Abstract

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC), the third most prevalent malignancy globally, can present with complications such as bleeding, obstruction, and, less commonly, perforation. These complications are associated with significant morbidity and mortality, demanding timely recognition and intervention. Unusual initial symptoms can obscure the clinical picture, delaying diagnosis, and treatment.

Case Presentation

We report a 50-year-old male with a history of rectosigmoid adenocarcinoma treated with surgery and chemoradiotherapy, presenting with atypical symptoms of intractable hiccups, watery diarrhea, and vomiting. Initial imaging indicated an ileostomy site perforation with signs of ischemic colitis. Exploratory laparotomy revealed a perforation at the splenic flexure, ischemic colitis, and a stenosing rectosigmoid tumor. A total colectomy with end ileostomy was performed, leading to resolution of symptoms and stabilization of the patient.

Conclusion

This case emphasizes the importance of recognizing atypical presentations of CRC and its complications. Prompt and comprehensive diagnostic evaluations followed by appropriate surgical intervention can improve outcomes and prevent further deterioration. Early recognition of unusual symptoms is critical in guiding effective management.

Keywords: Hiccups, Vomiting, Bowel perforation, Colorectal carcinoma, Rectosigmoid adenocarcinoma

Introduction

Intestinal perforation is a critical condition that can arise from various causes, such as trauma, ischemia, inflammation, instrumentations, malignancy, obstruction, and infections [1]. Intestinal content spillage leads to systemic signs and symptoms. Patients may feel abdominal pain or cramping, fever, chills, bloating or swollen abdomen, nausea, vomiting, pain or tenderness on touching the abdomen, and rarely hiccups [2, 3]. The main areas for GI tract perforation are the stomach, small intestine, appendix, large bowel, and rectum [2]. Colorectal cancer (CRC), the third most common cancer in the world’s population, accounts for 11% of all cancer diagnoses annually. If colon cancer is the only factor considered, the regions with the highest incidence are Southern Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and Northern Europe [4].

Given the high prevalence of colon cancer worldwide, it is reasonable to anticipate some complications that are directly related to the disease and call for immediate medical attention. Bleeding, blockage, and perforation are common consequences of colon cancer. Every third of CRC patients may experience one of these emergencies at any given time [5]. The most frequent cause of obstruction in the colon, with an incidence of 15%–29%, is local tumor growth [6]. Perforations, which have an overall incidence of 2.6%–12%, are the second most common complication of CRC [7]. Large bowel perforations are particularly concerning, with mortality rates ranging from 16.9% to 19.6%. Timely and accurate diagnosis is crucial for reducing mortality and morbidity associated with intestinal perforations [8]. Surgical emergency management is typically required for GI tract perforations, emphasizing the significance of early diagnosis and treatment [8].

We present here a rare case study of a 50-year-old male with hiccups and vomiting, diagnosed with large intestine perforation at the ileostomy site via computerized tomography (CT) scan. However, on laparoscopy and exploratory laparotomy, ischemic colitis, gut perforation in the area of the splenic flexure, stenosing rectosigmoid tumor with proximal dilatation of the cecum, ascending, transverse, and descending colon till the rectosigmoid junction were noted, which highlights the importance of prompt identification, extension of diagnostic procedures from non-invasive to invasive, and intervention in such cases.

Case Presentation

A 50-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a 13-day history of intractable hiccups along with watery diarrhea seen through the ileostomy bag. He also had several episodes of non-projectile and non-bilious vomiting, containing food particles. He had a past medical history of rectosigmoid adenocarcinoma, post-surgical loop ileostomy and post-chemoradiotherapy CAPOX cycle 8/8 completed a month ago. He recently visited the emergency department for similar episodes of diarrhea and vomiting, and was prescribed with metoclopramide and baclofen, which did not improve his symptoms. The patient did not report any abdominal pain or fever. Upon abdominal examination, there was no tenderness or bloating.

Upon presenting to the emergency department, he was vitally stable with a heart rate of 119 bpm, blood pressure 120/82 mm Hg, temperature 36.9°C, and oxygen saturation 96% in room air. The initial baseline investigations are mentioned in Table 1. An erect X-ray of the abdomen demonstrated a few dilated bowel loops within the central abdomen (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Baseline laboratory investigation

| Investigations | Value | Reference range |

|---|---|---|

| White blood cell count | 4.47 K/µL | 4.80–10.80 K/µL |

| Hemoglobin | 10.5 | 14.0–18.0 g/dL |

| Platelet count | 134 | 130–400 k/µL |

| Sodium (serum) | 124 | 135–146 mmol/L |

| Potassium | 4.12 | 3.7–5.1 mmol/L |

| Urea nitrogen | 14.2 | 6–20 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 0.5 | 0.70–1.20 mg/dL |

| ALT | 6 | <42 U/L |

| AST | 12.7 | <41 U/L |

| ALP | 120 | 40–129 U/L |

| Serum osmolarity | 275.3 | 275–295 mOsm/kg |

| Sodium urine | 20 | 54–190 mmol/L |

| Osmolality urine | 350.2 | 50–1,200 mmol/L |

ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase.

Fig. 1.

Erect X-ray of the abdomen with dilated bowel loops.

He was subsequently admitted for the workup of hyponatremia and to rule out subacute bowel obstruction. The patient was started with intravenous (IV) metoclopramide, prochlorperazine for hiccups, baclofen, and IV normal saline. The next day, hyponatremia improved to 131, but he could not eat or drink due to intractable hiccups.

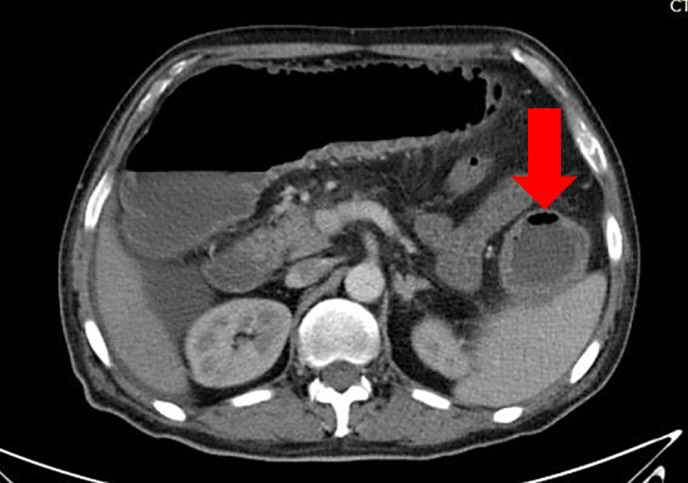

CT with oral contrast of the abdomen was planned to evaluate the cause of the symptoms. CT showed reduced bowel enhancement in bowel walls in the right iliac fossa along the ileostomy site with extraluminal gas (image), likely due to perforation. There was the impression of a speck of gas in mesenteric vessels and thickening of bowel loops. These features are suggestive of developing ischemic colitis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Computerized tomography with contrast showed an impression of reduced bowel enhancement in bowel walls in the right iliac fossa.

The patient was referred to the surgical team, which opted to proceed with a laparoscopy. Later, the decision was taken to convert it to exploratory laparotomy.

During laparotomy, there was ischemic colitis, gut perforation in the area of splenic flexure, stenosing rectosigmoid tumor with proximal dilatation of cecum, ascending, transverse, and descending colon extending to rectosigmoid junction. So, exploratory laparotomy and total colectomy with end ileostomy was performed. Irresectable mass at the level of bifurcation of the aorta was found, and dissection was performed above that. A small bowel distal to the ileostomy was transected, and the specimen was retrieved. Ascitic fluid was taken for culture, which was negative.

The patient was shifted to the post-surgical care unit. The patient improved clinically and his hiccups resolved. He had no post-surgical complications and was discharged with regular follow-ups.

Discussion

CRC, the third most common cancer in the world’s population, accounts for 11% of all cancer diagnoses annually [4]. Bleeding, blockage, and perforation are expected consequences of colon cancer. Every third of CRC patients may experience one of these emergencies at any given time [5]. One prognostic factor for the incidence and mortality of the disease has been identified as its clinical manifestation [9]. Improving the prognosis of patients may require early diagnosis and aggressive surgical treatment. Perforations, which have an overall incidence of 2.6%–12%, are the second most common complication of CRC [10]. Perforations most frequently occur because of the necrosis and friable tissue at the primary tumor site. These can develop into contained or free perforations, depending on the location. Additionally, perforation may happen close to an obstructing carcinoma. The most typical area for this kind of diastatic perforation is the cecum [9].

We present here a rare case study of a 50-year-old male with hiccups and vomiting, diagnosed with large intestine perforation at the ileostomy site via CT scan. Exploratory laparotomy was performed, which showed ischemic colitis, gut perforation in the area of splenic flexure, stenosing rectosigmoid tumor with proximal dilatation of cecum, ascending, transverse, and descending colon till rectosigmoid junction, so total colectomy with end ileostomy was performed. This highlights the importance of quick identification, extension of diagnostic procedures from non-invasive to invasive, and timely intervention in such cases. Shang Zhi Han examined three patients who had colon cancer-related abscess perforations and discovered that the tumor lesions were in the right colon [11]. However, in our case, the perforation was on the left side due to a rectosigmoid tumor.

A study by Wasanwala and Neychev shows a rare case of a 51-year-old female who had perforated colon cancer with concurrent diverticulosis. The patient was diagnosed with acute complicated diverticulitis based on the history, physical examination, laboratory results, and CT findings at the initial presentation. The patient’s condition deteriorated in spite of medical attention, necessitating a transverse end colostomy and an exploratory laparotomy along with a left hemicolectomy. The surgical pathology report showed no signs of diverticulitis and stage III-C colon cancer. Eight cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy using FOLFOX (folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin) were administered to the patient. The patient had multiple surgeries due to recurrent bowel perforations during the course of the following year. At different times, perforations in the large and small bowel were found. Though neither had a distinct cause, ischemic, infectious, erosive, and iatrogenic etiologies were among the possibilities [12].

Perforation is reported to be the most lethal complication of colorectal carcinoma. Mortality associated with secondary peritonitis from perforation is as high as 30%–50% [9]. In 2.4–12% of typical colorectal surgery cases, anastomotic leakage is a severe and frequently fatal complication. On the other hand, it occurs much more frequently in patients who have colorectal perforation. Nevertheless, the patient in this instance had a large bowel perforation at the splenic flexure as a result of a stenosing rectosigmoid tumor and ischemic colitis [10].

The patient case study by Xiang et al. [13] experienced a localized abscess perforation. The colon cancer diagnosis came 1.5 years after treatment for intestinal leakage, the longest time between diagnosis and onset documented in the literature. On-time diagnoses and imaging are essential. The imaging modality for patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of colonic obstruction is CT. With 96% sensitivity and 93% specificity, it can accurately locate an obstructing lesion and is widely accessible in emergency rooms [14]. Nearly 89% of cases can be successfully diagnosed with CT, mainly when a triple-contrast protocol (oral, rectal, and IV) is used [14]. In our case, the patient presented with complications of perforation and colitis. CT scans, colonoscopy, and laparoscopy should be performed as needed to accurately stage the disease and ensure timely treatment.

Nikolovski et al. [15] reported a case of descending colon cancer in a female patient who initially presented with large bowel obstruction, a retroperitoneal lumbar abscess, and perforation at the tumor site. The incidence of dual complications, such as obstruction and perforation, is reported to be 1.7%. It is uncommon for more than one of the aforementioned CRC complications to occur simultaneously. However, in our case, there was a perforation without bowel obstruction at the time of presentation, which was diagnosed after laparotomy. Colon and rectal cancers can spontaneously perforate when the tumors are advanced or when the disease has been ignored and treated for a long time. High death rates are caused by tumor cells and feces that leak into the abdominal cavity through perforated bowel loops. Therefore, surgery is required for these patients. Multi-step surgeries involving protective ileostomy and anastomosis lower postoperative mortality rates in resected cases [16].

Conclusion

The case report concludes by highlighting the difficulties in identifying and treating ischemic colitis in a patient who has had cancer and previous medical interventions. The 50-year-old man arrived with vomiting, watery diarrhea, and intractable hiccups. Upon initial examination, hyponatremia and early indications of ischemic colitis were found. Additional imaging revealed bowel wall abnormalities and a perforation, requiring an exploratory laparotomy. Following a total colectomy with end ileostomy, the operation revealed ischemic colitis, a stenosing rectosigmoid tumor, and a perforation of the gut. The patient’s hiccups were resolved, and he was stabilized after the procedure, which effectively addressed the complications. The patient’s outcome was favorable due to the timely and appropriate care provided. However, ensuring the patient’s long-term health and addressing any potential complications from the underlying conditions will require continuous monitoring and follow-up care. The CARE Checklist has been completed by the authors for this case report, attached as online supplementary material (for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000542603).

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge the Qatar National Library (QNL) for open access publication funding of this article.

Statement of Ethics

The Medical Research Center at Hamad Medical Corporation in Qatar has granted approval for the publication of this case report under the reference no. MRC-04-24-457. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the details of their medical case and any accompanying images.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

Funding Sources

This case report was not funded.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and data curation: Abdul Qadir and Hafsah Iqbal. Writing – original draft: Abdul Qadir, Hafsah Iqbal, and Ayesha Sabir. Writing – review and editing: Abdul Qadir, Hafsah Iqbal, Ayesha Sabir, Osama bin Khalid, and Jamal Sajid. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding Statement

This case report was not funded.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the finding of this case report are contained within the article. Additional information is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with the approval of relevant Ethics Committee.

Supplementary Material.

References

- 1. Grotelüschen R, Bergmann W, Welte MN, Reeh M, Izbicki JR, Bachmann K. What predicts the outcome in patients with intestinal ischemia? A single center experience. J Visc Surg. 2019;156(5):405–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kothari K, Friedman B, Grimaldi GM, Hines JJ. Nontraumatic large bowel perforation: spectrum of etiologies and CT findings. Radiol. 2017;42(11):2597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chhoun C, Joo L, Blair B, Khalid Y, Dasu N, Patel R. Intestinal perforations IN patients with ibd: an analysis OF the national inpatient sample 2015-2019. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29(Suppl ment_1):S73. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barnett A, Cedar A, Siddiqui F, Herzig D, Fowlkes E, Thomas CR Jr. Colorectal cancer emergencies. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2013;44(2):132–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ohman U. Prognosis in patients with obstructing colorectal carcinoma. Am J Surg. 1982;143(6):742–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Larsson B, Perbeck L. The possible advantage of keeping the uterine and intestinal serosa irrigated with saline to prevent intraabdominal adhesions in operations for fertility. An experimental study in rats. Acta Chir Scand Suppl. 1986;530:15–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Long B, Robertson J, Koyfman A. Emergency medicine evaluation and management of small bowel obstruction: evidence-based recommendations. J Emerg Med. 2019;56(2):166–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baer C, Menon R, Bastawrous S, Bastawrous A. Emergency presentations of colorectal cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2017;97(3):529–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Asano H, Fukano H, Ohara Y, Shinozuka N. Suitability of primary anastomosis for colorectal perforation. SN Compr Clin Med. 2019;1(2):99–103. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Han SZ, Wang R, Wen KM. Delayed diagnosis of ascending colon mucinous adenocarcinoma with local abscess as primary manifestation: report of three cases. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9(26):7901–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wasanwala H, Neychev V. Perforated colon cancer associated with postoperative recurrent bowel perforations. Cureus. 2021;13(9):e17655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xiang D, Fu G, Chen Y, Chu X. Case report: POLE (P286R) mutation in a case of recurrent intestinal leakage and its treatment. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1028179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Frago R, Ramirez E, Millan M, Kreisler E, del Valle E, Biondo S. Current management of acute malignant large bowel obstruction: a systematic review. Am J Surg. 2014;207(1):127–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nikolovski A, Limani N, Lazarova A, Tahir S. Synchronous onset of two complications in colon cancer: a case report. J Med Cases. 2021;12(6):248–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gök MA, Kafadar MT, Yeğen SF. Perforated colorectal cancers: clinical outcomes of 18 patients who underwent emergency surgery. Prz Gastroenterol. 2021;16(2):161–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the finding of this case report are contained within the article. Additional information is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with the approval of relevant Ethics Committee.