbioAFCD mutant that we developed here was used as an indicator strain for assaying AbBioC function in vitro. N, N terminus; C, C terminus; BcBioC, Bacillus cereus BioC.

To examine the production of Mal-ACP methyl ester (M-Mal-ACP) by AbBioC (fig. S10A), we prepared its cognate substrate Mal-ACP in vitro, via the reaction catalyzed by Sfp (surfactin production) of Bacillus (fig. S10B). The canonical substrate for Sfp (apo-ACP) was given by the cleavage of holo-ACP by acyl carrier protein phosphodiesterase (AcpH) to eliminate the 4′-phosphopanthetheine (Ppan) prosthetic group (fig. S10C). Sfp converted apo-ACP to (i) holo-ACP by addition of CoA (fig. S10D) and (ii) Mal-ACP via ligation of Mal-CoA (fig. S10E). As expected from our AbBioC reaction with Mal-ACP substrate (measured mass versus theoretical value: 8933.789 versus 8933.39; fig. S10E), the final product of M-Mal-ACP was readily given, of which the actual mass is 8948.037 (fig. S10F). Next, we reconstituted the dethiobiotin (DTB) synthesis system in vitro using the biotin-starved ΔbioC crude extract (Fig. 3E). As observed for the reaction catalyzed by BcBioC as the positive control, the mixture of AbBioC catalysis allowed robust growth of the reporter strain ER90(ΔbioF/C/D) on the nonpermissive condition. This was judged by the reduction of the redox indicator 0.01% TTC (2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride) in the agar to a bright-red, insoluble formazan deposited that is proportional to the level of DTB intermediate (Fig. 3E). In conclusion, AbBioC is a functional member of Mal-ACP methyltransferases, beginning bacterial biotin synthesis (Figs. 2B and 3E).

Structure of BioC methyltransferase

To elucidate molecular basis for BioC catalysis, we performed x-ray crystallography studies. Of four BioC enzymes, two amenable cousins (BcBioC and AbBioC) were prepared in large scale and subjected to extensive crystallization trials. As a result, we solved one AbBioC/SAM complex structure at 2.54 Å resolution (Table 1). This crystal structure belongs to the P21 space group (Table 1) and contains four protomers per asymmetric unit (fig. S11). Each AbBioC protomer is assembled into two domain-swapped dimers (fig. S11A). However, the SEC profile demonstrated that AbBioC appears monomeric (Fig. 3B). As indicated by the low root mean square deviation values (0.29 to 0.35 Å2), overall α/β-foldings of the four AbBioC protomers are virtually identical (fig. S11, B and C). As described with each AbBioC protomer (Fig. 3, C and D), its architecture is composed of nine α helices (α1 to α9) and eight β strands (β1 to β8). The central stands (β2 to β8) form one flat sheet. Except for β8, the rest of β strands are parallel to each other. It was noted that the domain-swapped β1 (residues 1 to 20) replaces an α helix motif incorrectly predicted by AlphaFold (fig. S11, D to F). Helices α1 to α3 reside on one side of the β sheet, whereas α4, α5, and α7 are located on the opposite side (Fig. 3C). Notably, the remaining helices α6, α8, and α9 sit on this β sheet layer, and their orientations are roughly vertical to each other (Fig. 3C).

Table 1. Crystal data collection and refinement statistics of AbBioC in complex with its SAM cofactor or SIN inhibitor.

RMSDs, root mean square deviations.

| Structures | AbBioC-SAM complex | AbBioC-SIN complex |

|---|---|---|

| PDB ID | 8X8I | 8X8J |

| Data collection* | ||

| Space group | P21 | C2 |

| Cell parameter | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 71.06, 57.23, 143.67 | 116.70, 56.55, 70.68 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.00, 101.72, 90.00 | 90.00, 101.13, 90.00 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9792 | 0.9792 |

| Resolution (Å) | 70.34–2.54 | 57.25–1.72 |

| High-resolution shell (Å) | 2.67–2.54 | 1.81–1.72 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.3(99.9) | 98.9(99.9) |

| Redundancy | 3.2(3.3) | 5.8(5.8) |

| Rmerge (%) | 10.0(64.0) | 10.5(140.2) |

| I/σ(I) | 9.4(2.4) | 8.4(1.9) |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 70.34–2.54 | 40.48–1.72 |

| No. of reflections | 37621 | 47247 |

| Rwork (%)/Rfree (%) | 23.61/28.75 | 22.02/25.03 |

| No. of atoms | ||

| Protein | 7478 | 3662 |

| SAM/SIN | 4 | 2 |

| Water | 30 | 94 |

| RMSDs | ||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.003 | 0.005 |

| Bond angle (°) | 0.587 | 0.733 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | ||

| Most favorable | 97.71 | 98.69 |

| Additional allowed | 2.29 | 1.31 |

| Outlier | 0.00 | 0.00 |

*Values in parentheses are for the high-resolution shell.

Compared to the two putative methyltransferases [A. tumefaciens Tam (AtTam) and Anabaena variabilis Ava_0823], AbBioC gave the limited identity (19.07% for AtTam and 18.34% for Ava_0823; fig. S12A). The DALI search revealed that the architecture of AbBioC is most similar to that of AtTam [Protein Data Bank (PDB): 2P35] and Ava_0823 (PDB: 3CCF) (35). The N-terminal orientation differed markedly, albeit the conservation in their core structures (fig. S12, B and C). In our AbBioC structure (PDB: 8X8I), the SAM cofactor is occupied into a small cavity (figs. S11 to S13). Instead of SAM, one S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine (SAH) molecule is present in the AtTam structure (PDB: 2P35; fig. S12D). Probably, lacking the methyl group leads to different orientations of the amino motifs. In contrast, the conformations of the sugar puckers and the nucleobases are quite similar. The three SAM-interacting residues are extremely conserved and adopt similar conformations in the AbBioC/SAM complex and the AtTam/SAH structure (fig. S12D). To the best of our knowledge, this provides a previously unidentified glimpse of BioC architecture in the past 50 years (36, 37).

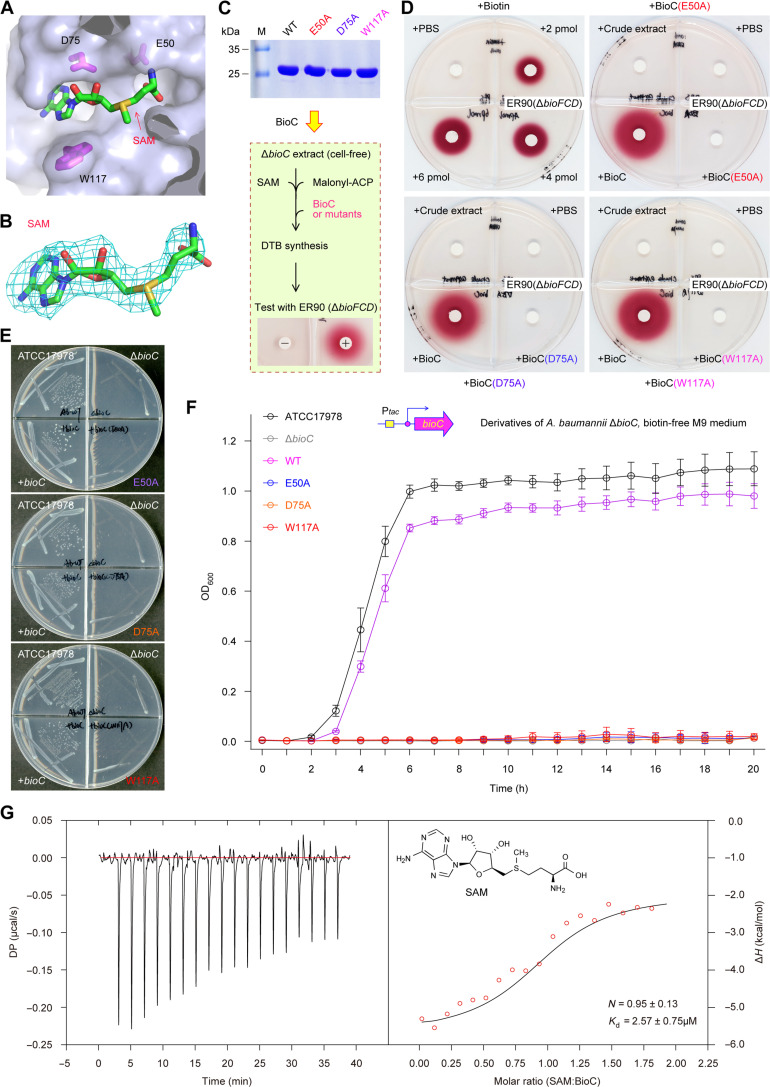

BioC binding of SAM cofactor

Compared to Ava_0823 (PDB: 3CCF) and AtTam/SAH (PDB: 2P35) structures, our SAM-liganded AbBioC structure offered more direct evidence for SAM as a cofactor to donate methyl group (figs. S12D and S13, A and B). Accordingly, each AbBioC protomer contains a SAM molecule (Fig. 4A and fig. S13A). As supported by the 2Fo-Fc electron density maps, the SAM molecule is well defined and adopts one extended conformation (Fig. 4B). The sugar pucker of SAM forms two hydrogen bond (H-bond) interactions with the side chain of aspartate-75 (D75), via its two hydroxyl groups (2.4 Å for 2′-OH and 3.0 Å for 3′-OH; fig. S13C). The nucleobase of SAM lies in a narrow cavity, flanked by leucine-76 (L76) on one side and tryptophan-117 (W117) on the other side. The N6 atom of the nucleobase interacts with the side-chain O atom of aspartate-96 (D96; fig. S13C). The amino motif of SAM inserts into AbBioC via a deep pocket (Fig. 4A and fig. S13C). Apart from its direct H-bond interaction with glycine-52 (G52), the amino motif also forms an extensive water-mediated H-bonding network across glutamic acid–50 (E50), cysteine-53 (C53), and leucine-58 (L58; fig. S13D). Both G52 and C53 locate at the “β2-α2” linker that connects β2 strand and α2 helix. The E50 of β2 strand and threonine-59 (T59) of α2 helix forms one stable H-bond interaction, favoring the formation of “β2-α2” linker (fig. S13D).

Fig. 4. Structural and functional definition of the SAM substrate recognition by AbBioC.

(A) The SAM-binding cavity of AbBioC enzyme. SAM molecule and AbBioC are shown as sticks and surface, respectively. Namely, three critical residues for SAM binding (indicated with magenta sticks) included E50, D75, and W117. (B) Fo-Fc omit the electron density map of SAM molecule. It was contoured at 2.5 sigma level. (C) SDS-PAGE (15%) profile for BioC mutants (E50A, D75A, and W117A) and BioC-based scheme for the system of biotin synthesis reconstituted in vitro. (D) Biotin/DTB bioassay revealed that the three SAM-binding residues are critical for enzymatic activity of BioC in the initiation of biotin synthesis. As described in Fig. 3E, the biotin/DTB synthesis system was reconstituted in vitro. The WT BioC added on paper discs acted as the positive control. Namely, the three AbBioC mutants with the defection in SAM binding here denote E50A, D75A, and W117A. (E) Structure-guided, site-directed mutagenesis suggested that three SAM-binding sites are essential for AbBioC activity. (F) The analyses of growth curves showed that none of the three single AbBioC mutants (E50A, D75A, and W117A) retains enzymatic activity. Growth curves (F) were produced, in which each data point was given as an average ± SD (n = 3). The ΔbioC strain of A. baumannii that is biotin auxotrophic acted as a recipient for plasmid-borne AbBioC mutants. (G) ITC analysis for stoichiometry of AbBioC binding to SAM cofactor. As for each of the bellowed experiments ranging from biotin bioassays (D), bacterial viabilities (E), to ITC assays (G), a representative result was shown here (n = 3). Of note, the values of both N and Kd were expressed as means ± SD (n = 3). N, stoichiometry; DP, differential power; ΔH, enthalpy.

Next, we applied structure-guided, site-directed mutagenesis to investigate the importance of SAM recognition in AbBioC function. In total, three single mutants of AtBioC (i.e., E50A, D75A, and W117A) were constructed and purified to homogeneity (Fig. 4C). Similar to the wild-type (WT) AbBioC protein, we tested whether these mutants remain active in vitro (Fig. 4D). In our DTB/biotin bioassay, the reporter strain ER90 displayed obvious growth that is evidenced by the deposition of insoluble red pigment in a biotin dose–dependent manner (Fig. 4D). Unlike the situation arising from both the blank PBS control and the negative control (A. baumannii ΔbioC crude extract), the WT AbBioC enzyme enabled the in vitro reconstitution of crude extract–based DTB/biotin synthesis (Fig. 4D), whereas none of the three AbBioC mutants can do this job in vitro (Fig. 4D). The similar scenarios were seen in the three plasmid-borne bioC mutants in the context of bacterial viability in vivo (Fig. 4, E and F). Moreover, our isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiment determined that a SAM cofactor displays appreciably tight binding to AbBioC enzyme with the stoichiometry of N = 0.95 ± 0.13 and dissociation constant (Kd) = 2.57 ± 0.75 μM (Fig. 4G). Collectively, these data pinpointed that SAM ligand recognition by AbBioC plays an important role in the initiation of biotin synthesis.

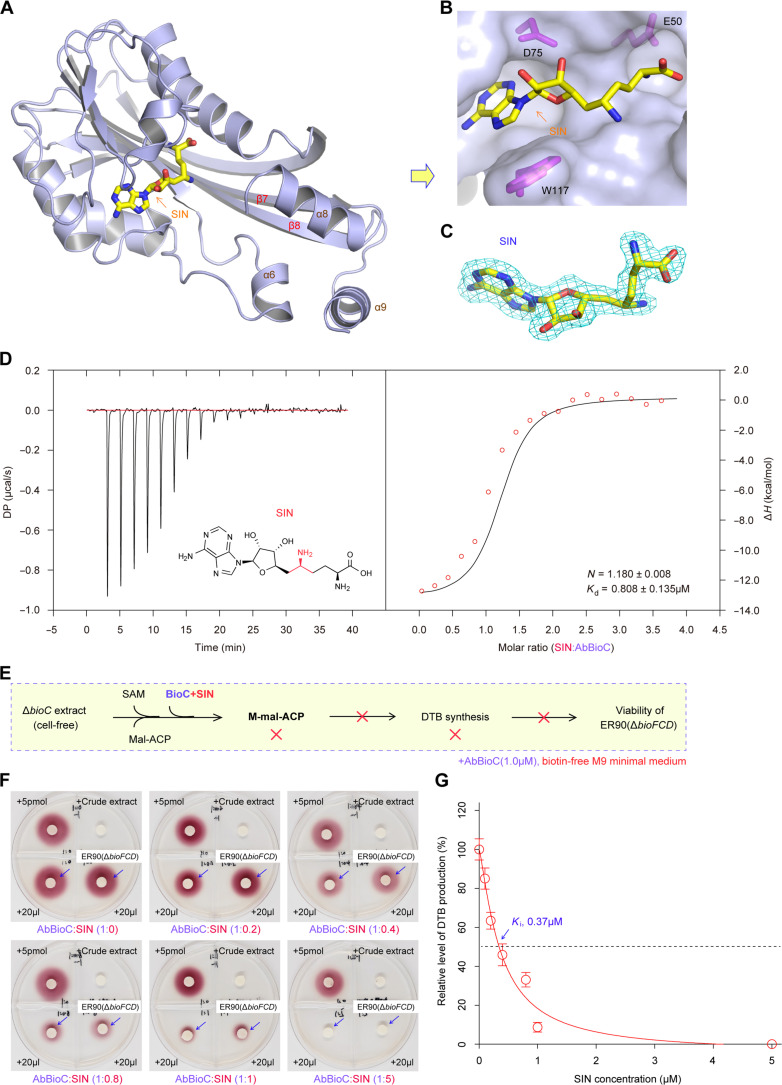

Molecular basis for inhibition of BioC by SIN

The natural product SIN is long recognized as a potent inhibitor against an arsenal of SAM-dependent methyltransferases (38). Lin and Cronan (7) reported that SIN can efficiently inactivate BcBioC enzyme in vitro; however, the structural mechanism remained unexplored. To close this gap, we also dissected the AbBioC/SIN complex structure (Fig. 5, A to C, and fig. S13, E to H). This crystal belongs to the C2 space group and contains two AbBioC/SIN complexes per asymmetric unit (PDB: 8X8J; Table 1). Structural comparison revealed that SIN is bound at the SAM-binding pocket of AbBioC (Fig. 5, A to C, and fig. S13, E to H). Similar to that of SAM (fig. S13, C and D), the nucleobase of SIN is sandwiched by L76 and W117 and forms one H-bond interaction with D96 (Fig. 5, A and B, and fig. S13E). The sugar pucker of SIN forms two H-bonds with the side chain of D75 (fig. S13E). However, the conformation of the amino motif of SIN (Fig. 5, A and B, and fig. S13, G and H) is different from that of SAM (Fig. 4, A and B, and fig. S13, A to D). As depicted in fig. S13F, unlike the nitrogen atom at the epsilon position (NE) of SIN forming only one H-bond with the main chain oxygen atom of S113, the N atom of SIN forms two direct H-bonds. The conformation of SIN amino motif is further stabilized by water-mediated H-bond interactions (fig. S13F). The ITC analyses determined that the SIN inhibitor can competitively bind to AbBioC enzyme (N = 1.180 ± 0.008 and Kd = 0.808 ± 0.135 μM; Fig. 5D). Compared with the physiological ligand SAM, the binding affinity of SIN is around threefold tighter (Fig. 4G). Subsequent DTB/biotin bioassay confirmed that SIN efficiently interferes with the ability of AbBioC in initiating biotin synthesis (Fig. 5, E and F). Consistent with its potent binding (Fig. 5D), the dose-dependent activity of SIN against AbBioC methyltransferase was featured by its inhibition constant (Ki) value of ~0.37 μM (Fig. 5G). In summary, the structural and biochemical characterization of AbBioC/SIN interplay provided insights into an inhibitory mechanism for BioC methyltransferase.

Fig. 5. Structural and functional evidence that the SIN inhibitor inactivates AbBioC activity.

(A) Overall structure of AbBioC complexed with SIN inhibitor. (B) The SIN inhibitor–binding cavity displayed on the surface of the AbBioC enzyme. The SIN molecule and AbBioC are shown as sticks and surface, respectively. Namely, three critical residues for SIN binding (indicated with magenta sticks) include E50, D75, and W117. (C) 2Fo-Fc electron density map of SIN molecule, contoured at 1.0 sigma level. (D) Use of ITC assay to probe binding stoichiometry between AbBioC and its SIN inhibitor. A representative ITC profile was given here (n = 3), and the N (and/or Kd) value was calculated as mean ± SD (n = 3). The ITC experiments with a SIN inhibitor were performed as described for SAM cofactor in Fig. 4G. The SIN molecule was shown inside the left-hand graph of (D). In comparison with the stoichiometry of SAM binding (N = 0.95 ± 0.13; Kd = 2.57 ± 0.75 μM; Fig. 4G), SIN affinity with AbBioC is appreciably stronger because of the threefold lower value of Kd (0.808 ± 0.135 μM). (E) Scheme for an impairment of the BioC-BioH pathway by the SIN inhibitor. The cross symbol denoted an inactivated step/pathway. (F) DTB/biotin bioassay revealed that the SIN inhibitor effectively kills AbBioC in the in vitro reconstituted system of DTB/biotin synthesis. Of three independent bioassays for SIN-stressed AbBioC, a representative photograph was shown here. (G) Determination of an inhibition constant Ki assigned to the SIN inhibitor on the basis of cell viability. To illustrate the Ki curve for the SIN inhibitor, three independent experiments were performed. The resultant output was given via nonlinear regression fitting curve (provided by GraphPad Prism), of which each point was expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). Ki value was measured to be ~0.37 μM.

Importance of β1 strand and R60 in BioC action

The β1 strand (residues 8 to 20) is unusual in that it enables AbBioC protein to form a domain-swapped dimer in the crystal structure (fig. S11A). It contained a conserved tyrosine-19 (Y19) residue (fig. S3), positioned at the C-end (fig. S14, A and B). Apart from the interaction between the two β1 strands, each β1 strand forms an extensive H-bond network with the β7 strand from the partner molecule. The β1 strand is distant from the SAM-binding site (fig. S14B), whereas two positively charged residues [lysine-27 (K27) and arginine-60 (R60)] are quite close to the binding pocket of the amino motif of SAM (fig. S14, B and C). The side chain of K27 points toward the outer surface of AbBioC, but the side chain of R60 folds back and gives H-bond interactions with two residues [serine-55 (S55) and glycine-56 (G56); fig. S14C]. To clarify their functional roles, we generated three single mutants (Y19A, K27A, and R60A), as well as the β1-deleted mutant, designated bioC(ΔN, 1-20). As expected from genetic complementation, functional loss of AbBioC was consistently observed upon either the Y19A substitution or β1 deletion (fig. S14, D and E). This largely agreed with the BcBioC(Y19F) mutant described by Lin and Cronan (7). Although K27 had no detective role, the R60A mutant of AbBioC failed to restore the growth of the biotin auxotroph, A. baumannii ΔbioC, on the nonpermissive condition (fig. S14, F and G). Similar to the E50 residue (fig. S13D), R60 also interacts with residues from the “β2-α2” linker. The essentiality of both E50 and R60 indicated that proper folding of the “β2-α2” linker is critical for the ligand SAM binding and action of AbBioC. To further ascertain the biochemical roles of β1 strand, we performed DTB/biotin bioassays. Unlike the WT AbBioC that initiates biotin synthesis in vitro, none of the BioC(Y19A), BioC(ΔN, 1-20), and BioC(R60A) mutants retained enzymatic activity in our trials (fig. S14H). Together, we favored that the β1-mediated conformational maintenance and the R60 residue–originated H-bond network both are implicated in AbBioC catalysis.

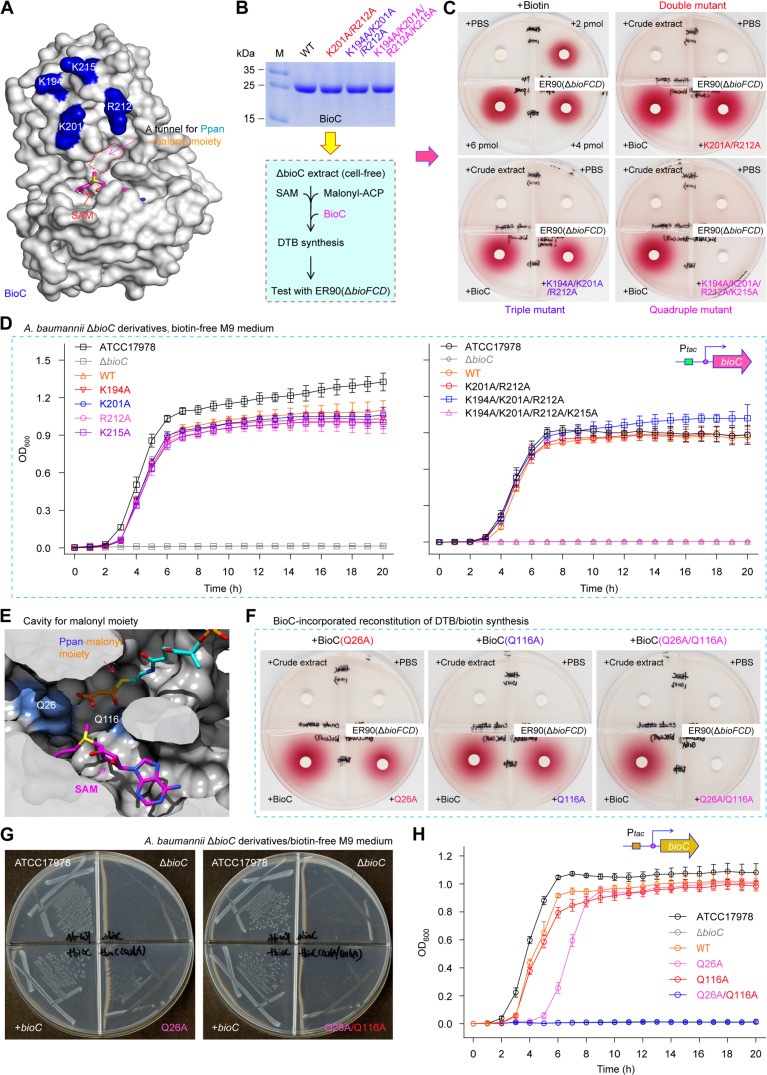

BioC recognition of primer Mal-ACP

Our continued efforts were unsuccessful in obtaining complex structure of AbBioC with its primer substrate Mal-ACP. This is, in part, if not all, due to its transient interaction with the primer. In addition, no substrate-bound complex structures were reported for the two distantly related methyltransferase (AtTam and Ava_0823). To investigate the dynamic binding, we built one AbBioC/Mal-ACP complex model using the autodocking program (fig. S15). Presumably, the malonyl moiety adopts one extended conformation, placing the carboxyl group next to the SAM for methylation (fig. S15A). The ACP carrier for malonyl moiety sits near the α8 and α9 helices (fig. S15A), and the overall shape of ACP and AbBioC are roughly complementary with each other (fig. S15B). Because that ACP is a negatively charged protein rich in certain acidic amino acids (i.e., Asp and Glu), it was postulated to interact with BioC through extensive electrostatic interactions. Surface structural analyses revealed that (i) the α8 and α9 helices of AbBioC contain three lysine residues (i.e., K194, K201, and K215), and (ii) the α8-α9 connecting linker has one arginine residue, R212. Moreover, all the four positively charged residues are relatively close in space (Fig. 6A) and located on the interfaces between AbBioC and the docked ACP molecule (fig. S15, A and B). To confirm functional roles of the K/R residues, an arsenal of mutants were assayed in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 6, A to D, and fig. S16). As expected from bacterial viability tests, (i) none of the four single AbBioC mutants (K194A, K201A, R212A, and K215A) loses the activity of binding cognate ACP carrier, and (ii) both the double mutant (K201A/R212A) and the triple mutant (K194A/K201A/R212A) are functionally indistinguishable from its parental version (Fig. 6D and fig. S16). In contrast, the quadruple mutation (K194A/K201A/R212A/K215A) impaired the function of BioC in restoring the biotin auxotrophic ΔbioC strains of E. coli and A. baumannii (Fig. 6D). We then prepared the mutated AbBioC proteins for enzymatic analysis (Fig. 6B). Consistent with the observation for genetic complementation (Fig. 6D and fig. S16), our DTB/biotin bioassay showed that only the quadruple derivative of AbBioC(K194A/K201A/R212A/K215A) is nonfunctional (Fig. 6C). Similar to those of BioH [and/or BioJ (39)] demethylase with the cognate ACP moiety (6, 14), the four positively charged AbBioC residues are assumed to play a synergistic role in recognition of the canonical ACP carrier.

Fig. 6. Probing interplay between AbBioC and its physiological substrate Mal-ACP.

(A) Surface structure of AbBioC enabled the visualization of four positively charged residues (K194, K201, R212, and K215). It was generated from structural presentation via the rotation by 90° counterclockwise (fig. S15B). (B) BioC-based scheme for the reconstitution of DTB/biotin synthesis system in vitro. (C) Biotin/DTB bioassay suggested that the quadruple mutant (K194A/K201A/R212A/K215A) of AbBioC losses its ability to trigger the DTB/biotin synthesis. (D) Combined site-directed mutagenesis and growth curves allowed us to determine functional loss of the quadruple mutant BioC (K194A/K201A/R212A/K215A). (E) Structural analysis of the malonyl moiety–loading tunnel within AbBioC methyltransferase. The phosphopantetheine (Ppan)–malonyl group arises from the cognate substrate Mal-ACP thioester. It seemed likely that the malonyl-recognizable channel converges with the SAM cofactor. The SAM cofactor and Ppan-malonyl moiety appear as sticks. The carbon atoms of SAM, PPan, and malonyl are shown with magenta, cyan, and orange, respectively. The sectioned view of AbBioC is displayed as surface. The other atoms are shown with red, blue, and yellow for oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur atoms, respectively. Green dashed lines denote H-bonds. Two putative neutralizing residues of AbBioC are colored light blue, namely, Q26 and Q116. AbBioC is shown as cartoon colored gray. (F) The double mutations of Q26 and Q116A inactivated the role of AbBioC in the system of biotin/DTB synthesis in vitro. (G and H) In vivo evidence that relative to the residue Q116, Q26 plays a major role in neutralizing the malonyl group of substrate Mal-ACP. As for both biotin bioassays [(C) and (F)] and bacterial viabilities (G), a representative result was presented (n = 3). Growth curves were generated on the basis of three independent measurements [(D) and (H)], and each data point was expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3).

A malonyl moiety-loading tunnel was mapped to converge with the SAM cofactor–occupied cavity. Presumably, two glutamines (Q26 and Q116) localized in the cavity bottom appear to neutralize the free carboxyl group of Mal-ACP substrate (Fig. 6E and fig. S17A). The neutralization pattern might represent a common mechanism for FAS-relevant enzymes. This is because similar scenarios have been observed for the Mal-CoA:ACP transacylase FabD (40, 41), the pimeloyl-CoA synthetase BioW (8, 9), and an atypical biotin synthesis enzyme BioZ (11). To ascertain this postulate, we generated three AbBioC derivatives that include two single mutants (Q26A and Q116A) and a double mutant (Q26A/Q116A). Among them, only the double-mutant AbBioC (Q26A/Q116A) enzyme (fig. S17B) was disabled to reconstitute the DTB/biotin synthesis in vitro (Fig. 6F). This was further supported by the fact that only the single mutant (i.e., Q26A and Q116A) is permitted to render robust viability of the biotin auxotrophic ΔbioC strain of A. baumannii (and/or E. coli) on the biotin-free M9 medium (Fig. 6, G and H, and fig. S18, A and B). Unlike the two known channels that rely on the basic amino acid, arginine [R117 for FabD (40, 41) and R159/R201 for BioW (8)], the AbBioC counterpart, exploits two polar residues Q26/Q116 to neutralize the free carboxyl group of malonyl substrate (fig. S17A). Therefore, the combined data in vitro and in vivo illustrated the landscape of AbBioC interplay with its Mal-ACP substrate.

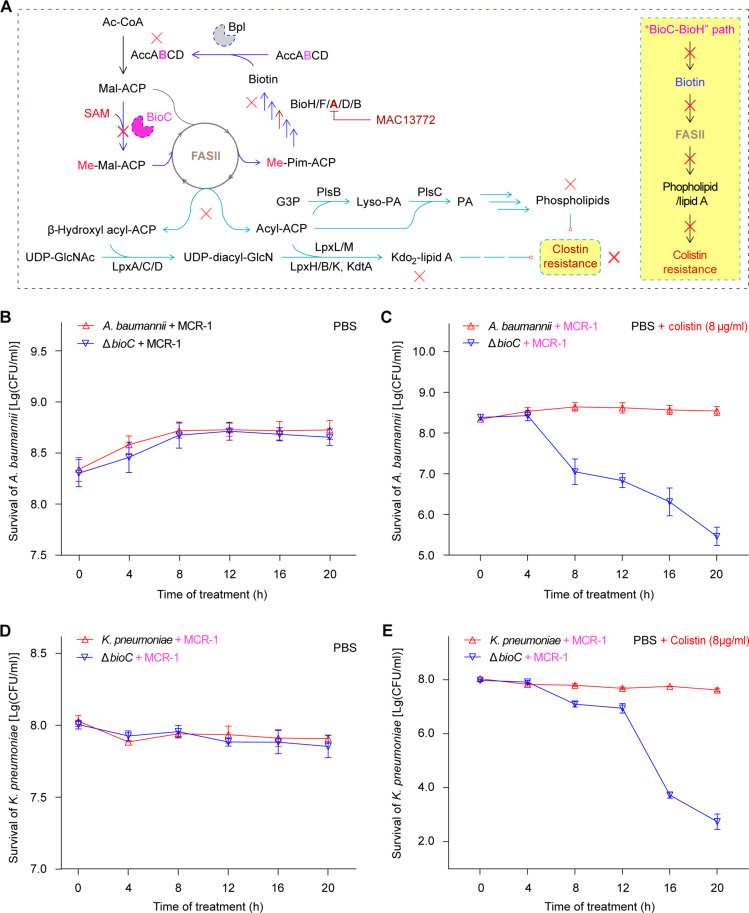

The involvement of BioC in mobile colistin resistance

Not only does biotin synthesis rely on FAS II pathway (5), but it also provides biotin ligand for the biotinylated acetyl-CoA carboxylase dedicated to a first-committed step of FAS II cycle (Fig. 7A). Perturbation of FAS II route by certain inhibitors (e.g., cerulenin for FabB/F and triclosan for FabI) abolished phospholipid/lipid A synthesis via restricting the pool of free fatty acids (Fig. 7A). The depletion of lipid A and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), two substrates for mobile colistin resistance (MCR) modifying enzyme, explained, in part (if not all), the resensitivity of mcr-1–positive ESKAPE pathogens to polymyxin, a last-resort defense antibiotic (Fig. 7A) (27). We therefore posited that the BioC primary step of biotin synthesis is implicated in colistin-induced lysis resistance provided by MCR-catalyzed lipid A modification in certain clinically relevant ESKAPE pathogens (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. A role of BioC methyltransferase in Acinetobacter MCR-1 colistin resistance.

(A) Scheme for BioC-BioH pathway of biotin synthesis that connects FAS II–centering phospholipid/lipid A synthesis with the phenotypic colistin resistance route. It seemed likely that targeting biotin synthesis can bypass bacterial colistin resistance. (B) The bioC deletion fails to markedly alter bacterial survival of mcr-1–containing A. baumannii in PBS buffer. (C) Removal of bioC can resensitize MCR-1–producing, polymyxin-resistant A. baumannii to colistin at a level of up to 8 μg/ml. (D) The viability of K. pneumoniae ΔbioC mutant is indistinguishable from its parental strain in PBS buffer. (E) Expression of MCR-1 fails to render the K. pneumoniae ΔbioC mutant insusceptible to colistin. The colistin killing curves [(B) and (E)] were plotted with the Excel software on the basis of three independent trials, and the value of each data point was displayed as mean ± SD (n = 3). Ac-CoA, acetyl-CoA; Acc, acetyl-CoA carboxylase; AccABCD, four subunits of the Acc enzyme complex (AccA, α subunit of carboxyltransferase; AccB, BCCP; AccC, a biotin carboxylase; and AccD, β subunit of carboxyltransferase); ACP, acyl carrier protein; Mal-ACP, malonyl-ACP; Me-M-ACP, monomethyl Mal-ACP; Me-Pim-ACP, monomethyl pimeloyl-ACP; BioC, Mal-ACP methyltransferase; BioH, methyl-pimeloyl ACP ester demethylase; BioF, 7-keto-8-aminopelargonic acid synthase, the pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP)–dependent enzyme (AON synthase); BioA, 7,8-diaminononanoate synthase, the PLP-dependent transaminase; FAS II, type II fatty acid synthase system; G3P, glycerol-3-phosphate; PlsB, G3P acyltransferase; PA, phosphatidic acid; Lyso-PA, lysophosphatidic acid; PlsC, Lyso-PA acyltransferase; UDP-GlcNAc, uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine; UDP-diacyl-GlcN, uridine diphosphate glucosamine; Kdo2-lipid A, 3-deoxy-d-manno-octulosonic acid-lipid A; LpxA, the first acyltransferase of the Raetz pathway for lipid A synthesis; LpxC, UDP-3-O-(R-3-hydroxyacyl)-N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase; LpxD, acyl-ACP–dependent N-acyltransferase; LpxL, lauroyltransferase; LpxM, myristoyltransferase; LpxH, UDP-2,3-diacylglucosamine hydrolase; LpxB, a membrane-associated glycosyltransferase; LpxK, tetraacyldisaccharide 4′-kinase; KdtA, Kdo transferase of Raetz pathway.

To examine this hypothesis, we analyzed bacterial lysis as recommended by Carfrae et al. (27). Similar to the ΔbioC mutant of A. baumannii ATCC 17978 devoid of an early step of biotin synthesis (Fig. 2B and fig. S4), the strain ATCC 43816 of classical hypervirulent K. pneumoniae (hvKP) was also subjected to CRISPR-Cas9 manipulation, giving its ΔbioC derivative. All the four strains were engineered to express mcr-1 carried by the corresponding recombinant plasmids. As expected, the subinhibitory levels of neither MAC13772 inhibitor (4 μg/ml) nor colistin (8 μg/ml) lysed bacterial cells (fig. S19). In contrast, the combination of MAC13772 with colistin was synergistically active against mcr-1–expressing A. baumannii (fig. S19). Consistent with the observation for E. coli by Carfrae and coworkers (27), this largely verified our A. baumannii–based lysis assays. Similar to those of the negative control, A. baumannii (Fig. 7B), the treatment of PBS buffer had no impacts on the viability of K. pneumoniae and its ΔbioC mutant cells, regardless of MCR-1 (Fig. 7D). The removal of bioC elicited the vulnerability of mcr-1–expressing A. baumannii cells to bactericidal colistin even at the subinhibitory level of 8 μg/ml (Fig. 7C). As for mcr-1–harboring K. pneumoniae cells (Fig. 7E), CRISPR knockout of bioC phenocopied the inactivation of E. coli BioA (27) and mimicked the phenotypes observed with synergistic perturbation of MAC13772/colistin on E. coli (27) and A. baumannii (fig. S19). In sum, we concluded that (i) BioC-initiating biotin synthesis is a metabolic prerequisite for the formation of MCR-mediated polymyxin resistance and (ii) biotin synthesis inhibitors synergize colistin against infections with mcr-1–expressing ESKAPE agents.

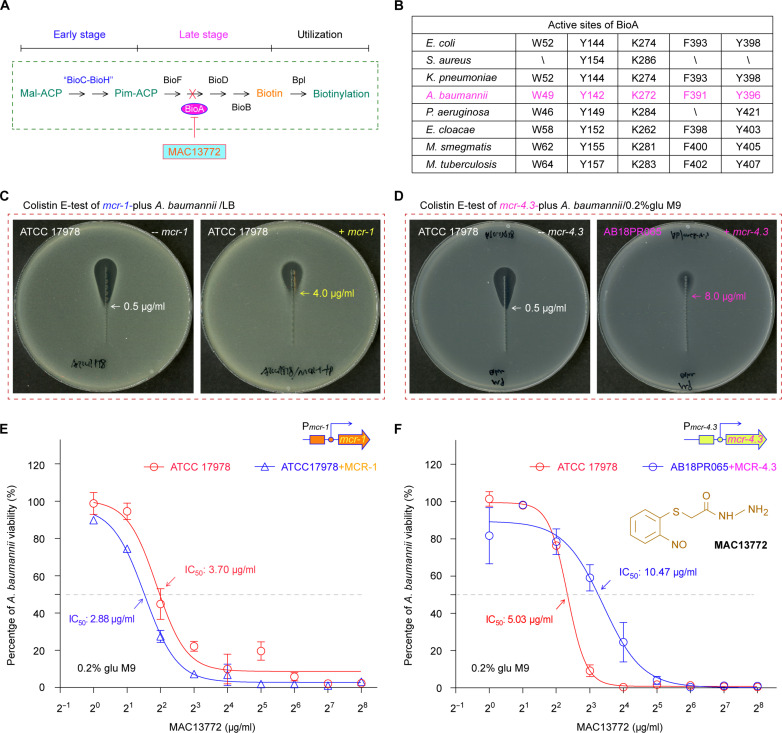

Targeting biotin synthesis to bypass colistin resistance

The acquisition of mcr-1 determinant facilitated A. baumannii to become a top priority ESKAPE pathogen causing untreatable nosocomial infections (42). This was because (i) MCR-1, the mcr-1 gene product, acts as a member of the lipid A–phosphoethanolamine (PEA) transferase family and modifies lipid A moiety linked to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) on a bacterial surface (43) and (ii) the production of MCR-1 in clinical isolates compromises the renewed interest of the last-resort antibiotic colistin in a health care setting (44, 45). Consistent with mycobacterial biotin synthesis as a validated druggable pathway (21, 22), certain ESKAPE members can be eliminated (23), following the treatment with MAC13772, the BioA inhibitor (Fig. 8, A and B) (46). It is well known that the MAC13772 inhibitor covalently binds pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP) and gives an adduct of SAM cofactor/MAC13772 (fig. S20), tightly fixed at the catalytic center via an extensive H-bond network (K274 and Y398) along with hydrophobic interaction (W52, Y144, and F393; Fig. 8B) (23). However, it is an unanswered question of whether interfering biotin synthesis remains active in combating the recalcitrant mcr-harboring A. baumannii with colistin resistance.

Fig. 8. Acinetobacter biotin synthesis is a druggable pathway.

(A) Schematic diagram for biotin synthesis blocked by MAC13771 inhibitor. (B) Analyses for five active sites in BioA dedicated to the late stage of biotin synthesis. Top: A scheme for BioA having a role in the late step of biotin synthesis. Bottom: Conservation analyses of BioA active sites among a panel of ESKAPE-including bacteria. E-test measurement reveals that expression of plasmid-borne mcr-1 (C) and/or mcr-4.3 (D) enable the A. baumannii strain to be insusceptible to the last-resort antibiotic colistin. A representative photograph for colistin E-test (n = 3) was given here (C and D). (E) Measurement of MAC113772 half-maximum inhibitory concentration (IC50) for A. baumannii ATCC 17978, regardless of mcr-1. (F) Comparable level of MAC113772 IC50 for the A. baumannii strain with/without mcr-4.3. To determine the IC50 value of MAC13772, the BioA inhibitor, three independent evaluations were conducted [(E) and (F)]. The nonlinear regression curve fit (provided by GraphPad Prism) was applied, and data points were expressed as means ± SD (n = 3). Unlike the engineered strain of A. baumannii ATCC 17978 that harbors a plasmid-borne mcr-1 [(C) and (E)], AB18PR065 is a clinical isolate of A. baumannii bearing mcr-4.3, an additional MCR subtype [(D) and (F)]. Pim-ACP, pimeloyl-ACP; mcr-1, a prototype of mobile colistin resistance determinant; mcr-4.3, the fourth new subtype of MCR resistance elements.

We then constructed a colistin-resistant A. baumannii strain that harbors a plasmid-borne mcr-1 (47, 48), in addition to the swine isolate of A. baumannii AB18PR065 containing mcr-4.3 (49), a distinct subtype of the MCR family (50, 51). As expected from our colistin E-test, an introduction of mcr-1 into the ATCC 17978 strain of A. baumannii led to an increment of colistin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) from 0.5 to 4.0 μg/ml (Fig. 8C). The mcr-4.3–carrying strain of A. baumannii AB18PR065 displayed a colistin MIC of 8.0 μg/ml, twofold higher than that of the mcr-1–bearing strain of A. baumannii (Fig. 8D). The analyses of growth curves revealed that the MAC13772 inhibitor is functional in interfering viability of the reference strain of A. baumannii ATCC 17978 with or without mcr-1 (fig. S21, A and B). The half-maximum inhibitory concentration (IC50) of MAC13772 was determined at the almost identical level for the strain ATCC 17978, regardless of mcr-1 (Fig. 8E). A similar scenario was observed for the mcr-4.3–positive strain of A. baumannii (fig. S21, C and D), of which the MAC13772 IC50 is labeled with 10.47 μg/ml, only around twofold higher than that of the colistin-susceptible control strain (Fig. 8F). The results demonstrated that the MAC13772 inhibitor is active in dampening the survival of A. baumannii albeit of MCR-1/4 colistin resistance.

In addition, we extended an assay of MAC13772 inhibition to the colistin-resistant, virulent K. pneumoniae, a critically prioritized ESKAPE member. Colistin E-test showed that the strain ATCC 43816 of K. pneumoniae exhibits colistin MIC of 32 μg/ml upon MCR-1 expression, 64-fold higher than that of the recipient strain alone (fig. S22A). The kind of insusceptibility to colistin was also observed for the strain ZZW20 of wastewater origin (52), an ST11 K. pneumoniae isolate producing MCR-8, a distinct variant of the MCR family (53). As a result, the mcr-1–bearing K. pneumoniae gave the MAC13772 IC50 of 59.96 μg/ml, at a comparable level to that of ATCC 43816 strain alone (i.e., 78.39 μg/ml). Meanwhile, MAC13772 IC50 of 156 μg/ml was assigned to the strain ZZW20 having MCR-8 colistin resistance (fig. S22B). Consistent with the observation for K. pneumoniae by Carfrae et al. (23), approximately 20- to 30-fold elevation of MAC13772 IC50 was noted for K. pneumoniae relative to A. baumannii (fig. S22B). We favored that the limited efficacy of MAC13772 inhibition is mainly due to the poor membrane permeability of K. pneumoniae caused by its capsular hypermucoviscosity (54).

A role of BioC in K. pneumoniae hypervirulence

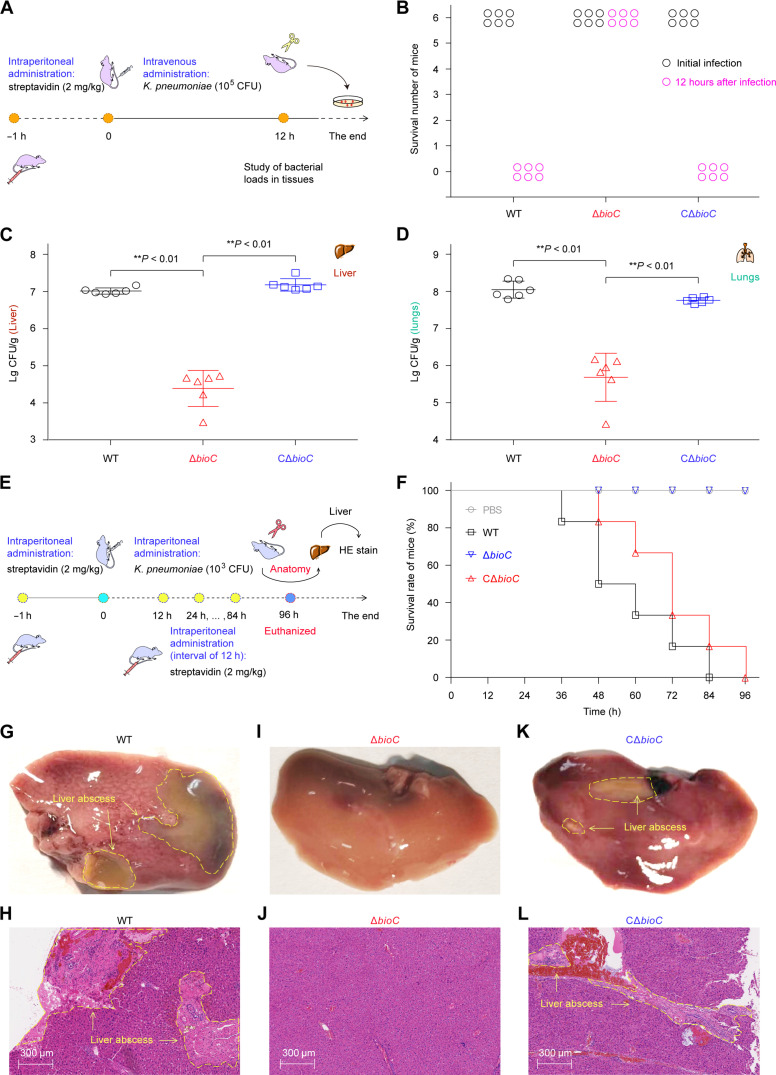

The majority of canonical hvKP isolates that are positive in string tests accounts for certain deadly community-acquired infections featuring pyogenic liver abscess (55–58). The phenotypic hypervirulence is largely due to the acquisition of some pLVPK-like virulence plasmids (59–61), which generally contain, but is not limited to, the rmpA/A2 regulatory gene controlling mucoid phenotype A (61, 62). Of the two dominant K1/K2 capsule types, the ATCC 43816 strain is a classical K2-type hvKP strain (55–58). Because the M-pim-ACP demethylase BioH/BioJ is implicated in bacterial infection (24, 63), we asked the question of whether its pairing enzyme, BioC methyltransferase, has a similar role (Fig. 9). To test this postulate, we evaluated the effects of bioC inactivation on the hvKP strain ATCC 43816 by using CD-1 mice models, namely, (i) intravenous administration (Fig. 9A) and (ii) intraperitoneal infection (Fig. 9E). Given that an average plasma biotin level of ~13.5 ng/ml (~55.4 nM) in CD-1 mice is around 5.5-fold higher than that (2.4 ng/ml, ~9.8 nM) of human plasma (fig. S23) (24), we leveraged intraperitoneal preadministration with streptavidin (2 mg/kg) at 1 hour before the mouse challenge with K. pneumoniae, resembling human plasma environment (23). First, we performed intravenous challenge of CD-1 mice with 1 × 105 CFU of K. pneumoniae and categorized them into three groups (six mice each) that were separately inoculated with WT, ΔbioC, and CΔbioC. Unlike that the entire WT-inoculating group was dead at 12 hours after infections; all the six challenged mice invariantly survived upon the removal of bioC (Fig. 9B). In contrast, the reintroduction of plasmid-borne bioC restored full virulence of the recipient ΔbioC (Fig. 9B). Next, we sought to evaluate varied levels of bacterial loads in four organs consisting of the liver (Fig. 9C), lungs (Fig. 9D), spleen (fig. S24A), and kidneys (fig. S24B). As expected, bacterial loads of ΔbioC recovered from all the examined organs declined markedly, in that it is over 2-log lower than its parental type. Replication defects of ΔbioC in different tissues were entirely reversed upon genetic complementation with a plasmid-borne bioC (Fig. 9, C and D, and fig. S24).

Fig. 9. The BioC-aided early step of biotin synthesis is required for full virulence of K. pneumoniae, an important ESKAPE member.

(A) Scheme for a model of CD-1 mice intravenously challenged with K. pneumoniae ATCC 43816. (B) Survival of CD-1 mice at 12 hours after infection. (C) The reduced survival of the K. pneumoniae ΔbioC mutant in the mouse liver. (D) The removal of bioC compromised survival of K. pneumoniae in the mouse lungs. As for intravenous infections [(B) to (D)], each symbol (circle/triangle/square) represents one mouse per group (n = 6). The data are expressed as means ± SD, and the significance of difference was checked with one-way ANOVA provided by GraphPad Prism. **P < 0.01. (E) Schematic diagram for the survival and pathological alteration of CD-1 mice infected with 103 CFU of K. pneumoniae. (F) Comparative analysis for survival curves of CD-1 mice challenged with different K. pneumoniae strains (103 CFU). (G) Anatomical presentation of pyogenic abscess from CD-1 mouse infected with K. pneumoniae. (H) Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining displayed the pyogenic abscess–related lesions from the infected CD-1 mice. (I) No lesions on the mouse liver after infection with the K. pneumoniae ΔbioC mutant. (J) Use of HE staining to visualize liver tissues from the CD-1 mouse infected with the ΔbioC mutant. (K) The plasmid-borne expression of bioC restores the ΔbioC mutant’s pathogenesis in the CD-1 mice model, leading to the clinical symptom of liver abscess. (L) HE staining demonstrated that pyogenic abscess is reproduced in the liver section from the CD-1 mouse infected with the CΔbioC strain. As for both anatomy [(G), (I), and (K)] and HE stains [(H), (J), and (L)], a representative result was presented from one mouse per group (n = 6). The symptoms of liver abscess were circled with yellow dashed lines white arrows.

To analyze putative lesions of liver abscess, we used the systemic/intraperitoneal model of CD-1 mice, which were challenged with 1 × 103 CFU of K. pneumoniae at 1 hour after administration of streptavidin (2 mg/kg). Notably, an administration with streptavidin (2 mg/kg) was intraperitoneally introduced at regular intervals of 12 hours within the whole monitoring period of 96 hours (Fig. 9E). In total, 24 CD-1 mice included here were divided into four groups (six mice each). As shown in survival curves, none of the six ΔbioC-infecting mice died within 96 hours, which is almost identical to that of the negative control (Fig. 9F). As expected, all the mice were gradually killed by K. pneumoniae expressing bioC, regardless of its carriage on chromosome or plasmid (Fig. 9F). Then, we conducted histopathological analyses for mouse livers obtained from experimental groups. The combinations of anatomical assays with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining clearly unveiled that (i) pyogenic abscess occurs on the mice liver from the WT-infecting group (Fig. 9, G and H) but not for the negative control (fig. S25, A and B) and the ΔbioC-infecting group (Fig. 9, I and J) and (ii) typical lesions of liver abscess invariantly recur in the group challenged with the CΔbioC strain (Fig. 9, K and L). Therefore, these findings provided functional proof that BioC methyltransferase is a virulence factor in K. pneumoniae, representing a promising anti-ESKAPE drug target.

DISCUSSION

Biotin acts as a nutritional virulence factor (24, 64). Although biotin synthesis is a validated druggable pathway (21, 22), most of lead compounds [e.g., MAC13772 (46)] are confined to the late-stage enzyme BioA (22, 65). The delayed discovery of inhibitors against the primary step is largely due to the incomplete understanding of the dominant BioC-BioH pathway (66, 67). The local BLASTp search against the National Center for Biotechnology Information database allowed us to track the carriage of AbBioC homolog (19.64 to 100% identity; 200-311aa long) from 118,209 of 286,825 bacterial genomes as of May 2023 (~41.2%). Apart from the promiscuous activity of BioH that renders it challengeable to obtain a specific inhibitor (5), the nonavailability of the BioC structure hampers in silico screen and design of lead compounds (7, 22). The prototypic version, EcBioC, is poorly active in the preparation in vitro (5, 7). In addition to its close relative of the soil bacterium Pseudomonas putida (PpBioC, 37.45% identity), EcBioC is genetically replaced with the distantly related paralogs from two Gram-positive bacteria, a foodborne pathogen B. cereus and the food spoilage–causing agent Kurthia (7, 32). Despite the fact that BcBioC and its counterpart of Kurthia (~50% identity) are metabolically engineered to produce odd-carbon dicarboxylic acids of industrial importance in E. coli (32), the solubility of BcBioC is intrinsically unsuitable for protein crystallization. To solve this puzzle, we concentrated on the top priority ESKAPE pathogens. Fortunately, we had a success in solving the high-resolution crystal structures of AbBioC liganded with SAM cofactor (Figs. 2E and 4A) and SIN inhibitor (fig. S13, E to I). As a SAM analog naturally produced by Streptomycetes (38), SIN is a promiscuous pan-MTase inhibitor against diverse pathogens ranging from viral domains (68) to bacterial lineages (7, 69). Given the criteria (i) functional equivalence of AbBioC to BcBioC (fig. S5) and (ii) SIN, a mimicry of SAM cofactor, the AbBioC/SAM and AbBioC/SIN complex structures functionally define inhibitory mechanism of BioC methyltransferase (figs. S13 and S14). Moreover, it laid a foundation for structural modification central to SAM/SIN scaffold. Considering its in vivo release and clinical efficacy, SIN-loaded nanoparticle is expected to be coupled with an appropriate delivery system (70). This explains partially (if not all) the inability of free SIN in diminishing viability of bioC-expressing bacterium.

Recently, Tam (MSMEG_0629) of M. smegmatis was proposed as MsBioC O-methyltransferase that retains limited activity of replacing EcBioC, instead of detoxifying trans-aconitate (15). However, the poor yield of MsBioC/Tam hampers our structural/biochemical investigation (15). A similar scenario was observed for the refolded EcBioC form (5). AbBioC, as we determined here, is also annotated as a Tam-like methyltransferase, albeit its limited identity to MsBioC/Tam (18.67%). In contrast to MsBioC/Tam that has low BioC-like activity (15), AbBioC is capable of enabling robust growth of the ΔbioC mutants of both E. coli and A. baumannii on nonpermissive condition (figs. S5 and S6). Genomic context revealed that bioC is situated either in the biotin gene cluster or as a chimeric bioHC (or bioCD) version (fig. S26), suggesting some evolutionary advantage. Our results indicated that the disguise of AbBioC with an N-terminal SUMO tag efficiently benefits large-scale preparation of soluble AbBioC proteins engaged in structural and functional exploration. It was noted that we have captured four functional modules. Namely, they included (i) a SAM cofactor–binding cavity (Fig. 4), (ii) the ACP-interacting surface rich in positive residues (Fig. 6, A to D), (iii) the tunnel for Ppan-linked malonyl moiety loading (Fig. 6, E to H), and (iv) an essential “Y19-containing β1 sheet” motif (fig. S14). Therefore, the data provided the previously unelucidated architecture and functional insights into BioC methyltransferase.

The transferability of polymyxin resistance is a global challenge of health care concern (71). This is largely due to MCR determinants (mcr-1 to mcr-10) carried by diverse plasmids (47, 72). In principle, the kind of integral membrane protein MCR catalyzes the transfer of PEA moiety from the lipid PE donor to the lipid A group tethered to surface LPS of Gram-negative bacterium (43). The resultant neutralization of the net negatively charged surface is desensitized to killing with cationic antimicrobial polypeptides (such as colistin), a “last-line” defense against multidrug-resistant ESKAPE-type pathogens. Carfrae et al. (27) reported that the disruption of bacterial FAS II pathway circumvents polymyxin resistance. This is because FAS II machinery provided building blocks for PE and lipid, two essential substrates of MCR catalysis (Fig. 7A) (43). Because the AccB subunit of ACC enzyme requires biotin modification to start bacterial FAS II pathway (25), biotin synthesis and its utility is implicated in the formation of bacterial insusceptibility to colistin (Fig. 7A). This assumption is validated by the fact that (i) Acinetobacter bioF (A1S_0807) encoding BioF, participates in formation of natural colistin resistance (73) and (ii) MAC13772, an effective BioA inhibitor, restores polymyxin sensitivity in mcr-1–expressing bacterial species (27). Unlike BioF and BioA that are two enzymes involved in the biotin late step (Fig. 2B), we observed that CRISPR-Cas9–aided elimination of the biotin primary stage enzyme BioC resensitizes A. baumannii (Fig. 7, B and C) and K. pneumoniae (Fig. 7, D and E) to colistin. We thereafter reasoned that the other BioH player of BioC-BioH path is also involved in phenotypic polymyxin resistance. Along with a recent finding of Carfrae et al. (27), our genetic and microbial investigation pinpointed that the biotin/fatty acid synthetic pathway functions as a metabolic basis for MCR polymyxin resistance. Notably, our work reported a previously unidentified role of BioC in impairing bacterial hypervirulence of K. pneumoniae with a hallmark of liver abscess (Fig. 9). Retrospectively, a number of BioH/J isoforms have been implicated in bacterial pathogenesis, which extends from the two intracellular agents, Francisella (63, 74) and M. tuberculosis (21), to an extracellular ESKAPE pathogen, P. aeruginosa (24). Thus, we believed that targeting BioC-directed primary step is beneficial to elucidate some lead compounds against untreatable infections with recalcitrant ESKAPE pathogens. Because the single mycobacterial Bpl seemed as an alternative anti-TB target (21), further evaluation of BplA as a potential target is also deserved in the anti-ESKAPE therapy.

In summary, structural and biochemical characterization in this study illustrates a comprehensive landscape of BioC methyltransferase. Apart from its initiating biotin synthesis, BioC seems moonlighted into two unrelated functions, polymyxin resistance and nutritional virulence. Therefore, targeting the dominant BioC-BioH primary pathway is prioritized as an approach of “killing two birds with one stone,” expanding the current repertoire of limited lead inhibitors against the nosocomial ESKAPE threats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement

The maintenance and manipulation of all the ESKAPE agents and their isogenic mutants plus complemented strains were performed in the biosafety level 2 (BSL-2) laboratories at the Zhejiang University School of Medicine. As for all the experiments of mice infections, they were carried out under the guidelines and regulations of the Administration of Affairs Concerning Experimental Animals approved by the State Council of People’s Republic of China (11-14-1988). The protocol for studies on mice was licensed by the Laboratory Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee, Zhejiang University (ZJU20230459). Under appropriate regulation, plasma samples of healthy individuals were kindly provided by General ICU of the Second Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

In total, 10 kinds of different bacterial species were cultivated here. Apart from three reference strains (E. coli, B. subtilis, and B. cereus), the rest of the bacteria corresponded to ESKAPE members (table S1). Namely, they included (i) E. faecalis, (ii) S. aureus, (iii) K. pneumoniae, (iv) A. baumannii, (v) P. aeruginosa, (vi) E. cloacae, and (vii) E. aerogenes. Except for E. faecalis grown on Tryptic soy agar, all the remaining bacteria were kept on Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C. All the E. coli strains were derived from the model strain MG1655 with appropriate genetic modification (75). The two strains of E. coli, ER90(ΔbioF/ΔbioC/ΔbioD) (5, 76) and STL24 (ΔbioC) (5, 7), were biotin auxotroph (36) and required biotin for viability. Using CRISPR-Cas9 technology, two types of ΔbioC deletion mutants (i.e., FYJ6108 and FYJ6184) were separately created from A. baumannii ATCC 17978 (33) and K. pneumoniae ATCC 43816 (table S1) (77). Before functional cloning and protein expression of BioC enzymes, varied bioC orthologs were amplified with PCR accordingly. Namely, they corresponded to (i) EcBioC/E. coli MG1655, (ii) BcBioC from B. cereus ATCC 10987 (78), (iii) AbBioC for A. baumannii ATCC 17978 (33), and (iv) KpBioC arising from K. pneumoniae ATCC 43816 (77). Unlike DH5α that was a cloning host, BL21(DE3) acted as an expression host for heterogeneous protein production. The assays of bacterial viability and growth curves were conducted with M9 minimal medium to evaluate biotin requirement. When necessary, either kanamycin (50 μg/ml) or apramycin (50 μg/ml) was supplemented for colony selection.

Plasmids and molecular manipulations

In total, four types of plasmids were applied here, including (i) pBAD24H constructs (50), (ii) pET/pET-SUMO series (79), (iii) pWSK129 derivatives (80), and (iv) pCas9-borne versions (table S2) (33). First, an arabinose-induced expression vector pBAD24H was exploited for a functional assay of putative bioC in the biotin auxotroph STL24 (ΔbioC) as a recipient strain. The resultant plasmids included (but are not limited to) the major three constructs of pBAD24::AbbioC, pBAD24::KpbioC, and pBAD24::BcbioC. It was noted that the version of pBAD24::SUMO-AbBioC was also created, which was designed to neutralize the potential toxicity of AbBioC overexpression (table S2). Second, unlike BcbioC that was dependent on pET28a to give solubility, AbbioC (and a number of its mutated variants) plus KpbioC were cloned into pET-SUMO that is a fusion expression vector with a SUMO tag at N terminus, giving a panel of recombinant plasmids, such as pET-SUMO::AbbioC and pET-SUMO::KpbioC (table S2). To prepare the apo-form of ACP (81), an additional enzyme of E. coli ACP phosphodiesterase (AcpH; b0404) was required because it essentially liberates Ppan from the residue serine-36 of ACP (82). Before the tag-free ACP production with pBAD24::acpP(b1094), pET28a::acpH(b0404) was created to give the N-terminal hexahistidine (6x His)–fused AcpH version (table S2) (82). B. subtilis Sfp (Ppan transferase)–encoding gene sfp was amplified with PCR and cloned into pET28a via homologous recombination, resulting in pET28a::sfp (83). The purified Sfp enzyme could convert Mal-ACP from apo-ACP in the presence of Mal-CoA (7). As for AbBioC reaction that ligates Mal-ACP with SAM to give M-Mal-ACP, the byproduct SAH was believed to interfere with the activity of BioC methyltransferase. The gene mtn/pfs(b0159) of E. coli was cloned to give a recombinant plasmid pET28a::mtn(b0159), of which protein product is 5′-methylthioadenosine(MTA)/SAH nucleosidase and eliminates the feedback inhibition by SAH (table S2) (76, 84). Using the method of homologous recombination, the four A. baumannii genes encoding putative biotinylated proteins [HKO16_10520 (AccB), HKO16_06425, HKO16_06925, and HKO16_15815] were obtained by PCR and introduced into pET28a via two restriction sites of Bam HI and Hind III (table S2). Third, the mobile colistin resistance determinant (mcr-1) was introduced into the constitutive expression vector pWSK129 (11, 80), producing the recombinant form of pWSK129::mcr-1 that was dedicated to resistance evaluation in K. pneumoniae (table S2). Fourth, the expression vector for A. baumannii, designated pΔCas9, was specifically developed through removing the Cas9 from the parental vector pCasAb-apr. The resultant pΔCas9 contained the unique multiple cloning sites, Eco RI at 5′-end and Hind III followed by a 6x His tag. This allowed us to generate the recombinant plasmids of pΔCas9::AbbioC, pΔCas9::KpbioC, and pΔCas9::mcr-1 (table S2).

To define extensive interaction of AbBioC with (i) its SAM cofactor (or SIN inhibitor) and (ii) Mal-ACP substrate, a collection of AbbioC mutants were produced using the site-directed mutagenesis with various pairs of specific primers like AbbioC(E50A)-F plus AbbioC(E50A)-R (table S3). As for these trials, all the three sets of recombinant plasmids (pBAD24::AbbioC, pΔCas9::AbbioC, and pET-SUMO::AbbioC) functioned as PCR templates accordingly. As a result, in total, 16 AbbioC mutants on each plasmid backbone were generated (table S2), including 12 single mutants [e.g., pBAD24::AbbioC(E50A), pΔCas9::AbbioC(E50A), and pET-SUMO::AbbioC(E50A)], 2 double mutants [i.e., pBAD24:: AbbioC (Q26A/Q116A) and pBAD24::AbbioC(K201A/R212A)], a triple mutant [such as pBAD24::AbbioC(K194A/K201A/R212A)], and a quadruple mutant [such as pBAD24::AbbioC(K194A/K201A/R212A/K215A)]. In addition, a deletion mutant of AbbioC(ΔN, 1-20) was engineered to evaluate a functional role of β1 sheet in AbBioC activity. Thus, it involved three constructs (table S2), namely, (i) pBAD24::AbbioC(ΔN,1-20), (ii) pΔCas9::AbbioC(ΔN,1-20), and (iii) pET-SUMO::AbbioC(ΔN,1-20). Along with routine PCR detection, all the acquired plasmids were validated by Sanger sequencing.

CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of A. baumannii bioC

As Wang and coworkers (33) established, the CRISPR-Cas9 system consisting of pCasAb-apr and pSGAb-km (table S2), was adopted to knockout the putative bioC gene from the chromosome of A. baumannii ATCC 17978. In principle, pCasAb-apr plasmid expresses both Cas9 nuclease and RecAb recombination system, and pSGAb-km produces sgRNA against the target gene (33). Of several sgRNA oligos for AbbioC that we designed, the optimal one that was annealed with the two complementary primers (AbbioC-sgRNA-F/R; table S3) was ligated into the pSGAb-km vector to obtain pSGBioC-sgRNA. Following the expression of Cas9 and RecAb induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), the A. baumannii ATCC 17978 that carries pCasAb-apr was prepared as competent cells, which were ready to receive pSGBioC-sgRNA plasmid along with the AbbioC repair template via an electroporation. Using two pairs of specific primers (AbbioC-Up400-F/R plus AbbioC-Dn400-F/R; table S3), the fusion PCR was performed to gain an AbbioC-targeting repair template [800 base pairs (bp)] that cover the two neighboring regions of AbbioC (400 bp each). The candidate ΔbioC mutants were screened with multiplex PCR assays and verified with direct DNA sequencing of PCR products. Next, the two plasmids of pCasAb-apr and pSGBioC-sgRNA were cured from the interested ΔbioC mutant by growth on LBA plates containing 10% sucrose (Shanghai Hushi Environmental Protection Reagent Technology Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China). The biotin auxotrophic phenotype of the resultant A. baumannii ΔbioC mutant, termed as FYJ6108 (table S1), was analyzed on biotin-lacking M9 minimal medium. Similarly, CRISPR-Cas9 manipulation enabled producing strain FYJ6184, i.e., the ΔbioC derivative of K. pneumoniae ATCC 43816 (table S1). A collection of genetically complemented strains of A. baumannii ΔbioC were obtained via an electroporation with appropriate pΔCas9-borne derivatives such as pΔCas9-AbBioC and pΔCas9-KpBioC (table S2). Similar to the recipient strain STL24 (ΔbioC) that carried a variety of pBAD24.8x His-borne AbbioC mutants, the complemented strains of A. baumannii ΔbioC with diverse pΔCas9-borne bioC derivatives were analyzed using growth curves and bacterial viability on the basis of the nonpermissive, biotin-deficient condition of M9 defined medium as described for the biotin requirement of E. coli (5, 29, 63) and P. aeruginosa PAO1 (24).

Genetic analyses for bioC homologs