Abstract

While in theory antibody drug conjugates (ADCs) deliver high-dose chemotherapy directly to target cells, numerous side effects are observed in clinical practice. We sought to determine the effect of linker design (cleavable versus non-cleavable), drug-to-antibody ratio (DAR), and free payload concentration on systemic toxicity. Two systematic reviews were performed via PubMed search of clinical trials published between January 1998—July 2022. Eligible studies: (1) clinical trial for cancer therapy in adults, (2) ≥ 1 study arm included a single-agent ADC, (3) ADC used was commercially available/FDA-approved. Data was extracted and pooled using generalized linear mixed effects logistic models. 40 clinical trials involving 7,879 patients from 11 ADCs, including 9 ADCs with cleavable linkers (N = 2,985) and 2 with non-cleavable linkers (N = 4,894), were included. Significantly more composite adverse events (AEs) ≥ grade 3 occurred in patients in the cleavable linkers arm (47%) compared with the non-cleavable arm (34%). When adjusted for DAR, for grade ≥ 3 toxicities, non-cleavable linkers remained independently associated with lower toxicity for any AE (p = 0.002). Higher DAR was significantly associated with higher probability of grade ≥ 3 toxicity for any AE. There was also a significant interaction between cleavability status and DAR for any AE (p = 0.002). Finally, higher measured systemic free payload concentrations were significantly associated with higher DARs (p = 0.043). Our results support the hypothesis that ADCs with cleavable linkers result in premature payload release, leading to increased systemic free payload concentrations and associated toxicities. This may help to inform future ADC design and rational clinical application.

Keywords: Antibody–drug conjugates, Cleavable and non-cleavable linkers, Payloads, Drug to antibody ratio, Systemic toxicities, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) are monoclonal antibodies connected to a cytotoxic agent known as the payload via a chemical linker. It was hoped that ADCs would be “magic bullets,” delivering high-dose cytotoxic chemotherapy directly to cancer cells without affecting surrounding normal tissues. However, this has not borne out in clinical practice. Though many factors affect toxicity, the toxicities of currently approved ADCs appear to be driven primarily by premature release of the payload into the bloodstream by the linker, by an excessively prominent bystander effect [1], or even payload released by the lysed tumor cells [2].

ADC linkers can be divided broadly into two groups: cleavable and non-cleavable. Cleavable linkers such as hydrazone, disulfide, or peptide linkers rely on physiologic factors (i.e., cathepsin, glutathione (GSH), and low pH) within the cell to cleave the linker. Because these conditions can occur independently of antigen internalization, cleavable linkers are often less stable in the blood, resulting in various off-target effects [3]. In contrast, non-cleavable linkers, such as the thioether or maleimidocaproyl linkers, require internalization by the target cell, so that the antibody, rather than the linker, can be degraded by the lysosome before the drug is released. This latter mechanism does not produce efficient bystander killing and thus results in lower toxicity profiles [4]. For these reasons, other novel linkers, including conditionally released linkers, are currently in rapid development [5, 6].

Preclinical studies have shown that compared to ADCs with non-cleavable linkers, those with cleavable linkers likely release free payload prematurely, leading to increased systemic toxicity. In this study, we sought to delineate the potential effect of linker design on systemic toxicity by analyzing the results of clinical trials using ADCs constructed with both types of linkers. We hypothesized that ADCs with cleavable linkers would be associated with greater systemic toxicities than those with non-cleavable linkers. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a systematic review of adverse events (AEs) occurring in cancer patients treated with commercially available ADCs. We then carried out a meta-analysis on all eligible phase II-III clinical trials. We also evaluated the potential effect of drug-to-antibody ratio (DAR) and systemic free payload concentration on toxicity in the context of the cleavability of the linkers used.

Materials and methods

Search methods and study selection

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) 2020 updated guidance, two systematic reviews were performed through a PubMed search on July 5, 2022. The first identified studies reporting clinical toxicity rates. Studies eligible for inclusion met the following criteria: (1) clinical trial for cancer therapy in adults ages 18 or older, (2) participants in at least one arm of the study were treated with single-agent ADC, (3) the ADC used was commercially available and FDA-approved for cancer treatment as of July 5, 2022, (4) the study reported treatment-related adverse events, and (5) the study was published in English. Studies where the ADC was administered in combination with other chemotherapy agents were excluded because the ADC’s individual contribution to the overall toxicity profile of the regimen could not be fully delineated. A second systematic review identified studies reporting the DARs and estimated systemic free payload concentrations for all FDA-approved ADCs.

Statistical analysis: meta-analysis of clinical toxicity rates

To compare the incidence of toxicities in patients treated with ADCs constructed with cleavable vs non-cleavable linkers, generalized linear mixed effects logistic models were conducted for each toxicity, including:

1. By linker type. Univariable mixed effects logistic regression models were constructed evaluating the association between frequency of each specific toxicity for the binary outcome variables (any grade vs none; grade ≥ 3 versus grade ≤ 2) and ADC linker type (cleavable vs non-cleavable).

2. Linker type adjusted for drug-to-antibody ratio. Multivariable mixed effects logistic regression models were constructed evaluating the association between frequency of each specific toxicity for the binary outcome variables (any grade vs none; grade ≥ 3 vs grade ≤ 2) and ADC linker type (cleavable vs non-cleavable) plus drug-to-antibody ratio (numeric predictor) with the potential interaction between ADC linker type and drug-to-antibody ratio when estimable. The model includes the interaction when estimable since cleavability status and drug-to-antibody ratio are not necessarily independent factors but arise from the design of each medication.

3. Linker type adjusted for estimated systemic free payload concentration. Multivariable mixed effects logistic regression models were constructed evaluating the association between frequency of each specific toxicity for the binary outcome variables (any grade vs none; grade ≥ 3 vs grade ≤ 2) and ADC linker type (cleavable vs non-cleavable) plus systemic free payload concentration (numeric predictor) with the potential interaction between ADC linker type and payload systemic free concentration when estimable. Again, the model includes the interaction when estimable since cleavability status and systemic free payload concentration are not necessarily independent factors but arise from the design of each medication.

Heterogeneity in the estimated probability of each specific toxicity between studies was assessed with the I [2] statistic, describing the percentage of variation in probability of each specific toxicity across the studies arising from differences in the included trials (heterogeneity) rather than sampling error (chance).

Results

Study inclusion

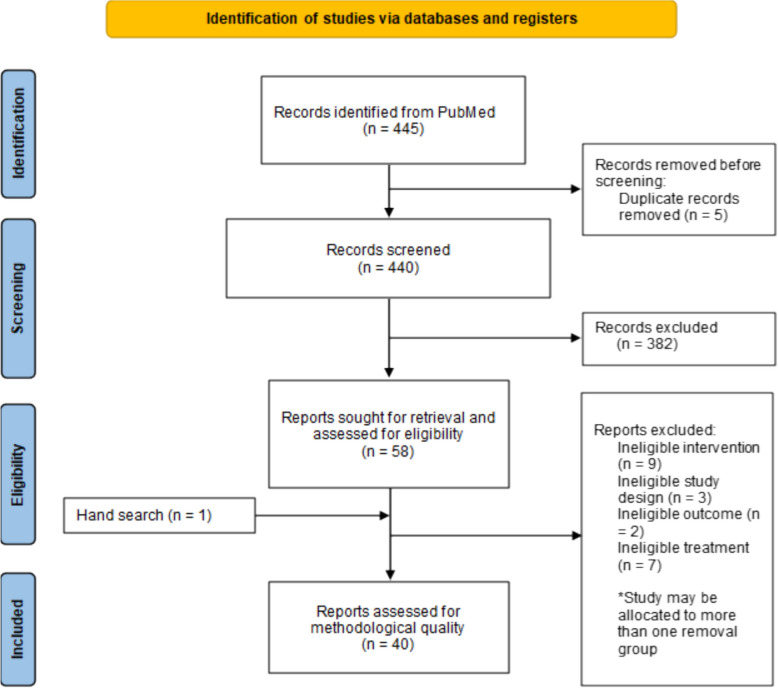

A literature search and review of references identified 440 relevant publications after duplicates were removed. After eligibility assessment, a total of 40 clinical trials involving 7,879 patients were used to perform our meta-analysis, as shown in Fig. 1 [7–46]. Eleven (11) commercially-available FDA-approved ADCs were included (Table 1). Nine of these studies reported the results of treatment with ADCs with cleavable linkers (N = 2,985), whereas two used non-cleavable linkers (N = 4,894). Table 2 lists the ADC agent, target disease, study design, number of patients treated with the ADC, and modified Newcastle–Ottawa scale study quality rating. Table 3 lists the 21 specific toxicities examined. It also indicates the number of included studies reporting the specific toxicity, patients at risk, and the number of patients experiencing toxicities for grade ≥ 3 (Table 3) and any grade (Table 4).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart describing the result of the search and selection process

Table 1.

Included ADCs with linker type, drug-to-antibody ratio, and systemic maximum free payload concentration

| Antibody drug conjugate | Indication(s) | Antigen | Payload agent | Number of studies | Number of patients | Linker | Drug-to-antibody ratio (DAR) | Systemic maximum free payload concentration (kg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belantamab mafodotin | Multiple myeloma | BCMA | MMAF | 1 | 97 | Non-cleavable | 4 | 0.0004 |

| Brentuximab vedotin |

Hodgkin lymphoma, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, CD30 + peripheral T cell lymphoma, CD30 + mycosis fungoides |

CD30 | MMAE | 11 | 660 | Cleavable | 4 | 0.0026 |

| Enfortumab vedotin | Urothelial cancer | Nectin-4 | MMAE | 3 | 515 | Cleavable | 3.8 | 0.0040 |

| Gemtuzumab ozogamicin | Acute myeloid leukemia | CD33 | Calichea-micin | 2 | 175 | Cleavable | 2.5 | 0.0229 |

| Inotuzumab ozogamicin | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | CD22 | Calichea-micin | 2 | 205 | Cleavable | 6 | 0.0556 |

| Loncastuximab tesirine | Large B-cell lymphoma | CD19 | PBD dimer | 1 | 145 | Cleavable | 2.3 | 0.0003 |

| Moxetumomab pasudotox | Hairy cell leukemia | CD22 | PE38 | 1 | 80 | Cleavable | 1 | No systemic accumulation observed |

| Sacituzumab govitecan |

Breast cancer Urothelial cancer |

Trop-2 | SN38 | 3 | 479 | Cleavable | 7.6 | 0.0120 |

| Tisotumab vedotin | Cervical cancer | Tissue factor | MMAE | 2 | 156 | Cleavable | 4 | 0.0026 |

| Trastuzumab deruxtecan |

Breast cancer Gastric cancer |

HER2 | Deruxtecan | 3 | 570 | Cleavable | 8 | 0.4347 |

| Trastuzumab emtansine | Breast cancer | HER2 | Emtansine | 12 | 4,797 | Non-cleavable | 3.5 | 0.0012 |

BCMA B-cell maturation antigen, MMAE monomethyl auristatin, MMAF monomethyl auristatin F, PBD pyrrolobenzodiazepine, PE38 the 38 kDa fragment of Pseudomonas exotoxin A, SN38 active metabolite of irinotecan

Table 2.

Studies included in meta-analysis

| ADC name | Study first author, year | Cancer type | Study design/phase/site | ADC group sample size | Modified NOS rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belantamab mafadotin | Lonial, 2021 | Multiple myeloma | RCT/2/multicenter | 97 | Good |

| Brentuximab vedotin | Pro, 2012 | Systemic ALCL | Single-arm study/2/Multicenter | 58 | Fair |

| Younes, 2012 | Hodgkin lymphoma | Single-arm study/2/Multicenter | 102 | Good | |

| Horwitz, 2014 | PTCL | Single-arm study/2/Multicenter | 35 | Fair | |

| Monjanel, 2014 | Hodgkin lymphoma, ALCL | Retrospective cohort study/2/Single center | 45 | Good | |

| Duvic, 2015 | pcALCL, MF | Single-arm study/2/Single center | 54 | Good | |

| Kim, 2015 | MF, Sezary syndromeS | Single-arm study/2/Multicenter | 32 | Fair | |

| Prince, 2017 | MF, pcALCL | RCT/3/Multicenter | 64 | Good | |

| Walewski, 2018 | Hodgkin lymphoma | Single-arm study/4/Multicenter | 60 | Good | |

| Stefoni, 2020 | Hodgkin lymphoma | Single-arm study/2/Multicenter | 18 | Good | |

| Kuruvilla, 2021 | Hodgkin lymphoma | RCT/3/Multicenter | 153 | Good | |

| Song, 2021 | Hodgkin lymphoma, ALCL | Single-arm study/2/Multicenter | 39 | Fair | |

| Enfortumab vedotin | Rosenberg, 2019 | Urothelial cancer | Single-arm study/2/Multicenter | 125 | Good |

| Powles, 2021 | Urothelial cancer | RCT/3/Multicenter | 301 | Good | |

| Yu, 2021 | Urothelial cancer | Single-arm study/2/Multicenter | 89 | Good | |

| Gemtuzumab ozogamicin | Taksin, 2007 | AML | Single-arm study/2/Multicenter | 57 | Fair |

| Amadori, 2016 | AML | RCT/3/Multicenter | 118 | Good | |

| Inotuzumab ozogamicin | Kantarjian, 2013 | ALL | Single-arm study/1.5/Single center | 41 | Good |

| Kantarjian, 2019 | ALL | RCT/3/Multicenter | 164 | Good | |

| Loncastuximab tesirine | Caimi, 2021 | DLBCL | Single-arm study/2/Multicenter | 145 | Good |

| Moxetumomab pasudoxtox | Kreitman, 2021 | Hairy cell leukemia | Single-arm study/2/Multicenter | 80 | Good |

|

Sacituzumab govitecan |

Bardia, 2019 | Breast cancer | Single-arm study/1.5/Multicenter | 108 | Good |

| Bardia, 2021 | Breast cancer | RCT/3/Multicenter | 258 | Good | |

| Tagawa, 2021 | Urothelial cancer | Non-randomized multicohort study/2/Multicenter | 113 | Good | |

| Tisotumab vedotin | Hong, 2020 | Cervical cancer | Single-arm study/1.5/Multicenter | 55 | Fair |

| Coleman, 2021 | Cervical cancer | Single-arm study/2/Multicenter | 101 | Good | |

| Trastuzumab deruxtecan | Modi, 2020 | Breast cancer | Single-arm study/2/Multicenter | 184 | Good |

| Shitara, 2020 | Gastric cancer | RCT/2/Multicenter | 125 | Good | |

| Cortés, 2022 | Breast cancer | RCT/3/Multicenter | 261 | Good | |

| Trastuzumab emtansine | Burris, 2011 | Breast cancer | Single-arm study/2/Multicenter | 112 | Good |

| Krop, 2012 | Breast cancer | Single-arm study/2/Multicenter | 110 | Good | |

| Verma, 2012 | Breast cancer | RCT/3/Multicenter | 495 | Good | |

| Yardley, 2015 | Breast cancer | Single-arm study/4/Multicenter | 215 | Good | |

| Kashiwaba, 2016 | Breast cancer | Single-arm study/2/Multicenter | 73 | Good | |

| Krop, 2017 | Breast cancer | RCT/3/Multicenter | 403 | Good | |

| Watanabe, 2017 | Breast cancer | Single-arm study/2/Multicenter | 232 | Fair | |

| Montemurro, 2019 | Breast cancer | Single-arm study/3b/Multicenter | 2002 | Good | |

| Von Minckwitz, 2019 | Breast cancer | RCT/3/Multicenter | 743 | Good | |

| Cortés, 2020 | Breast cancer | RCT/1.5/Multicenter | 80 | Fair | |

| Emens, 2020 | Breast cancer | RCT/2/Multicenter | 69 | Good | |

| Cortés, 2022 | Breast cancer | RCT/3/Multicenter | 263 | Good |

ALCL anaplastic large cell lymphoma, ALL acute lymphoblastic leukemia, AML acute myeloid leukemia, DLBCL diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, MF mycosis fungoides, NOS Newcastle–Ottawa scale, pcALCL primary cutaneous ALCL, PTCL peripheral T cell lymphoma, RCT randomized controlled trial

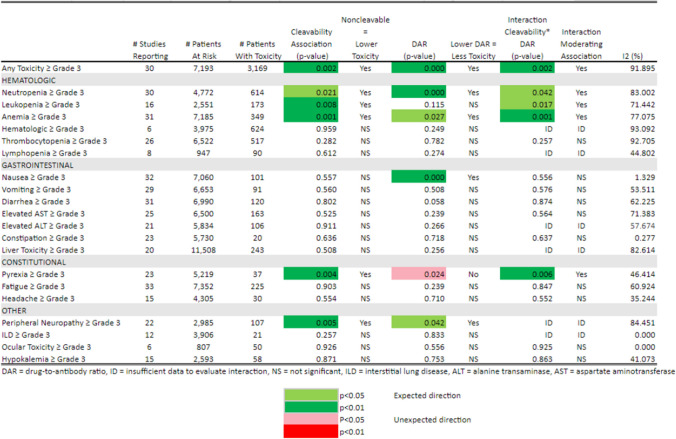

Table 3.

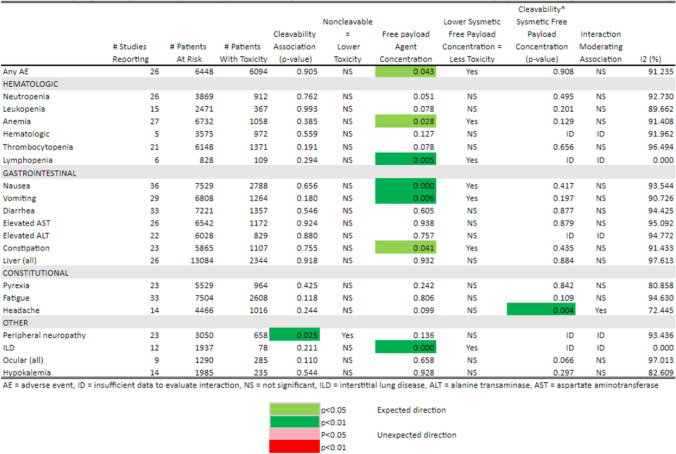

Toxicity ≥ Grade 3 by Cleavability of Linker, Drug-to-Antibody Ratio, and Interaction of Cleavability*Drug-to-Antibody Ratio

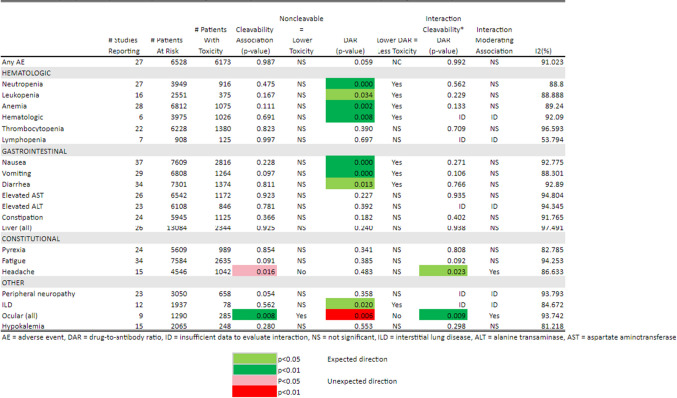

Table 4.

Toxicity Any Grade by Cleavability of Linker, Drug-to-Antibody Ratio, and Interaction of Cleavability * Drug-to-Antibody Ratio

As quantified in Tables 3 and 5, at least half the studies reported thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, anemia, increased AST and ALT, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and fatigue, as well as any toxicity at any grade and grade ≥ 3 AEs. Other toxicities were reported less frequently.

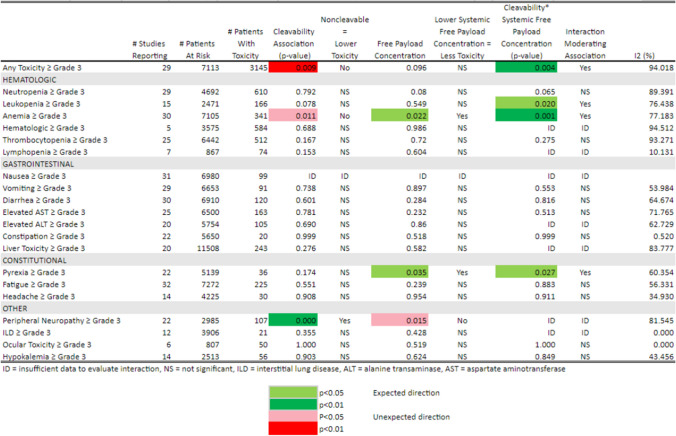

Table 5.

Toxicity ≥ Grade 3 by Cleavability of Linker, Systemic Free Payload Concentration, and Interaction of Cleavability * Systemic Free Payload Concentration

Systemic toxicity rates with ADCs, stratified by cleavable vs non-cleavable linker

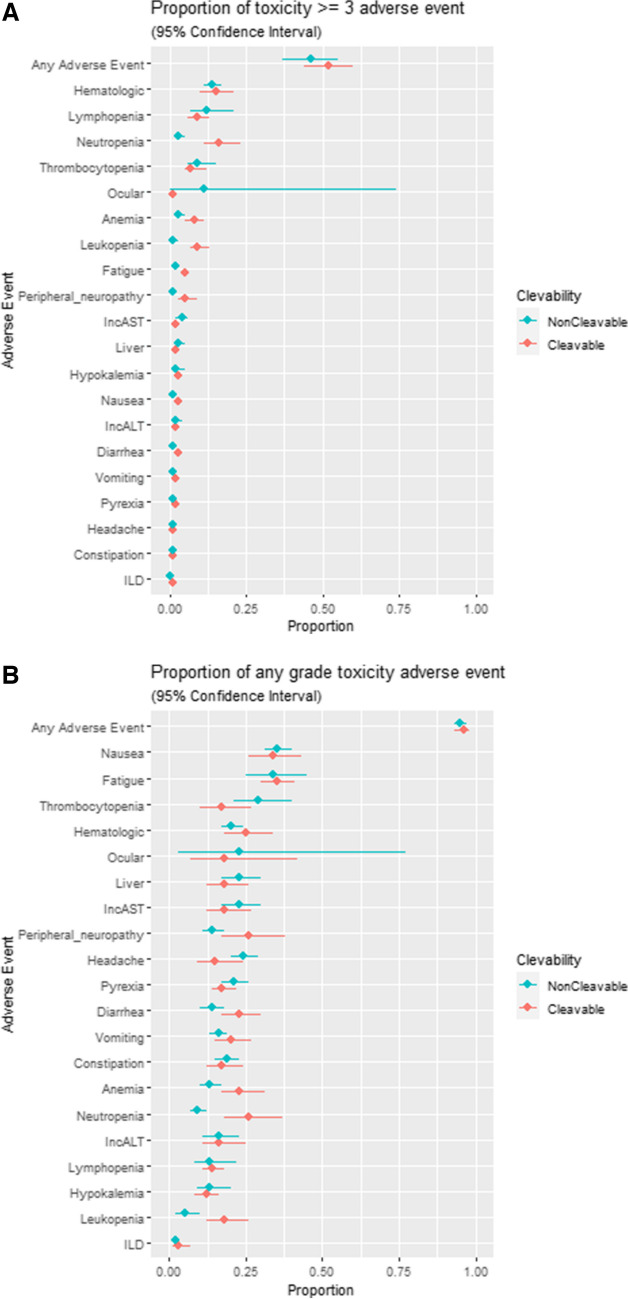

The meta-analytic point estimate of the proportion of patients experiencing each of the 21 toxicities with a 95% confidence interval is displayed in Fig. 2A for toxicities ≥ grade 3, and in Fig. 2B for any grade toxicity, both stratified by linker type. Composite AEs ≥ grade 3 occurred in 43% of patients overall, 47% in the cleavable linker-treated patients and 34% in the non-cleavable-treated patients, and these differences were significant (weighted risk difference −12.9%; 95% CI: −17.1% to −8.8%). Specific toxicities ≥ grade 3 with significantly lower proportions favoring non-cleavable linkers were neutropenia (−9.1%; 95% CI −12% to −6.2%) and anemia (−1.7%; 95% CI −3.3% to −0.1%). There was no significant difference in rates of grade ≥ 3 thrombocytopenia, increased AST/ALT, or fatigue. For all grade toxicities, there were no significant differences in rates of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, hypokalemia, or headache.

Fig. 2.

A. Proportion of patients experiencing each of the 21 toxicities ≥ grade 3 with 95% confidence interval. ILD = interstitial lung disease, IncAST = increased aspartate aminotransferase, IncALT = increased alanine aminotransferase. B: Proportion of patients experiencing each of the 21 toxicities any grade with 95% confidence interval. ILD = interstitial lung disease, IncAST = increased aspartate aminotransferase, IncALT = increased alanine aminotransferase

Linker type and drug-to-antibody ratio

We further examined the potential association between ADC linker type and drug-to-antibody ratios and the estimated probabilities of systemic toxicity. Since the linker type and drug-to-antibody ratio are design features of each ADC and thus are not independent factors, the interaction between linker type and drug-to-antibody ratio was modeled and estimated whenever feasible. A summary of the results for the 21 toxicities are represented as a heatmap (Tables 3 and 4). The p-values are color-coded for level of significance and direction of association.

For grade ≥ 3 toxicities (Table 3), non-cleavable linkers remain significantly and independently associated with lower toxicity for any AE (p = 0.002), neutropenia (p = 0.021), leukopenia (p = 0.008), anemia (p = 0.001), pyrexia (p = 0.004), and peripheral neuropathy (p = 0.005) when adjusted for DAR and their interaction where estimable. In addition, higher DAR was significantly and independently associated with higher probability of grade ≥ 3 toxicity for any AE, neutropenia, anemia, nausea (p < 0.001), and peripheral neuropathy. Higher DAR was significantly and independently associated with lower probability of grade ≥ 3 pyrexia. There were significant interaction terms between cleavability status and DAR for any AE (p = 0.002), neutropenia (p = 0.042), leukopenia (p = 0.017), anemia (p = 0.001), and pyrexia (p = 0.006). These were all moderating interactions, indicating a lower toxicity then would be predicted from the additive effects of a linear increase in DAR and linker cleavability type.

For any grade toxicity (Table 4), non-cleavable linkers were not significantly and independently associated with toxicity adjusted for DAR and their interaction except lower ocular and higher headache toxicity of any grade. However, higher DARs were significantly and independently associated with a higher probability of any grade toxicity for neutropenia, anemia, leukopenia, all hematological toxicities, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and interstitial lung disease. Although the sample size is limited, higher DAR was significantly and independently associated with lower probability of any grade ocular toxicity.

As observed in the heatmap of these data, the direction of the associations when significant were typically in the pre-specified clinically expected direction: higher DAR was associated with higher probability of grade ≥ 3 toxicity. As reported in Tables 3 and 4, most of the I [2] statistics are > 50% indicating at least moderate to high levels of heterogeneity in reported probabilities of each specific toxicity between studies.

Linker type, systemic free payload agent concentration, and toxicity

Next we considered the potential association between ADC linker type and the systemic free payload concentration, including the potential interaction between linker type and systemic free payload concentration when estimable. These results are summarized as a heatmap of the p-values for the significance of the estimated coefficients for each factor in Tables 5 (toxicities ≥ grade 3) and 6 (any grade toxicity). The p-values are color-coded for level of significance and direction of regression coefficient associations between systemic free payload concentrations and linker type. For grade ≥ 3 toxicities (Table 5), non-cleavable linkers remain significantly and independently associated with lower toxicity for only peripheral neuropathy (p = 0.001). Neutropenia, leukopenia, and pyrexia no longer had a significant independent association with linker type after adjustment for the systemic free payload concentration. In fact, the probability of any AE ≥ grade 3 (p = 0.009) and anemia (p = 0.011) was higher in patients treated with non-cleavable linkers when adjusted for systemic free payload concentrations. Similarly, higher systemic free payload concentrations were significantly and independently associated with higher probability of anemia (p = 0.022) and pyrexia (p = 0.035). For any grade toxicities (Table 6), non-cleavable linkers remain independently associated with lower peripheral neuropathy (p = 0.025) but no other toxicity when adjusted for systemic free payload concentration. The main effect of higher systemic free payload concentration was significantly associated with increased probability for any toxicity (p = 0.043), anemia (p = 0.028), lymphopenia (p = 0.005), nausea (p < 0.001), vomiting (p = 0.006), constipation (p = 0.041), and interstitial lung disease (p < 0.001) after adjustment for linker type.

Table 6.

Toxicity Any Grade by Cleavability of Linker, Systemic Free Payload Concentration, and interaction of Cleavability * Systemic Free Payload Concentration

Again the I[2] statistics tend to be > 50% indicating at least moderate to high levels of heterogeneity in probabilities of the toxicities between studies.

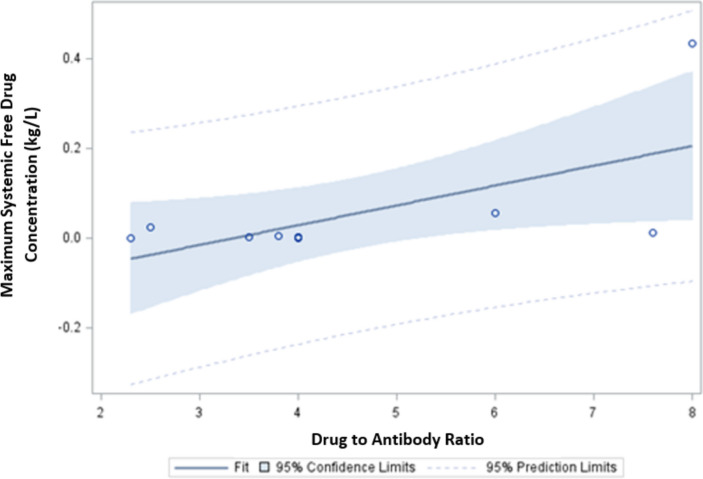

ADC linker type, DAR, and free payload concentration

As noted, linker-type, DAR, and systemic free payload concentration are not necessarily independent varying characteristics for each ADC. To further investigate this, we described the relationships between cleavability type, DAR, and measured systemic free payload concentration for the 11 FDA-approved ADCs under evaluation in this study. These characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Non-cleavable linkers have a numerically lower mean estimated DAR (3.75 ± 0.35 versus 4.78 ± 2.18, p = 0.544) and lower estimated systemic free payload concentration (1.89 × 10–5 m2/L ± 1.41 × 10–5 m2/L versus 1.62 × 10–3 m2/L ± 3.64 × 10–3 m2/L, p = 0.567). These differences are not statistically different, likely due to the small number of agents being compared (2 non-cleavable and 9-cleavable). However, the higher measured systemic free payload concentrations were significantly associated with higher DARs (p = 0.043) as depicted in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Association between DAR and maximum systemic free payload concentration

Discussion

In this review and meta-analysis, we sought to delineate how features of ADC design, including linker cleavability, DAR, and systemic free payload concentration, may contribute to their associated systemic toxicities. The results support the hypothesis that ADCs with cleavable linkers are associated with more systemic toxicities than those with non-cleavable linkers. Interestingly, even though higher DAR was associated with higher grade ≥ 3 toxicity, the apparent protective effect of the non-cleavable linker persisted even after adjusting for DAR. However, we found that the association between non-cleavable linkers and lower toxicity was not observed after adjusting for systemic free payload concentration. This suggests that systemic free payload concentration is the main factor driving toxicity in ADC-treated patients.

Notably, trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) has a considerably higher systemic free payload concentration than the other agents studied here. T-DXd has a tetrapeptide cleavable linker that may make it more vulnerable to premature release of its payload. Such a prematurely released payload might explain why T-DXd may be effective in tumor control regardless of HER2 expression. Emerging clinical evidence supports this hypothesis. In a small trial of T-DXd in non-small cell lung cancer patients, the activity of T-DXd was shown to be independent of HER2 over-expression in HER3 + , 2 + , or 1 + tumors [47]. More recently, clinical trial data presented during the 2021 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium showed that T-DXd was active in breast cancer patients regardless of HER2 expression, including HER2 0 tumors [48].

By contrast, trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1), another anti-HER2 ADC with a non-cleavable linker, has not been shown to have activity in patients with low HER2 tumor expression. This may partly explain why in the DESTINY-03 trial[35], T-DM1 (HER2 dependent) was shown to have lower efficacy compared to T-DXd (HER2 dependent and independent). Consonant with these observations, T-DM1 was also shown to have much lower systemic toxicity compared to T-DXd, likely because of the relative stability of the T-DM1 linker. We’ve previously proposed that the off-target effects observed with T-DM1 may be the result of payload released from lysed tumor cells [2]. It is tempting to speculate that for these reasons, ADCs with cleavable linkers may in general have higher anti-tumor efficacy albeit higher systemic toxicities.

Our results arise from a meta-analysis using multiple agents used to treat highly disparate patient populations with different malignancies. We suspect this explains most of the heterogeneity observed in probabilities of specific toxicities between studies reflected in the I [2] statistics. Nonetheless, differences in ADC chemical design are shown to be significantly associated with specific clinical toxicities despite this tremendous heterogeneity.

Conclusion

In summary, ADCs are rapidly becoming the standard of care for patients across disease sites. The results here show that linker choice and the potential for premature payload release among ADCs can affect their systemic toxicity and efficacy. It will, therefore, be critical in the design of future ADCs to find the appropriate balance between the highest potential efficacy and associated systemic toxicities [49]. In this regard, contemporary studies are focused on the development of novel ADC linkers that can be released conditionally within the tumor microenvironment to increase both the specificity of drug delivery and anti-tumor efficacy. The ideal ADC design should aim for high therapeutic index that balances off-target toxicities, taking into consideration factors such as linker cleavability, DAR, and payload membrane permeability [50]. The results presented here suggest one critical consideration in achieving this balance during future ADC development for cancer patients will be linker design and the potential for premature payload release.

Author Contribution

S.C.T. conceived of the idea and supervised the study design and manuscript writing. C.W., M.M., and R.P. assisted with data collection and manuscript writing. T.L., Y.Z., and W.H. designed the computational framework and analyzed the data. W.H. also assisted with manuscript writing. N.M. helped supervise the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pondé, N., Aftimos, P., & Piccart, M. (2019). Antibody-Drug Conjugates in Breast Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Current Treatment Options in Oncology,20(5), 37. 10.1007/s11864-019-0633-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang, S. C., Capra, C. L., Ajebo, G. H., et al. (2021). Systemic toxicities of trastuzumab-emtansine predict tumor response in HER2+ metastatic breast cancer. International Journal of Cancer,149(4), 909–916. 10.1002/ijc.33597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hafeez, U., Parakh, S., Gan, H. K., & Scott, A. M. (2020). Antibody-Drug Conjugates for Cancer Therapy. Molecules Basel Switz,25(20), 4764. 10.3390/molecules25204764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staudacher, A. H., & Brown, M. P. (2017). Antibody drug conjugates and bystander killing: Is antigen-dependent internalisation required? British Journal of Cancer,117(12), 1736–1742. 10.1038/bjc.2017.367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su, Z., Xiao, D., Xie, F., et al. (2021). Antibody–drug conjugates: Recent advances in linker chemistry. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B,11(12), 3889–3907. 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.03.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsuchikama, K., Anami, Y., Ha, S. Y. Y., & Yamazaki, C. M. (2024). Exploring the next generation of antibody–drug conjugates. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology,21(3), 203–223. 10.1038/s41571-023-00850-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lonial, S., Lee, H. C., Badros, A., et al. (2021). Longer term outcomes with single-agent belantamab mafodotin in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: 13-month follow-up from the pivotal DREAMM-2 study. Cancer,127(22), 4198–4212. 10.1002/cncr.33809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pro, B., Advani, R., Brice, P., et al. (2012). Brentuximab vedotin (SGN-35) in patients with relapsed or refractory systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: Results of a phase II study. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology,30(18), 2190–2196. 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Younes, A., Gopal, A. K., Smith, S. E., et al. (2012). Results of a pivotal phase II study of brentuximab vedotin for patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology,30(18), 2183–2189. 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horwitz, S. M., Advani, R. H., Bartlett, N. L., et al. (2014). Objective responses in relapsed T-cell lymphomas with single-agent brentuximab vedotin. Blood,123(20), 3095–3100. 10.1182/blood-2013-12-542142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monjanel, H., Deville, L., Ram-Wolff, C., et al. (2014). Brentuximab vedotin in heavily treated Hodgkin and anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, a single centre study on 45 patients. British Journal of Haematology,166(2), 306–308. 10.1111/bjh.12849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duvic, M., Tetzlaff, M. T., Gangar, P., Clos, A. L., Sui, D., & Talpur, R. (2015). Results of a Phase II Trial of Brentuximab Vedotin for CD30+ Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma and Lymphomatoid Papulosis. Journal of Clinical Oncology,33(32), 3759–3765. 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.3787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim, Y. H., Tavallaee, M., Sundram, U., et al. (2015). Phase II Investigator-Initiated Study of Brentuximab Vedotin in Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome With Variable CD30 Expression Level: A Multi-Institution Collaborative Project. Journal of Clinical Oncology,33(32), 3750–3758. 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.3969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prince, H. M., Kim, Y. H., Horwitz, S. M., et al. (2017). Brentuximab vedotin or physician’s choice in CD30-positive cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (ALCANZA): An international, open-label, randomised, phase 3, multicentre trial. The Lancet Lond Engl,390(10094), 555–566. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31266-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walewski, J., Hellmann, A., Siritanaratkul, N., et al. (2018). Prospective study of brentuximab vedotin in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma patients who are not suitable for stem cell transplant or multi-agent chemotherapy. British Journal of Haematology,183(3), 400–410. 10.1111/bjh.15539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stefoni, V., Marangon, M., Re, A., et al. (2020). Brentuximab vedotin in the treatment of elderly Hodgkin lymphoma patients at first relapse or with primary refractory disease: A phase II study of FIL ONLUS. Haematologica,105(10), e512. 10.3324/haematol.2019.243170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuruvilla, J., Ramchandren, R., Santoro, A., et al. (2021). Pembrolizumab versus brentuximab vedotin in relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma (KEYNOTE-204): An interim analysis of a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. The Lancet Oncology,22(4), 512–524. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00005-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song, Y., Guo, Y., Huang, H., et al. (2021). Phase II single-arm study of brentuximab vedotin in Chinese patients with relapsed/refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma or systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Expert Review of Hematology,14(9), 867–875. 10.1080/17474086.2021.1942831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenberg, J. E., O’Donnell, P. H., Balar, A. V., et al. (2019). Pivotal Trial of Enfortumab Vedotin in Urothelial Carcinoma After Platinum and Anti-Programmed Death 1/Programmed Death Ligand 1 Therapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology,37(29), 2592–2600. 10.1200/JCO.19.01140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powles, T., Rosenberg, J. E., Sonpavde, G. P., et al. (2021). Enfortumab Vedotin in Previously Treated Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine,384(12), 1125–1135. 10.1056/NEJMoa2035807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu, E. Y., Petrylak, D. P., O’Donnell, P. H., et al. (2021). Enfortumab vedotin after PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors in cisplatin-ineligible patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma (EV-201): A multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. The Lancet Oncology,22(6), 872–882. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00094-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taksin, A. L., Legrand, O., Raffoux, E., et al. (2007). High efficacy and safety profile of fractionated doses of Mylotarg as induction therapy in patients with relapsed acute myeloblastic leukemia: A prospective study of the alfa group. Leukemia,21(1), 66–71. 10.1038/sj.leu.2404434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amadori, S., Suciu, S., Selleslag, D., et al. (2016). Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin Versus Best Supportive Care in Older Patients With Newly Diagnosed Acute Myeloid Leukemia Unsuitable for Intensive Chemotherapy: Results of the Randomized Phase III EORTC-GIMEMA AML-19 Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology,34(9), 972–979. 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.0060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kantarjian, H., Thomas, D., Jorgensen, J., et al. (2013). Results of inotuzumab ozogamicin, a CD22 monoclonal antibody, in refractory and relapsed acute lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer,119(15), 2728–2736. 10.1002/cncr.28136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kantarjian, H. M., DeAngelo, D. J., Stelljes, M., et al. (2019). Inotuzumab ozogamicin versus standard of care in relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Final report and long-term survival follow-up from the randomized, phase 3 INO-VATE study. Cancer,125(14), 2474–2487. 10.1002/cncr.32116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caimi, P. F., Ai, W., Alderuccio, J. P., et al. (2021). Loncastuximab tesirine in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (LOTIS-2): A multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. The Lancet Oncology,22(6), 790–800. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00139-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kreitman, R. J., Dearden, C., Zinzani, P. L., et al. (2021). Moxetumomab pasudotox in heavily pre-treated patients with relapsed/refractory hairy cell leukemia (HCL): Long-term follow-up from the pivotal trial. Journal of Hematology & Oncology,14(1), 35. 10.1186/s13045-020-01004-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bardia, A., Mayer, I. A., Vahdat, L. T., et al. (2019). Sacituzumab Govitecan-hziy in Refractory Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine,380(8), 741–751. 10.1056/NEJMoa1814213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bardia, A., Hurvitz, S. A., Tolaney, S. M., et al. (2021). Sacituzumab Govitecan in Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine,384(16), 1529–1541. 10.1056/NEJMoa2028485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tagawa, S. T., Balar, A. V., Petrylak, D. P., et al. (2021). TROPHY-U-01: A Phase II Open-Label Study of Sacituzumab Govitecan in Patients With Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma Progressing After Platinum-Based Chemotherapy and Checkpoint Inhibitors. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology,39(22), 2474–2485. 10.1200/JCO.20.03489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hong, D. S., Concin, N., Vergote, I., et al. (2020). Tisotumab Vedotin in Previously Treated Recurrent or Metastatic Cervical Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research,26(6), 1220–1228. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-2962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coleman, R. L., Lorusso, D., Gennigens, C., et al. (2021). Efficacy and safety of tisotumab vedotin in previously treated recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer (innovaTV 204/GOG-3023/ENGOT-cx6): A multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. The lancet Oncology,22(5), 609–619. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00056-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Modi, S., Saura, C., Yamashita, T., et al. (2020). Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Previously Treated HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine,382(7), 610–621. 10.1056/NEJMoa1914510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shitara, K., Bang, Y. J., Iwasa, S., et al. (2020). Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Previously Treated HER2-Positive Gastric Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine,382(25), 2419–2430. 10.1056/NEJMoa2004413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cortés, J., Kim, S. B., Chung, W. P., et al. (2022). Trastuzumab Deruxtecan versus Trastuzumab Emtansine for Breast Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine,386(12), 1143–1154. 10.1056/NEJMoa2115022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burris, H. A., Rugo, H. S., Vukelja, S. J., et al. (2011). Phase II Study of the Antibody Drug Conjugate Trastuzumab-DM1 for the Treatment of Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2) –Positive Breast Cancer After Prior HER2-Directed Therapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology,29(4), 398–405. 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.5865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krop, I. E., LoRusso, P., Miller, K. D., et al. (2012). A phase II study of trastuzumab emtansine in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer who were previously treated with trastuzumab, lapatinib, an anthracycline, a taxane, and capecitabine. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology,30(26), 3234–3241. 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.5902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verma, S., Miles, D., Gianni, L., et al. (2012). Trastuzumab emtansine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine,367(19), 1783–1791. 10.1056/NEJMoa1209124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yardley, D. A., Krop, I. E., LoRusso, P. M., et al. (2015). Trastuzumab Emtansine (T-DM1) in Patients With HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer Previously Treated With Chemotherapy and 2 or More HER2-Targeted Agents: Results From the T-PAS Expanded Access Study. Cancer J Sudbury Mass.,21(5), 357–364. 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kashiwaba, M., Ito, Y., Takao, S., et al. (2016). A multicenter Phase II study evaluating the efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetics of trastuzumab emtansine in Japanese patients with heavily pretreated HER2-positive locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology,46(5), 407–414. 10.1093/jjco/hyw013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krop, I. E., Kim, S. B., Martin, A. G., et al. (2017). Trastuzumab emtansine versus treatment of physician’s choice in patients with previously treated HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (TH3RESA): Final overall survival results from a randomised open-label phase 3 trial. The lancet Oncology,18(6), 743–754. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30313-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watanabe, J., Ito, Y., Saeki, T., et al. (2017). Safety Evaluation of Trastuzumab Emtansine in Japanese Patients with HER2-Positive Advanced Breast Cancer. Vivo Athens Greece,31(3), 493–500. 10.21873/invivo.11088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Montemurro, F., Ellis, P., Anton, A., et al. (2019). Safety of trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) in patients with HER2-positive advanced breast cancer: Primary results from the KAMILLA study cohort 1. European Journal of Cancer,109, 92–102. 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von Minckwitz, G., Huang, C. S., Mano, M. S., et al. (2019). Trastuzumab Emtansine for Residual Invasive HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine,380(7), 617–628. 10.1056/NEJMoa1814017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cortés, J., Diéras, V., Lorenzen, S., et al. (2020). Efficacy and Safety of Trastuzumab Emtansine Plus Capecitabine vs Trastuzumab Emtansine Alone in Patients With Previously Treated ERBB2 (HER2)-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer: A Phase 1 and Randomized Phase 2 Trial. JAMA Oncology,6(8), 1203–1209. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.1796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Emens, L. A., Esteva, F. J., Beresford, M., et al. (2020). Trastuzumab emtansine plus atezolizumab versus trastuzumab emtansine plus placebo in previously treated, HER2-positive advanced breast cancer (KATE2): A phase 2, multicentre, randomised, double-blind trial. The Lancet Oncology,21(10), 1283–1295. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30465-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsurutani, J., Iwata, H., Krop, I., et al. (2020). Targeting HER2 with Trastuzumab Deruxtecan: A Dose-Expansion, Phase I Study in Multiple Advanced Solid Tumors. Cancer Discovery,10(5), 688–701. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diéras V, Deluche E, Lusque A, et al. Abstract PD8–02: Trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) for advanced breast cancer patients (ABC), regardless HER2 status: A phase II study with biomarkers analysis (DAISY). Cancer Res. 2022;82(4_Supplement):PD8–02. 10.1158/1538-7445.SABCS21-PD8-02

- 49.Sheyi, R., de la Torre, B. G., & Albericio, F. (2022). Linkers: An Assurance for Controlled Delivery of Antibody-Drug Conjugate. Pharmaceutics.,14(2), 396. 10.3390/pharmaceutics14020396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singh, A. P., & Shah, D. K. (2019). A “Dual” Cell-Level Systems PK-PD Model to Characterize the Bystander Effect of ADC. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences,108(7), 2465–2475. 10.1016/j.xphs.2019.01.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]