Abstract

Fe(II)- and 2-oxoglutarate (2OG)-dependent dioxygenases use 2OG and O2 cofactors to catalyse substrate oxidation and yield oxidised product, succinate, and CO2. Simultaneous detection of substrate and cofactors is difficult, contributing to a poor understanding of the dynamics between substrate oxidation and 2OG decarboxylation activities. Here, we profile 5-methylcytosine (5mC)-oxidising Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET) enzymes using MS and 1H NMR spectroscopy methods and reveal a high degree of substrate oxidation-independent 2OG turnover under a range of conditions. 2OG decarboxylase activity is substantial (>20% 2OG turned over after 1 h) in the absence of substrate, while, under substrate-saturating conditions, half of total 2OG consumption is uncoupled from substrate oxidation. 2OG kinetics are affected by substrate and non-substrate DNA oligomers, and the sequence-agnostic effects are observed in amoeboflagellate Naegleria gruberi NgTet1 and human TET2. TET inhibitors also alter uncoupled 2OG kinetics, highlighting the potential effect of 2OG dioxygenase inhibitors on the intracellular balance of 2OG/succinate.

Subject terms: Enzyme mechanisms, Bioanalytical chemistry, Nucleic acids, Oxidoreductases

The ten-eleven translocation (TET) dioxygenase subfamily catalyse the sequential oxidation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) in DNA and belong to the Fe(II)-/2-oxoglutarate (2OG)-dependent dioxygenases that use 2OG and O2 cofactors to yield succinate and CO2. Here, the authors profile the TET-catalysed 5mC DNA oxidation and 2OG decarboxylation using MS and 1H NMR spectroscopy methods, revealing a high degree of substrate oxidation-independent 2OG turnover in TETs.

Introduction

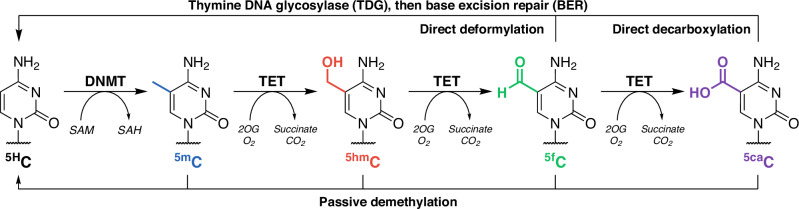

Fe(II)- and 2-oxoglutarate (2OG)-dependent dioxygenases constitute a diverse superfamily of enzymes involved in a wide variety of biological functions, including epigenetic regulation, collagen biosynthesis, and oxygen sensing1. The Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET) dioxygenase subfamily catalyses the sequential oxidation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and 5-carboxycytosine (5caC) using 2OG and O2 as co-substrates and releasing succinate and CO2 as by-products (Fig. 1)2,3.

Fig. 1. Pathways of dynamic cytosine modifications.

Cytosine (5HC) is methylated by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) to produce 5mC, which can be iteratively oxidised to 5hmC, 5fC, and 5caC by TETs in an Fe(II)/2OG-dependent manner3. 5fC and 5caC can be replaced with 5HC via passive demethylation, TDG/BER mechanisms4, direct deformylation46, or decarboxylation47,48.

Unmodified cytosine (5HC) can be regenerated by a combination of thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG) activity on bases 5fC and 5caC followed by base excision repair (BER) mechanisms4. Cytosine methylation occurs predominantly on cytosine-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides, with up to 80% of genomic CpG sites methylated in mammals5. Correspondingly, TET DNA oxidation activity depends heavily on the sequence context of the modified cytosine (5xC) with a strong preference for 5xCpG dinucleotides, demonstrating a high degree of epigenetic synergy, although flanking nucleotides in positions −3 to +2 (relative to 5xC) also affect activity6–8. Furthermore, while CpG methylation at gene promoter regions is commonly associated with transcriptional silencing9, hydroxymethylation is predictive of poised chromatin10. In these ways, TETs play key epigenetic roles in developmental processes such as pre-implantation development11, genomic imprinting erasure12, and pluripotency regulation13,14. Accordingly, TET dysfunction is implicated in numerous oncological diseases. Decreased TET protein and 5hmC levels are associated with human breast, liver, lung, pancreatic, and prostate cancers15, while TET2 loss-of-function mutations are prevalent in haematopoietic malignancies16. Substrate oxidation by Fe(II)/2OG-dependent dioxygenases is stoichiometrically linked to 2OG consumption. Oxidative decarboxylation of 2OG to succinate is a requisite for the formation of the reactive Fe(IV)-oxo complex17, but 2OG turnover can also take place in the absence of the associated substrate, resulting in uncoupled 2OG decarboxylation. Such activity has been observed in a number of 2OG dioxygenase subfamilies, including histone lysine demethylases (KDMs)18, prolyl/lysyl hydroxylases19–21, and DNA repair enzymes AlkB22,23, with uncoupled 2OG turnover rates reaching up to 10% of rates observed under substrate-saturating conditions. Uncoupled 2OG turnover has been observed in TET123, but limited data is available on the interplay between TET DNA oxidation and 2OG decarboxylase activity, as to-date biochemical characterisation of TETs almost exclusively utilises MS6,24–28 or antibody-based29–32 methods for the detection of DNA substrate oxidation. Here, we describe the concurrent profiling of DNA substrate oxidation and 2OG decarboxylation by TETs using MS and 1H NMR spectroscopy methods. While substrate oxidation and 2OG decarboxylation were coupled as expected, we observed that TETs exhibited unusually high levels of uncoupled 2OG decarboxylation, which were reduced by 2OG competitive inhibitors, or enhanced in the presence of non-substrate oligonucleotides and substrate-competitive TET inhibitors.

Results

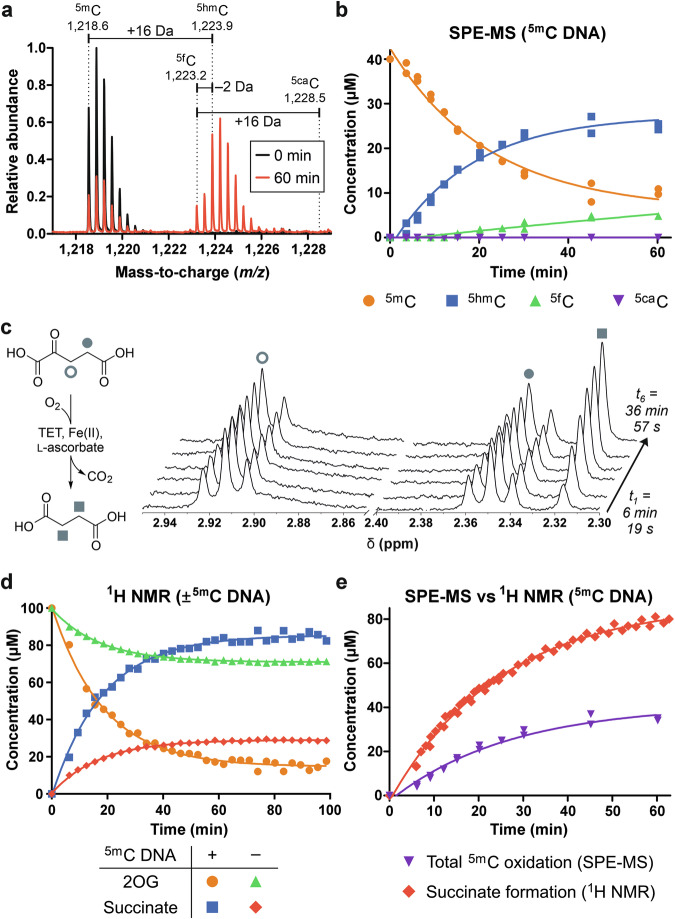

Characterisation of recombinant NgTet1

Human TETs are large (180–230 kDa) multidomain proteins with high structural complexity. Production of full-length recombinant human TETs is challenging and typically requires substantial construct modification (truncation and/or deletion) which may affect substrate oxidation and 2OG turnover dynamics. Thus, a 38 kDa TET homologue from amoeboflagellate Naegleria gruberi (NgTet1) was selected as a model enzyme for this work26. Full-length NgTet1 was recombinantly expressed and purified from E. coli (Figure. S1) and catalytic activity was confirmed using solid-phase extraction-mass spectrometry (SPE-MS)-based assay33,34. Successive oxidation of methylated DNA (double-stranded, self-complementary 5'-ACC AC5mC GGT GGT-3' [5mC DNA], 5mCpG-containing sequence reported as a human TET substrate24,33) to 5hmC and 5fC was observed in the presence of l-ascorbate, Fe(II), and 2OG (Fig. 2a, b). 5caC was not detected after 60 min under the assay conditions tested. 5mC DNA substrate KMapp was measured to be 2 µM (Figure. S2).

Fig. 2. Continuous monitoring of NgTet1 5mC hydroxylase and 2OG decarboxylase activity using SPE-MS and 1H NMR assays.

a Representative spectra for selected SPE-MS assay time points with oligonucleotides observed in the [M − 3H]3– charge state (black, 0 min; red, 60 min). b SPE-MS 5mC DNA oxidation time course (single DNA strand analyte concentrations reported). c Representative spectra for selected 1H NMR assay time points (no DNA). d 1H NMR 2OG decarboxylation time courses in the presence and absence of 5mC DNA substrate. e Time courses of total 5mC oxidation (5hmC and 5fC production) by SPE-MS and 2OG consumption by 1H NMR under DNA substrate-saturating conditions (20 µM 5mC DNA). Standard conditions: 5 μM NgTet1, 2 mM ascorbate, 100 μM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2, 100 μM (d) or 200 μM (b, e) 2OG. Data in b and e plotted from two independent replicates (n = 2); 1H NMR data in d shown as representative curves of two independent replicates.

To investigate the 2OG decarboxylation kinetics of the TETs, a reported 1H NMR spectroscopy assay to directly quantify succinate formation for 2OG dioxygenases was adapted18. Initially, NgTet1 was incubated with l-ascorbate, Fe(II), and 2OG and analysed by 1H NMR spectroscopy, which revealed substantial succinate production over time, indicating uncoupled 2OG turnover in the absence of DNA substrate (Fig. 2c, d). The rate of succinate production was found to be negligible in control experiments when NgTet1 or any of the co-factors were removed (Table S1), indicating that the observed activity was enzymatic, and not due to chemical 2OG decarboxylation pathways, such as ascorbate-mediated succinate formation via a H2O2 intermediate35. Ascorbate was essential for 2OG decarboxylase activity, consistent with reports on other 2OG hydroxylases (Table S1)36,37. In the presence of saturating concentrations of substrate 5mC DNA (20 µM, 10 × KMapp), the rate of 2OG consumption increased, as expected for a combination of substrate-coupled and -uncoupled 2OG turnover (Fig. 2d). However, simultaneous reaction analysis by 1H NMR and SPE-MS methods under DNA substrate-saturating conditions revealed that 2OG decarboxylation took place at a substantially faster rate than 5mC oxidation (Fig. 2e). Under our assay conditions, after 20 min, ~7.2 nmoles of 2OG had been consumed to oxidise 3.5 nmoles of substrate (a combination of 5mC and 5hmC DNA substrates), demonstrating poor 2OG decarboxylation coupling even under DNA substrate-saturating conditions.

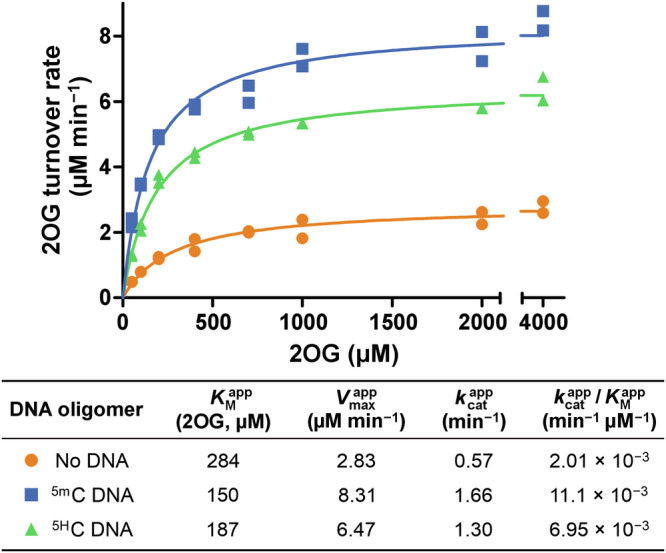

2OG decarboxylation kinetics of NgTet1

Next, 2OG kinetic parameters were compared in the presence and absence of substrate-saturating conditions using 1H NMR (Fig. 3). Substrate saturation decreased the 2OG KMapp nearly 2-fold (284 to 150 μM), enhanced the maximum 2OG decarboxylation rate 3-fold (Vmaxapp = 2.83 to 8.31 μM min–1), and increased the apparent catalytic efficiency 5-fold (kcatapp/KMapp = 0.00201 to 0.0111 min−1 μM−1). Addition of non-methylated DNA of the same sequence (5HC DNA, 5'-ACC ACC GGT GGT-3') produced a comparable effect on 2OG turnover to 5mC substrate-saturating conditions, but 5HC DNA did not undergo enzymatic oxidation (Figure. S4), confirming that it is not a TET substrate. Thus, 2OG decarboxylation kinetics are regulated by both substrate 5mC DNA and corresponding non-substrate 5HC DNA, suggesting that enzyme–DNA complex formation leads to enhanced 2OG decarboxylation independent of substrate oxidation.

Fig. 3. Michaelis-Menten enzyme kinetics plots and corresponding apparent kinetic parameters for 2OG decarboxylation by NgTet1 using 1H NMR assay.

Standard conditions: 5 μM NgTet1, 2 mM ascorbate, 100 μM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2, 0–4,000 μM 2OG. Double-stranded 12 bp DNA oligomers were added at a final concentration of 20 µM. Data plotted from two independent replicates (n = 2). See Figure. S3 for a 1H NMR 2OG decarboxylation time course in the presence of 5HC DNA.

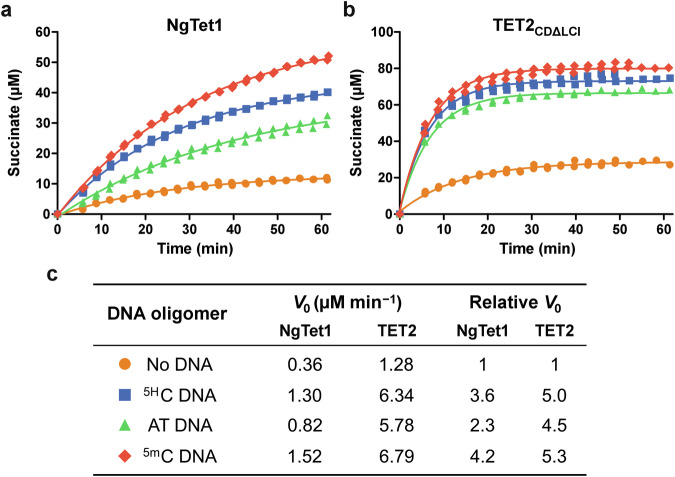

To determine if the stimulation of 2OG decarboxylase activity by non-substrate DNA was sequence-specific and contingent on the presence of a CpG site, the central CpG motif in 5HC DNA was substituted for ApT (AT DNA, double-stranded self-complementary 5'-ACC ACA TGT GGT-3'). Addition of AT DNA improved the initial 2OG turnover rate 2.3-fold compared to no DNA conditions, although 5HC DNA and 5mC DNA were more efficient at accelerating 2OG decarboxylation, producing 3.6- and 4.2-fold enhancements, respectively (Fig. 4a, c). All three DNA oligomers exhibited comparable binding affinities in an AlphaScreen competition assay with a biotinylated 5mC-containing dsDNA oligomer (Figure. S5, NgTet1 IC50 = 56–60 µM). Reported crystal structures of NgTet1 and TET2CDΔLCI reveal positively charged DNA-interacting patches proximal to their active sites24,26, supporting interactions with the DNA phosphate backbone rather than recognition of specific bases as the primary driver of binding. Thus, while the degree of 2OG decarboxylation activation appears to be oligonucleotide sequence-specific, affinity of complexes between TET and DNA oligomers seems to be sequence-agnostic.

Fig. 4. Comparison of TET 2OG decarboxylase activity in the absence of DNA, with 5HC, AT, and 5mC DNA using 1H NMR.

a NgTet1 activity curves. b TET2CDΔLCI activity curves. c Tabulated initial reaction rates (V0) and relative V0 to reactions without DNA. Standard conditions: 5 μM NgTet1 or TET2CDΔLCI, 2 mM ascorbate, 100 μM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2, 100 μM 2OG. Double-stranded DNA oligomers were added at a final concentration of 20 µM. Data plotted from two independent replicates (n = 2). Initial rates reported as the mean of two independent replicates (n = 2).

Comparison of NgTet1 and TET2 activity

To investigate the 2OG decarboxylase activity of human TETs, a truncated TET2 catalytic domain construct24 (TET2CDΔLCI) was recombinantly produced from E. coli (Figure. S6), and the same 5mC DNA, a reported24 substrate of TET2CDΔLCI (KM = 1 µM, kcatapp = 0.3 min−1)33, was used. As with NgTet1, 2OG turnover was observed in the absence of DNA substrate and the rate was enhanced by addition of 5mC substrate DNA and non-substrate DNA (5HC and AT DNA) (Fig. 4b). However, the rates were less dependent on the oligonucleotide identity for TET2 than in the case of NgTet1, with all three oligonucleotides enhancing initial reaction rates to a similar extent (Fig. 4b, c). While the TET2 binding affinities of all three DNA oligomers were comparable, as in the case of NgTet1 (Figure. S5, TET2CDΔLCI IC50 = 4.6–8.9 µM), the observed differences between NgTet1 and TET2 may be partially attributed to discrete DNA sequence preferences and affinities within the TET family6–8,25; a direct comparison would require the identification of optimal substrate sequences for each TET protein. Further investigation is required to determine the biological relevance of full-length TET2 2OG decarboxylase activity, as the non-catalytic domains absent from TET2CDΔLCI may affect enzyme specificity and coupling of 2OG turnover24.

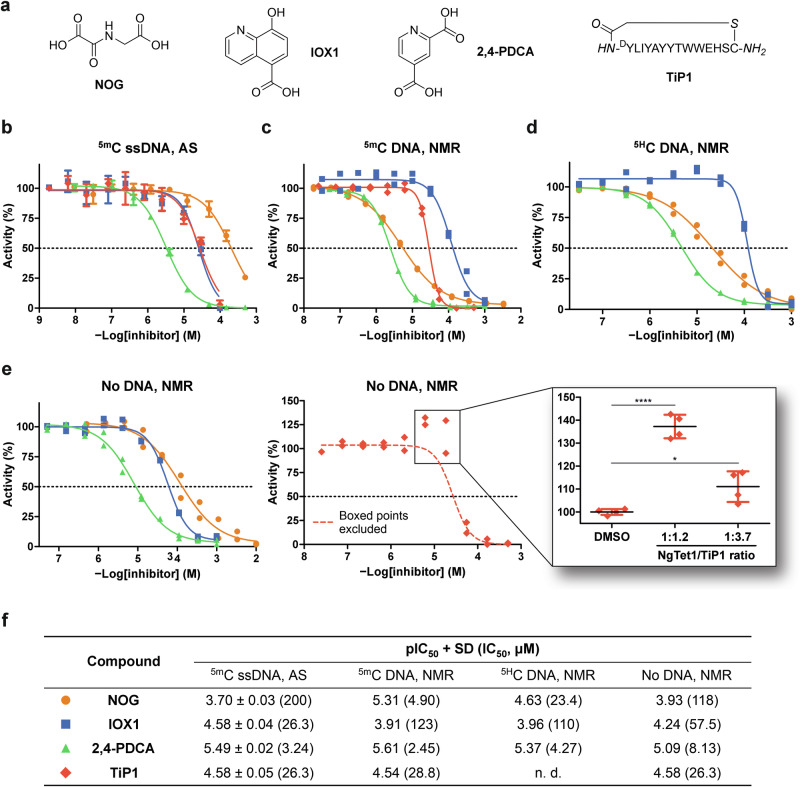

Characterisation of TET inhibitors

Next, the effects of 2OG oxygenase inhibitors on 2OG decarboxylation rates were explored. Known inhibitors of TET 5mC hydroxylase activity, including three pan-specific 2OG mimetics (N-oxalylglycine (NOG)38, 5-carboxy-8-hydroxyquinoline (IOX1)39, and 2,4-pyridinedicarboxylic acid (2,4-PDCA)40) and thioether macrocyclic peptide TiP132 (Fig. 5a), were screened for inhibitory activity against NgTet1. Inhibition of 5mC hydroxylase activity was evaluated using a reported chemical luminescence and anti-5hmC antibody-based AlphaScreen (AS) assay32 with 5mC ssDNA (single-stranded 32 mer 5’-[Biotin]-TCG GAT GTT GTG GGT CAG 5mCGC ATG ATA GTG TA-3' reported as an NgTet1 substrate26). 2OG mimetics exhibited a range of micromolar potencies (AS IC50 = 3–200 µM, Fig. 5b, f), although IOX1 and NOG inhibited NgTet1 to a lesser degree than human paralogues33.

Fig. 5. Dual characterisation of inhibitors against NgTet1.

a Structures of characterised inhibitors (italicised letters in cyclic peptide TiP1 represent individual atoms). Representative dose-response curves for inhibition of NgTet1-catalysed 5mC ssDNA oxidation (b) using AlphaScreen and 2OG decarboxylation (c) with 5mC DNA, (d) with 5HC DNA, and (e) with no DNA using 1H NMR. f Tabulated pIC50 and IC50 values. Statistical significance of NgTet1 activation (e inset, n = 4 technical replicates, two-tailed unpaired t test): ****p ≤ 0.0001; *p = 0.017. e inset data collected separately from TiP1 dose-response curve data. Curve fitting and pIC50 determination for TiP1 in e were carried out excluding the boxed outliers. Activity was normalised against reactions containing vehicle (DMSO). Standard conditions: 400 nM NgTet1, 10 nM 5mC ssDNA, 100 μM ascorbate, 10 μM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2, 10 μM 2OG (AS); 5 μM NgTet1, 0/20 µM 5mC or 5HC DNA, 2 mM ascorbate, 100 μM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2, 50 μM 2OG (1H NMR). AS data shown as the mean of three experimental replicates (n = 3; mean ± SD); 1H NMR data plotted from two independent replicates (n = 2); tabulated data reported as the mean of two and three independent replicates for 1H NMR and AS, respectively (n = 2–3, SD reported for n = 3). N. d.: not determined; AS: AlphaScreen.

In parallel, inhibition of 2OG decarboxylase activity was evaluated using 1H NMR assay. Under 5mC DNA substrate-saturating conditions (mixed 2OG turnover), the potency of NOG, an isostere of 2OG, improved 40-fold relative to AS assay, while IOX1 potency decreased 5-fold, demonstrating that 2OG competitive inhibitor potencies can be differentially affected by different assays and assay conditions, such as DNA substrate sequence and concentration (Fig. 5c). In the presence of non-substrate 5HC DNA (uncoupled 2OG turnover), NOG potency was reduced 5-fold, whereas IOX1 and 2,4-PDCA only showed slight potency changes (<2-fold) (Fig. 5d). In the absence of any DNA (uncoupled 2OG turnover), inhibitory potencies were comparable to 5mC ssDNA-based AS assay results (NMR IC50 = 8–118 µM, Fig. 5e). While the potency of small molecule 2OG mimetics varied substantially depending on the assay, TiP1 potency was consistent across all assays (IC50 = 26–29 µM). An increase in uncoupled 2OG decarboxylation activity was observed when approaching 1:1 stoichiometry between NgTet1 and cyclic peptide TiP1 in the absence of DNA oligomers. At 1:1.2 and 1:3.7 ratios of NgTet1 to TiP1 (5 µM NgTet1), TiP1 stimulated 2OG turnover in a statistically significant manner (Fig. 5e inset), although further titration of TiP1 resulted in activity inhibition. MALDI-TOF MS analysis of the reaction after quenching revealed no changes to TiP1 (Figure. S7), demonstrating that the catalytic activity enhancement was not due to the recognition of TiP1 as substrate. At 1:1.2 stoichiometry of NgTet1/TiP1, TiP1 increased the maximal 2OG turnover velocity 2-fold while reducing 2OG affinity proportionally (Figure. S8); for comparison, 5HC DNA increased both Vmax and 2OG affinity (Fig. 3). Accordingly, 5HC DNA was a more potent stimulator of uncoupled 2OG decarboxylase activity than TiP1, with 188% and 137% activity observed at 1.2 equivalents of 5HC DNA and TiP1, respectively (Figure. S9). TiP1 did not enhance 2OG decarboxylase activity in the presence of DNA substrate, potentially indicating mutual binding exclusivity of TiP1 and DNA oligomers. Similarly, in the absence of substrate, substrate competitors elevated 2OG turnover rates in prolyl hydroxylases19,41, suggesting an analogous substrate-competitive mechanism of action for TiP1.

Discussion

Overall, analysis of TET DNA oxidation and 2OG decarboxylase activities using 1H NMR and SPE-MS assays provided insight into the interplay between substrate coupled and uncoupled catalytic activity. Our work highlights the unusually poor control of 2OG decarboxylation coupling to substrate oxidation in TETs, in line with the trends observed in uncoupled decarboxylation across 2OG oxygenases using a bioluminescent succinate detection assay23. While the biological relevance of the high levels of uncoupled 2OG turnover in TETs is unclear, it suggests potential secondary roles for TETs beyond DNA oxidation/demethylation, such as modulation of TCA cycle intermediate levels (i.e., 2OG and succinate). This could have wide-ranging implications, including modulation of local intracellular 2OG dioxygenase activity, which can be inhibited by high levels of succinate42–44. Notably, the uncoupled 2OG consumption rates of TETs were further enhanced upon binding to substrate and non-substrate DNA, in both CpG and non-CpG contexts. While NgTet1 was used in this study as a model system for detailed TET kinetics, human TET2 showed similar trends, demonstrating that 2OG decarboxylase activity is strongly affected by oligonucleotide binding.

Development of a 1H NMR assay also enabled the study of the effect of TET inhibitors on coupled and uncoupled 2OG turnover rates. Inhibitor potencies were largely dependent on assay conditions in the case of 2OG mimetics NOG, IOX1, and 2,4-PDCA, but not macrocyclic peptide TiP1, indicating that 2OG competitive small molecules can differentially inhibit the rates of substrate oxidation and coupled/uncoupled 2OG turnover by TETs. Notably, TiP1 enhanced 2OG decarboxylase activity in the absence of DNA oligomers, mimicking the effects of oligonucleotide binding. 2OG competitive inhibitors or substrate competitive TET ligands, such as oligonucleotides or inhibitors, can thus influence the uncoupled 2OG decarboxylation rates, which may result in previously underappreciated changes to the balance of intracellular 2OG/succinate levels. Given the central role of TETs in epigenetic regulation and the observed TET dysregulation in multiple diseases, our results suggest that further investigation into the cellular effects of TET activity beyond 5mC oxidation and the resulting epigenetic consequences would be of particular interest.

Methods

Recombinant NgTet1 production

A pET-28 vector containing a gene coding for N–terminally His6-tagged full-length Naegleria gruberi NgTet1 (321 a. a.) protein with a thrombin cleavage site was expressed in E. coli as reported with slight modifications26. Cultures were grown at 37 °C in 2× TY medium (1.6% w/v tryptone, 1% w/v yeast extract, 0.5% w/v NaCl) to OD600 0.8, when the temperature was reduced to 16 °C and isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, 0.5 mM) was added to induce expression (18 h). Cells were harvested (7741 × g, 4 °C, 20 min) and stored at −80 °C. The cells were thawed and re-suspended in 4 volumes of 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 0.5 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), 0.1% v/v Benzonase®, and 1× Calbiochem® protease inhibitor cocktail set III (EDTA-free) and lysed using sonication. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation (63,988 × g, 4 °C, 30 min). His6-tagged NgTet1 was captured from the lysate supernatant using Ni affinity chromatography (HisTrap HP) and further purified by size exclusion chromatography (Superdex® 75) in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM TCEP. The purified protein was stored at a concentration of 18 mg mL−1 in gel filtration buffer.

Recombinant TET2CDΔLCI production

A modified pET-28b vector containing a gene coding for the catalytic domain of TET2 (TET2CD) with an insertion-deletion at the low complexity insert region (LCI, residues 1129–1936, with residues 1481–1843 replaced with linker GGGGSGGGGSGGGGS) fused to an N–terminal His6-FLAG-[thrombin cleavage site]-SUMO tag was expressed in E. coli based on the reported procedure24. Cultures were grown at 37 °C in TB medium (2% w/v tryptone, 2.4% w/v yeast extract, 0.4% v/v glycerol, 24.6 mM KH2PO4, 75.4 mM K2HPO4 [pH 7.4]) to OD600 1.0, when the temperature was reduced to 16 °C and IPTG (0.5 mM) was added to induce expression (18 h). Cells were harvested (7741 × g, 4 °C, 20 min) and stored at −80 °C. The cells were thawed and re-suspended in 5 volumes of 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 0.5 mM TCEP, 0.1% v/v Benzonase®, and 1× Calbiochem® protease inhibitor cocktail set III (EDTA-free) and lysed using high-pressure homogenisation. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation (63,988 × g, 4 °C, 30 min). His6-tagged TET2CDΔLCI fusion was captured from the lysate supernatant using Ni affinity chromatography (HisTrap HP). The captured protein was dialysed into low-imidazole buffer (20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole), and the fusion tag was removed by treatment with Ulp1 protease at 4 °C for 16 h. The His6-containing solubility tag was re-captured on a Ni affinity column and the cleaved TET2CDΔLCI was further purified by heparin affinity chromatography (Heparin HP), loading in 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM TCEP and gradient eluting with 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 2 M NaCl, 0.5 mM TCEP (0–100%). TET2CDΔLCI was further purified by size exclusion chromatography (Superdex® 200) in 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM TCEP. The purified protein was stored at a concentration of 20 mg mL−1 in gel filtration buffer.

SPPS synthesis of TiP1

TiP1 (Figure. S11) was synthesised on a 100 μmole scale on a Liberty Blue automated peptide synthesiser (CEM) using standard fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc) solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) as previously described32. Briefly, linear TiP1 was synthesised on a Rink amide 4-methylbenzhydrylamine (MBHA) resin. The α-N–amine was chloroacetylated using chloroacetic anhydride (10 eq.) in DMF at room temperature for 3 h, the resin was washed (DMF and CH2Cl2), and air-dried. The peptide was cleaved from the resin by treatment with a 37:1:1:1 mixture of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)/1,3-dimethoxybenzene/triisopropyl silane (TIPS)/H2O at room temperature for 3 h. The peptide was precipitated from ice-cold diethyl ether and pelleted by centrifugation (4000 × g, 10 min, 4 °C).The pellet was further washed with ice-cold diethyl ether (4×), air-dried, and the crude was lyophilised from a solution of 1:1 H2O/MeCN. The resulting pellet was dissolved in DMSO (20 mg mL−1), and the solution was basified by the addition of N,N–diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) to facilitate intramolecular thioether formation (40 °C, 1.5 h). TiP1 was purified to >99.0% purity by reverse-phase HPLC (Phenomenex Gemini® 5 μm NX-C18 110 Å LC column, H2O/MeCN solvent system supplemented with 0.1% v/v TFA). Peptide purity and identity was verified by LC–UV and HR–MS (Figure. S12) using an ACQUITY Ultra Performance LC system coupled to a Waters Xevo G2-XS Q-TOF mass spectrometer equipped with an ESI LockSpray™ source and an ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 Column (100 Å, 1.8 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm).

1H NMR spectroscopy

All 1H NMR spectra were recorded at 25 °C using D2O as a reference for internal deuterium lock on a Bruker Avance III 700 MHz equipped with an inverse TCI cryoprobe in 3 or 5 mm diameter tubes with a total sample volume of 160 or 565 μL, respectively. The water signal was reduced using Perfect Echo excitation sculpting suppression. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm relative to D2O (δH = 4.70 ppm).

Continuous reaction monitoring (1H NMR)

Spectrometer settings were determined using a control sample containing all reaction components excluding enzyme. TET enzyme was added to an identical sample, and the resulting assay mixture was transferred to an NMR tube before deposition into the instrument. The final reaction mixtures contained 5 μM NgTet1/TET2CDΔLCI, 2 mM sodium l-ascorbate, 100 μM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2, and 50–4,000 μM disodium 2OG in 50 mM Tris-d11 (pH 7.5), 10% v/v D2O; 5mC, 5HC, or AT DNA were added to a final concentration of 20 μM of double-stranded DNA (total 5mC concentration of 40 μM) as necessary. Data acquisition was started following a brief spectrometer setting optimisation (up to 200 s delay between enzyme addition and data acquisition); 8–32 scans were accumulated for a single spectrum, corresponding to 65–179 s of acquisition time. Spectrum recordings were carried out consecutively without delay. Data were processed using automated routines on MestReNova v14.2.0; signals of interest were integrated with absolute intensity scaling. 1H NMR time courses reported in figures are representative results from two or three independent replicates.

End-point enzyme inhibition assays (1H NMR)

NgTet1 was pre-incubated with inhibitor dilution series in DMSO-d6 at room temperature for 10 min (50 mM Tris-d11 [pH 7.5], 2% v/v DMSO-d6). Reactions were initiated by the addition of appropriate cofactors and DNA. The final reaction mixtures contained 5 μM NgTet1, 2 mM sodium l-ascorbate, 100 μM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2, 50 μM disodium 2OG, and 1% v/v DMSO-d6 in 50 mM Tris-d11 [pH 7.5], 10% v/v D2O; 5mC or 5HC DNA was added to a final concentration of 20 μM of double-stranded DNA (40 μM of 5mC) as necessary. The reactions were quenched by the addition of 9 mM NOG and 9 mM ZnCl2 in 90 mM Tris-d11 [pH 7.5] (20 μL) within the enzyme linear activity window (determined in Figure. S10). Samples were transferred to NMR tubes and subjected to 1H NMR analysis. Data were processed as described above. Inhibition data was normalised to reactions containing vehicle only (1% v/v DMSO-d6) and fitted using “log(inhibitor) vs. response - Variable slope (four parameters)” non-linear regression model on GraphPad Prism 5.

AlphaScreen 5hmC detection assay

AlphaScreen™ IgG (Protein A) Detection Kit was used to evaluate inhibitor potency by quantifying 5hmC levels in reaction mixtures following reported procedures33,34 using an anti-5hmC antibody (Active Motif, RRID: AB_10013602). Compounds in DMSO (100 nL) were pre-dispensed in a logarithmically linear concentration gradient onto 384-well ProxiPlates using an Echo® 550 acoustic liquid handler (Labcyte). NgTet1 was pre-incubated with the inhibitor dilution series in DMSO at room temperature for 10 min. Reactions were initiated by the addition of appropriate cofactors and DNA. The final reaction mixtures (10 μL) contained 400 nM NgTet1, 10 nM 5mC ssDNA, 100 μM sodium l-ascorbate, 10 μM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2, 10 μM disodium 2OG, and 1% v/v DMSO in assay buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.3], 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% v/v BSA, 0.01% v/v Tween® 20). The reactions were quenched by the addition of 30 mM EDTA (pH 4.2), 358 mM NaCl (5 μL) within the enzyme linear activity window (determined in Fig. S10). Concurrently, a mixture containing the anti-5hmC antibody (1:2000 dilution) and AlphaScreen beads (1:62.5 dilution) in assay buffer was prepared and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The AlphaScreen bead/antibody mixture was added to the quenched NgTet1 reactions (5 μL), and the complete mixture was incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Chemiluminescence was measured on a PHERAstar FS/FSX (BMG Labtech) equipped with an AlphaScreen 680 570 module. All AlphaScreen bead manipulations were performed under subdued lighting. Inhibition data was normalised to reactions containing vehicle only (1% v/v DMSO) and fitted using “log(inhibitor) vs. response—Variable slope (four parameters)” non-linear regression model on GraphPad Prism 5.

AlphaScreen competition assay

AlphaScreen™ Histidine (Nickel Chelate) Detection Kit was used to evaluate displacement of non-biotinylated competitor DNA oligomers by a biotinylated double-stranded 32 bp DNA oligomer (5mC dsDNA)33,34. Competitor DNA oligomers in assay buffer were manually dispensed onto 384-well ProxiPlates (5 μL) in a 2-fold dilution series. His6-tagged NgTet1 or TET2CDΔLCI in assay buffer was added (5 μL), and the mixture was pre-incubated with the competitor DNA at room temperature for 10 min. Cofactors and biotinylated 5mC dsDNA in assay buffer were added (5 μL), and the mixture was further incubated at room temperature for 10 min. A mixture of AlphaScreen beads (1:62.5 dilution) in assay buffer was added (5 μL), and the full mixture was incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The final mixtures (20 μL) contained 100 nM NgTet1 (50 nM 5mC dsDNA) or 12.5 nM TET2CDΔLCI (12.5 nM 5mC dsDNA), 50 μM sodium l-ascorbate, 5 μM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2, and 5 μM disodium NOG in assay buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.3], 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% v/v BSA, 0.01% v/v Tween® 20). For the assay interference counter screen, His6-tagged TET protein and biotinylated 5mC dsDNA were replaced with 1.6 nM biotinylated His6 peptide. Chemiluminescence was measured on a PHERAstar FS/FSX (BMG Labtech) equipped with an AlphaScreen 680 570 module. All AlphaScreen bead manipulations were performed under subdued lighting. Inhibition data was normalised to reactions containing no competitor and fitted using “log(inhibitor) vs. response - Variable slope (four parameters)” non-linear regression model on GraphPad Prism 5.

SPE-MS

SPE-MS spectra were recorded on an Agilent RapidFire 365 High-throughput Mass Spectrometry system coupled to an Agilent 6550 iFunnel Q-TOF mass spectrometer following reported procedures33,34. A RapidFire C4 (type A) solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridge (Agilent, Cat#: G9203A) was used for analyte separation. A binary solvent system was used. Solvent A: 6 mM octylammonium acetate (prepared as described previously)45 in H2O; solvent B: 80% v/v MeCN in H2O. Samples were aspirated into the sample loop using vacuum (40 μL) from a 96/384-well plate and loaded directly onto the SPE cartridge. The cartridge was washed with solvent A (4,000 ms, 1.5 mL min−1), and the analyte was eluted with solvent B (4000 ms; 1.25 mL min−1) onto the Q-TOF MS. Following each sample injection, the SPE cartridge was flushed with 3–6 cycles of H2O and MeCN to remove residual analyte before re-equilibration into solvent A. Q-TOF settings for DNA oligomer analysis were as follows: drying gas temperature: 280 °C; drying gas flow: 13 L min−1; nebuliser gas pressure: 40 psig; sheath gas temperature: 350 °C; sheath gas flow: 12 L min−1; capillary voltage (Vcap): 4000 V; nozzle voltage: 0 V; fragmentor voltage: 250 V; spectrum acquisition rate: 5 Hz. Data was processed using Agilent MassHunter Qualitative Analysis™ (B.07.00) and RapidFire Integrator software.

Continuous reaction monitoring (SPE-MS)

A sample containing all reaction components excluding NgTet1 was prepared in a 96-deep well plate. The reaction was initiated at room temperature by the addition of NgTet1 and the resulting mixture was sampled at pre-determined intervals (typically 180 s). The final reaction mixtures contained 500 nM NgTet1, 0.5–10 μM 5mC DNA, 200 µM sodium l-ascorbate, 20 μM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2, and 500 µM disodium 2OG in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.1).

End-point analysis for tandem activity detection (SPE-MS)

Small portions of reaction mixtures prepared for 1H NMR continuous reaction monitoring experiments (5 μL) were quenched by the addition of 2,4-PDCA (1.1 mM in 50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 45 μL). The final quenched mixtures contained 500 nM NgTet1, 2 μM 5mC DNA, 200 µM sodium l-ascorbate, 10 μM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2, 20 µM disodium 2OG, and 1 mM 2,4-PDCA in 45 mM Tris, 5 mM Tris-d11 (pH 7.5), 1% v/v D2O. The samples were analysed by SPE-MS.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Christoph Lönarz (Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg) for His6-tagged NgTet1 plasmid; Prof. Yanhui Xu (State Key Laboratory of Genetic Engineering, Fudan University, China) for His6-FLAG-SUMO-tagged TET2CDΔLCI plasmid; Eidarus Salah for help with recombinant protein production; Prof. Tom Brown and ATDBio for the preparation of 5mC DNA; Assoc. Prof. Christopher Lohans (Queen’s University at Kingston) for help with recombinant expression of NgTet1; Dr Anthony Tumber for assistance with SPE-MS assay optimisation; Assoc. Prof. Richard Hopkinson (U. Leicester) for helpful discussions; Dr Corinne Wills and Dr Casey M Dixon (Newcastle University) for help and support with NMR experiments.

We thank the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council Centre for Doctoral Training in Synthesis for Biology and Medicine (EP/L015838/1) for a studentship to K.S., generously supported by AstraZeneca, Diamond Light Source, Defence Science and Technology Laboratory, Evotec, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Syngenta, Takeda, UCB, and Vertex. The work was further supported by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme [679479, 101003111] and Cancer Research UK [C8717/A28285]. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript (AAM) version arising from this submission.

Author contributions

K.S., R.B., and A.K. conceived and designed the project. R.B. and A.K. supervised the project. K.S. and R.B. produced recombinant NgTet1, while K.S. produced recombinant TET2 and cyclic peptide TiP1. K.S. carried out biochemical characterisation of NgTet1 and TET2 (SPE-MS, AlphaScreen, and 1H NMR) and K.S. and R.B. performed inhibitor evaluation for NgTet1 (AlphaScreen and 1H NMR). K.S. and A.K. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files. Further processed and unprocessed data, including MALDI-TOF files, SPE-MS files, AS luminescence files, and SDS-PAGE gel images, is available upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42004-024-01382-1.

References

- 1.Islam, M. S., Leissing, T. M., Chowdhury, R., Hopkinson, R. J. & Schofield, C. J. 2-oxoglutarate-dependent oxygenases. Annu. Rev. Biochem.87, 585–620 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tahiliani, M. et al. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science324, 930–935 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ito, S. et al. Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science333, 1300–1303 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maiti, A. & Drohat, A. C. Thymine DNA glycosylase can rapidly excise 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine: potential implications for active demethylation of CpG sites. J. Biol. Chem.286, 35334–35338 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehrlich, M. et al. Amount and distribution of 5-methylcytosine in human DNA from different types of tissues or cells. Nucleic Acids Res.10, 2709–2721 (1982). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pais, J. E. et al. Biochemical characterization of a Naegleria TET-like oxygenase and its application in single molecule sequencing of 5-methylcytosine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA112, 4316–4321 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adam, S. et al. Flanking sequences influence the activity of TET1 and TET2 methylcytosine dioxygenases and affect genomic 5hmC patterns. Commun. Biol.5, 92 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravichandran, M. et al. Pronounced sequence specificity of the TET enzyme catalytic domain guides its cellular function. Sci. Adv.8, eabm2427 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cedar, H. & Bergman, Y. Linking DNA methylation and histone modification: patterns and paradigms. Nat. Rev. Genet.10, 295–304 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pastor, W. A. et al. Genome-wide mapping of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in embryonic stem cells. Nature473, 394–397 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gu, T. P. et al. The role of Tet3 DNA dioxygenase in epigenetic reprogramming by oocytes. Nature477, 606–612 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamaguchi, S., Shen, L., Liu, Y., Sendler, D. & Zhang, Y. Role of Tet1 in erasure of genomic imprinting. Nature504, 460–464 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang, Y. et al. Distinct roles of the methylcytosine oxidases Tet1 and Tet2 in mouse embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA111, 1361–1366 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lan, J. et al. Functional role of Tet-mediated RNA hydroxymethylcytosine in mouse ES cells and during differentiation. Nat. Commun.11, 4956 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang, H. et al. Tumor development is associated with decrease of TET gene expression and 5-methylcytosine hydroxylation. Oncogene32, 663–669 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng, Y., Li, X., Cassady, K., Zou, Z. & Zhang, X. TET2 function in hematopoietic malignancies, immune regulation, and DNA repair. Front. Oncol.9, 210 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez, S. & Hausinger, R. P. Catalytic mechanisms of Fe(II)- and 2-oxoglutarate-dependent oxygenases. J. Biol. Chem.290, 20702–20711 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hopkinson, R. J., Hamed, R. B., Rose, N. R., Claridge, T. D. W. & Schofield, C. J. Monitoring the activity of 2-oxoglutarate dependent histone demethylases by NMR spectroscopy: direct observation of formaldehyde. ChemBioChem11, 506–510 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Counts, D. F., Cardinale, G. J. & Udenfriend, S. Prolyl hydroxylase half reaction: peptidyl prolyl-independent decarboxylation of alpha-ketoglutarate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA75, 2145–2149 (1978). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puistola, U., Turpeenniemi-Hujanen, T. M., Myllylä, R. & Kivirikko, K. I. Studies on the lysyl hydroxylase reaction. I. Initial velocity kinetics and related aspects. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Enzymol.611, 40–50 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tuderman, L., Myllylä, R. & Kivirikko, K. I. Mechanism of the prolyl hydroxylase reaction: 1. role of co-substrate. Eur. J. Biochem.80, 341–348 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ergel, B. et al. Protein dynamics control the progression and efficiency of the catalytic reaction cycle of the Escherichia coli DNA-repair enzyme AlkB. J. Biol. Chem.289, 29584–29601 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alves, J., Vidugiris, G., Goueli, S. A. & Zegzouti, H. Bioluminescent high-throughput succinate detection method for monitoring the activity of JMJC histone demethylases and Fe(II)/2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. SLAS Discov.23, 242–254 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu, L. et al. Crystal structure of TET2-DNA complex: insight into TET-mediated 5mC oxidation. Cell155, 1545–1555 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu, L. et al. Structural insight into substrate preference for TET-mediated oxidation. Nature527, 118–122 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hashimoto, H. et al. Structure of a Naegleria Tet-like dioxygenase in complex with 5-methylcytosine DNA. Nature506, 391–395 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song, C. X. et al. Genome-wide profiling of 5-formylcytosine reveals its roles in epigenetic priming. Cell153, 678–691 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sudhamalla, B., Dey, D., Breski, M. & Islam, K. A rapid mass spectrometric method for the measurement of catalytic activity of ten-eleven translocation enzymes. Anal. Biochem.534, 28–35 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szulwach, K. E. et al. 5-hmC-mediated epigenetic dynamics during postnatal neurodevelopment and aging. Nat. Neurosci.14, 1607–1616 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weirath, N. A. et al. Small molecule inhibitors of TET dioxygenases: Bobcat339 activity is mediated by contaminating copper(II). ACS Med. Chem. Lett.13, 792–798 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim, J., Kim, K., Mo, J. S. & Lee, Y. Atm deficiency in the DNA polymerase β null cerebellum results in cerebellar ataxia and Itpr1 reduction associated with alteration of cytosine methylation. Nucleic Acids Res.48, 3678–3691 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishio, K. et al. Thioether macrocyclic peptides selected against TET1 compact catalytic domain inhibit TET1 catalytic activity. ChemBioChem19, 979–985 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belle, R. et al. Focused screening identifies different sensitivities of human TET oxygenases to the oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate. J. Med. Chem.67, 4525–4540 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Šimelis, K. et al. Selective targeting of human TET1 by cyclic peptide inhibitors: Insights from biochemical profiling. Bioorg. Med. Chem.99, 117597 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khan, A., Schofield, C. J. & Claridge, T. D. W. Reducing agent-mediated nonenzymatic conversion of 2-oxoglutarate to succinate: implications for oxygenase assays. ChemBioChem21, 2898–2902 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Myllyla, R., Majamaa, K. & Gunzler, V. Ascorbate is consumed stoichiometrically in the uncoupled reactions catalyzed by prolyl 4-hydroxylase and lysyl hydroxylase. J. Biol. Chem.259, 5403–5405 (1984). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Jong, L., Albracht, S. P. J. & Kemp, A. Prolyl 4-hydroxylase activity in relation to the oxidation state of enzyme-bound iron role ascorbate peptidyl proline hydroxylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol.704, 326–332 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamada, S. et al. Synthesis and activity of N-oxalylglycine and its derivatives as Jumonji C-domain-containing histone lysine demethylase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.19, 2852–2855 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.King, O. N. F. et al. Quantitative high-throughput screening identifies 8-hydroxyquinolines as cell-active histone demethylase inhibitors. PLoS ONE5, e15535 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rose, N. R. et al. Inhibitor scaffolds for 2-oxoglutarate-dependent histone lysine demethylases. J. Med. Chem.51, 7053–7056 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rao, N. V. & Adams, E. Partial reaction of prolyl hydroxylase. (Gly-Pro-Ala)(n) stimulates α-ketoglutarate decarboxylation without prolyl hydroxylation. J. Biol. Chem.253, 6327–6330 (1978). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rose, N. R., McDonough, M. A., King, O. N. F., Kawamura, A. & Schofield, C. J. Inhibition of 2-oxoglutarate dependent oxygenases. Chem. Soc. Rev.40, 4364–4397 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laukka, T. et al. Fumarate and succinate regulate expression of hypoxia-inducible genes via TET enzymes. J. Biol. Chem.291, 4256–4265 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Losman, J.-A., Koivunen, P. & Kaelin, W. G. 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer20, 710–726 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huck, J. H. J., Struys, E. A., Verhoeven, N. M., Jakobs, C. & Van Der Knaap, M. S. Profiling of pentose phosphate pathway intermediates in blood spots by tandem mass spectrometry: application to transaldolase deficiency. Clin. Chem.49, 1375–1380 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iwan, K. et al. 5-formylcytosine to cytosine conversion by C-C bond cleavage in vivo. Nat. Chem. Biol.14, 72–78 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kamińska, E., Korytiaková, E., Reichl, A., Müller, M. & Carell, T. Intragenomic decarboxylation of 5-carboxy-2′-deoxycytidine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.60, 23207–23211 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liutkevičiutė, Z. et al. Direct decarboxylation of 5-carboxylcytosine by DNA C5- methyltransferases. J. Am. Chem. Soc.136, 5884–5887 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files. Further processed and unprocessed data, including MALDI-TOF files, SPE-MS files, AS luminescence files, and SDS-PAGE gel images, is available upon request.